ABSTRACT

Although previous research has argued that the media play a crucial role in populism’s success, we know too little about how populist messages affect preferences for populist parties. To advance this knowledge, we conducted an experiment in which the core of populist rhetoric – constructing the people as innocent in-group opposed to the establishment as culprit out-group – was manipulated in news articles. The findings indicate that when political elites are blamed for a salient national problem, people are more likely to vote for a populist party and less likely to vote for the largest party in government. Populist vote intentions are indirectly affected via blame perceptions. These findings offer important insights into the media’s role in the electoral success of populism.

Populist political parties have become increasingly popular over the last decades. In the Netherlands, for example, Wilders’ right-wing Freedom Party became the second largest party in the general elections of 2017. On the left, Syriza made it into Greece’s government in 2015. In Latin America, populism has been influential for more than a century. The success of populist movements has not gone unnoticed by scholars, with a large body of research explaining populist success from both the supply-side of populist parties and the demand-side of populist voters (e.g. Mudde Citation2004).

On the supply-side, media coverage plays a pivotal role in getting populist viewpoints across (e.g. Krämer Citation2014). The issues addressed by populist parties are newsworthy, which enhances the visibility of populist actors and statements in the mass media (e.g. Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Citation2007; Rooduijn Citation2014). People are assumed to be exposed to populist messages on a regular basis, which may affect how people think about politics and society in important ways (e.g. Krämer Citation2014; Mazzoleni Citation2008; Mudde Citation2004). Mudde, for example, has claimed that media coverage partially caused the success of populist parties. As other scholars have argued that populist communication is highly persuasive, the role of the media in populism’s global electoral success should not be underestimated (Rooduijn Citation2014).

Although scholars have emphasized the relevance of the media in populism’s success, empirical research that explored the effects of exposure to populist messages on populist voting is scarce (for exceptions, see e.g. Bos, van der Brug & de Vreese Citation2011). Despite these few examples, little is known about how populist messages affect populist voting. To arrive at a better understanding of the effects of populist messages on populist voting, and the mechanisms underlying these effects, this paper investigates how messages that frame the ideational core of populism, the moral and causal opposition between the good people and the corrupt elites, affect people’s intentions to vote for a populist party.

There are good reasons to assume populism is inherently about attributions of blame. Populist actors blame more targets than mainstream political actors do (Vasilopoulou, Halikiopoulou, and Exadaktylos Citation2013). Populist messages thus do not simply revolve around the construction of the good people versus the corrupt elites, they also emphasize that the people are blameless victims whereas the corrupt elites are responsible for causing the problems experienced by the people. Attributions of responsibility are found to be persuasive: Messages that emphasize who is responsible for causing societal problems affect people’s beliefs about credit and blame (Iyengar Citation1991). Evaluations of responsibility, in turn, affect people’s vote choice (Bellucci Citation2014; Marsh and Tilley Citation2010). Against this backdrop, the central question of this paper is how citizens’ preferences for the Dutch populist Freedom Party and the largest party in government are affected by populist messages that blame the corrupt political elites for the problems of the heartland.

Integrating research on populism and attributions of responsibility, we conducted an online between-subjects experiment (N = 721). In this experiment, we manipulated the populist core idea of the opposition between the blameless people and the culprit elites by framing blame; either as causal responsibility attributed to the political elites in the EU and the national government or by attributing no blame (also see Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese Citation2017). The results indicate that populist messages lead to stronger preferences for the populist Freedom Party. People with a stronger tie to national identity and a weaker tie to Europe are most likely to align their right-wing populist party preferences with populist messages. These findings allow us to better understand via which message characteristics the media contribute to the success of populist political parties.

The effects of populist communication on party preferences

Populism is characterized by its antagonistic construction of reality. Populist ideology holds that society is divided into two homogenous groups: the people versus the elites. This binary opposition also involves an important moral component as the people are constructed as the innocent in-group, which is betrayed by the evil out-group of the corrupt elites (e.g. Canovan Citation1999; Mudde Citation2004; Ziller and Schübel Citation2015).

The populist distinction between the good people and the corrupt elites can also be emphasized, or framed, in media messages. Mazzoleni (Citation2008) and Krämer (Citation2014) refer to the concept of media populism to describe the process by which the media actively construct the populist discourse. The media may actively engage in populist news coverage by framing issues in binary oppositions of the innocent people versus the corrupt elites (Caiani and della Porta Citation2011). By means of populist framing, the media can emphasize a specific causal interpretation by shifting blame from the people to causally responsible others (Entman Citation1993). We, therefore, define the populist master frame as “causal interpretations that attribute blame to the corrupt elites who are not representing the ‘blameless’ people and their will” (also see Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese Citation2017).

Media-initiated blame attributions affect citizens’ interpretation of societal issues in important ways (Iyengar Citation1991). Specifically, when actors are framed as responsible for causing certain societal problems, they are more likely to be evaluated in negative terms (Iyengar Citation1991). It has also been demonstrated that evaluations of responsibility affect people’s vote choice: If citizens believe that the government is responsible, they are less likely to vote for it (Bellucci Citation2014; Marsh and Tilley Citation2010). Because populist messages are assumed to activate negative schemata of the “culprit” elites among receivers, people who are exposed to populist blame frames are most likely to turn to populist political parties that oppose these elites as well (Vasilopoulou, Halikiopoulou, and Exadaktylos Citation2013).

Attributions of responsibility are related to populism in important ways. In populism, “the people” are represented as the innocent in-group betrayed by the corrupt political elites (e.g. Canovan Citation1999). Attributions of responsibility that shift blame for negative outcomes from the “good” citizens to the “evil” politicians, relate to a similar process of social differentiation by constructing the people as the innocent in-group victimized by the culprit other. Such attributions of causal responsibility for negative outcomes thus touch upon the core definition of populism. But how can exposure to blame attributions affect people’s preferences for political parties?

Research on attributions of responsibility indicates that when responsibility is attributed to the government or the EU, people are likely to accept this culprit out-group construction in their political attitudes (Hobolt, Tilley, and Wittrock Citation2013). Populist actors point their finger to their political opponents in the government and the EU more frequently than mainstream politicians do (Vasilopoulou, Halikiopoulou, and Exadaktylos Citation2013). Hence, populist parties, more than others, emphasize how the establishment has damaged the people’s heartland (Mols and Jetten Citation2014). As blame attributions are frequently articulated in the speeches of populist parties, people should associate these parties with blame attributions as they articulate the causal and moral divide between “us” and “them”.

Previous research indeed found that people align their political opinions with responsibility attributions (e.g. Hobolt, Tilley, and Wittrock Citation2013). Therefore, populist attributions of the blame should result in preferences for political parties that are known to attribute blame to the political elites themselves. Preferences for the largest party in government, in contrast, should be lower for citizens exposed to messages that blame the elites. In line with this reasoning, the central hypotheses of this study are: H1a. Populist blame exposure positively affects populist party preferences. H1b. Populist blame exposure negatively affects governmental party preferences.

Who is most likely to be affected by populist messages?

Political cynicism

Extant research on the demand-side of populism frequently refers to citizens’ political discontent and distrust as motives to vote for populist political parties (e.g. Van Kessel Citation2011). Populist parties are known for their articulation of distrust in the political establishment (Canovan Citation1999). Doing so, they emphasize that the government and the EU cannot be trusted as they do not represent the people’s will. People with a cynical view on politics share this critical worldview, because they also believe that the establishment is not listening to the common voter’s will. In line with this, Bos, van der Brug, and de Vreese (Citation2013) found that populist communication only affects the perceived legitimacy of (right-wing) populist actors among the politically cynical. We, therefore, expect that the effects of populist blame attributions on voting intentions will be strongest for the politically cynical. Specifically, among these citizens, exposure to populist attributions of blame will lead to a higher preference for a populist party (H2a).

Messages that attribute blame to the established political order are attitudinally congruent for politically cynical citizens. These citizens are most likely to believe that political parties in government cannot be trusted (e.g. Belanger and Aarts Citation2006). Exposure to populist messages that blame the establishment is therefore expected to trigger congruent negative schemata vis-à-vis the government (Krämer Citation2014). Cynical citizens should consequentially be less likely to support the established political parties that are deemed responsible for causing societal issues. We, therefore, hypothesize that, among the politically cynical, blame exposure will lead to a lower preference for the largest party in government (H2b).

Exclusionist identity attachment

Citizens assign credit or blame in a biased way: Parties close to the individual are not blamed for negative outcomes whereas opposed parties are not rewarded for positive outcomes (e.g. Marsh and Tilley Citation2010). In a similar vein, although populism can be both inclusionary and exclusionary, identity attachment may play a biasing role for populist attributions of blame.

The concept of “the people” referred to in populism can be understood as the imagined community of the blameless in-group, or the “heartland” as termed by Taggart (Citation2004). The quest for belonging to this national community may motivate people to vote for right-wing populist parties that promise to regenerate feelings of belonging to the in-group (e.g. Mols and Jetten Citation2014). Especially those citizens that feel close to the nation are expected to feel attracted to populist rhetoric that taps into these sentiments of belonging. Against this backdrop, we expect that the populist vote choice of people with stronger national identity attachments is affected most by populist attributions of blame. For these citizens, blame frames are persuasive as they positively distinguish the people’s national in-group from the culpable elites that threaten this in-groups’ identity. Against this backdrop, we expect that the effects of blame exposure on propensity to vote for a right-wing populist party are strongest at higher levels of national identity attachment (H3a).

Right-wing populist voters are characterized by their exclusionist perception of social identity (e.g. Albertazzi and McDonnell Citation2008; Caiani and della Porta Citation2011). People who are likely to support right-wing populist movements view people outside their nation as a threat to national identity. The European Union can be understood as such a threat to the nation-state (Carey Citation2002). Following populism’s rationale, the European Union can be perceived as a bureaucratic, corrupt enemy that threatens the well-being of the people belonging to the nation. Populist ideas construct the European Union as a threat to national identity (Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese Citation2017). Therefore, we expect that the effects of blame exposure are also strongest at lower levels of European identity attachment (H3b). Taken together, the effects of blame exposure should be strongest for citizens with an exclusive identity attachment (H3c).

The mechanism behind the effects of populist blame frames

Ceteris paribus, we hypothesized that blame exposure affects people’s preferences for political parties. However, the underlying mechanism may be less direct. Research on attributions of responsibility found that blame assigned to political actors activate negative stereotypes about these actors (Hewstone Citation1989). These negative perceptions may in turn be used to hold the government accountable at the elections: The responsible political elites are punished and populist parties that are known to be critical of these corrupt political elites are rewarded at the ballot box. This mechanism can be explained in the light of schema theory (e.g. Brewer and Nakamura Citation1984). This theory postulates that blame exposure primes congruent perceptions among receivers. These activated schemata of blame perceptions can be used as a heuristic cue when making a vote decision: those parties that caused the people’s problems should be avoided (the government) whereas those addressing the people’s problems are preferred (the populist party).

In line with this reasoning, we expect that blame exposure activates blame perceptions towards the political elites in the national government and the EU. Since citizens do not always have access to factual information on causal responsibility (e.g. Cutler Citation2004; Hewstone Citation1989), these blame perceptions are subsequently used as informational cue when forming a preference for political parties (see also Marsh and Tilley Citation2010). H4: The effects of populist blame exposure on populist party preferences are mediated by blame perceptions.

Method

Design

This paper reports the results of an experiment with a 3 (Populist blame exposure: the EU versus the national government versus no blame attribution) between-subjects factorial design with control group (also see Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese Citation2017). Respondents were randomly assigned to one of the experimental groups. We compared elitist blame exposure with the no-blame control groups.Footnote1 As robustness check, we also analyzed the hypothesized effects for both blame exposure conditions separately.

Participants

The sample reflected national variation regarding age, gender, voting behaviour and educational level as close as possible, albeit our sample has an overrepresentation of younger and higher educated citizens (see Appendix B for comparison census data). A research organization collected the data from a nationally representative panel. Eligible participants over 18 years old were invited via e-mail and could voluntary opt-in for the online survey experiment by clicking on a link. They were compensated with credits. To ensure participants were both willing and able to read the experimental stimuli, we used a screening question. Only participants that complied with this instruction were used for subsequent analyses. 37.9% of all respondents were retained in the analyses (N = 721). The selection of participants may have biased our findings, as people who were unwilling or unable to read texts and comply to instructions are underrepresented. However, for the online experimental manipulations to succeed, we needed to ensure that participants were actually exposed to the treatment. The mean age of the participants was 47.24 years (SD = 16.62) and 52.9% were female.

Procedure

After accessing the online survey environment, participants were presented with information on the study and were asked to give their consent. Next, they completed the screening question. Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental conditions or the control group. In all conditions, they were exposed to a similar online newspaper article that contained the treatment or control condition. The minimum forced exposure time was 30 seconds (M = 65.70, SD = 75.58). After participants completed the survey, they were debriefed and thanked for their cooperation.

Stimuli

Participants in all conditions were exposed to a newspaper article about the worsening Dutch labour market situation. The external validity was optimized by using existing online newspaper articles of Dutch news websites as template for the stimuli. The articles were thoroughly pre-tested in a pilot study (N = 137). We manipulated populist blame exposure by emphasizing that the ordinary Dutch people’s crisis on the labour market was caused by either the “incompetent” and “failing” EU or the national government. These levels of government were attributed blame for causing the worsening labour market situation facing the ordinary people. In the control condition, the same news story was presented. However, this version did not connect the societal development to the populist opposition between the people and the establishment (see Appendix C for stimuli). All newspaper articles were equal in length and only the independent variables varied between conditions. All sources, statistics, situations, styles, and lay-out were held constant between conditions.

Manipulation checks

The manipulation of populist blame attribution to the establishment was successful: F(1, 713) = 50.22, p < .001. In the blame exposure conditions, participants were significantly more likely to believe the newspaper article framed the worsening labour market situation as a development caused by the establishment (M = 5.01, SD = 1.23) than in the no blame exposure conditions (M = 4.30, SD = 1.41).

Dependent variable

Participants were asked to rate the likelihood they would ever vote for a particular political party. For each of the main Dutch political parties, participants estimated the likelihood they would ever cast their vote on this particular party on a 0 to 100 scale (0 I think I will never vote for this party, 100 It is very possible that I will once vote for this party). Two political parties were of main interest: the right-wing populist party PVVFootnote2 (M = 30.38, SD = 36.28) and the largest party in government VVDFootnote3 (M = 34.19, SD = 33.46).

Moderators

Political distrust/cynicism

Political distrust/cynicism was measured with five items measured on a 7-point scale (Bos and van der Brug Citation2010) (see Appendix A). An exploratory factor analysis provided support for a unidimensional structure of political distrust/cynicism. One component with an eigenvalue of 2.91 explaining 58.1% of the variance was extracted as the optimal solution. Based on this outcome, a scale of political distrust/cynicism was constructed (M = 4.49, SD = 1.14, Cronbach’s α = 0.81). Higher scores on the scale indicate more cynicism/distrust in politics.Footnote4

Exclusionist identity attachment

Social identity attachment was measured with two scales consisting of three items measured on a 7-point scale: Dutch identity attachment (M = 5.43, SD = 1.26, Cronbach’s α = 0.92) and European identity attachment (M = 3.84, SD = 1.49, Cronbach’s α = 0.86).Footnote5 The correlation between both scales was 0.24 (p < .01). Exclusionist identity attachment and political cynicism correlated rather weakly (r = −0.05, p = n.s.). The items are included in Appendix A.

Mediator

Perceptions of the establishment’s responsibility

After exposure to the stimuli and prior to the assessment of the dependent variable, participants were asked to indicate which actors, situations or institutions they themselves believed were causally responsible for the worsening labour market situation described in the newspaper article. Following Iyengar’s (Citation1991) approach, participants’ perceptions of blame were measured with an open-ended question, which was formulated as follows:

The article you just read argued that the labour market situation is worsening in 2015 and 2016. One could think of many potential causes for this, and people differ greatly in their perceptions of causes. Can you describe who or what you feel is most responsible for causing this situation? You can list all your thoughts in the space provided below.

Randomization check

A between-conditions randomization check on the control variables was conducted, which did not reveal significant differences between experimental conditions regarding the control variables.Footnote6

Analysis

We used linear regression analyses to test hypotheses 1 through 3. We estimated the causal mediation model (H4) with the R-package “Mediation” (Tingley et al. Citation2014). We used 1000 simulations to estimate the model with robust standard errors and Quasi-Bayesian Confidence Intervals. This strategy is used to reliably estimate average causal mediation effects whilst overcoming limitations of standard estimation processes based on the product or difference of coefficients (see Tingley et al. Citation2014 for a detailed discussion).

Results

Direct effects of blame attributions on party preferences

In line with hypothesis 1a, participants’ intention to vote for the populist Freedom Party PVV was positively and significantly affected by populist blame exposure: b = 6.53 (SE = 3.17), p = .040, 95% CI [0.30, 12.75], R2 = 0.01. This means that participants who were exposed to populist messages that blamed the establishment were significantly more likely to vote for the right-wing populist party PVV than people exposed to a message that did not use the blame frame (see also ). Participants were significantly less likely to vote for the largest governmental party VVD when exposed to populist attributions of blame: b = −5.71 (SE = 2.83), p = .040, 95% CI [−11.28, −0.15], R2 = 0.01. We found the same effects when we distinguished between EU and governmental blame exposure. Based on these results, H1b can also be supported. Exposure to messages that actively engage in populism by framing attributions of blame resulted in increasing support for the populist party PVV and decreasing support for the largest party in government. Vote intentions for other parties were not affected significantly (see ). In the next steps, we will assess how these effects are moderated by political cynicism and identity attachment, respectively.

Table 1. Mean scores of voting intentions for no blame attribution versus blame attribution.

Are the politically cynical most susceptible to persuasion by populist messages?

To assess whether the effects of blame exposure are strongest for the politically cynical, we estimated a multiple linear regression model (see ). The interaction effect of populist blame exposure and political cynicism on propensity to vote for the populist party PVV was not significant. This means that blame attributions did not have a stronger effect on populist party preferences for the politically cynical. These results are not supportive of H2a.

Table 2. Regression model predicting the effects of blame attribution and political distrust/cynicism on propensity to vote for a populist political party (PVV).

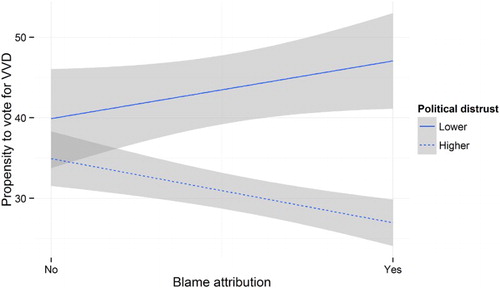

Although political cynicism does not significantly moderate the effects of populist messages on populist party preferences, we did find a significant negative interaction effect of political cynicism and blame exposure on participants’ propensity to vote for the government (see ). These effects were similar for governmental and EU blame exposure. In support of H2b, the politically cynical are thus less likely to vote for the government when exposed to populist attributions of blame (see ).

Figure 1. Interaction effect of blame attribution and political distrust/cynicism on propensity to vote for the governmental party VVD.

Table 3. Regression model predicting the effects of blame attribution and political distrust/cynicism on propensity to vote for the governmental party VVD.

The role of exclusionist identity in the media effects of populist blame attributions

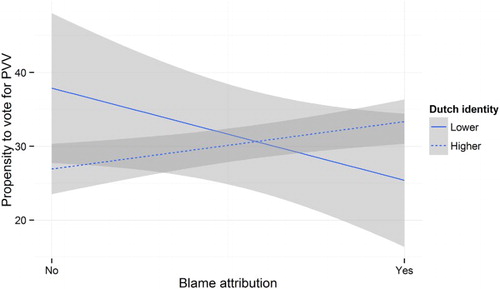

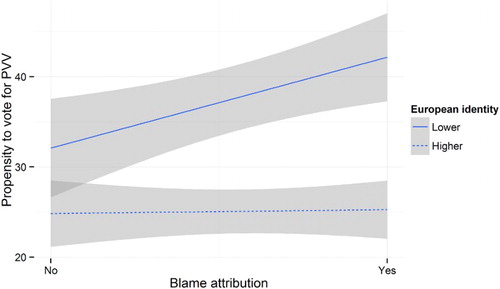

In support of H3a, the effect of blame exposure on propensity to vote for the right-wing populist party PVV is positive at higher levels of national identity attachment (see ). As shown in , participants with a stronger attachment to national identity in the blame attribution condition were more likely to vote for the PVV compared to stronger attached participants in the no blame exposure condition. For people with a weaker national identity attachment, blame exposure resulted in a lower intention to vote for the PVV compared to no blame attribution. For higher levels of national attachment, in contrast, blame exposure resulted in a stronger preference for the PVV. As can be seen in , participants with a weaker attachment to European identity in the blame exposure condition were more likely to vote for the PVV compared to weaker attached participants in the no blame exposure condition. Blame exposure had no effects for participants with a stronger attachment to Europe. In other words, the graphs suggest that the vote choice of participants with an exclusive perception of identity were affected most by exposure to populist attributions of blame.

Figure 2. Interaction effect of blame attribution and Dutch identity attachment on propensity to vote for the populist party PVV.

Figure 3. Interaction effect of blame attribution and European identity attachment on propensity to vote for the populist party PVV.

Table 4. Regression model predicting the effects of blame attribution and identity attachment on propensity to vote for a populist political party (PVV).

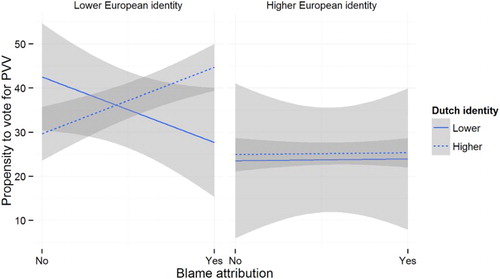

As can be seen in , the three-way interaction effect of blame exposure with national and European identity attachment on populist party preference is negative and significant. As shown by the dashed line on the left-side of , participants with an exclusive identity attachment are indeed affected strongest by blame exposure. A comparison of the mean scores also indicates that the effect of blame exposure on populist party preference is strongest amongst those with an exclusionist social identity: In the no blame condition, these participants have a mean populist party preference of 28.79 (SD = 35.88). In the blame exposure condition, this was substantially and significantly higher (M = 50.08, SD = 39.87; t = 3.97, p < .001, 95% CI [−31.85, −10.73]). In contrast, participants with a stronger or weaker attachment to both the nation and Europe and participants with a weaker attachment to the nation and a stronger attachment to Europe were not affected significantly by populist blame exposure, which supports H3c.

Figure 4. Three-way interaction effect of blame attribution and exclusionist identity attachment on propensity to vote for the populist party PVV.

The effects are similar for EU and governmental blame exposure, although it can be noted that the positive interaction effect of EU blame exposure and national identity attachment and the negative interaction effect of EU blame exposure and European identity attachment are stronger than the effects of governmental blame exposure.

Overall, the results indicate that the vote choice of especially participants with a stronger attachment to national identity is affected by populist blame exposure, which supports H3a. In support of H3c, the results further indicate that citizens with an exclusive perception of identity were affected most by exposure to populist blame frames.

The underlying mechanism of the effects of populist messages

In hypothesis 4, we set out to explore the mediating role of blame perceptions on the effects of blame exposure on vote choice. The estimated mediation model () shows that the effect of blame exposure on propensity to vote for the populist Freedom Party was indeed mediated by citizens’ perceptions of blame. The full mediation model fits the data well: χ2(1) = 0.48, p = .489, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, 90% CI [0.00, 0.05]. Adding the direct effect from blame exposure to propensity to vote for the populist freedom party did not significantly affect model fit: Δ χ2(1) = 0.48, p = .489.

Figure 5. Mediation model demonstrating the mediating role of blame perceptions on the effects of blame attributions on populist party preferences. **p < .01; ***p < .001.

We further estimated the paths in the causal mediation model with the R-package “mediation” (Tingley et al. Citation2014). We found that the effect of blame exposure on propensity to vote for the populist party PVV was significantly mediated by participants’ blame perceptions. The Average Causal Mediation Effect indicated that the mediation model was highly significant (b = 2.92, p < .001, 95% CI [1.01, 4.94]. The Average Direct Effect, however, was non-significant: (b = 1.49, p = .49, 95% CI [−3.21, 6.04]. The total effect was significant: (b = 4.41, p = .04, 95% CI [0.28, 8.64]. These findings indicate that 62.0% of the total effect of blame exposure on PVV preferences was mediated by blame perceptions, which supports H4.

Discussion

Populist political parties have become influential throughout the world. From India to the Americas to Europe, populism has been successful on both the left and right end of the political spectrum. Many scholars have argued that the media play a pivotal role in the success of populist parties (e.g. Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007; Krämer Citation2014; Mudde Citation2004). Still, we know little about what specific elements of populist messages affect the voting intentions of which citizens (e.g. Jagers and Walgrave Citation2007; Mazzoleni Citation2008). To advance our understanding of the effects of populist messages, we conducted an online survey experiment in which we manipulated the ideational core of populism: the construction of the people as blameless in-group opposed to the culprit elites as out-groups. We found that citizens who are exposed to populist messages that attribute blame to the elites in the national government or the EU are more likely to vote for the right-wing populist Freedom Party PVV. In contrast, populist messages negatively affected people’s propensity to vote for the largest party in government. Populist messages may thus polarize citizens’ political opinions, as exposure to the core populist message makes people less aligned with the government and more aligned with populist challengers. We expected that some citizens are more likely to be affected by populist blame exposure than others. First, we expected the effects to be strongest among the politically cynical (Bos, van der Brug, and de Vreese Citation2013). However, we found no evidence that the politically cynical are most likely to align their party preferences with populist blame exposure. This unexpected finding can be explained by taking a closer look into the data. Comparing populist party preferences between the lower and higher cynical, we found that the politically cynical are more than twice as likely to cast their vote on the populist Freedom Party compared to the lower politically cynical. As they already aligned their vote choice with the belief that the government and the EU are responsible for causing the heartland’s problems, the politically cynical may not need the media to persuade them.

Our results indicate that the negative effect of populist blame exposure on governmental party preferences is strongest among the politically cynical. This corroborates extant research demonstrating that politically cynical citizens hold negative prior attitudes towards political parties in government (e.g. Belanger and Aarts Citation2006). For these citizens, the populist message confirmed their priors, leading to attitudinally congruent persuasion (Stroud Citation2008).

We also expected that populist messages would affect especially those citizens with an exclusionist perception of social identity. Our findings partially supported this expectation. People who feel attached to the nation-state, the imagined community of the populist heartland (Taggart Citation2004), are most likely to vote for a right-wing populist party when exposed to populist messages that frame blame. Attachment to European identity negatively affected the relationship between exposure to populist messages and populist party preferences. These findings are in line with previous research arguing that citizens with a stronger attachment to the nation feel most threatened by the out-groups that populist rhetoric constructs as enemies (e.g. Mudde Citation2004). Citizens with an exclusive perception of social identity may thus feel attracted to right-wing populist parties as they promise to revive the national identity while blaming the government, the EU and immigrants for causing the cultural, social and economic threats of the heartland at crisis (Mols and Jetten Citation2014).

In light of the “populist zeitgeist” rationale (Mudde Citation2004), our results indicate that populist messages have a positive effect on populist voting and a negative effect on vote intentions for the largest party in government. Populist messages do not have an impact on party preferences beyond the scapegoated national government or the populist challenger.

In the context of national-EU multilevel governance, citizens may not always know who is responsible for causing political problems (e.g. Cutler Citation2004). Therefore, exposure to attributions of responsibility is an important cue when citizens form their own perceptions of blame. Building on this process, this paper explored how the effects of populist blame attributions were mediated by perceptions of blame. In line with our expectations, we found that blame cues first needed to be accepted by citizens in order to influence voting preferences, which is in line with previous research that studied the relationship between blame perceptions and vote choice (e.g. Marsh and Tilley Citation2010). The mediating role of blame perceptions can be understood as an effect of negative stereotyping (e.g. Dixon Citation2008; Hewstone Citation1989). Blame exposure activates negative stereotypes about the establishment. These negative evaluations are used to hold the government accountable at the elections, which is again in line with research on responsibility attributions (e.g. Hood Citation2007).

This study has some potential shortcomings. First, media populism may entail more than constructing culprit out-groups of the establishment opposed to a blameless in-group of the national people. Our manipulation of populist blame exposure excluded multiple optional features of populist communication, such as centrality of charismatic leadership, personalization and dramatization. Moreover, we did not assess the effects of blame attribution to right-wing populism’s most salient out-group: immigrants. Incorporating these characteristics could have impacted on our findings. However, we have found effects on populist party preferences simply by manipulating the core of populist rhetoric. Incorporating additional features of populism may augment the effects.

Another shortcoming is our focus on one single country-dependent context. We only assessed how the preference for a Dutch right-wing populist party was affected by, technically, anti-establishment populism. Preferences for left-wing populist parties or populist parties outside of Europe may be affected in different ways. Still, we believe that populism’s ideational core is similar across contexts. Populist rhetoric across countries and across the left-right spectrum is rooted in the binary opposition between the pure people and the culprit others (Mudde Citation2004).

Despite these limitations, this study has advanced the understanding of how populist communication may affect citizens’ party preferences in important ways. Although many questions remain to be answered in future research, we are one step closer in understanding the role of the media in explaining populisms’ electoral success.

JEPOP-2016-0107.R2_Online_appendix.docx

Download MS Word (192.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Michael Hameleers is Assistant Professor in Political Communication at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR) at the University of Amsterdam. His research interests include: framing, misinformation, polarization, media populism and the role of identity in media effects.

Linda Bos is Assistant Professor in Political Communication at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR) at the University of Amsterdam. Her research interests include: electoral behavior, quantitative research methods, (right-wing) populism and political communication.

Claes de Vreese is Professor and Chair of Political Communication and Program Group Director of Political Communication & Journalism at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), Department of Communication Science, University of Amsterdam. He is Adjunct Professor of Political Science and Journalism at the University of Southern Denmark. His research interests include: comparative journalism research, the effects of news, public opinion and European integration.

Notes

1 The experiment contained another factor that was omitted in this study: the emotional style, which was manipulated into anger and fear. We controlled for this factor in all analyses. We report on the outcome of this factor in Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese (Citation2017). As robustness check, we compared the effects of blame attribution for both emotional styles separately. The effects pointed in the same, hypothesized, direction. Overall, the effects for fear where stronger than the effects for anger, which supports the findings presented in Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese (Citation2017).

2 We excluded the Socialist Party (SP) because extant literature has not reached consensus whether this party is actually populist.

3 The other governmental party, PvdA, is not included because it has a smaller share in government than the VVD. Moreover, the VVD supplied the prime-minister, which makes this party most visible as the government.

4 For the interaction plots, the threshold value for higher cynicism was set at 4.01. Analyses with alternative recoding yielded similar results.

5 For the interaction plots, the threshold value for higher attachment was also set at 4.01. Analyses with alternative recoding yielded similar results.

6 The test of the control variables revealed no significant differences between conditions. Age (χ2(384) = 372.97, p = n.s.), gender (χ2(6) = 2.77, p = n.s.), education (χ2(12) = 12.70, p = n.s.), political efficacy EU (χ2(36) = 39.02, p = n.s.), Dutch political efficacy (χ2(36) = 47.65, p = n.s.), previous vote (χ2(30) = 29.94, p = n.s.), attitudes towards the labour market (χ2(36) = 42.06 p = n.s.), and exposure to the news (χ2(42) = 35.79, p = n.s.).

References

- Albertazzi, D., and D. McDonnell. 2008. “Introduction: The Scepter and the Spectre.” In Twenty-first Century Populism. The Spectre of Western European Democracy, edited by D. Albertazzi and D. McDonnell, 1–11. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Belanger, E., and K. Aarts. 2006. “Explaining the Rise of the LPF: Issues, Discontent, and the 2002 Dutch Election.” Acta Politica 41: 4–20. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500135

- Bellucci, P. 2014. “The Political Consequences of Blame Attribution for the Economic Crisis in the 2013 National Election.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 24 (2): 243–263. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2014.887720

- Boomgaarden, H. G., and R. Vliegenthart. 2007. “Explaining the Rise of Anti-immigrant Parties: The Role of News Media Content.” Electoral Studies 26: 404–417. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2006.10.018

- Bos, L., and W. van der Brug. 2010. “Public Images of Leaders of Anti-immigration Parties: Perceptions of Legitimacy and Effectiveness.” Party Politics 16 (6): 777–799. doi: 10.1177/1354068809346004

- Bos, L., W. van der Brug, and C. H. de Vreese. 2011. “How the Media Shape Perceptions of Right-Wing Populist Leaders.” Political Communication 28 (2): 182–206. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2011.564605

- Bos, L., W. van der Brug, and C. H. de Vreese. 2013. “An Experimental Test of the Impact of Style and Rhetoric on the Perception of Right-wing Populist and Mainstream Party Leaders.” Acta Politica 48 (2): 192–208. doi: 10.1057/ap.2012.27

- Brewer, W. F., and G. V. Nakamura. 1984. The Nature and Functions of Schemas, Center for the Study of Reading Technical Report No. 325. Champaign: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Caiani, M., and D. della Porta. 2011. “The Elitist Populism of the Extreme Right: A Frame Analysis of Extreme Right-wing Discourses in Italy and Germany.” Acta Politica 46 (2): 180–202. doi: 10.1057/ap.2010.28

- Canovan, M. 1999. “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47: 2–16. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Carey, S. 2002. “Undivided Loyalties: Is National Identity an Obstacle to European Integration?” European Union Politics 3: 387–413. doi: 10.1177/1465116502003004001

- Cutler, F. 2004. “Government Responsibility and Electoral Accountability in Federations.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 34 (2): 19–38. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a005028

- Dixon, T. L. 2008. “Crime News and Racialized Beliefs: Understanding the Relationship Between Local News Viewing and Perceptions of African Americans and Crime.” Journal of Communication 58: 106–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00376.x

- Entman, R. M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Hameleers, M., L. Bos, and C. H. de Vreese. 2017. “‘They Did It’: The Effects of Emotionalized Blame Attribution in Populist Communication.” Communication Research 44 (6): 870–900. doi: 10.1177/0093650216644026

- Hewstone, M. 1989. Causal Attribution: From Cognitive Processes to Collective Beliefs. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hobolt, S. B., J. Tilley, and J. Wittrock. 2013. “Listening to the Government: How Information Shapes Responsibility Attributions.” Political Behavior 35 (1): 153–174. doi: 10.1007/s11109-011-9183-8

- Hood, C. 2007. “What Happens When Transparency Meets Blame-avoidance?” Public Management Review 9 (2): 191–210. doi: 10.1080/14719030701340275

- Iyengar, S. 1991. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Jagers, J., and S. Walgrave. 2007. “Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium.” European Journal of Political Research 46 (3): 319–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00690.x

- Krämer, B. 2014. “Media Populism: A Conceptual Clarification and Some Theses on its Effects.” Communication Theory 24: 42–60. doi: 10.1111/comt.12029

- Marsh, M., and J. Tilley. 2010. “The Attribution of Credit and Blame to Governments and Its Impact on Vote Choice.” British Journal of Political Science 40 (1): 115–134. doi: 10.1017/S0007123409990275

- Mazzoleni, G. 2008. “Populism and the Media.” In Twenty-first Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy, edited by D. Albertazzi and D. McDonnell, 49–64. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mols, F., and J. Jetten. 2014. “No Guts, No Glory: How Framing the Collective Past Paves the Way for Anti-immigrant Sentiments.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 43: 74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.08.014

- Mudde, C. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39: 542–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Rooduijn, M. 2014. “The Mesmerising Message: The Diffusion of Populism in Public Debates in Western European Media.” Political Studies 62 (4): 726–744. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12074

- Stroud, N. J. 2008. “Media Use and Political Predispositions: Revisiting the Concept of Selective Exposure.” Political Behavior 30: 341–366. doi: 10.1007/s11109-007-9050-9

- Taggart, P. 2004. “Populism and Representative Politics in Contemporary Europe.” Journal of Political Ideologies 9 (3): 269–288. doi: 10.1080/1356931042000263528

- Tingley, D., T. Yamamoto, K. Hirose, L. Keele, and K. Imai. 2014. “Mediation: R Package for Causal Mediation Analysis.” Journal of Statistical Software 59 (5): 1–38. doi: 10.18637/jss.v059.i05

- Van Kessel, S. 2011. “Explaining the Electoral Performance of Populist Parties: The Netherlands as a Case Study.” Perspectives on European Politics and Society 12 (1): 68–88. doi: 10.1080/15705854.2011.546148

- Vasilopoulou, S., D. Halikiopoulou, and T. Exadaktylos. 2013. “Greece in Crisis: Austerity, Populism and the Politics of Blame.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (2): 388–402.

- Ziller, C., and T. Schübel. 2015. “‘The Pure People’ Versus ‘the Corrupt Elite’? Political Corruption, Political Trust and the Success of Radical Right Parties in Europe.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 25 (3): 368–386. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2014.1002792