ABSTRACT

Amid the increasing use of qualitative methods in the field of sport psychology, a number of researchers have initiated discussions about issues of rigour and quality in qualitative inquiry. Methodological coherence has been offered as an approach to strengthening qualitative inquiry by ensuring that the elements of qualitative research are appropriately aligned. This study presents a focused mapping review and synthesis of the methodological coherence of qualitative sport psychology research published in five peer-reviewed journals over 30 years. 710 articles were subjected to an in-depth analysis. The philosophical position, methodology, data generation and analysis methods, presentation of findings, description of quality, statement of researcher position, and methodological coherence of each article were coded. Results indicated that post-positivist or critical realist approaches are dominant in sport psychology, although there has been an increase in the variety of philosophical positions employed over time. Further, the majority of articles in sport psychology were methodologically coherent. We conclude by forwarding practical considerations for thinking through and designing methodologically coherent qualitative studies in sport psychology, which are intended to be accessible for all researchers.

The field of sport psychology has benefitted from a strong history of qualitative inquiry that has shaped theory and practice among researchers and practitioners. The growing popularity of qualitative research in sport psychology has most notably been documented in two major reviews conducted by Culver and colleagues (Culver, Gilbert, & Sparkes, Citation2012; Culver, Gilbert, & Trudel, Citation2003). The first review (Culver et al., Citation2003) examined the publication of qualitative research across three sport psychology journals from 1990 to 1999 and found that 17.3% of all published articles were qualitative studies. In their subsequent review, Culver et al. (Citation2012) found that 29% of articles published between 2000 and 2009 were qualitative studies, demonstrating an increase from the previous 10-year period. The authors also reported an upward trajectory in the number of qualitative studies published in the three journals they reviewed – from an average of 16.7 studies published early in the decade (2001–2003) to an average of 24 articles published later in the decade (2007–2009). The popularity and value of qualitative research approaches can further be evidenced through the launch of the journal Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health Psychology (QRSEH) in 2009, which provides researchers with another outlet to publish their qualitative work.

In their reviews, Culver and colleagues (Citation2003, Citation2012) also described some of the characteristics of qualitative studies published in sport psychology. For example, interviews were used as the primary method of data collection in 80% of qualitative articles between 1990 and 1999 (Culver et al., Citation2003) and in 78% of articles between 2000 and 2009 (Culver et al., Citation2012). Commonly used indicators of validity reported in the studies included peer review/peer debriefing, reliability checks of the coded data, member checking, and details about the researcher as the instrument of data collection (Culver et al., Citation2003, Citation2012). In terms of the presentation of results, 18% of articles presented quotations from study participants, 25% presented descriptive statistics, and 57% presented a combination of quotations and statistics between 1990 and 1999 (Culver et al., Citation2003). Between 2000 and 2009, results were presented in the form of quotations in 39.8% of articles, descriptive statistics were presented in 10% of articles, and a combination of quotations and statistics were presented in 52% of articles (Culver et al., Citation2012). Finally, Culver et al. (Citation2012) also noted that between 2000 and 2009, 14% of qualitative articles provided information about the epistemological positioning of the study; however, epistemological assumptions were not examined as part of their review of qualitative studies between 1990 and 1999.

These reviews have been valuable in documenting the types of methods and methodologies used in qualitative research in sport psychology, as well as the increase in qualitative research between 1990–1999 and 2000–2009. However, as with any study, there were some limitations to the reviews from Culver and colleagues (Citation2003, Citation2012). For example, these reviews examined the prevalence of qualitative research across two separate 10-year periods, ending in 2009. In the present review, we examined trends in qualitative research beginning with the first issue of five sport psychology journals until July 2017, providing an update on the current state of qualitative research in sport psychology. Second, Culver and colleagues (Citation2003, Citation2012) examined qualitative studies published in three journals (Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, JASP; Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, JSEP; The Sport Psychologist, TSP). We expanded the scope of our review by including two other journals: QRSEH and Psychology of Sport and Exercise (PSE). We chose to include QRSEH and PSE because they are two prominent peer-reviewed journals in the field that have a track-record of publishing qualitative research. Finally, the Culver et al. (Citation2003, Citation2012) reviews provided separate descriptive results for the use of particular methods (e.g. interviews, observations), methodologies (e.g. case study, phenomenology, etc.), and statements of authors’ epistemological position in published studies. That is, the authors analyzed the components of previous qualitative research separately, and it is important to consider how these separate elements of a qualitative study fit together in a coherent manner. Thus, in order to build on the previous reviews of qualitative research in sport psychology, we sought to examine the ways in which the separate elements of published qualitative studies have been presented in a manner that is ‘methodologically coherent’ (Mayan, Citation2009).

Methodological coherence refers to the ‘congruence between your epistemological and ontological viewpoint, your theoretical position/perspective, the methods you choose, and so on’ (Mayan, Citation2009, p. 13; Morse, Citation1999). In order for a study to be methodologically coherent, researchers must be aware of the philosophical assumptions underpinning their research and select the most appropriate methods to achieve their intended research aims. Mayan (Citation2009) reinforced the importance of developing qualitative studies that are rigorous and methodologically coherent by arguing: ‘you cannot just pick and choose from any possible qualitative strategy available, throw it into the soup, and expect it to work out. This makes qualitative work sloppy and unscientific’ (Mayan, Citation2009, p. 17). The determination of a methodologically coherent study rests on the understanding that the various elements of a qualitative study (e.g. research question, methods, methodology, presentation of results) are aligned with the philosophical assumptions underpinning the research. Research is thus informed by epistemological and ontological assumptions; together, these make up the ‘worldview’ or the philosophical position of the researcher (also referred to as a paradigm or paradigmatic position), informing their choice of research question(s), methodological approach, methods, analyses, and presentation of results in a study (Guba & Lincoln, Citation1998; Mayan, Citation2009).

Ontological assumptions concern the nature of reality, and a broad distinction between ontological positions is between realist and relativist positions. A realist ontological position implies a belief in an external reality that exists independently of the researcher's knowledge of it.Footnote1 A relativist ontological position implies that the concept of ‘reality’ is dependent on those interpreting it (Guba & Lincoln, Citation1998; Lincoln, Lynham, & Guba, Citation2018).

Epistemological assumptions concern the generation of knowledge and considerations of what ‘counts’ as knowledge and truth (Guba & Lincoln, Citation1998). One broad distinction between epistemological positions is between modified dualist/objectivist and subjective/transactional positions. A modified dualist/objectivist position implies the researcher attempts to gain knowledge about a phenomenon by observing, measuring, and assessing it as objectively as possible, accounting for and attempting to minimize their influence on the research process (Guba & Lincoln, Citation2005; Lincoln et al., Citation2018). A subjectivist/transactional epistemological position suggests that knowledge production can never be free of one's prior information or experiences (e.g. knowledge cannot be ‘value-free’ or ‘theory-free’; Guba & Lincoln, Citation1998; Lincoln et al., Citation2018). Thus, from this position, knowledge is produced (also described as ‘co-constructed’) through transactions between researcher and participant, each bringing their prior experiences and understandings to bear on the topic of investigation.

Framed by these ontological and epistemological assumptions, researchers may adopt different philosophical positions from which to conduct their research. Post-positivist philosophical approaches (also referred to as critical realist approaches in the current study)Footnote2 have underpinned the majority of qualitative studies conducted in the field of sport psychology to date (Culver et al., Citation2012). Other philosophical positions described in the sport psychology literature include interpretivism, constructivism, constructionism, pragmatism, and postmodern, critical, and feminist approaches (see Table 1 in the Supplementary File for a brief overview of some of the distinctions between these positions). It is important to note that qualitative research may be conducted from a range of philosophical positions, and researchers conducting qualitative studies do not necessarily adopt relativist ontological and subjectivist/transactional epistemological assumptions (Wiltshire, Citation2018). Several scholars have written at length on these topics, including Creswell and Poth (Citation2018), Lincoln et al. (Citation2018), Sparkes and Smith (Citation2014), Tamminen and Poucher (Citationin press), and Wiltshire (Citation2018). The Supplementary File contains examples of studies from each of these philosophical positions.

Holt and Tamminen (Citation2010) previously suggested that methodological coherence was a useful guiding principle for making research decisions in grounded theory studies. Methodological coherence offers researchers a way to think through and design qualitative studies that demonstrate alignment from research question to data interpretation. The notion of methodological coherence offers a valuable way of thinking about issues of quality and rigour in qualitative research: from this perspective, the assessment of a study's quality rests on the alignment between the researcher's philosophical position and the overall coherence of the study. Mayan (Citation2009) argued that if the researcher's position does not fit with the research question, the rigour of the study is compromised. For example, a sport psychology study examining athletes’ experiences in sport conducted from a constructionist philosophical position (with relativist ontological assumptions and subjectivist/transactional epistemological assumptions) would not aim to produce a frequency analysis of themes reported by participants. Analyzing and presenting the results in that manner is more reflective of the underlying assumptions of post-positivism or critical realism. Furthermore, the notion of methodological coherence suggests that a study should be evaluated based on the alignment of the design, methods, analyses, and presentation of results with its stated ontological and epistemological position. For example, it would be inappropriate to use realist criteria (e.g. inter-rater reliability, validity, objectivity) to evaluate our fictitious example because constructionism holds relativist philosophical assumptions. Rather, qualitative research grounded in relativist ontology and subjectivist/transactional epistemology would be better evaluated by considering its credibility or meaningful coherence (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). For further discussion of these topics, see Eakin and Mykhalovskiy (Citation2003), Smith and McGannon (Citation2018), Sparkes (Citation1998), and Sparkes and Smith (Citation2009).

At present, no reviews have examined the concept of methodological coherence of qualitative studies in sport psychology. Because of the previously-documented increase in qualitative research in sport psychology (Culver et al., Citation2003, Citation2012), and due to a growing awareness of the need to ensure that qualitative studies are of high quality (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018), we sought to examine the issue of methodological coherence in the field of sport psychology. Recently, Bradbury-Jones and colleagues (Citation2017) took a similar approach to reviewing the methodological coherence of qualitative research across a three-month period in health psychology journals. This type of review and analysis is valuable as it can point to examples of high-quality, methodologically coherent research within a field and help to provide guidance for researchers seeking to adopt qualitative methods in their work. Thus, the purpose of this study was to conduct a focused mapping review and synthesis of the methodological coherence of qualitative sport psychology research published in five of our field's major international peer-reviewed outlets. Our specific objectives were to: (a) describe the characteristics of qualitative sport psychology articles (philosophical positioning, methodological approach, methods of data generation and analysis, rigour/trustworthiness); (b) code and appraise the methodological coherence of these articles; and (c) analyze trends in the use of philosophical positions and methodological coherence over time and across journals. In conducting this review, we aimed to advance the topic of methodological coherence in qualitative sport psychology research by increasing awareness and providing examples of methodologically coherent articles. We also aimed to provide researchers with suggestions for thinking through and designing methodologically coherent qualitative research.

Methods

Methodology

The methodology selected for this review was a ‘focused mapping review and synthesis’ because we focused on (a) a particular subject, (b) a defined time period, and (c) specific journals (Bradbury-Jones et al., Citation2017; Grant & Booth, Citation2009). The characteristics of a focused mapping review and synthesis methodology are well-suited for the present study given our stated goal of reviewing and synthesizing qualitative sport psychology research, with a particular focus on analyzing the coherence of these articles, and providing examples for other researchers about carrying out coherent qualitative work in sport psychology. We included five of our field's major international peer-reviewed sport psychology outlets for this review study: JASP (1989–2017); JSEP (1978–2017); PSE (2000–2017); QRSEH (2009–2017); TSP (1987–2017). To be included in this review, articles must have been (a) published in one of the journals listed above before July 2017, and (b) an article that presented original data. Consistent with Bradbury-Jones and colleagues’ (Citation2017) focused mapping review, we included articles that were solely qualitative studies (i.e. not mixed methods).

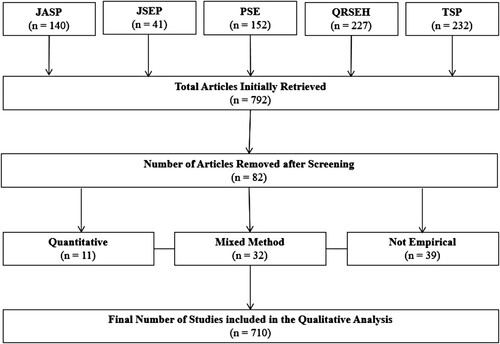

We identified articles by looking through the table of contents of each issue of the abovementioned journals up until we began the search (July 2017). Based on the initial screening of titles and abstracts, 792 articles met the inclusion criteria across the five journals. After a more detailed screening, 82 articles were excluded because they were either quantitative (n = 11), mixed methods (n = 32), or not empirical (e.g. reviews, ‘professional practice’ articles in TSP; n = 39). As a result, 710 articles were included in the final review (see for article screening and selection).

Researcher positioning

All four authors have varying levels of experiences using qualitative research approaches. ZP, KT, and JC consider themselves to be primarily qualitative researchers because the majority of their training and current research programmes use qualitative approaches. SS primarily classifies himself as a quantitative researcher, however SS has recently started integrating qualitative approaches into his research programme. In fact, the impetus for conducting this study resulted in part from SS's recent interest in qualitative approaches, and from the lack of accessible resources to learn more about conducting methodologically coherent qualitative work in sport psychology.

In line with the purpose and objectives of this research, we approached this study from a post-positivist/critical realist philosophical position. Given that our purpose was to appraise the methodological coherence of selected studies and analyze trends in paradigm use, a quantitative approach founded in a post-positivist philosophical position was required to achieve these goals. The steps we took throughout the research process aligned with this position and helped to ensure the coherence of this project (e.g. engaging in benchmarking sessions to ensure consistency in coding between raters, double coding and calculating interrater reliability, using statistical analyses, and presenting the results as frequencies and examining patterns over time).

We do not wish (and are not naïve enough) to attempt to position ourselves as ‘experts’, or as the sole authorities, on this topic. In contrast, we approached this study with the ultimate goal of helping readers of this paper to (continue to) conduct methodologically coherent qualitative sport psychology research. Having taught courses on qualitative inquiry and recently conducted a symposium on qualitative research approaches (Tamminen, Poucher, Sweet, & Caron, Citation2018), we sensed that many of our peers and trainees approach qualitative work with a certain degree of hesitancy. We hope that by being transparent about both our positioning as researchers, and the decisions we made throughout the research process, we will help to improve the accessibility of qualitative research. Additionally, we will be engaging in some of the recommended open science practices for qualitative researchers (Tamminen & Poucher, Citation2018), which includes sharing our coding spreadsheet and detailed instructions of our review protocol (see Supplementary File).

Article coding

Training the coding team

The initial coding of the articles was conducted by ZP and JC, with the assistance of seven undergraduate students and one graduate student from the University of Toronto and McGill University. Prior to coding, all members of the research team (coders and all study authors) participated in a training workshop that was created and delivered by ZP. The focus of the workshop was to gain a consistent understanding of the key paradigms (i.e. post-positivism/critical realism, constructivism/interpretivism, constructionism, post-modernism/post-structuralism, critical feminism/emancipatory, and pragmatism), ontologies, epistemologies, methods of data collection and analysis, and strategies for ensuring trustworthiness and rigour that are prevalent in sport psychology research. Additionally, each of the authors, undergraduate, and graduate coders participated in a benchmarking coding session to familiarize themselves with the coding spreadsheet (see the Supplementary File), the process of coding articles, and to help ensure articles were being coded consistently. Each coder had also taken at least one research methods class at their respective institutions. See the Supplementary File for a copy of the instruction sheet that was sent to coders explaining how articles were to be reviewed. All of the authors and coders independently coded the same five articles and then met as a group to discuss the coding. Because there were some discrepancies, we conducted a second benchmarking coding session, which resolved most of the concerns we observed in the first session. The workshop and benchmarking sessions were conducted to help ensure that all coders had sufficient expertise to assist with the coding of articles for this project.

In the initial coding process, three of the undergraduate students were responsible for coding 85 articles each, two undergraduate students were responsible for coding 105 articles each, and one undergraduate student was responsible for coding 134 articles. The graduate student coded 33 articles, ZP coded 121 articles, and JC coded 39 articles. Additionally, ZP and JC reviewed 91 articles that the undergraduate and graduate students had difficulty coding. This process meant that ZP and JC directly coded 251 of the articles.

Process of coding the articles

Each article was subjected to an in-depth analysis by the coders to identify the following information: philosophical position, methodology, data generation methods, data analysis methods, results and presentation of findings, description of quality (e.g. addressing issues of validity, rigour and trustworthiness), statement of researcher position, and methodological coherence. All of this information was recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet composed of multiple tabs. The first tab contained the full APA references of each article and their respective philosophical position (see the Supplementary File), while each subsequent sheet contained all the articles of a specific philosophical position (i.e. all articles identified as constructionist were coded in the ‘constructionist’ tab; see the Supplementary File). When identifying the philosophical position of an article, coders noted whether the authors had explicitly stated their philosophical position or not (i.e. stated vs. assumed). If the authors of an article included an explicit statement about their philosophical position, it was coded as ‘explicitly stated’ in the ‘philosophical position’ column of the relevant sheet. If the authors had not stated their philosophical position, the coder would make an informed assumption based on key characteristics of the article. For example, if the authors presented frequencies of participants’ responses and inter-rater reliability coefficients, the article was coded as ‘assumed post-positivist’.

Next, coders identified whether or not the authors explicitly stated the use of a specific methodology (i.e. stated vs. not stated), the method(s) that were used to generate (e.g. semi-structured interviews) and analyze the data (e.g. discourse analysis), as well as how the results were presented (e.g. ‘themes with supporting quotes’ or ‘frequency/percentage reporting theme’). Coders then identified the ways that authors had addressed issues of validity, rigour, or trustworthiness (e.g. inter-rater reliability, prolonged engagement, engaging with critical friend, reflexive journaling). When explicit terminology was not included in studies, coders interpreted what had been done and coded the steps with condensed, explicit terms. For example, a statement such as ‘a preliminary description of themes was returned to participants so that they could contribute to the ongoing process of data analysis’ was coded as ‘member checking/member reflections’. If coders could not identify any steps that were taken to address issues of validity, rigour, or trustworthiness then they wrote ‘none stated’ in the associated column. Coders also made a determination about whether or not the authors had included a statement about their position as a researcher in relation to the study, and coded it as either ‘yes’ or ‘no/not stated’.

Lastly, coders were asked to make a determination about the methodological coherence of the study and the alignment between the different aspects of the study. That is, the coder assessed whether the information presented in the study was methodologically coherent and demonstrated alignment between the stated or assumed paradigm, methodology, steps taken to generate and analyze data, presentation of the results, and trustworthiness. While not explicitly included in the coding sheet, the purpose statement and research questions of each study were reviewed by the coders to help them determine the methodological coherence of the studies. Coders were asked to make a simple yes/no distinction for methodological coherence. If a coder was unsure about the methodological coherence of a study, they left this column blank, and sent the article to ZP and JC, who reviewed the article and made a determination about the study's methodological coherence. Once all 710 articles were initially coded, ZP reviewed the coding of each article to ensure completeness, and to review any notes that coders had left about their articles. Moreover, all articles that were coded in the constructionist, post-modern/post-structural, critical feminist/emancipatory, and pragmatic tabs were reviewed again by KT because these philosophical positions are less common in sport psychology research, and we wanted to ensure that they had been appropriately coded. Please refer to the Supplementary File to see some examples of article coding within the various paradigms.

‘Unsure articles’ and double-coding

A number of articles (n = 91) were flagged by the undergraduate and graduate coders as being challenging, as they were unsure how to code portions of the study. In these cases, the articles were sent to ZP and JC, who then recoded the articles. We also conducted a double-coding process to get a sense of the interrater reliability (i.e. consistency with which the articles were coded). The authorship team chose to arbitrarily double-code every 10th article retrieved from all five journals, totalling 78 (11%) of the articles. ZP and SS coded 34 articles, and KT and JC coded the remaining 34 articles to determine methodological coherence. As a result, interrater agreement was calculated based on the assessments of three coders. Throughout this process, the coders disagreed on the methodological coherence of 7 articles (e.g. two coders thought the study was coherent, one did not), resulting in an acceptable interrater agreement of 91% and a Fleiss's kappa of .85. We hope this rate offers the reader some degree of confidence in our coding of the articles reviewed in this study.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics (e.g. means, percentages) were first used to report the overall number of qualitative publications from 1987 to July 2017 and the number by journal and philosophical position. We also used descriptive statistics to report the number of articles where the philosophical position was stated or assumed, and the number of articles that were methodologically coherent with the stated or assumed philosophical position. Using these descriptive statistics, we graphically illustrated the trends of qualitative articles over the past 30 years, and the trends by journal and philosophical position. We examined whether the number of qualitative articles across all journals over the past 30 years was equal by running a one-way chi-square analysis. The analysis was repeated after removing articles from QRSEH, given the journal was launched in 2009 and solely focuses on qualitative studies.

We then compared whether the number of articles that stated or assumed their philosophical position differed by (a) journal and (b) philosophical positioning by running crosstabs with chi-square analyses. The same analyses were performed to examine whether the number of articles that were coherent or non-coherent differed by (a) journals, (b) philosophical position, and (c) philosophical position stated or assumed. A significant chi-square indicates that the number of articles of a specific grouping or cell (e.g. observed number of stated philosophical position articles for QRSEH) was higher or lower than a computed expected score. To determine which grouping or cell differed, standardized residuals were examined. A standardized residual equal to or above 1.96 indicates that the observed count (i.e. the observed number of articles in a grouping/cell) was significantly higher or lower from the expected count (i.e. a calculated score of the expected number of articles in that grouping/cell). Cramer's V or Phi values of .10, .30, and .50 are presented to demonstrate if the difference was small, moderate, or large, respectively.

Results

Descriptive statistics and trends

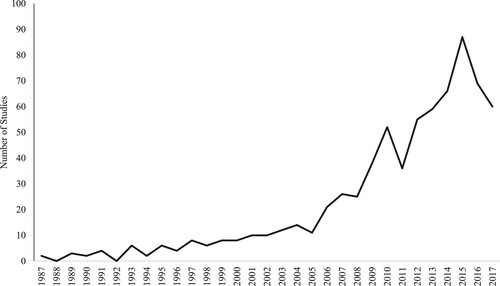

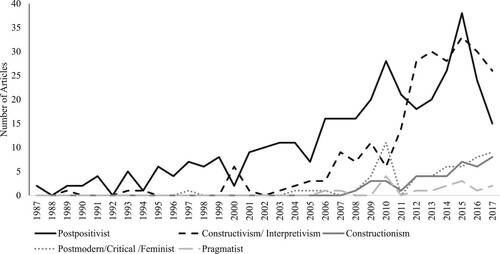

As illustrated in , the number of published qualitative articles increased from two in 1987 to 60 in 2017, and thus they were not equally distributed across the 30 years, χ2 (28) = 719.25, p < .001. The trend maintains after removing articles from QRSEH, χ2 (28) = 332.09, p < .001. Of the five journals we examined, QRSEH (28%) and TSP (28%) published the most qualitative research studies while the JSEP published the least (5%). We could not statistically compare whether the journals published more or less articles grounded in specific philosophical positions. Too few journals published articles across all philosophical positions, resulting in too many expected counts below five. Running the analysis would have violated the assumption of a chi-square analysis, which is to have at least an expected count of five in most cells. The authors explicitly stated their philosophical position in 29% of the articles and only 4% of all articles were identified as being methodologically non-coherent (e.g. not aligned with the stated or assumed philosophical position).

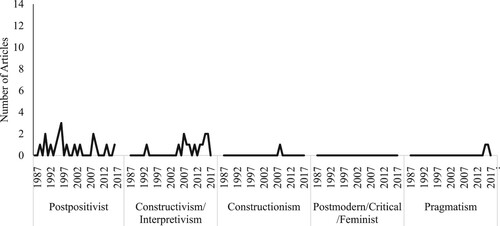

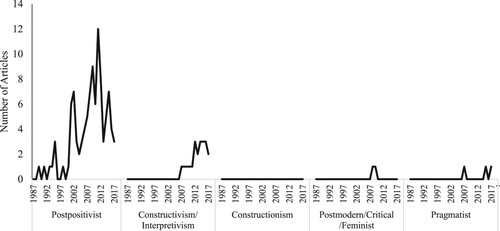

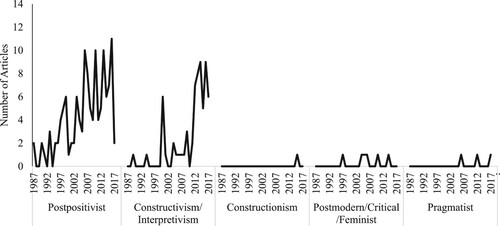

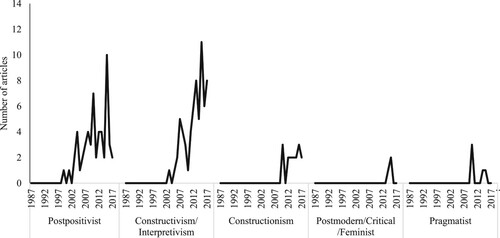

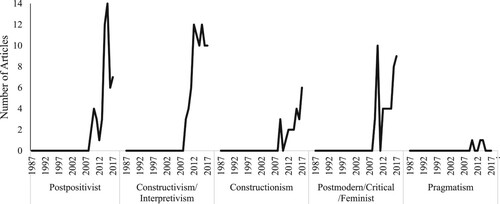

outlines the number of articles by philosophical positions and methodological coherence for each journal. Of the 710 articles across all journals, 50% were positioned as post-positivist, 34% as constructivist, 6% as constructionist, 8% as post-modern/critical theory, and 2% as pragmatist. In , a notable increase is constructivist articles across all journals from 2011 was observed. Of the 241 constructivist articles, 52 (22%) were constructivist articles published pre-2011 and 189 (88%) post-2011, which represents significantly more articles post-2011 than pre-2011, χ2 (1) = 77.88, p < .001. The trends of published articles by philosophical position within each journal are illustrated in –.

Figure 3. Number of qualitative studies across all five journals by philosophical position from 1987 to July 2017.

Figure 5. Number of qualitative articles in QRSEH by year and paradigm. Note the journal began publishing issues in 2009.

Table 1. Number of articles per journal across philosophical position, philosophical position acknowledgement, and methodological coherence.

Philosophical position stated or assumed

Significant differences were found in the number of articles where the philosophical position was stated or assumed by journal, χ2 (4) = 45.57, p < .001, Cramer's V = .25. Specifically, in QRSEH and PSE, authors stated their philosophical positions more than the expected count. Specifically, QRSEH had 78 observed articles that authors stated their philosophical positions, which was greater than the calculated count expecting 60 articles that authors would have stated their philosophical assumption. It was significant because the standardized residual was 2.4, which was greater than 1.96. For PSE, these results can be summarized as the 63 observed articles/counts were significantly greater than the 42 expected articles/counts with a standardized residual of 3.2. From hereon in, this interpretation will be written as: 63 observed vs 42 expected counts; standardized residual = 3.2. The authors’ philosophical position was assumed in JASP more than the expected count (110 observed vs 91 expected counts; standardized residual = 2.4). Significant differences were also found when examining the extent to which the philosophical position was assumed or stated across philosophical positions, χ2 (4) = 204.17, p < .001, Cramer's V = .54. More articles were assumed post-positivist than expected (332 observed vs 250.5 expected counts; standardized residuals = 5.1) and less were stated as post-positivist (23 observed vs 104.5 expected; standardized residuals = −8.0). Conversely, more authors stated their philosophical position than expected in constructivist (117 observed vs 71 expected counts; standardized residuals = 5.5), constructionist (25 observed vs 12 expected counts; standardized residuals = 4.3), post-modern/critical theory (26 observed vs 17 expected counts; standardized residuals = 2.3), and pragmatist articles (16 observed vs 5 expected counts; standardized residuals = 5.2). The philosophical position was stated in all 16 pragmatist articles.

Methodological coherence

The number of methodologically coherent and non-coherent articles did not significantly differ from the expected counts across journals, χ2 (4) = 2.47, p = .65, Cramer's V = .06. Significant differences were found when comparing methodological coherence across philosophical positions, χ2 (4) = 26.16, p < .001, Cramer's V = .19. Specifically, a smaller number of post-positivist articles were found to be non-coherent than expected (4 observed vs 14 expected counts; standardized residuals = 2.7). More constructivist (20 observed vs 9.5 expected counts; standardized residuals = 3.4) and constructionist articles (4 observed vs 1.6 expected counts; standardized residuals = 1.9) were found to be non-coherent than the expected counts. Rates of methodological coherence across philosophical positions did not diverge from expected counts (standardized residuals < |.7|). Methodological non-coherence was associated with whether the philosophical position was stated or assumed, χ2 (1) = 24.75, p < .001, Phi = .19. More articles than expected were identified as non-coherent when the philosophical position was stated (20 observed vs 8.2 expected counts; standardized residuals = 4.1).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to conduct a focused mapping review and synthesis of the qualitative sport psychology research published in five of our field's most influential international peer-reviewed outlets. By reviewing the published qualitative sport psychology literature over a 30-year period, we found an increase in the number of published qualitative articles from 1987 to 2017, which echoes Culver and colleagues’ (Citation2003, Citation2012) findings. This study extends previous reviews by examining trends in qualitative publications over a 30-year period. Additionally, we examined the methodological coherence of the included studies, and we provided a detailed examination of the different philosophical positions that have been used in sport psychology over this time period.

We found that there was an increase over time in the number of articles in which researchers stated their philosophical position, and we found that the use of different philosophical positions for qualitative inquiry is flourishing in sport psychology. There was a notable increase in the publication of constructivist qualitative articles after 2011, and there was an increase in post-modern/critical/feminist qualitative articles after 2012. Trends in the adoption of different philosophical positions may reflect the influence of editors and journals who have been increasingly more accepting of novel paradigmatic and methodological approaches within the last decade. For example, QRSEH launched in 2009, and the visibility of the journal with its mission to solely publish qualitative research may have contributed to an increase in the number of qualitative studies published across the field of sport psychology in the years following its inception. By providing an outlet for researchers to publish various forms qualitative inquiry beyond post-positivist or critical realist approaches, the journal may have contributed to a growth in the types of qualitative studies published across the field.

Post-positivism remains the dominant paradigm for qualitative research in sport psychology. Most articles were identified as reflecting underlying assumptions associated with post-positivism or critical realism. We also found that articles identified as post-positivist were the least likely to include an explicit statement regarding the philosophical positioning of the study, which provides additional evidence of the dominance of post-positivist approaches to research in sport psychology. We surmise that because post-positivism has been the dominant approach for scholarship in the field of sport psychology (Brustad, Citation2008), authors operating from this position may not have had to explicitly state the assumptions underlying their research. Within this context, researchers conducting qualitative inquiry from relativist positions (constructivism, constructionism, post-modernism, etc.) may have been required to explicitly state their assumptions in order to have their work be understood and seen as legitimate. This suggestion is supported by our review because more authors explicitly stated their philosophical assumptions when studies were approached from relativist positions.

The finding that articles identified as post-positivist/critical realist were less likely to include an explicit statement about philosophical positions might also indicate that some post-positive qualitative researchers are apprehensive about explicitly labelling their work as ‘post-positive’. Recent work (Ronkainen, Citation2018; Wiltshire, Citation2018) suggests that researchers may indeed be interested in qualitative approaches grounded in realism and have felt that more interpretive approaches do not meet their research needs. We feel it is important to continue to advocate for all forms of qualitative inquiry, and to be careful about acting as gatekeepers that only advance certain types of qualitative research. By drawing on the concept of methodological coherence in qualitative inquiry, we hope to step away from the notion of ‘paradigm wars’ (Gage, Citation1989) and move to a place of respectful dialogue across philosophical/paradigmatic positions (Given, Citation2017; Shannon-Baker, Citation2016). However, given that interpretive qualitative work has been and continues to be marginalized, many researchers may see this as a provocative topic, particularly within a political environment that emphasizes objective performance criteria and an ‘audit culture’ (Smith & Hodkinson, Citation2005). Rather than encourage the notion of a confrontation between philosophical positions, we echo calls for researchers to appreciate what different forms of qualitative inquiry have to offer (Smith, Sparkes, Phoenix, & Kirkby, Citation2012).

The vast majority of the studies we examined were identified as methodologically coherent, which presents a positive view of the state of the published qualitative sport psychology literature. Our finding is similar to that of Bradbury-Jones et al. (Citation2017), who found that 95% of the articles they reviewed were considered to have a partial or high degree of alignment between the authors’ stated orientation and methods. Thus, our findings also suggest that the published literature in sport psychology reflects a similarly high degree of ‘sophisticated engagement with qualitative approaches and well-described orientations and techniques’ (Bradbury-Jones et al., Citation2017, p. 10). However, it is worth noting that we only reviewed the published peer-reviewed literature, and it is possible that methodologically non-coherent studies do not end up being published. Moreover, studies that are somewhat methodologically coherent might benefit from the peer-review process wherein reviewers identify discrepancies between authors’ stated philosophical positions and the methods and approaches used in their research.

Although only 4% of articles were identified as non-coherent, it is important to note that our coding system could have led to an over-estimation of the number of coherent articles. In some cases, we came across examples of papers that were ‘mostly coherent’ but which lacked some elements that may have better aligned with their stated philosophical position. Additionally, we had to assume the philosophical position if it was not explicitly stated; in these cases it is possible that we may have assumed a different position than the authors thought they were taking. When a philosophical position was not explicitly stated, determinations of the philosophical position in the studies were made based on features of the papers (e.g. the language used by the authors and how the results were presented). Based on these features, we made a determination regarding the position that most likely aligned with these features and the study would then be identified as coherent. It would be interesting to know whether the authors of such papers agreed with our decision about their assumed position. Adopting this approach could have led to a higher number of articles being identified as non-coherent, instead of assuming authors’ philosophical position (i.e. what we did). Reflecting on this issue, the concept of methodological coherence might best be considered on a continuum, rather than as a binary ‘yes/no’. By conceptualizing coherence as a continuum, reviewers, editors, and readers may be more sensitive to the ways in which researchers can maintain coherence, and therefore avoid making a binary distinction about the methodological coherence of a study, which could risk dismissing studies that are deemed non-coherent if some elements in their study seem misaligned.

Overall, we feel that the concept of methodological coherence is useful in providing researchers with a guiding principle for thinking through and designing qualitative studies. However, there are some issues worth considering in applying it within the development and execution of research projects. First, projects that consist of multiple authors who typically adopt different philosophical positions within their work may have difficulty in arriving at a consensus about which position to adopt in a team project. In this case, we would suggest that as researchers develop their study, they engage in project design meetings to specifically consider the various philosophical positions that may inform their work, and which position and methods will enable them to best answer their research questions. Here, we agree with Given (Citation2017) and Shannon-Baker (Citation2016) who suggest that researchers may adopt different philosophical positions depending on the project:

I use a range of qualitative methodologies and methods in my interdisciplinary research, but I also incorporate quantitative designs, where appropriate. In doing so, I know that I am embracing different paradigms and I understand the limitations—and benefits—of that decision. I start with the research questions I wish to explore and then I carefully consider the paradigms, theoretical frameworks, and methodologies that will best support my investigation. I recognize that I am not expert in all approaches and I seek advice (and collaborators) from those who are expert in other paradigms. Only then do I (or we) select the methods and techniques that I (or we) will use “on the ground” to gather data. By starting with an understanding of paradigm, researchers can gain a deeper insight into the purpose and intention of the proposed design. (Given, Citation2017, p. 2)

when multiple analyses are employed with differing associated philosophical assumptions, it becomes even more relevant to articulate how and why findings remain comprehensible. The first task for the pluralistic researcher, therefore, it to understand the epistemological and ontological underpinnings of analytical methods, and the relationship between them. (p. 375)

In the future, there may be greater attention devoted to explicit statements of paradigmatic positioning in qualitative research in sport psychology. For example, some journals, such as JASP, now require authors of qualitative studies to explicitly state their philosophical position: ‘Authors seeking to submit qualitative manuscripts are guided to ensure that within their methodology the epistemological underpinning of the work is clearly stated and the subsequent procedures consider the rigour of the data collection process’ (Mellalieu, Citation2018). This requirement was implemented by JASP in 2018, and we anticipate that it will have a large impact on the number of published articles with a stated paradigmatic position moving forward. The requirement to explicitly state one's philosophical position helps to address issues of methodological coherence within published studies, as it requires researchers submitting qualitative studies to consider how philosophical assumptions influence their research choices, and to demonstrate how their assumptions align with their approach to data collection, analysis, presentation of results, and so on. If researchers are required to consider issues of epistemology and ontology when publishing with JASP they may become more mindful of how these issues underpin their work and may therefore be more likely to consider them when publishing with other journals.

However, we also acknowledge that requiring authors to explicitly state their ontological and epistemological assumptions in qualitative articles may be problematic for at least two reasons. First, for researchers who are not trained in qualitative approaches, they may not appreciate which assumptions they are invoking when they claim a particular philosophical position, or the inherent choices they have made by engaging in certain practices (data collection, analysis) early in the research process. Thus, authors may feel as though they must ‘reverse-engineer’ their qualitative study to claim a philosophical position that they had not considered prior to conducting their research. This may also result in methodologically non-coherent articles because researchers who are unfamiliar with epistemological and ontological ideas may use language to describe the use of research techniques which do not align with their stated philosophical stance. A second issue is that by requiring authors of qualitative studies to explicitly state the assumptions underlying their work, qualitative research approaches continue to be marginalized and the dominance of post-positivist, quantitative research approaches are reinforced. That is, authors of quantitative studies are not required to identify their philosophical positioning, and readers of quantitative research are assumed to be able to interpret quantitative findings. Conversely, authors of qualitative studies seem to be required to demonstrate how their assumptions are represented throughout their manuscript, rather than assuming the readers of qualitative inquiry have the requisite knowledge to act as ‘connoisseurs’ of various forms of qualitative inquiry (Sandelowski, Citation2015; Smith et al., Citation2012). This second problem seems somewhat intractable given that the dominance of post-positivism in sport psychology is not likely to abate in the near future. Nevertheless, we feel that the requirement for authors to explicitly state their assumptions is a positive step forward, as it foregrounds issues of epistemology and ontology, requiring authors to consider whether and how their work is methodologically coherent and aligned with their paradigmatic assumptions at the outset of a study.

The results of the present study should be seen as encouraging, as only 4% of the reviewed articles were identified as methodologically non-coherent. Nonetheless, we felt it was important to comment on some of the main features of studies that were identified as non-coherent, followed by some suggestions for promoting methodological coherence within qualitative research. One of the most common aspects of studies deemed to be methodologically non-coherent was a misalignment between the stated paradigm and the language used throughout their article. Several studies claimed to have conducted a study from a constructivist or constructionist paradigm (thus invoking relativist ontological assumptions), yet the description of the methods and analysis, the presentation of results, and the language used throughout their manuscript appeared to reflect critical realist/post-positivist philosophical positions. For example, claiming to have conducted a study from a constructionist approach yet describing the use of inter-rater reliability ‘to confirm the accuracy of the findings’ or to ‘reach consensus’ between coders would not be methodologically coherent. Similarly, claiming a relativist ontological position with a subjectivist/transactional epistemology and then describing techniques to remove or minimize researcher bias or subjectivity would also not be considered methodologically coherent. We are not suggesting that researchers conducting qualitative studies from relativist positions forego accountability procedures altogether, but rather we suggest that the strategies that researchers use to enhance the quality of their work should be in alignment with their stated philosophical position and their chosen methodological approach. Some strategies that may be used to strengthen the analysis within qualitative inquiry conducted from a relativist philosophical position include engaging participants in member reflections to elaborate on interpretations of the data, as well as using reflexive journaling and conferring with critical friends throughout the research process. We refer the reader to Corbin and Strauss (Citation2008), Burke (Citation2016), Sparkes and Smith (Citation2014), and Smith and McGannon (Citation2018) for further discussion of strategies that researchers can take to enhance the quality of qualitative research.

Another example of some methodologically non-coherent studies was a misalignment between the primary focus of the paper and the stated paradigm. An example here would be the claim that a study was conducted from a constructionist philosophical position, but the analysis and results seemed to focus strictly on individuals’ experiences without reference to broader issues of sociocultural or historical context, or the construction, functions, and uses of narratives or discourses within the analysis or results. Overall, it appeared that the main issues leading to articles being deemed non-coherent or misaligned related to the use of conflicting language throughout the articles that appeared to conflate realist and relativist positions and assumptions.

We also noted aspects of studies that were identified as strong examples of methodologically coherent studies across a range of philosophical positions and using various approaches. Please refer to the Supplementary File for some examples of studies that were identified as being methodologically coherent.

Thoughts on expanding methodological coherence in qualitative inquiry in sport psychology

In conducting this review and discussing these issues as a research team and with colleagues, we were acutely aware of not wanting to be seen as gatekeepers or ‘the methods police’ (Holt & Tamminen, Citation2010). Our intent for undertaking this research was to advance discussions surrounding methodological coherence in qualitative research, and to unpack the implications of positioning qualitative research studies within different philosophical positions. As researchers who have engaged in various qualitative and quantitative studies from multiple philosophical positions, we appreciate the importance of plurality in qualitative inquiry and the value that different types of qualitative studies bring to the field of sport psychology. We also appreciate the daunting nature of embarking on qualitative research amid the current landscape and with so many options to choose from. Thus, based on our review, we propose the following tips and suggestions to help researchers strengthen their studies and to improve the overall methodological coherence of their work:

Methodological coherence is a guiding principle to help researchers make decisions to ensure alignment between their research question, philosophical position, and their methods and strategies for analyzing and presenting the results of qualitative inquiry. Researchers should strive to ensure congruence between their philosophical position and all other aspects of their study (i.e. methodology, methods, approaches to data collection, analysis, interpretation, rigour/trustworthiness, etc.; see Supplementary File for examples of methodologically coherent studies). Do not shy away from explicitly stating your philosophical position and underlying assumptions, as this process can help you to ‘think through’ the methodological decisions you will take when conducting your study.

Language matters. The way that the aims, purposes, and research questions within a study are worded will reflect a particular philosophical position, regardless of whether this position is explicitly stated or not. The way in which elements of a study are described should demonstrate alignment with the explicit or implicit assumptions conveyed in the study. Thus, researchers should use language carefully and thoughtfully when developing a research question or describing the aim or focus of their study (and throughout their entire article). See the Supplementary File for examples of research questions that reflect the different philosophical positions we have discussed.

To strengthen the methodological coherence of a study, researchers must demonstrate the approach they have chosen is the best approach to answer their research question and that their approach aligns with the philosophical position from which they approached their work. Therefore, research questions that reflect a post-positivist or critical realist philosophical position will require the application of research methods that align with this position; conversely, research questions that reflect relativist assumptions will require different approaches to data collection, analysis, and so on. From our perspective, we want to celebrate a diversity of research approaches and we feel there is nothing wrong with conducting research from any particular (realist or relativist) philosophical position. Indeed, the critical issue is for researchers to think deeply about conducting rigorous work from whichever position they assume.

We also strongly advocate for more training and discussion concerning the philosophy of knowledge and the assumptions underlying all forms of inquiry. Researchers should be encouraged to read about different philosophical assumptions, discuss the philosophical assumptions of their research questions with their colleagues, qualitative methods classes and seminars, or hold monthly discussion groups to foster dialogue. Other opportunities for training and discussion may occur through workshops (e.g. Burns, Macdonald, & Carnevale, Citation2018; Tamminen et al., Citation2018), by becoming involved with qualitative research centres or institutes, or by attending conferences such as the International Conference on Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise. Through these approaches, we encourage researchers to consider and appreciate the variety of ways in which knowledge can be generated and contribute to understanding people's experiences in sport. See the Supplementary File for a list of additional resources (e.g. additional readings, names of qualitative research centres, and qualitative conferences).

Limitations

One limitation of the present review was the exclusion of studies from exercise psychology. Future reviews should consider including exercise psychology studies to shed additional light on trends in philosophical positions across the two disciplines. An additional limitation of this study was that we did not examine trends in the use of specific methodologies, modes of data collection and analysis, and issues of trustworthiness and rigour. We decided against covering those topics in this paper because they have been the focus of previous reviews in sport psychology. For example, methodologies and methods of data collection/analysis were addressed in reviews by Culver and colleagues (Citation2003, Citation2012), as were issues of trustworthiness and rigour (e.g. Eakin & Mykhalovskiy, Citation2003; Smith & McGannon, Citation2018; Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). The fact that the language used in the research questions of the reviewed studies were not explicitly coded may also been seen as a limitation. Although we did read each of the research questions, they were not included in the coding sheet. Future research on methodological coherence should include the language of the research questions in their coding sheet. A final limitation was that some members of our coding team consisted of research assistants who had limited experience with qualitative inquiry in sport psychology. Although we attempted to address this limitation by conducting benchmarking sessions with all the coders and encouraged them to flag ‘unsure’ articles so the authorship team could review them, we acknowledge the possibility of variability between coders. The double-coding of a random selection of articles does, however, provide some confidence in the coding.

Conclusion

In this review, we have identified trends in qualitative sport psychology publications across five journals over a 30-year period and we found notable changes in the uses of various philosophical positions over time. We also examined the methodological coherence (Mayan, Citation2009) of qualitative studies. We reiterate the suggestion that methodological coherence offers researchers a useful way to think through and design rigorous qualitative research. We found that 96% of qualitative publications across five of our field's leading peer-reviewed outlets were methodologically coherent. The primary issue we identified in methodologically non-coherent articles was related to the use of language (e.g. articles that used language consistent with realist philosophical assumptions, despite authors’ claims that they had approached their study from a relativist position). Based on our review, we have attempted to offer suggestions that can improve the methodological coherence of qualitative research. Ultimately, we encourage diversity in qualitative inquiry, and hope that our review contributes to ongoing discussions of quality and rigour in qualitative research in the field of sport psychology.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (739.3 KB)Acknowledgements

Thank you our research assistants at McGill University (Evan Bishop, Kaila Bonnell, Melissa Daoust, Carly Ede, Zachary Hazan, Joshua Ruether, and Jean-Daniel Vallières) and University of Toronto (Asma Khalil, and Jasmine Romero) for their assistance with this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The term realism has historically been associated with the philosophical position of positivism, which can be described as holding a naïve realist ontological position that assumes the existence of an external, independent reality that is completely apprehendable. However, positivism and its naïve realist ontological assumptions have been described as ‘a package of philosophical ideas that most likely no one has ever accepted in its entirety’ (Paley, Citation2008, p. 646). As such, the term ‘realism’ is now sometimes used to refer to the assumption that one universal reality or ‘truth’ exists independent of the individual, but it may never be fully understood due to unknown variables within nature and uncertainty in measurement (e.g. Archer et al., Citation2016; Wiltshire, Citation2018). Elsewhere, the term ‘critical realism’ is used to describe the same assumptions and to more clearly contrast it with the naïve realist assumptions of positivism, by indicating a ‘critical’ view of realism and the extent to which reality is apprehendable (Lincoln et al., Citation2018, p. 511, Table 5.5; Tamminen & Poucher, Citationin press).

2 In the current paper, we use the terms post-positivism and critical realism to refer to the same or similar philosophical positions, as the use of these terms in the sport psychology literature appear to be referring to shared views of ontological and epistemological assumptions and processes for conducting research. Clark (Citation2008) described critical realism as ‘one of a range of post-positivist approaches positioned between positivism/objectivism and constructivism/relativism. Critical realism simultaneously recognizes the existence of knowledge independent of humans but also the socially embedded and fallible nature of scientific inquiry’ (p. 167). The ontological and epistemological assumptions of post-positivism have also been described in a similar manner:

the concept of an absolute truth may be seen as an aspiration rather than as something that can be discovered once and for all … in post-positivism the role of the researcher as interpreter of data is fully acknowledged, as is the importance of reflexivity in research practice. (Fox, Citation2008, p. 660)

References

- Archer, M., Decoteau, C., Gorski, P., Little, D., Porpora, D., Rutzou, T., … Vandenberghe, F. (2016). What is critical realism? Perspectives, 38(2), 4–9.

- Bradbury-Jones, C., Breckenridge, J., Clark, M. T., Herber, O. R., Wagstaff, C., & Taylor, J. (2017). The state of qualitative research in health and social science literature: A focused mapping review and synthesis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20, 627–645. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1270583

- Brustad, R. J. (2008). Qualitative research approaches. In T. Horn (Ed.), Advances in sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 31–44). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Burke, S. (2016). Rethinking ‘validity’ and ‘trustworthiness’ in qualitative inquiry: How might we judge the quality of qualitative research in sport and exercise sciences? In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 330–339). London: Routledge.

- Burns, V. F., Macdonald, M. E., & Carnevale, F. A. (2018). Epistemological oppression and the road to awakening: A boot camp, a Twitter storm, and a call to action! International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17, 1–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918763413

- Clark, A. (2008). Critical realism. In L. Given (Ed.), The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 168–170). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Clarke, N. J., Caddick, N., & Frost, N. (2016). Pluralistic data analysis: Theory and practice. In A. Sparkes & B. Smith (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 368–381). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Criteria for evaluation. In Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 297–312). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Culver, D. M., Gilbert, W., & Sparkes, A. (2012). Qualitative research in sport psychology journals: The next decade 2000–2009 and beyond. The Sport Psychologist, 26, 261–281. doi: https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.26.2.261

- Culver, D. M., Gilbert, W. D., & Trudel, P. (2003). A decade of qualitative research in sport psychology journals: 1990–1999. The Sport Psychologist, 17, 1–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.17.1.1

- Eakin, M., & Mykhalovskiy, E. (2003). Reframing the evaluation of qualitative health research: Reflections on a review of appraisal guidelines in health sciences. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 9(2), 187–194. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00392.x

- Fox, N. J. (2008). Postpositivism. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 659–664). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Gage, N. L. (1989). The paradigm wars and their aftermath: A “historical” sketch of research on teaching since 1989. Educational Researcher, 18(7), 4–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018007004

- Gibson, K. (2016). Mixed methods research in sport and exercise: Integrating qualitative research. In A. Sparkes & B. Smith (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 382–396). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Given, L. (2017). It’s a new year … so let’s stop the paradigm wars. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16, 1–2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917692647

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26, 91–108. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1998). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research: Theories and issues (pp. 195–220). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 191–215). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Holt, N. L., & Tamminen, K. A. (2010). Improving grounded theory research in sport and exercise psychology: Further reflections as a response to Mike Weed. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11, 405–413. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.12.002

- Lincoln, Y. S., Lynham, S. A., & Guba, E. G. (2018). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 108–150). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mayan, M. J. (2009). Essentials of qualitative inquiry. New York, NY: Left Coast Press.

- Mellalieu, S. (2018). Editorial. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30, 1–2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1414513

- Morse, J. M. (1999). Qualitative generalizability. Qualitative Health Research, 9, 5–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/104973299129121956 doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/104973299129121622

- Paley, J. (2008). Postpositivism. In L. Given (Ed.), The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 647–650). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ronkainen, N. (2018, June). If this is just your reality, why should I believe you?: Exploring challenges in the social constructionist perspective on research quality. Oral presentation at the International Conference on Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, Vancouver, BC.

- Sandelowski, M. (2015). A matter of taste: Evaluating the quality of qualitative research. Nursing Inquiry, 22, 86–94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12080

- Shannon-Baker, P. (2016). Making paradigms meaningful in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10(4), 319–334. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815575861

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11, 101–121. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Smith, B., Sparkes, A. C., Phoenix, C., & Kirkby, J. (2012). Qualitative research in physical therapy: A critical discussion on mixed-method research. Physical Therapy Reviews, 17, 374–381. doi: https://doi.org/10.1179/1743288X12Y.0000000030

- Smith, J. K., & Hodkinson, P. (2005). Relativism, criteria, and politics. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 915–932). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Sparkes, A. C. (1998). Validity in qualitative inquiry and the problem of criteria: Implications for sport psychology. The Sport Psychologist, 12(4), 363–386. doi: https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.12.4.363

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2009). Judging the quality of qualitative inquiry: Criteriology and relativism in action. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(5), 491–497. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.02.006

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health from process to product. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Tamminen, K. A., & Poucher, Z. A. (2018). Open science in sport and exercise psychology: Review of current approaches and considerations for qualitative inquiry. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 36, 17–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.12.010

- Tamminen, K. A., & Poucher, Z. A. (in press). Research philosophies. In D. Hackfort & R. Schinke (Eds.), The Routledge international encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Tamminen, K. A., Poucher, Z. A., Sweet, S. N., & Caron, J. G. (2018). Methodological coherence in qualitative research. Workshop presented at the Canadian Society for Psychomotor Learning and Sport Psychology (SCAPPS) Conference, Toronto, ON.

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Wiltshire, G. (2018). A case for critical realism in the pursuit of interdisciplinarity and impact. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10, 525–542. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1467482