ABSTRACT

Most professionally-qualifying youth work programmes in the UK are secular programmes in mainstream universities. Current UK National Occupational Standards require youth workers to ‘Explore the concept of values and beliefs with young people’. Faith organisations form the largest sector of the UK youth work field and all youth workers need to be equipped to work inclusively with diverse communities. This research explored, through a semi-structured survey sent to programme leaders, the coverage of religion, faith and spirituality in youth work training courses in England. We found tensions in how religion, faith and spirituality are incorporated into programmes and how programme leaders think youth workers should engage with it in their practice. Where explicit content on religion, faith and spirituality is incorporated into training programmes, it tends to focus on controversial issues such as radicalisation. The survey revealed a lack of consensus across programme leaders as to how the NOS relating to values and beliefs should be interpreted and whether their graduates are being sufficiently equipped to work with diverse religious communities. The research exposes a need for more explicit recognition of the place of religion, faith and spirituality in youth work and in the curricula of secular training programmes.

Introduction

The UK is one of very few countries that have a professional qualification for youth workers, that is equal in level and status to that required for social work. Youth workers in the UK are professionally qualified if they have an undergraduate or postgraduate degree endorsed by the Joint Negotiating Committee for Youth and Community Work (JNC).Footnote1 The National Occupational Standards (NOS) for youth work are UK-wide and must be mapped to JNC-recognised programmes in order for them to meet validation requirements.Footnote2 The NOS are reviewed every few years, and before 2012, included reference to supporting young people’s spiritual development. Whilst this was removed in 2012, a standard requiring youth workers to ‘facilitate young people’s exploration of their values and beliefs’ (YW14) remained. In the 2019 review, the wording changed slightly to ‘Explore the concept of values and beliefs with young people’ (YW06).Footnote3 The current NOS also require youth workers to ‘Develop a culture and ethos that promotes inclusion and values diversity’ (YW19). Specific social justice issues are not highlighted in the NOS but youth work training programmes have a tradition of being underpinned by concerns about social justice and equalities.

The QAA (Citation2019) subject benchmark statement for youth and community work does have some explicit references to religion, despite its absence from the NOS. However, the statement is ‘general guidance’ and ‘not part of regulated requirements’ (QAA Citation2019, 1) and therefore differs from the NOS in the extent to which it must be embedded in programmes, as the NOS are done so in-depth as part of PSRB requirements. The subject benchmark statement recognises there are degree-level courses which combine study of youth work with theology and includes a couple of these in its example titles list. There is also a link to CYWT, a specifically Christian youth work training website, for information on faith-based courses (reflecting the fact that all current faith-based JNC-recognised courses are Christian). Faith-based-youth-work is also listed as one of the areas of existing literature that underpin courses. The statement recognises spirituality as one of the aspects of holistic wellbeing for young people, despite that spiritual development was removed from the NOS in 2012. The statement also recognises students are expected to engage in ‘situated learning’ and lists some defining criteria of such learning including ‘local, global and metaphysical, formal and non-formal, including global learning, environmental learning and theological or faith-sensitive learning’ (QAA Citation2019, 12). It also notes in the criteria that such learning will use ‘characteristic methods of informal education, which require practitioners to locate their practice within a matrix of power dynamics across local, global, political and faith boundaries’ (QAA Citation2019, 12). This supports the inclusion of discussion of religion and faith on youth work programmes. Within such discussions, however, remaining both faith-sensitive and open to exploring the power dynamics inherent in discussions of faith, arguably requires skilled facilitation. Other mentions of religion in the statement recognise key tensions. For example, one of the key ethical debates for youth work is described as ‘whether ideological modifiers of the terms “youth work” or “informal education” (such as Catholic; socialist; Islamic; feminist; Quaker; Jewish) enhance or detract from the understanding of the core practices’ (QAA Citation2019, 6). In another part of the statement, forms of discrimination facing young people and communities are listed including ‘age-based discrimination, sexism, racism, sectarianism, and/or practices rooted in class privilege’ as well as ‘disability discrimination or sexuality-based oppression’ (QAA Citation2019, 11). Here, it is observed that sectarianism, which as a form of potential discrimination is commonly understood as being enacted from within or by religious groups, is raised as an issue while there is not mention of discrimination against religious groups. This is surprising given the inclusion of protection from religious discrimination in policy through the Equality Act (Citation2010). This suggests, alongside the absence of religion in the NOS, that religion may be seen as either problematic or irrelevant to youth work practice by some influential stakeholders in the broadly secular field.

Youth work in the UK is provided by local authorities, community groups or charities and faith-based-organisations. Christian youth work has formed the largest part of the UK youth work sector since at least the early 2000s, prior to austerity measures in the statutory sector (Brierley Citation2003). There are also well-established Muslim and Jewish sectors (Khan Citation2013; Marsh Citation2015). Additionally, there are smaller sectors in other faiths such as Sikh (Singh Citation2011) and Buddhist (Bright et al. Citation2018). While, internationally, the UK has been seen as a leader in the field for its post-war government-funded-youth-services, recent years have seen significant cuts to statutory youth work, with the closure of 760 youth centres and the loss of 4,500 youth workers in less than a decade (YMCA England & Wales Citation2020). Jeffs (Citation2015) suggests the only way secular youth work can survive is through the development of cooperative partnerships, including with the faith-based sector.

Despite some limited evidence of these faith-based and secular practice partnerships in recent years, there is historic and ongoing separation of religious and secular youth work training, both in the UK and beyond (Thompson Citation2019). While students of faith may engage with secular courses, training for faith-based-youth-work (other than Christian) has not been well-established through qualifying courses. In the UK, training has either been established within the faith sector itself (through organisations such as Reshet,Footnote4 a Jewish youth work network, for example) or not well-established at all due to the small and voluntary nature of the sectors. The exception to this is the larger Christian sector where qualifying courses have been developed such as those included in our research. Previously, there were also some Muslim youth work pathways on qualifying programmes (Bardy et al. Citation2015) but none currently exist. Of 27 higher education, JNC-recognised providers in England, listed in 2019 by the National Youth Agency (NYA), four offered Christian-specialist programmes, and the rest offered secular programmes.

The professional training of all youth workers needs to equip them to work with diverse religious communities. Faith-based-youth-work has a history of outreach beyond the religious community (e.g. the Sunday School movement’s origins in offering basic education to young people in working class communities) (Thompson Citation2018). Today, many Christian youth workers are working with young people who are not part of the church as well as those who are (Thompson Citation2018). Similarly, secular youth workers are engaging with young people from diverse religious, cultural and ethnic backgrounds.

Suspicion of faith

Most professionally-qualifying-youth-work-programmes in England are located in mainstream universities, the culture of which is dominantly secular (Dinham Citation2018). It is recognised that youth workers need to engage in critical reflection on their values and faith-positions and engage in critical dialogue with others, in order to become aware of the agendas they bring to their practice and develop as ethically-sound practitioners (Green Citation2010; Harris Citation2015). However, Cooper (Citation2008) argues there are tensions inherent in the process of ‘teaching values’ in universities, because of the diverse ways students interpret the content of youth work programmes. If religion, faith and spirituality are neglected in youth work training, it is likely these tensions will not become explicit or visible in order to be dealt with through critical reflection and dialogue.

In one example, Bardy et al. (Citation2015, 101–102) recount their experiences of working as lecturers on secular youth work programmes where actual or perceived hostility toward Christian faith from students or tutors meant ‘Students often kept quiet about their faith, rationalising that this was a personal matter despite the likelihood that their faith values would influence their youth work practice’. They argue that the removal of spiritual development from the NOS in 2012 reinforced the separation and dialogue needs to be more effectively facilitated between students with and without religious beliefs. Through research with faith-based and secular youth workers engaged in partnership-working, Thompson (Citation2019) found suspicion of each other was a barrier in these relationships. However, suspicion was reduced through the dialogue and collaboration facilitated by such partnerships and a range of shared values were established.

This suspicion is also located within criticisms of faith-based-youth-work from its secular counterparts, highlighted by a range of youthwork scholars (Brierley Citation2003: Bright et al. Citation2018; Green Citation2010). Harris (Citation2015) suggests faith-based and secular youth work come into conflict where there is a clash between ‘religious’ and ‘secular’ values. This is important in light of a tendency for critics to ascribe value-positions or ‘agendas’ to faith-based-youth-work without recognising that ‘no youth workers are ideologically blank and devoid of personal values’ (Green Citation2010, 130). Similarly, Bright et al. (Citation2018) argue problematic agendas can be implemented by states, religious bodies or other stakeholders and that youth work is ‘never fully neutral’. Faith-based-youth-work has been rightly subject to scrutiny, particularly around proselytisation and some approaches to issues of gender and sexuality (Bright et al. Citation2018). However, secular youth work has also, at times, been scrutinised for suppressing rather than empowering young people’s engagement in social and political processes (Coburn Citation2011; Garasia, Begum-Ali, and Farthing Citation2016). The assumption the secular worldview is neutral or superior may lead to a lack of engagement with faith issues in professional-youth-work-training and foster continued suspicion of faith-based-practices.

Anti-oppressive practice

Research shows that religion can be viewed either as antithetical to anti-oppressive-practice (AOP) (e.g. through issues of indoctrination and fundamentalism) or as one of the core and intersectional issues of social justice and identity that needs attention within AOP (Collins and Wilkie Citation2010; Vanderwoerd Citation2016). The secular nature of much university training means the first of these is more likely.

Collins and Wilkie (Citation2010) argue religion is neglected as a social issue within AOP training, while Crisp and Dinham’s research (Citation2019a) shows there is minimum engagement with religion as part of AOP training within social work in a range of countries. In research exploring the disconnection between AOP and spirituality in higher education in Canada, Shahjahan (Citation2009, 121) describes a ‘secular chilly climate’ in universities. The study found that ‘racially minoritized’ academic staff in particular are required to leave their ‘spiritual selves at the door’ and not bring engagement with spirituality into their teaching (Shahjahan Citation2009, 121), reflecting how issues of exclusion may intersect in the secular culture of universities. It is internationally recognised that there is complexity in interpreting and implementing AOP by professionals with religious faith where certain issues, such as those around gender and sexuality, are in tension with religious beliefs (Todd and Coholic Citation2008; Vanderwoerd Citation2016). For this reason, Todd and Coholic (Citation2008) argue space for critical reflection on personal belief systems is needed in social work training. This arguably also applies to youth work.

Religious literacy

There is international recognition that university training for the public and social professions needs to develop cultural competency in graduates so they can work effectively with diverse cultural, ethnic and religious groups (Larson and Bradshaw Citation2017; Levin-Keini and Ben Shlomo Citation2017), especially where minoritised groups face barriers to accessing mainstream public and social services (Smith, Jennings, and Lakhan Citation2014). Further, Dinham (Citation2018) argues that people working in the public professions specifically need to develop a ‘religious literacy’ to engage sensitively and effectively with diverse religious groups. Dinham’s conception of religious literacy frames it as the knowledge and ability of such practitioners to understand, discuss and engage with a range of faith positions – and how they intersect with social and political concerns. Within this, it is arguable that religiously literate professionals would be able to recognise nuance and tension, resist polarisation and deficit assumptions – and, as such, work effectively with people from a range of faith backgrounds. However, training for these professions is largely not equipping graduates with this religious literacy due to a lack of engagement with religion on such programmes (Crisp and Dinham Citation2019b). In a review of social work training in universities internationally, Crisp and Dinham (Citation2019a, 1544) found ‘Religion and belief appear briefly and incoherently and are often deprioritised, unless particularly problematic’ suggesting coverage of religion on secular programmes may be dominated by negative framings.

There is a clear argument for youth workers to develop such religious literacy in order to effectively work with diverse religious groups. They should also be equipped to work with faith-based-youth-workers, and alongside or within faith-based-organisations, many of whom are seeking to engage with civil society (Thompson Citation2019). Without a level of religious literacy, interventions with young people may be misplaced and overly punitive as with some interventions emerging from UK counter-terrorism legislation, for example (Pihlaja and Thompson Citation2017). Interventions might also not occur where they are needed. Mirza (Citation2010) found young Muslim women may be let down by services where professionals’ inertia and fear of appearing intolerant leads to them not following up on issues of concern, such as around forced marriage and, female genital mutilation. In these examples of interventions with Muslim young women, ethnicity, gender and religion intersect in ways that affect how and whether young people receive support.

People’s faith identities are not isolated from other elements of their lives and identities such as their race, gender and sexuality. The broader notion of cultural competence might encompass these issues but religion has often been neglected in AOP, and a secular culture persists in universities and youth-work-training. Youth-work-training curricula should not neglect issues of religion, as youth workers may well work within or alongside faith organisations and all youth workers need to be equipped to work sensitively and inclusively with diverse communities.

Research methods

The main method of this study was a semi-structured online survey sent to programme leaders of the 38 JNC-qualifying youth work programmes in England in 2019, which represented 27 different Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). We contacted programme leaders directly (according to the NYA’s list published on their website). Of the 38 programmes listed in 2019, 28 were undergraduate and ten were postgraduate. Of the 27 institutions, 23 were HEIs offering mainstream programmes and four were Christian-specialist-institutions.

Our aim was to receive a response from all 27 English providers. As such, we sent three reminders over the one-year-period in which the survey remained open. We also sent the survey out via the mailing list of the Professional Association of Lecturers in Youth and Community Work (TAG/PALYCW) in case programme leaders had changed from those listed. This mailing list reaches academics in all subscribing institutions offering JNC-recognised courses in the UK. We also contacted colleagues in HEIs that hadn’t responded that we knew from our professional networks.

In total, the survey received 30 responses from programme leaders, representing 25 of the 27 English institutions (22 secular and three Christian HEIs). One of the two institutions it did not reach (a Christian provider) had closed. The survey’s 30 respondents represented 24 undergraduate and six postgraduate programmes. 55.2% of respondents identified their personal faith perspective as Christian, 17.2% as Atheist and 13.8% as Humanist. Other respondents identified as Buddhist, Hindu, Agnostic and ‘other’.

For the purposes of this study, we defined each training programme as either a secular programme (i.e. religion, faith and spirituality may feature but are not dominant features of the programme, and the programme is not focused on a particular religious tradition) or as a single-faith programme (i.e. religion, faith and spirituality are dominant features of the programme, and the programme focuses on a particular religious tradition). As well as applying these categories ourselves, programme leaders identified with them consistently when asked in the survey. We also provided an option for courses to identify as a ‘multi-faith programme (i.e. religion, faith, non-religious beliefs and spirituality are dominant features of the programme, and the curriculum incorporates diverse religious viewpoints)’ but no one chose this option.

The sample size was limited by the number of JNC-recognised programmes in England, but participants engaged well with open questions, providing rich qualitative data alongside the quantitative data. Having gathered data from 30 of the 38 possible programmes and 25 of the 27 English institutions offering youth work training, we are confident the research provides a robust picture of religion, faith and spirituality on JNC-recognised programmes in England.

The mixed-methods data elicited by the survey was subject to thematic analysis, with the rich qualitative data provided by participants offering nuance and meaning to the quantitative findings. These themes were coded according to how they featured in qualitative commentary (and not just in the closed, quantitative questions). Whilst we focus primarily on the survey findings in this paper, it is worth noting that we also conducted an analysis of the programme pages for youth-work-courses available on university websites, to assess what was stated (if anything) about religion, faith and spirituality in programme content and this triangulated our survey data.

Findings

In this second half of the paper, we begin by presenting some of the contextual quantitative data from the survey on the coverage of religion, faith and spirituality on youth-work-training-programmes. Following this, we discuss our findings under the inductive themes that emerged from our analysis, these being:

The secular culture of youth work training

Disproportionate negative coverage of Islam

An emphasis on personal beliefs and values

Religion, faith and spirituality are covered informally

Dialogue (and discomfort) are prioritised as learning contexts

More scope for equipping students to work with diverse religious communities

The issues are complex, raising questions of power and its uses in training

Coverage of religion, faith and spirituality

The survey asked a number of questions about how religion, faith and spirituality are covered (or not) in training programmes.

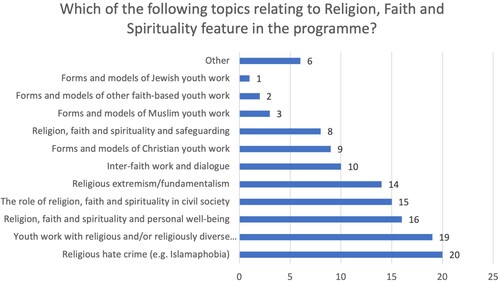

reveals a variety of ways that religion features in youth work programmes. More generalised issues such as hate crime, diversity, wellbeing and extremism appear to receive more coverage than specific examples and models of faith-based-youth-work. Of the religious traditions with established youth-work-sectors, Christianity was most explicit on programmes. This in part reflects the four Christian-specialist-training-programmes, as well as that over half of respondents identified as Christians themselves. It also likely reflects the size of the Christian sector and its place as the dominant religion in the UK. There was little coverage of Jewish and Muslim youth work across the programmes despite these having established youth work sectors. The six responses to the ‘other’ category predominately included theological topics specific to the Christian-programmes such as ‘missiology and ecclesiology’.

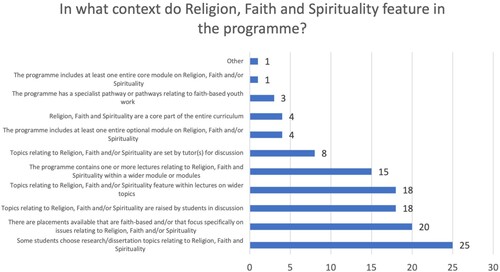

The survey also asked in what context these topics emerge on the programmes (see ).

Only the four Christian programmes identified religion, faith and spirituality as a core part of curricula. Across secular programmes, the dominant contexts in which they were covered were through students’ dissertations, placements and student-led discussions. This suggests some students want to engage with religion and are choosing to do so in optional contexts despite it not being a core part of teaching.

Over half of secular programmes reported having some ad hoc lectures and/or reference to religion, faith and spirituality during lectures on broader topics. No secular programmes had a core stand-alone module. Two secular programmes had a specialist pathway and three had at least one optional module. This largely correlates with what we found in the analysis of programme webpages.

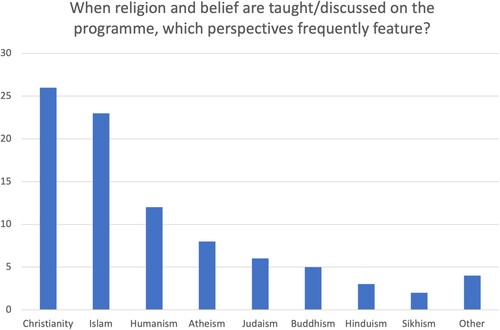

Respondents were asked which religious perspectives feature most frequently on their programmes (see ).

As with above, Christianity had more coverage than other religious perspectives, affected in part by the four responses from Christian-specialist-programmes. It is notable that a frequent coverage of Islam was identified and yet only three programmes stated they cover Muslim-youth-work (see ). This suggests Islam features in relation to some of the other topics identified in , such as hate crime (Islamophobia) and extremism.

The question about which perspectives feature was followed by a question asking respondents why they thought particular perspectives featured most. The most common answer was that they reflect the perspectives of students. Secondly, respondents identified that they reflect contemporary concerns- this likely relates to the coverage of issues like Islamophobia and extremism. The third most common answer was that it reflects perspectives of staff and this likely relates particularly to the frequent coverage of Christianity (55% of respondents identified as Christian). It is encouraging in some sense that coverage of religious perspectives is primarily student-led. However, not including religion significantly in core teaching () means perspectives that emerge will reflect dominant experience and not a diversity of perspectives. This exclusion risks leaving to chance that students are equipped to work with diverse religious communities and to understand more marginalised perspectives.

The secular culture of youth work training

Programme leaders recognised the secular nature of programmes and some were keen to justify that such programmes had been developed because they had broad appeal. Some programme leaders specifically articulated why secular programmes had been developed at universities with faith-based roots:

Although the University has a faith base and strong links to the Church of England … we opted for a generic secular programme because this appears to fit the demand and is most likely to recruit. (Christian respondent 3/secular programme)

The absence of religious perspectives in curricula may contribute to the feeling among some programme leaders that students are not always comfortable to discuss their faith positions (see section on dialogue and discomfort below for data on this). One respondent explained that one reason students may not be comfortable was because ‘there tends to be a secular culture on the programme’ (Christian respondent 1/secular programme). This statement implicitly recognises that secularity has its own culture. Other respondents also problematised notions of secularity as a neutral or ‘progressive’ position. Arguably, the absence of religion, faith and spirituality in core teaching may reinforce it as taboo or uncomfortable, as well as reinforcing secularity as the dominant frame.

Disproportionate negative representation of Islam

As observed in and , the survey data suggests that where Islam is covered in course material it is more often represented in relation to negative issues than the contribution of Muslim-youth-workers to the sector. This resonates with Crisp and Dinham’s (Citation2019a) finding on secular social work programmes across a range of countries that where religion features, it is usually with negative connotations. This was reinforced in qualitative answers to open questions in the survey (and reinforced by our website analysis) with ‘Islamophobia’ and ‘radicalization’ mentioned as some of the only specific examples of teaching around religion, faith and spirituality. These polarised issues position Muslims as either victims or perpetrators of violence and exclusion. If Islam features in these more negative contexts at the expense of exploring the practices and models of Muslim-youth-work, then a rebalancing may be needed to ensure alternative perspectives are shared that do not reinforce popular framings of Islam as problematic.

There was some recognition of the potential impact of this kind of framing in youth work training. For example, one respondent stated:

We also have a pathway dedicated to Radicalisation which explores working with oppressive and potentially damaging values and beliefs in young people (not necessarily related to religion). (Christian respondent 2/secular programme)

An emphasis on personal beliefs and values

The survey asked whether respondents thought the (pre-2019) NOS YW14 to ‘facilitate young people’s exploration of their values and beliefs’ sufficiently represented the place of religion, faith and spirituality in youth work practice. 37.9% of respondents responded ‘yes’ to this question; 34.5% responded ‘no’; and 27.6% were ‘not sure’. This demonstrates the majority of course leaders either felt it was not sufficient or were uncertain. Despite this, an emphasis on personal values and beliefs was more prevalent than specific content on religion across secular programmes, clearly influenced by the requirements of the NOS.

The survey asked respondents how they interpreted NOS YW14 to ‘facilitate young people’s exploration of their values and beliefs’. One respondent explained they had a core module focused on personal values and beliefs.

[T]he programme has a module that allows/encourages students to explore their own personal journeys, values and beliefs that underpin their community and youth work practice as well as the importance of values and beliefs in the lives of others. (Humanist respondent 1/secular programme)

This is central to the experiential approach in the delivery of the course. Their values and beliefs are constantly explored in core modules such as weekly group work and specific modules in equality areas. (Buddhist respondent 1/secular programme)

Religion, faith and spirituality are covered informally

There was a sense among programme leaders that through broader teaching on AOP, discussion and understandings of ‘values and beliefs’ naturally emerge. There were several comments suggesting this from programme leaders.

Directly through the teaching of ethics, and the implementation of anti-oppressive practice throughout the programme. Students are encouraged to reflect on their values and those of others drawing on placement experience. (Hindu respondent 1/secular programme)

This standard would be met predominantly through fieldwork practice. Students would be exploring their own values and beliefs through the dialogue and inputs contained within the curriculum before engaging with young people and communities … This would be in the anticipation that they would involve the people they work with in such dialogue. (Christian respondent 1/secular programme)

We interpret this as a more holistic perspective of supporting people to understand themselves and what they believe are important values to live by, this includes faith but is not limited to faith. Thinking is more in line with asking critical questions of self about who you are and how you act in the world. (Atheist respondent 4/secular programme)

Dialogue (and discomfort) are prioritised as learning contexts

The survey asked how comfortable programme leaders thought students from religious backgrounds feel to discuss their faith in group settings on the programme. In contrast with the experience of Bardy et al. (Citation2015), 66.7% of respondents answered either ‘comfortable’ or ‘very comfortable’, with the other third answering ‘uncomfortable’, ‘very uncomfortable’ or ‘unsure’. The survey also asked how often students spontaneously raise issues of religion, faith and spirituality during lectures, seminars and tutorials. The majority said this happened ‘sometimes’ (63.3%) with 26.7% of respondents replying ‘frequently’ and 10% saying ‘rarely’. No one said this never happened. This does suggest that some students are comfortable to raise the topic, even where it is not explicitly taught.

There was a confidence among some programme leaders that diverse backgrounds of staff and students ensured religion, faith and spirituality would emerge in reflections and discussion. Several respondents suggested NOS YW14 was covered through group discussion. One stated they ‘expect students to be able to explore and discuss spirituality and what spirituality might look like in practice from religious and non-religious perspectives’ (Humanist respondent 2/secular programme). Another stated ‘The team are from diverse backgrounds including faith, which supports the diverse dialogue’ (Atheist respondent 5/secular programme).

Given that one third of respondents felt religious students were either uncomfortable or they didn’t know how comfortable they were to discuss their faith in group settings, it may be unrealistic to expect personal values and beliefs to emerge in dialogue. At the least, it puts emphasis on the skills of course leaders, to overcome potential discomfort becoming a barrier to students sharing freely. However, when explaining their responses to this question, several respondents explained that dialogue was important even where discomfort was present.

Students of faith report that they are very comfortable to discuss this, but there is a counter issue here, students from non-faith positions appear to have many more issues about feeling comfortable to discuss their viewpoint, especially if perceived as being critical of faith. However, this is a fluid state and does not stop debate from emerging. (Atheist respondent 3/secular programme)

There are some students who wrestle with concepts of faith and youth work, but this is encouraged as it forms a good critical discussion. (Christian respondent 2/secular programme)

The programme team place a lot of emphasis on creating a safe environment for students to explore and be aware of self in relation to others. That said conversations about difference including discussion about faith can be uncomfortable. (Respondent identified their religious perspective as ‘other’/secular programme)

We do not merely accept but challenge all views and perspectives and we insist that the focus is the principles and values of community development and youth work. People who have strong religious views especially around their homophobic beliefs find it very uncomfortable. (Atheist respondent 1/secular programme)

Fear of being excluded, labelled judgmental or challenged from others in the class. The course tends to focus on supporting minority groups in society, and people with strong faith don't seem to be considered as much in this category, even though they can be isolated in secular circles/communities/cultures. Faith, it seems, is to have its own place in faith circles such as when with friends from church and is to be expressed in those spaces rather than in a classroom where diverse views are present. I've found that there is also an overriding view that secular is viewed as progressive, youth workers now aiming to address issues without having to bring in or acknowledge faith and beliefs. For example, as a group of students challenged with a case study/scenario of young people disagreeing on issues of sexuality due to their faith, all students in the classroom referred to them accessing LGBTQ services for support … but none mentioned spiritual guidance and exploring elements of faith with the young people, thinking about how young people are wrestling with big questions such as the meaning of life. I've found that working with these meta-ethical questions with young people gets overlooked. (Christian respondent 10/secular programme)

Another respondent noted ‘the secular culture on the programme’ as the reason for students’ discomfort. The respondent quoted earlier in this section who outlined how students of faith may experience exclusion also raised the ‘overriding view that secular is viewed as progressive’ as problematic. The same respondent went further to state students with faith would struggle on youth work training programmes.

Anyone with a faith going on this youth work course, and probably most youth work courses today will need a lot of support. I am being as fair as I can be when I say this because I know it is hard to get the balance right. I am writing this as a person of faith who wants to help young people thrive in life and I believe faith has a vital role to play in youth work and I acknowledge its value. (Christian respondent 10/secular programme)

More scope for equipping students to work with diverse religious communities

The survey asked how well-equipped respondents felt their graduates are to engage with young people from diverse religious and non-religious backgrounds on issues of religion, faith and spirituality. A minority (6.7%) felt their graduates were ‘very well equipped’ and 53.3% felt they were ‘sufficiently equipped’. However, 10% felt they were ‘insufficiently equipped’ and 6.7% felt they were ‘very poorly equipped’, with a substantial proportion (23.3%) being ‘unsure’ how well equipped their graduates were. These responses demonstrate that while 60% of course leaders feel their graduates are equipped to engage with young people from diverse religious and non-religious backgrounds on issues of religion, faith and spirituality, two-fifths are not confident this is the case. There was also a lack of confidence (as outlined earlier) that NOS YW14 sufficiently represented the place of religion, faith and spirituality in youth work, with only two fifths confidently stating that it did. This demonstrates no clear consensus across programme leaders that the NOS and the curricula of training programmes were sufficient to equip youth workers to work with diverse groups of young people around issues of religion, faith and spirituality. A substantial minority of respondents felt the NOS and curricula of training programmes were not going far enough.

Most course leaders felt religion, faith and spirituality were relevant to youth work training and that youth workers need to be equipped to work with diverse religious communities.

Many of our trainee youth workers are not only from faith backgrounds but work with young people from faith backgrounds … youth workers will find themselves engaging with young people from a variety of faiths and non-faiths … I bring this into discussions because I believe that they are live issues that students need to engage with in their work roles and as such I feel that they should feature more in JNC-validated programmes. (Christian respondent 8/secular programme)

This has prompted me to reflect that we need to review and discuss the relevancy of these areas for the programme. (Buddhist respondent 1/secular programme)

You have given me pause for thought about the extent to which we include discussions about this important issue … as I do not believe our graduates are adequately prepared to engage with young people about religion and spirituality. (Atheist respondent 2/secular programme)

It’s hard to put into words, as it’s so sad that this is in question for this sector. I think it’s vital that youth workers engage with faith in some way, at very least know a trusted qualified youth worker with a faith background who can offer young people spiritual guidance. (Christian respondent 10/secular programme)

Based on my experience, youth workers are capable of judging when and how to engage, based both on needs of a particular group/individual, and also as part of a balanced curriculum. (Christian respondent 3/secular programme)

The issues are complex, raising questions of power and its uses in youth work training

Participants were asked to choose a statement that best reflected how they think youth workers should engage with religion, faith and spirituality in their practice. 50% thought ‘youth workers should proactively engage with issues of religion, faith and spirituality in their practice’, followed by 23.3% agreeing that ‘youth workers should only engage with religion, faith and spirituality when issues are raised by young people’. A minority (13.3%) thought they should proactively engage but only ‘within the context of clear limits and/or guidance’. Two people (6.7%) were not sure and two (6.7%) chose the ‘other’ category: one explaining that ‘it depends on the context in which the youth worker is employed’ and one raising issues with the wording used in the question and its possible responses. No respondents felt ‘youth workers should avoid engaging with religion, faith and spirituality’. Some raised issues with the question in their explanation for their answers. Use of the word ‘should’ was identified as problematic given the need for youth work to start with young people’s agenda, as well as issues with how such engagement might be approached (such as through proselytisation). One participant highlighted it as more complex than an ‘either/or’ answer. The responses demonstrate respondents broadly agreed youth workers should engage with issues of religion but recognised tensions in how this is sometimes undertaken.

The lack of consensus on whether programmes are sufficiently equipping students to work with diverse religious communities reflects the complexity of how the issues are interpreted by programme leaders and how they think they should be engaged with by youth workers. Respondents described this complexity and articulated a lack of certainty in answering closed questions on such complex issues. For example, one respondent explained why they answered ‘not sure’ to the question about whether the NOS YW14 sufficiently represented the place of religion, faith and spirituality in youth work.

I answered ‘not sure’ to your question ‘Do you think standard YW14 sufficiently represents the place of religion, faith and spirituality within youth work practice?’ This is because it completely depends on the reader of the standard- this was part of the debate 10 years ago when ‘spirituality’ was removed from the last edition of the NOS. YW14 does represent those who want to explore religion and faith – ‘values and beliefs’ can represent anything, and youth workers with no belief are not expected to work on spirituality or religious belief, but evangelists can bring it to the forefront. (Christian respondent 5/Christian programme)

Youth workers need to be open to discussing issues that young people raise, and utilise every resource available to them in order to help young people in their care to better understand and act in/on the world. We should respect the fact that young people will have been brought up in different values systems to our own, some of which will be based on religious teaching. We should openly acknowledge where there is conflict between our professional values-base and the values systems of the young people in our care, and work with this difference to promote a socially just world. I don’t believe that youth and community work practitioners should promote any form of religion (as that becomes ‘ministry’); however, we should work through and with faith communities in a respectful and collaborative manner to help young people shape their futures as compassionate human beings. (Atheist respondent 2/secular programme)

If ‘proactive’ is being presented as ‘actively promote’ as might be inferred here then no. If proactive is proactive about the role and value, positive in relation to voice and choice and supportive of awareness and tolerance, then yes. Proactive is key, but the personal position also raises the concept of agenda. (Atheist respondent 3/secular programme)

I think Youth Workers should be able to engage young people with all issues of importance for them, enabling them to explore and make informed choices etc … this should be a professional judgement (but not proselytizing). (Agnostic respondent 1/secular programme)

Some respondents on secular programmes highlighted that youth workers of faith should not be assumed to be well-equipped to deal with diversity of belief.

My observation is that there is an emotional maturity and insight needed to be inclusive of other faiths and non-faith and that celebrates human experience within a wider context, that this is not automatic, but acquired and maintained. However, what is automatic and/or strongly known/believed can be highly problematic as confirmation bias and limiting in practice. Many students who are very capable and secure in their own faith/non-faith may not therefore be sufficiently equipped to work in the same way across a diverse spectrum of beliefs. (Atheist respondent 3/secular programme)

It should as it reflects perspectives that feature in their work with communities and workers should not merely accept whatever religious dogma people propose without it being linked to the core values of our profession. (Atheist respondent 1/secular programme)

Discussion

The research raises questions about what religious literacy in youth work training might look like. Religious literacy is more appropriately viewed as a skill that youth workers need to develop rather than standardised curriculum content to be packaged into all youth work programmes. Whilst knowledge is of course important to being religiously literate, it is arguably less about defined content and more about the ability to engage and discuss with nuance, sensitivity and to effectively navigate areas of tension and challenge. Youth-work-training-curricula need to incorporate a range of religious perspectives and provide space for critical dialogue about the issues. Incorporating more explicit teaching on religion would ensure such critical discussions are not left to chance and that they go beyond deficit perceptions and dominant perspectives. Religious worldviews should not be framed as more or less problematic or relevant (through how they are covered or not) than secular, political or other worldviews.

The QAA (Citation2019) subject benchmark statement for youth and community work and the youth work NOS (NYA Citation2020) offer some (limited) support for such critical dialogue. The subject benchmark statement makes clear that the situated learning that takes place in youth-work-training should be faith-sensitive and able to grapple with the inherent power dynamics of religious, political and other positions. The NOS require youth workers to be able to explore values and beliefs with young people. However, it is arguable that the emphasis on personal values and beliefs that programmes tended to incorporate, according to our findings, does not enable students to reflect beyond their own experiences, or those offered by others in their class, to engage with more marginalised perspectives. This arguably does not fully support NOS YW06 (formerly YW14). It does not ensure that students have the religious literacy to support young people to explore the full range of values and beliefs they may be grappling with, let alone equip students with the knowledge of a range of perspectives beyond their own for them to be able to engage with diverse religious communities.

The majority of programme leaders did not feel the NOS standard on values and beliefs sufficiently reflects the place of religion and faith in youth work. We have argued that the NOS and the QAA subject benchmark statement do not go far enough to support youth workers to develop a religious literacy with a tendency for religion and faith to be almost entirely absent (as in the NOS) or framed as problematic (as alluded to by the subject benchmark statement). Similarly, we found an absence of core teaching on religion and faith across secular youth work programmes and a focus on deficit perspectives where they did feature, with Islam in particular featuring in this way.

As this is an issue across public and social professions including both social work and youth work (Collins and Wilkie Citation2010; Crisp and Dinham Citation2019a; Citation2019b; Vanderwoerd Citation2016) there is a need for policy, practice and training pertaining to all forms of work with young people to recognise the need for religious literacy and for religious discrimination to be taken as seriously as other oppressions so that it is not neglected in such training. A renewed emphasis on the requirements of the Equality Act (Citation2010) to include religion as a protected characteristic throughout these sectors could support sector bodies and stakeholders, including the training, standards and endorsement bodies developing the NOS and subject benchmark statements for a range of social and public professions to recognise they are obliged to incorporate this more effectively alongside other issues of oppression and inequality. As the neglect of religion in such training is found to be international (Crisp and Dinham Citation2019a; Todd and Coholic Citation2008; Vanderwoerd Citation2016) these implications also have clear resonance beyond the UK.

In UK youth work, the NOS are a key area for change given how deeply embedded in and mapped they are to the modules of youth-work-qualifying-programmes in order to be validated. The NOS could also better reflect how youth work engages with other (often intersecting) issues such as racism, homophobia, disability discrimination and sexism. However, our website analysis found that programme curricula were under-pinned by a commitment to equalities and social justice, with these other issues covered more frequently and explicitly (see Thompson and Shuker Citation2021). Disability discrimination is another potentially neglected area but this would require further research to clarify.

There is a particular complexity around whether religion and faith are a form or focus of oppression in AOP training, which has arguably led to the issue being neglected (Collins and Wilkie Citation2010; Crisp and Dinham Citation2019a; Vanderwoerd Citation2016). Overall, there is a need for programmes to find space for nuanced perspectives and, at times uncomfortable, dialogue, and to avoid the absence of engagement with religion and faith or the presence of only polarised or deficit perspectives. This is what the concept of religious literacy encapsulates (Dinham Citation2018), and it is the opportunities for informed and nuanced dialogue that will equip students to work sensitively and appropriately with diverse religious communities – as well as to challenge and engage with tensions when necessary.

There are some limitations to our study. Most particularly, the quantitative data relies on a relatively small sample – with this sample being limited by the number of HE youth work training programmes in existence in England. There are some also implications for further research. Whilst the survey elicited rich qualitative data, this could be developed further through focus groups and/or interviews with programme teams, engaging with staff beyond the programme leaders targeted by this study. It would also enhance the findings to engage with students and graduates of youth work programmes for their perspectives on the content of their programmes and how well equipped they feel to engage with diverse religious communities. The research could also be expanded to the other nations of the UK who share the same NOS, despite having different validating committees for youth work training programmes and differing policy contexts for youth work practice.

Conclusion

Youth work training programmes in English universities are teaching broad issues relating to social justice, AOP, and diversity. The specific issue of religion appears, however, to be neglected across secular programmes, not included in core curriculum content, and presented as an option or specialism rarely, meaning engagement with it is not compulsory for trainee youth workers. Where it is more explicitly covered, there is a risk of a disproportionately negative focus on issues such as hate crime, exclusion and radicalisation, largely in relation to Islam. Christian-youth-work receives some coverage in a substantial proportion of secular programmes.

Equipping youth workers to engage with diverse religious communities should not be left to chance. If issues of religion, faith and spirituality are not explicitly covered in youth work training, youth workers may not develop the religious literacy they need to engage with the issues outlined here. There is a danger of youth workers reinforcing problematic assumptions, either informed by their religious beliefs or about others with religious beliefs, if they do not engage explicitly with religion. Arguably, optional modules and ad hoc lectures are not sufficient to ensure all youth workers, regardless of their personal faith position, are equipped to understand and work with young people and professionals from diverse backgrounds. A dominantly secular culture is likely to inhibit reflection on secularity as a subjective worldview in itself and make it more likely that religion is approached narrowly where it does emerge.

The place of religion as part of students’ critical dialogue and reflection was highlighted across programmes, facilitated at least to an extent by programme staff. This demonstrates that the need for this engagement (Green Citation2010; Harris Citation2015) is at least partially being met. However, there are some issues around who feels comfortable to engage in such discussions and whether minority voices are heard. A lack of explicit teaching on religion to feed into discussions risks excluding at least some perspectives and issues. Disproportionately negative teaching around religion may also impact on whether students feel comfortable to engage in discussions about their personal faith positions. We argue youth-work-qualifying-programmes could do more to focus positively and explicitly on religion, faith and spirituality and on ensuring diverse youth work contexts are included in their curricula. Within this, space for potentially uncomfortable discussions where there are tensions between different belief systems or practices is also needed.

Overall, this research raises questions about how youth workers in England might be better equipped by their university training programmes to work with diverse religious communities and with the faith-based sector. Youth workers need to develop a religious literacy (Dinham Citation2018) to work with the largest sector of their field and with the diverse religious young people they will engage in their practice. A broader and more explicit recognition of religion, faith and spirituality, as well of other specific social justice issues and how these intersect, in the NOS would support this. These findings have wider relevance to how youth workers are trained beyond the English context, as well as in the broader social professions, in order for trained social professionals to be equipped to work with diverse communities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Naomi Thompson

Naomi Thompson is a Senior Lecturer in Youth and Community Work and Head of the Department of Social, Therapeutic and Community Studies at Goldsmiths University of London.

Lucie Shuker

Lucie Shuker is Head of Research at Youthscape, Luton.

Notes

1 While introductory youth work courses at lower qualification levels do exist, they do not provide students with the JNC-recognised professional qualification but provide youth support worker status. This means they are not eligible for jobs requiring a youth work qualification. A new level 6 apprenticeship route to qualification was recently introduced for those who wish to qualify as youth workers through a vocational route. This had not been launched when we conducted our research.

2 Education and Training Standards (ETS) committees in each nation of the UK validate their youth work qualifying programmes with JNC recognition and provide contextualisation documents for the interpretation and application of the NOS for the particular country (NYA Citation2020). A Joint ETS committee (JETS) for the UK and Ireland with representation from each country’s ETS oversees validation and standard-setting processes. In England, university training programmes receive their JNC-validation via the ETS committee that sits within England’s National Youth Agency (NYA).

3 This change happened during our research project therefore the survey we conducted referred to the pre-2019 standard (YW14).

References

- Bardy, H., P. Grace, P. Harris, J. Holmes, and M. Seal. 2015. “Finding a Middle-way Between Faith-Based and Secular Youth and Community Work Courses.” In Youth Work and Faith: Debates, Delights and Dilemmas, edited by M. K. Smith, N. Stanton, and T. Wylie, 99–114. Lyme Regis, UK: Russell House.

- Brierley, D. 2003. Joined up: An Introduction to Youthwork and Ministry. Carlisle: Spring Harvest Publishing/Authentic Lifestyle.

- Bright, G., N. Thompson, P. Hart, and B. Hayden. 2018. “Faith-based Youth Work: Education, Engagement and Ethics.” In The Sage Handbook of Youth Work Practice, edited by P. Alldred, F. Cullen, K. Edwards, and D. Fusco, 197–212. London: Sage.

- Coburn, A. 2011. “Liberation or Containment: Paradoxes in Youth Work as a Catalyst for Powerful Learning.” Youth & Policy 106: 60–77.

- Collins, S., and Lynne Wilkie. 2010. “Anti-Oppressive Practice and Social Work Students’ Portfolios in Scotland.” Social Work Education 29 (7): 760–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615471003605082.

- Cooper, S. 2008. “Teaching Values in pre-Qualifying Youth and Community Work education.” Youth and Policy 97-98: 57–72.

- Crisp, B. R., and A. Dinham. 2019a. “Are the Profession’s Education Standards Promoting the Religious Literacy Required for Twenty-First Century Social Work Practice?” British Journal of Social Work 49 (6): 1544–1562. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz050

- Crisp, B. R., and A. Dinham. 2019b. “Do the Regulatory Standards Require Religious Literacy of U.K. Health and Social Care Professionals?” Social Policy & Administration 53 (7): 1081–1094. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12495.

- Dinham, A. 2018. “Religion and Belief in Health and Social Care: The Case for Religious Literacy.” International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare 11 (2): 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHRH-09-2017-0052.

- The Equality Act. 2010. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15.

- Garasia, H., S. Begum-Ali, and R. Farthing. 2016. “Youth Club is Made to Get Children off the Streets: Some Young People’s Thoughts About Opportunities to be Political in Youth Clubs.” Youth & Policy 116: 1–18.

- Green, M. 2010. “Youth Workers as Converters? Ethical Issues in Faith-Based Youth work.” In Ethical Issues in Youth Work (2nd ed.), edited by S. Banks, 123–138. London: Routledge.

- Harris, P. 2015. “Youth Work, Faith, Values and Indoctrination.” In Youth Work and Faith: Debates, Delights and Dilemmas, edited by M. K. Smith, N. Stanton, and T. Wylie, 85–98. Lyme Regis, UK: Russell House.

- Jeffs, T. 2015. “What Sort of Future?” In Innovation in Youth Work, edited by N. Stanton, 11–17. London: YMCA George Williams College.

- Khan, M. G. 2013. Young Muslims, Pedagogy and Islam. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Larson, K. E., and C. P. Bradshaw. 2017. “Cultural Competence and Social Desirability among Practitioners: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Children and Youth Services Review 76: 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.034.

- Levin-Keini, N., and S. Ben Shlomo. 2017. “Development of Cultural Competence among Social Work Students: A Psychoanalytic Perspective.” Social Work 62 (4): 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swx035

- Marsh, S. 2015. “On Renewing and Soaring: Transformation and Actualisation in Con- Temporary Jewish Youth Provision.” In Youth Work and Faith: Debates, Delights and Dilemmas, edited by M. K. Smith, N. Stanton, and T. Wylie, 5–22. Lyme Regis: Russell House Publishing.

- Mirza, H. 2010. “Walking on Eggshells: Multiculturalism, Gender and Domestic violence.” In Critical Practice with Children and Young People, edited by M. Robb, and R. Thomson, 43–58. Bristol: Policy Press.

- NYA. 2020. Youth Work in England: Policy, Practice and the National Occupational Standards. Leicester: National Youth Agency. https://nya.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/New-Nos.pdf.

- Pihlaja, S., and N. Thompson. 2017. “Young Muslims and Exclusion – Experiences of othering”. Youth and Policy. https://www.youthandpolicy.org/articles/young-muslims-and-exclusion/.

- QAA. 2019. Subject Benchmark Statement: Youth and Community Work. Gloucester: QAA. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/subject-benchmark-statements/subject-benchmark-statement-youth-and-community-work.pdf?sfvrsn=5e35c881_4.

- Shahjahan, R. A. 2009. “The Role of Spirituality in the Anti-Oppressive Higher-Education classroom.” Teaching in Higher Education 14 (2): 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510902757138.

- Singh, J. 2011. “Sikhing Beliefs: British Sikh Camps in the UK.” In Sikhs in Europe: Migration, Identities and Representations, edited by K. A. in Jacobsen, and K. Myrvold, 253–278. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Smith, M. D. M., L. Jennings, and S. Lakhan. 2014. “International Education and Service Learning: Approaches Toward Cultural Competency and Social Justice.” The Counseling Psychologist 42 (8): 1188–1214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000014557499.

- Thompson, N. 2018. Young People and Church Since 1900: Engagement and Exclusion. London: Routledge.

- Thompson, N. 2019. “Where is Faith-Based Youth Work Heading?” In Youth Work: Global Futures, edited by G. Bright, and C. Pugh, 166–183. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Thompson, N., and L. Shuker. 2021. The Secular Culture of Youth Work Training. Luton: Youthscape.

- Todd, S., and D. Coholic. 2008. “Christian Fundamentalism and Anti-Oppressive Social Work Pedagogy.” Journal of Teaching in Social Work 27 (3-4): 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/J067v27n03_02.

- Vanderwoerd, J. R. 2016. “The Promise and Perils of Anti-Oppressive Practice For Christians in Social Work Education.” Social Work & Christianity 43 (2): 153–188.

- YMCA England & Wales. 2020. “Out of Service: A Report Examining Local Authority Expenditure on Youth Services in England and Wales”. https://www.ymca.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/YMCA-Out-of-Service-report.pdf.