ABSTRACT

Purpose

This scoping review investigates research on Military English (ME) language and teaching over the past three decades. Despite the growing need for English proficiency among military personnel due to increases in international joint operations [Niculescu, B.-O., G. Obilişteanu, and I. A. Dragomir. 2019. “Contribution of Foreign Languages to Building the Professional Career of the Land Forces Academy Cadets.” Land Forces Academy Review 24 (3): 213–219], ME as a field of study lacks comprehensive research. The features and patterns of ME and effective approaches towards ME language instruction remain insufficiently explored.

Methodology

The study employs a scoping review approach [Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32] to map the current state of ME research, including language features, themes, and pedagogical approaches. The study initially identified 1778 articles across major databases. This initial data set was then examined and narrowed down to 34 articles based on the inclusion criteria.

Findings and Originality

The findings indicate a diverse range of research themes and learner background within ME education, including motivation, needs analysis, and the description of Military English itself. The research also highlights the distinct domain of ME and the necessity of efficient, relevant, and tailored language instruction to meet the practical ME needs of learners. It also points out the limited number of studies that adequately evaluate the effectiveness of various teaching approaches. The study emphasizes the importance of alignment among the various stakeholders and calls for more rigorous research in the field.

1. Introduction

Military English (ME) is increasingly in demand among military personnel for interoperability purposes (Juhl Kristensen and Kildevang Citation2019; Wolf Citation2017). The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) defines interoperability as ‘the ability to act together coherently, effectively and efficiently to achieve Allied tactical, operational and strategic objectives’ (NATO Term Citation2024). To achieve this, equipment, procedures, and communication require alignment between nations and personnel. Specifically, the current article focuses on the aspect of communication in English of military personnel as they strive to effectively engage in joint training and education (Monaghan Citation2012; Szvircsev Tresch and Picciano Citation2007).

English has become the lingua franca within the military context (Niculescu, Obilişteanu, and Dragomir Citation2019), making proficiency in English crucial for engaging in international military operations (Keagle and Petros Citation2010; Monaghan Citation2012). Consequently, military personnel must be able to communicate effectively in English with individuals from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, particularly in high-stakes situations. There is increasing focus on tailoring English language education to the specific contexts in which cadets and officers will operate, seeking more effective methods and to seek more efficient methods for instruction and assessment of ME (Di Biase and Gratton Citation2015; Jones and Askew Citation2014).

The specialized field of ME language teaching, however, operates under various models: it is sometimes integrated implicitly within standard military training conducted in English for L1 users; within alliances like NATO, which have specific proficiency requirements for courses; or as a separate component from military content courses, with a distinct emphasis on English proficiency (e.g. BILC Citation2024b; NATO Citation2023; University of the Bundeswehr Munich Citationn.d.). This diverse approach reflects the complex nature of English language education in the military, acknowledging the critical role of language proficiency in ensuring effective international cooperation and mission success.

However, empirical studies on ME or ME education are limited. How does research describe the features of ME, and how is it taught to the second language (L2) users of English? How can current practices of ME education at military academies be improved to facilitate interoperability? These are some of the questions that the current scoping review addresses. The primary objective is to map findings regarding the learning, teaching, testing, and use of ME within English as a foreign language (EFL) context in the last 30 years. We seek to systematically address the outcomes of the research, including effective approaches to teaching, learning, and testing, and to establish the gaps for further research and classroom instruction.

2. Military English and military language education

Military English (ME) is defined here as a genre-specific form of the English language, tailored to meet the communication needs of military personnel. This includes technical terms, acronyms, jargon, slang, and discourse patterns specific to the different domains of the military organization and operations (Monaghan Citation2012). ME terminology is often so specific that most terms are not found in major corpora of English (Wolf Citation2017). Therefore, ME can be considered a type of English for Specific Purposes (ESP) where English language teaching is closely based on the learners’ needs (Hutchinson and Waters Citation1987). Aside from being a genre with subject-specific terms and concepts, Wolf (Citation2017) argues that ME is ‘the language of multinational, multicultural and multilingual communities of practice’ (685). In other words, military personnel need cultural and linguistic education as well as adaptive capabilities to navigate the dynamic English language use context.

Historically, military language teaching has played a pioneering role in the development of innovative language teaching approaches. It introduced audio-lingual approaches in the 1950s (McCormick Citation1970) and incorporated e-learning and virtual learning spaces from the 1990s (e.g. Kaplan et al. Citation1998). Moreover, the US and Canada predominantly led the way in innovations in language teaching, focusing on teaching languages other than English to American and Canadian forces (e.g. DLIFLC Citation2023). In recent decades, however, the landscape of language education in the military context is shifting. Within the past three decades, countries in the former Eastern Bloc have sought membership in the EU and NATO (Monaghan Citation2012). Consequently, NATO requires affiliated countries to undergo English language education and expect their military personnel to hold a sufficient level of English language proficiency interoperability (Keagle and Petros Citation2010). However, the approach to ME education and the English language proficiency levels of the cadets and officers seem to vary among countries.

As will be demonstrated through this study, despite the critical role of English in military operations, most current research in English language teaching methodology focuses on general English proficiency or academic English. Only a handful of studies examine specific teaching approaches in military academies for ME preparation. Moreover, ME is exclusively taught to L2 users of English and traditionally with the intent to strive towards L1 norms. L1 users of English have no specific ME education or proficiency requirements, with terminologies often being taught implicitly through content courses. This disparity in structured ME education between L1 and L2 users of English may have potential consequences of misunderstandings during joint military operations (Crossey Citation2005; Poteet et al. Citation2008).

3. NATO, BILC and STANAG 6001

To overcome potential miscommunications, NATO has emphasized the importance of standardized language profiles to ensure effective communication among NATO members and partners, and to ensure military personnel have sufficient language proficiencies for their appointments (Green and Wall Citation2005). NATO has worked towards improving English language teaching in the alliance nations and standardizing English language proficiency measurements to enhance interoperability even with Partnership for Peace nations. Some of the efforts by NATO include the establishment of BILC and STANAG.

BILC, or the Bureau for International Language Coordination, is responsible for coordinating language training and education efforts among NATO members (BILC Citation2024a). BILC provides training opportunities for military personnel and develops language training materials and assessment instruments. BILC has worked towards sharing best practices in language education, testing and training among its members and in advising NATO on ways and means of standardizing language practices to improve effectiveness and efficiency in operations and staffing (Green and Wall Citation2005; Monaghan Citation2012). Moreover, BILC has established a set of common terms endorsed by NATO member countries. These terms are published on the NATO Term website, specifically for the most updated definitions and abbreviations of terms (NATO Term Citation2024).

Another way that NATO addressed the issue of language standards is through STANAG, or the NATO Standardization Agreement 6001 (BILC Citation2024b). It provides a framework for the assessment of language proficiency in listening, speaking, reading, and writing. It has six proficiency levels: Level 0 (No proficiency) to Level 5 (Highly-articulate native). These levels are used to identify language training and assessment requirements for troop-contributing nations for NATO operations and for staffing international headquarters. STANAG norms are designed to ensure that military personnel possess the necessary language skills to effectively communicate in multinational and operational environments (Green and Wall Citation2005; Monaghan Citation2012). However, STANAG does not dictate the content of the tests themselves, and language testing in the military varies between nations and institutions. Research suggests that more detailed language descriptors are necessary to produce tasks and tests that accurately reflect the target language needs and proficiency (Di Biase and Gratton Citation2015; Green and Wall Citation2005).

Despite the aforementioned efforts, Monaghan (Citation2012) argues that NATO faces challenges in achieving language standards and interoperability. One of the main challenges is the increasing number of multinational operations, which creates complexity surrounding coordination of tasks and coherence in communication (Juhl Kristensen and Kildevang Citation2019). The language barrier can pose a significant threat and, when miscommunication occurs, it can even lead to loss of life (Di Biase and Gratton Citation2015). Furthermore, reports on policies such as the above often fall short of capturing actual classroom practices, the voices of teachers and students of ME courses, and the practicalities of STANAG testing. What is more, in spite of an increase in joint operations and ever-evolving security concerns, Monaghan’s (Citation2012) report is the most recent summative report on ME education among NATO countries, which is more than a decade old. What do we know about actual ME classrooms in terms of the language taught and the methodological approaches employed?

The primary objective of this study is to survey the current findings regarding instruction of ME in the last 30 years. By taking a systematic approach, it seeks to address research outcomes and areas that warrant further investigation. Consequently, the current study investigates the following five key questions:

Who are the primary participants targeted in ME research?

What research methodologies are being utilized?

What themes are investigated within the field of ME language research?

How is ME defined or characterized in the research?

How are the characteristics of ME language education described in terms of its pedagogical approaches and learning environments?

4. Method

4.1. Rationale for a scoping review

The current study employs a scoping review approach ‘which summarizes substantive and methodological features of primary studies on a particular topic’ (Chong and Reinders Citation2022, 3). This systematic approach to secondary research aims to ‘map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available … . especially where an area is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively before’ (Mays, Roberts, and Popay Citation2001, 194; emphasis in original). Scoping reviews are capable of examining ‘the extent, range, and nature of research activity’ and ‘identify research gaps in the existing literature’ (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005, 21). Further, a scoping review is an appropriate method for research areas in which topics may be studied using multiple different research methods, including both quantitative and qualitative (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). Munn et al. (Citation2018, 2) list the following five points that scoping reviews can achieve:

To identify the types of available evidence in a given field

To clarify key concepts/ definitions in the literature

To examine how research is conducted on a certain topic or field

To identify key characteristics or factors related to a concept as a precursor to a systematic review

To identify and analyze knowledge gaps.

As a scoping review, this study aims to reveal the extent and nature of research published in article form on ME language learning and teaching methods, use, and testing, and the knowledge gaps in the field. To conduct the scoping review, we used Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) five-step process: (1) identify research questions (see Section 2.2), (2) identify relevant studies; (3) select studies using inclusion and exclusion criteria; (4) organize the data according to themes; (5) collate, summarize, and report the results. Stages 2-5 are explained in the following sections. We conducted a broad and inclusive search to ensure breadth and inclusivity, before narrowing the studies based on the inclusion criteria.

4.2. Database

An extensive search across major databases relevant to the area of study was conducted, including EBSCO host, MLA International Bibliography, Education Source, ERIC, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, Teacher Reference Center, eBook collection, ProQuest’s Military Database, and Web of Science. Thereafter, searches on the Swedish Defense University’s library search and the Swedish university register (DiVA) were conducted to ensure articles relevant to our local needs (i.e. Sweden) were included. To ensure the quality of the publications (e.g. peer reviewed) and the replicability of the study, backwards referencing, snowball sampling, and hand searching were not conducted.

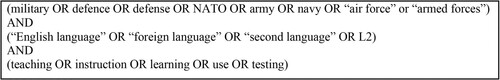

4.3. Search terms and range

A search term thread as shown in was developed in consultation with a university librarian to ensure accuracy and relevance of the search thread. We made sure to cast a wide net in terms of including different military branches, organizations (i.e. NATO, BILC), and countries, while attempting to exclude irrelevant studies that only appeared due to the association between ‘Phd’ and ‘defense.’ We also filtered the search results in terms of ‘peer-reviewed’ articles, in order to exclude news articles and conference presentations. The year of publication ranged between the years 1993-2023. The end-date was chosen in order to include the most recent year when the current study was conducted, 2023. The start date, in turn, was selected in order to capture a potential research surge as a response to the establishments of the NATO-led Partnership for Peace in 1994 (NATO Citation1994). Partnership for Peace emphasizes cooperation, transparency, and interoperability among NATO affiliated nations, making English language education a ‘high priority’ (Keagle and Petros Citation2010, 59).

4.4. Inclusion criteria

To be included in the scoping review, the publication has to satisfy the following criteria:

It must involve an empirical design (i.e. a study with clear research design and empirical evidence whether quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods).

It must be informed by a linguistic or pedagogical theory or framework.

It must be relevant to learning, teaching, testing, or using English as a foreign or second language in the military context. Studies on non-English language, English as a first language (L1) for current or former military personnel, or studies that examine the impact on the L1 were excluded.

It must be written in English.

It must be peer-reviewed.

These criteria were selected to ensure the research questions can be sufficiently answered. A number of papers claiming to be peer-reviewed were excluded because they lacked a description of a reliable research methodology. Several studies were excluded due to the paper not having an empirical research design and simply proposing or discussing possible teaching methods without conducting any research to confirm their outcomes. Some studies were excluded due to the quality of the writing interfering with comprehension and key ideas and results were unverifiable. We will return to this point in the discussion. In short, exclusions were made on the basis of the inclusion criteria and insufficient academic and methodological vigor.

4.5. Screening process

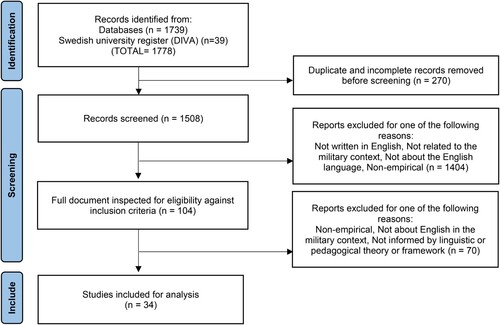

The database search was conducted over June 21-22, 2023, by two research members using the same search thread across all databases. A third researcher then conducted the database search independently using the same search thread and confirmed consistency. The search yielded 1778 hits from the combined databases. Data from the database hits were extrapolated into an Excel file. After manually removing duplicates, 1508 publications remained and were screened using the inclusion criteria.

The screening process comprised three stages. First, in order to ensure consistency and reliability, the first 100 articles were examined individually and then compared between the two researchers. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached for all instances, and the inclusion criteria was reconfirmed between the two researchers.

Next, the remaining publications were divided between the two researchers who then manually examined it against the inclusion criteria. If any ambiguous cases arose during this process, abstracts were read and discussed by the two researchers, reaching an agreement each time. Therefore, no calculation of reliability was conducted. Despite the carefully crafted search term thread, the majority of articles excluded in the first screening phase were related to ‘doctoral defense/defence.’ Moreover, several articles were excluded for multiple reasons, such as being unrelated to the military context and being a non-empirical study. Therefore, the number of excluded articles in the flow chart () are combined.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow chart illustrating the process of database search.

Finally, the remaining 104 articles were divided between the three researchers, who then thoroughly read and reviewed the articles. Reasons for the inclusion or exclusion of each article were then presented and discussed. In cases of uncertainty, all researchers read the article and discussed its inclusion or exclusion based on the criteria. Consensus was reached at all times. Again, multiple articles were excluded for more than one reason, and therefore the number of excluded articles are combined in the flow chart (). A total of 34 articles were included in the detailed analysis, which was conducted by all three researchers. The search and screening process is displayed in .

4.6. Coding scheme

As the process of mapping the research and identifying themes, the articles were coded systematically on features relevant to empirical studies. The coding scheme is displayed in .

Table 1. Coding scheme.

5. Results

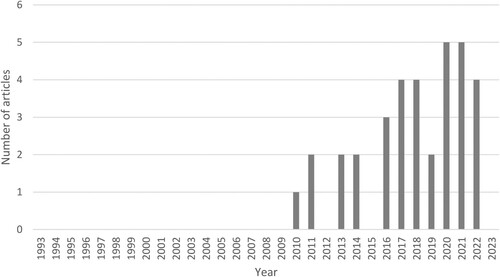

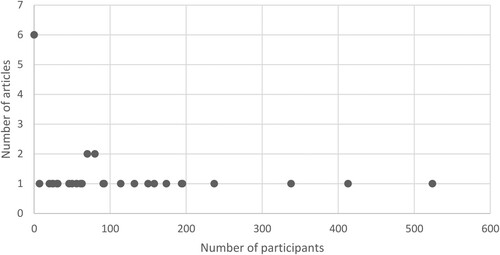

The results are presented in two steps. The first section aims to answer Research Questions 1-3, and presents an overview of the publications including chronological frequency (), participant sample sizes (), research approach (), division of publications by branches of service (), participants’ L1 (), and research topics (). The second step aims to answer Research Questions 4-5, and includes a synthesis of the individual research topics identified, including the characteristics of ME, pedagogical approaches, and learning environments.

Figure 3. Chronological frequency of publications.

Figure 4. Number of participants per study.

Table 2. Research approach.

Table 3. Branches of Service.

Table 4. Participants’ L1.

Table 5. Overview of researched topics.

5.1. Characteristics of the studies

As illustrated in , although the current study utilized a search range beginning in 1993, there were no publications included in the final analysis until 2010. A more significant surge in publications was observed in the most recent years, particularly between 2020 and 2022. This suggests the lack of interest in ME teaching and learning as a research agenda in the 1990s and early 2000s. It may also imply the lack of research published in English with academic rigor on this subject. In contrast, the data suggests the growing interest in the topic as a research area, and possibly reflecting the need of a systematic approach for ME education.

illustrates the sample size of the studies and their frequency. There is a large disparity in terms of sample sizes. Some studies had no participants, especially the articles on language policy and articles using a corpus linguistic approach. In contrast, the study by Nenko, Yaryhina, and Vorona (Citation2021) had the highest number of participants with 524. On average, studies had 125 participants.

illustrates the research approach employed in each of the articles. As shown above, the most frequent approach was a mixed-methods approach using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Qualitative and quantitative approaches were used equally often.

provides an overview of the branch of service the research with which participants were affiliated. The category ‘multiple’ was selected when members of multiple branches of service were included, while ‘unspecified’ was selected if the article did not specify which branch of service the participants were affiliated with or if the study used a corpus. As demonstrated in the table, the majority of the studies are not specifically affiliated to a certain branch of service. Nine out of 34 studies did not specify a certain branch of service, and eight studies were conducted with military personnel from multiple branches. This finding prompts the question whether more research should be conducted with a specific branch of service in mind to have a more targeted instruction of ME that addresses the specific needs of each branch of service.

Next, demonstrates the L1 of the participants of the individual studies. In cases where studies included participants from multiple L1 backgrounds, each language was counted separately. However, the study by Solak (Citation2014) included 14 different L1s, which were then categorized under ‘multiple.’ Five studies either employed a corpus or analyzed steering documents, and were therefore categorized as ‘none.’ The table shows a diverse inclusion of L1 speakers, predominantly from European languages. There is also a relatively high frequency of Arabic and Ukrainian L1 speakers, suggesting a growing interest and necessity for military personnel speaking these two languages to acquire ME.

Finally, the contents of the articles are examined based on theme. Seven broad research topics were identified among the 34 articles as presented in . Notably, the themes with the most results include research about teaching and learning practices, as well as student motivation and perceived needs for learning ME. The synthesized findings from each of these identified research topics are displayed in the following section.

5.2. Researched topics

Below we present a content analysis of the identified research topics in the area of ME and ME education. The themes listed in represent the main focus of the articles, thus each article was counted only once. However, we recognize that some articles include multiple themes, which is why some articles appear twice in the thematically organized content analysis below.

5.2.1. Teaching and learning military English

One of the most frequent themes identified among the articles was the topic of teaching and learning of ME, with eight articles. The studies demonstrate that ME language programs in the English as a second language (ESL) or EFL in military settings utilize a range of approaches, including Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and Task-based Language Teaching (TBLT) (Richards and Rodgers Citation2014), along with ME terminology instruction, the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools, and learning strategies.

Research highlights CLIL and TBLT as promising approaches for enhancing learners’ lexical knowledge and proficiency in the military contexts. Studies by Finardi et al. (Citation2016) and Nilsson and Lundqvist (Citation2022) demonstrate that CLIL can facilitate multifaceted skill development, both productive and receptive, by engaging officers in content and tasks that reveal knowledge gaps, thereby motivating them to improve. However, they also indicate challenges regarding collaboration between content teachers and language teachers, and a need for more quantitative research on the efficacy of CLIL in improving ME proficiency. In contrast, TBLT research indicates that tiered tasks and heterogeneous groupings can enhance motivation and learning outcomes (Hung and Chao Citation2021; Park Citation2016). Meanwhile, the effectiveness of both teaching approaches seem to vary based on learners’ proficiency levels, the content of the task, and level of difficulty. Park (Citation2016) also indicates the need to create safe learning environments where learners can engage in tasks without fear of ‘losing face,’ providing some insights into the dynamics of the learning environment of the military setting.

In contrast, a terminology focused approach shows a clear appreciation from the learners. Bogusz (Citation2017) explores the effectiveness of utilizing classroom-based learning and hands-on exercises for learning basic ME terminology. Respondents reported significant improvements in their linguistic skills, not only in specialized military terminology but also in general areas such as grammar and syntax.

The use of ICT tools in military education seems to continue to be an area of interest for investigation. Fuentes-Luque and Campbell (Citation2020) and Sovhar (Citation2021) suggest that ICT can enhance listening performance, communicative competence, and engagement with ME. Cadets and officers also showed a preference for authentic and tailored learning materials accessible via mobile and computerized tools. However, these studies do not employ an experiential design in their research, lacking evidence in actual effectiveness in ME language learning.

Finally, Solak (Citation2014) studies learning strategies among military professionals and suggests a varied reliance on different learning strategies across L1 backgrounds. The findings revealed that while L1 users of English do utilize learning strategies, they are not significantly better at employing these strategies in every aspect compared to L2 users.

The programs vary in terms of length, frequency, and content, with some focusing on basic language skills and others on specific military-related topics. The majority of studies report positive outcomes in terms of language proficiency, communication skills, and cultural awareness among military personnel. These studies highlight the importance of both effective teaching approaches and learning efforts in order for successful language learning outcomes to be achieved.

5.2.2. Motivation

The study of motivation among students was also one of the most researched areas of ME teaching, with eight out of the 34 articles focusing on this topic. A few studies investigated motivation in correlation with another dependent variable, such as vocabulary knowledge (Alqahtani Citation2020) and the degree of learner autonomy (Abd Rahman et al. Citation2022). It is also important to note that some studies within this subset may reflect opportunities for improvement in research practices, even though they met the strict inclusion criteria of the current study. For instance, the instruments used to measure ‘motivation’ were not clear, and/or the statistical analysis was not robust enough to draw any decisive conclusions from their results.

Nevertheless, findings from several studies suggest that motivation is indeed connected to the willingness to learn English (Alqahtani Citation2017, Citation2018; Kurum Citation2011), and that the quality of classroom teaching affects student motivation (Grafeeva Citation2020; Jodaei et al. Citation2018). Farr (Citation2016) notes that Swedish officers have high motivation to learn. However, due to their busy schedules, they do not show interest in devoting time into English language learning, and if the English classes do not offer what they need, their motivation will decrease. This suggests the need for having efficient English language lessons that target officers’ needs.

5.2.3. Needs analysis

Seven out of the 34 articles focused on needs analysis. As discussed above, ME lessons need to be efficient and tailored to specific needs to sustain student motivation. Therefore, having a clear understanding of learners’ needs is critical when organizing teaching for ME purposes. The level of specificity of the needs analysis, however, varied. For example, Synytsya and Keremidchieva (Citation2011) identified specific vocabulary needed by their military medical students to perform their duties, and Maiier and Yukhymenko (Citation2022) found that the most common communication situation in English is during information briefings and special operations. In contrast, other studies were limited to seeking students’ overall perspective of importance towards English (Orna-Montesinos Citation2013), indicating gaps between student needs and actual practice (Alshabeb, Alsubaie, and Albasheer Citation2017; Alshehab Citation2014; Nenko, Yaryhina, and Vorona Citation2021) and identifying gaps between teacher and student perceptions of learning needs (Nejković and Bošnjak Citation2020). These latter findings mirror those from the ‘motivation’ subset of studies, indicating a consistent theme. That is, there appears to be a discrepancy between the ME education provided to military personnel and their actual needs, resulting in a hindrance to both motivation and English language learning.

5.2.4. Describing military English

As mentioned in the background section, ME can be characterized as the combination of general proficiency as outlined by STANAG and specific terminology and phraseology detailed within each branch of service or task (NATO Term Citation2024). This was consistent with the findings from the empirical studies identified for the scoping review. For instance, Park (Citation2020) refers to the importance of general English knowledge along with phraseology for radiotelephony communications, and Synytsya and Keremidchieva (Citation2011) discuss their students’ need to master medical terminology. These publications suggest the vast variation of terminology used in the field, which in turn needs to be identified and pre-taught if an L2 speaking officer is to execute tasks in English.

While none of the articles identified during this project went in depth to display a list of terminology of their institutions or tasks, four of the 34 articles used a corpus linguistics approach to examine the patterns of ME (Chen, Chang, and Yang Citation2021; Lahodynskyi, Mamchur, and Skab Citation2018; Noguera-Díaz and Pérez-Paredes Citation2019; Velikova Citation2019). These four studies collectively suggest that military language is predominantly characterized by its long noun phrases. These long noun phrases often consist of multiple nouns that convey complex and specific meanings. According to Noguera-Díaz and Pérez-Paredes (Citation2019), ME noun phrases can sometimes have up to five nouns, where they undergo extensive pre- and post-modification. In contrast to the complexity of structure and specificity of meaning indicated by Chen, Chang, and Yang (Citation2021), Noguera-Díaz and Pérez-Paredes (Citation2019) found that the syntax tended to be simple. Along the same lines, Lahodynskyi, Mamchur, and Skab (Citation2018) and Velikova (Citation2019) found terminology in intelligence and the Navy to include frequent use of shortened noun phrases through the use of abbreviations, acronyms, clippings, and blends. The studies on the features of ME from the corpus studies suggest that military personnel will most likely have issues with these linguistic characteristics and would benefit from giving special attention to these.

5.2.5. Testing

Three articles focused on testing, a central issue in determining the language competence of military personnel and deciding whether they can join an international operation. Two articles focus on piloting alternative ways of conducting STANAG tests (Gawliczek et al. Citation2021; Grande, Leishman, and Skilleås Citation2022) and one discusses the construction of proficiency tests in aviation English (Park Citation2020).

Traditionally, professional testers conduct STANAG tests in person. However, Gawliczek et al. (Citation2021) discuss their pilot study on computer adaptive language testing (CALT) as an alternative to in-person tests, highlighting advantages such as objective assessment and test security. The results of the study show that CALT measures test-takers’ abilities better than traditional pen-and-paper options, and significantly reduced the test length. A weakness in the study is the lack of discussion around the limitations of CALT, as it only tests receptive language skills (reading and listening). Grande, Leishman, and Skilleås (Citation2022) respond to students’ qualms about the nature of the STANAG test being focused on ‘general English’ by conducting a pilot study where the test was infused with ‘military flavor.’ The test thus blended military content domains with the more general linguistic functions associated with an oral proficiency interview. The authors found that although adding a military aspect made the test seem more relevant to the test-takers, it had minimal impact on the actual English language performance of those taking the test. Finally,Park’s (Citation2020) study focuses on how to improve the accuracy of military aviation English testing. Departing from empirical data collected from air traffic controllers, Park shows how test accuracy and authenticity can be greatly improved using target tasks, preferably in sequence.

These studies present the adaptations that ME practitioners are incorporating into their operational practices, either by adapting the STANAG test or by introducing tests that would more accurately measure learners’ English language proficiency levels. At the same time, the studies suggest potential issues with the STANAG test in terms of its content and procedures that may not meet learners’ needs and issues of conducting the test within the limited time available to military personnel.

5.2.6. Military English language policy

Only three out of the 34 studies focused on language policy in the armed forces. Their common aim was to investigate policy phenomena in multilingual contexts; Berthele and Wittlin (Citation2013) describe issues connected to multilingualism in the Swiss Army, while de Fourestier (Citation2010) takes a wider perspective on language policy in a number of multilingual countries, to then narrow his focus to English-French language policy in the Canadian armed forces. Last, Orna-Montesinos (Citation2018a) discusses the implications of English as a working language in international military contexts, claiming that the dominance of English places those who speak another language – in this case Spanish – at a disadvantage. What unites these articles is the authors’ interest in minority language speakers’ perceptions of when and in which contexts minority languages may be spoken, and strategies for communicating in English in the military context. All three articles are particularly strong when highlighting the relationships between official policy, practical interactions, and the experience of the individual. The issues presented in these articles are linked to questions of English language teaching and STANAG testing, but instead of focusing solely on the necessity and levels of proficiency of English, they consider individual’s experiences and perceptions of obstacles to communication.

5.2.7. Military English use environment

Military Language use environment, while broad and lending itself to many research fields, only included one article. Nakashima, Abel, and Smith (Citation2018) studied how vehicle sound impacted the listening comprehension of L1 and L2 users of English using headsets to communicate in pairs with and without visual barriers. The results show that even highly proficient L2 users may not hear as accurately as their L1 peers both on the radio and face-to-face. Finally, accents of L2 speakers affected how well the participants understood the speech being communicated. This study highlights the unique setting in which ME is used during actual operations (i.e. noise), and suggests the need for more studies that examine ME use in the actual environment in which it will be used.

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of the main findings

The current scoping review set out to investigate the nature of ME language and teaching, methodological approaches to ME research, the characteristics of research participants, research themes, and publication frequency over time. The results reveal that a wide variety of topics are of relevance to the research area of ME and ME education. A central idea, and what broadly unites the topics discussed above, is the importance of relevant and up-to-date needs analyses that function as a basis for the improvement and innovation in ME language teaching and testing. Therefore, ME does indeed exhibit features of ESP (Hutchinson and Waters Citation1987), but effectively, ME is merely a broad classification that includes the highly specialized language and language use conditions of the military.

Studies note that learners of ME have diverse backgrounds and needs, which vary across the different specializations such as medical, IT, engineering, intelligence, Navy, Air Force, and Army in terms of terminology and communication skills. In addition, learners presented a wide range of L1 backgrounds, making it vital for teachers to understand the needs of the learners to accommodate the teaching methodology.

Linguistically, ME is characterized as a combination of general English and a form of ESP that is terminology heavy, along with extensive uses of abbreviations, acronyms, and long noun phrases. The terminology varies not only among the branches of service, but also for specific military-related tasks. Moreover, the use of terminology and L1 speaker adaptations of this terminology need to be utilized under occupationally distinct conditions, such as noise (Nakashima, Abel, and Smith Citation2018).

Although ME is described as challenging to teach and learn, cadets and officers acknowledge the importance of having high English language proficiency as military personnel. Moreover, motivation was found as a key factor for the learners. Studies showed that learners were eager to learn English. However, they emphasized the need for the language instruction to be clearly relevant to their military needs for specific tasks as opposed to simply for testing requirements (Orna-Montesinos Citation2018a), and for instruction to be delivered efficiently. Research highlighted a decline in motivation when these expectations were not fulfilled.

In terms of teaching approaches, both classroom-based and ICT approaches were commonly used, with a strong emphasis on the professional applicability of the language skills being taught. Teachers were also found navigating between the academic traditions of their institutions and meeting the military profession’s practical needs. Research on testing mirrored this need to balance the institutional demands and practical implementation of the tests. As a result, teachers designed tests that can be conducted efficiently or reflected the actual content being taught in the classroom.

Due to the limited number of studies identified in the scoping review, it is not possible to draw definitive conclusions. However, the research that was identified highlights the diversity of learners, ME language, and language use contexts. This diversity underscores the necessity for a thorough needs analysis concerning ME language, instruction, and assessment methods in order to identify the most effective approaches for preparing the learners to meet their practical needs. Specifically, research on the linguistic features across different military command levels (i.e. tactical, operational, or strategic) and within multinational military staff settings can deepen our understanding of the characteristics of ME. Such research can better inform the military education program and address the needs of various stakeholders. Beyond the research questions, however, three major features of ME language and education were identified: efficiency, the tension between L1 and L2 users, and the need to contextualize ME.

6.2. ‘Efficiency’ is key for ME teaching

The review of the literature suggests an underlying theme of ‘efficiency’ being key in teaching and learning ME. Learners prioritize content and skills that align with their specific needs, and see irrelevant material as demotivating (Farr Citation2016). ICT is employed for its efficiency in teaching (Fuentes-Luque and Campbell Citation2020) and assessment (Gawliczek et al. Citation2021), reflecting the need to accommodate the demanding schedules of military personnel. Consequently, focused instruction on ME terminology was well-received by students (Bogusz Citation2017). The use of CLIL can also be recognized as a time-efficient teaching approach for simultaneously teaching language and subject matter (Finardi et al. Citation2016). However, studies have also identified a misalignment among content and language teachers with respect to teaching approaches regarding intended learning outcomes (Nilsson and Lundqvist Citation2022), and a discrepancy between the curriculum objectives and students’ needs concerning intended language learning targets (Nakashima, Abel, and Smith Citation2018), that may hinder an efficient ME acquisition.

To improve the efficiency of ME education, research implies the need to facilitate explicit dialogue among the various stakeholders within the institution. This includes the interaction between the institution and teachers, and among the teachers. Studies suggest the need to align their perspectives regarding the curriculum, which encompasses not only the distinctive characteristics of ME and the essential skills required for effective communication during operations, but also the varied perspectives stakeholders hold towards the selected pedagogical approaches. The methods could include emphasizing vocabulary acquisition, improving communication abilities, utilizing ICT and CLIL.

Further research into the experiences of language teachers, including their collaboration between content and language instructors and the specific conditions for teaching and conducting research in military settings could provide valuable insights into improving teaching practices. Enhancing professional development opportunities that lead to instruction based on empirical evidence could significantly increase the ‘efficiency’ and effectiveness of teaching practices.

6.3. Tension between L1 and L2 use and users of English

Another persistent underlying theme identified is the tension between L1 and L2 usage and users of English. This tension is particularly evident in contexts where English serves as the working language in international settings. For example, in policy research, studies by Berthele and Wittlin (Citation2013) have highlighted issues in multilingual contexts, and Orna-Montesinos (Citation2018a) notes the challenges faced by L2 English users in environments where English is the lingua franca, such as in international military operations.

Furthermore, discrepancies between L1 and L2 users of English have been observed, with misunderstandings often arising due to the specific focus on ME terminology in L2 contexts. While some research points to general English language textbooks failing to meet the ME needs of learners (e.g. Alshabeb, Alsubaie, and Albasheer Citation2017), other studies highlight the tendency of L1 speakers to ‘overuse’ plain English rather than the specialized ME terminology (Park Citation2020, 352). Consequently, L2 users struggled to understand their L1 counterparts. This indicates the need to raise L2 users’ awareness of the importance of acquiring not only ME terminology, but also improving their general English language proficiency and the relevance of STANAG to their operations. Simultaneously, it becomes evident that L1 users of English need to be aware that they must learn and actually use the same pre-agreed ME terminology, such as the NATO terms, as their L2 partners. Moreover, it may be beneficial for L1 users to be tested on their proficiency in ME terminology to ensure their competence in interoperability.

This area of research holds promise for shedding light on the communication dynamics between L1 and L2 users in military contexts. It has significant implications not only for L2 learners and educators but also for L1 users operating within military settings. By addressing these issues, studies can contribute to broadening the scope of military English research, enhancing operational efficiency, and fostering cooperation among military personnel from varied linguistic, cultural, and occupational backgrounds.

6.4. The need to contextualize ME

The final point is the need for the contextualization of ME in the actual use contexts outside the classroom. The majority of the studies have decontextualized ME from its real-world use context, failing to understand its application, for example, under stressful conditions. Cadets, for instance, will use ME in military-specific situations, such as under time pressure, hunger, or sleep deprivation. The study by Nakashima, Abel, and Smith (Citation2018) was the only study that simulated this real-world ME use under one type of condition of loud noise.

Furthermore, the military operates within a hierarchical structure with a chain of command that must be followed, establishing a significant power dynamic. As such, officers may find themselves navigating power negotiations in their L2. As Orna-Montesinos (Citation2018a) notes, L2 speakers of English might feel inferior when communicating to L1 speakers in certain military settings, potentially hindering their ability to negotiate effectively in high-stakes situations. It is therefore crucial to understand how ME is utilized in contexts where power becomes relevant, and how L2 users can be better equipped to manage language use under high-stakes situations.

These language use conditions are rarely discussed in the second language acquisition (SLA) or ESP literature, highlighting the distinctive domain of ME. Implementing needs analyses through an ethnographic approach could provide deeper insights into the actual conditions of language use. For example, Rautiainen, Haddington, and Kamunen (Citation2023) employ conversation analysis to explore negotiation processes during United Nations (UN) peacekeeping field training sessions. Research approaches such as these may yield a more concrete understanding of the language use context, features of the language, and the difficulties L2 users encounter in the field during actual military operations.

6.5. Evaluation of the studies

One insight from the scoping review is the need for more rigorous research in the area of ME. For instance, several studies were omitted during the process due to the absence of an empirical research design. Many of these studies merely suggested a teaching method without assessing the effectiveness of that approach through measurement tools, such as tests or questionnaires. Several studies, even those included in the final stages of the analysis, lacked clear statements of research questions or lacked specificity in their research tools (e.g. questionnaire form). Such weaknesses may hinder the reader from fully comprehending the study, evaluating the outcomes, and conducting any replication studies. Moreover, the quality of the writing in some of the peer-reviewed articles was notably poor to the extent that it impeded comprehension. This issue could be attributed to the studies being conducted in EFL and ESL contexts, and possibly poor peer-review processes. Nevertheless, in order for ME language research to yield meaningful contributions, future studies need to be conducted with a higher standard of quality.

Moreover, some limitations remain in the current study. The focus was on ME, deliberately excluding fields such as UN peacekeeping and aviation communication. As a result, studies focusing on intercultural communication were also excluded from our search since these did not focus on English per se (e.g. Orna-Montesinos Citation2018b). Further, the search did not yield book chapters, possibly due to the ‘peer-review’ criteria in the database. Broadening the search criteria might have resulted in more hits, especially publications before 2010. A systematic literature review that includes conference proceedings, book chapters, and non-empirical articles would complement our findings, and potentially shed further light on publication patterns in the last 30 years. Nevertheless, the overall volume of research on Military English remains comparatively low, especially when contrasted with the abundance of studies on general English language proficiency or academic English language teaching and learning. This underscores the need for further investigation in this area.

7. Conclusion

This scoping review aimed to investigate research within ME language teaching, learning, testing, and use, in order to identify current findings available in the field and to inform on gaps for future research. Despite military language education and research being trailblazers of the field of applied linguistics research, ME language education research is a relatively new research domain. Most existing research focuses on learning, teaching, and motivation in ME, with testing, policy, use, and linguistic features receiving minimal attention. The study indicated a wide range of variables that ME teachers need to consider: ME terminology for a range of tasks and contexts, adaptive and efficient approaches to teaching, and possible linguistic discrepancies between L2 and L1 users. Consequently, the study emphasizes the importance of NATO and other stakeholders interested in military interoperability to better align policy and practice with context-specific ME education needs. By grounding both policy and educational approaches in research, ME teaching and learning can be conducted more effectively and efficiently. However, we found that there is relatively little research in this area that is academically and methodologically rigorous. This study highlights the need for acknowledgement of ME as a domain of research of its own, and calls for contributions from researchers and educators across various fields.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aki Siegel

Aki Siegel is a Senior Lecturer at Stockholm University and an Assistant Professor at Uppsala University, Sweden. Her research focuses on second language use, learning, and teaching. She is interested in analyzing changes and learning occurring in and through interactions, and considering the ways in which classroom teaching and learning can be improved based on empirical research findings.

Michaela Vance

Michaela Vance is a lecturer in English at the Swedish Defence University, Sweden. With a PhD in eighteen-century English literature, her main interest lies in literature, ethics, and education. Her current research broadly focuses on aspects of virtue and education, past and present.

Diana Nilsson

Diana Nilsson is a lecturer in English for Specific Military Purposes as well as Intercultural Communication for strategic military purposes at the Swedish Defence University, Sweden. With an M.A. in teaching ESL, her current research interests include corpus based and data-driven learning as well as intercultural communication in highly specialized and high-stakes contexts.

References

- References with an asterisk indicate that it was included in the scoping review.

- *Abd Rahman, E., M. Md Yunus, H. Hashim, and N. K. Ab Rahman. 2022. “Learner Autonomy Between Students and Teachers at a Defence University: Perception vs. Expectation.” Sustainability 14 (10): 6086.

- *Alqahtani, A. F. 2017. “A Study of the Language Learning Motivation of Saudi Military Cadets.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature 6 (4): 163–172.

- *Alqahtani, A. F. 2018. “English Language Learning Motivation and English Language Learning Anxiety in Saudi Military Cadets: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach.” Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) 9 (3): 45–60.

- *Alqahtani, A. F. 2020. “The Relationship Between the Saudi Cadets’ Learning Motivation and Their Vocabulary Knowledge.” English Language Teaching 13 (4): 1–10.

- *Alshabeb, A., F. H. Alsubaie, and A. Z. Albasheer. 2017. “English for Specific Purposes: A Study Investigating the Mismatch Between the ‘Cutting Edge’ Course Book and the Needs of Prince Sultan Air Base Students.” Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) 8 (3): 376–391.

- *Alshehab, M. 2014. “The Translatability of Military Terms by MA Students in Translation at Yarmouk University in Jordan.” International Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies 2 (3): 56–62.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32.

- *Berthele, R., and G. Wittlin. 2013. “Receptive Multilingualism in the Swiss Army.” International Journal of Multilingualism 10 (2): 181–195.

- BILC. 2024a. Policy Documents. Retrieved February 29, 2024 from https://www.natobilc.org/en/products/policy-documents-bilc-documents/.

- BILC. 2024b. STANAG 6001. Retrieved February 29, 2024 from https://www.natobilc.org/en/products/stanag-60011142_stanag-6001/.

- *Bogusz, D. 2017. “Teaching English Military Terminology in Military Classes.” Safety & Defense 3 (1): 31–36.

- *Chen, L., K. Chang, and S. Yang. 2021. “An Integrated Corpus-Based Text Mining Approach Used to Process Military Technical Information for Facilitating EFL Troopers’ Linguistic Comprehension: Us Anti-Tank Missile Systems as an Example.” Journal of the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka 49: 403–417.

- Chong, S., and L. Plonsky. 2023. “A Typology of Secondary Research in Applied Linguistics.” Applied Linguistics Review. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2022-0189.

- Chong, S. W., and H. Reinders. 2022. “Autonomy of English Language Learners: A Scoping Review of Research and Practice.” Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221075812.

- Crossey, M. 2005. Improving Linguistic Interoperability. NATO Review. https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2005/06/01/improving-linguistic-interoperability/index.html.

- *de Fourestier, J. 2010. “Official Languages in the Armed Forces of Multilingual Countries: A Comparative Study.” European Journal of Language Policy 2 (1): 91–110.

- Di Biase, M. J., and F. Gratton. 2015. “Interpreting the Speaking Performance Requirements of Forward air Controllers.” In Language in Uniform, edited by H. Joyce, and E. Thomson, 2–17. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- DLIFLC. 2023. Languages offered. https://www.dliflc.edu/about/languages-at-dliflc/.

- *Farr, K. 2016. “A Study Into the Motivation of Swedish Military Staff Officers to Learn English.” Konin Language Studies 4 (4): 391–413.

- *Finardi, K. R., N. Silveira, C. de Alencar, and J. G. D. 2016. “First Aid and Waves in English as a Foreign Language: Insights from CLIL in Brazil.” Electronic Journal of Science Education 20 (3): 11–30.

- *Fuentes-Luque, A., and A. P. Campbell. 2020. “Using Subtitling to Improve Military ESP Listening Comprehension.” Ibérica 40: 245–266.

- *Gawliczek, P., V. Krykun, N. Tarasenko, M. Tyshchenko, and O. Shapran. 2021. “Computer Adaptive Language Testing According to NATO STANAG 6001 Requirements.” Advanced Education 17: 19–26.

- *Grafeeva, C. V. 2020. “Formation of a Stable Positive Motivation to Study with Senior Students of Higher Military Educational Institutions by Creating a High Loyalty Atmosphere” Apuntes Universitarios 10 (4): 204–218.

- *Grande, B., C. D. Leishman, and H. K. Skilleås. 2022. ““I Can’t Come to the Words”: Effects of Including Military Flavour When Testing the Oral Proficiency of Norwegian Joint Terminal Attack Controllers.” English for Specific Purposes 68:73–86.

- Green, R., and D. Wall. 2005. “Language Testing in the Military: Problems, Politics and Progress.” Language Testing 22 (3): 379–398.

- *Hung, Y.-J., and S.-M. Chao. 2021. “Practicing Tiered and Heterogeneous Grouping Tasks in Differentiated EFL Classrooms at a Military Institution in Taiwan.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 41 (3): 405–423.

- Hutchinson, T., and A. Waters. 1987. English for Specific Purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- *Jodaei, H., G. Zareian, M. R. Amirian, and S. M. R. Adel. 2018. “From the State of Motivated to Demotivated: Iranian Military EFL Learners’ Motivation Change.” The Journal of Asia TEFL 15 (1): 32–50.

- Jones, I., and L. Askew. 2014. Meeting the Language Challenges of NATO Operations: Policy, Practice and Professionalization. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Juhl Kristensen, A., and K. Kildevang. 2019. In Demand, Yet in Decline: English in the Professional Military Education in Denmark. BILC Annual Conference, Tartu, Estonia. https://www.natobilc.org/en/product/43-2019-tartu-estonia-from-the-classroom-to-the-boots-on-the-ground-the-stakeholders-perspective-/.

- Kaplan, J. D., M. A. Sabol, R. A. Wisher, and R. J. Seidel. 1998. “The Military Language Tutor (MILT) Program: An Advanced Authoring System.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 11 (3): 265–287.

- Keagle, J. M., and T. G. Petros. 2010. “Building Partner Capacity Through Education: NATO Engagement with the Partnership for Peace.” Connections 10 (1): 46–63.

- *Kurum, Y. E. 2011. “The Effect of Motivational Factors on the Foreign Language Success of Students at the Turkish Military Academy.” Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language) 5 (2): 299–307.

- *Lahodynskyi, O., K. Mamchur, and V. Skab. 2018. “English Spycraft Professionalisms as a Linguistic Phenomenon.” Advanced Education (9): 178–184.

- Maiier, N., and V. Yukhymenko. 2022. “Mobile Technologies in the Development of Rofessionally Oriented English Speech Interaction Competence in Information Systems and Technology Military Students*.” ІCT and Learning Tools in the Higher Education Establishment 2 (88): 115–125.

- Mays, N., E. Roberts, and J. Popay. 2001. “Synthesising Research Evidence.” In Studying the Organisation and Delivery of Health Services: Research Methods, edited by P. Allen, N. Black, A. Clarke, N. Fulop, and S. Anderson, 188–220. London: Routledge.

- McCormick, J. R. 1970. “History of Foreign Language Teaching at the United States Military Academy.” The Modern Language Journal 54 (5): 319–323.

- Monaghan, R. 2012. “Language and Interoperability in NATO: The Bureau for International Language Co-Ordination (BILC).” Canadian Military Journal 13 (1): 23–32.

- Munn, Z., M. D. J. Peters, C. Stern, C. Tufanaru, A. McArthur, and E. Aromataris. 2018. “Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing Between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (143): 1–7.

- *Nakashima, A., S. M. Abel, and I. Smith. 2018. “Communication in Military Environments: Influence of Noise, Hearing Protection and Language Proficiency.” Applied Acoustics 131: 38–44.

- NATO. 1994. Partnership for Peace: Framework Document. Retrieved March 1 from https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_24469.htm.

- NATO. 2023. NATO Education and Training for IO, PSYOPS, PA and StratCom. https://www.act.nato.int/our-work/communication-discipline-training/.

- NATO Term. 2024. NATO Terminology Database. https://nso.nato.int/natoterm/Web.mvc.

- *Nejković, D., and J. Bošnjak. 2020. “Needs Analysis in English for Security Studies.” Scripta Manent 15 (2): 16–36.

- *Nenko, Y., V. Yaryhina, and V. Vorona. 2021. “Examining Officers’ Readiness for Foreign Language Intercourse in International Operations.” Revista Práxis Educacional 17 (46): 465–487.

- Niculescu, B.-O., G. Obilişteanu, and I. A. Dragomir. 2019. “Contribution of Foreign Languages to Building the Professional Career of the Land Forces Academy Cadets.” Land Forces Academy Review 24 (3): 213–219.

- *Nilsson, D., and S. Lundqvist. 2022. “Identifying Weaknesses of CLIL in the Military Higher Education Classroom.” Journal of Teaching English for Specific and Academic Purposes 10 (2): 217–243.

- *Noguera-Díaz, Y., and P. Pérez-Paredes. 2019. “Register Analysis and ESP Pedagogy: Noun-Phrase Modification in a Corpus of English for Military Navy Submariners.” English for Specific Purposes 53:118–130.

- *Orna-Montesinos, C. 2013. “English as an International Language in the Military: A Study of Attitudes.” Language for Special Purposes, Professional Communication, Knowledge Management and Cognition 4 (1): 87–105.

- *Orna-Montesinos, C. 2018a. “Language Practices and Policies in Conflict: An ELF Perspective on International Military Communication.” Journal of English as a Lingua Franca 7 (1): 89–111.

- Orna-Montesinos, C. 2018b. “Perceptions Towards Intercultural Communication: Military Students in a Higher Education Context.” In Using English as a Lingua Franca in Education in Europe, edited by Z. Tatsioka, B. Seidlhofer, N. C. Sifakis, and G. Ferguson, 225–249. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Oswald, F. L., and L. Plonsky. 2010. “Meta-Analysis in Second Language Research: Choices and Challenges.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 30: 85–110.

- *Park, K. 2016. “Employing TBLT at a Military-Service Academy in Korea: Learners’ Reactions to and Necessary Adaptation of TBLT.” English Teaching 71 (4): 105–139.

- *Park, M. 2020. “Investigating Target Tasks, Task Phases, and Indigenous Criteria for Military Aviation English Assessment.” Language Assessment Quarterly 17 (4): 337–361.

- Poteet, S., P. Xue, J. Patel, A. Kao, C. Giammanco, and I. Whiteley. 2008. Linguistic Sources of Coalition Miscommunication. NATO HFM-138 Research Task Group: Adaptability in Coalition Teamwork, Copenhagen, Denmark. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10098436/.

- Rautiainen, I., P. Haddington, and A. Kamunen. 2023. “Nudging Questions as Devices for Prompting Courses of Action and Negotiating Deontic (A)Symmetry in UN Military Observer Training.” In Complexity of Interaction: Studies in Multimodal Conversation Analysis, edited by P. Haddington, T. Eilittä, A. Kamunen, L. Kohonen-Aho, I. Rautiainen, and A. Vatanen, 217–252. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Richards, J. C., and T. S. Rodgers. 2014. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- *Solak, E. 2014. “English Learning Strategies of Various Nations: A Study in Military Context.” Hacettepe Üniversitesi Journal of Education 29 (2): 228–239.

- *Sovhar, O. 2021. “Using ICT to Form Foreign Language Communicative Competence of Future Armed Forces Officers.” Information Technologies and Learning Tools 85 (5): 259–269.

- *Synytsya, K., and G. Keremidchieva. 2011. “Language Assistance to Multinational Partners in Coalition Operations.” Information & Security 27: 111–120.

- Szvircsev Tresch, T., and N. Picciano. 2007. Effectiveness Within NATO’s Multicultural Military Operations (Cultural Challenges in Military Operations, Issue. C. M. Coops & T. S. Tresch. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep10333.5.

- University of the Bundeswehr Munich. n.d. Compulsory Language Training. https://www.unibw.de/sprachenzentrum-en/compulsory-language.

- *Velikova, G. 2019. “Shortening in the Language of the Navy.” Foreign Language Teaching 46 (5): 488–497.

- Wolf, H.-G. 2017. “De-escalation—A Cultural-Linguistic View on Military English and Military Conflicts.” In Advances in Cultural Linguistics, edited by F. Sharifian, 683–702. Singapore: Springer.

- Xiao, Y., and M. Watson. 2019. “Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 39 (1): 93–112.