ABSTRACT

Sources are an essential component to journalistic reporting and are a critical determinant of its quality. Who or what is referenced, in which ways, how often, and why matters and can reveal important insights into journalistic practice as well as the values and implicit assumptions of both the news outlets and broader societies under study. Acknowledging this, this study examines sourcing practices of journalists working at four national news outlets in Australia over a 15-month period as they report on the topic of ageing and aged care. Specifically, the study investigates six key questions related to sourcing: Who or what is used as a source? What is the proportion of elite to non-elite sources? What is the identifiability of sources? What is the number of sources per news story? What is the proportion of primary to secondary sources per story? And how are these aspects different for different news outlets? The results reveal that journalists overwhelmingly used elite rather than non-elite sources in their reporting on this topic, used politicians most frequently in their coverage, and used an average of five sources per article. However, who was used as a source varied markedly by outlet.

Introduction

Sources—best defined as individuals, organisations, documents, or other artefacts that provide information—are an essential component of journalistic reporting and are a critical determinant of news quality (Manninen Citation2017). Who or what is referenced, in which ways, how often, and why matters and can reveal important insights into journalistic practice, as well as the values and taken-for-granted assumptions of both the news outlets and broader societies under study. Each of the choices that a journalist makes about the sources they seek affects the news narrative that is possible, and its resulting reception.

Journalistic sources come in a variety of formats with various constraints and affordances. For example, the source might volunteer itself in the case of media releases, press conferences, through an outlet’s “submit a tip” function, or through direct contact with the journalist. Alternatively, the journalist might try to recruit sources through personal or professional contacts, or by seeking comment from experts, public figures, or community leaders.

Sources can be animate in the case of people, or inanimate in the case of policy submissions, reports, and meeting minutes, which can be directly quoted or summarised. Sources can exist in raw data that journalists have to sift through to find newsworthy stories, or can exist in polished talking points provided by media offices. Journalists can seek to interview relevant people and thus create primary source material, or they can rely on already-published content and re-use secondary source material. Journalists can rely on a single source or can integrate dozens to craft a richer and more holistic account. They can interview high-status individuals (so-called “elite” sources) or ordinary citizens (non-elite sources). They can focus on a particular identity attribute or source characteristic consciously or unconsciously.

Questions of access to the source and its identifiability frequently come into play as well. Some democratic sources are freely available online, whereas others require in-person access or can only be accessed at certain times. Some sources are identifiable and happy to be directly quoted or referenced by name in resulting coverage. Others, in the case of whistleblowers or people providing information during other sensitive contexts, might negotiate to have their identity shielded from public disclosure or not be known to the journalist at all. Some source material requires considerable skill or expertise to access, analyse, or interpret, and some even requires legal intervention, such as a Freedom of Information request, to access.

In all cases, the sourcing decisions journalists make (or are able to make based on institutional support, time constraints, and resource considerations) have marked effects on the journalistic product produced and are important aspects to study in order to illuminate the state of contemporary journalistic practice, and raise awareness of these considerations for journalists and news consumers alike (Wheatley Citation2020).

The present study investigates six key questions related to sourcing within the context of aged care coverage: who or what is used as a source? What is the proportion of elite to non-elite sources? What is the identifiability of sources? What is the number of sources per news story? What is the proportion of primary to secondary sources per story? And how are these aspects different for different news outlets? Critically, this study asks these questions in the context of an under-represented topic, ageing and aged care, by examining reporting on this topic from four national Australian news outlets over a 15-month period. News media representations of ageing are important because age is one of the most universal attributes that links humanity together. Unlike characteristics such as gender, ethnic background, and socio-economic class that differ and have the potential to divide, ageing is the constant that all humans share and must reconcile themselves with. To ignore ageing and representations of older people is to spurn one’s future and the ancestors who have come before. News media depictions offer those without direct experience a window into what it is like to grow older and to live in aged care settings (Gilbert Citation2021). Media influence our knowledge of and perspectives toward ageing and aged care and, for these reasons, it is important to study how journalists represent this demographic. Close attention to journalists’ sourcing practices provides one such opportunity.

In order to provide a rich foundation upon which this study can further build, the subsequent literature review begins with an overview of trends in the coverage of ageing and aged care and follows with an overview of literature on journalistic sourcing. Next, it introduces the “hierarchy of influences model”, a framework for identifying influence in the media first introduced by Shoemaker and Reese for mass communication (Citation1991) and employed here as a conceptual—theoretical framework to guide the study’s further development and inform its research questions.

Literature Review

Trends in the Coverage of Ageing and Aged Care

Ageism is widespread globally, and reflected in media discourse across channels and formats. Researchers who analysed a corpus of more than one billion words gathered from television, fiction, magazines, and newspapers across the world’s largest media conglomerates in the US (from 1990-the present) and the UK (from 1980–2007) found that the number of negative descriptions of older adults outnumbered positive ones by a ratio of 6:1 (Ng Citation2021). This study followed a call in 2016 by 194 World Health Organisation member states to develop a global campaign to combat ageism due to its global prevalence (World Health Organization Citation2021).

Past research has found that journalists rarely represent “ordinary” (non-elite) older people (Torben-Nielsen and Russ-Mohl Citation2012) and, when journalists do include them in their coverage, they tend to show them as dependent, frail, lonely, and in cognitive decline (Köttl, Tatzer, and Ayalon Citation2021). In New Zealand, researchers who have examined news coverage of older people found that journalists tended to refer to this group as a “nameless, homogenous ‘other’ group” (Morgan et al. Citation2021). Journalists also tend to depict older people as being powerless, vulnerable, and a “burden” on society (Amundsen Citation2022). Cross-cultural research that examined Australian, American, and British news coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic found that journalists across all these locations were complicit in age discrimination and sometimes tended to “cast blame” toward older people as a cohort who had “outlived its usefulness” or had “profited at the expense of younger generations” (Lichtenstein Citation2021).

Within Australia, journalists focus less on aged care compared to other topics, and are more likely to focus on the “consonance” news value and show older people in stereotypical or disempowering ways (Connolly Citation2019; Thomson, Miller, et al. Citation2022a; Thomson, Johnstone, et al. Citation2022). Australian journalists are also far more likely to focus on the economic or political implications of aged care compared to the social implications (Imran and Bowd Citation2022). In visual depictions that Australian journalists integrate into their coverage of aged care, older people were more likely to be de-personalised and de-identified compared to other demographics (Thomson et al. Citation2022a, Thomson et al. Citation2022b).

In Australia, news coverage of older people and the aged care sector are overwhelmingly covered by generalist reporters or, for larger and better-resourced organisations, more specialised “social affairs” journalists who, however, still have a relatively large remit that can include a range of topics such as ageing, disability, welfare, immigration, free speech, health, industrial relations, and population policy. Medium- and smaller-size news outlets often lack these specialised roles entirely and even the largest national outlets do not employ reporters who are focused exclusively on the coverage of ageing and aged care. In the words of Anne Connolly, who has won six Walkleys and scores of other awards for social affairs reporting and who is a journalist working in the investigations unit at Australia’s public broadcaster, the ABC:

Very few people have any specialist knowledge of it [aged care]. And if you don't have specialist knowledge, you don't know what's new, what's interesting, what's sensational, what's outrageous. You don't know. And so therefore, you can't report on it properly (personal communication, Sept 1, 2022).

I think if you looked at the banking Royal Commission, and if you looked at the, you know, the child sexual abuse by institutions [Royal Commission], they had dedicated reporters who had a history and they understood what was happening, and they had the knowledge of it, and they could report effectively. That didn’t happen with aged care (personal communication, Sept 1, 2022).

Journalistic Sourcing

Journalistic sourcing—who or what the journalist directly quotes or indirectly references—affects the stories that are possible, as well as their framing (Hickerson, Moy, and Dunsmore Citation2011). A review of the journalistic sourcing literature reveals various trends and patterns related to these practices. Specifically, three strands of research dominate the scholarly study of journalistic sourcing (Broersma, Den Herder, and Schohaus Citation2013). These include studies on (1) how journalists obtain their information, (2) who or what journalists use as sources, and (3) what is the interaction between journalists and their sources, which is usually studied through settings like live television or press conferences. The present study sits in these first two strands and contributes to the scholarship on how journalists obtain their information about a volatile topic like aged care and on who journalists use as sources given the unique difficulties of reporting on this topic.

How do journalists obtain their information? Within this first strand—how journalists obtain their information—scholars have identified efficiency (Tandoc and Duffy Citation2019; Van Leuven et al. Citation2018) and a desire for legitimacy, as well as potentially a desire to not appear biased (Hickerson, Moy, and Dunsmore Citation2011) as key driving forces. Where journalists turn to for sources can affect a story’s perceived credibility. Audiences tend to perceive secondary social media sources, for example, as less credible than primary sources (Lecheler and Kruikemeier Citation2016; Flew et al. Citation2020). This is due, in part, to the novelty of online publishing channels. As most anyone with internet access can create a Twitter account, the publishing channel has low novelty. This contrasts with information published on news websites, which has higher novelty, since only select gatekeepers can publish content on these sites. The perceived expertise and trustworthiness of a source also affects how credible it appears (Lecheler and Kruikemeier Citation2016; Flew et al. Citation2020). Lastly, journalists’ sourcing practices can also influence perceptions of media credibility and, subsequently, media trust, which has implications for the smooth functioning of democratic systems (Tsfati and Cappella Citation2003).

Some aspects of the aged care industry in Australia uniquely affect journalists’ sourcing practices and opportunities. For example, the previously mentioned deadline pressure that most Australian journalists face impacts which sources journalists rely on. In ABC journalist Anne Connolly’s words: “the media, you know, if they're doing a same-day story, they don't have any choice, they have to go to those [elite] sources” (personal communication, Sept 1, 2022). In addition to deadline pressures, the complexity of the topic, and the lack of specialised understanding, there are also difficulties with access to the aged care homes and facilities where older people live and with being able to interview older people who have dementia or other issues that can prevent them from sharing their stories. Beyond this, a culture of fear pervades the sector and can prevent those adjacent to aged care, such as staff members and family members, from speaking out. In Connolly’s words:

So there was a lot of fear. And and there still is, and, and then there were family members, family members who had people still in care who did not want to talk, either, because they were fearful of repercussions. So it came down to ex-staff and families whose loved one had died (personal communication, Sept 1, 2022).

Who or what is a journalistic source? Within this second strand—who or what do journalists use as sources—past research has found that journalists seek “authoritative” data from experts and officials (Berkowitz Citation2019). This often leads to legitimising and reifying existing power structures and ideological systems (Manning Citation2001). Journalists, reliant on routines to make their reporting more efficient, also tend to rely on the same sources over and over again in their coverage (Waters, Tindall, and Morton Citation2010; Phillips Citation2010; Matthews Citation2013). This is especially true for sources they have met in real life (Schapals and Harb Citation2020). When journalists do this, they can perpetuate largely unquestioned consensus views and “conventional wisdom” upheld by elites, which Atton and Wickenden (Citation2005) define as entities who are “both easily found and considered credible through their structural positioning and representative status” (348). Given this definition, elites include thought leaders such as academics and business CEOs, politicians, and public servants. Relying on a narrow range of sources can falsely simplify and distill a more complex and diverse discourse (Hickerson, Moy, and Dunsmore Citation2011).

Sourcing studies often focus on aspects of voice (that is, representation, and who is featured and who is not in news reporting), gender, and empowerment (Berkowitz Citation2019). These studies have found that journalistic sources tend to be male and from non-minority groups (Ross Citation2007; Global Media Monitoring Project Citation2020). Sourcing studies also have focused on the occupation or affiliation of those being quoted or referenced. O'Neill and O’Connor’s (Citation2008) study of 2,979 British print and digital news stories, for example, found that government sources were the third-most popular (after police and court sources). Many sourcing studies focus only on individually named people as sources rather than reports, statements, or raw data from organisations (see Tenenboim-Weinblatt and Baden Citation2018, as a notable exception to this pattern). Thus, this study, advances the scholarly understanding of sourcing by extending the focus on sourcing from people to organisations and raw materials that are integrated into the news.

Past studies have demonstrated that source confidentiality is important to journalists (Berkowitz, Limor, and Singer Citation2004; Matthews Citation2013) so our own study seeks to identify the proportion of named to unnamed sources with a volatile topic like aged care coverage to provide more concrete understanding of how much concerns over source confidentiality affect routine journalistic practice.

The Hierarchy of Influences Model

Numerous forces influence what is news and how it ends up being shaped and presented. The hierarchy of influences model, which has also been called a “theoretical perspective” (Reese Citation2019, 1), proposes five levels that explain how news content is shaped: the individual, routine, organisational, social-institutional, and social systems levels. The present study is interested in a key journalistic practice—sourcing—which perhaps sits most dominantly in the first level but, in fact, potentially transcends all of them. Those in this first level—journalists in this case—can identify with some autonomy the specific individuals, documents, or other pieces of evidence they wish to incorporate into their reporting and build a news narrative around. However, their ability to do so can be advanced or stymied by other individuals acting alone or as part of larger organisations. Sources can decline an interview invitation or can recommend the journalist contact someone else. Individuals can also, most often in the case of collectives such as corporations or advocacy groups, invite themselves as sources by generating press releases or holding media events when they wish to attract attention to a certain issue or topic. And a journalist’s ability to consult a certain source can be enabled or constrained by various routines and organisational influences or pressures. In the case of accessing archival materials, these might not be able to be a source for breaking news stories if these materials are not digitised and made available online, or if the cost to find, retrieve, copy, and potentially redact materials is too great for the organisation to bear. Conversely, sometimes access is preferentially granted (or made economically possible) only to journalists and news organisations, but not to ordinary citizens. At the more macro end of the spectrum, culturally conditioned power imbalances or inequalities, as they relate to age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexuality, ability, socio-economic status, and more, can impact who the dominant sources for a society are, either overall or for specific topics that society perceives as being gendered, raced, abled, or classed in certain ways (Romano Citation2021).

Acknowledging this, the present study interrogates the practice of sourcing within the under-studied domain of aged care news coverage. It identifies which sources journalists rely on most frequently, the prevalence of anonymous or non-identified sources, the depth and diversity of journalists’ sourcing practices, the prevalence of primary to secondary sources, and the relationship between media ownership and sourcing practices. This study goes beyond a consideration of the range of sources that journalists draw on to also consider how the source or sources are used—such as if they are primary or secondary, identified within a text or anonymised, etc—which are questions of “modality” and “technique”, as termed by Lecheler and Kruikemeier (Citation2016).

Five research questions guide the project’s analysis:

RQ1: Which sources did journalists at four national news outlets (The Saturday Paper, The Guardian Australia, The Australian, and the ABC) use in their news coverage of the aged care sector during the first half of the Aged Care Royal Commission from 1 October, 2018, through 31 December, 2019? What was the proportion of elite to non-elite sources used?

RQ1A: What is the identifiability of the journalists’ sources in this sample?

RQ1B: How many sources are included, on average, in the articles across outlets?

RQ1C: What is the proportion of primary to secondary sources that journalists relied on and integrated into their news coverage of the aged care sector during the time period from 1 October, 2018, through 31 December, 2019?

RQ1D: What is the relationship, if any, between outlet ownership and the type or diversity of sources it uses in royal commission-related coverage?

Methods

The study implemented a purposive sampling strategy (Etikan, Musa, and Alkassim Citation2016) to shed light on the sourcing practices of journalists from four national Australian outlets, including The Saturday Paper, The Guardian Australia, The Australian, and the ABC, which reported aged-care related news between 1 October 2018 and 11 June 2021 (please see for an overview of these outlets and their audiences). This timeline was determined based on the establishment of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety in October 2018 through to 11 June 2021 as this was approximately four weeks after the government’s response to the Royal Commission. The study focuses on national news outlets because of their greater audience reach and potential to influence the country’s conversation on a nationally salient topic such as aged care. Within these national news outlets, attention was also paid to media ownership in order to provide a diverse array of national outlets to compare and contrast. As such, the sample reflects both publicly funded news media (in the case of The ABC) and those that are privately owned (in the case of The Australian, The Guardian Australia, and The Saturday Paper). Within these privately owned outlets, there is also diversity in who owns these (News Corp Australia, Schwartz Publishing, and the Guardian Media Group).

Table 1. Overview of outlets in the sample.

No single database offered access to all of the articles from these outlets, so multiple databases were used to construct the data sample. Specifically, articles from The Guardian Australia were sourced from Proquest, articles from the ABC and The Australian were sourced from Factiva, and articles from The Saturday Paper were sourced from PressReader. In all cases, the same keywords (“aged care”, “Royal Commission”, “home care”, and/or “elder abuse”)Footnote1 were used. Not all these keywords, such as “elder abuse”, returned search results, however, but the full range of search keywords is reported in the interests of transparency. The study’s first two authors consulted a nationally leading Australian aged care advocate to determine these keywords and to ensure that the coverage would be inclusive of both residential care (which accounts for about two-thirds of the sector) and home care settings. These keywords also included coverage related to the Royal Commission and its hearings or reports as well as reporting on the conditions and issues in the aged care sector more broadly.

The search for these keywords yielded 144 The from The Saturday Paper, 96 results from The Guardian Australia, 479 results from The Australian, and 278 results from The ABC. Each of these results was reviewed manually to ensure its quality (operationalised as having at least one paragraph dedicated to the topic of aged care) and relevance. Only news articles written by journalists were included. As such, letters, opinion pieces, editorials, or guest columns written by politicians were excluded. After cleaning, the sample at this point included 303 articles (including 21 from The Saturday Paper, 31 from The Guardian Australia, 119 from The Australian, and 172 from the ABC).

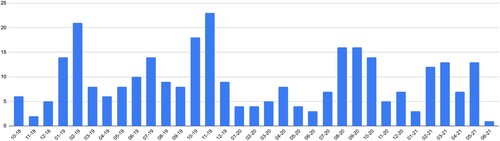

However, it soon became apparent that the volume of coverage was too great to analyse due to the time-intensive nature of manually coding each article for each source, determining its type (politician, aged care worker, aged care resident, etc), its identifiability, its frequency, and its nature (as a primary or secondary source). As such, to inform the selection of an appropriate and feasible sampling frame, the research team generated a column graph of coverage frequency to visualise the volume and distribution of coverage over time during this nearly three-year time period (see ).

Figure 1. National news distribution of aged care coverage.

Note: Journalists at national news outlets wrote an average of 9.18 articles per month focused on aged care during the 33-month period from October 2018 through June 2021. The range was from 1 (in June 2021) through 23 (in November 2019).

Based on a review of the distribution of coverage as well as an understanding of key events that happened within this timeframe, the team selected a 15-month period to analyse (October 2018 through December 2019). This timeframe accounted for a majority of the articles (161 of the 303 articles, 53.1 percent) in the sample even though this frame included only 15 of the possible 33 months. It also included two critical milestones related to aged care in Australia. The first is the announcement in October 2018 of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, and the second is the release in October 2019 of the Commission’s interim report, Neglect. The volume of coverage visualisation was consulted to determine the end point of analysis (31 December, 2019), once coverage had dropped off.

Journalists at national Australian news outlets (The Saturday Paper, The Guardian Australia, the ABC, and The Australian) published articles on aged care 196 times during the 15-month period between 1 October, 2018, and 31 December, 2019. This was the period with the highest volume of coverage over the 33-month period from the calling of the Royal Commission in October 2018 through four weeks after the government’s response to the Commission’s findings in June 2021. The distribution of these articles was, in descending order, 100 articles from the ABC, 85 from The Australian, 8 from The Guardian Australia, and three from The Saturday Paper. Regarding story lengths, the range for articles in The Australian’s online coverage was from 185 to 2,187 words and the average length was 567.15 words. The range for The Guardian Australia was from 385 to 1,460 and the average length was 780.12. The range for the ABC was from 116 to 3,652 words and the average length was 821.25. Lastly, the range for articles in The Saturday Paper was from 1,344 to 3,176 words and the average length was 2,044.23.

The study’s second author began the analysis phase by reading the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety Report and the government’s response to it so that they could be sensitive to the issues, stakeholders, and historical forces that shaped the present Commission. Analysis continued with a close reading of the articles by the study’s second author to orient the research team with the breadth and depth of coverage in the sample. Following this, a manual coding process commenced that examined each article for five variables related to sourcing.

Specifically, each source in each article was noted and was first coded for its type. This was done in the first instance with specific names of people (e.g., QLD Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk) or organisations (e.g., the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission). However, due to the high number of sources (in excess of 900 for this sample), these were later collapsed into “umbrella” source categories of similar source types. For example, “peak bodies” was an umbrella category that included Aged and Community Services Australia (ACSA); the Council on the Ageing (COTA); Leading Age Services Australia (LASA); the Aged Care Guild; and regional peak bodies, such as the NT Council on Ageing. Similarly, journalists used numerous politicians and political bodies, including federal ministers, political parties, the prime minister, state premiers, and senators, as sources. However, these were all eventually collapsed into an umbrella “politician” category. Second, the eliteness of the source was determined and coded. High-status or high-power individuals, such as politicians, peak bodies, academics, and Royal Commissioners were coded as elite sources. Individuals with lower status or power, such as affected family members, aged care workers, and aged care residents, were coded as non-elite sources. Third, source identifiability was determined and coded for. This included assessing whether the journalist used an identifiable source (e.g., “Jane Smith said … ”) or non-identifiable source (e.g., “sources close to the topic said”). Fourth, the number of sources per article were tallied and coded. Fifth and finally, the source’s status as primary or secondary was determined (when possible) and coded for. This assessment was sometimes aided by explicit acknowledgement (e.g., “a spokesperson for the premier told the ABC … ”) and by the context surrounding the reference (e.g., “In a new submission to the aged-care commission, advocacy group National Seniors warned that regulation in the industry had been ‘captured by providers and their owners … ’”).

Findings

Across all four national outlets in the sample, a total of 974 sources were used by journalists covering aged care-related topics from the period of 1 October, 2018, through 31 December, 2019. These 974 sources spanned 92 unique “umbrella” source categories. Sources that were used 5 or more times comprised 76 percent (n = 741) of the sample. The first research question was interested in which sources journalists relied on and in the proportion between use of elite and non-elite sources.

The most frequently used sources, in descending order, over this time frame included politicians, affected family members, residential aged care providers, peak bodies, academics, counsel assisting the Royal Commission, aged care workers and medical professionals, aged care residents, unions, the Australian Government Department of Health, the Royal Commissioners, documents and other materials from the Royal Commission, the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, and doctors and nurses from hospitals. Full breakdowns of these most frequently used sources, including raw frequencies and percentages, can be found in . The present study contrasts with Harkin, Charlton, and Lindgren’s (Citation2018) longitudinal study of print and daily news coverage about older Australian drivers, which found legal sources and ordinary citizens were tied as the most-sourced entities with 17 percent of the sample each. (However, Harkin, Charlton, & Lindgren only evaluated the first source referenced in each article so it remains unclear if this divergence would remain if all the sources in their study had been evaluated).

Table 2. Most frequently used sources.

Journalists relied on elite sources, such as politicians, government and institutional sources, academics and healthcare experts, in 79.7 percent of cases. Conversely, they relied on non-elite sources, including aged care residents, affected family members, and aged care workers, in only 20.3 percent (n = 198) of cases. This number is much higher than the proportion (51.80 percent) that Kleemans, Schaap, and Hermans (Citation2017) found in their longitudinal analysis of 1,425 Dutch television news stories. This suggests that the reporting medium (online news rather than broadcast television news) and the coverage topic are likely both influential in determining journalists’ sourcing approaches. Anne Connolly, the ABC investigative journalist, said the day-turn nature of much journalistic work combined with reporter’s own convictions about which voices are most important also affected journalists’ sourcing decisions. In her words:

The media, you know, if they're doing a same-day story, they don't have any choice, they have to go to those [elite] sources. That's why the royal commission should have been an opportunity for them to quote more directly real people. But I don't think real people got much of this. I just, I don't think there were too many witnesses … I didn't want to hear from officials. I wanted to hear from people on the ground. So I made a point of interviewing, simply the relatives, the residents, if they were able, staff (personal communication, Sept 1, 2022).

Sourcing Identifiability

As acknowledged earlier, access is an understandably complex and sometimes difficult question for a topic like aged care where physical access to aged care residents and workers is often restricted, where cognitive decline or disability can limit the aged care residents’ capacity to communicate their own experiences, and where institutional policies and pressures create “chilling effect” conditions such that aged care workers or residents feel vulnerable about sharing their perspectives with the news media for fear of retribution. The use of non-identifiable or “anonymous” sources can be a mechanism journalists can use to navigate some of these challenges. The use and prevalence of non-identifiable sources is thus the second research question’s focus.

The analysis found that journalists used non-identifiable sources relatively rarely. Across the 196 articles in the sample that were written over 15 months, journalists used non-identifiable sources 38 times or in 3.9 percent of cases. When journalists relied on non-identifiable sources, they did so with aged care workers and medical professionals (in 18 instances), with industry experts (in eight instances), with advocates (in eight instances), and, with one instance each, a National Disability Insurance Agency’s spokesperson, a Northern Territory Health spokesperson, a public servant, and a Department of Health whistleblower. Interestingly, the non-identifiable sources weren’t used exclusively for non-elite sources but were also extended in some cases to industry experts and official spokespeople for government or corporate institutions. When examined organisation by organisation, the ABC led with the highest number of non-identifiable sources (n = 27; 71 percent of all non-identifiable sources). It was followed by The Saturday Paper with six non-identifiable sources (15.7 percent) and The Australian with five (13.1 percent). The Guardian Australia was alone in using no non-identifiable sources. These findings contrast markedly with Matthews’s (Citation2013) study of 1,028 sources in British press coverage of alleged terrorist plots, which found that so-called “veiled attributions” (where an organisation or generic title was named rather than a specific individual’s name) varied from as few as 18 percent (with government sources) to as many as 96 percent (with security sources).

Sourcing Richness and Diversity

This study’s third research question was interested in the richness and diversity of sources that journalists used. Regarding this first concept, sourcing richness is operationalised in this paper as the number of sources per article, which will be presented overall and by outlet. Journalists in the sample used just under five (approximately 4.96) sources, on average, across all 196 articles in the sample. By raw numbers, The ABC used the most sources (n = 575), and was followed by The Australian (with n = 314), The Saturday Paper (with n = 46), and The Guardian Australia (with n = 31).

The ABC accounted for only 51 percent of the articles in the sample but represented 59.2 percent of all sources used. In contrast, The Australian accounted for 43.3 percent of the sample but represented only 32.5 percent of all sources used. The Saturday Paper only accounted for 1.5 percent of all the articles in the sample but represented 4.7 percent of all the sources used. And The Guardian Australia represented 4 percent of all the articles in the sample but represented only 3.2 percent of all the sources used. Thus, when the number of sources per article are averaged by outlet, the ABC and The Saturday Paper sourced above average relative to their share of the articles while The Australian and The Guardian Australia sourced below average relative to their share of the articles. These findings stand in marked contrast to Kleemans, Shaap, and Hermans’s (2017) work, which found that nearly a third of their sample of 1,425 news stories did not include sources at all. This speaks, again, to the medium-specific nature of reporting practices as television news, for example, has been found to be less “densely sourced” (Schudson and Dokoupil Citation2007, january/february) compared to other media. The present study is, however, more in line with Harkin, Charlton, and Lindgren’s (Citation2018) longitudinal study of print and daily news coverage about older Australian drivers which found that, overall, 87 percent of articles in the sample had at least one source. (The range in Harkin, et al.’s study varied year-to-year from 83–97 percent).

In comparing the average number of sources used, per outlet, The Saturday Paper led with 15.33 sources per article, on average. Next was the ABC, which used an average of 5.75 sources per article, The Guardian Australia used 3.875 and The Australian used 3.69 sources per article, on average. It is relevant to note here that The Saturday Paper describes itself as an outlet committed to long-form journalism and in-depth coverage. It is also a weekly outlet compared to the other outlets that have printed editions, which are dailies. Thus, the high number of sources for articles published by The Saturday Paper is not surprising given the longer article lengths and the less intense deadline pressures its journalists face compared to journalists working on 24-hour news cycles and writing comparatively shorter articles.

Source diversity was another consideration, examined here in terms of the type of sources that were used by drawing from the list of 92 “umbrella” source categories that were found during data analysis. Of these, the seven most-popular source categories are presented and compared across the outlets (see ). These most-popular source categories were affected family members, residential aged care providers, politicians, academics, peak bodies, people in aged care, and counsel assisting the Royal Commission. Due to the high number of source type categories and space limitations within this paper, a full reporting of source diversity is not possible here.

Table 3. The most popular seven source types by national news outlet.

Source numbers have been normalised into percentages as an average share of the outlet’s total sources, due to the differing number of articles in each outlet in the sample and to enable comparison across the four outlets.

The approach to examining diversity here is different to that taken in some other studies such as Romano (Citation2021), which examine this concept in terms of attributes like gender and race or ethnicity. For this study, however, this would be difficult, if not impossible, to determine without self-reported data on how the identifiable sources identify.

As illustrates, different national news outlets in the sample favoured different source types, which allows for an exploration of how outlet ownership affects editorial coverage through source diversity. The ABC led the national coverage with the highest number of non-elite sources (affected family members and people in aged care). In the case of using affected family members as sources, it relied on this source type more than twice as much as did any other outlet. In contrast, the preferred source type for both The Guardian Australia and The Australian was politicians, which comprised nearly one-third and one-fifth of all their sources, respectively. The Guardian Australia used political sources more than seven times as often compared to The Saturday Paper, 1.7 times as often compared to The Australian, and 3.8 times more often compared to the ABC. The Saturday Paper’s preferred source was academics, which it used for nearly one-third of its sources. In contrast, The Australian used academic sources in only 4.1 percent of cases, second only to people in aged care, which it used in 3.1 percent of cases.

Reliance on Primary and Secondary Sources

The study’s fourth research question was interested in the proportion of primary to secondary sources that journalists relied on and integrated into their news coverage of the aged care sector during the period from 1 October, 2018, through 31 December, 2019. Journalists in the sample exhibited a slight preference for secondary over primary sources. They used these in 55.4 percent (n = 527) of cases. Primary sources were used for the remaining 44.5 percent of cases. (The nature of seven sources was indeterminate.) The present study contrasts with O'Neill and O’Connor’s (Citation2008) study of 2,979 British print and digital news stories, which found that 76 percent of these articles used primary sources and only 24 percent used secondary sources. This suggests that the proliferation of online sources and source materials is having an effect on journalists' day-to-day sourcing practices and that the stories in this sample likely had more nuanced views rather than being dominated by an often single primary source, as was the case with O’Neill & O’Connor’s study.

We present below the top primary sources (those that were used five times or more) and follow this with the top secondary sources (again those that were used five or more times).

The top primary sources journalists relied on, overall, included affected family members (n = 60), peak bodies (n = 57), politicians (n = 54), academics (n = 50), residential aged care providers (n = 34), people in aged care (n = 25), aged care workers and medical professionals (n = 21), doctors and nurses from hospitals (n = 11), unions in aged care (n = 11), National Seniors (n = 6), the Royal Flying Doctor Service (n = 6), Real Care The Second Time Around programme staff (n = 5), and counsel assisting the Royal Commission (n = 5).

The top secondary sources journalists relied on, overall, included politicians (n = 67), residential aged care providers (n = 57), affected family members (n = 52), counsel assisting the Royal Commission (n = 42), the Australian Department of Health (n = 27), the Royal Commissioners (n = 26), peak bodies (n = 26), aged care workers and medical professionals (n = 25), the Royal Commission documents and materials (n = 22), unions (n = 20), academics (n = 18), the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission (n = 12), aged care residents (n = 15), industry experts and sources (n = 7), Human Rights Watch (n = 6), public advocates (n = 6), CPSA (n = 5), Stewart Brown (n = 5), and the Royal Flying Doctor Service (n = 5).

These findings ultimately reflect a society that is unwilling to dedicate the time and resources to reporting on ageing and aged care to the same level as other demographics (e.g., youth) and topics (e.g., banking and finance). This reflects the entrenched ageism that seems to span borders and boundaries. The findings also reflect the medium-specific nature of print and digital news, which is denser in sourcing than other media, and the proliferation of online sources and materials that can be integrated into reporting as secondary sources, which provides opportunity for more nuanced framing. Lastly, while these findings converge with the longstanding trend of privileging elite sources, they also buck the trend of relying more heavily on anonymous and de-identifiable sources which are more prevalent in other media systems and topics, leading to more accountability and credibility.

Discussion

For community members who lack direct and firsthand experience with ageing and aged care, one of their primary windows into these attributes and experiences comes through news media depictions (Gilbert, Citation2021). Media influence our knowledge of and perspectives toward ageing and aged care; for these reasons, journalists have a responsibility to ensure their sourcing practices aren’t arbitrary, based solely on convenience, or draw on established and elite sources to the exclusion of other voices. Instead, awareness of considerations like source diversity, richness, and identifiability should actively shape and inform journalists’ coverage and lead to representations that are more holistic, nuanced, and comprehensive.

Beyond the Elites: Source Aged Care Residents Directly

This study revealed journalists’ preferences for elite sources across all outlets. Significantly, the people who are most intimately connected to and affected by aged care on a daily basis—aged care residents and aged care workers—were the 7th and 8th most-popular sources, respectively, that journalists relied on. Journalists in this sample were three times more likely to quote a politician than to quote an aged care resident. This is significant. Although politicians should be accountable and have a role to play in ensuring older people are seen, heard, and appropriately cared for in their later years, older people and the workforce that cares for them—overwhelmingly comprising younger women who are also often part of culturally and linguistically diverse communities (Department of Health Citation2020)—are largely invisible from public dialogues about ageing and aged care. The public discourse on aged care should not be only shaped by elites, including politicians, academics, and peak body representatives. Rather, it needs to be a topic where the perspectives and voices of older people and their carers are also heard. Journalists covering aged care and associated issues must take great care to avoid bias against older people, and to examine any institutional or individual ageism that may contribute to the marginalisation of older people’s voices (and their carers) in coverage about them.

Resources—both in terms of time and in terms of professional networks and contacts—can affect sourcing practices, as can institutional values and organisational routines (Shoemaker and Reese Citation1991). For news outlets concerned with plummeting levels of audience trust (Flew et al. Citation2020), it is imperative that organisations invest sufficiently in their reporting talent and the resources that allow them to do their jobs. At a larger level, organisations must also examine their own values and how these affect their coverage (as discussed further in the “Beyond biased sourcing practices” section) if they desire to uphold the MEAA Journalist Code of Ethics that states reporters should not “allow personal interest, or any belief, commitment, payment, gift or benefit, to undermine your accuracy, fairness, or independence” and to prevent “advertising or other commercial considerations” to undermine the same (MEAA Citation2022).

A comprehensive understanding of each outlet’s resourcing is not clear as revenue is either not publicly reported at all for some of the parent companies (Schwartz Media, Guardian Media Group) or is reported for the parent company (News Corp Australia) only and not the individual masthead (The Australian) in the sample. Despite this, the ABC reported an income of $38.3 million in the 2018–19 financial year and, while it certainly isn’t flush with cash, it does seem to prioritise quality over quantity. This is evidenced by the approach of Anne Connolly, the investigative reporter, who, as mentioned earlier, followed three people with dementia over a year for a story, Journey of No Return. At least for those in the ABC’s investigations unit, it appears these journalists enjoy more time and resources than the bulk of journalists who don’t have time or training to do investigative reporting and are instead largely doing day-turn work.

Journalists ultimately do not have direct control over who will consent to being a source, but they do have an obligation to ensure that non-elite and vulnerable sources are given the opportunity to share their perspectives and, when relevant, to do so in a way that minimises the potential risk of harm or repercussion for them doing so. News organisations like the ABC and The Guardian Australia advertise confidential and/or anonymous pathways for sharing newsworthy information and these outlets should be lauded for such practices. But even if a journalist’s news outlet doesn’t provide this institutional support, individual journalists can use encrypted messaging platforms like ProtonMail (a practice The Saturday Paper supports) or Signal to provide would-be sources more secure ways to share sensitive information. At the same time, reporters need to be aware of a source’s digital literacies and ensure that these aren’t a barrier to participating safely in the national conversation on aged care quality.

Beyond Shallow Coverage

Recalling that both The Australian and The Guardian Australia used sources, on average, one-third less often than did the ABC, the question of sourcing richness and its effect on audiences is important to consider. The ABC is the news brand that enjoys the highest trust among Australians (Flew et al. Citation2020), although this is likely the result of many factors, such as its public funding model and the perceived rigour of its editorial processes. In addition to these factors, the depth of its reporting and the way journalists use sources can also affect trust. Research conducted in 2019 on trust in Australian news identified that, after inaccuracies, “opinionated journalists”, a “lack of transparency”, and “advocacy of particular points of view on contentious issues” were the top three drivers of mistrust in a news source (Flew et al. Citation2020). The news outlet’s perceived political standpoint (as detailed in the methods section) followed closely in importance. On the other side of the coin, this research also explored how journalists and media organisations can promote trust in news. It found that “coverage depth” was the most important factor to Australian audiences and that a “neutral standpoint on contentious topics” was also important. In the context of aged care reportage, deep coverage may mean both seeking to access a diversity of sources, including perspectives of aged care residents, their families and carers, but it may also mean actively considering and redressing inherently biased and negative depictions of older people that are so commonplace as to be cliché (Thomson et al. 2022). If article length is used as a proxy for depth, news outlets should also consider how much to invest in day-turn stories, which tend to be shorter and to have fewer sources, compared to longer investigative pieces that tend to be more densely packed with sources.

Beyond Biased Sourcing Practices

Beyond shedding light on journalistic norms (the first two levels in Shoemaker and Reese’s Citation1991 model) and how resourcing can influence sourcing “richness”, this study also reveals important insights about how the ideological positioning of a media organisation, as informed by who owns it and its associated values, are made manifest in its journalists’ sourcing practices, thus drawing attention to the organisational and social-institutional levels of Shoemaker and Reese’s Citation1991 model.

Australia’s publicly owned news organisation, The ABC, for example, has an explicit commitment in its editorial policies to create “content that addresses a broad range of subjects from a diversity of perspectives reflecting a diversity of experiences, presented in a diversity of ways from a diversity of sources”. The Saturday Paper states in its editorial guidelines that it will present reporting with “with reasonable fairness and balance,” while The Guardian’s editorial code only states it has an obligation to “fairness,” with no mention of sourcing diversity or balance in its code. Lastly, The Australian’s editorial code of conduct encourages its reporters to “Try always to tell all sides of the story when reporting on disputes,” but also allows its staff freedom to “editorialise, campaign and take stances on issues” provided its journalists do not knowingly publish inaccurate or misleading information. It also states that “comment, conjecture and opinion are acceptable in reports to provide perspective on an issue, or explain the significance of an issue, or to allow readers to recognise what the publication’s standpoint is on the matter being reported”.

The considerable differences between these various codes of conduct are reflected in their respective journalists’ operating procedures. Despite many of these codes of conduct discussing fairness, balance, or striving for a plurality of perspectives, two national outlets in their reporting of ageing and aged care, for more than a year, completely neglected in their coverage aged care residents and aged care workers, who are the two groups with the most direct experience of this issue.

Accuracy, alone, then, is not enough to ward against bias in deciding how to source and frame the news. An awareness of the types of sources being used to inform one's reporting and a sensitivity to the power imbalances of different source types is also critical. It is not unthinkable that a heavy reliance on political sources (as was the case with the coverage by The Guardian Australia and The Australian) in a polarised political environment like Australia is more likely to influence an article’s valence and to perpetuate these polarised views in subsequent reporting that is published.

Beyond the Low-hanging Fruit

Journalists have an important responsibility to contribute to the sum of human knowledge as they write, revise, and analyse the “first draft of history” (Ritchie Citation1998). Reporters have an opportunity to do valuable public service journalism by sifting through datasets and policy reports and briefings that few else will. Finding meaning from raw data and making this more accessible to the public is important, but over-relying on secondary sources, especially with those that are widely available and don’t require as much interpretation or analysis, can also be problematic. As secondary source materials are often widely available, journalists must ensure they aren’t neglecting the opportunity (and reaping the benefits) from integrating more exclusive primary sources into their reporting. Likewise, using primary sources can enliven and can enrich reporting with concrete and vivid description what could otherwise be a dry and abstract numbers story. Indeed, when journalists engage in “armchair journalism”, they need to supplement this with in-the-field reporting that contributes to a more diverse and pluralistic marketplace of ideas within our media landscape. In this way, journalists can ensure they are not only amplifiers of existing narratives (such as witness testimony provided during the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety) but are also enablers of previously unheard voices to join in the local, regional, or national conversation on a topic.

Cognisant of the earlier-noted and widespread concern over ageism in media (Ng Citation2021; Officer, 2018), journalists should take care to ensure the valence of their reporting is not explicitly or implicitly ageist and also that they do not inappropriately privilege certain types of sources over others or reward certain identities with identifiability while depriving it for others. Likewise, they should ensure that their sourcing depth and diversity is consistent across news topics and that it doesn’t favour certain groups or topics. While it often takes more effort to develop stories that engage multiple sources, as content creators, journalists have an ethical obligation to be aware of their impact and reflect on whose voices they are privileging and amplifying—especially when the topic is as important as ageing and aged care.

Conclusion

This study’s primary contribution is providing a more holistic, nuanced, and multi-faceted understanding of journalistic sourcing practices related to a marginalised group, older people in aged care contexts, in particular. It expands beyond past studies that have examined the types of sources represented to also include the depth and density of sourcing practices, journalists’ reliance on primary versus secondary sources, and journalists’ use of anonymous and de-identified sources. It also examines preferred source types by outlet ownership. In doing so, it provides a compelling case for examining the proportion between day-turn and non-day-turn stories an outlet publishes and how this can empower or further marginalise an already socially weak and isolated group such as older people. It also provides valuable context from an on-the-ground journalist to ensure that the analysis and recommendations are not divorced from the realities of journalistic practice. In doing so, the study illuminates the challenges and opportunities related to covering an oft-forgotten segment of society and provides guidance for those wishing to create more representative journalism that enjoys higher levels of trust and credibility.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Articles from the ABC, The Guardian Australia, and The Australian were sourced from ProQuest and Factiva, which allowed multi-keyword searches. The articles from The Saturday Paper, sourced from PressReader, did not allow multi-keyword searches.

References

- Amundsen, D. 2022. “A Critical Gerontological Framing Analysis of Persistent Ageism in NZ Online News Media: Don't Call Us “Elderly”!” Journal of Aging Studies 61: 101009. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2022.101009.

- Atton, C., and E. Wickenden. 2005. “Sourcing Routines and Representation in Alternative Journalism: A Case Study Approach.” Journalism Studies 6 (3): 347–359. doi:10.1080/14616700500132008.

- Berkowitz, D. 2019. “Reporters and Their Sources.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, 165–179. New York: Routledge.

- Berkowitz, D., Y. Limor, and J. Singer. 2004. “A Cross-cultural Look at Serving the Public Interest: American and Israeli Journalists Consider Ethical Scenarios.” Journalism 5 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1177/146488490452001.

- Broersma, M., B. Den Herder, and B. Schohaus. 2013. “A Question of Power: The Changing Dynamics Between Journalists and Sources.” Journalism Practice 7 (4): 388–395. doi:10.1080/17512786.2013.802474.

- Connolly, A. 2019. “Aged Care Royal Commission has had a Third of the Coverage of Banks’ Bad Behaviour.” ABC Investigations. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-03/aged-care-royal-commissioncoverage-imbalance/11666490.

- Department of Health. 2020. 2020 Aged Care Workforce Census Report. Australian Government. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/09/2020-aged-care-workforce-census.pdf.

- Etikan, I., S. A. Musa, and R. S. Alkassim. 2016. “Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling.” American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 5 (1): 1–4. doi:10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11.

- Flew, T., U. Dulleck, S. Park, C. Fisher, and O. Isler. 2020. Trust and Mistrust in Australian News Media. BEST Centre. https://research.qut.edu.au/best/wp-content/uploads/sites/244/2020/03/Trust-and-Mistrust-in-News-Media.pdf.

- Gilbert, A. S. 2021. “Conceptualising Trust in Aged Care.” Ageing and Society 41 (10): 2356–2374. doi:10.1017/S0144686X20000318.

- Global Media Monitoring Project. 2020. Who Makes the News? https://whomakesthenews.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Australia.2020-GMMP-Country-Report-Australia.pdf.

- Harkin, J. M., J. Charlton, and M. Lindgren. 2018. “Older Drivers in the News: Killer Headlines v Raising Awareness.” Journal of the Australasian College of Road Safety 29 (4): 72–83. doi:10.3316/informit.146703087532395, (https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/INFORMIT.146703087532395?casa_token=xNXSOeOoWIwAAAAA%3AvvHzC2tlg3Ex6QIOLVMIzCqcYb2tL2GQAQIv1UK-En3rtsZ7zCd7VmczckqH-LhHcY5FxrnufdqrMw).

- Hickerson, A. A., P. Moy, and K. Dunsmore. 2011. “Revisiting Abu Ghraib: Journalists’ Sourcing and Framing Patterns.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 88 (4): 789–806. doi:10.1177/107769901108800407.

- Imran, M. A., and K. Bowd. 2022. “Consumers and Commodification: The Marketization of Aged Care in the Australian Press.” Australian Journalism Review 44 (1): 117–135. doi:10.1386/ajr_00091_7.

- Kleemans, M, G Schaap, and L Hermans. 2017. “Citizen sources in the news: Above and beyond the vox pop?.” Journalism 18 (4): 464–481.

- Köttl, H., V. C. Tatzer, and L. Ayalon. 2021. “COVID-19 and Everyday ICT Use: The Discursive Construction of Old Age in German Media.” The Gerontologist 62 (3): 413–424. doi:10.1093/geront/gnab126.

- Lecheler, S., and S. Kruikemeier. 2016. “Re-evaluating Journalistic Routines in a Digital Age: A Review of Research on the use of Online Sources.” New Media & Society 18 (1): 156–171. doi:10.1177/1461444815600412.

- Lichtenstein, B. 2021. “From “Coffin Dodger” to “Boomer Remover”: Outbreaks of Ageism in Three Countries with Divergent Approaches to Coronavirus Control.” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 76 (4): e206–e212. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbaa102.

- Manninen, V. J. 2017. “Sourcing Practices in Online Journalism: An Ethnographic Study of the Formation of Trust in and the use of Journalistic Sources.” Journal of Media Practice 18 (2-3): 212–228. doi:10.1080/14682753.2017.1375252.

- Manning, P. 2001. News and News Sources: A Critical Introduction. London: Sage Publications.

- Matthews, J. 2013. “News Narratives of Terrorism: Assessing Source Diversity and Source use in UK News Coverage of Alleged Islamist Plots.” Media, War & Conflict 6 (3): 295–310. doi:10.1177/1750635213505189.

- MEAA. 2022. “MEAA Journalist Code of Ethics.” Accessed on 18 July, 2022. https://www.meaa.org/meaa-media/code-of-ethics/.

- Morgan, T., J. Wiles, L. Williams, and M. Gott. 2021. “COVID-19 and the Portrayal of Older People in New Zealand News Media.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 51 (sup1): S127–S142. doi:10.1080/03036758.2021.1884098.

- Ng, R. 2021. “Societal Age Stereotypes in the U.S. and U.K. from a Media Database of 1.1 Billion Words.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (16): 8822. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168822.

- O'Neill, D., and C. O’Connor. 2008. “The Passive Journalist: How Sources Dominate Local News.” Journalism Practice 2 (3): 487–500. doi:10.1080/17512780802281248.

- Phillips, A. 2010. “Transparency and the New Ethics of Journalism.” Journalism Practice 4 (3): 373–382. doi:10.1080/17512781003642972.

- Reese, S. D. 2019. “Hierarchy of Influences.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by Tim P. Vos and Folker Hanusch, 1–5. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Ritchie, D. A. 1998. American Journalists. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Romano, Angela. 2021. Australia – National Report: Who Makes the News? Global Media Monitoring Project 2020. Who Makes the News? World Association for Christian Communication, Toronto, ON.

- Ross, K. 2007. “The Journalist, the Housewife, the Citizen and the Press: Women and Men as Sources in Local News Narratives.” Journalism 8 (4): 449–473. doi:10.1177/1464884907078659.

- Schapals, A. K., and Z. Harb. 2020. ““Everything Has Changed, and Nothing Has Changed in Journalism”: Revisiting Journalistic Sourcing Practices and Verification Techniques During the 2011 Egyptian Revolution and Beyond.” Digital Journalism 10 (7): 1219–1237. doi:10.1080/21670811.2020.1856702.

- Schudson, M., and T. Dokoupil. 2007, January/February. “Research Report: The Limits of Live.” Columbia Journalism Review 45 (5): 63. https://archives.cjr.org/the_research_report/the_limits_of_live_1.php.

- Shoemaker, P. J., and S. D. Reese. 1991. Mediating the Message: Theories of Influences on Mass Media Content. New York: Longman.

- Tandoc, E. C. Jr., and A. Duffy. 2019. “Routines in Journalism.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by Jon Nussbaum . Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.870.

- Tenenboim-Weinblatt, K., and C. Baden. 2018. “Journalistic Transformation: How Source Texts are Turned into News Stories.” Journalism 19 (4): 481–499. doi:10.1177/1464884916667873.

- Thomson, T. J., S. Johnstone, J. Seevinck, E. Miller, and S. Holland-Batt. 2022b. “It’s not Enough to Be Seen: Exploring how Journalists Show Aged Care in Australia from 2018–2021.” Communication Research and Practice, 261–277. doi:10.1080/22041451.2022.2137237.

- Thomson, T. J., E. Miller, S. Holland-Batt, J. Seevinck, and S. Regi. 2022a. “Visibility and Invisibility in the Aged Care Sector: Visual Representation in Australian News from 2018–2021.” Media International Australia. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X221094374.

- Torben-Nielsen, K., and S. Russ-Mohl. 2012. “Old is not Sexy. How Media Do (Not) Report about Older People, and How Older Swiss Journalists Started Their Own Newspapers Online.” Romanian Journal of Journalism & Communication 7 (1): 59–68. https://ideas.repec.org/a/foj/journl/y2012i1p59-68.html

- Tsfati, Y, and J. N. Cappella. 2003. “Do people watch what they do not trust? Exploring the association between news media skepticism and exposure.” Communication research 30 (5): 504–529.

- Van Leuven, S., S. Kruikemeier, S. Lecheler, and L. Hermans. 2018. “Online and Newsworthy: Have Online Sources Changed Journalism?” Digital Journalism 6 (7): 798–806. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1498747.

- Waters, R., N. Tindall, and T. Morton. 2010. “Media Catching and the Journalist–Public Relations Practitioner Relationship: How Social Media are Changing the Practice of Media Relations.” Journal of Public Relations Research 22 (3): 241–264. doi:10.1080/10627261003799202.

- Wheatley, D. 2020. “Victims and Voices: Journalistic Sourcing Practices and the Use of Private Citizens in Online Healthcare-System News.” Journalism Studies 21 (8): 1017–1036. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2020.1727355.

- World Health Organization. 2021. Global report on ageism. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/demographic-change-and-healthy-ageing/combatting-ageism/global-report-on-ageism.