ABSTRACT

An increasing number of Extreme Weather Events (EWEs) – including storms and hurricanes – are now being live-streamed on websites such as YouTube. These streams often repurpose existing webcam infrastructure to generate channels that host footage of extreme weather and subsequent damage. Despite evidence of increasing popularity (with streams sometimes generating hundreds of thousands of simultaneous viewers) they are yet to be critically examined. This paper offers the first exploration of these streams by examining how commentors utilise them as opportunities for hazard engagement, sense-making and witnessing. The study analyses data from streams of three events: Hurricane Irma (2017), Hurricane Ian (2022) and the ‘2022 UK Storms’ (Dudley, Eunice and Franklin). In doing so, I evidence that these streams can operate as spaces where attachments and (dis)connections to affected places are imagined and performed. In particular, I draw attention towards viewers who watch streams in their entirety (sometimes 8–24 hours), and whose commitments to the mundaneness of ‘weather watching’ are considered as performances of support and solidarity. The paper concludes by calling for further research that examines the role of informal or ad-hoc virtual spaces that enable (i) engagement with changing places and/or (ii) the sharing/contestation of risk communication messaging.

Introduction

With the advent of video-based technologies with live-streaming capabilities, websites (such as YouTube) and apps (such as Tik-Tok) have provided new opportunities to observe and engage with unfolding significant events. In some instances, these technologies have enabled users to stream and share their experiences of mundane or unusual events (Fang & Cheng, Citation2022; Farinosi & Treré, Citation2014; Slick, Citation2019). In others, internet users have repurposed (or ‘hijacked’) existing streaming infrastructures to create online spaces to witness emerging or unexpected events (Allan, Citation2013). In both, viewers are afforded immediate (often marketed as ‘unfolding’ and ‘uncensored’) views of an increasing number and type of moments across the globe.

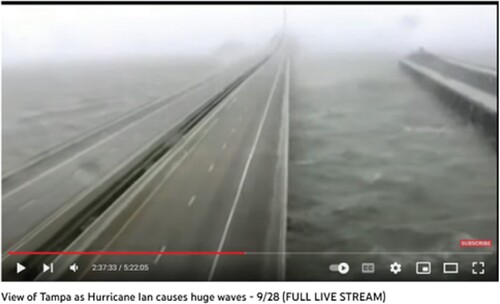

In the contexts of Extreme-Weather Events (EWEs), live-streaming appears to be offering the opportunity to engage with storms and hurricanes in novel ways. Streams in these situations tend to depict places where the ferocity of the event can be easily observed (airports or landscapes with large waves, for example – see ), or where the absence of normality reveals the remarkability of the situation (such as an empty street or highway). Some streams are established by news/media outlets, meaning that live webcam images are paired with satellite imagery and graphics of storm paths – offering new ways of mediating scientific and meteorological concepts. Alternatively, observed as the most common form of live-streamed extreme weather, the repurposing of existing webcams provides illustrations of events without any narration or sound (see ) – creating potential space for alternative risk knowledges, protective decision-making, and sense-making practices to form. At the very least, these technologies are enabling viewers to engage with the ‘unfoldingness’ of extreme weather in ways not previously possible.

Recognising that these streams are affording novel engagements, it is also important to note that they are significant in number, viewers and length. It is now common for incoming storms and hurricanes to have more than 20 streams on YouTube, running for between 3 and 12 h (12 h is currently the maximum live video length on YouTube). In terms of viewership, the most popular of these for Hurricane Ian in 2022, for example, had over 100,000 simultaneous viewers at its peak. Channels depicting Storm Eunice in the UK, meanwhile, had over 40,000 live-viewers – numbers which grew rapidly after waves crashing against a promenade in Brighton were displayed live on national news.Footnote1 Streams are also sometimes available after the event, either in full or in shortened versions that focus on dramatic moments. As such, videos are often widely watched after the event (in 2021 were 5 archived videos of/from streams of Hurricane Irma on YouTube with more than 2 million views). Live-streams, thus, appear to be mechanisms that engage audiences both during the post the EWE – raising important questions for the knowledges, networks, and experiences that are being fostered during engagement. The observation of Storm Eunice also indicates potential relationships between the consumption of traditional news media and subsequent engagement with live-streams.

Although much is already known about the diverse motivations for live-stream consumption in contexts such as video-games (Hu et al., Citation2017; Sjöblom & Hamari, Citation2017) and tourism (Deng et al., Citation2019), no attention has been paid to how live-streams mediate experiences of extreme events or the motivations for viewership. While some work has examined the role of video technologies in shaping disaster experience – including the role of self-recorded video in shaping disaster memory (Slick, Citation2019) – these studies have not focused specifically on the networks of interaction that form through the consumption of visual materials. Additionally, it is also worth noting that, while there is a strong theme of exploration around nascent hazard communities in geographical and disaster risk management literatures, these studies generally rely on text-based conversations (such as on Twitter/X), rather than emerging communities forming over visual depictions of the EWE (David et al., Citation2016). Thus, despite the increasing prevalence of live-streamed EWEs and the focus on hazard event engagement through a variety of technologies, live-streams have yet to receive critical attention.

In response, this study exists as an exploratory account of the encounters and interactions that form within comment spaces on live-streams of EWEs. It recognises that comment-functions enable emergent communities to form/be performed but, additionally, the experiences and perspectives shared within these spaces (including information about hazard and risk dynamics) can be observed and consumed even by those not actively commenting. Studying the interactions within these spaces therefore offers crucial insight into new mediums of risk information sharing. The study is underpinned by two key questions. First, it questions the spatial geographies of engagement with live-stream comment spaces. Research into engagement with unfolding natural hazard events on social media platforms suggest that virtual spaces are used by both those experiencing the event and those geographically removed from it (Takahashi et al., Citation2015; Zahra et al., Citation2017). However, no research exists to understand whether the visual element of live-streaming shapes who is contributing to discussion around these events – as well as the proximity of those consuming it. Second, it examines the emotional geographies of engagement with live-streams by questioning how comment spaces are used to imagine and perform connections to the affected region. Specifically, the paper positions streams as spaces of performative witnessing – where the visual witnessing of extreme weather appear to produce nascent communities formed around the sharing of memories of past events, visits, and connections, and where watching is framed as performances of empathy and sacrifice.

Methodology

The study focuses on live-streams of three EWEs: Hurricane Irma (a 2017 event that devastated parts of the Caribbean and mainland United States), Hurricane Ian (a 2022 event which resulted in deaths in Cuba and the United States), and the 2022 ‘UK Storms’ (Storms Dudley, Eunice and Franklin which affected the United Kingdom within the same week of February). Events were selected due to their predicted significance and widespread uncertainty about impacts, both of which fuelled online engagement: radical changes in the predicted paths of Irma (Magnusson et al., Citation2017) and Ian (Bucci et al., Citation2023) caused speculation as to expected impact, while the UK Storms saw three named storms hit different parts of the UK within a week – the first time this had happened since 2015 (Met Office, Citation2022). The uniqueness of, and uncertainty around, these events appeared to increase the number of channels sharing live footage.

For each event, the three streams on YouTube with the highest number of viewers in the lead up to event peak were selected (usually 24 h before landfall – although this was affected by time-differences). The rationale was to select channels that were popular in preparation phases, where landfall/peak was expected but not imminent. The intention was to observe discourses about perceptions of risk and event magnitude in a period where the impact of the event was not yet immediate. Sampling by viewership resulted in a range of stream formats being encountered (see ) – including those of Hurricane Ian depicted in and . Most displayed a single location streaming from a pre-existing webcam/streaming device, although three provided either split-screen footage of multiple cameras or switched between cameras (generally on 5minute intervals). Streams displaying rolling news coverage were noted during all events, however these were excluded from this exploratory study as (i) footage often cut away from the event to focus on reporters in studios, and (ii) comment content was often moderated or restricted by channel staff.

Table 1. Webcam footage sources and types analysed in the study.

The study focuses specifically on the comments left by viewers in these streams.Footnote2 Of the 9 streams analysed, 14,322 comments were left by 5,177 unique accounts.Footnote3 The number of comments analysed is higher than most studies examining YouTube comment spaces and reflects footage focused on unfolding events of national or global importance generating higher-than-normal audience engagement (Zhang, Citation2022). All streams were at least in part watched live to provide senses of emerging themes and to additionally ensure comments were captured (as some streams do not allow live comments to be seen/accessed after streaming has concluded). In addition to live gathering of text, comments from available concluded streams were then scraped using a Python script. Analysis involved thematically organising comments (using both inductive and deductive codes) in NVivo.Footnote4 In total, at the date of analysis, 1.8 million viewers consumed content from the selected streams – with a total of 65 hours of video footage.Footnote5

Live-streaming and witnessing

This study is situated at the intersection of two lines of emerging academic inquiry. The first examines how live-streaming enables new forms of witnessing of unfolding events, while the second explores how digital spaces shape engagement with, and understanding of, extreme environmental events.

In regards to the first, literature on live-streaming has engaged with the ways in which the production, consumption and sharing of video has enabled opportunities to witness unfolding events – both everyday (Zhang, Citation2019) and extraordinary (Thorburn, Citation2014). The act of witnessing has been considerably transformed by the growth and affordability of digital technologies. The production of spaces and opportunities to witness is now open to individuals who can instantly and independently produce and circulate streams through digital channels. Witnessing has also become a strategic social practice which transforms the viewer and their network as they are afforded opportunities to take active part in the unfolding event (Martini, Citation2018b) – where the sociality and interaction that go alongside watching generates forms of ‘active spectatorship’ (Haimson & Tang, Citation2017). Also of note, the archiving of streams on websites such as YouTube (Luo et al., Citation2020) has created a multitude of possible temporalities and proximities through which events can be witnessed: individuals can be witness to live transmissions (present in time and removed in space), witness to historical events (present in space and removed in time), or witness to recorded events (removed in space and time) (Kyriakidou, Citation2015). In these senses, witnessing goes beyond the act of ‘seeing’ or ‘watching’ – rather it implies active, and sometimes retrospective, participation in the events presented on the screen, either through direct shaping of streamer actions/attention or in the nascent communities formed through its consumption (Andén-Papadopoulos, Citation2014; Martini, Citation2018a)

The idea of witnessing has been extensively used to examine live-streaming in documenting, mobilising, and extending civic action. A key feature of the nexus of between sharing and mobilisation is the deliberate sharing of live imagery from protest events in a manner that invites ‘ … personalization, appropriation, and collaboration’ (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2013, p. 196). Specifically, devices with recording and streaming capabilities – most commonly, smartphones – are understood as gendering forms of ‘connective witnessing’ that emerges when ‘citizens and/or participants contribute to the flow of information from … catastrophe by producing and distributing images on a large scale’ (Mortensen, Citation2015, p. 1394). Fang (Citation2022) for example, highlighted how live-streams during the 2019 protests in Hong Kong fostered participation amongst those outside of Hong Kong, allowing for forms of ‘emotional involvement and discursive participation’ (p. 9) that rendered the protests ‘cyberurban’ in nature. Similarly, accounts of farmer protests in India (Mahanta & Bharadwaj, Citation2022), Occupy (Thorburn, Citation2014), and racial justice protests in the U.S.A. (Kalmoe et al., Citation2022) have all examined the production of affective politics through live-streaming that work to create, maintain and engage publics. Streaming can thus have both internal functions (functioning as a way for participants to communicate and share experiences internally) and external logics (external communication to gain public visibility, recruit more followers, and raise financial, political, and moral support).

Witnessing extreme environmental events

The second branch of relevant research relates to the witnessing of EWEsFootnote6 on digital platforms. EWEs are defined as moments or periods in which weather, climate, or environmental conditions – including temperature and flooding – occur outside of expected ‘normal’ levels (McPhillips et al, Citation2018). An effect of the growth of digital space and associated technologies is that users start perceiving their own private spaces, activities and interactions as potentially filmable or shareable during out-of-the-ordinary events (Martini, Citation2018a). There has been a noted rise in the recording and streaming of flood experiences in particular (Fichet et al., Citation2016), including widely-shared instances of fatalities while individuals were using smartphones to live-stream flooding (Dillane, Citation2023). The sharing of experiences on social media during events has resultantly generated significant research related to how digital spaces contribute to event (often disaster) knowledges, networks, and socialities. Broadly, these accounts speak to practices of witnessing in three ways:

First, the increased sharing of information and experiences on social media provides monitoring functions that enable both lay publics and crisis managers (as witnesses) to provide support and redirect resources during extreme events (Alexander, Citation2014). Researchers have noted the values of information shared through platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to contribute to situational knowledge about the unfolding event (Fichet et al., Citation2016; Vieweg et al., Citation2010). In these instances, individuals and organisations can be witness to live requests for support or, in the case of lay publics, actively participate in emerging networks of support or solidarity (Houston et al., Citation2015). The case of the 2010–11 Christchurch (New Zealand) earthquakes, for example, demonstrates how the sharing of personal videos and images of the event on social media fosters networks of response. There, an emergent ‘Student Volunteer Army’ – formed of university students – utilised social media to identify need and dispatch aid and support (Dickinson, Citation2018). In such instances, new opportunities for witnessing are thus framed as opportunities for sharing, listening and action (Crawford, Citation2009).

Second, there is evidence that social media provokes and enables forms of professional and citizen reporting that contribute to both official and counter narratives of events (Saka, Citation2017). The immediate and democratic nature of live-streaming (i.e. many people have access to streaming devices) offers the potential for ‘on-the-ground’ perspectives that facilitates and amplifies different kinds of evidence. Streaming devices enables citizen-reporting that provide first-hand accounts without media intermediaries (Allan, Citation2013) and that makes possible the creation of alternative discourses that can both remain independent of, or connect to, ideologies operating across different scales (Saka, Citation2017). In the hazard and disasters contexts specifically, research has focused on the disruptive potential of on-the-ground accounts – where citizen-produced video and streaming is used to disrupt official narratives of event dynamics and impact (Lovari & Bowen, Citation2020) – as well as the potential of emergent digital spaces in sharing misinformation and myth (Bird et al., Citation2012; Muhammed & Mathew, Citation2022). Here, visual imagery is argued to carry a weight of perceived authenticity that can work to supplement or contest other forms of data provided by official sources (Dowling et al., Citation2018).

Third, cross-cutting the prior two strands, researchers have drawn attention to practices of sense-making that take place through citizen-produced visual media. Examinations of sense-making focus both on how emergent spaces of witnessing (i) enable new modes of emotional and psychological engagement with changing places (Alexander, Citation2014; Takahashi et al., Citation2015), and (ii) how these spaces shape individual risk knowledges and behaviours (Karami et al., Citation2020; Wang & Zhuang, Citation2018). Illustrating both, Fichet et al. (Citation2016) examine the rise of online ‘discussion streams’ after extreme weather events – sometimes hosted by an individual in the affected area (who may have built a following through streaming or posting during the event), or by geographically distant internet celebrities whose following is formed around discussing topical global events. These spaces – which often see affected individuals contributing their experiences and self-generated imagery – represents the emergence of new forms of collective witnessing as participants make sense of, and interpret, the event (Young et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

In the remainder of the article, the comment spaces of live-streams from Hurricane Irma, Hurricane Ian and the 2022 UK storms are analysed. Discussion focuses on how the distinctly visual and unfolding nature of EWE streams leads to performances and imaginations of solidarity and connection with the affected/depicted places. Such practices of witnessing appear to be underpinned by the banal content of streams – where the lack of catastrophe, and the anticipation of it, shapes discussion in several noticeable and important ways, including in a specific group of viewers who commit to watching the entire event. The argument, therefore, is that these spaces are not simply sites of disaster voyeurism but are instead home to nascent networks of solidarity and information sharing that warrant further exploration.

The following sections proceed by first discussing the geographies of (dis)connection of commentors in these spaces (‘geographies of engagement’), how the banality of weather-watching shapes viewer engagement and discourse (‘banality and anticipation’) and, finally, how viewership of streams is framed as a form of solidarity amongst ‘committed viewers’ (‘watching as solidarity’).

Geographies of engagement

In this study, three distinct groups of commentors were observed – all of whom enacted different forms of connection and attachment to the places affected by the EWE.Footnote7 The first of these were commentors not currently in close proximity to the EWE, but who had previous connection or attachment to these locations. For these viewers, the streams became ways to express and perform historic connections to the places potentially affected by the unfolding EWE. This most commonly manifested through messages of support that referenced these the nature of the connection. For example, in a stream showing a Brighton promenade during the 2022 UK storms, a commentor noted that, that’s where my husband and I got engaged!!! Sending love from New York xx (18/02/22). On another stream, a beach shown during Hurricane Ian, was referenced as a place where (different) users … walk[ed] up and down every day on [their] working holiday so [they] really feel for everyone affected (28/09/22), swam everyday as its 5 min from [their] childhood home. [They] know many of the people around here (28/09/22), and where [they] got asked by [their] hubby to marry him! There’s a lovely restaurant owner who [they] hope are okay! (29/09/22). While it is likely that many of these commentors are drawn to the streams precisely because of their familiarity with the places, the streams subsequently enable historic connections to form the basis of expressions of solidarity and support (later discussed in more detail).

While the above group engaged with live streams as a way of performing historic attachments and connections, a second group of commentors were characterised by an acknowledgement of distance from the affected regions. Although it is common for viewers and commentors on YouTube streams to be geographically remote (Thelwall et al., Citation2012), posters on EWE streams often deliberately noted their location and disconnection as a way of signalling a geographical diversity in support. For example, in a comment reflective of sentiments expressed across all streams and all events in the study, a viewer of Hurricane Irma stated love to everyone from your brothers and sisters in Chile (10/09/17). These comments followed a typical structure of the ‘sending’ or ‘sharing’ of ‘love’, ‘hugs’, ‘prayers’, ‘support’, ‘wishes’, or ‘thoughts’ followed by a sharing of location where these emanate from. In one instance, in the most viewed stream of Hurricane Ian, support was ‘sent’ from 47 countries in the duration of the video – including a 5minute period where 19 posters shared their location in a series of consecutive comments (including one stating to be in Antarctica). It appears these posters are deliberately acknowledging geographical distance and lack of proximity in order to develop a sense of the global community of support and solidarity.

The third theme of engagement relates to those using live-streams to share experiences of previous disasters and EWEs. A significant amount of discourse in all three events – particularly before landfall/the peak of the event – focused on the likelihood of the storm/hurricane meeting the strength and damage predictions in official government communications. A common element of these discussions was the sharing of memories of previous events to either (in)validate these predictions (well, I know the tree in my yard bent backwards during the last [hurricane]. It’s not close to doing that now … but lets give them the benefit of the doubt – Irma, 08/09/17), share messages of the need to help others (I got beat during [Hurricane] Gert. This gonna be worse … help your family – Irma, 10/09/17), or reflect changing climate patterns (Storm after storm after storm. I lose my house now others lose [theirs]. Its all getting real – Ian, 29/09/22). Additionally, in some instances, these posters used their experiences to contest comments about hazard dynamics and predictions (further detailed in following sections) – establishing themselves as voices of authority and creating noticeable hierarchies in the communities that form in comment spaces. These brief observations alone point towards the need to more effectively understand how memory is invoked and shared in these spaces, particularly as recognition grows of the relationship between how extreme weather is understood and remembered determines future risk behaviours (McKinnon, Citation2019; Palutikof et al., Citation2004; Walshe et al., Citation2020).

Banality and anticipation

The second element of importance is how the banal nature of live-streams shapes practices of engagement in the EWE context. Notably, the banality of live-streams has been highlighted in other streaming contexts. In those instances, banality is generally framed through discourses of boredom – observed through live-streams both in the sense of viewership as a way of escaping boredom and the fascination in observing ‘boring’ activities (sometimes referred to as ‘non-content’) (Zhang & Li, Citation2022). Illustrating the latter, Zhang (Citation2019) – in a study of Chinese platform Zhibo where many streamers film themselves completing household chores – noted that viewers often described the content of streams as ‘meaningless’, ‘containing nothing’, and ‘quintessentially boring’ (p. 201). This non-content, however, is argued to disrupt the logic of the spectacle by exacerbating it and subsequently serves as a stimulus for discussion and interaction amongst viewers. In these situations, the Zhang argues that the sociality of the streams ‘overwhelms the content itself’ as ‘as viewers [discuss] issues completely irrelevant to the … footage’ (p. 220). It is important to recognise, then, that live-streams have already been theorised as entangled in a kind of boredom economy, where banality serves as a backdrop for escape from the everyday, potential networking and interaction, and a voyeuristic observation of other spaces.

Similar to Zhibo, the content of most EWE streams could be classified as mundane – or, at least, routine – for most, if not all, of the time they are accessible. Streams generally depict the slow development of weather and other environmental conditions, meaning that in the build-up the scene is relatively routine (a bad weather day, perhaps) and the slow-developing nature of weather demands thorough observation of clouds, trees, or waves over time in order to perceive changing conditions. Even during peak periods ����� where content might be most ‘spectacular’ – the unfolding impacts may be difficult to observe as the fixed-locations of videos means they may not capture the focal point of the event, the backdrop (such as a beach with no trees) makes severity difficult to observe, or infrastructure limitations (such as water on the lens) decreases visibility significantly. Additionally, some or all of an EWE may take place during darkness, making visibility and comprehension difficult. It is thus important to note that viewers and contributors to these streams are only rarely observing catastrophic conditions.

Given that many streams are established many hours before a hurricane or storm makes landfall, the banality of weather watching plays an important role in viewer behaviour and interaction. During these initial periods – often over periods of 4-8 h – viewers become attuned to micro-changes in the environment that only become discernible through acute observations of relatively static landscapes. At these times, discussion across all EWEs in the study circulated around commentors aiming to be the first to draw attention to small changes ( … tree on the left definitely moving more now – Ian, 28/09/22) or contesting the claims made by others (you’re wrong. Tree moving same amount. Stop creating panic – Ian, 28/09/22). Specifically, a theme across all events was contestations around shifting wave magnitudes, where claims were often made as to whether waves were getting larger (anyone else using measuring their comp[uter] to see that the waves are in fact getting bigger – Irma, 10/09/17), the event had made landfall/reached its peak (that’s the highest wave we’ve seen so far. I’m calling it: ITS [the hurricane] HERE! – Irma, 10/09/17), or whether it was in fact decreasing in ferocity ( … that wave clearly isn’t the biggest so far. See the wet line on wall … obviously made earlier – Eunice, 18/02/22).

In the period before the event begins or makes landfall, and in the drive to first observe environmental changes, conversation also dwells upon what can’t be seen: the yet-to-be-observed and the absence of normality. These discourses of absence appear to be characterised by perceptions of what elements the storm/Hurricane will contain (wind, rain, waves) and, given the publicised expected magnitude of the event, the absence of conditions that deviate from normal weather conditions. For example, in a series of consecutive comments during Hurricane Irma, one viewer noted:

Waves still the same. No sign of a storm there.

Wind blowing but not stronger than before.

Sky not even dark. No black clouds or anything bad. Maybe its a way off yet. (10/09/22)

For others, the absence of normal behaviours and rhythms produces a melancholy driven by a sense of impending destruction. While the aforementioned exchanges saw absence dictate a suspicion in official government narratives, for others notions of absence and lull contribute senses of impending catastrophe. For example, in the lead up to Hurricane Ian, one viewer noted that the relatively calm seas and empty beaches represented … the calm before the big storm. Take the peace in and remember it because we don’t know what it will be like later. [I’m] not expecting to recognise this by next week (18/02/22). In another instance, a live stream of an empty city street during Hurricane Irma became poignant by both the absence of normality and extreme weather: So so so [eery]. I go down that street every day and now that whole street just sitting empty. Noone to be seen and no wind or rain yet wow (10/09/17). For these commenters, embodied connections to place presents itself in the suffering of absence, and even more so in the threat of its destruction (Frers, Citation2013). Focus shifts to imagined and remembered impressions of what used to fill the absence – where one aspect of the anticipation of the event is the feeling of the loss that is yet to come (Edensor, Citation2008).

Watching as solidarity

Finally, the study observed – across all events – groups of commentors whose viewership was characterised by the intention to watch the event continuously for the entirety of the stream. One commentor, in a stream of Hurricane Ian, termed their intention of prolonged engagement committed viewing.Footnote8 This committed viewing appeared as an important element of the performance and expression of solidarity with those affected by the EWE. For these viewers, the idea of taking time to watch and engage with the unfolding event was characterised as sticking it out with those affected. An integral component of these practices was the recognition that observing the slow and mundane build-up of the event was an important part of showing solidarity with affected people/places as it demonstrated a commitment of thought and time to the idea that damage could be avoided. For example, during Hurricane Irma, one poster stated, I refuse to stop watching until I know that this is all over and all the people are safe. Watching and waiting (10/09/17). The same poster later emphasised their commitment to watching a perceived lack of hurricane development by adding that, I’m here with the waves since this began [3 h earlier]. There’s a pleasure in their nothingness. In the same stream, another commentor noted they … still [feel] like nothings happening. God I pray for everyone that it stays that way (10/09/17). These excerpts reflect not just a sense of continued consumption as form of support and solidarity, but also a continued hope that conditions remained mundane, boring, or undramatic. Although it could be assumed that viewers are generally drawn by the inevitable spectacle of catastrophe (performers of a digital disaster voyeurism – Lisle, Citation2004), participation by these viewers is defined by its commitment to, and desire for, the anti-spectacle.

In streams of Hurricanes Ian and Irma specifically, a group of committed watchers emerged whose intentions were to follow streams from beginning to end. Alongside the earlier discussed conversations about the mundanity of the event build up, these committed viewers tended to announce themselves and their intentions and, subsequently, form connections with viewers with similar intentions. In streams for both Hurricanes Ian and Irma, commentors asked [who’s] here for the long haul? #solidarity (Ian, 28/09/22), who gonna camp out with me and keep an eye on things? (Irma, 09/09/17), and does anyone want to stay and pray with us till the end of this?Footnote9 (10/09/17). Connections made in these early stages were often carried through the entirety of the stream – including frequent reference to in-jokes and observations made many hours earlier.

Specific to these committed viewers was the sharing of acknowledgements of what they had forgone in order to stay attuned to the EWE. These acknowledgements work to develop senses of solidarity and community through shared recognitions of self-sacrifice. Notably, these are developed collaboratively over several posts, by multiple contributors weaving together different actions and scales of sacrifice in order to develop a communal sense of solidarity amongst committed viewers. For example, one commenter, who earlier had noted they lived in an adjacent but not affected area to Hurricane Ian, stated, … looking good out there maybe the worst of it has [passed]. I didn’t go to work today [because] I’m stressed and I sit here the whole day just hoping it doesn’t get anyone (28/09/22). After 10 min, another commenter noted that they had shifted a work deadline because work doesn’t matter when lives are at stake. Later, another viewer who had previously engaged with both of these commentors posted saying, I’m lucky I haven’t had to give up as much as [accounts of previous posters]. All I can say is that I’m here on my day off hoping for the best x – a message which then stimulates a number of replies containing only love heart emoticons from other posters. These messages work to build not just a sense of solidarity amongst committed viewers, but also senses of intimacy and connection that form the basis of a nascent watching community.

Practices of committed viewing also both implicitly and explicitly exclude others engaging with the streams, and also create perceived hierarchies of technical hazard knowledge. Some committed viewers – in expressing their commitment to solidarity through prolonged viewership – expressed moral judgements about those gazing at the unfolding catastrophes either more fleetingly, or who join at specific times (e.g. after the stream had been shown on TV news). Specifically, present in streams of all three events (but most significantly in the case of Hurricane Irma, which had received more global coverage) were critiques from longer-watching commentors about the disaster voyeurism being performed and expressed by others – especially as viewership rapidly increased during peaks of the event.

The critiques from committed viewers towards others focused on two specific elements. First, comments sometimes concentrated on dispelling or disproving the claims made by new posters about the dynamics of the event. These comments worked to insinuate that committed viewers were more authoritative on both the hazard dynamics and the way in which the event was unfolding. In a stream of Hurricane Ian, which displayed a traffic camera webcam of a main road/highway, a commenter noted the signs swaying in the wind (wow look at the exit sign blowing so hard. Gonna cause so much damage when that falls – 28/09/22). In response, a long-term viewer (86 comments over four hours) posted hun the signs have moved for hours. They designed that way. Hurricane can’t rip that sign out. It wont fall and don’t go around hoping it will. Echoing the idea that committed viewing was connected to technical and event-specific knowledge, in another stream of Hurricane Irma, a group of committed viewers often directed questions about the hurricane to one specific user who was noted to, [have] been here from the start and knows first hand how bad this could be (08/09/17). Second, comments from some inferred that committed watchers were practicing forms of care and solidarity that made them distinctive from other viewers. For example, one poster during Hurricane Irma (who posted over 150 comments over a 7 h period), caused conflict by suggesting that ‘care’ could only be observed watchers engaging for a longer period of time:

If you TRULY CARE you must stay with Florida for every minute from the beginning to the end. Only those are the ones who TRULY CARE. The HOUR OF NEED IN FLORIDA IS A WEEK OF NEED. (10/09/17)

[please] don’t turn up and expect drama. Be here because you care for the people. [Too] many of you want to see death. I am here [because] I want to see life prosper. (10/09/17)

Conclusion

This paper investigated the forms of witnessing that take place through engagement with live-streamed EWEs – with specific focus on Hurricane Irma, Hurricane Ian, and the 2022 UK Storms. The study questioned (i) the spatial geographies of engagement, and (ii) the emotional geographies of engagement by examining how comment spaces were used to imagine and perform connection to, and solidarity with, affected areas. The study was the first to examine live-streamed EWEs on YouTube. It is also the first to investigate the comment spaces of live-streams depicting EWEs specifically, as well as the first exploration of the spatial geographies of engagements with live-streams.

In speaking to the above questions, the study drew attention to the ways commentors articulated (dis)connection to the areas affected by the event. Many commentors appeared to be drawn to streams through personal historical connections to the places depicted – and comment boxes thus became spaces where memories of place formed the basis of messages of support and solidarity. In other instances, memories of past events (both in the affected area and in other places) formed the basis of social interaction. Notably, the study examined how, in addition to the use of live-streams as a space to share messages of support, viewership was imagined as a performance of solidarity itself. In these periods of banal weather watching prior to landfall/event peak, discussion focused on the yet-to-be-observed and the absence of normality – and discourses of melancholy, expected loss, and hope for affected places were documented. In highlighting these themes, the study drew attention towards practices of ‘committed viewing’ – where, across all three events, evidence was found of viewers who committed to watching events and streams in their entirety. Comments from these viewers exhibited a desire for the anti-spectacle (i.e. a hope that imagery remained calm), notions of personal sacrifice (i.e. what was being forgone to perform solidarity through viewing), and also worked to establish knowledge hierarchies (i.e. who, in the stream comments, had the authority to comment on event dynamics and development).

As a result, the study calls for further innovative and urgent research that examines the behavioural and emotional impacts of live-streamed environmental events. Four avenues of potential research emerge most obviously from this novel study:

First, ever-evolving digital technologies and interfaces are generating new mediums through which risk communications are being shared, negotiated and contested. From the findings of this study, some of these nascent spaces appear to hold potential to overcome the pitfalls of traditional modes of risk communication. This includes the challenges of engaging disinterested audiences (Renn, Citation2020) and the repeated call to diversify from risk ontologies that stimulate confusion and disengagement (such as maps and graphs – Rosenbaum & Culshaw, Citation2003). However, research opportunities remain to examine what kinds of (mis)information are communicated through such spaces, as well as considerations of how (or should) such spaces be utilised and managed by risk communicators and government bodies. At the very least, the spontaneous and ephemeral emergence of spaces that enable mass consumption of hazard imagery and information demands urgent consideration.

Second, the behavioural impacts of the consumption of visual and/or streamed material are yet to be assessed. Recent hazards research has begun to evidence how alternative spaces of risk communication and engagement (such as video games) can influence both risk attitudes and behaviours. Recognising that, like video games (Mani et al., Citation2016), live-streams also enable experiential encounters with hazards, future research must examine how the consumption of such material shapes hazard knowledges and decision making. Doing so will require not only the negotiation of complex ethical and data management issues (including working with channel operators and moderators), but will also demand the design of novel methodologies that can access viewers and examine both attitude and behavioural impacts of stream consumption.

Third, nascent spaces of streaming and engagement are generating new opportunities for people to document, observe, and make sense of changing places. Human geographers and psychologists, in particular, are actively examining how people encounter, negotiate and make sense of both personal and environmental change (Simandan, Citation2020; Dickinson, Citation2018). A key facet of this work is the acknowledgement that digital technologies (in particular, the documentation of mundane, extreme, traumatic or even taboo events) enable forms of embodied sense-making during times of trauma or change (Hjorth & Cumiskey, Citation2018). Specifically, this study offers a new element to these research areas and offers opportunity to question how the live-streaming of moments of catastrophic change contributes to sense-making both for the streamer and their audience. The noted increase in streaming practices during EWEs – including those which resulted in the death of streamers (Dillane, Citation2023) – demands research into the complex and layered intersections of time, space, self and other.

Fourth, a significant and novel finding of this study was the examination of ‘committed viewing’ behaviours – whereby empathy and solidarity is both imagined and performed through lengthy periods of ‘weather watching’. The recognition of this behaviour both contributes to an expanding collection of work on digital expressions of solidarity (Ruiu & Ragnedda, 2022) but also requires a reconsideration of the motivations and drivers of engagement with hazard imagery. Further research could explore in more depth (i) the drivers and performances of those practicing committed-viewer behaviour, (ii) the extent to which networks form and persist through the consumption of live-streamed imagery, and (iii) whether similar commitments to banal spectacles can be observed in other streaming contexts.

In sum, this study has highlighted that the viewership of live-streamed EWEs is both significant and increasing. The nature of the streams themselves – starting in the run-up to events making landfall/reaching their peak – sees the emergence of lengthy and complex discussion spaces where connections to affected locations are imagined and performed, where risk guidance and knowledge about hazard dynamics is shared and contested, and where memories of historic events contribute to hazard sense-making. Existing in part as an exploratory study, this research highlights the urgent need for further work that examines the risk knowledge and behavioural implications of engagement with such spaces.

Ethics

The project was approved by the University of Plymouth Ethics Committee. As the project draws on publicly available online data, participants have not been required to sign informed consent forms.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank colleagues in the Centre for Research in Environment and Society at the University of Plymouth for input into the development of this research agenda.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 It is not possible to view the maximum simultaneous viewers a stream/channel held. Both of these numbers are live observations made by the author during research for this paper.

2 Given that the channels were not managed by the author, it was not possible to contact viewers. The author has an ongoing project which involves setting up streams, which enables viewers to be contacted and asked to complete a questionnaire. Future publications from this author will present these results.

3 It is not possible to know it these accounts equate to unique visitors. It is common on YouTube for users to have multiple accounts. A common ‘troll’ behaviour is to stimulate online debate by switching between accounts and posting as if they are another viewer.

4 Quotes in the discussion are kept in their original form where possible. Some have had to be edited due to spelling errors, use of emoticons and lack of punctuation. Where these have been added/edited, square brackets have been used.

5 The total number of viewers is difficult to accurately ascertain. Sometimes streams are automatically archived. In other instances, the stream is saved as a video and then uploaded separately (meaning the viewer count starts again at zero). As is common on YouTube, videos are often taken down by the host and then reuploaded at a later date – or even by other channels who have ‘ripped’ the video – all of which distorts viewer counts.

6 At the point of witnessing, events are not normally either considered to be, or declared, ‘disasters’. Most literature therefore uses the terminology of EWE, unless it is specifically focused on response and recovery periods.

7 This study is unable to analyse the locations of all commentors, and the intention of this section is not to examine the proximity. Rather, the section focuses specifically on three ways connections and attachments to affected places were expressed in comments on streams. As this section details, while some of these reveal locations and proximities, the focus is on how (dis)connections to the places depicted in the streams can be observed through comment content.

8 Commentors who expressed the intention to watch events continuously are termed ‘committed viewers’ from this point.

9 References to prayer and, in particular, prayer that lasted the entirety of the event was a repeated theme amongst committed viewers of these two events.

References

- Alexander, D. E. (2014). Social media in disaster risk reduction and crisis management. Science and Engineering Ethics, 20(3), 717–733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-013-9502-z

- Allan, S. (2013). Citizen witnessing: Revisioning journalism in times of crisis. Wiley.

- Andén-Papadopoulos, K. (2014). Citizen camera-witnessing: Embodied political dissent in the age of ‘mediated mass self-communication.’. New Media & Society, 16(5), 753–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813489863

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2013). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Bird, D., Ling, M., & Haynes, K. (2012). Flooding Facebook: The use of social media during the Queensland and Victorian floods. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 27(1), 27–33.

- Bucci, L., Alaka, L., Hagen, A., Delgado, S., & Beven, J. (2023). Hurricane Ian. National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report. https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL092022_Ian.pdf.

- Crawford, K. (2009). Following you: Disciplines of listening in social media. Continuum, 23(4), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310903003270

- David, C., Ong, J., & Legara, E. (2016). Tweeting Supertyphoon Haiyan: Evolving functions of Twitter during and after a disaster event. PLoS One, 11(3), e0150190. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150190

- Deng, Z., Benckendorff, P., & Wang, J. (2019). Blended tourism experiencescape: A conceptualisation of live-streaming tourism. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2019: Proceedings of the International Conference in Nicosia, Cyprus, January 30–February 1, 2019.

- Dickinson, S. (2018). Spaces of post-disaster experimentation: Agile entrepreneurship and geological agency in emerging disaster countercartographies. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 1(4), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848618812023

- Dillane, T. (2023, June 17). Father of Auckland flood victim Daniel Mark Miller watched moments before son’s death on livestream. New Zealand Herald. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/father-of-auckland-flood-victim-daniel-mark-miller-watched-moments-before-sons-death-on-livestream-it-hasnt-got-any-easier/WV6XP6SHQREIBFSRXEVGCARM34/

- Dowling, R., Lloyd, K., & Suchet-Pearson, S. (2018). Qualitative methods III. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 779–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517730941

- Edensor, T. (2008). Mundane hauntings: commuting through the phantasmagoric working-class spaces of Manchester, England. Cultural Geographies, 15(3), 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474008091330

- Fang, K. (2022). The social movement was live streamed: A relational analysis of mobile live streaming during the 2019 Hong Kong protests. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 28(1), https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac033

- Fang, K., & Cheng, C. Y. (2022). Social media live streaming as affective news in the anti-ELAB movement in Hong Kong. Chinese Journal of Communication, 15(3), 401–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2022.2083202

- Farinosi, M., & Treré, E. (2014). Challenging mainstream media, documenting real life and sharing with the community: An analysis of the motivations for producing citizen journalism in a post-disaster city. Global Media and Communication, 10(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742766513513192

- Fichet, E.S., Robinson, J.J., Dailey, D., & Starbor, K. (2016). Eyes on the ground: Emerging practices in periscope use during crisis events. International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management. http://faculty.washington.edu/kstarbi/ISCRAM2016_Periscope_FINAL.pdf

- Frers, L. (2013). The matter of absence. Cultural Geographies, 20(4), 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474013477775

- Haimson, O., & Tang, J. (2017). What makes live events engaging on Facebook Live, Periscope, and Snapchat. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025642

- Hjorth, L., & Cumiskey, K. M. (2018). Mobiles facing death: Affective witnessing and the intimate companionship of devices. Cultural Studies Review, 24(2), 166–180.

- Houston, J. B., Hawthorne, J., Perreault, M. F., Park, E. H., Goldstein Hode, M., Halliwell, M. R., Turner McGowen, S. E., Davis, R., Vaid, S., McElderry, J. A., & Griffith, S. A. (2015). Social media and disasters: a functional framework for social media use in disaster planning, response, and research. Disasters, 39(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12092

- Hu, M., Zhang, M., & Wang, Y. (2017). Why do audiences choose to keep watching on live video streaming platforms? An explanation of dual identification framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 594–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.006

- Kalmoe, N. P., Fuller, P. B., Santia, M., & Saha, P. (2022). Representation and aggression in digital racial conflict: Analyzing public comments during live-streamed news of racial justice protests. Perspectives on Politics, 20(4), 1226–1245. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722000123

- Karami, A., Shah, V., Vaezi, R., & Bansal, A. (2020). Twitter speaks: A case of national disaster situational awareness. Journal of Information Science, 46(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551519828620

- Kyriakidou, M. (2015). Media witnessing: Exploring the audience of distant suffering. Media, Culture & Society, 37(2), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443714557981

- Lisle, D. (2004). Gazing at ground zero: Tourism, voyeurism and spectacle. Journal for Cultural Research, 8(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1479758042000797015

- Lovari, A., & Bowen, S. A. (2020). Social media in disaster communication: A case study of strategies, barriers, and ethical implications. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(1), https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1967

- Luo, M., Hsu, T. W., Park, J. S., & Hancock, J. T. (2020). Emotional amplification during live-streaming: evidence from comments during and after news events. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 4(CSCW1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1145/3392853

- Magnusson, L., Tsonevsky, I., & Prates, F. (2017). Predictions of tropical cyclones Harvey and Irma. ECMWF Newsletter. https://www.ecmwf.int/en/newsletter/153/news/predictions-tropical-cyclones-harvey-and-irma.

- Mahanta, U., & Bharadwaj, G. (2022). Shifting boundaries of ‘perceived’ legitimacy. Performance Research, 27(3–4), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2022.2155420

- Mani, L., Cole, P. D., & Stewart, I. (2016). Using video games for volcanic hazard education and communication: an assessment of the method and preliminary results. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 16(7), 1673–1689.

- Martini, M. (2018a). On the user’s side: YouTube and distant witnessing in the age of technology-enhanced mediability. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 24(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517736980

- Martini, M. (2018b). Online distant witnessing and live-streaming activism: Emerging differences in the activation of networked publics. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4035–4055. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818766703

- McKinnon, S. (2019). Remembering and forgetting 1974: The 2011 Brisbane floods and memories of an earlier disaster. Geographical Research, 57(2), 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12335

- Mcphillips, L. E., Chang, H., Chester, M. V., Depietri, Y., Friedman, E., Grimm, N. B., Kominoski, J. S., Mcphearson, T., Méndez-Lázaro, P., Rosi, E. J., Shiva, Shafiei. (2018). Defining extreme events: A cross-disciplinary review. Earth's Future, 6, 441–455.

- Met Office. (2022). Storms Dudley, Eunice and Franklin, February 2022. https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/binaries/content/assets/metofficegovuk/pdf/weather/learn-about/uk-pastevents/ interesting/2022/2022_01_storms_dudley_eunice_franklin_r1.pdf

- Mortensen, M. (2015). Connective witnessing: Reconfiguring the relationship between the individual and the collective. Information, Communication & Society, 18(11), 1393–1406. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1061574

- Muhammed, S., & Mathew, S. K. (2022). The disaster of misinformation: A review of research in social media. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, 13(4), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-022-00311-6

- Palutikof, J., Agnew, M., & Hoar, M. (2004). Public perceptions of unusually warm weather in the UK: Impacts, responses and adaptations. Climate Research, 26, 43–59. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr026043

- Renn, O. (2020). Risk communication: Insights and requirements for designing successful communication programs on health and environmental hazards. In Handbook of risk and crisis communication (pp. 80–98). Routledge.

- Rosenbaum, M. S., & Culshaw, M. G. (2003). Communicating the risks arising from geohazards. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society, 166(2), 261–270.

- Saka, E. (2017). The role of social media-based citizen journalism practices in the formation of contemporary protest movements. In Barrie Axford, Didem Buhari-Gulmez, & Seckin Baris Gulmez (Eds.), Rethinking ideology in the age of global discontent (pp. 48–66). Routledge.

- Simandan, D. (2020). Being surprised and surprising ourselves: a geography of personal and social change. Progress in Human Geography, 44(1), 99–118.

- Sjöblom, M., & Hamari, J. (2017). Why do people watch others play video games? An empirical study on the motivations of Twitch users. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 985–996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.019

- Slick, J. (2019). Experiencing fire: a phenomenological study of YouTube videos of the 2016 Fort McMurray fire. Natural Hazards, 98(1), 181–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-019-03604-5

- Takahashi, B., Tandoc, E. C., & Carmichael, C. (2015). Communicating on Twitter during a disaster: An analysis of tweets during Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 392–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.020

- Thelwall, M., Sud, P., & Vis, F. (2012). Commenting on YouTube videos: From guatemalan rock to El Big Bang. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(3), 616–629. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21679

- Thorburn, E. D. (2014). Social media, subjectivity, and surveillance: moving on from occupy, the rise of live streaming video. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 11(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420.2013.827356

- Vieweg, S., Hughes, A., Starbird, K., & Palen, L. (2010). Microblogging during two natural hazards events: What twitter may contribute to situational awareness. Proceedings of CHI 2010, 1079–1088.

- Walshe, R. A., Adamson, G. C. D., & Kelman, I. (2020). Helices of disaster memory: How forgetting and remembering influence tropical cyclone response in Mauritius. International Journal of Risk Reduction, 50, 101901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101901

- Wang, B., & Zhuang, J. (2018). Rumor response, debunking response, and decision makings of misinformed Twitter users during disasters. Natural Hazards, 93(3), 1145–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3344-6

- Young, C. E., Kuligowski, E. D., & Pradhan, A. (2020). A review of social media use during disaster response and recovery phases. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.2086

- Zahra, K., Ostermann, F. O., & Purves, R. S. (2017). Geographic variability of Twitter usage characteristics during disaster events. Geo-Spatial Information Science, 20(3), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/10095020.2017.1371903

- Zhang, G. (2019). Zhibo: An ethnography of ordinary, boring, and vulgar livestreams. RMIT University.

- Zhang, H. (2022). Behind the scenes: exploring context and audience engagement behaviors in YouTube vlogs. In International conference on human-computer interaction (pp. 227–244). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Zhang, N., & Li, J. (2022). Effect and mechanisms of state boredom on consumers’ livestreaming addiction. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 826121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.826121