Abstract

Background and purpose — Studies of fracture healing have mainly dealt with shaft fractures, both experimentally and clinically. In contrast, most patients have metaphyseal fractures. There is an increasing awareness that metaphyseal fractures heal partly through mechanisms specific to cancellous bone. Several new models for the study of cancellous bone healing have recently been presented. This review summarizes our current knowledge of cancellous fracture healing.

Methods — We performed a review of the literature after doing a systematic literature search.

Results — Cancellous bone appears to heal mainly via direct, membranous bone formation that occurs freely in the marrow, probably mostly arising from local stem cells. This mechanism appears to be specific for cancellous bone, and could be named inter-trabecular bone formation. This kind of bone formation is spatially restricted and does not extend more than a few mm outside the injured region. Usually no cartilage is seen, although external callus and cartilage formation can be induced in metaphyseal fractures by mechanical instability. Inter-trabecular bone formation seems to be less sensitive to anti-inflammatory treatment than shaft fractures.

Interpretation — The unique characteristics of inter-trabecular bone formation in metaphyseal fractures can lead to differences from shaft healing regarding the effects of age, loading, or drug treatment. This casts doubt on generalizations about fracture healing based solely on shaft fracture models.

Injury to cancellous bone is common. It is the predominant injury in, for example, vertebral compression, distal radial fractures, and tibial condyle fractures. By their nature, however, fractures of the cortical bone of the shaft are more readily studied in animal models. Most of our understanding of fracture healing is therefore skewed towards cortical healing. This narrative review focuses on the biology of cancellous bone healing.

Search method

The main body of 48 references in this review was previously known to us. In addition, a systematic literature search was performed in PubMed using the terms “Fracture healing [Mesh] AND (cancellous [Title/abstract] OR metaphys* [Title/abstract] OR intramembranous [Title/abstract]”. This resulted in 686 hits. Based on the titles, 99 abstracts were read, and in the end 14 of these articles were considered relevant and added to the references. We noted that only a quarter of the articles previously known to us were also found through this keyword search. It appears that the terms metaphysis, metaphyseal, intramembranous, and cancellous have seldom been viewed as being sufficiently important to occur in the title or abstract of the papers that we were already aware of: information on cancellous fracture healing has been hidden in articles focusing on other subjects.

Intramembranous ossification is a problematic concept; there have been many studies of shaft healing that have also looked at membranous bone formation in shaft healing. There, membranous bone formation mainly derives from the periosteum distal and proximal to the fracture. For reasons that will be explained, we do not believe that periosteal membranous bone formation following shaft fracture is identical to the inter-trabecular membranous ossification seen in a metaphyseal fracture. This review therefore focuses on inter-trabecular ossification. It consists in part of material taken from a thesis (Sandberg Citation2016).

Inter-trabecular bone formation is fast and spatially limited

Cancellous bone heals by membranous bone formation. It can be a fast process: in rodents a drill hole in cancellous bone can be filled with new bone tissue in less than a week. If a screw is inserted in the hole, its fixation is improved severalfold in a similarly short time (Sandberg and Aspenberg Citation2015b). In contrast, endochondral healing of shaft fractures in similar species can take about 3 times longer to reach comparable mechanical and radiological healing.

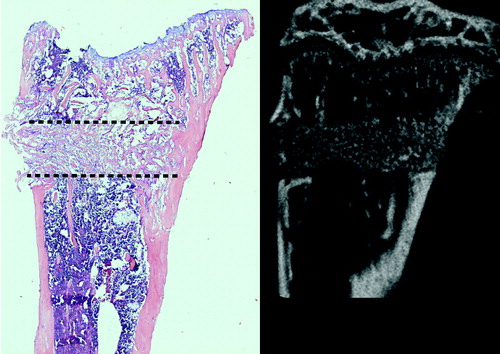

Bone formation after injury in cancellous bone is usually strictly localized to the injured region and appears not to spread away from it (). The filling of a defect in cancellous bone of a few millimeters width can therefore be slow or incomplete. This is quite different from shaft fracture healing, which can fill up considerable gaps. Already in the 1950s, John Charnley showed that human knee arthrodeses could heal in as little as 4 weeks if the cancellous resection surfaces fitted perfectly together, but not at all if there was a small gap. The cancellous bone formation response to trauma rarely extended more than 2 mm from the traumatized area () (Charnley and Baker Citation1952).

Figure 1. Photograph of a micro-dissected biopsy taken 4 weeks after knee arthrodesis, comprising the junction between the femur and tibia. Note the spatially limited bone formation. From Charnley and Baker (Citation1952) with permission.

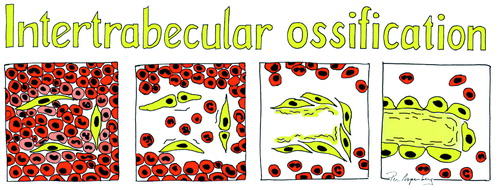

One reason for the fast response in inter-trabecular bone healing seems to be that osteoid forms simultaneously throughout the entire traumatized tissue volume (Sevitt Citation1971, Diamond et al. Citation2007, Aspenberg and Sandberg Citation2013, Chen et al. Citation2015), rather than mostly on the surfaces of old trabeculae—as previously thought. This appears very different from diaphyseal fracture healing as we know it from the textbooks. Stromal cells residing in the marrow apparently become activated to form bone freely in the marrow. In contrast to this, a recent paper reported little cell proliferation in a metaphyseal healing model in mice and the authors drew the conclusion that stem cell proliferation is probably not directly involved in the formation of new bone tissue in this model (Han et al. Citation2015). However, the only time point analyzed was day 7 after fracture. At this time point, most new bone formation has already occurred (Sandberg and Aspenberg Citation2015a).

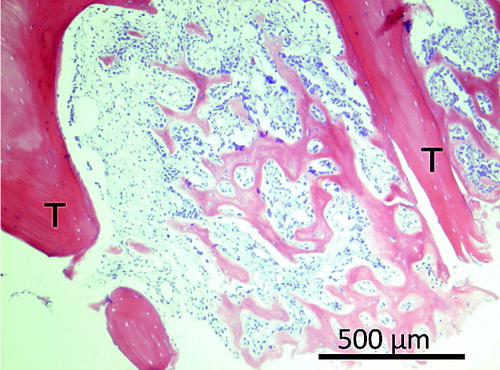

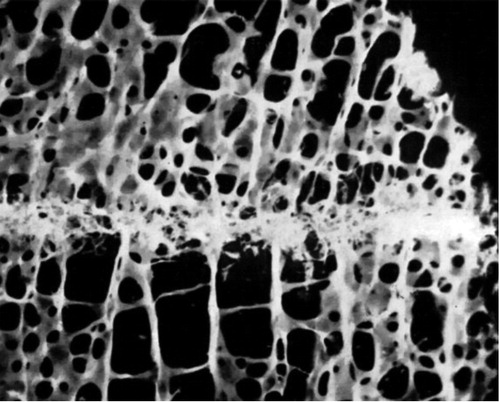

The inter-trabecular healing process after trauma starts with a hematoma, which is followed by inflammation (Kon et al. Citation2001). Inflammation is followed by mesenchymal cell condensations forming osteoid, which becomes woven bone (). This is then remodeled into lamellar bone (Charnley and Baker Citation1952, Chen et al. Citation2015, Han et al. Citation2015). In small animals, about 7 days is sufficient for mineralized woven bone to be clearly visible by microCT and histology () (Sandberg and Aspenberg Citation2015a). In human distal radius fractures, osteoid is visible from as early as 2 weeks after fracture, as seen by hematoxylin and eosin histology () (Aspenberg and Sandberg Citation2013).

Figure 2. A drawing of the main bone-forming process in inter-trabecular bone formation; condensations of mesenchymal cells forming osteoid, which becomes woven bone.

Endosteal cells seem prone to direct membranous formation

Mechanically stable cancellous fractures heal mainly without cartilage or an external callus (Han et al. Citation2012, Citation2015). There appears to be a predisposition of cells in the marrow to respond to trauma with membranous bone formation, while cells in the periosteum are more inclined to follow the endochondral route (Rabie et al. Citation1996, Gerstenfeld et al. Citation2001, Colnot Citation2009). This was nicely shown in a mouse experiment where cortical autografts were inserted in a fracture. When the periosteal side of the graft pointed outwards from the fracture, it developed endochondral bone formation. When flipped so that the periosteal side faced inwards, it still formed endochondral bone, now in the marrow. Conversely, the endosteal side mainly produced woven bone regardless of position (Colnot Citation2009). Instability, or rather micromotion, will also induce cartilage formation. This has been shown to be as true for cancellous bone healing as for cortical healing (Jarry and Uhthoff Citation1971, Schatzker et al. Citation1989, Claes et al. Citation2009, Citation2011). Instability of a metaphyseal fracture can also lead to an external callus (Uhthoff and Rahn Citation1981), probably mainly derived from the periosteum. However, cancellous fractures in patients are generally stable in the sense that repeated cyclic deformation of a considerable magnitude is unlikely to occur. Still, cyclic deformation appears to be beneficial for optimal bone formation in traumatized cancellous bone, in both humans and animals (Claes et al. Citation2011, Vicenti et al. Citation2014, Lutz et al. Citation2015).

One difference between cancellous and cortical healing might be stem cell availability

The available literature on shaft fracture healing is inconclusive regarding the relative contribution of cells from marrow, endosteum, periosteum, surrounding tissues, and circulation. This is the subject of an ongoing debate that has lasted 200 years (Gulliver Citation1835, Cooper Citation1845, Dupuytren and Clark Citation1847). It seems that while the periosteal contribution to healing is of major importance in shaft healing, other sources can compensate if the periosteum is compromised (Monfoulet et al. Citation2010).

Inter-trabecular bone formation is probably less dependent on periosteum, circulation, or other tissues, as compared to bone formation at other sites—although there are very few data (Schindeler et al. Citation2009). The metaphyseal marrow is known to have higher numbers of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) than the shaft, and these cells are also more committed to an osteogenic fate (Siclari et al. Citation2013). In a metaphyseal drill hole, a cancellous autograft produced more bone formation than a bone marrow concentrate enriched to a 3.5 higher MSC content and mixed with phosphate granules. Other differences aside, this could indicate that numbers of MSCs are unlikely to be a rate limiting factor in the regeneration of a metaphyseal drill hole (Jungbluth et al. Citation2013).

Some studies have found that trabeculae in the vicinity of a cancellous fracture will increase in thickness (Draenert and Draenert Citation1979, Obrant Citation1984, Bogoch et al. Citation1993b). In 1 study, a 5-fold increase in bone formation was found, and also a 5-fold increase in resorption, giving no net increase in bone (Bogoch et al. Citation1993a). It appears that the coupling between resorption and formation is still functional in the vicinity of the fracture, although not in the fracture itself: in cancellous bone healing, a single look in the microscope shows how bone formation predominates completely, indicating that it is uncoupled from resorption ( and ).

Regeneration after cancellous bone injury leads to systemic effects

When bone marrow regenerates after trauma, it leads to a systemic increase in the rate of bone formation—up to a quadrupling in other cancellous bone in the body (Einhorn et al. Citation1990). Serum from fracture patients has been shown to upregulate cell proliferation in vitro (Kaspar et al. Citation2003). Interestingly, the systemic response is lost if the traumatized volume is filled up with a replacement material, demonstrating that the regenerating tissue—rather than the trauma itself—lies behind the systemic effect (Gazit et al. Citation1990). Our group has recently seen that local metaphyseal trauma in 1 bone changes the composition of the immune cell population in metaphyseal marrow of other, distant bones (manuscript submitted). Thus, a part of the systemic effect may be orchestrated via the immune system.

Inflammation seems to play different roles in cancellous and cortical healing

A fracture, and the healing thereof, will cause reactions in the immune cell population. Traumatic injury will induce responses affecting up to 80% of the transcriptome in leukocytes (Xiao et al. Citation2011), and differences in the expression of some immune cell markers have been shown to correlate with recovery outcome after hip replacement surgery (Gaudilliere et al. Citation2014).

Inflammation plays a crucial role in shaft healing, but it appears to be less important in cancellous fractures. There is evidence for a direct link between dysfunctional inflammatory signaling in chondrocytes and unsatisfactory endochondral bone formation (Tu et al. Citation2014). In contrast, membranous healing in a metaphyseal drill hole model was found to be unaffected by the disruption of intracellular osteoblast glucocorticoid signaling (Weber et al. Citation2010).

Inflammation does occur after trauma in cancellous bone—but in comparison to cortical fractures, it may have another role. Anti-inflammatory drugs such as NSAIDs (indomethacin) and glucocorticoids (dexamethasone) have been shown to have little or no effect on metaphyseal healing, while greatly impeding diaphyseal healing (Meunier and Aspenberg Citation2006, Sandberg and Aspenberg Citation2015a and b). Reduced inflammatory signaling leads to delayed membranous bone formation following marrow ablation in mice. Mice that received a shaft fracture also had delayed healing in association with reduced inflammation. In the shaft fracture model, however, mRNA levels of osteocalcin and collagen 1a1 were increased from day 10, while this was not so in the membranous marrow ablation model (Gerstenfeld et al. Citation2001). The authors concluded that cortical and cancellous bone have different healing biology. NSAID effects are thought to be mediated by blocking the COX-2 pathway. In a model using titanium particles to induce periosteal membranous bone formation, this was reduced by 80% in COX-2 knockout mice (Zhang et al. Citation2002). A possible explanation for the difference between this model and metaphyseal drill holes might be that the role of COX-2 is different in periosteal bone formation and inter-trabecular bone formation.

We suggest that the apparent difference in the effect of inflammation in cancellous and cortical healing may be linked to the differences in the availability of MSCs within the hematoma between the shaft and the metaphysis. Inflammation is important for cell recruitment (Glass et al. Citation2011). Recruitment from distant sources might be crucial in cortical fractures but less so in the cancellous fractures of the metaphysis. Furthermore, endochondral and membranous bone formation obviously follow different biological pathways, which makes it possible that the role of inflammation in these could also be different.

The role of macrophages in fracture healing is well studied, although the results have been somewhat contradictory. Interestingly, macrophage depletion leads to increased membranous bone formation in the periosteum (Schlundt et al. Citation2015) and reduced membranous bone formation in the inter-trabecular space (Alexander et al. Citation2011). Macrophages are important in both the onset and resolution of inflammation (Wu et al. Citation2013), and in the broadest of definitions they are divided into the inflammatory M1 and the anabolic M2 subcategories. In shaft fractures, macrophages appear to be important for collagen deposition and for the conversion of cartilage to bone (Schlundt et al. Citation2015). Their depletion leads to impaired callus formation (Raggatt et al. Citation2014) and impaired shaft fracture healing. In contrast, the role of macrophages in cancellous bone formation is less clear, although there seem to be close interactions between macrophages and osteoblasts in bone formation (Alexander et al. Citation2011, Wu et al. Citation2013). “Osteomacs” is a special term for these macrophages. The anabolic effect of macrophages has been partly linked to Oncostatin M, a cytokine related to IL-6. Mice lacking the receptor for Oncostatin M have a 50% reduction in new-formed bone volume in metaphyseal drill holes after 7 days of healing (Guihard et al. Citation2015).

Cancellous bone healing is sensitive to pharmacological stimulation

Many substances that influence bone will have an effect on cancellous bone healing. This includes PTH, BMPs, bisphosphonates, and anti-sclerostin antibodies. This demonstrates that although the cancellous healing response is robust, it is still sensitive to manipulation by both anti-resorptive and anabolic drugs (Skoglund et al. Citation2004, Meunier and Aspenberg Citation2006, Tsiridis et al. Citation2007, Morgan et al. Citation2008, Aspenberg et al. Citation2010, Kolios et al. Citation2010, McDonald et al. Citation2012, Sandberg and Aspenberg Citation2015a and b). In cancellous bone, the strong early bone formation response is balanced by almost equally strong bone resorption, although with a slight delay. As a consequence, anti-resorptive drugs such as bisphosphonates and denosumab would be expected to have a greater effect in these settings compared to cortical healing.

There are very few animal models for mechanical evaluation of cancellous healing

The development of animal models for cancellous bone healing is hampered by the difficulty in adequate mechanical evaluation. Various imaging techniques present an easier option, but it is difficult to assess the mechanical competence of bone from its radiological appearance (McClelland et al. Citation2007). Furthermore, the main function of bone healing is to restore mechanical competence. It would therefore make sense to focus on mechanical readouts whenever possible, and to consider other variables as secondary. The literature contains a number of models of cancellous bone healing that allow mechanical evaluation, each with its own pros and cons (Table).

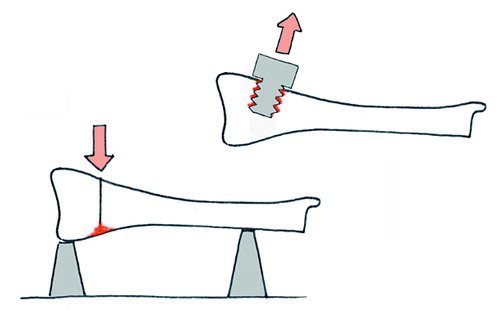

Cancellous bone functions to a large extent by resisting compression. However, tests of the compressive strength of an osteotomy might be difficult to interpret, because fragments that have not united at all could still cause compression resistance after some impaction has occurred. So most models instead use osteotomies with different forms of bending tests. An alternative is to insert screws in holes drilled into cancellous bone of the metaphysis. After a given period of healing, the pullout resistance can be measured (). The pullout force increases dramatically over the first few weeks, and has been shown to correlate with the amount of new bone formed around the screw (Bernhardsson et al. Citation2015).

Figure 5. The principle behind most available models for mechanical testing of cancellous healing. Red denotes the area that contributes to the mechanical properties measured.

Estimations from finite element analyses in combination with screw pullout testing on human cadavers suggest that a change in screw positioning as small as 0.5 mm could change the pullout force by up to a quarter (Procter et al. Citation2015), indicating that pullout force is sensitive to local variation in trabecular geometry.

Fracture fixation is a major engineering challenge in metaphyseal healing models involving osteotomies. In rodents, the cancellous part of the metaphysis does not extend far from the joint. This leaves little space for fixation devices. Moreover, the metaphysis is vaguely defined, and several experimental models of metaphyseal healing use osteotomies at a level where there is little cancellous bone. Young rodents grow quickly, and a fracture induced in a cancellous region of many models might—after 3-4 weeks—find itself in a non-trabecular medullary space.

We believe that a relevant metaphyseal bone healing model should be situated where the marrow cavity contains cancellous bone. At the same time, it should be stable enough so that little cartilage and external callus forms. This should be combined with a sufficiently low variation of a relevant mechanical outcome variable.

To conclude, cancellous bone normally heals by a fast, spatially limited, membranous bone formation process devoid of cartilage and external callus. The differences in biological processes together with differences in local stem cell availability mean that in contrast to shaft healing, cancellous bone healing can respond differently to ageing and various manipulations such as loading or drug treatments. This underscores the importance of using adequate animal models when exploring various aspects of fracture healing.

OS performed the literature study and wrote the first draft, with continuous discussion with PA. Both authors then edited the manuscript together.

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2031-47-5), the EU Seventh Framework program (FP7/2007- 2013, grant 279239), and a grant from Linköping University.

Published models that allow mechanical evaluation of cancellous healing

- Alexander K A, Chang M K, Maylin E R, Kohler T, Muller R, Wu A C, et al. Osteal macrophages promote in vivo intramembranous bone healing in a mouse tibial injury model. J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26 (7): 1517–32.

- Alt V, Thormann U, Ray S, Zahner D, Durselen L, Lips K, et al. A new metaphyseal bone defect model in osteoporotic rats to study biomaterials for the enhancement of bone healing in osteoporotic fractures. Acta Biomater 2013; 9 (6): 7035–42.

- Aspenberg P, Sandberg O. Distal radial fractures heal by direct woven bone formation. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (3): 297–300.

- Aspenberg P, Genant H K, Johansson T, Nino A J, See K, Krohn K, et al. Teriparatide for acceleration of fracture repair in humans: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 102 postmenopausal women with distal radial fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25 (2): 404–14.

- Bernhardsson M, Sandberg O, Aspenberg P. Experimental models for cancellous bone healing in the rat. Acta Orthop 2015: 86(6): 745–50.

- Bogoch E, Gschwend N, Rahn B, Moran E, Perren S. Healing of cancellous bone osteotomy in rabbits–Part I: Regulation of bone volume and the regional acceleratory phenomenon in normal bone. J Orthop Res 1993a; 11 (2): 285–91.

- Bogoch E, Gschwend N, Rahn B, Moran E, Perren S. Healing of cancellous bone osteotomy in rabbits–Part II: Local reversal of arthritis-induced osteopenia after osteotomy. J Orthop Res 1993b; 11 (2): 292–8.

- Charnley J, Baker S L. Compression arthrodesis of the knee; a clinical and histological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1952; 34-B (2): 187–99.

- Chen W T, Han da C, Zhang P X, Han N, Kou Y H, Yin X F, et al. A special healing pattern in stable metaphyseal fractures. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (2): 238–42.

- Claes L, Veeser A, Gockelmann M, Simon U, Ignatius A. A novel model to study metaphyseal bone healing under defined biomechanical conditions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009; 129 (7): 923–8.

- Claes L, Reusch M, Gockelmann M, Ohnmacht M, Wehner T, Amling M, et al. Metaphyseal fracture healing follows similar biomechanical rules as diaphyseal healing. J Orthop Res 2011; 29 (3): 425–32.

- Colnot C. Skeletal cell fate decisions within periosteum and bone marrow during bone regeneration. J Bone Miner Res 2009; 24 (2): 274–82.

- Cooper S. A Dictionary of practical surgery. Harper & Bros. 1845.

- Diamond T H, Clark W A, Kumar S V. Histomorphometric analysis of fracture healing cascade in acute osteoporotic vertebral body fractures. Bone 2007; 40 (3): 775–80.

- Draenert K, Draenert Y. The architecture of metaphyseal bone healing. Scan Electron Microsc 1979; (2): 521–8.

- Dupuytren G. (Ed. Clark F L G) On the injuries and diseases of bones. The Sydenham society, London, 1847.

- Einhorn T A, Simon G, Devlin V J, Warman J, Sidhu S P, Vigorita V J. The osteogenic response to distant skeletal injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72 (9): 1374–8.

- Gaudilliere B, Fragiadakis G K, Bruggner R V, Nicolau M, Finck R, Tingle M, et al. Clinical recovery from surgery correlates with single-cell immune signatures. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6 (255): 255ra131.

- Gazit D, Karmish M, Holzman L, Bab I. Regenerating marrow induces systemic increase in osteo- and chondrogenesis. Endocrinology 1990; 126 (5): 2607–13.

- Gerstenfeld L C, Cho T J, Kon T, Aizawa T, Cruceta J, Graves B D, et al. Impaired intramembranous bone formation during bone repair in the absence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. Cells Tissues Organs 2001; 169 (3): 285–94.

- Glass G E, Chan J K, Freidin A, Feldmann M, Horwood N J, Nanchahal J. TNF-alpha promotes fracture repair by augmenting the recruitment and differentiation of muscle-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108 (4): 1585–90.

- Guihard P, Boutet M A, Brounais-Le Royer B, Gamblin A L, Amiaud J, Renaud A, et al. Oncostatin m, an inflammatory cytokine produced by macrophages, supports intramembranous bone healing in a mouse model of tibia injury. Am J Pathol 2015; 185 (3): 765–75.

- Gulliver G. On the reparation of fractured bones. 1835.

- Han D, Han N, Chen Y, Zhang P, Jiang B. Healing of cancellous fracture in a novel mouse model. Am J Transl Res 2015; 7 (11): 2279–90.

- Han N, Zhang P X, Wang W B, Han D C, Chen J H, Zhan H B, et al. A new experimental model to study healing process of metaphyseal fracture. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012; 125 (4): 676–9.

- Han D, Han N, Xue F, Zhang P. A novel specialized staging system for cancellous fracture healing, distinct from traditional healing pattern of diaphysis corticalfracture? Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8 (1): 1301–4.

- Histing T, Klein M, Stieger A, Stenger D, Steck R, Matthys R, et al. A new model to analyze metaphyseal bone healing in mice. J Surg Res 2012; 178 (2): 715–21.

- Jarry L, Uhthoff H K. Differences in healing of metaphyseal and diaphyseal fractures. Can J Surg 1971; 14 (2): 127–35.

- Jungbluth P, Hakimi A R, Grassmann J P, Schneppendahl J, Betsch M, Kropil P, et al. The early phase influence of bone marrow concentrate on metaphyseal bone healing. Injury 2013; 44 (10): 1285–94.

- Kaspar D, Neidlinger-Wilke C, Holbein O, Claes L, Ignatius A. Mitogens are increased in the systemic circulation during bone callus healing. J Orthop Res 2003; 21 (2): 320–5.

- Kolios L, Hoerster A K, Sehmisch S, Malcherek M C, Rack T, Tezval M, et al. Do estrogen and alendronate improve metaphyseal fracture healing when applied as osteoporosis prophylaxis? Calcif Tissue Int 2010; 86 (1): 23–32.

- Kon T, Cho T J, Aizawa T, Yamazaki M, Nooh N, Graves D, et al. Expression of osteoprotegerin, receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (osteoprotegerin ligand) and related proinflammatory cytokines during fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res 2001; 16 (6): 1004–14.

- Lutz M, Steck R, Sitte I, Rieger M, Schuetz M, Klestil T. The metaphyseal bone defect in distal radius fractures and its implication on trabecular remodeling-a histomorphometric study (case series). J Orthop Surg Res 2015; 10: 61.

- McClelland D, Thomas P B, Bancroft G, Moorcraft C I. Fracture healing assessment comparing stiffness measurements using radiographs. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007; 457: 214–9.

- McDonald M M, Morse A, Mikulec K, Peacock L, Yu N, Baldock P A, et al. Inhibition of sclerostin by systemic treatment with sclerostin antibody enhances healing of proximal tibial defects in ovariectomized rats. J Orthop Res 2012; 30 (10): 1541–8.

- Meunier A, Aspenberg P. Parecoxib impairs early metaphyseal bone healing in rats. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2006; 126 (7): 433–6.

- Monfoulet L, Rabier B, Chassande O, Fricain J C. Drilled hole defects in mouse femur as models of intramembranous cortical and cancellous bone regeneration. Calcif Tissue Int 2010; 86 (1): 72–81.

- Morgan E F, Mason Z D, Bishop G, Davis A D, Wigner N A, Gerstenfeld L C, et al. Combined effects of recombinant human BMP-7 (rhBMP-7) and parathyroid hormone (1-34) in metaphyseal bone healing. Bone 2008; 43 (6): 1031–8.

- Obrant K J. Trabecular bone changes in the greater trochanter after fracture of the femoral neck. Acta Orthop Scand 1984; 55 (1): 78–82.

- Procter P, Bennani P, Brown C J, Arnoldi J, Pioletti D P, Larsson S. Variability of the pullout strength of cancellous bone screws with cement augmentation. Clin Biomech 2015; 30 (5): 500–6.

- Rabie A B, Dan Z, Samman N. Ultrastructural identification of cells involved in the healing of intramembranous and endochondral bones. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996; 25 (5): 383–8.

- Raggatt L J, Wullschleger M E, Alexander K A, Wu A C, Millard S M, Kaur S, et al. Fracture healing via periosteal callus formation requires macrophages for both initiation and progression of early endochondral ossification. Am J Pathol 2014; 184 (12): 3192–204.

- Sandberg O. Metaphyseal fracture healing. In: Division of Clinical Sciences Metaphyseal fracture healing. Linköping University: Sweden; 2016; Doctoral dissertation; 22.

- Sandberg O, Aspenberg P. Different effects of indomethacin on healing of shaft and metaphyseal fractures. Acta Orthop 2015a; 86 (2): 243–7.

- Sandberg O H, Aspenberg P. Glucocorticoids inhibit shaft fracture healing but not metaphyseal bone regeneration under stable mechanical conditions. Bone Joint Res 2015b; 4 (10): 170–5.

- Schatzker J, Waddell J, Stoll J E. The effects of motion on the healing of cancellous bone. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; (245): 282–7.

- Schindeler A, Liu R, Little D G. The contribution of different cell lineages to bone repair: exploring a role for muscle stem cells. Differentiation 2009; 77 (1): 12–8.

- Schlundt C, El Khassawna T, Serra A, Dienelt A, Wendler S, Schell H, et al. Macrophages in bone fracture healing: Their essential role in endochondral ossification. Bone 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Sevitt S. The healing of fractures of the lower end of the radius. A histological and angiographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1971; 53 (3): 519–31.

- Siclari V A, Zhu J, Akiyama K, Liu F, Zhang X, Chandra A, et al. Mesenchymal progenitors residing close to the bone surface are functionally distinct from those in the central bone marrow. Bone 2013; 53 (2): 575–86.

- Skoglund B, Holmertz J, Aspenberg P. Systemic and local ibandronate enhance screw fixation. J Orthop Res 2004; 22 (5): 1108–13.

- Stuermer E K, Sehmisch S, Rack T, Wenda E, Seidlova-Wuttke D, Tezval M, et al. Estrogen and raloxifene improve metaphyseal fracture healing in the early phase of osteoporosis. A new fracture-healing model at the tibia in rat. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2010; 395 (2): 163–72.

- Tsiridis E, Morgan E F, Bancroft J M, Song M, Kain M, Gerstenfeld L, et al. Effects of OP-1 and PTH in a new experimental model for the study of metaphyseal bone healing. J Orthop Res 2007; 25 (9): 1193–203.

- Tu J, Henneicke H, Zhang Y, Stoner S, Cheng T L, Schindeler A, et al. Disruption of glucocorticoid signaling in chondrocytes delays metaphyseal fracture healing but does not affect normal cartilage and bone development. Bone 2014; 69: 12–22.

- Uhthoff H K, Rahn B A. Healing patterns of metaphyseal fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981; (160): 295–303.

- Uusitalo H, Rantakokko J, Ahonen M, Jamsa T, Tuukkanen J, KaHari V, et al. A metaphyseal defect model of the femur for studies of murine bone healing. Bone 2001; 28 (4): 423–9.

- Weber A J, Li G, Kalak R, Street J, Buttgereit F, Dunstan C R, et al. Osteoblast-targeted disruption of glucocorticoid signalling does not delay intramembranous bone healing. Steroids 2010; 75 (3): 282–6.

- Vicenti G, Pesce V, Tartaglia N, Abate A, Mori C M, Moretti B. Micromotion in the fracture healing of closed distal metaphyseal tibial fractures: A multicentre prospective study. Injury 2014; 45Suppl6: S27–S35.

- Wu A C, Raggatt L J, Alexander K A, Pettit A R. Unraveling macrophage contributions to bone repair. Bonekey Rep 2013; 2: 373.

- Xiao W, Mindrinos M N, Seok J, Cuschieri J, Cuenca A G, Gao H, et al. A genomic storm in critically injured humans. J Exp Med 2011; 208 (13): 2581–90.

- Zhang X, Schwarz E M, Young D A, Puzas J E, Rosier R N, O’Keefe R J. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates mesenchymal cell differentiation into the osteoblast lineage and is critically involved in bone repair. J Clin Invest 2002; 109 (11): 1405–15.