Abstract

Background and purpose — Recurrent dislocation is the commonest cause of early revision of a total hip arthropasty (THA). We examined the effect of femoral head size and surgical approach on revision rate for dislocation, and for other reasons, after total hip arthroplasty (THA).

Patients and methods — We analyzed data on 166,231 primary THAs and 3,754 subsequent revision THAs performed between 2007 and 2015, registered in the Dutch Arthroplasty Register (LROI). Revision rate for dislocation, and for all other causes, were calculated by competing-risk analysis at 6-year follow-up. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression ratios (HRs) were used for comparisons.

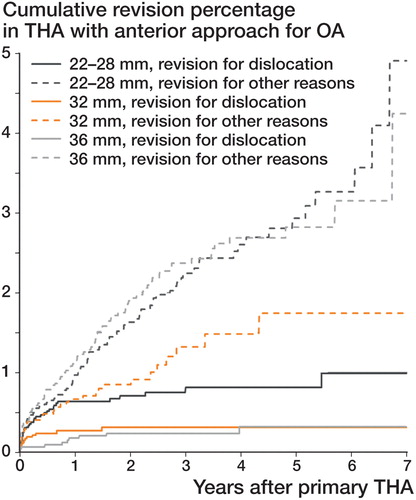

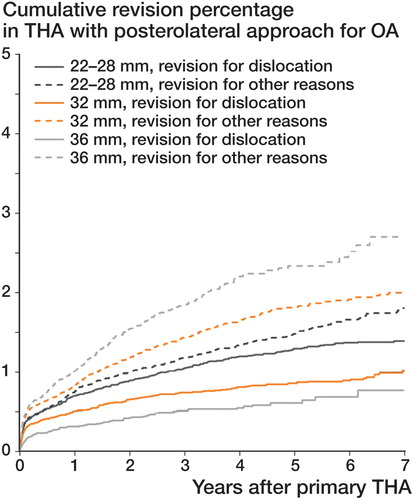

Results — Posterolateral approach was associated with higher dislocation revision risk (HR =1) than straight lateral, anterolateral, and anterior approaches (HR =0.5–0.6). However, the risk of revision for all other reasons (especially stem loosening) was higher with anterior and anterolateral approaches (HR =1.2) and lowest with posterolateral approach (HR =1). For all approaches, 32-mm heads reduced the risk of revision for dislocation compared to 22- to 28-mm heads (HR =1 and 1.6, respectively), while the risk of revision for other causes remained unchanged. 36-mm heads increasingly reduced the risk of revision for dislocation but only with the posterolateral approach (HR =0.6), while the risk of revision for other reasons was unchanged. With the anterior approach, 36-mm heads increased the risk of revision for other reasons (HR =1.5).

Interpretation — Compared to the posterolateral approach, direct anterior and anterolateral approaches reduce the risk of revision for dislocation, but at the cost of more stem revisions and other revisions. For all approaches, there is benefit in using 32-mm heads instead of 22- to 28-mm heads. For the posterolateral approach, 36-mm heads can safely further reduce the risk of revision for dislocation.

Recurrent dislocation is the most common cause of early revision of a primary THA, while aseptic loosening is most often the reason for late revision (Phillips et al. Citation2003, Meek et al. Citation2006, Hailer et al. Citation2012, Howie et al. Citation2012, LROI Report Citation2015, Australian Joint Registry Report Citation2015). In the Netherlands, 20% of revision THAs are performed for recurrent dislocation (LROI Report Citation2015).

Several risk factors for a dislocating hip have been identified, such as implant orientation, surgical technique (both approach and surgical skills), sex, femoral neck fracture as indication, and neuromuscular disease (Mansonis and Bourne Citation2002, Guyen et al. Citation2007, Citation2009). In recent times, the surgical approach and use of larger femoral heads have received more attention as a possible solution to this problem (Hailer et al. Citation2012, Howie et al. Citation2012, Kostensalo et al. Citation2013, Stroh et al. Citation2013).

Recently, the direct anterior surgical approach has become popular and the number of surgeons using this approach is growing (Christensen et al. Citation2014, Clyburn Citation2015, Sheth et al. Citation2015). Several studies have suggested that there is a more stable hip and faster recovery if the surgical dissection is done using the anterior approach (Matta and Ferguson Citation2005, Barrett et al. Citation2013, Higgins et al. Citation2015). However, other studies have raised concerns about a possible increased risk of complications associated with the anterior approach—such as femoral fractures, wound complications, and neurovascular injury (Kennon et al. Citation2003, Christensen et al. Citation2014, de Geest et al. Citation2015, Gwo-Chin and Marconi Citation2015). In addition, there is a long learning curve (de Steiger et al. Citation2015). Another option to reduce the risk of dislocation is to increase the femoral head size. Several studies have proven this effect of increased head size, both in vitro and in vivo (Hailer et al. Citation2012, Howie et al. Citation2012, Kostensalo et al. Citation2013).

Our aim was to determine the effect of femoral head size and surgical approach on the risk of revision for recurrent dislocation after THA. We hypothesized that increasing the femoral head size would reduce the risk of dislocation more than would the type of surgical approach. Furthermore, we investigated other reasons for medium-term revision of THA associated with surgical approach and femoral head size.

Patients and methods

The Dutch Arthroplasty Register

The Dutch Arthroplasty Register (LROI) is a nationwide population-based register that includes information on joint arthroplasties in the Netherlands since 2007. The LROI was initiated by the Netherlands Orthopaedic Association (NOV), and is well supported by its members, resulting in a completeness of reporting of over 95% for primary THAs and 88% for hip revision arthroplasty (van Steenbergen et al. Citation2015).

For the present study, we included all cases with primary osteoarthritis that had received a primary non-metal-on-metal (MoM) THA, in the period 2007–2015 in a Dutch hospital. Patients operated for other reasons, such as avascular necrosis, dysplasia, and femoral head fracture, were excluded. To prevent a learning curve effect for the anterior approach, the first 150 THAs from each hospital were excluded. The study population consisted of 166,231 non-MoM THAs. The median length of follow-up was 3.3 years, with a maximum of 9 years. Surgical approach was classified as straight lateral, anterolateral, anterior, or posterolateral. Femoral head size was categorized as 22–28 mm, 32 mm, 36 mm, and ≥38 mm. The overall physical condition of the patient was scored using the ASA score (I–IV).

Statistics

Survival time was calculated as the time from primary hip arthroplasty to first revision arthroplasty for any reason, death of the patient, or January 1, 2016. Standard Kaplan-Meier survival analysis leads to overestimation of revision rates (Keurentjes et al. Citation2012, Wongworawat et al. Citation2015). We therefore calculated crude (unadjusted) cumulative incidence of revision using competing-risk analyses (Keurentjes et al. Citation2012). We performed multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to compare adjusted revision rates between the different surgical approaches and femoral head size groups. Adjustments were made for age at surgery, sex, ASA score, fixation (cemented, cementless, hybrid), and the time period during which surgery was performed, to discriminate independent risk factors for revision arthroplasty. For all covariates added to the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses, the proportional hazard assumption was checked and met. Survival analyses were stratified by surgical approach and femoral head size groups. Reasons for revision were described for both the surgical approach and the femoral head size groups; comparison was done using the chi-squared test (SPSS 22.0). Any p-values below 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Funding and potential conflicts of interest

None of the authors have financial or any other competing interests. No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Results

166,231 non-MoM THAs for primary osteoarthritis were performed and registered in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2015. The majority of THA patients were aged between 60 and 74 years, were women, were ASA II, and received a ceramic-on-polyethylene or a metal-on-polyethylene bearing with cementless fixation and a 32-mm or 28-mm head (Table 1, see Supplementary data). Most THAs were performed using the posterolateral approach (n = 100,823), followed by the straight lateral approach (n = 35,830), the anterior approach (n = 14,446), and the anterolateral approach (n = 12,744). Of the THAs performed with a posterolateral approach, 18% used a 36-mm head. In contrast, in the anterior approach THA group, 36-mm heads were used in 31%. Ceramic-on-ceramic couplings were more often placed in patients who were operated using an anterior THA approach (27%) than in patients who were operated with other approaches (5–7%).

Reasons for revision

The most common reasons for revision during the period 2007–2015 were dislocation, loosening of the femoral component, periprosthetic fracture, acetabular loosening, and infection (Table 2, see Supplementary data). In general, dislocation and femoral loosening accounted for 50% of all revisions. The femoral head size and the primary surgical approach had a statistically significant influence on the type of revision required. With 22- to 28-mm heads, the most common reason for revision was dislocation. For each approach, the burden of revisions for dislocation was reduced with larger heads. On the other hand, moving up from 28-mm to 32-mm to 36-mm heads increased the likelihood of revision for femoral loosening. Posterolateral approaches in primary THA were more often associated with revision for dislocation, whereas the anterolateral and anterior approaches were more often associated with revision for femoral loosening.

Risk of revision due to dislocation

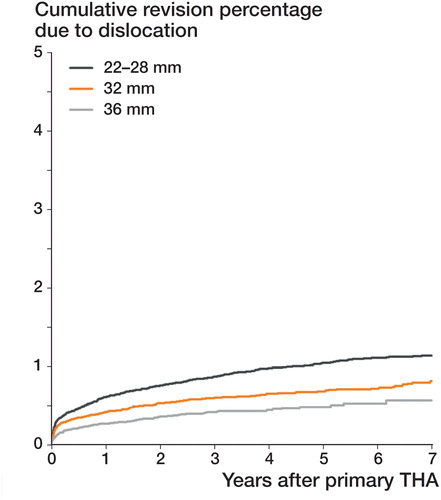

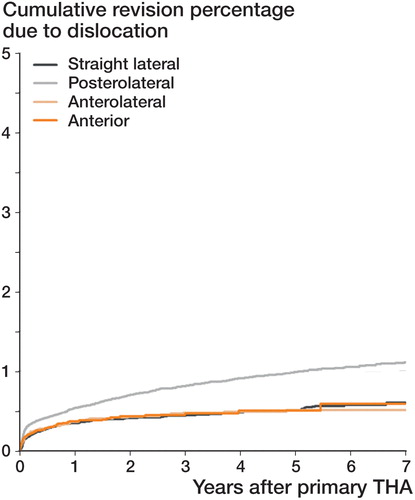

The overall risk of revision for dislocating THA was low. This (unadjusted) risk was 1.1% for 22- to 28-mm femoral heads during the six-year follow-up (). THA with 32-mm heads showed a statistically significantly lower risk of revision for dislocation (0.7%); 36-mm heads had a significantly lower risk (0.5%) (). The overall 6-year revision rate for dislocation, stratified by surgical approach, was 0.5–0.6% for either anterolateral, straight lateral, or anterior approach, while the unadjusted 6-year revision rate for the posterolateral approach was 1.1% (p < 0.05) ( and ). With stratification for head size, in the 22- to 28-mm head groups, the posterolateral approach showed a higher risk of revision for dislocation than the straight lateral and anterolateral approaches, but there was no difference from the anterior approach (). In the 32-mm head group, the posterolateral approach had a higher risk of revision for dislocation than all other approaches. With 36-mm heads, the risk of revision for dislocation was similar between the approaches.

Figure 1. Crude cumulative hazard of revision due to dislocation, according to head diameter, in non-MoM THA in patients with osteoarthritis in the Netherlands in the period 2007–2015 (n = 166,231).

Figure 2. Crude cumulative hazard of revision due to dislocation, according to surgical approach, in non-MoM THA in patients with osteoarthritis in the Netherlands in the period 2007–2015 (n = 166,231).

Table 3. Crude cumulative 6-year revision rates for dislocation, for any reason except dislocation, and for all causes, for patients who received a non MoM THA for osteoarthritis in 2007-2015 in the Netherlands, according to femoral head size group (n = 166,231)

Risk of revision for other reasons

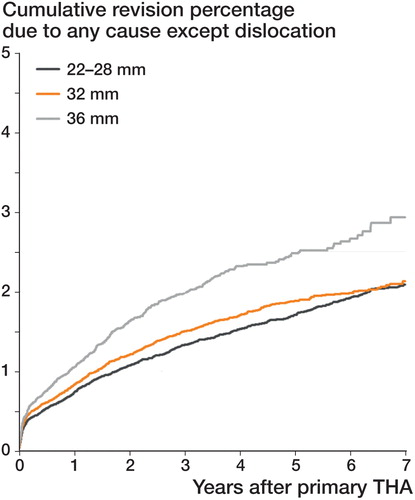

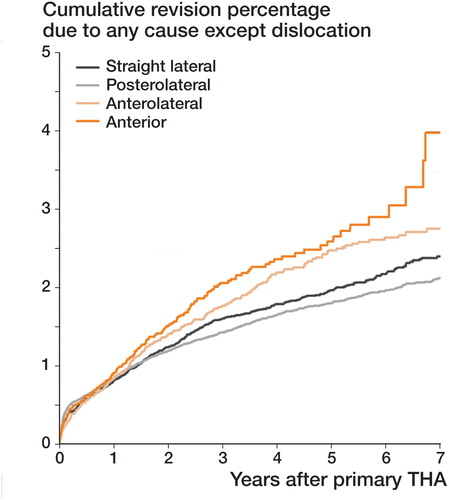

Apart from dislocation, there are other reasons for revision of a primary THA—such as femoral loosening and periprosthetic fractures. The crude 6-year risk of revision for these other reasons was comparable for 22- to 28-mm and 32-mm head sizes (1.9–2.0%); 36-mm heads had a significantly higher risk of revision (2.7%) ( and ). Revisions for all other reasons were more common with the anterior and anterolateral approaches than with the posterolateral approach: the crude risk of revision was 2.9% and 2.6%, respectively, as opposed to 2.0% (p < 0.05) (). When we stratified for head size in the 22- to 28-mm head groups, the anterolateral approach and especially the anterior approach showed a statistically significantly higher risk of revision for other reasons than the posterolateral and straight lateral approaches (2.5% and 3.3% as opposed to 1.7% and 2.0%) ( and and ). In the 32-mm and 36-mm head groups, the risk of revision for other reasons was similar for all 4 surgical approaches. The overall risk of revision for any reason within 6 years was statistically significantly lower with 32-mm heads (2.7%) than with either 22- to 28-mm heads or 36-mm heads (3.1% and 3.2%, respectively). The overall risk of revision for any reason was highest with the anterior approach (3.5%), and lowest with the straight lateral approach (2.7%) ().

Figure 3. Crude cumulative hazard of revision for any reason except dislocation, according to head diameter, in non-MoM THA patients with osteoarthritis in the Netherlands in the period 2007–2015 (n = 166,231).

Figure 4. Crude cumulative hazard of revision for any reason other than dislocation, according to surgical approach, in non-MoM THA patients with osteoarthritis in the Netherlands in the period 2007–2015 (n = 166,231).

Multivariable analysis: risk of revision due to dislocation

Since the risk of revision can be influenced by case mix and prosthetic fixation, we also performed multivariable survival analyses, adjusted for age, gender, ASA score, fixation, and time period of primary THA. These analyses (Table 4A, see Supplementary data) showed that the risk of revision due to dislocation was around 60% higher for 22- to 28-mm femoral heads than for 32-mm femoral heads (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.6). This was true for all 4 approaches. However, the data suggested that there was a higher relative risk of revision for dislocation when using a 22- to 28-mm head with anterolateral and anterior approaches (HR =2.8 and 2.4), compared to the posterolateral and straight lateral approaches (HR =1.5 and 1.8). 36-mm heads reduced the risk of revision for dislocation by around 40% (HR =0.6) relative to 32-mm heads. When stratified by approach, this was only statistically significant for the posterolateral approach. The posterolateral approach resulted in higher revision rates due to dislocation compared to all other surgical approaches (HR =1.0 vs. 0.5–0.6) (Table 4B, see Supplementary data); this difference was significant for head sizes of 22 to 28 mm and 32 mm, but not for 36 mm. Cemented THA reduced the risk of revision for dislocation by about 20% compared to cementless fixation. Age did not affect the risk of revision for dislocation. Males had an increased risk of revision for dislocation, as did patients with an ASA class of II or higher (Table 4A, see Supplementary data).

Multivariable analysis: risk of revision for other reasons

Femoral head sizes of 22 to 28 mm and 32 mm had a comparable risk of revision for any reason except dislocation, while 36-mm femoral head THAs had a 16% increased risk (Table 5A, see Supplementary data). Stratified by approach, a 36-mm head (and 22- to 28-mm head) had an increased risk of revision (HR =1.5) but only when the anterior approach had been used. The posterolateral approach was associated with a significantly lower risk of revision for any reason except dislocation, compared to the anterolateral and anterior approaches (HR =1 vs. 1.2). Stratified by head size (Table 5B, see Supplementary data), this was significant only for the 22- to 28 mm head group. Cemented and hybrid THAs showed a 40% lower risk of revision for other reasons compared to cementless fixation, whereas reversed hybrid fixation had an even higher risk of revision (HR =1.4), mainly when the anterolateral approach had been used. Younger patients (< 60 years) had increased risk of revision (HR =1.3), as did males and patients with higher ASA classifications (Table 5A, see Supplementary data).

Discussion

Despite the fact that our knowledge of risk factors has improved and the treatment options have also widened, a dislocating THA is still a major problem. We used data from the Dutch Arthroplasty Register (LROI) to investigate 2 major determinants of THA dislocation, femoral head size and surgical approach, and compared their effect on the risk of THA revision for dislocation with their effect on the risk of THA revision for other reasons, at 6-year follow-up. Our data show that the revision rate for dislocation after THA in the Netherlands is acceptable (around 1%), but that it is higher for primary THAs inserted using a posterolateral approach, and for 22- to 28-mm femoral head sizes. However, the risk of THA revision for any reason other than dislocation was highest after the direct anterior approach (2.9%) and lowest after the posterolateral approach (2.0%).

Surgical approach

One of the major changes that has occurred in hip arthroplasty in the past few years is the increased interest in the direct anterior approach. A possible reason may be the claim of less tissue damage and faster rehabilitation. Whether or not this is the case, at 1- to 3-year follow-up these possible advantages did not result in better patient-reported outcomes when compared to the posterolateral approach (Amlie et al. Citation2014). Several studies have suggested that there is a reduced risk of dislocation with the anterior approach relative to the posterolateral approach (Dudda et al. Citation2010, de Geest et al. Citation2015, Higgins et al. Citation2015, Sheth et al. Citation2015). This has also been reported in studies comparing the (antero-) lateral approach and the posterolateral approach (Arthursson et al. Citation2007, Lindgren et al. Citation2012). Our data confirm that there is a lower risk of revision for dislocation with the anterolateral, anterior, and straight lateral approaches than with the posterolateral approach. Even so, the absolute risk of revision due to dislocation was small in all groups (around 0.5–1%). In the anterior and anterolateral approach groups, the major reason for revision was aseptic loosening of the stem. We hypothesize that the femoral exposure with the anterior approach is difficult, and may result in a femoral fracture or in the choice of a slightly undersized stem. This in turn might lead to failed ingrowth of the stem or to aseptic loosening. Similarly, Panichkul et al. (Citation2015) also found more stem revisions after the anterior approach than after the posterolateral or straight lateral approach.

Due to the recent popularity of the anterior approach, a growing number of patients were treated with this approach. To compensate for a learning curve, we excluded a number of cases. A study based on the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry concluded that 50 or more procedures would have to be performed by a surgeon before the rate of revision was no different from when performing 100 or more procedures (de Steiger et al. Citation2015). Even with the exclusion of the first 150 patients at each hospital, we still found that the 6-year risk of other revisions (i.e. revisions other than for dislocation) was highest with the anterior approach.

Femoral head size

Increasing femoral head diameter is another method for reducing dislocations in THA. A larger-diameter head reduces the risk of dislocation due to greater jumping distance and a greater range of motion before impingement (Howie et al. Citation2012, Stroh et al. Citation2013). In clinical practice, larger heads became popular because of metal-on-metal bearings. These bearings did indeed lead to fewer dislocations, but resulted in pseudotumors and other severe complications (Zijlstra et al. Citation2011, Van der Veen et al. Citation2015). Since then, the use of large (> 38-mm) heads declined, partly based on advice from the Netherlands Orthopaedic Association regarding large-head (≥ 36-mm) MoM bearings (Verheyen and Verhaar Citation2012), while the use of 32-mm and 36-mm heads increased (LROI Report Citation2015). In the present study, increasing the head size from 28 mm to 32 mm resulted in reduction of the risk of revision for dislocation. A further increase in head size to 36 mm resulted in further reduction of risk. Our results confirm those of other studies comparing dislocation rates with various femoral head sizes (Bystrom et al. Citation2003, Berry et al. Citation2005, Bistolfi et al. Citation2011, Hailer et al. Citation2012, Howie et al. Citation2012, Kostensalo et al. Citation2013). Sariali et al. (Citation2009) also showed mathematically that jumping distance increases with increasing head size (from 22 mm to 36 mm), lowering the risk of dislocation. With much larger heads, there was no further increase in jumping distance. Possible drawbacks from increased head size in polyethylene liners might be increased wear of the liner and increased taper corrosion. Polyethylene crosslinking should hopefully combat this problem, and taper corrosion may be less likely if ceramic or oxidized zirconium heads are used instead of metal heads. Nonetheless, increasing head size will result in a thinner liner, which may make it more vulnerable to damage or breakage (Ries and Pruitt Citation2005).

One limitation of our study was that there were no data on non-surgically treated THA dislocations. For that matter, THA dislocations were probably present also in the "other reasons for revision" group. Secondly, the LROI has no radiological data, which would enable comparison of component position between groups. We are aware of the fact that dislocations can have multiple causes, but retrieving the relevant data in all cases is impossible; we therefore chose revision due to dislocation as a reliable endpoint. Finally, no functional and pain results (PROMs) are reported (Amlie et al. Citation2014).

To summarize, we found that revisions for dislocation after THA were more frequent after posterolateral approach THA and when using a 22- to 28-mm femoral head. Switching to another surgical approach can therefore reduce revision rates for dislocation, but at the expense of higher rates of revision for other reasons, especially with the direct anterior and anterolateral approaches. The risk of revision for other reasons (mainly femoral loosening) was highest with the anterior approach and lowest with the posterolateral approach. This effect was present despite our exclusion of the first 150 anterior hip approaches at each hospital. Patients and surgeons considering these approaches should therefore be cautious about this increased and previously unreported risk. Using larger femoral heads can also combat dislocation risk. Our data show that for all approaches, the use of 32-mm heads reduced revisions for dislocation substantially compared to the use of 22- to 28-mm heads. Furthermore, 32-mm heads did not increase the risk of revision for other reasons. For the posterolateral approach, 36-mm heads could safely reduce the risk of revision for dislocation further. This can be considered in patients who are at higher risk of dislocation, such as ASA III–IV patients and male patients.

Supplementary data

Tables 1, 2, 4, and 5 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1317515.

WZ conceived and planned the study, in collaboration with RN and WS. LS was responsible for the dataset, and performed the analyses together with WZ. BH and WZ wrote the manuscript, with substantial contributions from all authors, who also participated in interpretation of the results.

IORT_A_1317515_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (43.7 KB)- Amlie E, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Baste V, Nordsletten L, Hovik O, Dimmen S. Worse patient-reported outcome after lateral approach than after anterior and posterolateral approach in primary hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2014; 85(5): 463–9.

- Arthursson A J, Furnes O, Espehaug B, Havelin L I, Soreide J A. Prosthesis survival after total hip arthroplasty - does surgical approach matter? Analysis of 19,304 Charnley and 6,002 Exeter primary total hip arthroplasties reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2007; 78(6): 719–29.

- Australian Orthopaedic Association. National Joint Replacement Registry Annual report. Adelaide: AOA; 2015.

- Barrett W P, Turner S E, Leopold J P. Prospective randomized study of direct anterior vs. postero-lateral approach for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28:1634–8.

- Berry D J, von Knoch M, Schleck C D, Harmsen W S. Effect of femoral head diameter and operative approach on risk of dislocation after primary total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87(11): 2456–63.

- Bistolfi A, Crova M, Rosso F, Titolo P, Ventura S, Massazza G. Dislocation rate after hip arthroplasty within the first postoperative years: 36 mm versus 28 mm femoral heads. Hip Int 2011; 21(5): 559–64.

- Bystrom S, Espehaug B, Furnes B, Havelin L I; Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Femoral head size is a risk factor for total hip luxation: a study of 42,987 primary total hip arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty register. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74(5): 514–24.

- Christensen C P, Karthikeyan T, Jacobs C A. Greater prevalence of wound complications requiring reoperation with direct anterior approach total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29: 1839–41.

- Clyburn T A. Anterior and anterolateral approaches for THA are associated with lower dislocation risk without higher revision risk. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473: 3409–11.

- Dudda M, Gueleryuez A, Gautier E, Busato A, Roeder C. Risk factors for early dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: a matched case-control study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2010; 18: 179–83.

- De Geest T, Fennema P, Lenaerts, De Loore G. Adverse effects associated with the direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2015; 135: 1183–92.

- Guyen O, Pibarot V, Vaz G, Chevillotte C, Carret J P, Bejui-Hugues J. Unconstrained tripolar implants for primary total hip arthroplasty in patients at risk for dislocation. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22: 849–58.

- Guyen O, Pibarot V, Vaz G, Chevillotte C, Bejui-Hugues J. Use of a dual mobility socket to manage total hip arthroplasty instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 567: 465–72.

- Gwo-Chin L, Marconi D. Complications following direct anterior hip procedures: costs to both patients and surgeons. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30(1): 98–101.

- Hailer N P, Weiss R J, Stark A, Kärrholm J. The risk of revision due to dislocation after total hip arthroplasty depends on surgical approach, femoral head size, sex and primary diagnosis. An analysis of 78,098 operations in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (5): 442–8.

- Higgins BT, Barlow D R, Heagerty N E, Lin TJ . Anterior vs. posterior approach for total hip arthroplasty, a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30: 419–34.

- Howie D, Holubowycz O T, Middleton R, Large articulation study group. Large femoral heads decrease the incidence of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94: 1095–102.

- Kennon R E, Keggi J M, Wetmore R S, Zatorski L E, Huo M H, Keggi K J. Total hip arthroplasty through minimally invasive anterior surgical approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A(suppl4): 39–48.

- Keurentjes J C, Fiocco M, Schreurs B W, Pijls B G, Nouta K A, Nelissen R G. Revision surgery is overestimated in hip replacement. Bone Joint Res 2012; 1(10): 258–62.

- Kostensalo I, Junnila M, Virolainen P, Remes V, Matilainen M, Vahlberg T, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Mäkelä KT. Effect of femoral head size on risk of revision for dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. A population-based analysis of 42,379 primary procedures from the Finnish Arthroplasty register. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (4): 342–7.

- Landelijke Registratie Orthopedische Implantaten (LROI); LROI Report 2015 Blik op uitkomsten; ‘s Hertogenbosch: Netherlands Orthopaedic Association.

- Lindgren V, Garellick G, Karrholm J, Wretenberg P. The type of surgical approach influences the risk of revision in total hip arthroplasty: a study from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register of 90,662 total hip replacements with 3 different cemented prostheses. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(6): 559–65.

- Mansonis J L, Bourne R B. Surgical approach, abductor function, and total hip arthroplasty dislocation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002; (405): 46–53.

- Matta J M, Ferguson T A. The anterior approach for hip replacement. Orthopedics 2005; 28(9): 927–8.

- Meek R M, Allan D B, McPhillips G, Kerr L, Howie C R. Epidemiology of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; (447): 9–18.

- Panichkul P, Parks N, Ho H, Hopper R H Jr, Hamilton W G. New approach and stem increased femoral revision rate in total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2015; 31: 1–7.

- Phillips C B, Barrett J A, Losina E, Mahomed N N, Lingard E A, Guadagnoli E, Baron J A, Harris W H, Poss R, Katz J N. Incidence rates of dislocation, pulmonary embolism and deep infection during the first six months of elective total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85 (1): 20–6.

- Ries M D, Pruitt I. Effect of cross-linking on the microstructure and mechanical properties of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; (440): 149–56.

- Sariali E, Lazennec J Y, Khiami F, Catonne Y. Mathematical evaluation of jumping distance in total hip arthroplasty. Influence of abduction angle, femoral head offset, and head diameter. Acta Orthop 2009; 80(3): 277–82.

- Sheth D, Cafri G, Inacio M C S, Paxton E W, Namba R S. Anterior and anterolateral approaches for THA are associated with lower dislocation risk without higher revision risk. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473: 3401–8.

- Van Steenbergen L N, Denissen G A W, Spooren A, van Rooden S M, van Oosterhout F J, Morrenhof J W, Nelissen R G. More than 95% completeness of reported procedures in the population-based Dutch Arthroplasty Register; External validation of 311,890 procedures. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (4): 498–505.

- De Steiger R N, Lorimer M, Solomon M. What is the learning curve for the anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473 (12): 3860–6.

- Stroh D A, Issa K, Johnson AJ, Delanois R E, Mont M A. Reduced dislocation rates and excellent functional outcomes with large-diameter femoral heads. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28: 1415–20.

- Van der Veen H C, Reininga I H, Zijlstra W P, Boomsma M F, Bulstra S K, van Raay J J. Pseudotumor incidence, cobalt levels and clinical outcome after large head metal-on-metal and conventional metal-on-polyethylene total hip arthroplasty: mid-term results of a randomized controlled trial. Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B: 1481–7.

- Verheyen C C, Verhaar J A. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements. Lancet 2012; 380: 105.

- Wongworawat M D, Dobbs M B, Gebhardt M C, Gioe T J, Leopold S S, Manner P A, Rimnac C M, Porcher R. Editorial: estimating survivorship in the face of competing risks. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473(4); 1173–6.

- Zijlstra W P, Van den Akker-Scheek I, Zee M J, Van Raay J J. No clinical difference between large metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty and 28-mm-head total hip arthroplasty? Int Orthop 2011; 35 (12): 1771–6.