Abstract

Purpose

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is recommended to be included in communication interventions directed at children/youth with severe/profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (S/PIMD). Even so, the evidence base for AAC practices with children with S/PIMD is limited. Also, little is known about how frequently AAC is implemented with this target group, which AAC tools and methods are applied, and the related clinical reasoning of speech-language pathologists (SLPs). This study aimed to explore SLPs’ beliefs, clinical reasoning and practices in relation to AAC implementation with children/youth with S/PIMD.

Materials and methods

In this sequential, mixed-methods study, 90 SLPs working with children with disabilities within habilitation services in Sweden participated in an online survey. The survey answers were statistically analysed. Subsequently, focus group data were collected from seven SLPs and analysed using thematic analysis.

Results and conclusions

Despite AAC being highly prioritized, SLPs found it challenging and complex to implement with this target group. A wide variety of AAC methods and tools were considered and implemented. Clinical decision-making was a balancing act between competing considerations and was mainly guided by the SLPs’ individual, clinical experiences. The resources, engagement and wishes of the social network surrounding the child were considered crucial for clinical decision-making on AAC. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) seemingly find a wide variety of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC), ranging from unaided methods to assistive technology of various complexity, to be potentially suitable for children/youth with severe/profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (S/PIMD).

The motivation and preferences of the social network surrounding the child with S/PIMD seem to influence SLPs’ clinical decision-making on AAC to a high degree. Sometimes this may be considered an even more important factor than the abilities of the child.

SLPs’ clinical decision-making on AAC for children/youth is guided by their individual, clinical experience to a high degree.

An increase in family oriented AAC intervention research targeting individuals with S/PIMD could potentially strengthen the association between research and the current, experience-based clinical practice.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Communication is a basic, human need regardless of the presence of complex disabilities. The right to communicate and to do so through any mode of communication is protected in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [Citation1]. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) is implemented within clinical or educational practices, with individuals whose spoken and/or written communication does not meet their needs. The goal of AAC intervention is to enable efficient and effective engagement in interactions, participation in desired activities and to enhance learning and development [Citation2]. An AAC system can include some type of equipment or assistive technology (i.e., aided AAC) or build on bodily resources such as vocalizations, gestures or signs (i.e., unaided AAC). Multimodal AAC approaches are common and encouraged [Citation2]. The familiar communication partners of the individual with disability need to be involved in the AAC intervention process and receive instructions on how to integrate AAC into their communication [Citation3–5].

Children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (PIMD) have significantly limited cognitive abilities combined with severe motor disabilities [Citation6]. Their everyday functioning is commonly also affected by other disabilities (e.g., visual impairment) and medical conditions (such as epilepsy) [Citation6–9]. In this study, the term severe or profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (S/PIMD) is used, to manage the clinical indistinctiveness between severe and profound intellectual disabilities in this population, in line with a number of previous studies [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11].

Communication in children with S/PIMD is pre-symbolic and often pre-intentional [Citation12], meaning that the children rely on concrete ways of communicating and that the communication partner is essential in initiating and maintaining interaction. AAC has been suggested as having the potential to increase social participation for children with the most severe disabilities [Citation13]. AAC, both aided and unaided, is also argued to be useful in improving intentionality in young children with (varied) disabilities on pre-symbolic levels of communication [Citation14,Citation15], and in increasing intentionality and enhancing use of symbols when on the developmental levels of emerging language [Citation4,Citation16]. In a study by Holyfield [Citation17] preliminary evidence was provided that school-aged children with S/PIMD are able to increase their social gaze behaviour in interaction through a prelinguistic, object-based AAC intervention. Studies exploring the effects of AAC on communicative behaviours as well as development in children with specified S/PIMD are however sparce [Citation17,Citation18], and there are also general knowledge gaps when it comes to how AAC design can be developmentally sensitive to subgroups of children with atypical development in communication, cognition, motor skills, hearing and/or vision [Citation19]. In a systematic review of aided AAC interventions for individuals with S/PIMD, 25 studies with 59 participants were included [Citation18]. It was found that almost all included studies described interventions targeting requests supported by simple speech-generating devices (SGDs)/microswitches. Only one of the studies included parents in the intervention and a total of seven participants in included studies were under the age of six [Citation18]. Moreover, Simacek and colleagues [Citation18] concluded that much is unknown with regard to intervention intensity or maintenance and generalization of skills in relation to aided AAC interventions with the S/PIMD population.

Knowledge on AAC use in clinical practice with children with S/PIMD and its related clinical reasoning is limited. In general, professionals’ decision-making in AAC practice seems to be connected to a number of competing considerations regarding patient characteristics, features of the AAC system in itself [Citation20,Citation21] and sometimes also factors connected to daily communication partners [Citation22]. When it comes to working specifically with the S/PIMD population, studies targeting SLPs in Australia and the United Kingdom (UK) have reported on inclusion of AAC in communication interventions with individuals with S/PIMD [Citation23,Citation24]. In the UK, the most-used AAC practice with this population is reportedly objects of reference [Citation23]. A study exploring the use of assistive technology with individuals with profound ID in several European countries found that when assistive technology was applied, it was commonly used with the goal of supporting communication and interaction [Citation25], hence being used as AAC. In the context of Sweden, clinical use of AAC is mentioned in studies targeting children with severe motor disabilities combined with varied levels of intellectual disability [Citation26,Citation27] and Rett syndrome (a diagnosis that for some individuals results in S/PIMD) [Citation28]. AAC is included in the curriculum of a Swedish, clinically spread, parent-focused communication course, that is sometimes offered to parents of children with S/PIMD [Citation29].

Relationships between professionals’ attitudes or beliefs and their actual implementation of AAC or assistive technology with individuals with S/PIMD have been proposed [Citation25,Citation30] and in a more general patient context, AAC experience reportedly shapes decision-making in the AAC assessment process [Citation21]. The theory of planned behaviour [Citation31] has been utilized as a theoretical model to characterize similar relationships between professionals’ intentions to implement specified clinical or educational practices and (I) their beliefs and attitudes about the consequences of the practice, (II) the social support for engaging in the practice and (III) potential obstacles or enabling factors for implementing the practice [e.g., Citation32,Citation33].

In Sweden, AAC is provided to children with S/PIMD through the child and youth habilitation services. The Swedish Health and Medical Services Act (1982:763) regulates the free-of-charge availability of habilitation services and (if needed) communication aids for individuals with intellectual disabilities. The habilitation services aim to provide multi-professional support and interventions to promote development, functional abilities and well-being, in active cooperation with the parents, and preferably in coordination with other healthcare services and school/pre-school [Citation34,Citation35]. SLPs within habilitation services are encouraged to prioritize interventions targeting communication partner responsiveness and multimodal AAC with young patients on pre-symbolic levels of communication [Citation36].

Given the relatively low level of research evidence for various AAC interventions targeting children with S/PIMD (beyond some use of SGDs in school contexts), it is to a large extent unknown what beliefs SLPs hold regarding AAC and S/PIMD, how their clinical decision-making is shaped, to what extent AAC is implemented and which AAC tools and methods are typically implemented. Evidence-based AAC practices most often follow the clinician-driven practice-to-research route [Citation37]. More knowledge on clinical AAC practices and clinical reasoning targeting individuals with S/PIMD could hence guide future intervention research in this field, which is warranted in order to strengthen the evidence base.

The study aimed to answer the following research questions: 1) To what extent do SLPs intend to implement AAC with children/youth with S/PIMD? 2) Which AAC tools and methods are typically included in AAC interventions with children/youth with S/PIMD? 3) What beliefs do the SLPs hold relating to AAC interventions with children/youth with S/PIMD and how do these beliefs guide their clinical reasoning and decision-making? 4) Is there a relationship between on the one hand SLPs’ clinical experience and on the other hand their beliefs and clinical decision-making regarding AAC with children/youth with S/PIMD?

Materials and methods

Study design

The study was a mixed methods study with a sequential, explanatory design [Citation38,Citation39]. As such, the study was executed in subsequent phases where the first phase informed the second phase [Citation38–40]. First, an online survey was performed, and the data were statistically analysed. Second, to fully answer the research questions and to explain and interpret statistical findings, two complementary focus groups were carried out.

Phase 1: online survey

Participants

Eligible participants in this study were SLPs working with children or youth with S/PIMD (up to 18 years of age) within the habilitation services in Sweden.

Heads of habilitation services in 11 Swedish, counties were contacted with an enquiry about recruiting participants within their organizations. Habilitation services in nine counties (covering approximately 73% of Sweden’s population) agreed to cooperate. A contact in each cooperating county forwarded an email with study information and survey invitations to all SLPs working within the child and youth habilitation services (N = 219). The survey was open for respondents for five weeks. The response rate was 56% (123 submitted survey responses). Some responses were excluded (a total of 33) due to the respondents not working with patients with S/PIMD (N = 28), or the respondents not consenting to their answers being used in the research project (N = 5). Thus, the survey answers of 90 respondents constitute the data in Phase 1 of the study. Demographic information of the respondents is shown in . No information about non-responders was available to us.

Table 1. Included survey respondents’ characteristics.

Procedure

The survey content was mainly informed by an unpublished Master’s thesis by two SLP students, targeting SLPs’ experiences from AAC interventions with children and youth with S/PIMD [Citation41]. The findings indicated that the SLPs utilized a predominantly multimodal AAC approach and that the AAC intervention processes were highly individualized and dependent on the resources of the social network surrounding each child, the AAC knowledge and interest of the colleagues (of varied professions) as well as the respective SLP’s clinical experience of patients with S/PIMD [Citation41]. Based on these results, we decided to include a wide and detailed range of AAC characteristics in the survey. The AAC-specific items in the survey were structured and labelled in a way that sought to be comprehensible to the clinically-based SLPs in a habilitation services context in Sweden. Communication passports were included in the survey despite them not necessarily being formally classified as an AAC intervention [Citation23]. Still, communication passports are instructional resources for communication partners that aim to enhance interaction between individuals with disability and communication partners [Citation42] and are reportedly used with the S/PIMD population [Citation23,Citation41].

The SLPs’ experiences of complexity related to AAC interventions with this target group [Citation41] prompted us to address demographic factors in connection to clinical experience. We were guided by the theory of planned behaviour [Citation31] when designing survey items, to attempt to capture the social cognitive factors that may influence the SLPs’ clinical decision-making.

The survey was divided into six sections and contained a total of 30 items (with occasional sub-items). A description of each section follows in . The survey in its entirety, translated into English, can be found in a supplementary file.

Table 2. Summary of survey content, section by section.

Swedish University Computer Network (SUNET); a cloud-based tool for online surveys, was utilized for running the survey. The survey was accessible to the respondents through a web link that was received by email. Respondents were not able to respond to the survey twice from the same IP-address.

Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize and describe the demographic data as well as the responses to items in the section addressing experiences/intentions/beliefs and the section addressing implemented AAC. Associations between items addressing AAC methods and tools on the one hand, and work experience on the other, were investigated using Spearman’s rho correlations. (The data were generally not normally distributed, and a non-parametric te). Due to the number of correlations performed, the Bonferroni corrections for multiple correlations can be considered. However, the Bonferroni correction is considered to be overly conservative in cases such as the current one [Citation43], where the items concerning AAC are unlikely to be independent from one another in relation to experience factors. Instead, we aimed to transparently account for all performed correlations, their strengths and to interpret patterns of associations at both 0.05 (less conservative) and 0.01 (more conservative) alpha levels, with two-tailed tests.

Phase 2: focus groups

After completion of the statistical analysis in Phase 1, the results were robustly discussed by the authors in relation to the research questions. In this connecting analysis [Citation40], we decided where qualitative data would potentially add clarification and deeper understanding. Focus groups were chosen because they enable the researcher to seek patterns when a range of individuals share and contrast opinions and ideas about a common topic [Citation44]. The connecting analysis guided the execution of the focus groups in the study’s second phase.

Participants

Focus group participants were recruited from survey respondents. Through purposive sampling we aimed to include SLPs a) with a variety of work experience from habilitation services b) with a varied percentage of S/PIMD cases in their caseload c) from different counties d) who stated (in the survey) that they prioritized other communication interventions over AAC as well as SLPs who stated that they did not.

In the survey, 53 respondents declared an interest in participating in a focus group. We initially sorted them into a matrix, based on their work experience (in years) from habilitation services and the percentage of worktime devoted to S/PIMD patients. Notes were made regarding which county they worked for, and their survey reply regarding how they prioritized AAC interventions. Based on this information and our principles for purposive sampling, 11 respondents with long habilitation service experience and 13 respondents with shorter habilitation service experience were selected and contacted. Out of those 24 SLPs,19 replied to the invitation, but some declined participation (N = 7) or were unable to attend at designated dates (N = 5). Finally, seven SLPs working in five different counties consented to participate in one of our focus groups.

In order to avoid power differentials and hierarchies and to create a comfortable environment for everybody to share their views [Citation44], we designated one of the focus groups (Group A) for SLPs with long working experience within habilitation services and the other focus group (Group B) to SLPs with fewer working years within habilitation services. See for description of the participants.

Table 3. Demographic features of participants in the focus groups (as annotated in the survey).

Procedure

Focus groups were carried out online as virtual meetings lasting 90 min each. On-site focus groups were deemed unrealistic given how the participants were scattered geographically.

Data coding and analysis

The focus group data were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by the first author. A reflexive, thematic analysis was conducted on the transcribed data [Citation45,Citation46]. The first author performed the major part of the analysis but consulted with the other authors. Both transcripts were firstly read with the overarching research questions in mind and secondly coded semantically [Citation45], starting with the transcript of Group A. After having coded both transcripts, the codes together with their corresponding extracts were grouped into initial themes. This process was influenced by fieldnotes and preliminary perceptions of the patterns of the focus group discussions, as perceived by the first author. In a gradual, reflexive process where focus shifted between the research questions, the transcripts, coded extracts and potential themes, the codes and themes were refined, regrouped, and a final thematic structure was decided upon, with one overarching theme and three sub-themes. All themes were prevalent in both focus groups.

Ethical considerations

All included survey respondents received written information about the study, and actively consented (within the survey) to participate in the study. Only respondents who were interested in participating in the focus groups disclosed their identity (by declaring contact information of their choice). The focus group participants received both written and oral information about the study and consented in writing to participation. The study was submitted to the Swedish Ethical Review Authority for assessment (application number 2020-05228). The authority had no ethical objections to the study protocol.

Results

Results from phase 1 (survey)

SLPs’ intention to implement AAC

The respondents were asked “When you meet a patient with S/PIMD (…) and you are asked to clinically address their communication, how often do you offer any kind of AAC?”. They rated their answers on a scale from −3 (“never”) to 3 (“always”). Median was at the end of the scale: 3.0 (mean: 2.5, SD 0.69, min/max: 0/3), revealing a very high self-reported intention to implement AAC with the target group.

SLPs’ beliefs related to AAC interventions with children/youth with S/PIMD

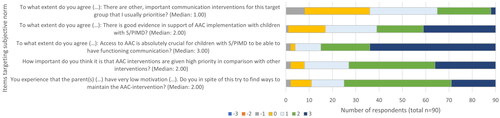

In , ratings of subjective norm (beliefs about the importance and value of AAC implementation with children/youth with S/PIMD) are visualized. As can be seen, the SLPs generally rated highly on items addressing the importance or value of AAC. However, there were also relatively high agreements on the item addressing whether the SLPs rated other communication interventions higher than AAC (Md:1).

Figure 1. Stacked bar chart showing how answers to items addressing subjective norm in relation to AAC implementation were distributed. The scale ranged from -3 (equivalent to never/unimportant/do not agree at all) to 3 (equivalent to always/very important/completely agree).

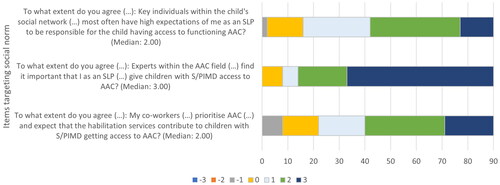

The respondents were asked about the perceived expectations from others to implement AAC with children/youth with S/PIMD. shows the responses to these items. “The social network of the child” was characterized as “family, teachers, personal assistants, etc”. “Experts within the AAC field” were characterized as “employees at regional AAC centres or colleagues with long experience of working with AAC”. The term “co-workers” referred to colleagues in the multi-professional habilitation team. The SLPs generally rated highly on these items, indicating that they perceived other stakeholders to value AAC interventions, and to expect the SLPs to implement AAC with children/youth with S/PIMD. AAC experts received particularly high ratings.

Figure 2. Stacked bar chart showing how answers to items addressing social norm in relation to AAC implementation were distributed. The scale ranged from -3 (equivalent to do not agree at all) to 3 (equivalent to completely agree).

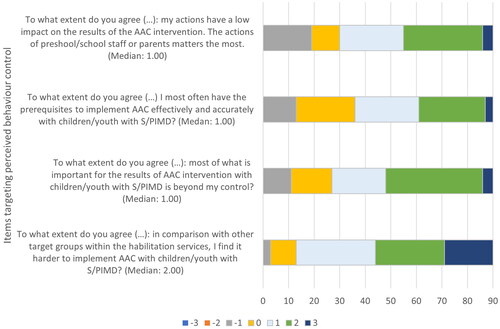

Four items addressed the respondents’ perceptions of how easy or difficult it is for them to successfully implement AAC with children/youth with S/PIMD. Results showed substantial variation among respondents, yet the results revealed a low sense of control and experienced difficulties in relation to AAC implementation with patients with S/PIMD, from most respondents. The results are shown in .

Figure 3. Stacked bar chart showing the distribution of item ratings concerning perceived control over the implementation of AAC intervention with children/youth with S/PIMD. The scale ranged from –3 (equivalent to do not agree at all) to 3 (equivalent to completely agree).

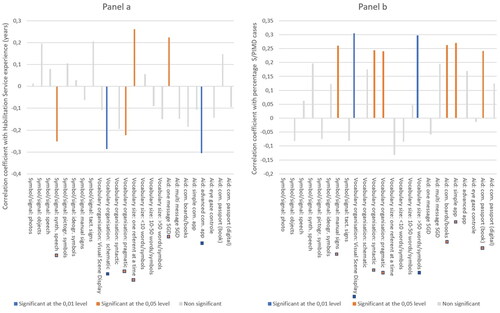

Figure 4. Correlations (Spearman’s Rho) between frequency of implementing specified AAC with children/youth with S/PIMD and: Panel a) experience from working within habilitation service (number of years), as well as Panel b) experience from working with children/youth with S/PIMD (percentage of total caseload).

Types of AAC that are included in interventions

Twenty-four items addressed how often various AAC characteristics had been implemented with children/youth with S/PIMD in the last two years. Detailed descriptive results from all 24 addressed AAC characteristics are presented in . The vast majority of the median ratings were distributed on the lower half of the scale. The highest median values (equivalent to 1) were obtained for items targeting the use of simple speech-generating devices (with one message) and objects and manual signs as symbols/signals.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics addressing Likert ratings that referred to how often the specified AAC had been included in interventions with children/youth with S/PIMD in the last 2 years.

Clinical experience in relation to decision-making and beliefs regarding AAC

The Spearman’s Rho test was used to calculate correlations between either experience from working within habilitation services (number of years) or experience from working with children/youth with S/PIMD (percentage of patient-focused work-hours that was dedicated to the S/PIMD group) and each of the specified AAC characteristics. Results are shown in , showing different patterns of correlation. This means that experience from habilitation services and experience from patients with S/PIMD correlated with different clinical decision-making about what AAC tools or methods to implement.

Figure 5. Thematic structure.

Correlations were also calculated between, on the one hand, experience from habilitation services or experience from patients with S/PIMD, and, on the other hand, beliefs about AAC (items addressing subjective norm, social norm or behaviour control). Only two significant correlations were found. S/PIMD experience correlated positively with perceptions about a strong evidence base (statement: “There is good evidence supporting AAC implementation with children/youth with S/PIMD”) (Rho: 0.21, p<.05). Habilitation Service experience correlated positively with perceived importance of AAC in relation to other interventions (question: “How important do you think it is that AAC interventions are given high priority in comparison with other interventions?”) (Rho: 0.23, p<.05). No correlations at the 0,01 level were found in those correlation analyses.

Results from phase 2 (focus groups)

The focus group discussions followed a topic guide and were centred around the following topics: 1) values and beliefs related to the wide variety of implemented AAC; 2) experienced challenges specific to AAC implementation with the S/PIMD target group; 3) conceptual boundaries of AAC in relation to implementation with the S/PIMD group and 4) perceived social norm in relation to AAC implementation with the S/PIMD group.

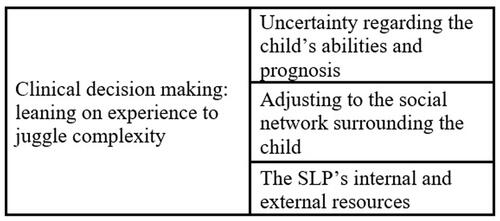

The thematic analysis of the focus group data resulted in one overarching theme “clinical decision-making: leaning on experience to juggle complexity” and sub-themes (see ). The themes are elaborated with illustrating quotes below.

Clinical decision-making: leaning on experience to juggle complexity

The participants unanimously expressed that clinical decision-making on AAC relating to children/youth with S/PIMD is very complex and relies on multiple factors. “I find that there are a lot of different factors that impact my assessment” (Bella). This seemed to refer to decisions on the choice of specific AAC as well as where, how and in cooperation with whom it should be implemented. However, the complexity rarely seemed to prompt the decision not to view AAC as feasible. ““It seems ethically problematic not to offer any kind of AAC intervention” (Britt).

There was no clear, paved path to follow, but rather unique decisions, relying on a number of factors that were mainly connected to the child, their social environment and characteristics and circumstances surrounding the SLP (elaborated further in the sub-themes). All AAC methods seemed to be viewed as possibly appropriate for individuals with S/PIMD, depending on the circumstances. Sometimes, some SLPs seemed to experience a feeling of not living up to the standards they wished to practice by: “There is the way that you imagine you should be working, and then there is the clinical reality” (Betty). The more experienced SLPs expressed that through experience, they had learned to juggle the complexity by being flexible when thinking of potential AAC solutions, setting realistic goals based on the whole situation and expecting slow progress. This contrasted to their practice in earlier years of their careers:” I think back to when I was new myself, and it was easy to get started thinking ‘(…) this family hasn’t any AAC at all, what should I do?’ and then you sort of began with too much, too intensely, too quickly.” (Angelica) The younger SLPs mentioned that it was important to get clinical advice from more experienced colleagues or experts and thus lean on the experience of others. In line with this, experienced SLPs mentioned how they guided young, ambitious and sometimes overwhelmed colleagues not to rush into too complex intervention plans with this group of patients: “Sometimes I act as a sounding board (…) My role is probably to dial down expectations (…) I usually say more like: ‘start with the basics, where are the basics?’” (Anne).

Uncertainty regarding the child’s abilities and prognosis

Factors relating to the specific child seemingly guided the clinical decision-making. On a general note, children with S/PIMD were perceived to have more individual challenges than other patients. The importance of finding an AAC system which could enhance the specific individual’s quality of life was mentioned.

Children/youth with S/PIMD were experienced to develop at a very slow and unpredictable pace and this was repeatedly mentioned as a challenge when planning an intervention and knowing what outcome to expect. Even the most experienced SLPs found themselves having to try different intervention paths without knowing beforehand if they would necessarily suit the specific child and their developmental trajectories. “You search quite a lot, and try many different approaches, which means that you find it to be more difficult” (Alice). The most common way to manage this seemed to be to set intervention goals that were quite low and to develop a mindset where you appreciate every bit of (small) progress.

Further, the individual child’s unique combination of abilities and disabilities affected clinical decision-making about AAC. The motor disabilities of the children/youth with S/PIMD seemed to partly prompt a focus on aided AAC. This was due to an overall focus on aids in the habilitation process with this group of patients. Also, other aids, such as wheelchairs, created opportunities for mounting communication aids, such as screens. Presence of sensory impairments was mentioned as a critical aspect of the clinical decision-making regarding AAC: “There you sort of have to consider vision, hearing, interpretation, CVI [Cerebral Visual Impairment] (…)” (Betty). Perceived uncertainty about the actual, cognitive abilities of the specific child with S/PIMD was mentioned as a challenge in relation to clinical decision-making. ““I also find it (…) very tricky with cognition when you do not know a child’s level” (Anita).

Adjusting to the social network surrounding the child

The social context of children with S/PIMD was raised by all participants as perhaps the most important factor for clinical decision-making. Children/youth with S/PIMD were sometimes experienced as having more complex and multi-branched social networks than others. At the same time, the success of any AAC intervention was experienced to be very dependent on the persons surrounding the child in his/her everyday life.” They [children with S/PIMD] are so hugely reliant on their [social] environment that it depends: if a parent gets sick or if good assistants are replaced by less committed assistants or if you change teachers to someone who does not see the point of AAC, then it sort of does not matter how much you work with the child, because it is still the environment that carries the communication” (Britt). The parents were most commonly mentioned as being important in relation to clinical decision-making on AAC, but other parts of the child’s social network were also mentioned and discussed.

The families of children/youth with S/PIMD were experienced to more often than other families lack capacity in terms of time and energy. “These parents are more often completely worn down, the ones who have children with S/PIMD” (Alice). The SLPs reported that they tended to lower the bar of the intervention when they perceived that the parents had too much on their plate. Sometimes, if the parents lacked capacity to participate in the intervention, then the intervention could rely more heavily on someone else, such as a personal assistant or a member of school staff. However, this solution was vulnerable to staff turnover. If the social network lacked someone with a strong driving force, the SLPs found it very difficult to implement AAC and especially so for high-tech AAC. “You can try to introduce something more technically advanced, but the chances of it succeeding are pretty slim if there is not a strong driving force close by. And that is sort of the most important factor” (Britt).

The SLPs described in various ways how the expectations and motivations of parents and others in the child’s network affected the clinical decision-making. The expectations could relate to particular interventions or to the child’s development. The importance of a motivated social network was stressed repeatedly. ““We do want the family to be motivated. It is the family’s motivation that matters, very much so” (Bella). Technology seemed motivating to some stakeholders. It could prompt a sense of normality and competence (since “all children” use tablets, for instance). Also, parents may have seen or heard of other children use a particular aid and hope that the same one would be beneficial to their child. Sometimes the expectations and motivations differed between the SLP and the child’s social network. The SLPs experienced that some parents (or other stakeholders) had unrealistic expectations on high-tech AAC as a “quick fix”, while others had very low motivation to engage in AAC where the SLP saw that the child had potential to benefit from it. Some social networks needed a lot of coaching and encouragement in order to remain motivated.” To maintain the motivation to use AAC with a patient who may not respond for an extremely long time, if at all. (…) It is very easy to give up at that point, I think. There are several conversations like that too, about keeping on and sticking with it” (Angelica). Yet other stakeholders had long-term goals for the intervention that were far more ambitious than the SLP viewed as realistic. The SLPs with long experience shared that over the years they had become more inclined to listen to the stakeholders, and particularly the parents, when they had strong opinions about certain AAC solutions or long-term goals. “Experience also brings some humility (…). When I was new, I could more clearly say: ‘this is what’s best for you’. And now I have seen too many times that totally different choices were the best ones” (Anne). Sometimes, to give the parents’ wishes a fair chance, the SLPs initially went along with them, but had a “Plan B” to suggest, should it be needed.

The complexity of the disabilities in children with S/PIMD combined with slow development was also experienced to cause more conflicting expectations and motivations between parents within the same family or between the school and the home, compared with other groups of patients, in turn complicating the clinical decision-making of the SLPs. “I talk a lot with the family, and I try to talk to the school too but (…) they do not always agree” (Betty).

The particular circumstances of implementing AAC in cooperation with the school were mentioned in both focus groups. In school, it was found that AAC needed to be functional not only in one-on-one interaction. “[In school] they want to use things that are usable for the whole group. They want to use the interactive whiteboard in joint activities and communication boards, pictures and manual signs” (Britt). When it comes to high-tech AAC devices, it was recognized that it could be very impractical for teachers and other school staff to learn to use a different high-tech device for each student in the class. The SLPs sometimes suggested a method or tool that was already in use by peers in the class, even if one could argue in favour of another solution when only looking at the needs of the specific child. “Because if you come to a teacher and introduce, well the fifth variant of something, then there is a less chance of that working. If you choose something that another child uses, well then…” (Anne).

It was also mentioned that it usually became easier to implement AAC when the child started school since the teachers could be expected to have some AAC knowledge.

The SLP’s internal and external resources

As described in the overarching theme the AAC practice with children with S/PIMD seems to be experience driven. Hence, the individual experiences of each SLP were described as shaping their clinical decision-making. The AAC solutions of former patients seemed to be go-to choices when faced with a new patient. “There is a threshold to get going with, for example, Snap Core First or PODD book or something and it, it matters quite a lot to my clinical decisions which other children I have [on my caseload]. If I have a couple who use Snap Core First, then I have wrapped my head around that system (…), while I at the same time may not have had any users of PODD books, causing me to have a high threshold to initiate that” (Britt). Some AAC-methods cannot be implemented unless the clinician takes a mandatory course. Whether or not the SLP had taken various courses widened or limited the AAC toolbox. On the other hand, even when accredited on a certain AAC method, the experience of practicing it still seemed like the most important factor for whether or not it would be further used. “Maybe not just what courses I have taken, but also what I feel confident in and what I have seen functioning well (…). I may have a course accreditation but never use it. And then perhaps when an opportunity actually arises, I still won’t use it” (Betty).

The SLPs seemed to experience that they had to interpret and define AAC’s conceptual boundaries for themselves. When asked about whether it was clear which interventions with children/youth with S/PIMD were to be classified as AAC, the answer was unanimously “no” and the participants imagined that perceptions of conceptual boundaries of AAC probably differed between SLPs. Several mentioned that the concept seemed to have been gradually broadened in recent years to include strategies for supporting interaction or cognition. The more complex the disabilities, the more unclear it seemed whether certain interventions were in fact AAC. “…like interpreting reactions, I think of that as AAC. I can write it down: ‘when the child does this, then we interpret it like that’ and then we reinforce what the child does, and it becomes an expression (…) But does that count as AAC or not?” (Anne). It was unclear whether the confusion regarding the AAC boundaries affected the clinical decision-making, but it did seem to complicate the practice since education and communication about AAC with persons in the child’s social network was such an important part of the practice. “It depends on who you ask. Does the school view that as AAC or not? Do the parents view it as AAC?” (Angelica)

A variety of factors connected to the SLPs’ organizational contexts were mentioned in relation to clinical decision-making. Available resources such as sufficient time, opportunities to take courses, clear routines for implementation of interventions, proximity to experienced colleagues (both SLPs and other professions) and available expert teams within the organization all affected the SLPs’ practices. Organizational support was particularly helpful when you as an SLP lacked experience, such as when being newly employed, when implementing an AAC method for the first time or when facing a patient with a rare condition. Also, regulations on prescribing publicly funded aids differed slightly across the counties, thus affecting clinical decision-making.

Discussion

In this explanatory, mixed-methods study, we explored Swedish SLPs’ clinical decision-making regarding AAC with children and youth with S/PIMD. The results painted the picture that AAC was highly valued, offered to a very large extent, and that a wide variety of AAC methods and tools was considered. The (perceived) “ideal” AAC solution was balanced against the complexity of the child’s disabilities and uncertain prognosis, the resources and wishes of the child’s social network and the resources of the SLP in terms of time, knowledge, clinical experience and access to knowledgeable colleagues. More detailed conclusions to each research question will be presented and discussed below.

Intention to implement AAC

It was concluded that the SLPs had very high intentions to implement AAC with children/youth with S/PIMD. They seemed to (almost) always offer AAC. It was even reflected upon as an ethical obligation. We are not aware of any prior studies concluding a high intention to implement AAC with children/youth with S/PIMD. In this context it is worth mentioning that the conceptual boundaries between AAC and cognitive support and between AAC and intervention strategies supporting interaction were unclear to the SLPs. When interpreting the high intentions to implement AAC it may hence be most accurate to cautiously apply a wide definition of AAC.

Commonly implemented AAC

A variety of AAC tools and methods were implemented with children/youth with S/PIMD, according to the survey results. More concrete AAC solutions had the highest ratings, but out of 24 addressed AAC characteristics, only two (vocabulary organized as visual scene displays and use of ideographic symbols) received medians that were equivalent to “never”, when asked how often the AAC method had been implemented in the last two years. The low ratings on visual scene displays could be considered surprising, given that it is recommended to use this with emerging communicators and that it has been found to be less cognitively demanding than other ways to organize vocabulary [Citation19]. The thematic analysis confirmed that the SLPs seemed to consider the complete AAC toolbox as potentially valid, but that the clinical decision-making on methods and tools was a balancing act between several factors, that were all taken into account. Similar trade-offs between competing factors have been reported in AAC decision-making in previous studies [Citation20,Citation47,Citation48].

Beliefs about AAC intervention with children with S/PIMD

The third research question addressed beliefs and values relating to AAC interventions and how these beliefs and values guided the clinical decision-making in connection to AAC. The cognitive abilities of the children were discussed in the focus groups as being important when deciding on an AAC method, but no specific suggestions or ideas were further elaborated. For emerging communicators, AAC systems should harmonize with the child’s current developmental level and at the same time challenge the child and promote growth in developmental domains [Citation19]. However, the child’s exact level of cognitive functioning was sometimes experienced as being under discussion and the children were often experienced as having very uncertain trajectories of cognitive development. This seemingly challenged the SLPs when trying to find the best AAC fit.

Given the children’s low cognitive functioning, it may be surprising that seemingly more cognitively demanding AAC solutions with large vocabularies were considered and implemented. Less cognitively demanding AAC solutions (such as using one referent at a time) were indeed the most common (according to survey results). Nevertheless, the SLPs did not think that low cognitive functioning in the child necessarily excluded the more advanced AAC methods. Relatedly, in a previous study on assistive technology use with individuals with profound ID, it was found that professionals with more knowledge on assistive technology considered the person’s limited cognition to be less of an obstacle to the implementation of assistive technology, as compared to professionals with less assistive technology knowledge and experience [Citation25]. However, for the SLPs to consider more cognitively demanding or more technically advanced AAC, the SLPs carefully considered the motivation and engagement of the child’s daily communication partners. Indeed, one of the most evident themes in the thematic analysis was the adjustment to the resources and motivations of the child’s social network when choosing and implementing AAC. Also, the analysis of survey data showed that the majority rated positively on the item stating that the actions of parents and teachers had greater impact on the outcome of the AAC intervention than the actions of the SLP. Some focus group participants even articulated that the social network’s motivation and resources were the factors that most strongly guided their clinical decision-making. Similar results have been found in a study on SLPs’ clinical reasoning in relation to AAC interventions targeting children with autism, where “the communication partner’s AAC skills” and “the communication partner’s perception of AAC outcomes” were two of the most frequently mentioned factors considered to predict, moderate and mediate AAC outcomes [Citation22]. The highlighted importance of the parents and other significant communication partners was motivated by the belief that the quality of communication of children with S/PIMD is very reliant on the interactional patterns of the communication partner, a belief that is confirmed by literature [Citation49–51]. The importance of the communication partner’s involvement in interventions targeting children/youth with S/PIMD is indeed previously recognized [Citation16,Citation52,Citation53] as well as the importance of individualizing AAC interventions aimed at children with disabilities and adjusting them to the parents’ knowledge, abilities and desires [Citation54,Citation55]. A family centred approach for AAC services has been proposed, where the application of family systems theory and ecological systems theory guides successful, collaborative relationships with the families in AAC intervention [Citation56].

Research evidence was almost never mentioned in the focus groups as a factor that strongly guided the clinical decision-making about AAC with children/youth with S/PIMD. This resembles the results in a British study addressing SLPs’ approaches to communication interventions with individuals with PIMD [Citation23] and similar results have been found regarding SLPs’ clinical decision-making on AAC for children with other, or a broader range of disabilities [Citation22,Citation57]. In the survey results, it was however evident that a majority of the SLPs believed that there is good research evidence in support of AAC interventions with children/youth with S/PIMD. This stands somewhat in contrast to the current research evidence on AAC targeting this group, which is actually rather limited [Citation17,Citation18,Citation23].

Clinical experience in relation to decision-making and beliefs about AAC

Both statistical and thematical analyses indicated relationships between clinical experience and clinical decision-making but not necessarily between clinical experiences and beliefs about AAC. According to an Australian study, SLPs view their individual, clinical experience from working with AAC and children with S/PIMD as important for gaining adequate skills to implement communication intervention with this target group [Citation24]. Our results seem to add the notion that different clinical experience may guide different decision-making. Statistically, experience from the habilitation service correlated significantly with implementation of certain AAC methods, while the proportion of S/PIMD patients in the caseload correlated with implementation of some other AAC methods. These different relationships could possibly be explained somewhat by the results of the thematic analysis: Experiences from past patients and their social networks seemed to guide clinical decision-making to a great extent. The threshold for implementing more unusual and/or technically complex AAC solutions, such as eye gaze control or PODD books, could reportedly be quite high. However, once you as an SLP had already implemented them, you were more likely to implement them again. To have a higher proportion of complex patients on your caseload could possibly have prompted you to cross the threshold from “standard solutions” to more rare solutions, thus making you more inclined to do so again. This kind of experience-driven clinical choice-making could potentially explain why use of some of the less applied AAC methods (such as visual scene displays) correlated with the proportion of S/PIMD cases in the caseload. On the other hand, the SLPs who had worked for several years and had experience of following S/PIMD cases over a long time, described in the focus groups how they over the years had learned to “start with the basics” and not to rush too quickly into overly ambitious plans. This could possibly explain the positive correlation between habilitation service experience and (for instance) using one referent (e.g., one picture or object) at a time.

Moreover, the thematic analysis implied that long experience had nuanced some of the SLPs beliefs about their own competence in relation to the parents’ competence and made them more inclined to listen to the parents’ convictions about what interventions would work in the long run. The clinician’s sensitivity to parents’ wishes and acknowledgement of the parents as an expert on their own child has been proposed as being important for parents’ engagement in AAC intervention [Citation54]. Also, for the SLP to make compromises when a parent’s wishes do not match the SLP’s suggested choice of AAC has been argued to reduce the risk of AAC abandonment [Citation55]. This was mentioned as a conscious strategy by a couple of the more experienced SLPs in the focus groups.

Limitations

There are several potential limitations with the study. First, we have no information about the non-responders to the survey. This prevents us from knowing whether the non-responders and responders differed in important ways. Second, there is a risk of the survey responses being affected by social-desirability bias, where the SLPs overreported what they experienced as desirable AAC practice. Third, the counties included in the study were not strategically sampled, even though a coverage of more than 70% of Sweden’s population with diverse demography could potentially indicate representativity. Even so, the results cannot be directly generalized beyond the context of SLPs in Swedish habilitation services.

Implications for research and clinic

The study shed light on the important and challenging task SLPs face when working with AAC implementation and children with S/PIMD. Restricted resources when it comes to time and further training opportunities were mentioned in the focus groups as limiting factors in the everyday work, which seemed more informed by experience than by broader evidence. In the focus groups it was mentioned that a vision of how one ought to work (seemingly based for instance on research and case reports from clinical conferences) stood in contrast to a complex reality where it rarely felt possible to live up to the perceived standard. The few, available studies and their results may possibly be hard for the SLPs to translate to their actual, clinical context. There is a shortage of family and home oriented AAC intervention research targeting the S/PIMD population [Citation18] which is the primary intervention context for SLPs within Swedish habilitation services. More studies in this area of research are warranted and could potentially strengthen the association between clinical practice and research evidence. Some AAC characteristics that were quite commonly implemented are, to the best of our knowledge, very understudied when targeting the S/PIMD group, such as use of manual signs, tactile signs or AAC solutions with larger vocabulary sizes, prompting intervention studies in these areas.

It seems clinically relevant to raise self-awareness about the evidence-based relevance of the family-centredness that the SLPs described in the focus groups. This is supported in literature as important for avoiding AAC abandonment [Citation55,Citation56]. The SLPs mainly referred to this as being learned through experience, and it seems it would be empowering for them to learn that their clinical instincts in this matter harmonize with research evidence. Maybe especially so when there sometimes seemed to be a sense of failure on the SLP’s part when compromising or adjusting their initial plan for AAC to the resources and wishes of parents.

Beyond the scope of this study, but interesting for future studies, is the topic of applied intervention goals for the AAC interventions, how these are clinically evaluated and what counts as “successful” AAC implementation with children/youth with S/PIMD. Goal setting was touched on in the focus groups as being challenging. When targeting the S/PIMD population with its slow and uncertain developmental trajectories, it is reportedly very difficult to assess and track communication development in research [Citation9,Citation58,Citation59] as well as in clinical practice [Citation60]. Hence, it is of interest to explore how goal setting and evaluation of AAC interventions are handled in clinical practice.

In line with other previous research exploring professional decision-making in healthcare and education [e.g., 32,33], we applied the theory of planned behaviour as a theoretical guide when developing the survey [Citation31]. We found it to be a useful framework when characterizing potential factors associated with clinical decision-making in AAC practice and we encourage it to be used in further related research.

Another area for future studies is the shared interprofessional decision-making between the healthcare setting and the school or pre-school setting. In the focus group data, the collaboration with teachers in schools was highlighted as important for clinical decision-making.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (333.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to all participating SLPs who devoted time to share their clinical insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- United Nations. 2006. [cited 2022 Feb 04]. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- Beukelman DR. Augmentative & alternative communication: supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (Light JC, editor.) 5th ed. Baltimore (MD): Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.; 2020.

- Light J, McNaughton D. Designing AAC research and intervention to improve outcomes for individuals with complex communication needs. Augment Altern Commun. 2015;31(2):85–96. Jun

- Romski M, Sevcik RA, Barton-Hulsey A, et al. Early intervention and AAC: what a difference 30 years makes. Augment Altern Commun. 2015;31(3):181–202.

- Kent-Walsh J, Murza KA, Malani MD, et al. Effects of communication partner instruction on the communication of individuals using AAC: a Meta-Analysis. Augment Altern Commun. 2015;31(4):271–284.

- Nakken H, Vlaskamp C. A need for a taxonomy for profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. J Policy Practice Intellect Disabil. 2007;4(2):83–87.

- Van Timmeren E, Waninge A, van Schrojenstein Lantman-de H, et al. Patterns of multimorbidity in people with severe or profound intellectual and motor disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2017;67:28–33.

- Flink AR, Boström P, Gillberg C, et al. Exploring co-occurrence of sensory, motor and neurodevelopmental problems and epilepsy in children with severe-profound intellectual disability. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;119:104114.

- Van Keer I, Dhondt A, Van der Putten A, et al. Lessons learned: a critical reflection on child-and contextual variables related to the development of children with a significant cognitive and motor developmental delay. Res Dev Disabil. 2022;120:104142.

- Griffiths C, Smith M. Attuning: a communication process between people with severe and profound intellectual disability and their interaction partners. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2016;29(2):124–138.

- Johnels L, Vehmas S, Wilder J. Musical interaction with children and young people with severe or profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: a scoping review. Int J Develop Disabil. 2021:1–18. [cited 2022 Oct 1].

- Dhondt A, Van Keer I, van der Putten A, et al. Communicative abilities in young children with a significant cognitive and motor developmental delay. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2020;33(3):529–541.

- Calculator SN. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) and inclusive education for students with the most severe disabilities. Int J Inclusive Educ. 2009;13(1):93–113.

- Branson D, Demchak M. The use of augmentative and alternative communication methods with infants and toddlers with disabilities: a research review. Augment Altern Commun. 2009;25(4):274–286. Dec

- Cress CJ, Marvin CA. Common questions about AAC services in early intervention. Augment Altern Commun. 2003;19(4):254–272.

- Ogletree BT, Pierce HK. AAC for individuals with severe intellectual disabilities: Ideas for nonsymbolic communicators. J Develop Phys Disabil. 2010;22(3):273–287.

- Holyfield C. Preliminary investigation of the effects of a prelinguistic AAC intervention on social gaze behaviors from school-age children with multiple disabilities. Augment Altern Commun. 2019;35(4):285–298.

- Simacek J, Pennington B, Reichle J, et al. Aided AAC for people with severe to profound and multiple disabilities: a systematic review of interventions and treatment intensity. Adv Neurodevelop Disord. 2017;2(1):100–115.

- O'Neill T, Wilkinson KM. Designing developmentally sensitive AAC technologies for young children with complex communication needs: Considerations of communication, working memory, attention, motor skills, and Sensory-Perception. Semin Speech Lang. 2019;40(4):320–332.

- Murray J, Lynch Y, Meredith S, et al. Professionals’ decision-making in recommending communication aids in the UK: competing considerations. Augment Altern Commun. 2019;35(3):167–179.

- Dietz A, Quach W, Lund SK, et al. AAC assessment and clinical-decision-making: the impact of experience. Augment Altern Commun. 2012;28(3):148–159.

- Sievers SB, Trembath D, Westerveld MF. Speech-Language pathologists’ knowledge and consideration of factors that may predict, moderate, and mediate AAC outcomes. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(1):238–249.

- Goldbart J, Chadwick D, Buell S. Speech and language therapists’ approaches to communication intervention with children and adults with profound and multiple learning disability. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2014;49(6):687–701. Nov

- De Bortoli T, Arthur-Kelly M, Mathisen B, et al. Speech-Language pathologists’ perceptions of implementing communication intervention with students with multiple and severe disabilities. Augment Altern Commun. 2014;30(1):55–70.

- Nijs S, Maes B. Assistive technology for persons with profound intellectual disability: a european survey on attitudes and beliefs. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2021;16(5):497–504.

- Tegler H, Pless M, Johansson B, et al. Speech and language pathologists’ perceptions and practises of communication partner training to support children’s communication with high-tech speech generating devices. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2019;14(6):581–589.

- Holmqvist E, Thunberg G, Peny Dahlstrand M. Gaze-controlled communication technology for children with severe multiple disabilities: Parents and professionals’ perception of gains, obstacles, and prerequisites. Assist Technol. 2018; 2018/08/0830(4):201–208.

- Wandin H, Lindberg P, Sonnander K. Communication intervention in rett syndrome: a survey of speech language pathologists in Swedish health services. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(15):1324–1333.

- Rensfeldt Flink A, Åsberg Johnels J, Broberg M, et al. Examining perceptions of a communication course for parents of children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Int J Develop Disabil. 2022;68(2):156–167.

- De Bortoli T, Arthur-Kelly M, Foreman P, et al. Complex contextual influences on the communicative interactions of students with multiple and severe disabilities. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2011;13(5):422–435.

- Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22(5):453–474.

- Klaic M, McDermott F, Haines T. Does the theory of planned behaviour explain allied health professionals’ Evidence-Based practice behaviours? A focus group study. J Allied Health. 2019;48(1):43E–451. E.

- Lee J, Cerreto FA, Lee J. Theory of planned behavior and teachers’ decisions regarding use of educational technology. J Educ Technol Soc. 2010;13(1):152–164.

- Ylvén R. Factors facilitating family functioning in families of children with disabilities: in the context of Swedish child and youth habilitation service. Sweden: Karolinska Insitute; 2013.

- Habilitering i Sverige. Om habilitering [cited 2021 Oct 20]. http://habiliteringisverige.se/habilitering/om-habiliteringen

- Eberhart B, Forsberg J, Fäldt A, et al. Tidiga kommunikations-och språkinsatser till förskolebarn. Göteborg: Föreningen Sveriges Habiliteringschefer; 2017.

- Mirenda P. Values, practice, science, and AAC. Res Pract Persons Severe Disab. 2017;42(1):33–41.

- Creswell JW. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE publications; 2014.

- Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick SL. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):3–20.

- Plano Clark VL. Meaningful integration within mixed methods studies: Identifying why, what, when, and how. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2019; 2019/04/057:106–111.

- Lybing C, Törngren L. Implementering av AKK för barn och ungdomar som har flerfunktionsnedsättning - en studie av habiliteringslogopeders erfarenhet [Master’s thesis]: University of Gothenburg; 2020.

- Goldbart J, Caton S. Communication and people with the most complex needs: what works and why this is essential. UK: Mencap; 2010.

- Perneger TV. What’s wrong with bonferroni adjustments. BMJ. 1998;316(7139):1236–1238.

- Krueger R, Casey M. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2009.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc. 2019;11(4):589–597.

- Webb EJ, Lynch Y, Meads D, et al. Finding the best fit: examining the decision-making of augmentative and alternative communication professionals in the UK using a discrete choice experiment. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e030274.

- Webb EJ, Meads D, Lynch Y, et al. What’s important in AAC decision-making for children? Evidence from a best–worst scaling survey. Augment Altern Commun. 2019;35(2):80–94.

- Hostyn I, Maes B. Interaction between persons with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities and their partners: a literature review. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;34(4):296–312.

- Van Keer I, Ceulemans E, Bodner N, et al. Parent-child interaction: a micro-level sequential approach in children with a significant cognitive and motor developmental delay. Res Dev Disabil. 2019;85:172–186.

- Van Keer I, Colla S, Van Leeuwen K, et al. Exploring parental behavior and child interactive engagement: a study on children with a significant cognitive and motor developmental delay. Res Dev Disabil. 2017; May64:131–142.

- Bruce SM, Bashinski SM. The trifocus framework and interprofessional collaborative practice in severe disabilities. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2017;26(2):162–180.

- Van keer I, Maes B. Contextual factors influencing the developmental characteristics of young children with severe to profound intellectual disability: a critical review. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2016;43(2):183–201.

- Marshall J, Goldbart J. Communication is everything I think.' parenting a child who needs augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2008;43(1):77–98.

- Moorcroft A, Scarinci N, Meyer C. We were just kind of handed it and then it was smoke bombed by everyone’: How do external stakeholders contribute to parent rejection and the abandonment of AAC systems? Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2020;55(1):59–69.

- Mandak K, O'Neill T, Light J, et al. Bridging the gap from values to actions: a family systems framework for family-centered AAC services. Augment Altern Commun. 2017;33(1):32–41.

- Dada S, Murphy Y, Tönsing K. Augmentative and alternative communication practices: a descriptive study of the perceptions of South African speech-language therapists. Augment Altern Commun. 2017;33(4):189–200.

- Dhondt A, Van Keer I, Nijs S, et al. In search of a novel way to analyze early communicative behavior. Augment Altern Commun. 2021;37(2):87–101.

- Flink AR, Broberg M, Strid K, et al. Following children with severe or profound intellectual and multiple disabilities and their mothers through a communication intervention: single-case mixed-methods findings. Int J Develop Disabilit. 2022:1–19. [cited 2022 Oct 1].

- Chadwick D, Buell S, Goldbart J. Approaches to communication assessment with children and adults with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32(2):336–358.