?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Political conflict is often described in terms of “left” and “right” even though societal conflicts stem from various sub-dimensions such as economic and cultural issues. We argue that individuals map parties’ left-right positions based on party positions on such underlying dimensions, though their impact depends on their importance for parties and citizens. To test this, we study the German Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) whose programmatic appeal has changed fundamentally in the last years, as have citizens’ issue concerns. Using longitudinal data from the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES), we find that citizens’ perceptions of the AfD’s left-right position are more closely related to the party’s position on specific issues (1) when these issues are prominent in the party’s communication and (2) for citizens that care more about these issues. Moreover, how voters perceive left and right in comparison to parties’ issue emphasis also affects vote choice. Our findings have important implications for the meaning of left and right, electoral behaviour, representation, and party competition.

Introduction

The left-right dimension is one of the most convenient and widely-used heuristics in politics. Parties employ the language of left and right to communicate their positions to voters, and citizens use left-right positions to situate themselves and parties in order to determine who best represents their preferences and concerns. In most developed democracies, the vast majority of citizens are able and willing to locate themselves and parties on this dimension (e.g. Mair Citation2007; Dalton, McAllister, and Farrell Citation2011, ch. 4 & 5). Part of the reason for the persistence of the language of “left” and “right” might be due to its flexibility: the left-right dimension serves as a “super issue” (Inglehart and Klingemann Citation1976, 244) and an “amorphous vessel” (Huber and Inglehart Citation1995, 90) with little inherent substantive meaning. The meaning of “left” and “right” is not predetermined, and varies empirically between individual citizens, in different contexts, and over time (Zechmeister Citation2006; de Vries, Hakhverdian, and Lancee Citation2013; Bauer et al. Citation2016).

Compared to understanding voters’ ideological self-positioning, far less attention has been paid to the way in which citizens identify the positions of parties on the left-right dimension. Existing research has focused on the capability and willingness of respondents to locate parties in policy spaces (e.g. Dahlberg Citation2009, 2013; Busch Citation2016), on the accuracy of these perceived party policy positions (Merrill, Grofman, and Adams Citation2001; Barabas and Jerit Citation2009; Lenz Citation2012; Banducci, Giebler, and Kritzinger Citation2017; Merz Citation2017; Carroll and Kubo Citation2018), and how citizens update their perceptions of party policy positions (Adams, Ezrow, and Somer-Topcu Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2016; Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013; Fernandez-Vazquez Citation2014; Fortunato and Adams Citation2015; Seeberg, Slothuus, and Stubager Citation2016; Plescia and Staniek Citation2017). Yet, relatively little is known about how citizens map party policies, issues, and frames onto party positions on the left-right dimension despite the crucial role of this dimension for aspects like voting or political representation.

In this paper, we argue that individuals infer parties’ overall left-right stances from party positions on ideological sub-dimensions linked to economic and cultural issues. However, the degree to which these sub-dimensions impact on the perceived left-right positions of parties depends on the importance of these sub-dimensions to parties as well as to individuals. We argue that citizens tend to map left-right party stances from those ideological sub-dimensions that (1) are more prominent on the party’s issue agenda and (2) more important to the individuals themselves. This also implies that perceptions of party stances will change over time when the party’s issue emphasis changes and when citizens perceive different topics as most important to them, even if the underlying party positions remain the same.

We test these arguments using public perceptions of the German Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) since its emergence in 2013. The AfD is an important case because voter perceptions of its left-right position differ substantially across respondents and have evolved over time. Thus, there is considerable variation in the dependent variable. Moreover, both the party’s programmatic appeal and public issue concerns have changed fundamentally since the party’s emergence, so we can use this case to investigate the impact of demand- and supply-side factors on public perceptions of party positions. The focus on one case and a rather short period of time also has the advantage that many context factors related to the institutional context and political culture are held constant and, thus, cannot provide confounding explanations of voters’ perceptions of parties’ left-right positions.

We study changes in perceptions of the AfD’s left-right position using the Long-term Online Tracking of the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES) and find strong evidence that citizens’ perceptions of the AfD’s left-right position have changed significantly since 2013. In placing the party on the left-right dimension, respondents paid more attention to the party’s cultural issues after these issues became more important to the party. Moreover, voters paid more attention to sub-dimensions that they personally regarded as important: if they considered an issue dimension to be salient, then positions on this issue dimension influenced their left-right positioning of the AfD more. These patterns are more pronounced for the cultural issue dimension but clearly driven by supply- and demand-side factors.

Our findings have important implications for several core aspects of electoral behaviour and representative democracy. First, they add to the existing research on the meaning of left and right (Huber and Inglehart Citation1995; Knutsen Citation1995; de Vries, Hakhverdian, and Lancee Citation2013; Bauer et al. Citation2016). We show that the meaning of left and right is indeed flexible and may change over time when (1) parties address different issue areas and when (2) the public’s perception of issue importance changes.

Second, as the meaning of left and right varies with a party’s issue focus and public issue concerns, ideological congruence between parties and their voters on the left-right dimension does not necessarily imply good substantive representation. For example, high levels of left-right congruence may be misleading if the voter’s position is mostly based on preferences on the economy, while the party’s platform is associated with cultural issues (or vice versa). In their influential study on ideological congruence, Golder and Stramski (Citation2010, 93) already acknowledge that “much depends on […] whether the left-right dimension is perceived in the same way across the different units.” This article points to an even bigger issue: the perception of left-right in terms of its substantive meaning does not just vary between countries but also between political parties and citizens in the same unit.

Third, this variation in the meaning of “left” and “right” has implications for vote choice. We show that the left-right dimension is more meaningful for vote choice when voter and party policy positions on that dimension are based on the same substantive issue positions, that is, when their left-right positions stem from similar sub-dimensions.

Finally, our results also have implications for party competition: parties can shift their policy positions on the left-right dimension by putting different emphasis on certain issues (Meyer and Wagner Citation2017). Hence, policy change does not necessarily imply a position change on certain issues and the risks associated with “flip-flopping.” This suggests that there are more subtle, less risky strategies that parties can use in order to shift their policy platform.

The left-right dimension and public perceptions of political parties

Following the seminal work of Downs (Citation1957), politics is understood as based on societal conflicts for which parties advocate different policy solutions. While parties and candidates take stances on many issues, electoral competition can be reduced to a single dimension where a “party’s net position on this [left-right] scale is a weighted average of the positions of all the particular policies [the party] upholds” (Downs Citation1957, 132). It is important to note that this does not imply identical perceptions of these positions by all citizens. Rather, citizens may not agree on a party’s individual stances and may attach different weights to these issues. Therefore, their perceptions of party policy positions might vary (Downs Citation1957, 133).

The distinction between left and right helps citizens by providing a simplified perception of political competition. The left-right heuristic is thus useful because it simplifies thinking and talking about political divisions and conflicts, which are often complex and multidimensional. While issue competition is increasingly important (Green-Pedersen Citation2007), only few citizens develop preferences on many issues, devote the time and energy necessary to learn about parties’ issue positions, and make their choices accordingly. Rather, the left-right distinction is used as a shortcut and a simplified way of comparing one’s own preferences to party policy programmes. References to “left” and “right” are indeed frequently used in the media and public debates to characterize party policy positions and general lines of conflict. In consequence, the vast majority of citizens have the capacity and willingness to locate themselves and political actors on a left-right scale (Inglehart and Klingemann Citation1976; Shikano and Pappi Citation2004; Mair Citation2007).

Yet, the applicability and functional role of the left-right distinction says little about its precise meaning. In his early criticism of Downs, Stokes (Citation1963, 371) questions whether the “fixed structure” assumption of economic models travels to the political context:

Since the space represented by a transcontinental railroad depends on physical distance, its structure is fixed, as the structure of Main Street is. […] By comparison, the space in which political parties compete can be of highly variable structure. Just as the parties may be perceived and evaluated on several dimensions, so the dimensions that are salient to the electorate may change widely over time.

There are at least two important sub-dimensions that feed into the left-right dimension: the economy and cultural (or libertarian-authoritarian) issues.Footnote1 The first sub-dimension refers to policy conflicts of economic inequality, redistribution, and class conflict (e.g. Mair Citation2007). The economic divide has long been the dominant way of distinguishing parties on a left-right dimension (Budge and Robertson Citation1987; Huber and Inglehart Citation1995). However, cultural issues have gained importance in recent decades (Knutsen Citation1995; Green-Pedersen Citation2007; de Vries, Hakhverdian, and Lancee Citation2013; Beramendi et al. Citation2015). The emergence of issues like immigration and gender equality has fundamentally shaped major lines of conflict in societies (see also Inglehart Citation1984, 68f.; Kitschelt Citation1994; Kriesi et al. Citation2008), creating new divisions but also diminishing the structuring effect of traditional cleavages. Consequently, policy positions on both sub-dimensions affect where parties are located on the left-right scale (e.g. Benoit and Laver Citation2006).Footnote2

Despite these important changes, we know relatively little about how citizens map the (perceived) party issue stances on these two key sub-dimensions onto the more general left-right dimension. Most studies on public perceptions of party policy positions analyze whether individuals are capable to locate parties in policy spaces (e.g. Dahlberg Citation2009, Citation2013; Busch Citation2016), under which circumstances perceived party positions represent actual party positions (Barabas and Jerit Citation2009; Lenz Citation2012; Banducci, Giebler, and Kritzinger Citation2017; Merz Citation2017; Carroll and Kubo Citation2018), and how citizens update their perceptions of party policy positions (Adams, Ezrow, and Somer-Topcu Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2016; Fortunato and Stevenson Citation2013; Fernandez-Vazquez Citation2014; Fortunato and Adams Citation2015; Seeberg, Slothuus, and Stubager Citation2016; Plescia and Staniek Citation2017). In contrast, research on the issue dimensions underlying the left-right dimension is relatively scarce. It has been shown that citizens’ personal left-right policy preferences are indeed increasingly associated with their views on cultural issues (de Vries, Hakhverdian, and Lancee Citation2013). However, the concept of representative democracy makes it necessary to focus not only on the demand side but also on (perceptions of) the supply side. In the following, we develop expectations on how individuals map party policy positions onto the left-right dimension acknowledging the relevance of both the supply and demand side. Our focus on both supply- and demand-side factors acknowledges that electoral competition is structured both by top-down and bottom-up factors.

Supply-side influences on parties’ perceived left-right positions

From a supply-side perspective, the issues that parties emphasize should affect the meaning of the labels “left” and “right.” Parties focus on different issues, preferring topics and ideological sub-dimensions where they have a competitive advantage (Budge and Farlie Citation1983). These issues are often at the core of a party’s ideology: classic examples are Green parties and the environment, socialist parties and social welfare, or radical right parties and immigration. Such “issue ownership” (Petrocik Citation1996) might also result from mere association between a party and a particular issue (Walgrave, Lefevere, and Tresch Citation2012), irrespective of a party’s perceived competence in dealing with the particular issue. In addition, parties also adapt their issue emphasis to changes in the environment. For example, they address issues that are prominent on the party system agenda, particularly in response to parties that are ideologically close to them (Green-Pedersen and Mortensen Citation2015; Meyer and Wagner Citation2016).

Overall, we expect that, if a party emphasizes an issue belonging either to the economic or cultural sub-dimension, its left-right position is more likely to be associated with that sub-dimension (see also van der Brug Citation2004). One consequence of this is that two parties with similar perceived left-right positions may nevertheless differ in their policy positions on economic and cultural issues. For example, the “leftism” of Green and socialist parties is fundamentally distinct: They might support “similar policies on preservation of health care benefits, but this is a presumably more important issue to the Social Democrats and thus is more influential in determining their overall political identity” (Dalton, McAllister, and Farrell Citation2011, 124). In addition to these cross-party differences, changing issue emphasis should also alter a party’s perceived policy position over time. Thus, parties can change their (perceived) party policy positions by giving more weight to certain issues (e.g. van der Brug Citation2004; Meyer and Wagner Citation2017).

Following these arguments, we hypothesize:

H1 (party issue agenda): The more important an issue is on a party’s issue agenda, the more the party’s perceived position on that issue influences the party’s perceived position on the left-right dimension.

Demand-side influences on parties’ perceived left-right positions

So far we have considered how parties influence the perception of their own left-right position. In contrast, a demand-side perspective focuses on citizens’ issue concerns. Assessing these public issue concerns in the underlying framework can be understood as a mirror approach to the supply-side discussion. As parties’ perceived left-right positions become more strongly associated with positions regarding issues high on the party’s agenda, we argue that the importance citizens ascribed to the different issue dimensions matters as well.

Respondents differ in the issues they deem to be important (personal issue emphasis). Hence, it could be that respondents, when thinking about a party’s left-right position, take that party’s position on an issue of a specific sub-dimension more into account if they care more about that sub-dimension. Conversely, they would not map party positions from sub-dimensions that are not salient to them personally. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H2 (personal issue emphasis): The more salient an issue is to an individual, the more the party’s perceived position on that issue influences the party’s perceived position on the left-right scale.

Case selection: the Alternative für Deutschland 2013–2016

We test our hypotheses based on voter perceptions of the German Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) between 2013 and 2016. As such, even though our argumentation is applicable to all contexts in which left-right matters, we only present results from a single case study and for a rather limited period of time. While this places relevant limits on the generalizability of our findings, focusing on this specific party and a rather short time period has also several very important advantages over alternative research designs. First, in contrast to cross-sectional analyses, a longitudinal design has the advantage that many institutional, cultural, and historical context factors can be taken as stable and, thus, cannot figure as confounders causing variation in voter perceptions of party left-right positions.

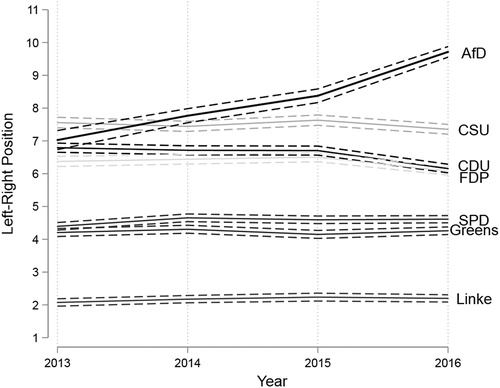

Second, there is substantive variation in the dependent variable, both across respondents and over time. Obviously, both aspects are necessary conditions to identify any supply- or demand-side effects. The left-right dimension is highly relevant for describing party competition in Germany. Interestingly, voter perceptions of the AfD’s policy position have changed substantially since the party emerged in 2013. shows means of the respondents’ perceived party policy positions between 2013 and 2016. While the other German parties’ perceived left-right positions change moderately at most, the AfD’s position shifts from a centrist position to a very right-wing position (roughly three points on the 11-point scale). This change in perceptions might be due to the increasing demand- and supply-side importance of cultural issues, where the AfD is particularly right-wing.

Figure 1. German citizens’ perceptions of party left-right positions (means).

Note: German Longitudinal Election Study, Rattinger et al. (Citation2015a, Citation2015b) and Roßteutscher et al. (Citation2016). Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals for the mean perceived party positions. AfD, Alternative for Germany; CDU, Christian Democratic Union; CSU, Christian Social Union; FDP, Free Democratic Party; Greens, Alliance 90/The Greens; Linke, The Left; and SPD, Social Democratic Party of Germany.

Third, there has been substantial variation in demand- and supply-side factors of party competition since 2013. With regard to the demand side, public issue concerns not only vary across individuals but also changed substantially between 2013 (when the economic crisis still played a large role in the political debate) and 2016 (when the so-called “refugee crisis” increased the attention to cultural issue concerns).

With regard to the supply side, the AfD substantially shifted its issue agenda within a relatively short period. When it was founded in 2013, the AfD mostly focused on economic issues, especially to those related to the Euro and the management of the (Greek) debt crisis. Led by Bernd Lucke, a professor of economics, the party opposed any financial aid to foreign countries during the crisis, criticized established political elites, and campaigned against the Euro and in favour of direct democracy, national sovereignty as well as neo-liberalism. While some observers argue that some aspects of the AfD in 2013 already showed radical-right tendencies, especially the electoral candidates it put forward (Lewandowsky, Giebler, and Wagner Citation2016), the party’s programmatic orientation was harder to characterize (Franzmann Citation2014).

This changed dramatically when Lucke left the party in June 2015 due to internal conflict. Some high-ranking party officials were no longer satisfied with the party’s course, and within a few months, partly fostered by the so-called “refugee crisis”, the party changed its focus to cultural issues and intensified its critique of political elites, science, and the media. The AfD provides an ideal case for testing our first hypothesis on supply-side effects because the parties’ issue agenda changed dramatically in only a couple of months.

Fourth, in terms of data, the Long-term Online Tracking of the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES) is particularly well-suited to answering our research question (Rattinger et al. Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Roßteutscher et al. Citation2016). In contrast to most cross-national surveys, these annual cross-sectional surveys conducted between 2013 and 2016 contain questions on party placements on economic and cultural issues along with those on a left-right scale. The time span between surveys is relatively short, so certain contextual factors can be assumed to be fixed. Furthermore, the sampling strategy and the questionnaires are identical in all four surveys.

Translating our hypotheses to the case of the AfD, we can formulate the following expectations: first, the more important cultural topics became in the AfD’s programmatic orientation, the more voters based their perceptions of the AfD’s left-right position on its perceived position on the cultural sub-dimension. Vice versa, voters based their perceptions of the AfD’s left-right position less on its perceived position on the economic dimension after the party’s programmatic shift in 2015 (H1). Second, the extent to which respondents map the AfD’s policy position on the left-right dimension to its cultural or economic issues stances depends on how important the respective sub-dimension is to the respondent (H2).

Data and methods

The dependent variable in our analysis is a respondent’s perception of the AfD’s policy position on a left-right scale. The key independent variables are the perceived party issue positions on redistribution (economic sub-dimension) and migration (cultural sub-dimension). All three variables are measured on an eleven-point scale.Footnote3 Unfortunately, many respondents could not locate the AfD on all (sub-)dimensions (see Appendix B). To avoid listwise deletion, we use hot deck imputation as a rather conservative approach of dealing with this issue (Andridge and Little Citation2010).Footnote4

To measure changes in the party issue agenda (Hypothesis 1), we rely on content analyses of party press releases from 2013 to 2016 (N = 1,311). Party press releases constitute an ideal basis for measuring a party’s issue agenda between elections. Unlike manifestos, they are published continuously. Moreover, they are freely available and directed towards journalists and a wider public. Following previous research (Klüver and Sagarzazu Citation2016; Sagarzazu and Klüver Citation2017), we use the expressed agenda model developed by Grimmer (Citation2010) to classify party press releases into issue clusters. This unsupervised model technique creates topics of words that cluster together (e.g. “euro”, “ecb”, and “bank”) and assigns press releases to those topics that fit best. We then derive word stems (i.e. words without affixes) that serve as input for the analysis and remove those that are used in less than 1% of all documents. The number of issue categories (or “topics”) is not determined by the model. Following previous research (e.g. Grimmer and Stewart Citation2013; Klüver and Sagarzazu Citation2016; Sagarzazu and Klüver Citation2017), we therefore estimate the model for a varying number of those categories (from 7 to 17) and chose the model with the most meaningful and distinct issue categories. We then cluster issues related to economic or cultural issues to measure the salience of both issue dimensions. Issues at the European level related to monetary policy (e.g. Greece, “Euro” as currency) are coded as economic issues.Footnote5 Additional information on the topic model and validity checks are outlined in Appendix E. To match the party’s issue agenda with the survey data, we only use the press releases published in the four months prior to the field time.Footnote6

To measure personal issue emphasis (Hypothesis 2), we use the “most important” and “second-most important” problems identified by the respondents. We rely on the GLES coding scheme of responses and identify issues related to socio-economic and socio-cultural issues. For each respondent, we calculate the share of responses that refer to economic and cultural issues, respectively.

In addition, we include several control variables: To capture assimilation and contrast effects in the respondents’ perceptions of party policy positions (e.g. Merrill, Grofman, and Adams Citation2001), we include an interaction of the respondents’ own policy preferences and their sympathy towards the AfD (11-point scale). Because respondents tend to mix issue importance and issue positions when answering survey items (e.g. Wagner and Zeglovits Citation2014), personal issue emphasis might also indicate more extreme issue preferences. To account for personal issue extremism, we use the respondents’ personal policy preferences (also measured on an 11-point scale) on economic and cultural issues along with their squared terms.Footnote7 Moreover, we control for education (low/medium/high), sex, age (in years), subjective class (blue collar, lower middle, middle, and upper class), and whether the respondent lives in East or West Germany to capture any remaining variation in respondents’ perceptions of the AfD’s left-right position.

We use a censored regression model (Tobit model) with standard errors clustered by years to explain respondents’ perceptions of the AfD’s policy position on the 11-point left-right scale. In contrast to an ordinary least squares regression, this model accounts for the fact that responses are constrained to an 11-point scale. This is particularly relevant for the AfD, as about 30% of respondents locate the party at the right end of the scale (11). The censored regression model accounts for upper and lower limits, but is otherwise identical to a linear regression model for values that fall between the two extremes.

If denotes respondent i’s true (latent) perception of the AfD’s policy position, then

denotes the chosen (perceived) policy position on the 11-point left right scale. We can model public perceptions of the AfD’s left-right position

based on its (perceived) positions on economic and cultural issues.

Explaining voter perceptions of party policy positions on the left-right scale

Are perceptions of the AfD’s left-right position shaped by supply-side, demand-side factors, or both? shows the regression results. Since we test hypotheses referring to conditional effects, however, we present the main findings using graphs.Footnote8

Table 1. Explaining voter perceptions of the AfD’s policy position on the left-right scale.

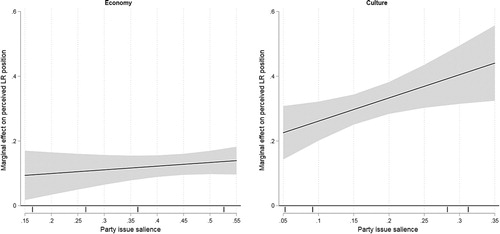

shows the marginal effect of the economic (left panel) and the cultural sub-dimension (right panel) for varying levels of party issue importance (Hypothesis 1). In the left panel, there is no significant evidence that party issue attention to the economy affects how much attention respondents put on its economic issue position when evaluating the AfD on the left-right scale. While the marginal effect increases with growing party issue attention (as expected), the increase is small and statistically insignificant. However, we do find evidence that respondents align the AfD’s left-right position with its position on cultural issues when the party addresses these issues to a greater extent. The party’s emphasis on these issues increased steadily from about 5% (2013) to 9% (2014) to roughly 28 and 31% in 2015 and 2016, respectively. In 2013, when the AfD’s emphasis on cultural issues was rather low, shifting the AfD’s perceived cultural position by one unit to the right corresponds with a rightward shift of 0.23 units of the perceived policy position on the left-right dimension. This effect becomes about twice as large (0.44) in 2016, after the party focused on cultural issues. This finding is in line with Hypothesis 1.

Figure 2. Supply-side effects on issue mapping, party issue emphasis (H1).

Note: Solid lines show the marginal effect of the economic (left panel) and the cultural issue position (right panel) depending on the attention to these issues in the party’s press releases (x-axis). The vertical bars denote the empirical values in party issue emphasis for both sub-dimensions. Shaded areas denote 95% confidence intervals. All estimates based on the Tobit model shown in Table 1.

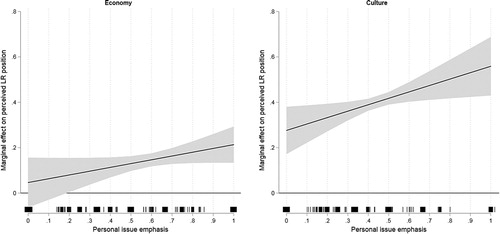

Turning to the demand side, gives information on our test of Hypothesis 2. We indeed find evidence that personal issue emphasis structures the relationship of the two issue dimensions and the left-right position: The more citizens care about issues related to economic (left panel) or cultural issues (right panel), the stronger the association of that issue dimension with the perceived left-right position of the AfD. Yet, the slope for economic issues is relatively flat and the effect is not robust across different model specifications (see Appendix C).

Figure 3. Demand-side effects on issue mapping, personal issue emphasis (H2).

Note: Solid lines show the marginal effect of the economic (left panel) and the cultural issue position (right panel) depending on the respondents’ issue emphasis (x-axis). The vertical bars denote the empirical values in personal issue emphasis for both sub-dimensions (small jitter added). Shaded areas denote 95% confidence intervals. All estimates based on the Tobit model shown in Table 1.

In contrast, the moderating effect on the cultural issue dimension is substantialy stronger: for citizens who think socio-cultural issues are not among the most important concerns, a one unit change (to the right) on cultural issues corresponds with a 0.28 unit change (to the right) of the AfD’s perceived left-right position. For citizens who identify only socio-cultural issues as the most important ones, the correspondance between a one-unit change to the right on the socio-cultural dimention and the perceived polition on the left-right dimension is again about twice as large (0.58).Footnote9

Implications for vote choice

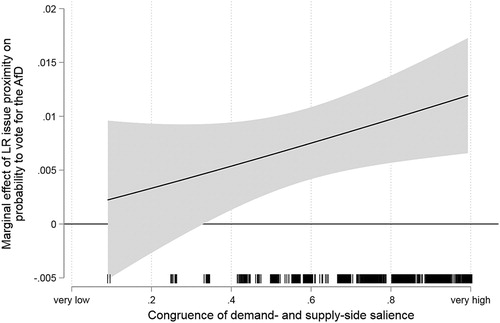

Finally, we turn to an important implication of our findings for political behaviour. If left-right placements of parties and voters may stem from different underlying issue dimensions, party-voter proximity on the left-right dimension might affect political behaviour only if a voter’s and a party’s mappings are identical. We study this question by considering the effect of left-right proximity between individuals and parties as a predictor of vote choice. We expect that the effect of party-voter proximity on vote choice should increase if the voter’s and the party’s left-right positions are based on the same underlying issue dimensions.

We estimated a vote intention model for the AfD, controlling for party sympathy, education, sex, age, subjective class, and whether the respondent lives in East or West Germany. Our key predictor is an interaction between left-right proximity and the congruence of demand- and supply-side salience.Footnote10 The latter runs from 0 (very low congruence) to 1 (very high congruence) and compares the relative salience of both sub-dimensions between an individual and the party.

underlines the relevance of our theoretical arguments and approach: Left-right proximity to the AfD is only relevant for citizens if salience congruence is reasonably high. The positive moderating effect of congruence depicted in can be further substantiated: the effect of left-right proximity on vote choice is about twice as large for respondents in full correspondence with the party’s issue agenda compared to those with a medium level of issue agreement (0.5). Clearly, our approach to explaining perceived party positions matters also in terms of electoral behaviour.

Figure 4. Conditioning effect of salience congruence on left-right proximity for AfD vote intention.

Note: Solid lines show the marginal effect of the left-right proximity depending on the congruence of demand- and supply-side salience (x-axis). The vertical bars denote the empirical values in congruence (small jitter added). Shaded areas denote 95% confidence intervals. All estimates based on the logit model shown in Appendix G.

Conclusion

In this paper, we proposed a supply- and demand-side perspective on when and how the substantive meaning of party positions on the left-right dimension changes. We argued that individuals map party issue positions on the general left-right scale from cultural and economic sub-dimensions. Moreover, the importance of each issue sub-dimension depends both on a party’s issue agenda (supply side) and the citizens’ issue concerns (demand side). We tested these arguments looking at perceptions of the AfD and we find that the party’s stronger focus on cultural issues in its public agenda from 2015 onwards had a strong impact on how respondents map the party on the left-right dimension. Due to the AfD's changed issue agenda the cultural sub-dimension became much more important in how citizens place the party on the left-right dimension. Citizens who deemed cultural issues to be important also give more weight to the AfD’s stances on cultural issues in thinking about the party’s left-right position.

These findings suggest that the meaning of the left-right dimension as the major line of conflict can indeed change over time (e.g. de Vries, Hakhverdian, and Lancee Citation2013) and that these changes can be the result of supply- and demand-side factors. Perceptions of party policy positions on the left-right dimension might thus result from changes in issue emphasis, even if the parties’ actual policy positions on economic or cultural issues stay the same.

With regard to vote choice and substantive representation, our findings point to the pitfalls of the “amorphous” (Huber and Inglehart Citation1995, 90) character of the left-right dimension: voter-party proximity on the left-right dimension is only meaningful if voters and parties have a similar understanding of left and right. The flipside of our argument is that parties can actually shift their positions on the left-right dimension in two ways: by actually changing their policy positions on issue dimensions (such as the economy) or by a more subtle, less risky strategy of changing their emphasis on certain issues (Meyer and Wagner Citation2017).

There are several avenues to extend this analysis. First, there is obviously a necessity to move beyond the single case of the AfD and to study changes in perceived party left-right positions cross-nationally. Despite current limitations in terms of data availability, similar analyses might be feasible in different countries. Without further analysis, we cannot be sure whether our findings also hold for other parties or in different contexts. The AfD could be considered as a special case to observe changes in voter perceptions, as these changes might be most pronounced for rather new parties that also focus on non-economic issues.

Second, it would be interesting to extend this analysis to study how the party system (e.g. Green-Pedersen and Mortensen Citation2015; Meyer and Wagner Citation2018) and the media agenda (e.g. McCombs Citation2004) affect perceptions of party left-right positions. In the present analysis, these effects are subsumed in a party’s issue attention that is subject to change in the party system (e.g. Green-Pedersen and Mortensen Citation2015) and a cause for changes in the media agenda (e.g. Brandenburg Citation2002). Yet, both the party system and the media agenda may have independent effects in how individuals think about current problems and evaluate parties on the left-right scale.

Finally, we could also think of other issues and issue dimensions where “mapping” from lower-level issues to a higher level might be relevant. For example, a party’s position on cultural issues represents a summary statement of its policy positions on gender issues, law and order policy, and immigration. Similar to the argument presented above, a party’s (perceived) policy position on the cultural issue dimension might shift to the left (or right) when individual policies where parties hold liberal (or conservative) positions gain importance. Overall, left-right thinking and discourse appears to remain important, even if the content of that dimension has (been) shifted over time.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.2 MB)Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2017 BGSS Research Working Group on Political Parties and Electoral Competition Meeting in Berlin, the 2017 MPSA Annual Conference, the 2017 EPSA Annual Conference, and the “New Developments in Spatial Models of Party Competition” Workshop at the University of Konstanz. We thank all participants and panelists for valuable comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers as well as the editors for their insightful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Heiko Giebler

Heiko Giebler is Research Fellow and Head of the Bridging Project “Against Elites, Against Outsiders: Sources of Democracy Critique, Immigration Critique, and Right-Wing Populism” (DIR) at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center in the Department “Democracy & Democratization”. His main research interests are political behavior, electoral campaigns, and populism.

Thomas M. Meyer

Thomas M. Meyer is Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. He works mainly on parties, their messaging, electoral competition and coalition governance.

Markus Wagner

Markus Wagner is Professor of Political Science at the Department of Government, University of Vienna. His research looks mainly at political parties and electoral behavior, with a particular focus on the role of issues and ideology for how parties compete and how voters decide.

Notes

1 The complex topic of the EU is linked to both the economic and the cultural issue dimensions (e.g., Kriesi et al. 2008). In an additional analysis (Appendix D, Model 2), we also account for European integration as a third issue dimension. The results of this model lead to similar conclusions regarding our hypotheses.

2 The question whether policy positions on both sub-dimensions are correlated is not crucial for our argument, at least if policy positions differ somewhat across the sub-dimensions. For example, a party with a moderate stance on economic issues and a more radical position on cultural issues can be perceived as more extreme if emphasizes its cultural issue stance more.

3 Information on question wording and scaling can be found in Appendix A.

4 Four indicators are used for the imputation process: the three aforementioned perceived party positions and the perceived party position on the EU integration issue. Appendix C shows the regression results based on the samples with and without imputation. The results in both analyses are very similar and lead to identical conclusions.

5 Including European integration as a third issue dimension into our analysis does not alter our main conclusions (see Appendix D).

6 As we have four survey waves, this variable only varies across issue dimensions and years. In an additional analysis (shown in Appendix F), we report the results of a macro-level analysis with mean perceived party policy positions. Although based on a small number of observations, the results are in line with those reported in this manuscript.

7 As shown in Model 3 in Appendix D, excluding this control variable does not alter the conclusions regarding our hypotheses.

8 For the estimation of the linear predictions, all independent variables (including binary indicators) are set to their empirically observed values.

9 We find similar, although substantially weaker, effects of personal issue emphasis using a pooled sample with seven German parties (CDU, CSU, FDP, Greens, SPD and The Left in addition to the AfD) for the period under research (Appendix H). Appendix H also presents additional party-specific models. Results indicate that we find the most support for parties with heterogeneous position, e.g., economically left and culturally right positions – or, the other way around. This is especially the case for the AfD and the FDP – and to a weaker degree for the Greens.

10 Appendix G provides detailed information of how the congruence measure was constructed as well as a table representing the regression results. We run a logistic model explaining vote intention for the AfD in comparison to voting for any other party.

References

- Adams, James, Lawrence Ezrow, and Zeynep Somer-Topcu. 2011. “Is Anybody Listening? Evidence that Voters do not Respond to European Parties’ Policy Statements During Elections.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (2): 370–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00489.x

- Adams, James, Lawrence Ezrow, and Zeynep Somer-Topcu. 2014. “Do Voters Respond to Party Manifestos or to a Wider Information Environment? An Analysis of Mass-Elite Linkages on European Integration.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (4): 967–978. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12115

- Adams, James, Lawrence Ezrow, and Christopher Wlezien. 2016. “The Company You Keep: How Voters Infer Party Positions on European Integration from Governing Coalition Arrangements.” American Journal of Political Science 60 (4): 811–823. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12231

- Andridge, Rebecca R., and Roderick J. A. Little. 2010. “A Review of Hot Deck Imputation for Survey Non-Response.” International Statistical Review 78 (1): 40–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-5823.2010.00103.x

- Banducci, Susan, Heiko Giebler, and Sylvia Kritzinger. 2017. “Knowing More from Less: How the Information Environment Increases Knowledge of Party Positions.” British Journal of Political Science 47 (3): 571–588. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000204

- Barabas, Jason, and Jennifer Jerit. 2009. “Estimating the Causal Effects of Media Coverage on Policy-Specific Knowledge.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (1): 73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00358.x

- Bauer, Paul C., Pablo Barberá, Kathrin Ackermann, and Aaron Venetz. 2016. “Is the Left-Right Scale a Valid Measure of Ideology? Individual-Level Variation in Associations with ‘Left’ and ‘Right’ and Left-Right Self-Placement.” Political Behavior, First Online.

- Benoit, Kenneth, and Michael Laver. 2006. Party Policy in Modern Democracies. London: Routledge.

- Beramendi, Pablo, Silja Häusermann, Herbert Kitschelt, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. 2015. The Politics of Advanced Capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brandenburg, Heinz. 2002. “Who Follows Whom? The Impact of Parties on Media Agenda Formation in the 1997 British General Election Campaign.” Harvard International Journal of Press-Politics 7 (3): 34–54.

- Budge, Ian, and Dennis J. Farlie. 1983. Explaining and Predicting Elections: Issue Effects and Party Strategies in Twenty-Three Democracies. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Budge, Ian, and David Robertson. 1987. “Do Parties Differ, and How? Comparative Discriminant Analysis and Factor Analyses.” In Ideology, Strategy and Party Change: Spatial Analyses of Post-war Election Programmes in 19 Democracies, edited by Ian Budge, David Robertson, and Derek Hearl, 387–416. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Busch, Kathrin B. 2016. “Estimating Parties’ Left-Right Positions: Determinants of Voters’ Perceptions’ Proximity to Party Ideology.” Electoral Studies 41: 159–178. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2016.01.003

- Carroll, Royce, and Hiroki Kubo. 2018. “Explaining Citizen Perceptions of Party Ideological Positions: The Mediating Role of Political Contexts.” Electoral Studies 51: 14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2017.11.001

- Dahlberg, Stefan. 2009. “Political Parties and Perceptual Agreement: The Influence of Party Related Factors on Voters’ Perceptions in Proportional Electoral Systems.” Electoral Studies 28 (2): 270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2009.01.007

- Dahlberg, Stefan. 2013. “Does Context Matter: The Impact of Electoral Systems, Political Parties and Individual Characteristics on Voters’ Perceptions of Party Positions.” Electoral Studies 32 (4): 670–683. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2013.02.003

- Dalton, Russell J., Ian McAllister, and David M. Farrell. 2011. Political Parties and Democratic Linkage: How Parties Organize Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- de Vries, Catherine E., Armen Hakhverdian, and Bram Lancee. 2013. “The Dynamics of Voters’ Left/Right Identification: The Role of Economic and Cultural Attitudes.” Political Science Research and Methods 1 (2): 223–238. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2013.4

- Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

- Fernandez-Vazquez, Pablo. 2014. “And Yet It Moves: The Effect of Election Platforms on Party Policy Images.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (14): 1919–1944. doi: 10.1177/0010414013516067

- Fortunato, David, and James Adams. 2015. “How Voters’ Perceptions of Junior Coalition Partners Depend on the Prime Minister’s Position.” European Journal of Political Research 54 (3): 601–621. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12094

- Fortunato, David, and Randolph T. Stevenson. 2013. “Perceptions of Partisan Ideologies: The Effect of Coalition Participation.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (2): 459–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00623.x

- Franzmann, Simon T. 2014. “Die Wahlprogrammatik der AfD in vergleichender Perspektive.” Mitteilungen des Instituts für Deutsches und Internationales Parteienrecht und Parteienforschung 20: 115–124.

- Golder, Matt, and Jacek Stramski. 2010. “Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 90–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00420.x

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer. 2007. “The Growing Importance of Issue Competition: The Changing Nature of Party Competition in Western Europe.” Political Studies 55 (3): 607–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00686.x

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Peter B. Mortensen. 2015. “Avoidance and Engagement: Issue Competition in Multiparty Systems.” Political Studies 63 (4): 747–764. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12121

- Grimmer, Justin. 2010. “A Bayesian Hierarchical Topic Model for Political Texts: Measuring Expressed Agendas in Senate Press Releases.” Political Analysis 18 (1): 1–35. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpp034

- Grimmer, Justin, and Brandon M. Stewart. 2013. “Text as Data: The Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts.” Political Analysis 21 (3): 267–297. doi: 10.1093/pan/mps028

- Huber, John D., and Ronald Inglehart. 1995. “Expert Interpretations of Party Space and Party Locations in 42 Societies.” Party Politics 1 (1): 73–111. doi: 10.1177/1354068895001001004

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1984. “The Changing Structure of Political Cleavages in Western Society.” In Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Realignment or Dealignment?, edited by Russell J. Dalton, Scott E. Flanagan, and Paul Allen Beck, 25–69. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann. 1976. “Party Identification, Ideological Preference and the Left-Right Dimension among Western Mass Publics.” In Party Identification and Beyond, edited by Ian Budge, Ivor Crewe, and Dennis Farlie, 234–273. London: John Wiley.

- Kitschelt, Herbert. 1994. The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Klüver, Heike, and Inaki Sagarzazu. 2016. “Setting the Agenda or Responding to Voters? Political Parties, Voters and Issue Attention.” West European Politics 39 (2): 380–398. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1101295

- Knutsen, Oddbjørn. 1995. “Value Orientations, Political Conflicts and Left-Right Identification: A Comparative Study.” European Journal of Political Research 28 (1): 63–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1995.tb00487.x

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey. 2008. West European Politics in the Age of Globalisation: Six Countries Compared. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lenz, Gabriel S. 2012. Follow the Leader? How Voters Respond to Politicians’ Policies and Performances. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lewandowsky, Marcel, Heiko Giebler, and Aiko Wagner. 2016. “Rechtspopulismus in Deutschland. Eine empirische Einordnung der Parteien zur Bundestagswahl 2013 unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der AfD.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 57 (2): 247–275. doi: 10.5771/0032-3470-2016-2-247

- Mair, Peter. 2007. “Left-Right Orientations.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, edited by Russell J. Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, 206–222. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McCombs, Maxwell. 2004. Setting the Agenda. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Merrill, Samuel, III Bernard Grofman, and James Adams. 2001. “Assimilation and Contrast Effects in Voter Projections of Party Locations: Evidence from Norway, France, and the USA.” European Journal of Political Research 40 (2): 199–221. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00594

- Merz, Nicolas. 2017. “Gaining Voice in the Mass Media: The Effect of Parties’ Strategies on Party-Issue Linkages in Election News Coverage.” Acta Politica 52 (4): 436–460. doi: 10.1057/s41269-016-0026-9

- Meyer, Thomas M., and Markus Wagner. 2016. “Issue Engagement in Election Campaigns: The Impact of Electoral Incentives and Organizational Constraints.” Political Science Research and Methods 4 (3): 555–571. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2015.40

- Meyer, Thomas, and Markus Wagner. 2017. “It Sounds Like they are Moving: Understanding and Modelling Emphasis-Based Policy Change.” Political Science Research and Methods. Advance online publication. doi:10.1017/psrm.2017.30.

- Meyer, Thomas M., and Markus Wagner. 2018. “Perceptions of Parties’ Left-Right Positions: The Impact of Salience Strategies.” Party Politics. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/1354068818806679.

- Petrocik, John R. 1996. “Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study.” American Journal of Political Science 40 (3): 825–850. doi: 10.2307/2111797

- Plescia, Carolina, and Magdalena Staniek. 2017. “In the Eye of the Beholder: Voters’ Perceptions of Party Policy Shifts.” West European Politics 40 (6): 1288–1309. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2017.1309623

- Rattinger, Hans, Sigrid Roßteutscher, Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck, Bernhard Weßels, Christof Wolf, Simon Henckel, Ina Bieber, and Philipp Scherer. 2015a. “Langfrist-Online-Tracking, Kumulation 2009–2014, Kernfragen (GLES). GESIS Datenarchiv, Köln.” ZA5749 Datenfile Version 1.1.0. doi:10.4232/1.12286.

- Rattinger, Hans, Sigrid Roßteutscher, Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck, Bernhard Weßels, Christof Wolf, Simon Henckel, Ina Bieber, and Philipp Scherer. 2015b. “Langfrist-Online-Tracking, Kumulation 2009–2014, Modulfragen (GLES). GESIS Datenarchiv, Köln.” ZA5750 Datenfile Version 1.0.0. doi:10.4232/1.12420.

- Roßteutscher, Sigrid, Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck, Harald Schoen, Bernhard Weßels, Christof Wolf, Simon Henckel, Ina Bieber, and Philipp Scherer. 2016. “Langfrist-Online-Tracking T28 (GLES). GESIS Datenarchiv, Köln.” ZA5728 Datenfile Version 2.1.0. doi:10.4232/1.12521.

- Sagarzazu, Iñaki, and Heike Klüver. 2017. “Coalition Governments and Party Competition: Political Communication Strategies of Coalition Parties.” Political Science Research and Methods 5 (2): 333–349. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2015.56

- Seeberg, Henrik Bech, Rune Slothuus, and Rune Stubager. 2016. “Do Voters Learn? Evidence that Voters Respond Accurately to Changes in Political Parties’ Policy Positions.” West European Politics 40 (2): 336–356. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2016.1245902

- Shikano, Susumu, and Franz Urban Pappi. 2004. The Positions of Parties in Ideological and Policy Space: The Perception of German Voters of their Party System. Working Paper of Mannheim Centre for European Social Research, No.73. Mannheim: MZES.

- Stokes, Donald E. 1963. “Spatial Models of Party Competition.” American Political Science Review 57 (2): 368–377. doi: 10.2307/1952828

- van der Brug, Wouter. 2004. “Issue Ownership and Party Choice.” Electoral Studies 23 (2): 209–233. doi: 10.1016/S0261-3794(02)00061-6

- Wagner, Markus, and Eva Zeglovits. 2014. “Survey Questions about Party Competence: Insights from Cognitive Interviews.” Electoral Studies 34: 280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2013.09.005

- Walgrave, Stefaan, Jonas Lefevere, and Anke Tresch. 2012. “The Associative Dimension of Issue Ownership.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (4): 771–782. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs023

- Zechmeister, Elizabeth. 2006. “What’s Left and Who’s Right? A Q-Method Study of Individual and Contextual Influences on the Meaning of Ideological Labels.” Political Behavior 28 (2): 151–173. doi: 10.1007/s11109-006-9006-5