ABSTRACT

In this article, we explore how the recently revived approach of social science fiction can be used as a creative and critical method to imagine and discuss the future of artificial intelligence in education (AIED). We review one hundred social science fiction stories written by researchers and analyse how they depict the potential role of AI in teaching and learning. Through a thematic analysis, we identify four main themes and several sub-themes that highlight the hopes and concerns that the researchers express for the future of AIED. Although the fictions present imaginative scenarios of anticipated AIED futures already present in the literature, they also feature creative illustrations of how such futures may materialise. We observe that social science fiction can be valuable in approaching the complex and uncertain landscape of AIED while stimulating reflection and dialogue. We conclude by suggesting some directions for further research and practice using this emerging approach of storytelling.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is quickly transforming into a force that has the potential to reshape our world, including the landscape of education. While the discussion around AI and education is increasingly becoming vigorous, predicting the actual impact of AI in teaching and learning is not possible, since the technology is growing exponentially. However, we can imagine and discuss different possible futures of AI in education (AIED). While some educators see the potential of AI in supporting the learning process (Lampou Citation2023), others have expressed the need to learn more about the technology (Hrastinski et al. Citation2019). The question needs to be posed: what might education look like once AI has become fully integrated? The current adaptivity and personalisation rhetoric tends to focus on individualised learning and cognitive aspects of learning (Escotet Citation2023). The focus is often on correct answers rather than supporting the process of learning, on fixed tasks rather than open and creative tasks (U.S. Department of Education Citation2023). It is essential to move beyond idealising the allure of AI and to critically discuss how it can operate within educational settings.

To respond to questions regarding the particularities of AI’s invasion in education, the medium of speculative storytelling has been adopted by various researchers to help shed light on some of the issues currently at play. More specifically, the need to turn within and wonder about the future that we should work for (or against) has recently given rise to fictional stories written by researchers (Hrastinski and Jandrić Citation2023; Suoranta et al. Citation2022; Teräs, Teräs, and Suoranta Citation2023). Such stories featuring educational institutions where AI has been integrated may help us acknowledge real issues that need to be dealt with to contribute towards better education futures.

Speculative storytelling branded as social science fiction, speculative fiction, or design fiction has recently dealt with fictional education spaces that featured AI in positive or negative light. It is worth first looking into how these fiction terms can differ. Social science fiction can refer to imaginary texts that spark sociological imagination or texts that rely on science fiction to explore social and technological issues (Gerlach and Hamilton Citation2003; Penfold-Mounce, Beer, and Burrows Citation2011). Speculative fiction as a genre breaks away from the narrow scope of science fiction and traditional research and ‘challenges assumptions of empirical existence of reality’ (Lucas Citation2010, 1). Design fictions exist on a ‘spectrum between speculative and critical’ (Cox Citation2021, 3) and have been characterised as ‘a conflation of design, science fact, and science fiction’ (Bleecker Citation2022, 6). It can be noticed that all these terms encompass an exploratory, sometimes critical, use of fiction in their dealings with the construction of the future. In the present article, we follow the use of the term social science fiction, as described above, recognising at the same time that all three terms can be used in critical explorations of the future.

The aim of this article is to explore how researchers imagine the potential role of AI in education futures. This is done by reviewing how scholars describe the future intersection of AI and education through the medium of social science fiction. While empirical research can focus on the effects of AI so far, fiction provides us with tools to look towards the future and approach the topic of AIED more creatively and critically than what the limits of current knowledge allow us to. By thematically analysing such fictions, the article highlights connected ideas and outlooks imagined by the fiction authors in various aspects concerning teachers and students of an AI future. The questions guiding the present research are the following:

How is the role of AI in the future of learning and teaching depicted in social science fiction written by researchers?

To what extent does social science fiction contribute original ideas to the AIED discourse?

Background

AI, education, and society

The revolutionary possibilities of the introduction of AI in education settings have been recently accentuated, but AI has affected teaching and learning for a long time. A rich past for AIED can be traced back to the mid-twentieth century, when research projects started connecting AI with learning sciences (Doroudi Citation2023). At the end of the same century, computers started being recognised as detrimental for the learning process, with Papert’s Mindstorms being one of the works supporting the need for students’ computer literacy (Papert Citation1993), paving the way for digitalising teaching and learning. From intelligent tutoring systems and adaptive learning environments (Desmarais and Baker Citation2012) to chatbots that promote learner-centred instruction and learning (Chen, Chen, and Lin Citation2020), the field has both undergone advancements and gained popularity. This was heightened with the mass introduction of generative AI (GAI) chatbots that can be of use to the general public, sparking discussions around technological change in relation to societal change (Sætra and Skaug Citation2023). Nevertheless, there have been several cautionary notes when it comes to the widespread impact of AI, both in education and society.

The range of challenges that AI presents is wide. Ethical issues of surveillance and bias lead the discussion, while human-AI interactions are foreseen as at least problematic. More specifically, risks for students’ privacy and autonomy (Akgun and Greenhow Citation2022; du Boulay Citation2022; Swartz and McElroy Citation2023) as well as biases that can occur within large language models (LLMs) have been emphasised in the literature (Ferrara Citation2023; Arora et al. Citation2023). Additionally, the creation of machines that feature social skills and awareness is presented as a ‘myth’ (Larson Citation2022), with the act of attributing human features to computers, known as anthropomorphism, alarmingly surging (Bewersdorff et al. Citation2023; Alabed, Javornik, and Gregory-Smith Citation2022; Zimmerman, Janhonen, and Beer Citation2023). This is partly attributed to the conversational form of GAI tools, and it could bring about a disruption in the relationships between humans as well as humans and computers, due to the illusion of a reality that it constructs.

Social science fiction

This paper uses fictional texts that have recently been written and published by scholars and that relate to the future of AIED. These texts are analysed to form an understanding of how these scholars imagine education futures shaped by AI. The future fictional realities have the ability to ‘bring new practices and ideas into being while maintaining space for curiosity, critique, doubt, unintended consequences and emergent properties of technologies in use,’ responding to the ‘narrowness of research horizons in digital education’ (Ross Citation2017, 215). It is this space in the AIED field that this paper attempts to address by implicitly showcasing that social science fiction can allow both its writers and readers to think about the future, all while keeping an eye on the present. In other words, the representational power of fiction may sometimes not be grounded in our empirical reality, but it can create a reality of its own, which is still valuable for its insights (Iser Citation1975). The genre analysed here is one whose ‘necessary and sufficient conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment’ (Suvin Citation1988, 37). It is exactly this imaginative power that has prompted social scientists to use science fiction to talk about and explore social issues (Gerlach and Hamilton Citation2003).

Recent articles have stressed the need to recalibrate our efforts to imagine the future of AIED (Bond et al. Citation2024; Chaudhry and Kazim Citation2022), and speculative storytelling opens up possibilities for ‘reorienting us to ever more complex understandings of our interrelatedness in the present’ (Tomin and Collis Citation2024, 248). Fiction writing as analysis and as research has also been said to be an effective analytical lens, with the right combination of challenging and creative efforts (McCarthy and Stice Citation2023). Discussions around social science fiction, as defined earlier in this article, will inevitably involve the notions of utopias, dystopias, and science fiction (Moylan Citation2000). While utopian and dystopian spaces used to be placed elsewhere, this changed in the late eighteenth century, when ‘[a]lternative societies could now be set in the future rather than simply depicted as already existing somewhere else; by extension an alternative society could be designed and planned and not just dreamed about: the present could be changed’ (Fitting Citation2010, 138). When reviewing AIED, there are many opportunities but also critical concerns. Thus, it does not come as unexpected when researchers call for more utopian imaginations as a way to co-design the future today (Bayne Citation2023; Houlden and Veletsianos Citation2023; Selwyn et al. Citation2020). The fictions analysed here can help make such concerns concrete as well as contribute to the discussion of potential futures for AIED, including futures that we want to strive for and ones we may want to steer away from.

Methodology

There has been a gradually increasing interest in social science fiction among researchers in the field of technology and education during the past couple of years, and in particular on the role of AI in the future of education. For this article, we attempted to include all fiction that has been published in scientific journals and edited books recently (see Supplemental online material). We have followed what has been published in journals such as Learning, Media and Technology, and Postdigital Science and Education, which have been leading this development since 2020. We have also performed searches on academic databases with keywords such as speculative, fiction, narrative, and education. A total of 100 single fiction texts were found as part of journal articles and edited book collections. Their sources appear in .

Table 1. Sources of fiction texts.

Thematic analysis of the fictions

Thematic analysis was chosen for this study based on its flexibility as a research method. Using thematic analysis as a qualitative data analysis method ‘is about telling ‘stories’, about interpreting, and creating, not discovering and finding the ‘truth’ that is either ‘out there’ […] or buried deep within the data,’ according to Braun and Clarke (Citation2019, 591). This approach fits our aim to explore the future of AIED through interpreting social science fictions. Our approach also crosses over to post-structuralist ideas, since we discuss the matter without assuming that there is always a stable definition of what education, AI, or their connection, is. In other words, the critical and creative process of analysing the fictions here is grounded on our openness to the new, different, and radical reality (or realities) that can unfold (Williams Citation2005).

The six basic steps to a thematic analysis, which were applied here as well, include: (i) familiarisation with the data, (ii) generating initial codes, (iii) looking for themes, (iv) reviewing themes, and (v) naming and defining themes, before (vi) writing up the report (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). An initial familiarisation with the fictions collected allowed for a preliminary understanding of the topics touched upon, while providing an overview of how social science fiction was employed by each writer or set of writers. The themes, or ‘stories about particular patterns of shared meaning across the dataset’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2019, 592), were created as a result of an iterative process of comparing codes that presented similarities across the dataset.

In the process of working with the codes and the themes that were created, the first author of this article generated the initial codes and themes, and the second author reviewed them in an iterative manner. More specifically, the first author coded the fictions of the dataset with a view to organise the data in a meaningful way. This author attempted latent coding in an effort to interpret what has been written in the fictions and better inform the codes that would be organised into themes, having in mind the questions set for this research. Then, the second author reviewed and gave feedback on the proposed themes, helping in their review and final categorisation. Some examples of the codes and their categorisation are included in .

Table 2. Samples from the coding process.

Employing thematic analysis at the latent level allowed for an analysis that ‘goes beyond the semantic content of the data, and starts to identify or examine the underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualizations – and ideologies’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 84). Following this paradigm, the coding and thematising of the fictions revealed certain assumptions embedded in the narratives. The results presented below provide an overview of the identified themes that were collated after connecting the ideas found across the dataset. Relevant quotes supporting each theme are also used throughout the results section.

Results

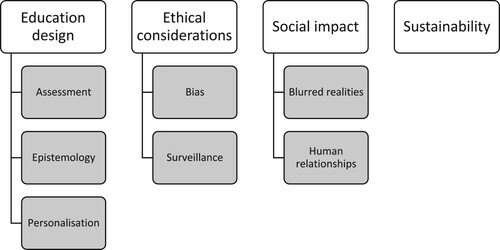

A total of 100 fictions were thematically analysed. This analysis revealed a set of sub-themes that were organised into four overarching themes. presents the themes and sub-themes and how they are related.

This section is structured with a focus on the four main themes that were collated after analysing the dataset. Each subtheme is introduced through a relevant quote from the fictions, which is then followed by a summary of how the subtheme was approached by the fiction authors in general.

Theme 1: education design (assessment, epistemology, personalisation)

The first theme relates to AI in education design. The fictions revolve around the changes that AI can bring in assessment practices and epistemological assumptions, as well as personalised teaching and learning.

[The teacher] looked across to the folder containing the student work, then double blinked to upload this to his own personal GPT-15 rig. And there it was: all the grades, all the personalized feedback, and comments on the work. (Curcher Citation2023, 2)

For the sub-theme of assessment, fiction authors were mostly focused on the viewpoints of both teachers and students, describing how future assessments could be negatively affected by AI. Such technologies are mostly seen as either a way to ensure fairness and originality, by using AI-proctored examinations for example, or as a time-saving outlet for overworked staff members, as is made evident in the quote above. More specifically, students are imagined to heavily rely on generative AI to complete their assignments, from ideation to writing and submission. As a result, their motivation and creativity are severely affected, as is their commitment to honesty and fairness, otherwise known as academic integrity in higher education settings. In this context, AI is speculated in some fictions to work in a panopticon-like manner by monitoring and analysing students’ body language and even eye movements to prevent cheating, contributing to surveillance concerns, which are further discussed in the sub theme surveillance below. In such a high-tech education system, teachers become responsible for automating feedback and evaluating students’ performance in a streamlined way.

Are you saying that the old books, scientific articles, research projects, press and specialized databases used as reliable sources by the first generation of AI were replaced by imaginary and not real narratives? I mean, the science fiction consumed on Netflix, Apple TV and other platforms? (Santos-Hermosa in Bozkurt et al. Citation2023, 115)

Epistemology as a sub-theme here refers to the forms of knowledge in the future, as well as how it is treated by machines and humans. A common thread throughout the relevant codes is a questioning and blurred distinction between human and machine forms of knowledge and learning. Some quotes depict a utopian vision where technology liberates time for higher order thinking and pursuits. In contrast, others foresee outsourcing of reasoning and synthesis to machines, with humans potentially just consuming conclusions. Several passages also portray AI technologies as replacing traditional modes of education by directly teaching students or completing assignments. This is described as having both positive potential but also risks undermining human thinking and understanding. Furthermore, some fictions, including the passage cited in the quote above, suggest that AI will control the type of knowledge that is available to humans; universal truths, or even subjective opinions, have been transformed or altered by AI.

Sarah logs onto talk to her TeacherChat, and selects the teacher personality she needs to speak to today. She chooses ‘female’ and ‘supportive’ and ‘challenging’ and someone who is an expert in ‘mathematics’ and tends to use ‘visuals’. TeacherChat shows her a picture of Salma, her teacher for now. (Bali in Bozkurt et al. Citation2023, 68)

Personalisation, as the final sub-theme here, refers to the utilisation of AI technologies to provide highly customised learning resources and journeys for the learners. On the one hand, personalisation is portrayed positively through individualised learning pathways tailored to students’ needs, skills, and interests. AI tutoring bots that adapt instruction specifically for each learner are also presented as helpful supports, like in the quote describing an AI chatbot above. However, some fictions hint at potential downsides if personalisation is taken to an extreme. Precisely targeted feedback and adaptive exercises based on profiling could undermine autonomy and uniformity of competencies if relied on heavily. A recurring argument is the role of data collection and surveillance in driving personalised education. While aiming to improve outcomes, the degree and consent aspects of monitoring behaviours and emotions are questioned.

Theme 2: ethical considerations (bias, surveillance)

The second theme refers to issues of privacy and legal considerations, approached through references to bias in relations to AI algorithms as well as the surveillance that users might be subjected to.

We got a bunch of robots that replicated existing patterns and reinforced prejudices. How do you train AIs to recognize their own bias? (Fuentes-Martinez Citation2023, 1)

Biased representation or treatment of certain groups and knowledge was a central concern for some authors. The dataset presents issues of bias in a negative light, affecting various aspects of humanity. Ranging from issues of fairness and representation to the content of teaching and learning, fiction authors paint a bleak picture of how AI can contribute to a reinforcement of already existing prejudices. By asking whether it is the algorithm that initiates the bias or the user that is affecting it, some authors even question the future state of LLMs that humans train with their own data. Additionally, AI seems to gain the power to shape perceptions and expectations in the fictions, since users trust the information that is generated through AI chatbots as being true. This has the potential to perpetuate biases existent in human text or that is innocently put together by AI itself, as the above quote mentions. As such, AI technologies are imagined to be able to shape their users’ beliefs about the world.

While we are chatting, the app beeps again about something. For once I ignore it: Sometimes the tracking feels a bit intrusive. It bugs me a bit that it is monitoring everything I do, but it’s helpful and makes me feel safe. (Cox Citation2020, 4)

AI integration in education can severely affect surveillance concerns, according to the analysed fictions. On one hand, the constant monitoring of students is portrayed as supporting personalised learning. However, some fictions question if this compromises privacy and ethical data handling. Precise tracking of biological data, behaviours, locations, and digital interactions is a recurring practice in imagined scenarios, with implications for consent and well-being considered. The above quote illustrates the ambivalence that some students may feel about being constantly monitored and tracked by AI technologies. The app that notifies the students might be useful, but it may also be a sign of an all-pervasive system that watches over every move and action of the students. Several fictions imagine surveillance escalating to dystopian extremes through tactics like mandatory microchipping or all-encompassing behavioural monitoring systems.

Theme 3: social impact (blurred realities, human relationships)

The third theme touches upon the extrapersonal impact of AI technologies, with specific mentions on how the individual gets to relate to the outside world when using AI, as well as the impact it can have on the relationships between people or between people and machines.

[I] got absorbed by my computer to a virtual space different from our real-world, where I met Adam, or like people call him ChatGPT. I was very surprised when he spoke to me in Arabic. […] The communication between us was so easy and fluent like we knew each other for years. Adam was very caring and he was there for me whenever I needed him. (Tlili in Bozkurt et al. Citation2023, 75)

AI: ‘Thanks, James. Feeling is not important here. Remember, study level is assessed for proper placement, course-and program-planning. Age is only of interest in curricular activities. You meet students of the same age every week in Physical Education Advanced 951 and Art and Design 253.’

James: ‘I know … ’ (Lindqvist Citation2023, 2)

The second sub-theme here touches upon the impact of AI on human relationships. Firstly, these relationships can be assisted by or mediated through AI technologies. Community-focused networks and feelings of collective achievement are portrayed as a result of AI integration in schools. In particular, AI tools bring students together and help them with group assignments or presentations, acting as knowledgeable mediators. Secondly, AI technologies have developed their emotional intelligence in the fictional futures, being able to better sympathize with students and teachers when they sense some discouragement or discomfort in study-related matters. Of course, the opposite can happen, as AI might be blind to the user’s emotions and needs, as seen in the quote above. Close bonds can be formed with AI assistants in the form of both collaborative and emotional connections, although there can be psychological dangers when getting too attached to them.

Theme 4: sustainability

The unprecedented scale of server usage has a staggering environmental impact. (Stewart & Bonnie in Bozkurt et al. Citation2023, 116)

Discussion

Our thematic analysis has revealed several issues that can be used to closely discuss AIED. In this section, we critically approach the points raised in the analysed fictions, addressing the role of AI in the future of education, while highlighting the contributions that social science fiction can offer through the identified themes from the analysis.

In an attempt to contextualise the findings from the analysed fictions with previous research, it becomes apparent that the fictions contribute with an illustrative picture of the potential impact of AIED throughout the four themes, without deviating from currently established ideas. More specifically, grim speculations of AI replacing teachers or infiltrating the ground-truth texts of humanity can help concretise general fears of an all-powerful AI (Sætra and Skaug Citation2023). Concerns around the (un)ethical use of surveillance in education (Akgun and Greenhow Citation2022) are taken to an extreme when fictions imagine classrooms where AI is invading students’ thoughts and using their bodily reactions to force them to concentrate in class, for example. The power to create and disseminate manipulative or deceptive content (Gehl and Lawson Citation2023) is among the fears around the general social impact of AI with extensions to the education world (Ienca Citation2023), as showcased in the fictions through the potential of AI-generated information to misguide and confuse humans. Finally, the devastating environmental impact due to the extensive use of computing power has been discussed before, in what has also been termed AI capitalism (Schütze Citation2024) in the literature and portrayed through increased elements of natural decay and a collapse of human civilisation.

In the analysed fictions, metaphors and imagined realities are used to illustrate how AI can benefit or hinder teaching and learning. More specifically, AI is imagined acting as an assistant, providing automated feedback and helping in the curriculum planning and delivery processes. At the same time, however, overusing or abusing AI assistance is seen in a negative way, since students could merely outsource their tasks to an external assistant, missing an opportunity to develop their skills. Moreover, AI takes on the role of an intermediary in accessing, generating, and disseminating information, surfacing at the same time a challenge for which facts are worth preserving and what is deemed useless (and by whom). Critical thinking skills and human literacy thus emerge as important skills for humans who are allured by speedy and real-sounding information that might be false or biased. Finally, AI assumes the role of a tutor by offering individualised learning paths and always-available assistance, which some users might find overwhelming or not as helpful at times, as depicted in the fictions.

AI technologies are also imagined serving as close friends to students, much like their role as assistants or tutors above. In this case, they can be helpful in creating or maintaining networks and relationships between humans (Christakis Citation2019) through AI posing as a facilitator and mentor in groupwork, for example. They can also be deceiving, as they might emotionally capture humans (Zimmerman, Janhonen, and Beer Citation2023) through posing as companions that can empathise with human emotions, which they cannot do in reality. Additionally, AI appears as an environment destroyer in the fictions, mostly due to its unsustainable consumption and draining of the planet's natural resources, producing scenarios where the ecological balance is significantly threatened.

Through identifying the potential roles of AI in the future of education, as summarised above, and connecting those with the themes from our analysis, it can be seen that the medium of speculation has yielded fairly conservative results so far, adding a creative and critical twist. More specifically, it is by no means innovative to consider the capabilities of AI in assisting learning, through its ability to provide intelligent tutoring systems and deliver assistance that can be used in teaching (Chen, Chen, and Lin Citation2020). Additionally, the potentially devastating effects for ethics and the environment have been highlighted in the past as well (du Boulay Citation2022; Dhar Citation2020). However, it can be argued that speculative storytelling can open up one’s imagination and issues like these can be developed even further. This is what the analysed fictions showed through the creative and (at times) far-reaching examples of how such issues can materialise. For instance, the fictional teachers or students were at times confronted with the harsh reality of having to abide to the rules set by AI while feeling helpless due to the invasion of their privacy by a supposedly helpful technology. Overall, the fictions make the future more concrete and help the reader imagine, feel, and experience potential future education worlds, in which possibilities, uncertainties, and risks have materialised. Beyond abstract statements, such as individualising learning or invading privacy, the fictions illustrate what it could be like to be a teacher or student in such AI-infused education futures.

It can be useful for our analysis here to note that the fictions have mostly dealt with short-term futures without approaching far-away times. This could be attributed to their writers’ interest in futures more adjacent to their present or perhaps an acknowledgement that speculating about the future of AI seems impossible due to the technology’s rapid development and progress. Furthermore, the prevalence of cautionary and dystopian narratives within the analysed dataset likely stems from an underlying belief that digital teaching and learning have undergone a fundamental transformation in recent years, and that AI can only add to a set of existing challenges.

It is evident that the analysed fictions provided a picture that is comparable with the insights that current research is offering with regards to the future directions of AIED. The dominant dystopian ideology in these fictions or the negative sentiments they feature can be said to reflect the current wave of reserved enthusiasm when it comes to AI and AIED; although there are many possibilities, the uncertainty and potential risks associated with such rapidly advancing technologies cannot be overlooked. On a more subtle note, the fictions have shown that a creative dealing with the future can help reveal more nuanced thoughts that might not have surfaced otherwise. In this case, the interplay between positive and negative speculations was found to be fruitful, especially because of the colourful illustrations of hopeful and pessimistic scenarios that can serve as inspiration for the future. Most of the researchers writing fiction were seemingly confined by current arguments about AIED rather than being fully speculative. Instead, they contributed by writing fiction that illustrates what futures of AI in education could look like based on current discussions. While it is certainly a worthwhile exercise to illustrate potential education futures, researchers are also encouraged to write fictions that challenge current assumptions. By default, the very nature of the future includes an uncertainty which can only be speculated about. Social science fiction provides a platform on which uncertainties can be explored, discussed, and reflected upon.

The speculative storytelling approach opens up valuable perspectives that could inform advancing thought in the field by solidifying abstract concerns through more concrete examples. More specifically, several questions can arise based on the themes identified in the texts, as well as on how they connect to our current education reality. These include but are not limited to questions of inequalities in the use of AI in education settings, new forms of dependencies on technology, the need for ethical frameworks that can protect AI users and their privacy, as well as the impact of a wide-scale implementation of AI on teachers or other professionals’ roles. Additionally, the psychological aspects of reduced human interaction in favour of human-AI collaboration in learning situations can trigger challenges comparable to those that COVID-19 accentuated. Overall, a human-centric approach in education while integrating increasingly capable AI technologies emerges as an aim for the coming years; policy measures and (inter)national efforts are beginning to emerge and can take the above into consideration. Issues such as these can be explored through speculative stories which can help reflect critically on the future we are creating, prompting discussions around not only the technological capabilities but also the values we want to prioritise in education.

Further research and limitations

In this paper, the analysis of social science fiction has been employed as a way to understand how researchers imagine AI-infused education futures. This research design presents certain limitations. Firstly, the scope of our study is limited by the types of social science fiction stories that have been written so far. These stories have mainly been written by critical education researchers with many of them featuring dystopian elements and being set in near futures. Secondly, the thematic analysis of the stories is based on our own interpretation and coding of the data; thematic analysis is necessarily dependent on the background and assumptions of the researcher (Braun and Clarke Citation2019). Thus, different researchers may identify different themes from the same stories. Additionally, the findings of our study are based on imaginations and assumptions located in the fictions. Their writers have likely focused on issues of greater interest to themselves but may not have considered all the possible ethical, social, or other challenges and opportunities that could arise from the implementation of AI in education settings. Finally, it is worth mentioning that the speculative storytelling analysed here could be further examined for its literary characteristics and other (perhaps extralinguistic or cultural) elements, which might help reveal more nuanced contributions and insights.

Through the analysis of the texts, the subset of generative AI emerged with a striking prominence as the main focal point of many fictions. As a result, this article at times implicitly shifted its focus to generative AI, not in terms of a narrower scope, but as a reflection of its significant presence and potential impact in the evolving narrative of AI in education. Broader explorations of how other forms of AI can affect AIED can therefore open up. Certainly, there are avenues of research that could complement the findings of this paper and expand the scope of such a study in the future. For example, conducting empirical research with students, teachers, and policymakers could build on the themes identified in this article.

Conclusion

It is important to understand key opportunities but also to prevent risks and unintended consequences when integrating AI in education. In an ever-changing landscape of technology advancements, it can be useful to speculate and discuss as to what the future holds for AIED. Social science fiction offers an opportunity to investigate such speculations about the future. The fictions reveal a spectrum of possibilities, ranging from enhanced education communities that have benefited from the transformation brought on by AI to frustrated teachers and students who regret believing in the promises made by the EdTech industry. Understanding such narratives can shed light on the complex interplay between technological innovation, educational aspirations, and the challenges faced by educators. At the same time, speculative narratives for AIED futures need to break away from the boundaries of present-day truths and convictions and become more creative with their dealings with the unknown, reimagining the fundamental nature of learning, teaching, and educational systems.

The social science fictions that were analysed revealed both positive and negative feelings for the future of AI in education. On one hand, fiction authors hope that AI can enhance the learning experience, personalise the curriculum, provide feedback and guidance, and foster collaboration and creativity among students and teachers. On the other hand, they are concerned about the ethical, social, and practical implications of AI, such as the extent of implementation, the loss of human agency, the invasion of privacy, and concerns for bias and discrimination. These hopes and concerns are not mutually exclusive, but rather reflect the complexity and uncertainty of the future.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our colleagues in the Digital learning research group at KTH, as well as the anonymous peer reviewers, for their valuable comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akgun, Selin, and Christine Greenhow. 2022. “Artificial Intelligence in Education: Addressing Ethical Challenges in K-12 Settings.” AI and Ethics 2 (3): 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00096-7.

- Alabed, Amani, Ana Javornik, and Diana Gregory-Smith. 2022. “AI Anthropomorphism and Its Effect on Users’ Self-Congruence and Self–AI Integration: A Theoretical Framework and Research Agenda.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 182: 121786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121786.

- Arora, A., M. Barrett, E. Lee, E. Oborn, and K. Prince. 2023. “Risk and the Future of AI: Algorithmic Bias, Data Colonialism, and Marginalization.” Information and Organization 33 (3): 100478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2023.100478.

- Bayne, Sian. 2023. “Digital Education Utopia.” Learning, Media and Technology 0 (0): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2262382.

- Bewersdorff, Arne, Xiaoming Zhai, Jessica Roberts, and Claudia Nerdel. 2023. “Myths, Mis- and Preconceptions of Artificial Intelligence: A Review of the Literature.” Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 4: 100143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100143.

- Bleecker, Julian. 2022. “Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact, and Fiction.” In Machine Learning and the City, edited by Silvio Carta, 561–578. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Bond, Melissa, Hassan Khosravi, Maarten De Laat, Nina Bergdahl, Violeta Negrea, Emily Oxley, Phuong Pham, Sin Wang Chong, and George Siemens. 2024. “A Meta Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A Call for Increased Ethics, Collaboration, and Rigour.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 21 (1): 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00436-z.

- Boulay, Benedict du. 2022. “Artificial Intelligence in Education and Ethics.” In Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Education, edited by Olaf Zawacki-Richter and Insung Jung, 1–16. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0351-9_6-1.

- Bozkurt, Aras, Junhong Xiao, Sarah Lambert, Angelica Pazurek, Helen Crompton, Suzan Koseoglu, Robert Farrow, et al. 2023. “Speculative Futures on ChatGPT and Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): A Collective Reflection from the Educational Landscape.” Asian Journal of Distance Education 18 (1): 53–130. http://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/709.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.10802159676X.2019.1628806.

- Chaudhry, Muhammad Ali, and Emre Kazim. 2022. “Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIEd): A High-Level Academic and Industry Note 2021.” AI and Ethics 2 (1): 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00074-z.

- Chen, Lijia, Pingping Chen, and Zhijian Lin. 2020. “Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review.” IEEE Access 8: 75264–75278. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2988510.

- Christakis, Nicholas A. 2019. “How AI Will Rewire Us.” The Atlantic, March 4, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/04/robots-human-relationships/583204/.

- Conrad, Diane, and Sean Wiebe. 2022. Educational Fabulations: Teaching and Learning for a World Yet to Come. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93827-7.

- Costello, Eamon, Mark Brown, Enda Donlon, and Prajakta Girme. 2020. “‘The Pandemic Will Not Be on Zoom’: A Retrospective from the Year 2050.” Postdigital Science and Education 2 (3): 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00150-3.

- Cox, Andrew. 2020. AI and Robots in Higher Education: Eight Design Fictions. Sheffield, England: The University of Sheffield.

- Cox, A. M. 2021. “Exploring the Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Robots on Higher Education Through Literature-Based Design Fictions.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 18 (1): 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00237-8.

- Curcher, Mark. 2023. “The Pseudo Uni.” Postdigital Science and Education 5: 558–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00384-3.

- Desmarais, Michel C., and Ryan S. J. d. Baker. 2012. “A Review of Recent Advances in Learner and Skill Modeling in Intelligent Learning Environments.” User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction 22 (1): 9–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11257-011-9106-8.

- Dhar, Payal. 2020. “The Carbon Impact of Artificial Intelligence.” Nature Machine Intelligence 2 (8): 423–425. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-020-0219-9.

- Doroudi, Shayan. 2023. “The Intertwined Histories of Artificial Intelligence and Education.” International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 33 (4): 885–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-022-00313-2.

- Escotet, Miguel Ángel. 2023. “The Optimistic Future of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education.” PROSPECTS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-023-09642-z.

- Ferrara, Emilio. 2023. “Fairness And Bias in Artificial Intelligence: A Brief Survey of Sources, Impacts, And Mitigation Strategies.” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.07683.

- Fitting, Peter. 2010. “Utopia, Dystopia and Science Fiction.” In The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature, edited by Gregory Claeys, 135–153. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press..https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL9780521886659.006.

- Fuentes-Martinez, Ana. 2023. “Memoirs of an Old Teacher.” Postdigital Science and Education 5: 556–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00382-5.

- Gehl, Robert W., and Sean Lawson. 2023. “Chatbots Can Be Used to Create Manipulative Content — Understanding How This Works Can Help Address It.” The Conversation, June 27, 2023. http://theconversation.com/chatbots-can-be-used-to-create-manipulative-content-understanding-how-this-works-can-help-address-it-207187.

- Gerlach, Neil, and Sheryl N. Hamilton. 2003. “Introduction: A History of Social Science Fiction.” Science Fiction Studies 30 (2): 161–173.

- Hillman, Thomas, Annika Bergviken Rensfeldt, and Jonas Ivarsson. 2020. “Brave New Platforms: A Possible Platform Future for Highly Decentralised Schooling.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (1): 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1683748.

- Houlden, Shandell, and George Veletsianos. 2023. “Impossible Dreaming: On Speculative Education Fiction and Hopeful Learning Futures.” Postdigital Science and Education 5: 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00348-7.

- Hrastinski, Stefan, and Petar Jandrić. 2023. “Imagining Education Futures: Researchers as Fiction Authors.” Postdigital Science and Education 5: 509–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-023-00403-x.

- Hrastinski, Stefan, Anders D. Olofsson, Charlotte Arkenback, Sara Ekström, Elin Ericsson, Göran Fransson, Jimmy Jaldemark, et al. 2019. “Critical Imaginaries and Reflections on Artificial Intelligence and Robots in Postdigital K-12 Education.” Postdigital Science and Education 1 (2): 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00046-x.

- Ienca, Marcello. 2023. “On Artificial Intelligence and Manipulation.” Topoi 42 (3): 833–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-023-09940-3.

- Iser, Wolfgang. 1975. “The Reality of Fiction: A Functionalist Approach to Literature.” New Literary History 7 (1): 7–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/468276.

- Lampou, Rania. 2023. “The Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Opportunities and Challenges.” Review of Artificial Intelligence in Education 4 (00): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.37497/rev.artif.intell.educ.v4i00.15.

- Larson, Erik J. 2022. The Myth of Artificial Intelligence: Why Computers Can’t Think the Way We Do. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Lindqvist, Marcia Håkansson. 2023. “AI Meets James.” Postdigital Science and Education 5: 547–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00371-8.

- Lucas, Gerald R. 2010. “Speculative Fiction.” In The Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Fiction, edited by Brian W. Shaffer, Patrick O’Donnell, David W. Madden, Justus Nieland, and John Clement Ball, 840–844. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444337822.wbetcfv2s013.

- Macgilchrist, Felicitas, Heidrun Allert, and Anne Bruch. 2020. “Students and Society in the 2020s. Three Future ‘Histories’ of Education and Technology.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (1): 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1656235.

- McCarthy, Mark D., and Sarah K. Stice. 2023. “Speculative Futures and “Found” Artifacts: Using Fiction for Defamiliarization and Analysis.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 23 (3): 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/15327086221139454.

- Miguel A., Cardona, Roberto J. Rodríguez, Kristina Ishmael, and U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology. 2023. Artificial Intelligence and Future of Teaching and Learning: Insights and Recommendations. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology. https://www2.ed.gov/documents/ai-report/ai-report.pdf.

- Moylan, Tom. 2000. Scraps of the Untainted Sky: Science Fiction, Utopia, Dystopia. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Papert, Seymour. 1993. Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. 2nd edition. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Penfold-Mounce, Ruth, David Beer, and Roger Burrows. 2011. “The Wire as Social Science-Fiction?” Sociology 45 (1): 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510387199.

- Ross, Jen. 2017. “Speculative Method in Digital Education Research.” Learning, Media and Technology 42 (2): 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1160927.

- Schütze, Paul. 2024. “The Impacts of AI Futurism: An Unfiltered Look at AI’s True Effects on the Climate Crisis.” Ethics and Information Technology 26 (2): 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-024-09758-6.

- Selwyn, Neil, Luci Pangrazio, Selena Nemorin, and Carlo Perrotta. 2020. “What Might the School of 2030 Be Like? An Exercise in Social Science Fiction.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (1): 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1694944.

- Sætra, Henrik Skaug. 2023. “Generative AI: Here to Stay, but for Good?” Technology in Society 75 (November): 102372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102372.

- Suoranta, Juha, Marko Teräs, Hanna Teräs, Petar Jandrić, Susan Ledger, Felicitas Macgilchrist, and Paul Prinsloo. 2022. “Speculative Social Science Fiction of Digitalization in Higher Education: From What Is to What Could Be.” Postdigital Science and Education 4 (2): 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00260-6.

- Suvin, Darko. 1988. “Science Fiction and Utopian Fiction: Degrees of Kinship.” In Positions and Presuppositions in Science Fiction, edited by Darko Suvin, 33–43. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-08179-0_3.

- Swartz, Mark, and Kelly McElroy. 2023. “The “Academicon”: Ai and Surveillance in Higher Education.” Surveillance & Society 21 (3): 276–281. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v21i3.16105.

- Teräs, Marko, Hanna Teräs, and Juha Suoranta. 2023. “From Official Document Utopias to a Collective Utopian Imagination.” In Postdigital Participation in Education: How Contemporary Media Constellations Shape Participation, edited by Andreas Weich, and Felicitas Macgilchrist, 177–198. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38052-5_9.

- Tomin, Brittany, and Ryan B. Collis. 2024. “Science Fiction, Speculative Pedagogy, and Critical Hope: Counternarratives for/of the Future.” In Reimagining Science Education in the Anthropocene, edited by Sara Tolbert, Maria F.G. Wallace, Marc Higgins, and Jesse Bazzul, 247–265. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35430-4_14.

- Williams, James. 2005. Understanding Poststructuralism. Understanding Movements in Modern Thought. Chesham: Acumen Pub.

- Zimmerman, Anne, Joel Janhonen, and Emily Beer. 2023. “Human/AI Relationships: Challenges, Downsides, and Impacts on Human/Human Relationships.” AI and Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00348-8.