Abstract

In March 2018, the IASB published its revised conceptual framework including notable changes to the chapters on the objective of financial reporting and on qualitative characteristics. The IASB put more emphasis on stewardship as part of the decision usefulness objective, reintroduced prudence as an aspect of neutrality and introduced a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty (as a successor to reliability) as part of faithful representation. The present paper discusses the substance of and reasons for these changes in light of the history of the IASB’s work on conceptual frameworks. The paper also explores the possible impact of these changes on the IASB’s future standard-setting by looking at the other chapters of the IASB’s new framework. This paper finds that the more pronounced role of stewardship and the reintroduction of prudence do not seem to entail a revised conceptual thinking of the IASB in the other chapters, while the introduction of a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty provides the IASB with a conceptual tool with the potential to substantially affect future standard-setting debates. However, its positioning as part of faithful representation is questioned and an alternative arrangement of qualitative characteristics suggested.

1. Introduction

After six years of work on revising its conceptual framework (CF), the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) published a new version in March 2018 (IASB, Citation2018).Footnote1 Consisting of more than 80 pages, the new CF substantially extends the former version from 2010 as it covers new areas, such as financial statements and the reporting entity, derecognition, presentation and disclosure, and also includes prolonged sections on recognition and measurement. The official aim of the document is ‘[to describe] the objective of, and the concepts for, general purpose financial reporting’ (CF2018.SP1.1) in order to, primarily, support the future work of the IASB so that its standards ‘are based on consistent concepts’ (CF2018.SP1.1(a)).Footnote2

In the first two chapters of its CF2018, the IASB outlines what it regards as the objective of financial reporting and how this can be achieved through specific features of accounting information, the so-called qualitative characteristics (QCs). These topics had already been subject to a joint review by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the IASB between 2004 and 2010, leading to the publication of a revised CF in September 2010.Footnote3 Important changes in this document compared to the original CF of the IASB/IASC (International Accounting Standards Committee, Citation1989Footnote4) included the narrowing down of the objective to decision usefulness with a single focus on valuation decisions, not incorporating stewardship as a separate concern (Pelger, Citation2016), the replacement of the major QC ‘reliability’ by ‘faithful representation’ (Erb & Pelger, Citation2015) and the abandonment of prudence that was perceived to conflict with neutrality (Barker, Citation2015).Footnote5

In light of the CF2010, it is noteworthy that all three major decisions taken by the IASB and FASB have now been reversed by the IASB in the CF2018.Footnote6 The terms stewardship and prudence have been taken back into the CF and ‘a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty’ has been introduced as a successor to ‘reliability’.Footnote7 This commentary aims to reflect on the extent to which stewardship, reliability and prudence really experience a revival in the IASB’s CF2018. For this purpose, the study first discusses the recent changes made in the CF2018 against the background of the IASB’s (and FASB’s) prior work on the CF. Second, this paper explores the other chapters in the CF2018 to find indications in the rationale provided by the IASB of how substantial the impact of the changes regarding stewardship, prudence and measurement uncertainty will be on future standard-setting practice.

This paper intends to contribute to current debates on revisions of the IASB’s CF in the academic literature. While several recent articles have addressed topics emerging from the CF revision (e.g. Barker & Teixeira, Citation2018; Barker, Lennard, Nobes, Trombetta, & Walton, Citation2014; Van Mourik, Citation2014; Van Mourik & Katsuo Asami, Citation2018) or the use of the CF in standard-setting (e.g. Brouwer, Hoogendorn, & Naarding, Citation2015; Walton, Citation2018) and practice (e.g. Nobes & Stadler, Citation2015), none of them focuses on the reintroduction of stewardship, reliability and prudence in the CF2018 (or in the IASB’s Citation2015 Exposure Draft (ED)).

While there exist some general reviews on academic research on stewardship (see O’Connell, Citation2007), reliability (Erb & Pelger, Citation2015, p. 15) and prudence (Mora & Walker, Citation2015), some literature has discussed these topics more specifically with respect to the joint IASB/FASB revision. Erb and Pelger (Citation2015) and Pelger (Citation2016) provide qualitative empirical insights into how the IASB and FASB made their decisions with respect to the replacement of reliability and the abandonment of stewardship (also see Camfferman & Zeff, Citation2015, pp. 358–369). Whittington (Citation2008a) and Barth (Citation2014), as former IASB members, provide insider views into how changes in the objective and QCs in the 2010 CF might affect future IFRS. Barker and McGeachin (Citation2015) contrast the IASB’s decision to abandon prudence in the CF2010 with the use of conservative requirements in a multitude of standards in IFRS (also see Wagenhofer, Citation2014, with regard to revenue recognition), while Barker (Citation2015) provides the argument that accounting is inherently conservative and thus the debates on the status of prudence in the CF are largely redundant. In contrast to these studies, the present paper focuses on the most recent decisions taken by the IASB in the CF2018 and uses the extant literature as a basis to assess the changes made.

This paper also complements and updates the comprehensive historical summary on the objective of financial reporting and QCs by Zeff (Citation2013) and other studies tracing the history of decision usefulness (Young, Citation2006) or reliability (Erb & Pelger, Citation2015) in standard-setting. Finally, it provides new insights into the possible implications of the changes to the objective and QCs for future standard-setting. Thereby, the paper intends to provide a basis for future debates on CFs. The IASB points out that ‘[t]he Conceptual Framework may be revised from time to time on the basis of the Board’s experience of working with it’ (CF2018.SP1.4). Therefore, an ongoing academic debate about the concepts is important to provide a foundation for future deliberations of the IASB (also see Dennis, Citation2018).

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the joint IASB/FASB CF revision with respect to the demotion of stewardship, reliability and prudence. Section 3 outlines the reintroduction during the IASB’s CF revision 2012–2018. Then, Section 4 scrutinizes, on the basis of the other chapters of the CF, how the changes made by the IASB in the CF2018 might impact its future standard-setting. Section 5 offers some conclusions.

2. Stewardship, Reliability and Prudence in the CF Revision 2004–2010

The IASB and the FASB aimed at converging their accounting standards since their formal commitment in the Norwalk Agreement in 2002. One aspect of the convergence agenda was to align the basis of standard-setting, i.e. the CFs of the IASB and the FASB (Camfferman & Zeff, Citation2015, p. 359). Thus, the two Boards took the project to revise and converge their CFs on their agendas in 2004. The Boards decided to split up the project into eight phases (phases A to H), dealing with different parts of the CF. This approach was meant to enable the Boards to achieve progress relatively quickly compared to a comprehensive revision project (Whittington, Citation2008b).

The Boards started to work on phase A which covered the objective of financial reporting and the QCs, arguably the most general parts of the CF. It was assumed that agreement on these aspects could be achieved rather easily and that, on this basis, more controversial issues, on recognition, presentation, and, in particular, measurement, could be discussed in more depth (Whittington, Citation2008a). The phased approach was also in line with the idea that the later chapters should ‘flow from’ the objective and the QCs (Johnson, Citation2004; for a critical view on this idea see Dennis, Citation2018).

The following points constituted the major changes from the joint revision project, manifested in the CF2010:

Stewardship was not included as a separate objective of financial reporting. Instead, decision usefulness with a sole focus on valuation decisions was stated as the single objective of financial reporting (CF2010.OB2). Stewardship issues were said to be encompassed automatically in such an objective without the need to be stated separately (CF2010.BC1.26). The CF mentioned that in order to form assessments of future cash flow prospects information is needed about ‘how efficiently and effectively the entity’s management and governing board have discharged their responsibilities to use the entity’s resources’ (CF2010.OB4). While this captures the notion of stewardship, it was decided not to take up the term ‘stewardship’ ‘because there would be difficulties in translating it’ (CF2010.BC1.28). This approach was in notable contrast to the former IASC/IASB CF where stewardship was mentioned as a separate objective next to decision usefulness (IASC, Citation1989, par. 14).Footnote8

The QC ‘reliability’ was replaced by ‘faithful representation’, consisting of the subcomponents of completeness, neutrality and freedom from error (CF2010.QC12-16). This replacement was in contrast to both former IASB/FASB CFs where reliability, together with relevance, was stated as a major QC (IASC, Citation1989, par. 31; FASB, Citation1980, par. 58).

The characteristic of prudence was eliminated from the CF. In the former IASC/IASB CF it had been a sub-characteristic of reliability (IASC, Citation1989, par. 37), while in the former FASB CF ‘conservatism – meaning prudence’ (FASB, Citation1980, par. 92) had been discussed in the context of reliability without forming an explicit QC (FASB, Citation1980, par. 91–97).

The due process leading to this change consisted of a Discussion Paper (DP), published in 2006 (IASB, Citation2006), and an Exposure Draft (ED), published in 2008 (IASB, Citation2008). The proposals in the DP, reflecting the majority views of the Boards,Footnote9 largely resembled the final changes in the CF2010. However, there was strong opposition by constituents to the proposed changes. For example, in the case of reliability more than 90% of IASB and FASB’s constituents objected to its replacement by faithful representation in the way suggested in the DP (Erb & Pelger, Citation2015, p. 28). While a similar level of resistance was found with respect to stewardship, this was predominantly coming from the IASB’s constituents (Pelger, Citation2016, p. 61). This negative feedback led the Boards to incorporate some of the criticism in the ED. In particular, stewardship was elevated to the status of an objective next to valuation usefulness (but within the broader decision usefulness objective). However, this solution was only short-lived as the final CF2010 went back to the approach of the DP. The reasons for this, in particular, were the powerful (and dominant) position of FASB and IASB members from the US who were able to assert their positions in spite of broad opposition by constituents (and some IASB members). Pelger (Citation2016), pp. 66–68, shows that, for the case of stewardship, it was in particular the final ‘drafting period’ in which some staff and FASB and IASB members, who were convinced that stewardship should not be a separate objective (and that the CF should not allow for any reading in that way), pushed for the abandonment of stewardship as a separate concern.

The CF revision, culminating in the 2010 publication, reflects a ‘fair value view’ in line with a stronger orientation towards (full) fair value accounting (Whittington, Citation2008a, p. 157). It has been claimed in the literature that the changes to the CF were made with that purpose (O’Brien, Citation2009; Power, Citation2010) and empirical accounts of the Boards’ decision-making indeed show that at least some Board members pursued the replacement of reliability because they wanted to eliminate a hindrance, ‘a stumbling block on the road to pushing fair value’ (IASB member quoted in Erb & Pelger, Citation2015, p. 31). In a similar vein, Barth (Citation2014) very explicitly outlines that, in her view, fair value accounting emerges as the preferred measurement basis (compared to historical cost and modified historical cost) from an analysis of the objective and QCs as stated in the IASB’s CF2010.

In contrast to their initial expectations, the Boards found the completion of phase A of the CF revision far from easy. Not only did it take six years to finish this phase but also substantial conflicts emerged among the Board members and between the Boards and their constituents with respect to fundamental issues of financial reporting. Due to the difficulties in phase A and the continuing pressures emerging from the financial crisis, in particular the revision of the financial instruments standard and other major convergence projects, the Boards decided in 2010 not to continue with their joint work on the CF. Even phase D on the reporting entity, for which an ED had already been published in 2010, was put on hold.Footnote10

In 2011/2012 the IASB carried out its first agenda consultation. One of the central messages received by its constituents was that the IASB should continue with the CF revision (Pelger & Spieß, Citation2017). When putting the CF project back on its agenda in May 2012, the IASB decided to continue the project without the FASB. This reflected the difficulties that the two Boards experienced in phase A, outlined above, and increasing difficulties in the convergence program more generally.

3. Stewardship, Prudence and Reliability in the CF Revision 2012–2018

Initially, the IASB proposed in its DP, published in July 2013, not to change the chapters on the objective of financial reporting and QCs as these had just been overhauled in the joint project of the IASB and FASB (IASB, Citation2013, par. 1.9.2). However, the constituents’ responses to the DP gave the IASB the very clear message that some changes were expected (CF2018.BC1.2, BC2.2), in particular because ‘the convergence strategy [with the FASB] is at an end’ (Barker et al., Citation2014, p. 176).

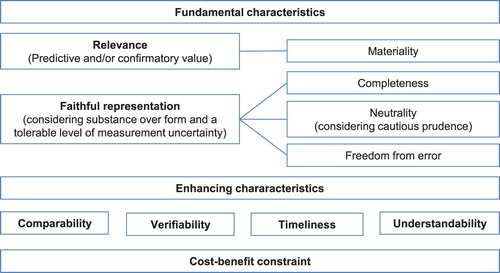

The IASB followed these demands and in the ED, published in May 2015, suggested revisions to the two general chapters of the CF. First, stewardship was explicitly mentioned and received more emphasis as part of the objective of financial reporting. Second, cautious prudence was taken up as a sub-characteristic of neutrality. Third, a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty, intended to capture the meaning traditionally attributed to the prior notion of reliability, was introduced as a new sub-aspect of the fundamental QC ‘relevance’. All these changes were taken through to the final CF – with the exception of a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty that was repositioned to form part of faithful representation instead of relevance – and will be discussed individually in more depth below.Footnote11

3.1. Stewardship

In Chapter 1 of the CF2018 on the objective of financial reporting the IASB reemphasizes that providing decision useful information for resource allocation decisions is the one and only objective of IFRS (CF2018.1.2). Therefore, the objective generally remains unaltered compared to the CF2010. However, the IASB somewhat broadens its understanding of resource allocation decisions as this is not only meant to include buying, selling, holding decisions or decisions about providing or settling loans but also ‘exercising rights to vote on, or otherwise influence, management’s actions that affect the use of the entity’s economic resources’ (CF2018.1.2(c)). Such decisions, which might be termed ‘stewardship decisions’, encompass decisions about management’s remuneration or the reappointment or replacement of management that are particularly relevant for the current owners of an entity (CF2018.BC1.36).Footnote12

It is noteworthy that the IASB argues in CF2018.BC1.37 that it never intended a narrow definition of resource allocation decisions which would exclude such stewardship decisions. This somewhat differs from the account by Pelger (Citation2016), pp. 66–68, who shows that the reference to ‘resource allocation decisions’, instead of the broader term ‘decisions’ (that was still used in the ED from 2008), was incorporated deliberately in the CF2010 during the drafting phase in order to avoid a possible reading of two types of decisions (valuation and stewardship decisions) and thus two separate objectives. Pelger (Citation2016) also suggests that this decision was driven by the strong views of FASB members and IASB members from the US against a stewardship objective and by the staff, responsible for drafting the final CF, sharing these views.

In its further discussion of the objective in the CF2018, the IASB explicitly takes up the term ‘stewardship’ (CF2018.1.3). It is highlighted that in addition to assessments about future cash flows, assessments about management’s stewardship are key in forming an expectation about the return, for example, from an investment in the firm (CF2018.1.3). This is a change to the former CF where information about stewardship were said to be relevant in forming assessments of future cash flows (CF2010.OB4), while the two types of assessments are now positioned on an equal level.Footnote13 ‘That extra prominence [of stewardship] contributes to highlighting management’s accountability to users for economic resources entrusted to their care’ (CF2018.BC1.34).

The reformulation in the CF2018 is a clever twist that is supposed to reflect more emphasis on stewardship concerns without changing the general objective – providing useful information for resource allocation decisions. While the IASB’s efforts to include stewardship in this objective are clearly visible, it is still maintained that stewardship should not be a separate objective – as it was in the CF1989 – because ‘assessing management’s stewardship is not an end in itself: it is an input needed in making resource allocation decisions’ (CF2018.BC1.35(a)).Footnote14 This argument is not substantiated as the IASB does not specify why assessing stewardship might not be an independent concern. The history of accounting informs us that stewardship (or accountability) has been a core motivation to keep accounts and to publish them (e.g. Mattessich, Citation1987; Soll, Citation2014; Williamson & Lipman, Citation1991). Moreover, ignoring separate stewardship concerns is at odds with findings from accounting research. Theoretical works have repeatedly questioned whether information needed for valuation decisions in capital markets are the same as for stewardship decisions (e.g. see Gjesdal, Citation1981; Kuhner & Pelger, Citation2015; Paul, Citation1992). Such fundamental issues are not addressed by relabeling the stewardship decisions as a subgroup of resource allocation decisions.

3.2. Prudence

Prudence is reintroduced in the CF2018 as part of neutrality, one of the subaspects of faithful representation. It is stated that ‘[n]eutrality is supported by the exercise of prudence’, while prudence is defined as ‘the exercise of caution when making judgments under conditions of uncertainty’ (CF2018.2.16). The reintroduction of prudence is a reaction to confusion that the IASB perceived to have been caused by its abandonment in the CF2010 (CF2018.BC2.40).

While the definition of cautious prudence is similar to the one already employed in the CF1989 (IASC, Citation1989, par. 37), prudence is now positioned differently. Like neutrality, prudence was a subcomponent of reliability. Indeed, in the CF1989 the IASB presents a description of neutrality (IASC, Citation1989, par. 36) and then continues: ‘The preparers of financial statements do, however, have to contend with the uncertainties that inevitably surround many events and circumstances […]’ (IASC, Citation1989, par. 37). Thus, there is a link between the two aspects in that, first of all, accounting information should be neutral, i.e. free from bias, but, under uncertainty that permeates financial accounting activities, prudence should also be considered. While it needs to be ensured that ‘assets or income are not overstated and liabilities or expenses are not understated’, it is also noted that the ‘creation of hidden reserves’ as well as the ‘deliberate understatement of assets or income’ and the ‘deliberate overstatement of liabilities and expenses’ would conflict with neutrality (IASC, Citation1989, par. 37).

The new CF positions cautious prudence, which neither permits any over- nor understatements of assets, income, liabilities and expenses (CF2018.2.16), as part of neutrality. The IASB’s argument is that there is a ‘natural bias that management may have towards optimism’ (CF2018.BC2.39(a)) and prudence is intended to counter that bias through raising the awareness of preparers, auditors and regulators (CF2018.BC2.39(a)) but also to help the IASB develop standards that reduce the risk of management bias (CF2018.BC2.39(b)). This view of cautious prudence as a means to achieve neutrality seems to be largely in line with the CF1989 where the two were introduced as complementary rather than opposing aspects of reliability.

However, the approach in the CF2018 is at odds with the decision taken by IASB/FASB in 2010 when prudence was eliminated because it ‘would be inconsistent with neutrality’ (CF2018.BC2.34). In standard-setting and among constituents, prudence was sometimes interpreted as leading to asymmetric treatments and such asymmetries have also been widespread in individual standards regarding recognition, measurement and disclosure in IFRS (see Barker & McGeachin, Citation2015, for a comprehensive review; Wagenhofer, Citation2014, with regard to revenue recognition). Discarding this practice, the Boards eliminated the term prudence in the CF2010, a step that was in particular from an ex-post perspective controversial as it signaled that the IASB does not regard prudence as an important aspect to consider in its standard-setting. Among other things, this led to resistance by the European ParliamentFootnote15 and, for instance, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) stated its preference for explicitly including prudence as a consideration in the CF (EFRAG, Citation2013a, par. 38). The need to rethink the issue of prudence was also mentioned in a speech by the Chairman of the IASB, Hans Hoogervorst, in 2012:

You might very well ask what the heck was wrong with this definition of Prudence? My answer would be: absolutely nothing. The definition basically says that if you are in doubt about the value of an asset or a liability it is better to exercise caution. This is plain common sense which we all should try to apply in our daily life. (Hoogervorst, Citation2012, pp. 2–3)Footnote16

It seems that the IASB’s conceptual thinking with respect to prudence is more developed than it was during the prior IASB/FASB revision. Introducing the distinction between cautious and asymmetric prudence at least provides some clarity of the IASB’s views. However, it remains problematic how the CF deals with asymmetric prudence. The QCs are intended to operationalize the objective of financial reporting and thus should be considered in standard-setting. Thus, every major consideration to achieve decision useful information should ideally be included in this list of QCs and then be balanced by the Board in specific standard-setting decisions. On the one hand, the IASB explicitly rejects asymmetric prudence to form part of this list of QCs. On the other hand, it still acknowledges asymmetric prudence might sometimes be applied if, in the Board’s view, it leads to higher decision usefulness. In light of the role that QCs are supposed to play in standard-setting this approach seems questionable.

3.3. Reliability / A Tolerable Level of Measurement Uncertainty

In the CF2018, the IASB introduces a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty as a new subaspect of the fundamental QC ‘faithful representation’ in addition to completeness, neutrality and freedom from error (see for an overview). In CF2018.2.19, it is acknowledged that in cases of estimates ‘measurement uncertainty arises’. However, it is immediately stated that estimates are ‘an essential part of the preparation of financial information’ and do not restrict decision usefulness per se. It is argued that ‘[e]ven a high level of measurement uncertainty does not necessarily prevent such an estimate from providing useful information’ (CF2018.2.19). Thus, the introduction of a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty in CF2018.2.19 is rather reluctant and would, at a first glance, suggest a limited importance of this new subaspect. However, in later paragraphs in Chapter 2 that elaborate on the application of the fundamental QCs (i.e. relevance and faithful representation), the IASB notes that ‘the level of measurement uncertainty in making [an] estimate may be so high that it may be questionable whether the estimate would provide a sufficiently faithful representation of that phenomenon’ (CF2018.2.22). In such situations, this has to be balanced against the relevance of the information and a less relevant estimate that has a lower level of measurement uncertainty might be preferred (CF2018.2.22). Thus, the balancing of a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty and relevance is presented as the exemplar of a trade-off between QCs and is reminiscent of the trade-off notion that traditionally existed between relevance and reliability (CF2018.BC2.53; BC2.54).

The IASB argues that the description of faithful representation in the new CF is ‘substantially aligned’ (CF2018.BC2.31) with the description of reliability in the CF1989, in other words that the former concept is now fully captured in the QC ‘faithful representation’. However, this argument ignores one important aspect of the former definition of reliability that is not taken up in faithful representation: the expression ‘can be depended upon’ (IASC, Citation1989, par. 31). As the official motivation to replace reliability had been the different interpretations of the term, the IASB did not want to reintroduce ‘reliability’ (CF2018.BC2.30). Moreover, the Board identified two meanings of reliability (CF2018.BC2.29): First, the meaning of a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty (e.g. in the CF2010 and in several standards, e.g. IAS 38.21(a); IAS 37.23). Second, a QC of useful financial information, that was called reliability and is now called faithful representation. This distinction is interesting as it differs from prior statements of the IASB in the CF2010 where, without explicit reference to extant standards, it was argued that the two notions of reliability were, on the one hand, verifiability, and, on the other hand, faithful representation (CF2010.BC3.23, BC3.25). Indeed, one of the main reasons for multiple understandings of reliability in the CF1989 was that it included both verifiability and faithful representation as sub-aspects (Erb & Pelger, Citation2015, p. 25). Comparing these two distinctions made in 2010 and 2018, there seems to be a strong overlap between measurement uncertainty and verifiability. Verifiability is positioned in both CFs as an enhancing QC (CF2010.QC19; CF2018.2.30). While the IASB acknowledges that ‘measurement uncertainty makes information less verifiable’ (CF2018.BC2.48), the exact relation between these notions is not addressed in the CF2018.

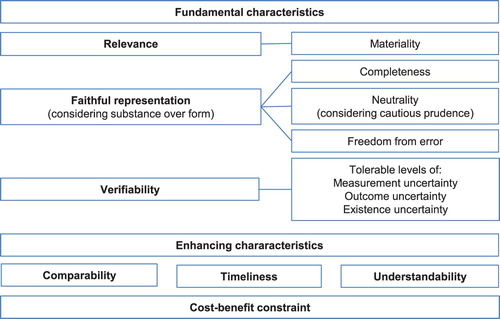

With respect to the positioning of measurement uncertainty, the IASB does not provide a convincing argument. First, it points to the CF2010 (CF2018.BC2.47) saying that measurement uncertainty negatively affects relevance but that it could still ‘be a faithful representation if the reporting entity has properly applied an appropriate process, properly described the estimate and explained any uncertainties that significantly affect the estimate’ (CF2010.QC16). This statement regards faithful representation as basically independent of concerns of measurement uncertainty. Second, it provides the argument that high levels of measurement uncertainty negatively affect ‘whether economic phenomena can be faithfully represented’ (CF.BC2.48(b)) which is different from the former view of independence of faithful representation and measurement uncertainty.Footnote18 If these statements are more than just ‘twisting words’ (Erb & Pelger, Citation2015, p. 13), neither relevance (as suggested in the 2015 ED) nor faithful representationFootnote19 seem to be the ideal choice for including measurement uncertainty. Therefore, the present paper suggests its introduction as a third (separate) fundamental QC. This would also resonate with the IASB’s statement that ‘an estimate might not provide useful information if the level of uncertainty in the estimate is too large’ (CF2018.BC2.47, emphasis added).

As a further step, it might be worth rethinking the term ‘measurement uncertainty’. While the relationship between measurement uncertainty and verifiability has not yet been fully explored by the IASB, the established term ‘verifiability’ that formed part of reliability in the former FASB CF (FASB, Citation1980, par. 81)Footnote20 would seem an obvious choice. Board members as well as constituents often interpreted reliability in the CF1989 to mean verifiability (Erb & Pelger, Citation2015, p. 25, 28). The trade-off between relevance and reliability in the former CFs basically boils down to a trade-off between relevance and verifiability. In the words of the IASB (CF2010.BC3.36): ‘many forward-looking estimates that are very important in providing relevant financial information […] cannot be directly verified.’

In the CF2018, the IASB distinguishes three types of uncertainty. In addition to measurement uncertainty, it also refers to existence uncertainty, i.e. whether an asset (right, CF2018.4.13) or a liability (obligation, CF2018.4.32) in the definition of the CF exist, and outcome uncertainty, i.e. uncertainty about the amount or timing of the future inflow or outflow of economic benefits (CF2018.6.61). The CF1989 with its emphasis on reliability entailing information that ‘can be depended upon’ (IASC, Citation1989, par. 31) had a more comprehensive perspective on dealing with uncertainties. For instance, it was stated: ‘Information may be […] so unreliable in nature or representation that its recognition may be potentially misleading’ (IASC, Citation1989, par. 32), alluding to what is now called existence and outcome uncertainty.Footnote21 Thus, all three types of uncertainty influence to what extent the information presented in financial reports ‘can be depended upon’, but the CF2018 singles out a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty as an attribute of faithful representation.Footnote22

Putting verifiability on the level of a fundamental QC would finally reestablish the former notion of reliability, including the extent to which the information provided ‘can be depended upon’.Footnote23 While measurement uncertainty might be regarded as its most important specification, verifiability as a more comprehensive term could improve the conceptual clarity in Chapter 2 of the CF. Therefore, in light of the history of CFs and the recent experiences from CF revisions this paper suggests to introduce verifiability as a third fundamental QC that includes considerations of tolerable levels of all three dimensions of uncertainty discussed in the CF. provides a summary of such an alternative setup of QCs.

4. The Impact of Stewardship, Measurement Uncertainty and Prudence in the CF2018

The link between Chapters 1 and 2 is that the QCs ‘identify the types of information that are likely to be most useful to [users] for making decisions’ (CF2018.2.1). However, Chapter 2 does not outline in what way the decision to elevate the role of stewardship influences the identification or balancing of QCs. Thus, no clear link is established between stewardship and the (re)introduction of a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty and prudence. This section studies the implications of the renewed emphasis on stewardship and the (re)introduction of a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty and prudence for the other parts of the CF. In other words, it explores whether the changes to the objective and QCs had any observable implications on Chapters 3–8 of the CF2018.

4.1. Financial Statements and the Reporting Entity

Chapter 3 of the CF2018 defines and explains the terms ‘financial statements’ and ‘reporting entity’. At the beginning of this chapter, the objective of financial reporting, as outlined in Chapter 1, is repeated (CF2018.3.2) to argue that information useful for valuation and stewardship assessments is provided by the statements of financial position and financial performance as well as other statements and notes (CF2018.3.3).Footnote24 Information disclosed in these other statements, among other things, comprise ‘information […] about the risks arising from […] recognized assets and liabilities’ (CF2018.3.3(c)(i)). The BC discusses that such information ‘is likely to be useful’ for both valuation and stewardship purposes (CF2018.BC3.8). There is no further discussion about how priorities might differ for these purposes as it regards the statements/notes and the elements incorporated therein.

CF2018.3.8 notes that financial statements follow the entity perspective as this is deemed ‘consistent with the objective’ (CF2018.BC3.10) of decision usefulness. Van Mourik (Citation2014) outlines that the entity theory is not consistent with the approaches taken by the IASB in defining financial position and performance in its CF. According to her analysis, the IASB’s CF is rather ‘based on a mixture of Proprietary Theory and Residual Equity Theory’ (Van Mourik, Citation2014, p. 231). Whittington (Citation2008a), p. 159, posits that, from a stewardship perspective, the current shareholders are the central users of financial statements. This view would better be reflected by proprietary theory than entity theory. However, in Chapter 3 of the CF2018 no such discussions are included, suggesting that the elevated role of stewardship did not have any material effects on the choice of entity theory as the basis for the financial statements and, more generally, the content of Chapter 3.Footnote25

4.2. Elements of Financial Statements

Chapter 4 provides definitions of the terms asset, liability, equity, income and expenses. These definitions largely follow the previous ones already developed in the CF1989.Footnote26 In line with the former IASB (and FASB) CFs, the IASB follows the asset-liability-approach (e.g. Brouwer et al., Citation2015; Dichev, Citation2008) in that it first defines assets and liabilities and then identifies income and expenses as changes in assets/liabilities. While the IASB notes that this approach does not favor information about the financial position over information about financial performance (CF2018.BC4.94(a)), it argues that assets and liabilities are a natural starting point as these ‘refer to real economic phenomena’ (CF2018.BC4.94(d)) and explicitly rejects matching of income and expenses as a relevant conceptual concern (CF2018.BC4.94(e)).Footnote27 This statement can be contrasted to several current standards that do include matching and do not follow the definitions of assets and liabilities (and recognition criteria) set out in the CF (see Barker & Teixeira, Citation2018; Brouwer et al., Citation2015; Wagenhofer, Citation2014).

For the case of revenue recognition, Wagenhofer (Citation2014) notes that a later recognition of revenues when the risk of the transaction has largely been eliminated might better serve stewardship purposes, while timelier recognition in the form of contract assets and liabilities might be superior for valuation purposes. However, it is not clear to what extent this might reflect a more general preference for the revenue-expense approach in contrast to the asset-liability-approach from a stewardship perspective. In Chapter 4, the IASB is silent on any such possible difference as no reference is made to stewardship in the text or the BC.Footnote28

Following the logic of the asset-liability-approach, the CF2018 continues with chapters on the recognition and measurement of assets and liabilities that are presented in the following subsections.

4.3. Recognition

Chapter 5 of the CF2018 does not specify any general recognition criteriaFootnote29 but instead provides guidance on factors that the IASB should consider when thinking about the introduction of such criteria in individual standards. The starting point is that ‘[a]n asset or liability is recognized only if recognition of that asset or liability […] provides users of financial statements with information that is useful’ (CF2018.5.7). Following the fundamental QCs from Chapter 2, useful information is said to be relevant information about the asset or liability that provides a faithful representation of the asset or liability (CF2018.5.7). Chapter 5 does not include any additional discussion of the objective of financial reporting. Thus, the added emphasis on stewardship does not seem to have any implications in the chapter on recognition.

Chapter 5 discusses in what way relevance and faithful representation could give rise to recognition criteria. With respect to relevance it is noted that uncertainty about the existence of an asset or a liability (CF2018.5.14) or a low probability of an inflow or outflow of economic benefits (CF2018.5.15-18) could restrict the recognition in specific standards. While these two factors are discussed as possibly limiting the relevance of information, it is not explained how these factors relate to relevance.Footnote30 With respect to faithful representation, the case of high levels of measurement uncertainty is outlined as a case where ‘it may be questionable whether the estimate would provide a sufficiently faithful representation’ (CF2018.5.20). Furthermore, ‘other factors’ are discussed that include effects of recognition on income, expenses and changes in equity, cases of accounting mismatches and presentation and disclosure issues (CF2018.5.25). Thus, measurement uncertainty features as an important consideration in the CF guidance on recognition criteria next to existence and outcome uncertainty. That the former is positioned as a part of faithful representation and the latter two as parts of relevance seems somewhat arbitrary. As outlined in Section 3.3, encompassing all three types of uncertainty in the characteristic of verifiability and putting it next to relevance and faithful representation might be conceptually superior.

In contrast to the CF2018's discussion of measurement uncertainty with respect to recognition criteria, a discussion is largely absent for the other sub-aspects of faithful representation, i.e. completeness, neutrality and freedom from error. However, the notion of asymmetric prudence is at least indirectly alluded to in CF2018.BC5.22. There, the IASB notes that some respondents would see measurement uncertainty as a more severe problem for assets compared to liabilities. However, on the basis of neutrality it is argued that such a general statement is not valid and asymmetric decisions depend ‘on the facts and circumstances and so can be determined only when developing Standards’ (CF2018.BC5.22) but not as a general guideline. While highlighting the absence of a general asymmetric approach to recognition, the notion of cautious prudence is not taken up in Chapter 5 and thus cannot be expected to influence future standard-setting in this area.

4.4. Measurement

Chapter 6 first introduces and then describes and contrasts different measurement bases that the IASB might select in its standards. These bases include historical cost (CF2018.6.4) and current value (comprising fair value, value in use/fulfilment value, and current cost, CF2018.6.11). Then, the chapter turns to delineate ‘factors to consider when selecting a measurement basis’. Similar to the discussion on recognition, Chapter 6 builds on the general idea that ‘[t]he information provided by a measurement basis must be useful to users of financial statements. To achieve this, the information must be relevant and it must faithfully represent what it purports to represent’ (CF2018.6.45).

Again, the notion of usefulness is not further elaborated on and thus the additional emphasis on stewardship in Chapter 1 does not have any direct influence on the content of Chapter 6. Instead, attention is given to the QCs. When discussing the QCs, the IASB first describes ‘characteristics of the asset or liability’ and the way the asset/liability contributes to future cash flows as considerations of relevance (CF2018.6.49). For faithful representation, it mentions the case of accounting mismatches (CF2018.6.58) and measurement uncertainty (CF2018.6.60). The latter is outlined as follows: ‘in some cases the level of measurement uncertainty is so high that information provided by a measurement basis might not provide a sufficiently faithful representation […]. In such cases, it is appropriate to consider selecting a different measurement basis that would also result in relevant information’ (CF2018.6.60). Chapter 6 also discusses the enhancing QCs, among them verifiability: ‘Verifiability is enhanced by using measurement bases that result in measures that can be independently corroborated either directly […] or indirectly’ (CF2018.6.68).

Thus, both measurement uncertainty and verifiability are discussed as factors to consider by the IASB in future standard-setting choices of measurement bases. However, the two are introduced independently in the main text, as the link between these factors is not explored, in spite of the IASB’s statement in the BC to Chapter 2 that ‘measurement uncertainty makes information less verifiable’ (CF2018.BC2.48). This points to the need to conceptually combine these criteria, as suggested in the alternative setup of QCs in Section 3.3.

Prudence is not mentioned in the main text of Chapter 6. Thus, one can conclude that cautious prudence does not reflect a major consideration of the IASB when choosing a measurement basis. This is notable since ‘judgments under conditions of uncertainty’ (CF2018.2.16) might be particularly pronounced in the context of measurement. While this raises doubts about the role that the concept of cautious prudence, as defined in the CF2018, can materially play in standard-setting, the IASB makes an explicit statement with regard to asymmetric prudence and measurement. In CF2018.BC6.45, which addresses the comment by some constituents that ‘applying prudence […] would imply that the tolerable level of measurement uncertainty would always be higher for liabilities than for assets’, the IASB rejects this view as it would manifest asymmetric prudence as a factor to consider when deciding on measurement bases of individual items.

4.5. Presentation and Disclosure

The section on presentation and disclosure first introduces three broad principles of effective communication (CF2018.7.2). These principles are briefly discussed and do not provide substantial guidance for the IASB to decide on such issues in future standard-setting. Most space in Chapter 7 is devoted to a discussion of classification, in particular the classification of income and expenses. This centers on the question in which cases income and expenses should be included in the statement of profit or loss or in other comprehensive income (OCI).

The IASB pronounces that the profit or loss is central for determining an entity’s financial performance (CF2018.7.16) and therefore, in general, all income and expenses should be included there (CF2018.7.17). However, ‘in exceptional circumstances’ the IASB may decide that presenting income and expenses resulting from changes in current value should be presented in OCI as this leads to more relevant information or provides a more faithful representation of performance for that period (CF2018.7.17). In contrast to Chapters 5 and 6, the IASB does not elaborate on factors to be considered by the IASB when making this decision. The BC informs us that this is a deliberate decision but does not provide any argument for it (CF2018.BC7.25). For instance, it is unclear how the notion of measurement uncertainty influences the IASB’s choice between P&L and OCI; whether, for example, high levels of measurement uncertainty in the estimate of current values would suggest a treatment of value changes in OCI rather than the P&L.

In the DP from 2013, the IASB included a broader discussion about factors that might be relevant in making such decisions and mentioned unrealized, non-recurring, non-operating items as well as measurement uncertainty, long term realization and items outside of management control (IASB, Citation2013, Table 8.1). However, the IASB rejected the view that any (combination) of these factors could help in making a distinction between P&L and OCI (IASB, Citation2013, par. 8.38). Instead, in the DP it suggested to focus on the question of whether the relevance of the P&L would be improved by presenting certain items in OCI (IASB, Citation2013, par. 8.81; similarly IASB, Citation2015, par. 7.24). The consideration of faithful representation to inform the distinction between P&L and OCI was only added in the CF2018. In the absence of any operationalization (and examples) of how to apply relevance and faithful representation to this area, however, as also noted by Van Mourik and Katsuo Asami (Citation2018) with regard to the 2015 ED, not much assistance is offered to the IASB for its future standard-setting.

Another aspect regarding OCI is whether income and expenses included therein should later, for example when selling/derecognizing the asset, be reclassified into P&L. According to CF2018.7.19, income and expenses included in OCI, in principle, should be reclassified into P&L in a later period (recycling) if this provides more relevant information or a more faithful representation of the entity’s performance. Specific factors to consider in the IASB’s assessment whether recycling leads to higher relevance or a more faithful representation are not outlined (CF2018.BC7.33).Footnote31

Stewardship is not discussed in chapter 7 although classifications into OCI (and recycling) might be regarded as more important for this purpose than for valuation purposes (Van Mourik & Katsuo Asami, Citation2018, p. 188) to isolate results of management performance (in the P&L) from other effects (in OCI). Cautious or asymmetric prudence are also not mentioned. Thus, an impact of the conceptual changes in the CF2018 on presentation and disclosure issues is not recognizable.

4.6. Concepts of Capital and Capital Maintenance

Chapter 8 briefly outlines concepts of capital and capital maintenance which were copied from the CF1989. No reference is made to either stewardship, prudence or measurement uncertainty in this chapter.

4.7. Summary

Overall, this section shows that the increased emphasis on stewardship does not materialize in the rationale provided by the IASB in the further chapters of its CF. Similarly, the introduction of cautious prudence is not taken up. However, a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty features prominently in the chapters on recognition and measurement as a factor to consider by the IASB and thus might bear the potential to influence future standard-setting debates in these areas. The classification decisions regarding OCI (and recycling) might also constitute an area to apply concerns about a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty which, however, currently is not made explicit in the underdeveloped Chapter 7 of the CF2018.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

In the more abstract parts of its new CF, the IASB has moved back to the times before 2010. Stewardship has gained prominence as part of the decision usefulness objective, but without being stated as a separate objective. This change addresses criticism that has focused on stewardship ‘as a matter of emphasis’ and on the IASB ignoring the term in the CF2010 (e.g. EFRAG, Citation2013b). The heightened importance given to stewardship, however, does not show substantial effects in the later chapters of the CF. This corroborates the statement by Van Mourik and Katsuo Asami (Citation2018, p. 171) that ‘this increased prominence [of stewardship] is in name only, as it has no impact on the actual financial accounting and reporting’. The lack of perceivable implications is in line with the long-standing debates on what might change if stewardship was accorded the status of a separate objective. An IASB Board member quoted in Pelger (Citation2016), p. 65, asked: ‘As a board member, if I place stewardship differently from valuation, how would I make a different decision in setting standards?’ While some conceptual attempts have been made to find examples where stewardship makes a difference (e.g. EFRAG, Citation2013b; Lennard, Citation2007; Wagenhofer, Citation2014), there have not yet been many answers to this question. As the IASB decided against positioning stewardship as a separate objective, the higher emphasis given to it mainly appeases constituents without materially affecting future standard-setting.

The reintroduction of (cautious) prudence and the explicit rejection of asymmetric prudence as part of the QCs attempts to clarify the IASB’s conceptual view on prudence. However, the former is not mentioned in any of the other chapters of the IASB’s CF2018. Thus, it remains unclear what the consideration of cautious prudence implies for a standard-setter beyond a signal to preparers, auditors and others that care should be employed in financial reporting matters under uncertainty. As elaborated by Georgiou (Citation2015) its incorporation in the CF2018 might mainly reflect a reaction to political pressures. While at a few places in the CF2018 asymmetric approaches are rejected on the basis of neutrality, the positioning of asymmetric prudence as a consideration outside the scope of the QCs gives it an unclear role for standard-setting. Overall, while more thought has been given to prudence in the IASB CF revision, this does still not provide a meaningful and consistent basis for standard-setting.

The most noteworthy change, from the perspective of its effects on other parts of the CF2018, is the introduction of a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty as a sub-aspect of faithful representation. This concept is supposed to act as a successor to the former notion of reliability and is included in the IASB’s further conceptual thoughts about recognition and measurement. More precisely, measurement uncertainty serves as a potential barrier when discussing recognition and measurement questions in specific standard-setting processes, an approach that could be extended to deliberations on the classification of income and expenses.

It would be too far-fetched to see the introduction of measurement uncertainty as a direct effect of the higher prominence that stewardship achieved in the CF2018. Indeed, no explicit link was established in the CF2018 or the BC. Nonetheless, it might be argued that all changes reflect an ‘alternative view’ (Whittington, Citation2008a) that acknowledges moral hazard concerns which require more emphasis on reliability and prudence (Bauer, O’Brien, & Saeed, Citation2014; Mora & Walker, Citation2015; Wagenhofer, Citation2014). For instance, Kuhner and Pelger (Citation2015) show in an analytical model that, in the face of managerial discretion, the relevance-reliability trade-off differs for valuation and stewardship purposes and that it is particularly important to deal with earnings management from a stewardship perspective. Along the same line, in the context of revenue recognition, Wagenhofer (Citation2014) summarizes empirical research showing that (asymmetric) prudence ‘has been found of particular value in stewardship settings’.

The steps taken by the IASB suggest a retreat from the ‘fair value view’ that dominated the CF2010 (Whittington, Citation2008a). While the reasons for this shift are manifold (e.g. see Whittington, Citation2016), it is made explicit in the IASB’s new CF: ‘The Board concluded that in different circumstances different measurement bases may provide information relevant to users of financial statements’ (CF2018.BC6.10). Such an acknowledgment resonates with the opinions of constituents (CF2018.BC6.7) and also with empirical research on users’ assessments of measurement bases (Gassen & Schwedler, Citation2010; Georgiou, Citation2018). In such a setting, where the standard-setter does not favor one particular measurement basis per se, the consideration of QCs becomes an important issue. Thus, the (re)introduction of reliability as well as the reestablishment of a trade-off between relevance and a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty can be linked to the more open stance towards measurement bases by the IASB.

From a conceptual view-point, however, the positioning of a tolerable level of measurement uncertainty in the CF2018 does not seem fully convincing. While the CF regards it as part of faithful representation, the ED from 2015 considered it as a sub-aspect of relevance. A solution, suggested in this paper, would be to state it as a third fundamental characteristic and to adopt the broader term ‘verifiability’ that would also encompass tolerable levels of existence and outcome uncertainty. All three fundamental QCs could then be systematically applied in the areas of recognition, measurement and presentation and disclosure. Clearly, though, such an approach would lead to a more fundamental (and more explicit) deviation between the IASB’s and the FASB’s CFs than the CF2018.

While the IASB points out that it will think about a revision of the CF from time to time, this is not likely to encompass the most fundamental parts on objectives and QCs in the near future. Instead, it can be expected that these chapters will at least have a comparable lifetime to that of the first IASC/IASB CF, which was more than 20 years. However, this should not discourage academics to engage with the objectives and QCs. Recent research has started to use experiments to explore these topics (Anderson, Brown, Hodder, & Hopkins, Citation2015; Cascino et al., Citation2017) and has also begun to employ qualitative studies to address the question of what reliability means in the preparation (and audit) of accounts (Barker & Schulte, Citation2017; Huikku, Mouritsen, & Silvola, Citation2017). It is to be hoped that the IASB – when it will start yet another CF revision at some point – can build on more (empirical) academic insights that are able to speak to the standard-setters’ conceptual challenges.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, it has solely used publicly observable material and existing literature as the basis for stating its arguments. In particular, this means that it follows the official rationales provided by the IASB in the CF and the BC. This does not necessarily fully reflect the deliberations on the further chapters of the CF during the IASB’s meetings and also does not account for possibly divergent views (and rationales) of the individual IASB Board members on the topics discussed. Second, it is not clear to what extent the IASB will actually use Chapters 3–8 of the CF2018 in its future standard-setting activities and, in particular, how closely it will follow them. The IASB is not formally restricted by the content of the CF and explicitly acknowledges that it might sometimes deviate from it (CF2018.SP1.3). Thus, one might argue that, for instance, stewardship and cautious prudence will play important roles in future standard-setting although they are not taken up in the other chapters of the CF. To what extent this might happen, however, is an empirical question beyond the scope of this paper.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Carsten Erb, participants at the EUFIN Workshop in Stockholm (2018) and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Christoph Pelger http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7140-5262

Notes

1 In the following, references to IASB (Citation2018) will be abbreviated as CF2018 with the respective paragraph. CF2018.BC refers to the Basis for Conclusions of the new CF.

2 The CF is special in that it is the only document issued by the IASB primarily intended for its own use and not the use by other parties. However, preparers sometimes have to refer to the CF, in particular in cases of regulatory gaps (IAS 8) and the true-and-fair-override (IAS 1.15). The IASB published amendments to these standards that come into effect as of 2020. Then, preparers, when using IAS 8 and IAS 1, will have to revert to the CF2018.

3 References to IASB (Citation2010) are abbreviated as CF2010 in the following. Again, BC refers to the Basis for Conclusions. Correspondingly, the FASB published Statement of Financial Accounting Concept (SFAC) No. 8 (FASB, Citation2010) which replaced the prior Statements No. 1 (FASB, Citation1978) and No. 2 (FASB, Citation1980).

4 The ‘Conceptual framework for the preparation and presentation of financial statements’ (IASC, Citation1989) had first been developed by the IASC, the predecessor of the IASB, in 1989. For the history of its creation see Camfferman and Zeff (Citation2007, pp. 254–264). When the IASB replaced the IASC in 2001, it adopted the CF without any changes. References to IASC (Citation1989) are abbreviated as CF1989 in the following.

5 The CF2010 included four chapters: Chapter 1 on the objective of financial reporting, Chapter 2 on the reporting entity (which remained empty), Chapter 3 on qualitative characteristics and Chapter 4 on ‘the remaining text’ which was a copy of definitions, recognition, measurement and capital maintenance concepts from the CF1989.

6 In contrast to the IASB, the FASB has not yet published an updated CF or parts thereof. For the project status see http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Page/TechnicalAgendaPage&cid=1175805470156#tab_1175805471232

7 A further, although arguably minor, change is that the CF2018 explicitly takes up substance over form in its description of faithful representation (CF2018.2.12). In the CF2010, it was said to be automatically included in faithful representation and mentioning it as a separate component ‘would be redundant’ (CF2010.BC3.26).

8 However, it was somewhat more in line with the former treatment of stewardship in the FASB’s CF (FASB, Citation1978), where stewardship had been included (FASB, Citation1978, par. 50–53) but the relation to the primary objective of decision usefulness was unclear.

9 There were two Alternative Views in the DP (IASB, Citation2006). First, Tweedie and Whittington objected to the proposed relegation of stewardship in the section on the objective of financial reporting (AV1.1-1.7). Second, Whittington issued an Alternative View regarding the (sub-)concept of verifiability that, in his view, should include an explicit reference to a factual basis (reliable evidence) (AV2.1-2.2).

10 Chapter 2 in the CF2010 was reserved for the results of this phase but because of the project stop remained empty until 2018. For the other phases, no consultation document had been published until 2010. Only for phase B that covered recognition and measurement first deliberations had been made in Board meetings.

11 In the words of the IASB, changes were made to Chapters 1 and 2 in the CF2018 because ‘the clarity achieved by [these] improvements […] outweighs the disadvantage of divergence in those respects from the FASB’s version’ (CF2018.BC1.3).

12 This paper follows the IASB’s view which is in line with the understanding of stewardship/accountability in the agency literature (e.g., Gjesdal, Citation1981). See Kuhner and Pelger (Citation2015), pp. 382–385, for a discussion of different views on stewardship and a review of academic literature.

13 CF2018.1.4 elaborates that for the assessments about future cash flows and management’s stewardship information are needed about: (a) the economic resources of the entity, claims against the entity and changes in those resources and claims; (b) how efficiently and effectively the entity’s management and governing board have discharged their responsibilities to use the entity’s economic resources. However, it is not explained how the two assessments relate to the two types of information.

14 It is further argued by the IASB that introducing another objective ‘could be confusing’ (CF2018.BC1.35(b)) without specifying for whom this might be the case and how stewardship as a separate objective might change or confuse the IASB’s thinking.

16 Georgiou (Citation2015) provides a deeper analysis of the political struggles surrounding the re-introduction of prudence into the IASB’s CF.

17 However, the CF2018 does not discuss in more detail how relevance and faithful representation relate to asymmetric prudence and why, in certain constellations, these might require asymmetric treatments.

18 In the DP published by the IASB/FASB in 2006, the Boards suggested to include verifiability as an aspect of faithful representation. However, the negative reactions in the comment letters led the IASB/FASB to put verifiability to the enhancing characteristics in the ED of 2008 (and the CF2010). Notably, the former FASB CF discussed a possible trade-off between these two sub-aspects of reliability (FASB, Citation1980, par. 89).

19 In a presentation of the CF2018 by an IASB staff member at the Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association in May 2018, she mentioned that faithful representation was ‘difficult to grasp’ and that ‘there are still questions of how to use it’. These problems were already visible during the joint IASB/FASB project. See Erb and Pelger (Citation2015), pp. 26–34.

20 Verfiability was also identified as a subaspect of reliability (next to neutrality and representational faithfulness) in the DP to the CF of the Accounting Standards Board of Japan (ASBJ). See Van Mourik & Katsuo, Citation2015, p. 203.

21 An example is provided in IASC (Citation1989), par. 32, as the validity and amount of a claim for damages under a legal action might be disputed and thus it may be inappropriate to recognize the full amount of the claim in the balance sheet. This example reflects a case of existence uncertainty (existence of a right/obligation).

22 Interestingly, existence and outcome uncertainty, in the IASB’s discussion on recognition in chapter 5 of the CF, are positioned as considerations of assessing the relevance of financial information (CF2018.5.14-5.17).

23 On the basis of IASC (Citation1989) an alternative term for verifiability could be dependability.

24 The BC discusses the link between the objective of financial statements provided in CF2018.3.2 and IAS 1. This includes two references in passing to stewardship.

25 There is no reference to prudence or measurement uncertainty in Chapter 3.

26 A change is that the term ‘expected inflow/outflow’ in the definitions of assets and liabilities was replaced by the ‘potential to produce economic benefits’ to avoid it being linked to probability considerations (CF2018.BC4.9, BC4.11).

27 Dichev (Citation2008, Citation2017) suggests that an ‘income model’ along the lines of matching would be superior to the ‘balance sheet approach’ in current CFs. For a contrary view see Miller and Bahnson (Citation2010). Similar to Dichev (Citation2017), Barker and Teixeira (Citation2018) argue for a clearer focus on accruals and identify the lack of direct measurement approaches of income and expenses as a gap in the CF. In contrast to the IASB, the ASBJ CF follows a revenue-expense approach for income determination (see Van Mourik & Katsuo, Citation2015).

28 With regard to the QCs, prudence is not mentioned, while there are two references to measurement uncertainty in the BC to Chapter 4 when discussing why the CF2018 does not include the term ‘contingent liabilities’ (CF2018.BC4.71, BC4.72). However, these references do not materially influence the definitions and explanations provided in Chapter 4.

29 The CF2010 (identical to the CF1989) included two recognition criteria: probability of the inflow or outflow of future economic benefits and reliable measurement (CF2010.4.38).

30 Note that this discussion is also not part of Chapter 2, i.e., existence uncertainty and low probability of flows of economic benefits are not mentioned in Chapter 2 in the context of relevance.

31 Van Mourik and Katsuo Asami (Citation2018), p. 188, posit that recycling is necessary to preserve the consistency between financial position and financial performance and is therefore not (primarily) an issue of relevance and/or faithful representation.

References

- Anderson, S. B., Brown, J. L., Hodder, L., & Hopkins, P. E. (2015). The effect of alternative accounting measurement bases on investors’ assessments of managers’ stewardship. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 46, 100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2015.03.007

- Barker, R. (2015). Conservatism, prudence and the IASB’s conceptual framework. Accounting and Business Research, 45, 514–538. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2015.1031983

- Barker, R., Lennard, A., Nobes, C., Trombetta, M., & Walton, P. (2014). Response of the EAA financial reporting standards committee to the IASB discussion paper a review of the conceptual framework for financial reporting. Accounting in Europe, 11, 149–184. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2014.940356

- Barker, R., & McGeachin, A. (2015). An analysis of concepts and evidence on the question of whether IFRS should be conservative. Abacus, 51, 169–207. doi: 10.1111/abac.12049

- Barker, R., & Schulte, S. (2017). Representing the market perspective: Fair value measurement for non-financial assets. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 56, 55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2014.12.004

- Barker, R., & Teixeira, A. (2018). Gaps in the IFRS conceptual framework. Accounting in Europe, 15, 153–166. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2018.1476771

- Barth, M. E. (2014). Measurement in financial reporting: The need for concepts. Accounting Horizons, 28, 331–352. doi: 10.2308/acch-50689

- Bauer, A. M., O’Brien, P. C., & Saeed, U. (2014). Reliability makes accounting relevant: A comment on the IASB conceptual framework project. Accounting in Europe, 11, 211–217. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2014.967789

- Brouwer, A., Hoogendorn, M., & Naarding, E. (2015). Will the changes proposed to the conceptual framework’s definitions and recognition criteria provide a better basis for IASB standard setting? Accounting and Business Research, 45, 547–571. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2015.1048769

- Camfferman, K., & Zeff, S. A. (2007). Financial reporting and global capital markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Camfferman, K., & Zeff, S. A. (2015). Aiming for global accounting standards: The international accounting standards board, 2001-2011. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cascino, S., Clatworthy, M., Osma, B. G., Gassen, J., Imam, S., & Jeanjean, T. (2017). The usefulness of financial accounting information: Evidence from the field. Working Paper, London School of Economics et al.

- Dennis, I. (2018). What is a conceptual framework for financial reporting? Accounting in Europe, 15, 374–401. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2018.1496269

- Dichev, I. D. (2008). On the balance sheet-based model of financial reporting. Accounting Horizons, 22, 453–470. doi: 10.2308/acch.2008.22.4.453

- Dichev, I. D. (2017). On the conceptual foundations of financial reporting. Accounting and Business Research, 47, 617–632. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2017.1299620

- Erb, C., & Pelger, C. (2015). “Twisting words”? A study of the construction and reconstruction of reliability in financial reporting standard-setting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 40, 13–40. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2014.11.001

- European Financial Reporting Advisory Group. (2013a). Getting a better framework: Prudence bulletin. Retrieved from https://www.efrag.org/(X(1)S(xcfs5mqtybcdgpp0a4bwzq1r))/Assets/Download?assetUrl=2Fsites2Fwebpublishing2FProject20Documents2F2832FBulletin%20Prudence.pdf

- European Financial Reporting Advisory Group. (2013b). Getting a better framework: Accountability and the objective of financial reporting bulletin. Retrieved from https://www.efrag.org/Assets/Download?assetUrl=2Fsites2Fwebpublishing2FSiteAssets2FBulletin2520Getting2520a2520Better2520Framework2520-2520Accountability2520and2520the2520Objective2520of2520Financial2520Reporting.pdf

- Financial Accounting Standards Board. (1978). Statement of financial accounting concepts no. 1 (SFAC 1): Objectives of financial reporting by business enterprises. Norwalk: FASB.

- Financial Accounting Standards Board. (1980). Statement of financial accounting concepts no. 2 (SFAC 2): Qualitative characteristics of accounting information. Norwalk: FASB.

- Financial Accounting Standards Board. (2010). Statement of financial accounting concepts no. 8 (SFAC 8): Conceptual framework for financial reporting. Norwalk: FASB.

- Gassen, J., & Schwedler, K. (2010). The decision usefulness of financial accounting measurement concepts: Evidence from an online survey of professional investors and their advisors. European Accounting Review, 19, 495–509. doi: 10.1080/09638180.2010.496548

- Georgiou, O. (2015). The removal and reinstatement of prudence in accounting: How politics of acceptance defeats financialisation. Working Paper. Manchester: University of Manchester.

- Georgiou, O. (2018). The worth of fair value accounting: Dissonance between users and standard setters. Contemporary Accounting Research, 35, 1297–1331. doi: 10.1111/1911-3846.12342

- Gjesdal, F. (1981). Accounting for stewardship. Journal of Accounting Research, 19, 208–231. doi: 10.2307/2490970

- Hoogervorst, H. (2012, September). The concept of prudence: Dead or alive? FEE Conference on Corporate Reporting of the Future, Brussels, Belgium. Retrieved from http://archive.ifrs.org/Alerts/PressRelease/Documents/2012/Concept%20of%20Prudence%20speech.pdf

- Huikku, J., Mouritsen, J., & Silvola, H. (2017). Relative reliability and the recognisable firm: Calculating goodwill impairment value. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 56, 68–83. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2016.03.005

- International Accounting Standards Board. (2006). Discussion Paper: Preliminary views on an improved conceptual framework for financial reporting. Retrieved from http://archive.ifrs.org/Current-Projects/IASB-Projects/Conceptual-Framework/DPJul06/Documents/DP_ConceptualFramework.pdf

- International Accounting Standards Board. (2008). Exposure Draft of an improved conceptual framework for financial reporting. Retrieved from http://archive.ifrs.org/Current-Projects/IASB-Projects/Conceptual-Framework/EDMay08/Documents/conceptual_framework_exposure_draft.pdf

- International Accounting Standards Board. (2010). Conceptual framework for financial reporting. London: IASB.

- International Accounting Standards Board. (2013). Discussion Paper DP/2013/1: A review of the conceptual framework for financial reporting. Retrieved from http://www.ifrs.org/-/media/project/conceptual-framework/discussion-paper/published-documents/dp-conceptual-framework.pdf

- International Accounting Standards Board. (2015). Exposure Draft ED/2015/3: Conceptual framework for financial reporting. Retrieved from http://www.ifrs.org/-/media/project/conceptual-framework/exposure-draft/published-documents/ed-conceptual-framework.pdf

- International Accounting Standards Board. (2018). Conceptual framework for financial reporting. London: IASB.

- International Accounting Standards Committee. (1989). Framework for the preparation and presentation of financial statements. London: IASC.

- Johnson, L. T. (2004). Understanding the conceptual framework. Retrieved from http://www.fasb.org/cs/BlobServer?blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs&blobkey=id&blobwhere=1175818770601&blobheader=application%2Fpdf

- Kuhner, C., & Pelger, C. (2015). On the relationship of stewardship and valuation – an analytical viewpoint. Abacus, 51, 379–411. doi: 10.1111/abac.12053

- Lennard, A. (2007). Stewardship and the objectives of financial statements: A comment on IASB´s preliminary views on an improved conceptual framework for financial reporting: The objective of financial reporting and qualitative characteristics of decision-useful financial reporting information. Accounting in Europe, 4, 51–66. doi: 10.1080/17449480701308774

- Mattessich, R. V. (1987). Prehistoric accounting and the problem of representation: On recent archaeological evidence of the Middle-East from 8000 B.C. To 3000 B.C. Accounting Historians Journal, 14, 71–91. doi: 10.2308/0148-4184.14.2.71

- Miller, P. B. W., & Bahnson, P. R. (2010). Continuing the normative dialog: Illuminating the asset/liability theory. Accounting Horizons, 24, 419–440. doi: 10.2308/acch.2010.24.3.419

- Mora, A., & Walker, M. (2015). The implications of research on accounting conservatism for accounting standard-setting. Accounting and Business Research, 45, 620–650. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2015.1048770

- Nobes, C. W., & Stadler, C. (2015). The qualitative characteristics of financial information and managers’ accounting decisions: Evidence from IFRS policy changes. Accounting and Business Research, 45, 572–601. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2015.1044495

- O’Brien, P. C. (2009). Changing the concepts to justify the standards. Accounting Perspectives, 8, 263–275. doi: 10.1506/ap.8.4.1

- O’Connell, V. (2007). Reflections on stewardship reporting. Accounting Horizons, 21, 215–227. doi: 10.2308/acch.2007.21.2.215

- Paul, J. M. (1992). On the efficiency of stock-based compensation. The Review of Financial Studies, 5(3), 471–502. doi: 10.1093/rfs/5.3.471

- Pelger, C. (2016). Practices of standard-setting - An analysis of the IASB/FASB’s process of identifying the objective of financial reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 50, 51–73. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2015.10.001

- Pelger, C., & Spieß, N. (2017). On the IASB’s construction of legitimacy – the case of the agenda consultation project. Accounting and Business Research, 47, 64–90. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2016.1198684

- Power, M. (2010). Fair value accounting, financial economics and the transformation of reliability. Accounting and Business Research, 40, 197–210. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2010.9663394

- Soll, J. (2014). The reckoning. London: Penguin.

- Van Mourik, C. (2014). The equity theories and the IASB conceptual framework. Accounting in Europe, 11, 219–233. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2014.949278

- Van Mourik, C., & Katsuo, Y. (2015). The IASB and ASBJ conceptual frameworks: Same objective, different financial performance concepts. Accounting Horizons, 29, 199–216. doi: 10.2308/acch-50902

- Van Mourik, C., & Katsuo Asami, Y. (2018). Articulation, profit or loss and OCI in the IASB conceptual framework: Different shades of clean (or dirty) surplus. Accounting in Europe, 15, 167–192. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2018.1448936

- Wagenhofer, A. (2014). The role of revenue recognition in performance reporting. Accounting and Business Research, 44, 349–379. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2014.897867

- Walton, P. (2018). Discussion of Barker and Teixeira ([2018]. Gaps in the IFRS conceptual framework. Accounting in Europe, 15) and Van Mourik and Katsuo ([2018]. profit or loss in the IASB conceptual framework. Accounting in Europe, 15). Accounting in Europe, 15, 193–199. doi: 10.1080/17449480.2018.1437457

- Whittington, G. (2008a). Fair value and the IASB/FASB conceptual framework project: An alternative view. Abacus, 44, 139–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6281.2008.00255.x

- Whittington, G. (2008b). Harmonisation or discord? The critical role of the IASB conceptual framework review. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 27, 495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2008.09.006

- Whittington, G. (2016). A critical look at the IASB. In J. Haslam, & P. Sikka (Eds.), Pioneers of critical accounting (pp. 179–200). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Williamson, J. E., & Lipman, F. J. (1991). Tracing the American concept of stewardship to English antecedents. The British Accounting Review, 23, 355–368. doi: 10.1016/0890-8389(91)90068-D

- Young, J. J. (2006). Making up users. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31, 579–600. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2005.12.005

- Zeff, S. A. (2013). The objectives of financial reporting: A historical survey and analysis. Accounting and Business Research, 43, 262–327. doi: 10.1080/00014788.2013.782237