ABSTRACT

This article provides a critical investigation of the edtech startup sector. Edtech startups are companies that are in the first stages of their operation and that seek to provide a newly developed edtech product or service to the education sector. To date, there is hardly any critical research present that seeks to disentangle what the characteristics and modes of operation of this sector are precisely. Through ethnographic research of an edtech startup summit, and by making use of a conceptual framework inspired by the field of valuation studies, the present article seeks to address that gap. Our analysis shows four interrelated constellations of valuations, namely valuations around temporality; expertise; reach; and pedagogical ideas. As we show, each constellation is characterized by various internal tensions, in which edtech startups (and startup investors) need to operate and (constantly re)maneuver themselves. This not only supports an empirical understanding of the edtech startup sector shaped by considerable complexities, contextualities, and ambiguities; it equally provides an analytical framework for nuancing contemporary edtech critique and future analysis of edtech practices.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, there have been substantial evolutions in the education technology (edtech) industry; a sector involved with the (largely for-profit) provision of digital products and services to education. This edtech sector is growing fast and has particularly boomed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (Cone et al., Citation2022). Many established companies (either from education or from other sectors) have, since then, integrated edtech into their portfolio, while there has equally been a fast-rising number of startups in the field (HolonIQ, Citation2024; see also Komljenovic, Citation2021). Even though declining investments in the edtech sector are emblematic of an unstable market that is cooling down in a post-pandemic context, as of January 2024, there are presently 13 Edtech unicorns; that is, private Edtech startups that are valued over $1 billion priced via venture capital funding rounds (HolonIQ, Citation2024).

While education research has, already for many years, investigated the edtech industry, its growing power, global scale, and ambivalent effects on public education, the majority of critical attention has, at least so far, been devoted to analyzing big tech companies such as Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, or Pearson, and their neoliberal logics of commodification (e.g. Hogan et al., Citation2016; Kerssens & van Dijck, Citation2021; Lewis, Citation2022; Peruzzo et al., Citation2022). It is only very recently that critical scholarship has started to engage more systematically with the actual manifoldness and diversity of the edtech field as it manifests differently in different contexts (Decuypere, Citation2021; Gallagher & Knox, Citation2019; Ramiel, Citation2021). This research has started to show and map a wide range of novel forms of professions and professionalities that are emerging in this sector, such as ‘brokers’, ‘accelerators’, ‘enablers’, ‘incubators’, ‘consultants’, or ‘meta-organizations’ seeking to represent the interest of edtech firms (e.g. Hartong, Citation2024; Nivanaho et al., Citation2023; Ortegón et al., Citation2024). However, in these endeavors, critical research has thus far largely ignored the specificities of the edtech startup sector as a field of study in its own right (but see Williamson & Komljenovic, Citation2023). With the study presented here, we contribute to closing that gap. Indeed, the edtech startup sector comes with very particular characteristics that call for closer investigation. One of the general characteristics of startups, is the central role of uncertainty when founding one, since a startup’s trajectory and growth is far from always successful (Alexy et al., Citation2012). In that sense, one of the prime concerns of startups is their orientation towards the future, be it related to the survival of the business, the initial creation of products or business models (which are, in many cases, unfinished or underdeveloped), or the high dependence on investors and, particularly, on venture capital investments (Williamson & Komljenovic, Citation2023; for the general startup sector: Birch, Citation2023). A specific characteristic of the edtech startup sector is the high presence of teachers in the field , who are often driven by a pedagogical interest to improve the quality of existent edtech products (e.g. EdTech Verband, Citation2023). At the same time, however, research equally indicates that there are substantial gaps between logics or needs of startups and those of educators, resulting in calls for more systematic collaboration (Hughes, Citation2019). Finally, state agencies and the considerable amounts of bureaucratic regulations characterizing public education, have in many countries a considerable impact on what startups can(not) do – for instance related to the procurement of specific edtech products by schools – and the strategies they consequently need to develop to secure their survival (e.g. Morrison et al., Citation2014).

In this article, we further disentangle these specific characteristics of the edtech startup sector and aim to develop a more nuanced understanding of what this sector is and how it operates. We hereby employ a conceptual framework stemming from the field of valuation studies (Birch & Muniesa, Citation2020), with a dedicated focus on local contextualities of edtech (Decuypere, Citation2021). The framework offers a lens to analyze the edtech startup sector not as a uniform and monolithic field, but rather as consisting of specific constellations of valuation; that is, as situated practices that are distinctively characterizable by how they qualify, develop, and judge, actors (e.g. startup companies), infrastructures (e.g. the ecosystem in which they are embedded), and even institutions (e.g. the educational sector) to be ‘of value’ (Waibel et al., Citation2021). Thus, we argue that a valuation lens allows to empirically disentangle how edtech startups (get to) see themselves, others, and their products, and which rationales are adopted to make them considered as being valuable (Helgesson & Muniesa, Citation2013).

Empirically, we present the results of an ethnographic study of a three-day edtech startup summit, located in Germany, but including edtech startups from all over Europe (and beyond). In doing so, our focus was put on the local contextualities of the European edtech sector, which is a sector that is in great flux and processes of transformation, and which is seeking to establish and network itself as/into an interconnected ecosystem (Förschler & Decuypere, Citation2024; Hartong, Citation2024). Our analysis shows a complex interrelation of different constellations of valuation in that sector, of which four were found to be particularly dominant: valuation constellations around temporality; expertise; reach; and pedagogical ideas. As we show, all four constellations are characterized by various internal tensions, in which startups (and startup investors) need to operate and (constantly re)maneuver themselves. This not only offers an empirical understanding of the edtech startup sector shaped by considerable complexities and ambiguities; it equally provides a framework for nuancing contemporary edtech critique and future analysis of concrete edtech practices.

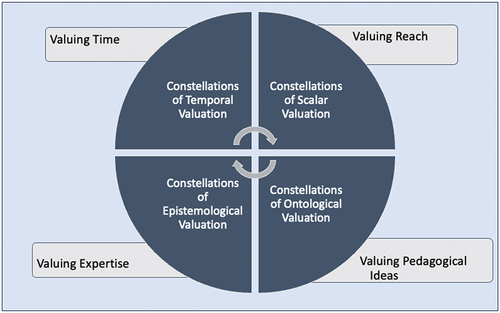

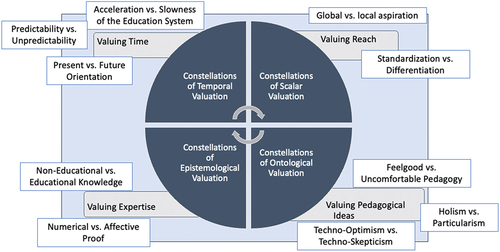

Valuation constellations as practices of governance

As Doganova et al. (Citation2018) argue, value naturally plays a central role in many contexts and aspects of education and has, consequently, been amply studied by educational research. At the same time, analyzing educational practices from the specific vantage point of valuation studies is much more scarce in critical education studies, and specifically in those dealing with edtech (ibid.; but see Williamson, Citation2021b; Williamson & Komljenovic, Citation2023 for notable exceptions). Originating from the broader field of sociology of (e)valuation, valuation studies are dealing with valuation as it happens ‘not inside the mind of an individual (…) but in practices and experiences, in what people spend their time doing, through latent or explicit dialogues with specific or generalized others’ (Lamont, Citation2012, p. 205; Helgesson & Muniesa, Citation2013). In doing so, valuation studies move beyond the idea of value as being fixed; that is, as ‘something that something or someone just has’ (Doganova et al., Citation2018, p. 84). Rather, they approach ‘value as operation, as practice, as act, as translation, as process, as movement’ (ibid.). Valuation studies, consequently, investigate the ways in which things come to be valued, and how they, when being introduced as valuable to social practices, affect and transform these practices. In this article, we conceptualize such practices as constellations of valuation, which simultaneously form, as we argue, powerful practices of governance. More specifically, we hereby distinguish between four such constellations of valuation as shaping and delineating the intricacies, complexities, and specificities of the edtech startup sector. As we show below, these four constellations resonate with existing research in the field of critical edtech studies, even though most studies in this field typically investigate these constellations more separately (rather than in an integrated manner). In contrast, we argue that the framework of valuation constellations offers such an integrated perspective (cf. ).

A first constellation of valuations is focused on distinct ways of temporal governance; that is to say, on ways to make time ‘of value’ in a specific social practice. Especially in the startup sector, which is largely fueled by future uncertainties and venture capital investments that aim to forecast potential future value, time is evidently of crucial concern (Birch, Citation2023). Put differently, ‘temporality and its corollaries – that is, notions of “present” and “future”, but also “risk”, “uncertainty”, and even “value” and “value creation” – [need to be considered] as discursive elements operating within […] imagination and, ultimately, as components of a political technology which determines where money should go and what things should be’ (Muniesa & Doganova, Citation2020, pp. 109–110). Robertson (Citation2022) specifies such ways of governing (through) time as forms of anticipatory governance, where anticipation (e.g. of future value) is considered as an ‘orientation in the present to the future’ and whereby a startup’s future actions and possibilities are calculated and acted upon in the here and now (p.188 – see equally Decuypere & Simons, Citation2020; Williamson, Citation2018).

A second constellation of valuations is centered around practices of epistemic governance; that is, practices that valuate which sorts of knowledge and expertise are deemed to be worthwhile (Lund et al., Citation2022). Epistemic governance thus entails the ways in which knowledge and expertise are being made and valued, and how such knowledge and expertise subsequently circulate and (de-)legitimate specific educational practices. For instance, edtech investors seek to actively construct themselves as being ‘knowledgeable experts’ that are authoritative voices with the necessary expertise to shape the future of education (Komljenovic et al., Citation2023).

A third constellation of valuations that is very specific for the edtech startup sector, has to do with the creation and governance of reach, conceptualized here as scalar governance. When investors valuate a particular edtech company with a certain worth, this is not only a matter of anticipating its future worth or delineating valuable sorts of expertise. It is equally a matter of judging how far (and fast) a company can expand (Hughes, Citation2019). This, as such, is a matter of reach, and of the extent to which a company is capable of growing and of drawing in other actors (e.g. attracting customers - Förschler & Decuypere, Citation2024).

A fourth and last constellation of valuations has to do with the specific sorts of education that are deemed to be of value, and which not. This constellation focuses on the valuations that actors in the edtech startup perform with regards to what constitutes good education, which sorts of learning startups can effectively promote, and so on. We conceptualize such constellations of valuation as ontological governance, which we understand here, after Shahjahan (Citation2016, p. 702), as a way of governance that is centered around defining what (the essence of) good education should be.

Framing the study: an ethnography of an edtech startup summit

To empirically investigate these four constellations of valuation, we conducted an ethnographic study of an edtech startup summit that took place in Germany in 2022, resulting in both wide-ranging and in-depth data. The summit targeted edtech startups from the European context, aiming at providing a space to gain knowledge, to learn from successful companies, to take part in training sessions, to network and build alliances, and to recruit investors. With this specific focus, the summit clearly differs from so-called edtech fairs that have been researched more frequently in the education field and that primarily serve as marketplaces for edtech corporations to recruit end customers (e.g. Gulson & Witzenberger, Citation2022; Player-Koro et al., Citation2022). Rather than focusing on such end costumers, the summit deliberately addressed edtech newcomers who were still in the beginning stage of developing or launching products, who were searching market access, or who were facing problems of survival in a highly competitive sector.

The event was hosted by an organization that promotes itself as being an edtech startup consultant, accelerator, and mediator between startups, investors, marketing partners, and experts from the education field. During the three-day event, various event formats (e.g. workshop pavilions, stages, master classes, networking pub crawls, and investor exhibitions) took place, including more than 1,000 participants and 150 speakers, complemented by refreshment spaces and food courts for more informal gatherings throughout the event. An event app further facilitated participants’ networking, since every attendee could create a profile, declare specific interests, and communicate with others through direct messaging.

The authors of this article followed the edtech startup summit as a teamFootnote1 and created ethnographic data via fieldnotes in paper notebooks, digital voice memos, and photographs. Our analysis draws on these various forms of data, but in order to safeguard anonymity no pictures will be provided in the present article. In addition, we conducted 15 interviews with startup founders (either physically on site or virtually after the event took place), and one interview with the main organizers some weeks before the event. All audio material was transcribed and anonymized. Finally, we analyzed the event’s homepage, participant app, social networks, as well as media coverage of the summit. Thus, our material consisted of a variety of discursive (e.g. stories; rhetorical constructs such as ‘unicorns’ and ‘ecosystems’) and material (e.g. diagrams; tables; artefacts) elements (Birch, Citation2023; Gulson & Witzenberger, Citation2022; Player-Koro et al., Citation2022). All data (except the notebooks) were integrated into one database. The analysis followed a mix of theoretical and inductive coding, focusing on the discursive construction of value through stories, rhetorical constructs, and sociomaterial artefacts present in the event. As such, the four different constellations of valuations emerged out of the theoretical approach adopted, whilst the specific manifestations of these constellations inductively resulted from the analysis of the data corpus (cf. Ravitch & Carl, Citation2021).Footnote2

Edtech startups maneuvering between and within constellations of valuation

Overall, the analysis shows how strongly the event was shaped by the aforementioned constellations of valuation, which at the same time did not manifest unidirectionally (i.e. pushing startups into one specific direction only). Rather, and as we will show in the following sections, each constellation manifested as manifold tensions within the respective constellations of valuation that we discussed in the theoretical approach – that is, tensions within constellations of temporal, epistemic, scalar, and ontological valuation – and that startups continuously need to maneuver. With tension, we mean here that each constellation of valuation should not be considered as a uniform container, but rather as consisting of a myriad of values and practices of valuation that are often challenging, and sometimes even paradoxically relating towards each other.

Tensions within constellations of temporal valuation

In our analysis, a first tension in the constellation of valuation around time manifested around the requirement of startups to operate at high speed, on the one hand, and the emphasis of acknowledging, and adapting to, the natural slowness of the education sector, on the other hand. The requirement of high speed became apparent to us in multiple contexts throughout the event, and resonates with other initial studies on ‘acceleration’ within the edtech startup sector (e.g. Nivanaho et al., Citation2023). In our study, the need to ‘speed up’ was not only used to refer to the education system as a whole but equally to the edtech startup sector, and this in contrast to more established companies. In other words, it was often argued that edtech startups are in permanent danger of losing innovative ideas to ‘faster’ big edtech companies, which have more financial means and lobbying capacity at their disposal. Ultimately, the key to being able to overtake others was hereby framed as ‘fast learning’. As one speaker put it: ‘[…] the only way to win is to learn faster than the rest’ (fieldnotes Author 1).

This idea of fast learning, and the valuation of those who learn (to adapt and innovate) fastest, is equally clearly visible in the context of surviving different investment stages. In such investment stages, startups need to ‘proof’ their success and have only very limited time to do so in order to secure potential investors:

You need to have proof for various stages that you’re in: proof of value, proof of strategy, proof of market … [were] the different stages. You go from one to the next, and for each phase, you need to have quick results.

As a further exemplification of the value that was attached to high speed, various people could be found at the summit who described themselves as ‘accelerators’ and understood their role as supporting edtech startups primarily in meeting these very challenging timelines and taking away at least some ‘temporal pressure’ from their shoulders (cf. Nivanaho et al., Citation2023). In addition, the specific context of COVID-19 related policies could be found as an additional set of discursive arguments that are in line with this emphasis on acceleration. Here, summit actors frequently mentioned the very small temporal windows of opportunity that emerged in the wake of COVID-19:

[…] suddenly there was money. And it’s hard to say that it’s … It’s about money … but it’s about money. […] I think to be realistic here: it’s a short-term run. So, this will be a few years now that this is a hot topic. And I hope that many actors and many players in this field use this time and money wisely, to build up sustainable things from what we can.

In contrast to this emphasis on acceleration and high speed, our analysis equally shows (even though less dominantly) an emphasis on the ‘natural slowness’ of technology implementation in the education sector, which must be accepted as given, and which requires appropriate strategies for instance, regarding long product cycles, tender procedures, or data security regulations (Interview summit organizer). As mentioned by one of the participants of the summit:

The adoption of innovation, adoption of new tools and technologies in education […] is slow. The challenge is to stay alive, not going bankrupt while going through those sales cycles and finding your first launching customer.

Noteworthy, at some moments of the event, speakers argued that in ‘this kind of game’ it is impossible to become an edtech unicorn; that is to say, that it would be naïve for edtech startups to try to emulate stories about the meteoric success of global tech unicorns (memo Author 2, after a workshop on this topic). This clearly shows the distinctiveness of the public education sector as a very challenging and time-consuming market, to which the valuing of speed and acceleration stands in sharp contrast.

Next to this tension between speed and slowness, a second temporal tension could be identified with regards to present and future. With orientation towards the present, we particularly refer to temporal rhythms through which the educational sector is chronologically structured, and which cannot – as argued by many speakers of the summit – be disrupted (cf. Alhadeff-Jones, Citation2017). For instance, startups were frequently reminded that the daily rhythms of both the school year (seasonality, holidays, grading periods) and the school day (morning/classroom vs. afternoon/care) strongly determine both edtech products and the eventual chances of a startup to survive. In that sense, it is not surprising that some edtech startups explicitly seek to capitalize on the chronological structuring of the school year:

[W]e also organize so-called extracurricular challenges. We get to do that in the summer. Many universities have summer schools, so we have a summer challenge. Then we recruit the students, we recruit the companies, and we guide the students.

Even though startups, thus, must take the temporal chronology of the education sector firmly into account, at the same time, they are equally strongly oriented towards the future, particularly when it comes to investors. In an investor logic, the decision to invest into an edtech startup is primarily based on what the investor assumes will happen in the future, thus anticipating (Birch, Citation2023; Robertson, Citation2022) the future value of a startup after the investment has been made (Birch, Citation2023). In many of the mentoring formats of the summit, startups were taught to think along with this valuation logic when they talk to investors (e.g. to ‘futurize’ their own value as a startup when presenting a ‘pitch deck’). Interestingly, here we equally found quite different understandings of investors’ view on time than in the abovementioned acceleration: startups were reassured that investors are well aware of the specificity and slowness of the sector, and that they ‘are patient’ (fieldnotes Author 1).

A third and last temporal tension could be identified between predictability; that is, the control-oriented management of potential futures, versus unpredictability; that is, understanding innovation as disruptive and deliberately creating something radically different and unpredictable. Valuation of predictability was, for instance, found in different techniques for risk management and accountability that investors have developed to steer their investment decisions. Here, we equally see very clearly that investors understand startups as a potential revenue stream within a bigger investment portfolio:

[I]nvesting in one startup takes approximately 80 days. According to the investor speaking here, you need to always invest in multiple startups in 80 days, because you need to do these very tedious tasks of really getting into the startup, digging into what they do, and so on. His company offers a ‘brilliant solution’: it smoothens this process with IT solutions. IT solutions, and AI working with experts, can offer what he calls ‘scale advantages for investing’.

This desire of investors to be able to predict was, however, often standing in contrast with the actual insecurity towards the future that startups are facing:

Investors always have uncertainty in mind. This is the thing that you, as a startup, are working against. Investors are like shy deer: the moment they feel something suspicious, they’re gone.

This strong emphasis on building trust to enhance predictability from an investors’ point of view, conflicts with the simultaneous expectations of startups to disrupt the education system, and to surprise both customers and investors with radically new and different ideas (see equally Komljenovic et al., Citation2023). Thus, startups are expected to have a profound risk appetite and not to be shy to ‘dare something new’ – either because they truly want to revolutionize the educational system or because they want to be distinguishable from other edtech corporations. At the same time, startups are constantly reminded to gather and quantify proof as the outcome of that risk-taking, and communicate this proof as aligning to the anticipatory temporal rationales of investing (Birch, Citation2023).

Tensions within constellations of epistemic valuation

Just as with the dimension of temporal valuation, we could identify different tensions within the constellation of epistemic valuation; that is, which sorts of knowledge and expertise were deemed to be of value (and which not). A first tension, which was continuously present throughout the summit, is the value of non-educational knowledge – economic, but also juridical, political, or technical – versus knowledge inherent to pedagogical experience and professionality. The most dominant argument we hereby found (little surprisingly perhaps, given the summit’s aims and scope), was that educational startup founders (e.g. teachers) need to acquire other types of knowledge in order to secure their startup’s survival and success. Economic knowledge played the most determinative role here, particularly regarding expertise around running a business. For instance, the organizer of the event gave following example from a meeting they recently had with an emerging edtech startup:

[There] were eight founders, eight co-founders, and they sat with us and were like, ‘We don’t want to build up new hurdles, we want to make it equal and accessible for everyone. So, we want the app or the solution to be really cheap and yeah, or maybe free’. And then [the] […] business consultant ha[s] to say: ‘Well, how are you going to pay your wage, how are you going to pay your rent, your food, your everything? If every one of you has like 60 hours a week as a founder of a tech company, and you’re not getting paid, what’s … how long can you do that? You really need to think about it’. So, this is, I think, a problem that many other startup consultants don’t have: that the founders often don’t want to make money

A similar need for ‘educating’ founders was seen with regards to technical knowledge, oftentimes closely related to enhancing business rationales (for instance, how to use social media to generate a proof of concept), but equally regarding more general understandings of the technological side of edtech. One startup founder referred to both sorts of non-educational expertise as follows:

I had to learn really a lot here. What frontend is, what backend is, what infrastructure is, what does a technical product look like, what is a feature, what is a user experience, what machine learning is, what is the difference between artificial intelligence, machine learning, data sets, et cetera. After years and years, I learned. I had a good experience with other investors. I had sparring partners, so I learned from scratch what digital business is. I did that as intensively as I could. It took me four to five years, and I have the feeling now I know what software is.

In contrast to this explicit valuation of non-educational knowledge in order to make it as an edtech startup, there was equally ongoing appraisal of the unique value of genuinely educational expertise in order to create good edtech products. Interestingly, the positive valuation of educational expertise was hereby often contrasted to the fact that many start-up founders are not in the possession of such expertise:

In the last couple of years, a lot of edtechs grew, especially in the K-12 sector, but not all of them are … didactically valuable. Often, founders come from their own learning experience and don’t have in mind that there are different types of learning, that there are different types of learners as well, and all this stuff. So, this is a development that we’re going through right now, I think … that, yeah, now people have a little bit more an eye on this stuff, like: how is it working, how is the user experience and is it like really on a scientific basis a good product for kids to learn with?

Importantly, both sets of expertise (educational and non-educational) were equally often mentioned together, namely as ‘domain know-how’:

[D]omain know-how means you need to know how the market works, you need to know how people like to study. You need to know how people like to be engaged. You need to know how to motivate people in China, Malaysia, South Africa, Mexico, or wherever. You need to study. You need to find out more about the personas, and this is a mixture of social things, psychological things, cultural behavior, and those things. You need to have this extra know-how in-house.

A second tension within the constellation of epistemic valuation has to do with ideas about proof. With this, we mean that startups are epistemically governed by investors towards valuing very specific forms of knowledge about their product, namely a quite standardized formalization of proof, which differentiates different stages (proof of concept, proof of market, etc.), and which is primarily focused on quantified metrics. For instance, during one master class, edtech startups were instructed how to make use of social media platforms to build rapid and cheap test environments for quick Randomized Control Trials, in order to test users´ reactions to a particular edtech design. Given the very short timeline for generating that proof, the focus thereby is largely on quasi-instantaneous data, generated from click streams, user metrics, and other datafied modes of learning (e.g. multiple choice questions) (see also Williamson, Citation2021a).

Interestingly, it was particularly this orientation towards quasi-instantaneous numerical proof – sometimes also mentioned together with the value of winning prizes and awards – that was equally frequently criticized during the event and contrasted with what could be described as pedagogical rationales of proof. Such pedagogical rationales of proof emphasize that learning impact and progress cannot be properly captured in simple numbers, but require a much more in-depth consideration of individual learning stories, and a scientific basis that builds upon such educational user experiences. In that regard, as far as pedagogical rationales of proof are concerned, startup founders very often narrate personal educational experiences to ‘affectively validate’ the effectiveness of their products (cf. Cone, Citation2023). That is, good edtech is often considered to be of value, because founders have an intrinsic motivation to change the education system for the better and do so based on their own professional experiences in the educational system:

It’s not that I just want to scale, sell my company, and make money, but it’s really about what I want to change because I believe in it, because either I was a teacher and I’ve seen it.

Similarly, the organizer made clear that the edtech startup sector should not be confounded with the culture prevailing in the broader startup sector:

[I]t’s not like these elbow cultures that you have in other startup sectors […], you know, so this is really a difference for me: that there’s a […] different culture amongst the people.

Little surprisingly, such narratives of affect, both regarding educational impact and intrinsic founders´ motivations, were not only discussed as providing an important view on the ‘real value’ of edtech but were equally mentioned as a deliberate governance strategy that edtech startups should employ to attract media attention. Undoubtedly, part of the reason for such affective validation is situated in the fact that many edtech initiatives are challenged by the question how to measure and evaluate their success and effectiveness (Vanbecelaere et al., Citation2023). Still, it was quite surprising to us that many actors on the summit deliberately distanced themselves from only using metrics as proof. The same occurred with regards to what was commonly described as ‘social proof’: evidence that an edtech has social impact in a broader community (e.g. by fostering sustainability or diversity) (see also Salomon, Citation2018). Startups were continuously reminded that investors take such social factors more and more into consideration when deciding upon (and evaluating) an investment decision – even though it was for investors not always clear how to measure and valuate the social impact of a startup exactly, then.

Overall, the constellation of epistemic valuation reveals the uniqueness of the education startup field, in which entrepreneurial mindsets and expertise alone are deemed insufficient, but need to be developed in close conjunction with educational (affective) expertise. These insights differ significantly from other research that has described the edtech sector as being largely driven by ‘rampant edu-capitalism’ (Lund et al., Citation2022, p. 535), monetary concerns, and/or economical expertise (Nivanaho et al., Citation2023).

Tensions within constellations of scalar valuation

The third constellation of valuation contains tensions with respect to reach; that is, with respect to where and how edtech startups are assumed to scale towards. In the broader startup sector, such scalar governance has, at least so far, been mostly associated with accelerated growth, and with aspirations and techniques of ‘scaling up startups quickly to become dominant firms in their market; first as unicorns, then as public corporations’ (Birch, Citation2023, p. 7). However, equally here, our analysis shows a more nuanced picture; that is, it revealed different tensions in valuing scalar practices.

A first tension became visible between global aspirations of edtech startups, on the one hand, and the very localized context of edtech production and anchoring, on the other hand. During the event, startups were frequently encouraged to ‘think global’ (‘You need to have a program that is valid to scale worldwide’, interview Lotus). In fact, such global aspirations formed a dominant narrative in many of the summit’s activities (‘Conquer Germany, Europe, and then the world’, speaker during a pitching competition).

Related to the value of globality is the need to produce edtech products that are (easily) scalable and adaptable in various cultural contexts. Interestingly, this focus on global scalability, which startups were taught to think about right from the start, also led to a sort of geographical ‘edtech mapping’; that is, to an assignment of value difference between different national or linguistic contexts:

Bulgaria is not an ideal place to start an Edtech. While the German market is bigger because you have there around 100 million people speaking German, even this is not big enough compared to the British or to the Anglo-Saxon market where you have 500 million people speaking English, or the Indian market which has 1 billion people.

In other words, here we clearly see how the focus shift towards large scale (with big national markets being the least to aim for) devaluates local contextuality. Indeed, the entire atmosphere of the summit was very much targeting globalism and ‘hypergrowth scalability’ (Komljenovic et al., Citation2023), and the references to unicorns were endless (including the possibility for participants to build their own Lego unicorn, as well as the possibility to ride a gigantic mechanical pink rodeo bull that was dressed up as the mythical figure). This general emphasis on aspiring global scale, however, once more stood in stark contrast with other moments during the event where a key value of successful edtech was seen in its acknowledging of, and key orientation towards, local contexts (including individual customers). In many cases, this argument was framed pragmatically, namely that startups need to be aware that initial steps of market implementation are often characterized by a person-by-person, or school-by-school, approach:

I need ambassadors, I need lecturers who use it, so that I have evidence. Then you can slowly scale up the organization to see if they can buy my tool as a license for the whole university.

Wanting to scale too fast (foremost aspiring and valuing hypergrowth) would, in this view, bear the risk of failure and hence not surviving. At the same time, the value of contextual knowledge in and on itself was equally frequently emphasized. Here, different actors warned not to underestimate the large differences across, or even within, national contexts regarding how education works and how, consequently, edtech must be designed:

In high school, the culture makes a huge difference. In Denmark, for example, social teachers work together in groups. […] In Germany, we have seen it in Bavaria, we have seen it in Baden-Württemberg: teachers don’t work together in groups (Interview Heather).

Hence, the more nuanced this contextual knowledge is, the more likely a new edtech product will be successfully placed in a school, and the better the quality of the product will be – an insight that is clearly resonating with argumentation from the critical edtech study field more broadly (see introduction). Another example of this emphasis on quality development through contextual anchoring, is so-called testbed initiatives that were promoted in different formats during the event. Testbeds seek to bring together startups with local schools and teachers in order to test and give feedback on products, focusing in particular on local ‘fitting’, but equally on developing a mutual understanding between edtech production and pedagogical needs. The tests are supported by researchers who develop evaluation instruments, as such seeking to create synergies between local contexts, edtech startups, and academia (Vanbecelaere et al., Citation2023). Hence, testbeds form a prime example of governing through valuating locality in an environment that is at once seeking to scale up as maximally as possible (hypergrowth).

A second tension with regards to scale is closely related to the former, but shifts the focus more towards a meta-view on how the edtech sector as such is structured, how these structures are valued, and how edtech startups are required to navigate these structures. More specifically, much discussion emerged during the event around attempts to standardize and open up edtech markets to facilitate market access and innovation. Various actors and initiatives were present during the event that work in these directions, the most prominent one being the European Edtech Alliance, but equally various actors whose role is to bring together startups with actors from different regulative contexts or to provide regulative knowledge to startups (this includes the event organizers themselves). Many of these organizations, but equally many other speakers of the event, referred to moments where startup development was considerably hindered by closed governance structures and/or regulative complexity:

[I]n Poland or in Latvia or in Bulgaria, it’s very hard to start and then it’s very hard to grow because they have a lot of locked doors.

In such a view, public governance is commonly devaluated because it clashes with the logics of scalar governance; that is, because it is perceived as hindering reach by blocking standardization or flexibilization (see also Hartong, Citation2024). Consequently, startups were positioned as being very unequally distributed across Europe. It is also this inequality that actors such as the European Edtech Alliance aim to address, pointing to large amounts of untapped market potential. During the event, we learned about various instruments the Alliance has implemented to foster standardization, regulative defragmentation, and enhanced visibility of unused potential. One such instrument is the European Edtech map, which startups were continuously encouraged to sign up for in order to identify each other, build partnerships, and ‘find solutions’ (European Edtech Alliance, Citationn.d.). Another example is the quest for establishing interoperability frameworks that would make data flows across countries easier. The guiding image of such activities is the creation (or expansion) of an edtech ecosystem, where startups could then subsequently ‘plug into’ to extend their reach (Förschler & Decuypere, Citation2024).

Even though a lot less dominant, we also found a partly opposing narrative during the event in terms of scale, namely the importance of startups´ regional positioning. Regarding the summit, there was, for instance, a frequent emphasis on why the federal state in which the event took place is much better equipped to serve the needs of edtech startups and why they should, consequently, found their edtech in that specific state:

[W]e have programs over here for dedicated business sectors, and if you’re doing edtech, don’t move to [a specific German federal state], move to [another specific federal state]. (laughs) So, it’s really like; ‘support the local ecosystem and build something up’ (Interview summit organizer).

In sum, not unlike more well-known examples like Silicon Valley or the recent upsurge of Shenzhen as an urban agglomeration that is emblematic for attracting tech companies, several cities in Europe seek to significantly push themselves in the market and attract edtech startups, as such clearly showcasing the importance of considering the localized geographies of tech production when investigating scalar governance practices in the edtech sector (cf. Zukin, Citation2020).

Tensions within constellations of ontological valuation

The fourth and last constellation of valuation refers to the value assigned to different pedagogical understandings. In other words, such valuations seek to (ontologically) steer and intervene ideas about what education should in essence be about (cf. Shahjahan, Citation2016). As with the previous three valuation constellations, we noticed many tensions in the specific kinds of educational approaches that are valued in the edtech startup sector.

To begin with, we could identify a tension between feelgood versus uncomfortable pedagogy. Largely in line with insights from other educational research (e.g. Knox et al., Citation2020), many rationales that edtech startups reported as guiding them, were related to making education ‘easier’, more fun, and less burdensome, for instance through means of automation and gamification:

We should have platforms that teach the children, maybe with gamification and adaptability, and then the children can sit in front of their screen and learn things according to their level.

Students and the users of the different technologies should love to learn, and it’s always connected to fund the usage of these apps that are promoted and always with learning as a good feeling.

Many speakers during the event emphasized that traditional education is seldomly fun or that learning is hardly ever associated with good feelings and that edtech has the enormous potential to (finally) connect learning with such wellbeing, both for students and for teachers. Here, we clearly see a very particular narration of learning, and an idea of ‘disruption’ or innovation mainly referring to using technology to adapt both the perception of learning, as well as the how (e.g. individual play rather than direct instruction; personal pace rather than collective assignments) and what (e.g. tailored pedagogical rather than collective materials) of learning itself (ibid.; Cone, Citation2023). However, during the event, speakers equally argued for exactly this need not to perceive edtech as only simplifying, but equally as something that requires substantial work from teachers (and students). Indeed, startups often reported facing the problematic dilemma of promoting their products as easy and fun, while actually knowing and readily acknowledging that good edtech usage requires a lot more than just placing products in a class (interview Lantana).

A second tension regarding the valuation of pedagogical ideas can be found between approaches that emphasize holism; that is, approaches that wish to include as many facets of education as possible, and those that promote particularism; that is, those approaches that promote a clear focus on one specific aspect of learning, such as a specific subject (e.g. geography) or skill (e.g. reading). On the one hand, many speakers and founders strongly criticized that many current edtech products barely consider the manifoldness and multidimensionality that characterize education:

The[re are] products in schools that seek to take the teachers out of the equation, because there is such a lack of teachers in Germany, so it’s just putting a computer instead of a teacher. To me, they make no sense, and I don’t think that they are going to make teaching any better. There needs to be a whole concept of quality of education (Interview Heather).

On the other hand, startups were taught that it is important not to be too broad in the focus of their product, but rather to become experts in one niche and to focus on scaling up from there.

Interestingly, it seems to be especially this approach of pedagogical particularism that oftentimes results in making use of very similar techniques, including gamification, learning analytics or the delivery of learning nuggets (a form of ‘bite-sized’ micro learning coming from the corporate context). Noteworthy, we also identified approaches that try to position themselves in between both poles and that seek to bridge, for instance, task formats with what was described as real-life cases:

I started embedding so-called real-life challenges, real cases from companies into the classroom, so students could work on those. Basically, those assignments are consultancy assignments, and so they can put their theory into practice and work with a real-life case with a real contact person at the company.

The third and last tension we wish to highlight here is a tension between techno-optimism versus techno-skepticism, as two different ways of valuing the overall role of technology in education. Strong techno-optimistic vibes were pulsing throughout the event, which is, in the end, what drives many founders to erect a startup:

What I like, is that I can clearly see how digital tools can make the lives of the teachers and the lives of the students less stressful and more satisfying.

However, the field of edtech startups did not only consist of very strong believers in technology and straightforward technological solutions for educational problems but equally of many skeptics in terms of what can be achieved through technology, and where edtech reaches its limits. Various startups were truly reflective about the power of edtech. Equally, many speakers, as well as the organizers themselves, frequently pointed to the importance of understanding edtech not as something replacing analogue classrooms, but rather as enhancing these more traditional forms of education, and that this requires ongoing evaluation and care. Similarly, the key role of human attention and interaction in educational contexts was continuously emphasized. This again showcases that the edtech startup sector is not singularly driven by reductionist images of what is considered good education, and hence the crucial importance of adopting a nuanced empirical gaze when researching the edtech sector critically (Macgilchrist, Citation2021).

Concluding thoughts

The edtech startup sector and the venture capital industry form important topics for critical edtech research, as they are becoming key drivers of educational innovation and governance transformation. The dynamics that underpin venture capital as a mode of valuation of edtech startups hereby produce effects that are both reminiscent of the startup sector as a whole and are at once very educationally specific. In providing a nuanced disentanglement of this ambiguity, this article has contributed to an emerging field of studies that place a focus on constellations of valuation as they are presently playing an increasing role in the educational sector (e.g. Komljenovic, Citation2021; Williamson & Komljenovic, Citation2023). At the same time, we have shown that valuation constellations are no uniform containers, but rather that they manifest through a variety of very specific tensions – manifesting socially, materially, and symbolically – that edtech startups constantly need to maneuver (see for a summary). As these tensions in value constellations, and our analysis altogether, show, the values at work in the edtech startup sector are way more diverse and nuanced than is often, at least so far, assumed in critical edtech research (which tends to portray the sector as largely monetarily driven, mainly characterized by tough competition, and applying a very functional and reductionist idea of education – see above). In contrast, this article has adopted a specific critical stance towards edtech that aims to ‘rais(e) questions and troubl(e) (…) previously held assumptions and convictions, including our assumptions about what work the word “critical” should be doing’ (Macgilchrist, Citation2021, p. 247). Indeed, in observing a newly emerging field and in questioning some of the hype and hyperbole that is characteristic of many edtech related discourse (Chan, Citation2019), but equally in critically describing this field in nuanced and empirical manners (Macgilchrist, Citation2021), this study has unearthed a sector that is characterized by a lot of precarity, that consists of companies that often need to operate under harsh and fundamentally uncertain conditions, and that are in constant struggle with ‘Big Tech’ firms (and more conventional state agencies) that are threatening to make them obsolete.

The nuances that this article adds to the critical study of edtech call for further research. For instance, our study largely focused on differential constellations of valuation, but this analysis could equally be elaborated by other critical vantage points from the field of valuation studies. One example hereof, is the lens of assetization. As a concept, assetization seeks to describe how products and platforms, but equally people and educational practices, are no longer (only) valued as a commodity, but rather (equally) becoming governed as a (potentially) continuous revenue stream (Birch & Muniesa, Citation2020). Critical edtech research has already pointed to evolutions in the sector that show how teachers, students, schools, and the (higher) education sector are increasingly becoming ‘assetized’ (Komljenovic, Citation2021). Rather than denouncing such evolutions, the present article shows that, in the various valuation constellations identified, the edtech startup sector itself equally seems to become increasingly subject to processes of assetization as instigated by the bigger venture capital industry (even though not every edtech startup is necessarily operating under venture capital conditions and expectations).

Lastly, this article points to many evolutions that are going on in the sector that still need to be better understood, for instance regarding how startups are embedded in a broader emerging professional field consisting of brokers, accelerators, incubators, meta-organizations, and so on (Ortegón et al., Citation2024). Research along those lines should equally inquire deeper into how edtech startups ‘trickle down’ into concrete schools, which processes of school development (e.g. testbeds) are enacted likewise, and ultimately equally take position with regards to what the education field values as (not) desirable in that respect.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mathias Decuypere

Mathias Decuypere is Professor of School Development and governance at the Zurich University of Teacher Education (Switzerland) and affiliated to the Methodology of Education Sciences Research Group at KU Leuven (Belgium).

Sigrid Hartong

Sigrid Hartong is Professor for Sociology (Transformation of Governance in Education and Society) at Helmut Schmidt University Hamburg (Germany).

Nina Brandau

Nina Brandau is PhD Researcher at the Professorship for Sociology (Transformation of Governance in Education and Society) at Helmut Schmidt University Hamburg (Germany).

Lucas Joecks

Lucas Joecks is PhD Researcher at the Professorship for Sociology (Transformation of Governance in Education and Society) at Helmut Schmidt University Hamburg (Germany).

Anja Loft-Akhoondi

Anja Loft-Akhoondi is Researcher at the Professorship for Sociology (Transformation of Governance in Education and Society) at Helmut Schmidt University Hamburg (Germany).

Carlos Ortegón

Carlos Ortegon is PhD Researcher in Qualitative Research at the Methodology of Education Sciences Research Group (KU Leuven, Belgium).

Toon Tierens

Toon Tierens is PhD Researcher in Qualitative Research at the Methodology of Education Sciences Research Group (KU Leuven, Belgium).

Lanze Vanermen

Lanze Vanermen is PhD Researcher in Qualitative Research at the Methodology of Education Sciences Research Group (KU Leuven, Belgium).

Notes

1. A fine-grained analysis and elucidation of the ethnographic methods we employed – and that we designated as hybrid team ethnography – can be found in Decuypere (CitationForthcoming)

2. The research was approved by [SMEC], the ethical committee of [KU LEUVEN], under approval number [G-2022-5567-R5(AMD)].

References

- Alexy, O. T., Block, J. H., Sandner, P., & Ter Wal, A. L. (2012). Social capital of venture capitalists and start-up funding. Small Business Economics, 39(4), 835–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9337-4

- Alhadeff-Jones, M. (2017). Time and the rhythms of emancipatory education: Rethinking the temporal complexity of self and society. Routledge.

- Birch, K. (2023). Reflexive expectations in innovation financing: An analysis of venture capital as a mode of valuation. Social Studies of Science, 53(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127221118372

- Birch, K., & Muniesa, F. (Eds.). (2020). Assetization: Turning things into assets in technoscientific capitalism. MIT press.

- Chan, A. S. (2019). Venture Ed. Recycling hype, fixing futures, and the temporal order of edtech. In J. Vertesi, & D. Ribes (Eds.), DigitalSTS: A Field Guide for Science & Technology Studies, 161–177. Princeton University Press.

- Cone, L. (2023). Subscribing school: Digital platforms, affective attachments, and cruel optimism in a Danish public primary school. Critical Studies in Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2023.2269425

- Cone, L., Brøgger, K., Berghmans, M., Decuypere, M., Förschler, A., Grimaldi, E., & Vanermen, L. (2022). Pandemic acceleration: Covid-19 and the emergency digitalization of European education. European Educational Research Journal, 21(5), 845–868.

- Decuypere, M. (2021). The topologies of data practices: A methodological introduction. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 10(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2021.1.650

- Decuypere, M. (Forthcoming). Tracing the infrastructural unfolding of (edtech) events through hybrid team ethnography.

- Decuypere, M., & Simons, M. (2020). Pasts and futures that keep the possible alive: Reflections on time, space, education and governing. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(6), 640–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1708327

- Doganova, L., Giraudeau, M., Kjellberg, H., Helgesson, C.-F., Lee, F., Mallard, A., Mennicken, A., Muniesa, F., Sjögren, E., & Zuiderent-Jerak, T. (2018). Five years! Have we not had enough of valuation studies by now? Valuation Studies, 5(2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.3384/VS.2001-5992.185285

- EdTech Verband. (2023). Digitale Bildungsangebote 2023/24. https://www.avr-emags.de/emags/Edtech-Verband/Bildungsangebote-23/#0

- European Edtech Alliance. n.d. https://www.edtecheurope.org/european-edtech-map

- Förschler, A., & Decuypere, M. (2024). Where are we heading? Hackathons as a new, relational form of policymaking. Journal of Education Policy, 39(4), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2024.2313199

- Gallagher, M., & Knox, J. (2019). Global technologies, local practices. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(3), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1640741

- Gulson, K. N., & Witzenberger, K. (2022). Repackaging authority: Artificial intelligence, automated governance and education trade shows. Journal of Education Policy, 37(1), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1785552

- Hartong, S. (2024). Governance by intermediarization. Insights into the digital infrastructuring of education in Estonia. Research in Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/00345237241234613

- Helgesson, C. F., & Muniesa, F. (2013). For what it’s worth: An introduction to valuation studies. Valuation Studies, 1(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3384/vs.2001-5992.13111

- Hogan, A., Sellar, S., & Lingard, B. (2016). Commercialising comparison: Pearson puts the TLC in soft capitalism. Journal of Education Policy, 31(3), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2015.1112922

- HolonIQ. (2024). Global EdTech Unicorns. https://www.holoniq.com/edtech-unicorns

- Hughes, J. (2019). Learning across boundaries: Educator and startup involvement in the educational technology innovation ecosystem. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 19(1), 62–96.

- Kerssens, N., & van Dijck, J. (2021). The platformization of primary education in the Netherlands. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(3), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1876725

- Knox, J., Williamson, B., & Bayne, S. (2020). Machine behaviourism: Future visions of ‘learnification’ and ‘datafication’ across humans and digital technologies. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1623251

- Komljenovic, J. (2021). The rise of education rentiers: Digital platforms, digital data and rents. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(3), 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1891422

- Komljenovic, J., Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Davies, H. C. (2023). When public policy ‘fails’ and venture capital ‘saves’ education: Edtech investors as economic and political actors. Globalisation, Societies & Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2023.2272134

- Lamont, M. (2012). Toward a comparative sociology of valuation and evaluation. Annual Review of Sociology, 38(1), 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120022

- Lewis, S. (2022). An apple for teacher (education)? Reconstituting teacher professional learning and expertise via the apple Teacher digital platform. International Journal of Educational Research, 115, 102034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.102034

- Lund, R., Blackmore, J., & Rowlands, J. (2022). Epistemic governance of diverse research practices and knowledge production: An introduction. Critical Studies in Education, 63(5), 535–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2022.2136226

- Macgilchrist, F. (2021). What is ‘critical’ in critical studies of edtech? Three responses. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1958843

- Morrison, J. R, Ross, S. M., Corcoran, R. P., & Reid, A. J. (2014). Fostering Market Efficiency in K-12 Ed-Tech Procurement. https://digitalpromise.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/DPImprovingEdtechPurchasingFullReport.pdf

- Muniesa, F., & Doganova, L. (2020). The time that money requires: Use of the future and critique of the present in financial valuation. Finance and Society, 6(2), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v6i2.5269

- Nivanaho, N., Lempinen, S., & Seppänen, P. (2023). Education as a co-developed commodity in Finland? A rhetorical discourse analysis on business accelerator for EdTech startups. Learning, Media and Technology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2251391

- Ortegón, C., Decuypere, M., & Williamson, B. (2024). Mediating Educational Technologies: Edtech brokering between schools, academia, governance, and industry. Research in Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/00345237241242990

- Peruzzo, F., Ball, S. J., & Grimaldi, E. (2022). Peopling the crowded education state: Heterarchical spaces, Edtech markets and new modes of governing during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research, 114, 102006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.102006

- Player-Koro, C., Jobér, A., & Bergviken Rensfeldt, A. (2022). De-politicised effects with networked governance? An event ethnography study on education trade fairs. Ethnography and Education, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2021.1976661

- Ramiel, H. (2021). Edtech disruption logic and policy work: The case of an Israeli edtech unit. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1737110

- Ravitch, S. M., & Carl, N. M. (2021). Qualitative research: Bridging the conceptual, theoretical, and methodological (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Robertson, S. L. (2022). Guardians of the future: International organisations, anticipatory governance and education. Global Society, 36(2), 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2021.2021151

- Salomon, V. (2018). Strategies of startup evaluation on crowdinvesting platforms: The case of Switzerland. Journal of Innovation Economics and Management, n° 26(2), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.3917/jie.pr1.0029

- Shahjahan, R. A. (2016). International organizations (IOs), epistemic tools of influence, and the colonial geopolitics of knowledge production in higher education policy. Journal of Education Policy, 31(6), 694–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1206623

- Vanbecelaere, S. et al. (2023). Towards Systemic Edtech Testbeds: A Global Perspective. https://docs.opendeved.net/lib/78XN44TG

- Waibel, D., Peetz, T., & Meier, F. (2021). Valuation constellations. Valuation Studies, 8(1), 33–66. https://doi.org/10.3384/VS.2001-5992.2021.8.1.33-66

- Williamson, B. (2018). Silicon startup schools: Technocracy, algorithmic imaginaries and venture philanthropy in corporate education reform. Critical Studies in Education, 59(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1186710

- Williamson, B. (2021a). Digital policy sociology: Software and science in data-intensive precision education. Critical Studies in Education, 62(3), 354–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1691030

- Williamson, B. (2021b). Making markets through digital platforms: Pearson, edu-business, and the (e) valuation of higher education. Critical Studies in Education, 62(1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2020.1737556

- Williamson, B., & Komljenovic, J. (2023). Investing in imagined digital futures: The techno-financial ‘futuring’ of edtech investors in higher education. Critical Studies in Education, 64(3), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2022.2081587

- Zukin, S. (2020). The innovation complex: Cities, tech, and the new economy. Oxford University Press.