ABSTRACT

Despite its pivotal role for virtuous circles of governance, legitimacy is rarely operationalized in state-building programmes. We question the nexus between legitimacy and statehood that is prevalent in most donor approaches. We argue that different legitimacy audiences as well as institutional isomorphic bias are keeping external actors from adopting legitimacy-centered approaches. However, tracing the evolution of the German approach to stabilization in Afghanistan from 2001 to 2014, we find that external actors may gradually adopt such an approach when subjected to domestic political pressure and given a threshold level of goal alignment between different audiences.

Introduction

The emerging research on governance in areas of limited statehood and the ‘local turn’ in state-building studies show that empirical legitimacy plays an indispensable role for effective governance provisions by non-state or international actors (Börzel and Risse Citation2016; Börzel and van Hüllen Citation2014; Krasner and Risse Citation2014; Lemay-Hébert Citation2009; Mac Ginty and Richmond Citation2013; Risse Citation2011). As Krasner and Risse (Citation2014, 547) succinctly note, ‘no legitimacy, no success’. But whereas legitimacy considerations have gained prominence in the policy debate on fragile states and state-building (DFID Citation2016; World Bank Citation2011) and assumptions about a virtuous circle between effective and legitimate governance have become common place, there is only scarce evidence of fully operationalized and legitimacy-centered approaches at the programming and implementation stages of policies and projects of international actors. To be sure, there are plenty of narratives and policy doctrines that allude to the notion of generating compliance with donor interventions by ways other than coercion or material incentives (Schmelzle Citation2011, 8): ‘Domestic ownership’, ‘domesticization’, ‘inclusive-enough pacts’, ‘social contract’ are terms commonly found in policy documents. But all too often, these terms are used as empty signifiers to convey legitimacy for practices that – upon closer inspection – do not take into account the full implications that a legitimacy-centered approach to external governance provision in areas of limited statehood would have to entail.

This article seeks to extract lessons for reflexive policy-making with regards to initiating and sustaining virtuous circles of governance in areas of limited statehood. It specifies the practical conditions that a truly legitimacy-centered approach to external governance has to satisfy and explores the reasons why donors struggle to operationalize such an approach. It probes an empirical case of prolonged donor intervention in such areas to gain knowledge about the conditions under which external governance actors converge towards legitimacy. Still, research and policy lack a common heuristic language. This contribution seeks to generate mutual perspectives on legitimacy-centered approaches to donor interventions and offer policy recommendations of how such an approach can be integrated into standard operating procedures.

Our article proceeds in four analytical steps. First, we conceptualize legitimacy and delineate the policy implications of the evidence on the importance of empirical legitimacy for effective governance provision in areas of limited statehood along the line of the virtuous circle argument (see Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018). Second, we hypothesize about reasons for why legitimacy-centered approaches are rarely operationalized in donor programmes. Reviewing the institutionalist literature, we seek to reveal the mechanisms within donor organizations and agencies that incentivize top-down programme designs. Third, we track Germany’s stabilization approach as part of the international intervention in Afghanistan 2001–14. This case probe allows us to observe and trace the evolution of a major donor’s governance interventions over a compressed period of time and to identify mechanisms through which a legitimacy-centered approach eventually and incrementally took hold. In our concluding discussion, we discuss policy recommendations for state-building that follow the virtuous circle theory of providing effective and legitimate governance.

Concept(s) of legitimacy

Legitimacy can be considered to be a normative status that determines whether an institution, actor or action is worthy of being accepted and/or justifiable (Draude, Schmelzle, and Risse Citation2012). Generally, there are two ways of conceptualizing legitimacy, often referred to as ‘empirical’ and ‘normative’ legitimacy respectively (Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018). Whereas the former perspective refers to the empirical distribution of legitimacy beliefs in a given constituency, the latter one emphasizes how governance ought to look like in order to be considered legitimate by certain standards that are derived from abstract, normative considerations. It is important to note that the two are not identical – not least because not every individual is making such abstract normative considerations. The instability of a government in an area of limited statehood, for instance, might be caused by a significant loss in empirical legitimacy among most of the population even if this government came into power following procedures that – measured against an abstract standard – would have to be considered perfectly legitimate.

For the purposes of our argument, empirical legitimacy is of particular importance, because it is empirical legitimacy that increases the chances of the governed to voluntarily follow the rules established by the governors. In other words, it significantly increases the chances of governance to be effective because it produces ‘stable compliance without costly enforcement mechanisms’ (Schmelzle Citation2011, 8). It does so by creating a habitual belief that ‘rules and regulations are entitled to be obeyed by virtue of who made the decision or how it was made’ (Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Citation2009, 354) – without in every single case considering the content of rules and regulations. It thus establishes a right to rule (Gilley Citation2009) or ‘content-independent’ compliance (Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018).

There are two more differentiations which are relevant for our discussion. First, there is the familiar distinction between input and output legitimacy (Scharpf Citation1999). Input legitimacy focuses on sources of legitimacy derived by procedural aspects of authorization (governance of and by the people). Output or performance-based legitimacy refers to actual governance achievements or outcomes (governance for the people). As we will see in the subsequent case study, both types of sources are relevant for the activities of external actors within contexts of state-building. On the one hand, external actors often provide certain governance services themselves, substituting for performance deficits of weak domestic institutions (output side); on the other hand, terms like domestic ownership are referring to the input or procedural sources of legitimacy in terms of integrating domestic actors in the design and implementation of certain projects or measures.

Second, there is the distinction between external and domestic governance actors. Empirical legitimacy is relevant for any governance actor as all of them are dependent on voluntary compliance (unlimited control and enforcement capacities are a theoretical extreme). This applies in particular to domestic governance actors in post-conflict and state-building contexts as the power-holders may be new to office, the respective institutions may still be unstable and major challengers might not have left the scene resulting in the ‘fragmentation of legitimacy audiences’ (von Billerbeck and Gippert Citation2017, 273). At the same time, the legitimacy of domestic governance actors is a major concern for external interveners interested in local stability. But these external interveners often act as governance actors as well – be it instead of, next to or in cooperation with domestic governance actors. Given the universalistic norm of self-determination as a governance principle, external interveners are – all other things equal – in a structurally even more difficult position. That is to say that external governance actors will rarely achieve the attribution of intrinsic legitimacy, i.e. rule compliance without considerations of utility (see Ciorciari and Krasner Citation2018; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018). Therefore, such actors are particularly dependent on governance addressees attributing (empirical) legitimacy based on performance, i.e. effective service provision. It is in this context that legitimacy becomes a more or less necessary condition for any successful governance effort. Crossing these two distinctions yields a 2 × 2-matrix that we will use in the subsequent discussion.

The isomorphic bias

The lack of legitimacy-centered approaches to external governance provision in areas of limited statehood does not stem from a lack of acknowledgement. In fact, the broader notion of legitimacy as a constitutive component of effective governance has been firmly established in the aid and development doctrines over the past two decades. However, academic terminology is often avoided in favour of more established and accessible vocabulary like ‘domestication’ or ‘buy-in’. The most universally acclaimed concept, however, is that of local ownership, i.e. the idea that ‘[p]artner countries exercise effective leadership over their development policies, and strategies and co-ordinate development actions’ (OECD Citation2008, 3). The concept of ownership is multi-faceted, its adoption in aid programming may often stem from consequentialist than normative considerations, and the adherence to its pillars in practice is often loose or inconsistent (von Billerbeck Citation2017; Westendorf Citation2018). And yet, the local ownership-discourse provides the most frequently used vocabulary, which external governance actors use to implement activities that draw on causal effects of empirical legitimacy.

Local ownership figures prominently as one of five Partnership Commitments in the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (OECD Citation2005, Citation2008) and has only become more prominent since. The New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States between donors and 19 fragile and conflict-affected states that was signed in Busan in 2011 equally contains donors’ commitment to support ‘inclusive country-led and country-owned transitions out of fragility’ (IDPS Citation2011, 2). In the same vein, individual donor countries with substantial stabilization portfolios in areas of limited statehood emphasize ownership to describe their state-building goals. The UK’s ‘Approach to Stabilisation’ states, for example, that it is ‘important to ensure that opportunities to build domestic capacity and promote domestic ownership during stabilisation interventions are not ignored … ’ (Stabilisation Unit Citation2014, 9).

Why then is the global development rhetoric ‘decoupled’ from donor practices (Gizelis and Joseph Citation2016, 539)? We argue that there are two principal reasons. First, the concept of ownership is an ‘empty signifier’, almost devoid of definitional boundaries and hence easy to use strategically by donors and recipients alike (Arndt and Richter Citation2009). The conceptual vagueness has arguably fuelled the popularity of ownership because it can accommodate different ideas of different legitimacy audiences (Mac Ginty and Richmond Citation2013). In turn, this vagueness leaves a lot of discretion to donors to apply a ‘business as usual’ approach, where rhetoric and practice widely diverge (Reich Citation2006, 4; see Bendix and Stanley Citation2008; Reich Citation2006; von Billerbeck Citation2015).

The second component is the isomorphic pressure that exists in any organization. This concept draws on the work of DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) and other scholars who have characterized international aid and development as distinct organizational fields, in which organizations change not necessarily to improve effectiveness or efficiency, but in response to the pressure to conform to prevalent norms and expectations in their respective field. The consequence of isomorphic pressure is convergence of formal structures, normative frameworks and standard operating procedures among organizations that work in the same field and are exposed to similar pressures.Footnote1

External actors in areas of limited statehood are particularly susceptible to isomorphic pressures because they must address different legitimacy audiences whose conceptions of effective and legitimate governance do not necessarily align (Ciorciari and Krasner Citation2018; Coleman Citation2017).Footnote2 The condition of multiple legitimacy audiences is often overlooked, but critically undermines the shared social goals-assumption that is implicit in the virtuous circle (Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018). As governance actors, donors will ultimately be more responsive to their domestic legitimacy audience, in our empirical case Members of Parliament (MPs) in the German Bundestag as well as the broader public, because they depend on it for funding and approval. Overlapping debates among domestic audiences of other peers (e.g. other troop-contributing countries) can have an amplifying effect on this type of domestic pressure. To put it bluntly, any donor in fact does adhere to a legitimacy-centered approach, albeit towards an audience that is not affected by the governance that it provides in areas of limited statehood.

In sum, we speak of the institutional isomorphic bias to argue that the vagueness of ownership (or other legitimacy-centered doctrines) and the inherent isomorphic pressures create systemic disincentives to pursue a legitimacy-centered approach. Instead, donors are induced to engage in ‘organized hypocrisy’ (Lipson Citation2007). The emerging literature that constitutes the ‘local turn’ in state-building studies provides ample evidence on the isomorphic bias of external governance actors, the strategic agency of governance recipients and the hybrid orders that emerge as a result (Mac Ginty and Richmond Citation2013; Richmond Citation2013; Schröder, Chappuis, and Kocak Citation2014). With regards to legitimacy, for example, ‘ownership’ is often assumed when formal elections have been held after external intervention (often to validate intervention outcomes retrospectively). But elections are not necessarily a relevant source of legitimacy in areas of limited statehood. Sources of legitimacy may be quite diverse and include hereditary appointment or ethnic bonds. But due to the isomorphic bias towards formalized modes of legitimation prevalent in their home society, donors may be blind to the actual local normative standards,

What are the consequences for the actual practices of state-building? First, the isomorphic bias restricts donors’ range of options. Tailoring interventions to the respective local context can incur prohibitive reputational costs in front of the domestic legitimacy audience (Denney Citation2014). Whereas, for example, the audience of governance recipients would demand to work with informal justice institutions as the most widely accepted and most reliable source of justice, cooperation with them may prove impossible for donors due to these institutions’ disregard for human rights. A second consequence is a conflict of objectives in terms of the attribution of performance-based legitimacy, which is another chain link in the virtuous circle. Organizations that contribute to state-building interventions or provide aid have an incentive to ‘be visible’, whereas state-building doctrine would demand that effective governance provision is attributable to the domestic state (Winters, Dietrich, and Mahmud Citation2018).

The third and perhaps most problematic consequence of the isomorphic bias is the pressure on domestic organizations in areas of limited statehood to conform to donors’ institutional blueprints instead of developing institutions that may be considered most appropriate by their domestic governance recipients. As scholars of the ‘local’ in statebuilding interventions have shown, domestic organizations are typically either coerced into conforming (especially in environments of military interventions and executive state-building mandates) or inclined to engage in mimetic isomorphism as to gain acceptance and funds by the external donor (Ismail Citation2016; Pritchett and de Weijer Citation2010; Schröder, Chappuis, and Kocak Citation2014).Footnote3 Institutions in areas of limited statehood that mimic those in areas of consolidated statehood are ill-fitted to their context, however, which leads to unintended and often adverse effects. Only when unintended or persistent negative impacts travel back to the domestic legitimacy audience (e.g. troops lost in combat, cost-overruns, negative press coverage) and threaten donors’ legitimacy, these actors may adopt more legitimacy-centered approaches. This adaptation process may yield case-specific improvements, but not necessarily a sustained change in how donors approach interventions in the future.

Case probe: Germany’s stabilization interventions in Afghanistan, 2001–2014

This section applies our concept and tests our assumptions in a case probe of Germany’s interventions in Afghanistan, 2001–14. We trace Germany’s interventions in Afghanistan along critical junctures to showcase how this donor’s approach developed over time and to highlight implications for the virtuous circle argument. Germany started contributing to UN-mandated peacekeeping and peacebuilding missions shortly after re-unification in 1990. But it did not assume a leading role in international interventions and ensuing state-building until Kosovo 1999. We chose Germany for this analysis because of a number of reasons: First and most important, Germany is a relative new-comer to international state-building interventions. It does not have an extensive colonial past and has completely severed institutionalized practices of occupation as practiced in World War 2. Accordingly, we are able to study an actor’s stabilization practices who cannot take recourse to institutional path dependence or established scripts for similar engagements from its own history. The choice of Germany thus allows for the observation of the dynamic development of an intervention policy in situ. It may be argued that Germany’s need to develop its approach from the ground up could have made it likely that it has taken cues from other, more experienced actors in the field. If so, the case selection would make for a conservative estimate because we could have expected Germany to take other actors’ experiences into account and focus from the beginning on aspects of legitimacy in its policies. As we will see, however, this was not the case – which strengthens our argument about the isomorphic bias that cannot easily be bypassed by international example. Second, the choice of Germany complements the literature that hitherto has strongly focused on state-building practices of the United States and the United Kingdom, while much less is published about ‘middle-weights’ such as Germany. Finally, we focus on an external governance actor that complements the analyses of other donors covered in this special issue.

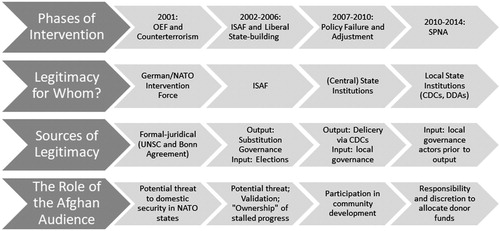

For our analysis we draw on a range of primary documents on Germany’s intervention history in Afghanistan such as resolutions submitted by the Federal Government of Germany (Bundesregierung, abbreviated as BReg in the following sections) to the German Bundestag (the national parliament) to mandate German troop deployments, written answers to inquiries by Members of the Bundestag, as well as the annual progress reports, which were published 2010–14. We identify four distinct intervention periods, which are delineated by critical junctures in Germany’s engagement in Afghanistan.Footnote4 We use our concept as a heuristic to derive BReg’s operating concept or cognitive script (Scott Citation1994) for each intervention period. We assess whose legitimacy BReg sought to utilize or impact (e.g. Germany’s legitimacy, the central state’s legitimacy) and whether the interventions primarily aimed at the input (authorization) or output (performance) sources of legitimacy.

First phase: October – December 2001

Germany’s engagement in Afghanistan began in response to the September 11th terror attacks on the United States when the country joined Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) to oust Al-Qaeda and the ruling Taliban regime from Afghanistan. OEF was authorized by United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1368 and 1373 (BReg Citation2001a). This initial intervention period is noteworthy for the lack of addressing the Afghan population as a legitimacy audience at all. The Federal Government justified its interventions primarily towards its domestic audience and by reference to normative (formal-juridical) sources of legitimacy such as the Security Council Resolutions. After all, Operation Enduring Freedom sought to provide security primarily for the populations residing in NATO countries. During this phase, Afghans were conceived of as potential security risks. The performance-based or output dimension of governance was thus highly securitized (BReg Citation2002, 2, Citation2006a, 2). The military victory of Operation Enduring Freedom was followed by the NATO International Security Assistance Force (ISAF).

Second phase: 2002–2006

The deployment of ISAF in December 2001 marks the second phase and was characterized by state-building activities that followed the script of liberal peacebuilding in that it relied heavily on broad causal assumptions of performance-based legitimacy.Footnote5 At this stage, ISAF first attempted to address the Afghan audience and sought attribution of legitimacy to the international presence. There was hence little incentive to invest in local governance structures. The envisaged input channels were heavily formalized and designed to validate the decisions taken at the level of international diplomacy. The high voter-turnout in the 2004 presidential elections was taken as ‘a clear signal of the population against terrorism’ (BReg Citation2004, 2). Afghans were awarded more agency in official doctrine, because they were to ‘carry the responsibility for security and order’ (BReg Citation2001b, 1). But this paternalistic and securitized notion of Afghans needing external support to become resilient against extremism and terror did not allow for substantial input in ISAF governance practices.

The concept of an Afghan legitimacy audience as well as the notion of empirical legitimacy first entered German policy through the concept of ownership, which was introduced in BReg’s (Citation2003) Strategy for Afghanistan. The Strategy shifted the focus from anti-terrorism to state-building and the attempt to extend the reach of the Afghan central state ‘through enhanced civilian and military engagement beyond Kabul and its surrounding area’ (BReg Citation2003, 3). This shift was accompanied by a transfer of responsibility from ISAF to Afghans by promoting ‘Afghan ownership’ (BReg [Citation2006b, 2]; see also BReg [Citation2007, 17–18]), which can be read as a deliberate attempt to influence the attribution of performance-based legitimacy: ‘The primary objective is improving living conditions for the population while also promoting the establishment of transparent, capable and assertive state institutions’ (BReg Citation2008, 27). Whereas this marks a shift towards concerning itself with attribution of legitimacy from Afghans to their state, BReg also maintained a focus on generating legitimacy among the German public by highlighting the security dividend of preventing Afghanistan from ‘becoming a safe haven for international terrorists again’ (BReg Citation2003, 2).

The German government bureaucracy grappled with the obvious dissonance between the cognitive scripts (first provide services, then build a state) and the empirical reality. BReg noted substantial improvements in basic services such as education, health and even complex services such as policing: ‘The Afghan police is ready to take care of its primary duties (…). The presence of the police on the streets of the major cities has improved visibly’ (BReg Citation2006c, 2). And indeed, during this time, service provision improved as evidenced, for example, in rising literacy ratesFootnote6, particularly among women. However, in noting stagnation and significant problems in advancing the reach of the Afghan central state throughout its territory, ‘corruption and nepotism’ among domestic power-holders were identified as barriers to more palpable impact (BReg Citation2007, 17–18). This perception corresponded with the dominant discourse of shifting responsibility to Afghan agency (Afghan ownership) without awarding Afghans substantial input in the governance system.

Third phase: 2007–2010

The third phase of Germany’s stabilization engagement was marked by domestic pressure from the German parliament, the Bundestag, as BReg’s principal audience, in the face of the growing Taliban insurgency as well as the perceived lack of progress in state-building around 2006. In having to respond to growing criticism from domestic audiences, Germany was not alone among troop-contributing states. The dominant script used to legitimize the vast deployment of resources up to this point towards domestic audiences in NATO member states had been coated in a narrative of linear progress that stood at odds with the realities on the ground. The German government bureaucracy had to shift its approach and relativize the role of formal state institutions. The altered approach pivoted towards more input-centered sources of legitimacy, localized outputs and the strategic goal of attributing positive impacts to Afghan state institutions.

The growing frustration was palpable in earlier reports, which had noted grave problems in state-building in 2006 (BReg Citation2006d, 2–6). Whereas prior, BReg had referenced Afghan ownership in an abstract sense, it now reflected that attribution of legitimacy was in fact lacking, but needed, to attain BReg’s strategic goals: ‘ … we must take the events of 29 May 2006 as a warning to not presume the approval of the international engagement by the population uncritically, which is probably most required to succeed’ (ibid.). In other words, Germany no longer conflated a normative-juridical and an empirical perspective on legitimacy and explicitly reflected problems of different social values and goals among the audience of governance recipients.

Reports from that time took care to differentiate between legitimacy assigned to the state on the one hand, and to ISAF and external actors on the other. BReg even noted with some frustration that ‘successes are more commonly assigned to the Afghan government, whereas failures are attributed to the international community of states’ (BReg Citation2010, 51). The documents also reflected the nexus between performance-based and input-based sources of legitimacy by noting that the uneven service delivery by the international Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) across the Northern provinces of Kunduz, Takhar and Badakhshan had left some people in those areas feeling that the international community was ‘less engaged’ (BReg Citation2007, 34).Footnote7 This was also the phase of the intervention, from which onwards BReg would regularly cite public opinion surveys to back up empirical claims.

The most marked change at this stage was the shift away from central statehood. BReg described the deficiencies of the Afghan central state in no uncertain terms: ‘lack of a state monopoly on violence, lackluster determination, arbitrary decision-making as well as insufficient staff capacities’ (BReg Citation2010, 41). The practical conclusion drawn from this frank assessment was to devolve power away from the centre and towards the provinces, noting strategically that ‘most Afghans experience their state at the domestic level’ (BReg Citation2010, 44) and that ‘the constitution of Afghanistan as a central state is not congruent with the country’s tradition and history’ (BReg Citation2011, 37).

The development of a new operational script based on this re-assessment followed a pattern of normative isomorphism because it resulted from political pressure from Germany and led to a convergence of institutionalized structures and practices with that of other donors, who were exposed to similar pressures (see section 3). It is best illustrated by reference to the National Solidarity Program (NSP), which had been created by the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development with strong international donor support in 2003. It had the aim of empowering Afghan village communities to identify and manage their own development projects. A key feature of the NSP was the investment in local governance structures, notably the establishment of Community Development Councils (CDCs). While these were governance structures that worked in parallel to state institutions, membership was based on free elections at the community level and most Afghans perceived them as state institutions (Böhnke, Köhler, and Zürcher Citation2017).Footnote8 Accordingly, donors hoped that CDCs would serve as ‘bridges between Kabul and the local population’ (BReg Citation2011, 37). A similar bilateral instrument employed by BReg were flexible regional development funds, which could be appropriated by local administrators according to local needs after having undergone training on basic administrative skills such as monitoring and evaluation, accounting and planning (BReg Citation2011, 37). The third phase was thus characterized by acknowledgement of the need for attribution of legitimacy by the Afghan population towards Afghan state institutions (as opposed to the international presence) as well as a shift towards investing in local governance.

Fourth phase: 2010–2014

The fourth phase of Germany’s stabilization engagement was marked by further institutional convergence towards the NSP outline. It led to a full embrace of investments in local governance, exemplified in the so-called Stabilisation Program for North Afghanistan (SPNA). This programme was part of the military surge of ISAF troops in Afghanistan to counter the Taliban insurgency and was conceived of late in 2009. At this point, BReg emphasized rupture and learning to justify the shift towards a counter-insurgency strategy (COIN), asserting it as necessary response to ‘negative developments’ in Afghanistan and as needed for ‘learning straightforward lessons from previous deficits’ (BReg Citation2010, 43). COIN invariably led to a spike in violence 2009–11.Footnote9 Therefore, stabilization was meant to offset the negative impacts of increased violence by offering tangible ‘peace dividends’. The SPNA programme was one of several programmes with which BReg targeted the ‘focus provinces’ under German-led ISAF Regional Command North, namely Badakhshan, Baghlan, Balkh, Kunduz, Takhar and, since 2013, Samangan (in addition to the capital Kabul). BReg sequenced investments as to develop local governance structures before delivering outputs: ‘Strengthening structures at the province and district levels is a focus area of German engagement so that these structures are enabled to meet the basic needs of the population … ’ (BReg Citation2014, 20).Footnote10 SPNA was funded with €74 million and was operated by the state-owned German KfW Development Bank in cooperation with the non-profit Aga-Khan-Foundation and the French NGO ACTED. It was used to finance over 200 projects (BReg Citation2014, 12, 2014, 20).

Operationalizing input-based support to local governance structures as opposed to maintaining donor-devised and output-driven programmes constituted the true innovation. SPNA required that local decision-makers agree on communal needs and investment priorities as well as specific development projects in the areas of health, education, rural development and basic infrastructure. SPNA co-opted the Community Development Councils (CDCs) for this purpose. The German government credited the CDCs with expanding the reach of the Afghan state (BReg Citation2010, 45). At the same time, CDCs accommodated informal power equilibria and were heavily dominated by clan structures. Nonetheless, co-optation and formalization came with institutional adjustments to increase representation and accountability such as free elections to posts on the CDCs or reserved seats for women in the District Development Assemblies (DDAs). The empowerment of hybrid governance structures was hence accompanied by a pragmatic approach to conditionality that reflected a minimal consensus on how much more democratic the CDCs had to become in order to be eligible for external support.

CDCs submitted proposals to DDAs, which would forward them to Provincial Development Councils for selection and funding (BReg Citation2010, 46).Footnote11 The underlying theory of change hence sought to fully actualize legitimacy generated through substantive participation by governance addressees. In fact, the process placed a remarkable degree of decision-making and budget-allocating autonomy on local and hybrid governance structures, which also inhibited reputational as well as more tangible risks on the external donor (e.g. concentration of donor funds in specific districts or collusion between various layers in the shura complex). SPNA thus also reflected a shift towards strengthening congruence of social values and goals between the Afghan population and the governance provider – the CDCs and no longer ISAF – as precursor to ensure that Afghans would reward effective service provision with attribution of legitimacy to their local governance structures.

Emerging evidence from studies which utilized several rounds of household surveys in the same Provinces in Northern Afghanistan points to nuanced, but generally encouraging impacts of stabilization programmes on citizens’ perception of the state (Böhnke, Köhler, and Zürcher Citation2017; Stollenwerk Citation2018). Citizens who were exposed to SPNA projects and knew of the activities of their District Development Assemblies generally perceived their situation more secure in 2012 than in previous surveys. Where impacts of SPNA were perceived, respondents attributed more legitimacy to local state institutions, namely the DDAs. Other surveys taken in the same region at the time even show spill-over effects, e.g. towards increased levels of trust in state and local courts, which had not been the subject of the SPNA programme.Footnote12 There was also a modest improvement in perceptions of security.Footnote13 At the same time, strengthening state legitimacy appears to have come at a cost to social cohesion at the local level and even increased perceptions of corruption.

It comes as no surprise that parallel and subsequent interventions in Afghanistan were tailored according to the SPNA script. One example is the German government support to the Afghan NGO The Liaison Office (formerly known as Tribal Liaison Office TLO), which worked with traditional shuras and district councils in Southern, Eastern and Northern Afghanistan in order to improve their accountability and adherence to international standards, e.g. in human rights (BReg Citation2010, 46). There were also other areas, however, in which a focus on performance-based legitimacy was maintained. In areas that had just been recaptured from the Taliban and in which BReg funded employment of former combatants in infrastructure projects, the procurement of power transformers or the rehabilitation of critical infrastructures among other projects (BReg Citation2010, 33).

In sum, we conclude that the German government shifted from a performance-based approach and concern for its own legitimacy towards a model that approximates our outline of a legitimacy-centered approach (). The change was brought about by growing pressure by the German domestic audience on the government to change direction amidst highly publicized evidence of policy failure in Afghanistan. This criticism was echoed and the domestic pressure was arguably amplified by similar debates in other troop-contributing states.Footnote14 This created a rare moment of alignment of social goals and values between the German and Afghan legitimacy audiences, creating discretion for the German government to invest in local governance structures that did not always adhere to Western standards, but proved more apt to deliver governance in a way that facilitated the attribution of legitimacy through the chain links of the virtuous circle (see Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018). illustrates how Germany evolved from the lower right corner first to the lower left, then to the upper right, and finally also to the upper left corner.

Table 1. Evolution of Germany’s approach to legitimacy.

Towards the end of the massive deployment of ground forces in 2014, BReg conveyed a rare sense of strategic patience with the governance recipient’s deviance from the blueprint of liberal state-building, noting that ‘any type of substitution governance by the foreign partner out of impatience for hesitant Afghan decisions or due to the inefficiency of Afghan governance structures is wrong, regardless of whether it is pursued out of an (apparent) recognition of Afghan needs and altruistic motives’ (BReg Citation2014, 57). Ironically, the shift towards more legitimacy-centered governance occurred only briefly before NATO countries started their withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan in 2014.

While we are arguing that the German government has successfully shifted towards more legitimacy-centered governance, two deficits remain pertinent: First, whereas Germany developed and adjusted its approach as outlined, even programmes such as SPNA have yet to fully engage with the complex landscape of non-state governance actors in local districts. In many ways BReg piggy-backed on governance structures that had already been tested by other donors (normative isomorphism). Afghanistan’s governance landscape remains extremely diverse, which offers challenges for establishing a central state, but also opportunities to strengthen more legitimacy-centered governance. The second deficit is the lack of post-deployment institutional learning in the German bureaucracy. While an inter-agency lessons learned process took place, participants were eager to avoid blaming and results were not recorded systematically. In contrast to the military, there is no field manual for diplomats deployed to states of conflict. The quick turn-over of staff in the German Foreign Office, which coordinates the stabilization programmes within the Federal Government, hence leads to further fragmentation of institutional knowledge. Given the absence of similarly strong domestic pressures in stabilization arenas outside Afghanistan, this gives us reason to suspect that BReg will engage future state-building efforts similar to how it did in 2001. A paradigmatic shift to more legitimacy-centered governance has not taken place.

Conclusion: A legitimacy-centered approach to interventions in ALS

In this article, we have argued that based on compelling evidence, empirical legitimacy is a key condition for any successful governance intervention. Despite universal acclaim, truly legitimacy-centered approaches to such interventions are still rather rare. We have claimed that this is due to a specific incentive structure which translates into something we have called institutional isomorphic bias. This isomorphic bias induces external governance actors to systematically disregard local values, audiences and sources of legitimacy, while orienting themselves towards the preferences of a domestic audience, here understood as a group of actors that can act as a principal and can therefore (politically) sanction a governance actor as its agent.

In a case probe of Germany’s intervention in Afghanistan we have demonstrated that this particular external governance actor was able to overcome the isomorphic bias – but only gradually and reluctantly, following repeated (and sometimes blatant) failure of the initially preferred approach. This failure led to a rare alignment of pragmatic goals among the domestic and recipient audiences that permitted the German government to invest in local governance structures, which have subsequently been perceived as more legitimate governance providers. Our contribution thus highlights the importance of two key links in the virtuous circle running from effective governance provision to legitimacy, namely that the relevant audience of governance recipients in fact attributes legitimacy based on effective service provision (the instrumental legitimacy belief) and that they share the same social goals that provide the terms for assessing effectiveness (see McLoughlin Citation2018; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018).

These findings echo emerging insights from the ‘local turn’ in state-building studies, warranting a greater effort by the research community to devise innovative formats to promote the transfer and integration of these more recent research results in policy practice and particularly its standard operating procedures (akin to military field manuals). A necessary condition for this, however, would be an improvement in the compatibility of the respective heuristic perspectives, which – up to now – are quite different. Embedding themselves with practitioners over limited periods of time and engaging with pre-deployment training curricula may be fruitful first steps.

Not surprisingly, our recommendation to policy- and decision-makers is to embrace a legitimacy-centered approach on any kind of international intervention if not for its inherent value than for the simple sake of its effectiveness. This implies taking the social norms and goals of different legitimacy audiences seriously. Notions of what constitutes good governance, justice, appropriate political conduct etc. vary across the globe, across countries, even across sub-state regions. All these are bound by historical path-dependence and local normative concepts. A focus on empirical legitimacy requires that Western donors must look beyond what their domestic audiences may deem legitimate within the confines of liberal democratic nation-states. We do acknowledge, however that there is a systematic dilemma: While the simple export of Western models is not effective, taking the respective local perspective seriously is difficult to legitimize domestically. However, repeated and continuous failure and ineffectiveness of an intervention is at least equally difficult to pitch towards that audience. This consideration can be used as a lever to overcome domestic concerns.

How does a legitimacy-centered approach look like in practice? How does it relate to popular notions of state-building or stabilization? On the second question, we argue that a focus on legitimacy does not say anything about the goals of an intervention (state-building versus stabilization). It does, however, say something about the balance between the donor’s (and domestic audience) goals and the role of local actors in co-defining them. Legitimacy-centered can thus apply to long-term state-building as well as to short-term stabilization missions.

In practice, such an approach will have to start out with a comprehensive notion of legitimacy across all four fields of our schematics that need to be institutionalized among standard operating procedure for programming. On the output or performance side, it would imply a consistent localization in terms of local preferences for governance service. However, local preferences can only be aggregated by local governance structures. Hence, one should not de-couple performance-based from input-based sources of legitimacy. On the input-side, a legitimacy-centered approach has to take local concepts of procedural fairness seriously. It would thus have to look for locally accepted methods of participation and authorization. It remains true, however, that external actors cannot completely ignore the norms and goals of their domestic audience either. In a second step, international actors must thus enter into a discourse with their domestic constituencies with regards to minimum criteria of normative legitimacy (e.g. fundamental human rights).

Furthermore, a legitimacy-centered approach will have to actively resist the incentive structure and the pull of the isomorphic bias. As a follow-on step to adopting a comprehensive notion of legitimacy into standard operating procedures, donors should institutionalize structures and procedures as reflexivity checks, e.g. panels of academic experts, mandatory context/conflict analysis on-site, failure conferences, feedback loops, qualitative evaluation schemes and pre-deployment training. In addition, external actors should actively engage the domestic audience before, during and after engagement in order to get a sense of red lines and to manage expectations in order to mitigate isomorphic pressure at later stages of deployment. Putting legitimacy front and centre of any intervention increases not only effectiveness but also efficiency relative to political, financial and – in most cases – also human cost.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Felix Rüdiger for invaluable research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Gregor Walter-Drop is the Managing Director of the Center for Area Studies at Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

David Remmert is a Consultant on Stabilisation Processes with GIZ.

ORCID

David Remmert http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0327-0466

Notes

1 See Meyer and Rowan (Citation1977), DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) as well as more recently Boxenbaum and Jonsson (Citation2008) on institutional isomorphism in organizations. Denney (Citation2014), Gizelis and Joseph (Citation2016) and Lipson (Citation2007), amongst others, apply the heuristic of organizational fields to the study of external governance provision in areas of limited statehood.

2 On the concept of different legitimacy audiences in general see Zaum (Citation2013, Citation2016).

3 See also Andrews (Citation2009), Breul (Citation2005) and Denney (Citation2014), amongst others.

4 Critical junctures are events that emerge from contingency, bringing about new institutional formations, in which choices ‘are constrained by past trajectories’ (Schlöndorf Citation2011, 65). The direct quotations given in this text are translations of the authors from the original German to English.

5 On the core tenets of liberal peacebuilding, see Campbell, Chandler, and Sabaratnam (Citation2011); Newman, Paris, and Richmond (Citation2009) and Brozus, Jetzlsperger, and Walter-Drop (Citation2018).

6 A comparison of data in UNICEF (Citation2003) and MRD and CSO (Citation2007) shows increasing literacy rates between 2003 and 2005 for girls in all (Badakshan 10.8/22, Baghlan 10.7/12, Balkh 11.8/32 Kunduz 15.2/24, Takhar 5.8/10) and for the total population in four of five Northern provinces (Badakhshan 20.2/31, Baghlan 24.2/21, Balkh 26.8/44, Kunduz 24.1/33, Takhar 15.3/16).

7 PRTs had been set up as early as 2002 as integrated, ISAF-led military-civilian units, to deliver visible infrastructure and development outputs in unstable areas.

8 See Barakat, Evans, and Zyck (Citation2012) for a nuanced discussion of the merits and pitfalls of NSP-induced turn to local government as well as Nijat et al. (Citation2016) on CDCs more generally.

9 UNAMA provides the following numbers of civilian casualties (deaths and injuries) for North East Afghanistan. 2009, 262; 2010, 479; 2011, 606; 2012, 376; 2013, 573 (UNAMA Citation2016, 14).

10 Two funds had a regional focus as well as a relatively narrow implementation focus. These were the Regional Capacity Development Fund (RCDF), which was funded with €46 million, and the Regional Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF), which was funded with €47 million.

11 This is an abbreviated summary of the vast shura complex, to which stabilization governance was delegated. CDCs at the village level belong to Cluster Level Development Councils (CLDCs) whose leadership (three men and one woman) is elected by delegates from member CDCs. Members of leadership also belong – qua officio – to the District Development Assembly (DDA), which is the responsibly body to submit proposals to the Provincial Development Councils.

12 According to surveys conducted by the Asia Foundation (Citation2009, Citation2012) in North-East Afghanistan, 66 percent of respondents thought that state courts follow the local norms and values of the people in 2012 as opposed to 51 percent in 2009. The same margin holds for assessments of effectiveness of state courts, emphasizing the hypothesized link between social values and goals and instrumental legitimacy-beliefs (see Schmelzle and Stollenwerk Citation2018).

13 While in 2009, 29 percent of North-Eastern respondents rated the security situation in their area as very good, this number stood at percent in 2012 (Asia Foundation Citation2009, Citation2012).

14 See the recent contribution by Coleman (Citation2017) to this journal, whose in-depth analysis of intervening actors in Afghanistan in 2001 explains coalition-building by different legitimacy considerations given incongruent audiences.

References

- Andrews, Matthew. 2009. Isomorphism and the Limits to African Public Financial Management Reform: HKS Faculty Research. Working Paper Series RWP09-2012. Harvard: John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

- Arndt, Friedrich, and Anna Richter. 2009. “Steuerung durch diskursive Praktiken.” In Weiche Steuerung, edited by Gerhard Göhler, Ulrike Höppner, and Sybille De La Rosa, 27–73. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Asia Foundation. 2009. Afghanistan in 2009. A Survey of the Afghan People. Kabul: The Asia Foundation.

- Asia Foundation. 2012. Afghanistan in 2012. A Survey of the Afghan People. Kabul: The Asia Foundation.

- Barakat, Sultan, Mark Evans, and Steven A. Zyck. 2012. “Karzai’s Curse – Legitimacy as Stability in Afghanistan and Other Post-Conflict Environments.” Policy Studies 33 (5): 439–454.

- Bendix, Daniel, and Ruth Stanley. 2008. “Deconstructing Local Ownership of Security Sector Reform: A Review of the Literature.” African Security Review 17 (2): 93–104.

- Böhnke, Jan R., Jan Köhler, and Christoph M. Zürcher. 2017. “State Formation as It Happens: Insights from a Repeated Cross-sectional Study in Afghanistan, 2007–2015.” Conflict, Security & Development 17: 91–116.

- Börzel, Tanja, and Thomas Risse. 2016. “Dysfunctional State Institutions, Trust, and Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Regulation and Governance 10 (2): 149–160.

- Börzel, Tanja, and Vera van Hüllen. 2014. “State-Building and the European Union’s Fight Against Corruption in the Southern Caucasus: Why Legitimacy Matters.” Governance 27 (4): 613–634.

- Boxenbaum, Eva, and Stefan Jonsson. 2008. “Isomorphism, Diffusion and Decoupling.” In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, edited by Royson Greenwood, Christina Oliver, Roy Suddaby and Kerstin Shalin, 78–98. London: SAGE.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2001a. Antrag der Bundesregierung. Einsatz bewaffneter deutscher Streitkräfte bei der Unterstützung der gemeinsamen Reaktion auf terroristische Angriffe gegen die USA auf Grundlage des Artikels 51 der Satzung der Vereinten Nationen und des Artikels 5 des Nordatlantikvertrags sowie der Resolution 1368 (2001) und 1373 (2001) des Sicherheitsrats der Vereinten Nationen. Drucksache 14/7296. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2001b. Antrag der Bundesregierung. Beteiligung bewaffneter deutscher Streitkräfte an dem Einsatz einer Internationalen Sicherheitsunterstützungstruppe in Afghanistan auf Grundlage der Resolutionen 1386 (2001), 1383 (2001) und 1378 (2001) des Sicherheitsrats der Vereinten Nationen. Drucksache 14/7930. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2002. Fortsetzung des Einsatzes bewaffneter deutscher Streitkräfte bei der Unterstützung der gemeinsamen Reaktion auf terroristische Angriffe gegen die USA auf Grundlage des Artikels 51 der Satzung der Vereinten Nationen und des Artikels 5 des Nordatlantikvertrags sowie der Resolutionen 1368 (2001) und 1373 (2001) des Sicherheitsrats der Vereinten Nationen. Drucksache 15/37. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2003. Fortsetzung und Erweiterung der Beteiligung bewaffneter deutscher Streitkräfte an dem Einsatz einer Internationalen Sicherheitsunterstützungstruppe in Afghanistan auf Grundlage der Resolutionen 1386 (2001) vom 20. Dezember 2001, 1413 (2002) vom 23. Mai 2002, 1444 (2002) vom 27. November 2002 und 1510 (2003) vom 13. Oktober 2003 des Sicherheitsrats der Vereinten Nationen. Drucksache 15/1700. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2004. Fortsetzung des Einsatzes bewaffneter deutscher Streitkräfte bei der Unterstützung der gemeinsamen Reaktion auf terroristische Angriffe gegen die USA auf Grundlage des Artikels 51 der Satzung der Vereinten Nationen und des Artikels 5 des Nordatlantikvertrags sowie der Resolutionen 1368 (2001) und 1373 (2001) des Sicherheitsrats der Vereinten Nationen. Drucksache 15/4032. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2006a. Fortsetzung des Einsatzes bewaffneter deutscher Streitkräfte bei der Unterstützung der gemeinsamen Reaktion auf terroristische Angriffe gegen die USA auf Grundlage des Artikels 51 der Satzung der Vereinten Nationen und des Artikels 5 des Nordatlantikvertrags sowie der Resolutionen 1368 (2001) und 1373 (2001) des Sicherheitsrats der Vereinten Nationen. Drucksache 16/3150. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2006b. Fortsetzung der Beteiligung bewaffneter deutscher Streitkräfte an dem Einsatz der Internationalen Sicherheitsunterstützungstruppe in Afghanistan unter Führung der NATO auf Grundlage der Resolutionen 1386 (2001) vom 20. Dezember 2001, 1413 (2002) vom 23. Mai 2002, 1444 (2002) vom 27. November 2002, 1510 (2003) vom 13. Oktober 2003, 1563 (2004) vom 17. September 2004, 1623 (2005) vom 13. September 2005 und 1707 (2006) vom 12. September 2006 des Sicherheitsrates der Vereinten Nationen. Drucksache 16/2573. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2006c. Polizeihilfe für Afghanistan. Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Birgit Homburger, Dr. Max Stadler, Jens Ackermann, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der FDP. Drucksache 16/871. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2006d. Das Afghanistan-Konzept der Bundesregierung. Berlin: Bundesregierung.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2007. Das Afghanistan-Konzept der Bundesregierung. Berlin: Bundesregierung.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2008. Das Afghanistan-Konzept der Bundesregierung. Berlin: Bundesregierung.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2010. Fortschrittsbericht Afghanistan zur Unterrichtung des Deutschen Bundestags. Berlin: Bundesregierung.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2011. Fortschrittsbericht Afghanistan zur Unterrichtung des Deutschen Bundestags. Berlin: Bundesregierung.

- BReg (Bundesregierung). 2014. Fortschrittsbericht Afghanistan zur Unterrichtung des Deutschen Bundestags. Berlin: Bundesregierung.

- Breul, Rainer. 2005. “Organizational Learning in International Organizations. The Case of UN Peace Operations.” (M.A. thesis). University of Konstanz.

- Brozus, Lars, Christian Jetzlsperger, and Gregor Walter-Drop. 2018. “Policy Implications.” In Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja Börzel and Anke Draude, 584–604. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, Suzanna, David Chandler, and Meera Sabaratnam, eds. 2011. A Liberal Peace? The Problems and Practices of Peacebuilding. London: Zed Books.

- Ciorciari, John D., and Stephen D. Krasner 2018. “Contracting Out, Legitimacy and State Building.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 484–505.

- Coleman, Katharina. 2017. “The Legitimacy Audience Shapes the Coalition: Lessons from Afghanistan, 2001.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 11 (3): 339–358.

- Denney, Lisa. 2014. Justice and Security Reform. Development Agencies and Informal Institutions in Sierra Leone. London: Routledge.

- Department for International Development. 2016. Building Stability Framework. London: Department for International Development.

- DiMaggio, Paul J, and Walter Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48 (2): 147–160.

- Draude, Anke, Cord Schmelzle, and Thomas Risse. 2012. “Grundbegriffe der Governanceforschung.” SFB Governance Working Paper Series 36: 3–30.

- Gilley, Bruce. 2009. The Right to Rule: How States Win and Lose Legitimacy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Gizelis, Theodora-Ismene, and Jonathan Joseph. 2016. “Decoupling Local Ownership? The Lost Opportunities for Grassroots Women’s Involvement in Liberian Peacebuilding.” Cooperation and Conflict 51 (5): 539–556.

- IDPS (International Dialogue on Peacebuilding and Statebuilding). 2011. A New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States. Busan: IDPS.

- Ismail, Abdirashid. 2016. “The Political Economy of State Failure: A Social Contract Approach.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 10 (4): 513–529.

- Krasner, Steven, and Thomas Risse. 2014. “External Actors, State-Building, and Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood: Introduction.” Governance 27 (4): 545–567.

- Lemay-Hébert, Nicolas. 2009. “Statebuilding without Nation-Building? Legitimacy, State Failure and the Limits of the Institutionalist Approach.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 3 (1): 21–45.

- Levi, Margaret, Audrey Sacks, and Tom R. Tyler. 2009. “Conceptualizing Legitimacy, Measuring Legitimating Beliefs.” American Behavioral Scientist 53 (3): 354–375.

- Lipson, Michael. 2007. “Peacekeeping: Organized Hypocrisy?” European Journal of International Relations 13 (1): 5–34.

- Mac Ginty, Roger, and Oliver P. Richmond. 2013. “The Local Turn in Peace Building: A Critical Agenda for Peace.” Third World Quarterly 34 (5): 763–783.

- McLoughlin, Claire. 2018. “When the Virtuous Circle Unravels: Unfair Service Provision and State De-Legitimation in Divided Societies.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 527–544.

- Meyer, John W., and Brian Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–363.

- MRD and CSO (Ministry of Rehabilitation and Development and Central Statistics Office). “The National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment 2005. Kabul.” CSO. Accessed August 2, 2017. http://cso.gov.af/en/page/1500/1494/nrav-report.

- Newman, Edward, Roland Paris, and Oliver P. Richmond. 2009. New Perspectives on Liberal Peacebuilding. New York: United Nations University.

- Nijat, Aarya, Kristóf Gosztonyi, Basir Feda, and Jan Köhler. 2016. Sub-National Governance in Afghanistan: The State of Affairs and the Future of District and Village Representation. Kabul: Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU).

- OECD. 2005. The Accra Agenda for Action. Paris: OECD. Accessed August 2, 2017. http://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/parisdeclarationandaccraagendaforaction.htm.

- OECD. 2008. The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. Paris: OECD. Accessed August 2, 2017. http://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/parisdeclarationandaccraagendaforaction.htm.

- Pritchett, Lant, and Frauke de Weijer. 2010. Fragile States: Stuck in a Capability Trap. World Development Report 2011 Background Paper. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Reich, Hannah. 2006. ‘Local Ownership’ in Conflict Transformation Projects. Partnership, Participation or Patronage? Berghof Occasional Paper No. 27. Berlin: Berghof Research Center for Constructive Conflict Management.

- Richmond, Oliver P. 2013. “Failed Statebuilding Versus Peace Formation.” Cooperation and Conflict 48 (3): 378–400.

- Risse, Thomas. 2011. Governance without a State? Policies and Politics in Areas of Limited Statehood. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Scharpf, Fritz. 1999. Governing in Europe. Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schlöndorf, Elisabeth. 2011. Against the Odds. Successful UN Peace Operations – A Theoretical Argument and Two Cases. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Schmelzle, Cord. 2011. “Evaluating Governance: Effectiveness and Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” SFB-Governance Working Paper Series 26: 3–22.

- Schmelzle, Cord, and Eric Stollenwerk. 2018. “Virtuous or Vicious Circle? Governance Effectiveness and Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 449–467.

- Schröder, Ursula, Fairlie Chappuis, and Deniz Kocak. 2014. “Security Sector Reform and the Emergence of Hybrid Security Governance.” International Peacekeeping 21 (2): 214–230.

- Scott, Richard. 1994. “Institutions and Organizations. Toward a Theoretical Synthesis.” In Institutional Environments and Organizations. Structural Complexity and Individualism, edited by Richard Scott, and John W. Meyer, 55–80. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Stabilisation Unit. 2014. The UK Government’s Approach to Stabilisation. London: Stabilisation Unit.

- Stollenwerk, Eric. 2018. “Securing Legitimacy? Perceptions of Security and ISAF’s Legitimacy in Northeast Afghanistan.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 506–526.

- UNAMA, United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan. 2016. Afghanistan. Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict. Annual Report 2016. Kabul: United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan.

- UNICEF. 2003. Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. Kabul: UNICEF.

- von Billerbeck, Sarah. 2015. “Local Ownership and UN Peacebuilding: Discourse Versus Operationalization.” Global Governance 21 (2): 299–315.

- von Billerbeck, Sarah. 2017. Whose Peace? Local Ownership and United Nations Peacekeeping. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- von Billerbeck, Sarah, and Birte Julia Gippert. 2017. “Legitimacy in Conflict: Concepts, Practices, Challenges.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 11 (3): 273–285.

- Westendorf, Jasmine-Kim. 2018. “Challenges of Local Ownership: Understanding the Outcomes of the International Community’s ‘Light Footprint’ Approach to the Nepal Peace Process.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (2): 228–252.

- Winters, Matthew, Simone Dietrich, and Minhaj Mahmud. 2018. “Aiding the Virtuous Circle? International Development Assistance and Citizen Confidence in Government in Bangladesh.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12 (4): 468–483.

- World Bank. 2011. World Development Report. Conflict, Security and Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Zaum, Dominik, ed. 2013. Legitimating International Organizations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zaum, Dominik. 2016. “Legitimacy.” In The Oxford Handbook of International Organizations, edited by Jacob Katz, Ian Hurd, and Ian Johnstone. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1107–1125.