ABSTRACT

Small primary schools and schools with the lowest number of free school meal (FSM) eligibility are increasingly reliant on voluntary activity for the provision of core services. Significant disparities in where and how this voluntary activity happens risk widening inequalities between schools, especially when policies directly encourage them (and funding cuts necessitate them) to turn to their communities for support. However, we do not know how these differences play out in practice or what the implications might be. Drawing on ethnographic research, this paper explores how voluntary activity undertaken in small rural primaries is facilitated through socio-spatial networks (interpersonal connections rooted in space) and how capital is mobilised (and converted) through these networks. This research revealed how the work of education is carried out through many socio-economic modes, by different people and across a range of spaces, and that this influences the education provided in these environments.

Introduction

Voluntary activity (the uncoerced and unpaid giving of time, talent, money, and resources) in primary schools is increasing. Between 2016 and 2018, ‘the amount schools raise on average has risen from £41 per pupil, per year to £51, increasing to £94 per pupil when we consider PTA [Parent Teacher Association] income’ (Body and Hogg Citation2018, 7). The amount of volunteer time schools receive has also increased from 12.5 minutes per pupil, per week in 2016–21 minutes in 2018 (Body and Hogg Citation2018). Whilst there is much to celebrate about voluntary activity in education, in the context of government funding cuts per pupil of an estimated 8% since 2009 (Sibieta Citation2018, 13), schools are increasingly seeing its use as a necessity rather than a choice, with primary schools becoming increasingly reliant on volunteers and fundraised income to provide education (Body and Hogg Citation2018, 7). Even more worrying is that gaps between schools are widening, with schools in wealthier areas attracting double the amount of volunteer time and money than those in more deprived areas (Body and Hogg Citation2018). Consequently, increasing reliance on voluntary activity is potentially exacerbating already existing inequalities between schools, raising ‘both moral questions about whose responsibility education funding is and social justice concerns about how to ensure a level playing field for all children’ (Body and Hogg Citation2018, 22) in education.

Small schools appear to be attracting the most voluntary activity (Body, Holman, and Hogg Citation2017a, Citation2017b). These schools currently exist in a neoliberal system in which they must market themselves to parents, teach the National Curriculum to complex, mixed-age classes, care for a range of children with different needs, engage with their community and are expected to simultaneously compete and collaborate with similar local schools. All this is to be achieved with significantly lower numbers of staff and children (and funding) than other ‘normal’ sized primaries and with the threat of closure ever-present. Whilst voluntary activity is evident most in small schools, this should not be seen as simply a response to the political environment. Schools have their own unique histories and communities of stakeholders and do not simply react to policy changes independent of their contexts. Therefore, there must also be an understanding of previously existing ‘locally-based support strategies including inter-school co-operation, anti-closure campaigns … voluntary fund-raising’ (Ribchester and Edwards Citation1999, 49) and vital school-community relationships (CofE Citation2014, Citation2018; Hargreaves Citation2017) which have helped sustain the provision of rural education and significantly shape the learning experience in these schools (Hargreaves Citation2009, 59).

In this context, my research aimed to explore voluntary activity in two small rural primaries of differing levels of deprivation in Southeast England through an ethnographic approach. This paper focuses on the role socio-spatial networks play in facilitating (or hindering) voluntary activity in these schools. First, the literature on voluntary activity in small rural primaries is examined, followed by a justification for using ethnography and network mapping to study this field. Findings from my research concerning how geographic and social capital combine to constrain and enable different voluntary activities are then discussed within and between the schools. My paper concludes with a summary of the findings and a discussion of their contribution and implications.

Literature review: voluntary activity in small rural primary schools

Voluntary activity has always been a fundamental and enduring feature of small rural primaries since their founding, often many centuries ago. Church societies and voluntary organisations (or philanthropists) often provided education prior to the passing of the Elementary Education Act 1870 (Ball Citation2021, 66) on a voluntary basis. To this day, 26% of all primary schools in England are Church of England schools (Ball Citation2021, 139). Bell and Sigsworth (Citation1987) recognised the importance of voluntary activity in contributing to the distinct nature and learning experiences in small rural primaries. Their interviews and observations emphasised the familial atmosphere and caring and supportive learning environments of small schools, and the significance of volunteer helpers who listen to children read, teach them French, needlework, cookery, and piano, and support school trips (Bell and Sigsworth Citation1987, 266–267). Similarly, Ribchester and Edwards (Citation1999, 58–59) postal survey of headteachers from 12 rural counties across England and Wales highlighted the role of volunteers in providing vital funding, logistical support with school trips, reading and general classroom support and extra-curricular activities. More recently, a House of Commons debate on small and village school funding discussed the inspiring work of local charities, PTAs, parish councils, local businesses, friends, teachers, and parents who donate their time and money to support their local schools (Hansard (HC Deb), Citation2019, col. 429). Indeed, their small-scale nature means that these schools often occupy a special place in their communities, both symbolically as ‘the heart of the community’ (Bagley and Hillyard Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2019; Bell and Sigsworth Citation1992) and socio-spatially as a meeting place and institution around which community action is built and mobilised.

Considering this literature, it may be tempting to attribute the increase in voluntary activity in small rural schools to the fact that they are particularly well-placed to draw on the social capital (Bourdieu Citation1986) embedded in their local communities and are working from a base of already loyal local support. Indeed, proponents of ‘the Big Society’ (a social policy agenda in the 2010s that encouraged local community action rather than government intervention) were keen to promote this interpretation (Flint Citation2011) which both draws upon and contributes to a romantic pastoral narrative of the English countryside (Murdoch et al. Citation2003, 1). Yet, research has highlighted that whilst this ‘rural idyll’ is often promoted in policy and marketing strategies (Walker Citation2010), it is misconceived (Kvalsund and Hargreaves Citation2009) and indeed, is even a myth (Bagley and Hillyard Citation2011; Hargreaves, Kvalsund, and Galton Citation2009). Where voluntary support is common it is now far from ‘idyllic’ as it is increasingly used to deliver core educational activities, rather than extra-curricular ‘luxuries’ (Body Citation2017; Body, Holman, and Hogg Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Body and Hogg Citation2018; Hansard (HC Deb), Citation2019).

Furthermore, the local contexts in which small rural primaries exist vary greatly. Drawing heavily on Bourdieu’s theory and concepts throughout their extensive 2-year ethnography in two contrasting rural villages, Bagley and Hillyard (Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2019) argue that small rural schools are unlikely to have the capacity to realise ‘the Big Society’ due to the ‘highly differentiated [nature of the] countryside’ (Bagley and Hillyard Citation2014, 63) which prevents the establishment of a stable community ‘core’ from which social capital can be expected to flourish (Bagley and Hillyard Citation2014, 75). They also found that whilst rural headteachers significantly valued strong school-community relationships, the contextual history of these relationships continued to either obstruct or facilitate efforts to promote close engagement (Bagley and Hillyard Citation2019). Moreover, demands on the headteacher’s time and professional pressures associated with managing a small rural school in the current policy context made a focus on developing social capital difficult (Bagley and Hillyard Citation2019, 299). So, small rural schools have access to different levels and types of voluntary activity (and social capital) and realising the skilled, supportive communities envisioned by government policy may not be a realistic option for many. If voluntary activities become an important means through which schools can continue to deliver education, as Body and Hogg (Citation2018) suggest, understanding how this voluntary activity happens in practice, and the experiences and consequences for those involved in different small rural primary contexts, is crucial.

Methodology: ethnography and socio-spatial networks

In attempting to research voluntary activity, and in line with Glucksmann’s (Citation1995, Citation2005) Total Social Organisation of Labour (TSOL) approach, it must be appreciated that ‘volunteer activities are embedded in inter-personal relationships with other volunteers, paid staff, and clients [in this case the children and their parents], as well as in specific organisational programs and settings [education and schools], and broader societal structures and dynamics’ (Hustinx, Cnaan, and Handy Citation2010, 425). Voluntary activities are a form of work (Taylor Citation2016) and within any society, work is ‘divided up between and allocated to different structures, institutions, and activities’ (Glucksmann Citation1995, 67). Moreover, the structural relations and internal organisation within spheres of activity can change in different places, and over time (Glucksmann Citation1995, 71). Ethnography is particularly suited to exploring voluntary activity understood through the lens of the TSOL as it enables the access, observation, and forms of understanding necessary to consider work in all its forms, how it is organised, how activities relate to and are embedded within one another and the implications of these interdependencies on society, social groups, and individuals. It also appreciates the context-dependent nature of voluntary activity within the wider TSOL (Williams Citation2011b) of small rural primaries. Thus, I chose to adopt an ethnographic approach by embedding myself as a volunteer in two small rural primaries of differing levels of deprivation to explore voluntary activity first-hand, spending 7 months in each school community; June-December 2022 and June-December 2023. I volunteered with the school communities up to 4 days a week, taking part in both curricular and enrichment activities and events, recording observations and autoethnographic accounts in fieldnotes (in the moment and later typed up in full), and engaged the children in (arts-based) research. I also conducted interviews and document analysis. The study received ethics approval from the University of Kent and the schools and participants are anonymised.

During the research, the concept of ‘socio-spatial networks’ became apparent as a means to understand how voluntary activity is facilitated and organised. Williams (Citation2011a, Citation2011b) used this concept when developing the TSOL approach to explore how informal, community self-help varies geographically and socially. To analyse the significance of socio-spatial differences between the two schools, I turned to Social Network Analysis (SNA). Although deriving from mathematical graph theory, SNA can be used to qualitatively understand ethnographic network data (Crossley Citation2011). A particular strand of SNA closely aligned with qualitative approaches is Visual Network Research (VNR). VNR uses visualisations (network maps) as both a data collection and presentation tool, and (as with TSOL frameworks) a means of structural analysis of social relationships (Lelong et al. Citation2016). The attractiveness of this method arose from its ability ‘to analyse the (mutual) influence of space on social structures and vice versa’ (Lelong et al. Citation2016, 6) and its capacity to represent complex webs of relationships and their attributes via different symbols, lines, and colour (Scott and Stokman Citation2015). This provided a useful way to visualise the positioning, linkages, and character of the socio-spatial networks of the schools. Concepts such as density (number of connections), intensity (multiple positions and types of connections) and ‘bridge figures’ (those who provide links between (otherwise unconnected) individuals and groups) were also relevant for constructing and analysing these network maps (Donath Citation2020). From this, the influence and consequences of networks (on individual members and their effect on the overall network) could then be explored and compared. Thus, I chose to construct qualitative network maps to illustrate and ground the exploration and comparison of the significance of socio-spatial networks in small rural primary voluntary activity.

Context: the schools and their villagesFootnote1

This ethnography takes place in (the communities of) two small rural primaries of differing levels of deprivation in Southeast England: Applegood (less deprived) and Oakington (more deprived). The two schools are federated with the same executive head (Katherine) and governing body. They are both Church of England schools and are voluntary controlled. gives further details on the characteristics of these schools.

Table 1. Characteristics of the schools.

Applegood Primary is at the centre of its village whose population is concentrated in a small area and where the main road into the village ends at a country estate. The population size has ranged between 390 and 486 during the 1800s and early 1900s and currently is around 390. The ‘lord of the manor’ erected Applegood Primary in 1835. The principal landowning family, now the Spencer’s, has supported the school financially since then and still owns the land on which the school is situated (and most of the village too). The family also donate the use of their woodland, land for parking, and its local gardens free of charge to the school. Applegood Primary also has long-standing connections with village residents (many of whom attended, and whose relatives attended the school).

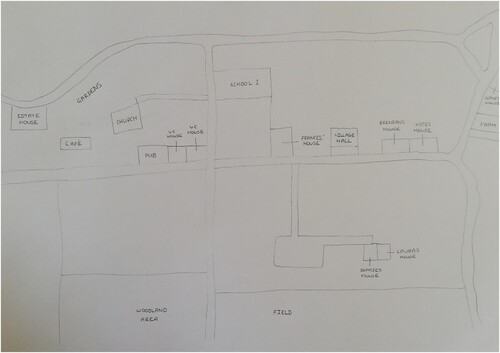

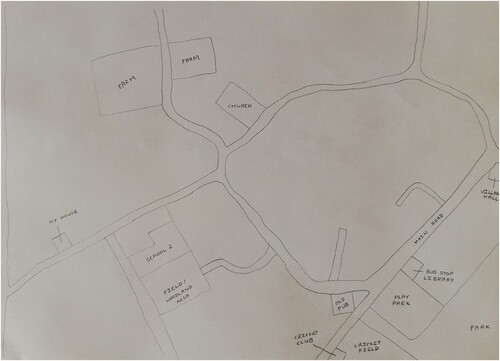

Local facilities in Applegood include the estate house, gardens and café, village hall, church, and pub. As shows, these facilities are very close to the school, making it easy for the school to access and use them and forge links with the people within and around them. It also means the school and its children and staff are visible to the local community everyday as they move between and within these spaces. Many volunteers (including governors) and some staff live in the village. Katherine explained the relationship between the school’s geography and its (historic) sense of community:

[A]t Applegood, the school sits in the middle of what is a quite tight knit local community. The school has historically been involved within the community, the governing board, mostly are people who live in Applegood. And I think, you know, just geographically the location of it, it’s right, literally, right in the village you know, three doors down from the local pub!

In contrast, Oakington Primary is on the outskirts of its large ‘scattered’ village, with its population dispersed across a larger area (4567 acres) than Applegood (1845 acres). Oakington’s population has risen from around 562 in 1801 to around 800 in the 1800s, 774 in 1911 and is currently about 920. In 1801 there were six principal landowners (including the lord of the manor for Applegood at the time and the Spencer family who took over the lordship at Applegood in 1890), of which the Spencer family supported Oakington Primary (erected in 1820). Whilst the Spencer family still own the land on which Oakington Primary is situated, they do not exercise as much influence in Oakington as they do in Applegood (where the title-holding branch of the family live and where their commercial interests are focused). Oakington Primary also do not enjoy the historic connections with village residents that Applegood Primary do, with many former pupils having moved away, and with no staff or governors living in the village itself. Relationships are not helped by the school’s poor reputation locally (linked to a behavioural unit on the school grounds which, whilst separate from the school and now closed earned Oakington an enduring local reputation as a school for ‘naughty’ children).

As shows, the main road through Oakington passes nowhere near the school and so it feels like they are ‘not in the village!’ (Katherine). Consequently, the school community is not visible to locals: ‘it's like the school’s here. And Oakington exists around it. But we're not part of it’ (Katherine). Some residents did not even know there was a school in the village. Whilst the farm and church are nearby (and links have been made), the village hall, local sports ground and a local religious community are further away and not easily accessible, making connections difficult to establish and maintain. The village pub has been closed for many years.

Both Applegood and Oakington have links with their local churches. However, the churches do not have any incumbents (resident priests), meaning ‘there's no priest whose kind of bringing everything together’ (Katherine) and there is no local church representative on the governing body. Thus, it falls to local church members in each village to maintain links with their schools. Applegood has a more stable connection through regular collective worship in their church once a week, facilitated by a local church volunteer. Whilst Oakington use their church for events, they do not (yet) attend weekly worship and do not have a consistent link with local church volunteers.

Despite a shared history of similar (and then the same) philanthropic landowning families, Applegood and Oakington have evolved into quite different villages and have very different geographies and socio-economic profiles. As a result, they have access to different socio-spatial network configurations; the people and groups they can maintain connections with and their location in space. I now move on to discuss my findings on the significance of these socio-spatial differences.

Findings: the socio-spatial networks

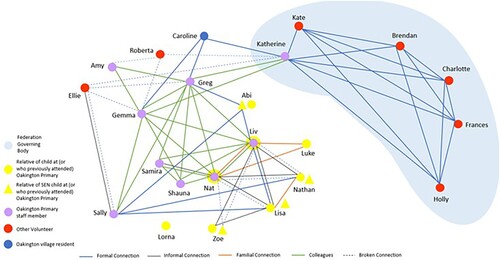

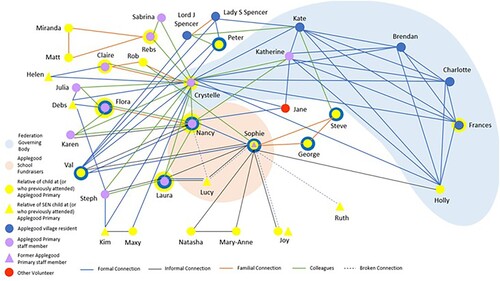

Proximity to the schools and the social links of their communities serve to facilitate or hinder (different forms of) voluntary activity through individuals’ positions and connections in the socio-spatial networks. and below detail the social network maps of voluntary activity for each school. The social connections in these networks include formal connections, informal connections (friendships), familial connections, and work relationships (colleagues). Multiple connections can exist between individuals simultaneously (such as friendships alongside formal and work connections) and individuals can occupy multiple positions within the socio-spatial network (e.g. as a relative, village resident and staff member).

Figure 3. Social network map of voluntary activity at Applegood Primary. Note: Whilst all staff members (purple shapes) are colleagues, I chose to illustrate work relationships (green lines) between individuals who work particularly closely (e.g. in the same classroom or other workplace).

An initial comparison of these network maps shows a smaller network at Oakington than Applegood, with fewer individuals involved overall. The networks at both schools each have areas of density (the number of links individuals have), but Applegood has more individuals holding multiple positions and types of connections in their network (signifying more intense involvement). Oakington has only one local resident in their network, whereas Applegood has many.

I have categorised individuals within the networks as either:

Bridge Figures

Core Volunteers

Peripheral/Episodic Volunteers

Bridge figures provide connections between their school (which they represent as employees, pupils, or parents) and their own personal networks (who would not otherwise support the school were it not for the bridge figure). They hold multiple positions and have the largest number and type of connections but also tend to live close to the school and have personal and/ or longstanding associations and intense involvement. They are key to the flow of information and organisation of activity within their networks. Core volunteers are those who have personal and/ or longstanding connections and intense involvement but do not necessarily live close by (many staff, governors and some parents fall into this category). Peripheral/episodic volunteers are those with less intense involvement, and who tend to live further away from the school (most parents and some community members fall into this category). Individuals may change category throughout their trajectory of involvement with their school, depending on changes to their position and connections within the socio-spatial network over time.

The rest of this section will explore the constellation of voluntary activities that take place in these networks from the point of view of the actors within each category and considering the significance of geographical and social capital to the voluntary activity.

Bridge figures

Sophie is a key bridge figure in Applegood’s socio-spatial network, having been a part of it for many years and holding multiple positions. She used to work as a teaching assistant (TA) at the school but could not afford to remain due to the low salary. However, Crystelle, the head of school, ‘found’ her a job (admin position) with her husband’s company which pays more than Sophie’s previous TA role but also means she has the flexibility to devote time to her position as chair of the Applegood School Fundraisers (ASF) (e.g. leaving early to support school events). Thus, social capital within the school community facilitated a reorganisation of the TSOL so that Sophie’s voluntary activity could continue even though her paid employment ceased. Sophie also lives in Applegood, and her husband works in farming with Kate (the governor who also runs the farm school) and so she has a close connection to the local area. Sophie is also the parent of a Year 1 child (her eldest also attended the school) and is a key member of the parent Whats App group for this class cohort. This gives her ready access to parents she can call upon for voluntary support, whether that be donation-drives or running stalls at fairs. Indeed, digital communication is vital in this network (Donath Citation2020). As Sophie is not often around at pick-up time to talk to other parents in-person, many turn to her online with their questions and concerns. Being able to communicate this way is crucial for a parent cohort who live at a significant distance from the school and from each other (Walker Citation2010), and whose differing work patterns mean they cannot all meet in-person simultaneously. Sophie’s multiple positions mean she is not only a bridge figure between the school and its local community, but also between the school and many of its parents. Her prominence was cemented throughout the research by the amount of people who, when I began to discuss a voluntary activity, immediately said I would need to speak to Sophie.

Living in the village has significant implications for Sophie and Nancy’s (Applegood’s business manager, ASF secretary and another bridge figure) capacity to be involved in voluntary activity for the school. They both regularly meet in school during and outside of school hours, in each other’s homes, or in the pub. Their proximity to each other and the school makes the organisation and completion of voluntary work much easier to manage alongside their other familial and work responsibilities. Sophie even ‘joked’ that if she ever left the PTA, she would have to leave the village, emphasising the strength of proximity as a factor in her voluntary activity. Both Nancy and Sophie are also members of the village hall committee which enables them to gain support from and coordinate school-community events with residents and free or discounted use of the village hall for the school. It also means they are ‘the face of the school’ in the village, making the school constantly ‘visible’ to residents through their embodiment of their ASF roles. These various and multiple connections thus embed Nancy and Sophie in networks where their social and geographic capital are successfully combined in ways which are extremely advantageous for the school in attracting labour, talent, space, and resources.

Key bridge figures at Oakington are Liv and Nat, two sisters who live in a nearby village (2 miles away), are both long-serving TAs (15 years+), and whose children (7 between them) all attended the school. Liv and Nat have an historical connection to the school and, crucially, to its parent community, growing up, parenting, and living alongside many of the schools’ current parents, and supporting their children. They utilise the social capital they have within the parent community to gain support for school events and activities. Indeed, although Oakington do not have a formal PTA, Liv and Nat (alongside Gemma, Oakington’s business manager) are vital ‘informal fundraisers’ due to the amount of time and effort they put into organising and running events (as well as vital marketing and community development work) outside of their contracted hours and job descriptions.

In addition to their own voluntary work, Liv’s husband and Liv and Nat’s eldest children (ex-pupil’s) are also a key part of Oakington through their informal voluntary activity. From making play equipment, unblocking the drains, and climbing onto the roof to retrieve lost footballs, to baking goods for school fairs, and caring for the school guinea pigs during holidays, their familial links with Liv and Nat and personal connections to the school mean that they are often called upon and willingly support the school in a variety of different (often gendered) ways. Thus, staff can also act as bridges between their school and their own families, drawing even more people into voluntary activity to the school’s benefit. Indeed, whilst the family members of school children are often spoken about in the literature (Body, Holman, and Hogg Citation2017a, Citation2017b) this research emphasises that the relatives of staff deserve greater consideration as part of these networks of voluntary activity.

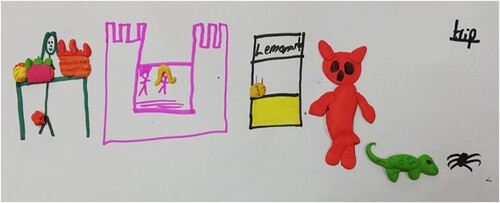

Another often-overlooked group engaging in voluntary activity in these schools are the children themselves. I consider them bridge figures here as they are vital mediators between their school and their own networks of friends and family members, spreading knowledge and awareness, and gaining support. Children are invested with emotional capital by their families, and this can be converted into voluntary activity if influenced effectively. For example, both schools ‘recruit’ children every year to sell raffle tickets and it is the children’s persistent pleas at fairs that encourage relatives to spend their economic capital (and thus contribute to school fundraising). However, children are not actively engaged in these process and practices of fundraising (Body et al. Citation2021) equally in each school. At Applegood, the children unquestioningly put raffle ticket books in their bags and spend their (relatives) money without really considering why or where it goes. In contrast, at Oakington, children are more actively engaged in fundraising practices, selling raffle tickets on the gate (see ), and setting up school fairs. They also have a greater interest and understanding of how fundraised income is spent (see ) and communicate this to their families. Recognising children as active agents in fundraising practices, not only improves the overall effectiveness of asking, but can also enhance children’s critical understanding of how their education happens and why (Ibid). This critical engagement is an important skill and learning experience which could be better developed through both schools’ voluntary activities if children’s roles are better acknowledged and capitalised upon. Oakington are more successful at this currently, than Applegood.

Core volunteers

Where Applegood and Oakington are very similar is in the voluntary efforts of their staff who, in both schools, form the ‘civic core’ (Mohan and Bulloch Citation2012). This is because they go beyond their job descriptions and contracted hours to provide voluntary support (time, talent, money, and resources) on a day-to-day basis and for special events. Whilst this is particularly the case for those who live nearby, the factor of proximity can be overcome if staff members are long-serving and have intense connections.

The relationships between one-to-one TAs for children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) and the parents of the child they are responsible for are particularly vital in both Oakington and Applegood’s socio-spatial network of voluntary activity. Laura, for example, is a TA who lives opposite Applegood Primary. This makes it easy for her to walk her one-to-one Joey and his little sister back to her home and care for them after school until their mum, Lucy, has finished work. Laura also regularly buys snacks and resources for Joey using her own money. Laura’s commitment to her vocation and to Joey motivates her to provide him with consistency of care, regularly meeting up in holidays and forging a close relationship between her family and his. Thus, Laura’s social connection with Joey’s family (social capital) combined with her proximity to the school (geographic capital), facilitate this voluntary activity. This relationship worked both ways, however. Although she could rarely be there in-person, Lucy showed her gratitude to Laura and the school by becoming the PTA treasurer, utilising her cultural capital (accounting skills) to help with school fundraising.

These relationships are not unique to Applegood. At Oakington, Lisa and Nathan’s eldest son (with SEN) had been supported by Nat (and Liv) many years ago and they have retained a strong connection since. This connection motivated Lisa and Nathan to send their other children to Oakington and they are two of the regular supporters in Oakington’s social network. This is especially significant as they live at a considerable distance from the school but still make extensive effort to be involved as often as they can. They volunteer their time, donate resources, are both key advocates for the school and Lisa informally organises and supports events through her informal connections with Liv, Nat, and other parents. Thus, intense personal connections with the school (such as those of SEN parents) can motivate parents to become core volunteers. The strength and warmth of connection can overcome issues of distance, with a significant number of core volunteers (in both schools) living far away from the school but still making the time and effort to be there in-person, or to donate talent and resources to show their support. Capitalising upon and investing in these connections which already exist between specific individuals (initially) for the sake of a small number of children can thus lead to extensive and varied voluntary activity which benefits the rest of the school community too.

Whilst the voluntary activity involved in these relationships bring multiple benefits for those involved, it also speaks to the limits of government funding for (small) schools, such that staff are having to use their own money and time to fill the gaps. It is unfair that the public service of education is being held up by the goodwill and resources of school staff, especially in a cost-of-living crisis, when they are struggling to support themselves and their own families (Postlethwaite Citation2023). Indeed, Applegood lost two members of staff during my data collection due to living costs outpacing their current TA salaries. Thus, these schools are not only struggling to cope with the impact of budget cuts on educational provision, but also face losing staff members at a time when they (and their voluntary activity) are needed most. This emphasises that schools cannot and should not be expected to rely on voluntary activity.

Peripheral/ episodic volunteers

Whilst parents form the core of voluntary activity in many schools, this is not always the case for most parents at Oakington and Applegood. Many of these parents work long hours, many have children with SEN, and many have three or more children to care for. These factors combine to make these parents extremely time-poor. Speaking to parents, many saw roles like PTA or governance as big commitments which they were daunted by or did not feel morally right in taking on if they could not dedicate the time. This suggests parents had a keen awareness (or assumption) of the realities of formal voluntary involvement and chose to avoid the heavy workload and associated responsibility (with it falling to staff instead). In addition, where children in small rural schools are increasingly being drawn from wider catchment areas (Walker Citation2010), parents are increasingly living at further distances from their children’s schools, restricting their physical capacity to be involved. I have therefore classified these parents as peripheral/ episodic volunteers due to their less intense involvement in voluntary activity.

With both schools having time-poor and geographically dispersed parents, their voluntary activity reflects many of the characteristics of ‘micro-volunteering’: activity that is ‘limited in duration and require[s] little or no lasting obligations’ (Heley, Yarker, and Jones Citation2022, 77). Micro-volunteering encompasses speed and convenience with tasks usually taking between 5 and 30 min either in-person or (more often) online (Heley, Yarker, and Jones Citation2022). The examples given can be applied to voluntary activity for the small rural primary. For example, campaigning and communication (school promotion by parents, organising support via WhatsApp), fundraising (parents asking and collecting on behalf of the school) and practical help (parents baking a cake or sourcing and donating prizes). However, micro-volunteering is similar to episodic volunteering, the difference being, the latter is defined more by its repetitive nature (Heley, Yarker, and Jones Citation2022). The voluntary activity undertaken by parents in these schools falls somewhere between the two, as whilst most parents engage in more micro-activities, they are often repetitive (School Fairs are expected every year, with much the same work required each time). Thus, voluntary activity within these small rural primaries parent communities has a distinctive micro-episodic nature due to a lack of geographic (and time) capital.

Whilst smaller acts of voluntary activity may be common for most parents in these schools (excluding the core volunteers) it does not mean they are any less valuable to those involved (Heley, Yarker, and Jones Citation2022, 84). Indeed, parents are often grateful for the limited demands on their time and money but nevertheless being given the opportunity to be involved (donation-drives are particularly relevant here), and staff can reduce their own voluntary workloads by dispersing some tasks (e.g. sourcing prizes) across their parent population. In addition, parents at Oakington spoke about how the PTA which had folded years before had become a toxic and controlling environment of in-fighting and bickering, putting them off wanting to re-form it. The preference is to support events and donate informally (passive voluntary activity). Furthermore, parents and staff spoke about the excellent job Sophie and Nancy at Applegood and Liv, Nat, and Gemma at Oakington did to organise and deliver events (through their active voluntary activity). There was a sense that others were happy to ‘leave them to it’. Thus, time-poor parents engage in passive micro-episodic voluntary activity due to their distance from school, to balance competing demands on their time and to avoid tensions associated with more active commitment. But this leaves school staff to take on the bulk of voluntary work due to a catch-22 situation in which they are successful at organising and delivering events but are also required (due to less active parental support) to do so. Whilst this can be positive for parents, it can have a negative impact on staff.

The future: developing the (Social) networks?

Katherine sees ‘the community’ as the ‘natural source of volunteers’ for her schools, but the current relationships each enjoys with its neighbours (influenced by their geographies and social histories) are very different. Whilst the variances can be partially accounted for by spatial differences, social connections need to be initiated and managed carefully for benefits to result. It is here that the two schools also differ. Applegood school benefits from a willing community who offer their support and local bridge figures who ask for support. In contrast, Oakington school has a lack of willing community volunteers (not helped by its local reputation), bridge figures and parents who live further away, and does not do enough asking (Musick and Wilson Citation2008). Whilst Katherine has made attempts to forge links in Oakington, for example, by attending parish council meetings and getting the school involved in church events, this has not been enough. They need to capitalise on these links by working consistently with volunteers to find ways that they can (continue to) volunteer effectively, and by increasing the school’s presence and activities within the local area. This is easier said than done, however, because, as the executive head of two schools (which, although having small numbers, nevertheless, require the same level of management as any other primary school) Katherine lacks the time to focus on community development, even though she sees it as vital (Bagley and Hillyard Citation2019). As she explained:

it's hard because when there's only me, I can't get to the parish council meetings every month and I can't go and do this and this and this. So that's the one thing that I haven't quite managed to crack yet in terms of getting the school back … in its rightful place within the community.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is not so much the level of deprivation of the schools’ which influence their voluntary activity, but rather the socio-spatial differences between these schools and their communities which constrain and produce the levels and shape the voluntary activity. Proximity to the school (and its visibility in the community) influences both the level and forms of voluntary activity. Living close makes access to the school easier and the schools’ activities more visible on a regular basis, hence the more common involvement tends to be. Indeed, relationships can emerge from proximity, with a small village like Applegood containing many interconnected individuals and layers of relationships, whilst the scattered village of Oakington contains many who are unconnected to one another or to the school. Living closer, also tends to translate into more diverse giving, with the donation of time, talent, money, and resources common, whereas living further away tended to result in the donation of resources and money, rather than time. However, social connections also influence the level of voluntary activity in all its forms and can overcome the issue of proximity if the connection is of significant strength (as with SEN parents and one-to-one TAs). Importantly, it is the initiation of support (via asking) and continued management of relationships that are key to forging and maintaining beneficial connections.

The key contribution of this paper is to fill the gap in the literature in our understanding of the character of voluntary activity in small rural primaries, how and why this differs between contexts and the implications of this. In particular, how the intersection of social demographics and geography constrain and facilitate different levels and forms of voluntary activity. This paper also contributes to the methodological field by showing how social network maps can be used as a tool for understanding and comparing voluntary activity within and between contexts. It should be acknowledged, however, that network maps are only able to capture the network at a specific point in time. Changes to the network cannot be explored through a static map. Nevertheless, using the methodological and conceptual tools of socio-spatial network mapping, this paper has shown how social and geographic capital combine to enable and hinder different voluntary activities. This has important implications for schools in understanding who the various actors in their socio-spatial networks are, where they are positioned, how they are connected (to the school and each other), the nature and strength of these connections, and how these connections can be managed and utilised to the schools’ advantage. They can therefore be a useful overview tool, highlighting areas of the network that are functioning well and which can be better developed. Recognising the children as bridge figures within these networks, for example, is a vital step to improving practices of voluntary activity, and to the children’s own development as philanthropic citizens (Body et al. Citation2021).

Whilst socio-spatial networks are key to the character of voluntary activity in these schools, the current form they take may not be desirable for all members of the network. Indeed, some may wish to increase or reduce their involvement, to be involved differently, or to withdraw completely. Consequently, future work should focus on identifying and understanding issues associated with voluntary activity as an important counterbalance to the often-uncritical view of voluntary activity as inherently positive.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a South East Network for Social Sciences Scholarship (2021–2024). Thank you to all who have commented on my work, including my anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘Contextual information on the villages and their histories was collected from the University of Leicester Special Archive which includes parish records and directories for Southeast England throughout the 19th and 20th centuries’.

References

- Bagley, C., and S. Hillyard. 2011. “Village Schools in England: At the Heart of Their Community?” Australian Journal of Education 55 (1): 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494411105500105.

- Bagley, C., and S. Hillyard. 2014. “Rural Schools, Social Capital and the Big Society: A Theoretical and Empirical Exposition.” British Educational Research Journal 40 (1): 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3026.

- Bagley, C., and S. Hillyard. 2015. “School Choice in an English Village: Living, Loyalty and Leaving.” Ethnography and Education 10 (3): 278–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2015.1050686.

- Bagley, C., and S. Hillyard. 2019. “In the Field with Two Rural Primary School Head Teachers in England.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 51 (3): 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2019.1623763.

- Ball, S. J. 2021. The Education Debate. 4th ed. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Bell, A., and A. Sigsworth. 1987. The Small Primary School: A Matter of Quality. Lewes: Falmer Press.

- Bell, A., and A. Sigsworth. 1992. The Heart of the Community: Rural Primary Schools and Community Development. Norwich: Mousehold Press.

- Body, A. 2017. “Fundraising for Primary Schools in England – Moving Beyond the School Gates.” International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 22 (4): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1582.

- Body, A., and E. Hogg. 2018. A Bridge Too Far? The Increasing Role of Voluntary Activity in Primary Education. Research Gate [Online]. Accessed November 12, 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327284892_A_Bridge_too_Far_The_increasing_role_of_voluntary_activity_in_primary_education.

- Body, A., K. Holman, and E. Hogg. 2017a. “To Bridge the gap? Voluntary Action in Primary Schools.” Voluntary Sector Review 8 (3): 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080517X15090107362612.

- Body, A., K. Holman, and E. Hogg. 2017b. To Bridge the Gap? Voluntary Action in Primary Education. Full Report. [Online]. Accessed June 3, 2020 https://kar.kent.ac.uk/63179/.

- Body, A., E. Lau, L. Cameron, and S. Ali. 2021. “Developing a Children’s Rights Approach to Fundraising with Children in Primary Schools and the Ethics of Cultivating Philanthropic Citizenship.” Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing November: 1–9.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. G. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Church of England (CofE) Archbishops’ Council Education Division and The National Society. 2014. Working Together: The Future of Rural Church of England Schools. Church of England [Online]. Accessed May 14, 2020. https://www.churchofengland.org/sites/default/files/2017- 10/2014_working_together-_the_future_of_rural_schools_web_final.pdf.

- Church of England (CofE) Archbishops’ Council Education Division and The National Society. 2018. Embracing Change: Rural and Small Schools. Church of England [Online]. Accessed May 14, 2020. https://www.churchofengland.org/sites/default/files/2018-03/Rural%20Schools%20%20Embracing%20Change%20WEB%20FINAL.pdf.

- Crossley, N. 2011. “Social Network Analysis (SNA).” In The Cambridge Handbook of Sociology, edited by K. O. Korgen, 134–142. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Donath, J. 2020. Mapping Social Networks. The Social Machine: MIT Press on COVID-19 [Online]. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://covid-19.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/ngsi0mxz/release/1.

- Flint, N. 2011. Schools, Communities and Social Capital: Building Blocks in the ‘Big Society’. Nottingham: NCSL.

- Glucksmann, M. 1995. “Why ‘Work’? Gender and the ‘Total Social Organization of Labour’.” Gender, Work & Organization 2 (2): 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.1995.tb00028.x.

- Glucksmann, M. 2005. “Shifting Boundaries and Interconnections: Extending the ‘Total Social Organisation of Labour’.” In A new Sociology of Work, edited by L. Pettinger, J. Parry, R. Taylor, and M. Glucksmann, 19–36. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Hansard. 2019. Small and Village School Funding 2019-07-17 (No. 663). Accessed May 18, 2023. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2019-07-17/debates/BEFBB005-8AC8-4F49-8D00-CA3EC6430D48/SmallAndVillageSchoolFunding.

- Hargreaves, L. 2009. “Respect and Responsibility: Review of Research on Small Rural Schools in England.” International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2): 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2009.02.004.

- Hargreaves, L. 2017. “Primary Education in Small Rural Schools: Past, Present and Future.” In Life in Schools and Classrooms: Past, Present and Future, edited by R. Maclean, 223–257. Singapore: Springer.

- Hargreaves, L., R. Kvalsund, and M. Galton. 2009. “Reviews of Research on Rural Schools and Their Communities in British and Nordic Countries: Analytical Perspectives and Cultural Meaning.” International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2): 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2009.02.001.

- Heley, J., S. Yarker, and L. Jones. 2022. “Volunteering in the Bath? The Rise of Microvolunteering and Implications for Policy.” Policy Studies 43 (1): 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2019.1645324.

- Hustinx, L., R. A. Cnaan, and F. Handy. 2010. “Navigating Theories of Volunteering: A Hybrid Map for a Complex Phenomenon.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 40 (4): 410–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2010.00439.x.

- Kvalsund, R., and L. Hargreaves. 2009. “Reviews of Research in Rural Schools and Their Communities: Analytical Perspectives and a new Agenda.” International Journal of Educational Research 48 (2): 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2009.02.002.

- Lelong, B., M. Stark, J. Hauck, T. Leuenberger, and I. Thronicker. 2016. “A Visual Network Perspective on Social Interaction and Space: Using net-map and Wennmaker in Participatory Social-Spatial Research.” Europa Regional 23 (2): 5–19.

- Mohan, J., and S. L. Bulloch. 2012. “The Idea of a ‘Civic Core’: What are the Overlaps Between Charitable Giving, Volunteering, and Civic Participation in England and Wales? Third Sector Research Centre.” Working Paper 73(February).

- Murdoch, J., P. Lowe, N. Ward, and T. Marsden. 2003. The Differentiated Countryside. Oxon: Routledge.

- Musick, M., and J. Wilson. 2008. Volunteers: A Social Profile. Bloomington, Ind: Indiana University Press.

- Postlethwaite, S. 2023. Are we Now Experiencing a Cost-Of-Teaching Crisis? Schools Week [Online]. 8th May 2023. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://schoolsweek.co.uk/are-we-now-experiencing-a-cost-of-teaching-crisis/.

- Ribchester, C., and B. Edwards. 1999. “The Centre and the Local: Policy and Practice in Rural Education Provision.” Journal of Rural Studies 15 (1): 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(98)00048-5.

- Scott, J., and F. N. Stokman. 2015. “Social Networks.” InInternational Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, edited by J. D. Wright, 2(22), 473–477. Elsevier [Online]. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.32101-8

- Sibieta, L. 2018. Comparing Schools Spending per Pupil in Wales and England. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/13144.

- Taylor, R. F. 2016. “Volunteering and Unpaid Work.” In The SAGE Handbook of the Sociology of Work and Employment, edited by S. Edgell, H. Gottfried, and E. Granter, 485–501. London: SAGE.

- Walker, M. 2010. “Choice, Cost and Community: The Hidden Complexities of the Rural Primary School Market.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 38 (6): 712–727. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143210379059.

- Williams, C. C. 2011a. “Socio-Spatial Variations in Community Self-Help: A Total Social Organisation of Labour Perspective.” Social Policy and Society 10 (3): 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746411000091.

- Williams, C. C. 2011b. “Geographical Variations in the Nature of Community Engagement: A Total Social Organization of Labour Approach.” Community Development Journal 46 (2): 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsp063.