ABSTRACT

If democracy is a platform for many voices, and the voices of the many, journalists serve democracy by bringing these voices to the forefront of governance by asking difficult questions to those in power. It can be argued that journalists engage in the broader form of surveillance of power from below, or sousveillance [Mann, Steve, and Joseph Ferenbok. 2013. “New media and the power politics of sousveillance in a surveillance-dominated world.” Surveillance and Society 11 (1-2): 18–34.], which aims towards a form of relative equilibrium. In democracies, the institutional system of checks and balances forms the basis on which journalism pursues its watchdog function. This paper explores the experiences of journalists with surveillance and their impact on journalists’ sense of freedom to fulfil their watchdog role. The paper contributes to increasing research interest in “journalism after Snowden” by addressing the intangible conditions under which journalists may or should work, and ultimately also how widely accepted standards of democratic liberties are challenged.

Defining Surveillance

Our working definition of surveillance extends beyond standard versions such as “the act of carefully watching someone or something”Footnote1 to encompass a broad array of types of watching. As Marx (Citation2002, 9) points out in his critique of standard definitions of surveillance which tend to underscore the visual, physical aspects,

new technologies for collecting personal information (…) transcend the physical, liberty enhancing limitations of the old means. These probe more deeply, widely and softly than traditional methods, transcending natural (distance, darkness, skin, time and microscopic size) and constructed (walls, sealed envelopes) barriers that historically protected personal information.

Marx also points to self-surveillance, which transcends the classical differentiation between surveillors and surveilled. This may be of significance in the context of self-censorship by citizens and journalists. Although we draw upon Marx's definition, in this paper we treat surveillance as a set of tactics and practices with a regulatory effect on the conditions under which information is produced for public consumption. Predominantly, we focus on surveillance experiences of journalists and their impact on their sense of safety and liberty to fulfil their professional obligations.

The effects of surveillance on journalism have only recently attracted attention, in the light of the revelations about mass surveillance and documented effects of stifling minorityFootnote2 views and evidence of self-censorship online among general populations (Mann and Ferenbok Citation2013; Stoycheff Citation2016). Pen America’s (Citation2014) report, “Global Chilling: The Impact of Mass Surveillance on International Writers”, found that almost as many writers (75%) living in democracies were concerned about surveillance as in non-democracies (80%) and that the degree of self-censorship by writers in democracies, as a consequence of surveillance, is approaching that in semi-democracies and authoritarian countries.

A 2015 Pew Research Center study of US investigative journalists found that approximately two-thirds of the investigative journalists surveyed (64%) believed that “the U.S. government has probably collected data about their phone calls, emails or online communications”, and 80% felt that their work as a journalist augmented the probability that their data was being surveilled. National security, foreign affairs and federal government reporters were even more likely (71% of them) to think the government had already collected data about their electronic communications.

A “Panoptic climate” appears to emerge, whose core aim is akin to that envisioned by eighteenth century British philosopher Bentham (Citation1791): to instil self-disciplinary behaviours among inmates under the impression of constant surveillance. Bentham, in conceiving of the Panopticon design, recognised that the most efficient manner to maintain surveillance effects would be not through uninterrupted surveillance of every inmate – impossible from a resources perspective – but through instilling in each inmate the sense that “at every instant, seeing reason to believe as much, and not being able to satisfy himself to the contrary, he should conceive himself to be” (Bentham Citation1791, 3) under surveillance.

And further: “The greater the chance there is, of a given person's being at a given time actually under inspection, the stronger will be the persuasion, the more intense … the feeling he has of being so.” (Bentham Citation1791, 25) Today's omniscient ubiquitous surveillance societies have a similarly conforming effect, prompting self-censorship (Stoycheff Citation2016). The stronger the feeling of omni-present surveillance is, the greater the self-censorship. Indeed, in her 2016 study, Stoycheff shows that the perception of post-Snowden surveillance practices as “omni-present” is resulting in measurable self-censorship online. The inherent possibility of continuous surveillance is designed to “ … induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power.” (Foucault Citation1995, 213–214) The institutionalised format of such a Panopticon can be found first in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 with the Total Information Awareness programme in the USA. The programme, as described in the New York Times on 15 December 2002, with “Knowledge is power” in Latin in its logo envisaged the creation of a super-database of information – reaped in part from private companies – about US citizens that could be analysed by intelligence agencies to create “risk profiles” in a form of predictive policing. It was allegedly discontinued in 2013.

Western democracies now constitute a “surveillance society” in which a grey zone fusing state and corporate surveillance, including that inherent to the use of social media, has infused everyday life. Giroux speaks of a “surveillance regime” (Citation2015, 108), and further notes that “the unwarranted collection of personal information from people who have not broken the law in the name of national security and for commercial purposes is a procedure often adopted by totalitarian states (Giroux Citation2015, 113)”. Lyon warns that we may see a uniformed world out of fear to stand out or stand up, as citizens are “being reclassified as potential threats to state security.”

The chilling climate created by both perceived and actual ubiquitous systematic surveillance for both journalists and sources is connected to what both journalists and sources term “paranoia”. The prompting and fuelling of “paranoia” is a tactic with a longstanding precedent used by intelligence agencies in both Western democracies and authoritarian countries to pressure activists and journalists. Decades ago, White and Zimbardo (Citation1980, 50) wrote that in the US an increase in perceived and actual surveillance had created a “paranoid theme” in American life. This was borne out by revelations in the early 1970s that the FBI had for years been running a covert domestic counter-intelligence operation (Greenwald Citation2015) dubbed COINTELPRO targeting a broad array of activists it deemed a threat to national security. One of the memos that emerged in a subsequent investigation by the US Senate noted that “paranoia” could be promoted among activists, leading them to believe there was “an FBI agent behind every mailbox” (Greenwald Citation2015, 184).

Eley et al. (Citation2016, 305) speaks of the “double-edge” of surveillance and its fear-driven impact on democracy, including not only infringement on civil liberties, the closing down of debate, and control over dissent but also the triggering of a “retreat into anxiety, the depressing and oppressive primacy of darkly internalized self-constraints”.

In Citation1981 already, Thomas noted that the defenders of surveillance argued that abusive forms of political surveillance did not represent a potentially dark trend inherent to the very nature of surveillance but simply constituted occasional lapses by over-enthusiastic, sometimes irresponsible surveillors, who lacked the right supervision. Such a liberal democratic view, he argues, sees the answer to purportedly infrequent abuses in the tightening of state control over the surveillors, especially through the enactment of new laws and policies and the creation of various watchdog agencies. But for Thomas (47) “such arguments … ignore the structural functional and ideological sources of surveillance as a historically contingent response by control agents to perceived threats to forms of social organisation or techniques of social maintenance.”

Politicians and government agencies have an interest in exaggerating fears to justify ever more advanced surveillance mechanisms and security budgets, notes Friedman (Citation2011). And Altheide (Citation2013) points out that technology itself, involved in government security agencies’ efforts to combat threats, also helps “construct” fear. Citing Monahan (Citation2006) and Staples (Citation2000), Altheide (Citation2013, 233) speaks of a “discourse of fear” – linked to the near-constant anticipation of danger and risk – that has anchored itself centrally in everyday life and fuels the contentious suggestion that more surveillance is required, to keep everyone safe.

The “discourse of fear” (Altheide Citation2013, 233) is further reinforced by an expanding array of blogs and online echo chambers, dramatic mediatised presentation and exaggeration of rare threats in popular culture. Weller (Citation2014) points out that the notion of a continuous war against terrorism, i.e., a quasi-permanent state of threat and fear in the context of a broader virtually perpetual conflict, has centralised surveillance monitoring and identification and led to the adoption of surveillance methods that would have been perceived to be far less acceptable from a democratic civil rights standpoint than before the so-called war on terror. Yet, historically, state-operated acts of gathering information on citizens have prompted backlash, resistance and demands for free speech (Giddens Citation1990). In that respect, the dual relationship between citizen and the state has witnessed a profound shift “from anxieties about threats to collective qualities to anxieties about threats to the individual” (Agar Citation2003, 343–44).

For Bigo (Citation2014, 277), security when breaching the barriers of “normal” politics “paves the way for the destruction of democracy and its perversion into a permanent state of emergency” underpinned by fear of external threats but also of the very security agencies responsible for combating those threats. Bigo adds that we see liberal states moving away from accountability and transparency as they intensify their high-tech policing efforts. They develop what Marx (Citation1971) coined decades ago as the surveillant gaze, a constant set of eyes watching from over one's shoulder with all the fear such a gaze generates, and the stifling of democratic voices.

Nagy (Citation2017, 449) speaks of a “paradigm of fear and domination” where the former facilitates the latter, even in democracies.

Surveillance as a mode of governance resides on a historical process of justification, in which the legitimation of control is framed in terms of security and threat. Democratic governments use institutional means to justify and administer their movement towards a system of increasing authoritarianism. This ‘paradigm of fear and domination’ has become a depoliticised expert administration of nation states, where governments increasingly operate outside of their direct democratic mandate.

Russel et al. (Citation2017) provide a narrower focus on the relationship between the state and its citizens by focusing on the oft-fraught relationship between the state, especially the deep state, and national security journalists, particularly in the wake of the Snowden revelations, and the concomitant import for the health of democracy. They note that

while most news organisations in the West claim to be critical and autonomous of politicians, their relationship to issues of national security – and thus their relationship to the security state rather than the political state – proved to be more complicated. (p. 12)

Methodology

The primary research questions being investigated here is: to what extent does surveillance of journalists generate in them a sense of fear that inhibits their ability to fulfil their role as democratic watchdogs? To what extent are there differences or similarities in terms of the tactics employed by state security agencies in surveilling journalists to generate fear, in democracies, eroded democracies and non-democracies?

From these primary research questions can be derived further sub-questions. What exact forms does the fear take and to what extent can its intensity, or inhibiting effect, be quantified? Further, how can the surveillance tactics employed by state actors across the democratic and non-democratic spectrum be typified?

Frequent reference is made to the terms “investigative journalism” and “national security journalism”. The primary focus of this paper is national security journalism, although this falls within the broader category of investigative journalism, since the type of national security journalism that triggers state surveillance is more often than not investigative in nature, and many investigative journalists who cover topics outside the realm of national security, such as organised crime or corruption may also find themselves under state surveillance that induces inhibitive fear. Furthermore, testimony from the journalists interviewed indicated that those covering national security were the most likely to be the victims of state surveillance and that such surveillance within the field of national security reporting was most likely to trigger, and be designed to trigger, inhibitive fear.

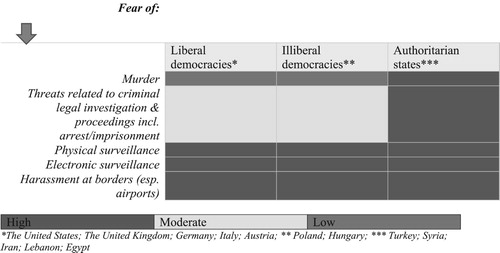

The typology was in essence born of the responses from the interviewees, as opposed to pre-conceived. On the vertical axis are the primary threats from the state that journalists face around the world. Some of these threats such as murder are present only in non-democracies. Others such as electronic surveillance are faced by journalists in democracies too. All of the threats either constitute, or are facilitated by, state surveillance. Across the horizontal axis are three categories: liberal democracies; illiberal democracies; and authoritarian states. Decisions about which countries to include in which categories are explained below. The typology is not designed to allow for scientific ranking of countries in terms of the surveillance threat they pose to journalists or in terms of their democratic health, but rather to visually depict surveillance or surveillance-assisted threats that are common to all three categories of country, or to only illiberal and authoritarian states, or to only authoritarian states – based on the testimony of the interviewees. Since the basis of the research question examined here is the generation of fear in journalists by state surveillance, either deliberately or consequentially, the typology allows us to visually – drawing from the testimony of interviewed journalists – depict the fact that certain types of state surveillance intimidation are common to countries across the world, whether they are democracies or not.

This dimension of governance relying on the individual, experiential level of degrees of freedom and potential consequences is an understudied dimension of processes of content control. The focus of this paper is on Western democracies because the dynamic of surveillance of journalists in Western democracies is an under-researched area and an area that has highly problematic implications for the health of such democracies. Thus, the question is asked: In which ways and to what effect do journalists perceive the possibility of systemic and systematic surveillance? How does it impact their practice and what might this might mean for media freedom?

Included are – in addition to relatively healthy Western democracies – testimonies from journalists from Hungary, Poland, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and Egypt, countries, which together span various degrees of distance from democratic practice, to allow for contextualisation by way of loose comparison between surveillance of journalists in both sets of countries. The countries included were in part selected because of the author's existing journalistic contacts there, since he is also active as a journalist. Nonetheless the breadth of countries chosen does, the author feels, provide enough variation for conclusions to be drawn regarding similarities, common ground and differences between relatively healthy democracies, eroded democracies and non-democracies. While the aspect of defining what is and is not a healthy democracy is a complex one and delves deeply into political science (which is not the context of this paper), the author nonetheless feels that it is possible to qualitatively categorise certain countries as relatively healthy democracies (for e.g., Germany), vs. countries that are not healthy democracies (such as Syria). Additionally, it is possible to refer to countries such as Hungary and Poland where in recent years the governments have sought to control the independent media and narrow the space for independent criticism and political opposition as countries where democracy is being eroded. These qualitative assessments are backed up by news reports and indeed independent assessments by democracy-evaluating NGOs such as Freedom House. The approach is non-reductionist and critical, as this paper seeks to identify traits in the practice of journalism within an environment of surveillance. In other words, the paper examines not just the individual behaviour and reactions of journalists to surveillance but ties in research with the broader picture, including the manner in which journalists under surveillance interact with broader state entities and what this says about democratic systems as a whole and the degree to which watchdog journalism as a Fourth Estate is being eroded in a dynamic that constitutes a threat to the health of democracy and democratic governance. Initially, I sought to examine the psychological effects of surveillance on the willingness of journalists to continue operating as before. I integrated this with extrapolations from existing media reports and academic material about the broader chilling effect of surveillance as well as about individual cases of journalists and their sources being placed under surveillance. Then I identified a number of journalists, many of whom have worked on sensitive national security stories, such as Wikileaks and the Snowden files. I sought to establish points of difference between the operating environment for such journalists before the revelations about the degree to which state entities were engaged in, and able to perform, advanced technological surveillance of journalists and their sources, and the reality afterwards in terms of psychological impact and potential chilling effects. Underscoring the sensitivity of the topic, in one instance three journalists from der Spiegel (all three of whom dealt with the Snowden story) were approached separately. But after I followed up with Der Spiegel in a quest for more in-depth interviews and research on how exactly they covered the Snowden story and what surveillance-related challenges they faced, I was told that after consultation with their legal team they had decided they could no longer accommodate any interaction with me, either verbal or written. By the end of the interviewing process, a degree of saturation of response themes was becoming evident, which allowed me to inductively identify recurring reactions. The interviews were conducted online, by phone and face to face, and took up between 30 mins and two hours. Interviewees are quoted by name here unless for security reasons I was asked not to do so.Footnote3 I interviewed a total of 47 people, comprising 37 journalists: US (7); Germany (5); Austria (5); Hungary (3); UK (3); Turkey (3); France (1); Morocco (1); Netherlands (1); Syria (1); Lebanon (1); Russia (1); Iran (1); Egypt (1); Italy (1); Zimbabwe (1); Poland (1), active in print media, broadcast and online. In addition, I interviewed eight media experts, including former journalists, involved in media research and advocacy for NGOs as well as a university (Poland: 3; Hungary: 2; UK: 1; US: 1; Serbia: 1). I also interviewed one whistleblower. I did not keep track of the number of journalists who declined, beyond the above-mentioned case of the Spiegel, where the sudden cessation of interaction following consultation with their in-house legal team was, I felt, materially relevant to the topic and paper.

Amid Intensifying Surveillance, Fear and Paranoia Take Hold

Advanced surveillance technology has upped the stakes in what has always been an adversarial relationship between investigative journalists and intelligence agencies in Western democracies, observes veteran US investigative journalist Seymour Hersh (personal communication, March 16, 2016) “The government's always hostile to reporters that tell a different story than they do … it's always been horrible. It's always been chilling.” But he notes that they “now have more tools they can use”. With testimonies from journalists who have experiences with surveillance, I aim to demonstrate the ways in which surveillance is being increasingly perceived by journalists as in the words of Marx (Citation2002) unseen, and non-human, i.e., electronic. But journalists’ testimonies also indicate that the more traditional forms of surveillance dependant on physical monitoring by individual surveillance agents have not been abandoned; they coexist, employed by a broad array of state actors across the democratic and undemocratic State spectrum, in an effort to instil fear, even paranoia. Although technology has allowed state entities involved in surveillance of journalists to ramp up their electronic eavesdropping, both forms of surveillance are applied, but possibly with different aims: if ubiquitous, technologically based, invisible surveillance is applied for the purpose of intelligence gathering, without making itself known to the subject, even if it targets professionals, then the intentionally visible tactics of physical methods of surveillance serve the purpose of “making known” and of intimidation to induce fear. The various forms of surveillance are producing feelings of fear and paranoia in journalists, both in intense bursts (linked to the immediate effect of visible traditional human surveillance) and as a corrosive “paranoid” sense of unease (especially linked to “new” pervasive electronic surveillance). Here I group the types of surveillance by type experienced by the interviewees, whereby the most pervasive and widely reported one is “electronic” but the evidence of more traditional forms is readily apparent.

The following testimonies span these typologies of surveillance:

electronic

a1. abstract suspicion of its existence

a2. concrete: evidence (malware, screens etc)

physical offline

b1. institutionalised, cloaked (border control and search)

b2. open, exhibition of power by state and agencies (followed, immediate approach)

Overt Physical Monitoring and Harassment

Unmarked vans were parked outside the offices and homes of Guardian journalists who covered the Snowden revelations in the weeks after the story broke. In what one of the journalists described as “half-Stasi”, they were forced to destroy the hard drives of computers with pneumatic drills and sledge hammers in the basement of their newspaper building under the watch of two note- and photograph-taking security officials from one of the country's spy agencies – one of whom subsequently said: “We can call off the helicopters.” (Luke Harding, personal communication, February 29, 2016)

Harding, who covered the Snowden story, adds:

I had some strange encounters in Rio … when I met GlennFootnote4 we had to move location about three or four times because suddenly a whole host of people were kind of eavesdropping on us … These unpromising young men would suddenly sit with their backs to us. Subsequently I was more or less propositioned by someone who looked like CIA central casting in the lobby of my hotel, a guy who was suggesting we should go sightseeing together.

Italian journalist Stefania Maurizi (personal communication, March 12, 2016), who covered both WikiLeaks and Snowden for the Italian weekly L’Espresso, reports being targeted with aggressive physical surveillance during the Snowden coverage, in a public park where she was meeting a high-level source in Berlin. “It was done in a way that they wanted me aware so that I could be feeling intimidated – and it did. It actually was scary for me. I panicked. Of course, it is a chilling effect” … Fear has implications for democracy far beyond the realm of journalism, Maurizi warns: “I have serious concerns not only for me and my profession and the chilling effect on sources, on me, on my bosses … but for everyone … When you are under observation, you necessarily change your behaviour.”

Long-time national security journalist Duncan Campbell (personal communication, March 15, 2016), was placed under surveillance by the British intelligence agency GCHQ “from the moment” he called the agency up and said he was doing a story on them. The surveillance included a “watcher team” who had seen him go to various sources, who were questioned at the time. He subsequently found out that he had remained under surveillance for a number of years – after he had a motorbike accident and was in hospital “the police came and stole my papers for the intelligence agency”. Campbell, too, warns that enhanced surveillance of journalists has the effect of sparking stifling “paranoia”.

In Hungary, investigative journalist Attila Mong (personal communication, March 15, 2016) says leading investigative news journalists were approached by the secret service people for a “conversation” about how “delicate” certain topics were for Hungarian national security, and that they should “be careful”.

In Lebanon, Samir KassirFootnote5 husband of BBC Arabic journalist Gisele Khoury (personal communication, February 24, 2016), was killed with a car bomb in 2005.

In 2001 we [my husband and I] knew we were under surveillance. They wanted to make it obvious. When we were in restaurants they were at the table near us, they followed our car, they tried one night to be very close to his body when we were walking in Sassine SquareFootnote6 … After the assassination, many journalists were very afraid,

For Syrian journalists such as Carole Al Farah (personal communication, March 16, 2016) living and operating inside Syria, there has always been a mix of suffocating “direct” and “non-direct” surveillance control. The indirect control is exerted through regular citizens and a network of shadowy semi-official ubiquitous intelligence agents who are conditioned by the police state to be deeply suspicious of anyone who appear to be a journalist.

In Egypt, Shahira Amin (personal communication, February 28, 2016), a former Egyptian national TV news anchor who resigned at the height of the revolution to protest against the propagandising of the news, says she has received threats from security agents – one allegedly suggested she “check” her car before driving.

One journalist who has worked in Iran, and was imprisoned there because of that work, and who asked to remain anonymous because of the sensitivity of the topic (personal communication, March 4, 2016), says:

I remember I was in a park with one of my friends, and he said, ‘Hey, look over there, there's a woman in a chador filming us … and then when I was imprisoned and interrogated they asked if I knew they had been following me and I said I was never sure and my friend said someone was filming us in the park, and they said: ‘Yes, that was us.’

Luke Harding (personal communication, February 29, 2016), who in addition to covering the Snowden story for The Guardian was their former Moscow bureau chief, recalls the paranoia-inducing surveillance he was placed under there:

The [Russian federal security service] FSB broke into our home. They put audio and … video in all the rooms, including the bedroom and they did all of this spooky demonstrative stuff to show that they’d been there. So they left clues that even a moron could detect: open windows, central heating sawed through in the middle of the Russian winter, screensavers on my laptop deleted. The same thing happened at the office. At one point they left a sex manual by the side of my bed in Russian … There were various implied threats made against our kids. It was getting very thuggish … The idea is to encourage paranoia and for your to be unable to figure out what's going on.

Harding says that research he did indicated that these techniques were something Putin [a former KGB officer] “learned in spy school” and that were extensively used by the Stasi secret police in communist East Germany – where Putin was based for a while as a KGB agent – in the 1970s and 80s against dissidents.

The idea was basically that you would intrude in this God-like way into someone's life but the hand of the state was hidden, and people would slowly go nuts. In my case the idea was to send the message: ‘Stop writing these articles.’

Intimidation of Free Movement and the Threat of Harassment and Detention at Borders

For months after he flew to Hong Kong to interview Edward Snowden for the Guardian, every time Ewan MacAskill (personal communication, March 2, 2016) left Britain, he was pulled out of the airport passport line and harassed with fictitious reports:

They would give me lots of bullshit reasons for why I was being stopped … ‘Your passport's been lost.’ I said, ‘Well, it's not lost, I haven't reported it lost’; ‘Your passport's been stolen’; I said, ‘It's not been stolen. I’ve got it. If it had been stolen, I would have reported it.’ I’d only be held for 20 min, half an hour, but supposing I was with my wife. She goes through, she doesn't know if I’m going to be half an hour, or hours. I’d be with friends, and they would go on and didn't know if I was going to appear or not … Every time it was a different reason … Like any journalist, I’d always had this nagging feeling, ‘Am I being watched? Is somebody keeping tabs on me?’ But never quite believing it. … I’m now totally paranoid.

Then-Guardian journalist James Ball (personal communication, March 2, 2016) had “constant aggravation” entering the US.

Every time I flew through I would get a full bag search and then secondary security screening … An armed customs person walks four or five steps behind you and takes you to a little waiting room … and you’re left waiting indefinitely and eventually called up to a desk where in my case they would ask me a couple of quite irrelevant questions and then let me carry on which added three hours to a flight time.

“I have colleagues,” Ball says,

who insist that someone they talked to in an elevator who followed them around was CIA etc. … the problem is the paranoia itself is quite damaging. The silencing effect comes from there; the loss of credibility comes from there.

Veteran US national security journalist James Bamford (personal communication, March 24, 2016) spent three days with Snowden in Moscow interviewing him for Wired magazine: “I was extremely worried,” he said.

Wired magazine gave me a brand-new computer before I left … and I didn't take my IPhone or anything so I was completely free of past electronic history when I arrived there. But I was very worried when I was coming back.

Italian journalist Stefania Maurizi (personal communication, March 12, 2016) was harassed while transiting an airport [in Italy], singled out for secondary screening after being paged on the airport loudspeaker system. She said this had never happened to her before and evoked a profound feeling of anxiety.

Duncan Campbell (personal communication, March 15, 2016), too, brings up the fear of surveillance, harassment and possible arrest at border controls: “I was going to the European parliament, the Council of Europe and I was talking about stuff from Snowden that hadn't been published. I went to Sweden and I did the same, and I was very, very scared when I came back to the UK.” Of the harassment of Guardian reporter MacAskill at Heathrow airport, he says: “It persisted in encouraging other newspapers not to join The Guardian … you do something like that, you send a wave of fear out. That was the intention, that was the effect.”

Beirut-based freelance reporter Sofia Amara (personal communication, January 25, 2016) was held at Damascus airport following an undercover reporting trip. She was wracked by the fear that she could be detained for a lengthy period, badly mistreated, or literally made to “disappear”

They had my name at the airport. As soon as I stood there, they were like … here she is … I thought, ‘I’m dead, they’re going to find the [raw footage], they took my phone, so I can't call the French embassy anymore, maybe they don't know I met the French charge d’affaires, so they will just make me disappear … It was the longest two or three hours of my life.

Legal Monitoring, Harassment and Threats

Officials “mentioned” the Official Secrets Act to Guardian journalists who covered Snowden. More than two years on, a number of the UK journalists who covered the Snowden files are still “under investigation”, but are told nothing else, in a Kafkaesque situation.

One of the journalists targeted was Ewan MacAskill (personal communication, March 2, 2016), who was “prepared by Guardian lawyers for going in front of a grand jury” when he flew to the Guardian's offices in New York. James Ball (personal communication, March 2, 2016) also remains under investigation by the Metropolitan Police:

“They’ve refused to say whether they’ve lifted it off any of us … which is not the world's most reassuring thing” … “The thing with surveillance is you never know one way or another whether you’re under it. There's plenty of indications that you might be but it's very hard to ever be sure. Also … they were trying to make sure that if politicians or other senior people ever decided that they did want to start an espionage prosecution … they had evidence … It's easy to look at the danger of a chilling effect.”

For similar reasons, Stefania Maurizi (personal communication, March 12, 2016) is apprehensive about the Italian official investigation into the mass surveillance revelations by Snowden – as part of which she is due to be questioned – because she fears that Italian intelligence may be collaborating with the NSA and may thus further pressure her, through the investigation, over her reporting of the Snowden files.

Markus Beckedahl, the founding editor of German data and surveillance news website Netzpolitik, (personal communication, March 12, 2016) and a colleague were investigatedFootnote7 on treason suspicions because of an article they published, based on confidential documents from Germany's federal intelligence agency.

They had the legal right to place our homes and offices under audio surveillance, to use online surveillance, and even physical surveillance of us. That's something we were until now familiar with from repressive regimes. … so we were very surprised to find out that this is perfectly possible and legal in Germany.

Decades ago already, investigative journalist Duncan Campbell (personal communication, March 15, 2016) was arrested under Britain's Official Secrets Act and Espionage Statutes, for which there was a maximum sentence of 30 years in prison. James Bamford (personal communication, March 24, 2016) was twice threatened with prosecution under the US Espionage Act when he wrote books about the NSA during the Reagan administration.

Electronic Surveillance

Journalists have routinely been subjected to electronic surveillance, even in democracies.

“You can accuse us of paranoia,” says Luke Harding (personal communication, 29 February 2016) “but … especially after Snowden was scooted from Hong Kong to Russia, the NSA was desperate to find out what we had … they were using their technical skills to hack us. Janine Gibson [then-US-editor of The Guardian] … her chats with Glenn Greenwald kept on falling through, there was someone trying to get a ‘man in the middle’ [interception hack] on her laptop … I suspect that some kind of malware was planted in my laptop when I was out. I can't prove it but the safe I was using to store my laptop, the day before it stopped locking, and so I just left it there unlocked.”

A month later, when he was writing his book about the Snowden affair, the electronic surveillance took a strange twist:

At certain points in the text, especially when I was writing about the NSA or the damage done to Silicon Valley and so on, someone would start remotely deleting the text, with my text disappearing from right to left, and it kind of sounds nuts.

James Ball (personal communication, March 2, 2016), who also reported on the Snowden stories, and had worked for WikiLeaks before that, says: “We didn't actually talk on the phone, or on email. And we ended up, because we were doing it in multiple countries, having to fly around and meet each other.” The enhanced electronic surveillance capacities and the willingness to deploy them on a massive, intrusive scale in Western democracies are having a “great impact” on watchdog journalism, warns James Bamford (personal communication, March 24, 2016).

I think it is the beginning of what might be called a Panoptic society. You have these two divergent things happening: The Internet providing more information that anyone has ever had. On the other hand, it provides the government with the greatest ability to keep track of what everybody is doing … I think there definitely is [a growing sense of fear] That fear has a real inhibiting effect on journalists who could easily find some less threatening article to write about.

Investigative journalist Gavin MacFadyen, (personal communication, March 16, 2016), who directed the London-based Centre for Investigative Journalism, declares:

The [electronic] surveillance makes it almost impossible for serious journalism work, at a high level, particularly in the fields of security or military, or police, or oppressive fields anywhere in the world to function … It's a dangerous world they are creating which has no democratic basis … an unreal Orwellian world.

Markus Beckedahl (personal communication, March 12, 2016) notes:

Of course we are more hesitant to get on the phone with certain sources … We minimise email contact, even when it's encrypted … The kind of surveillance systems we have set up after 9/11 would have been a dream for the East German Stasi [secret police].

Michael Sontheimer (personal communication, March 15, 2016) says: “If you work in this field you can be sure that your phone numbers, your email address and so on will end up on some selectors list of the NSA or GCHQ, and that makes you feel uneasy.” Der Spiegel learned from the Snowden leaks that half a year after they covered the WikiLeaks cables in 2010, as part of a consortium with the New York Times, The Guardian, and WikiLeaks, its research had been monitored and phone calls surveilled. Holger Stark (personal communication, March 15, 2016), a lead reporter on the Snowden story and on the weekly's WikiLeaks coverage several years before that, says: “It shows how easily a democracy can be undermined.”

MacFadyen echoes: “Western democracies are democracies until you do something, you step out of the cosy circle of accepted appropriate ‘information’ (personal communication, March 16, 2016). They’re getting the [surveillance] tools to do it. Are they not going to use them? Of course they are.” And decades ago already, Duncan Campbell's (personal communication, March 15, 2016) phone was tapped “within a matter of days” after he placed a single call as a journalist to the country's GCHQ intelligence agency.

Even in a small, wealthy, ostensibly healthy EU democracy like Austria, Barbara Wimmer (personal communication, February 4, 2016), who writes about surveillance and big data for Futurezone.at, says of the handful of journalists in Austria who cover national security and surveillance: “We are all paranoid.” She explains that when she once received calls from a ministry press officer about her tweets. “So I definitely know they are reading all that I communicate on Twitter … This is a kind of public surveillance … I have stopped tweeting certain things.”

A Hungarian investigative journalist (personal communication, January 22, 2016), who asked not to be identified because of the sensitivity of the topic, mentioned a case of a critical journalist who through a blog was warned about the “high” mortgage he had taken out with a recently nationalised bank. “It clearly showed that they have access to personal banking information and they are taking advantage of that.” This and other developments, he warns, mean that Hungary could “very easily turn into a police state”. Hungarian journalist Attila Mong (personal communication, February 3, 2016) warns of a “grey zone” around the secret services and police.

Sometimes there are policemen, or ex-policemen, or ex-secret service people who may still [secretly] be in the secret service in a double role … doing security stuff for private companies or private businessmen who would do [surveillance of journalists] … It certainly has an impact on journalists. They avoid certain kinds of topics … out of fear of being under surveillance or attracting a bigger focus from the secret service on them and their families.

In Poland, Katarzyna Szymielewicz (personal communication, February 27, 2016), who works for the Polish NGO Panoptykon, warns of Polish security bodies’ ability to easily find who “contacted a journalist around the time a story broke … For that, you don't need to wiretap. It can be done without any court oversight.” Polish investigative journalist Vadim Makarenko (personal communication, February 24, 2016) says that there is concern within the journalistic community that the new legislation has put surveillance “out of control”.

Turkish columnist Kadri Gursel (personal communication, February 24, 2016) says there's a real Panoptic climate of surveillance fear among journalists in Turkey.

Generally the surveillance of journalists is done through illegal ways. Our phones are tapped. But it's not easy to prove. I can't prove that my phone is tapped. I don't know whether my email communication is also tapped – or not – is surveilled – or not.

Egyptian journalist Shahira Amin (personal communication, February 28, 2016) says: “Security agents make no secret of the fact that they are monitoring Facebook and Twitter accounts. They post comments publicly, reprimanding you for something you’ve posted and at times threatening you in your inbox.” Incoming email is often marked “read” before she reads it. “My phones are tapped and a security official has told me that I’m being monitored.”

The journalist who has worked in Iran, and was imprisoned there, (personal communication, March 4, 2016), says:

We just assumed they could be listening at any time and we assumed that people we knew could or would be questioned by the authorities and perhaps pressured to give information about us … which is not a fun way to live, to always worry about that.

Independent Russian journalist Andrei Soldatov (personal communication, February 29, 2016) says that the most widespread surveillance of Russian journalists and activists in Russia is on social networks. “Everybody thinks: it seems we are all closely monitored by so many government institutions and it's better to be quite cautious. It helps to maintain this climate of self-censorship.” But there is also targeted electronic surveillance of journalists in Russia usually in the form of phone interception, and email interception by hackers who “might or might not be” allied with the Kremlin. In theory when the security services want to conduct targeted surveillance of a journalist they need a warrant from a court. But in practice the Russian security services have direct access to all of the information on telecom servers. Drawing the paranoia link to surveillance in Western democracies, Soldatov says: “Too many journalists went totally paranoid about surveillance and that's a very understandable problem for investigative journalists. And it might destroy you.”

Conclusions

Based on the testimonies of journalists from across the spectrum of liberal democracies, illiberal democracies and non-democracies examined in this paper we can establish the following comparative typology of surveillance-linked fear, for journalists covering sensitive national security topics, such as the Snowden story.

*The United States; The United Kingdom; Germany; Italy; Austria; ** Poland; Hungary; *** Turkey; Syria; Iran; Lebanon; Egypt.

Together these dynamics are resulting in an intensified chilling effect for the profession, and this is a commonality in both democratic and undemocratic countries.

While it is true that in relatively healthy democracies, many journalists tend to rate concerns about surveillance fairly low, those who do report on sensitive topics with a high public interest and impacting the futures of societies and peoples, especially those involving national security, terrorism, surveillance, intelligence agencies and organised crime share a high degree of concern about the chilling effect of surveillance on journalism, and therefore on democracy. They argue that the state of equilibrium may be tilting in favour of state entities with unprecedented surveillance powers but without any great interest in preserving democratic rights. However, it is precisely by the ability of journalists to report thoroughly, critically and in an adversarial manner on truly delicate stories, using confidential sources whose identities they are able to protect, that the health of a democracy may be measured. Where such journalism is absent, diminished or under threat, so too inevitably are the right and ability of citizenries more broadly to hold manifestly dissenting views, engage in activism, embrace individuality of thought and action.

The space for in-depth combative investigative reporting is shrinking. Combined with financial pressures on the media, surveillance creates an asphyxiating environment for investigative journalists. However, this is not merely a matter of surveillance exercised as electronically mediated observation: it is both electronic and physical, in a continuum of online and offline harassment and intimidation. My interviewees have experienced various forms of repressive control, to the degree that the political system of the country within which they work tolerates. Where there are illiberal political developments more generally, like in Hungary and Poland, the dangers are even greater. In countries that are authoritarian like Turkey, the spaces for independent watchdog journalism are disappearing or non-existent. Reporting on sensitive national security stories there can mean life in prison. In Egypt, press freedom is under greater than before the Arab Spring uprising. Iran routinely imprisons reporters on the basis of “evidence” gathered through secret monitoring. In civil war-wracked Syria reporters face death, kidnapping, torture, and arrest by both state and rebel forces. The commonality in every single country examined, from the US, to Iran, is that the pressure and repression are underpinned, to varying degrees, by surveillance.

It becomes clear that the effects of surveillance on journalists and their sources are to a great degree intangible. The interviewees pointed out that if the ability and willingness of state entities to engage in pervasive surveillance continues unchecked, it will produce long term, wide ranging psychological responses based on fear. The sense of uncertainty derived from the knowledge that institutional willingness to restore democracy is incapacitated, in turn incapacitates the media, which are becoming “more cautious”. Moreover, the fear experienced both in society and in the professional world of journalists serves to extend to severing the relation of the journalist with society. Not only the sources, but also public debate shows evidence of uniformity. Journalists and editors perceived to be a “threat to security” and prevailing political order and interests are the targets of efforts to fuel the type of mental perturbation – which they call “paranoia” – that might prompt them to reduce or cease coverage of “dangerous” topics.

In this paper, I largely concentrated on the testimonies of journalists operating in liberal, democratic countries, because I wanted to underline the fragility of modern day investigative journalism. Some of the journalists I spoke to have learned to live with the knowledge of surveillance and stated their concern is focused on protecting their sources and staying a step ahead of intelligence services in pursuing a story. This is particularly the case with journalists who come from or have worked with or are in social contact with groups under observation, whether ethnic, political and so on.

The effect of state surveillance of journalists appears to be, on an immediate level, psychological, in particular through the sparking and fuelling of fear and “paranoia” and with regard to their own personal safety, and that of their sources. On a professional level, they report hindrances and internal hesitance as a result of the fear to pursue investigative modes of work as previously. On a meso-level, they sense that journalists are becoming more cautious and more vulnerable to pressure, as a result of surveillance and financial pressures. Newsrooms are affected, as are entire media news reporting platforms. On a macro-level of impact my subjects perceive dire possible consequences for democracy as well as their relation to society. What this means is that for mature democracies, the evidence is that institutional unwillingness or incapacitation may take place gradually. In the words of Ariel Dorfman in Guernica Magazine, in 2013:

A warning for those who bask in the glow of that self-congratulatory phrase, ‘It can't happen here.’ We also chanted those words in the streets of Santiago and from the hills of Valparaíso before the coup swept our lives away. We also laboured under the delusion that our oh-so-stable democracy was exempt from the savagery of history and the depredations of an unbridled government. We also were targeted by a regime that defined dissidents as terrorists. We also consented to the degradation of our speech.

Finally, it is of course difficult to “assess how much we don't know”, i.e., to quantitively assess how many national security stories have not been covered out of fear on the part of editors and journalists with regard to the substantive or perceived surveillance powers and actions of the intelligence services. In other words, it is no easy matter to assess the concrete impact of state surveillance, in a detrimental sense, on the relationship between the deep state and national security journalists and citizens at large. In this context, further research could include a joint trans-disciplinary approach between the realms of communication, political science and psychology, with a view to seeking to identify correlations between documented surveillance of national security journalists, testimony of journalists who feel inhibited through fear as a result of surveillance actions and capabilities, and measurable erosion of democratic health in the political science sense.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank my PhD supervisor, Prof. Katharine Sarikakis, for her guidance and advice on this paper.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

2 Minorities are those understood to be pro-democracy.

3 The research also throws up important questions about the implications of a chilling effect for the future of journalism. However, they have been discussed in a separate paper which looks closely at the potential convergence of journalism and hacktivism in Western democracies in the age of surveillance. Thus, I decided to focus strongly on the fear factor and chilling effect of surveillance of journalists in Western democracies – an area that is virtually un-researched in an academic sense. This in turn allows me to critically question normative explanations and assurances offered by state entities when it is claimed, as described in the paper, that national security anti-terrorism legislation, including additional more intrusive surveillance is necessary, proportionate and helpful in democracies to enhance security without eroding democracy. I intrinsically question this suggestion.

4 Glenn Greenwald: a journalist then working for the Guardian newspaper, who interviewed Edward Snowden in Hong Kong and then participated in breaking the story, for the Guardian.

6 Sassine Square is a square in central Beirut.

References

- Agar, Jon. 2003. The Government Machine: A Revolutionary History of the Computer. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Altheide, David L. 2013. “Media Logic, Social Control, and Fear.” Communication Theory 23 (3): 223–238. doi: 10.1111/comt.12017

- Bentham, Jeremy. 1791. Panopticon; Or the Inspection-House. T. Payne: Mews Gate. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=NM4TAAAAQAAJ&pg=GBS.PP3.

- Bigo, Didier. 2014. “Security, Surveillance and Democracy.” In Routledge Handbook of Surveillance Studies, edited by Kirstie Ball, Kevin D Haggerty, and David Lyon, 277–284. London and New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Dubbeld, Lyndsey. 2003. “Observing Bodies. Camera Surveillance and the Significance of the Body.” Ethics and Information Technology 5 (3): 151–162. doi: 10.1023/B:ETIN.0000006946.01426.26

- Eley, G., R. Habermas, E. Rosenhaft, S. Weichlein, J. Wiesen, J. Zatlin, and A. Zimmerman. 2016. “Surveillance in German History.” German History 34 (2): 293–314.

- Foucault, Michel. 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=6rfP0H5TSmYC&pg=GBS.PP6.

- Friedman, Benjamin H. 2011. “Managing Fear: The Politics of Homeland Security.” Political Science Quarterly 126 (1): 77–106. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-165X.2011.tb00695.x

- Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity.

- Giroux, Henry A. 2015. “Totalitarian Paranoia in the Post-Orwellian Surveillance State.” Cultural Studies 29 (2): 108–140. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2014.917118

- Greenwald, Glenn. 2015. No Place to Hide. London, UK: Penguin Random House.

- Lyon, David. 2007. Surveillance Studies: An Overview. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Lyon, David. 2010. “Identification, Surveillance and Democracy.” In Surveillance and Democracy, edited by Kevin D. Haggerty, and Minas Samatas, 34–50. New York: Routledge.

- Lyon, David. 2015a. Surveillance After Snowden. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Lyon, David. 2015b. “The Snowden Stakes: Challenges for Understanding Surveillance Today.” Surveillance & Society 13 (2): 139–152. doi: 10.24908/ss.v13i2.5363

- Mann, Steve, and Joseph Ferenbok. 2013. “New Media and the Power Politics of Sousveillance in a Surveillance-Dominated World.” Surveillance and Society 11 (1-2): 18–34. doi: 10.24908/ss.v11i1/2.4456

- Marx, Gary T. 1971. Racial Conflict: Tension and Change in American Society. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co.

- Marx, Gary T. 2002. “What’s New About the “New Surveillance”? Classifying for Change and Continuity.” Surveillance & Society 1 (1): 9–29. doi: 10.24908/ss.v1i1.3391

- Monahan, Torin. 2006. Surveillance and Security: Technological Politics and Power in Everyday Life. New York: Routledge.

- Nagy, Veronika. 2017. How to silence the lambs?—Constructing authoritarian governance in posttransitional Hungary. Surveillance & Society 15 (3/4): 447–455.

- Pen America. 2014. “Global Chilling: The Effect of Mass Surveillance on International Writers.” Accessed July 4, 2017. https://pen.org/global-chilling-the-impact-of-mass-surveillance-on-international-writers/.

- Russel, Adrienne, Risto Kunelius, Heikki Heikkila, and Dmitry Yagodin, eds. 2017. Journalism and the NSA Revelations: Privacy, Security & the Press. London, UK: I.B. Tauris.

- Staples, William G. 2000. Everyday Surveillance: Vigilance and Visibility in Postmodern Life. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Stoycheff, Elisabeth. 2016. “Under Surveillance: Examining Facebook’s Spiral of Silence Effects in the Wake of NSA Internet Monitoring.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. Epub ahead of print, March 8, 2016. doi:10.1177/1077699016630255.

- Thomas, Jim. 1981. “Class, State, and Political Surveillance: Liberal Democracy and Structural Contradictions.” Critical Sociology 10-11 (4-1): 47–58.

- Weller, Toni. 2014. “The Information State: An Historical Perspective on Surveillance.” In Routledge Handbook of Surveillance Studies, edited by Kirstie Ball, Kevin D. Haggerty, and David Lyon, 277–284.

- White, Gregory L., and Philip P. G. Zimbardo. 1980. “The Effects of Threat of Surveillance and Actual Surveillance on Expressed Opinions Toward Marijuana.” The Journal of Social Psychology 111 (1): 49–61. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1980.9924272