1. Introduction

Chesbrough explains that innovation has become open through a division of labor. Companies are finding value through the licensing of intellectual property, the development of joint R&D ventures and strategic alliances, or other arrangements to exploit technology outside the boundaries of the firm [Citation1,Citation2]. It can be suggested that we have moved beyond the use of joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, and outsourcing strategies to the usage of novel models of collaboration including: prediscovery consortia where open source strategies prevail; R&D networks spanning disciplines and geographies; centers of excellence focused on key areas of technological and human capital development; public-private partnerships involving new and unexpected stakeholders; crowd-sourcing where shared, public innovation dominates; and web-based collaboration platforms that virtually link stakeholders. The opportunity to employ these emerging models of open innovation is not only determined by organizational structure and size, but equivalently by the evolving need for – knowledge dissemination and shared governance of intellectual assets; access to large scale knowledge based assets such as tools, equipment, and infrastructure; as well as human capital [Citation3]. Allarakhia [Citation4] recently discussed that the triple knowledge lens with its tripartite consideration of intellectual capital drivers namely – human capital drivers, structural capital drivers (including technology based platforms driving knowledge management), and relationship (or social) capital drivers provides a nuanced perspective on open pharmaceutical development [Citation4]. In the current paradigm of ‘big data,’ it is similarly suggested here that the dimensions of collaborations be increasingly viewed from the perspective of intellectual capital assets.

2. Drivers, partner choice, and models of collaboration

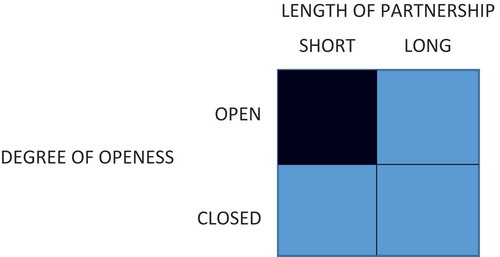

Big pharma, biotech, service providers, academic, and other nonprofit research partners need to consider the dual possibilities of forming new partnerships with once isolated stakeholders and the opportunity of becoming more attractive partners themselves. Ultimately, the partners chosen and open innovation models adopted will vary as a function of partnership objectives as shown in .

Table 1. Understanding the drivers, expanding models of collaboration and knowledge-based outcomes.

Perkmann and Salter [Citation5] provide an insightful framework to assess partnerships. Two dimensions are effective for framing these partnerships – the length of the partnerships and the degree of openness to participation and knowledge sharing [Citation5]. A third dimension can be added – the complexity of the partnership as a function of number of participants. Perkmann and Salter [Citation5] discuss that short-term and long-term partnerships each have their unique goals. Short-term partnerships may have the goal of building new relationships and sourcing new ideas from partners as well as solving near term problems. Long-term partnerships on the other hand may be geared toward longer-term research with large scale or paradigm changing implications including ultimately product development [Citation5]. From a knowledge perspective, participants may be encouraged to deposit knowledge into the public commons. Alternatively, partnerships may be closed with both entry and knowledge access limited and exclusive to partners respectively. When considering the final dimension – complexity of partnership – both short-term and long-term partnerships may involve one-to-one or one-to-many or many-to-many linkages between stakeholders with the opportunity for key partners to drive activities. From an intellectual capital assets perspective, the duration of the partnership will impact not only the aim of knowledge generation and knowledge dissemination, but also the human capital requirements to undertake both discovery and downstream development activities. With the transition from the one-to-one partnership model to one with multiple driving partners, of significance will be the governance of intellectual property for broad or limited access by the public and/or partners respectively. categorizes potential partnerships along these three dimensions and offers examples. These partnerships have been selected on the basis that they utilize unique human capital and knowledge management strategies warranting further discussion.

Table 2. Assessing partnerships: length of partnership, accessibility and complexity.

2.1. Open/short-term collaborations: driving knowledge discovery and dissemination

Precompetitive, upstream research often involves aggregating, accessing, and sharing data from a variety of sources that are essential to innovation, but likely provide little competitive advantage. The Global Oncology Big Data Initiative (GOBDA), Grants4Targets and the Pistoia Alliance each seek to bridge together upstream knowledge based assets and expertise to support precompetitive research. Merck recently announced their collaboration with Project Data Sphere to serve in a joint leadership role for the GOBDA. The objective is to enable the development of an open-access, global, and big data platform (including de-identified clinical trial data from patients) for the oncology community [Citation6]. In the case of Bayer’s Grants4Targets, the opportunity exists for partners to access a multitude of expertise and technology from Bayer. Bayer Grants4Targets encourages research on novel targets and disease related biomarkers in areas of mutual interest. Experienced scientists are nominated as project partners and, depending on the project, financial support, know-how, tools or specific models – including antibodies, small molecule tool compounds, and biobank samples – are provided [Citation7]. Finally, the Pistoia Alliance was first conceived by informatics experts at AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, and Pfizer to bring together human capital in the private and public sectors. The focus is on overcoming the challenges of big data and its application. Knowledge-based assets such as papers, presentations, and project pages are openly shared. Researchers are similarly encouraged to share their ideas through the Interactive Project Portfolio Platform (IP3). In each of these cases, openness is a function of knowledge access and dissemination–with physical knowledge based resources and human capital accessible through supporting platforms [Citation8]. Given the central focus on upstream, discovery-based activities these initiatives are categorized as short-term collaborations.

2.2. Open/long-term collaborations: driving open and collaborative development activities

Discovery research ultimately lends itself to longer term development. Development activities can continue to follow an open policy regarding member entry and more so with respect to intellectual property. The JLABS, Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, the Open Source Drug Discovery (OSDD) initiatives have as their objectives an open policy with respect to intellectual property and the virtual or physical unification of research programs. The JLABS serve as incubators, providing individual entrepreneurs shared lab space and offices, modular lab suites and access to scientific, industry, and capital funding experts in the development of early-stage companies. JLABS is a ‘no-strings-attached’ arrangement. There is no first look, no first right of refusal, and no equity assigned to Johnson & Johnson or Janssen [Citation9]. The Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy is collaboration between immunologists and cancer centers – Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Stanford University, UCLA, UCSF, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and the University of Pennsylvania. The collaboration unifies research programs, intellectual property licensing, data collection, and clinical trials across multiple centers under the umbrella of a single nonprofit biomedical research organization [Citation10]. Finally, OSDD is a global community of students, scientists, researchers, academics, institutions, and corporations committed to the discovery of drugs for tropical infectious diseases in an open source mode. Alongside OSDD are initiatives such as Open Source Malaria, the Mycetoma Open Source project (MycetOS) by DNDi, and the Innovative Medicines Initiative that use an open pharma and open innovation approach with respect to intellectual property and human capital. Of particular interest however with OSDD, is that any resulting drugs are equivalently made available using a generic drug model without the associated intellectual property blocks [Citation11]. The scale and focus on downstream and/or embodied knowledge generation suggests categorizing these initiatives as long-term collaborations.

2.3. Closed/short-term collaborations: defined research through exclusive partnerships

On the opposite end are closed collaborations with entry limited and knowledge access more exclusive. While partners may seek to access varied human capital assets within such partnerships as we see with the Amgen and Boston Children’s Hospital partnership, SpringFire Laboratory Network, and Accelrys Consortia, the goal is on focused research with selected stakeholders. In this partnership model, knowledge based assets is readily accessible by these selected partners. Amgen and Boston Children’s Hospital, recently announced a 1-year research collaboration with the intent to identify novel genes underlying anomalies of pain sensitivity and validating discoveries as possible targets for therapeutics. The partners will combine Amgen’s expertise in genetic target identification and validation with access to patients with abnormal pain conditions through Boston Children’s Division of Pain Medicine [Citation12]. The SpringFire Laboratory Network was unique in representing a network of independent, noncompeting laboratories collectively providing testing offerings to the clinical trial marketplace. Discussions with the network revealed that the affiliated laboratories shared costs and best practices with one another. The SpringFire team in turn, provided support including expert knowledge around project management and clinical trial-specific operations. The Accelrys consortia focused on areas such as catalysis, combinatorial chemistry, and chemoinformatics with the consortia members collaborating in directing research and development activities including the shared exclusive use of the resulting products [Citation13]. It is in these closed collaborations that we see aside from member or knowledge exclusivity, the beginning of the transition from precompetitive research to commercial value generation.

2.4. Closed/long-term collaborations: exclusive long-term development for commercial value generation

Finally, closed partnerships may be aimed at long-term development. In this model, access to human capital and knowledge exploitation by members including any resulting intellectual property, is more likely to be driven by commercial downstream value generation. For example, the Parexel and Sanofi partnership, the Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research, and the Bayer Healthcare-MIT-Harvard collaborations appear to have as their ultimate purpose device and/or therapeutic agent development. The partnership between Parexel and Sanofi, will explore the usefulness of wearables for patients and investigators in clinical trials including patient recruitment, retention, and engagement [Citation14]. In the case of the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research (NIBR), the commercial success of the NIBR arises from the ability of globally dispersed researchers from different disciplines to successfully communicate with each other. Integrated technology and innovative communications tools allow scientists to pool their expertise in real and virtual space [Citation15]. Typical of public-private partnerships, the goal of the Bayer Healthcare-MIT-Harvard collaboration is to jointly discover and develop therapeutic agents that selectively target cancer genome changes. The partnership explores compound libraries and exploits partner screening platforms as well as medicinal chemistry expertise to benefit joint projects. Of importance is that Bayer will have an option for an exclusive license for therapeutic agents [Citation16]. Recently, Bayer expanded the partnership to include cardiovascular genomics and drug discovery. In each of the above partnerships, human capital assets are pooled to enable the transition into the realm of more competitive and commercial value generation.

3. Conclusion

In the selection of partnership model, a number of issues are salient. Short-term versus long-term collaborations must consider the goals to be achieved with well-crafted milestones. Openness in terms of entry and/or knowledge access has increasingly become the norm in the current paradigm of big data – requiring partners to share intellectual and physical capital to generate value from the vast amounts of data being generated. Upstream collaborations focused on precompetitive data generation, biomarker identification, data standard development, and compound screening are moving further downstream into joint clinical trial and drug development.

However, as collaborations move into profit generating activities, participants must consider how to transition from the open to closed model with respect to knowledge access. Such complexities will only increase with the number of participants in any collaboration. Consequently, to successfully transition from the public to private domains will require transparency and explicit rules regarding knowledge management.

4. Expert opinion

In the current paradigm of patient centricity and the inclusion of the patient as a collaborator, managing transparency will become even more salient as patients demand openness during engagement and stakeholders carefully manage the associated regulatory complexities. A variety of patient engagement initiatives are underway across the biopharmaceutical value chain including: the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Patient focused drug development, the clinical trials transformation initiative, and Partners in Parkinson to name a few. These initiatives provide the patient with a voice on the funding of research projects that best meet their health needs, the opportunity to share their experiences with disease management, and provide data on unmet needs – thereby influencing stakeholder priorities and suggesting new engagement opportunities, the ability to codesign clinical trials for optimal participation and experience including provide information on meaningful clinical endpoints, as well as work more closely with regulatory agencies. Patients will seek out these engagement opportunities to openly share their experiences and needs with respect to health and disease management. From a human capital perspective, patients are providing the much needed ‘consumer expertise.’ In terms of knowledge dissemination, it can be expected that patients will be motivated by the broad and open dissemination of any intangible and tangible knowledge shared with stakeholders. Patients will likely share the conviction that the knowledge they provide can further the development of therapeutics and devices that better meet their holistic health needs. Certainly it will be understood that downstream, commercial value creation will require the assignment of intellectual property, but with the goal of broad usage of any intellectual property rather than the creation of intellectual property blockades that ultimately forget the end goal of empowering the patient in his or her health journey. The framework offered in this paper provides an intellectual capital management view to collaboration – with an understanding that the current paradigm of R&D necessitates access to varied expertise and knowledge to create novel patient-centric products.

Declaration of Interest

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chesbrough HW. The era of open innovation. MIT Sloan Manag Rev. 2003;44(3):35–41.

- Chesbrough HW. Why companies should have open business models. MIT Sloan Manag Rev. 2007;48(2):22–28.

- Melese T, Lin SM, Chang JL, et al. Open innovation networks between academia and industry: an imperative for breakthrough therapies. Nat Med. 2009;15(5):502–507.

- Allarakhia M. Open pharmaceutical development: applying the triple knowledge lens. iKnow. 2013;3(2):12–16.

- Perkmann M, Salter A. How to create productive partnerships with universities. MIT Sloan Manag Rev. 2012;53:79–88.

- Kassam Z. Merck joins forces to pioneer global oncology big data initiative. Eur Pharm Rev. 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/news/66713/merck-big-data-initiative/

- Lessl M, Schoepe S, Sommer A, et al. Grants4Targets - an innovative approach to translate ideas from basic research into novel drugs. Drug Discov Today. 2011;16(7–8):288–292.

- Pistoia Alliance. [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from www.pistoiaalliance.org

- Johnson and Johnson Innovation Labs. [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from jlabs.jnjinnovation.com

- Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from www.parkerici.org

- Open Source Drug Discovery. [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from osdd.net

- Amgen. Boston Children’s Hospital collaborate to find pain syndrome genes. Genome Web. 2017. [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from https://www.genomeweb.com/business-news/amgen-boston-childrens-hospital-collaborate-find-pain-syndrome-genes

- Pfizer has joined Accelrys consortium. Scientific computing world. 2007. [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from https://www.scientific-computing.com/news/pfizer-has-joined-accelrys-consortium

- Ricci M. Parexel and Sanofi collaborate on wearables study. PharmaPhorum. 2017. [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from https://pharmaphorum.com/news/parexel-sanofi-wearables

- Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research. [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from www.novartis.com/about-us/our-business/novartis-institutes-biomedical-research

- Broad Institute. [cited 2017 Oct 29]. Available from www.broadinstitute.org