ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the development of the Social Enterprise (SE) in Thailand. Emerging from the non-profit sector in the 1970s, Thailand is now experiencing the development of new state-private policy interventions to stimulate development of SE. We combine the work of Kerlin on the socio-economic environment with the theories of market creation from economic sociology. We pinpoint for the first time the key institutions, networks, cognitive framings and policy initiatives of SE emergence and development in Thailand. In addition, we identify a new country type Social Enterprise Semi Strategic Diverse model form, we term an Authoritarian State-Corporate model.

Introduction

The phenomenon of social enterprise has attracted the attention of policy makers and practitioners around the world (Wilson & Post, Citation2013) and the associated rise in scholarly interest is reflected in the growing tally of publications in the academic press about SE as a distinct category of organizations and the activity of social entrepreneurship (Cukier et al., Citation2011; Lepoutre et al., Citation2013; Lumpkin et al., Citation2013). However, there has been a limited number of academic publications specifically on understanding the emergence of social enterprise (SE) in Thailand (Sengupta & Sahay, Citation2017).

A SE is an organization that trades, not for private gain, but to generate positive social and environmental value (Santos, Citation2012). The two defining characteristics of SE: the adoption of some form of commercial activity to generate revenue and the pursuit of social goals (Laville & Nyssens, Citation2001; Mair & Marti, Citation2006; Peattie & Morley, Citation2008; Peredo & McLean, Citation2006). Thus SEs differ from organizations in the private sector that seek to maximize profit for personal gain by prioritizing social change above private wealth creation: typical social objectives include reducing poverty, inequality, homelessness, carbon emissions, unemployment etc. (Dart, Citation2004; Murphy & Coombes, Citation2009). Hence, SEs are associated with pro-social motivations of wealth giving, cooperation and community development (Lumpkin et al., Citation2013). Lien Centre for Social Innovation (Citation2014) argue that Thailand and other Southeast Asia countries display large scale persistent and emerging social problems (growing wealth gap) requiring solutions from social enterprises. This is supported by Kerlin (Citation2010), who argues that these social challenges are not adequately addressed by government welfare programmes but she does point to the recent burgeoning interest in SE in the Southeast Asia and Eastern Asia regions (Chandra & Wong, Citation2016; Jeong, Citation2017).

Kerlin (Citation2010) using social origins theory to outline distinct regional differences in how social enterprises have emerged proposes in Southeast Asia the four key socioeconomic factors that influence the nature of social enterprise model emergence namely, market performance, international aid, state capability and civil society are all weak. According to Kerlin (Citation2010), this results in a mixed social enterprise model motivated by the innovative efforts of isolated social enterprises who are working without established networks and stable sources of support. We combine Kerlin’s work (Citation2010, Citation2017) with both sector creation theory from economic sociology (Beckert, Citation2010; Berndt & Boeckler, Citation2009; Fligstein & Dauter, Citation2007) to provide a rich picture of SE emergence and development in Thailand. This paper demonstrates that the emergence of social enterprise in Thailand is complex with recent significant intervention from both the state and the private sector in partnership creating a new country type SE Semi Strategic Diverse model form we term an Authoritarian State-Corporate model. This has led to concerns around co-optation of the SE sector in Thailand.

In this paper, we unpack how the social enterprise sector has emerged in Thailand. The paper makes a novel contribution by combining, social origins theory (Kerlin, Citation2010) and her Macro-Institutional Social Enterprise Framework (Kerlin, Citation2017), with work in economic sociology (Beckert, Citation2010; Fligstein & Dauter, Citation2007). We identity the unique factors leading to the emergence, second wave development and the recent tensions between the founding SE members and the public-private partnership (Pracharath) initiated by the current Thailand government.

The paper is laid out as follows. To begin we review the literature on social enterprise and its creation and emergence. This is followed by the explanation of our qualitative methodology and research context. In the findings we present for the first time empirical data to illustrate the key institutions, networks and cognitive framings of SE in Thailand, the timelines of key Thailand government social enterprise development policies coupled with concerns around the growing influence of the state and private sector in partnership on the co-optation of the SE sector. In the conclusions we explain how the analysis contributes to the social enterprise literature by identifying a new SE country model we term an Authoritarian State-Corporate model.

Literature review

Social enterprise

The prioritization of goals other than revenue growth and profitability distinguishes social enterprise hybrids from organizations in the private sector (Lumpkin et al., Citation2013; Mair & Marti, Citation2006). Social goals are broadly construed to include serving the needs of the disadvantaged (Defourny & Nyssens, Citation2006), unemployed (Pache & Santos, Citation2013), homeless (Teasdale, Citation2012) and smallholder farmers (Mason & Doherty, Citation2016). Environmental objectives include responding to climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution (Vickers & Lyon, Citation2013). Hybrids are also recognized for their willingness to collaborate with each other and across sectors (Gillett et al., Citation2018).

To achieve sustainable outcomes in all three domains, social enterprises adopt business models that encompass commercial trading as well as creating social and environmental impacts. This is achieved by blending practices from organizations in the private, public and non-profit sectors (Doherty et al., Citation2014; Maak & Stoetter, Citation2012). Although deviation from the institutional conventions anchored in each sector of the economy might appear to be a risk-laden strategy, the outcome has been the development of an increasing global population of social enterprise hybrids (Mair & Marti, Citation2006).

Social enterprise hybrids are ‘not aligned with the idealized categorical characteristics’ of the private, public or non-profit sectors (Doherty et al., Citation2014, p. 3) and by pursuing the achievement of commercial, social and environmental objectives are thus a classic hybrid organizational form (Battilana & Lee, Citation2014; Billis, Citation2010; Dees & Elias, Citation1998; Defourny & Nyssens, Citation2006). To date, social enterprise research has focused on understanding how tensions resulting from the dual mission are resolved (Battilana & Lee, Citation2014; Doherty et al., Citation2014; Smith & Tracey, Citation2016; Wry & Zhao, Citation2018). There has been an increasing interest in looking at how SE has emerged in different contexts (Defourny & Nyssens, Citation2017; Kerlin, Citation2010, Citation2017; Fernández-Laviada et al., Citation2020). Few studies have looked at its emergence and sector creation in newly industrialized contexts such as Thailand (Chandra & Wong, Citation2016; Jeong, Citation2017).

Creation and emergence of social enterprise

To unpack the development of social enterprise in Thailand we take a novel approach by drawing on interdisciplinary theory from economic geography and economic sociology (Beckert, Citation2010; Berndt & Boeckler, Citation2009; Fligstein & Dauter, Citation2007) combined with both Kerlin’s (Citation2010) social origins approach and her work on the macro-institutional social enterprise framework (MISE). This unique conceptual approach enables the authors to provide an in-depth and holistic view of SE sector development in Thailand. Kerlin (Citation2010) explains in Southeast Asia post the 1990s financial crisis there has been a growing interest in SE. Kerlin (Citation2010) argues this has been framed in terms of SE contribution to sustainable development and employment. Kerlin argues the mixed social enterprise model of Southeast Asia is weak on all four socioeconomic factors (see above) and therefore SEs in the region is at an emerging stage motivated by the innovative efforts of isolated social entrepreneurs, who are working without established networks or sources of support. Kerlin (Citation2010) argues that in this emerging stage social enterprises draw resources from wherever they can. Kerlin (Citation2010) in her comparative overview of seven world regions proposes that Southeast Asia is characterized by thus far limited discussions on a SE legal framework, focus and a strategic development base involving international aid, the market and the state.

Kerlin (Citation2017) in her work on the MISE maps out the role of institutions (both formal and informal) in shaping the development of SE in different country contexts. Scott (Citation2008, p. 49) defines institutions as both formal and informal structures that have achieved a certain level of resilience and are comprised of regulative, informative and cultural cognitive elements that combined with associated activities and resources provide stability and meaning to social life. Scott (Citation2008) explains that formal institutions are structures of codified and explicit rules and informal institutions are shared meanings and collective understandings in a society. Kerlin (Citation2017) explains that institutions (government, economic or civil society) exist at three societal levels including, macro (national or international level), meso (regional, municipal or network level) and micro (local level). The MISE framework which is grounded in historical institutionalism (Thelen, Citation1999) also emphasizes the importance of underlying power relationships, both in how power is involved in developing institutions and how the created institutions then structure power. Rueschemeyer (Citation2009) outlines how institutions at the meso and micro levels e.g., SEs are highly structured by state institutions and their policies. Kerlin (Citation2017) goes onto identify a series of seven SE country typologies including, Autonomous Diverse (civil society e.g., USA), Dependent Focused (welfare partnership e.g., Italy), Emmeshed Focused (Social Democratic e.g., Sweden), Semi-Strategic Focused where the government only supports certain types of SE via legal forms etc. (Statist e.g., China), Strategic Diverse where the state is supporting mixed SE model (Statist e.g., South Korea), Autonomous Mutualism (Deferred Democracy e.g., Argentina) and Sustainable Subsistence (Traditional e.g., Zambia). Kerlin (Citation2017) also pointed out these typologies are dynamic and countries can transition between typologies.

In response to the limited work on SE in Eastern Asia, Jeong (Citation2017) investigated studying SE Development in South Korea. Jeong (Citation2017) highlights that one of the most distinctive features in the East Asian Model is the pro-active involvement of the state. The background to this is the notion in Eastern Asia of the Development State, which is state led economic growth in cooperation with business. South Korea has demonstrated a strategic diverse development statist model of SE with a focus on both civil society and business. However, its emphasis has been on the non-profit sector to lead development of SE sector to provide welfare provision. South Korea is considered to be democratized and developed.

There are criticisms of the formal and informal institutional approach as to reductionist (Beckert, Citation2010; Fligstein & Dauter, Citation2007). Those studying the sociology of markets and fields i.e. new institutionalism, criticize the segmentation of approaches and argue there is more to be gained from bringing together the three types of social structures relevant for the explanation of economic outcomes i.e. the main schools of thought namely; institutions (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991), networks (Granovetter, Citation1985) and performativity (Callon, Citation1998). According to DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1991), institutionalism focuses on market rules, power and norms. In their work on the theory of new institutional organization, a network is usually regarded as part of institution and is an important aspect that contributes to institutional homogenization (DiMaggio, Citation1991).The institutions form an environment that surrounds an organization called an ‘organizational field’, and organizations in the same organizational field (i.e. institutional environment) tend to behave in a similar way. This is achieved by mechanisms such as mimicry and imitation (Beckert, Citation2010). Network theorists focus more on the relational ties between actors and the role that social networks play (Aspers & Beckert, Citation2011; Granovetter, Citation1985). Performativity is the introduction of a representation of the world as well as a shared belief about the behaviours to adapt (Callon, Citation2007). Beckert (Citation2010) argues these cognitive frames, also form a social structure in their own right. Social norms, as well as cognitive ‘how-to’ rules, are part of a socially inscribed meaning structure operating in a market field through which firms and other field actors assess situations and define their responses. According to Callon (Citation2007), this can spur the proliferation of new social identities.

To avoid the segmentation of these approaches Beckert (Citation2010, p. 612) therefore proposes that market sectors are composed of three distinct, yet interrelated dynamic social components: social networks (which establish and support), formal institutions (which organize and govern the activities) and cognitive frames (that provide structures of values and meanings in which trade and organizations are embedded). The simultaneous inclusion of these three components makes it possible to address how these social structures impact each other. One of the key characteristics of this conceptualization is that whilst other literatures have treated the individual components of sector creation separately, these are irreducible and mutually interrelated through dynamic interactions: with changes in one component often influencing reconfiguration in others (Beckert, Citation2010; Berndt & Boeckler, Citation2011). For instance, institutions can force changes in social networks by changing institutional rules and network positions can be used to influence institutions (Beckert, Citation2010). Not treating social networks as a distinct social force from institutions could avoid detecting two important dynamics; first how they can impact on the power of formal institutions who are interested in preserving existing rules and second how network connections are important in new institutional building (Djelic, Citation2004). Hence, in this research unpacking the emergence and development of the SE sector in Thailand we conceptually separate the concept of the network from institution. Furthermore, Berndt and Boeckler (Citation2011) argue that morality is also important in sector creation. This approach from economic sociology has been used to explain the emergence of other social sectors such as fair trade in different national contexts (Doherty et al., Citation2015).

In this research we combine these different theoretical perspectives (new and old institutionalism) from economic sociology (Beckert, Citation2010; Fligstein & Dauter, Citation2007) and Kerlin’s (Citation2017) MISE framework underpinned by historical institutionalism to provide an holistic approach to explaining both the emergence of SE in Thailand and the recent state and private sector interest in this sector.

Methodology

This study emerged from the on-going professional and academic interest of both co-authors in social enterprise, who have combined 32-years of experience of both working and researching social enterprise. It became clear from previous research and training projects working in partnership with both the British Council and Thammasat University that a social enterprise sector is emerging in Thailand. However, we do not understand the factors leading to both its emergence and recent state and private interest. Hence, the methods of enquiry are predominantly qualitative in which inductive logic is used to obtain insights (Garud et al., Citation2002; Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Use of qualitative procedures is appropriate as our aim is to obtain rich contextual understanding and promote exploratory insight of a complex emerging setting (Gephardt, Citation2004).

Data collection

We followed Ruef and Scott (Citation1998) in defining our field geographically, collecting our data within the Thailand SE sector a newly industrialized country. The qualitative methodology included three phases – first round of focus group, semi-structured interviews, and second round of focus group

Focus group is often used in pilot studies to develop a list of questions for interviews (Collis & Hussey, Citation2003). It provides rich data and insights, which could be less accessible without the interactions found in a group (Morgan, Citation1988). Hence, this paper applied a focus group in the initial stage of the research as the pilot study to explore how the SE sector emerged and developed in Thailand. Then, semi-structured interviews were applied with SEs in Thailand to acquire in-depth information regarding SE emergence and development. Finally, the second round of focus group was conducted to verify the findings from the research. This allows the triangulation of data collection sources to ensure the quality and validity of the research.

First, a one day focus group took place with thirty-one participants from the SE sector in Thailand. This workshop involved seventeen social enterprise founders and CEOs, four intermediary organizations, four private sector organizations working with SE, two charities and four academics. The SEs represented a range of sectors including; organic agriculture, social care (e.g., disability support), media, e-commerce, publishing, textiles and fashion. In addition, there was a good representation of both start-up and established SEs. The focus group involved two-sets of group discussions, firstly around the key factors impacting on the emergence of social enterprise in Thailand and the key challenges.

Second phase, we conducted twenty six in-depth semi structured interviews with senior key informants in SEs (managers and founders), intermediaries, government departments, NGOs, International Development Agencies within Thailand (see ). These individuals represented key stakeholders in the social enterprise sector and the interviews were conducted in person and were recorded on a digital audio device and transcribed. All interviews took place between May 2017 – October 2018. These interviews focused on some of the emerging themes from the initial workshop focused on SE sector development and associated key factors. Final phase included a second focus group with twenty-five participants (fourteen SE CEOs/founders, three corporate representatives, three academics, two policy representatives, five intermediary organizations) to test out the key themes emerging from the first two phases. Running through all these 3 phases was the collection of secondary documentation. Our aim here was to triangulate key emerging themes. This final focus group involved both feeding back and testing the key themes emerging from the twenty-seven semi-structured.

Table 1. List of social enterprise informants in Thailand

Data analysis

Guided by the principles of grounded theory, we set aside existing categories of SE country development and treated them as unknown (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). Accordingly, the workshop reports and interviews transcripts were analysed using inductive qualitative techniques (Paroutis & Heracleous, Citation2013) that allowed findings to emerge from the data. Both authors analysed the interview transcripts independently. This was first carried out manually to stay close to the empirical data during coding. We then used the Nvivo software package (Bazeley & Jackson, Citation2013) to scrutinize the veracity of our coding and theorizing.

To begin, the authors independently open coded both the focus group data and interview transcripts as soon as each was transcribed. The aims were to highlight all references related to SE country development and inform the questions in the subsequent interviews. During open coding specific attention was given to the development of SE in Thailand. After all the transcripts from interviews and focus group had been analysed, the extracts were scrutinized and grouped into empirical themes. Then, after further interrogation of the empirical data and in consultation with the social enterprise development literature, were condensed to five empirical themes (see findings and discussion section). Then working closely with the SE development literature, we abstracted a new SE country development model. In the findings and discussion section we present our empirical themes and present illustrative quotes from our interviews.

The analysis of the interview and focus group data was also combined with our historical overview/literature review derived from secondary and grey literature. The approach to the data analysis was inductive and iterative, as whilst we were aware of some of the literature (academic, historical and grey) surrounding social enterprise we did not set out to test any predetermined theories but instead used the data gathered to develop our theoretical understanding of how social enterprise development took place in Thailand. The key themes from the data are discussed in the findings and discussion section.

Research context

Using some of the characteristics included in Kerlin’s typology of SE country models Thailand is a collectivist in culture (Hofstede Insights, Citation2020), is 60th in the world for government effectiveness (World Bank, Citation2020), and according to the World Economic Forum is 40th in the world in terms of its economic competitiveness (World Economic Forum, Citation2018). The financial crisis of 1997 brought in new governance measures for business with the Thai Securities Exchange and the Stock Exchange Thailand (SET) establishing a Good Governance Subcommittee. Since 2006, Thailand has experienced significant disagreements over democracy with two coups, two constitutions, three ‘judicial coups’, four general elections, five cycles of both pro- and anti-democratic urban occupations, seven different prime ministers and two periods of authoritarian rule, one of which is ongoing (Elinoff, Citation2019). Central to this volatility and the recent turnaway from democracy are interlocking disagreements about the meaning of citizenship, the value of democracy, the rule of law and the question of sovereignty (Elinoff, Citation2014).

Findings and discussion – Social enterprise development in Thailand

Early stage development of social enterprise in Thailand

The first key theme identified was the mixed model emergence of SE in Thailand from the 1970s to the 1990s. Our research shows the model of using business activities to generate social impact existed in Thailand before the term ‘social enterprise’ was popularized. The origins displayed different SE mixed forms. First, the self-sufficiency economic philosophy of the late King Rama 9 and the late Mother of the King Rama 9 led to the set-up of community ventures in the Northern region to create alternative income sources such as coffee, macadamia nuts, textiles for communities living in poverty. This royal project called the Mae Fah Luang Foundation (MFLF), founded in 1972 provides jobs and capability development for ethnic groups in the upland communities of Doi Tung as well as generating income to finance community development activities.

“The Mother of the King said, don’t let the people buy out of pity, let them buy because the product is good and the people are building livelihoods”. (Informant, Founding Social Enterprise)

The non-profit Population and Community Development Association (PDA) founded in 1974 by Mechai Viravaidya set-up a popular restaurant in the heart of Bangkok called Cabbages and Condoms and the earned income from the restaurant is then invested in PDA programmes such as sexual health education and education for disadvantaged young people (Bamboo Schools).

In addition, a number of cooperative social enterprises emerged such as the Lemon Farm organic wholefood food retailer in Bangkok with around fifteen retail stores set-up in 1999. Lemon Farm emerged from the organic agriculture movement and works closely with smallholder organic cooperatives, who also have representatives that sit on the Lemon Farm board. The initial Lemon Farm stores were in fact incubated in petrol stations by the gasoline company called Bangchak, which had a policy of supporting cooperatives. In 1999, Dairy Home, an organic dairy producer, was set up to manufacture dairy fresh milk, butter, yoghurt, and other dairy products in Thai market. Dairy Home has been working closely with dairy farmers to transform their farms into organic ones and pay them a premium price.

However, until recently the concept of SE remained unknown to development practitioners and the public. More recently, there has been a growing demand in Thailand for innovative developmental solutions due to rising inequality, ongoing political instability and increasingly complex social and environmental problems compounded by the financial crisis in the 1990s in Southeast Asia. Secondly, some foundations, multinational companies and international NGOs have reduced significantly their financial and technical support to local development agencies in the past decade. This has forced the existing social sector organizations and emerging new players to look for more self-sustainable enterprise models to support their work i.e. SE.

International impact

The second theme identified in our data was the macro-institutional impact from the international political environment, particularly from the UK Government. Encouraged by the international success of SE, the Thai government set up the National Social Enterprise Committee in 2009 to increase awareness of SE to the public and develop supporting infrastructures that would enable the SE movement to grow in Thailand.

The Democratic Government at the time led by the Prime Minister Abhisit, who had been born and educated in the UK, began to look at different measures that could grow the economy but deliver social inclusion. One of our informants explains the role of the British Council (BC):

“The British Council was very instrumental in the development of social

enterprise in Thailand, because they organised policy trips to the UK for Abhisit’s policy team”. (Informant, Social Enterprise Agency).

This is supported by a senior informant from the British Council in Bangkok who explains:

“There was keen interest in SE in the Thai government and a real openness to learn from the UK. So I coordinated policy maker trips to the UK. I was close to the Advisor to the Prime Minister at the time on such matters who then was influential in setting up the Thailand Social Enterprise Office (TSEO) in the Thai government. I believed that BC was well positioned to create meaningful change at the highest level, which would lead to more SEs being set up and more collaboration with the UK. I was also motivated by the opportunity to bring in UK universities and social entrepreneurs so we worked with Srinakarinwirot University in Bangkok, which had a very pro-active President in terms of SE advancement, and we brought over academics from UK universities to take part in meetings and SE teaching. In terms of raising awareness of SE in Thailand, we sent Channel 3 – a Thai TV channel – with one delegation to the UK to cover the trip and it appeared as a series on prime time TV here”. (Informant, British Council, Thailand).

To support the development of the Thai SE sector ten universities in Thailand participate in the knowledge development and incubation programme networking activities supported by TSEO and the British Council. This has led to a growing interest from Thai academic institutions to play a more active role in the sector. It is clear that international influence is an institutional factor in SE development in Thailand. The role played by the BC draws similarities to the pivotal role they played in the development of SE in China described as a diffusion of innovation (Cui & Kerlin, Citation2017). Rogers (Citation1995, p. 5) defines diffusion of innovation as ‘the process by which innovation is communicated through certain channels over time amongst member of a social system’.

National government involvement and legal frameworks

A third theme was the growing influence of the National political context in Thailand on the SE sector. After the set-up of the National Social Enterprise Committee in 2009 (mentioned above) the Thailand government developed a range of SE policies (see for timeline of key social enterprise development policies). The five-year National Social Enterprise Master plan (2010–2014) was developed by the Committee in 2010 which led to the establishment of the Thai Social Enterprise Office (TSEO) in 2010 (see below) as a government agency to support SEs. An informant who was involved in setting-up the TSEO explains:

“Thai Social Enterprise Office was set-up to work on multiple initiatives including, in the universities again with the British Council to work on multiple activities and of course at the policy level. We also focused on incubating a few specific enterprises and growing the social investment structure to support them. Our focus was mostly on social enterprises that are new enterprises. Mostly coming from the younger generation”. (Informant, former TSEO staff member).

Table 2. Timeline of social development policies in Thailand (authors own)

TSEO then worked to encourage policy support and buy-in from relevant government agencies and politicians leading to the development of a Social Enterprise Promotion Act. The draft of the SE Promotions Act included, tax incentives for investors (investment and procurement), social taxation for SEs, a SE start-up grant program, soft loans for SEs, social procurement and SE certification. Again, this shows the macro-institutional influence of National government in Thailand.

Since 2013, the TSEO has set up an online self-registration system for SEs. Both TSEO and the National Social Enterprise Committee established specific criteria in 2014 to endorse registered organizations as SEs. The five criteria consist of (1) clear social objective, (2) financial sustainability, (3) fairness to society and the environment, (4) reinvest to achieve social goal, and (5) good governance. Regarding the first criteria, the registered SE needs to have one of the following social objectives – (1) employing the disadvantaged, (2) promoting better society or environment through their core business activities, (3) owned or governed by the disadvantaged, or (4) allocate most of their profit to their social cause or reinvest in their SE. Regarding financial sustainability, the SE has to have over half of their revenue from trading activities and cannot allocate more than 30% on dividend. Finally, the SE has to maintain good governance with a minimum requirement to; register as an organization (could be in the form of foundation, association, company, etc.), submit an annual report to their respective regulatory body and make their information publicly available.

From 2010, a second wave of SE development took place of new start-up integrated social business type model particularly, in sustainable tourism, agriculture and working with the disabled. For example, Local Alike in tourism has a mission of ‘good travelling, social impact’ and designs tourist experiences with local Thai communities to appeal to a range of travelling types. The Cube, run by NISE Corporation, based in Bangkok makes a range of products (baking and stationary) by people with disability. Those visually impaired are able to bind notebooks often better than most people due to their enhanced physical senses. Autistic individuals can perform repetitive such as the kneading of bread dough very effectively. A number of these new SEs are also adept at trading and selling their goods to the private sector e.g., Muser coffee providing the on-board coffee for airline Air Asia.

Networks

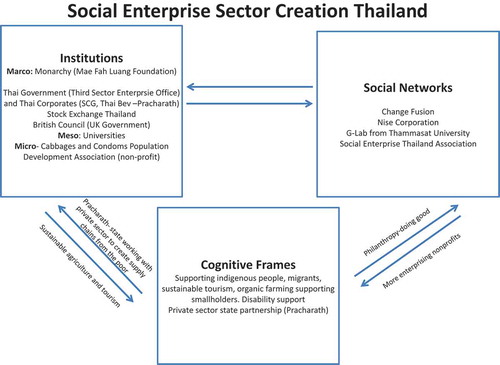

The fourth key theme emerging from the research is the importance of social networks in SE development in Thailand. Some of the key networks identified in the data include; Change Fusion, Nise Corporation, Ashoka and more recently the Social Enterprise Thailand Association (see ). One of our informants explains:

“A key progressive non-profit organisation network in SE in Thailand is Change Fusion. It was set-up by the ex-Deputy Prime Minister who had been working with civil society and he was very progressive. The second sector is the worker integration network involving the disabled called Nise Corporation who have set-up a network of SEs working with the disabled in Bangkok”. (Informant, Government Office)

First, ChangeFusion Group which is a non-profit organization which has brought together a network of social venture, capital investment, crowdfunding and incubating social enterprises into their network. The network pools resources and has created a network of experts to serve each other. ChangeFusion Group has been able to raise funds for social good through its partners e.g., crowdfunding for COVID-19 to help provide surgical masks and support for the vulnerable. Second, Nise Corporation, which is an intermediary body, was set up initially due to the launch of PWD (People with Disability) Act in 2007 to build PWD capability and empower the disabled by developing their skills and opportunities. Nise Corporation, is a social network company, with the aim of linking PWD with private sector organizations to support compliance with the PWD 2007 Act (see ). In addition, the company also serves as a social impact training organization. The importance of networks identified here appears to support the work on the importance of relational ties (Granovetter, Citation1985). This also demonstrates the impact and interplay of formal institution rule setting and the impact on social networks.

Corporate and state interest in social enterprise

A fifth key theme identified in the data is the strong influence of the collaboration between the state and big business. In 2012, the Stock Exchange of Thailand launched incentives for companies to shift their CSR approach towards SE (see below). Furthermore, the public-private partnership (Pracharath) initiated by the current authoritarian government (Elinoff, Citation2019) launched in 2016 encourages corporations to create SEs. Thai Beverage Group CEO announced in April 2016 the establishment of Pracharath Raksamakkee, an umbrella organization to set-up SEs nationwide. The model aims to strengthen Thailand’s economy at the local level empowering communities and enterprises. To do so the Government envisions public-private- civil society nexus acting in the interests of sustainable development through the execution of 4 major strategies; good governance, innovation and productivity, developing products and services from rural communities.

Pracharath or ‘people state policy’ works across 77 provinces in Thailand with a national board and provincial boards. There is also financial funding in terms of a credit guarantee scheme providing 100 m baht to encourage banks to lend to SEs. Critics accuse this as a way of pouring money into rural communities to win votes and a re-branding of Pracha Niyom or populist policies. Registered corporate SEs will be able to seek promotional privileges and income tax exemption. For private sector organizations who invest in registered SE, their investment or donation can be regarded as expenses and help with the corporate tax deduction as long as the total annual expenses do not exceed 2% of the annual net profit. These key political developments are outlined in below, which shows the increasing influence of the market and state working together in the Thailand SE sector.

In response, the original SE founders e.g., MFLF and Cabbages and Condoms set-up in 2019 the Social Enterprise Thailand Association (see ). An informant, who is a member of the association explains:

“The government and TSEO have not really addressed the right issues for mission led SEs in Thailand. The public-private partnership (Pracharath) really prioritises private sector interests. We have set-up the association to provide much needed support to SEs. We have decided to focus our efforts on mentoring young social entrepreneurs, empowering them, and linking them up with our existing networks. The aim is to be a true incubator for genuine SE in Thailand”. (Informant, member of Social Enterprise Thailand Association)

In addition, the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) has been actively promoting SE by hosting events, seminars and discussions to educate business leaders and CSR professionals on the potential of SE to drive social change. SET are encouraging listed companies to integrate social investment with their business operations and activities. In 2015, SET established the ‘Social Enterprise Investment Awards’ for listed companies who strategically contribute their financial and in-kind support to SEs. In April 2016, SET has launched the ‘SET for Future’ portal as an online database for companies who are looking for an SE partner. Furthermore, the G-Lab, Social Innovation Lab at the School of Global Studies at Thammasat University, supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, has developed a corporate pro-bono initiative to support SE capacity building. Secondly, Thai Health Promotion Foundation has granted Ashoka Thailand to manage a capacity building program for their grantees. Intermediaries such as Ashoka Thailand and Change Ventures integrate capacity-building support as part of their venture investment.

Due to new regulatory mechanisms in Thailand, corporations are increasingly viewing SE as a strategic opportunity. This is leading to a both a growing interest and increasing awareness of SE which is positive. However, on a cautionary note we found in our interviews and focus groups, some reports of Thai private sector corporations using the SE Promotion bill to their financial advantage. An informant explains:

“One major food company are holding discussions to convert their loss making subsidiaries to SE to avoid paying corporate tax.” (Informant, NGO representative)

Another informant from one of the SE agencies reports:

“One of the large Thai conglomerates who owns a large coffee chain is converting a portion of its coffee shops to SE to gain tax incentives”. (Informant, Social Enterprise Agency).

Doherty et al. (Citation2013) warn that uncritical engagement with mainstream business can risk co-optation, dilution and reputational damage. There appears to be genuine concerns about the potential for corporate co-optation of social enterprise in Thailand. Another informant goes further:

“I think the Government and the large corporates have mistreated the concept of social enterprise. I am not sure whether you have the same feeling or not, but that’s how I feel. If SE is taking over by large business then social enterprise will be just another term”. (Informant, Social Entrepreneur)

Co-optation is a phenomenon associated with the co-optation of leaders of political movements to conform to established frameworks and procedures to create social change, only partially achieving their goals (Jaffee, Citation2010). In effect, co-optation could lead to mainstream partners absorbing the more convenient elements of social enterprise at the expense of its more transformative impact.

Jaffee and Howard (Citation2010) focuses on the subversion of policy making to explain co-optation. However, in organizational management terms this could be associated with Mintzberg’s (Citation1989) concept of ‘assimilation’, where in reaching out with an ideology to divergent social groups, the original organizations’ ideal becomes compromised. Jaffee (Citation2010) uses of the term regulatory capture, where regulatory bodies are influenced by certain actors to make regulatory decisions in the commercial interest of those actors rather than the overall social good. Lawrence and Suddaby (Citation2006) also explain if organizations are able to associate the new with the old in some way that eases adoption. One way in which this is done is through mimicry, part of the success of mimicry in creating new institutional structures so that the juxtaposition of the old and new templates can simultaneously make the new structure understandable and accessible.

In summary, we have used our rich data to adapt the sector creation model of Beckert (Citation2010) to show the key institutions, networks and cognitive framings responsible for the creation of the SE sector in Thailand (see ). Combining this with the social origins and MISE theory approach of Kerlin (Citation2010, Citation2017) we can see the important role played by a series of institutions from civil society (meso and micro institutional levels), the international political environment e.g., UK Government (macro level), the state and the market (macro level) and a series of social networks e.g., Change Fusion, Nise Corporation. We can also see the interplay between formal institutions and social networks with the importance of new rule setting (see ) and the impact on network creation e.g., Nise Corporation and the positioning of networks such as ChangeFusion in attempting to influence the SE Promotion draft bill. Unique to Thailand we can see the important role played by the Monarchy in the early SE development, the influence of the state and private sector in combination (Pracharath) and the role played by the British Council to facilitate policy interaction between the UK and Thailand via a process of diffusion.

A unique element to SE development in Thailand has been the collaboration between both the state and the private sector demonstrated by the development of legal frameworks to incentivize the private sector to go beyond CSR and set-up SEs. This is in contrast to South Korea, where a partnership with the non-profit sector was preferred. The current authoritarian government in Thailand has preferred a model prioritizing the role of business called Pracharath. Hence, using Kerlin’s MISE framework, Thailand demonstrates an example of an Authoritarian State-Corporate model, which the authors identify as a new category of the Strategic Diverse and semi-strategic model in Kerlin’s (Citation2017) country typology.

Conclusions

The authors have taken a systematic approach to unpack the dynamic emergence and development of social enterprise in Thailand. This research has identified five key themes. First, the early emergence (1970s-1990s) driven by a mixed SE model involving; the monarchy in the form of MFLLF working to empower Northern Thai ethnic groups, PDA from the non-profit sector setting up Cabbages and Condoms and Lemon Farm, a cooperative from the organic movement. Second, from 2009 the growing macro-institutional influence from the UK Government on SE development in Thailand via its agency the British Council. This finding shows similarities with the role played by the British Council in the development of social enterprise in China, through a process of diffusion of innovation (Cui & Kerlin, Citation2017). Third theme identified is the growing influence of the Thailand government in developing new policies and legal frameworks for SE (see ). Fourth theme, is the emergence of key networks such as ChangeFusion to develop shared resources and expertise for SE. Fifth, is the recent growing interest from both the state and private sector in the form of the public-private partnership (Pracharath) initiated by the current authoritarian government in 2016. Pracharath along with the new Social Enterprise Promotion Bill (2018) encourages corporations to create SEs and appears to be incentivized by tax relief for corporations. This is leading to fears of co-optation of SE in Thailand and its associated reputational risk. In response, the SE founders have set-up the Social Enterprise Thailand Association and we appear to be entering a contested phase over the future of SE in Thailand. The founders view the association as a mechanism to maintain the more transformative aspects of SE and maintain the sectors heterogeneity. These dynamics taking in the Thailand SE sector illustrate the importance of viewing this interplay through a conceptualization that recognizes the irreducibility of social structures.

By combining three different theoretical approaches we have been able to unpack the creation and development of the SE sector in Thailand (Beckert, Citation2010; Fligstein & Dauter, Citation2007; Kerlin, Citation2010, Citation2017) see . In addition, we identify the key policy initiatives and growing state and market influence in and the interplay between the various networks (Beckert, Citation2010; Kerlin, Citation2017, Citation2010). By identifying the growing institutional influence of the state and private sector collaboration in Thai SE development, we have unveiled growing concerns of SE co-optation by the corporate sector. This could be an example of institutional mimicry (Lawrence & Suddaby, Citation2006). Combining these three very useful theoretical perspectives as facilitated a systematic approach to unpacking social enterprise sector development in Thailand. Using Kerlin’s MISE framework, our data shows that Thailand demonstrates an example of an Authoritarian State-Corporate model, which the authors identify as a new category of the Strategic Diverse and semi-strategic model in Kerlin’s (Citation2017) country typology. This is in contrast to South Korea where the Government has prioritized the non-profit sector as its key partner in stimulating SE Growth (Jeong, Citation2017).

It is clear the situation in Thailand for SE is very dynamic. Future research, should investigate further the private sector motivations and their potential to deliver social innovation and impact at scale versus the concerns regarding co-optation. There is also limited research in Thailand on the management of social enterprise in this context, which could be valuable to inform both future government policy and the work of the Social Enterprise Thailand Association in trying to influence institutional rules.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bob Doherty

Bob Doherty is Professor of Marketing and Chair of Agrifood at the University of York and leads a 4-year interdisciplinary research programme on food resilience titled ‘IKnowFood’ (Global Food Security fund). Bob is also the research theme leader for food in the York Environmental Sustainability Research Institute (YESI). In addition, he has recently been seconded into UK Government Department, DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) as a senior policy fellow to work on Food Systems policy development. Bob is now also co-investigator on the STFC Food Network phase 2 programme of work. Bob specializes in research on the management aspects of social enterprise hybrid organizations competing in the food industry. He is currently a trustee on the board of the Fairtrade Foundation. Founding Editor Emeritus of the Social Enterprise Journal- after 10-years as Editor in Chief of the Social Enterprise Journal published by Emerald publishers. Prior to moving into academia Bob spent 5-years as the Head of Sales and Marketing at the Fairtrade social enterprise pioneer Divine Chocolate Ltd.

Pichawadee Kittipanya-Ngam

Pichawadee Kittipanya-ngam is an assistant professor of operations management at Thammasat Business School, Thailand. She is also a research affiliate at Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge. Pichawadee specializes in research and practices on supply chain and management aspects of social enterprises. She is also a founder of Cambridge Babies, a social project encourages the early year development. The project in collaboration with Cambridge Thai Foundation, annually donates part of profits as scholarships to Thai students at the University of Cambridge.

References

- Aspers, P., & Beckert, J. (2011). Value in markets. In The worth of goods: Valuation and pricing in the economy (pp. 3–38). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing. Insights from the study of social enterprises. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 397–441. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2014.893615

- Bazeley, P., & Jackson, K. (2013). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Beckert, J. (2010). How do fields change? The interrelations of institutions, networks, and cognition in the dynamics of markets. Organization Studies, 31(5), 605–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840610372184

- Berndt, C., & Boeckler, M. (2009). Geographies of circulation and exchange: Constructions of markets. Progress in Human Geography, 33(4), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132509104805

- Berndt, C., & Boeckler, M. (2011). Geographies of markets: Materials, morals and monsters in motion. Progress in Human Geography, 35(4), 559–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510384498

- Billis, D. (Ed.). (2010). Hybrid organizations and the third sector: Challenges for practice, theory and policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Callon, M. (1998). The embeddedness of economic markets in economics. In M. Callon (Ed.), The laws of the markets.(pp.1-57) Blackwell Publishers.

- Callon, M. (2007). An essay on the growing contribution of economic markets to the proliferation of the social. Theory, Culture & Society, 24(7–8), 139–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407084701

- Chandra, Y., & Wong, L. (2016). Introduction. In Y. Chandra & L. Wong (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship in the Greater China Region: Policy and cases.(pp.1-7). Routledge.

- Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2003). Business research: A practical guide for undergraduate and post graduate students. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cui, T. S., & Kerlin, J. A. (2017). China: The diffusion of social enterprise innovation: Exported and imported international influence. Shaping Social Enterprise: Understanding Institutional Context and Influence, 79–107.https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78714-250-320171004

- Cukier, W., Trenholme, S., Carl, D., & Gekas, G. (2011). Social entrepreneurship: A content analysis. Journal of Strategic Innovation and Sustainability, 7(1), 99–119. http://www.na-businesspress.com/JSIS/cukier_abstract.html

- Dart, R. (2004). The legitimacy of social enterprise. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.43

- Dees, J. G., & Elias, J. (1998). The challenges of combining social and commercial enterprise. Business Ethics Quarterly, 8(1), 165–178.https://doi.org/10.2307/3857527

- Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2006). Defining social enterprise. In M. Nyssens (Ed.), Social enterprise: At the crossroads of market, public policies and civil society (pp. 3–26). Routledge.

- Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2017). Fundamentals for an international typology of social enterprise models. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(6), 2469–2497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9884-7

- DiMaggio, P. (1991). Constructing an organizational field as a professional project: U.S. art museums, 1920‒1940. In W. W. Powell & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp.1-38). University of Chicago Press.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). Introduction. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (p.38). University of Chicago Press.

- Djelic, M. L. (2004). Social networks and country to country transfer: Dense and weak ties in the diffusion of knowledge. Socio-Economic Review, 2(3), 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/soceco/2.3.341

- Doherty, B., Davies, I. A., & Tranchell, S. (2013). Where now for fair trade? Business History, 55(2), 161–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.692083

- Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12028

- Doherty, B., Smith, A., & Parker, S. (2015). Fair trade market creation and marketing in the global south. Geoforum, 67 (December), 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.04.015

- Elinoff, E. (2014). Unmaking civil society: Activist schisms and autonomous politics in Thailand. Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs, 36(3), 356–385. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs36-3b

- Elinoff, E. (2019). Subjects of politics: Between democracy and dictatorship in Thailand. Anthropological Theory, 19(1), 143–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499618782365

- Fernández-Laviada, A., López-Gutiérrez, C., & San-Martín, P. (2020). The moderating effect of countries’ development on the characterization of the social entrepreneur: An empirical analysis with GEM data. Voluntas, 31(3), 563–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00216-7

- Fligstein, N., & Dauter, L. (2007). The sociology of markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 33(1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131736

- Garud, R., Jain, S., & Kumaraswamy, A. (2002). Institutional entrepreneurship in the sponsorship of common technological standards: The case of Sun Microsystems and Java. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 196–214. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069292

- Gephardt, R. (2004). What is qualitative research and why is it important. Academy of Management Journal, 7(4), 454‐62. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2004.14438580

- Gillett, A., Loader, K., Doherty, B., & Scott, J. M. (2018). An examination of tensions in a hybrid collaboration: A longitudinal study of an empty homes project. Journal of Business Ethics, 157, 949-967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3962-7

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/228311

- Hofstede Insights. (2020). What about Thailand? Retrieved April 1, 2020. Hofstede Insights. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country/thailand/

- Jaffee, D. (2010). Fair trade standards, corporate participation, and social movement responses in the United States. Journal of Business Ethics, 92(S2), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0583-1

- Jaffee, D., & Howard, P. (2010). Corporate cooptation of organic and fair trade standards. Agriculture and Human Values, 27(4), 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9231-8

- Jeong, B. (2017). South Korea: Government directed social enterprise development: Toward a new Asian social enterprise country model’. In Kerlin, J.A.(Ed.), Shaping social enterprise (pp. 49–77). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Kerlin, J. A. (2010). A comparative analysis of the global emergence of social enterprise. Voluntas, 21(2), 162–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-010-9126-8

- Kerlin, J. A. (2017). Shaping social enterprise: Understanding institutional context and influence. Emerald Publishing Ltd.

- Laville, J. L., & Nyssens, M. (2001). The social enterprise: Towards a theoretical socio-economic approach. In C. Borzaga & J. Defourny (Eds.), The emergence of social enterprise (pp. 312–332). Routledge.

- Lawrence, T. B., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutions and institutional work. In Clegg, R., Hardy, C., Lawrence, T.B. and Nord, W.R.(Eds.,), The Sage handbook of organization studies (pp. 215–254). London: Sage.

- Lepoutre, J., Justo, R., Terjesen, S., & Bosma, N. (2013). Designing a global standardized methodology for measuring social entrepreneurship activity: The global entrepreneurship monitor social entrepreneurship study. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 693–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9398-4

- Lien Centre for Social Innovation. (2014). From charity to change: Social investment in selected Southeast Asian Countries [Online]. Retrieved March 9, 2016. Lien Centre for Social Innovation. http://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/lien_reports/11/

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic enquiry. Sage Publications.

- Lumpkin, G. T., Moss, T. W., Gras, D. M., Kato, S., & Amezcua, A. S. (2013). Entrepreneurial processes in social contexts: How are they different, if at all? Small Business Economics, 40(3), 761–783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9399-3

- Maak, T., & Stoetter, N. (2012). Social entrepreneurs as responsible leaders:‘Fundación Paraguaya’and the case of Martin Burt. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1417-0

- Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.09.002

- Mason, C., & Doherty, B. (2016). A fair trade-off? Paradoxes in the governance of fair-trade social enterprises. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(3), 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2511-2

- Mintzberg, H. (1989). Mintzberg on management: Inside our strange world of organisations. Free Press.

- Morgan, D. L. (1988). Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage.

- Murphy, P. J., & Coombes, S. M. (2009). A model of social entrepreneurial discovery. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9921-y

- Pache, A. C., & Santos, F. (2013). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 56(40), 972–1001. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0405

- Paroutis, S., & Heracleous, L. (2013). Discourse revisited: Dimensions and employment of first‐order strategy discourse during institutional adoption. Strategic management journal, 34(8),935-956. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/smj.2052

- Peattie, K., & Morley, A. (2008). Eight paradoxes of the social enterprise research agenda. Social Enterprise Journal, 4(2), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/17508610810901995

- Peredo, A. M., & McLean, M. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: A critical review of the Concept. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.007

- Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovation (4th ed.). New York Free Press.

- Ruef, M., & Scott, R. W. (1998). A multidimensional model of organisational legitimacy: Hospital survival in changing institutional environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(4), 877–904. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393619

- Rueschemeyer, D. (2009). Usable theory: Analytic tools for social and political research. University Press.

- Santos, F. M. (2012). A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1413-4

- Scott, W. R. (2008). Approaching adulthood: The maturing of institutional theory. Theory and Society, 37(5), 427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-008-9067-z

- Sengupta, S., & Sahay, A. (2017). Social entrepreneurship research in Asia-Pacific: Perspectives and opportunities. Social Enterprise Journal, 13(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-11-2016-0050

- Smith, W. K., & Tracey, P. (2016). Institutional complexity and paradox theory: Complementarities of competing demands. Strategic Organization, 14(4), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127016638565

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- Teasdale, S. (2012). Negotiating tensions. How do social enterprises in the homelessness field balance social and commercial tensions? Housing Studies, 27(4), 514–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2012.677015

- Thelen, K. (1999). Historical Institutionalism in comparative politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 2(1), 369–404. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.369

- Vickers, I., & Lyon, F. (2013). Beyond green niches? Growth strategies of environmentally-motivated social enterprises. International Small Business Journal, 31(4), 1–22 or ESRC Third Sector Research Centre Working paper 108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242612457700

- Wilson, F., & Post, J. E. (2013). Business models for people, planet (and profit): Exploring the phenomena of social business, a market-based approach to social value creation. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 715–737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9401-0

- World Bank. (2020). Governance effectiveness. Retrieved April 3, 2020. World Bank Policy Research Group. http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home

- World Economic Forum. (2018). The global competitiveness report. Retrieved April 2, 2020. World Economic Forum. https://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-report-2018/the-global-competitiveness-report-2018/

- Wry, T., & Zhao, E. Y. (2018). Taking trade-offs seriously: Examining the contextually contingent relationship between social outreach intensity and financial sustainability in global microfinance. Organization Science, 29(3), 507–528. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1188