ABSTRACT

To address the global problem of single-use plastic waste, tailored behavior change interventions need to be developed which respond to the way different audiences think and act. The current study adopted a behavior-based segmentation approach, underpinned by the theory of normative social behavior and empirical testing, to better understand plastic consumption and the effect of existing media communications. Using a sample of 1001 respondents, Two-Step Cluster Analysis identified two key consumer types: “Plastic Avoiders” and “Plastic Users.” The two groups differed significantly on demographic characteristics, media use/exposure, and theoretical constructs. The most important predictors of group membership were self-efficacy and work status. An experiment involving pre-existing environmental media communications revealed that perceptions, intentions, and behaviors were influenced differently across the two audiences. The findings suggest that mobilizing existing media content may provide a cost-effective way for environmental communicators to increase their public impact while avoiding unintended consequences.

Plastic pollution is a global problem which negatively impacts climate change, biodiversity, and human health (Vince & Stoett, Citation2018). Since the 1950s, over 6000 million tonnes of plastic waste has been generated, of which around 80% is sent to landfill or ends up in the environment (Watkins et al., Citation2019). While technological solutions (e.g. biodegradable alternatives to synthetic plastics) and structural solutions (e.g. replacing single-use plastics with reusable alternatives) have a role to play in waste prevention, policymakers and practitioners can take action in the short term by adopting social marketing practices to encourage plastic avoidance behavior change (Cleary, Citation2014). By understanding the specific behaviors and target audiences which need to change, practitioners can design more effective interventions, tailored to the thoughts and actions of different groups.

The aim of the current study was to understand how different audiences think and act regarding single-use plastics. Specifically, this research sought to: (1) identify behavioral-based segments of plastic consumers; (2) determine the predictors of group membership, including demographic factors, media use/exposure factors, and theory-based factors; and (3) empirically test which group’s perceptions and behaviors were influenced by different plastic-related media content. The insights from this research aid in conceptualizing and designing effective plastic avoidance communication strategies for specific target audiences.

Audience segmentation

Behavior is an observable event involving an action directed at a target, performed in a particular context and time (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2011). While this definition is quite narrow, behavior change interventions are most effective when these four elements are considered because a change in any one element will change the influencers of the behavior. There is, however, a fifth element which also contributes to successful intervention design: the audience. As articulated by Metag and Schäfer (Citation2018, p. 995), “people differ. Not only do they vote for different parties, buy different products, have different hobbies and use different media. They also differ in their interest in, attitudes on, and behavior towards scientific and environmental issues.” In order to promote pro-environmental behaviors, like plastic avoidance, practitioners must first define and understand the behavior(s) and audience(s) they are trying to change.

Segmentation is often used in social marketing to “divide the general public into relatively homogeneous, mutually exclusive subgroupings” (Hine et al., Citation2014, p. 442). Once defined, communication strategies can be tailored to the needs and values of specific groups to change their behavior for personal and societal benefit (Andreasen, Citation1994). While segmentation has a long history in marketing, there are still gaps in the literature. Historical approaches have typically used socio-demographic and psychographic characteristics to define target groups. As stated by Yankelovich and Meer (Citation2006, p. 1) “the psychographic profiling that passes for market segmentation these days is a mostly wasteful diversion from its original and true purpose – discovering customers whose behaviour can be changed or whose needs are not being met.” To address this, there is growing support for behavioural segmentation which uses behavior-based variables, such as purchasing behaviors or media consumption, to segment populations (Metag & Schäfer, Citation2018). Such an approach provides a more nuanced understanding of target audiences based on the primary outcome of interest: behavior.

There is also growing interest in the use of segmentation to understand beliefs and attitudes towards environmental issues, such as Newton and Meyer’s (Citation2013) environmental lifestyle segments, Poortinga and Darnton’s (Citation2016) sustainability segmentation model, and Tkaczynski et al.’s (Citation2020) environmental tourism segments. Climate change segmentation in particular is providing useful insights for policymakers. For example, “Global Warming’s Six Americas” (Chryst et al., Citation2018; Leiserowitz et al., Citation2019) has been collecting data on American’s climate change attitudes and behaviors since 2008. The approach has also been adapted to identify Global Warming’s Six Australias, Six Indias, and Five Germanys (Metag et al., Citation2017). Despite increased interest in climate change communication and audience segmentation, Hine et al. (Citation2014) found that most studies in this space have adopted an atheoretical approach and that few studies empirically tested how the identified segments are influenced by communications. This is significant because theory and testing can strengthen segmentation research, not only by providing justification for the use of particular variables but by offering a framework for understanding and influencing the processes which may lead to behavior change (Hine et al., Citation2014).

Furthermore, although climate change segmentation is becoming prevalent, the approach has rarely been applied to other environmental issues, such as plastic pollution. Previous research has identified that social marketing approaches are important for promoting plastic avoidance (Carrigan et al., Citation2011; Eagle et al., Citation2016). However, there is currently no published research which aims to identify and understand how different audiences use and avoid single-use plastics or how these groups respond to related communications. This is particularly relevant, given the recent increase in plastic reduction policies (Schnurr et al., Citation2018; Xanthos & Walker, Citation2017) and subsequent plastic-related media content – which may already be influencing individual behavior in an undesirable way. For example, the prevalence of plastic waste is often presented in information-based communications (e.g. news and documentaries) with the aim of drawing attention to the scale of the problem. However, this approach may unintentionally influence perceptions among those who continue to use single-use plastics that their behavior is common and acceptable.

Theorizing normative behavior

Messages which influence such perceptions can be problematic. This is because social norms – the unwritten social rules regarding common (descriptive norms) and acceptable (injunctive norms) behaviors (Cialdini & Trost, Citation1998) – are a well-known behavioral influencer particularly in the context of pro-environmental behavior (for a review, see Farrow et al., Citation2017). In a recent review of empirical literature related to plastic consumption and disposal, Heidbreder et al. (Citation2019) found that, in addition to habits, plastic consumption was mostly influenced by social norms. This suggests that communications which aim to reduce plastic consumption are likely be more successful if they focus on promoting the desired social norm of plastic avoidance.

The current study uses the theory of normative social behavior (TNSB) as a guiding framework (Lapinski & Rimal, Citation2005; Rimal & Lapinski, Citation2015; Rimal & Real, Citation2003). According to the TNSB, perceived descriptive norms influence behavioral intentions but this relationship is moderated by perceived injunctive norms, outcome expectations, group identity, and behavioral identity (Rimal et al., Citation2005). In other words, the relationship between descriptive norms and behavioral intentions becomes stronger (or weaker) with higher (or lower) levels of these variables. Outcome expectations are beliefs regarding the benefits of engaging in a particular behavior (Rimal et al., Citation2005). Group identity refers to the extent to which an individual identifies with the reference group in question (Rimal et al., Citation2005). Finally, behavioral identity is the extent to which an individual’s self-identity aligns with the enactment of the behavior in question (Lapinski et al., Citation2007).

Previous research testing the TNSB in the context of plastic avoidance found that injunctive norms and outcome expectations related to perceived benefits (along with self-efficacy and anticipated costs) moderated the descriptive norm-behavior relationship (Borg et al., Citation2020). However, injunctive norms and outcome expectations were also found to directly predict intentions to avoid single-use plastics. This suggests that, in addition to moderating the norm-behavior relationship, perceptions about the prevalence (social norms) and impact (outcome expectations) of plastic avoidance are also predictors of individual-level behaviors. Therefore, by increasing perceptions that plastic avoidance is common (descriptive norm), decreasing perceptions that plastic use is acceptable (injunctive norms), and increasing perceptions that plastic avoidance is beneficial (outcome expectations) practitioners could significantly increase intentions to avoid single-use plastics.

A key premise of the TNSB is the recognition that social norms are influenced by communication (Rimal & Lapinski, Citation2015). Mead et al. (Citation2014, p. 140) call this process social exposure – i.e. “cues an individual receives from his or her social, physical, and symbolic environments” (Mead et al., Citation2014, p. 140). The social environment (i.e. family, friends, neighbors, colleagues, and strangers) is the most influential source of social information, particularly from those closest to an individual (Shepherd, Citation2017). However, the symbolic environment (i.e. entertainment and news media and marketing) can provide social information to a much wider audience. This proposition aligns with social cognitive theory, which recognizes that a great deal of information about others’ attitudes (injunctive norms), behaviors (descriptive norms), and behavioral consequences (outcome expectations) is shared via the symbolic environment of the media (Bandura, Citation2009). Therefore, it is possible that media exposure could influence multiple variables within the TNSB, including perceptions about social norms as well as outcome expectations related to the benefits of avoidance.

The current study

The Australian state of Victoria, like many jurisdictions around the world, recognizes that plastic pollution is an urgent global environmental problem and the Victorian Government is committed to phasing out a range of problematic single-use plastics by 2023.Footnote1 In 2017, the government announced its intentions to ban lightweight plastic bags across the state, which came into effect in November 2019.Footnote2 Between the announcement of the ban and its implementation, Victorians were also subject to a nationwide phase-out of free lightweight plastic bags by the country’s two largest supermarkets (Dulaney, Citation2017), as well as two significant and popular TV series which focused on the issue of plastic pollution – BBC’s Blue Planet IIFootnote3 and ABC’s War on Waste.Footnote4

This fluctuating policy and media context across Victoria in relation to single-use plastics provided a unique opportunity to study related behaviors at a time when the subject was salient in the public consciousness. Thus, the objectives of this paper are twofold: to address gaps in segmentation literature, by adopting a behavior-based segmentation approach, underpinned by theory and empirical testing; and to provide practical insights for policymakers and environmental communicators to design effective behavior change strategies for encouraging more people to avoid single-use plastics more often.

The current study was designed to build on previous research which identified TNSB constructs as predictors of plastic avoidance (Borg et al., Citation2020), by first using an exploratory data-driven approach to identify different segments of plastic consumers, and then determining how constructs from the TNSB (along with demographic characteristics and media exposure) predicted group membership. We then experimentally tested if viewing short video clips from existing media content about plastic waste could influence perceptions relating to social norms (descriptive and injunctive) and outcome expectations (perceived benefits) as well as plastic avoidance behaviors among the different groups. Specifically, it was hypothesized that:

Video clips which focused on the volume of plastic waste would negatively influence descriptive norm perceptions (i.e. that plastic avoidance was uncommon) (H1);

Video clips which focused on the impact plastic waste has on wildlife would positively influence perceptions about outcome expectations (i.e. that plastic avoidance is beneficial) (H2); and

Video clips that included explicit social reactions would positively influence perceived injunctive norms (i.e. that others disapprove of plastic use) (H3).

Additionally, given that viewing more information-based media has been linked with engaging in more pro-environmental behaviors (Holbert et al., Citation2003; Huang, Citation2016), it was also hypothesized that viewing any video clip from a documentary about plastic pollution could positively influence avoidance intentions and reported behavior (H4).

Materials and methods

Research design

The sample for this study was recruited via a panel research company. Eligible participants (i.e. Victorian adults aged 18 years or over) were randomly drawn from the research company’s panel of members and emailed an invitation to complete the online survey. Quota limits were applied so that the sample broadly reflected the Victorian population for gender, age group, and geographic region. Post-stratification cell weights were also calculated for age group by gender to compensate for low-responding cohorts (e.g. young males). The target sample size was n = 1000 which was chosen to provide 95% confidence that any differences detected would be accurate within approximately three percentage points.

First, respondents were asked a series of baseline questions to measure their existing perceptions and behaviors. Each respondent was then randomly allocated to view one of five short video clips – four clips were taken from existing documentaries about plastic waste (experimental) and one was about how plastic is made (control). A summary of the clips used in the experiment is provided in .

Table 1. Video clip descriptions.

The experimental clips were chosen because of the way they presented the issue of plastic waste (i.e. volume-focused or impact-focused) and whether explicit social reactions were present or absent. As such, it was anticipated that V1 and V2 (volume-focused) would negatively influence descriptive norm perceptions (H1); that V3 and V4 (impact-focused) would positively influence perceptions about outcome expectations (H2); that V2 and V4 (explicit social reactions) would positively influence perceived injunctive norms; and that all four experimental clips (V1 to V4) would positively influence avoidance intentions and reported behavior (H4).

Immediately after viewing the video clips, respondents were asked to indicate their avoidance intentions and those who agreed to recontact were sent a second follow-up survey approximately one month later. The follow-up survey contained similar questions to baseline in order to determine if there were any lasting changes in perceptions and if any intentions translated into actions. In total 1001 respondents completed the main survey in July 2019 and were included in the segmentation analyses. Of those who completed the survey, 23 indicated that the video did not display properly and 95 declined to be recontacted. A priori power analysis (for a paired sample t-test) indicated that for the follow-up survey a minimum of 90 respondents per group would be required to detect an effect size of 0.3 with a power of .80 and an alpha of .05. Five hundred and fifteen respondents completed the follow-up survey in August 2019 (between n = 92 and n = 114 per group) and were included in the experimental analyses. A CONSORT participant flow diagram across the five conditions is provided in the Supplementary Material. The research was approved by the author’s University Human Research Ethics Committee (project #20064).

Measures

The demographic questions included in the original survey were: age, gender (female; male), region (greater Melbourne; rest of Victoria), work status (not working; working), education level (less than a bachelor's degree; bachelor's degree or higher), weekly household income (up to $649; $650 to $1249; $1250 to $2999; $3000+), speaks a non-English language (yes; no), and born in Australia (yes; no).

The scale variables included in the surveys are provided in . Media use and exposure were measured by first asking respondents how often they used news media, social media, or watched environmental documentaries (adapted from Holbert et al., Citation2003; Shehata & Strömbäck, Citation2018). Next respondents were asked how often they had seen news stories or social media content about plastic waste (Huang, Citation2016; Yang & Zhao, Citation2018). Finally, respondents were asked about their level of familiarity with the four tested documentaries about plastic pollution: War on Waste, Blue Planet II, A Plastic Ocean, and Drowning in Plastic.

Table 2. Summary of scale survey measures.

Two sets of questions were used to capture behavior: reported behaviour and behavioural intentions. Respondents were asked what percentage of the time they had used or intended to use each single-use item in certain contexts. The specific behaviors were: using (action) single-use plastic bags (target) when shopping (context/time); using (action) plastic straws (target) when buying a drink at a café, restaurant or bar (context/time); using (action) disposable coffee cups (target) when buying a hot beverage (context/time); and using (action) plastic take-away containers (target) when buying take-away food (context/time). Behavioral intentions were measured at baseline and immediately after viewing the videos, and reported behaviors were measured at baseline and follow-up.

The TNSB measures were adapted from previous research. Social norms were measured by asking respondents what percentage of time they believed most Victorians used various single-use items (perceived descriptive norms) (adapted from Lapinski et al., Citation2013) and to what extent they believed most Victorians disapproved or approved of using the item (perceived injunctive norms) (Real & Rimal, Citation2007). Outcome expectations were measured by asking respondents to rate their level of disagreement or agreement with the benefits of avoiding each item (self- and environmental) (modified from Real & Rimal, Citation2007; Rimal, Citation2008), as well as their agreement with statements describing barriers to avoidance, self-efficacy (Koletsou & Mancy, Citation2011) and anticipated costs (modeled after the perceived benefits question). Group identity (adapted from Lapinski et al., Citation2013; Postmes et al., Citation2013) and behavioural identity (Lapinski et al., Citation2017) were measured using two statements each to determine how strongly respondents identified with other Victorians and how strongly they identified as a plastic avoider. Descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and perceived benefits (self and environmental) were measured at baseline and follow-up.

Analyses

Behavioral segmentation was conducted using TwoStep Cluster analysis in SPSS 25.0, with log-likelihood distance measure. Cluster analysis is an exploratory statistical technique which sorts cases into groups based on data patterns so that cases “fit” together (Han et al., Citation2012). TwoStep Cluster analysis involves first grouping cases into pre-clusters (step 1) which are then used in hierarchical clustering to determine the best number of clusters (step 2) (Tkaczynski, Citation2017). This method has been adopted previously to identify behavioral-based typologies (Borg & Smith, Citation2018; Okazaki, Citation2006) and is often favored over traditional techniques due to its ability to include both categorical and scale data, manage large datasets, automatically determine the number of clusters, and determine predictor importance of included variables (Tkaczynski, Citation2017).

For the purpose of identifying behavioural clusters of plastic consumers, the four behavioral intention measures from the baseline survey were included in the analysis – i.e. intentions to use single-use plastic bags when shopping; intentions to use plastic straws when buying a drink at a café, restaurant or bar; intentions to use disposable coffee cups when buying a hot beverage; and intentions to use plastic take-away containers when buying take-away food. Cluster groupings are presented in the Results section.

For the remaining analyses behavioral intentions, reported behavior, and descriptive and injunctive norms were reverse coded so that higher values reflected plastic avoidance. Bivariate analyses were then conducted to understand significant differences between the cluster groups – using independent sample t-tests for scale variables and chi-square for categorical variables. To determine the relative importance of each variable in predicting cluster membership, while controlling for the influence of other variables in the model, Binomial Logistic Regression (OLS) was then conducted. Three regression models were included: Model 1 included demographic variables only, Model 2 included demographic and media use/exposure variables, and Model 3 included demographic, media use/exposure, and the theoretical constructs from the TNSB.

Finally, to determine the effects of the experimental video clips on the different cluster groups a series of paired-samples t-tests were conducted to detect pre–post differences for each hypothesized effect for each cluster group. One-sided tests were conducted for all hypothesized comparisons outlined in the Research Design. Adjusting for multiple comparisons, using Bonferroni correction, results from the paired t-tests for H1, H2, and H3 were adjusted for two-tests (p < .025), given that two videos were anticipated to influence each of the related outcomes, and results for H4 were adjusted for four-tests (p < .013) given that all four videos were anticipated to influence behavior. These analyses included respondents who completed the main and follow-up surveys for whom the video displayed properly (n = 515). For subgroups with a small sample size (n < 30), the non-parametric version of the paired t-test (Wilcox Signed Rank Test) was used. For descriptive norms, injunctive norms, self-benefits and environmental benefits baseline measures were paired with the follow-up survey measures. Behavioral intentions were paired at baseline and immediately post-viewing, and reported behaviors were paired at baseline and follow-up.

Results

Cluster groupings

The auto-clustering algorithm identified a two-cluster solution with a silhouette measure of cohesion and separation of 0.62Footnote5 (Cluster 1, n = 655, 65%; Cluster 2, n = 346, 35%). While all four predictor variables provided a statistically significant contribution to the cluster solution, the least important variable (i.e. the variable with the smallest difference in mean scores between the two groups) was intentions to use single-use plastic bags when shopping (predictor importance 0.4, compared to 0.9 or higher for the other three behaviors).

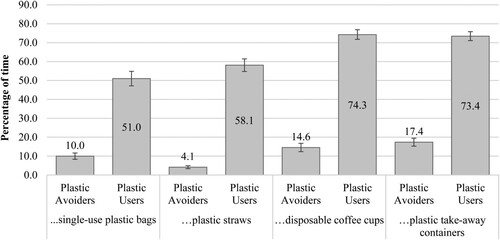

The differences in mean scores (with 95% CIs) for intentions to use each single-use item are provided in . Before viewing the video clips, Cluster 1 intended to use each single-use item less than 20 percent of the time (ranging from 4.1–17.4 percent of the time). Cluster 2 intended to use each item significantly more often (all p < .001) – ranging from 51.0–74.3 percent of the time. Based on the intentions of the two groups, they were labeled “Plastic Avoiders” (Cluster 1) and “Plastic Users” (Cluster 2).

Figure 1. Mean percentage of time respondents intend to use each single-use item during the next month – by cluster group.

To understand the general profile of each of the identified groups, bivariate analyses were then conducted. As seen in , the two groups differed significantly (p < .05) in relation to most characteristics with the exception of country of birth, environmental documentary use, plastic news exposure, familiarity with Blue Planet II and Drowning in Plastic, and group identity.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of evaluation criteria by cluster group – mean (standard deviation) for scale variables and “Column % (Number of cases)” for categorical variables.

Predictors of cluster groupings

Next, to determine the relative importance of each variable in predicting cluster membership, while controlling for the impact of other variables, Binominal Logistic Regression (OLS) was conducted, using “Plastic Avoiders” as the reference group. presents the unstandardized regression coefficients (B) with standard errors (SE), odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval for odds ratio (95% CI for OR). Model 1 (demographic characteristics only) was statistically significant (χ2 (10, n = 1001) = 155.19, p < .001) and explained between 14.4% (Cox and Snell R square) and 19.8% (Nagelkerke R squared) of the variance in group membership. According to Model 1, the likelihood of being an “Avoider” increased with age. Additionally, those living in a moderate-high-income household (compared to a high-income household) were almost twice as likely to be “Plastic Avoiders.” In contrast, people who lived in Melbourne and people who were working were one and a half times more likely to be “Plastic Users.”

Table 4. Logistic regression output: Predictors of “Plastic Avoiders” group membership.

When the media variables were added in Model 2, the model was still significant (χ2 (19, n = 1001) = 181.71, p < .001), but the addition of these variables did not contribute much to the variance in group membership (between 16.6% and 22.9%). According to Model 2 females and those more familiar with War on Waste were slightly more likely to be “Plastic Avoiders,” whereas those more familiar with A Plastic Ocean were one and a half times more likely to be “Plastic Users.”

The final model, Model 3, which included theoretical constructs from the TNSB, was not only significant (χ2 (27, n = 1001) = 451.12, p < .001), but explained between 36.3% and 50.1% of the variance in group membership – highlighting the importance of taking a theoretical approach to segmentation analysis. After controlling for the TNSB constructs, gender, region, income, and War on Waste familiarity were no longer significant predictors of group membership. The most important predictors in the final model were self-efficacy (OR = 1.575) and work status (OR = 0.632). In other words, those who were confident in their ability to avoid single-use plastics (self-efficacy) were one and a half times more likely to be “Plastic Avoiders” while those who were working were one and a half times more likely to be “Plastic Users.” Those who believed others avoided (descriptive norms) and disapproved of using (injunctive norms) single-use plastics, and that plastic avoidance was beneficial for the self and the environment (perceived benefits) were also more likely to be “Plastic Avoiders.” In contrast, those who believed that avoiding plastic would have anticipated costs and who identified as a plastic avoider were slightly more likely to be “Plastic Users.”

Experimental effects by cluster groups

and present the results of the paired-samples t-tests (or Wilcox Signed Rank Tests for subgroups with n < 30) for respondents who completed both surveys (n = 515).

Table 5. Paired-samples T-tests by experimental group – “Plastic Avoiders.”

Table 6. Paired-samples T-tests by experimental group – “Plastic Users.”

H1 was partially supported because “Plastic Avoiders” who viewed V1 reported a significant decrease (p = .011) in perceived descriptive norms at follow-up (i.e. they believed others were avoiding single-use plastics less often). However, no such effect was found for “Plastic Avoiders” who viewed V2 and there was no change in perceived descriptive norms among “Plastic Users” who viewed V1 or V2.

H2 was also partially supported because one month after viewing V4 “Plastic Users” perceptions of the self-benefits of avoidance increased (p = .008). However, there was no change in perceived benefits for “Plastic Users” who viewed V3, nor for “Plastic Avoiders” who viewed V3 or V4. H3 was not supported because there were no significant changes in injunctive norms among either group in any condition. While there was no change in intentions or behavior among “Plastic Avoiders,” H4 was mostly supported among “Plastic Users.” Those who viewed V2 intended to avoid single-use plastics more often (p = .005) and those who viewed V3 or V4 intended to avoid (both p < .001) and reported avoiding single-use plastics more often at follow-up (V3, p=.008, V4, p < .001). There was no change in intentions or reported behavior among “Plastic Users” who saw V1.

Discussion

This research sought to identify behavioral-based segments of plastic consumers and to determine the predictors of group membership. A two-group typology of consumers was identified based on respondents’ behavioral intentions: “Plastic Avoiders” (65%) and “Plastic Users” (35%). In addition to their intentions, the two groups differed significantly in relation to many demographic, media use/exposure, and theory-based characteristics. When controlling for the influence of all the variables together, the strongest predictors of group membership were self-efficacy of plastic avoidance and work status. Once the groups were identified, the final objective of this research was to empirically test which group’s behaviors and perceptions were susceptible to change in response to existing plastic-related media content. After viewing short video clips about plastic pollution, “Plastic Avoiders” perceptions were negatively affected among those who saw the volume-focused clip that did not include explicit social reactions. Whereas, there were several positive effects among “Plastic Users” depending on which video they viewed. The implications of these findings are discussed below.

Identifying target audiences

The two-group solution identified by our data-driven segmentation reveals that, in the context of single-use plastic avoidance, there are not necessarily varying behavioral patterns. For example, we did not find that certain consumers use plastic bags and straws but avoid cups and containers, while others avoid cups and containers but use bags and straws. Instead, we found that consumers either intended to avoid single-use plastics in general or they intend to use them. While modest, the two groups represent more specific target audiences compared to the general population – audiences that environmental communicators should keep in mind when designing future material.

Those who are older and confident in their ability to avoid single-use plastics, and who believe that others avoid often, disapprove of using plastics, and that avoidance is beneficial are more likely to be “Plastic Avoiders.” In contrast, those who are working, who believe that plastic avoidance will cost money, and, surprisingly, those more familiar with A Plastic Ocean and who identify as a plastic avoider are more likely to be “Plastic Users.” The inclusion of the theoretical constructs from the TNSB in this research not only provided additional information about each group, but allowed for the correction of apparent effects from other variables (Pallant, Citation2013) such as household income, region, and gender, which were no longer significant in the final model. In other words, while those living in greater Melbourne were overrepresented among “Plastic Users,” the group’s tendency to use single-use plastics more often was not directly related to where people lived but was predicted by their perceptions and confidence. This supports the importance of adopting a theory-based approach in segmentation analysis (Hine et al., Citation2014).

The importance of age and work status in predicting group membership in the final model aligns with previous research on pro-environmental behaviors more broadly. While young people generally have a higher level of environmental concern, their behavior does not always follow (Chan-Halbrendt et al., Citation2009; Olli et al., Citation2001). In contrast, older generations – regardless of their attitude – tend to engage in waste reduction behaviors more often (Kurisu & Bortoleto, Citation2011). This apparent contradiction has been attributed to the convenience culture in which young people have grown up, where take-away is the norm, compared to generations who experienced times when frugality and thrift were the norm (Olli et al., Citation2001). The contribution of work status to group membership may be a function of feeling time poor with perceived limited time available for engaging in behaviors which require forethought and planning, such as carrying and cleaning reusable alternatives. As found by Ertz et al. (Citation2016), consumers who have more time available are more likely to perceive pro-environmental behaviors as more important and less costly – which would also explain why those with higher ratings for the anticipated costs of avoidance were more likely to be “Plastic Users.”

The role of familiarity with A Plastic Ocean and behavioral identity in predicting group membership was somewhat unexpected. Previous research has found that environmental identity can positively predict consumption behaviors – such as use of green shopping bags and dematerialization (Cherrier, Citation2006; Whitmarsh et al., Citation2017). Similarly, exposure to information-based media content, such as news and documentaries, has been found to be positively associated with pro-environmental behaviors (Holbert et al., Citation2003; Huang, Citation2016). Given that “Plastic Users” are also less likely to believe that others are avoiding plastic, our findings may point to a mismatch in their expectations. While additional research is required to test this proposition, “Plastic Users” may believe that they are “avoiders” relative to their beliefs about others’ behavior.

Different effects for different audiences

Given that those who were familiar with A Plastic Ocean were more likely to be “Plastic Users” and that exposure to a clip from the film negatively influenced descriptive norm perceptions among “Plastic Avoiders,” this may suggest that the film is presenting plastic use as normal. In contrast, the clip from War on Waste did not affect either group’s perceptions about social norms. This may be related to the presence of conflicting descriptive and injunctive norm messaging. While both clips focused on the volume of plastic waste (signaling that use is common), the clip from War on Waste also included explicit disapproval reactions (signaling that plastic use is disapproved by others). Presenting plastic use as common with no information about social reactions may also explain why “Plastic Users” who viewed the clip from A Plastic Ocean were the only experimental group whose behavioral intentions did not change. Given that descriptive norms are an important predictor of plastic avoidance intentions (Borg et al., Citation2020), if the clip reinforced perceptions that plastic use was normal, “Plastic Users” would be unlikely to change their intentions.

The apparent boomerang effect in descriptive norm perceptions among “Plastic Avoiders” who viewed the clip from A Plastic Ocean suggests that focusing on the volume of plastic waste, with no information about social reactions, may have signaled that plastic use is normal. The negative effect of the clip from A Plastic Ocean on “Plastic Avoiders” perceptions also emphasizes the importance of considering all user-groups in communication strategies. While “Plastic Avoiders” already comply with the desired behavior, they should not be ignored. Previous research has found that compliers are still drawn to the perceived descriptive norm (Schultz et al., Citation2007) and that praise is an effective method for maintaining and improving compliance behaviors (Makkai & Braithwaite, Citation1993). Environmental communicators should test messaging on different audiences – including those who are already complying with desired behaviors – in order to avoid unintended consequences, such as unintentionally promoting undesirable social norms.

While “Plastic Users” who saw the clip from Drowning in Plastic (impact-focused, including explicit social reactions) agreed more with the self-benefits of avoidance, the most notable influence of the experimental clips was on “Plastic Users” intentions and reported behavior. After viewing one of the impact-focused clips or one of the clips that included explicit social reactions, avoidance intentions increased significantly among “Plastic Users” immediately after viewing. This highlights that short videos which are commonly shared on social media can influence behavioral intentions among the priority target audience (“Plastic Users”), even when such clips are not specifically designed to do so. However, it is important to recognize that only the impact-focused clips led to a change in actual (reported) behavior one month after the experiment.

Limitations and future research

While the current study provides insights into segmentation research and plastic avoidance media messages, it is not without limitations. First, while our findings support the importance of TNSB constructs in predicting group membership based on intentions to avoid or use four specific items, they may not be applicable to other single-use items (e.g. plastic bottles, food wrappers, plastic cutlery) or other contexts (e.g. private settings such as the home or workplace). This is important because contextual factors are known influencers of waste-related behaviors (Whitmarsh et al., Citation2018). Additionally, the behaviors in the current study were relatively similar and somewhat easier to undertake compared to some avoidance behaviors – such as shopping at bulk food or package-free stores. While the selected behaviors were chosen because they reflected priority single-use plastic items in Victoria (State Government of Victoria, Citation2018), and are arguably more amenable to behavior change interventions, it is possible that the inclusion of a variety of avoidance behaviors may have identified more diverse plastic consumer segments beyond users and avoiders. Future research which involves a combination of simple and complex plastic avoidance behaviors, in varied contexts is recommended to further develop this field.

Second, while this study was underpinned by theory, the TNSB is intended to explore the role of social norms in predicting behavior. Consequently, our findings do not capture all possible drivers of plastic consumption. For example, in addition to social norms, the review conducted by Heidbreder et al. (Citation2019) identified convenience, knowledge and opportunity regarding alternatives, habits, and personal responsibility as influencers of plastic avoidance. Furthermore, a blanket hypothesis about the positive behavioral effects of viewing any of the experimental clips (H4) may seem at odds with the other hypotheses in this study. Nevertheless, our intention was to explore the proposed link between viewing information-based media content and pro-environmental behaviors (Holbert et al., Citation2003; Huang, Citation2016) in the context of plastic avoidance – recognizing that influence pathways may sit outside the limited TNSB constructs. However, our results suggest that presenting plastic use as common, with no information about impact or social reactions, may indeed be sufficient to constrain avoidance behaviors.

Finally, the while use of pre-existing stimuli provides a novel contribution to the field, it also represents a limitation. The aim of our research was to determine if video clips with selected attributes influenced consumers’ perceptions and behaviors. However, there are numerous features within the videos which could be contributing to the observed variances, such as video location, presenter characteristics, or emotional arousal. Future research is recommended using more controlled stimulus to determine why particular clips were more or less effective. For example, creating modified versions of one of the tested clips which specifically include and exclude the attributes of interest (i.e. waste-focus, impact-focus, and explicit social reactions).

Conclusion

Our research highlights the value of adopting a theoretical approach to segmentation research. We were able to establish that not only were perceived social norms and perceived benefits significant predictors of group membership, but that these perceptions (along with behavior) could be influenced after viewing short video clips about plastic pollution. Understanding who generally uses or avoids single-use plastics and how these groups respond to existing media content provides environmental communicators with formative and accessible avenues for designing more sophisticated campaigns that avoid a one-size-fits-all approach. First, communicators would do well to focus on the impact of plastic pollution, rather than the volume of plastic waste, in order to promote positive change and avoid unintended consequences. Second, rather than developing new content, which can be time consuming and expensive, communicators could utilize the most effective video clips from the current study – which are already prevalent on social media – as a cost-effective way of increasing their public impact. Finally, given that “Plastic Users” report using social media almost daily, promoting such messages on social media platforms would likely help to normalize plastic avoidance among this group.

While the current study focused on the influence of media on different audiences, we recognize that individual-level behavior change is only part of the plastic avoidance equation. Ideally, behavior change initiatives should be implemented in parallel with government policies (e.g. single-use plastic bans) and changes in business practices (e.g. offering plastic-free products) to achieve systemic change. Collectively, individual, business and government efforts need to integrate with each other to realize and support such ambitions.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (129.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the research participants for their time and insights and the data collection agency, Dynata. This research was completed as part of a PhD undertaken at Monash University. This work was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

5 Cluster analysis was also conducted with a forced number of groups which confirmed that the two-cluster solution provided the strongest silhouette measure compared to a three- (0.56) or four-group (0.51) solution.

References

- Andreasen, A. R. (1994). Social marketing: Its definition and domain. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 13(1), 108–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569401300109

- Bandura, A. (2009). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In J. Bryant, & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 110–140). Routledge.

- Borg, K., Curtis, J., & Lindsay, J. (2020). Social norms and plastic avoidance: Testing the theory of normative social behaviour on an environmental behaviour. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1842

- Borg, K., & Smith, L. (2018). Digital inclusion and online behaviour: Five typologies of Australian internet users. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37(4), 367–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1436593

- Carrigan, M., Moraes, C., & Leek, S. (2011). Fostering responsible communities: A community social marketing approach to sustainable living. Journal of Business Ethics, 100(3), 515–534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0694-8

- Chan-Halbrendt, C., Fang, D., & Yang, F. (2009). Trade-offs between shopping bags made of non-degradable plastics and other materials, using latent class analysis: The case of Tianjin, China. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 12(4), 179–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.92561

- Cherrier, H. (2006). Consumer identity and moral obligations in non-plastic bag consumption: A dialectical perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(5), 515–523. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2006.00531.x

- Chryst, B., Marlon, J., van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., & Roser-Renouf, C. (2018). Global warming’s “six Americas short survey”: Audience segmentation of climate change views using a four question instrument. Environmental Communication, 12(8), 1109–1122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1508047

- Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

- Cleary, J. (2014). A life cycle assessment of residential waste management and prevention. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 19(9), 1607–1622. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-014-0767-5

- Dulaney, M. (2017, 14 July). Coles to follow Woolworths’ lead and phase out plastic bags around the country, ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-07-14/woolworths-to-phase-out-plastic-bags-around-the-country/8709336.

- Eagle, L., Hamann, M., & Low, D. R. (2016). The role of social marketing, marine turtles and sustainable tourism in reducing plastic pollution. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 107(1), 324–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.03.040

- Ertz, M., Karakas, F., & Sarigöllü, E. (2016). Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 3971–3980. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.06.010

- Farrow, K., Grolleau, G., & Ibanez, L. (2017). Social norms and pro-environmental behavior: A review of the evidence. Ecological Economics, 140, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.04.017

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2011). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Taylor & Francis.

- Han, J., Kamber, M., & Pei, J. (2012). Data mining: Concepts and techniques (3rd ed., pp. 443–495). Morgan Kaufmann.

- Heidbreder, L. M., Bablok, I., Drews, S., & Menzel, C. (2019). Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Science of the Total Environment, 668, 1077–1093. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.437

- Hine, D. W., Reser, J. P., Morrison, M., Phillips, W. J., Nunn, P., & Cooksey, R. (2014). Audience segmentation and climate change communication: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 5(4), 441–459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.279

- Holbert, R. L., Kwak, N., & Shah, D. V. (2003). Environmental concern, patterns of television viewing, and pro-environmental behaviors: Integrating models of media consumption and effects. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 47(2), 177–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4702_2

- Huang, H. (2016). Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 2206–2212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.031

- Koletsou, A., & Mancy, R. (2011). Which efficacy constructs for large-scale social dilemma problems? Individual and collective forms of efficacy and outcome expectancies in the context of climate change mitigation. Risk Management, 13(4), 184–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/rm.2011.12

- Kurisu, K. H., & Bortoleto, A. P. (2011). Comparison of waste prevention behaviors among three Japanese megacity regions in the context of local measures and socio-demographics. Waste Management, 31(7), 1441–1449. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2011.03.008

- Lapinski, M. K., Maloney, E. K., Braz, M., & Shulman, H. C. (2013). Testing the effects of social norms and behavioral privacy on hand washing: A field experiment. Human Communication Research, 39(1), 21–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2012.01441.x

- Lapinski, M. K., & Rimal, R. N. (2005). An explication of social norms. Communication Theory, 15(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00329.x

- Lapinski, M. K., Rimal, R. N., DeVries, R., & Lee, E. L. (2007). The role of group orientation and descriptive norms on water conservation attitudes and behaviors. Health Communication, 22(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230701454049

- Lapinski, M. K., Zhuang, J., Koh, H., & Shi, J. (2017). Descriptive norms and involvement in health and environmental behaviors. Communication Research, 44(3), 367–387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215605153

- Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C., Rosenthal, S., & Myers, T. (2019). Global warming’s six Americas. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/about/projects/global-warmings-six-americas/.

- Makkai, T., & Braithwaite, J. (1993). Praise, pride and corporate compliance. International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 21, 73–73.

- Mead, E. L., Rimal, R. N., Ferrence, R., & Cohen, J. E. (2014). Understanding the sources of normative influence on behavior: The example of tobacco. Social Science and Medicine, 115, 139–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.030

- Metag, J., Füchslin, T., & Schäfer, M. S. (2017). Global warming’s five Germanys: A typology of Germans’ views on climate change and patterns of media use and information. Public Understanding of Science, 26(4), 434–451. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662515592558

- Metag, J., & Schäfer, M. S. (2018). Audience segments in environmental and science communication: Recent findings and future perspectives. Environmental Communication, 12(8), 995–1004. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1521542

- Newton, P., & Meyer, D. (2013). Exploring the attitudes-action gap in household resource consumption: Does “environmental lifestyle” segmentation align with consumer behaviour? Sustainability, 5(3), 1211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su5031211

- Okazaki, S. (2006). What do we know about mobile Internet adopters? A cluster analysis. Information & Management, 43(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2005.05.001

- Olli, E., Grendstad, G., & Wollebaek, D. (2001). Correlates of environmental behaviors: Bringing back social context. Environment and Behavior, 33(2), 181–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121972945

- Pallant, J. (2013). SPSS survival manual. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Poortinga, W., & Darnton, A. (2016). Segmenting for sustainability: The development of a sustainability segmentation model from a Welsh sample. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 221–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.01.009

- Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jans, L. (2013). A single-item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12006

- Real, K., & Rimal, R. N. (2007). Friends talk to friends about drinking: Exploring the role of peer communication in the theory of normative social behavior. Health Communication, 22(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230701454254

- Rimal, R. N. (2008). Modeling the relationship between descriptive norms and behaviors: A test and extension of the theory of normative social behavior (TNSB). Health Communication, 23(2), 103–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230801967791

- Rimal, R. N., & Lapinski, M. K. (2015). A re-explication of social norms, ten years later. Communication Theory, 25(4), 393–409. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12080

- Rimal, R. N., Lapinski, M. K., Cook, R. J., & Real, K. (2005). Moving toward a theory of normative influences: How perceived benefits and similarity moderate the impact of descriptive norms on behaviors. Journal of Health Communication, 10(5), 433–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730591009880

- Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2003). Understanding the influence of perceived norms on behaviors. Communication Theory, 13(2), 184–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00288.x

- Schnurr, R. E. J., Alboiu, V., Chaudhary, M., Corbett, R. A., Quanz, M. E., Sankar, K., Srain, H. S., Thavarajah, V., Xanthos, D., & Walker, T. R. (2018). Reducing marine pollution from single-use plastics (SUPs): A review. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 137, 157–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.10.001

- Schultz, P. W., Nolan, J. M., Cialdini, R. B., Goldstein, N. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2007). The constructive, destructive and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychological Science, 18(5), 429–434. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01917.x

- Shehata, A., & Strömbäck, J. (2018). Learning political news from social media: Network media logic and current affairs news learning in a high-choice media environment. Communication Research, 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217749354

- Shepherd, H. R. (2017). The structure of perception: How networks shape ideas of norms. Sociological Forum, 32(1), 72–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12317

- State Government of Victoria. (2018). Reducing the impacts of plastic on the Victorian Environment – Consultation Report. Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. https://www.environment.vic.gov.au/sustainability/plastic-pollution.

- Tkaczynski, A. (2017). Segmentation using two-step cluster analysis. In T. Dietrich, S. Rundle-Thiele, & K. Kubacki (Eds.), Segmentation in social marketing (pp. 109–125). Springer.

- Tkaczynski, A., Rundle-Thiele, S., & Truong, V. D. (2020). Influencing tourists’ pro-environmental behaviours: A social marketing application. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100740. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100740

- Vince, J., & Stoett, P. (2018). From problem to crisis to interdisciplinary solutions: Plastic marine debris. Marine Policy, 96, 200–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.05.006

- Watkins, E., Schweitzer, J.-P., Leinala, E., & Börkey, P. (2019). Policy approaches to incentivise sustainable plastic design. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/19970900.

- Whitmarsh, L., Capstick, S., & Nash, N. (2017). Who is reducing their material consumption and why? A cross-cultural analysis of dematerialization behaviours. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 375(2095). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2016.0376

- Whitmarsh, L., Haggar, P., & Thomas, M. (2018). Waste reduction behaviors at home, at work, and on holiday: What influences behavioral consistency across contexts? Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02447

- Xanthos, D., & Walker, T. R. (2017). International policies to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-use plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 118(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.02.048

- Yang, B., & Zhao, X. (2018). TV, social media, and college students’ binge drinking intentions: Moderated mediation models. Journal of Health Communication, 23(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2017.1411995

- Yankelovich, D., & Meer, D. (2006). Rediscovering market segmentation. Harvard Business Review, 84(2), 122.