ABSTRACT

In this paper I am reflecting on ‘asking for help’ as a mental health patient. I use myself as a case study to consider the process and what needs to be addressed to make it easier.

I am a 40-year-old woman with lived experience of mental ill health and experience of the services and support available for patients. I accessed support from my teenage years until the present day. The COVID-19 crisis saw my managed symptoms rapidly decline and me needing to seek help once more, but I was saddened and shocked to find that reaching out is as lonely and stigmatised as it was when I was 18. I was also disappointed to recognise the same lack of empathy I received all those years ago by those who were supposed to listen. Many new initiatives and services are now available, but very little has progressed in the experience of the patient.

Using my lived experience, I have spent time reflecting on what I feel we need to do to make it easier to ‘ask for help’. Most high-profile mental health campaigns encourage us to ‘talk’ (Keane Citation2019), however, I believe energy must be directed towards two other steps: making the journey to seek support easier and making the quality of the interaction with that support consistent. This relates to accessing support in the workplace as well as seeking help via National Health Services.

The current journey

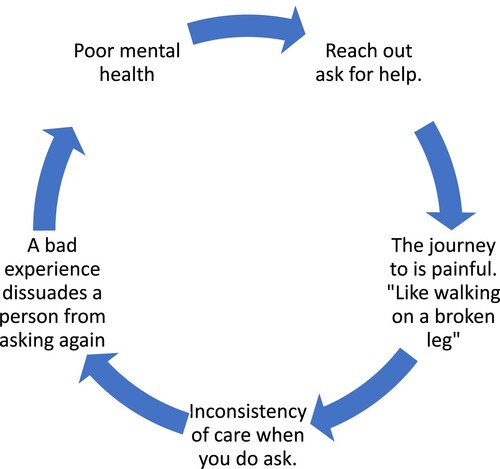

Support for patients suffering mental ill health relies entirely on a patient’s willingness to seek help themselves. Mental ill health is an ‘invisible illness’ – it is not obvious to others (Vickers Citation1997). Asking a patient with an illness of the mind to find enough strength to reach out is as difficult as it would be for a patient with a broken leg to walk to a hospital. We need our leg in order to walk; in the same way we need our mind in order to say what is wrong with us. If the mind is in distress, it will hinder our ability to be rational and articulate. It’s important to acknowledge how hard the journey currently is for mental health patients. Why are we expecting them to make this journey alone?

My life – 1998

At 19 I suffered what I now know was a nervous breakdown. One day at college I felt so overwhelmed that I left the building. I was scared and nervous someone would stop me and make me stay. I left and never returned. I stayed indoors barely talking to anyone, hiding in a room, and choosing my times to go to the bathroom. My days consisted of sleeping and staring mindlessly at the TV. I don’t remember much of it, just that they were the worst days of my life. After a while my boyfriend took me to the GP for which I will be forever grateful. I wouldn’t have been able to do it on my own. I could barely speak to the doctor. I was lucky I had my boyfriend there to speak for me. Despite how severely I was presenting I was just sent away with Prozac and signed off work and my college course. I remained isolated at home with the same symptoms, but now medicated. I wasn’t checked on or followed up, I simply got repeat prescriptions. I hated going to the GP, it became an activity with no real purpose, a chore, a box I ticked with no sense of progress. I don’t remember knowing what was wrong with me, it was never discussed, even with my boyfriend. The last GP appointment I remember was when I mentioned I wanted to go to university. The GP told me that he didn’t think it would be possible because of my severe social anxiety. I graduated from my degree in 2003 with a 2:1. I have never been good at being told what I can or can’t do. It was clear to me if I didn’t try to change my life I was destined to stay in that room with the TV. I was very poorly when I went to college, and it was a huge challenge. Since then, I spent my life in and out of formal care for my mental health. The symptoms have changed and fluctuated over the years, and I have embarked on the many treatments like Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), group therapy and advocacy groups. I have watched over the years as mental health has evolved and the condition I kept hidden is now more freely talked about. The current labels I carry are bipolar and emotional unstable personality disorder.

My life – 2020

COVID-19 hit us all in March 2020. In the UK as in many places, life and society had to be changed and controlled in order to protect lives. The dramatic change to daily life took its toll. My symptoms were managed through structure and routine and the first lock down saw things change significantly. I worked all day online at home in a very small space with a toddler and my furloughed husband. The coping mechanisms I had developed to get by dissolved. My mental health deteriorated, my mood fluctuated, and I experienced longer deeper lows. My thoughts were harder to control and old bad habits like self-harm and purging returned. I tried other ways to help myself like yoga and morning runs (to get a hit of endorphins), but I still found myself struggling to stay afloat. I was sinking, no longer in control. I was scared. I didn’t want to go back to a time when my mental health controlled me.

Asking for help during COVID-19

Twenty years on, and my nervousness at visiting GPs is much the same. I never see the same GP twice, unlike the 90s when it was possible to get to know them and not have to repeat yourself every visit. I put off making the call for as long as I could. I wouldn’t think twice about phoning if I had a chest infection but explaining that is easier than having to explain the pain in my head. The fear is always that you won’t be believed. My first task was to book a phone appointment, (COVID meant no in-person appointments). The process was typically tough. The receptionist asks, ‘what’s the reason for the appointment?’ How do you find the words to explain what’s happening to you? I feel suicidal. I’m self-harming. It takes confidence to declare that to a faceless lady on the phone. I nearly hung up, I felt so exposed and vulnerable. It is vital that the first contact is open and non-judgemental, as it may hinder the patient’s willingness to persist (see ). Once through that embarrassing hurdle I then had the phone call with the doctor, which I had to do alone. I couldn’t have my husband there for support. I was alone in trying to articulate my pain. It was horrible. There are no words to explain the shame I felt. The outcome … … I was sent away and asked to visit the local self-referral mental health support system online, which meant another phone assessment, on my own (Mindmattersnhs.co.uk. Citation2021). I was then asked if I would like to join an online CBT group, but I was told that this group wasn’t ideal for patients that identified with bipolar. By this point I was so desperate for help I was willing to try it. It was all that anyone was offering. I was working all day online, and then joining a weekly two-hour CBT group online. That soon took its toll on me. I was anxious in the lead up to a session and getting upset when I couldn’t concentrate and follow the slides. It was making me feel worse. My husband encouraged me to let the host know how I felt, but I was worried about his perception of me. I sent him an email to explain. He emailed back and was quite understanding. He discharged me from the group back to the GP. So, I no longer had the anxiety of engaging online, but it meant I no longer had any form of support. I was back to square one. No one followed up my discharge from the group in which I continued to be open and honest about my low mood, self-harm and purging. I felt all I could do was carry on alone. I asked for help, it didn’t work, so what else was there?

Improving the journey

The key to mental health support is encouraging people to ‘talk’, but currently the onus for asking for help is left entirely with the patient. No assistance is offered in doing this. In fact, due to COVID-19 the option to take someone with you has gone along with in-person GP appointments. We need to reassure people with mental ill health that they don’t need to seek help alone. Most high-profile mental health awareness campaigns encourage us to talk, the charity Heads Together even have a national ‘Time to talk day’ (Heads Together Citation2017). Talking is the key to getting the support, but it isn’t easy. ‘It’s time to talk’ and ‘It’s good to talk’ are great slogans, but they all need refining. It’s time we added to these famous strap lines: ‘It’s time to talk – I know that’s hard to do, let me help you’.

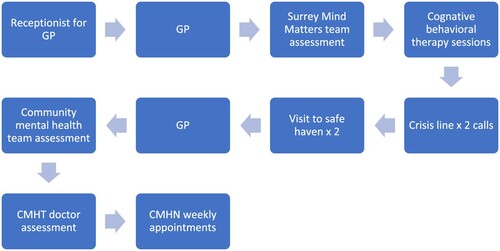

If we as a society want people to actively seek help, we have to make the process more positive and less frightening. We expect our mental health patients to repeat very painful information to multiple people. They might open-up to a mental health first-aider at work, then be sign-posted to a GP (via a receptionist), then a referral to a community mental health team. There they are assessed by a nurse, and then maybe a doctor. In my most recent journey to get the help I had no less than 10 encounters over the course of 4 months. I had to repeat 10 times that I felt suicidal and was self-harming. I can’t express how much strength and resolve I had to find and how exposed and embarrassed I felt. Had it not been for my husband spurring me to continue, I would have given up. But not everyone has this strength, not everyone has my husband. How many people have given up because the process is simply too painful? The graphic below outlines the many stages of my journey ().

Asking for help – round 2

Life post CBT group didn’t improve. I felt despondent and ashamed that I couldn’t complete the sessions. I felt like I had failed. My mental health continued to decline, and my behaviour was very erratic. I remember with great sadness a walk with a bag of tablets that I never planned to return from. I had strong suicidal urges that I was struggling to control. I don’t know where I found the strength, but I phoned my local crisis line. The lady I spoke to was everything you would want from someone tasked with listening to people at their worst. Her tone was calm. She listened, encouraged me to talk and acknowledged the pain I was in. With her I didn’t feel stupid. She gets the credit for getting me back home from that walk. As an existing patient that call was logged and flagged on my notes somewhere. I would love to say that my GP followed up, but they didn’t. I went on to call the crisis line again. I also visited the local safe-haven on two occasions (Sabp.nhs.uk. Citation2021) – an out of hours support service for people in crisis or emotional distress. Thankfully they still offered face-to-face support. The first time I was alone, the second time was with my husband. I found myself in a room unable to speak, overwhelmed and in distress, very much like I was in 1998. It was the saddest place I had been in a long time. Two crisis line calls, and two safe-haven visits should have been enough for someone to realise I needed help. The irony was that by this time I was feeling so low that I was in no position to help myself. My husband did all the talking for me. It was his persistence that eventually got me another appointment with the GP. This time I was finally referred to the community mental health team. I fear for my fate had I been alone.

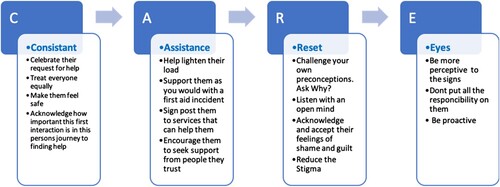

Consistency of first line communication

If mental health patients finally manage to ask for help, the next hurdle is dealing with the inconsistencies in their interactions with the people tasked with ‘listening’. The quality of these first-line interactions is crucial in making the patient feel safe and willing to continue their journey to obtain support (see ). If it goes badly, if they are met with someone who isn’t concentrating or is distracted or is abrupt, this can exacerbate their condition. A huge responsibility lies with anyone involved in that first-line listening interaction, whether you are a receptionist, a help line, a doctor, a MHFA at work, a family member or friend. If a person is brave enough to divulge something so deeply personal and painful, it’s important to acknowledge how brave that journey has been for them and reward them with our empathy and understanding. The role of the first listener is crucial in creating a positive onward journey for the patient ().

Figure 3. The ‘Care Model’ devised by Mig Burgess. This model helps people listen to someone who is opening up about their mental health. It provides guidance us we embark on listening, offering support, and sign-posting people on towards the help they need.

Asking for help versus people listening

As well as professional help from my doctor, I also tried to seek help and support in my place of work. Managing work while my mental health declined was a major challenge. The demands of work in an ever-changing COVID-19 environment added another layer of stress to my overloaded mind. You are encouraged to let someone know if you are ‘not ok’. The slogan is ‘it’s ok to not be ok’ (Guardian Citation2020). I take issue with this, because it really isn’t ok to not be ok. In a work environment to admit you’re not okay is to admit you’re not coping, and thus your capability and performance is judged. When your livelihood is at stake you are understandably reluctant to admit you’re not managing. If it was hard to ask for help from my GP, it was 10 times worse to find the courage to admit I wasn’t ok at work. I was already tired and bruised from the professional care system, but now I had to tackle it all again in the workplace. Talking is difficult for me when I’m not well but I find if I write down my thoughts and feelings, they are more ordered and considered. Sometimes when trying to talk, my emotions become overwhelming. I spend a lot of mental energy trying to contain them for fear of crying, and as a result what I am saying isn’t always clear. In a work environment it’s therefore more tempting to send an email, which is the method I adopted to first let my employers know about my situation. In hindsight my carefully considered emails will have just joined a multitude of others, their content merged with work-related activities and lost in the ever-increasing traffic from the pandemic. I often wonder if my painstakingly written emails made me seem ‘not so bad’. The email certainly didn’t convey the same despair and dysfunction as the people at the safe-haven saw, but did I really want people at work to see that vulnerable side of me? Email, the format that worked for me and helped me to communicate perhaps wasn’t the best channel for my line managers. The response I got was probably to be expected, but for me it was still deflating. ‘Thanks for letting us know, do keep continuing to reach out as needed’. I did reach out, or I tried to, and it took resolve and strength to do it as I was scared and worried about what they would think of me. Would they think I couldn’t do my work? It took me weeks to write that email, and days to find the will to push ‘send’. I did reach out … … … but did anyone listen? Or was I just not clear enough?

One bad response was enough (see ). I had tried, it didn’t work, and I didn’t have the energy or inclination to try again. The problem with asking for help at work is that the people there lack the training that health care professionals have. I was aware that the people I was reaching out to were feeling the effects of COVID themselves and had their own worries and stresses. There was surprisingly little inquiry around my ever-declining mental health, which to me was obvious from my demeanour and work. I often wonder if anyone noticed? Or if during COVID people were just consumed in their own worries and workloads. The journey to asking for help in the workplace was also rife with bureaucracy: an occupational health review to see if I was fit for work – a scary hour of talking; a stress indicator test from HR – tick box forms which were hard to focus on and made me anxious about filling them in correctly. How honest should I be? All the while I am increasingly concerned about being judged on my capability. I won’t go into details about the meetings and conversations that followed. Mistakes were made on both sides, and it just highlights how much more work needs to be done on wellbeing in the workplace.

Writing this has been very emotional for me, recalling my journey during this COVID year has taken me back to painful places. Even as I write, I’m fighting back tears. I needed help, I wasn’t well, and my journey to get that help was a minefield of lonely assessments and repeated conversations with people that offered little support or empathy. I would never have got through it alone.

Now

I am pleased to report that I am now on medication and under the weekly care of my community mental health team. I was also offered employment support from a charity helping people with mental health issues in the workplace. It gives me help with both communicating and dealing with my emotions at works. I initially felt ashamed that I needed this level of support but looking back I wasn’t well and needed it badly. This charity is one of several great new initiatives being offered to mental health patients (Richmond Fellowship and Mental Health Charity Making Recovery Reality Citation2021).

I am more stable, with a safe system in place for my care, and working to regain balance and structure in my life. This pandemic year has battered me and left me fragile and weak. I am not bitter about my experiences though. I have been angry and upset but now I am just sad that so much more work needs to be done to improve access and support, both in the health care system and in our day-to-day lives. We have some great new initiatives available now that I didn’t have in the 90s, but we have a big task ahead of us if we really want to make a cultural change in attitudes towards mental health. When did we lose the ability to talk and recognise the well-being needs of ourselves and those around us? The pandemic has changed social norms and the structure of how we communicate. Mental health has declined as a result of the decisions our government has taken to keep us safe. Instead of dwelling on this turbulent year, I have tried to analyse my experiences. We can only hope to improve if we prioritise talking and sharing. So many things this year could have gone better for me, but rather than ruminate, I have joined the growing modern movement to talk and share. I hope that I can be a part of the cultural change that puts mental health on a par with physical health.

Summary

To treat a person who isn’t well we must first be aware of the problem. Therefore, we must ask those with mental ill health to reach out and ask for help if they need it. The bigger thing to reflect on however is why many people with mental health ill health don’t feel they can reach out. What is holding them back? And what can we do to make the journey easier?

Making the journey easier

By acknowledging that the process is difficult – like walking with a broken leg. It will take time to change the attitudes of people who are tasked with listening. Keeping this in mind may help us to be more proactive in looking for signs that someone needs help. It might also lead to us thinking more creatively about how we can make the journey easier and less bureaucratic.

We could offer a safe wellbeing email for staff so that they can write down their thoughts instead of speaking them out loud. Perhaps patients can have their initial conversation recorded in some way, call it ‘request for help statement’, so that they don’t have to repeat it to multiple doctors and specialists on their journey. Perhaps we can start to look at reducing the complex lines of bureaucracy for patients – even one less step would make it easier.

Armed with knowledge that asking for help isn’t easy I’m sure we can look at the process and come up with many small but affective ideas that can make the journey more attractive and less daunting.

Making sure the quality of the interaction is consistent

Acknowledging the importance of how the first line of listening is managed and striving to make sure that the quality is consistent. Every patient deserves to get the same quality of experience when asking for help. We must strive for this quality control, making sure that each person is offered the same level of empathy and understanding. Education and training are vital in the mission to better equip us in listening, offering support and signposting people to trained professionals. The rollout of the Mental Health First Aid scheme highlighted the need for more work in this area. For many it became an easy fix. The underlying message of the training is lost due to it being something of a tick box exercise (RR1135 – Summary of the evidence on the effectiveness of Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training in the workplace, Citation2021). A change in culture requires the majority to be involved. One lone advocate can get lost in a sea of people not committed to essential change. We must also accept that not everyone takes naturally to the listening role. Sometimes knowing that you are not the right person and removing yourself from the process makes for a safer, more consistent journey for those seeking help.

Too much energy and focus has been spent on awareness campaigns centred on encouraging people with poor mental health to ‘talk’. Talking is a difficult when your head isn’t working properly. It’s time to make asking for help easier and strive to make sure that the first interaction people have, when they are brave enough to talk, is consistently kind and understanding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mig Burgess Walsh

Mig Burgess Walsh is Senior Lecturer in lighting on the Theatre Production course at the Guildford School of Acting part of the University of Surrey. She is also a trustee and Co Chair of the Association of British Theatre Technicians (ABTT), and a trustee of the Backup Tech charity for the entertainment industry. She is a qualified Mental Health First Aid instructor and is a passionate advocate for staff well-being in the backstage theatre and live events industry, having authored several industry guidance notes on well-being. Her practice based research uses her production design skills to work on creative projects with partners in the social science fields to create visually stimulating research around the topics of mental health and well-being. She lives with Bipolar disorder and is passionate in her pursuit to see well-being develop in the workplace and promote more awareness on mental health.

References

- Guardian. 2020. “Psychologist Tells Frontline NHS Staff “it’s OK not to be OK.” [Online] The Guardian. <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/25/psychologist-tells-frontline-nhs-staff-its-ok-not-to-be-ok>.

- Heads Together. 2017. It’s Time To Talk! [Online]. <https://www.headstogether.org.uk/timetotalkday/>.

- Hse.gov.uk. 2021. RR1135 - Summary of the evidence on the effectiveness of Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training in the workplace [Online]. Accessed March 12, 2021. <https://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrhtm/rr1135.htm>.

- Keane, L. 2019. “7 Mental Health Campaigns That Made A Difference | GlobalWebIndex.” [Online] GlobalWebIndex Blog. Accessed November 1, 2020. <https://blog.globalwebindex.com/marketing/mental-health/>.

- Mindmattersnhs.co.uk. 2021. Mind Matters: Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust. [Online] Accessed March 12, 2021. <https://www.mindmattersnhs.co.uk>.

- Richmond Fellowship | Mental Health Charity Making Recovery Reality. 2021. Richmond Fellowship | Mental Health Charity Making Recovery Reality. [Online] Accessed March 12, 2021. <https://www.richmondfellowship.org.uk>.

- Sabp.nhs.uk. 2021. Safe Havens: Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust. [Online] Accessed March 12, 2021. <https://www.sabp.nhs.uk/our-services/mental-health/safe-havens>.

- Vickers, M. H. 1997. “Life at Work with “Invisible” Chronic Illness (ICI): The “Unseen”, Unspoken, Unrecognized Dilemma of Disclosure.” Journal of Workplace Learning 9 (7): 240–252. doi:10.1108/13665629710190040.