ABSTRACT

Purpose

This study proposes the use of plurilingual audiovisual input, combining viewers’ L2 English audio with an L3 target language subtitles, to facilitate beginners’ acquisition from original version television.

Methodology

We divided 84 beginner learners of Spanish into experimental and control groups, assessing their learning of target single and multiword units using a pre-/posttest design, measured with a Vocabulary Knowledge Scale. The experimental group watched twelve episodes of a TV series in the original L2 English version with L3 Spanish subtitles.

Findings

Statistical analyses revealed that the experimental group was nearly ten times more likely to score higher on the posttest than the control group, demonstrating a strong impact of plurilingual audiovisual input on vocabulary learning. Additionally, multiword units were learned better than single words.

Originality

This study breaks new ground in audiovisual input research by providing empirical evidence that incorporating a plurilingual approach benefits language learning and teaching.

Introduction

Traditionally, second language acquisition (SLA) research on audiovisual input has predominantly centred on language uptake from audiovisual content featuring second language (L2) audio and L2 on-screen text (captions) or L1 on-screen text (subtitles). However, in the context of expanding multilingualism and globalisation, viewers and language learners are now exposed to a variety of audiovisual input modes, including L2 audio paired with L3 subtitles. To investigate the effectiveness of this type of audiovisual input, we propose an alternative approach to studying subtitling – plurilingual audiovisual input.

From a practical standpoint, this type of input is readily available for non-English L1 newcomers to subtitling countries, such as Argentina and the Netherlands, where a newly arrived person would encounter TV programmes in their L2 (English) with subtitles in the local language. In educational settings, plurilingual audiovisual input could be effectively utilised in classrooms with students from diverse L1 backgrounds, using the L2 English soundtrack as a bridge language to promote viewing with the target language subtitles. This way, learners would increase their exposure to the target language from the early stages of learning, resulting in greater amounts of input – particularly crucial in low-input environments (e.g. Muñoz and Cadierno Citation2021).

The theory of pedagogical translanguaging and multilingualism (e.g. Cenoz and Gorter Citation2022) forms the basis of our proposal to study plurilingual subtitled input. Pedagogical translanguaging advocates fully incorporating students’ whole linguistic repertoires, enhancing language learning experiences by leveraging prior linguistic knowledge, such as proficiency in previously acquired languages like English. Additionally, plurilingual subtitled audiovisual input may function as multilingual scaffolding (Duarte Citation2020), establishing meaningful links between more and less known foreign languages.

To date, research on audiovisual input has mainly focused on either monolingual (L2 audio and L2 captions) or bilingual (L2 audio and L1 subtitles) modes, with an emphasis on vocabulary uptake (Montero Perez Citation2022). Surprisingly, there is a dearth of studies comparing the uptake of single words and multiword units (MWUs) from audiovisual input. Addressing these gaps, our study specifically explores the differences in learning single and MWUs from this type of multilingual input.

Learning from audiovisual input

As streaming platforms offer a wide range of foreign-language TV series and films, they have gained popularity among language learners, offering unlimited opportunities for language acquisition (Muñoz Citation2024). This surge in interest has led to development of theories like Vanderplank’s cognitive–affective model of language learning through captioned viewing, which proposes that television provides opportunities for systematic exposure to extensive comprehensible input (Vanderplank Citation2016). Empirically, studies consistently find that audiovisual input has a positive effect on L2 development (Montero Perez Citation2022).

Thus far, most audiovisual input research has focused on single-word vocabulary learning, with limited attention given to MWUs (e.g. Puimège and Peters Citation2019). To the best of our knowledge, no earlier work has compared the learning of single and MWUs within the same intervention. This research gap is not confined to audiovisual input studies but is also a prevalent issue in the broader field of SLA research, despite the recognised importance of MWUs in vocabulary learning (Pellicer-Sánchez Citation2019). Although it seems that the learning of single and MWUs implies similar processes and outcomes (Pellicer-Sánchez Citation2019), Laufer and Girsai (Citation2008) found that, comparing incidental learning of single words and MWUs, the latter elicit higher learning gains. A similar, yet conflicting finding was observed by Miralpeix, Gesa, and Suárez (Citation2023): While their study on learning from a short video presentation (see below) did not directly address the difference between learning single and MWUs, their data showed mixed results, with MWUs appearing in both the top and bottom quartiles of learnt target vocabulary. From this short review, it is evident that more research into the difference in learning single and MWUs from audiovisual input is needed.

Audiovisual input for novice and beginner learners

Despite extensive research on audiovisual input and on-screen text (see Montero Perez Citation2022), there is a considerable lack of research on lower-proficiency level viewers. So far, most studies have focused on university undergraduates with an intermediate proficiency level (Gesa and Miralpeix Citation2022). This concentration on a specific proficiency level could be attributed to the proposed minimum proficiency threshold needed for effective learning from audiovisual input (Danan Citation2004). For instance, an analysis of vocabulary demands of television programmes (Webb and Rodgers Citation2009) showed that a viewer needs to possess a vocabulary size of an intermediate learner to be able to follow a TV show in their target language.

To address the needs of beginner language learners, research has investigated alternative types of audiovisual input that may be appropriate for these learner groups. For instance, through reversed subtitling, with the audio in a learner’s L1 and a subtitles text in learner’s L2 (Montero Perez Citation2022). Previous studies on the effects of reversed subtitling found that participants could access the meaning of L2 on-screen text through the native language soundtrack, and that this can facilitate L2 encoding (Danan Citation2015). This type of subtitling allows viewers to access the content of the video in their L1 and makes a bilingual connection between the first and foreign languages. Research shows that presentation of even a novel language in subtitles leads to its processing, regardless of L1 availability in the audio. For example, d’Ydewalle and De Bruycker (Citation2007) compared subtitle reading while viewing a 15-minute cartoon in a standard subtitle-condition (L2 Swedish audio, L1 Dutch subtitles), and a reversed subtitle-condition (L1 Dutch audio, L2 Swedish subtitles). Using eye-tracking, they found that standard subtitles resulted in lower skipping rates and more frequent fixations, but reversed subtitles still attracted attention for 26% of the subtitle presentation time, even though the language in the reversed subtitles was novel for the participants and there was L1 Dutch available in the soundtrack. Bisson et al. (Citation2014) also used eye-tracking to investigate vocabulary retention comparing various subtitling conditions including reversed subtitles. Their participants watched a series of cartoons (25-minutes in total) with either standard subtitles (L2 Dutch audio, L1 English subtitles), captions (L2 Dutch audio, L2 Dutch captions), reversed subtitles (L1 English audio, L2 Dutch subtitles), or L2 Dutch audio only (no on-screen text). While the eye-tracking measures indicated that participants spent less time reading subtitles in the reversed condition compared to the other conditions, nevertheless a substantial amount of time was devoted to Dutch subtitles in the reversed condition. Bisson et al. (Citation2014) argue that due to automatic reading behaviour and saliency of subtitles in general, subtitles in a novel language will be processed even when the viewer’s L1 is present in the audio. Their vocabulary learning test, on the other hand, did not show any differential effect of viewing in either of the conditions, which the authors explain might be based on the brevity of exposure to audiovisual input or a suboptimal test. Thus, more research is needed to establish to what extent reversed subtitling could facilitate early learners’ language uptake.

Although these studies promise that reversed subtitles can lead to effective processing for novice and beginner learners, this type of on-screen text might not be encountered naturally – besides for English L1 speakers – as the majority of contemporary TV is in English as a main language (Follows Citation2018). Dubbing materials, to achieve this effect for other L1 viewers, could compromise ecological validity. For viewers with non-English L1 backgrounds, when the audio is in English (in the original version of the material) and the subtitles are in the target language, this form of audiovisual input no longer qualifies as reversed subtitling. Instead, it transforms the context into an entirely different audiovisual input mode featuring L2 English with additional language (L3Footnote1) subtitles. Consequently, the empirical question of whether this type of input can facilitate L3 learning arises from its natural availability. We refer to this type of input as plurilingual subtitled audiovisual input.

Plurilingual subtitled audiovisual input

To the best of our knowledge, no previous research has focused on plurilingual subtitled input and tested multilingual approaches (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2022) to learning from audiovisual materials. We are aware of one piece of published research that implemented two foreign languages in the audiovisual input, but this was not framed as a separate type of audiovisual input, nor did the researchers consider the interplay between the two foreign languages in the video. In their first exposure study, Miralpeix, Gesa, and Suárez (Citation2023) looked at the first moments of learning a novice language from audiovisual input. Catalan/Spanish participants with no knowledge of Polish watched a short ad twice (6 min of input) in English with Polish subtitles. The participants were asked to grasp as much as possible from the subtitles. A meaning recognition test of words and expressions showed form-meaning connection learning for about half of the target items, suggesting that it is possible to uptake from minimal exposure to a target language in subtitles. Since the audio in Miralpeix, Gesa, and Suárez (Citation2023) was in the participants’ L2 English and the subtitles were in L3 Polish, the audiovisual input used in the study could be regarded as plurilingual audiovisual input. However, as mentioned previously, the interplay between the two foreign languages was not discussed in the study. The only work we are aware of that took into account the linguistic interaction of plurilingual audiovisual input is Urbanek’s doctoral dissertation (in preparation). As a part of their research, the author examined how the learning of an additional language (L3 Dutch) could be supported by a previously learnt foreign language (L2 English). Participants in this study watched a 15-minute video twice with Dutch L3 audio in a number of on-screen conditions: (a) no on screen text, (b) L1 German subtitles, (c) L3 Dutch captions, (d) L2 English subtitles, and (e) bilingual L1 German and L3 Dutch subtitles. Results showed that for content comprehension the participants in the plurilingual condition (L3 Dutch and L2 English) scored similarly to both groups with L1 subtitles and bilingual subtitles, and higher than groups without on-screen text or with L3 Dutch captions. These findings suggest that English as a bridge language facilitated comprehension similarly to participants’ L1. Urbanek’s findings on comprehension and vocabulary suggest that plurilingual audiovisual input, that is, the presence of two foreign languages in the audiovisual input, did not lead to cognitive overload or split attention (Ayres and Sweller Citation2005), and significantly contributed to learning. While this is a promising result, more research on this topic is warranted. Urbanek’s (in preparation) research investigated three typologically close languages (Dutch, English, and German), and only included participants with intermediate levels of English – both factors which may have influenced learning.

Given the abovementioned gaps in research on the use of plurilingual audiovisual input, our study was guided by the following research questions:

To what extent can plurilingual audiovisual input, that is, exposure to L2 English audio and L3 Spanish subtitles, support vocabulary uptake in the target language (i.e. Spanish)?

To what extent is this vocabulary uptake affected by viewer’s English and Spanish prior vocabulary size, and target item type (single words vs. MWUs)?

Methods

The present study was set out to investigate a novel approach to audiovisual input: Plurilingual subtitled audiovisual input, where viewers watch original version content with L2 English audio and L3 target language subtitles. This is informed by the pedagogical translanguaging theory that suggests learning may be made more effective by integrating the full multilingual repertoire in the learning process (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2022).

Employing a pre-/posttest design, we examined the L3 Spanish vocabulary uptake (single words and MWUs) through audiovisual input in an ecologically valid context of intact Spanish as a foreign language classes at two Dutch universities.

Participants

Eighty-eight first-year undergraduate students (Mage = 17–23) participated in this study. The participants consisted of ten intact classes undertaking the first weeks of an A1 beginner Spanish proficiency course from two Dutch universities, and were majoring in European Languages and Cultures or Business. Both programmes taught in English as medium of instruction requiring an entrance level of at least B2 in English. The beginner learners of Spanish were chosen for this intervention as they have not yet reached the proficiency threshold for learning through the target language captions (Danan Citation2015) and therefore are in need of alternative types of audiovisual input in the target language. A diverse participant pool included 37% native Dutch students and 63% international students from various backgrounds. Four L1 English speakers were excluded from the analysis since the target of the intervention was to examine the interplay of two foreign languages (L2 English and L3 Spanish). Participants from Romance L1 backgrounds (n = 11) were initially considered for exclusion as their L1s were closely related to the target L3 Spanish; however, data exploration revealed their inclusion did not significantly alter the models, and we decided to keep their datasets.

The final analysis included data from 84 participants, five intact classes (n = 49) in the experimental group, and five intact classes (n = 35) in the control group.

The experimental participants’ Spanish level was beginner (M = 10.85, SD = 8.38, range: 0–48), based on the Lextale-Esp vocabulary size test (Izura, Cuetos, and Brysbaert Citation2014) where a score below 12 out of 60 corresponds to a beginner level. Their English proficiency was upper-intermediate (M = 6574.63, SD = 1792.27, range: 1161–9130) measured by the V_YesNo vocabulary size test with a maximum score of 10,000 (Meara and Miralpeix Citation2017).

Control group participants were from the same cohort and of similar levels in Spanish and English (cf. pre-test scores). They only completed the pre-/post-tests on target vocabulary items, while time constraints did not allow for administering the general Spanish and English vocabulary size tests.

Materials

Experimental participants watched twelve episodes (262 min of input) of the first season of the comedy TV series ‘The Good Place’ (Schur Citation2016) in the original version with L2 English audio and L3 Spanish subtitles. Including multiple episodes of the TV series in the intervention was warranted by Vanderplank’s (Citation2016) theoretical underpinning that learning from television is more robust when it is extensive and systematic.

To select the target items, an n-gram analysis in Python (Bird, Loper, and Klein Citation2009) identified frequently occurring single words and MWUs in the Spanish subtitles. We define MWUs as vocabulary items that are longer than a single word (Pellicer-Sánchez Citation2019). Then, the course lecturers, both Spanish teachers with more than ten years of experience in Dutch higher education, excluded items likely to be encountered in language classes and removed English and Dutch cognates. English cognates were not used as they would be similar in the audio and in the subtitles, while Dutch cognates were avoided as the majority language of the participants were expected to be L1 Dutch. This resulted in a list of 50 target items (see Appendix A), deemed challenging enough by lecturers and appearing between 2 and 63 times in episodes. Having a range of frequencies allowed inclusion of more target items leading to a more elaborate analysis of the learning. To those target items, 15 distractors were added, which were familiar single and MWUs likely known to participants by the end of the course. They were added to reduce the number of unknown test items for participants in order to prevent discouragement.

Pre-/posttests of target vocabulary

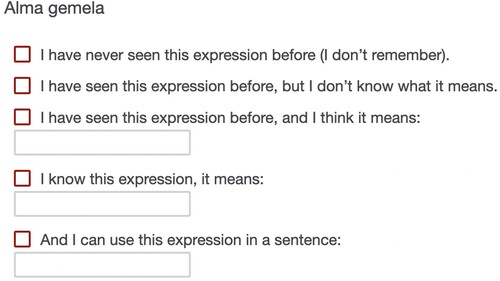

We used a Vocabulary Knowledge Scale (VKS, Wesche and Paribakht Citation1996) implemented in Qualtrics to measure the uptake of the target items (see ). Participants completed the test online by indicating their level of knowledge of each target item, from seeing the item for the first time, to knowing how to use it in a context. While the pretest included 15 distractors, we excluded those in the posttest due to the time constraints. Other than that, the pre/-posttests were identical with Qualtrics presenting randomised item orders automatically. The internal consistency was high for both the pretest (Cronbach’s α = .967) and the posttest (Cronbach’s α = .965), indicating a reliable measurement instrument.

Figure 1. Example of a test item.

We scored participants’ responses based on Wesche and Paribakht’s (Citation1996) guidelines, resulting in an ordinal score from 1 to 5, as summarised in .

Table 1. VKS scoring procedure.

Vocabulary size tests

We used English and Spanish vocabulary size tests to measure proficiency in the two languages.

Previous research has shown that vocabulary size correlates with learners’ proficiency levels (e.g. Miralpeix and Muñoz Citation2018) and our target was vocabulary learning.

As a proxy of English proficiency, we used V_YesNo (Meara and Miralpeix Citation2017), an online receptive vocabulary size test. Test takers were presented with a set of words, one at a time, and had to decide whether they knew that word or not. To control for guessing, non-words are also present in the test, and final scores are calculated penalising false answers and guesses. The results were scored automatically and can be interpreted as follows: beginner (below 2000), elementary (2000–3000), intermediate (3000–5000), upper-intermediate (5000–7000), advanced (7000–9000), and highly proficient (9000–10,000) (Miralpeix, Gesa, and Suárez Citation2023).

We used the Spanish adaptation of the above receptive vocabulary size test (Lextale-Esp, Izura, Cuetos, and Brysbaert Citation2014), built on the same testing procedure, to measure participants’ Spanish vocabulary size. All tests were scored manually following the developers’ formula: score = number of words identified as known – 2*number of non-words identified as known (maximum score = 60). Typically, native speakers reach a score of 54/60 or higher, while a score of 12/60 or less would be of a beginner learner (Izura, Cuetos, and Brysbaert Citation2014).

Procedure

After obtaining ethical approval, the materials and procedure were piloted with a comparable group of participants (n = 6). We considered the pilot intervention successful as the tests showed good internal validity and the participants’ scores increased from the pre- to posttest (see ). In the following, we decided to include those pilot participants in the main analysis as their data were valid and no changes were made to the experiment materials.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the pilot study (N = 6).

During the first two weeks of the experiment, participants signed consent forms, completed the pretest in class, and were given links to complete English and Spanish vocabulary size tests at home. They were instructed not to use any additional materials during the tests, and that the results would not affect their course grades. After that, students watched 12 episodes of the TV series at home during the next four weeks, three episodes per week. To ensure that the participants watched the episodes, we shared the videos through the Edpuzzle platform (Sabrià Citation2013). It allows teachers and researchers to check the viewing progress, blocks fast-forwarding and rewinding, and does not play the video if another internet browser window is opened. Each episode was followed by a short comprehension questionnaire to keep participants’ focus on the viewing task. Finally, in week six participants completed a posttest in class. In order to ensure participation, students were offered the incentive of gaining 10% of the course grade for viewing the episodes. The control group only completed the pre-/posttests with a four-week interval between the tests as part of their regular classes.

Data analysis

For the analysis, each target item (N = 50) was nested within every participant, group, and time. The dataset was in a format where each row represented a unique observation for a given participant, group, target item, and time, which allowed us to model the probability of a correct answer for each participant, group, and target item. The data were organised in a column for each of the above mentioned variables and a column for the learning outcome (a score from one to five, see above). A series of cumulative link mixed models (CLMM) with an ordinal distribution were fitted in RStudio (version 2023.06.1+524) using the clmm function from the ordinal package (Christensen Citation2022). We chose CLMMs for our data analysis because they are designed to analyse the impact of fixed factors on the ordinal outcome variable while accounting for random effects (see Taylor et al. Citation2023).

The estimated marginal means (EMM) were calculated with the emmeans function, and pairwise comparisons were calculated with the pairs function, both from the emmeans package (Lenth et al. Citation2023). Graphs were built using the ggplot2 package (Wickham Citation2016).

In order to interpret the effects of the predictor variables in the clmm, odds ratios were calculated. These represent the change in the odds of the outcome occurring for a one-unit change in the predictor variable (Field Citation2018). To transform the coefficients to the odds ratio scale, the exponential function (exp (estimate)) was used. A resulting odds ratio greater than 1 indicates an increase in the odds of the outcome, while a resulting odds ratio lower than 1 indicates a decrease in the odds.

Results

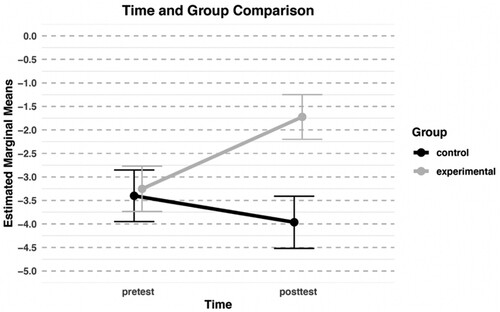

Descriptive statistics for the VKS pre-/posttests (see ) show an increase in the experimental group’s posttest scores, and a decrease in the control group’s posttest scores, as compared to their respective pretest scores. Overall, the descriptive data suggest that, at the moment of the pretest, the experimental and control groups performed similarly, but the experimental group exhibited a higher performance in the posttest.

Table 3. Vocabulary Knowledge Scale descriptives for all 50 items: single (n = 39) and MWUs (n = 11).

Research question 1: the effect of plurilingual input on learning

To answer the first research question we fitted a CLMM to analyse the effects of different factors on the observed scores. This model included the dependent variable ‘Score’, representing the ordinal categorical scores from pre- and posttests, and two independent variables ‘Time’ (pre- vs. post-test) and ‘Group’ (experimental vs. control). An interaction between group and time was also included. To account for potential variability that might not be explained by the fixed effects, the model incorporated random intercepts for each participant and item.

The model revealed that there was a significant effect of time on the test scores (estimate = .562, odds ratio = 1.086, SE = .083, z = 6.699, p < .001), and a significant interaction between time and group (estimate = 2.092, odds ratio = 8.101, SE = .109, z = 19.169, p < .001). The pairwise comparisons of time showed that there was a significant difference between the experimental group’s pre- and posttest scores (estimate = −1.530, odds ratio = 4.618, SE = .068, z = −22.262, p < .001), and the control group’s pre- and posttest scores (estimate = .562, odds ratio = 1.754, SE = .083, z = 6.699, p < .001).

The estimated marginal means (see and ) showed that the experimental group scored higher in the posttest than in the pretest while the control group scored lower in the posttest than in the pretest.

Figure 2. Pretest and posttest comparison of the control (N =35) vs. experimental (N = 49) group.

Table 4. Estimated marginal means.

A group pairwise comparison demonstrated that there was no significant difference between the experimental and control groups’ pretest scores (estimate = −.148, odds ratio = .862, SE = .290, z = −.510, p = .956). In the posttest the experimental group scored significantly higher than the control group (estimate = −2.240, odds ratio = 9.393, SE = .291, z = −7.694, p < .001), with the odds of scoring higher in the posttest while being in the experimental group being 9.39 times higher.

Research question 2: effects of vocabulary size and target items

To answer the second research question only experimental group data were analysed.

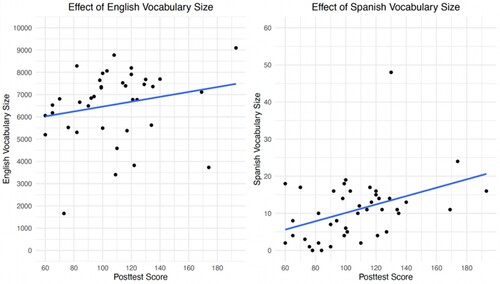

In order to assess the impact of various factors on the scores of the experimental group participants, we fitted a CLMM with score as the outcome variable, time (pre- vs. posttest) as a categorical independent variable, English and Spanish vocabulary sizes as continuous covariates, type of the target items (single word or MWU) as a categorical variable, and random intercept for participants and test items. To fit the model, proficiency variables were transformed to a common scale by subtracting their means and dividing by their standard deviations. To address the range of frequency of occurrence of the target items in the episodes (2 to 63 times), we included it in the analysis but it had no significant effect on the scores (estimate = .006, odds ratio = .993, SE = .014, z = −.044, p = .658), and therefore we removed it from the further analyses.

In the first model, English vocabulary size was not significant (estimate = .161, odds ratio = .851, SE = .216, z = .744, p = .456), therefore it was removed from the model and the analysis was run again. The refitted model showed a significant effect of time with the scores being higher in the posttest compared to the pretest (estimate = 1.448, odds ratio = 4.254, SE = .081, z = 17.819, p < .001). This confirmed the first research question findings and suggested that the odds of getting a higher score in the posttest were 4.25 times higher than in the pretest. The model also yielded a significant effect of Spanish vocabulary size (estimate = .504, odds ratio = 1.655, SE = .173, z = 2.907, p = .003), indicating that for each unit increase in the Spanish vocabulary size score, the odds of the posttest score increase are about 1.65 times higher (see ).

Figure 3. Graphs showing English (mean score ca. 6.5k/10k) and Spanish vocabulary scores (mean score ca. 12/60).

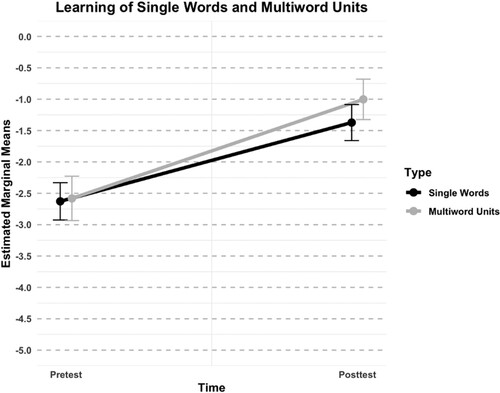

Finally, the type of the target items, that is, single words or MWUs, significantly affected the posttest scores (estimate = .358, odds ratio = 1.430, SE = .167, z = 2.145, p = .031), with the odds of the posttest score being about 1.43 times higher for the MWUs than for the single words (see and ).

Figure 4. Comparison of learning single and MWUs.

Table 5. Single words and MWUs estimated marginal means.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the potential of plurilingual subtitled audiovisual input for language learning, that is, learners engaging with audiovisual input (e.g. videos) with L2 audio and L3 subtitles. While available naturalistically, this type of input has not yet been investigated in research. Therefore, this study contributes to the existing knowledge of learning from videos and goes beyond the traditional view of subtitled audiovisual input by exploring the interconnection between a viewer’s foreign languages.

The first research question targeted the potential for learning from plurilingual audiovisual input. A comparison between the experimental and control groups revealed that participants who watched the TV series with L2 English audio and L3 Spanish subtitles scored significantly higher in the posttest measuring L3 learning, with an odds ratio nearly 10 times larger than those in the control group. This outcome suggests that plurilingual audiovisual input is a promising tool for language learning, particularly in situations where exposure to the target language may be limited (e.g. Muñoz and Cadierno Citation2021). We suggest that this positive intervention result may be attributed to the interaction of two foreign languages in a viewer's mind, promoting multilingual scaffolding (Duarte Citation2020) as proposed by the pedagogical translanguaging theory (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2022). Our international group of participants leveraged their existing L2 English knowledge to make connections with the L3 Spanish on-screen text. Empirically, this aligns with Miralpeix, Gesa, and Suárez (Citation2023), where viewers made form-meaning mappings of target words and expressions after brief video exposure (3 min of repeated viewing) to an unknown language in the subtitles. Our study extends upon this research by examining extensive viewing of twelve episodes without repetitions (262 min). Additionally, our results are in line with Urbanek (Citationin preparation), who demonstrated that participants successfully linked English L2 and Dutch L3 for learning Dutch vocabulary. Our results extend those findings as we show that plurilingual audiovisual input can facilitate learning of not only typologically close languages, but also languages from different language families, such as English and Spanish.

A mediating explanation for the high learning gains in the experimental group is that the participants in our study were regular viewers of English-spoken media with subtitles, as the Netherlands is a subtitling country. Vanderplank (Citation2016) suggests that more experienced viewers tend to be more strategic in how they engage with the image and subtitles, which may have positively influenced the learning gains in our study. Presumably, they were able to attend to the image, audio, and subtitles simultaneously (Ayres and Sweller Citation2012). Subsequent studies could investigate whether this effect can be extended to less experienced subtitle viewers and other viewing contexts, such as learners residing in countries where dubbing is more common. Another interesting avenue for research on plurilingual subtitled audiovisual input would involve investigating its effectiveness for learners still involved in acquiring both languages presented in the input simultaneously. For example, large groups of newcomers in subtitle countries such as the Netherlands might experience this as they are consuming videos with their developing L2 English audio and their host country's L3 target language in the subtitles (Pattemore & Michel, Citationin preparation).

As for the control group, there was a significant decline in posttest scores. This might be attributed to the control group procedure, where participants took the same test twice without an intervention, potentially leading to boredom and decreased motivation during the second test. It is also possible that control group participants initially overestimated their knowledge in the pretest, but when completing the posttest, they may have realised they had not had the opportunity to test their hypotheses about the target items. Therefore, upon seeing the items for the second time, they may have reevaluated their answers. Given the fact that control participants were enrolled in regular Spanish classes in between pre- and posttests, these findings are quite astonishing. Hence, even though they received instruction and engaged with the target language, their scores on the recognition and retention of intervention-related target items underscore the interpretation that in the experimental group, it was indeed the viewing of the TV series that formed the source of vocabulary learning.

The second research question addressed the impact of participants’ English and Spanish vocabulary sizes in the experimental group on learning gains. In addition, it examined whether the type of target vocabulary item, that is, single or MWUs, affected these gains. The results revealed no significant effect of participants’ English vocabulary size on learning gains. This lack of an effect may be attributed to the proficiency of our study's participants, most of whom had an upper-intermediate proficiency level in English () and were accustomed to watching content in English. Although over half of the participants were not Dutch, it is nonetheless also noteworthy that English, given its prominence in Dutch society, is practically a second national language (Edwards Citation2016). It may be, then, that our participants were beyond the proficiency threshold where English proficiency affected learning from plurilingual audiovisual input (e.g. Danan Citation2004). Future research could investigate the influence of plurilingual subtitled audiovisual input on learners with lower proficiency levels in English, or the use of other languages in the audio.

Regarding Spanish vocabulary size, it did significantly contribute to learning the target items, with a higher vocabulary size advantage. This result is consistent with previous research on the effects of prior vocabulary knowledge on learning (see Montero Perez Citation2022), confirming that higher initial vocabulary size is associated with larger gains at the end of the viewing intervention. Thus, while learning can and does happen from this type of input even at the earliest stages of language learning (Miralpeix, Gesa, and Suárez Citation2023), even greater learning can be realised by learners with more proficiency with which to contextualise the new vocabulary. To see a clearer interplay between the two foreign languages, as mentioned above, further studies could explore the effects of proficiency in learning from plurilingual audiovisual input from different perspectives, such as looking at viewers with lower proficiency in both languages, or looking at simultaneous language acquisition of the soundtrack and subtitles languages.

Our study is one of the few that investigated the type of target vocabulary items, that is, we compared single and MWUs, and demonstrated that MWUs had an advantage over single words in the posttest. This aligns with Laufer and Girsai (Citation2008) and Miralpeix, Gesa, and Suárez (Citation2023), who found that the most learned target items were MWUs. Puimège and Peters (Citation2019) suggest that it may be linked to morphological salience of the longer MWUs. Additionally, MWUs may have been presented in a more contextualised manner, incorporating form-meaning-use mappings, which aligns with dynamic usage-based views of language learning (Verspoor Citation2017), and supports previous research on constructions learning from audiovisual research (Pattemore and Muñoz Citation2022). Our findings provide statistical evidence that MWUs were learned better than single words within the same intervention, marking the first study to demonstrate this in audiovisual input research. However, due to the limited work comparing these two types of vocabulary and the relatively small effect observed in our findings, further research is necessary to validate our promising outcome.

This study is not without limitations. First, while it suggests plurilingual audiovisual input is beneficial for vocabulary acquisition, it offers limited opportunities for listening comprehension and speech development as it did not expose learners to the target language's aural input. Investigating simultaneous acquisition of both languages in the plurilingual input could partially address this limitation by potentially promoting speech and listening development in the soundtrack language. Nonetheless, in comparison to L2 captioned input, plurilingual audiovisual input may not be as beneficial for both speech and vocabulary acquisition.

Expanding on the topic of L2 captioned input, this study lacked comparison groups that watched the TV series in Spanish with Spanish captions or L1 subtitles. In our ecologically valid context, practicalities refrained us from doing so, but future research ideally incorporates multiple viewing conditions, as implemented by Urbanek (Citationin preparation).

Next, we did not assess the control group’s Spanish and English vocabulary sizes. However, both experimental and control groups were drawn from the same cohorts consisting of beginner Spanish learners as determined by the start-of-the-year language placement test. Additionally, both groups performed similarly on the pretest. Regarding English proficiency, all participants were admitted to an English-medium programmes that require upper-intermediate English levels (minimally B2), indicating comparable fluency levels.

In addition, we chose to use content-specific frequency (i.e. the number of times a target item appeared in the tv show) to select our target items rather than external frequency (e.g. based on a reference corpus). Since the participants were beginner learners and earlier work has shown that internal and external frequency strongly correlate (Pattemore and Muñoz Citation2020), we think that external frequency might play a lesser role. Still, future studies could take both into account to evaluate whether this impacts the findings.

Lastly, our viewing intervention was implemented as homework; therefore, we could not fully control the viewing process. While this might be viewed as a methodological limitation, it can also be seen as a strength, as our intervention replicated natural viewing behaviour – in the comfort of one's home rather than a university classroom or lab. Additionally, the use of the EdPuzzle platform (as mentioned above) allowed us to remotely monitor the viewing process.

Conclusion

This study introduced and explored the potential of plurilingual subtitled audiovisual input for language learning, contributing to and extending the existing knowledge in audiovisual input research. The study revealed that plurilingual audiovisual input offers promise for vocabulary learning, particularly in contexts with limited exposure to the target language.

Pedagogically, educators may consider incorporating plurilingual audiovisual input from the very first stages of instruction and learning, emphasising the value of multilingual approaches to language learning to their students. Additionally, the findings encourage the focus on MWUs and contextualised learning materials to boost vocabulary acquisition. Overall, this is another study supporting the benefits of exposure to audiovisual input and subtitling for language learning, even where neither language involved is an L1s.

Ethics and consent

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of Groningen Faculty of Arts Research Ethics Review Committee [ID 86584019] prior to the start of data collection. Participants’ written informed consents were obtained before the start of the study. Although viewing was integrated into the course curriculum and students received 10% of the grade for it, students had the option to abstain from participating in the testing and have their data removed from the research project. Some students exercised this option without any negative impact on their grades.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anastasia Pattemore

Anastasia Pattemore, PhD, is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the University of Groningen (The Netherlands). Her research focuses on uncovering optimal language learning conditions from audiovisual input both inside and outside the classroom. This includes investigating the role of different types of subtitling, textual enhancement, processing, viewing time distribution, and cognitive individual differences.

Beatriz Cabrera Fernández

Beatriz Cabrera Fernández, M.A., is lecturer of Spanish as a Foreign Language (SFL) and coordinator at the University of Groningen (The Netherlands). Her fields of interest are language assessment, internship supervision of SFL pre-service teachers and the design and implementation of virtual exchanges between language learners and SFL pre-service teachers.

Marilyn Lopez de Artola

Marilyn Lopez de Artola, M.S., is a lecturer of Spanish at the International Business department of NHL Stenden. Her fields of interest are internationalisation, interdisciplinary projects, multiculturalism and positive emotions in the foreign language classroom with focus on fostering a safe learning environment, and the use of humour as a teaching strategy.

Marije Michel

Marije Michel, PhD, is a professor of Language Learning at the University of Groningen (The Netherlands). Her research focuses on cognitive and social aspects of second language (L2) learning and instruction with specific interest in task-based language teaching (TBLT), L2 writing processes, and alignment in digitally mediated communication. Recently, she guest-edited special issues on Alignment in SLA and Linguistic Complexity. Marije is a board member of the European Second Language Association (EuroSLA) and the International Association of TBLT (IATBLT).

Notes

1 Although we refer to an additional language as L3 throughout this study, we acknowledge that a learner’s additional foreign language might not be their third language, but rather fourth, fifth, etc., as there can be a great variation in viewers’ linguistic backgrounds.

References

- Ayres, P., and J. Sweller. 2005. “The Split-Attention Principle in Multimedia Learning.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning, edited by R. Mayer, 135–146. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511816819.009.

- Bird, S., E. Loper, and E. Klein. 2009. Natural Language Processing with Python. Sebastopol: ’Reilly Media Inc.

- Bisson, M., W. Van Heuven, K. Conklin, and R. Tunney. 2014. “Processing of Native and Foreign Language Subtitles in Films: An Eye Tracking Study.” Applied Psycholinguistics 35 (2): 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716412000434.

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2022. Pedagogical Translanguaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009029384.

- Christensen, R. H. B. 2022. Ordinal – Regression Models for Ordinal Data. R Package Version 2022.11–16. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ordinal.

- Danan, M. 2004. “Captioning and Subtitling: Undervalued Language Learning Strategies.” Meta 49: 67–77. https://doi.org/10.7202/009021ar.

- Danan, M. 2015. “Subtitling as a Language Learning Tool: Past Findings, Current Applications, and Future Paths.” In Subtitles and Language Learning: Principles, Strategies and Practical Experiences, edited by Y. Gambier, A. Caimi, and C. Mariotti, 41–62. Lausanne: Peter Lang.

- Duarte, J. 2020. “Translanguaging in the Context of Mainstream Multilingual Education.” International Journal of Multilingualism 17 (2): 232–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.1512607.

- d’Ydewalle, G., and W. De Bruycker. 2017. “Eye Movements of Children and Adults While Reading Television Subtitles.” European Psychologist 12 (3): 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.12.3.196.

- Edwards, A. 2016. English in the Netherlands: Functions, Forms and Attitudes. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/veaw.g56.

- Field, A. 2018. Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics. 5th ed. London: SAGE.

- Follows, S. 2018. “Which Languages Are Most Commonly Used in Movies?” Stephen Follows Film Data and Education. https://stephenfollows.com/.

- Gesa, F., and I. Miralpeix. 2022. “Effects of Watching Subtitled TV Series on Foreign Language Vocabulary Learning: Does Learners’ Proficiency Level Matter?” In Foreign Language Learning in the Digital Age, edited by C. Lütge, 159–173. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003032083-14.

- Izura, C., F. Cuetos, and M. Brysbaert. 2014. “Lextale-Esp: A Test to Rapidly and Efficiently Assess the Spanish Vocabulary Size.” Psicologica 35: 49–66.

- Laufer, B., and N. Girsai. 2008. “Form-focused Instruction in Second Language Vocabulary Learning: A Case for Contrastive Analysis and Translation.” Applied Linguistics 29 (4): 694–716. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amn018.

- Lenth, R. V., B. Bolker, P. Buerkner, I. Giné-Vázquez, M. Herve, M. Jung, J. Love, F. Miguez, H. Riebl, and H. Singmann. 2023. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means. R Package Version 1.8.8. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans.

- Meara, P. M., and I. Miralpeix. 2017. Tools for Researching Vocabulary. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783096473

- Miralpeix, I., F. Gesa, and M. Suárez. 2023. “Vocabulary Learning from Subtitled Input After Minimal Exposure.” In Vocabulary Learning in the Wild, edited by B. L. Reynolds, 263–283. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1490-6_10.

- Miralpeix, I., and C. Muñoz. 2018. “Receptive Vocabulary Size and Its Relationship to EFL Skills.” IRAL – International Review of Applied Linguistics and Language Teaching 56 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2017-0016

- Montero Perez, M. 2022. “Second or Foreign Language Learning Through Watching Audio-Visual Input and the Role of on-Screen Text.” Language Teaching 55 (2): 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444821000501.

- Muñoz, C. 2024. “Audio–Visual Input and Language Learning.” In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, edited by C. A. Chapelle. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal20436

- Muñoz, C., and T. Cadierno. 2021. “How Do Differences in Exposure Affect English Language Learning? A Comparison of Teenagers in Two Learning Environments.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 11 (2): 185–212. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.2.2.

- Pattemore, A., and M. Michel. in preparation. A potential of plurilingual audiovisual input for simultaneous language learning.

- Pattemore, A., and C. Muñoz. 2020. “Learning L2 Constructions From Captioned Audio-Visual Exposure: The Effect of Learner-Related Factors.” System 93: 102303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102303.

- Pattemore, A., and C. Muñoz. 2022. “Captions and Learnability Factors in Learning Grammar From Audio-Visual Input.” The JALT CALL Journal 18 (1): 83–109. https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v18n1.564.

- Pellicer-Sánchez, A. 2019. “Learning Single Words vs. Multiword Items.” In The Routledge Handbook of Vocabulary Studies, edited by S. Webb, 158–173. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429291586-11.

- Puimège, E., and E. Peters. 2019. “Learning L2 Vocabulary from Audiovisual Input: An Exploratory Study Into Incidental Learning of Single Words and Formulaic Sequences.” The Language Learning Journal 47 (4): 424–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2019.1638630.

- Sabrià, Q. 2013. “Edpuzzle.” https://edpuzzle.com/.

- Schur, M. 2016. The Good Place. [TV series]. United States: Fremulon.

- Taylor, J. E., G. A. Rousselet, C. Scheepers, and S. C. Sereno. 2023. “Rating Norms Should Be Calculated From Cumulative Link Mixed Effects Models.” Behaviour Research Methods 55: 2175–2196. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01814-7.

- Urbanek, L. in preparation. “The Effects of Different Subtitling Modes on Vocabulary Acquisition and Content Comprehension among Learners of L3 Dutch in German Schools.” Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Münster.

- Vanderplank, R. 2016. Captioned Media in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching: Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard-of-hearing as Tools for Language Learning. Oxford: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50045-8.

- Verspoor, M. 2017. “Complex Dynamic Systems Theory and L2 Pedagogy: Lessons to Be Learned.” In Complexity Theory and Language Development, edited by L. Ortega and Z. Han, 143–162. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.48.

- Webb, S., and M. P. H. Rodgers. 2009. “Vocabulary Demands of Television Programs.” Language Learning 59 (2): 335–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2009.00509.x.

- Wesche, M., and T. S. Paribakht. 1996. “Assessing Second Language Vocabulary Knowledge: Depth vs Breadth.” The Canadian Modern Language Review 53 (1): 13–40. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.53.1.13.

- Wickham, H. 2016. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer Link. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4.