ABSTRACT

We examine how community health workers (CHWs), while working as links between doctors, nurses and vulnerable groups, participate in the social construction of citizens in the implementation of Brazil’s primary healthcare policy. Drawing on interviews and a vignette experiment with CHWs in the city of São Paulo, we show that perceptions of CHWs about the vulnerability and agency of health system users impact upon their referrals to other levels of service. Judgments about the socioeconomic, cultural and moral conditions of families determine different referrals – on the one hand, to practices based on persuasion and respect for individual choices; on the other, to ‘top-down’ or forcible interventions. While implementing the same healthcare policy, CHWs construct users as (responsible) agents or (helpless) targets, thus determining different pathways in the health system and shaping the relationship between citizens and the state. Brazil’s primary health policy, while seeking to tackle vulnerability, is also a site where social representations are reproduced that contribute to the denial of the agency of citizens deemed more vulnerable and to the definition of their bodies as sites for state intervention.

Introduction

Community health workers (CHW) are close-to-community providers without medical training who act as links between doctors, nurses and health system users (Krieger et al., Citation2021; Olaniran et al., Citation2017). They are an important component of many health systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Often recruited from the communities they serve, CHWs can specialise or carry out many tasks: identifying health needs; collecting epidemiological information; scheduling consultations; accompanying patients in long-term medication; supporting vaccination and vector-control programmes; and promoting health education and disease prevention (Hartzler et al., Citation2018). In some countries, CHWs also have social and political roles through ‘action on social determinants on health for the transformation of living conditions’ (World Health Organization, Citation2018, p. 24).

Citizens evaluate positively the work of CHWs (Onwujekwe et al., Citation2006; Tine et al., Citation2013), and the latter are associated with an increase in satisfaction with the health system (Larson et al., Citation2019). The literature presents CHWs as important for addressing health disparities and the root causes of disease (Singh & Chokshi, Citation2013). They engage marginalised communities (Cook & Wills, Citation2011) and address gaps in information and resources necessary for people to access healthcare (Davlantes et al., Citation2019). CHWs also promote community advocacy activities (Ingram et al., Citation2014), raise awareness of rights and mobilise communities (Schneider & Nandi, Citation2014). They contribute to empowerment, at the community level through popular education initiatives that develop communities’ self-awareness and capacity to strategise (Wiggins et al., Citation2009), and individually by promoting self-determination, self-sufficiency and decision-making abilities (Becker et al., Citation2004). Overall, CHWs are identified as ‘social justice and policy advocates’ (Pérez & Martinez, Citation2008), ‘change agents’ (Ingram et al., Citation2016) and ‘social capital builders’ (Adams, Citation2020), fostering individual health and communal well-being.

The World Health Organization (Citation2018, p. 19) identified challenges of CHW programmes: poor planning; unclear roles, education and career pathways; lack of certification of CHWs; poor coordination; fragmented and disease-specific training; donor-driven management; tenuous linkage with health system; and lack of recognition. CHW action on community organisation also has pitfalls: communities risk being ‘captured by interest groups or individuals’, thereby ‘reinforcing inequitable power relations and alienating local communities’ (World Health Organization, Citation2018, pp. 58, 60). Similarly, academic works have highlighted problems with programme design and the socio-political context in which CHWs operate (Kok et al., Citation2015; Nunes, Citation2019; Schneider & Lehmann, Citation2016; Tulenko et al., Citation2013). Others argue that CHW programmes are traversed by power relations which can have unintended or counterproductive effects (Lehmann & Gilson, Citation2013; Lotta & Marques, Citation2020; Nunes & Lotta, Citation2019; Scott et al., Citation2017).

One avenue of enquiry in the analysis of challenges to CHW programmes considers the impact of CHW perceptions. Scholars have looked at how CHWs perceive health problems and interventions (Dembo, Citation2012; Kibe et al., Citation2019; Shet et al., Citation2017); how they see themselves, their motivations and their role (Oliver et al., Citation2015; Takasugi & Lee, Citation2012); and how they understand and navigate the difficulties they encounter (Mlotshwa et al., Citation2015). Underpinning these studies is the assumption that the opinions, judgments and reasonings of CHWs influence practice. This is because CHWs can have significant discretion and power, functioning as de facto gatekeepers to health systems (Lotta & Marques, Citation2020). Their work can lead to the (purposeful or inadvertent) reproduction of inequalities in access to health services (Lotta & Pires, Citation2020).

The present article explores how CHW perceptions influence the social construction of the ‘target populations’ of health policies, thus determining their degree of access to services. Academic works have explored how processes of social construction have a direct impact on policy implementation (Brady, Citation2018; Collins & Mead, Citation2021; Schneider & Ingram, Citation1993), namely by helping to define different levels of deservedness among citizens (Rowlingson & Connor, Citation2011; Teo, Citation2015). Our goal is to investigate the extent to which the implementation of Brazil’s primary health policy is shaped by the social construction of health system users by CHWs. We consider the extent to which this construction is underpinned by assumptions regarding the vulnerability of users, that is, their susceptibility to incur harm and ability to bounce back from harm; and their agency, that is, their ability to make decisions and act in a decisive way to shape the course of their own lives. In sum, in this paper, we ask: how do CHWs perceive and construct the health system users they interact with? Specifically, what assumptions do Brazilian CHWs make about the vulnerability and agency of users? How do these perceptions, and their associated social construction processes, shape CHW referrals to other levels of service in the health system?

Methodology

Brazilian CHWs (agentes comunitários de saúde) are part of the country’s public Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS), and specifically of its primary healthcare arm, the Family Health Strategy (Estratégia Saúde da Família, ESF). The ESF was implemented nationwide from 1994 onwards with the goals of humanising service delivery; reducing inequalities in access to health services; addressing contextual risk factors; and supplementing curative medicine in hospitals with close-to-community prevention, health promotion and rehabilitation. The ESF is responsible for referral to other levels of care in the SUS. ESF interventions are undertaken by teams comprising general practitioners, nurses, nursing assistants and CHWs. There are around 40,000 teams in 80% of Brazilian municipalities, reaching out to 65% of families (Ministério da Saúde, Citation2020). The programme relies heavily on the frontline work of CHWs. CHWs bridge the health system and its users, referring the latter to different levels of service. Their responsibilities also include: health education and promotion; keeping records of individuals and families in their area, and identifying those at risk; making regular household visits to monitor the vaccination of children or the welfare of chronic patients; scheduling maternal health appointments; advising on the use of medication; and contributing to mosquito-control campaigns (Ministério da Saúde, Citation2012).

Data collection

The study was conducted in 2019. Since we intended to analyse how CHWs perceived users from vulnerable backgrounds, we selected CHWs in three primary health clinics in regions with the lowest Human Development Indexes in the city of São Paulo. All participants were volunteers in the research. They correspond to 50% of the CHWs in each clinic and were selected based on their interest and availability to be interviewed. The research was approved by the research ethics committee of the Municipal Secretariat of Health of São Paulo (process number 3.207.107), and the interviewees signed a consent form guaranteeing their anonymity.

We used two data collection strategies: interviews and vignettes. Interviews (26 in total) aimed at exploring the profile and professional trajectory of CHWs. They included questions about gender, age, religion, experience and training.

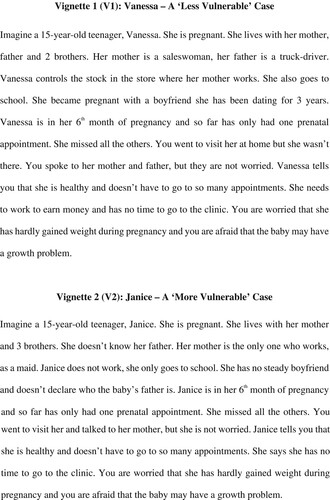

Vignettes sought to assess the extent to which, when faced with limited or ambiguous information, CHWs drew on their own perceptions and assumptions to construct health system users and justify courses of action. We assessed whether the presence of indicators associated with socioeconomic vulnerability altered CHW perceptions of health system users and led to different social construction processes, thus changing how CHWs interpreted cases and their referrals to other services. We designed two vignettes with the same situation – a pregnant teenager refusing to do pre-birth assessment – but different socioeconomic conditions. The description of the context was clear, but the problem was purposely presented in an ambiguous way, so that CHWs could imagine different reasons for the user’s refusal to do the exam. The difference between the two vignettes rests in the presence or absence of markers that are commonly perceived in Brazilian society as indications or causes of vulnerability (Bello, Citation2016): unemployment or precarious employment; large size of household; unstable relationships. Thus, our vignettes included references to: family environment (biparental; single-parent); professional background (professions that could be identified with the lower-middle class; professions that could be identified with the working class; job situation of the teenager); and the child’s paternity (teenager has a relationship with the father; teenager does not declare who the father is). One of the cases included fewer indicators normally associated with vulnerability (the ‘less vulnerable’ case, V1) and another had more (the ‘more vulnerable’ case, V2). Vignettes were designed after exploratory interviews with five CHWs and previous ethnography conducted in 2018, during which a team with four CHWs was followed for two months to observe their interactions with families. Vignettes were also tested with three CHWs ().

One vignette was randomly selected at the end of each interview. This process meant that vignettes were evenly distributed among participating CHWs. After reading the vignette out loud, we asked: what would you do in this case? Some CHWs started interpreting the case before stating their referrals, and some went straight to the referrals. We asked for elaboration if the answer was unclear or too short.

We recognise that in vignette studies (as in other qualitative studies) the researcher may interfere in the answers given by interviewees, who may feel tempted to provide answers on the basis of what they deem to be correct or appropriate. To minimise this possible problem, we carefully worded the vignettes, and presented the study in a way that deliberately sought to avoid any indication that there was a right or wrong answer to our questions. The interviews were conducted by researchers with an extensive experience in interviewing CHWs.

Our use of vignettes draws from previous analyses of social constructions of citizens by frontline workers, their perceptions and use of stereotypes including class-based ones (Harrits, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Harrits & Møller, Citation2014; Terum et al., Citation2018).

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed. We drew on the macrocodes of the interviews (sociodemographic profile of the CHW, Vignette 1, Vignette 2) and made an axial analysis based on two codes: interpretations (how interviewees interpreted the case) and referrals. We then conducted a grounded analysis, building a typology of four interpretations and seven referrals. Referrals were aggregated into two groups: persuasion and intervention. Finally, to study the reasonings used by CHWs, we analysed the relationship between interpretations and referrals.

Findings: Interpretations, referrals and reasonings of Brazilian CHWs

Profile of participants

All participants were women. Twenty-two of the interviewees were mothers and their average age was 40 years old. There are more women than men in the Brazilian CHW programme, with percentages above 75% and in some regions up to 95% (Musse et al., Citation2015; Simas & Pinto, Citation2017). Four interviewees became CHW less than four years before the study, and the rest had been working as CHWs between 4 and 18 years. Only seven interviewees had taken specific training prior to becoming CHW, and only two had previous work experience in the health sector (as nursing assistant or administrative staff). This confirms a long-standing problem in the SUS with CHW training, which is overwhelmingly fragmented, unsystematic, uneven across the country and often deployed when CHWs are already on the job (Morosini, Citation2010). Participants also had a long-standing connection with the territory where they worked: 20 of them lived in the same place for more than 20 years. Eleven interviewees were regular churchgoers, catholic or evangelical.

Interpretations

Looking at how CHWs ‘filled in the blanks’ in the vignettes allowed us to explore how they interpreted the situation, and the extent to which interpretation happened alongside the social construction of health system users. shows the interpretations mobilised by CHWs and their incidence for each vignette.

Table 1. CHW interpretations and their incidence.

For CHWs, the interpretation of V1 appeared straightforward: it was a case of a ‘typical’ teenager behaviour. V2, the vignette mobilising more indicators of vulnerability, opened the door to socioeconomic, cultural and moral considerations that went beyond what was explicitly described in the vignette. Some of these – for example, references to absent or inadequate family support – were more obvious given how the vignette was presented. Others resulted from the interpretation of CHWs – for example, references to drug use and mental health. The inclusion of more indicators associated with vulnerability in V2 made CHWs associate the original situation (a pregnant teenager refusing to do pre-birth assessment) with other problems that did not emerge as relevant in interpretations of V1. V2 led CHWs to activate moral judgments (problems derived from a so-called ‘unstructured’ family, that is, a family that does not conform to the heteronormative nuclear family ideal; two instances); and judgments about other pathologies such as drug use (3) and psychological problems (1). When markers associated with vulnerability were introduced, CHWs tended to bring in other underlying issues, even if these were not mentioned. For CHWs, a pregnant teenager with socioeconomic vulnerabilities is likely to be associated with drug use, lack of parental guidance or psychological issues.

Referrals

We analysed whether different interpretations would lead CHWs to different referrals to other levels of service in the health system and beyond. Referrals were synthesised in a grounded way, based on what CHWs mentioned they would do in each case. shows the referrals mentioned and their incidence for each vignette.

Table 2. Referrals and their incidence.

In V1, the ‘less vulnerable’ case, the main strategy is to convince the teenager (nine times), or to introduce flexibilities in the opening times of the clinic, so that the patient can come in and take the exam (4). This approach is respectful of the patient’s (assumed) circumstances, right to choose and agency. The underlying assumption is that this is a responsible and conscious user, who has the right to access the service; and that the health system needs to be accommodating of the circumstances of the user.

In V2, the most cited strategy was the enforcement of exams in the user’s own home (9), and the mobilisation of a multidisciplinary team including psychologists and social workers, as the regular ESF team (comprising CHWs, doctors and nurses) was not deemed enough to reach a solution (9). In some cases (3), the situation was considered so serious that it required support outside the health system, namely drug abuse services or centres dealing with ‘problematic’ youth (3). While attempts at persuasion (5) and the mobilisation of the ESF team (4) were mentioned, the strategy for persuasion was not the most important in CHW referrals for V2. CHWs did not mention the possibility of bringing in the teenager to the clinic, even in flexible times. Thus, even if the health condition was the same, V2 was perceived by CHWs as a much more complex case, demanding more authoritative, invasive and encompassing strategies. This user was constructed by the CHW as irresponsible and helpless, someone who needed others to make decisions. The agency of the user, that is, their ability to decide what is best for them, was underplayed.

Persuasion and intervention

Referrals were aggregated into two types: persuasion and intervention. Practices of persuasion are ordinary CHW activities: providing information; answering questions; explaining different options; promoting prescribed treatment adherence. Practices of intervention include activities that take the case outside the primary healthcare team or that interfere directly with the patient’s choices and body (such as enforcing exams). Persuasion practices are respectful of patients’ agency and choices, whereas intervention is based on the paternalistic assumption that CHWs know best and must make decisions to protect users (sometimes even from themselves). The following excerpts from interviews exemplify the different approaches:

Persuasion: I would make my visit normally. I would suggest a new appointment, and advise the patient about the importance of her coming to the consultations, taking the vaccines correctly. We cannot force her or bring her in [if] the patient that doesn’t want this. So, I would try to convince her. (Interview 8, V1)

Intervention: Since she does not want to take the exams, we would have to go to her house, take the doctor with us and make the consultations at home. All the exams have to be done, right? So, I would do it anyway inside her house especially because she is a teenager, and this is very complicated. (Interview 22, V2)

Table 3. Types of referrals and their incidence.

Persuasion practices were more significant for V1, the ‘less vulnerable’ case, with 10 CHWs suggesting attempts at persuading the patient or the family. In V2, only five CHWs thought this was the best course of action. Fourteen CHWs thought that intervention was the best strategy for dealing with V2 – whereas only five would use intervention practices for V1. Overwhelmingly, CHWs thought that V2 was a more complex case where persuasion was insufficient and strategies of intervention were required.

Reasoning processes

The reasoning process of CHWs can be discerned by observing how they constructed users, and how they articulated interpretations and referrals for each case. In both cases, there was a general reasoning that, given that the patient was a teenager, she probably had insufficient awareness of the risks involved – in other words, her agency was already impaired to a certain degree. Simultaneously, CHWs assumed that the teenager was showing an attitude, common of this age, of not listening and not caring about their own health. Noncompliance was, therefore, seen as a ‘typical’ teenager behaviour. As one CHW put it: ‘I treated girls like this before. This is a typical teenager behavior, they don’t want to comply and they don’t care about anything’ (Interview 17, V1). The strategy suggested was to explain the situation and try to convince the teenager to adhere to the recommended exams. Based on this reasoning, some CHWs advanced a strategy of persuasion of both teenagers and their families. The excerpts below exemplify this reasoning for both vignettes:

I would talk to her mother, also because she is only 15 [years old] and I think that the mother has to be near her, talking to her and showing how important it is to take care of herself. (Interview 12, V1)

I would try to visit her … to talk about the importance of her prenatal consultations, her health, the health of the baby. I would talk about the importance of going to appointments, of taking the exams. I would try to make her more responsible because she’s a teenager. She needs to understand that there is not only her health, there is a baby inside her now. (Interview 26, V2)

In cases like these, we have to guarantee that she will do the treatment. Those who are pregnant have priority. I would even ask to open the clinic in different hours if this is what it takes for her to come. (Interview 9, V1)

In cases like this you can’t change anything. Because the truth is that they don’t have any references from the family. And they just reproduce the bad behavior they see at home. I tell them that they are generating a new life and should, at least, think about the future of that baby. But they don’t listen to us. (Interview 8, V2)

Girls like that are completely lost, and then we have to do everything for them. You cannot leave them alone, otherwise they will get lost. They need to be cared for, rescued. (Interview 10, V2)

This process of reasoning creates a situation in which CHWs come to think that convincing and talking to the teenager will not be enough. They approach the case as one that cannot be solved by relying on the decisions and agency of the patient. Enforcement is required, as is the involvement of a wide array of professionals and services. Intervention in the teenager’s life, and taking decisions away from her, become necessary. The excerpt below shows this reasoning:

I haven’t had Janice, but I had another [user] named Joyce, and her whole family was just like Janice’s (…). She passed out when she was pregnant, because she didn’t want to eat, she vomited all the time, but she wouldn’t stop going to parties, she wouldn’t stop using drugs. Nowadays she rejects this baby. But there’s not much that can be done for Janice (…), the family doesn't help us. And the truth is that these girls reproduce everything [they learn from their family]. Once, I took Joyce on the street, put her [in my car] and brought her to the clinic. Once I also ran after Joyce on the street to hold her and take her blood [for exams]. But we are limited in cases like this. These girls are part of the dark side of the society, the one we pretend not to see. They will give us trouble in the future, because they won’t work, won’t pay taxes for the government, but will receive services. They are totally lost. (Interview 24, V2)

Discussion: CHWs, health system users and the state

Introducing in the vignettes elements of socioeconomic vulnerability alters CHW perceptions of users, and specifically of their agency. Perceptions lead to different social constructions of citizens, which in turn impact upon referrals. When confronted with different degrees of vulnerability, Brazilian CHWs interpret health conditions differently and propose distinct courses of action. This impacts upon how the response is located along a persuasion–intervention spectrum of practices – between, on the one hand, practices that are respectful of patients’ decisions and agency, and, on the other, more paternalistic practices that seek to enforce changes in behaviour and intervene upon the body, even against the will of the patient. Patients perceived as more vulnerable are routinely seen as misguided, often recalcitrant, and unable to decide and act without help. They are ascribed lesser agency and deemed targets of intervention – sometimes involving multidisciplinary teams and the use of force. Meanwhile, those perceived as less vulnerable are considered fully fledged agents requiring persuasion and the introduction of flexibilities into the health system.

Interpretations and referrals of CHWs feed from, and help to reproduce, existing perceptions in Brazilian society about ‘the poor’ or ‘the popular classes’. These groups are commonly perceived, mainly by the elites and the middle classes, as unable to make the right decisions for themselves, frequently involved in criminal or morally reprehensible behaviour, often lazy and with addictive behaviours, and requiring the paternalistic guidance and intervention of the state (Naiff & Naiff, Citation2005; Voigt & Junior, Citation2019). Authors have suggested that Brazilian CHWs, like other frontline workers, reify these perceptions: for example about vulnerable citizens as needy, insufficiently resilient and resigned to poverty, or about the links between vulnerability and the supposed dissolution of the ‘traditional’ and ‘structured’ family (Eiró, Citation2019; Matos et al., Citation2018; Yunes et al., Citation2005, Citation2007). This was confirmed by the present study, with CHWs repeatedly associating single-parent families with ‘unstructured’ and ‘problematic’ backgrounds. As one CHW put it:

the easiest ones to treat are those families with a mother, a father, and children. It is easier because they work, they take care of themselves, and normally do not even have any disease. (Interview 9, V1)

What is at stake is not simply state control or repression of those deemed vulnerable, nor is it their abandonment or marginalisation in the name of a sanitised social order, as has been argued in other contexts (Biehl, Citation2005; Nisar & Masood, Citation2019). Our findings suggest that CHW perceptions help to shape access to health services, functioning as discretionary instruments in the traditional gatekeeping role that Brazilian CHWs de facto play (even if they are not officially mandated or trained to do so). Wide-reaching state interventions, as recommended for some users, reinforce a particular kind of relationship between the state and the citizen that also functions as a tool of differentiation of citizens. Those considered more vulnerable are brought into the remit of intervention of the state and the health system. This relationship, based on the underplaying of agency and, sometimes, on forcible interventions upon bodies, is markedly different from a more flexible and accommodating relationship, one respecting individual choices and circumstances, which emerged in CHW responses to V1.

The implementation of primary healthcare policies in Brazil can lead to paternalism, condescendence and the reproduction of the dependency of more vulnerable users. This can be explained in part by the goals of the ESF, the primary health strategy in which CHWs are embedded, which sees the alleviation of poverty as one of its fundamental purposes. Those considered vulnerable are not to be sanitised or excluded – rather, they must be welcome into the system, protected and cared for. Differences in CHW perceptions and referrals thus emerge as unintended consequences of well-intentioned efforts to improve the situation of users deemed vulnerable (Eiró, Citation2019; Nunes & Lotta, Citation2019). They are the side-effect of day-to-day judgments and practices in frontline implementation, as CHWs are faced with the need to make decisions in challenging circumstances. The work of frontline policy implementers is characterised by a great degree of discretion (Lipsky, 1980/Citation2010). Faced with scarce resources, inadequate training and lack of coordination, many frontline workers resort to pragmatic improvisations to fulfil their role (Maynard-Moody & Musheno, Citation2003; Maynard-Moody & Musheno, Citation2012). To great extent, these improvisations draw upon social and cultural prejudices, as well as personal moral codes (Harrits & Møller, Citation2014). The present study shows that perceptions of user vulnerability give frontline workers leeway to exercise their discretion in the social construction of users, paving the way for forceful interventions when users are constructed as irresponsible and helpless.

We are aware of the limitations of vignette-based studies. As representations of encounters, they do not enable us to see what would happen in a real encounter, which would necessarily occur in a more complex context. We only claim to have identified general tendencies in CHW perceptions, interpretations and reasonings. Vignettes based on real-life situations that closely match the cases CHWs encounter in day-to-day interactions are extremely useful for understanding how interviewees perceive and interpret their reality. Moreover, by asking them to explain and justify the choices they make, we were able to shed further light on the reasoning process that supports these decisions. Therefore, our methodology, however imperfect, yields useful data for understanding the patterns of perception, interpretation and reasoning underpinning the decisions of CHWs, and specifically the processes of construction of users therein.

Another limitation of the design of our study is that we did not cross-reference CHW responses with differences in their socioeconomic profile. Again, our goal was to analyse general patterns in the perception, interpretation and reasoning process of CHWs, and not to discern if and how this process is influenced by the socioeconomic profile and trajectory of CHWs. By analysing the extent to which these variables influence perceptions, interpretations and reasonings of CHWs, future studies would add further layers of complexity to the argument presented here.

Conclusion

The less benign impact of CHW programmes has remained relatively underexplored. Assessments of the impact of CHW programmes must consider the pitfalls and unintended effects of these programmes. Speaking to the need to know more about the ways in which the design and/or implementation of CHW programmes can be counterproductive or complicit in the very inequalities these set out to redress, this article showed the importance of considering the perceptions of CHWs and how these lead to different social constructions of citizens. These social constructions impact upon CHW referrals to other levels of service. Different referrals – on the one hand, to practices based on persuasion and respect for individual agency and choice; on the other hand, to ‘top-down’ or forcible interventions – were shaped by judgments on the part of CHWs about the users they interacted with. The implementation of primary healthcare policy – its respect for individual choice, its degree of paternalism or the extent to which it leads to forcible interventions – is greatly influenced by the perceptions of CHWs, how they construct users, and the decisions or referrals they make on the basis of these constructions.

Brazilian CHWs participate in social construction processes that underplay the agency of some users, thus legitimising a more intense – and possibly more violent – state and medical intervention upon their bodies. Even if sometimes unwittingly or unconsciously, CHWs reproduce societal conceptions like the stigma surrounding ‘unstructured’ families, drug use or psychological problems. Some users are thus defined as objects of intense state and medical scrutiny, one in which condemnation is interlinked with paternalistic intervention. As one of our participants put it, some people need to be ‘rescued’ (Interview 10, V2). Brazil’s primary health policy, while ostensibly seeking to address vulnerabilities, ends up reproducing stereotypes about ‘the vulnerable’ as having impaired agency and requiring permanent intervention – thus ultimately reproducing some of the conditions of their continued dependency. By emphasising the salvific nature of health workers vis à vis helpless citizens, these paternalistic assumptions are at odds with the health system’s goal of promoting empowerment and the alleviation of deep-seated inequalities.

CHW programmes are important for addressing the health problems of low- and middle-income countries, as well as of vulnerable and marginalised groups in high-income countries (Haines et al., Citation2020; Krieger et al., Citation2021). This is true also for Brazil. Realising this potential requires paying close attention to the possible adverse effects of CHW discretion in situations of scarce resources and inadequate training, support and supervision. The informality that underpins the practice of CHWs is to some extent indispensable for ensuring flexibility and responsiveness in frontline policy implementation. However, it needs to be carefully monitored and managed if the public health system is to achieve its goals of improving health and reducing inequality.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the researchers of NEB (Núcleo de Estudos da Burocracia) for their help in data collection. We also thank the anonymous reviewers, whose comments greatly improved our argument. Gabriela Lotta thanks FAPESP for supporting the data collection (Processes 2019/13439-7, CEPID CEM and 2019/24495-5). Lotta also thanks CNPq for the Research Productivity Scholarship (Process 305180/2018-5).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, C. (2020). Toward an institutional perspective on social capital health interventions: Lay community health workers as social capital builders. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12992

- Becker, J., Kovach, A. C., & Gronseth, D. L. (2004). Individual empowerment: How community health workers operationalize self-determination, self-sufficiency, and decision-making abilities of low-income mothers. Journal of Community Psychology, 32(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20000

- Bello, C. A. (2016). Percepções sobre pobreza e Bolsa Família [Perceptions about poverty and the Bolsa Família]. In A. Singer & I. Loureiro (Eds.), As contradições do lulismo: A que ponto chegamos? (pp. 157–183). Boitempo.

- Biehl, J. (2005). Vita: Life in a zone of social abandonment. University of California Press.

- Brady, M. (2018). Targeting single mothers? Dynamics of contracting Australian employment services and activation policies at the street level. Journal of Social Policy, 47(4), 827–845. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279418000223

- Collins, M. E., & Mead, M. (2021). Social constructions of children and youth: Beyond dependents and deviants. Journal of Social Policy, 50(3), 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279420000239

- Cook, T., & Wills, J. (2011). Engaging with marginalized communities: The experiences of London health trainers. Perspectives in Public Health, 132(5), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913910393864

- Davlantes, E., Salomao, C., Wate, F., Sarmento, D., Rodrigues, H., Halsey, E. S., Lewis, L., Candrinho, B., & Zulliger, R. (2019). Malaria case management commodity supply and use by community health workers in Mozambique, 2017. Malaria Journal, 18, 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-2682-5

- Dembo, E. (2012). Community health workers’ perceptions of barriers to utilisation of malaria interventions in Lilongwe, Malawi: A qualitative study. MalariaWorld Journal, 3(11), 1–12.

- Eiró, F. (2019). The vicious cycle in the Bolsa Família program’s implementation: Discretionality and the challenge of social rights consolidation in Brazil. Qualitative Sociology, 42(3), 385–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-019-09429-9

- Haines, A., de Barros, E. F., Berlin, A., Heymann, D. L., & Harris, M. J. (2020). National UK programme of community health workers for COVID-19 response. The Lancet, 395(10231), 1173–1175. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30735-2

- Harrits, G. S. (2019a). Stereotypes in context: How and when do street-level bureaucrats use class stereotypes? Public Administration Review, 79(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12952

- Harrits, G. S. (2019b). Using vignettes in street-level bureaucracy research. In P. Hupe (Ed.), Research handbook on street-level bureaucracy (pp. 392-408). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Harrits, G. S., & Møller, MØ. (2014). Prevention at the front line: How home nurses, pedagogues, and teachers transform public worry into decisions on special efforts. Public Management Review, 16(4), 447–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.841980

- Hartzler, A. L., Tuzzio, L., Hsu, C., & Wagner, E. H. (2018). Roles and functions of community health workers in primary care. The Annals of Family Medicine, 16(3), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2208

- Ingram, M., Chang, J., Kunz, S., Piper, R., de Zapien, J. G., & Strawder, K. (2016). Women’s health leadership to enhance community health workers as change agents. Health Promotion Practice, 17(3), 391–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839916637047

- Ingram, M., Schachter, K. A., Sabo, S. J., Reinschmidt, K. M., Gomez, S., De Zapien, J. G., & Carvajal, S. C. (2014). A community health worker intervention to address the social determinants of health through policy change. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 35(2), 119–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-013-0335-y

- Kibe, L. W., Habluetzel, A., Gachigi, J. K., Kamau, A. W., & Mbogo, C. M. (2019). Exploring communities’ and health workers’ perceptions of indicators and drivers of malaria decline in Malindi, Kenya. MalariaWorld Journal, 8(21), 1–10.

- Kok, M. C., Kane, S. S., Tulloch, O., Ormel, H., Theobald, S., Dieleman, M., Taegtmeye, M., Broerse, J. E. W., de Koning, K. A. M. (2015). How does context influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? Evidence from the literature. Health Research Policy and Systems, 13(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0001-3

- Krieger, M. G. M., Wenham, C., Nacif Pimenta, D., Nkya, T. E., Schall, B., Nunes, A. C., De Menezes, A., Lotta, G. (2021). How do community health workers institutionalise: An analysis of Brazil’s CHW programme. Global Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1940236

- Larson, E., Geldsetzer, P., Mboggo, E., Lema, I. A., Sando, D., Ekström, A. M., Fawzi, W., Foster, D. W., Kilewo, C., Li, N., Machumi, L., Magesa, L., Mujinja, P., Mungure, E., Mwanyika-Sando, M., Naburi, H., Siril, H., Spiegelman, D., Ulenga, N., Bärnighausen, T. (2019). The effect of a community health worker intervention on public satisfaction: Evidence from an unregistered outcome in a cluster-randomized controlled trial in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Human Resources for Health, 17(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-019-0355-7

- Lehmann, U., & Gilson, L. (2013). Actor interfaces and practices of power in a community health worker programme: A South African study of unintended policy outcomes. Health Policy and Planning, 28(4), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs066

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service (30th Anniversary Ed.). Russell Sage Foundation. (Original work published 1980).

- Lotta, G. S., & Marques, E. C. (2020). How social networks affect policy implementation: An analysis of street-level bureaucrats’ performance regarding a health policy. Social Policy & Administration, 54(3), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12550

- Lotta, G. S., & Pires, R. R. C. (2020). Categorizando Usuários “Fáceis” e “Difíceis”: Práticas Cotidianas de Implementação de Políticas Públicas e a Produção de Diferenças Sociais [Categorizing "easy" and "difficult" users: Everyday practices of implementation of public policy and the production of social differences]. Dados, 63(4). https://doi.org/10.1590/dados.2020.63.4.219

- Matos, L. A., Cruz, E. J. S. D., Santos, T. M. D., & Silva, S. S. C. (2018). Resiliência Familiar: o olhar de professores sobre famílias pobres [Family resilience: Teachers' views of poor families]. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 22(3), 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-35392018038602

- Maynard-Moody, S., & Musheno, M. (2003). Cops, teachers, counselors: Stories from the front lines of public service. University of Michigan Press.

- Maynard-Moody, S., & Musheno, M. (2012). Social equities and inequities in practice: Street-level workers as agents and pragmatists. Public Administration Review, 72(S1), S16–S23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02633.x

- Ministério da Saúde. (2012). Política Nacional da Atenção Básica.

- Ministério da Saúde. (2020). Portal da Secretaria de Atenção Primária à Saúde. Retrieved October 1, 2020, from https://aps.saude.gov.br/.

- Mlotshwa, L., Harris, B., Schneider, H., & Moshabela, M. (2015). Exploring the perceptions and experiences of community health workers using role identity theory. Global Health Action, 8(1), 28045. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.28045

- Morosini, M. V. (2010). Educação e trabalho em disputa no SUS: a política de formação dos agentes comunitários de saúde [Education and work under dispute in the SUS: The training policy of community health workers]. Escola Politécnica de Saúde Joaquim Venâncio/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz.

- Musse, J. D. O., Marques, R. S., Lopes, F. R. L., Monteiro, K. S., & Santos, S. C. D. (2015). Avaliação de competências de Agentes Comunitários de Saúde para coleta de dados epidemiológicos [Evaluation of skills of community health workers in epidemiological data collection]. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 20(2), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015202.01212014

- Naiff, L. A. M., & Naiff, D. G. M. (2005). A favela e seus moradores: culpados ou vítimas? Representações sociais em tempos de violência [The favela and its dwellers: guilty or victims? Social representations in times of violence]. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, 5(2), 107–119.

- Nisar, M. A., & Masood, A. (2019). Dealing with disgust: Street-level bureaucrats as agents of kafkaesque bureaucracy. Organization. 27(6), 882–899. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508419883382.

- Nunes, J. (2019). The everyday political economy of health: Community health workers and the response to the 2015 Zika outbreak in Brazil. Review of International Political Economy, 27(1), 146–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1625800

- Nunes, J., & Lotta, G. (2019, December). Discretion, power and the reproduction of inequality in health policy implementation: Practices, discursive styles and classifications of Brazil’s community health workers. Social Science & Medicine, 242, 112551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112551

- Olaniran, A., Smith, H., Unkels, R., Bar-Zeev, S., & Broek, N. V. D. (2017). Who is a community health worker? – A systematic review of definitions. Global Health Action, 10(1), 1272223. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1272223

- Oliver, M., Geniets, A., Winters, N., Rega, I., & Mbae, S. M. (2015). What do community health workers have to say about their work, and how can this inform improved programme design? A case study with CHWs within Kenya. Global Health Action, 8(1), 27168. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.27168

- Onwujekwe, O., Dike, N., Ojukwu, J., Uzochukwu, B., Ezumah, N., Shu, E., & Okonkwo, P. (2006). Consumers stated and revealed preferences for community health workers and other strategies for the provision of timely and appropriate treatment of malaria in southeast Nigeria. Malaria Journal, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-5-117

- Pérez, L. M., & Martinez, J. (2008). Community health workers: Social justice and policy advocates for community health and well-being. American Journal of Public Health, 98(1), 11–14. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2006.100842

- Rowlingson, K., & Connor, S. (2011). The ‘deserving’ rich? Inequality, morality and social policy. Journal of Social Policy, 40(3), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279410000668

- Schneider, A., & Ingram, H. (1993). Social construction of target populations: Implications for politics and policy. American Political Science Review, 87(2), 334–347. https://doi.org/10.2307/2939044

- Schneider, H., & Lehmann, U. (2016). From community health workers to community health systems: Time to widen the horizon?. Health Systems & Reform, 2(2), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2016.1166307

- Schneider, H., & Nandi, S. (2014). Addressing the social determinants of health: A case study from the Mitanin (community health worker) programme in India. Health Policy and Planning, 29(suppl_2), ii71–ii81. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czu074

- Scott, K., George, A. S., Harvey, S. A., Mondal, S., Patel, G., & Sheikh, K. (2017). Negotiating power relations, gender equality, and collective agency: Are village health committees transformative social spaces in northern India?. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0580-4

- Shet, A. S., Rao, A., Jebaraj, P., Mascarenhas, M., Zwarenstein, M., Galanti, M. R., & Atkins, S. (2017). Lay health workers perceptions of an anemia control intervention in Karnataka, India: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3954-4

- Simas, P. R. P., & Pinto, I. C. D. M. (2017). Trabalho em saúde: retrato dos agentes comunitários de saúde da região Nordeste do Brasil [Health work: Profile of community health workers of the Northeast region of Brazil]. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 22(6), 1865–1876. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232017226.01532017

- Singh, P., & Chokshi, D. A. (2013). Community health workers – A local solution to a global problem. New England Journal of Medicine, 369(10), 894–896. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1305636

- Takasugi, T., & Lee, A. (2012). Why do community health workers volunteer? A qualitative study in Kenya. Public Health, 126(10), 839–845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2012.06.005

- Teo, Y. (2015). Differentiated deservedness: Governance through familialist social policies in Singapore. TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia, 3(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1017/trn.2014.16

- Terum, L. I., Torsvik, G., & Øverbye, E. (2018). Discrimination against ethnic minorities in activation programme? Evidence from a vignette experiment. Journal of Social Policy, 47(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279417000113

- Tine, R. C., Ndiaye, P., Ndour, C. T., Faye, B., Ndiaye, J. L., Sylla, K., Ndiaye, M., Cisse, B., Sow, D., Magnussen, P., Bygbjerg, I. C., & Gaye, O. (2013). Acceptability by community health workers in Senegal of combining community case management of malaria and seasonal malaria chemoprevention. Malaria Journal, 12(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-12-1

- Tulenko, K., Mgedal, S., Afzal, M. M., Frymus, D., Oshin, A., Pate, M., Quain, E., Pinel, A., Wynd, S., & Zodpey, S. (2013). Community health workers for universal health-care coverage: From fragmentation to synergy. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 91(11), 847–852. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.13.118745

- Voigt, L., & Junior, V. L. P. (2019). O ‘racismo de classe’: Representações elitistas sobre os pobres e a pobreza no Brasil ["Class racism": Elite representations of the poor and of poverty in Brazil]. Mediações - Revista de Ciências Sociais, 24(2), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.5433/2176-6665.2019v24n2p227

- Wiggins, N., Johnson, D., Avila, M., Farquhar, S. A., Michael, Y. L., Rios, T., & Lopez, A. (2009). Using popular education for community empowerment: Perspectives of community health workers in the Poder es Salud/power for health program. Critical Public Health, 19(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590802375855

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes.

- Yunes, M. A. M., Garcia, N. M., & Albuquerque, B. D. M. (2007). Monoparentalidade, pobreza e resiliência: Entre as crenças dos profissionais e as possibilidades da convivência familiar [Single-parenthood, poverty and resilience: between the beliefs of professionals and the possibilities for family coexistence]. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 20(3), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722007000300012

- Yunes, M. A. M., Mendes, N. F., & Albuquerque, B. D. M. (2005). Percepções e crenças de agentes comunitários de saúde sobre resiliência em famílias monoparentais pobres [Perceptions and beliefs of community health workers about resilience in poor single-parent families]. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem, 14, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-07072005000500003