ABSTRACT

Drawing on data from the present and former football players (N = 1026) selected to a national football talent programme at the age of 15, this study explores a model of sport specialisation. We examined three specific aspects of sport specialisation including early football specialisation, participation in youth elite football training environments (i.e. academies) and enrolment in upper secondary football specialisation schools. Antecedents of these sport specialisation factors included gender (i.e. sociocultural), grit (i.e. personality) and perceptions of family finances (i.e. social). Outcomes focused on adult football participation at the age of 21 including elite skill acquisition (i.e. playing elite football) and personal development (i.e. participation in non-elite football). Findings revealed that females were less likely to gain access to elite football training or school specialisation environments. There was also a positive association between grit and participation in elite training environments. In terms of outcomes, players, who got trained in elite training environments during adolescence, were twice as likely to play elite football at the age of 21, while those who attended football specialisation schools were more likely to participate in non-elite football at the age of 21. Early specialisation was not associated with either adult participation outcome. This is one of the few studies to date addressing diverse antecedents and outcomes of sport specialisation factors. Understanding how sport specialisation practices relate to future skill acquisition and personal development can provide guidance for maximising the benefits of youth sport programming.

Highlights

Girls had less opportunity to participate in elite training environments and school football classes.

Early specialisation was unrelated to elite football participation at the age of 21.

Participation in youth elite training increased the likelihood of elite status as an adult.

Need for closer examination of sport specialisation disparities for female players.

Introduction

Sport specialisation represents year-round high-intensity training in a single sport, resulting in the exclusion of participation in other sports (Wiersma, Citation2000). Sport specialisation before age 13, early sport specialisation, is a contested topic of debate (Côté et al., Citation2007; Waldron, DeFreese, RegisterMihalik, et al., Citation2020). Early sport specialisation arguments often reflect complex issues related to skill acquisition, personal development and/or health/injury risks (Mosher et al., Citation2022). Currently, sport organisations, researchers and practitioners alike lack consensus about sport specialisation recommendations (American Medical Society for Sport Medicine, Citation2022; Baker et al., Citation2009; Côté et al., Citation2009). One contributing factor to these disagreements appears to be a lack of robust evidence to guide recommendations (Waldron, DeFreese, Pietrosimone, et al., Citation2020). Continued systematic investigation can help improve understanding of the complexities of sport specialisation and potentially increase consensus on the topic.

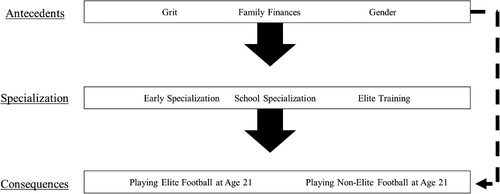

Drawing on data from men and women selected to a national football talent programme at the age of 15, this study explores a model of sport specialisation (see ).

We examine three specific aspects of sport specialisation including early football specialisation, participation in youth elite football training environments (i.e. academies) and enrolment in upper secondary football specialisation schools. Antecedents of these sport specialisation factors include gender (i.e. sociocultural), grit (i.e. personality) and perceptions of family finances (i.e. social). Outcomes focus on adult football participation at the age of 21 including elite skill acquisition (i.e. playing elite football) and personal development (i.e. participation in non-elite football). provides definitions for all study variables.

Table 1. Definitions of all study variables.

Whether or not early specialisation in sport is a prerequisite for elite-level achievement is a topic that has captured a lot of research interest. Two divergent perspectives dominate assumptions about how childhood sport experiences shape future expert performance. The deliberate practice view purposes that adult expertise is a consequence of extensive, goal-oriented and focused training in a particular domain (Ericsson et al., Citation1993). Learning environments emphasise structure and repetition over fun. Proponents of this approach often advocate for early sport specialisation. On the other hand, the deliberate play view stresses early diversification in sports, with sport specialisation occurring in late childhood/early adolescence (Coutinho et al., Citation2016; Côté et al., Citation2007). Learning environments focus on fun and enjoyment.

Findings from a recent meta-analysis study on elite sport performance support the benefits of early sport diversification over early sport specialisation (Barth et al., Citation2022). A similar meta-analysis by Güllich et al. (Citation2022) showed that world-class adult sport performers were more likely to be engaged in early sport diversification during their childhood. However, findings also revealed that youth-led play was not a meaningful predictor of elite performance, suggesting that neither the early specialisation nor early diversification approaches fully explain elite skill acquisition.

Research on sport specialisation in football players specifically reveals that most elite-level players engage in a hybrid of early specialisation and diversification (Ford et al., Citation2009; Ford et al., Citation2020; Hendry et al., Citation2019; Hendry & Hodges, Citation2018; Hornig et al., Citation2016; Zibung & Conzelmann, Citation2013). These studies suggest that almost all high-level football players start in early childhood, around ages 5–6. They spend most of their time in football but do play other sports during childhood and early adolescence. Most elite players, especially males, engage in structured practice settings and have access to academy training during childhood and early adolescence. Intense specialisation generally occurs during adolescence or late adolescence, where access to elite training environments appears to be a key element to playing elite football as a young adult. What much of this research does not address are antecedents associated with different aspects of specialisation and how different aspects of youth specialisation relate to continued participation in football for players who do not become elite (i.e. personal development), which is the pathway for a majority of these players.

Factors that can explain pathways to adult expertise predominately have been directed to sport debut, hours of training and competing and involvement in other sports. Psychological and sociocultural factors related to youth sport specialisation and subsequent skill acquisition and development are understudied in the research. DiSanti and Erickson (Citation2019) suggest that contextual elements are “critical influencers of pathway selection, as well as outcomes and experiences associated with their participation” (p. 2100). Researchers advocate for further empirical research on these types of topics (Mosher et al., Citation2022). Specifically, there are calls for more investigations of patterns leading to the highest senior performance (Barth et al., Citation2022; Ford & Williams, Citation2017), larger and more representative samples (DiSanti & Erickson, Citation2019) and, as most research in the field has focused on adolescent boys or males, more research on differences between gender (e.g. Barth et al., Citation2022; DiSanti & Erickson, Citation2019; Ford & Williams, Citation2017). Curran et al. (Citation2019) report a data gap related to girls in talent development research between 1999 and 2019, suggesting that this omission should be addressed immediately.

Mosher et al. (Citation2022) suggest that investigating conditions, both near influences such as personality and far influences such as sociocultural characteristics, can advance understanding of sport specialisation. Grit is one aspect of personality that may be especially important to understanding sport specialisation and its outcomes. Duckworth et al. (Citation2007) define grit as the degree one maintains focus and interest in important goals even in the face of challenges and adversity. Previous research has shown that grit is positively associated with deliberate practice in children (Duckworth et al., Citation2011). Previous studies have also demonstrated positive correlations between grit and positive aspects of engagement in a variety of different sports including football (Larkin et al., Citation2016). Tedesqui and Young (Citation2017) suggest that athletes with higher levels of grit may have personality-related advantages to the commitment it takes to become an elite athlete. Sociocultural factors related to gender, birthplace population density and family socio-economic status may contribute to understanding sport specialisation (Mosher et al., Citation2022), yet researchers know little about these potential antecedents.

In this study, we explore sport specialisation in male and female football players. Specifically, we use a large sample of athletes associated with the Swedish youth national football programme, examining proposed antecedents and outcomes of early specialisation, upper secondary school specialisation and youth elite training participation. Personality (i.e. grit) and socio-cultural (i.e. perceived family financial status; gender) factors were included as antecedents while skill acquisition (i.e. playing elite football at the age of 21) and personal development (i.e. playing football at the age of 21) factors were included as outcomes (see ).

Method

Participant and procedures

This cross-sectional study uses retrospective questionnaire data from 1026 football players who were selected for district teams between 2001 and 2011 (i.e. players born between 1986 and 1996). Sweden has 24 football districts, which annually select 16 girls and 16 boys that coaches believe have the potential to develop into elite football players the year they turn 15. This study has been approved by the regional ethics review board (2018/68–31). Questionnaires were sent to all 8,000 players who were selected as 15-year-olds by post mail. The final sample, after one reminder (N = 1026), consisted of 396 males (39.6%) and 630 females (63.1%) (see Brusvik, Citation2022). The youngest respondents who answered the questionnaire were 22 years old (born in 1996). Analysis of the response rate (10.0% for boys and 15.5% for girls) shows that, apart from a larger proportion of girls answering the survey (p < .05), the sample was representative of the population regarding the number of players born in respective birth quartiles (for girls, boys and in total, p > .05), the number of players responding from each district (for girls, boys and in total, p > .05) and the number of girls responding from each cohort (p > .05). The sample is, however, not representative of the number of boys and total respondents from each cohort (p < .05). There were higher response rates for participants born in 1986, 1987 and 1989.

Measures

The web-based questionnaire (LimeSurvey) gathered information about personal information (e.g. sex, birth month and education level), previous involvement in football and other sports, reasons to start playing or dropping out of football, personality, socio-cultural background (e.g. family finance, birthplace) and experiences of playing football in different settings.

Based on the framework suggested by Mosher et al. (Citation2022) the following variables were used as antecedent predictors of sport specialisation factors (see ). Personality (i.e. grit), Baker et al. (Citation2009) point at limited knowledge exists about psychological traits in relation to yearly specialisation and early diversification. A meta-analytic review showed that the perseverance of effort facet of grit is closely tied to commitment and performance (Credé et al., Citation2017). We, therefore, used perseverance of effort questions from the Grit-S questionnaire (e.g. I am a hard worker; I finish whatever I begin; I am diligent), which are measured on a five-point scale ranging from (1) not like me at all to (5) very much like me (Duckworth & Quinn, Citation2009).

Aspects of socio-economic status are theorised to influence sport specialisation (Baker et al., Citation2009). We measured perceptions of family finances with four questions: We often went on holiday abroad, I never felt we were short of money, my sport participation was never limited by my family's finances and I felt that we had better finances compared to others. Questions were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5).

Early specialisation was measured with a question where the players filled if they specialised in football (yes/no), and at what age they specialised in football. Part of a youth elite training football academy was measured with a yes/no question, and at what age they started in the academy. Participation in a football class in upper secondary school training football during school hours was measured with a yes/no question.

The Swedish Football Association provided data on the players’ most recent match competition. Players were coded as drop-outs if they did not play a match the year before the age of 21. The players’ club affiliation at the age of 21 served as a proxy to determine whether the players played at an elite or non-elite level. Elite level was based on data for senior elite teams in the two highest divisions (the Swedish Football Association’s definition of elite football) and on the transition to professional football abroad.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all study variables. Frequency counts and percentages were used to describe categorical variables including gender (female = 1; male = 0), early specialisation before the age of 12 in accordance with the developmental model of sport participation (Côté et al., Citation2007) (yes = 1; no = 0), attending a football specialisation upper secondary school (yes = 1; no = 0), attending an elite youth football-training environment such as a football academy (yes = 1; no = 0), playing elite football at the age of 21 (yes = 1; no = 0) and playing non-elite football at the age of 21 (yes = 1; no = 0). Mean scores with standard deviations, minimum and maximum scores and coefficient alpha estimates were included for continuous factors (i.e. grit; perceived family financial status). Gender differences were explored in two main ways. Chi-square (χ²) tests were used to examine gender differences for all categorical variables, while independent t-tests were used to examine gender differences for continuous factors.

The main aims of the study were tested with binary logistic regression. Specifically, a path model was created using Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2015) to simultaneously examine relationships of our proposed model in which all outcomes were binary categorical. Unstandardised beta coefficients with standard errors, p-values, bootstrap 95% confidence intervals and odds ratios (ORs) were reported.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Frequency counts and percentages provide descriptive information on all categorical variables. Specifically, highlights counts and percentages for the overall sample, by gender and population density, as well as missing data. For the overall sample, 10% of the participants reported playing elite-level football, while 70% reported still playing football at the age of 21. Over half of the sample (53%) reported attending an upper secondary football specialisation school. Just over 25% of the sample reported specialisation in football before the age of 12 (i.e. early specialisation), while less than half of the overall sample (42%) participated in elite training environments such as football club academies.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for categorical study variables.

Descriptive statistics for grit and perception of family finances, both continuous variables, are provided in . Mean scores for grit were well above its scale mid-point, whereas mean scores for the perception of family finances were slightly above its scale mid-point, respectively. Variably was fairly low for both factors. Coefficient alpha estimates suggested adequate internal consistency for grit (.83) and perception of family finances (.71).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for continuous study variables.

Gender differences

Chi-square tests results () revealed gender differences for both dependent variables, playing elite-level football at the age of 21, χ² (1) = 4.37, p < .05 and still playing football at the age of 21, χ² (1) = 31.24, p < .001. Females were more likely to play elite-level football at the age of 21 (females 12%; males 8%), while males were more likely to still be playing football at the age of 21 (males 80%; females 64%). Findings on gender differences for independent variables were mixed. The largest gender difference occurred for participation in elite football training academies, χ² (1) = 91.02, p < .001. Males (60%) were more likely than females (30%) to participate in elite training environments. There were also differences in attending upper secondary football specialisation schools, χ² (1) = 5.28, p < .05. Again, males (57%) were more likely to attend these schools compared to females (50%). However, there were no differences between males (29%) and females (26%) in terms of early sport specialisation, χ² (1) = 1.57, p = .21.

Exploration of gender differences in grit and perceptions of family finances were done with independent sample t-tests. Findings revealed differences in grit, t (1024) = −5.56, p < .001, Cohen’s d = −.36, but not family finances, t (1024) = −1.13, p = .26, Cohen’s d = −.07. Females reported higher levels of grit than males (see ).

Binary logistic regression path analysis

Results from binary logistic regression models are presented in .

Table 4. Findings from the binary logistic regression path model.

Grit was a predictor of participating in elite training environments but not early specialisation or school specialisation. Specifically, participants reporting higher levels of grit were 1.39 time more likely to participate in an elite training environment. Gender was a negative predictor for school specialisation and elite training, but not early specialisation. Specifically, the odds of female players attending a secondary school with football specialisation were 25% lower than male players, while the odds of female players participating in elite training environments were 73% lower than male players.

School specialisation was a predictor of playing football at the age of 21. Specifically, participants who attended upper secondary schools that specialised in football were 2.87 times more likely to be playing football at the age of 21 compared to players who did not attend these schools. Attending elite training environments predicted playing elite football at the age of 21 but not playing football at the age of 21. Players who attend elite training environments were 2.09 times more likely to play elite football at the age of 21 compared to players who did not attend elite training environments. Finally, early specialisation did not predict being an elite football player at the age of 21 or playing football at the age of 21. Gender was a predictor for playing elite football at the age of 21 (i.e. positive) and playing football at the age of 21 (i.e. negative). Females were approximately twice as likely to play elite-level football at the age of 21 compared to males. However, the odds of females still playing football at the age of 21 were 53% lower compared to males.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate a model of sport specialisation in Swedish football players. Over a thousand former 15-year-old district team players from all 24 football districts reported information related to their specialisation experiences, personality and socio-cultural factors. Data on participation levels at the age of 21 were obtained from the Swedish Football Association. In general, two major patterns emerged from the results of this study. The first pattern revealed that gender was a meaningful antecedent associated with football specialisation. The second pattern highlighted the relative importance of granting youth football players access to the elite training environment and school specialisation over early specialisation when predicting adult participation levels. In the following paragraphs, we explain study findings in greater detail within the context of sport specialisation research and practice.

Antecedents of sport specialisation

Results showed the frequency of early specialisation was similar for boys and girls. However, girls had substantially less opportunity than boys to participate in elite training environments and school football classes. A closer examination of female players’ specialisation characteristics highlights a greater likelihood of attending football specialisation classes in school (50%) compared to elite training environments (30%) in the Sweden context. Sport specialisation differences based on gender have not been a primary focus in the literature. In fact, many studies use single-sex samples (e.g. Curran et al., Citation2019; Ford et al., Citation2009; Zibung & Conzelmann, Citation2013).

Research addressing gender differences in early sport specialisation has been mixed. Multiple studies have reported no gender differences in early sport specialisation across different sports (e.g. Martin et al., Citation2017; Post et al., Citation2017; Waldron, DeFreese, RegisterMihalik, et al., Citation2020), while other studies show girls are more likely to engage in sport specialisation, suggesting this may reflect involvement in sports where peak performance often occurs prior to full maturation (Peters et al., Citation2022; Rugg et al., Citation2021). However, these studies have generally used samples from the United States.

Gender was also a prominent predictor of sport specialisation factors in the main analysis. Odds ratios revealed that female players were almost 75% less likely to attend elite youth training environments such as football academies and 25% less likely to participate in football specialisation classes in school compared to male players. Despite initiatives directly aimed at enhancing female access to sport including football, there is a long history of gender inequality that continues to create barriers for female athletes (see Coutinho et al., Citation2014; Meier et al., Citation2021).

Female players reported higher levels of grit compared to male players while there were no gender differences related to the perceptions of family socio-economic status. Previous research revealed that young adult females in academic settings reported greater levels of grit compared to males (Kannangara et al., Citation2018). Follow-up qualitative data from Kannangara and colleagues suggest that females’ self-control skills such as time management, self-awareness and task prioritisation helped explain grit differences. However, it is important to note that reports of grit, in this study, were high for both males and females, and possibly as a consequence of that, they are selected as talents (cf. Lund & Söderström, Citation2017).

In logistic regression results, grit was a predictor of participating in elite training environments, but not early specialisation or school specialisation. These findings support the notion that grit, especially the perseverance of effort, relates to higher engagement in football participation (Larkin et al., Citation2016). However, it is not entirely clear based on our findings how grit relates to broader aspects of sport specialisation as it did not play a prominent role in early specialisation or school specialisation. Furthermore, perceptions of family socio-economic status were not a meaningful predictor of any aspect of sport specialisation examined in this study.

Participation outcomes

One of the central findings showed that early specialisation did not increase the likelihood of attaining elite football or playing football at the age of 21. These results are in line with other empirical studies on football (e.g. Hornig et al., Citation2016) and reviews of the field (Coutinho et al., Citation2016) showing that early sport specialisation before 12 years is not a prerequisite for achieving an elite level in adulthood. Early diversification prior to age 12 appears to be more beneficial for attaining elite skill acquisition (cf., Côté et al., Citation2007; Côté & Vierimaa, Citation2014). Similarly, the early specialisation was not related to continued non-elite football participation in young adulthood. Therefore, early diversification may help explain long-term engagement in sport (Côté & Vierimaa, Citation2014). However, as the results show at the age of 21, this was especially true for males as females quit playing football to a much greater extent (males 20%; females 36%). Previous studies have demonstrated that female players were more likely to drop out of football compared to male players (Møllerløkken et al., Citation2015).

Players who participated in elite environments during adolescence were twice (OR, 2.09) as likely to play elite football at the age of 21. However, this type of participation had no relationship with playing non-elite football at the age of 21. Previous research has demonstrated the importance of elite environments for attaining elite football in adulthood (e.g. Rossing et al., Citation2018; Söderström et al., Citation2021). Being in an elite football environment ensures investments over years (cf., Güllich & Cobley, Citation2017) and allows players to receive high-quality coaching and training. Although the results highlight that the likelihood for female players to attend an elite training environment is much lower than for the males, a study of the whole population of district team players showed that females playing in an elite club at the age of 15 increase the odds for playing elite football at the age of 21 (Söderström et al., Citation2021).

Upper secondary school specialisation was not associated with attaining an elite level in football in young adulthood but increased the likelihood (OR, 2.87) to be playing non-elite football at the age of 21. In Sweden the idea with the upper secondary school specialisation is that “every elite athlete should be given opportunities to invest wholeheartedly in their sport, […] to be able to combine the investment with a school education” (CitationThe Swedish Sports Confederation, www.rf.se) in order to achieve international top-level in sport (Lund, Citation2014). The school sport specialisation during what Côté et al. (Citation2007) highlight as the investment years with intense domain-specific training has limited value in terms of reaching the elite level. Whether or not this absent link between school training and adult elite level is a cause of poor quality within the schools or other aspects cannot be discerned in this study. This is a topic for future studies to investigate.

Concluding remarks

Findings provide important insights into sport specialisation within the context of football. This study adds to accumulating evidence contradicting the notion that young athletes must engage in early sport specialisation in order to attain elite skill acquisition during adulthood. The sample in this study is not fully representative regarding the number of boys and total respondents from each age cohort. However, the fact that the sample includes players from all 24 football districts suggests it provides a broad representation of Swedish football.

Results also highlight the need for a closer examination of sport specialisation disparities for female players. Finding ways to improve female access to both elite training and school specialisation environments, which were key pathways for elite and non-elite football participation in adulthood, needs immediate attention and action in order to promote gender equity (cf., Coutinho et al., Citation2014). Finding ways for the school specialisation system to support an elite pathway also needs attention from the Swedish Football Association in future.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the Swedish Research Council for Sport Science under Grant P2012-0023, P2013-0100, and the Swedish Football Association.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Medical Society for Sport Medicine. (2022). Current sport organization guidelines from the AMSSM 2019 youth early sport specialization research summit. Sport Health, 14(1), 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/19417381211051383

- Baker, J., Cobley, S., & Fraser-Thomas, J. (2009). What do we know about early sport specialization? Not much! High Ability Studies, 20(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598130902860507

- Barth, M., Güllich, A., Macnamara, B. N., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2022). Predictors of junior versus senior elite performance are opposite: A systematic review and meta-analysis of participation patterns. Sports Medicine, 52(6), 1399–1416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01625-4

- Brusvik, P. (2022, submitted). Drop-out trajectories and constraints for talented soccer players: A gender and age analysis [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department of Education, Umeå university, Sweden.

- Côté, J., Baker, J., & Abernethy, B. (2007). Practice and play in the development of sport expertise. In R. Eklund, & G. Tenenbaum (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (pp. 184–202). Wiley.

- Côté, J., Horton, S., MacDonald, D., & Wilkes, S. (2009). The benefits of sampling sports during childhood. Physical and Health Education Journal, 74(4), 6–11.

- Côté, J., & Vierimaa, M. (2014). The developmental model of sport participation: 15 years after its first conceptualization. Science & Sports, 29, s63–s69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2014.08.133

- Coutinho, P., Mesquita, I., & Fonseca, A. M. (2016). Talent development in sport: A critical review of pathways to expert performance. International Journal of Sports Sciences and Coaching, 11(2), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954116637499

- Coutinho, P., Mesquita, I., Fonseca, A. M., & De Martin-Silva, L. (2014). Patterns of participation in Portuguese volleyball players according to expertise level and gender. International Journal of Sports Sciences and Coaching, 9(4), 579–592. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.9.4.579

- Credé, M., Tynan, M. C., & Harms, P. D. (2017). Much ado about grit: A meta-analytic synthesis of the grit literature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(3), 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000102

- Curran, O., MacNamara, A., & Passmore, D. (2019). What about the girls? Exploring the gender data gap in talent development. Frontiers in Sport and Active Living, 1, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2019.00003

- DiSanti, J. S., & Erickson, K. (2019). Youth sport specialization: A multidisciplinary scoping review. Journal of Sport Sciences, 37(18), 2094–2105. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1621476

- Duckworth, A. L., Kirby, T. A., Tsukayama, E., Berstein, H., & Ericsson, K. A. (2011). Deliberate practice spells success: Why grittier competitors triumph at the national spelling Bee. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(2), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610385872

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

- Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the short grit scale (GRIT–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Romer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

- Ford, P. R., Hodges, N. J., Broadbent, D., O’Connor, D., Scott, D., Datson, N., Andersson, H. A., & Williams, A. M. (2020). The developmental and professional activities of female international soccer players from five high-performing nations. Journal of Sport Sciences, 38(11-12), 1432–1440. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1789384

- Ford, P. R., Ward, P., Hodges, N. J., & Williams, M. (2009). The role of deliberate practice and play in career progression in sport: The early engagement hypothesis. High Ability Studies, 20(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598130902860721

- Ford, P. R., & Williams, M. A. (2017). Sport activity in childhood. Early specialization and diversification. In J. Baker, S. Cobley, J. Schorer, & N. Wattie (Eds.), Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport (pp. 117–132). Routledge.

- Güllich, A., & Cobley, S. (2017). On the efficacy of talent identification and talent development programmes. In J. Baker, S. Cobley, J. Schorer, & N. Wattie (Eds.), Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport (pp. 80–98). Routledge.

- Güllich, A., Macnamara, B. N., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2022). What makes a champion? Early multidisciplinary practice, not early specialization, predicts world-class performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 6–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620974772

- Hendry, D. T., & Hodges, N. J. (2018). Early majority engagement pathway best defines transitions from youth to adult elite men’s soccer in the UK: A three-point retrospective and prospective study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 36, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.01.009

- Hendry, D. T., Williams, A. M., Ford, P. R., & Hodges, N. J. (2019). Developmental activities and perceptions of challenge for national and varsity soccer players in Canada. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 43, 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.02.008

- Hornig, M., Aust, F., & Güllich, A. (2016). Practice and play in the development of German top-level professional football players. European Journal of Sport Science, 16(1), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.982204

- Kannangara, C. S., Allen, R. E., Waugh, G., Nahar, N., Khan, S. Z. N., Rogerson, S., … Carson, J. (2018). All that glitters is not grit: Three studies of grit in university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01539

- Larkin, P., O’Connor, D., & Williams, A. M. (2016). Does grit influence sport-specific engagement and perceptual-cognitive expertise in elite youth soccer? Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2015.1085922

- Lund, S. (2014). Regulation and deregulation in education policy: New reforms and school sports in Sweden upper secondary education. Sport, Education and Society, 19(3), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.664127

- Lund, S., & Söderström, T. (2017). To see or not to see. Talent identification in the Swedish football association. Sociology of Sport Journal, 34(3), 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2016-0144

- Martin, E. M., Ewing, M. E., & Oregon, E. (2017). Sport experiences of division I collegiate athletes and their perceptions of the importance of specialization. High Ability Studies, 28(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2017.1292894

- Meier, H. E., Verena, M., & Krieger, J. (2021). Women in international elite athletics: Gender (in)equity and national participation. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.709640

- Møllerløkken, N. E., Lorås, H., & Pedersen, A. V. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of dropout rates in youth soccer. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 121(3), 913–922. https://doi.org/10.2466/10.PMS.121c23x0

- Mosher, A., Till, K., Fraser-Thomas, J., & Baker, J. (2022). Revisiting early sport specialization: What’s the problem? Sports Health, 14(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/19417381211049773

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2015). Mplus user's guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Peters, C. M., Hendry, D. T., & Hodges, N. J. (2022). A scoping review in developmental activities of girls’ and women’s sport. Frontiers in Sport and Active Living, 4, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.903886

- Post, E. G., Thein-Nissenbaum, J. M., Stiffler, M. R., Brooks, M. A., & Bell, D. R. (2017). High school sport specialization patterns of current division I athletes. Sports Health, 9(2), 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738116675455

- Rossing, N. N., Stentoft, D., Flattum, A., Côté, J., & Karbing, D. S. (2018). Influence of population size, density, and proximity to talent clubs on the likelihood of becoming elite youth athlete. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(3), 1304–1313. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13009

- Rugg, C. M., Coughlan, M. J., Li, J. N., Hame, S. L., & Feeley, B. T. (2021). Early sport specialization among former national colligate athletic association athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(4), 1049–1058. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546520988727

- Söderström, T., Brusvik, P., Ferry, M., & Lund, S. (2021). Selected 15-year-old boy and girl football players’ continuation with football and competitive level in young adulthood: The impact of individual and contextual factors. European Journal for Sport and Society, 19(4), 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2021.2001172

- Tedesqui, R. A. B., & Young, B. W. (2017). Investigating grit variables and their relations with practice and skill groups in developing sport experts. High Ability Studies, 28(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2017.1340262

- The Swedish Sports Confederation. Elitidrott på gymnasiet – RIG och NIU. www.rf.se/RFarbetarmed/Elitidrott/elitidrottpagymnasiet/.

- Waldron, S., DeFreese, J. D., Pietrosimone, B., RegisterMihalik, J., & Barczak, N. (2020). Exploring early sport specialization: Associations with psychosocial outcomes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 14(2), 182–202. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2018-0061

- Waldron, S., DeFreese, J. D., RegisterMihalik, J., Pietrosimone, B., & Barczak, N. (2020). The costs and benefits of early sport specialization: A critical review of the literature. Quest (grand Rapids, Mich ), 72(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2019.1580205

- Wiersma, L. D. (2000). Risks and benefits of youth sport specialization: Perspectives and recommendations. Pediatric Exercise Science, 12(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.12.1.13

- Zibung, M., & Conzelmann, A. (2013). The role of specialisation in the promotion of young football talents: A person-oriented study. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(5), 452–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2012.749947