ABSTRACT

Following Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez’ [(2009). Green advertising revisited. Conditioning virtual nature experiences. International Journal of Advertising, 28(4), 715–739] approach, this experimental study compares the effects of three types of green print ads: a non-green ad, a functional green ad promoting environmental product attributes, and a combined nature ad featuring a pleasant nature image in addition to functional attributes. We extend prior research by simultaneously testing moderating and mediating mechanisms to explain brand attitudes and purchase intention. Using a quota sample of 456 consumers, findings suggest that the functional ad enhances perceptions of environmental brand benefits, which positively affect purchase intention partially mediated by brand attitudes. The combined nature ad, by contrast, activates an additional emotional process of virtually experiencing nature which positively influences brand attitudes and purchase intention beyond perceptions of environmental brand benefits. The effects of the combined nature ad are even stronger for highly involved consumers.

The increasing environmental concern of consumers around the globe has spurred the growth of a market for green products. Consequently, green advertising has grown exponentially in the past two decades (Atkinson & Kim, Citation2015; Futerra, Citation2008). Advertising plays a critical role in communicating companies’ and organizations’ pro-environmental images and promoting environmentally friendly product attributes (Leonidou, Leonidou, Palihawadana, & Hultman, Citation2011). So-called green ads use various appeals to persuade consumers to buy products designed to be less harmful to the environment (Schuhwerk & Lefkoff-Hagius, Citation1995). Research has identified three major advertising appeals: (1) functional or fact-based appeals; (2) emotional or image-based appeals; and (3) a combination of the previous two types of appeals (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2009; Hartmann, Apaolaza-Ibáñez, & Sainz, Citation2005; Matthes, Wonneberger, & Schmuck, Citation2014).

Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2012) have conducted a series of studies to understand the specific effects of these appeals in green advertising, which provided important insights into the attitudinal outcomes and mediators of green advertising appeals. Yet, there are three aspects that require further investigation. First, a wealth of research suggests that environmental involvement plays an important role for brand attitudes and purchase intentions of green products (e.g. Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008, Citation2012; Mohr, Eroǧlu, & Ellen, Citation1998). Yet, even though the Elaboration-Likelihood Model (ELM; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986) predicts that involvement plays a crucial role in processing advertising messages, only few studies have experimentally tested how environmental involvement moderates the effects of different green ads on consumers’ responses (see Bickart & Ruth, Citation2012; Matthes et al., Citation2014; Schuhwerk & Lefkoff-Hagius, Citation1995). More importantly, there can be several facets of environmental involvement, such as environmental concern, green product attitudes, or green purchase behaviour (Matthes et al., Citation2014). All three are included in the present study. Second, previous research has established important mediators in the process of green advertising effects such as perceived utilitarian environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experiences (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008, Citation2009). However, studies have either investigated the moderators (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008; Matthes et al., Citation2014) or the mediators (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2009) of green advertising effects, but no experimental study has simultaneously tested both, the conditions and the underlying processes of the effects of different green ad appeals on consumers’ attitudinal outcomes.

Third, numerous earlier studies relied on student or convenience samples (e.g. Grimmer & Woolley, Citation2014; Hartmann et al., Citation2005; Schuhwerk & Lefkoff-Hagius, Citation1995; Searles, Citation2010; Spack, Board, Crighton, Kostka, & Ivory, Citation2012). Green consumerism, however, significantly varies by age, education, and gender (Atkinson & Kim, Citation2015; Roberts, Citation1996; Shrum, McCarty, & Lowrey, Citation1995), so student samples lack population validity and are of limited use when investigating the effects of green advertisements.

Thus, the present study follows Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2009) experimental approach to investigate the effects of different green ad appeals on brand attitude and purchase intention. Furthermore, it extends this research by proposing a moderated mediation model that simultaneously examines the mediating processes of green ad effects, such as utilitarian environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experiences, and the moderating roles of several interrelated green involvement dimensions.

Green advertising appeals

Definitions of green advertising are not straightforward. According to Banerjee, Gulas, and Iyer (Citation1995), green ads address the relationship between a product or service and the natural environment, advocate an environmentally responsible lifestyle, and highlight a corporate environmental image or responsibility. Especially in the early stage of green advertising, companies quickly issued green claims that sometimes included deceptive or confusing truths or even false promises. These misleading or exaggerated appeals are called “greenwashing” (Baum, Citation2012; Plec & Pettenger, Citation2012). In many countries, consumers have become increasingly sceptical of the credibility of green advertising. Against this background, many companies are inclined to apply more substantial and less deceptive green claims, which points to “a more responsible approach to green advertising” (Leonidou et al., Citation2011, p. 24). For the purposes of this study, green ads refer to all advertisements that promote environmental sustainability or convey ecological or nature-friendly messages that target the needs of environmentally concerned customers, regulators, and other stakeholders (Leonidou et al., Citation2011; Zinkhan & Carlson, Citation1995).

Generally, three main strategies are used in green advertising: functional fact-based appeals; image-based emotional appeals; or, most frequently, a combination of both. A functional positioning strategy highlights the relevant utilitarian attributes of a product compared to conventional competing products (Hartmann et al., Citation2005). Studies confirm that pointing out the environmentally friendly attributes of products can affect brand attitudes (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008; Matthes et al., Citation2014).

The aim of an emotional positioning appeal is to transfer affective responses to the brand (Searles, Citation2010). Emotional appeals are image related and usually depict pleasant nature scenery, which might evoke positive affective responses because of the virtual contact with real-world nature (Hartmann, Apaolaza, & Alija, Citation2013; Kaplan, Citation1995). Several studies have demonstrated significant positive attitudinal effects from emotional appeals in green advertising (Hartmann et al., Citation2005; Matthes et al., Citation2014; Searles, Citation2010).

Finally, a mixed-type positioning strategy combines functional and emotional appeals. Previous research suggests that this green advertising strategy can achieve the highest attitudinal effects (Hartmann et al., Citation2005; Matthes et al., Citation2014). Research by Hartmann et al. (Citation2005) and Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2009, Citation2012) has identified distinct functional and emotional dimensions of attitude formation responding to green advertisements. In assessing consumer attitudes evoked by an advertisement, it is important to distinguish between cognitive evaluations and affective responses (see also Madden, Allen, & Twible, Citation1988). Cognitive evaluations of green ads entail judgement of whether a brand has environmentally sound product attributes, while affective responses are feelings experienced in response to an ad (Searles, Citation2010). Both the cognitive judgements and the feelings evoked by an ad have been shown to affect consumers’ evaluation of the brand (Hartmann et al., Citation2005) and pro-environmental intentions (Hartmann, Apaolaza, D’Souza, Barrutia, & Echebarria, Citation2014).

Utilitarian environmental benefits

The consumption of products with environmentally sound attributes (e.g. reduced emissions, recyclable materials) offers additional benefits for consumers than the purchase of conventional products (Roberts, Citation1996). Information regarding environmental brand benefits can be provided through persuasive arguments describing a product’s relevant environmental advantages (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2009; Matthes et al., Citation2014) or through verification seals that refer to a product’s environmental performance or characteristics such as recyclable materials (Bickart & Ruth, Citation2012). Studies show that providing information about ecological product attributes in advertisements can increase the perception of environmental brand benefits (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2009), which can enhance brand attitudes (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008, Citation2009) and purchase intention (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2012; Roberts, Citation1996). Drawing from these findings, we hypothesize that, compared to a conventional ad, a functional green ad, which emphasizes a product’s environmental attributes, increases the perception of utilitarian environmental brand benefits and, thus, the intention to purchase the product advertised.

H1a: Green advertisements featuring environmental brand attributes enhance the perception of utilitarian environmental brand benefits.

H1b: Perceived utilitarian environmental brand benefits positively influence purchase intention.

In addition to direct effects on purchase intention, Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2012) found that brand attitude partially mediates the effects of utilitarian environmental brand benefits on purchase intention. Based on their findings, we expect that brand attitudes will partially mediate the effect of utilitarian environmental brand benefits on purchase intention.

H1c: Brand attitudes partially mediate the effect of a brand’s utilitarian environmental benefits on purchase intention.

Virtual nature experiences

Visual representations of nature are prominent in many green advertisements. The ecological attributes of a product or brand are often communicated through backgrounds representing pristine, unspoiled landscapes to evoke the beauty of nature (Hartmann et al., Citation2013; Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2009). These nature images may activate feelings similar to those experienced in actual contact with nature termed “virtual nature experiences” by Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2008, p. 821). Hartmann et al. (Citation2013) found that the emotion ratings from study participants exposed to advertisements with pleasant nature imageries did not significantly differ from the emotional responses to real nature of participants not exposed to any advertisements. These virtual nature experience can be explained by a general human need for contact with nature (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008).

If emotional responses to nature imagery are positive, their transfer to brand attitude should be favourable as well. It has been shown that nature imagery in green ads can evoke positive emotional responses, which positively influence the formation of brand attitudes (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2012) and purchase intention (Allen, Machleit, & Kleine, Citation1992). Hence, we expect that the effects of virtually experiencing nature directly influence purchase intention partially mediated by brand attitude.

H2a: Green advertisements featuring pleasant nature imagery, in addition to environmental brand attributes, enhance the perceived virtual nature experience.

H2b: The perceived virtual nature experience positively influences purchase intention.

H2c: Brand attitudes partially mediate the effect of perceived virtual nature experience on purchase intention.

Exposure to nature images can also exert positive cognitive influences (Hartmann et al., Citation2013) and, according to attention restoration theory, improve attention and memory (Kaplan, Citation1995). Exposure to pictures of natural landscapes in advertising might have the same effects (Hartmann et al., Citation2013). In an eye-tracking study, Hartmann et al. (Citation2013) found that, compared to other images, nature images resulted in significantly higher attention directed toward the advertising message. Therefore, we suggest that a green ad featuring pleasant nature imagery and environmental brand attributes not only enhances the perceived virtual nature experience, but also draws more attention to the environmental attributes of the brand. As expected in the first hypothesis, greater perception of utilitarian environmental brand benefits, in turn, positively influences purchase intention, partially mediated by brand attitude.

H3: Green advertisements featuring pleasant nature imagery and environmental brand attributes increase the perception of utilitarian environmental brand benefits.

As posited in H1b and H1c, such perceived utilitarian benefits directly and indirectly (i.e. via attitude toward the brand) affect purchase intention.

Environmental involvement

Consumers have different knowledge of and commitment to the environment. In this context, three categorizations of environmental involvement need to be distinguished (for a discussion, see Matthes et al., Citation2014; Naderer, Schmuck, & Matthes, Citation2017). One conceptualization is environmental concern, which can be described as awareness of environmental problems and perception of the necessity to protect the environment (Schwartz & Miller, Citation1991). Second, scholars have conceptualized green involvement as a general positive attitude toward green products (e.g. Roberts, Citation1996). A third definition of highly involved green consumers relies on their self-reported green purchase behaviour (Chang, Citation2011; Mohr et al., Citation1998; Shrum et al., Citation1995). These three dimensions of environmental involvement are related but have different antecedents and outcomes. Therefore, all three need to be taken into account when investigating the moderating effect of involvement on green advertising effectiveness (Matthes et al., Citation2014).

The ELM (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986) suggests that involvement is a crucial factor in individuals’ motivation to process incoming information. Based on the amount of cognitive elaboration, attitude formation toward a brand or a product takes place through either central or peripheral persuasion processes. Depending on the consumer’s environmental involvement level, the attitudinal effects of perceived product attributes and emotional experiences, therefore, are expected to vary (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008).

To date, few studies have focused on the moderating role of environmental involvement in consumers’ responses to green ads (but see Bickart & Ruth, Citation2012; Matthes et al., Citation2014; Schuhwerk & Lefkoff-Hagius, Citation1995). Matthes et al. (Citation2014) systematically investigated the effects of three types of green ads: a functional ad highlighting environmentally sound product attributes, an emotional ad featuring pleasant nature imagery, and a combination of the two types. The emotional and mixed-type ads significantly increased brand attitude, regardless of the environmental involvement level. Involvement moderated the effect only when the ad contained argumentative product appeals but not nature images. According to the ELM, these ads, which required a higher amount of cognitive elaboration, were persuasive only to those highly involved with the environment.

Schuhwerk and Lefkoff-Hagius (Citation1995) on the other hand found that green advertising appeals may be especially persuasive for individuals who do not usually buy green products or express environmental concern whereas higher involved individuals were intrinsically alert to environmental attributes of products and expressed high purchase intention for the green product regardless of the ad appeal (Schuhwerk & Lefkoff-Hagius, Citation1995).

However, although these studies provided useful insights into the moderating role of environmental involvement, they did not examine processes that might mediate the effects of different ad appeals on brand attitude or purchase intention.

So far, only the study by Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2008) examined the interaction of environmental involvement and cognitive and affective processes such as perceived environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experiences. Their findings revealed that environmental involvement moderated the degree to which virtual nature experiences and environmental brand benefits influenced brand attitudes. However, this study did not experimentally test the effects of different green ad appeals and it did not take into account whether environmental involvement contributes to the formation of virtual nature experience and perceived environmental brand benefits. Although these processes have been found to significantly impact brand evaluations (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008, Citation2009), research lacks an investigation of how they are formed. Given the important role of environmental involvement in the processing of green advertising, we assume that it also contributes to the formation of perceived environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experiences in response to green ad appeals. However, since this moderated mediation has not been demonstrated before, we formulate a research question:

RQ1: How does environmental involvement moderate the effects of green advertisements on individuals’ perceived utilitarian environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experiences?

Additionally, we investigate which dimensions of green involvement, used in earlier research, exert the strongest moderating influence on perceived environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experiences. The dimensions of green involvement usually are highly correlated, so we again formulate a research question, rather than specific hypotheses.

RQ2: Which dimension of green involvement—environmental concern, attitudes toward green products, or green purchase behaviour—most strongly moderates the effects of different green ad appeals?

The full theoretical model showing all hypotheses is depicted in .Footnote1

Method

The present study employed a one-factorial between-subjects design manipulating the ad’s visual and textual layout. Following previous studies in this field (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2009; Hartmann et al., Citation2005, Citation2013), we established three conditions: a control condition, a functional ad condition, and a combined nature ad condition featuring both pleasant nature imagery and functional attributes. The three dimensions of involvement were measured before ad exposure and treated as continuous moderators.

Stimulus

Based on Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez' study (Citation2009), the present study used three versions of a print ad for a cell phone under the fictitious brand Eagle Mobile (see Appendix). Participants in the control condition saw the cell phone and the brand name in front of a blank background. In the functional ad condition, participants were shown an ad presenting a slogan, the product, and an environmental brand attribute (sustainability eco-seal). In the combined nature ad condition, participants saw an ad presenting the same product, environmental brand attribute, slogan, and pleasant nature imagery. Following previous studies (Hartmann et al., Citation2005; Matthes et al., Citation2014), the image showed a lake surrounded by mountains and forests.

Participants

As argued by Shrum et al. (Citation1995) and others, green consumerism varies significantly by age, education, and gender; therefore, student samples lack population validity. Thus, a quota sample was obtained from Austrian consumers ages 16–88 for a survey conducted from December 2012 to February 2013. The quota was based on the demographic characteristics of the general public in Austria, specifically age (M = 45.1, SD = 17.7), gender (53% female), and education level (18.5% compulsory schooling, 58.0% completed apprenticeship, 13.8% qualification for university entrance, 9.7% college degree). Compared to the actual population distribution, participants with compulsory school level were slightly underrepresented and participants who completed apprenticeship were slightly overrepresented in the sample. The participants’ recruitment was based on a quota plan. The study was part of an advanced research class. Students helped to recruit the sample. The survey was conducted both online and in paper to reach older participants. The survey mode was included as a control variable in every statistical analysis. One hundred and thirty-one participants filled out paper and pencil questionnaires and 325 participated online. In total, 1005 participants were contacted, 248 refused to participate and 301 were screened out because their quota was already fulfilled, resulting in a total sample of N = 456.

Measures

This survey was part of a larger study. Only measurements relevant to the topic discussed in the paper are presented here. The full questionnaire is available from the authors upon request. Assignment to one of the three conditions was the independent measure in our design. To model the experimental conditions in path analysis, two dummy coded variables were created.

All survey items are listed in the appendix. Five items employing a 7-point semantic differential scale assessed attitude toward the brand (Cronbach’s α = .94; M = 4.08; SD = 1.39). Purchase intention was measured by a single 7-point scale item (M = 2.4; SD = 1.6). All items used to create the moderator and mediator variables were tested on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree.” The three dimensions of green involvement were measured as moderators of our model and were captured before ad exposure. Environmental concern was measured through four items based on Schuhwerk and Lefkoff-Hagius (Citation1995) (Cronbach’s α = .77; M = 5.19; SD = 1.3); attitude toward green products through four items based on Chang (Citation2011) (Cronbach’s α = .84; M = 5.05; SD = 1.36); and green purchase behaviour through six items based on Kim and Choi (Citation2005) (Cronbach’s α = .86; M = 4.76; SD = 1.33). For the mediator variables, we developed two items assessing perception of utilitarian environmental brand benefits (Cronbach’s α = .92; M = 2.78; SD = 1.73) and two items for virtual nature experience (Cronbach’s α = .84; M = 2.40, SD = 1.6). Both measures are based on Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2012).

Perceived consumer effectiveness, a key variable in green advertising (Ellen, Wiener, & Cobb-Walgren, Citation1991; Kim & Choi, Citation2005), was included as a control variable and was assessed with three items based on Ellen et al. (Citation1991) (Cronbach’s α = .79; M = 3.25, SD = 1.77).

Randomization check

Participants were equally distributed among the three conditions (33.1% control condition, 31.6% functional ad condition, and 35.3% combined nature ad condition). A randomization check for age, gender, and education level was successful.

Data analysis

We conducted path analyses to test our assumptions. To evaluate the model fit, the following criteria were used: comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and a test of close fit (PCLOSE). The experimental conditions were dummy coded, using the control group as the reference group. The interaction effects were modelled by including multiplicative terms of condition and moderator. The interaction terms were mean centred. The covariates of age, gender, education, perceived consumer effectiveness and survey mode (71% online) were included in all analyses. Despite the random assignment, the inclusion of covariates in the regression model results in more precise inferences if they are predictive of the potential outcomes (Imbens & Rubin, Citation2015).

Results

For each dimension of involvement—environmental concern, attitude toward green products, and green purchase behaviour—we performed a separate path analysis. Our tested hypotheses are listed according to their position in the tested process model.

First, we tested the main effects of functional and nature ad appeals and the moderating role of environmental concern on the outcome variables (see ). The model fit was excellent (CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = .05; PCLOSE = .49). Supporting both H1a and H3, we found significant main effects from both the functional (b = 0.64; p = .001) and the combined nature ads (b = 0.91; p < .001) on perceived environmental brand benefits. Virtual experiences of nature, as expected, were influenced only by the combined nature ad (b = 1.37, p < .001), supporting H2a. The functional ad had no effect on virtual nature experiences (b = 0.05, n.s.).

Table 1. Path analysis for environmental concern as moderator, unstandardized path coefficients.

RQ1 asked how environmental involvement moderates the perception of utilitarian environmental brand benefits and the virtual experience of nature in different green ad appeals. We found that, in the functional ad condition, the ad–environmental concern interaction did not influence perceived environmental brand benefits (b = 0.08, n.s.). As expected, because no nature image was present, the interaction term also had no influence on the virtual experience of nature (b = 0.11, n.s.).

However, we found a significant positive impact of the interaction between exposure to the combined nature ad and environmental concern on environmental brand benefits (b = 0.37, p < .05) and virtual nature experiences (b = 0.32, p < .05). The positive sign of this interaction indicates that, as levels of environmental concern increase, perceptions of utilitarian environmental brand benefits and virtual experiences of nature in the combined nature ad do as well.

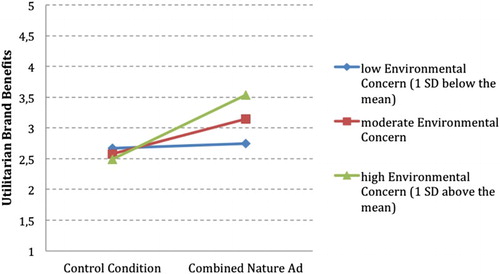

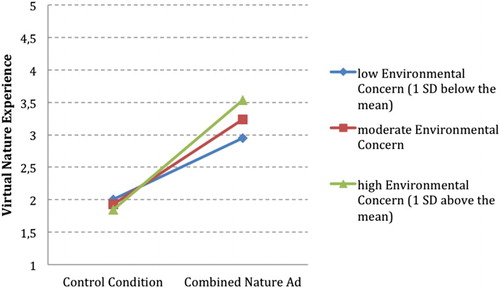

To further analyse this interaction, the effect of the combined nature ad at all levels of environmental concern (i.e. not by splitting the sample) was investigated (see Hayes & Matthes, Citation2009). For low and moderate levels of environmental concern (below 4.7 on a 7-point scale), the combined ad had no significant influence on utilitarian environmental brand benefits compared to the control group, while above 4.7, the effect was significant (ranging from b = 0.36, p < .05 to b = 1.24, p < .001). The effect is also visualized in for low (1 SD below the mean), moderate, and high (1 SD above the mean) levels of environmental concern. Likewise, there was a significant effect of the combined nature ad on virtual nature experience when environmental concern was above 2.7 on a 7-point scale (ranging from b = 0.61, p < .05 to b = 1.83, p < .001) (see ).

Figure 2. Effects of the combined nature ad on utilitarian environmental brand benefits at low, moderate, and high levels of environmental concern.

Figure 3. Effects of the combined nature ad on virtual nature experiences at low, moderate, and high levels of environmental concern.

As predicted, we found direct effects from utilitarian environmental brand benefits (b = 0.14, p < .01) and virtual nature experiences (b = 0.13, p < .01) on purchase intention, supporting H1b and H2b. Furthermore, we found that utilitarian environmental brand benefits (b = 0.28, p < .001) and virtual nature experiences (b = 0.25, p < .001) positively affected brand attitude, which in turn had a significant positive influence on purchase intention (b = 0.42, p < .001). Thus, H1c and H2c were also supported.

It is important to note that the effects of the combined ad and the functional ad were not significant when treating purchase intention as the dependent variable (not shown in ). When virtual nature experiences and environmental brand benefits were omitted from the model, no significant effects on purchase intention were observed, suggesting that virtual nature experiences and environmental brand benefits function as mediators.

Altogether, we observed an influence of the functional ad on purchase intention by affecting utilitarian benefits, which, in turn, exerted a significant effect on brand attitudes. Thus, the functional ad’s effect on purchase intention was mediated by utilitarian benefits and by brand attitudes. A formal test of the mediation on brand attitudes confirmed our findings using a 95% bias corrected bootstrapping confidence interval with 1000 samples. The effect of the functional ad on brand attitude mediated by utilitarian benefits was significant (b = 0.18, Lower Level Confidence Interval [LLCI] = .014, Upper Level Confidence Interval [ULCI] = .38). However, the effect was not significant with virtual nature experiences as mediator (b = 0.01, LLCI = −.07, ULCI = .09). We also found that the combined nature ad’s effect on brand attitudes was mediated by utilitarian benefits (b = 0.25, LLCI = .14, ULCI = .41). Finally, we tested the conditional indirect effect on brand attitudes using a 95% bias corrected bootstrapping confidence interval. That is, the effect of the combined nature ad on attitude was mediated by virtual nature experiences and moderated by environmental concern (b = 0.07, LLCI = .01, ULCI = .15). And, it was mediated by utilitarian benefits and moderated by environmental concern (b = 0.11, LLCI = .03, ULCI = .20).

Regarding RQ2, we found a similar pattern for the other two dimensions of green involvement. As did environmental concern, the interaction of attitudes toward green products and exposure to the functional ad had no moderating effect on perceived utilitarian environmental brand benefits (b = 0.21; n.s.) and virtual nature experiences (b = 0.05, n.s.) (see ). The same holds true for green purchase behaviour as moderator (see ) (b = 0.09; n.s. resp. b = 0.11, n.s.).

Table 2. Path analysis for attitude toward green products as moderator, unstandardized path coefficients.

Table 3. Path analysis for green purchase behavior as moderator, unstandardized path coefficients.

Similar to environmental concern, attitudes toward green products (b = 0.34; p < .01) and green purchase behaviour (b = 0.34, p < .01) significantly moderated the combined nature ad’s effect on the virtual experience of nature. The conditional indirect effects on brand attitude were significant (attitudes toward green products: b = 0.09, LLCI = .04, ULCI = .18; green purchase behaviour: b = 0.10, LLCI = .04, ULCI = .18). However, the moderating effects on environmental brand benefits were below the conventional level of statistical significance for attitudes toward green products (b = 0.23; p = .09) and green purchase behaviour (b = 0.26, p = .08). Thus, it can be concluded that environmental concern exerted the strongest moderating effects on utilitarian environmental brand benefits, although green product attitudes and green purchasing behaviour followed a similar pattern. However, this conclusion applies only to the combined nature ad. For the functional ad, involvement did not matter at all.

To investigate which appeal exerted the strongest effect on the outcome variables, we conducted additional separate analyses for each appeal. Comparing the explained variance of the functional and the combined appeal, the functional ad appeal accounted for 2.5% of the variance of utilitarian benefits and 5% of perceived nature experience. The combined nature appeal’s sole effect, however, explained 6.3% of the variance of utilitarian benefits and 18.4% of perceived virtual nature experience. Thus, although moderated by environmental involvement, the combined ad appeal proved to be more powerful than the sole functional green appeal.

Among the control variables, we found that age had an overall negative effect on most outcome variables, which can be explained by the presented stimulus: A cellphone might have a greater appeal to younger people compared to older individuals.

Discussion

Following the footsteps of Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2009), this study set out to investigate whether environmental brand benefits and nature imagery in green advertisements affect brand attitude and purchase intention by activating cognitive and affective processes such as perceived utilitarian environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experiences. Additionally, we tested the moderating role of consumers’ environmental involvement by comparing three different facets of environmental involvement that are most relevant in previous literature: environmental concern, attitudes toward green products, and green purchase behaviour (Naderer et al., Citation2017).

Overall, the results corroborate with Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2009) findings that positioning a brand as environmentally friendly increases perceived utilitarian environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experiences which in turn leads to more positive evaluations of the brand. Compared to conventional ads, both types of green ads led to higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions. It is important to note that we found no direct effects of the functional and combined ad on purchase intention, which rules out alternative explanations such as, for instance, the ad’s different designs or attributes associated with the product other than its environmental features.

Regarding the role of environmental involvement, the ELM holds that functional ad appeals should be more persuasive for highly involved individuals more motivated to process complex information. However, connecting the brand with a green eco-seal and a slogan promoting the brand’s greenness increased perceptions of environmental utilitarian brand benefits among all recipients, irrespective of their involvement level. Therefore, contrary to earlier findings (Matthes et al., Citation2014), the effects of the functional environmental ad were independent of environmental concern, attitude toward green products, and green purchase behaviour. However, in contrast to the study by Matthes et al. (Citation2014), which used a variety of detailed environmental arguments in the functional condition, the functional appeal in the present study consisted of a simple claim, specifically a well-known green eco-seal, which did not require high processing motivation or cognitive ability. Instead, the green claim we used can be considered as a heuristic cue because it did not explain environmental attributes in detail. This might explain why consumers high and low in environmental involvement perceived environmental brand benefits to a comparable degree.

With regard to the combined nature ad, however, we found moderation effects of environmental involvement on utilitarian environmental brand benefits and on virtual nature experience, which resulted in higher brand attitudes and purchase intention. In other words, the combined nature ad only increased environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experience when a certain level of involvement was present. When this involvement level was reached, the combined ad’s effects on virtual nature experience and environmental brand benefits were accelerated.

This finding implicates that in particular highly involved consumers—who could be expected to be more critical—were more easily persuaded by the simple presence of a pleasant nature image. However, beautiful visual representations of nature sceneries seem to lever out this critical view. Instead, environmental involvement might be highly correlated with such feelings as loving nature and being one with nature (Hartmann et al., Citation2013; Matthes & Wonneberger, Citation2014). This overall affinity toward nature may form a motivational basis of environmental responsible behaviour (Kals, Schumacher, & Montada, Citation1999) and green ads featuring beautiful nature scenery and environmental brand attributes may trigger these intentions to protect the environment among highly motivated individuals (Hartmann et al., Citation2013; Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2008). This effect, however, is not present for very low levels of involvement. In other words, a minimal level of green involvement is necessary. Furthermore, the effect of the combined ad on purchase intention cannot only be explained by an increased emotional response, such as virtually experiencing nature, but also by the perception of environmental utilitarian brand benefits. Therefore, in addition to affective influences, images of nature in green ads can increase the salience of environmentally friendly product features (Hartmann et al., Citation2013), which may positively influence brand attitudes and purchase intention.

Finally, we found that all three involvement dimensions—attitudes toward green products, green purchase behaviour, and environmental concern—played an important role as a moderator of green advertising effects. Although these facets are related, we found that environmental concern exerted the strongest moderating effects on utilitarian environmental brand benefits, so the three are not entirely similar (see also Matthes et al., Citation2014). Thus, we believe that it is important to take all of them into account when investigating green advertising effects. However, further research is needed to gain a more thorough understanding of the different moderating roles of these three involvement dimensions.

Limitations

The present study has some notable limitations. The first one refers to our experimental conditions. We compared a functional and a combined nature ad (including both nature imagery and functional appeal), using the same conditions and approach as earlier studies on the effects of green ads on environmental brand benefits and virtual nature experiences (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2009). However, we did not have a nature-only condition. Although our study was not intended to systematically investigate the effects of functional and image-based appeals, a nature-only condition would have provided broader insights into the effects of green ads.

Second, we found that brand attitude partially mediated the effects of perceived utilitarian environmental benefits and virtual nature experience on purchase intention. Additionally, we found a direct effect of these two constructs on purchase intention. We do not know whether other factors than brand attitude mediate the effects on purchase intention. It can be speculated that our measure of brand attitudes was too simple and, therefore, could not fully mediate the effect on purchase intention. Other dimensions of brand attitude might play a crucial role in this context. Future research should address other potential mediators. Also, we used an unknown brand which limits generalizability to established brands. We chose to use a fictitious brand to avoid existing associations individuals may have with this brand before the study. This limits the validity of our construct “brand attitude”. However, we think that it was the best way to measure this construct as a mediator in the present study. The practice of using unknown or fictitious brands is quite common in advertising research in general and the measure we used is widespread (e.g. Barone, Taylor, & Urbany, Citation2005). In terms of validity, findings speak to brands that are unknown or brands that are introduced to the market. For such brands, we show how they can be associated with environmental appeals in an ad, and how such appeals speak to consumers. There is a large share of relatively unknown brands out there to which consumers are confronted day by day. Hence, we believe the practice of using unknown brands in advertising research is defensible.

Another drawback concerns the use of only two or three items for some constructs. However, all these items have been validated and are regarded as valid and reliable in a large body of earlier work. Therefore, we do not believe that including more items would change the strong relationships we observed. Also, we used a forced-exposure design which needs to be validated in other settings (see Slater, Citation2016).

Finally, we did not consider long-term effects. Looking at short-term effects does not enable to draw conclusions about the longevity and dynamics of green ads’ attitudinal effects. Future research should encompass long-term effects.

Practical implications

Irrespective of these limitations, our findings have considerable practical implications. Our study suggests that green advertisements are a powerful tool to increase environmental responsible actions such as purchasing products that are less harmful to the environment. The findings reveal that a simple environmental cue, which does not require a high amount of cognitive elaboration, can increase perceived environmental brand benefits irrespective of a consumer’s environmental involvement level. An ad, which combines an environmental brand attribute with pleasant nature imagery, in contrast, activates an additional emotional process, which is comparable to feelings experienced in real nature (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2009). To trigger this emotional process, however, a minimal amount of environmental involvement is required. If this threshold level of involvement level is achieved, a combined ad exerts a strong influence on virtual experiences of nature.

From a consumer protection perspective, this finding points to the risk of distracting consumers from a product’s actual environmental features by employing pleasant nature images in green advertising. Recent studies suggest that nature-evoking elements in advertising may mislead consumers through inducing false perceptions of a brand’s greenness (e.g. Naderer et al., Citation2017; Parguel, Benoît-Moreau, & Russell, Citation2015). Even consumers with high literacy (Parguel et al., Citation2015) or high environmental concern (Matthes et al., Citation2014) do not entirely resist vague or false green claims that promote a brand’s ecological image simply by associating it with pleasant nature imagery. In the present study, the nature image was combined with a well-known credible third-party eco-seal. The mere association of the presented eco-seal with a simple nature image increased attitudinal outcomes, in particular among higher involved consumers. Yet one could expect that consumers high in environmental involvement (i.e. the green experts) are immune against the appeals of nature imagery. This is clearly not the case. Especially the green experts can be persuaded by nature imagery. This finding points to the risk of executing “greenwashing” in green advertising by artificially enhancing a brand’s ecological image through the use of nature images (see Baum, Citation2012; Naderer et al., Citation2017). That is, the impact of weak or vague green arguments may be enhanced by evoking virtual nature experiences. And even highly involved green consumers may not realize it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. In addition, an alternative model following Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez (Citation2008) was calculated. In this model, we entered environmental involvement as moderator of the effects of virtual nature experiences and environmental brand benefits on brand attitude. It is important to note that we did not find a moderating effect of environmental concern and environmental brand benefits (b = 0.02, n.s.) nor of environmental concern and virtual nature experiences (b = −0.012, n.s.) on brand attitude (CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = .07, PCLOSE = .99). However, when purchase intention was the dependent variable, we found a significant interaction effect of environmental concern and environmental brand benefits (b = 0.08, p < .05) but no interaction of environmental concern and virtual nature experiences (b = −0.04, n.s.) (CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, PCLOSE = .92). Thus, we find that higher involved individuals rely more heavily on environmental brand benefits when forming a purchase intention. These results did not differ for green purchase behavior and attitude toward green products as moderators.

References

- Allen, C. T., Machleit, K. A., & Kleine, S. S. (1992). A comparison of attitudes and emotions as predictors of behavior at diverse levels of behavioral experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(4), 493–504. doi: 10.1086/209276

- Atkinson, L., & Kim, Y. (2015). “I drink it anyway and I know I shouldn’t”: Understanding green consumers' positive evaluations of norm-violating non-green products and misleading green advertising. Environmental Communication, 9(1), 37–57. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.932817

- Banerjee, S., Gulas, C. S., & Iyer, E. (1995). Shades of green: A multidimensional analysis of environmental advertising. Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 21–31. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1995.10673473

- Barone, M. J., Taylor, V. A., & Urbany, J. E. (2005). Advertising signaling effects for new brands: The moderating role of perceived brand differences. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 13(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1080/10696679.2005.11658534

- Baum, L. M. (2012). It’s not easy being green … or is it? A content analysis of environmental claims in magazine advertisements from the United States and United Kingdom. Environmental Communication, A Journal of Nature and Culture, 6(4), 423–440. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2012.724022

- Bickart, B. A., & Ruth, J. A. (2012). Green eco-seals and advertising persuasion. Journal of Advertising, 41(4), 51–67. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2012.10672457

- Chang, C. (2011). Feeling ambivalent about going green. Journal of Advertising, 40(4), 19–32. doi: 10.2753/JOA0091-3367400402

- Ellen, P. S., Wiener, J. L., & Cobb-Walgren, C. (1991). The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 10(2), 102–117.

- Futerra. (2008). The greenwash guide. Retrieved October 15, 2014, from http://www.futerra.co.uk/downloads/Greenwash_Guide.pdf

- Grimmer, M., & Woolley, M. (2014). Green marketing messages and consumers’ purchase intentions: Promoting personal versus environmental benefits. Journal of Marketing Communications, 20(4), 231–250. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2012.684065

- Hartmann, P., Apaolaza, V., & Alija, P. (2013). Nature imagery in advertising: Attention restoration and memory effects. International Journal of Advertising, 32(2), 183–210. doi: 10.2501/IJA-32-2-183-210

- Hartmann, P., Apaolaza, V., D'Souza, C., Barrutia, J. M., & Echebarria, C. (2014). Environmental threat appeals in green advertising: The role of fear arousal and coping efficacy. International Journal of Advertising, 33(4), 741–765. doi: 10.2501/IJA-33-4-741-765

- Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. (2008). Virtual nature experiences as emotional benefits in green product consumption. The Moderating Role of Environmental Attitudes: Environment and Behavior, 40(6), 818–842.

- Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. (2009). Green advertising revisited. Conditioning virtual nature experiences. International Journal of Advertising, 28(4), 715–739. doi: 10.2501/S0265048709200837

- Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. (2012). Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1254–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.11.001

- Hartmann, P., Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. A., & Sainz, F. J. F. (2005). Green branding effects on attitude: Functional versus emotional positioning strategies. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 23(1), 9–29. doi: 10.1108/02634500510577447

- Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41(3), 924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924

- Imbens, G. W., & Rubin, D. B. (2015). Causal inference in statistics, social, and biomedical sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kals, E., Schumacher, D., & Montada, L. (1999). Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature. Environment and Behavior, 31(2), 178–202. doi: 10.1177/00139169921972056

- Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. doi: 10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

- Kim, Y., & Choi, S. M. (2005). Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE. Advances in Consumer Research, 32(1), 592–599.

- Leonidou, L. C., Leonidou, C. N., Palihawadana, D., & Hultman, M. (2011). Evaluating the green advertising practices of international firms: A trend analysis. International Marketing Review, 28(1), 6–33. doi: 10.1108/02651331111107080

- Madden, T. J., Allen, C. T., & Twible, J. L. (1988). Attitude toward the ad: An assessment of diverse measurement indices under different processing “sets”. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(3), 242–252. doi: 10.2307/3172527

- Matthes, J., & Wonneberger, A. (2014). The skeptical green consumer revisited: Testing the relationship between green consumerism and skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 115–127. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2013.834804

- Matthes, J., Wonneberger, A., & Schmuck, D. (2014). Consumers’ green involvement and the persuasive effects of emotional versus functional ads. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 1885–1893. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.054

- Mohr, L. A., Eroǧlu, D., & Ellen, P. S. (1998). The development and testing of a measure of skepticism toward environmental claims in marketers’ communications. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 32(1), 30–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.1998.tb00399.x

- Naderer, B., Schmuck, D., & Matthes, J. (2017). Greenwashing: Disinformation through green advertising. In G. Siegert, M. B. Rimscha, S. Grubenmann (Eds.), Commercial communication in the digital age – Information or disinformation? Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Parguel, B., Benoît-Moreau, F., & Russell, C. A. (2015). Can evoking nature in advertising mislead consumers? The power of “executional greenwashing”. International Journal of Advertising, 34(1), 107–134. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2014.996116

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion. New York, NY: Springer.

- Plec, E., & Pettenger, M. (2012). Greenwashing consumption: The didactic framing of ExxonMobil’s energy solutions. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 6(4), 459–476. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2012.720270

- Roberts, J. A. (1996). Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. Journal of Business Research, 36(3), 217–231. doi: 10.1016/0148-2963(95)00150-6

- Schuhwerk, M. E., & Lefkoff-Hagius, R. (1995). Green or non-green? Does type of appeal matter when advertising a green product? Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 45–54. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1995.10673475

- Schwartz, J., & Miller, T. (1991). The earth’s best friends. American Demographics, 13(2), 26–35.

- Searles, K. (2010). Feeling good and doing good for the environment: The use of emotional appeals in pro-environmental public service announcements. Applied Environmental Education and Communication, 9(3), 173–184. doi: 10.1080/1533015X.2010.510025

- Shrum, L. J., McCarty, J. A., & Lowrey, T. M. (1995). Buyer characteristics of the green consumer and their implications for advertising strategy. Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 71–82. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1995.10673477

- Slater, M. D. (2016). Combining content analysis and assessment of exposure through self-report, spatial, or temporal variation in media effects research. Communication Methods and Measures, 10(2-3), 173–175. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2016.1150969

- Spack, J. A., Board, V. E., Crighton, L. M., Kostka, P. M., & Ivory, J. D. (2012). It’s easy being green: The effects of argument and imagery on consumer responses to green product packaging. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 6(4), 441–458. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2012.706231

- Zinkhan, G. M., & Carlson, L. (1995). Green advertising and the reluctant consumer. Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 1–6. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1995.10673471

Appendix

Attitude toward the brand: unattractive–attractive; not likable–likable; negative–positive; boring–interesting; not recommendable–recommendable.

Purchase intention: Would you be interested in buying a product of “Eagle Mobile” in the future? How likely is such a purchase?

Environmental concern: I am concerned about the environment; The condition of the environment affects the quality of my life; I am willing to make sacrifices to protect the environment; My actions impact the environment.

Attitudes toward green products: I like green products; I feel positive toward green products; Green products are good for the environment; I feel proud when I buy/use green products.

Green purchase behavior: I make a special effort to buy products in biodegradable packages; I would switch from my usual brands and buy environmentally safe cleaning products, even if I have to give up some cleaning effectiveness; I have switched products for ecological reasons; When I have a choice between two equal products, I purchase the one less harmful to the environment; I enjoy buying green products; Buying green products is the preferable option.

Utilitarian environmental brand benefits: “Eagle Mobile” respects the environment; A cellphone by “Eagle Mobile” is better for the environment than other cellphone brands.

Virtual nature experience: “Eagle Mobile” makes me feel close to nature; “Eagle Mobile” makes me think of nature, fields, forests and mountains.

Perceived consumer effectiveness: There is not much that any one individual can do about the environment (reversed); The conservation efforts of one person are useless as long as other people refuse to conserve (reversed); The efforts of one individual to protect the environment are hopeless if others reject environmental protection (reversed).