Abstract

Purpose

To understand and combat the challenges in taking up and implementing technology in rehabilitation settings, the HabITec Lab, a clinical service focused on technology, was piloted for 12-months within a tertiary hospital. This article reports on its preliminary impacts as a clinical service and on clients, including the types of assistive technology (AT) in demand.

Materials and Methods

Referral and administrative data from 25 individuals who attended the HabITec Lab were collated and analysed using descriptive statistics. For those who attended more than once (n = 12), goal attainment was assessed using the Modified Goal Attainment Measure (MGAM). Post-intervention semi-structured interviews were completed with participants to understand their experience at the HabITec Lab. Interviews were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

Most attendees (92%) were undergoing inpatient rehabilitation following a spinal cord injury (SCI). The majority (73%) of goals related to improving entertainment and connection. All participants who completed the MGAM showed improved goal attainment following their HabITec Lab attendance. Qualitative data highlighted appreciation for the service and suggestions for its future.

Conclusions

This study revealed a high level of demand for support to use AT amongst individuals with SCI, particularly consumer-grade smart devices that could assist communication. This finding may have been influenced by the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and frequent lockdowns during this period. This study indicated that the HabITec Lab was able to address important goals for attendees, but also illuminate a new future and trigger enthusiasm about future goals. Attendance was liberating, but resourcing barriers were frustrating.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Dedicated socio-technological spaces such as HabITec are an important way to provide access to expertise and develop consumer knowledge of technology not adequately addressed elsewhere in the rehabilitation continuum.

Access to technological support for individuals in the inpatient setting facilitates access to technology in the present and capacity building to foster ongoing use of technology in the future.

Dedicated socio-technological spaces should be adequately resourced, funded, staffed and promoted to ensure optimal outcomes.

Access to Smart devices within the inpatient rehabilitation setting is critical for people with spinal cord injury to foster communication with family, friends and communities.

Introduction

Advancements in technologies and commercialisation of devices has increased the availability and relevance of assistive technology (AT) for people with disability [Citation1]. AT includes any product designed or used to “maintain or improve an individual’s functioning and independence and thereby promote their wellbeing” [Citation2]. AT can be used to enhance participation in daily activities, education, or employment, and has the potential to improve quality of life for people with disability [Citation3]. Although AT is more available and relevant to people with disability than ever before, it is estimated that about 1 in 3 AT devices are abandoned [Citation4], due to issues such as mismatch between the user’s need and the device, lack of suitability with the user’s environment, and inadequate follow-up to enable use [Citation5]. Further, even before AT is prescribed and acquired, barriers such as lack of awareness, high costs, limited access, and insufficient knowledgeable workforce hinder more widespread and effective use of AT [Citation6]. Indeed, successful uptake and implementation of AT relies on the alignment of appropriate knowledge, skills, policies, and procedures, often referred to as AT systems [Citation2].

AT systems in the context of health care settings are largely influenced by organisational stakeholders such as policy-makers, clinicians, and AT funders [Citation7, Citation8]. Responsibilities of these stakeholders include: regulating the access and use of AT within the clinical setting, identifying the clinical need for patients and clients, upskilling health professionals in the use and prescription of AT, and ensuring that funding can be accessed to procure and maintain AT [Citation7]. It has been demonstrated that when issues occur within AT systems, the implementation of AT is impacted. For instance, in a recent study conducted within a spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation centre, it was found that uptake of AT was marred by limited AT availability and by clinicians reporting an inability to use products without support from an expert with adequate technical knowledge and skills [Citation9]. Whilst this study gives an indication as to some of the issues that can occur within the AT system, it is widely acknowledged that further research into AT systems is required. A recent systematic review by Larsson Ranada and Lidstrom [Citation4] for instance, identified that much of the research into the AT service delivery processes was descriptive in nature and of moderate quality, with a large portion of it focusing on individual elements of the process rather than the process in its entirety. Furthermore, they identified that there is limited evidence of the impact of the process on end-user uptake, satisfaction and usefulness of prescribed AT.

Given these issues that can occur within AT systems and impact on AT uptake, Kendall et al. (2019) developed a socio-technical space known as HabITec which aimed to address some of the issues [Citation10]. HabITec was developed with three main aims: (1) to improve awareness and uptake of technology in rehabilitation; (2) to promote innovation in disability and rehabilitation through technology; and (3) to develop bespoke solutions to improve rehabilitation, independent living, and participation in the community. HabITec was designed to facilitate collaboration amongst clinicians, funders, researchers, designers, and developers, with people with disability at the centre. This collaborative approach enables everyone to focus on a shared set of goals to co-design and co-create new solutions.

In this paper, we describe a pilot implementation of HabITec within a clinical space – the HabITec Lab – over a period of 12 months. We: 1) map and analyse the characteristics of technology that were demanded by those who attended the HabITec Lab; 2) describe the impact of the HabITec Lab attendance on their goals; 3) explore their experience with the attendance at the HabITec Lab, their satisfaction and the impact of the attendance on access to technology.

Methods

This research project used an explanatory sequential mixed methods approach to address the research aims. This approach involves the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data in a sequential manner, with the qualitative data being collected and analysed after the quantitative data to clarify or provide a new interpretation of the quantitative results [Citation14]. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Metro South Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/2019/QMS/59476) and Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee (GU Ref No: 2020/061). Approval to access patient information from electronic medical records was obtained through the Public Health Act (Qld) (2005).

The HabITec Lab

During December 2019 to November 2020, a lab (the HabITec Lab) was established within a tertiary hospital that provides acute care, rehabilitation, and outpatient services across specialties such as brain and spinal cord injury. The lab was staffed by a senior occupational therapist with extensive experience and interest in rehabilitation technologies. The dedicated therapist provided assessment and intervention to people with disabilities who had goals specifically related to technology. This dedicated therapist was supported by resources for people with disabilities to have opportunities to trial and test devices, connect with technical experts, and the time to invest in navigating this process. This role was unique to the HabITec Lab and differed from therapists working in other clinical areas at the hospital, who were also carrying out responsibilities of providing day to day rehabilitation, equipment provision, and discharge planning. Lab staffing was supplemented by occupational therapy students.

The lab itself was located within a room in the spinal injuries unit. However, the environment in which the assessments and interventions were conducted were not limited to the lab and included the hospital ward as required, e.g., for patients with mobility issues. The lab was available 1 day per week and had a variety of AT products available for demonstration and trial as well as access to external agencies, suppliers, and technical experts that were readily accessible as required. Marketed through department meetings and word of mouth, it could be accessed at any time by rehabilitation staff for support and information, but formal access for patients occurred either by self-referral or via a health professional (see ). Referrals required an outline of the person’s technology-specific goal(s). Once the referral was received, the HabITec Lab clinician conducted a comprehensive assessment, provided recommendations, and prescribed interventions to achieve the individual’s goals using technology. Referring health professionals and any other informal supports were encouraged to attend the HabITec Lab with the individual.

Figure 1. Service pathway for the HabITec Lab. PWD = person with disability; ESM = scheduling and reporting system; MDT = multidisciplinary team. [image re-used with permission from the Hopkins Centre].

Overview of the HabITec Lab service pathway for a patient in the hospital to their home. A person wanting to explore technology is referred and can receive a quick response, or complex prescribing which involves specialist assessment, intervention, and outreach to the home.

The HabITec Lab service pathway for a patient in the hospital to their home consists of 2 main stages. First, a person wanting to explore technology is referred to The HabITec and is triaged to receive a quick response, or complex prescribing. A quick response appointment consists of education and/or link to other services. Complex prescribing involves specialist assessment (including goal setting, planning and outcome measures), intervention (assess existing technology use and need for bespoke solution, determine learning and training needs, provision and adjustment of technology-based solutions), and outreach to the home (including education and training around existing technologies, co-creation of bespoke solutions, linking to other services, and education).

![Figure 1. Service pathway for the HabITec Lab. PWD = person with disability; ESM = scheduling and reporting system; MDT = multidisciplinary team. [image re-used with permission from the Hopkins Centre].Overview of the HabITec Lab service pathway for a patient in the hospital to their home. A person wanting to explore technology is referred and can receive a quick response, or complex prescribing which involves specialist assessment, intervention, and outreach to the home.The HabITec Lab service pathway for a patient in the hospital to their home consists of 2 main stages. First, a person wanting to explore technology is referred to The HabITec and is triaged to receive a quick response, or complex prescribing. A quick response appointment consists of education and/or link to other services. Complex prescribing involves specialist assessment (including goal setting, planning and outcome measures), intervention (assess existing technology use and need for bespoke solution, determine learning and training needs, provision and adjustment of technology-based solutions), and outreach to the home (including education and training around existing technologies, co-creation of bespoke solutions, linking to other services, and education).](/cms/asset/01ec69cb-ecf6-452a-8f20-7dc96798f73e/iidt_a_2244001_f0001_c.jpg)

The types of interventions people with disability could receive in the HabITec Lab included:

Consultation: a single session involving assessment, intervention and recommendations, the provision of general AT information and education to increase awareness, and referral to external or partnering agencies if needed;

Repetitive practice: multiple regular sessions to provide an opportunity to learn how to use a device, troubleshoot, and build knowledge, skills, and confidence in its use, often in preparation for discharge; and

Bespoke solutions: multiple sessions involving identification and engagement of the most appropriate discipline or organisation to co-design unique solutions to specifically meet individual needs or goals.

Participants

Individuals who were accessing either inpatient or outpatient services within the tertiary hospital where the HabITec Lab was located during this pilot period (December 2019 to November 2020) were eligible. No further eligibility criteria were established.

Recruitment

After their first attendance at the HabITec lab, participants were approached by the clinician to seek consent to be contacted by an independent research assistant (a medical student, who was not involved in the design or delivery of the HabITec Lab) for a semi-structured interview. Following consent to participate, the independent research assistant contacted participants to organise face-to-face or telephone interviews, depending on individuals’ preferences and location. Interviews were conducted within 2 weeks of informed written consent being obtained.

Data collection

Referral and administrative data of all the individuals who participated in the HabITec Lab were extracted from electronic medical records and collated in a spreadsheet. Data included demographic information, AT-related goals, and goal attainment scores.

The Multidisciplinary Goal Attainment Measure (MGAM): The MGAM offers a way of measuring goal attainment in goal-directed services [Citation15]. The MGAM is a tool that has been adapted from the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Citation15]. The COPM assists individuals to identify and prioritise occupational performance issues and evaluate their own performance and satisfaction with occupational performance. The COPM can therefore be used to assist with goal setting but also to identify changes in self-perceived occupational performance and satisfaction over time. The MGAM was developed to be a multidisciplinary version of the COPM, which has traditionally been used by occupational therapists. In the MGAM, participants nominate their goal(s) and numerically rate their perception of their own performance and satisfaction related to each goal. Performance and satisfaction are measured separately, each on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates poor self-perceived performance and satisfaction, and 10 indicates high self-perceived performance and satisfaction. The MGAM has been shown to be a viable and valid measure across relevant client groups [Citation15, Citation16]. In this study, MGAM data was collected from all individuals as part of initial goal-setting during their first attendance of the HabITec Lab. Follow-up MGAM scores were collected only for individuals who participated in multiple sessions due to its focus on the measurement of change over time. Thus, pre-attendance MGAM data provided an understanding of the goals of participants and post-attendance MGAM data for a smaller sub-group explored the change over time in attainment of these goals.

Interviews were conducted by the independent research assistant. Participants who were inpatients at the tertiary hospital were interviewed in an environment on the ward that offered privacy and minimal distraction. Participants who had been discharged from hospital and were living in the community at the time of follow-up were interviewed over the telephone. The interview used open-ended questions and an interview protocol guided the interview process. Probing questions were designed to explore new or unexpected emerging ideas. Interviews ranged from 20 to 41 min with a mean length of 27 min. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Quantitative data

Referral and administrative data were analysed using a descriptive-evaluative approach [Citation17]. To limit participant identifiability, we have not provided detailed information on participants’ goals or linked demographic information. Participants would be easily identified given the highly specialized nature of the clinical services, the known timeframe, and the relatively small number of participants in this population. Instead, we grouped similar goals into high-level categories, such as entertainment and connection, ambitions and aspirations, and living safely and easily. These categories were identified and named following an iterative discussion by the research team that continued until consensus was reached.

Non-parametric analyses were used to analyse MGAM scores due to the small sample size. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to compare pre- and post-intervention goal performance and satisfaction scores. Pre- and post-intervention scores were then used to calculate change scores for goal performance and satisfaction [Citation15]. Change scores were compared across gender, inpatient/outpatient status, location, employment status and living situation. Bivariate correlations were used to determine whether age was related to goal performance or satisfaction change scores.

Qualitative data

A descriptive qualitative approach was used to analyse data derived from qualitative interviews [Citation18]. This is a pragmatic approach to qualitative data analysis, enabling the researcher to identify how people make sense of the world [Citation18, Citation19], in this case, how participants of the HabITec Lab experienced their interactions with the lab.

Thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clark [Citation20] was used to examine semi-structured interview data due to its ability to analyse peoples’ experiences, views, and perspectives. Two members of the research team who had not been involved in the design and delivery of the HabITec Lab (MK and TH) completed data analysis. Transcriptions were read independently and repeatedly by both researchers, to ensure familiarity of the data (Phase 1). Both researchers then completed independent line-by-line coding of the entire data set (Phase 2). Once both researchers had independently coded data they came together to compare codes, discussing any differences, and agreed on potential overarching themes (Phase 3). These themes were then checked against the raw data to ensure they were reflective of participants’ experiences (Phase 4). Following this, all members of the research team (CS, EK, MK, SO, and TH) reviewed the themes to discuss, develop and finalise themes until consensus was reached, with themes being given a final name and description at the end of this phase (Phase 5). Findings were then written up with typical examples selected to describe the themes (Phase 6).

Results

Demographic information

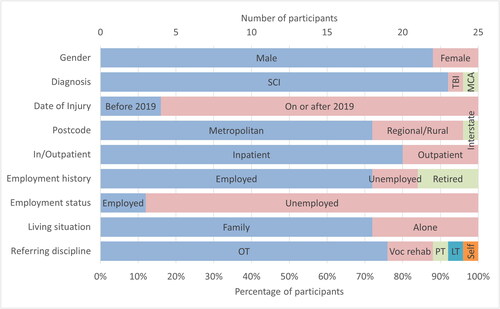

The HabITec Lab was accessed by 25 individuals during the study period (). This represented maximum capacity for the HabITec Lab resourced at one day a week (this was fully booked by 30–60 min appointments only). The majority of participants had a diagnosis of spinal cord injury (SCI) (n = 23, 92%), and the remaining two participants had a traumatic brain injury (TBI) and a middle cerebral artery stroke (MCA) respectively. The majority were male (n = 22, 88%) which is consistent with the eligible population. Given the physical location of the HabITec Lab within the Spinal Injuries Unit, most participants were inpatients (n = 20, 80%) undergoing rehabilitation following a SCI. Five participants (20%) were referred from the outpatient/community rehabilitation setting. At the time of their injury, most participants were employed (n = 18, 72%), but only three individuals (12%) remained employed at the time of attending the HabITec Lab. Referring clinicians were mostly occupational therapists (n = 19, 76%), but also included vocational rehabilitation counsellors (n = 2, 8%), a physiotherapist (4%), and a leisure therapist (4%). Only one individual self-referred (4%).

Figure 2. Referral and administrative data for all 25 participants. SCI: spinal cord injury, TBI: traumatic brain injury, MCA: middle cerebral artery stroke, OT: occupational therapist, PT: physiotherapist, LT: leisure therapist.

Bar graphs indicating 9 participant demographic and referral characteristics: gender, diagnosis, date of injury, postcode, in/outpatient status, employment history, employment status, living situation and referring discipline.

Bar graphs indicating 9 demographic and referral characteristics of the 25 participants. Gender: 22 participants were male, 3 were female. Diagnosis: 23 participants had an SCI, 1 had a TBI, 1 had a stroke. Date of injury: 4 were before 2019, 21 were on or after 2019. Postcode: 18 participants were from metropolitan areas, 6 from regional or rural areas, and 1 interstate. In/outpatient status: 20 were inpatients, 5 were outpatients. Employment history: 18 participants were employed at the time of injury, 3 were unemployed, and 4 were retired. Employment status: 3 participants were unemployed at the time of attending The HabITec Lab, 22 were unemployed. Living situation: 18 participants lived with family and 7 lived alone. Referring discipline: 19 participants were referred by occupational therapy, 3 by vocational rehabilitation, 1 by physiotherapy, 1 by leisure therapist and 1 was self-referred.

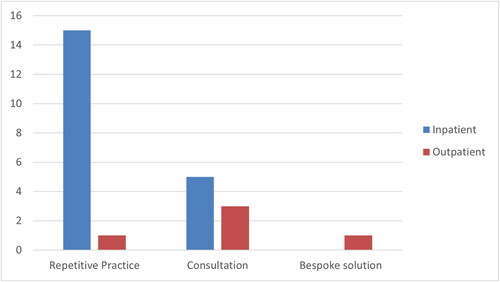

Types of intervention

The majority of interventions were repetitive practice (as described under The HabITec Lab in the methods section; ), which were mostly received by individuals who were inpatients. Outpatients mostly received consultations or bespoke solutions to suit their community setting. No inpatients required bespoke solutions.

Figure 3. Number of individuals that received each type of intervention by in/outpatient setting.

Bar plots of the total number of intervention sessions per intervention type and participant’s inpatient/outpatient status. Inpatient repetitive practice was by far the most common session.

Types of goals

A total of 40 goals were identified across the 25 individuals. The number of goals ranged from one to four per individual with a median of one goal (interquartile range IQR = 1) per individual. There were no differences in the number of goals identified across gender, inpatient/outpatient status, location, employment status, or living situation, and there was no correlation between age and the number of goals set.

In relation to the types of goals identified by individuals (), the vast majority related to a focus on accessing smart devices (tablets and phones) for entertainment and connection (n = 29, 73%). All the stated goals involved a drive to achieve important and meaningful functions as independently as possible. The goals were classified into three categories, namely entertainment and connection, ambitions and aspirations, and living safely and easily.

Table 1. Goals identified by the 25 individuals that attended the HabITec Lab: number by types of goals, with examples.

MGAM scores

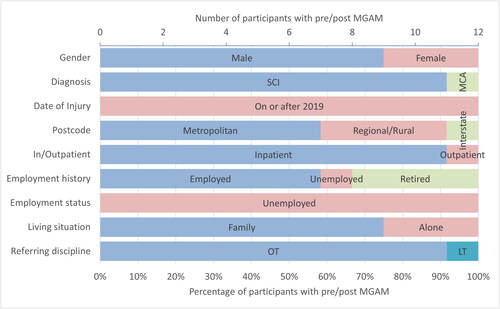

Of the 16 participants (15 inpatients and 1 outpatient) who received repetitive practice, 12 completed the MGAM post-intervention (). These participants were mostly male who had sustained a recent SCI and were referred by their OTs. Four participants did not complete the follow-up MGAM due to situational reasons (e.g., unexpected discharge or competing priorities in rehabilitation).

Figure 4. Referral and administrative data for participants that completed MGAMs pre- and post-intervention.

Bar graphs indicating 9 participant demographic and referral characteristics: gender, diagnosis, date of injury, postcode, in/outpatient status, employment history, employment status, living situation and referring discipline.

Bar graphs indicating 9 demographic and referral characteristics of the 12 participants. Gender: 75% of participants were male. Diagnosis: 11 participants had an SCI, 1 had a stroke. Date of injury: all incidents were on or after 2019. Postcode: 7 participants were from metropolitan areas, 4 from regional or rural areas, and 1 interstate. In/outpatient status: 11 were inpatients. Employment history: 7 participants were employed at the time of injury, 1 was unemployed, 4 were retired. Employment status: all participants were unemployed at the time of attending The HabITec Lab. Living situation: 9 participants lived with family and 3 lived alone. Referring discipline: 11 participants were referred by occupational therapists, 1 by leisure therapist.

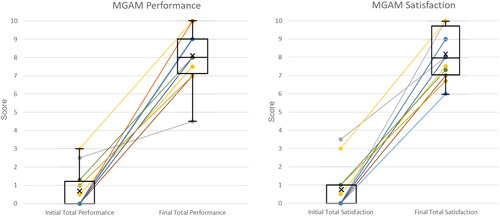

The increase from pre- to post-intervention MGAM scores () was statistically significant for both performance (Z = 3.07, p = 0.002) and satisfaction (Z = 3.07, p = 0.002). For the performance subscale, change scores ranged from 2 to 10 (median 7.50, IQR 2.22), and for the satisfaction subscale, change scores ranged from 4.5 to 10 (median 7.00, IQR 2.92). There were no differences in change scores across gender, inpatient/outpatient status, location, employment status or living situation, although age did demonstrate moderate positive correlations with change in goal performance (r = 0.65, p = 0.022) and satisfaction (r = 0.65, p = 0.023).

Figure 5. MGAM scores pre (Left) and post (right) attending the HabITec Lab for: (a) performance and (b) satisfaction. Scores within individual are connected by lines.

Individual scores and across-participant descriptive statistics boxplots of MGAM Performance scores pre and post attending the HabITec Lab. All individuals scores increased.

Individual scores and across-participant descriptive statistics boxplots of MGAM Satisfaction scores pre and post attending the HabITec Lab. All individuals scores increased.

Semi-structured interviews

A total of twelve individuals participated in the interviews following their attendance at the HabITec Lab (; note this is not the same group of twelve participants with pre- and post-intervention MGAMs). All participants had SCI at the cervical level resulting in upper limb deficits and were undergoing inpatient rehabilitation at the time they attended the HabITec Lab.

Table 2. Demographic information of the 12 interview participants.

Two overarching themes were identified from participants’ data. These two themes reflected the importance of the HabITec Lab as a catalyst for a new way of operating, with illuminating results for participants. In the first theme, participants recommended that the service be more adequately promoted so rehabilitation patients could understand the potential benefit and develop appropriate expectations. The second theme emphasised the liberating benefit of exposing participants to a range of options and expertise that could trigger optimism about the future. Participants recommended adequately resourcing the service to ensure it could realise the benefits for those who attended.

Theme 1: Illuminating a new way forward

Participants described their overall enthusiasm and support for the HabITec Lab despite having no prior expectations, “my expectation was zero, and the outcome was 100” [ID11]. Most participants noted that their first contact with the HabITec Lab was initiated by their occupational therapists or other health professionals, but they were also enthusiastic about attending: “It was my decision but it was sort of in collaboration with OTs” [ID3]. Once they started attending the HabITec Lab, participants reported receiving an unexpected range of services and interventions, including technological expertise, advice, and support (including problem solving); physical demonstrations; exploration and trials of technological options; set up of devices and accessories; and repetitive practice in preparation for discharge from hospital. Participants described the eye-opening nature of the HabITec Lab, confirming that it had provided a strong basis of technological knowledge that they would use in their future. Participants reported being amazed by the technology they explored in the lab and what it could achieve for them. This effect was even more evident for those who lacked familiarity with technology prior to their injury.

Before I came [to HabITec], I didn’t even know that there was a Dragon [voice activated] program to access computers. I just thought I would not be able to access a computer again so it’s definitely opened my eyes to what is out there… [ID5]

Although participants were not aware of what the HabITec Lab could offer them prior to attending, they thought it was well worth their time and they would recommend it to others.

Just go there [HabITec], you may not know what is happening, just go there, listen learn and you may well come back, you may come away thinking nothing, you may walk away benefitting a lot. [ID6]

By enabling access to technology, the HabITec Lab appeared to trigger a number of positive secondary outcomes. Participants alluded to outcomes such as increased independence, a decreased sense of burden to others, increased confidence and self-efficacy in relation to technology, empowerment, improved coping and productivity, and overall improved well-being. “And it makes a difference in your wellbeing, which is quite important” [ID11].

The HabITec Lab appeared to provide participants with a foundation for their future, enabling them to be more informed in their considerations and preparations: “[HabITec]…gave me the foundations of what I can do now” [ID1]. Their interactions with HabITec appeared to instill a sense of curiosity in participants to explore more and the attitudes, skills, and capacity to seek technological solutions after discharge. The HabITec Lab also seemed to provide a feeling of ongoing support and a sense of security for participants as they continued their recovery. The presence of a service, a place and dedicated staff assisted participants with the development of longer-term attitudes, skills and capacity: “If you ever get stuck and you need something sorted out you can come to them [HabITec]” [ID4].

Suggestions for enhancing the HabITec Lab focused on awareness about the service. “It’s a good thing, but it just needs to be introduced and implemented better” [ID10]. Participants described how they did not know what to expect from the HabITec Lab prior to attending the lab, and this lack of expectation stemmed from a lack of information about the service. They suggested that other health professionals and areas of the hospital beyond the Spinal Injuries Unit were not as familiar with the HabITec Lab. Participants’ expectations were therefore limited or differed from what they received when they attended.

It was an odd thing to start with, because I didn’t know what it was going to be all about. [ID1]

Theme 2: Resourcing the options

The importance of the HabITec Lab as a place where new options could be safely explored and practiced with support was reinforced by participants.

One of the things that we had to do was make sure that you know you use it enough to be able to become familiar with it…the more you use it the better you got. [ID3]

Equally, exposure to a range of technological options was liberating for participants.

In the HabITec sessions I learned some mouse alternatives that I can use with one of those…you put your mouth on to the end of it and you sort of suck or blow to select or move it around…that was something I trialed and quite liked that’s an alternative to voice control. [ID5]

Consideration of available options often enabled them to retain meaningful ambitions for the future. For instance, ID5 discussed needing to be able to use a computer and related software to be able to keep options open for their future: “Wanting to use PowerPoint and Microsoft Word for if I decided to pursue studying options in the future”. ID3 also discussed a desire to use newly acquired technologies for important communication purposes “mainly sending emails, you know writing, dictation sort of thing, writing stories and stuff like that. I’d always had some sort of ambition to write stories…using the voice control.”

Participants emphasized the importance of adequately resourcing the HabITec Lab with a range of products and tools that could inspire the imagination of participants and health professionals.

[Be]cause before coming to HabITec I had nothing…I couldn’t use my phone [be]cause it’s a slide screen and so I couldn’t use it with my hands not moving and whatnot…then I was told that HabITec could help me so I come and see [HabITec therapist], and I bought a phone and they helped me set the phone up. [ID4]

However, these findings were often couched in comments about the need to adequately resource new options. Participants believed that the lack of physical resources particularly limited the scope of what HabITec could do. Participants, not surprisingly, suggested that the approach needed to rapidly become an embedded component of the rehabilitation unit, with adequate resources, space and staffing so it could deliver the promised benefits.

They only got one computer, so it is a bit of a challenge [laughs] I mean, if you really want to set it up properly, set it up as a classroom, and set up sort of 5 computers, and have […] a supervisor in there,…you can’t really call it a lab, [be]cause it’s just a room with one computer sitting in it. [ID8]

Although the majority of participants reported that their needs and goals were met by the HabITec Lab, some described barriers that were beyond their control, created by financial costs and technical frustrations that may have been resolved with greater assistance through the HabITec Lab. For instance, ID12 discussed technical issues they experienced with their apps and the interface with other technologies:

Yeah it works okay. Probably 90% of the time I can do what I need to. Sometimes some of the apps don’t work very well with voice control, so I can’t use them or can’t use them as effectively, but that’s just the way it is.

…I probably could’ve spent a lot more time in there. So when I, when I did uhm, was discharged from the uhm [hospital], I probably could’ve been much more equipped. [ID8]

Participants linked these access issues with a lack of staffing, resources, space and equipment. For instance, participants observed that limited staffing restricted HabITec, although they noted that staffing appeared to be an issue throughout the hospital.

A bit of a reoccurring theme or problem that I can see with every department is there’s not enough staff. So I think if there was more staff everywhere the whole experience of being in the hospital would have been better, including HabITec, and OT and physio, everywhere. Because sometimes I have an appointment and I’ll go there, and I’ll wait for half an hour and no one turns up because they’re looking after other people that have taken longer. And everyone’s got such a big caseload of people they’re looking after, sometimes you just get left behind, and it happened a lot. [ID12]

Having access to staff with sufficient technological expertise was also desired by participants. Some noted that this was not always the case in their experience, particularly where student occupational therapy assistants were supporting repetitive practice.

And the assistant that was helping me, she herself didn’t know Dragon very well, so it was the blind leading the blind a bit. So it wasn’t that useful to me. [ID10]

Discussion

Providing AT is challenging because it requires collaboration across stakeholders from diverse backgrounds. Although there is increasing recognition of the role for non-clinical stakeholders (such as policy-makers and end-users), clinical decision-makers, and developers [Citation7, Citation11–13], there are very few examples of efforts to bring all key stakeholders together. In this study, we sought to explore the implementation of a technology-focused clinical service, called the HabITec Lab, during a 12-month period in a tertiary hospital, with a particular focus on participants’ technology needs, achievement of technology-related goals, experience, and satisfaction.

Overall, the HabITec Lab was well-received by participants, who indicated that they had already, or would in future, recommend other patients to attend the HabITec Lab. They reported that a visit to the HabITec Lab was important “just to see what is possible and available” even in the absence of specific goals. Their suggestions for improvement of the HabITec Lab were focused on its promotion, access to the lab, availability of expertise, and resources. These suggestions are in line with literature, which highlights challenges around expertise [Citation21], awareness and promotion/organisational factors [Citation7, Citation22], financial factors [Citation7, Citation12], among others. The majority of people referred to the HabITec Lab had sustained a SCI and were referred by their OT. The majority of stated goals related to the use of smart devices for connection and entertainment and self-reported attainment of these goals improved following multiple attendances at the HabITec Lab. Qualitative findings suggested that the service was illuminating in that it highlighted new ways of living independent lives. Further, it was liberating in that it enabled a vision of the future to emerge that involved activities participants had previously thought would need to be abandoned. However, these benefits were limited by inadequate staffing, space, equipment and resources, which restricted opportunities for participants to engage with the HabITec Lab.

The current study found that the HabITec Lab was accessed primarily by people with SCI. The physical location of the HabITec Lab within the Spinal Injuries Unit may have contributed to this finding. Equally, previous research has shown that people with SCI have historically had more interaction with technology compared to those with more cognitive impairments due to their reliance on mobility devices (e.g., hoists, powerdrive wheelchairs, etc.) [Citation23]. However, this study revealed that mobility was only one reason for engaging with technology. Literature has shown useful functions of technology for people with cognitive impairments [Citation24, Citation25], but further research is needed to explore the way in which the HabITec Lab can respond to these needs.

Not surprisingly, a high proportion of participants had goals associated with communicating with their families and accessing entertainment. As the majority of participants were undergoing inpatient rehabilitation during the COVID-19 pandemic, time spent with family and friends was even more significantly reduced, increasing the need to access methods of connection. Hospital visitors were restricted, which may also have contributed to the increased desire to focus on communication methods than might be found in other periods of time. However, the pattern of demand for smart devices found in this study reinforces previous findings about the common desire and preference to access electronic devices for communication purposes [Citation26, Citation27]. Advancements in technology mean that smart devices now offer multiple purposes and functions within the one device, but participants were generally unaware of these functions. After their visit to the HabITec Lab, participants began thinking creatively about how their devices would enable them to work and engage in leisure activities [Citation28–30]. Participants indicated the desire to use their devices for entertainment (watching videos, social media), work, school, daily activities (banking), and home automation.

This study has confirmed that training and support for the use of smart devices should be incorporated into rehabilitation interventions and supported by funding bodies. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 91% of households use smart devices [Citation31], which indicates that the majority of the Australian population are already familiar with these technologies and that they are a part of their daily lives. Mainstream smart devices now offer a range of accessibility options such as voice assistants, voice control, and visual enhancement as standard built-in features. Existing knowledge and use of AT prior to injury increases the likelihood of ongoing use of AT and improves an individual’s perception of efficacy and autonomy [Citation26, Citation28, Citation30]. The ability to use the accessibility features of smart devices may not be so universal, suggesting the need for active intervention such as the HabITec Lab. Exposure to devices within the safe HabITec Lab environment is likely to contribute to the successful and sustained uptake of AT in the community.

There were many learnings in the pilot implementation of the HabITec Lab clinical service. Having dedicated and knowledgeable staff was critical to ensure that issues are given sufficient time and resources to be appropriately followed-up. Further, having a physical space, with infrastructure (e.g., devices) and that enables safe trialling of different setups, was a benefit. As a first pilot implementation of a service, we had limitations in the amount of staffing and devices available that restricted patient access, suggesting that more resources would be required to meet current needs, especially when considering our service mostly reached only within spinal patients.

Finally, more broadly, as technology is advancing, therapists working in the healthcare industry need to partner with technical experts such as engineers, designers and IT consultants to create individualised and bespoke solutions to enhance their quality-of-life. For therapists and people with disabilities to have the time, resources, and opportunities to connect with technical experts is consistent with recommendations by health [Citation11, Citation32] and technical [Citation33, Citation34] researchers alike. Earlier engagement in the technology design process, through co-design in particular, has been suggested [Citation13, Citation22] and should be further investigated in the near future, e.g., providing frameworks to better support genuine stakeholder engagement.

Study limitations

This was an exploratory study with a small sample size and based in a tertiary hospital. Most participants were currently inpatients in rehabilitation following SCI, and the majority were male. Therefore, generalisability of the findings is limited to the context of this study site and those who were referred. Furthermore, due to qualitative interviews being conducted in two different manners (i.e., face-to-face interviews for inpatients and telephone interviews for outpatients) the quality and depth of information may have differed between interviews due to the presence of nonverbal communication and the potential to create a stronger rapport for face-to-face interviews. Finally, information around the number of sessions that individuals who received a repetitive practice intervention was not collected, limiting the ability to relate outcomes to the amount of practice performed.

Future research

Future research would benefit from in-depth exploration of clinician perspectives, and patients who received only one-off educational sessions or bespoke solutions. Future research would also benefit from exploring the ways in which people with cognitive impairment can be more widely included in the HabITec Lab.

Conclusion

This study has shown that participants valued the role of the HabITec Lab and were not gaining similar knowledge and experience elsewhere in their rehabilitation journey. The exposure to technology in the HabITec Lab was eye-opening to participants, but more importantly, had the potential to be liberating and motivating. By enabling participants to see a new future and a pathway supported by technology, the HabITec Lab offered both hope and practical support to rehabilitation participants. It was also seen as a sustainable element to which they could refer in future when they negotiated technology in the community. However, participants warned about the challenges of not promoting the service to staff and patients and not adequately resourcing the service to provide exposure to a wide range of options and expertise.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to acknowledge Ms Mary Whitehead, Director of Occupational Therapy at the Princess Alexandra Hospital, for her contributions to the design and development of HabITec; the occupational therapy students who provided repetitive practice interventions; and Ms Kate Knudsen who assisted with the interviews.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Raja DS. Bridging the disability divide through digital technologies 2016 [cited. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/123481461249337484-0050022016/original/WDR16BPBridgingtheDisabilityDividethroughDigitalTechnologyRAJA.pdf.

- Khasnabis C, Mirza Z, MacLachlan M. Opening the GATE to inclusion for people with disabilities. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2229–2230. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01093-4.

- World Health Organization. Assistive technology 201810 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/assistive-technology.

- Larsson Ranada A, Lidstrom H. Satisfaction with assistive technology device in relation to the service delivery process-A systematic review. Assist Technol. 2019;31(2):82–97. doi:10.1080/10400435.2017.1367737.

- World Health Organization. World report on disability 2011 [cited. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564182.

- World Health Organization. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Global report on assistive technology2022cited. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049451.

- Jacob C, Sanchez-Vazquez A, Ivory C. Social, organizational, and technological factors impacting clinicians’ adoption of mobile health tools: systematic literature review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Feb 20;8(2):e15935. doi:10.2196/15935.

- Gallego G, Fowler S, van Gool K. Decision makers’ perceptions of health technology decision making and priority setting at the institutional level. Aust Health Rev. 2008 Aug;32(3):520–527. doi:10.1071/ah080520.

- Musselman KE, Shah M, Zariffa J. Rehabilitation technologies and interventions for individuals with spinal cord injury: translational potential of current trends. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2018;15(1):40. doi:10.1186/s12984-018-0386-7.

- Kendall E, Oh S, Amsters D, et al. HabITec: a sociotechnical space for promoting the application of technology to rehabilitation. Societies. 2019;9(4):74. doi:10.3390/soc9040074.

- Alqahtani S, Joseph J, Dicianno B, et al. Stakeholder perspectives on research and development priorities for mobility assistive-technology: a literature review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2019 Sep 19;16(4):362–376.

- Brouns B, Meesters JJL, Wentink MM, et al. Why the uptake of eRehabilitation programs in stroke care is so difficult-a focus group study in The Netherlands. Implement Sci. 2018 Oct 29;13(1):133.

- Proffitt R, Glegg S, Levac D, et al. End-user involvement in rehabilitation virtual reality implementation research. J Enabling Technol. 2019;13(2):92–100. doi:10.1108/JET-10-2018-0050.

- Edmonds WA, Kennedy TD. An applied guide to research designs: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. 2017 2023/04/26. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc. Second Edition. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/an-applied-guide-to-research-designs-2e.

- Kendall MB, Wallace MA. Measuring goal attainment within a community-based multidisciplinary rehabilitation setting for people with spinal cord injury. Edorium J Disability Rehabil. 2016;2:43–52.

- Martin KE, Cox RJ, Kendall MB, et al. Leisure therapy: exploring leisure-specific goals and outcomes in a spinal cord injury rehabilitation unit. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2017;24(6):263–267. doi:10.12968/ijtr.2017.24.6.263.

- Gu Y, Warren J. Methods for descriptive studies. 2017. In: Handbook of eHealth evaluation: an evidence-based approach [internet] [internet]. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: University of Victoria. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481606/.

- Nayar S, Stanley M. Qualitative Research Methodologies for Occupational Science and Therapy 2014.

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In: denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Nierling L, Maia M. Assistive technologies: Social barriers and Socio-Technical pathways. Societies. 2020;10(2):41. doi:10.3390/soc10020041.

- Glegg SMN, Levac DE. Barriers, facilitators and interventions to support virtual reality implementation in rehabilitation: a scoping review. Pm R. 2018 Nov;10(11):1237–1251 e1. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2018.07.004.

- Kaye HS, Yeager P, Reed M. Disparities in usage of assistive technology among people with disabilities. Assist Technol. 2008;20(4):194–203. doi:10.1080/10400435.2008.10131946.

- Svoboda E, Richards B, Leach L, et al. PDA and smartphone use by individuals with moderate-to-severe memory impairment: application of a theory-driven training programme. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2012;22(3):408–427. doi:10.1080/09602011.2011.652498.

- Evans JJ, Wilson BA, Needham P, et al. Who makes good use of memory aids? Results of a survey of people with acquired brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003 Sep;9(6):925–935. doi:10.1017/S1355617703960127.

- Fager SK, Burnfield JM. Patients’ experiences with technology during inpatient rehabilitation: opportunities to support independence and therapeutic engagement. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2014 Mar;9(2):121–127. doi:10.3109/17483107.2013.787124.

- Wentink MM, Prieto E, de Kloet AJ, et al. The patient perspective on the use of information and communication technologies and e-health in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018 Oct;13(7):620–625. doi:10.1080/17483107.2017.1358302.

- Jamwal R, Callaway L, Ackerl J, et al. Electronic assistive technology used by people with acquired brain injury in shared supported accommodation: implications for occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80(2):89–98. doi:10.1177/0308022616678634.

- David ME, Roberts JA. Smartphone use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Social versus physical distancing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jan 25;18(3):1034. doi:10.3390/ijerph18031034.

- Baldassin V, Shimizu HE, Fachin-Martins E. Computer assistive technology and associations with quality of life for individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2018 Mar;27(3):597–607. doi:10.1007/s11136-018-1804-9.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Household use of information technology 2018 [cited 2021 10 June]. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/technology-and-innovation/household-use-information-technology/latest-release#data-download.

- Greenhalgh T, Maylor H, Shaw S, et al. The NASSS-CAT tools for understanding, guiding, monitoring, and researching technology implementation projects in health and social care: protocol for an evaluation study in Real-World settings. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(5):e16861. doi:10.2196/16861.

- Collinger JL, Boninger ML, Bruns TM, et al. Functional priorities, assistive technology, and brain-computer interfaces after spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(2):145–160. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2011.11.0213.

- Armannsdottir AL, Beckerle P, Moreno JC, et al. Assessing the involvement of users during development of lower limb wearable robotic exoskeletons: a survey study. Hum Factors. 2020 Jan 13;62(3):351–364. doi:10.1177/0018720819883500.