?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

A growing body of research links working environment with employee health and well-being. We argue that greater employee well-being is associated with positive work outcomes, benefits likely vital to business performance. We have expanded the literature on this topic by evaluating these questions within a population of factory workers. To date, studies have examined well-being in the workplace in middle- and low-income countries mostly through the lens of disease and disability or have been restricted to human rights, rather than human well-being in general. This paper connects (1) job resources/work conditions and (2) worker well-being with (3) work outcomes in Mexican apparel factories belonging to the apparel supply chain. Our analysis builds on the first wave of the SHINE Worker Well-Being Survey. We examined links between working conditions, job resources, individual well-being and work outcomes using path analysis within a cross-sectional study comprising approximately 2200 Mexican factory workers. We report that job satisfaction and self-assessed work performance are positively and directly associated with worker well-being. We found that job control, trust, respect and recognition were significant correlates of all examined work outcomes (job satisfaction, work engagement and self-assessed work performance), with significant indirect effects on well-being.

Introduction

Global supply chains did not only lead to a transformation of the structure of production and employment relationships but also introduced concerns about the social and environmental conditions in which goods and services are designed, produced and distributed (Barrientos, Gereffi, and Rossi Citation2011; Barrientos, Mayer et al. Citation2011). It is beyond doubt that demand for global production from the labor-intensive industries of emerging economies increased job opportunities, especially for women and migrant workers. It is clear, however, that appropriate terms and conditions for employment and relevant labor regulations did not follow and the safety and welfare of factory personnel is not always assured (Egels-Zandén and Lindholm Citation2015).

Following the reluctance and inability of local governments to address work safety challenges, global brands instigated moves to improve worker welfare in their supply chain (Collingsworth Citation2006; Locke et al. Citation2007; Egels-Zandén and Lindholm Citation2015). Weak rule of law and flawed legal systems provided an additional boost for this initiative to grow internally. Because of repeated multiple fatalities due to deficiencies in safety protocols and working conditions (e.g. Rana Plaza and Tazreen Fashions – Bangladesh), voluntary private regulatory systems, offering basic conditions for safe, healthy, fair and respectful working conditions were often encoded in factory audits to ensure compliance and limit risk (Barrientos, Mayer et al. Citation2011).

In fact, many companies now report their environmental footprints and social impacts in their annual sustainability reports. Thus, they demonstrate, to investors and to the public, their commitment to social responsibility and their company’s values and actions to improve quality of life of (1) their workforce and their dependents and (2) the greater community and society as a whole (Holme and Watts Citation2000). Reporting standards for environmental impacts are generally well defined by governments or non-governmental bodies such as the UN Global Compact and the Global Reporting Initiative. Standards for reporting social impacts of businesses are less clear-cut. Despite growing recognition that multinational corporations exert major influence on worker health and well-being in their supply chains and that improved employee well-being could translate to improvements in human performance and productivity (ILO and IFC Citation2016; World Bank Citation2015), an integrated reporting system that reflects the mutual dependency of employee and business needs is still missing.

This paper presents first findings from the SHINE Worker Well-Being study conducted among over 2,200 workers from three apparel factories in Mexico. This study aims to measure worker well-being with an emphasis on the role of well-being at work (health, recognition, and meaning) in promoting better work outcomes.

More specifically, our current study aims to identify drivers for worker well-being (such as job satisfaction, worker engagement, and self-assessed work performance) among Mexican apparel factory workers and their association with work outcomes, controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, and job-related variables. We hypothesized that job resources and resources in life (which can be provided by employers) contribute to work outcomes and worker well-being, and that the influence of job or life resources on well-being is mediated by work outcomes.

Background

Theoretical model

We employed the job demands-resources (JD-R) model to identify factors influencing worker well-being and work outcomes (Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007; Demerouti and Bakker Citation2011). The JDR model was developed as a modification of the job strain /demand-control-support (JDCS) (Karasek Citation1979; Karasek et al. Citation2007; Brauchli et al. Citation2015) and effort-reward imbalance (ERI) models (Siegrist Citation1996). It is implicit to these three models that employee health and well-being at work originate from a balance between positive and negative job characteristics (i.e. resources vs. demands). While the ERI and JDCS models link precisely defined sets of concepts, the JD-R model is a heuristic, representing a conceptual approach to the influence of job (and in more recent approaches – individual) characteristics on health, well-being, and motivation (Schaufeli and Taris Citation2014). Additionally, the JD-R incorporates numerous possible working conditions, and focuses on both negative and positive indicators of employee well-being and performance. Despite specific risk factors related to job strain, the JD-R model can be applied to a wide range of occupations because it classifies work factors into two general groups: job demands and job resources (Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007; Demerouti and Bakker Citation2011). Both refer to physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job. However, job demands concentrate on efforts and skills required and are thus related to physiological and psychological costs. Job resources include work characteristics that reduce job demands, help people achieve work goals and contribute to personal development. In other words, job demands, which are usually reflected by high work pressure, emotional demands, and role ambiguity, are theoretically believed and empirically shown to cause strain. Job resources, which comprise social support, performance feedback, and job autonomy, are instrumental for motivation (Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007).

Following Demerouti et al. (Citation2001) and Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2007) in their assertion that the job-demand model should be empirical, and thus flexible enough to accommodate the various job characteristics and paths that influence employee health and well-being, we grouped job resources into physical, social, mental (psychological) and organizational categories. Together with job demands and resources in life (i.e. work-family conflict and living conditions incorporated into our model), these resources are believed to influence both workers’ well-being and work outcomes.

Following the rationale of numerous reports underscoring the physical demands of work in apparel factories (ILO and IFC Citation2016), we also incorporated physical resources into our approach. Work in apparel factories typically demands prolonged fixed posture, repetitive movements, and physical hazards, such as improper lighting, heat and cold stress, humidity, poor air quality and circulation, and noise. These factors may significantly influence health, productivity and performance (Parsons Citation2000; Kjellstrom, Holmer, and Lemke Citation2009; Akbari et al. Citation2013; Xiang et al. Citation2014), however there is also some – though considerably limited – evidence that they may not be influential for happiness (Loscocco and Spitze Citation1990) and job satisfaction (Klitzman and Stellman Citation1989).

Social and mental job resources, labeled as psychosocial work factors, have been identified to be occupational risk factors for well-being (De Croon et al. Citation2004; Herr et al. Citation2015) and work performance (Price Citation2001; De Croon et al. Citation2004; Mossholder, Settoon, and Henagan Citation2005; Fuß et al. Citation2008; Young and Corsun Citation2010; Skagert, Dellve, and Ahlborg Citation2012). Extensive literature offers both theoretical and empirical evidence that employees exposed to adverse psychosocial factors (e.g. high work load, conflicting demands, an unsupportive or hostile working environment, work pressure) and to low levels of control (lack of decision-making authority, inflexible time schedules, lack of skill development and skill use) are more likely to report (1) unfavorable performance outcomes (e.g. lower job satisfaction and increased turnover) (Avey, Luthans, and Jensen Citation2009; Bambra et al. Citation2014; Rourke Citation2014; Albrecht et al. Citation2015), and (2) reduced well-being (Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007; Demerouti and Bakker Citation2011). On the other hand, when conceptualized from the positive perspective, support from supervisors and coworkers (Spell, Eby, and Vandenberg Citation2014), organizational support (Eisenberger and Huntington Citation1986; Rhoades and Eisenberger Citation2002; Eisenberger Citation2003) and organizational climate and culture (Zohar and Hofmann Citation2012) were empirically confirmed to protect against negative effects of job burden. However, there are also some reports depicting lack of impact of psycho-social working conditions either on emotional well-being (Loscocco and Spitze Citation1990; Bakker and Sanz-Vergel Citation2013) or on work engagement (Bakker and Sanz-Vergel Citation2013; Upadyaya, Vartiainen, and Salmela-Aro Citation2016).

It is known that organizational job resources contribute to workers’ health while at work. However, this perspective is rarely reflected by job models (e.g. turnover models) that are usually applied to highly skilled employees from developed countries (Holtom et al. Citation2008). Under these circumstances the provision of safe working conditions is more often ensured than it is in the case of less developed countries and their low-skilled work force.

Resources in life

We incorporated resources in life into our conceptual model following earlier findings showing that insufficient and unequal access to clean water, sanitation and health care (CSDH Citation2008; Marmot et al. Citation2008), inadequate nutrition (Pernia and Quibria Citation1999) and lack of work-family balance (Fuß et al. Citation2008; Bambra et al. Citation2014; de Neve, Krekel, and Ward Citation2018) lead to deterioration in health and well-being. Multinational corporations are strongly encouraged to provide sufficient resources in life for their employees, especially those in the supply chains, in order to meet their corporate social responsibility and sustainable development goals for health and well-being (Kolk Citation2016).

Worker well-being

Although well-being in the workplace setting has been thoroughly examined, the notion of overall employee well-being (beyond only while at work) has been established only recently (Zheng et al. Citation2015; Węziak-Białowolska, McNeely, and Vanderweele Citation2019). Further, well-being in the work setting is usually conceptualized through the lens of a single life-related measure, such as mental health/depression (Sanne et al. Citation2005; Stansfeld et al. Citation2012; Bentley et al. Citation2015; Saijo et al. Citation2015; Madsen et al. Citation2017), the life satisfaction–job satisfaction link (Diener and Tay Citation2017; Near and Sorcinelli Citation1986; Rice, Near, and Hunt Citation1980), workplace friendship (Sias and Cahill Citation1998; Morrison and Cooper-Thomas Citation2016), and work motivation and the life cycle (Kets De Vries et al. Citation1984), while disregarding the complex multidimensional links between well-being in the workplace, work outcomes, job resources, job demands and resources in life.

In this study, we apply a comprehensive well-being measure designed to reflect complete human flourishing, namely the Flourish Index (FI) (VanderWeele Citation2017; Węziak-Białowolska, McNeely, and Vanderweele Citation2019). VanderWeele (Citation2017) proposed an approach based on the aggregation of five domains of human life to derive a measure of complete human flourishing. These domains include happiness and life satisfaction, physical and mental health, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, and close social relationships. While life satisfaction/happiness, meaning and purpose, and close social relationships were often included in measures of social well-being, eudaimonic or hedonic happiness (see for example: Ryff and Keyes Citation1995; Ryff Citation1995; Keyes Citation1998; Diener et al. Citation2010; Huppert and So Citation2013; Su, Tay, and Diener Citation2014), health and character and virtue are typically ignored (VanderWeele Citation2017). Psychometric analysis for the FI was conducted on a sample of 5565 working adults, which provided evidence on its validity, reliability and applicability (Węziak-Białowolska, McNeely, and Vanderweele Citation2019).

Work outcomes

Work outcomes include objective performance measures reported by companies as well as self-reported measures. Objective performance measures include, for example, number of days off on a sick-leave, total working hours and decisions to quit. Self-reported measures are often derived from survey responses and reflect, among others, work attitudes such as job satisfaction, work engagement and job involvement. Job involvement and work engagement, despite being similar concepts, are empirically confirmed to be different (Hallberg and Schaufeli Citation2006). Job involvement is the willingness to exert effort on the job and is related to motivation and challenge (Price Citation2001; Hallberg and Schaufeli Citation2006). Work engagement – as measured by the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) – was introduced as a conceptual opposite to job burnout and was conceptualized as a state of well-being, characterized by high levels of energy that are invested in work (Hallberg and Schaufeli Citation2006). It is defined as ‘a persistent, positive affective-motivational state of fulfilment in employees that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption’ (Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter Citation2001, 417).

As reported by Bakker and Demerouti (Citation2007) in their excellent review on the applications of the JD-R model, all these work outcomes have been successfully incorporated in the JD-R model by numerous researchers.

Conceptual research model

In this study, we tested two research hypotheses:

H1 – Job resources and resources in life contribute to both work outcomes and worker well-being;

H2 – The influence of job resources and resources in life on well-being is indirect – mediated by work outcomes.

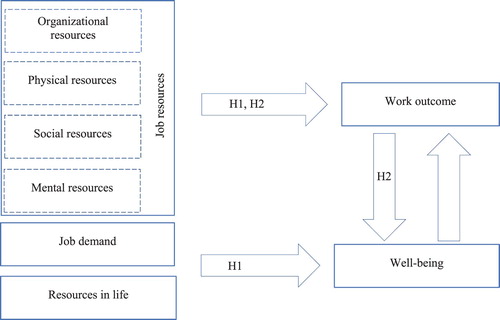

Figure 1. Conceptual model of worker well-being. Note: H1 and H2 refer to the research hypotheses tested.

We hypothesized that an overarching category of job resources along with job demands and resources in life impacts work outcomes and worker well-being. The job resources category comprises four types of job resources: organizational, physical, social and mental. Additionally, reciprocal links between work outcomes and worker well-being are assumed.

Methods

Study design and data source

The analysis builds on the first wave of the SHINE Worker Well-Being Survey (WWBS), which was administered in February 2017. Workers of three Mexican apparel factories who had expressed interest in worker well-being programs were surveyed. Factories selected for the study had been successfully passing external compliance audits with environmental measurement tools designed to examine and measure organizational non-financial performance. These tools have been, however, recently recognized to be insufficiently efficient, flawed or biased mainly due to being based on a ‘check-box compliance’ approach (Short, Toffel, and Huguill Citation2014; Lebaron and Lister Citation2015). Hence, our study provided additional, subjective measures beyond objectively adequate working conditions confirmed by external auditors.

The WWBS is a component of the greater Worker Well-Being study, which also includes a set of monthly business metrics on the economic performance of factories (such as number of units produced, total overtime hours, and production quality), individual employee information related to voluntary turnover, working hours, absenteeism, and work injury, as well as spontaneous qualitative comments collected from workers through suggestion boxes, group discussions and interviews to both validate and complement the survey findings. The purpose of multi-mode data collection is to ensure data quality (Leeuw Citation2005).

During the survey administration, personnel were released from their line positions. One line at a time attended private and enclosed survey stations. Workers’ decisions whether to participate in the survey were not disclosed to management and their survey responses were kept confidential. Each respondent was asked to describe their working conditions, job resources, their own performance and job attitudes, and their health, well-being and living conditions. Additionally, the survey queried about participants’ demographic and socio-economic characteristics.

Aggregated results were shared with both participants and management on separate occasions. As a result of this feedback, factory management undertook several interventions to improve working conditions and the well-being of workers and local communities.

Participants and sample size

In total, 2,278 respondents participated in the WWBS, which accounted for 58.0% of the total eligible workforce (). In the first factory, 975 workers were surveyed (70% of the workforce), in the second, 1,243 (51% of the workforce) and in the third, 46 (46% of the workforce). In the sample, 50.1% of respondents were operators, 11.0% were supervisors, 8.4% were quality auditors, and 7.4% were assistants. Mean respondent age was 32.5 years (SD = 10.4), close to the average age of 32.8 (SD = 10.6) in the overall worker population of the three factories. The proportion of female workers in the sample was 45.9%, compared to 41.1% in the whole population. Of those employed in the factories, 39.6% had worked less than one year (40.2% in the population) and 25.9% had worked more than five years (24.6% in the population). Of the workers surveyed, 33.2% had post-secondary education, college, or vocational training, 44.1% were married, 67.4% had children, and 46.5% were responsible for elder dependents.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (not weighted) of participants in the Worker Well-Being Survey (2017).

For analytical purposes, all the data was weighted with respect to gender, age, and factory to ensure representativeness. Additionally, all individuals with missing values from any well-being, work outcomes, job resources, or control variables for a given path model were excluded from the analysis. A total of 2,052 individuals provided complete data.

Measures

presents the variables included in the analysis. They were grouped into work outcomes, worker well-being, and work-related factors, following the conceptual model presented in .

Table 2. Variables used – questions, scale and psychometric properties.

Control variables

Controls for demographic factors were introduced to each model. These include gender, age (below 25, 25–34, 35–44, 45+), and business-related characteristics, such as factory of origin, job tenure (up to one year, 1–3 years, above 3 years) and work shift (day only, night only, day and night). When evaluating each work outcome, we controlled for gender, age, factory of origin, job tenure and work shift, and we controlled only for gender and age while evaluating the well-being outcome. These variables were proven to be essential predictors of workers’ treatment beyond working conditions (Węziak-Białowolska et al. Citation2017).

Additionally, the analysis took into account workers’ living conditions. The living conditions scale was constructed from a question on income poverty (i.e. worrying about being able to meet monthly living expenses) and three questions reflecting material deprivation with regard to how often participants worried about (1) safety, (2) food, and (3) housing (responses: 0 = never, 1 = occasionally, 2 = often, 3 = all the time). The score was obtained as the average of responses and the scale ranged from 0 to 3. Psychometric properties of the scale in the population of interest were satisfactory (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.858; confirmatory factor analysis model – fit statistics: CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.995, RMSEA = 0.038).

Analytical approach

Satisfactory measurement properties for all scales used in our model were assured by high Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (Bland and Altman Citation1997; Tavakol and Dennick Citation2011) and good fit of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicating high reliability and validity, respectively (Brown Citation2006; Jackson, Gillaspy, and Purc-Stephenson Citation2009; Kline Citation2011).

Subsequently, we ran three path analyses to establish the role of work-related factors for worker well-being and work outcomes (Bielby and Hauser Citation1977; Pearl Citation1998; Kline Citation2011). All models assumed the same set of mediating and control variables. The only difference was the choice of the outcome variable: job satisfaction (model 1), self-assessed work performance (model 2), and work engagement (model 3). Following the recommendations of MacKinnon et al. (Citation2002, Citation2007) and Aguinis, Edwards, and Bradley (Citation2017), we tested the joint significance of the association between independent and the dependent variable (direct effect) and associations between independent variables, the mediator, and the dependent variable (indirect effect). The relationship between work-related factors and well-being/work outcomes was subsequently modeled using three specifications. Each model consisted of two linear equations:(1)

(1)

(2)

(2) Here, subscript i represents an individual, the variable WRF indicates exposure to a set of work-related factors, WB is the well-being indicator, WO is one of the three (k = 1,2,3) work outcomes. X is a vector of control variables (gender and age) and Z is the vector of work-related control variables (gender, age, factory, job tenure and work shift). β1 shows the association between control variables and the well-being outcome, δ1 shows the association between control variables and a work outcome and γ1 and γ3 reflect effects of work-related factors on well-being or a work outcome. γ2 shows the effects of a work outcome on well-being, while γ4 shows the effects of well-being on a work outcome. ηi and εi are disturbance terms. In this specification, work outcomes and well-being outcome are both mediators and outcomes.

To examine direct and indirect effects, we applied the effects decomposition (Kline Citation2011). The significance of indirect and total effects was tested with the bootstrapping method (Aguinis, Edwards, and Bradley Citation2017). To examine a potential effect of mediation, we adopted the strategy suggested by Aguinis, Edwards, and Bradley (Citation2017), namely that the existence of mediation is corroborated when an indirect effect is significant, regardless of the presence or absence of the direct effect.

To evaluate model fit (for both CFA and path analysis), a set of commonly accepted measures was applied, i.e. Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMSR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). For RMSEA and SRMSR, the range of acceptable values is 0.00–0.08 (Browne and Cudeck Citation1992). With respect to CFI and TLI, values are expected to be above 0.9 (or even 0.95).

Following the results of Rhemtulla, Brosseau-Liard, and Savalei (Citation2012) and suggestions of Norman (Citation2010), all variables measured on a response scale of at least 6 points were treated as continuous data. Results are presented as standardized estimates to present the effect sizes. Analyses were performed using Stata 15 and Mplus 8.

Robustness of the results was assured by controlling for common method bias through the design of the study procedure (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003). Although it was not feasible to account for rater bias, common measurement context and time biases (as we needed to obtain data from the same individuals in the same measurement context to test the research hypotheses), measures of predictors, mediators and outcome variables were separated proximally and methodologically. In particular, measures of interest were located in different sections of the questionnaire and different response scales were used, such as 6-point Likert scales, 0–10 rating scales, and intensity scales, along with different scale endpoints and different labels.

Results

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are presented in .

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for the study variables.

All three models proved to be well-fitted ().

Table 4. Fit indices – model 1–3.

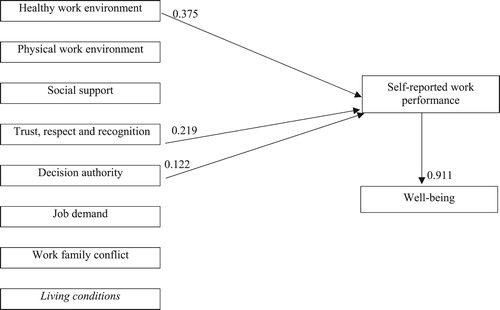

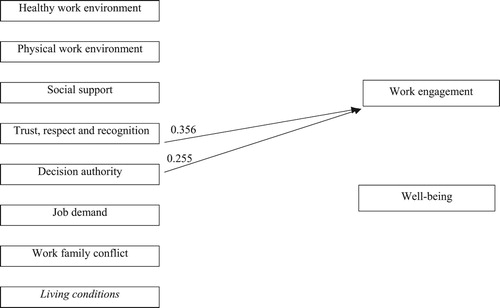

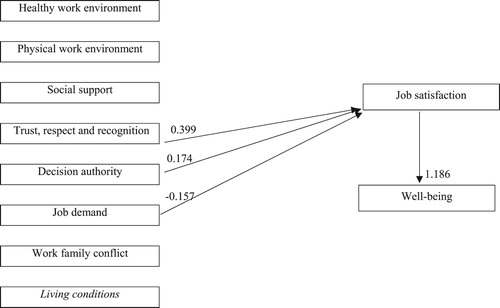

Two work outcomes () – job satisfaction and self-reported performance at work – were significantly and positively correlated with well-being. These correlations were also characterized by considerable effect sizes; however, the association between job satisfaction and well-being was stronger than the link between self-reported work performance and well-being (standardized estimates of 1.186 vs. 0.911, respectively). No evidence of association between work engagement and well-being was found. Direct associations between work-related factors (either physical or psychosocial) and well-being were also not evident.

Table 5 Path analysis – standardized estimates and standard errors in parenthesis.

Work-related factors likely to contribute to workers’ performance were identified:

Trust, respect and recognition were moderately correlated with each of three work outcomes; the lowest effect size (0.219) was noted for self-reported work performance, while the highest (0.399) was observed for job satisfaction;

Job autonomy was associated, though with a rather low effect size, with all three work outcomes; the effect sizes ranged between 0.122 for self-reported work performance and 0.225 for work engagement.

Additionally, we found that two other work-related factors were related to specific work outcomes. A healthy work environment was positively associated with self-reported work performance (moderate effect size of 0.375) and job demand was negatively linked to job satisfaction (small effect size −0.157). All significant paths are presented in –.

Figure 2. Path analysis for self-reported work performance (only significant standardized estimates are presented).

Figure 3. Path analysis for work engagement (only significant standardized estimates are presented).

Figure 4. Path analysis for job satisfaction (only significant standardized estimates are presented).

We did not find any evidence for direct associations between work performance and physical working conditions, social support, work-family conflict, or living conditions. This finding is based on the model in which all work-related factors are modeled simultaneously, under the assumption of their coexistence in a real work environment.

These findings do not preclude an indirect influence from work-related factors on well-being (which could be moderated by work outcomes). Therefore, we also examined indirect effects of work-related factors ().

Table 6. Total indirect effects of work and life resources on well-being – standardized estimates and 95% bootstrap confidence intervals in parentheses.

Our analyses indicated that some work-related factors are likely to contribute indirectly to worker well-being. Significant indirect effects for all work outcomes were found for: (1) a healthy work environment (positive effect), (2) trust, respect and recognition through all performance outcomes (positive effect) and (3) job autonomy (positive effect). The physical work environment, which is negatively oriented (the higher the score, the worse the physical environment), was found to have a detrimental effect on well-being. The impact was, however, mediated by job satisfaction. This implies that changes in the physical work environment may not have direct effects on well-being in life as they may be confined temporarily and spatially to the work environment. However, it is also possible that declining job satisfaction may subsequently translate to reduced overall well-being. Social support (positive impact) and job demand (negative impact) were found to influence well-being through effects on job satisfaction and work engagement. It is an interesting finding pointing to the fact that job-related issues and support required to resolve problems at work do not affect well-being outside of work unless they have a bearing on job satisfaction and work engagement. Work-family conflict (negative impact) and living conditions (positive impact) were found to be influential on well-being through effects on work engagement. Especially for the work-family conflict, one can imply that if a person was not able to keep high engagement in work due to work-family conflict, well-being was likely negatively affected. Consequently, all relations predicted by our initial hypotheses were confirmed.

Discussion

This study sought to reveal the interlink between working conditions, work outcomes and worker well-being among workers in Mexican apparel factories. Our results indicate that job satisfaction and self-reported work performance are positively associated with worker well-being, pointing to a possible direct impact of work outcomes on well-being. This finding is in line with the part-whole theory (Rice, Near, and Hunt Citation1980; Near and Sorcinelli Citation1986) which posits that job satisfaction influences subjective well-being.

We also found that trust, respect and recognition, in addition to job autonomy, were significant contributors to all examined work outcomes (i.e. job satisfaction, work engagement and work quality), with significant indirect effects on well-being. This finding supports the importance of societal or relational well-being (Prilleltensky Citation2005; White Citation2017), known as the caring climate (Fu and Deshpande Citation2014) or organizational climate and culture (Zohar and Hofmann Citation2012) in the field of organizational psychology, for both work performance and worker psychological well-being. It also corroborates the importance of organizational rewards, which is one of the elements of organizational support theory (Eisenberger and Huntington Citation1986; Rhoades and Eisenberger Citation2002; Eisenberger Citation2003), in shaping work performance outcomes.

Organizational resources reflected by healthy working conditions were found to contribute significantly to work quality and indirectly to worker well-being – via job satisfaction, work quality and work engagement. This finding was supported by spontaneous comments provided by workers who complained about very limited access to drinking water and its quality, as well as heat and work load – elements of the organizational resources scale we used – often indicating how these conditions affected their health and well-being.

Consistent with the fact that level of job demand is a source of significant stress (Demerouti and Bakker Citation2011), we found that Mexican workers were susceptible to decreased job satisfaction and lower well-being (indirect effect through job satisfaction and work engagement) due to high workload. These conclusions corroborate both of our research hypotheses.

Our study also revealed that workers experiencing work-family conflict and unfavorable physical working conditions might experience depleted well-being, although the effect is indirect and mediated by effects on either work engagement or job satisfaction. Social support from supervisors and co-workers was also likely to indirectly stimulate well-being through impacts on job satisfaction and work engagement. These indirect effects corroborate the important role of perceptions of developmental support from co-workers and supervisory mentors for the promotion of work engagement (Spell, Eby, and Vandenberg Citation2014).

In contrast to previous findings (Parsons Citation2000; Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007; Fuß et al. Citation2008; Avey, Luthans, and Jensen Citation2009; Kjellstrom, Holmer, and Lemke Citation2009; Demerouti and Bakker Citation2011; Akbari et al. Citation2013; Xiang et al. Citation2014; Bambra et al. Citation2014; Rourke Citation2014; Albrecht et al. Citation2015; de Neve, Krekel, and Ward Citation2018), we did not observe direct impacts from physical working conditions, social support provided by supervisors and colleagues, or work-family conflict on either well-being or work outcomes.

Our findings, while not what we expected, are supported by findings of other scholars. For example, Loscocco and Spitze (Citation1990) reported no association between physical working conditions and happiness among female factory workers. Klitzman and Stellman (Citation1989) found no evidence of associations between workplace lighting conditions and job satisfaction among office workers. Similarly, other studies report null associations between level of job demand and distress and happiness among factory workers (Loscocco and Spitze Citation1990), human well-being (Bakker and Sanz-Vergel Citation2013), and work engagement (Bakker and Sanz-Vergel Citation2013; Upadyaya, Vartiainen, and Salmela-Aro Citation2016). Insignificant association between job autonomy and distress among female factory workers was found by Loscocco and Spitze (Citation1990). These authors also found no significant associations between (1) supervisor support and both distress and happiness (however, only among female factory workers) and (2) satisfaction with co-workers and distress, only among male factory workers. We also note that although negative or counterintuitive findings are not numerous in the literature, this might result from the well-known difficulty and publication bias in communicating and publishing negative results (Dirnagl and Lauritzen Citation2010; Fanelli Citation2012; Matosin et al. Citation2014).

Although, with respect to the above work-related factors, our findings led us to reject hypothesis H1, it should be stressed that these findings do not preclude this type of impact in other factory settings. Further research is needed to clarify these associations. Longitudinal studies, in particular, would control for baseline effects and so, improve causative interpretation of results. However, the study of Bakker and Sanz-Vergel (Citation2013), who reported no association between job demand, flourishing, and work engagement, was conducted using longitudinal data.

Limitations of our study include use of cross-sectional data, which precludes inferences about the direction of causality for observed associations. Hence, associations that we observed can be interpreted as likely drivers of effects, but we cannot rule out the possibility of reverse causality or correlation without causation. Nevertheless, to circumvent this limitation, reciprocal relations were examined. Future studies, however, should include in-depth analysis of longitudinal panel data to confirm causal influence, after successful identification of relevant correlates. Our study also focuses on Mexican factory workers in the apparel industry, which limits the generalizability of our findings for other professions, work settings, and countries/culture. Future research may benefit from examining other sectors of industry as well as evaluating workers in different countries.

Conclusions

Our study shows that in order to improve working conditions and well-being of workers, specific interventions by both factory management and global brands could be beneficial – recommendations already formulated by Locke, Amengual, and Mangla (Citation2009) and Lund-Thomsen and Lindgreen (Citation2014), among others. Cultivating appreciation of the importance of a worker’s value as a resource and not only perceiving them through the lens of cost is one such example. A second example is allowing greater decision autonomy of workers (Locke, Amengual, and Mangla Citation2009). Our findings indicate likely rewards to business from this type of worker empowerment.

Acknowledgement

The paper benefited substantially from comments and suggestions made by Irina Mordukhovich to whom authors are truly grateful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Dorota Węziak-Białowolska, Ph.D., is the research scientist at the Department of Environmental Health, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She is also affiliated at the Sustainability and Health Initiative for NetPositive Enterprises (SHINE) and the Human Flourishing Program at the Harvard University. Her research spans organizational psychology, psychometrics, economics, health, and wellbeing.

Piotr Białowolski, Ph.D., is the research scientist at the Department of Environmental Health, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He is also affiliated at the Sustainability and Health Initiative for NetPositive Enterprises (SHINE), Harvard University. He specializes in applied social science and quantitative methods for applied social and economic research. His empirical research is mainly on household economic and financial behavior and their association with well-being.

Eileen McNeely, Ph.D., conducts research and teaches in the Environmental Occupational Medicine and Epidemiology Program at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She has worked as a consultant, researcher, clinician, and educator in the field for over twenty years. She is the founder and director of the SHINE.

ORCID

Dorota Węziak-Białowolska http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2711-2283

Piotr Białowolski http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4102-0107

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguinis, Herman, Jeffrey R. Edwards, and Kyle J. Bradley. 2017. “Improving Our Understanding of Moderation and Mediation in Strategic Management Research.” Organizational Research Methods 20 (4): 665–685. doi:10.1177/1094428115627498.

- Akbari, Jafar, Habibollah Dehghan, Hiva Azmoon, and Farhad Forouharmajd. 2013. “Relationship between Lighting and Noise Levels and Productivity of the Occupants in Automotive Assembly Industry.” Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2013: Article ID 527078, 5. doi:10.1155/2013/527078.

- Albrecht, Simon L, Arnold B Bakker, Jamie A Gruman, William H Macey, and Alan M Saks. 2015. “Employee Engagement, Human Resource Management Practices and Competitive Advantage.” Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance 2 (1): 7–35. doi:10.1108/JOEPP-08-2014-0042.

- Avey, James B, Fred Luthans, and Susan M Jensen. 2009. “Psychological Capital: A Positive Resource for Combating Employee Stress and Turnover.” Human Resource Management 48 (5): 677–693. doi:10.1002/hrm.

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. “The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 22 (3): 309–328. doi:10.1108/02683940710733115.

- Bakker, Arnold B, and Ana Isabel Sanz-Vergel. 2013. “Weekly Work Engagement and Flourishing: The Role of Hindrance and Challenge Job Demands.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 83 ( Elsevier Inc.): 397–409. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2013.06.008.

- Bambra, Clare, Thorsten Lunau, Kjetil A. Van der Wel, Terje A. Eikemo, and Nico Dragano. 2014. “Work, Health, and Welfare: The Association between Working Conditions, Welfare States, and Self-Reported General Health in Europe.” International Journal of Health Services 44 (1): 113–136. doi:10.2190/HS.44.1.g.

- Barrientos, Stephanie, Gary Gereffi, and Arianna Rossi. 2011. “Economic and Social Upgrading in Global Production Networks: A new Paradigm for a Changing World.” International Labour Review 150 (3): 319–340. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2011.00119.x.

- Barrientos, Stephanie, Frederick Mayer, John Pickles, and Anne Posthuma. 2011. “Decent Work in Global Production Networks: Framing the Policy Debate.” International Labor Review 150 (3–4): 299–317.

- Beehr, T. A. 1976. “Perceived Situational Moderators of the Relationship Between Subjective Role Ambiguity and Role Strain.” Journal of Applied Psychology 61 (1): 35–40.

- Beehr, T. A., J. T. Walsh, and T. D. Taber. 1976. “Relationships of Stress to Individually and Organizationally Valued States: Higher Order Needs As a Moderator.” Journal of Applied Psychology 61 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.61.1.41.

- Behson, S. J. 2005. “The Relative Contribution of Formal and Informal Organizational Work–Family Support.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 66 (3): 487–500. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2004.02.004.

- Bentley, R. J., A. Kavanagh, L. Krnjacki, and A. D. LaMontagne. 2015. “A Longitudinal Analysis of Changes in Job Control and Mental Health.” American Journal of Epidemiology 182 (4): 328–334. doi:10.1093/aje/kwv046.

- Bielby, William T, and Robert M Hauser. 1977. “Structural Equation Models.” Annual Review of Sociology 3: 137–161.

- Bland, J Martin, and Douglas G Altman. 1997. “Statistics Notes: Cronbach’s Alpha.” British Medical Journal 314: 572.

- Brauchli, Rebecca, Gregor J Jenny, Désirée Füllemann, and Georg F Bauer. 2015. “Towards a Job Demands-Resources Health Model: Empirical Testing with Generalizable Indicators of Job Demands, JobResources, and Comprehensive Health Outcomes.” BioMed Research International 2015: Article ID 959621, 12. doi:10.1155/2015/959621.

- Brown, Timothy A. 2006. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Browne, Michael W., and Robert Cudeck. 1992. “Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit.” In Sociological Methods and Research 21, 230–258. Newsbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Cammann, C., M. Fichman, D. Jenkins, and J. Klesh. 1975. Michigan Organizational Assessment Package. Unpublished Manuscript. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

- Cammann, C., M. Fichman, G. D. Jenkins, and J. Klesh. 1983. “Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire.” In Assessing Organizational Change: A Guide to Methods, Measures, and Practices, edited by S. E. Seashore, E. J. Lawler, P. H. Mirvis, and C. Cammann, 71–138. New York, NY: John Wiley.

- Collingsworth, Terry. 2006. “Beyond Public Relations: Bringing the Rule of Law to Corporate Codes of Conduct in the Global Economy.” Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 6 (3): 250–260. doi:10.1108/14720700610671855.

- CSDH. 2008. Closing the Gap in a Generation. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. doi:10.1080/17441692.2010.514617.

- Daley, D. M. 1986. “Humanistic Management and Organizational Success: The Effect of Job and Work Environment on Organizational Effectiveness, Public Responsiveness, and Job Satisfaction.” Public Personnel Management 15 (2): 131–142.

- De Croon, Einar M., Judith K. Sluiter, Roland W.B. Blonk, Jake P.J. Broersen, and Monique H.W. Frings-Dresen. 2004. “Stressful Work, Psychological Job Strain, and Turnover: A 2-Year Prospective Cohort Study of Truck Drivers.” Journal of Applied Psychology 89 (3): 442–454. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.442.

- Demerouti, Evangelia, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2011. “The Job Demands–Resources Model: Challenges for Future Research.” SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 37 (2): 1–9. doi:10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974.

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Friedhelm Nachreiner, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2001. “The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout.” Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (3): 499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499.

- De Vries, Kets R. Manfred F., Danny Miller, Jean-marie Tousouse, Peter H Friesen, Maurice Botsvert, and Roland Theriault. 1984. “Using the Life Cycle to Anticipate Satisfaction at Work.” Journal of Forecasting 3: 161–172.

- Diener, Ed, and Louis Tay. 2017. “A Scientific Review of the Remarkable Benefits of Happiness for Successful and Healthy Living.” In Happiness: Transforming the Development Landscape, edited by The Centre for Bhutan Studies and GNH, 90–117. Thimphu, Bhutan: The Centre for Bhutan Studies and GNH.

- Diener, Ed, Derrick Wirtz, William Tov, Chu Kim-Prieto, Dong won Choi, Shigehiro Oishi, and Robert Biswas-Diener. 2010. “New Well-Being Measures: Short Scales to Assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings.” Social Indicators Research 97 (2): 143–156. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y.

- Dirnagl, Ulrich, and Martin Lauritzen. 2010. “Editorial: Fighting Publication Bias: Introducing the Negative Results Section.” Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 30 (7) Nature Publishing Group: 1263–1264. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2010.51.

- Egels-Zandén, Niklas, and Henrik Lindholm. 2015. “Do Codes of Conduct Improve Worker Rights in Supply Chains? A Study of Fair Wear Foundation.” Journal of Cleaner Production 107: 31–40. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.08.096.

- Eisenberger, Robert. 2003. “Perceived Organizational Support and Psychological Contracts: A Theoretical Integration.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 24 (5): 491–509. doi:10.1002/job.211.

- Eisenberger, R., and R. Huntington. 1986. “Perceived Organizational Support.” Journal of Applied Psychology 71: 500–507. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.75.1.51.

- Fanelli, Daniele. 2012. “Negative Results Are Disappearing from Most Disciplines and Countries.” Scientometrics 90 (3): 891–904. doi:10.1007/s11192-011-0494-7.

- Fu, Weihui, and Satish P Deshpande. 2014. “The Impact of Caring Climate, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment on Job Performance of Employees in a China’s Insurance Company.” Journal of Business Ethics 124: 339–349. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1876-y.

- Fuß, Isabelle, Matthias Nübling, Hans Martin Hasselhorn, David Schwappach, and Monika A. Rieger. 2008. “Working Conditions and Work-Family Conflict in German Hospital Physicians: Psychosocial and Organisational Predictors and Consequences.” BMC Public Health 8: 1–17. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-353.

- Hallberg, Ulrika E., and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2006. “‘Same Same’ but Different? Can Work Engagement Be Discriminated from Job Involvement and Organizational Commitment?” European Psychologist 11 (2): 119–127. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.11.2.119.

- Herr, Raphael M., Jos A. Bosch, Adrian Loerbroks, Annelies E.M. van Vianen, Marc N. Jarczok, Joachim E. Fischer, and Burkhard Schmidt. 2015. “Three Job Stress Models and Their Relationship with Musculoskeletal Pain in Blue- and White-Collar Workers.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 79 (5) Elsevier B.V.: 340–347. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.08.001.

- Holme, R., and P. Watts. 2000. Corporate Social Responsibility: Making Good Business Sense. Geneva, Switzerland: World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

- Holtom, Brooks C., Terence R. Mitchell, Thomas W. Lee, and Marion B. Eberly. 2008. “5 Turnover and Retention Research: A Glance at the Past, a Closer Review of the Present, and a Venture Into the Future.” The Academy of Management Annals 2 (1): 231–274. doi:10.1080/19416520802211552.

- Huppert, Felicia A, and Timothy T C So. 2013. “Flourishing Across Europe: Application of a New Conceptual Framework for Defining Well-Being.” Social Indicators Research 110: 837–861. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7.

- ILO, and IFC. 2016. Progress and Potential: How Better Work Is Improving Garment Workers’ Lives and Boosting Factory Competitiveness. A Summary of an Independent Assessment of the Better Work Programme. Geneva: International Labour Organization and International Finance Corporation.

- Jackson, Dennis L, J. Arthur Gillaspy, and Rebecca Purc-Stephenson. 2009. “Reporting Practices in Confirmatory Factor Analysis: An Overview and Some Recommendations..” Psychological Methods 14 (1): 6–23. doi:10.1037/a0014694.

- Karasek, Robert A. 1979. “Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign.” Administrative Science Quarterly 24 (2): 285–308.

- Karasek, Robert A, BongKyoo Choi, Per-Olof Ostergren, Marco Ferrario, and Patrick De Smet. 2007. “Testing Two Methods to Create Comparable Scale Scores between the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) and JCQ-Like Questionnaires in the European JACE Study.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 14 (4): 189–201. doi:10.1007/BF03002993.

- Keyes, Corey L. M. 1998. “Social Well-Being.” Social Psychology Quarterly 61 (2): 121–140. doi:10.2307/2787065.

- Kjellstrom, Tord, Ingvar Holmer, and Bruno Lemke. 2009. “Workplace Heat Stress, Health and Productivity-an Increasing Challenge for Low and Middle-Income Countries during Climate Change.” Global Health Action 2 (1): 1–6. doi:10.3402/gha.v2i0.2047.

- Kline, Rex B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Third. New York, London: The Guilfor Press.

- Klitzman, Susan, and Jeanne Stellman. 1989. “The Impact of the Physical Environment on the Psychological Well-Being of Office Workers.” Social Science and Medicine 29 (6): 733–742.

- Kolk, Ans. 2016. “The Social Responsibility of International Business: From Ethics and the Environment to CSR and Sustainable Development.” Journal of World Business 51 (1) Elsevier Inc.: 23–34. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2015.08.010.

- Lebaron, G., and J. Lister. 2015. “Benchmarking Global Supply Chains: The Power of the ‘Ethical Audit’ Regime.” Review of International Studies 41 (05): 905–924. doi:10.1017/s0260210515000388.

- Leeuw, Edith D. 2005. “To Mix or Not to Mix Data Collection Modes in Surveys.” Journal of Official Statistics 21 (2): 233–255. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1300874.

- Locke, Richard, Matthew Amengual, and Akshay Mangla. 2009. “Virtue out of Necessity? Compliance, Commitment, and the Improvement of Labor Conditions in Global Supply Chains.” Politics & Society 37: 319–351. doi:10.1177/0032329209338922.

- Locke, Richard, Thomas Kochan, Monica Romis, and Fei Qin. 2007. “Beyond Corporate Codes of Conduct: Work Organization and Labour Standards at Nike’s Suppliers.” International Labour Review A146 (1): 21–40. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2007.00003.x.

- Loscocco, Karyn, and Glenna Spitze. 1990. “Working Conditions, Social Support, and the Well-Being of Female and Male Factory Workers.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 31 (4): 313–327.

- Lund-Thomsen, Peter, and Adam Lindgreen. 2014. “Corporate Social Responsibility in Global Value Chains: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going?” Journal of Business Ethics 123 (1): 11–22. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1796-x.

- MacKinnon, D. P., A. J. Fairchild, and M. S. Fritz. 2007. “Mediation Analysis.” Annual Review of Psychology 58 ( Hebb 1966): 593–614. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542.Mediation.

- MacKinnon, David P., Chondra M. Lockwood, Jeanne M. Hoffman, Stephen G. West, and Virgil Sheets. 2002. “A Comparison of Methods to Test Mediation and Other Intervening Variable Effects.” Psychological Methods 7 (1): 83–104. doi:10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.83.

- Madsen, I. E. H., S. T. Nyberg, L. L. Magnusson Hanson, J. E. Ferrie, K. Ahola, L. Alfredsson, G. D. Batty, et al. 2017. “Job Strain as a Risk Factor for Clinical Depression: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Additional Individual Participant Data.” Psychological Medicine 47 (8): 1342–1356. doi:10.1017/S003329171600355X.

- Marmot, Michael, Sharon Friel, Ruth Bell, Tanja AJ Houweling, and Sebastian Taylor. 2008. “Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health.” The Lancet 372 (9650): 1661–1669. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6.

- Maslach, Christina, Wilmar B Schaufeli, and Michael P Leiter. 2001. “Job Burnout.” Annual Review of Psychology 52: 397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

- Matosin, N., E. Frank, M. Engel, J. S. Lum, and K. A. Newell. 2014. “Negativity Towards Negative Results: A Discussion of the Disconnect between Scientific Worth and Scientific Culture.” Disease Models & Mechanisms 7 (2): 171–173. doi:10.1242/dmm.015123.

- Morgeson, F. P., and S. E. Humphrey. 2006. “The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and Validating a Comprehensive Measure for Assessing Job Design and the Nature of Work.” Journal of Applied Psychology 91 (6): 1321–1339. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321.

- Morrison, Rachel L, and Helena D Cooper-Thomas. 2016. “Friendship Among Coworkers.” In The Psychology of Friendship, edited by M. Hojjat, and A. Moyer. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof.

- Mossholder, Kevin W, Randall P Settoon, and Stephanie C Henagan. 2005. “A Relational Perspective on Turnover: Examining Structural, Attitudinal, and Behavioral Predictors.” The Academy of Management Journal 48 (4): 607–618.

- Near, Janet P, and Mary Deane Sorcinelli. 1986. “Work and Life Away from Work: Predictors of Faculty Satisfaction.” Research in Higher Education 25 (4): 377–394.

- Neve, Jan-Emmanuel de, Christian Krekel, and George Ward. 2018. “Work and Well-Being: A Global Perspective.” In Global Happiness Policy Report, 74–128. Dubai: Global Happiness Council.

- Norman, Geoff. 2010. “Likert Scales, Levels of Measurement and the ‘Laws’ of Statistics.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 15 (5): 625–632. doi:10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y.

- Parsons, K. C. 2000. “Environmental Ergonomics: A Review of Principles, Methods and Models.” Applied Ergonomics 31 (6): 581–594. doi:10.1016/S0003-6870(00)00044-2.

- Pearl, Judea. 1998. “Graphs, Causality, and Structural Equations Models.” Sociological Methods & Research 27 (2): 226–284.

- Pernia, Ernesto M, and M. G. Quibria. 1999. “Poverty in Developing Countries.” Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics 3: 1865–1934. doi:10.1016/S1574-0080(99)80014-5.

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. “Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies.” Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5): 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

- Price, James L. 2001. “Reflections on the Determinants of Voluntary Turnover.” International Journal of Manpower 22 (7): 600–624. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000006233.

- Prilleltensky, Isaac. 2005. “Promoting Well-Being: Time for a Paradigm Shift in Health and Human Services.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, Supplement 33 (66): 53–60. doi:10.1080/14034950510033381.

- Rhemtulla, Mijke, Patricia É. Brosseau-Liard, and Victoria Savalei. 2012. “When Can Categorical Variables Be Treated as Continuous? A Comparison of Robust Continuous and Categorical SEM Estimation Methods Under Suboptimal Conditions.” Psychological Methods 17 (3): 354–373. doi:10.1037/a0029315.

- Rhoades, Linda, and Robert Eisenberger. 2002. “Perceived Organizational Support: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Applied Psychology 87 (4): 698–714. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.87.4.698.

- Rice, R. W., J. P. Near, and R. G. Hunt. 1980. “The Job-Satisfaction/ Life-Satisfaction Relationship: A Review of Empirical Research.” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 1 (1): 37–64. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp0101_4.

- Rourke, E. L. 2014. “Better Work Discussion Paper Series: No. 15.” Better Work Discussion Series, no. 15.

- Ryff, Carol D. 1995. “Psychological Well-Being in Adult Life.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 4 (4): 99–104.

- Ryff, C. D., and C. L. Keyes. 1995. “The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69 (4): 719–727. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719.

- Saijo, Y., S. Chiba, E. Yoshioka, Y. Nakagi, T. Ito, K. Kitaoka-Higashiguchi, and T. Yoshida. 2015. “Synergistic Interaction between Job Control and Social Support at Work on Depression, Burnout, and Insomnia among Japanese Civil Servants.” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 88 (2): 143–152. doi:10.1007/s00420-014-0945-6.

- Sanne, Bjarte, Arnstein Mykletun, Alv A. Dahl, Bente E. Moen, and Grethe S. Tell. 2005. “Testing the Job Demand-Control-Support Model with Anxiety and Depression as Outcomes: The Hordaland Health Study.” Occupational Medicine 55 (6): 463–473. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqi071.

- Schaufeli, W. B., A. B. Bakker, and M. Salanova. 2016. “The Measurement of Work Engagement With a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 66 (4): 701–716. doi:10.1177/0013164405282471.

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Toon T Taris. 2014. “Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach.” In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach, edited by Georg F. Bauer and Oliver Hämmig, 43–68. London: Springer.

- Short, Jodi L., Michael W. Toffel, and Andrea R Huguill. 2014. “Monitoring the Monitors: How Social Factors Influence Supply Chain Auditors.” Strategic Management Journal 37: 1878–1897.

- Sias, Patricia M, and Daniel J Cahill. 1998. “From Coworkers to Friends: The Development of Peer Friendships in the Workplace.” Western Journal of Communication 62 (3): 273–299.

- Siegrist, Johannes. 1996. “Adverse Health Effects of High-Effort/Low-Reward Conditions.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1 (1): 27–41. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27.

- Skagert, Katrin, Lotta Dellve, and Gunnar Ahlborg. 2012. “A Prospective Study of Managers’ Turnover and Health in a Healthcare Organization.” Journal of Nursing Management 20 (7): 889–899. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01347.x.

- Spell, Hannah B., Lillian T. Eby, and Robert J. Vandenberg. 2014. “Developmental Climate: A Cross-Level Analysis of Voluntary Turnover and Job Performance.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 84 (3) Elsevier Inc.: 283–292. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2014.02.001.

- Stansfeld, Stephen A., Martin J. Shipley, Jenny Head, and Rebecca Fuhrer. 2012. “Repeated Job Strain and the Risk of Depression: Longitudinal Analyses from the Whitehall Ii Study.” American Journal of Public Health 102 (12): 2360–2366. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300589.

- Su, Rong, Louis Tay, and Ed Diener. 2014. “The Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and the Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT).” Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 6 (3): 251–279. doi:10.1111/aphw.12027.

- Tavakol, Mohsen, and Reg Dennick. 2011. “Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha.” International Journal of Medical Education 2 (June): 53–55. doi:10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd.

- Upadyaya, Katja, Matti Vartiainen, and Katariina Salmela-Aro. 2016. “From Job Demands and Resources to Work Engagement, Burnout, Life Satisfaction, Depressive Symptoms, and Occupational Health.” Burnout Research 3 Elsevier GmbH.: 101–108.

- VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2017. “On the Promotion of Human Flourishing.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114: 8148–8156.

- Węziak-Białowolska, D., Tamar Koosed, Carlued Leon, and Eileen McNeely. 2017. “A New Approach to the Well-Being of Factory Workers in Global Supply Chains: Evidence from Apparel Factories in Mexico, Sri Lanka, China and Cambodia.” In Measuring the Impacts of Business on Well-Being and Sustainability, edited by OECD, HEC Paris, and SnO centre, 130–154. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Węziak-Białowolska, D., E. McNeely, and T. VanderWeele. 2019. “Flourish Index and Secure Flourish Index – Validation in Workplace Settings.” Cogent Psychology 6: 1–10. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3145336.

- White, Sarah C. 2017. “Relational Wellbeing: Re-Centring the Politics of Happiness, Policy and the Self.” Policy and Politics 45 (2): 121–136. doi:10.1332/030557317X14866576265970.

- World Bank. 2015. Interwoven: How the Better Work Program Improves Job and Life Quality in the Apparel Sector. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Xiang, Jianjun, Peng Bi, Dino Pisaniello, and Alana Hansen. 2014. “Health Impacts of Workplace Heat Exposure: An Epidemiological Review.” Industrial Health 52 (2): 91–101. doi:10.2486/indhealth.2012-0145.

- Young, Cheri A., and David L. Corsun. 2010. “Burned! The Impact of Work Aspects, Injury, and Job Satisfaction on Unionized Cooks’ Intentions to Leave the Cooking Occupation.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research 34 (1): 78–102. doi:10.1177/1096348009349816.

- Zheng, Xiaoming, Weichun Zhu, Haixia Zhao, and C. H. I. Zhang. 2015. “Employee Well-Being in Organizations: Theoretical Model, Scale Development, and Cross-Cultural Validation.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 36: 621–644. doi:10.1002/job.

- Zohar, Dov, and David A. Hofmann. 2012. “Organizational Culture and Climate.” In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Psychology, edited by Steve W. J. Kozlowski, 1:1–43. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199928309.013.0020.