ABSTRACT

Parent-education programs in youth sport appear to provide an appropriate avenue to facilitate healthy parental involvement, enhance positive parental support, and help to relieve stressors placed on parents, coaches, and youth athletes. However, little is known about the efficacy, design, and evaluation methods utilized in parent-education programs in the youth sport context. The aims of the present systematic review were to examine: (1) the outcomes of parent-education programs which target psychosocial parental support; (2) the theoretical underpinnings of parent-education programs; and (3) measures utilized to evaluate parent-education programs in youth sport. A total of 12 articles met the inclusion criteria. All five quantitative studies yielded significant results. All three qualitative studies reported improvements in parents’ knowledge and skills. Only one mixed-methods study reported a significant result, however, qualitative data suggested positive changes in parent-athlete relationships. An examination of underlying theoretical frameworks revealed five studies (42%) explicitly stated how theory informed their interventions. Finally, there was an absence of sport-specific measures utilized to evaluate changes in parents’ behavior and involvement. Future researchers should consider adopting behavior change theories when designing and implementing parent-education programs, and seek to utilize validated sport-specific measures to examine changes in parents’ behaviors within the sporting context.

The social support system in youth sport is made up of multiple stakeholders, such as coaches, parents, siblings, teammates, and sport officials (Dorsch et al., Citation2020; Jowett & Timson-Katchis, Citation2005). Parents are considered one of the more significant and influential members within this network (Stein et al., Citation1999), as they are a fundamental component of the youth sport system (Dorsch, Citation2017). Youth sport participation is predominately facilitated by parents, as they initiate children’s involvement in sport (Côté, Citation1999) and provide them with the resources and support (i.e. practical, emotional, and financial) necessary to participate (Harwood & Knight, Citation2015). Parents also play a critical role in interpreting values and communicating life and sport skills to athletes (Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2004). By taking on such an all-encompassing role, parents are equipped with infinite opportunities to either positively or negatively influence their youth athlete’s sporting experience.

The wide array of support provided by parents, such as informational support (e.g. provision of information regarding competitions and training), practical support (e.g. logistical and financial assistance), and emotional support (e.g. demonstrating understanding and unconditional love) plays a critical role in the development of youth athletes and has been linked to enhanced enjoyment, self-confidence, and perceived competence in youth athletes (Baker et al., Citation2003; Leff & Hoyle, Citation1995; Power & Woolger, Citation1994). Similarly, autonomy-supportive parenting styles, such as promoting personal autonomy, supporting decision making, and providing appropriate structure allows for more positive outcomes among athletes, such as increased motivation and satisfaction (Gagné, Citation2003; Holt et al., Citation2009; Juntumaa et al., Citation2005).

Despite most parents providing appropriate support and having a positive influence on their children’s sporting experience, there remains a minority of parents who exhibit parental pressure and inappropriate behaviors (Dorsch et al., Citation2015; Kidman et al., Citation1999; Knight, Citation2019). Gould et al. (Citation2006) examined coaches’ perceptions of parental behaviors in junior tennis. The authors reported that while 59% of parents were seen to have a positive influence on their youth athlete’s sporting development, 36% of parents were perceived as having a negative influence. Negative parent behaviors included over-emphasizing winning, having unrealistic expectations, and criticizing the athlete (Gould et al., Citation2006). Observational research conducted by Holt et al. (Citation2008) provides further support, whereby they reported negative and derogatory comments accounting for approximately 15% of the comments directed at athletes. Such pressure often results in reduced enjoyment, increased levels of amotivation, and heightened anxiety (Bois et al., Citation2009; O’Rourke et al., Citation2011; Sánchez-Miguel et al., Citation2013).

However, Knight and Newport (Citation2017) highlighted that parenting in sport is a much more complex process than knowing how and when to provide support. Early research in the area of parental involvement in youth sport, focused on the unidirectional influence of parents on their children’s sport participation (Greendorfer, Citation1992). However, the research progressed and adopted a more parent-focused approach. For example, Snyder and Purdy (Citation1982), Weiss and Hayashi (Citation1995), and Dorsch et al. (Citation2009) have demonstrated the bi-directional and reciprocal influence of parents and athletes on socialization in sport, whereby athletes are not only influenced by parents, but also influence their parents’ thoughts and behaviors. In recent years, researchers have continued to adopt this parent-focused approach, whereby they sought to understand sport parents’ experiences and stressors (e.g. Clarke & Harwood, Citation2014; Harwood et al., Citation2010; Harwood & Knight, Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Thrower et al., Citation2016). Harwood and Knight (Citation2009b) examined stressors experienced by tennis parents across different development stages and identified that parents experienced a range of organizational (e.g. finance, time, governing body systems), competitive (e.g. athlete’s behavior and performance), and development stressors (e.g. athlete’s education and future). Similarly, Thrower et al. (Citation2016) examined British tennis parents’ education and support needs, which demonstrated the importance of providing parents with education that again addresses their introductory, organizational, developmental, and competitive needs. The results from these studies highlight that despite best intentions, parents are sometimes unaware of how to optimally support their youth-athletes.

The most recent developments in the area of parental involvement in youth sport have seen the introduction of parent-education programs and interventions, which appear to provide an appropriate avenue to both reduce inappropriate parental involvement and improve athlete outcomes by alleviating some of the stressors experienced by parents, coaches, and youth athletes. The aims of such programs were to promote and enhance positive parental involvement in youth sport to facilitate a positive youth sport environment (e.g. Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Tamminen et al., Citation2020; Thrower et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). Dorsch et al. (Citation2017) developed, implemented, and evaluated an evidence-based education program for American youth soccer parents. The program included a 22-page Sport Parent Guide, and a 45-minute Sport Parent Seminar, both of which detailed evidence-based tips and strategies for parenting in youth sport. Content included topics such as youth sport participation, athlete development, communication strategies, working with coaches, and positive sport parenting. Furthermore, Thrower et al. (Citation2017) implemented an evidence-based education program designed to meet the needs of British tennis parents. The program educated parents on topics such as supporting your child during mini-tennis, the Lawn Tennis Associations’ mini-tennis organizational system, child and talent development, and competition roles. Results illustrated that these interventions have had a positive impact, improving parents’ perceived knowledge and attitudes (Thrower et al., Citation2017), with children also reporting higher perceptions of competence, and lower levels of stress (Dorsch et al., Citation2017). However, despite the apparent positive impact of such programs in several sporting contexts, there has been no systematic review conducted which utilizes a rigorous research methodology to evaluate and appraise the impact of parent-education programs within youth sport. This is surprising given that parent-education programs are the primary tool to promote positive parental support.

Further, while parent-education programs offer opportunities to improve parental involvement and enhance positive parental support to facilitate adaptive athlete outcomes, very little is known about the theoretical underpinnings used to design and implement such programs. Researchers in the field of sport and exercise psychology have expressed their concerns at the lack of rigorous intervention research designs within the field (Schinke et al., Citation2020). An important component of rigorous intervention design is the inclusion of a theoretical underpinning. However, Prestwich et al. (Citation2014) have previously highlighted that many interventions do not utilize theory in their design or evaluation. Moreover, when theory is mentioned, it is not applied extensively. Parent-education programs in youth sport appear to provide an appropriate method to improve positive parental involvement, and address the demands faced by parents of youth athletes. However, examining if such programs have been guided by an underlying theoretical framework appears pertinent, given the noted lack of rigorous intervention research design within the discipline.

Moreover, clear challenges remain when attempting to successfully examine the effectiveness of such sport-parenting interventions. Knight (Citation2019) states that issues remain in examining the effectiveness of these interventions, as ‘currently, there are few validated, theory-grounded measures available, that can be used to specifically examine changes in parents’ involvement, behaviour, or attitudes’ (p. 256). Thrower et al. (Citation2017) further supported this claim by suggesting that future researchers should draw on measures which evaluate the domain of learning targeted.

The absence of research examining parent-education programs in youth sport provides a strong rationale for the completion of a systematic review, which utilizes a rigorous research methodology to identify, appraise, and synthesize all parent-education programs within the field. Through conducting a systematic review, the aims were to examine: (1) the outcomes of parent-education programs which target psychosocial parental support; (2) the theoretical underpinnings of parent-education programs in youth sport; and (3) measures utilized to evaluate parent-education programs in youth sport. By gaining a greater understanding of the design, efficacy, and evaluation methods utilized in existing parent-education programs, researchers and practitioners may adopt such findings to improve the application of future parent-education programs.

Method

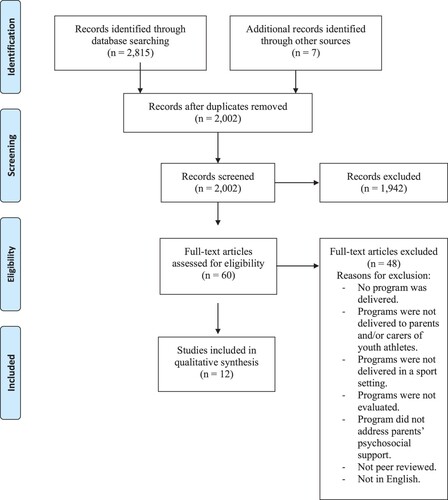

The present study utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Citation2021). Following these guidelines, the protocol for the present systematic review which details the research questions, search strategy, and inclusion criteria, was published on the Open Science Framework (ID Number: NB5H4), to enhance the transparency of the research process (Gunnell et al., Citation2020).

Together with the University’s subject librarian, pertinent sport and exercise psychology journals, and relevant terms and key words were identified. An electronic search was carried out using the following databases: (1) PsychInfo; (2) Scopus; (3) SportDiscus; and (4) Web of Science. Each database was searched from its year of inception to the 25th May 2020. The electronic search strategy contained the use of appropriate Boolean operators, truncations, wildcards, and proximity searches, all of which were modified for each database. The key words utilized can be viewed on the registered protocol. Further, reference lists of eligible papers were also searched to identify any additional relevant articles. To conclude the search, manual searches of sport and exercise psychology journals, were also carried out, to ensure that no eligible papers were overlooked.

The inclusion criteria for this review are detailed in . Participants included parents and/or carers of youth athletes aged between 5 and 18 years. The exposure or intervention was parent-education programs, which aimed to enhance parents’ knowledge of positive psychosocial parental support. Parent-education programs conducted in a youth sport setting only were included. For the purpose of this review, Loy’s (Citation1968) definition of sport was adopted which is described as ‘competition whose outcomes is determined by physical skill, strategy, or chance employed singly or in combination’ (p. 1). Consequently, parent-education programs where the focus was not on improving parents’ knowledge of psychosocial parental support (e.g. concussion parent-education), or programs which were not conducted in a sport setting (e.g. physical activity or leisure setting) were excluded. Although studies were limited to sport-based parent-education programs, no context limitation was applied in terms of delivery method. For example, individual and group interventions in a variety of environments (e.g. online and face-to-face) were included.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria.

There were three primary outcomes of interest for this review, which sought to examine aspects of design, evaluation, and effectiveness of the included papers; (1) the outcomes of parent-education programs which target psychosocial parental support in youth sport; (2) the theoretical underpinnings of parent-education programs in youth sport; and (3) measures utilized to evaluate parent-education programs in youth sport. Given the anticipated scarcity of parent-education programs in youth sport, it was expected that the number of parent-education programs which applied a randomized control design would be limited, therefore no limitation was placed on study design. However, included papers were limited to peer-reviewed publications in English only. Therefore, abstracts, book chapters, conference proceedings, review papers, grey literature including non-peer reviewed papers, Masters theses, and PhD dissertations were all excluded.

Utilizing the search strategy developed in consultation with the University’s subject librarian, a search of the chosen electronic databases (i.e. PsychInfo, Scopus, SportDiscus, and Web of Science) was conducted in May 2020. Results were exported to the selected citation management database, RefWorks, where duplicates were removed in line with PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., Citation2021). Upon completion of the removal of duplicates, the complete database of citations was exported to a Microsoft Excel file, for title and abstract screening. Title and abstract screening were carried out by one member of the research team, to identify potentially relevant papers. This phase included reading the title and abstracts of all the articles retrieved from the search, screening them systematically and selecting those that met the inclusion criteria. Having completed title and abstract screening, the full-text screening was independently completed by all four members of the research team. This phase included reading and screening the full text of all remaining articles for eligibility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Each member of the research team utilized a standardized screening template. Discrepancies in results were resolved through discussion. For example, there was some disagreement around the inclusion of parent-education programs which targeted mental health literacy. However, following discussions it was agreed that such programs did not meet the inclusion criteria. For each paper that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria, a rationale for omission was provided.

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., Citation2018) was employed to assess study quality. The MMAT was designed for the critical appraisal of systematic reviews, which include qualitative research, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, quantitative descriptive, and mixed method studies. Given the diversity of methods employed across the included papers, the MMAT was deemed an appropriate quality assessment tool for this review. The first phase of quality assessment when using the MMAT asks two questions, irrespective of study design: (1) Are there clear research questions? And (2) Do the collected data address the research questions proposed? The second phase of appraisal then further reviews the methodological quality using criteria specific to the research design. Each criterion is scored with a ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘can’t tell’. Given the critical appraisal process is somewhat subjective, the MMAT (Hong et al., Citation2018) suggests that at least two reviewers should independently complete the appraisal process. Accordingly, two members of the research team independently conducted the quality assessment of the included articles. An agreement score of 89% was reached before discussion, with a 100% agreement rate post-discussion. Within the MMAT, the first screening question asks ‘are there clear research questions?’. Many of the included papers in this review listed research aims rather than questions, and so much of the disagreement centered around the scoring of the first screening question. However, having sought clarification from the authors of the MMAT tool, the research team made the decision to treat research aims and questions similarly.

Upon completion of the quality assessment, data extraction was completed. To guide this process, a data extraction sheet was developed which included study information, such as title, author, and year of publication. Further, the data extraction form included information related to study characteristics (i.e. aims and objectives, study design, location, method of recruitment, intervention description, duration, and frequency). Additionally, the data extraction sheet also included demographic information (i.e. number of participants, age, gender, sport type, and level of sport) and information pertinent to the outcomes of this review, such as the effectiveness of the parent-education programs (i.e. time points measured, change from baseline), theoretical underpinnings, and finally measures used to evaluate the programs (i.e. type of measure, reliability, and validity of measure).

A narrative synthesis of the findings is reported below. Ryan (Citation2013) suggested that narrative synthesis of results is often appropriate when analyzing data from different study designs, which cannot be subject to a meta-analysis. Given the diversity of study designs utilized in the included papers (i.e. qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods), a narrative synthesis was deemed most appropriate.

Results

The electronic search of databases resulted in a total of 2,815 articles (870 from PsychInfo; 610 from Scopus; 554 from SportDiscus; and 781 from Web of Science). A further seven pertinent articles were identified through additional sources (i.e. reference lists and journals). Upon removal of duplicates (820), 2,002 citations remained which were subject to title and abstract screening. Following, 1,942 articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. This resulted in 60 full-text articles being assessed for eligibility. A further 48 articles were excluded upon completion of full-text screening. Reasons for exclusion are detailed in . For example, parent-education programs not delivered in a sport setting, or parent-education programs which did not target psychosocial parental support were excluded. A total of 12 articles met the inclusion criteria following full-text screening, which included two studies identified through additional sources (i.e. reference lists and journals). A qualitative synthesis of these studies is presented below.

Quality assessment

The results of the quality assessment are detailed in . Four studies met 100% of the criteria (Ford et al., Citation2012; Lisinskiene & Lochbaum, Citation2019; McMahon et al., Citation2018; Thrower et al., Citation2017) and three studies met 80% of the criteria assessed (Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Sampol et al., Citation2019; Smoll et al., Citation2007). Three studies (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020; Harwood & Swain, Citation2002; Thrower et al., Citation2019) met 60% of the criteria, one study (Tamminen et al., Citation2020) met 40% of the criteria, and one study (Richards & Winter, Citation2013) met 20% of the criteria. For the mixed-methods studies, Hong et al. (Citation2018) suggested that the overall quality of a study, cannot exceed the quality of its weakest component. These criteria were applied to all mixed-method studies included in this review.

Table 2. Quality assessment.

Study characteristics

In this section a descriptive overview is provided of the parent-education programs included in this review. Of the 12 papers, three were qualitative (Lisinskiene & Lochbaum, Citation2019; McMahon et al., Citation2018; Thrower et al., Citation2017), five were quantitative (Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Ford et al., Citation2012; Sampol et al., 2019; Smoll et al., Citation2007; Tamminen et al., Citation2020), and four were mixed methods (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020; Harwood & Swain, Citation2002; Richards & Winter, Citation2013; Thrower et al., Citation2019).

The included papers had parent-education programs across a range of sports including soccer (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020; Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Sampol et al., 2019), tennis (Harwood & Swain, Citation2002; Thrower et al., Citation2017, Citation2019), and ice-hockey (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020; Tamminen et al., Citation2020). It is important to note that Ford et al. (Citation2012) did not state the sport in which the education program was delivered. Similarly, these programs were delivered across a range of countries, including Canada (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020; Tamminen et al., Citation2020), the United States (Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Ford et al., Citation2012; Smoll et al., Citation2007) and the United Kingdom (Harwood & Swain, Citation2002; Richards & Winter, Citation2013; Thrower et al., Citation2017, Citation2019).

Looking more specifically at content, these programs sought to educate parents across a variety of topics, such as athlete development (4); abuse (3); communication styles and/or strategies (6); children’s needs (3); developing safe environments (1); establishing and maintaining relationships (5); injury management (1); managing expectations and misplaced enthusiasm (1); motivational climate and/or achievement goals (3); parental behaviors (8); types of parent involvement and/or support (3); the role and importance of parents (3); the role and importance of coaches (3); and reasons for participation (2). The duration and frequency of programs ranged from 25 minutes with one online-education module (Ford et al., Citation2012) to 12 months, consisting of 12, 60-minute theory classes once a month (Lisinskiene & Lochbaum, Citation2019). Of the 12 included studies, seven papers implemented a short, one off education workshop or seminar, accompanied by supplementary materials such as information guides, reflective practice, or practical tasks (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020; Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Ford et al., Citation2012; McMahon et al., Citation2018; Sampol et al., Citation2019; Smoll et al., Citation2007; Tamminen et al., Citation2020). The remaining five studies implemented multiple education workshops (2–12 sessions), also accompanied again by a combination of information booklets, practical tasks, and journal articles (Harwood & Swain, Citation2002; Lisinskiene & Lochbaum, Citation2019; Richards & Winter, Citation2013; Thrower et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). Of the 12 included studies, three parent-education workshops were delivered online (Ford et al., Citation2012; Tamminen et al., Citation2020; Thrower et al., Citation2019). The remaining nine parent-education programs were delivered in person, face-to-face.

Sample sizes ranged from 14 (McMahon et al., Citation2018) to 366 participants (Tamminen et al., Citation2020) (see ). However, the total number of participants across all included studies remains unclear, due to the lack of transparency in the reporting of a sample size by Sampol et al. (Citation2019). Attendance rates were noted as a limitation across three studies. For example, Thrower et al. (Citation2017) invited 150 British tennis parents to participate in a parent-education program, designed to meet their needs. Over the course of the study, 31 parents attended at least one workshop. However, only two parents completed all seven workshops, with 22 parents completing four or more. Further, only 19 parents participated in post-program focus groups, to evaluate the effectiveness of the program. Similarly, Thrower et al. (Citation2019) reported that while 38 parents provided consent and completed pre-program questionnaires, only 13 parents completed post-program evaluation measures. Further, Azimi and Tamminen (Citation2020) provided a program to parents of 10 athletes. The small number of participants may have prevented the data from yielding statistical significance in the results.

Table 3. Study characteristics.

Outcomes of programs

The impact and outcomes of the included parent-education programs were examined (see ). All five quantitative studies, which all included pre- and post-program evaluation methods reported significant changes. Dorsch et al. (Citation2017) utilized repeated measures analyses of variance to examine the equality of variable means for participants across three conditions (full, partial, and non-implementation) at two time points (pre- and post-program). Results indicated a significant group × time interaction for Parental Support (F(2, 54) = 7.08, α = .002); Parental Pressure (F(2, 54) = 12.87, α < .001); Parent–Child Warmth (F(2, 54) = 4.99, α = .010); Parent–Child Conflict (F(2, 54) = 3.27, α = .046); Child Enjoyment (F(2, 54) = 4.40, α = .017); Child Competence (F(2, 54) = 3.85, α = 0.27); and Child Stress (F(2, 54) = 6.66, α = .003). Ford et al. (Citation2012) reported a significant increase in parents’ sportspersonship behaviors from pre- to post-test (t(94) = 3.84, p = .000, d = .433). Sampol et al. (Citation2019) also reported a significant decrease in negative parental comments for the experimental group (t = 3.145, p = .026), however no significant changes were reported for positive and neutral parental comments from pre- to post-program.

Table 4. Outcomes and theoretical underpinnings of programs.

Smoll et al. (Citation2007) revealed significant reductions for the experimental group in overall sports anxiety (t = 3.24, p = .001), somatic anxiety (t = −3.35, p = .001), worry (t = −2.34, p = 0.21), and concentration disruption (t = −2.56, p = .011), when compared to the control group. Finally, Tamminen et al. (Citation2020) reported that athletes in leagues that had implemented the program showed fewer antisocial behaviors toward opponents over time (β10 = −0.37, p = .047). Further, analyses indicated significant differences (F(3, 328) = 2.68, p < .05, η2 = .02) in prosocial behaviors toward teammates between athletes in leagues which had implemented the parent-program at different time points. Post-hoc results indicated that athletes in leagues which had implemented the program for a longer period of time showed improvements in prosocial behaviors toward teammates, however these differences were only marginally significant, Tukey’s p = .08. Lastly, there was a non-significant trend among athletes in leagues which had implemented the program whereby they reported more opportunities to develop personal and social skills. There were no significant differences in parental support and pressure, opportunities for goal setting or initiative, perceived negative experiences, and enjoyment and commitment.

One mixed-methods study reported no significant changes from pre- to post-program (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020). Harwood and Swain (Citation2002) adopted an idiographic approach, whereby they combined individual case studies with multiple baseline design features and cross-case analyses to examine intraindividual changes in achievement goal involvement responses. They reported that participants in the experimental group showed increases in self-directed task involvement, composite self-regulation, self-efficacy, and reductions in social approval ego involvement. Interestingly, all participants in the experimental group either maintained or increased task orientation and maintained or decreased ego orientation, while the control participant reported decreases in task orientation. Further, qualitative findings reported that all participants felt the support they received from their parents played an important role in their improvements and reported that the importance they placed on personal performance and winning had changed for the better. Additionally, all parents noted positive changes in their relationship with their child, for example one parent noted being able to talk more openly to their child-athletes. Richards and Winter (Citation2013) implemented a post-intervention program evaluation form. Results indicated that 100% of parents found the program very useful, while 75% of parents indicated that they would use the strategies provided. Further, qualitative findings suggest that the program improved parents’ knowledge of the benefits of task orientation, helped parents to see issues from their child’s perspective, and raised parents’ awareness of the impact of inappropriate reactions.

Thrower et al. (Citation2019) reported significant improvements in Parent-Parent Relationship Efficacy (t(12) = −3.53, p = .004), however there were no significant changes for any of the other variables measured (i.e. emotional experiences, task and ego goal orientations, tennis parent efficacy). Thrower et al. (Citation2019) did highlight however, that the lack of significant changes may be a result of the low number of participants who completed pre- and post-program questionnaires. Qualitative results highlighted that the online program was more accessible to parents, and that the design of the online program improved the efficacy of the intervention.

Results from the qualitative findings demonstrated how programs allowed parents to develop new skills and acquire new knowledge. Lisinskiene and Lochbaum (Citation2019) reported that the educational component of the intervention allowed parents to develop new skills and understanding such as communication and social skills. The program also allowed parents to gain new knowledge such as positive sport parenting strategies and perceptions of positive and negative youth sport parenting. Similarly, Thrower et al. (Citation2017) noted improvements in parents’ knowledge, as parents reported an improved understanding of tennis, the youth sport environment, and children’s psychosocial needs. The program also enabled change in parents’ attitudes, beliefs, and values in relation to their own reasons for involvement, the goal of junior tennis, and causes of stress among junior tennis players. Lastly, the program was effective in improving parents’ behaviors, such as communication skills. Following the delivery of a narrative pedagogy parent-education program, McMahon et al. (Citation2018) also reported that parents were able to identify unacceptable coaching practices in youth sport.

Theoretical underpinning

Given the lack of rigorous research intervention design within the field of sport and exercise psychology (Schinke et al., Citation2020), the theoretical underpinnings of each of the included interventions were examined, which yielded a variety of results. Smoll et al. (Citation2007) translated theoretical principles of Achievement Goal Theory (i.e. task mastery-involving motivational climate; Nicholls, Citation1984) into a practical and educational approach to reduce anxiety among athletes. The education program promoted a task mastery-involving motivational climate which placed an emphasis on giving maximum effort, individual improvement, and enjoyment. Further, Harwood and Swain (Citation2002) translated factors which underpin the socialization of goal orientations and the activation of task and ego involvement (Harwood & Swain, Citation2002) into a series of athlete, parent, and coach intervention techniques, in order to improve athletes’ task and ego orientations.

Thrower et al. (Citation2017) and Thrower et al. (Citation2019) also made references to theory in the development and implementation of their interventions. The Loughborough Tennis Parent- Education Program (Thrower et al., Citation2017; Thrower et al., Citation2019) was adopted from a grounded theory of British tennis parents’ needs and other relevant tennis parent literature (Harwood & Knight, Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2015; Knight & Holt, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Thrower et al., Citation2016). The grounded theory highlighted the importance of providing tennis parents with education that addresses their introductory, organizational, developmental, and competition needs, across two development stages. Further, the theory notes the importance of on-going support and a supportive learning environment, when addressing parents support needs. Thrower et al. (Citation2017) and Thrower et al. (Citation2019) provided education sessions, each one addressing the needs of parents (i.e. introductory, organizational, developmental, and competition needs) outlined in the grounded theory. Both programs concluded with a workshop which helped parents to identify their social support network and provided information about developing and maintaining healthy relationships. These concluding sessions satisfied the importance of providing parents with on-going support, an important component of the theory. Azimi and Tamminen (Citation2020) utilized evidence-based research to educate parents regarding positive parental involvement and support in the youth sport setting, athletes’ preferences for parental behaviors, athlete development, and parent–child communication in and out of sport. However, Azimi and Tamminen (Citation2020) also incorporated Gibbs (Citation1988) reflective cycle to enhance parents’ awareness of their communication with their children, in the youth sport context.

McMahon et al. (Citation2018) utilized narrative pedagogy as a tool to educate parents about abuse in sport. Within the paper, McMahon et al. (Citation2018) made reference to narrative pedagogy being based on a theory of social constructivism, whereby knowledge is gained through the reciprocal sharing of stories. One could argue that narrative pedagogy is an education tool, grounded in social constructivism. However, Nelson et al. (Citation2016) identified narrative pedagogy as a modern theory of learning and social interaction in itself. Although McMahon et al. (Citation2018) make reference to narrative pedagogy being based on a theory of social constructivism, it remains unclear which theory of social constructivism was utilized.

Dorsch et al. (Citation2017) utilized Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation2005) ecological theory to guide their hypothesis. They claimed that parents who are provided with an evidence-based education program will alter their behavior in order to strengthen parent–child relationships and enhance children’s experiences in sport. Despite Dorsch et al. (Citation2017) reporting that Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation2005) Ecological Theory guided their hypotheses, it is unclear if this theory was used to help guide the development and implementation of the program. Similarly, Lisinskiene and Lochbaum (Citation2019) sought to improve parent–child attachment in youth sport through utilizing Bowlby’s Attachment Theory (Bowlby, Citation1988). However, they too failed to report if this theory was used to guide the development of the program.

The remaining four studies did not make any reference to theory in the development or implementation of their programs (Ford et al., Citation2012; Richards & Winter, Citation2013; Sampol et al., 2019; Tamminen et al., Citation2020). However, the aim of Richards and Winter (Citation2013) was to enhance parents’ knowledge and awareness of their child’s goal orientation and to provide parents with effective strategies to modify and create a motivational climate which fosters high task orientation. Therefore, it could be argued that Achievement Goal Theory (Nicholls, Citation1984) did play a role in the development and implementation of the intervention.

Evaluation measures

provides an overview of the measures used to evaluate the included studies. A total of 25 different assessment tools were utilized across the nine quantitative and mixed-method studies. The Parental Involvement in Activities Scale (PIAS; Anderson et al., Citation2003) was the most frequently used tool, which examined changes in parental support and pressure displayed by parents pre- and post-program (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020; Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Tamminen et al., Citation2020). Internal consistency reliability scores for the PIAS ranged from .56 for the support scale and .68 for the pressure scale (Azimi & Tamminen, Citation2020) to .79 for the support and .76 for the pressure scale (Dorsch et al., Citation2017). However, no information was provided on the validity of this measurement tool.

Table 5. Evaluation measures.

There were a number of measures utilized to examine changes in parents’ behavior following the delivery of parent-education programs. Azimi and Tamminen (Citation2020) used the Parent–Adolescent Communication Scale (PACS; Barnes & Olson, Citation1985) and Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ; Buri, Citation1991) to assess quality of communication and parenting styles displayed by parents. Dorsch et al. (Citation2017) used The Sport Friendship Quality Questionnaire (Weiss & Smith, Citation1999) and Child’s Report of Parental Behaviour Inventory (Schwarz et al., Citation1985) to assess parent–child conflict and parent–child warmth pre- and post-program. Ford et al. (Citation2012) developed the Parent Experiences in Youth Sport Survey (PEYS; Ford et al., Citation2012) to evaluate parents’ self-perceived sportspersonship behaviors.

There were also a variety of measures used to examine changes in athlete outcomes, following their parents being exposed to parent-education programs. Dorsch et al. (Citation2017) utilized The Sport Commitment Model (Carpenter et al., Citation1993), Sport Competence Scale (Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2005), and Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., Citation1983) to examine changes in athletes sport enjoyment, perceived competence, and sport-related stress. Smoll et al. (Citation2007) used the Sport Anxiety Scale (SAS-2; Smith et al., Citation2006) to assess athletes sport performance anxiety, while Harwood and Swain (Citation2002) utilized the Profile of Goal Involvement Questionnaire (PGIQ; Harwood & Swain, Citation2002) and Components of Tennis Performance Questionnaire (CTPQ; Harwood & Swain, Citation2002), to assess athletes’ goal involvement, and quality of self-regulation.

Discussion

Through the present systematic review, the aim was to provide a narrative synthesis examining aspects of design, evaluation, and effectiveness of parent-education programs which target psychosocial parental support in the youth sport context. From the narrative synthesis, it was noted that education programs were delivered across a range of sport settings, with tennis and soccer appearing most popular. Further, of the 12 studies included in the review, seven were designed, implemented, and evaluated in the United States (3) and United Kingdom (4). Such an observation is mirrored by the general sport parenting literature, whereby American and British (e.g. Gould et al., Citation2006; Knight et al., Citation2011, Citation2016) samples dominate the literature, in sports such as tennis and soccer (e.g. Clarke et al., Citation2016; Lauer et al., Citation2010). Previous reviews of the parenting in sport literature have highlighted the dearth in research examining parental involvement in different sports and cultures (Dorsch et al., Citation2019, Citation2021; Harwood & Knight, Citation2016), and recommend that it is critical for future research to explore unexamined populations (Dorsch et al., Citation2021; Knight, Citation2019). The results from the present review highlight that sports such as tennis and soccer in American and British samples, also dominate the parent-education literature. A move beyond these samples in future parent-education programs may help enhance parental involvement and athlete outcomes in under investigated populations, and further our understanding of the complex phenomenon that is the parent-athlete relationship.

Of the 12 included studies, seven papers implemented a short, one-off education workshop, while the remaining five studies implemented multiple education workshops. Due to the diversity of evaluation methods (i.e. qualitative and quantitative methods), it was difficult to draw conclusions about the efficacy of programs which implemented multiple workshops, in contrast to programs which delivered one short educational session. Programs which did implement multiple workshops appeared to suffer from higher levels of attrition (e.g. Thrower et al., Citation2017; Thrower et al., Citation2019), however, given the competing demands and stressors that sport parents experience (e.g. Clarke & Harwood, Citation2014; Harwood et al., Citation2010; Harwood & Knight, Citation2009a; Harwood & Knight, Citation2009b; Thrower et al., Citation2017), this is unsurprising. Parent-education programs which delivered one educational session experienced greater parent participation (e.g. Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Ford et al., Citation2012; Smoll et al., Citation2007; Tamminen et al., Citation2020) and appeared to be a more time and cost-efficient means of delivering parent-education. However, such programs are often short and instructive in nature, which fail to promote parent interaction with both researchers and fellow parents. One must question the long-lasting impact, effectiveness, and behavior change associated with such programs.

Future researchers and practitioners should continue to develop and implement longitudinal educational programs, with multiple sessions and forums to promote extended parental involvement and interaction, in addition to long-term follow-up support. In doing this, researchers and practitioners should also consider the various demands sport parents experience (e.g. time constraints, childcare) in the planning stage of the intervention and implement strategies to promote greater participation. One strategy which may be appropriate is flexible engagement methods (e.g. an option of in person face-to-face or virtual recorded sessions) and family friendly delivery environments. Further, increased support from National Governing Bodies (Richards & Winter, Citation2013), and incentives for participation (Thrower et al., Citation2019) may also reduce attrition rates. However, even implementing such strategies it is possible that such longitudinal programs will still experience lesser participation, but as researchers and practitioners we must take into consideration the long-lasting impact and behavior change associated with such programs, in contrast to short, one-off education sessions.

Additionally, future researchers could also consider adopting randomized controlled trials and evaluating athlete outcomes. Many of the parent-education programs included in this review examined changes in parents’ knowledge and behaviors (e.g. Thrower et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). Given that the aim of such programs is to improve parent’s knowledge and attitudes, examining parents experiences of such interventions is appropriate. Future research should consider the impact of parent-education programs on athlete outcomes, post-intervention and at follow-up. Examining the impact of such programs on athlete’s experiences and outcomes would advance study designs in this area, and also allow researchers and practitioners to unpack the impact of such programs on athletes too. Further, many of the existing parent-education programs reported changes in parent’s knowledge as a result of participation. However, previous research (Dorsch et al., Citation2009, Citation2015) has documented that parent’s develop both technical and context-specific sport knowledge as a result of their children’s sport participation. Implementing randomized control trials when developing future parent-education programs will allow researchers to identify changes and improvements that are occurring as a result of the implementation of any interventions, in contrast to changes occurring as a results of parent’s time spent in the youth sport environment.

All of the quantitative studies included in the review produced some significant effects, with qualitative results indicating improvements in parents’ knowledge and skills. However, again due to the diversity in program design and evaluation methods, it was difficult to draw concrete conclusions on the overall efficacy of these programs. Further, when examining the results of the included programs, there were some noteworthy limitations. First, Ford et al. (Citation2012) assessed parents’ self-perceived sportspersonship behaviors immediately after completion of the education module. An observation of parents’ sportspersonship behaviors in the youth sport context or indeed an examination of athletes’ perceptions of their parents’ behaviors pre- and post-program would have been more beneficial. Additionally, there were a number of programs that implemented multiple components (Harwood & Swain, Citation2002; Lisinskiene & Lochbaum, Citation2019; Smoll et al., Citation2007). For example, Smoll et al. (Citation2007) delivered a systemic program, designed to help coaches and parents reduce athlete anxiety, by adopting a task mastery-involving motivational climate. Similarly, Harwood and Swain (Citation2002) implemented an intervention which incorporated educational, strategy, and skills-based exercises for tennis players, parents, and coaches to enhance the motivational climate. Despite these interventions significantly reducing athletes’ anxiety (Smoll et al., Citation2007) and improving athletes task orientation (Harwood & Swain, Citation2002), due to the systemic nature of the programs it is hard to conclude which component led to these positive outcomes.

A critical component of rigorous intervention design is the inclusion of a theoretical underpinning in its design and evaluation. The explicit use of theory has many advantages. First, theory can help inform the development of interventions, by identifying theoretical constructs which influence behavior. Further, theory-based interventions can also help researchers and practitioners identify why interventions are effective or ineffective (Michie & Prestwich, Citation2010). As a result, theory-based interventions can help further develop and refine the underlying theory (Prestwich et al., Citation2015). Despite the well documented benefits of the inclusion of an underlying theoretical framework, there were variable results with regards theoretical underpinnings in the included studies.

Azimi and Tamminen (Citation2020), Smoll et al. (Citation2007), Harwood and Swain (Citation2002), Thrower et al. (Citation2017), and Thrower et al. (Citation2019) all explicitly stated how theory informed the development of their programs. However, there were three studies included in the review which lacked clarity on how theory was utilized. For example, Dorsch et al. (Citation2017) cited Ecological Theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation2005) when discussing their hypothesis. However, it remained unclear how this theory informed the development and/or implementation of the program. Similarly, Lisinskiene and Lochbaum (Citation2019) cited Attachment Theory (Bowlby, Citation1988), but again failed to explain how it influenced the development of the intervention. Michie and Prestwich (Citation2010) have previously highlighted that simply citing theory-based literature in relation to the intervention is not sufficient, and that it is imperative of researchers and practitioners to explain how theory has guided the intervention.

Additionally, there were four studies which failed to make reference to any theory (Ford et al., Citation2012; Richards & Winter, Citation2013; Sampol et al., Citation2019; Tamminen et al., Citation2020). Such an observation can be linked to Prestwich et al. (Citation2014) who have previously noted a lack of theory in the design and evaluation of intervention research. Further, when theory is embedded within an intervention, it is not applied extensively (e.g. Dorsch et al., Citation2017; Lisinskiene & Lochbaum, Citation2019). Researchers in the field of sport and exercise psychology have expressed their concerns at the lack of rigorous intervention research designs within the field (Schinke et al., Citation2020). The lack of explicit use of theory within the included parent-education programs lends weight to this claim.

In terms of future directions and advancing research design, the application of behavior change theory (e.g. Social Learning Theory; Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change) (Bandura, Citation1977; Prochaska & Velicer, Citation1997) appears to provide a fruitful avenue to help achieve positive changes in behavior among sport parents. Behavior change theory allows researchers and practitioners to identify the specifics of ‘why, when, and how behaviour does or does not occur, and the important sources of influence to be targeted in order to alter the behaviour’ (Michie et al., Citation2014, p. 33). In a recent review of coach development programs, Allan et al. (Citation2018) highlighted that a theory which only identifies optimal behaviors for producing certain outcomes cannot be classified as a behavior change theory. Instead, behavior change theories go beyond this by providing an explanation on how and why human behaviors change or the conditions that lead to behavior change. Tamminen et al. (Citation2020) has recently suggested that parent-education programs would benefit from the inclusion of behavior change theories. Further, looking beyond parent-education, coach development programs have previously implemented behavior change theories successfully, with positive outcomes (e.g. Cheon et al., Citation2015; Zakrajsek & Zizzi, Citation2008). We acknowledge that the aim of many of the programs included in this review was to examine the effects of parent-education on parents’ attitudes and cognitions, and therefore such programs did not lend themselves to the adoption of behavior change theories. However, given the documented benefits of using behavior change theories, as suggested by Tamminen et al. (Citation2020) future researchers may benefit from advancing research designs and adopting appropriate behavior change frameworks (e.g. Transtheoretical Model; Theory of Planned Behaviour) in the development and implementation of parent-education programs in youth sport, to promote positive behavior change among sport parents and to illustrate how this change occurs.

When designing behavior change interventions, it is imperative that careful consideration is given to the theoretical basis of the intervention and that such interventions target and measure theoretically relevant constructs, both at baseline and follow-up (Michie & Johnston, Citation2012). Furthermore, of particular pertinence is the implementation of Behaviour Change Techniques (BCT). A BCT is an observable, replicable and irreducible component designed to alter behavior. Michie et al. (Citation2015) developed an extensive hierarchically structured taxonomy of behavior change techniques, which included techniques such as goal setting, problem-solving, monitoring of behavior, and social support. Future researchers may consider this taxonomy when designing and implementing behavior change interventions. Examining papers included in this review, Azimi and Tamminen (Citation2020) utilized reflective practice to help parents reflect on their communication with their children in sport contexts. Further, Thrower et al. (Citation2019) utilized an online discussion forum for parents to interact with other parents. Although the authors did not present such strategies as BCT’s, one could argue that they are forms of self-monitoring of behavior and social support, both of which are behavior change techniques listed by Michie et al. (Citation2015). Moving forward, it is important that there is alignment between both the constructs of behavior change and the chosen behavior change techniques (Michie & Johnston, Citation2012). Complementing earlier discussions, it is unlikely that short, one-off parent-education sessions will achieve such behavior change, supporting the need for future programs to design and implement longitudinal, multiple session and interactive programs, which consider the multitude of demands placed on parents of youth athletes.

When examining the measures used to evaluate the programs included in the current review, there appears to be a clear absence of sport-specific measures available to examine changes in parents’ behavior. For example, the Parent–Adolescent Communication Scale (PACS; Barnes & Olson, Citation1985) and the Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ; Buri, Citation1991) were used to assess quality of communication and parenting styles displayed by parents, despite not being developed or validated for use in a sport-specific context. Gill (Citation1997) reported that one of the most significant advances in the field of sport and exercise psychology was the move away from general psychometric measures, toward sport-specific measures pertinent to sport and exercise behaviors. Despite this progress being acknowledged decades ago, it is somewhat surprising to still see general measures of parent behaviors being used to evaluate parent-education programs in youth sport. Further, with the exception of the Parental Involvement in Activities Scale (Anderson et al., Citation2003), sport-specific measures utilized focused more on examining parents’ self-efficacy or experiences within sport (e.g. Tennis Parent Efficacy Scale; Tool to Measure Parenting Self-Efficacy; Sports Emotion Questionnaire) rather than aspects of parental involvement, such as support or communication. Although we encourage researchers and practitioners to consider validated and sport-specific measures of parental involvement when evaluating future parent-education programs,the results from this review suggest that such measures are sparse, supporting Knight’s (Citation2019) claim that there is currently an absence of psychometrically sound, sport-specific measures available to examine changes in parents’ behaviors in youth sport.

The Parental Involvement in Activities Scale (Anderson et al., Citation2003) was the most utilized measure among the included studies. This is not surprising given that it appears to be the only sport-specific scale which measures parental support. The PIAS was developed to assess children’s perceptions of their parents’ involvement in their extracurricular activity participation and is a 16-item measure of parental support and pressure. Despite its extensive use, there are some notable issues with this measure. Firstly, when examining the reliability of the PIAS there was a great deal of variability in the reported internal consistency reliability scores. Azimi and Tamminen (Citation2020) reported poor reliability and encouraged readers to carefully interpret the results for the PIAS and went on to urge future researchers and practitioners to consider alternative measures of parental involvement in sport. However, Dorsch et al. (Citation2017) reported acceptable reliability for the measure. Looking beyond the included studies to other research which has made use of the PIAS, Anderson et al. (Citation2003) reported acceptable reliability for the development of the tool (Cronbach’s alpha .70 for the support scale and .71 for the pressure scale). Despite reporting acceptable reliability scores, Anderson et al. (Citation2003) noted that further research and psychometric testing on the PIAS is required, including an examination of its convergent and divergent validity. To our knowledge, no further rigorous psychometric testing has been completed for this measure. Further, it is well documented that theory plays an imperative role in the development of scales, particularly in the social sciences (Tenenbaum et al., Citation2012). However, the PIAS does not identify any theoretical framework or evidence-based literature which guided its development. Such an observation again supports Knight (Citation2019) regarding the lack of any theory-grounded measures within the area.

Future research directions

Collins and Cruickshank (Citation2017) discussed how measures should be designed for a specific purpose, population, and event. Similarly, Harwood et al. (Citation2019) discussed the importance of giving consideration to specific youth sport contexts in which parents are present (i.e. competition and training) and specific youth sport types (i.e. individual or team sports), when developing measures of parental involvement. The results from the current review confirm that there are challenges when evaluating parent-education programs in youth sport (Knight, Citation2019). Although scale development research requires complex and systematic procedures that require theoretical and methodological rigor (Morgado et al., Citation2017), given the lack of sport-specific measures of parental involvement in youth sport which can be used to specifically examine changes in parents’ behaviors, future research would certainly benefit from the development and validation of theory-informed measures of parental involvement and support, which give thought to the development stage of athletes (Knight, Citation2019; Thrower et al., Citation2019). The development and validation of such measures, will allow future researchers to specifically examine changes in parents’ behaviors (Knight, Citation2019) and also measure the domain of learning targeted in future parent-education programs (Thrower et al., Citation2019).

Although the application of behavior change theories is more prominent in health psychology interventions, the application of such theories has shown positive effects in coaching development programs and appear to provide an appropriate avenue to further advance the parent-education literature. Lastly, in line with Harwood and Knight (Citation2015), Knight (Citation2019) and Dorsch et al. (Citation2021) researchers and practitioners should diversify population samples, when delivering and evaluating future parent-education programs, to help develop a better understanding of the topic.

Limitations

Due to the variability in study designs and evaluation methods, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis to draw conclusions on the overall effect of the included parent-education programs on psychosocial parental support. Further, while there were apparent issues with measures utilized to evaluate the programs, it is important to consider that there is a lack of measures available to examine changes in behavior within this area. As a result, researchers and practitioners are utilizing the most appropriate available scales.

Conclusion

The present systematic review sought to examine the efficacy of parent-education programs which target psychosocial parental support in youth sport. Theoretical frameworks and psychometric measures utilized in the design and evaluation of the included programs were also examined. Quantitative studies yielded significant results for the efficacy of the parent-education programs, with qualitative results also indicating improvements in parents’ skills and knowledge. Future researchers should look toward adopting explicit use of theory when designing and evaluating parent-education programs. Further, the use of behavior change theories provides an appropriate avenue to advance this research area. Lastly, future research developing and evaluating parent-education programs within the context of youth sport should consider validated and sport-specific measures of parent involvement. However, results from the present review suggest that such measures are sparse.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the systematic review.

- Allan, V., Vierimaa, M., Gainforth, H. L., & Côté, J. (2018). The use of behaviour change theories and techniques in researched-informed coach development programmes: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1286514

- Anderson, J. C., Funk, J. B., Elliott, R., & Smith, P. H. (2003). Parental support and pressure and children’s extracurricular activities: Relationships with amount of involvement and affective experience of participation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24(2), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00046-7

- *Azimi, S., & Tamminen, K. A. (2020). Parental communication and reflective practice among youth sport parents. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2019.1705433

- Baker, J., Horton, S., Robertson-Wilson, J., & Wall, M. (2003). Nurturing sport expertise: Factors influencing the development of elite athlete. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 2(1), 1–9.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

- Barnes, H. L., & Olson, D. H. (1985). Parent-adolescent communication and the circumplex model. Child Development, 56(2), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129732

- Bois, J. E., Lalanne, J., & Delforge, C. (2009). The influence of parenting practices and parental presence on children’s and adolescents’ pre-competitive anxiety. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(10), 995–1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410903062001

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage.

- Buri, J. R. (1991). Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57(1), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13

- Carpenter, P. J., Scanlan, T. K., Simons, J. P., & Lobel, M. (1993). A test of the sport commitment model using structural equation modelling. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 15(2), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.15.2.119

- Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., Lee, J., & Lee, Y. (2015). Giving and receiving autonomy support in a high- stakes sport context: A field-based experiment during the 2012 London Paralympic games. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 19, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.02.007

- Clarke, N. J., & Harwood, C. G. (2014). Parenting experiences in elite youth football: A phenomenological study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(5), 528–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.05.004

- Clarke, N. J., Harwood, C. G., & Cushion, C. J. (2016). A phenomenological interpretation of the parent-child relationship in elite youth football. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 5(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000052

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Collins, D., & Cruickshank, A. (2017). Psychometrics in sport: The good, the bad and the ugly. In B. Cripps (Ed.), Psychometric Testing: Critical Perspectives (pp. 145–156).

- Côté, J. (1999). The influence of the family in the development of talent in sport. The Sport Psychologist, 13(4), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.13.4.395

- Dorsch, T. E. (2017). Optimising family involvement in youth sport. In C. J. Knight, C. G. Harwood, & D. Gould (Eds.), Sport psychology for young athletes (pp. 106–115). Routledge.

- Dorsch, T. E., Smith, A. L., Blazo, J. B., Coakley, J., Côté, J., Wagstaff, C. R., Warner, S., & King, M. Q. (2020). Toward an integrated understanding of the youth sport system. Research Quarterly in Exercise and Sport, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2020.1810847

- Dorsch, T. E., Smith, A. L., Wilson, S. R., & McDonough, M. H. (2015). Parent goals and verbal sideline behavior in organized youth sport. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 4(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000025

- Dorsch, T. E., Vierimaa, M., & Plucinik, J. (2019). A citation network analysis of research on parent-child interactions in youth sport. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 8(2), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000140

- Dorsch, T. E., Wright, E., Eckardt, V. C., Elliott, S., Thrower, S. N., & Knight, C. J. (2021). A history of parent involvement in organized youth sport: A scoping review. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000266

- Dorsch, Travis E, Smith, Alan L., & McDonough, Meghan H. (2009). Parents' Perceptions of Child-to-Parent Socialization in Organized Youth Sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 31(4), 444–468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jsep.31.4.444

- *Dorsch, T. E., King, M. Q., Dunn, C. R., Osai, K. V., & Tulane, S. (2017). The impact of evidence-based parent education in organized youth sport: A pilot study. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 29(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2016.1194909

- *Ford, D. W., Jubenville, C. B., & Phillips, M. B. (2012). The effect of the STAR Sportsmanship education module on parents’ self-perceived sportsmanship behaviors in youth sport. Journal of Sport Administration & Supervision, 4(1), 114–126.

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Parental influences on youth involvement in sports. In M. R. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 145–164). Fitness Information Technology.

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Family socialization, gender, and sport motivation and involvement. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 27(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.27.1.3

- Gagné, M., Ryan, R. M., & Bargmann, K. (2003). Autonomy support and need satisfaction in the motivation and well-being of gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 15(4), 372–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/714044203

- Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit.

- Gill, D. L. (1997). Measurement, statistics, and research design issues in sport and exercise psychology. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 1(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327841mpee0101_3

- Gould, D., Lauer, L., Rolo, C., Jannes, C., & Pennisi, N. (2006). Understanding the role parents play in tennis success: A national survey of junior tennis coaches. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(7), 632–636. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.024927

- Greendorfer, S. L. (1992). Sport socialization. In T. S. Horn (Ed.), Advances in sport psychology (pp. 201–218). Human Kinetics.

- Gunnell, K., Poitras, V. J., & Tod, D. (2020). Questions and answers about conducting systematic reviews in sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2019.1695141

- Harwood, C., Drew, A., & Knight, C. J. (2010). Parental stressors in professional youth football academies: A qualitative investigation of specialising stage parents. Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, 2(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/19398440903510152

- Harwood, C., & Knight, C. (2009a). Stress in youth sport: A developmental investigation of tennis parents. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(4), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.01.005

- Harwood, C., & Knight, C. (2009b). Understanding parental stressors: An investigation of British tennis-parents. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(4), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802603871

- Harwood, C. G., Caglar, E., Thrower, S. N., & Smith, J. M. (2019). Development and validation of the parent-initiated motivational climate in individual sport competition questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00128

- Harwood, C. G., & Knight, C. J. (2015). Parenting in youth sport: A position paper on parenting expertise. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.03.001

- Harwood, C. G., & Knight, C. J. (2016). Parenting in sport. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 5(2), 84–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000063

- *Harwood, C., & Swain, A. (2002). The development and activation of achievement goals within tennis: II. A player, parent, and coach intervention. The Sport Psychologist, 16(2), 111–137. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.16.2.111

- Holt, N. L., Tamminen, K. A., Black, D. E., Mandigo, J. L., & Fox, K. R. (2009). Youth sport parenting styles and practices. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 31(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.31.1.37

- Holt, N. L., Tamminen, K. A., Black, D. E., Sehn, Z. L., & Wall, M. P. (2008). Parental involvement in competitive youth sport settings. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9(5), 663–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.08.001

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffith, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada.

- Jowett, S., & Timson-Katchis, M. (2005). Social networks in sport: Parental influence on the coach-athlete relationship. The Sport Psychologist, 19(3), 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.19.3.267

- Juntumaa, B., Keskivaara, P., & Punamäki, R. L. (2005). Parenting, achievement strategies and satisfaction in ice hockey. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 46(5), 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2005.00472.x

- Kidman, L., McKenzie, A., & McKenzie, B. (1999). The nature of target of parents’ comments during youth sport competitions. Journal of Sport Behavior, 22(1), 54–75.

- Knight, C. J. (2019). Revealing findings in youth sport parenting research. Kinesiology Review, 8(3), 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2019-0023

- Knight, C. J., & Holt, N. L. (2013a). Factors that influence parents’ experiences at junior tennis tournaments and suggestions for improvement. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 2(3), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031203

- Knight, C. J., & Holt, N. L. (2013b). Strategies used and assistance required to facilitate children’s involvement in tennis: Parents’ perspectives. The Sport Psychologist, 27(3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.27.3.281

- Knight, C. J., Little, G. C., Harwood, C. G., & Goodger, K. (2016). Parental involvement in elite junior slalom canoeing. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(2), 234–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2015.1111273

- Knight, C. J., Neely, K. C., & Holt, N. L. (2011). Parental behaviors in team sports: How do female athletes want parents to behave? Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2010.525589

- Knight, C. J., & Newport, R. A. (2017). Understanding and working with parents of young athletes. In C. J. Knight, C. G. Harwood, & D. Gould (Eds.), Sport psychology for young athletes (pp. 303–314). Routledge.

- Lauer, L., Gould, D., Roman, N., & Pierce, M. (2010). Parental behaviours that affect junior tennis player development. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(6), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.06.008

- Leff, S. S., & Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Young athletes’ perceptions of parental support and pressure. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537149

- *Lisinskiene, A., & Lochbaum, M. (2019). A qualitative study examining parental involvement in youth sports over a one-year intervention program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193563

- Loy, J. (1968). The nature of sport: A definitional effort. Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich ), 10(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.1968.10519640

- *McMahon, J., Knight, C., & McGannon, K. (2018). Educating parents of children in sport about abuse using narrative pedagogy. Sociology of Sport Journal, 35(4), 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2017-0186.

- Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions (1st ed., pp. 1003–1010). London: Silverback Publishing.

- Michie, S., & Johnston, M. (2012). Theories and techniques of behaviour change: Developing a cumulative science of behaviour change. Health Psychology Review, 6(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2012.654964

- Michie, S., & Prestwich, A. (2010). Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychology, 29(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016939

- Michie, S., Wood, C. E., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., & Hardeman, W. (2015). Behaviour change techniques: The development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions. Health Technology Assessment, 19(99), 1–188. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19990

- Morgado, F. F., Meireles, J. F., Neves, C. M., Amaral, A., & Ferreira, M. E. (2017). Scale development: Ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 30(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0057-1

- Nelson, L., Groom, R., & Potrac, P. (Eds.). (2016). Learning in sports coaching: Theory and application. Routledge.

- Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91(3), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.328

- O’Rourke, D. J., Smith, R. E., Smoll, F. L., & Cumming, S. P. (2011). Trait anxiety in young athletes as a function of parental pressure and motivational climate: Is parental pressure always harmful? Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 23(4), 398–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2011.552089

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetlaff, J. M., & Moher, D. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003

- Power, T. G., & Woolger, C. (1994). Parenting practices and age-group swimming: A correlational study. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 65(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1994.10762208

- Prestwich, A., Sniehotta, F. F., Whittington, C., Dombrowski, S. U., Rogers, L., & Michie, S. (2014). Does theory influence the effectiveness of health behavior interventions? Meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 33(5), 465–474. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032853

- Prestwich, A., Webb, T. L., & Conner, M. (2015). Using theory to develop and test interventions to promote changes in health behaviour: Evidence, issues, and recommendations. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.02.011

- Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

- *Richards, K., & Winter, S. (2013). Key reflections from “on the ground”: Working with parents to create a task climate. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 4(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2012.733909

- Ryan, R. (2013). Cochrane consumers and communication review group: Data synthesis and analysis.

- *Sampol, P. P., Salas, D. P., Rotger, P. A. B., & Verdaguer, F. J. P. (2019). A socioeducational intervention about parental attitudes in grassroots football and its effects. Sustainability, 11(13), 3500. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133500

- Sánchez-Miguel, P. A., Leo, F. M., Sánchez-Oliva, D., Amado, D., & García-Calvo, T. (2013). The importance of parents’ behavior in their children’s enjoyment and amotivation in sports. Journal of Human Kinetics, 36(1), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2013-0017

- Schinke, R. J., Mellalieu, S., Ntoumanis, N., Kavussanu, M., Standage, M., Strauss, B., & Papaioannou, A. (2020). Getting published: Suggestions and strategies from editors of sport and exercise psychology journals. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 33(6), 555–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1741725

- Schwarz, J. C., Barton-Henry, M. L., & Pruzinsky, T. (1985). Assessing child-rearing behaviors: A comparison of ratings made by mother, father, child, and sibling on the CRPBI. Child Development, 56(2), 462–479. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129734

- Smith, R. E., Smoll, F. L., Cumming, S. P., & Grossbard, J. R. (2006). Measurement of multidimensional sport performance anxiety in children and adults: The sport anxiety scale-2. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 28(4), 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.28.4.479

- *Smoll, F. L., Smith, R. E., & Cumming, S. P. (2007). Effects of coach and parent training on performance anxiety in young athletes: A systemic approach. Journal of Youth Development, 2(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.5195/JYD.2007.358

- Snyder, E. E., & Purdy, D. A. (1982). Socialization into sport: Parent and child reverse and reciprocal effects. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 53(3), 263–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1982.10609352

- Stein, G. L., Raedeke, T. D., & Glenn, S. D. (1999). Children’s perceptions of parent sport involvement: It’s not how much, but to what degree that’s important. Journal of Sport Behavior, 22(4), 591–601.

- *Tamminen, K. A., McEwen, C. E., Kerr, G., & Donnelly, P. (2020). Examining the impact of the respect in sport parent program on the psychosocial experiences of minor hockey athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(17), 2035–2045. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1767839