ABSTRACT

Background

Although short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) overuse is associated with poor treatment outcomes, data on SABA use in the Middle East are lacking.

Research design and methods

In this cross-sectional study in patients (aged ≥12 years) with asthma, data on disease characteristics and asthma treatments were collected from the Middle Eastern cohort of the SABA use IN Asthma (SABINA) III study. Patients were classified by investigator-defined asthma severity and practice type. Multivariable regression models analyzed the association between SABA prescriptions and clinical outcomes.

Results

Of 1389 patients (mean age, 46.7 years; female, 69.5%), 85.7% had moderate-to-severe asthma and 88.7% were treated by specialists. Overall, 51.3% of patients experienced ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation in the previous 12 months, with 58.2% having partly controlled or uncontrolled asthma. Notably, 47.1% of patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters (considered overprescription). SABA canisters were purchased over the counter by 15.3% of patients. Higher SABA prescriptions (vs 1–2 canisters), except 3–5 canisters, were associated with increased odds of uncontrolled asthma (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

SABA overprescription occurred in almost half of all patients in the Middle East, underscoring the need for healthcare providers and policymakers to adhere to the latest evidence-based recommendations to address this public health concern.

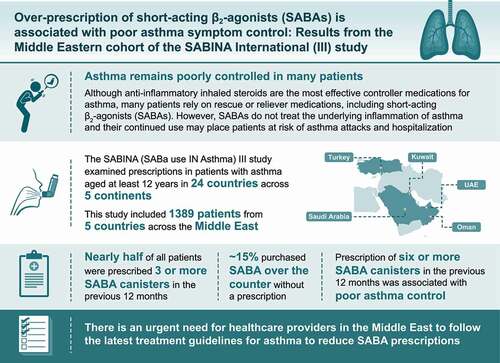

Plain Language Summary

Asthma is a long-term disease that causes inflammation of the airways in the lungs and affects both adults and children. Despite effective medicines, asthma remains poorly controlled in many patients. Inhaled steroids with anti-inflammatory properties are the most effective controller medications for asthma. However, many patients rely on rescue or reliever medications, including short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs), as they provide immediate relief from symptoms. However, SABAs do not treat the underlying inflammation of asthma and their continued overuse may place patients at risk of asthma attacks and hospitalization. The SABA use IN Asthma study, known as SABINA, examined SABA prescriptions in patients with asthma in 24 countries across five continents. As part of this study, data were collected on prescriptions for asthma medications (including SABA prescriptions) and the purchase of SABA over-the-counter (OTC) at the pharmacy without a prescription from 1389 patients aged at least 12 years across five countries in the Middle East (United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey). Nearly half of all patients were prescribed three or more SABA canisters in the previous 12 months, which is above that recommended by asthma treatment guidelines. SABA was also purchased OTC without a prescription by approximately 15% of patients, a majority of whom had already received a high number of SABA prescriptions. Prescription of six or more SABA canisters was associated with poor asthma control. Therefore, there is an urgent need for healthcare providers to follow the latest treatment guidelines for asthma to reduce SABA prescriptions.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Asthma is a heterogenous, chronic respiratory disease affecting more than 339 million people worldwide, with airway inflammation being the primary characteristic pathophysiological feature of the disease [Citation1,Citation2]. Although the reported prevalence of asthma is lower in Middle Eastern countries (4.4%–7.6%) compared with that observed in Western countries (>20%), uncontrolled asthma still imposes a significant economic burden on healthcare systems in the Middle East, primarily through outpatient treatment costs, physician visits, emergency department visits, and hospital admissions [Citation1,Citation3–5]. Moreover, multiple studies from the Middle East have reported that asthma, particularly uncontrolled asthma, is associated with functional impairment, a negative impact on activities of daily living, reduced quality of life, and loss of productivity [Citation6–8]. Furthermore, even patients with mild asthma report a high disease burden, with severe exacerbations in mild asthma accounting for 30%–40% of asthma exacerbations requiring emergency consultation [Citation9]. Consequently, regardless of disease severity, all patients remain at risk of severe asthma exacerbations [Citation10,Citation11]. Therefore, the management of patients with asthma in alignment with evidence-based guidelines is essential to achieve and maintain control of asthma symptoms and to prevent asthma exacerbations [Citation8,Citation10–12].

Historically, short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs) were prescribed for rapid symptomatic relief [Citation13]. However, SABAs have no inherent anti-inflammatory activity [Citation14], and their use without a concomitant inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) may thus place patients at risk of exacerbations [Citation15,Citation16]. Indeed, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) recognizes high SABA use as a potentially modifiable risk factor for exacerbations, even in patients with few symptoms [Citation12]. Therefore, following a landmark update in 2019 [Citation17], GINA no longer recommends SABA monotherapy and instead now recommends low-dose ICS-formoterol as the preferred as-needed reliever for adults and adolescents in GINA treatment steps 1 and 2, and patients in treatment steps 3–5 prescribed ICS-formoterol maintenance therapy [Citation12]. This is a population-level risk reduction strategy; although patients may not perceive or be aware of the short-term clinical benefits of anti-inflammatory reliever therapy, the aim of this strategy is to reduce the probability of serious adverse outcomes [Citation18]. Nevertheless, the failure to treat asthma as a fundamentally inflammatory disease, coupled with the natural tendency of patients to seek symptom relief, has resulted in widespread SABA overreliance and ICS underuse, leading to poor asthma outcomes and increased asthma-related costs [Citation19–23]. The Middle East is no exception, with results from the Asthma Insights and Management (AIM) and Asthma Insights and Reality in the Gulf and Near East (AIRGNE) cross-sectional surveys in the Gulf countries reporting that 76.2% and 55.5% of patients, respectively, had used reliever medications in the previous 4 weeks [Citation3,Citation24]. Notably, only 14.6% of patients in the AIRGNE survey reported use of maintenance ICS medication in the previous 4 weeks [Citation3]. Such findings may explain the suboptimal asthma control observed in several countries in the Middle East, highlighting the need for improvements in patient education and asthma care [Citation6,Citation8,Citation24].

Despite the magnitude of the disease, reliable and recent data on the burden of asthma and the quality of asthma control in the Middle East remain limited. Furthermore, data on prescription patterns for asthma medications, in particular the prevalence of SABA use, are scarce. Such information is essential to implement effective public health strategies for disease prevention and management and to ensure that patients have access to affordable care and asthma medications in alignment with local and global guidelines. However, the absence of comprehensive healthcare databases has limited access to patient-level data and evaluation of trends in the use of medications across this geographical area.

The SABA use IN Asthma (SABINA) III (International) study is part of a series of real-world observational studies that were undertaken to describe SABA prescriptions and associated clinical outcomes among patients with asthma in both primary and secondary care in 24 countries globally, including five countries in the Middle East (United Arab Emirates [UAE], Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey) that fulfilled the logistical requirements of recruiting patients who met the eligibility criteria of diagnosed asthma and could provide a nationally representative sample of how patients with asthma were being managed in each participating country in the Middle East [Citation15]. Crucially, SABINA III overcame the lack of robust longitudinal electronic medication records in a large part of the world by capturing clinical information through electronic case report forms (eCRFs). Here, we report SABA prescription patterns from patients in the five countries in the Middle East cohort of the SABINA III study.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design

The methodology of the SABINA III study has been described previously [Citation25]. In summary, SABINA III was a cross-sectional, multicountry, multicenter, observational study conducted in 24 countries with patient recruitment from March 2019 to January 2020. Here we report results from the Middle East cohort of the SABINA III study, which included patients from the UAE, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. The primary objective of the study was to describe SABA prescription patterns at an aggregated multicountry level in the asthma patient population. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the associations between SABA prescriptions and prespecified asthma-related health outcomes, including severe asthma exacerbations and asthma symptom control in the previous 12 months. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study protocol, which was approved in each country by a central or local ethics committee as per respective national requirements.

2.2. Study population

Patients aged ≥12 years with a documented diagnosis of asthma, ≥3 consultations with a healthcare provider (HCP), and medical records containing data for ≥12 months prior to the study visit were selected and enrolled by HCPs. Patients with a diagnosis of other chronic respiratory diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, were excluded. Signed informed consent was obtained from all patients or legal guardians in accordance with respective country regulations. Retrospective baseline data obtained from medical records and patient data collected during a single visit were entered into an eCRF by HCPs. The study sites were selected using purposive sampling with the aim of obtaining a sample representative of asthma treatment patterns within each participating country by a national coordinator.

2.3. Study variables

All patients were categorized by their SABA canister prescriptions in the 12 months before the study visit. SABA prescriptions were categorized as 0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–12, and ≥13 canisters, with prescription of ≥3 SABA canisters per year defined as overprescription [Citation15]. Prescriptions for ICS canisters were recorded and classified by the average daily dose as low, medium, or high.

Secondary variables included prescriber type (primary or specialist care); investigator-classified asthma severity (guided by GINA 2017 treatment steps [Citation13]; patients on GINA treatment steps 1–2 and 3–5 were categorized as having mild asthma and moderate-to-severe asthma, respectively); asthma duration; and asthma medications in the preceding 12 months, such as SABA monotherapy, SABA in addition to maintenance therapy, ICS (monotherapy as maintenance without long-acting β2-agonists [LABAs]), fixed-dose combination of ICS with LABAs, oral corticosteroid (OCS) burst, long-term OCS treatment for >10 days, antibiotics prescribed for asthma, or SABA purchased over the counter (OTC). Other variables included sociodemographic variables, such as medication reimbursement status (not reimbursed, partially reimbursed, or fully reimbursed), education (primary and secondary school, high school, or university and/or postgraduate education), body mass index (BMI), smoking status, and number of comorbidities.

2.4. Outcomes

Asthma-related health outcomes assessed included asthma symptom control (defined by the GINA 2017 assessment of asthma control – categorized as well controlled, partly controlled, and uncontrolled [Citation13]) and number of severe asthma exacerbations (defined as a deterioration in asthma resulting in hospitalization; emergency room treatment; or the need for intravenous corticosteroids, a single intramuscular corticosteroid dose, or prescription of short-course OCS [defined as OCS typically administered for 3–10 days to treat an exacerbation]) [Citation26].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Patient-level analyses are presented as country-aggregated descriptive statistics for the overall population and for male and female patients. Patient sociodemographics and disease characteristics including asthma treatments (e.g. SABA prescriptions) were described as median (range) for continuous variables and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Missing values were excluded for percentage calculations for descriptive results. A negative binomial regression model was used to analyze the association of SABA prescriptions with the incidence rate of severe exacerbations, whereas a logistic regression model was used to analyze the association of SABA prescriptions with at least partly controlled asthma (reference, uncontrolled asthma). All regression models used a complete-case analysis and were adjusted for country, age, BMI, duration of asthma (continuous variables), sex, smoking status, asthma severity (as classified by investigators), healthcare insurance, education level, and comorbidities based on prespecified variables and potential confounders identified in the sensitivity analyses. Patients with zero SABA prescriptions were excluded from the secondary analysis because details of the alternative relievers used by such patients were not recorded.

A post hoc analysis was conducted to compare sociodemographic and disease characteristics of patients prescribed 1–2 and ≥3 SABA canisters when stratified by their maintenance therapy in the previous 12 months. Chi square and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess categorical and numerical data between the two groups, respectively. All statistical tests were two sided at a 5% level of significance and conducted using the R statistical software, version 3.6.0.

3. Results

3.1. Patient disposition

Of the 1406 patients enrolled, 17 were excluded due to an asthma duration of less than 12 months; therefore, 1389 patients were included in the analysis (). Most patients were recruited from Turkey (n = 579, 41.7%) and Saudi Arabia (n = 509, 36.6%), followed by Kuwait (n = 136, 9.8%), UAE (n = 122, 8.8%), and Oman (n = 43, 3.1%).

3.2. Baseline demographics, lifestyle, and disease characteristics

Overall, the mean age (standard deviation [SD]) of patients was 46.7 (15.5) years. A majority of patients (69.5%) were female and nonsmokers (80.1%; ). Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 present data on patient demographics in male and female patients, respectively. With a mean (SD) BMI of 29.6 (6.6) kg/m2, 33.4% of all patients were overweight and 42.5% were obese according to the World Health Organization BMI classification [Citation27]. Overall, 20.3% of patients had received high school education, while 32.8% had obtained a university and/or postgraduate education. In addition, most patients (91.9%) reported full healthcare reimbursement, with only 5.8% of patients having no healthcare reimbursement.

Table 1. Baseline demographics and lifestyle characteristics by investigator-classified asthma severity and practice type in the SABINA III Middle East cohort.

Most patients were classified as having moderate-to-severe asthma (GINA steps 3–5; 85.7%; ). Overall, 89.7% of patients were treated by specialists and 10.3% of patients by primary care physicians. The mean (SD) duration of asthma was 13.6 (10.8) years, with 51.3% of patients having experienced ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation in the previous 12 months (). Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 present asthma-related clinical characteristics in male and female patients, respectively. Overall, ≥1 comorbidity was reported for 65.5% of patients (). The level of asthma symptom control was assessed as well controlled in 41.8% of patients, partly controlled in 29.4% of patients, and uncontrolled in 28.9% of patients. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were generally similar between patients treated in primary and specialist care ().

Table 2. Asthma-related clinical characteristics in the SABINA III Middle East cohort.

3.3. Asthma treatment in the 12 months before the study visit

Overall, 47.1% of patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in the preceding 12 months, defined as overprescription; over one-third of patients (32.6%) were not prescribed any SABA canisters (). A higher proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months compared with those with mild asthma (51.6% vs 21.4%).

Figure 2. SABA prescriptions in the 12 months prior to study entry according to investigator-classified asthma severity and practice type in the SABINA III Middle East cohort. SABA, short-acting β2-agonist; SABINA, SABA use IN Asthma. *Patients without SABA prescriptions did not report which reliever they were using.

3.3.1. SABA monotherapy

Only 3.9% of patients were prescribed SABA monotherapy, with a median (range) of 2.0 (1.0–42.0) canisters in the preceding 12 months (). Among these patients, 42.3% were prescribed ≥3 canisters in the previous 12 months. Overall, 58.3% of patients in primary care and 36.8% of patients in specialist care received prescriptions for ≥3 SABA canisters. Supplementary Tables S5 and S6 present prescription data on SABA monotherapy in male and female patients, respectively.

Table 3. SABA prescriptions in the 12 months prior to study entry in the SABINA III Middle East cohort.

3.3.2. SABA in addition to maintenance therapy

Overall, 66.7% of patients were prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance therapy in the previous 12 months, with a median (range) of 6.0 (1.0–180.0) canisters (). Among these patients, 71.7% were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters. A higher proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma compared with those with mild asthma were prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance therapy in both primary (65.1% vs 34.4%) and specialist (72.1% vs 38.7%) care. Supplementary Tables S5 and S6 present prescription data on SABA in addition to maintenance therapy in male and female patients, respectively.

3.3.3. SABA OTC

Overall, 15.3% of patients purchased SABA OTC, of whom 53.3% purchased ≥3 canisters and 9% purchased ≥10 canisters of SABAs in the previous 12 months (). A majority of patients (88.7%) who purchased SABA OTC had already received SABA prescriptions (Supplementary Figure S1). Of patients with both SABA purchases and SABA prescriptions, 72.3% had prescriptions for ≥3 SABA canisters and 43.6% had prescriptions for ≥10 SABA canisters in the preceding 12 months. Supplementary Tables S7 and S8 present data on SABA purchases OTC in male and female patients, respectively.

Table 4. SABA OTC purchase in the 12 months prior to study entry in the SABINA III Middle East cohort.

3.3.4. Other prescriptions of asthma medications in the 12 months before the study visit

ICS was prescribed to 9.8% of patients, with a mean (SD) of 6.3 (11.3) (median [range] of 3.0 [1.0–110.0]) canisters. Most patients were prescribed low-dose ICS (48.1%).

ICS/LABA fixed-dose combination as maintenance therapy was prescribed to 91.1% of patients, of whom nearly half (49.4%) were prescribed medium-dose ICS (Supplementary Table S9). For mild asthma, ICS/LABA was prescribed by primary care physicians to 25% of patients (75% as low-dose ICS combinations) and by specialists to 52.8% of patients (52.9% as medium-dose ICS combinations). However, both primary care physicians and specialists prescribed ICS/LABA to nearly all patients with moderate-to-severe asthma (>98%), with nearly half of all patients prescribed the medium-dose combination in both care modalities. Supplementary Tables S10 and S11 present data on prescriptions for ICS-based therapy in male and female patients, respectively.

Among patients prescribed SABA without ICS-based maintenance therapy, a significantly lower proportion of those prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters reported full healthcare reimbursement compared with those prescribed 1–2 canisters (72.0% vs 100.0%; Supplementary Table S12). Among patients prescribed SABA in addition to ICS-based therapy, compared with patients prescribed 1−2 SABA canisters, a higher percentage of those prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters were female (71.9% vs 63.1%), aged ≥55 years (35.4% vs 28.4%), and had ≥1 comorbidity (71.3% vs 60.8%), with a lower percentage of those prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters being current or ex-smokers (12.7% vs 24.8%) and receiving university and/or higher education (29.4% vs 41.0%).

Overall, 48.2% of patients were prescribed a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), with 14.1% and 13.6% of patients prescribed monoclonal antibodies and long-acting muscarinic antagonists, respectively, in the 12 months before the study visit. In addition, antihistaminics, xanthines, and short-acting muscarinic antagonists were prescribed to 6.0%, 3.3%, and 2.6% of patients, respectively. Overall, 33.3% of patients were prescribed an OCS burst in the 12 months prior to study entry. Prescriptions of an OCS burst differed between primary and specialist care, with 35.8% of patients in specialist care prescribed an OCS burst compared with only 12.1% of patients in primary care (Supplementary Table S9).

In addition, a small percentage of patients (3.5%) were prescribed OCS maintenance doses, and 20.4% of patients were prescribed antibiotics for their asthma (19.6% in primary care and 20.7% in specialist care; Supplementary Table S13). Supplementary Tables S14 and S15 present data on prescription of long-term OCS and antibiotics in male and female patients, respectively.

3.4. Association of SABA prescriptions with asthma-related outcomes

In prespecified analyses (Supplementary Figure S2), higher SABA prescriptions (6–9, 10–12, and ≥13 vs 1–2 canisters) in the preceding 12 months were associated with significantly reduced odds of having at least partly controlled asthma, with the exception of 3–5 SABA canisters (p < 0.05; ). However, although higher SABA prescriptions (vs 1–2 canister prescriptions) in the previous 12 months were associated with a numerical increase in the incidence rate of severe exacerbations (with the exception of ≥13 canisters), these results were not statistically significant in this Middle East cohort.

Figure 3. Association of SABA prescriptions with (a) severe exacerbations in the 12 months prior to study entry and (b) level of asthma control assessed during the study visit in the SABINA III Middle East cohort. BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; IRR, incidence rate ratio; OR, odds ratio; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist; SABINA, SABA use IN Asthma. Based on the covariable significance in the models, IRRs and ORs were corrected by country, age, sex, BMI, smoking, duration of asthma, prescriber type, GINA step by investigator, healthcare insurance, education level, and comorbidities.

3.5. Asthma treatments and exacerbations

When stratified by treatments prescribed in the 12 months prior to study entry, most patients prescribed an OCS burst experienced ≥1 severe exacerbation (87.4%), followed by those prescribed antibiotics (80.1%), long-term OCS (79.2%), SABA in addition to maintenance therapy (59%), and ICS/LABA fixed-dose combination (52.9%; data not shown).

3.6. Patient demographics, disease characteristics, asthma-related clinical outcomes, and asthma treatments in the preceding 12 months stratified by sex

In general, patient demographics, disease characteristics, asthma-related clinical outcomes, and asthma treatments in the 12 months prior to the study visit were generally comparable between male and female patients. However, in comparison with male patients, a higher proportion of female patients were obese (46.2% vs 34.0%), had ≥1 comorbidity (71.0% vs 53.0%) and were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in addition to maintenance therapy (74.5% vs 65.6%) and antibiotics (21.0% vs 0.9%). In contrast, a lower proportion of female patients were active/former smokers (12.4% vs 36.9%) and reported university and/or postgraduate education (29.4% vs 40.4%; Supplementary Tables S1–S6, S14, and S15).

3.7. Comparison of results between SABINA Middle East and SABINA III

Overall, patient demographics, disease characteristics, asthma-related clinical outcomes, and asthma treatments in the preceding 12 months were generally comparable between the Middle East cohort and the overall SABINA III population. However, differences between the two cohorts were observed in terms of practice type, patient reimbursement status, asthma severity, and SABA prescription patterns (Supplementary Table S16), which are further described in the Discussion section.

4. Discussion

Results from the Middle East cohort of the SABINA III study in over 1300 patients with asthma provide a wealth of evidence on the approach to asthma management in this diverse Middle East region. Notably, although a majority of patients were treated by specialists and prescribed maintenance therapy, either ICS or ICS/LABA fixed-dose combination, almost 43% of patients were prescribed SABA in excess of treatment recommendations (≥3 SABA canisters/year) and 15% of patients purchased SABA OTC, highlighting the urgent need for improvements in asthma care.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients from the Middle East were generally consistent with those reported in the SABINA III cohort [Citation25]. However, patients in our study were younger (mean age, 46.7 years), which may be explained by an early onset of asthma, given the higher prevalence of childhood and adolescent asthma in Middle Eastern countries [Citation28]. Notably, over three-quarters of patients were classified as overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2). Moreover, almost 43% of patients were classified as obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), with obesity reported in a higher proportion of female patients. This is a higher percentage than that reported in the SABINA III study [Citation25] and the SNAPSHOT observational study conducted in five countries in the Gulf cluster [Citation6], with both reporting obesity rates of over 30%. Although patients with asthma may not be representative of the general population in terms of overall obesity rates, this finding is expected, given the significant burden of obesity in the Middle East, even in young adults [Citation29]. Moreover, the high rates of obesity observed in this study may have been further confounded by the fact that the majority of patients were female with late-onset asthma, which is associated with the ‘late-onset female asthma phenotype’ [Citation30]; indeed, there is growing evidence that obese women are at a higher risk of being diagnosed with asthma than equally obese men of the same age [Citation31]. Although it has been reported that smoking is a major health concern in the Middle East, with approximately 30% of the general population being current or former smokers [Citation32], less than 25% of patients in our study were active or former smokers, with this being particularly low among female patients (12.4%). Notably, the proportion of nonsmokers in our study (80.1%) was higher than that reported in both the SNAPSHOT study (63.9%) and the Assessment of Asthma Control in Adult Asthma Population in the Middle East and North Africa (ESMAA) cross-sectional epidemiological study in four Middle Eastern countries (77.2%) [Citation5,Citation6]. This finding is likely explained by sociocultural factors, specifically the high proportion of female patients in our study, as differences in smoking rates between men and women are well described in this region, with results from the BREATHE study reporting that a significantly lower proportion of women in the Middle East and North Africa are smokers compared with men (13.8% vs 48%) [Citation32]. Surprisingly, although the Middle East has one of the highest prevalence rates for obesity and diabetes [Citation33,Citation34], a majority of patients (82%) in this study had a low comorbidity burden (≤2 comorbidities); however, no additional details were collected to further elucidate this low comorbidity burden.

Overall, almost 90% of patients were treated by specialists; a majority of patients (85.7%) were classified as having moderate-to-severe asthma, with only 14.3% of patients classified as having mild asthma. Although study sites were intended to be representative of healthcare practices in each country, this high proportion of specialist recruitment was similar to that of SABINA III [Citation25]. This discrepancy in recruitment of prescriber type was likely due to inherent challenges commonly encountered in conducting clinical trials at a primary care level, such as insufficient patient recruitment, lack of staff and training, concerns about the impact on the physician-patient relationship, and difficulties with the consent procedure [Citation35,Citation36]. However, despite most patients being under specialist care, the burden of asthma was high, with less than half of all patients (41.8%) classified as having well-controlled asthma and 28.9% of patients having uncontrolled asthma. Nevertheless, the proportion of patients with uncontrolled asthma was lower than that observed in both the ESMAA (41.5%) [Citation5] and SNAPSHOT (44.2%) studies, as assessed by the Asthma Control Test [Citation6]. This finding suggests that specialist care may have improved asthma outcomes, although over half of all patients (51.3%) under specialist care still experienced at least one severe asthma exacerbation in the previous 12 months. Taken together, these findings suggest that asthma symptom control in the Middle East remains suboptimal, indicating the need for educational initiatives targeting both patients and physicians to improve asthma care at both the individual and population levels [Citation5,Citation37,Citation38]. Indeed, results from a systematic review of 51 publications from the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, including Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, and Oman, reported that asthma-related education was the most common determinant of asthma control in 13 publications [Citation39]. As such, The Global Alliance Against Chronic Respiratory Diseases aims to reduce the burden of chronic respiratory disease, including asthma, through implementation of global disease-oriented programs with collaborative efforts between physicians, professional medical societies, patient organizations, and governments across 45 countries, including Turkey and the UAE [Citation40,Citation41].

A high proportion of patients in the Middle East were prescribed SABA treatments, either as monotherapy or in addition to maintenance therapy. However, it is important to note that SABA prescriptions may not necessarily reflect actual usage. Automatic repeat prescriptions, commonly observed in Saudi Arabia, where patients visit their physician every 3 months for routine renewal of prescriptions, may have resulted in an overestimation of SABA use. Furthermore, these results report SABA prescription patterns prior to the GINA update of 2019 [Citation17], which now no longer recommends SABA without concomitant ICS [Citation12]. Nevertheless, these findings clearly indicate that there is a considerable proportion of patients with asthma across the Middle East who are currently not optimally treated according to the GINA 2019 and subsequent 2022 recommendations, even when under specialist care. Interestingly, although it has been reported that male patients are more likely to overuse SABA [Citation42–44], in this study, a higher percentage of female patients were prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance therapy compared with male patients (68.0% vs 63.6%.) Overall, results from our post hoc analysis that compared sociodemographic and disease characteristics of patients prescribed 1–2 and ≥3 SABA canisters when stratified by maintenance therapy revealed some confirmatory observations. Consistent with previous research demonstrating that inadequate healthcare insurance coverage results in consistently poorer quality of asthma care [Citation45], patients who were overprescribed SABA without ICS-based therapy reported lower healthcare reimbursement compared with those prescribed 1–2 SABA canisters without ICS-based therapy. Previous studies have documented that higher socio-economic status is associated with a lower likelihood of excessive and inappropriate SABA use [Citation46]. Unsurprisingly, therefore, patients overprescribed SABA in addition to ICS-based therapy were less likely to have received university and/or postgraduate education, compared with those prescribed 1−2 SABA canisters in addition to ICS-based therapy. Finally, among patients prescribed SABA in addition to ICS-based therapy, a higher percentage of those prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters reported ≥1 comorbidity; it is entirely feasible that such comorbidities may have triggered poor asthma control, potentially leading to SABA overuse [Citation19].

A unique aspect of this study was the collection of data on SABA OTC purchase. Overall, more than 15% of patients from the Middle East, mostly those with moderate-to-severe asthma, purchased SABA OTC in the preceding 12 months, with 53.3% purchasing ≥3 canisters, suggesting either uncontrolled asthma or inappropriate SABA use. This finding is of concern as it has been documented that patients purchasing SABA OTC do not use regular preventer medication and are more likely to avoid visiting their physician for an asthma review [Citation47]. Worryingly, 88.7% of patients who purchased SABA OTC did so in addition to their SABA prescriptions. Although this finding may be attributable to the fact that patients frequently self-treat episodes of symptom worsening by increasing SABA medication [Citation48], patients’ beliefs and attitudes could have also influenced this behavior. Although prescription medicines can readily be purchased OTC in the Middle East, there is a lack of literature relating to self-medication misuse, and the studies that have been published have primarily focused on codeine‐based products, tramadol, topical corticosteroids, antibiotics, and antimalarials [Citation49]. Therefore, this study provides valuable insights into OTC SABA purchases in the Middle East, underscoring the need for patient education on self-management of asthma and an urgent need to drive policy changes to regulate SABA purchase without prescriptions. Moreover, results from our regression analysis showed an association between SABA overprescriptions and lower odds of achieving at least partly controlled asthma – a finding in alignment with results from both the SABINA III cohort [Citation25] and previously published literature [Citation19]. However, despite being previously documented in the literature [Citation42,Citation50,Citation51], the numerical increase in the incidence rates of severe exacerbations with increasing SABA overprescriptions did not reach statistical significance in this cohort of patients, most likely due to the small patient numbers in some of the patient subgroups. This finding will be further explored in future research in the Middle East with larger patient numbers.

Most patients were prescribed maintenance medications, either ICS or fixed-dose combination ICS/LABA. Notably, almost 10% of patients overall were prescribed ICS, of whom almost 51% had moderate-to-severe asthma; this may reflect prescribing practices in the Middle East being discordant with GINA recommendations or erroneous classification of patients by physicians. Moreover, only a mean of 6.3 canisters were prescribed in the previous 12 months. This quantity suggests potential ICS underuse as one canister per month is considered good clinical practice and most patients were not prescribed multiple maintenance treatments. Overall, 91.1% of patients were prescribed ICS/LABA fixed-dose combinations; this finding was expected, given that 85.7% of patients had moderate-to-severe asthma (GINA steps 3–5). Notably, the fact that all patients received some form of ICS maintenance therapy contrasted sharply with earlier studies performed in the Middle East, where patient-reported use of maintenance medications ranged from 14.6% in the AIRGNE survey [Citation3] to 78.9% in the ESMAA study [Citation5]. Therefore, these findings suggest that prescriptions for daily maintenance therapy in a patient population treated largely under specialist care generally conformed to internationally recommended treatment guidelines and may account for the higher rates of asthma control observed in this cohort compared with those in earlier reports [Citation5,Citation6].

Overall, an OCS burst was prescribed to 33.3% of patients and antibiotics were prescribed to 20.4% of patients, presumably for the management of exacerbations as 87.4% and 80.1% of patients with prescriptions for OCS burst and antibiotics, respectively, had ≥1 exacerbation. The relatively high percentage of patients prescribed OCS may, in part, be due to the fact that some physicians prescribe OCS as a standby medication in patients’ asthma action plans [Citation12] in case of a worsening of asthma symptoms [Citation52]. However, while OCS play an important role in the management of asthma [Citation53], increasing OCS prescriptions have been shown to increase the likelihood of adverse events, such as osteoporosis, hypertension, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, highlighting that OCS-sparing strategies are essential to improve patient outcomes [Citation52,Citation54]. Findings related to antibiotic use suggest a lack of familiarity with asthma guidelines as GINA does not support the routine use of antibiotics unless there is strong evidence of a lung infection [Citation12]. Moreover, it is entirely feasible that patients may be routinely prescribed both OCS and antibiotics as part of their asthma care plan, which may not translate into actual use.This multicountry study has some limitations. Prescription data may not always reflect medicines dispensed from pharmacies or their actual use, and therefore, SABA use may have been overestimated. Additionally, this study focused on prescriptions and OTC purchase of SABA canisters, and therefore, data on the potential overuse of oral and nebulized forms of SABA were not captured. In addition, information on asthma phenotypes was not available, which could have provided valuable insights on those patients more at risk of SABA overprescription. Furthermore, differences in local treatment practices and possible erroneous classification may have impacted findings as data were entered into the eCRF by physicians, and a treatment-based approach instead of a symptom-based approach was used for patient classification in accordance with the GINA 2017 report. Moreover, the small number of patients recruited by primary care physicians in this cohort may diminish the generalizability of these findings to the overall patient population treated in primary care in this region. Finally, only five countries from the Middle East were included in this analysis; therefore, results may not be representative of the region as a whole. However, despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess SABA prescription trends in the Middle East, with results demonstrating the need to align clinical practices with the latest evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of asthma.

5. Conclusions

Results from the Middle East cohort of the SABINA III study demonstrated SABA overprescription (≥3 canisters in the previous 12 months) in almost half of all patients. Almost one in seven patients purchased SABA OTC, mostly in addition to their existing SABA prescriptions. Overall, despite most patients receiving specialist care, only two in five patients had well-controlled asthma, with over half of all patients experiencing ≥1 severe exacerbation in the preceding 12 months. These findings highlight an important public health concern and the need for educational initiatives, policy changes to minimize SABA use, better adherence to evidence-based guidelines, and continued improvement in asthma treatment and management in the Middle East.

Article highlights

Nearly half of all patients with asthma were overprescribed SABA (≥3 canisters/year)

SABA was purchased OTC by 15.3% of patients, of whom 53.3% purchased ≥3 canisters

Higher SABA prescriptions (vs 1−2 canisters) increased the odds of uncontrolled asthma

There is an urgent need to reduce SABA overprescription and regulate SABA purchase

Implementation of recent asthma guidelines will address this public health concern

Declarations of interest

A Yorgancıoğlu has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Deva, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Sanofi and honoraria or lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Abdi İbrahim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sandoz, and Sanofi; she currently serves as a GINA board member. K Aksu received consulting fees from Chiesi, Deva, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Sandoz and honoraria or lecture fees from Abdi İbrahim, Acino, AstraZeneca, Deva, GlaxoSmithKline, İbrahim Etem, Novartis, and Sandoz. M Elsayed is an employee of AstraZeneca. M JHI Beekman was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time of the study.

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study protocol, which was approved in each country by a central or local ethics committee as per respective national requirements.

Participatory consent

Signed informed consent was obtained from all patients or legal guardians in accordance with respective country regulations.

Author contribution statement

Ashraf Al Zaabi: investigation, writing, reviewing, and editing; Nasser Busaidi: investigation, writing, reviewing, and editing; Saleh Al Mutairy: investigation, writing, reviewing, and editing; Arzu Yorgancıoğlu: investigation, writing, reviewing, and editing; Kurtuluş Aksu: investigation, writing, reviewing, and editing; Hamdan Al-Jahdali: investigation, writing, reviewing, and editing; Siraj Wali: investigation, writing, reviewing, and editing; Mohamed Elsayed: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing, reviewing, and editing; Maarten JHI Beekman: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing, reviewing, and editing.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (311.7 KB)Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial support was provided by Saurabh Gagangras of Cactus Life Sciences (part of Cactus Communications, Mumbai, India) in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3) and was funded by AstraZeneca.

Data availability statement

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2022.2099841

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global asthma network (GAN) [Internet]. The global asthma report (2018). [cited 2021 Oct 20]. Available from: http://www.globalasthmareport.org

- Song WJ, Kang MG, Chang YS, et al. Epidemiology of adult asthma in Asia: toward a better understanding. Asia Pac Allergy. 2014;4(2):75–85.

- Khadadah M, Mahboub B, Al-Busaidi NH, et al. Asthma insights and reality in the Gulf and the near East. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(8):1015–1022.

- Alzaabi A, Alseiari M, Mahboub B. Economic burden of asthma in Abu Dhabi: a retrospective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;6:445–450.

- Tarraf H, Al-Jahdali H, Al Qaseer AH, et al. Asthma control in adults in the Middle East and North Africa: results from the ESMAA study. Respir Med. 2018;138:64–73.

- Mungan D, Aydin O, Mahboub B, et al. Burden of disease associated with asthma among the adult general population of five Middle Eastern countries: results of the SNAPSHOT program. Respir Med. 2018;139:55–64.

- Tarraf H, Aydin O, Mungan D, et al. Prevalence of asthma among the adult general population of five Middle Eastern countries: results of the SNAPSHOT program. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):68.

- Al-Jahdali H, Wali S, Salem G, et al. Asthma control and predictive factors among adults in Saudi Arabia: results from the Epidemiological Study on the Management of Asthma in Asthmatic Middle East Adult Population study. Ann Thorac Med. 2019;14(2):148–154.

- Dusser D, Montani D, Chanez P, et al. Mild asthma: an expert review on epidemiology, clinical characteristics and treatment recommendations. Allergy. 2007;62(6):591–604.

- Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14009.

- Suruki RY, Daugherty JB, Boudiaf N, et al. The frequency of asthma exacerbations and healthcare utilization in patients with asthma from the UK and USA. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):74.

- Global Initiative for Asthma [Internet]. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention; 2022. [cited 2021 Jun 15 2022]. Available from: https://ginasthma.org.

- Global Initiative for Asthma [Internet]. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention; 2017. [cited 2020 Feb 27]. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports

- Aldridge RE, Hancox RJ, Robin Taylor D, et al. Effects of terbutaline and budesonide on sputum cells and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(5):1459–1464.

- Cabrera CS, Nan C, Lindarck N, et al. SABINA: global programme to evaluate prescriptions and clinical outcomes related to short-acting β2-agonist use in asthma. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(2):1901858.

- Kaplan A, Mitchell PD, Cave AJ, et al. Effective asthma management: is it time to let the air out of SABA? J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):921.

- Global Initiative for Asthma [Internet]. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention; 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 13]. Available from: https://ginasthma.org

- Reddel HK, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. GINA 2019: a fundamental change in asthma management: treatment of asthma with short-acting bronchodilators alone is no longer recommended for adults and adolescents. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(6):1901046.

- Azzi EA, Kritikos V, Peters MJ, et al. Understanding reliever overuse in patients purchasing over-the-counter short-acting beta2 agonists: an Australian community pharmacy-based survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e028995.

- Davidsen JR. Drug utilization and asthma control among young Danish adults with asthma. Analyses of trends and determinants. Dan Med J. 2012;59(8):B4501.

- FitzGerald JM, Tavakoli H, Lynd LD, et al. The impact of inappropriate use of short acting beta agonists in asthma. Respir Med. 2017;131:135–140.

- Hull SA, McKibben S, Homer K, et al. Asthma prescribing, ethnicity and risk of hospital admission: an analysis of 35,864 linked primary and secondary care records in East London. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2016;26:16049.

- Sadatsafavi M, Tavakoli H, Lynd L, et al. Has asthma medication use caught up with the evidence?: a 12-year population-based study of trends. Chest. 2017;151(3):612–618.

- Alzaabi A, Idrees M, Behbehani N, et al. Cross-sectional study on asthma insights and management in the Gulf and Russia. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018;39(6):430–436.

- Bateman ED, Price DB, Wang H-C, et al. Short-acting β2-agonist prescriptions are associated with poor clinical outcomes of asthma: the multi-country, cross-sectional SABINA III study. Eur Respir J. 2022 59 5 2101402.

- Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. on behalf of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force on Asthma Control and Exacerbations. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):59–99.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Obesity and overweight; 2021. [cited 2021 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- Alavinezhad A, Boskabady MH. The prevalence of asthma and related symptoms in Middle East countries. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(3):865–877.

- Alzaabi A, Al-Kaabi J, Al-Maskari F, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and cardio-metabolic risk factors in young men in the United Arab Emirates: a cross-sectional national survey. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2019;2(4):e00081.

- Bel EH. Another piece to the puzzle of the “obese female asthma” phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(3):263–264.

- Ford ES. The epidemiology of obesity and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(5):897–909. quiz 910.

- Khattab A, Javaid A, Iraqi G, et al. Breathe Study Group, Smoking habits in the Middle East and North Africa: results of the BREATHE study. Respir Med. 2012;106(Suppl 2):S16–24.

- Kharroubi AT, Darwish HM. Diabetes mellitus: the epidemic of the century. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(6):850–867.

- Meo SA, Usmani AM, Qalbani E. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the Arab world: impact of GDP and energy consumption. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21(6):1303–1312.

- Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, et al. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(12):1143–1156.

- Taft T, Weir C, Kramer H, et al. Primary care perspectives on implementation of clinical trial recruitment. J Clin Transl Sci. 2019;4(1):61–68.

- Al-Busaidi N, Soriano JB. Asthma control in Oman: national results within the Asthma Insights and Reality in the Gulf and the Near East (AIRGNE) study. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2011;11(1):45–51.

- Alrabiah AL, Elsaid T, Tourkmani A. Determinants of family medicine physicians’ knowledge and application of asthma management guidelines at primary healthcare centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2018;7(5):927–936.

- Noibi S, Mohy A, Gouhar R, et al. Asthma control factors in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and the effectiveness of ICS/LABA fixed dose combinations: a dual rapid literature review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1211.

- Khaltaev N. GARD, a new way to battle with chronic respiratory diseases, from disease oriented programmes to global partnership. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(11):4676–4689.

- Yorgancıoğlu A, Gemicioglu B, Ekinci B, et al. Asthma in the context of Global Alliance against Respiratory Diseases (GARD) in Turkey. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(3):2052–2058.

- Nwaru BI, Ekström M, Hasvold P, et al. Overuse of short-acting β2-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: a nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA programme. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(4):1901872.

- Wang C-Y, Lai C-C, Wang Y-H, et al. The prevalence and outcome of short-acting β2-agonists overuse in asthma patients in Taiwan. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2021;31(1):19.

- Worth H, Criée CP, Vogelmeier CF, et al. Prevalence of overuse of short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA) and associated factors among patients with asthma in Germany. Respir Res. 2021;22 1 :108.

- Ferris TG, Blumenthal D, Woodruff PG, et al. Insurance and quality of care for adults with acute asthma. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;17(12):905–913.

- Tavakoli H, FitzGerald MJ, Lynd LD, et al. Predictors of inappropriate and excessive use of reliever medications in asthma: a 16-year population-based study. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):33.

- Reddel HK, Ampon RD, Sawyer SM, et al. Risks associated with managing asthma without a preventer: urgent healthcare, poor asthma control and over-the-counter reliever use in a cross-sectional population survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016688.

- Partridge MR, van der Molen T, Myrseth S-E, et al. Attitudes and actions of asthma patients on regular maintenance therapy: the INSPIRE study. BMC Pulm Med. 2006;6():13.

- Khalifeh MM, Moore ND, Salameh PR. Self-medication misuse in the Middle East: a systematic literature review. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2017;5(4):e00323.

- Bloom CI, Cabrera C, Arnetorp S, et al. Asthma-related health outcomes associated with short-acting β2-agonist inhaler use: an observational UK study as part of the SABINA global program. Adv Ther. 2020;37(10):4190–4208.

- Stanford RH, Shah MB, D’Souza AO, et al. Short-acting β-agonist use and its ability to predict future asthma-related outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109(6):403–407.

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Globe G, et al. Oral corticosteroid exposure and adverse effects in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(1):110–116.e7.

- Chung LP, Upham JW, Bardin PG, et al. Rational oral corticosteroid use in adult severe asthma: a narrative review. Respirology. 2020;25(2):161–172.

- Price DB, Trudo F, Voorham J, et al. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy. 2018;11:193–204.