ABSTRACT

Background

Children and youth with severe motor and communication impairment (SMCI) have difficulty providing self-expression through typical speech, writing with a paper and pencil, or using a standard keyboard. Their emotional expressions can be missed by peers and novel caregivers.

Purpose

To describe the indicators and components of emotional experiences for children/youth with SMCI.

Methods

Primary guardians of nine children/youth with SMCI were involved in photo/video data collection and follow-up qualitative interviews. Twenty-one familiar people (e.g., friends, family members, and/or care team) participated in semi-structured qualitative interviews.

Results

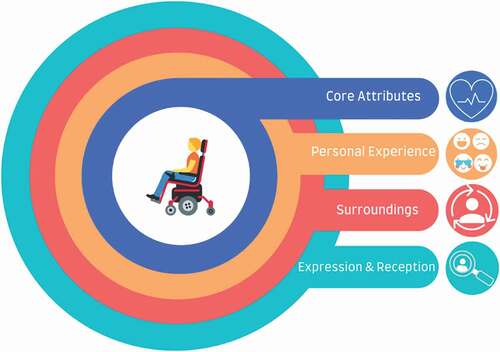

A conceptual understanding of emotional well-being specific to the population has been developed consisting of nine themes, encompassed by four domains i) Core Attributes, ii) Personal Experiences, iii) Surroundings, iv) Expression and Reception.

Conclusions

Emotional experiences of children/youth with SMCI are diversely expressed. Primary guardian and familiar person insight can be amplified to positively impact care and participation.

Introduction

Children and youth with severe motor and communication impairment (SMCI) experience difficulties communicating through typical speech, writing with paper and pencil, or typing using a standard keyboard. They often express themselves through one or a combination of body gestures, vocalizations, posture, breathing, or facial expression.Citation1–3 Children and youth with SMCI are diversely defined across academic disciplines (i.e., rehabilitation science, engineering, psychology, education, and medicine) and therefore their prevalence is challenging to estimate (approximately 0.5–4%).Citation4–6 The combination of physical, communication, and social participation limitations often experienced by children and youth with SMCI impact their opportunities for interpersonal interactions. People who are unfamiliar with the child or youth might ignore or have difficulty understanding their emotions, ideas, and wishes.Citation7–9 A clear description of how to define the emotional well-being of children and youth with SMCI is absent from the literature.

Children and youth with SMCI is a working definition used to conduct this research, the term focuses on children and youth in terms of their functional abilities, regardless of cognitive impairment. The term SMCI captures children and youth with a range of cognitive abilities. The Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) and the Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) can be used to describe gross motor and communication abilities of children and youth with SMCI; the systems do not involve assessments or tests.Citation10 Children and youth with SMCI are those that fall between levels III–V on both the GMFCS and the CFCS (see ). Levels III, IV, and V on the GMFCS encompasses children who may require a hand-held mobility device (e.g. walker), a manual wheelchair, powered mobility, or other additional support to move around in their environments.Citation11 Levels III–V on the CFCS classifies children who are effective at communicating with familiar partners, children who are sometimes effective communicating with familiar partners, and children who are unable to effectively communicate with unfamiliar or familiar partners.Citation10

Table 1. GMFCS and CFCS III–V Level Distinction.

Underlying diagnoses in children and youth with SMCI influence their functioning but may limit attitudes toward their capacity and misrepresent actual functioning. The categorical terms used outside of this research, which overlap with children and youth with SMCI include: children with medical complexity (CMC), cerebral palsy (CP), rare diseases, and severe and multiple disabilities.Citation12–15 Other diagnoses and conditions may also fall under the umbrella term of children and youth with SMCI.Citation16 Children and youth with SMCI can have additional multi-sensory impairments, such as visual and auditory difficulties.Citation17–19 Although children and youth with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) may experience combined motor and communication delays, the barriers of communication expression for children with ASD present an additional layer of complexity and limitation to communication, which would benefit from being studied separately from children and youth with SMCI as a whole.Citation20,Citation21

The paucity of evidence regarding emotions of children and youth with SMCI makes it difficult to know the status of their emotional well being; however, children with solely motor or communication impairments present emotional well-being concerns.Citation22–28 Children who have severe motor impairments, miss more days of usual activity (i.e., school or everyday routine participation) and are found to have lower mental health scores as compared to children with moderate motor impairment.Citation22 Studies have shown that children with severe motor impairments experience greater psychological concerns as compared to peers without SMCI.Citation23–25 Mental health concerns including depression and anxiety have been reported for children and youth with specific language impairment.Citation26–28 Accordingly, children and youth with severe disabilities and communication problems,Citation17 and language delaysCitation18 are at an increased risk of abuse, neglect, and social isolation.Citation29,Citation30 Thus, children and youth with SMCI who have both motor and communication impairment are at risk of experiencing well-being concerns. The outcome measures used to assess emotional well-being for children with only mobility or communication impairments are likely to be incomplete for assessing children and youth with SMCI.

A description of the specific aspects and experiences contributing to emotional well-being for children and youth with SMCI is absent from the literature. The Child and Youth Wellbeing Index indicates that emotional well-being is one of the seven domains of life,Citation31,Citation32 yet the term is often loosely defined and a universally appropriate conceptual model does not exist. When measured as a sole construct, emotional well-being has been broadly distinguished as the ratio of pleasant to unpleasant emotions in an individual’s life.Citation33 Pediatric conceptualizations of emotional health are grounded in positive psychology and developmental theory,Citation34,Citation35 which focus on relationships and contexts that contribute to life course development of typically developing children.Citation34–39 Children and youth with SMCI might not develop similarly to their peers without disability in regard to cognitive, physical, social, and communicative aspects.Citation40 Prior research indicates that emotional experiences related to well-being of children with physical disabilities or communication impairments involve positive experiences in three key components: self-esteem,Citation41 school participation,Citation42–44 and sense of belonging.Citation45,Citation46 The complexity of interaction among these three components may affect the emotional experiences of children and youth with SMCI who have distinctly different experiences with school environments, interpersonal relationships, and everyday life than children without concomitant impairment.Citation44,Citation47,Citation48 A more specific description of observable components of emotional well-being is needed for researchers, clinicians, and people who are unfamiliar with children and youth with SMCI, to know how to assess the emotional well-being of these children and youth.

Conceptual and Theoretical Framing of Emotional well-being

To approach this research, the authors rooted their understanding of emotional well-being in conceptual and theoretical literature to inductively explore the construct for children and youth with SMCI. The ‘Concepts to Indicators of SEWB’ illustrates three different theories of well-being rooted in philosophy and social theory.Citation49–53 Child SEWB is described relative to relational/environment and self/personal domains. The self/personal domain involves ‘internal’ components, such as the ability to experience, manage, and appropriately express emotions.Citation54 The environmental domain consists of three spheres: the family/home, school, and community.Citation55–57 The SEWB model highlights the importance of primary guardian-child/youth relationships and peer relationships to well-being. The SEWB model is grounded in positive psychology and developmental theory. Positive psychology focuses on aspects of life that cause fulfillment at subjective, individual, and group levels; without fixating on diminishing the negative aspects of life.Citation58 Sameroff’s Unified Theory of Development emphasizes the interconnectedness between an individual and their context, which can be used to explain child development.Citation59 Across the life-span each individual may have body and mind changes or plateaus alongside environmental changes, which may be independent of each other and also to some degree, a consequence of experience.Citation59 Lastly, the ICF reflects a biopsychosocial modelCitation60 of disability that is necessary to use as a lens to approach this research and understand children/youth (with or without impairment) and their health/disability in relation to biological, psychological, and social aspects of their lives.

The overall purpose of this study was to conceptually describe the emotional well-being of children and youth with SMCI. The first objective was to identify observable indicators and components of emotional well-being of children and youth with SMCI. The second objective was to explore the emotional experiences of children and youth with SMCI across different relationships and contexts. Children and youth with SMCI involved in this study are unable to directly provide narratives about their emotional well-being, therefore, their experiences were attempted to be best understood by people in their lives who know them well across multiple relationships and settings to appropriately aggregate information about their experiences. This study aimed to respectfully represent the voices of children and youth and where possible directly engage them in research.

Reflexivity Statement and Positionality

The authors of this article are made up of individuals with diverse academic backgrounds and personal experience. The authors involve professionals in fields of rehabilitation science, mechanical and materials engineering, augmentative and alternative communication, and neuroscience. Further, the previous professional experiences of our authors involve social work, psychology, and psychotherapy. All authors identify their knowledge of disability, health, and disease through a biopsychosocial lens. The authors have diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds, they identify their awareness of understanding personal experiences of participants as being influenced by personal, social, and cultural components. The primary researcher does not have clinical experience with children and youth with SMCI, whereas all other authors have ample experience with the population. The norms and nuances of the population were important for the primary researcher to understand, reflect upon, and share with the audience through both text and photo-based data.

The authors identify their positionality as aligning with a social constructivist ontological position. They believe that reality is socially constructed by individuals and social groups. As such, the experiences of individuals require at least some level of interpretation as multiple perspectives and understandings of an experience exist. The authors’ epistemological position is made up of interpretivist and pragmatic views in which experiences must be interpreted, and how persons can go about determining or understanding the interpretation of experience can be accomplished in realistic attempts to gain the desired knowledge.

Methods

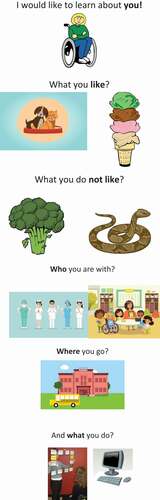

The primary researcher obtained ethics approval from her institution. Combined letters of information were provided for all primary guardians and their child/youth participant. Child/youth-specific letters of information were additionally provided which offered simplified text and visuals (see Appendix A). Each primary guardian provided consent for all child and youth participants during initial consent/assent online video meetings. Three youths were present in the initial consent/assent meetings and self-expressed their own consent (i.e., confirmed by primary guardian knowledge of child idiosyncratic behavior). For the six participants absent from initial consent/assent meetings, primary guardians were instructed to go through the child/youth letter of information with them to assess if the project was in the child’s best interest and presented in a way that aided their knowledge to the best of their abilities. Primary guardians were asked to ensure ongoing assent of their child throughout the project, which included that they had to confirm they would not take photos of their child if they were dissatisfied and clearly unhappy participating. Primary guardians and familiar people (over 18) involved in qualitative interviews provided verbal consent. A verbal consent log was maintained by the first author for all participants.

Research Design

This project comprised of a two-phase study ontologically based in constructivism.Citation61,Citation62 The authors’ epistemological position is composed of interpretivist and pragmatic views.Citation63 This research aimed to synthesize multiple informants’ insights of the emotional experiences of child/youth participants, in lieu of the ability to collect ample experiential information directly from children and youth with SMCI (due to child/youth functional ability). Integrated conceptual and theoretical underpinnings (i.e., SEWB Model, Positive Psychology, Developmental Theory, and the ICF)Citation49,Citation59,Citation60,Citation64 informed the understanding of the population (children and youth with SMCI) and the construct of interest (emotional well-being) required to inductively explore this area of research. Subsequently, knowledge gained from conceptual and theoretical underpinnings informed recruitment of the study participants (i.e., children/youth and people from their social circles), and the approach applied to understanding emotional well-being specific to children and youth with SMCI.

An inductive qualitative descriptive design was used to provide a rich description of participant experiences, through illustrating the meaning that informants ascribe to participant experiences.Citation61,Citation65,Citation66 A qualitative description design allowed flexibility in implementing multiple methods of data collection (i.e. photo/video data collection and qualitative interviews).Citation65,Citation66 Further, a qualitative descriptive design enabled data to be interpreted while also remaining “close” to participants’ own narrativesCitation61,Citation65,Citation66 and providing raw quotes from interviews.

Children and youth were encouraged to be involved where possible in the following aspects of the study: i) taking photos/videos, ii) directing photos, and iii) being involved in qualitative interviews with their primary guardian (i.e., being present and confirming yes/no for probed questions). Photos and videos were used to capture observable indicators and components of emotional well-being. Photos and videos were also used as cues to elicit informant descriptions about the child’s emotional experiences at a specific time; insight from interview transcripts were analyzed using inductive qualitative content analysis. Multiple people familiar with the child were interviewed to ensure a comprehensive understanding of child/youth experiences across diverse relationships and contexts.Citation65 This approach supported the development of a comprehensive conceptual description of emotional well-being for children and youth with SMCI.Citation61,Citation62,Citation67–69 There were varied contributors of information to this study, descriptors and their involvement in the study are provided in to ensure a clear understanding of the process and findings.

Table 2. Contributor descriptors.

All participants (children and youth) were unable to provide in-depth dialogue about their experiences; therefore, no quotes were provided by youth. The quotes found in the findings of this manuscript are provided by primary guardians and familiar people, pseudonyms are used.

Eligibility and Recruitment

Participants

Children and youth were eligible to participate based on the following inclusion criteria: i) between 5 and 25 years old, ii) difficulty communicating with unfamiliar partners, iii) unable to independently walk in most settings, iv) difficulty handling objects, and v) primary guardian-reported dysarthria or absence of language/speech. The age range (5–25 years old) was specified in accordance with Noyek et al. (2020), which represents school-age range for children and youth with SMCI.Citation70 Multiple international health assessments and school-related participation guidelines specify children/youth as under 25 years old.Citation71–73 Due to previous emphasis on developmental theory for pediatric emotional well-being literature, the age range of participants intended to potentially include children (5–12 years old), adolescents (13–18 years old), and youth (19–25 years old). Although development does not always align with age, this sampling approach allowed inclusion of various developmental abilities without conducting developmental assessments that were not feasible within the scope of the project. A minimum age bracket of five years of age was established to reflect comprehension and expression of typically developing children; children as young as five years old can complete traditional self-report outcome measures.Citation74 See Appendix B for the eligibility screening tool used to screen primary guardians and child/youth participants for inclusion in the study (based on the GMFCS and CFCS). Children and youth with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis were excluded due to the added complexity of social and communication limitations associated with ASD, as per previous studies.Citation20,Citation21 Primary guardians of children and youth with SMCI were required to comprehend and communicate fluently in English as per self-report.

Purposive samplingCitation75 for participants and their primary guardians aimed to include diversity across the following characteristics: urban/rural home,Citation76 ethnicity of families,Citation74 family structure (one/two primary guardians, foster, same sex couples, etc.),Citation25,Citation49,Citation77 children in school versus not, and presence/quantity of siblings. The primary researcher accomplished recruitment solely through social media. A research-specific profile was created on Twitter and Facebook to connect with families. The primary researcher shared recruitment information within Facebook groups that comprise of primary guardians of children with disabilities who live in diverse geographical locations within Canada (including urban and rural living). Although a diverse sample was intended, due to the limited number of families of children with SMCI and difficulty recruiting during the COVID-19 pandemic limited diversity occurred across the sample.

Familiar People

Each primary guardian referred up to five people who personally knew their child/youth. Primary guardians notified familiar people about the project prior to providing the primary researcher with their contact information through e-mail correspondence. Criteria suggested to primary guardians when selecting informants included the following: ‘People who have a close relationship to your child/youth, who have an understanding of their emotional expressions; this many include family members, teachers, respite workers, etc.’ Subsequently, the primary researcher ensured all familiar people could comprehend and communicate fluently in English. Informant sampling occurred to purposively select individuals who could provide the most appropriate perspectives for the study’s purpose.Citation78 A prescriptive criterion was not applied with respect to hours spent per week with the participant or specific roles of care. Purposive criterion broadly addressed diversity across the roles and settings of interaction (between participant and familiar people). For example, familiar people comprised of care providers, siblings, or friends; familiar people interacted with participants within the home, school, organized day program, or health-care setting.

Data Collection

Phase 1

Modified photovoice methodsCitation79–82 were the focus of this phase, where primary guardians obtained photos and videos of the participant. The primary researcher reviewed the objective with primary guardians who then captured visual data that provided insight about the emotional well-being of their child/youth.Citation79,Citation83 The primary researcher provided the following prompts for primary guardians (and children/youth where possible) to use while collecting photos/videos: i) how does the child look when they are expressing different emotions?, ii) what aspects of their daily life make them feel different ways? Primary guardians captured photos and videos across a 5-day span and provided short descriptions of each photo/video. If necessary, more time was allocated for photo/video data collection. A data collection app was introduced as a secure platform that allowed participants to upload photos and videos with a corresponding description of each photo/video (accessible through mobile phone or tablet devices). Primary guardians who chose not to use the app provided photos/videos and short written descriptions through Microsoft Teams or through the primary researcher’s institution e-mail.

Primary guardians participated in a qualitative interview with the primary researcher to discuss photos and videos captured.Citation84–86 Qualitative interviews were conducted within four weeks of visual data collection. All qualitative interviews with primary guardians were conducted within four months. Qualitative interviews were conducted through Microsoft Teams or an encrypted version of Zoom and lasted approximately 1.5 hours. The focus of the qualitative interview was to gain an in-depth understanding of the photos/videos captured by primary guardians. The interview guide was based on the ‘PHOTO’ promptCitation87,Citation88: i) describe your Picture, ii) what is Happening here?, iii) why did you take a picture Of this?, iv) what does this picture Tell us about your life?, v) how can this picture provide Opportunities for us to improve life or understand your child/family? Further emotional well-being related dialogue naturally occurred. In cases where there was a large number of photos/videos, the primary researcher refrained from sticking closely to the prompts and allowed the interviewee to talk freely about the photos/videos in relation to emotional well-being for their child/youth. Qualitative interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim; personal identifiers were removed, such as names of schools and cities.

Phase 2

The primary researcher interviewed familiar people online (i.e. Microsoft Teams or encrypted version of Zoom) using a semi-structured interview guide (see Appendix C), which was developed based on primarily empirical pediatric well-being literature.Citation8,Citation25,Citation89–93 The primary researcher addressed all questions within the interview guide for all interviews, however, ample time was provided for the interviewee to freely share their understanding or experiences of the child/youth emotional well-being. All interviews involving familiar people were completed within five months.

Demographic information was also collected at the time of the interview. Interviews took approximately 1-hour and were audio recorded. All interviews were transcribed verbatim, personal identifiers were removed.

Member Check and Rigor

Each primary guardian and their child/youth met with the primary researcher online for a final update about the progress of the study. The meeting involved member checking, which consists of discussing the findings of the project with children/youth and primary guardians, to ensure content appropriately represented families and supported applicability of findings.Citation94–96 This process of member checking enhanced the credibility of the research. The primary researcher presented two project video summaries, one for primary guardians and another specific for children and youth. Children/youth and primary guardians were provided the opportunity to reflect and provide their thoughts/feedback about the findings. Presenting audience-specific video summaries ensured findings were shared in a comprehensible and engaging format. The first author maintained a detailed audit trail of all processes and events throughout data collection and analyses, which also enhanced trustworthiness of this work.

Analyses

Qualitative content analysis was used to describe a phenomenon or experience in a conceptual form.Citation97,Citation98 An epistemological approach rooted within interpretivism and pragmatism enabled the investigation of the emotional experiences of children and youth who cannot directly self-express ample experiential information.Citation63,Citation65 Analyses focused on both manifest and latent content.Citation97 Manifest content was considered the blatant description of emotional experience components, such as informant reports of emotional states.Citation99,Citation100 Latent content involved the interpretation of underlying meaning of text related to emotional well-being concepts.Citation99,Citation100 Both manifest and latent content were subjected to interpretation, with varying levels of abstraction which contributed to varying levels of conceptual description.Citation98

The primary researcher utilized an inductive approach to qualitative content analysis as described by Elo et al. (2008), which involved the following: i) preparing, ii) organizing, and iii) reporting.Citation97,Citation101 The preparing stage consisted of the primary researcher familiarizing herself with the data, the primary researcher listened to the audio recordings of each interview two times, transcribed all interviews, and then read through transcripts three times.Citation98 The ‘organizing’ stage involved open coding, creating categories, grouping codes/categories, and a general description of the topic through abstracting sub-categories.Citation101 Open coding was accomplished by two researchers independently using NVivo12 software, each researcher labeled words, phrases, or paragraphs with categories.Citation102 The researchers met to discuss developing codes and categories, any inconsistencies were further discussed and a third researcher was consulted to reach consensus on disagreements.

The primary researcher created a codebook (based on consensus of the three researchers) to systematically generate an exhaustive list of codes and their overarching categories. Citation98,Citation103 The codebook presented definitions of codes and examples of transcript quotes encompassed by each code; the secondary researcher confirmed all entries of the codebook.Citation98,Citation104,Citation105 The reporting of themes and subthemes was accomplished through iterative meetings with the research team to represent content appropriately, and to conceptually describe the emotional well-being of children and youth with SMCI. Citation101,Citation103 Themes and subthemes represented latent content, this encompassed the relationships between categories/codes.Citation98 Categories/codes were mainly descriptive in nature, representing manifest content. Citation98

Findings

A total of nine children/youth with SMCI and their families participated in this study. Although children and youth were encouraged to participate in all aspects of the study in which their primary guardian participated in, due to functional ability no children/youth were involved in capturing photos/videos, two children/youth were present in the primary guardian interview, and no child/youth could provide narratives about their emotional well-being. Eight families resided in Ontario, Canada (89%). Other child/youth and family demographic information is found in . All primary guardians were between 35 and 50 years old. Additional primary guardian-focused demographic information can be found in Appendix D.

Table 3. Participant, family, and familiar person demographic information.

Twenty-two familiar people participated in qualitative interviews for phase 2 of the project. Although up to five familiar people were allowed to be involved in the study, the number of familiar people who participated in phase 2 for each participant (child/youth) ranged from 1 to 4 individuals. This emphasized the variance in size of close social circles of children/youth and families. An average of two familiar people were interviewed per participant. Two qualitative interviews involved grandparent couples that asked to be interviewed together. Eighteen familiar people were female (82%), 19 (86%) familiar people were over the age of 25 years old, 11(50%) were relatives, eight (36%) were care providers, and two (9%) were friends of the participant or family. See for demographic information of familiar people.

Conceptual Understanding of Emotional well-being

The qualitative findings illustrate the conceptual understanding of emotional well-being for children and youth with SMCI through the development of four domains (see ), which encompass nine themes and 33 subthemes (see ). As the subthemes, themes, and domains developed within the analyses, the research team worked together to propose how the ideas fit to convey the emotional well-being of children and youth with SMCI. Qualitative descriptive studies can involve the representation of data in a meaningful and comprehensible form that best fits the data,Citation67 which was considered in the development of the figure. The research team iteratively worked through representations of the domains, themes, and subthemes and created the following figure. Each domain is depicted as four different layers surrounding the child/youth: i) Core attributes, ii) Personal experience, iii) Surroundings, and iv) Expression and receptions. Each layer is intentionally positioned relative to the child/youth in the center.

Table 4. Domains, themes, and subthemes.

The domain Core attributes resides closest to the child/youth. Core attributes are ‘close’ to the child and are difficult or impossible to modify. This domain includes the themes: Physical health and pain; Individual characteristics. The next layer outwards from the center comprises of Personal experiences. This domain includes the following themes: Emotional experience; Meaningful experience. The third layer is the domain Surroundings, this includes external factors within the social environment that can impact personal experiences (family, groups/networks, organizations, institutions, and community). This domain consists of the following themes: ‘That’s life’; Interactive production or regulation of emotion; Opportunities for play, learning, and engagement. The final most outer layer is the domain Expression & reception. This final domain encompasses the way emotions/experiences are expressed by children/youth and how they are perceived by others. The Expression and reception domain involves the themes Indicators; and Detectors, interpreters, and enablers. The latter domain and its underlying themes/subthemes are specific to the reception of child/youth emotional expression by interpreters, which may or may not involve reciprocal communication. Themes and subthemes are further described with accompanying quotes from qualitative interviews with primary guardians and familiar people, pseudonyms are used.

Theme 1: Physical Health and Pain

‘Physical health and pain’ is a theme characterized by the overall body-system function of participants. This theme involved being ‘sick’ or experiencing profound physical discomfort, which may be influenced by preexisting illness. In the subtheme ‘Health status,’ levels of wellness and illness were discussed in terms of the presence of biological or physiological dysfunction, diagnoses, and symptoms. This subtheme encompassed topics related to ‘journey of the disease,’ medical technology, medications, and tiredness. ‘Journey of the disease’ brought up topics of seizures, headaches, and digestion/constipation issues. Medical technology and medications were discussed by informants as a part of daily life.

Medical technology supported the child/youth throughout the night; primary guardians highlighted that tiredness often resulted from a deprived night’s sleep. Tiredness narratives described how sleep disturbances or lack of restful sleep impacted irritability and mood throughout the following day(s). Primary guardians articulated that their child’s health status may present itself similarly to tiredness, which is necessary to decipher.

‘Um, well as a parent. I think her positioning and her look, there’s so much about her that tells me something’s up. Either she’s extremely tired, or she’s sick. So if she were to wake up in the morning and be like this....I know something’s not right’- Suzie’s Mother.

Suzie’s mother described the quote above with two photographs which starkly illustrated the difference in expression when Suzie was feeling ‘herself’ versus being unwell.

The subtheme ‘Physical pain’ was described as participants being in profound physical discomfort, their body or part of their body hurt. This also included pain due to frequent seizures, or gastrointestinal issues. Pain was expressed by participants who used various indicators, such as vocalizing ‘OW’ or specific expressions known by primary guardians and familiar people. Physical health and pain contributed to participants’ mood and ability to participate in daily activities.

Overall, narratives around health complications were indicated for all participants. At the time when interviews were conducted, all participants were relatively stable with respect to health status; however, primary guardians discussed recent seizures, and all mentioned physical pain narratives.

Theme 2: Individual Characteristics

The theme ‘Individual characteristics’ described qualities that are distinctive and significant to each participant. In the subtheme ‘Likes/Dislikes’ informants commented on participant preferences involving a focus on specific body positions (i.e., being in standing frame versus wheelchair), music genres, toys, activities, people, food, and sensory stimuli.

The subtheme ‘Personality’ captured a combination of characteristics and qualities. Participants were described by informants as having the following personality traits: caring, easy-going, silly, positive attitude, resilient, and thoughtful. Narratives related to having caring qualities involved participants carefully selecting Christmas gifts for specific people/family, expressing compassion for others’, and caring for children at shared services.

In the subtheme ‘Voice,’ informants described the use of intentional communication usually through vocalizations to initiate others’ engagement or express needs/opinions. Some participants can vocalize utterances interpretable by primary guardians or familiar people, others solely used vocalizations or changes in tone as a means of engagement or expression. Narratives indicated that participants ‘have a voice,’ consisting of an active and valid opinion. A primary guardian described how her son actively vocalizes with familiar guests present.

He just won’t stop making noise, and they are not necessarily happy excited noises and he’s not - He’s just (shrugs shoulders), he’s content, he’s happy, and he’s very vocal. Um and when were at home just by ourselves, I don’t think I have heard his voice yet today. – Kyle’s Mother

The subtheme ‘Understanding own world’ described how participants make sense of their physical world, the people in it, their community, places, and events. Participants were described as understanding conversations and being able to appropriately laugh within situations. Informants explained how participants can identify when they are approaching a familiar person’s home.

In the subtheme ‘More than their diagnosis’ informants described the lives of participants as being significant and meaningful. According to informants, participants were more engaging and interactive than would be indicated by the medical expectations identified by their diagnosis.

That picture and potentially others show that given Kyle’s diagnosis one wouldn’t expect that he would be able to be sitting up in a wheelchair like that or be engaged, or be able to express emotions … His diagnosis is pretty grim and dismal and so for physicians, for researchers, it’s a pretty grim diagnosis and prognosis to give to families. And so a lot of times the pictures that I have shared with other people with the same diagnosis as Kyle’s, it gives them a little bit of hope because his life isn’t so bad as what the research articles make it seem like it should be. – Kyle’s Mother

Other informants described participants being ‘more than their diagnosis’ with regard to being able to develop special connections and impact the lives of people close to them.

‘Yeah, I think Reid has a really neat way of pulling people in and making people feel good.’ – Reid’s sibling

‘More than their diagnosis’ also brought up narratives related to how participants are not any different than typically developing peers in certain aspects of their life. For example, topics involved participants ‘being a kid!.’ Informants also described the importance of enabling children and youth with SMCI to try the things other people like as well.

The subtheme ‘Development’ was described in terms of how participants may progress or plateau regarding biological, psychological, intellectual, and emotional growth. Children and youth with SMCI experience different experiential milestones than typically developing children. As such, their development can influence preferences, activities, and opportunities to try new things, which can contribute to emotional well-being.

By interviewing familiar people in addition to primary guardians, various preferences and personalities were described that depicted a wholistic understanding of participants. All primary guardians and familiar people mentioned having special relationships with participants and positive impact the participants had on their lives.

Theme 3: Emotional Experience

The theme ‘Emotional experience’ described participants’ conscious feelings or state of being. The subtheme ‘Range or variability of emotions’ was described as the diversity of emotions expressed by participants and the frequency of changing emotional states. Informants affirmed the emotions participants experience.

‘He has the full range of human emotions; he expresses them to the best of his ability, and it might not look like the way you and I express them but that does not indicate anything about their validity.’ – Brady’s Friend

A primary guardian described how quickly her daughter can experience an emotion and move onto the next.

‘She feels an emotion, processes it and she’s done and then she forgets about it, carries on with the next thing at hand’. – Sydney’s Mother

The subtheme ‘Magnitude of expression’ was described by informants as participants experiencing emotional states that vary in size. The magnitude of expression relayed different information depending on the context, situation, and participant. Some informants explained how the magnitude of expression can provide representation of experience.

His body position is a big response, when he lifts his head up and tilts it back and pushes forward with his arms like he is - that’s a big expression, and the sounds he makes and the look on his face, is what distinguishes it from a positive or a negative, but it’s a big response. – Joey’s Mother

Other informants described magnitude of expression in terms of having specific communicative purpose.

It (child’s expression) has to go BIG - It shows how a minor facial expression when you’re nonverbal doesn’t get people’s attention. – George’s caregiver

The subtheme ‘Emotional states’ involved informants explaining the vast emotion participants experience and express. Emotions included: being ‘at ease,’ excitement, happy, frustrated, sad, and upset. Additionally, informants described social emotions such as pride.

Participants varied in their experiences of emotions, some were described as having diverse emotional states, whereas others were described as experiencing emotions in terms of scaling from positive to negative valency. All participants were able to express emotions or communicative intent to primary guardians and familiar people in their lives.

Theme 4: Meaningful Experience

The theme ‘Meaningful experience’ involved experiences of significance for participants that emerged because of complex situations, places, or people. The subtheme ‘Disengagement when disrespected’ was described by informants as the reaction or behaviors, participants expressed when they were dismissed or when people did not pay attention to them.

“If somebody says something that’s hurtful or they you know have a look that he happens to see, or they don’t wait for him to answer … then he just ignores the person or he just will be quieter than usual after something, I know that it’s negatively affected him” – Reid’s Aunt

Other events of disengagement were a result of participants having preferences of care providers and lack of interest for unfamiliar people. For example, participants neglected to make eye-contact or engage with unpreferred clinicians.

The subtheme ‘Feeling involved’ consisted of participant’s experiences of being a part of ‘something,’ such as a group, a conversation, or an event. A primary guardian described how her son feels involved by doing ‘missions’ such as mailing a letter.

And it’s not just the help, it’s not just the coming for a walk … I gave him the letter to hold, even though it gets scrunched up. He likes to feel like he’s helping and, and taking part in it and being an active participant in it, which is important. – Reid’s Mother

The subtheme ‘Fun’ described experiences of lighthearted pleasure or entertainment accompanied with playful energy. An informant retells a story about playing pranks with a participant at the respite care center.

‘We (informant and participant) used to go around with like a whoopee cushion and fart guns to people’s offices here and like fart, outside their offices’. – Brady’s health care provider

The subtheme ‘Love’ encompassed references to the deep affection participants experience toward someone or felt by someone. One informant expressed verbal exchanges of love with a participant.

‘I love you and she goes “Aaaahhhh,” so she really, like – a big “ahhh” meaning her too.’ – Suzie’s Grandmother

The subtheme ‘Meaningful places and memories’ provided insight regarding the specific context or previous events that participants have a significant connection to. This included reference to feelings of connection to a church passed by on walks and specific music that brings memories of previous experiences.

Participants experienced emotional experiences to which they felt connected. The subthemes ‘Fun’ and ‘Feeling involved’ were prominent narratives. Fun arose out of experiences where primary guardians, caregivers, and service providers accepted opportunities to act like a kid or be silly. Participants heavily relied on others for ‘feeling involved’; in situations where support for inclusion was not possible, participants were unintentionally overlooked, and boredom resulted.

Theme 5: Interactive Production and Regulation of Emotion

This theme consisted of participant’s emotional states directly influenced by other individuals. Primary guardians and familiar people helped maintain or impact the feelings or emotional states of participants. Within the subtheme ‘Attachment between child/youth and familiar persons,’ topics related to attunement, regulation, and safety were described. Narratives emphasized close relationships between participants and people who understand their inner world and needs. Primary guardians and familiar people who are attuned to participants significantly influenced their emotional equilibrium and/or provided comfort. A caregiver described a participant’s way of self-regulation.

But when I said he won’t open his eyes – that’s another thing he does actually and used to do quite frequently at school when he’s had enough, or he’s overwhelmed, or he just wants to be done with something. Say it’s math, which he doesn’t love. He would simply close his eyes and refuse to open them. So, then we would just let him be because he can’t run away … can’t go to the bathroom or take a break. He would just basically shut down and then I’ll say like “Okay buddy we’ll give you a minute” and then he eventually opens them so … – George’s caregiver

Most narratives of emotional regulation described within interviews, explained participants’ reliance on primary guardians or familiar people to intervene and co-regulate their emotions. Primary guardians and familiar people used specific strategies to regulate participant’s emotions.

Ummm, covering her eyes sometimes will calm her down just because it’s, it’s, it blocks out all the sensory stuff you know. Or if I sniff her neck like if I cover her eyes and I sniff her neck, right – kiss her, she’ll calm down. – Sydney’s Mother

The subtheme ‘Others’ emotions mirrored or impact child/youth’ was described by narratives about how participants replicated the emotions of primary guardians and familiar people; or were impacted by the emotions of others. Participants were described as picking up on their caregivers’ emotions.

‘I think when we’re in a really good mood and then she gets in a really good mood. She kind of picks up on those vibes and she knows. But if we’re just kind of sad and down … it’s almost like she gets sad and down as well and then quieter’. – Sydney’s Caregiver

Overall, the interactive production and regulation of emotion highlighted intimate bonds children and youth with SMCI may have with familiar people and their primary guardians. Co-regulation strategies that primary guardians and familiar people used included sensory techniques, music, changing contexts, or other individual-specific strategies. The population of children and youth with SMCI presented unique components of emotional well-being related to their connection to and reliance on others for emotional regulation.

Theme 6: Interaction with Social Environment

Social environment encompasses a participant’s family, groups/networks, organizations/institutions/community.Citation106 The subtheme ‘Opportunities for play, learning, and engagement’ described the following topics: watching sports, being outside, travel, sensory play, playing sports or exercise, new experiences or learning, and accommodation for inclusion. The topic new experiences or learning encompassed conversations related to independence versus reliance on others for participation.

The subtheme ‘Attitudes surrounding child/youth’ encompassed topics related to how primary guardians and familiar people think and feel about someone or something. Attitudes can impact how primary guardians and familiar people interact with others and their environments; therefore, this indirectly impacts participant opportunities for engagement and diverse experiences. Attitudes of informants were related to ‘saying yes to opportunity,’ having a ‘good life,’ fearing the future for their child/youth, and acceptance of participants’ diagnosis/ability. Further, a primary guardian described the simple things that contributed to a ‘good life’ for her child and family.

There is broad joy and great times in our life and in lots of ways we have a very simple life based on very simple things, a comfortable position, or location in the house, some familiar and preferred objects and activities - singing songs together that is just joyful and fun and we are both very much present in the moment doing those things. – Joey’s Mother

Primary guardians and familiar people expressed perceptions of unfamiliar peoples’ attitudes included topics related to i) ignorance of the child/youth abilities or personhood, ii) weight of judgment from others, iii) ‘our life is not sad!,’ and iv) seeing ignorance as and opportunity for teaching others. The weight of judgment of unfamiliar people presented itself through the burden of others being uncomfortable around participants.

‘All the time people stare, all the time.’ – Corey’s Granparents

The experiences shared by primary guardians, which were related to the positive lives of children and youth with SMCI can inform unfamiliar people. A primary guardian described how her daughter’s life is different, while unfamiliar people tend to interpret that as a deficient life.

Yeah, I think it’s important for people to understand that even though life is different, it’s not bad like Carly’s reality is, you know she doesn’t, she probably won’t go to prom like as like her brothers did, but it’s not a bad thing she has other joys in life that are just as big. - Carly’s Mother

The subtheme ‘Family functioning’ consisted of overall cohesion, relationships, and organization of participants’ households and relatives involved. Narratives involved topics of being a ‘typical family’; rules and schedules; relaxing time as a family; parent engagement in child/youth life; pets; and parent being a full-time caregiver. Topics related to parent engagement were described by a familiar person (caregiver) who was impressed by the involvement, care, and commitment a participant’s parents had always provided for their son.

This couple provides so much to these children and they, they could have a very very sad and forgotten life without them and somebody like Kyle who is immobile he’s in a wheelchair um and he’s non-verbal, would be very easy to just park him in a corner at a table and just be forgotten, and yeah they go above and beyond to make sure that he’s practicing his walking and getting his mobility and has the exercises and the ummm, the toys and whatever he needs to make his day easier. – Kyle’s Support Worker

The sub-theme ‘Team of people supporting child/youth and family’ explained how the people personally close to the family and participant provided financial, social, and/or emotional help. Supportive people consisted of long-time friends, who truly care about participants and are trusted by the family.

The subtheme ‘Places’ involved the description of locations that were considered comfortable or unfamiliar to participants. This theme also described the complexity of the home in terms of the adaptations required to live within their house (e.g., assistive technology, medications, and 24/7 caregiving required).

In the subtheme ‘Interpersonal interaction,’ participants were described as enjoying connecting with others and/or being in the presence of people. Topics involved peer interaction, friends, attention, and physical touch. An informant described how she provides not only nursing care but also friendship.

Other than his sister I think I’m like, I was the youngest person he had hung out with in a very long time, so I think I brought like a different kind of energy … There was one time, where I set his computer up for him and he actually like went to the prompts and like made a sentence that was like “you’re my nurse … and my friend.” – George’s healthcare provider

Physical touch was described as snuggle time with family and the need for touch to connect with others. Physical touch was described as essential within organized programming/activities for children and youth with SMCI.

Hospice care is very different than any other type of medical care - like, except for now (during COVID-19 pandemic), we’re very much about like touch and like between staff and kids, like cuddling with kids who are too big to be cuddled you cuddle with like 16-year old nonverbal kids and like, but that’s because they need that. Or like kiddos laying next to each other and gazing at each other and holding hands on a mat or something. That’s a lot of like the kind of the therapy that we do here ‘cause they don’t have that being in a wheelchair. They don’t have the ability to do that like whenever they want … they can’t just go up and hug someone or hold someone’s hand when they want, they need someone to initiate that. – Brady’s healthcare provider

Physical touch and interpersonal interaction are some of the ways that children and youth with SMCI relate to others. Children and youth were negatively impacted by not seeing or being close to familiar people and family, which was often experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The theme ‘Interaction with social environment’ is a significant theme contributing to the emotional well-being of children and youth. Narratives highlighted that although children and youth may not be able to articulate verbally, they are positively impacted by others taking the time to talk to them and facilitate interaction/connection. Fewer narratives described peer interaction; participants typically spent time with adults versus individuals their own age.

Theme 7: ‘That’s Life’

The theme ‘That’s life’ broached the difficult and unpredictable life events or circumstances experienced by children and youth with SMCI. The subtheme ‘Been through a lot’ brought up comments of participants experiencing complex lives in general.

‘Like in some ways, I’d say he’s got an older perspective. Just because he has experienced so much loss for someone his age’. – Brady’s friend

The subtheme ‘Hospital visits’ included the description of numerous, frequent, or traumatic events in health-care settings. These visits were described as unpredictable and out the control of families.

In the subtheme ‘Sad events or hardships’ informants mentioned specific experiences with which participants had dealt with, such as death of a friend, wrongful treatment, or difficult medical procedures.

I think it’s just another thing that people need to acknowledge is, is how brave these kids are right? In facing things that most of us wouldn’t face in a full lifetime, but facing it as children. Whether it’s medical procedures, hospitalizations, their treatment … like discriminatory treatment, losing people. – Brady’s friend

Informants articulated the bravery and strength of participants as they overcame very difficult times. A primary guardian described a photo of their child as one of the hardest moments in the participant’s life, this is explained in the quote below.

I’m sure this is a photo you would post on like Facebook or something and, and people would you know comment on how happy and how great he looks, and this is probably the sickest point of his entire life so It’s the perception of what you’re seeing in the photo, as opposed to really what is truly going on. And so you know and George likes to hide that too, right? He wants other people to be happy. He doesn’t want people to be sad for him … you know that avert communication of what we all do – we all smile and say we are fine, this is George smiling and saying he is fine.- George’s Mother

The subtheme ‘Hearing others talk or talking about serious or sad things’ consisted of difficult conversations involving participants or conversations overheard by participants. Difficult conversations discussed participant health, illness, death, or serious topics. A primary guardian shared his realization of the importance of what information his child hears or how it is shared.

We’re kind of surprised that he’s sad, like … like there’s been times where we’ve been talking about him in a medical capacity and sometimes you know, because he’s nonverbal we maybe assume that he can’t hear or doesn’t understand and, and he starts crying. And it’s clear that he actually probably was understanding at least some of what we were saying, and it’s upsetting him. – Corey’s Father

It was apparent through interviews that children and youth with SMCI were at risk of encountering difficult events such as medical procedures. Further, because children and youth with SMCI may have friends with similar health concerns or may be patients at palliative care centers they were at an increased risk to losing friends. The conversations around these events and topics are essential to consider regarding how they are explained to children and youth.

Theme 8: Indicators of Expression

The theme indicators of expression encompassed narratives related to any signal or sign that communicated the emotional state, need, desires, self-knowledge, or physiological state of children and youth. The subtheme ‘Body response’ involved reference to physical body movement including the use of eye movement, facial expressions, limb-movement, sounds, laughter, tears, or whole-body reactions. A list of underlying codes describing specific indicators of expression are provided in Appendix E. A primary guardian described her son’s very specific tongue movements that were used as an indicator of expression.

The subtheme ‘Physiological changes’ was described by primary guardians and familiar people as the cues lending insight about changes in body physiology, such as heart rate, body temperature, blood pressure, etc. All narratives about physiological changes involved participants intentionally initiating expression. George’s Mother described his “ninja power,” which consisted of his ability to intentionally raise his heart rate monitor as a method of calling you from another room (i.e., indicate distress although not actually being in distress, triggering an alarm on his system), and lower it seconds later once they walked into the room.

Indicators of expression varied across participants and were impacted by motor/physical abilities. Participants developed their own way to provide cues to primary guardians and familiar people, for their expression to be received. All participants expressed smiles, which informants explained as identifiable by unfamiliar people.

Theme 9: Detectors, Interpreters, and Enablers

‘Detectors, interpreters, and enablers’ described the people, communication aids, or a combined use of people and communication aids that can detect a range of indicators of expression from simple to complex with varying levels of competence. Communication aids are devices that provide aided augmentative and alternative communication (AAC); which supports participant expression in being detected and interpreted.Citation2 Unaided AAC (such as gestures and eye gaze) were encompassed within the theme indicators of expression.Citation2 Primary guardians and familiar people learned to detect and interpret participants with both aided and unaided AAC. The subtheme ‘Insight or clues from people close to child/youth’ explained the specific knowledge that familiar people have learned, which influences their ability to distinguish child/youth emotional expression. Familiar people described communication signals and specific behaviors that could be translated to others who would otherwise be unaware of their meaning.

‘Um, he has like a really specific one is the way he says no. He brings his right hand up to his right ear and that means no.’ – Reid’s Sibling

Narratives encompassed topics related to ‘parent knows best,’ differentiating expression, and degree of certainty. Primary guardians articulated an intuition, or sixth sense; familiar people described primary guardians as being the best at interpreting participants. Differentiating expressions or emotions were described as how to decipher between different cues or states, whereas ‘degree of certainty’ may also have involved the presence or lack of certainty about the meaning underlying an expression. The subtheme ‘Skills or traits of interpreter’ described personal qualities that are influential to understanding expression of children and youth with SMCI. Qualities included patience, dedication, prolonged exposure (time), and encouragement toward children and youth. Familiar people explained their expertise developing over time; attributed to prolonged exposure and patience.

The subtheme ‘Communication aids used’ involved narratives about high-, low-, or no-technology aids used to distinguish emotions or expressions directly from participants. Some participants used their communication aids autonomously, while others required communication partners to access aided AAC and enable expression. For example, familiar partners were required to set-up low-tech and high-tech systems for participant use. The majority of participants primarily used unaided AAC (i.e., gestures, communication signals), however, some participants also used multimodal AAC; facial expressions (unaided AAC) and a small yes/no board (aided AAC).

Communication aids were most beneficial when supported by primary guardians or familiar people. Co-construction of meaning occurred; primary guardians or familiar people co-constructed a participant’s intended meaning of expression.Citation2,Citation107 This primarily occurred within participation of educational learning. Encouragement and dedication from primary guardians and familiar people were articulated as essential for effective expression when using communication aids.

‘She just needs the support of an attentive communication partner and help to navigate the computer technology.’ – Suzie’s Mother

Insight from primary guardians and familiar people was found to be important in understanding emotional experiences. Primary guardians and familiar people were able to decipher between expressions and emotions across different environments and inform novel care providers. The use of high technology aided AAC devices was rarely described to understand emotional expression. No photos/videos depicted emotions through communication aids; body cues and insight from people close to the child remain as the most authentic approach to understanding the emotions of children and youth with SMCI.Citation108

Discussion

The findings from this study enabled the development of a conceptual understanding of emotional well-being specific to children and youth with SMCI. The need for a high-quality interpreter was identified as an essential component of understanding the emotional well-being of children and youth with SMCI relative to others.Citation34,Citation35 An interpreter’s understanding of the symbols and cues of the child/youth can enable reciprocal interaction. As well, without a skilled interpreter children and youth with SMCI, are unable to share their preferences and needs.Citation109 As such, familiar people in the lives of children and youth might be unable to react to the emotions of children and youth or modify undesirable circumstances in response. Further, it has been found that parents’ positive reactions to their child’s emotions can influence a child’s ability to be emotionally well regulated and responsive to themselves and others.Citation110–112 In the context of this research, all participants had informants who understood their indicators of expression and provided insight about emotional experiences. In the absence of a skilled interpreter children and youth would be limited in their abilities to try new experiences, participate in preferred opportunities, and develop emotionally.Citation2 Therefore, further research is necessary to study the impact of the absence of a skilled interpreter on emotional well-being for children and youth with SMCI. Identifying approaches used by high-quality interpreters to understand experiences of children and youth with SMCI may be useful for other familiar people and primary guardians to learn from and better understand children/youth with SMCI without a skilled interpreter.

The importance of interpersonal interaction to emotional well-being for children and youth with SMCI, is not diminished by an inability to communicate by traditional means. Pediatric mental health assessment measures do not capture items related to the presence of interpersonal interaction.Citation113–121 Interpersonal interactions are de-emphasized in mental health assessments and interventions,Citation115,Citation116,Citation119,Citation120,Citation122–124 but play a crucial role in relation to emotional well-being as evidenced here specifically for children and youth with SMCI, but also in the broader literature.Citation39,Citation77,Citation125–130 Positive social relationships and daily interpersonal interaction are vital for positive well-being within pediatric and adult populations.Citation39,Citation77,Citation125–130 Other research has provided evidence to support the impact of interpersonal interaction with people on the periphery of our close networks, contributing to positive emotional well-being.Citation131 Greater positive affect has been reported by individuals after interpersonal interaction with a coffee shop baristaCitation132 and after receiving friendly eye contact from unfamiliar passersby.Citation133 Interpersonal interaction specifically has been minimally explored in mental health research for children with disabilities; studies have focused on the promotion of social interaction skills within school settings.Citation134–136 There is a gap in the literature and healthcare system regarding mental health service initiatives for children and youth with SMCI whose interactions may not benefit from social skill-based interventions and/or do not attend school. Presence of interpersonal interaction is one component of emotional well-being that should be assessed by mental health professionals for children and youth with SMCI.

Without researchers, clinicians, and familiar people seeking to understand the personality traits and preferences of children and youth with SMCI, involvement in preferred activities and engagements meaningful to children and youth might be overlooked. Previous research exploring leisure activity preferences identified incongruities between participant preferences and actual activity involvement.Citation45,Citation137 Short of effective interpretation of child/youth preferences, it may be assumed that children and youth are unable to participate, but in reality, lack of participation may be attributed to the activity being unpreferred. Previous research provides evidence of including insight of child-parent temperament as a predictor of child mental healthCitation138–141; understanding specific personality traits of children/youth with SMCI and their primary guardians may therefore aid our understanding of child/youth emotional well-being. In our study, primary guardians and familiar people described participant characteristics that involved positioning preferences (i.e. seated versus standing), personality traits (e.g. funny and caring), music preference, and favored activities; findings emphasized the positive characteristics of children and youth with SMCI which are minimally highlighted in earlier literature.Citation142 Additionally, informants in our study explored the personality traits and preferences of participants by trying ‘new experiences.’ Understanding preferences of children and youth can also enable the promotion of child-centered therapeutic approaches.Citation137 It is vital to understand the preferences and personalities of children and youth to appropriately promote opportunities of enjoyment/desire and care that contribute to accurately ascertaining emotional well-being.

Patterns and combinations of indicators of expression (e.g., body positions, vocalizations, and facial expressions) in our study were unique to each child; with the exception of self-expression using eyes. Based on our findings, although all participants used their eyes for expressive communication, this was not limited to ‘eye-gaze’ movements. Indicators of expression using participant’s eyes involved the following: eye-gaze, movement, glimmer, tightness, changes, ‘specific look,’ opening/closing, eye focus, etc. There is an abundance of examples found in the literature of how children and youth with SMCI have self-expressed subjective informationCitation70,Citation143–145 (i.e. narratives and emotional experiences). Further, self-expression of subjective information has been achieved through the use of eye gaze assistive technology. Citation2,Citation146–151 However, a systematic review conducted by Perfect et al. (2020) found that there are often more barriers than facilitators of implementing eye-gaze assistive technology use in daily life for children and youth with complex disabilities.Citation152 Barriers of technology device uptake involve personal (e.g. fatigue related to device use) and environmental (e.g. funding resources) factors.Citation153 Further investigation on self-expression of eyes, beyond the eye-gaze-based systems currently available, may be appropriate to understand the emotional experiences of children and youth with SMCI. Insight from familiar people who know the signs and behaviors of children and youth with SMCI can be used to inform engineers and AAC specialists to develop practical aids to enhance self-expression in daily life.Citation1–3,Citation154,Citation155

Research involving children and youth with SMCI has focused on physical health and medical interventions,Citation156,Citation157 with minimal research and practical assessments having addressed emotional well-being.Citation70,Citation115,Citation158 In addition to adequate medical care,Citation159 conversations about emotions and emotional well-being are essential to discuss with children and youth with SMCI.Citation108 Our research identified child/youth experiences of emergency medical visits and death of friends, which can be traumatic for children and youth, therefore conversations about emotions are essential. Minimal research has been conducted in regard to psychological therapy techniques for individuals with severe motor and communication impairment.Citation160,Citation161 However, there is evidence of unique arts-based therapy techniques for individuals with disabilities that may be beneficial for children and youth with SMCI.Citation160,Citation161 Drama therapy involving sensory play, body games, sounds, stories, and role playing has provided positive social and emotional outcomes for children with severe intellectual developmental disability.Citation161 Psychotherapy for adults with severe ASD or mental disability have involved music-based approaches that enable patients to explore interpersonal interaction and emotional needs.Citation160 Another study presents how parent–child dyads discuss post-hospital visits related due to physical trauma within daily life, which brought up discussion of emotions.Citation162 It is critical for future research to explore how we can better approach emotional discussions within clinical practice and everyday life for children and youth with SMCI.Citation163–165

Although a combined assessment of emotional well-being across all domains of our conceptualization cannot be applied, narratives from this research highlighted an overall depiction of the ‘good life’ experienced by children and youth with SMCI. Primary guardians shared the closeness of their families, the rewarding experiences of connecting with specific support workers, and taking the time to appreciate their lives. This work has provided one more piece of research that shows a roadmap to understand emotional well-being for children and youth with SMCI, rather than a way to fix pathology. Primary guardians and familiar people expressed immense joy because of their connection to children and youth within the study. In addition to research on medical complexity/physical impairments and improving quality of life, the positive lives of children and youth with SMCI and their families need to be emphasized. Further research is suggested to continue exploring the under-researched themes within our conceptual understanding of emotional well-being.

Limitations

Selection bias may have been introduced in this study, the full representation of children and youth with SMCI could not be achieved on some key demographic characteristics.Citation66,Citation166 It cannot be assumed that all families of children and youth with SMCI have access to social media platforms, however our recruitment for the study only involved advertising on social media. As such, children, youth, and families may have been missed who do not have access to technology and Wi-fi/internet connection which were required to be recruited and involved in the project. Another limitation to the study was introduced because of the COVID-19 pandemic which impacted the primary researcher-participant rapport, diversity of photo/video data, and overall emotional variability of participants. The primary researcher was unable to meet children, youth, and families in-person which may have limited the rapport created prior to conducting qualitative interviews; subsequently, this may have impacted the depth of qualitative interviews. Children and youth were limited by their participation in activities and programs outside of the home due to COVID-19 school and program closures. As a result, visual data collected was mostly captured within the home and primary guardians reported participants experienced more negative emotional states because of reduced interpersonal/social interactions. This project did not explicitly consider cognition or the influence of acquired versus congenital impairments on emotional well-being.

Future Directions

This research has the potential to further the development of an outcome measure specific for the emotional well-being of children and youth with SMCI. The domains and themes embedded within the conceptualization of emotional well-being can be validated in future studies to develop a measure that effectively captures the aspects of emotional well-being for children and youth with SMCI that are important to them. As such, the measure could be used via existing approaches to enable self-expression. Clinical professionals (such as occupational therapists) can continue to work with children and youth to explore possible means of gaining a confirm/deny response using no-tech/low-tech approaches, while incorporating questions, which focus on emotional well-being. For example, a picture board or visual displaysCitation167–170 could be used in which children and youth respond (using individualized means of confirm/deny response) to questions based on components identified within the conceptualization of emotional well-being.Citation2

The conceptualization highlights the need to understand the personality traits and preferences of children and youth with SMCI to help tailor opportunities that can enhance meaning in the daily lives of children and youth with SMCI.Citation45,Citation137 By using familiar person’s insight regarding the personality traits and preferences of children and youth, one can more appropriately inform client-centered care.Citation137,Citation171 For example, interventions can be used that integrate the preferences of children and youth such as implementing preferred play to encourage participation or social interaction.Citation172

Conclusions

This work sought to describe the emotional well-being of children and youth with SMCI. The research attempted to grasp the experiences of children and youth who are unable to provide narratives about their emotional well-being, through the use of visual data and triangulated primary guardian and familiar person knowledge. The authors’ conceptual understanding of emotional well-being illustrates indicators and components of emotional well-being through four main domains, which encompass relevant themes and subthemes. The indicators of emotional well-being, which emerged from our findings highlight the diversity of self-expression of children and youth, while also reflecting the necessity of high-quality interpreters. Components of emotional well-being were established, which highlight similarities to typically developing populations and unique components specific to children and youth with SMCI. Visual data and insights from primary guardians and familiar people contributed to the understanding of emotional experiences across different relationships and contexts. The findings highlight the necessity of incorporating insight from familiar people in assessing emotional well-being. Further, the knowledge gained from this research can help unfamiliar people begin to understand the complexity of emotional experiences and self-expression for children and youth with SMCI.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the members of The Everything that Counts Research Lab, The Building and Designing Assistive Technology (BDAT) Lab, and the primary author’s institution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sigafoos J, Woodyatt G, Keen D, Tait K, Tucker M, Roberts-Pennell D, Pittendreigh N. Identifying potential communicative acts in children with developmental and physical disabilities. Commun Disord Q. 2000;21(2):77–86. doi:10.1177/152574010002100202.

- Beukelman DR, Mirenda P. Augmentative and alternative communication. third edit. Baltimore, Maryland: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.; 2005.

- Mirenda P. Toward functional augmentative and alternative communincation for students with autism: manual signs, graphic symbols, and voice output communication aids. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2003;34(1):201–16. doi:10.1080/14417040510001669091.

- Statistics Canada. Participation and activity limitation survey. 2006.

- Van Der Meijden A, Cox A, Murray B, Kealy A. Students with disabilities in Dutch VET. Amsterdam, Netherlands; 2015.

- Australia’s children. Canberra; 2020.

- Roche L. Evaluating and enhancing communication skills in four adolescents with profound and multiple disabilities. 2017.

- Lyons G, De Bortoli T, Arthur-Kelly M. Triangulated proxy reporting: a technique for improving how communication partners come to know people with severe cognitive impairment. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(18):1814–20. doi:10.1080/09638288.2016.1211759.