ABSTRACT

Are expert observers and the public at large able to provide an objective assessment of the personality of political figures? We provide special attention to the (curious) personality of Donald Trump and triangulate data from seven sources: two mass surveys with US citizens, three expert surveys (in the USA, Germany, and the Netherlands), and two surveys with undergraduate students in the Netherlands. This triangulation allows us to highlight that in the US public opinions about Trump are extremely polarized even beyond partisanship; for instance, agreeable voters tend to have a better opinion of Trump if they are Democrats, whereas disagreeable individuals tend to have a better opinion of Trump if they are Republicans. Experts, on the other hand, are not as dramatically driven by their ideological preferences as some might fear, and they globally seem to agree on his extreme profile. Non-experts (Dutch students) are equally able to draw a consistent profile of Trump, more or less regardless of their personal preferences, as are experts – something that US voters seem incapable of, especially if leaning towards the right. Finally, experts and students also assess consistently the personality of selected other political figures beyond Trump – Angela Merkel, and two leading figures in Dutch politics.

Introduction and rationale

The personality of political figures

The personality of political figures matters. From the voters’ standpoint, it has been suggested that the ‘ideal political candidate’ has some clearly identifiable public persona characteristics, and ‘is seen as extremely competent, extremely high in character, quite composed and sociable, [and] slightly extroverted’ (Heixweg Citation1979). In this sense, knowing how the candidates are, their character and personality, provides voters with important cues about their future performance if elected. Growing evidence suggests indeed that candidates with a particular personality profile (low agreeableness, high conscientiousness, and even high psychopathy; Joly, Soroka, and Loewen Citation2018; Nai Citation2019) are more likely to succeed. From the elites’ perspective, on the other hand, several studies suggest that the personality of elected officials is, in part, responsible for their success or failure in discharging their duties (Joly, Soroka, and Loewen Citation2018); for instance, Watts et al. (Citation2013) show that grandiose narcissism is associated in US Presidents with a higher incidence of impeachment resolutions and unethical behaviors. All in all, these studies suggest that assessing the personality profile of political figures has much to contribute in terms of a better understanding of electoral competition, campaigning, and effective governance.

How can the personality of political figures be assessed? The majority of studies on human personality and individual differences rely on individual self-assessments or clinical examinations by psychologists and psychiatrists. In the case of political figures, however, the lack of direct contact with and easy access to the subjects makes sketching their full psychological profile potentially difficult, due to the absence of first-hand psychological data or direct access to them. A handful of studies were able to convince elected officials and local representatives to fill in standardized questionnaires including personality batteries (Joly, Soroka, and Loewen Citation2018; Nørgaard and Klemmensen Citation2019), but this practice is more of an exception than the norm and is unlikely to be effective with key players and political leaders at the national level – in lay language, it is unlikely that Donald Trump (or Barak Obama, Angela Merkel, Vladimir Putin, and so forth) will ever consent to participate to a scientific study where their personality is assessed via standardized measures. A first alternative approach that circumvents the need for direct access to political figures is the study of personality via the analysis of secondary data, such as content analysis of political speeches (Slatcher et al. Citation2007; Ramey, Klingler, and Hollibaugh Citation2019); although promising, this approach is, however, unlikely to be generalizable across different contexts and cultures (and languages), and beyond textual data. A second alternative approach, which we adopt in this article, consists in measuring the personality of political figures via expert assessments (Slatcher et al. Citation2007; Lilienfeld et al. Citation2012; Watts et al. Citation2013; Visser, Book, and Volk Citation2017; Nai and Maier Citation2018), following a rich research tradition showing substantial cross-observer agreement on personality assessments, including self-reports (e.g. Colbert et al. Citation2012). In lay language, this approach consists in identifying ‘experts’ that have a meaningful knowledge about the political figures to be assessed and asking them to rate their personality using standardized scales; ratings from multiple experts are then pooled together, to provide a full ‘perceived’ personality profile of the political figure (Nai and Maier Citation2018; Nai Citation2019).

The use of expert ratings for the evaluation of political and social phenomena, although quite frequent, is not without caveats. A frequent critique addressed to this method is the ideological skewness expert samples, as academic scholars tend to lean towards the left (Curini Citation2010). Hence, the question is: Can experts be trusted? And are they better at assessing the personality of political figures than other external observers – citizens? In this article, we contribute to this debate by looking into the curious case of the personality of Donald Trump, and other contemporary European figures (Angela Merkel, Marc Rutte, and Geert Wilders).

The curious case of Donald Trump

Given his unorthodox interpretation of the Presidency, it is unsurprising that an increasing number of studies discusses Trump’s personality (e.g. Visser, Book, and Volk Citation2017; Hyatt et al. Citation2018; Nai and Maier Citation2018). Outside academia as well the mind of Donald Trump has been a frequent topic of debate over the past few years,Footnote1 and many now call for a relaxation of the ‘Goldwater rule’ that discourages drawing conclusions about the psychological profile of public figures without direct examination (Lilienfeld, Miller, and Lynam Citation2018). Across different academic studies, a consensus seems to emerge regarding the ‘off the charts’ personality of Donald Trump, which is often characterized by very high extraversion, very low agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability, and sky-high narcissism (Visser, Book, and Volk Citation2017; Nai and Maier Citation2018; Nai, Martinez i Coma, and Maier Citation2019).

Piggybacking on the critique that scholars, because they lean towards the left, cannot be objective in assessing the personality of political figures, Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018) recently argued that using experts to profile the personality of Donald Trump yields misleading results; in their study, the authors compared Trump’s personality assessment by a convenience sample of American voters and by experts (using expert data from Nai and Maier Citation2018); using the former as a yardstick, they argue that experts tend to rate Trump too low on conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability. To be sure, it might seem odd to assume that voters’ opinions about the profile of candidates are of the same quality as opinions of scholars having worked and published in the field. Evidence suggests that voters tend to evaluate the personality reputation of political figures with a more simplified profile than the one they would apply to themselves. For instance, Caprara et al. (Citation2007) show that voters in Italy and (partially) in the USA perceive political figures along two main dimensions: friendliness, conscientiousness and emotional stability on the one side, and energy/extraversion and openness on the other. These two dimensions appear to work as ‘evaluative anchors and filters for making sense of personal information about political candidates’ (Caprara et al. Citation2007, 394). Lacking expertise, it seems thus reasonable to assume that voters often tend to rely on ideological considerations as heuristic tools to assess the personality profiles of candidates.

All in all, we have serious doubts about the validity of using voters’ estimates to judge the quality of expert ratings – or, at the very least, this exercise should be conducted carefully. Even looking at the assessments of ‘moderates’ that ‘scored at the midpoint of political orientation and did not vote for either Clinton or Trump’ (Wright and Tomlinson Citation2018, 23) is unlikely to provide the unbiased estimate that Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018) claim to obtain. First, a midpoint score on the left-right scale does not reflect political moderation – which is much more effectively captured by ‘centrist’ positions on both economic and liberal issues (Carmines, Ensley, and Wagner Citation2012), whereas a simple midpoint score on the left-right divide could equally well signal voters that average their extreme but opposite positions on the two dimensions (e.g. very liberal on social issues and very conservative on economic issues). Second, is it rather naïve to assume that having voted neither for Trump nor for Clinton is a good proxy for political moderation: these voters could be aligned with third-party candidates instead, and it is widely known that support for third-party candidates in US presidential elections is linked with greater political cynicism (Koch Citation2003) and anti-elitism (Allen and Brox Citation2005). In the 2016 election, neither the green Jill Stein nor (and especially) the libertarian Gary Johnson can honestly be defined as ‘moderate’.

Yet, the results presented in Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018) are provocative and lead to several fundamental questions. Are experts really objective when it comes to assess the personality of political figures? Can we trust the experts, or are they as influenced by their ideological preferences as voters are? And can we assume that experts and the public at large rate political figures similarly?

We suggest that assessing the quality of expert judgments by comparing it to voters’ judgments is a worthwhile endeavor overall, but scholars should use caution in contexts where voters’ opinions are extremely polarized – as it is the case in the United States today (Carmines, Ensley, and Wagner Citation2012; Baldassarri and Gelman Citation2008). Polarization ‘induces alignment along multiple lines of potential conflict and organizes individuals and groups around exclusive identities, thus crystallizing interests into opposite factions’ (Baldassarri and Gelman Citation2008, 409). Polarization makes that everything is seen through the lenses of partisanship, which blurs the lines between relevant and non-relevant issues, and creates a situation where there is no middle ground and where nuanced opinions are unlikely. Thus, ideological biases should play a greater role in polarized contexts. Shapiro and Bloch-Elkon (Citation2006, 9) advance a similar argument and suggest that political polarization has the potential to lead

to distortions in perceptions of reality and [… to produce] biases in the information that the public uses to form or alter its opinions in ways that would not serve its best interests compared to the opinions it would hold if it possessed the best available information.

This study

With this in mind, this article assesses to what extent experts and the public converge in their assessment of political figures and to what extent their political leaning conditions their ratings. We do so by triangulating data from seven sources: two mass surveys with US citizens, three expert surveys (in the USA, Germany, and the Netherlands), and two surveys with undergraduate students in the Netherlands. All these datasets measure the personality of candidates relying on the same personality inventories – more specifically, the same batteries for both the Big Five and the Dark Triad, see below - which allows for a direct comparison.

Overall, we start from the assumption that the public at large tends to evaluate the candidates in line with experts, but less so when the political environment is very polarized – as it is the case today for the United States. It is unsurprising that political opinions affect personality ratings of political figures in polarized contexts, as shown for instance in Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018) or Hyatt et al. (Citation2018). We argue however that (1) this is especially the case at the voters’ level and less so for experts – which undermines the critique of Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018), and (2) experts and the public are much more aligned in other contexts – in other terms, the US case cannot be seen as a methodological yardstick. To be sure, we do not claim to statistically test the extent to which different degrees of polarization affect the congruence between experts and the public at large. To do so, much more variation at the contextual level is required. Instead, we present here evidence that extreme partisan polarization in the US electorate biases perceptions of political elites, and in non-polarized environments the public evaluates political figures - including polarizing figures – in a way that converges strongly with expert assessments.

Method

Triangulating seven datasets

We present in this article triangulated evidence from seven datasets ().

Table 1. Datasets used, at a glance.

First, we use data from two samples of US citizens, gathered via MTurk in late 2018 (N = 1,568 and N = 1,218), to highlight the role of partisanship and polarization in political opinions and to replicate the results in Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018). Trends in these datasets will be compared, second, with data from expert surveys; the first was run just after the 2018 US Midterm elections on a sample of 200 US scholars in elections and US politics, whereas the second and third are part of a large-scale comparative expert survey about elections across the globe (Nai Citation2018, Citation2019); we use these expert surveys to draw the personality profile of Trump and other European leaders in terms of Big Five and Dark Triad, as seen by scholars. Third, we use data from two student samples (N = 201 and N = 140) where participants were also asked to rate the personality of Trump and these European figures; we triangulate these different sources of data, paneled by the ideology of respondents, in order to demonstrate that experts and the public perceive political figures quite similarly – except in the case of the US electorate, extremely polarized and thus probably biased.

American citizens’ samples (Datasets A and B)

In August and November 2018 we ran two mass surveys on two independent samples of US citizens via the online platform Amazon MTurk, which has been shown to yield quality data (Hauser and Schwarz Citation2016; Casler, Bickel, and Hackett Citation2013; Berinsky, Huber, and Lenz Citation2012). In both cases, participation was rewarded with a small sum ($0.75). After excluding respondents that failed attention checks, the final samples contain respectively 1,568 respondents (dataset A) and 1,281 respondents (dataset B). Dataset A is composed by 51.5% of female respondents, with an average age of 39.1 years (SD = 12.2). The sample is mostly composed by white/Caucasian respondents (82.8%), followed by blacks/African-Americans (8.0%), respondents of Asian origin (5.7%), and Hispanic/Latino (5.1%). A majority of 50.3% of respondents declare being ‘somewhat interested’ in politics, and only 2.2% declare ‘no interest at all’. The sample is slightly skewed to the left: the average self-reported left-right position is 4.4 (SD = 2.9) on a 0–10 scale, and 40.8% think themselves as a Democrat (26.4% Republican, 27.7% independent, 3.2% no preference, 1.9% other). Respondents in dataset A were asked to evaluate their feelings for Donald Trump and for the Republican Party using the ‘feeling thermometer’ developed by the ANES research group (Wilcox, Sigelman, and Cook Citation1989). Furthermore, respondents answered two batteries of questions intended to measure their personality traits: the TIPI for the Big Five (Gosling, Rentfrow, and Swann Citation2003), and the ‘Dirty Dozen’ (D12) for the Dark Triad (Jonason and Webster Citation2010). The composition of dataset B is very similar: 51.1% female, 39.6 years on average (SD = 12.6), 79.3% Caucasian (9.6% blacks/African-Americans), high interest in politics, 48.7% identify with Democrats (30.9% Republicans), and relatively left-to-center average self-placement (4.1/10, SD = 3.1). Respondents in dataset B were asked to evaluate the personality of President Trump; we report these results below.

Expert personality ratings (datasets C, D and E)

In the direct aftermath of the 2018 US Midterm elections, we contacted a sample of US scholars in elections and US politics and asked them to evaluate (among other issues) the personality of Donald Trump using the same batteries for the Big Five and Dark Triad described above. 200 experts answered our questionnaire, and their answers are aggregated to draw the profile of the current President (dataset C). On average, these experts declared themselves very familiar with US elections (M = 7.81/10, SD = 2.05), and estimated that the questions in the survey were easy to answer (M = 7.53, SD = 2.39). 27% of experts in the sample are female, 50.2% worked at the time of the survey (November 2018) in a ‘red’ state won by Trump in 2016, and their average age is 54.8 years (SD = 13.6). Most importantly, the overall sample of experts leans quite strongly to the left, with an average self-reported score on the left-right scale of 3.2 out of 10 (SD = 1.43), in line with known trends for academia (e.g. Solon Citation2015). Of course, a skewed sample is not enough to suspect biased aggregate assessments – for this, the effect of ideology on expert ratings has to be proven. As we will see, evidence in this sense is much less dramatic than some might fear

We also use part of a larger comparative dataset about the personality and campaigning style of candidates worldwide (Nai Citation2018, Citation2019), to present the personality of three additional political figures, which we use as benchmark beyond the Trump case: Mark Rutte (the current Dutch PM and leader of the centre-right VVD), Geert Wilders (the provocateur and polarizing leader of the Dutch far-right populist PVV), and the Christian Democratic Chancellor Angela Merkel. 29 experts provided answers for the Dutch election, and 38 for the German election. Personality measures in these last datasets (D and E) use a shorter version of the ‘Dirty Dozen’ (D12) battery based on the principal component analyses described in Jonason and Webster (Citation2010, 422); we selected the two items that correlate the highest with each trait and use them as a battery.

Student samples

In late 2017, we asked two samples of undergraduate students in communication at the University of AmsterdamFootnote2 to evaluate four candidates using the TIPI for the Big Five and our short version of the D12 for the Dark Triad. In study 1, respondents evaluated the personality of Donald Trump (N = 201), whereas in study 2 participants evaluated the personality of Mark Rutte, Geert Wilders, and Angela Merkel (N = 140). Attention checks (Berinsky, Margolis, and Sances Citation2014) were used in both studies. The composition of these student samples is, expectedly, skewed in terms of gender (respectively 82.6% and 80.7% of female respondents), age (20.6 and 20.7 years of age in average), and ideological positioning (respectively, 4.0 and 4.3 out of 10).

Results

Polarization, personality and partisanship in the US electorate

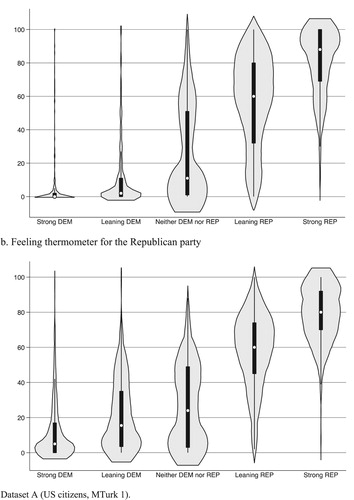

Perhaps no political figure has been as polarizing as Donald Trump in recent memory. A look at the data for the first US sample (Dataset A: MTurk, N = 1,568) shows indeed that opinions about the current president are not only extreme, but also extremely contrasted depending on the respondent ideological affiliation. plots the distribution of opinions about Trump (panel a) using the ‘feeling thermometer’, paneled by the partisan affiliation of the respondent. The contrast between the very cold feelings for Trump in Democrats and very warm feelings in Republicans appears clearly. The extremely low (and consensual) opinion about Trump in respondents declaring a strong identification with the Democratic party is particularly remarkable; for that group of voters, the average warmth for Trump is 6.2 out of 100 (SD = 17.4). Opinions about the Republican party (panel b) also vary as a function of partisan identification, of course. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the differences between opposed poles is especially present in opinions about Trump.

Figure 1. Evaluation of Trump and the Republican party by partisan identification; violin plots (a) Feeling thermometer for Donald Trump. (b) Feeling thermometer for the Republican party. Dataset A (US citizens, MTurk 1).

The strong effect of partisanship on feelings for Trump and the GOP exists also when controlling for the socio-demographic profile of the respondent (gender, age, race), interest in politics, and personality traits (Tables A1 and A2 in the Appendix). Female, younger voters, and African-Americans tend to have a worse opinion about the current President, but the effect disappears once controlling for partisanship. Interestingly, a more positive opinion of Trump exists for respondents high in extraversion, low openness and high narcissism. The fact that this aligns with some aspects of Trump’s own personality (Visser, Book, and Volk Citation2017; Nai and Maier Citation2018; Nai, Martinez i Coma, and Maier Citation2019) supports the ‘homophily’ theories according to which voters tend to support candidates with personalities that ‘match’ their own (Caprara and Zimbardo Citation2004; Fortunato, Hibbing, and Mondak Citation2018).

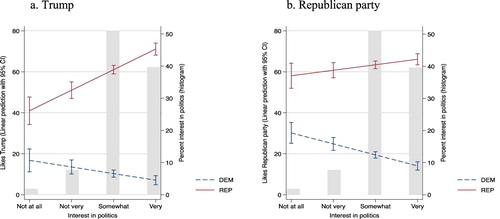

Model M3 in both tables interacts partisanship with interest in politics, and shows significant results for both evaluation of Trump and its party. In both cases, polarization between Democrats and Republicans is stronger at higher levels of political interest, but the substantive interpretation of the effects differs however in the two cases. As illustrated in (marginal effects with 95% CIs), an increase in interest in politics especially drives positive feelings for Trump in Republicans (less so in Democrats, panel a), whereas a higher interest especially drives negative feelings for the party in Democrats (less so in Republicans, panel b). In other terms, interest in politics makes Republicans like more Trump and Democrats dislike more the GOP.

Figure 2. Evaluation of Trump and the Republican party by interest in politics * partisan identification; marginal effects. (a) Trump. (b) Republican party. Note: Dataset A (US citizens, MTurk 1). Marginal effects with 95% Confidence intervals, based on coefficients in model M3 in Table 1 (panel a) and Table 2 (panel b). Panel a. Dependent variable is evaluation of Trump (“feeling thermometer”) and varies between 0 “no warm feelings at all” and 100 “very warm feelings”. Panel b. Dependent variable is evaluation of the Republican party (“feeling thermometer”) and varies between 0 “no warm feelings at all” and 100 “very warm feelings”.

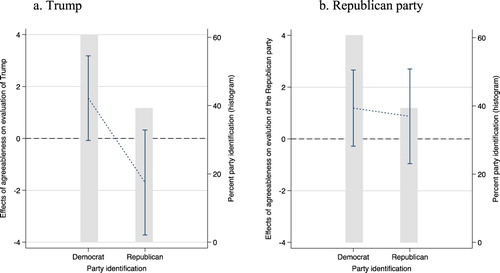

Finally, model M4 in both tables adds a series of interaction effects between partisanship and the personality traits of respondents. Overall, effects are again much stronger for Trump, suggesting that opinions about this candidate tend to polarize beyond partisanship. For example, agreeable individuals tend to have a better opinion of Trump if they are Democrats, whereas disagreeable individuals tend to have a better opinion of Trump if they are Republicans (, panel a); this effect is completely absent when it comes to evaluating the Republican party (panel b). The same effect exists for psychopathy. The only effect that is stronger for the GOP than for Trump is the interaction between partisanship and emotional stability – emotionally stable respondents tend to have a better opinion of the GOP if they are Democrats, whereas neurotics have a better opinion of the GOP if they are Republicans (the effect does not exist for Trump).

Figure 3. Evaluation of Trump and the Republican party by agreeableness * partisan identification; marginal effects. (a) Trump. (b) Republican party. Note: Dataset A (US citizens, MTurk 1). Marginal effects with 95% Confidence intervals, based on coefficients in model M3 in (panel a) and (panel b). Panel a. Dependent variable is evaluation of Trump (‘feeling thermometer’) and varies between 0 ‘no warm feelings at all’ and 100 ‘very warm feelings’. Panel b. Dependent variable is evaluation of the Republican party (‘feeling thermometer’) and varies between 0 ‘no warm feelings at all’ and 100 ‘very warm feelings’. Scores on the y-axis refer to the linear effect of agreeableness on that evaluation

Taking stock, these analyses reveal the very strong and polarizing effect of partisanship in the current US electorate. Polarization is not only stronger for Trump than for its party, but also exists beyond partisanship, for instance in terms of interest in politics and the personality of respondents.

Expert ratings and ideology

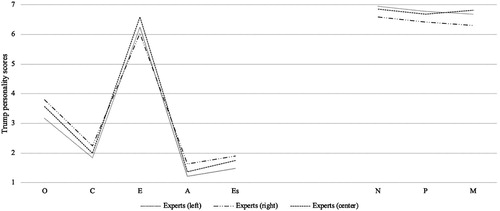

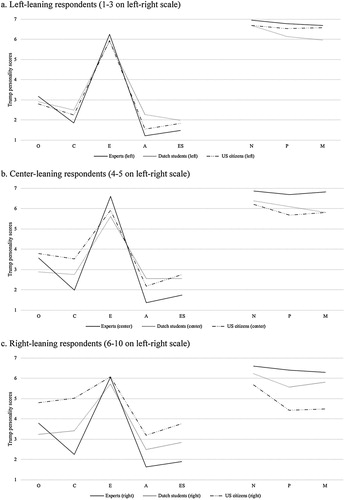

If US citizens seem doomed to have skewed opinions of political leaders (and especially their current President) based on their partisan identification, should the same be feared about expert observers? This is what Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018) suggest. Indeed, we concur that it would be absurd to believe that experts provide completely neutral assessments. It is however the extent of such ideological biases that matters. compares the average ratings of Big Five and Dark Triad for Trump provided by our experts, according to their ideological profile; given the distribution of experts in our sample, skewed towards the center-left, we compare the three following categories of ideology: left (scores between 1 and 3 on the left-right scale), center (4–5), and right (between 6 and 10). Results of a series of t-tests comparing left- with right-leaning experts are as followsFootnote3: extraversion: t(141) = 0.71, p < .478, d = 0.12 ; agreeableness: t(142) = −1.53, p < .027, d = 0.26; conscientiousness: t(139) = −0.96, p < .271, d = 0.16; emotional stability: t(139) = −1.43, p < .155, d = 0.24; openness: t(140) = −1.69, p < .092, d = 0.23; narcissism: t(144) = 4.16, p < .000, d = 0.69; psychopathy: t(139) = 2.00, p < .047, d = 0.34; Machiavellianism: t(142) = 2.24, p < .027, d = 0.38. Four significant differences are identified, but their magnitude remains relatively modest, with an achieved statistical power between 15.7% and 64.5%.Footnote4 The modest magnitude of the differences between left and right-leaning experts, even if significant, can be seen in against the full range of the personality variables (1–7).

Figure 4. Trump Big Five and Dark Triad personality traits; comparing left-, center-, and right-leaning experts. Note: Dataset C (Experts, US Midterms). N(left) = 127–132; N(center) = 46–51; N(right) = 14. Ideological leaning based on self-reported score on the left-right scale: 0–3 ‘left’, 4–5 ‘center’, 6–10 ‘right’.

Table 2. Experts evaluate the personality of Trump (by ideology).

We go a step further, and regress the experts’ evaluations of Trump’s psychological profile – separately for each trait in the Big Five (Table A3 in the Appendix) and Dark Triad (Table A4) – on their ideological positioning; the regressions also include several controls that account for other expert characteristics: self-reported familiarity with US elections (from 0 ‘not familiar at all’ to 10 ‘very familiar’), self-reported ease in answering the questionnaire (from 0 ‘very hard’ to 10 ‘very easy’), geographical location of the expert (more specifically, whether or not the expert works in a ‘red’ state won by Trump in 2016), gender, age, and self-evaluated discipline of specialization (five dummy variables for specialization in elections and electoral behavior, political psychology, US politics, political communication, and methods). The regressions show some significant results for ideology. Right-leaning experts seem more positive concerning Trumps’ agreeableness and emotional stability (Table A3) and less critical on his narcissism and Machiavellianism (Table A4); these effects remain however relatively marginal, with perhaps the exception of emotional stability: a move of one unit towards the right increases Trump’s perceived emotional stability by 0.14 units (on a 1–7 scale). Similarly, a move of one unit towards the right decreases Trump’s perceived narcissism by 0.05 units. In other terms, between an expert on the very extreme left and an expert on the very extreme right there is only about 1–1.5 point of difference at the most on these traits, which is substantially smaller than some differences we show below between American and Dutch respondents

Public ratings and ideology

Much of the critique of Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018) rests on their analysis of personality ratings provided by a convenience sample of the American public, compared across ideological lines with the ratings provided by the experts in Nai and Maier (Citation2018). Their results suggest that experts evaluated Trump lower in conscientiousness and agreeableness than American voters in their sample having supported Clinton; furthermore, experts rated Trump lower in conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability than ‘politically moderate’ American voters.

We do not contest the empirical reliability of their findings. Hyatt et al. (Citation2018) also find that the perceived personality profile of Trump differs depending on whether the responded voted for Trump or Clinton in the 2016 election; where Trump voters see high extraversion and emotional stability, Clinton voters see low conscientiousness (both agree on high narcissism and psychopathy, though). Data from our second MTurk study from November 2018 (dataset B) also shows similar trends, described in . Results of a series of t-tests comparing left- with right-leaning US citizens are as follows: extraversion: t(964) = −1.91, p < .057, d = 0.12; agreeableness: t(964) = −20.51, p < .000, d = 1.32; conscientiousness: t(964) = −26.66, p < .000, d = 1.72; emotional stability: t(964) = −20.50, p < 000., d = 1.32; openness: t(964) = −22.43, p < .000, d = 1.44; narcissism: t(964) = 14.28, p < .000, d = 0.92; psychopathy: t(964) = 25.01, p < .000, d = 1.61; Machiavellianism: t(964) = 23.98, p < .000, d = 1.54.

Table 3. US citizens evaluate the personality of Trump (by ideology).

As shown in the Table, respondents form the left tended to evaluate Trump’s agreeableness and openness as much lower than respondents on the right, whereas the reverse is true for psychopathy and Machiavellianism.

Given the current high levels of polarization in the American society, finding skewed perception is all but surprising. Indeed, we argue that using the perceptions of a highly polarized electorate to validate the opinion of experts – as Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018) do – is a doomed exercise in the first place. How can voters’ perceptions used as a benchmark to assess the quality of experts, given the profound differences driven by partisan affiliation and ideology found in the electorate? As discussed above, extreme polarization – as it is currently the case in the US – reinforces the role of partisan preferences on political opinion; in such a context, it is normal to expect that citizens’ evaluations of political figures strongly diverges across the partisan divide. It results from this logic that citizens in less polarized contexts should be able to provide less skewed assessments. To substantiate this claim, we gathered data from undergraduate students at the University of Amsterdam (dataset F), which should logically not be affected by the extreme levels of partisan polarization existing in the American context. presents Trump’s personality scores as assessed by Dutch students. Results of a series of t-tests comparing left- with right-leaning Dutch students are as follows: extraversion: t(134) = 0.81, p < .419, d = 0.14; agreeableness: t(135) = −1.19, p < .238, d = 0.20; conscientiousness: t(125) = −3.56, p < .001, d = 0.64; emotional stability: t(131) = −3.65, p < .001, d = 0.64; openness: t(126) = −1.43, p < .156, d = 0.25; narcissism: t(134) = 3.10, p < .002, d = 0.54; psychopathy: t(131) = 2.48, p < .014, d = 0.43; Machiavellianism: t(127) = 0.89, p < .376, d = 0.16.

Table 4. Dutch students evaluate the personality of Trump (by ideology).

compares how experts (dataset C) Dutch students (dataset F) and American voters in our second MTurk sample (dataset B) assessed the personality of Trump, paneled by their ideological profile.Footnote5 The differences across the samples - and especially between the US citizens and Dutch students samples - are substantial, especially among right-leaning respondents; for instance, American citizens show very high levels of openness for Trump among respondents on the right (Mean = 4.79, SD = 1.34), whereas right-wing respondents in the Dutch students sample evaluated Trump with lower than average openness (Mean = 3.24, SD = 1.32); the difference between the two scores is considerable (t(450) = 7.30, p < .000, d = 0.69); a similar trend exists for conscientiousness and, to a lesser extent, emotional stability. Looking at the Dark Triad, right-wing US voters are substantially less critical of President Trump when it comes to psychopathy and (especially) Machiavellianism than Dutch students; the difference between the two assessments is, again, significant at p < .001 and relatively important (t(452) = −4.94, p < .000, d = 0.46).

Figure 5. Trump Big Five and Dark Triad personality traits; comparing experts, American citizens and Dutch students (by ideology). (a) Left-leaning respondents (1–3 on left-right scale). (b) Center-leaning respondents (4–5 on left-right scale). (c) Right-leaning respondents (6–10 on left-right scale). Note: Comparison of scores from Dataset B (US citizens, MTurk 2), Dataset C (Experts, US Midterms), and Dataset F (Dutch students, sample 1) Ideological leaning based on self-reported score on the left-right scale: 0–3 ‘left’, 4–5 ‘center’, 6–10 ‘right’.

If there is one conclusion that can be taken from is that differences across observers mostly come from the fact that US voters diverge from all other observers (experts and Dutch students), especially among right-wing respondents. This result is perfectly in line with the idea that polarization in the US is driven by ‘asymmetric’ dynamics and, more specifically, with the fact that Republicans have moved towards the right much more than Democrats have moved towards the left in recent times (Russell Citation2018; Hacker and Pierson Citation2006).

Figure A1 in the Appendix then compares the average ratings in the Dutch student sample (also paneled by left-leaning, moderates, and right-leaning respondents) with the average expert scores, for both the Big Five and the Dark Triad. Two conclusions can be drawn; first, the differences in ratings for both the Big Five and Dark Triad traits across respondents of different ideological profiles are minimal – and substantially smaller than the differences in the American voter sample – supporting our intuition about the distortive effect of high polarization. Second, student ratings are fairly aligned with expert ratings – at the very least, substantially more aligned that experts are when compared with American voters. All in all, shows that two extremely different samples of respondents – scholars of elections and US politics, on the one hand, and undergraduate Dutch students, on the other – provide fairly consistent evaluations of Trump’s personality profile, both in terms of Big Five and Dark Triad traits.

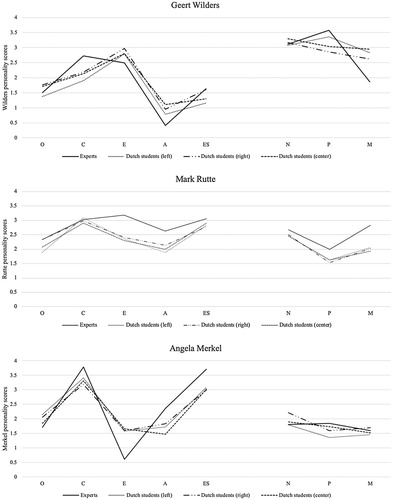

Figure 6. The personality of Wilders, Rutte, and Merkel; comparing evaluations by experts and Dutch students (by ideology). Notes: Comparison of scores from Dataset D (Experts, Netherlands election 2017), Dataset D (Experts, Germany election 2017), and Dataset G (Dutch students, sample 2). Ideological leaning based on self-reported score on the left-right scale: 0–3 ‘left’, 4–5 ‘center’, 6–10 ‘right’. Personality evaluations range from 0 ‘very low’ to 4 ‘very high’. See table A1 in the appendix for full scores.

Beyond Trump: the personality of Mark Rutte, Geert Wilders and Angela Merkel

Trump is a particularly divisive figure, and one that has benefitted from unparalleled media attention. In this sense his personality profile, as evaluated by external observers, can be expected to be particularly contrasted. As an additional piece of evidence, we replicated the comparison between expert and student ratings for three additional candidates, very different in profile, ideology, and electoral fortune: two of the main actors in contemporary Dutch Politics (the current PM Mark Rutte, and the PVV leader Geert Wilders), and the German Chancellor Angela Merkel. compares the average scores with the expert ratings (detailed results can be found in Table A5 in the Appendix). The aim of this additional comparison is to show that experts and non-experts (in this case, students) can converge in their assessments in less polarized contexts. Furthermore, looking at political figures from both the Netherlands and Germany, and finding similar patterns, suggests that external observers can judge both domestic and foreign leaders – thus increasing the relevance of Dutch observers for Trump.

The figure shows that experts and students agreed in identifying the distinctive traits of these three personalities. Geert Wilders, leader of the far-right Party for Freedom (PVV), is often compared to Trump, perhaps due to his ‘bizarre bouffant platinum hairdo [… and his willingness to test] the standards of permissible speech’,Footnote6 but mostly because of his alleged ‘controversial attitude and aberrant political style’ (De Landsheer and Kalkhoven Citation2014) and because he is ‘not trying at all to be agreeable’.Footnote7 Wilder is, by any standards, a polarizing figure; however, in a lesser polarized context as the Dutch party system, even polarized figures can be assessed objectively. Indeed, shows that observers, both experts and students, seem to agree with this overall assessment and see Wilders as having a rather contrasted profile in terms of high extraversion, low agreeableness, and high narcissism.

Rutte, on the other hand, is usually portrayed as stable and displaying an agreeable personality – which seems to be reflected in the observers’ evaluations as well. Finally, Angela Merkel is known for her calm, disciplined and pragmatic style, but also for having a relatively uncharismatic personality; she is often described as ‘reserved, rational and uninspiring’,Footnote8 having a public speaking style ‘as inspiring as the Eurozone quarterly growth figures’,Footnote9 and lacking ‘passion and an emphasis on feelings [… but displaying a] technocratic and sober style of governance’.Footnote10 The bottom panel of suggests that all observers – both experts and students – once again picked up these main traits; Merkel’s profile appears characterized by high conscientiousness and stability, and low scores on the Dark Triad, but also quite low agreeableness, extraversion, and openness.

Beyond the profiles themselves, the comparison across different ratings suggests two conclusions: first, Dutch students evaluated the different candidates relatively consensually, independently of their ideological profile and regardless of whether the political figure is domestic or foreign. As shown before for Trump, their ideology seems to play a minor role in their assessment of these three candidates, suggesting again that external observers can have unbiased evaluations in non-polarized contexts. Second, student and expert ratings are oftentimes very close. To be sure, some differences between experts and students exist – reason why we rely on experts in the first place, as others before us (Rubenzer and Faschingbauer Citation2004; Lilienfeld et al. Citation2012; Visser, Book, and Volk Citation2017). Nonetheless, the overall consistency within the student sample and the coherent general trends between students and experts suggest that expert ratings are not as biased as it is sometimes suggested (Curini Citation2010; Wright and Tomlinson Citation2018).

Discussion

Politics is a complex matter, and voters often require simplified cues to help them navigate all conflicting information they are exposed to (Lau and Redlawsk Citation2001). Recent research shows that non-political characteristics of candidates (their ‘image’) can simplify the decisional task for them. For instance, many studies find that more attractive candidates have a comparative advantage (e.g. Lawson et al. Citation2010; Antonakis and Dalgas Citation2009).

With this in mind, and in the wake of the renewed interest in individual psychological differences as a driver of political behavior (Gerber et al. Citation2011), increasing attention has been provided recently on the personality of political figures (Visser, Book, and Volk Citation2017; Costa Lobo Citation2018; Bittner and Peterson Citation2018; Nai and Maier Citation2018; Nai and Martinez i Coma Citation2019). Beyond the methodological challenges involved in the measure of psychological profiles of political elites, a lingering question in this field is whether external observers are able to correctly assess the personality of candidates and elected officials – and, more specifically, whether they are able to draw personality profiles of key political figures objectively, without being influenced by their own political views. People, after all, are motivated reasoners that filter the information they are exposed to through the sieve of partisanship and tend to reject information that clashes against their predispositions (Taber and Lodge Citation2006).

Recent research makes use of expert ratings to draw the profile of political figures, such as the personality of the 45th US president (Visser, Book, and Volk Citation2017; Nai and Maier Citation2018; Nai, Martinez i Coma, and Maier Citation2019). In this case, questions have been raised as to whether experts are really objective or whether their ideological predispositions bias their evaluations (Wright and Tomlinson Citation2018), leading to a broader question: do experts and the public perceive the personality of important political figures alike? In this article, we argued that this should normally be the case and that ideological differences in the observers – experts, and the public at large – drive less their perceptions of candidates’ personality that some might assume (or fear). We also argued however that it is less likely to find convergent assessment in highly polarized contexts. In polarized contexts, such as today’s America (Carmines, Ensley, and Wagner Citation2012; Baldassarri and Gelman Citation2008), electoral races and political confrontation are driven by extreme partisanship, and voters’ political preferences tend to reflect and exaggerate the contrast between the elites (Layman and Carsey Citation2002). In such a set of circumstances, we argued, voters’ opinions cannot be used as benchmark against which to gauge the quality of expert opinions, as done for instance in Wright and Tomlinson (Citation2018).

Triangulating multiple data sources – scholars in US politics (‘experts’), American voters, and Dutch undergraduate students – we were able to show several trends: (1) in the American public, opinions about Trump are extremely polarized – even more so than opinions about the Republican party – and opinions polarize even beyond partisanship; for instance, agreeable voters tend to have a better opinion of Trump if they are Democrats, whereas disagreeable individuals tend to have a better opinion of Trump if they are Republicans; (2) When it comes to assessing the personality of Trump, experts (scholars) are only marginally driven by their ideological preferences, and they globally seem to agree on his extreme profile: extreme extraversion, low agreeableness and conscientiousness, high narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism; (3) Non-experts (Dutch students) are equally able to draw a consistent profile of Trump, independent from their personal preferences, as are experts – something that US voters seem incapable of: in line with the literature showing ‘asymmetric’ dynamics of polarization (Russell Citation2018; Hacker and Pierson Citation2006), our results suggest that especially right-wing US citizens have particularly skewed - and unrealistic – perceptions of Trump’s profile; (4) Finally, experts and the public also assess consistently the personality of selected other political figures beyond Trump – Angela Merkel, and two leading figures of Dutch politics. All in all, these results jointly suggest that people might have polarized opinions (as shown in Wright and Tomlinson Citation2018; Hyatt et al. Citation2018), but that overall experts and the public can globally be expected to draw a consistent profile of leading political figures. The fact however that some citizens, under some conditions, seem to fail to master this task requires further investigation, and is particularly relevant in light of the research showing that voters take the personality profiles of candidates into account when formulating their choices (e.g. Caprara and Zimbardo Citation2004).

Taken together, the evidence triangulated in this article suggests that Donald Trump is exceptional when looking at his personality profile (Nai, Martinez i Coma, and Maier Citation2019) but is not an exception, compared to other leaders across the world, when it comes to systematically assess their profile. In this sense, the approach described in this article seems likely to be generalizable beyond the cases described here.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (183.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for their critiques, constructive comments, and suggestions; any remaining mistakes are of course our responsibility alone. Alex Nai acknowledges the material support provided by the Electoral Integrity Project (Harvard University and University of Sydney). Many thanks to the experts, students, and MTurkers that participated in our surveys, without whom this and other related work would not have been possible. Thanks also to Joshua D. Wright and Monica F. Tomlinson for their critical assessment of our previous study (both published in Personality and Individual Differences), which gave us the impulsion to write this piece.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alessandro Nai

Alessandro Nai is an assistant professor of Political Communication and Journalism at the Department of Communication Science, University of Amsterdam. His recent work has been published in journals such as Political Psychology, European Journal of Political Research, West European Politics, Government and Opposition, European Political Science, Personality and Individual Differences, Presidential Studies Quarterly, Electoral Studies, Journal of Political Marketing, and more. He recently co-edited the volumes New Perspectives on Negative Campaigning: Why Attack Politics Matters (ECPR Press, 2015, with Annemarie S. Walter) and Election Watchdogs (Oxford University Press, 2017, with Pippa Norris). He is currently an associate editor of the Journal of Social and Political Psychology.

Jürgen Maier

Jürgen Maier is a professor of Political Communication at the University of Koblenz-Landau (Germany). His research focuses on media coverage of politics and its effects, political attitudes, electoral behavior, and quantitative methods. Within these fields, he is specialized in televised debates, political scandals, negative campaigning, experimental designs, and real-time response measurement.

Notes

1 See, for instance: Dan P. McAdams, “The mind of Donald Trump”, The Atlantic, June 2016.

2 Students were given a modest incentive to participate (0.18 research credits).

3 To compute the effect size (Cohen’s d) for independent samples t-tests we used the following approximation: (2 * t) / √(df)

4 Post-hoc (“achieved”) statistical power was computed via the software G*Power (Faul et al. Citation2007). For one-tailed tests the post-hoc statistical power was estimated as follows: extraversion 64.5%, agreeableness 15.7%, conscientiousness 48.3%, emotional stability 43.5%, openness 30.4%, narcissism 25.0%, psychopathy 31.8%, Machiavellianism 27.9%.

5 In all analyses, and in all samples (voters, experts, students), the ideological profile was computed from self-reported left-right scores and recoded in three categories: left (0–3), center (4–5) and right (6–10).

6 James Traub, “The Geert Wilders Effect”, Foreign Policy, 13 March 2017.

7 James McBride, “Dutch Elections and the Future of the EU”, Council on Foreign Relations, 10 March 2017.

8 Jochen Hung, “Why Germans love the enigmatic Angela Merkel”, The Guardian, 15 August 2012.

9 Katherine Butler, “Angela Merkel and the myth of charismatic leadership”, The Independent, 12 September 2013.

10 Julian Göpffarth, “‘Straight outta Würselen’ and straight into the German Chancellery? Martin Schulz and the SPD’s resurgence”, LSE Blog, 15 February 2017.

References

- Allen, N., and B. J. Brox. 2005. “The Roots of Third Party Voting: The 2000 Nader Campaign In Historical Perspective.” Party Politics 11 (5): 623–637. doi: 10.1177/1354068805054983

- Antonakis, J., and O. Dalgas. 2009. “Predicting Elections: Child's Play!.” Science 323 (5918): 1183–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.1167748

- Baldassarri, D., and A. Gelman. 2008. “Partisans Without Constraint: Political Polarization and Trends in American Public Opinion.” American Journal of Sociology 114 (2): 408–446. doi: 10.1086/590649

- Berinsky, A. J., G. A. Huber, and G. S. Lenz. 2012. “Evaluating Online Labor Markets for Experimental Research: Amazon.com's Mechanical Turk.” Political Analysis 20: 351–368. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpr057

- Berinsky, A. J., M. F. Margolis, and M. W. Sances. 2014. “Separating the Shirkers from the Workers? Making Sure Respondents Pay Attention on Self-Administered Surveys.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (3): 739–753. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12081

- Bittner, A., and D. A. Peterson. 2018. “Introduction: Personality, Party Leaders, and Election Campaigns.” Electoral Studies 54: 237–239. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.005

- Caprara, G. V., C. Barbaranelli, R. C. Fraley, and M. Vecchione. 2007. “The Simplicity of Politicians’ Personalities Across Political Context: An Anomalous Replication.” International Journal of Psychology 42 (6): 393–405. doi: 10.1080/00207590600991104

- Caprara, G. V., and P. G. Zimbardo. 2004. “Personalizing Politics: A Congruency Model of Political Preference.” American Psychologist 59 (7): 581–594. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.581

- Carmines, E. G., M. J. Ensley, and M. W. Wagner. 2012. “Who Fits the Left-Right Divide? Partisan Polarization in the American Electorate.” American Behavioral Scientist 56 (12): 1631–1653. doi: 10.1177/0002764212463353

- Casler, K., L. Bickel, and E. Hackett. 2013. “Separate but Equal? A Comparison of Participants and Data Gathered Via Amazon’s MTurk, Social Media, and Face-To-Face Behavioral Testing.” Computers in Human Behavior 29: 2156–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.009

- Colbert, A. E., T. A. Judge, D. Choi, and G. Wang. 2012. “Assessing the Trait Theory of Leadership Using Self and Observer Ratings of Personality: The Mediating Role of Contributions to Group Success.” The Leadership Quarterly 23 (4): 670–685. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.03.004

- Costa Lobo, M. 2018. “Personality Goes a Long Way.” Government and Opposition 53 (1): 159–179. doi: 10.1017/gov.2017.15

- Curini, L. 2010. “Experts’ Political Preferences and Their Impact on Ideological Bias: An Unfolding Analysis Based on a Benoit-Laver Expert Survey.” Party Politics 16 (3): 299–321. doi: 10.1177/1354068809341051

- De Landsheer, C., and L. Kalkhoven. 2014. “The Imagery of Geert Wilders, Leader of the Dutch Freedom Party (PVV).” Paper presented at the IPSA World Congress, Canada, July 2014.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A.-G. Lang, and A. Buchner. 2007. “G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences.” Behavior Research Methods 39: 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

- Fortunato, D., M. V. Hibbing, and J. J. Mondak. 2018. “The Trump Draw: Voter Personality and Support for Donald Trump in the 2016 Republican Nomination Campaign.” American Politics Research 46 (5): 785–810.

- Gerber, A. S., G. A. Huber, D. Doherty, and C. M. Dowling. 2011. “The Big Five Personality Traits in The Political Arena.” Annual Review of Political Science 14: 265–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051010-111659

- Gosling, S. D., P. J. Rentfrow, and W. B. Swann. 2003. “A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains.” Journal of Research in Personality 37 (6): 504–528. doi: 10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

- Hacker, J. S., and P. Pierson. 2006. Off Center: The Republican Revolution and the Erosion of American Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hauser, D. J., and N. Schwarz. 2016. “Attentive Turkers: MTurk Participants Perform Better On Online Attention Checks than do Subject Pool Participants.” Behavior Research Methods 48: 400–407. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0578-z

- Heixweg, S. 1979. “An Examination of Voter Conceptualizations of the Ideal Political Candidate.” Southern Journal of Communication 44 (4): 373–385. doi: 10.1080/10417947909372427

- Hyatt, C., W. K. Campbell, D. R. Lynam, and J. D. Miller. 2018. “Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde? President Donald Trump’s Personality Profile as Perceived from Different Political Viewpoints.” Collabra: Psychology 4 (1). doi:10.1525/collabra.162.

- Joly, J., S. Soroka, and P. Loewen. 2018. “Nice Guys Finish Last: Personality and Political Success.” Acta Politica. doi:10.1057/s41269-018-0095-z.

- Jonason, P. K., and G. D. Webster. 2010. “The Dirty Dozen: A Concise Measure of the Dark Triad.” Psychological Assessment 22 (2): 420. doi: 10.1037/a0019265

- Koch, J. W. 2003. “Political Cynicism and Third Party Support in American Presidential Elections.” American Politics Research 31 (1): 48–65. doi: 10.1177/1532673X02238579

- Lau, R. R., and D. P. Redlawsk. 2001. “Advantages and Disadvantages of Cognitive Heuristics in Political Decision Making.” American Journal of Political Science 45 (4): 951–971. doi: 10.2307/2669334

- Lawson, C., G. S. Lenz, A. Baker, and M. Myers. 2010. “Looking Like a Winner: Candidate Appearance and Electoral Success in New Democracies.” World Politics 62 (04): 561–593. doi: 10.1017/S0043887110000195

- Layman, G. C., and T. M. Carsey. 2002. “Party Polarization and “Conflict Extension“ in the American Electorate.” American Journal of Political Science 46 (4): 786–802.

- Lilienfeld, S. O., J. D. Miller, and D. R. Lynam. 2018. “The Goldwater Rule: Perspectives from, and Implications for, Psychological Science.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 13 (1): 3–27. doi: 10.1177/1745691617727864

- Lilienfeld, S. O., I. D. Waldman, K. Landfield, A. L. Watts, S. Rubenzer, and T. R. Faschingbauer. 2012. “Fearless Dominance and the US Presidency: Implications of Psychopathic Personality Traits for Successful and Unsuccessful Political Leadership.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 103 (3): 489–505. doi: 10.1037/a0029392

- Nai, A. 2018. “Going Negative, Worldwide. Towards a General Understanding of Determinants and Targets of Negative Campaigning.” Government & Opposition. doi:10.1017/gov.2018.32.

- Nai, A. 2019. “Disagreeable Narcissists, Extroverted Psychopaths, and Elections. A New Dataset to Measure the Personality of Candidates Worldwide.” European Political Science 18 (2): 309–334. doi: 10.1057/s41304-018-0187-2

- Nai, A., and J. Maier. 2018. “Perceived Personality and Campaign Style of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump.” Personality and Individual Differences 121: 80–83. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.020

- Nai, A., and F. Martinez i Coma. 2019. “The Personality of Populists: Provocateurs, Charismatic Leaders, or Drunken Dinner Guests?” West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1599570.

- Nai, A., F. Martinez i Coma, and J. Maier. 2019. “Donald Trump, Populism, and the Age of Extremes: Comparing the Personality Traits and Campaigning Style of Trump and Other Leaders Worldwide.” Presidential Studies Quarterly. doi:10.1111/psq.12511.

- Nørgaard, A. S., and R. Klemmensen. 2019. “The Personalities of Danish MPs: Trait-and Aspect-Level Differences.” Journal of Personality 87 (2): 267–275. doi:10.1111/jopy.12388.

- Ramey, A. J., J. D. Klingler, and G. E. Hollibaugh. 2019. “Measuring Elite Personality Using Speech.” Political Science Research and Methods 7 (1): 163–184. doi:10.1017/psrm.2016.12.

- Rubenzer, S. J., and T. R. Faschingbauer. 2004. Personality, Character, and Leadership in the White House: Psychologists Assess the Presidents. Washington, DC: Brassey’s.

- Russell, A. 2018. “US Senators on Twitter: Asymmetric Party Rhetoric in 140 Characters.” American Politics Research 46 (4): 695–723. doi: 10.1177/1532673X17715619

- Shapiro, R. Y., and Y. Bloch-Elkon. 2006. “Political Polarization and the Rational Public.” Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR), Montreal, Canada, May 2006.

- Slatcher, R. B., C. K. Chung, J. W. Pennebaker, and L. D. Stone. 2007. “Winning Words: Individual Differences in Linguistic Style among US Presidential and Vice Presidential Candidates.” Journal of Research in Personality 41 (1): 63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.01.006

- Solon, I. S. 2015. “Scholarly Elites Orient Left, Irrespective of Academic Affiliation.” Intelligence 51: 119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2015.06.004

- Taber, C. S., and M. Lodge. 2006. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 755–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x

- Visser, B. A., A. S. Book, and A. A. Volk. 2017. “Is Hillary dishonest and Donald narcissistic? A HEXACO Analysis of the Presidential Candidates’ Public Personas.” Personality and Individual Differences 106: 281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.053

- Watts, A. L., S. O. Lilienfeld, S. F. Smith, J. D. Miller, W. K. Campbell, I. D. Waldman, S. J. Rubenzer, and T. J. Faschingbauer. 2013. “The Double-Edged Sword of Grandiose Narcissism Implications For Successful and Unsuccessful Leadership among US presidents.” Psychological Science 24 (12): 2379–2389. doi: 10.1177/0956797613491970

- Wilcox, C., L. Sigelman, and E. Cook. 1989. “Some like it Hot: Individual Differences in Responses to Group Feeling Thermometers.” Public Opinion Quarterly 53: 246–257. doi: 10.1086/269505

- Wright, J. D., and M. F. Tomlinson. 2018. “Personality profiles of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump: Fooled by your Own politics.” Personality and Individual Differences 128: 21–24. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.02.019