Abstract

A unique figure within Spanish music circles of the 1930s, the Berlin-born Jewish musicologist Otto Mayer-Serra was a central figure in a transnational network of communist musicians actively engaging with musical propaganda in support of the Republic during the Spanish civil war. Hanns Eisler, Ernst H. Meyer, Ernst Busch, Grigori Schneerson, Ferencz Szabó and several members of the Union of Soviet Composers belonged to this network. The article’s first section examines Mayer-Serra’s attempts to introduce in Spain a number of propagandistic musical practices that had been central in the communist splinter group of the German Workers’ Music Movement before 1933. In the second section I discuss Mayer-Serra’s intensive promotion in wartime Spain of the genre of overtly propagandistic ‘battle songs’ composed by members of this network. These practices and repertoires are also studied as part of the powerful movement of Catalan nationalism in 1930s Spain.

Shortly after the Reichstag fire in February 1933, the Berlin-born Jewish musicologist Otto Mayer (1904–1968) — today rather known as Mayer-Serra — left his hometown for good and went into exile in Barcelona, where he stayed until shortly before the end of the Spanish civil war. A complex and unique figure within Spanish music scholarly circles of the time, Mayer-Serra was the first to develop a critical theory of music in Spain based on Marxist philosophy, as well as a central figure in a transnational network of musicians supportive of communism and actively engaging with musical propaganda during the civil war. This article discusses his engagement with Communist musical propaganda before and especially during the Spanish civil war. First, I examine Mayer-Serra’s mostly failed attempts in the period 1933–1936 to introduce in Spain a number of propagandistic musical practices that had been central in the communist splinter group of the German Workers’ Music Movement before the Nazis seized power. In the second section I discuss how the new political and cultural landscape during the Civil War turned the tide for Mayer-Serra’s musico-propagandistic projects and allowed him to intensively promote in Spain the genre of overtly propagandistic leftist songs known then in Germany as Kampflieder (songs of struggle or battle songs). The focus of this study are Mayer-Serra’s close collaborations, from Spain, with a number of non-Spanish musicians abroad, who were politically adjacent to communism and actively engaged in antifascist musical propaganda. These included Hanns Eisler, Ernst H. Meyer, Ernst Busch, Grigori Schneerson, Ferencz Szabó and members of the Union of Soviet Composers. Mayer-Serra’s edition of the multi-volume Cançoner Revolucionari Internacional (International Revolutionary Songbook), a source moderately known among scholars today, is contextualized here for the first time as part of as part of broader, often Comintern-controlled, musico-propagandistic trends and discourses that circulated in Europe and the Soviet Union throughout the 1930s.

The article is the first to examine the production and reception in Spain of Communist antifascist propaganda songs during the Civil War from a perspective that takes into account the strongly transnational dimension of 1930s antifascism as well as the powerful movements of peripheral nationalism in Spain, in particular Catalan nationalism, in that decade. The study is part of a broader, recent surge of reflective discourses about music and war which have moved away from hagiographic and nation-centred paradigms and towards a more critical appraisal of war and antifascism as cultural systems that primarily operated across national boundaries in the 1930s.Footnote1

From ‘Red’ Berlin to Republican Barcelona

As was the case for many left-wing German intellectuals of his generation, the socio-economic difficulties and political confrontations in Germany during the Great Depression fuelled Mayer’s interests in Marxist philosophy and communism. Born in 1904 to a wealthy Jewish family in Berlin, he studied musicology at the Berlin University (1923–1926) and completed his doctoral studies at the Universities of Rostock, Cologne, and Greifswald (1926–1929). He defended his thesis analysing the ‘Romantic’ piano sonata genre in 1929. Between 1930 and his departure for Spain in mid-1933, Mayer published several essays on music in German musical journals closely aligned with the labour movement, conducted a workers’ choir in the Berlin suburb of Buch, and became closely acquainted with Hanns Eisler along with his Berlin circle of Marxist composers and musicologists. Eisler then represented the loudest voice in Germany for a new type of Kampfmusik (music for [class] struggle) in service to the labour movement; Eisler was also one of the most active advocates for the renewal of musicology through the application of dialectical materialism to the study of music. A key figure in Eisler’s circle was the composer and musicologist Ernst Hermann Meyer, who became a close friend of Mayer (Mayer-Serra, Citation1937b, Citation1937c). They shared not only the surname (spelled differently), but also a very similar personal, intellectual, and family background.

Eisler and Meyer were the most prominent members of the Kampfgemeinschaft der Arbeitersänger or KdA (Fighting Collective of Working-Class Singers). This ca. 4,000-member union of workers’ choral societies coalesced in 1931 as a communist splinter from the social democrat-dominated Deutscher Arbeiter-Sängerbund or DAS (German Workers’ Singers’ Federation). The ‘revolutionary’ KdA differed from the ‘reformist’ DAS in their much greater interests in politicizing music, rejecting the notion of music as a form of leisure, denouncing the traditional formal concert and its canonical repertoire as ‘bourgeois’ institutions, collaborating with agitprop groups, and attempting to bridge the gap between performers and audiences (Kaden, Citation1988: 24–54). The KdA encouraged the performance of specifically ‘proletarian-revolutionary Kampfmusik’, consisting primarily of newly composed Kampflieder and, less often, pieces of agitprop musical theatre, most notably Eisler and Bertolt Brecht’s Lehrstück (didactic work) Die Maßnahme (1930). Mayer’s experiences within Eisler’s circle and the KdA greatly influenced his thought.Footnote2

When Mayer arrived in Barcelona around May 1933, he lacked any significant ties to Spain other than his friendship with the Catalan politician Manuel Serra, who had helped him obtain a diplomatic Spanish passport, issued under the name ‘Odón Mayer Serra’ (Citation1933a). This was the first time that Mayer used the politician’s surname as his own. The circumstances of their acquaintance and the reasons for Manuel Serra’s support both remain undiscovered. Mayer-Serra’s choice of Barcelona as his place of exile was not due to any special fondness for Spain, but rather mainly on account of Serra’s assistance. Indeed, Mayer-Serra initially planned to move to the Soviet Union soon after: he wrote to his friend Meyer about three months after arriving, ‘Here [in Spain/Catalonia] it’s just a pile of rubbish you can’t take for more than 2 or 3 years’Footnote3 (Mayer-Serra, Citation1933c).

In the same letter, Mayer-Serra described the political context he encountered in Spain as ‘almost the same situation as two or three years ago in Germany, as social democracy collapsed; precisely the same nonchalance, tactical indecision, total dedication to small day-to-day achievements — in short, everything that, in our experience, we can only define as corruption’ (Mayer-Serra, Citation1933c). Mayer most likely alludes here to the March 1930 collapse of the German government, then an ideologically diverse five-party ‘Grand Coalition’ led by the Social Democratic Party, as a result of the Great Depression. Mayer-Serra explained in his letter that the Communist Party in Catalonia remained insignificant; the communist Bloque Obero y Campesino (Workers’ and Peasants’ Bloc) was larger and better organized than the Spanish Communist Party but opposed to the Communist International; ‘the people from the trade unions’ had ‘no idea about politics, much less Marxism.’ The only ‘guarantee of a revolution’ was Joan Comorera (1894–1958), ‘a real people’s leader [Volksführer] of almost brutal determination, […] he is like a sniffer dog, with tremendous courage, after every reactionary and anti-proletarian action … ’ (Mayer-Serra, Citation1933c).

Only shortly after his arrival in Barcelona Mayer-Serra was already closely linked to the Unió Socialista de Catalunya (Socialist Union of Catalonia) led by Comorera, in which Manuel Serra was also a party member. The party had been formed in 1923 by a split in the Catalan Federation of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE). It pursued a regional nationalist agenda (Alcaraz i González, Citation1987). In Spain, Mayer-Serra quickly adopted the political stance of Catalanisme, the idea that Catalonia constituted a cultural and political entity significantly different from the rest of Spain.

Political ‘activation’ through music

In Barcelona, Mayer-Serra immediately wanted to engage in ‘political activities’. Among his aspirations was organizing a lecture in autumn 1933 ‘about musical activation’ [Aktivierung der Musik], which would take place in an unspecified culture centre ‘attended by all strata of the working population: social democrats, anarchists and communists’. In this talk, he intended to play and discuss ‘many records of Lehrstück, unison song, opera for schools [Schuloper], political music, etc.’ (Mayer-Serra, Citation1933b). The notion of workers’ political ‘activation’ through music, set in contrast to the ‘passivity’ induced by bourgeois music, was typical for contemporary communist intellectual discourse (Kaden, Citation1988). Mayer-Serra also wanted to create a new workers’ choir and work with them ‘like in [Berlin-] Buch’. He therefore asked Meyer to send him handwritten copies of ‘all our unison songs’, so he could immediately translate and ‘completely reconfigure’ them (supposedly into Catalan) (Citation1933b). Mayer-Serra asked specifically for six Kampflieder that he remembered as particularly effective: Eisler’s ‘Kampflied für die IAH’ (Song of struggle for the Internationale Arbeiterhilfe, 1931), ‘Solidaritätslied’ (Solidarity Song, 1931) and ‘Der heimliche Aufmarsch’ (The Secret Deployment, 1930), Vladimir Vogel’s ‘Der heimliche Aufmarsch’ (1929), Ernst Hermann Meyer’s ‘Auf die Straße!’ (To the Streets!, 1932) and ‘maybe some of the Russian songs (‘Traktor’, etc.) and whatever else you can think of’ (Mayer-Serra, Citation1933b).Footnote4

Mayer-Serra finished his letter by telling his friend that he was also negotiating for the publication of a Spanish translation of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, which would consist of ‘excerpts [from Hitler’s book] compared to today’s reality, newspaper clippings, reports, legal texts, etc.’.

You see, I’m moving in all directions. I am fully aware that I am getting very much involved in politics and, as you know from your own activity, I will certainly also be involved in all kinds of controversies, here even more than in Berlin, but I believe I have no other choice. I would rather experience an end with horror in a few years than not be able to do anything in the meantime. (Mayer-Serra, Citation1933b)

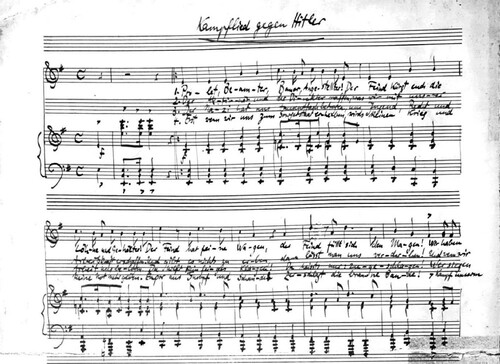

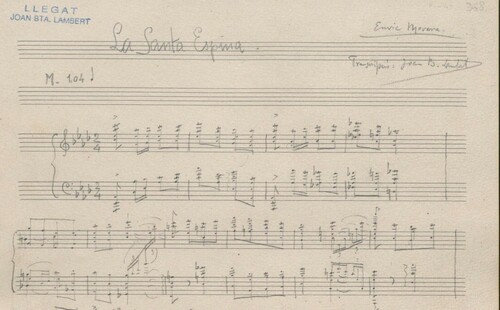

Meyer set these lyrics to music in Berlin in early 1933, shortly before fleeing into exile (Weiß Citation1976: 111). Like most unison Kampflieder composed in Germany in the last years of the Weimar Republic, the piece is simple, short (3–4 minutes long), and provided with piano accompaniment, which can be dispensed with if necessary or easily arranged for the available ensemble (). Stylistically, these marching songs are strictly syllabic for ease of text comprehension, and often include harmonic, rhythmic or structural features that slightly ‘modernise’ and differentiate them from military marches and earlier workers’ songs. These songs were easy to sing and remember, but generally avoided musical elements that obviously linked them with popular ‘light’ genres such as cabaret songs, Schlager, or ‘jazz’ (as understood in the broadest sense), which many of these composers considered vulgar and ‘bourgeois’.Footnote7

With the Kampflieder in hand, Mayer-Serra wrote back thankfully to Meyer that ‘I can now try to organise something here […] an extraordinarily impressive Montage can be made’ (Citation1933c). A ‘Montage’ was a type of performance put on in early 1930s German communist circles, consisting of a sequence of Kampflieder sung by a workers’ choir (often also joined by the audience) interspersed with short political speeches and sometimes instrumental pieces, short films or projected documentary images (Fuhr, Citation1977: 209, and Kaden, Citation1988: 149). Each Montage often dealt with a broad political topic or concept, such as ‘proletarian solidarity’. In the early 1930s, Eisler and other German communist musicians of his generation considered this type of performance to be a particularly effective and modern tool for the political education of workers. (Eisler, Citation1932, Citation1933).

In his second letter to Meyer in August 1933, Mayer-Serra stressed his need to ‘fight with all my strength for and against what is important to us’ in Spain. But he also uttered his doubts and fears, and some foreboding thoughts:

[…] this is what I am asking you here: in the face of a completely deadlocked situation [in Spain], in the face of all the symptoms that point to a not very distant collapse of the republican government and to a breakthrough of reactionary and clerical forces: should we once again engage with all the fire of our idealism and act as if this world could really be ours [communists’] soon? After all that we have been through, can we create a choir again and raise hopes and yearnings through our songs? In short, can we re-create that eschatological mood in which, if we are honest and if we interpret the symptoms correctly, we simply can no longer believe? You write that there is no more compromise and no more mercy. You talk about taking action and intervene in the world. What does the German collapse teach us if not that the commitment of so many individual militants cannot remedy the problem itself, because the objective situation simply passes over us. It is difficult for me to say this, but I have to ask you a very urgent question, and in a moment of joy I expect an equally urgent answer from you: Doesn’t it seem that in this time of the last desperate struggle of capitalism for its continued existence, our time has simply not yet come? Isn’t it a waste of precious energy when the communists in Germany now just let themselves be slaughtered? The slogan, however broadly interpreted, that a lost battle is better than no action at all, is really not enough here … Maybe you know the answer to this whole pile of pessimism. It probably won't prevent me from doing what I think deep down is wrong [i.e. communist activism] and from seeking political effectiveness here. (Mayer-Serra, Citation1933c)

The only aforementioned project that he did succeed in carrying out before the civil war was the lecture on music and politics, albeit only two years later than planned and in a less politicized manner than described in his letter to Meyer. In one of the six lectures on modern music that he gave at the cultural centre Ateneum Polytechnicum in the spring of 1935 entitled ‘Las inquietudes sociales a través de la música’ (Social concerns [expressed] through music), he discussed the ‘political music’ of Eisler, Weill and other left-wing German composers of his generation (Anon., Citation1935a, Citation1935b). The tone and content of this and other lectures in the pre-war period were moderate and restrained. It was not until the worker militias’ seizure of power at the beginning of the civil war that Mayer-Serra felt free to openly address issues directly related to communist ideology and proletarian revolution in his lectures and writings. It was also only then when he openly promoted the genre of Kampflieder as an instrument for propaganda. I refer to the Kampflieder composed, sung, recorded and published during the civil war as ‘battle songs’. In Spain this type of song was usually called ‘canciones de lucha’, ‘de guerra’ or ‘revolucionarias’ (songs of struggle, war-songs, revolutionary songs).

Anti-fascist musical propaganda

Mayer-Serra was closely linked to the Catalanist communist party Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSUC) since its foundation on 23 July 1936.Footnote8 His writings for the party’s official daily Treball (Work), for the ‘new’ Mirador (seized by the PSUC in September 1936) and for other music journals represent a significant facet of his activities during the civil war (Alonso, Citation2019). Similarly important was his intensive work for two Barcelona propaganda institutions: the Casal de la Cultura (House of Culture) and, in particular, the Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya (Propaganda Agency of the Catalan Government).

The Comissariat was created on 3 October 1936 as an autonomous organ within the Catalan Government. As the president of Catalonia Lluís Companys explained in 1937, its stated goal was ‘to maintain people’s enthusiasm [for the war effort] and contribute to the orientation of foreign opinion in favour of the anti-fascist cause’ (Companys, Citation1937). The term ‘propaganda’ was not yet identified with totalitarian demagoguery or psychological manipulation, but rather understood as a legitimate form of political communication inherent to political life (Miravitlles, Citation1937; see also Stanley, Citation2015 and Garratt, Citation2019: 107–27). The Comissariat organized a large number of propaganda activities, including political speeches, lectures, broadcasts, exhibitions, sports competitions, concerts, the publication of periodicals, books and scores, as well as the creation of posters, films, photographs, and musical works, among others (Venteo, Citation2006).Footnote9 Mayer-Serra retained a leading role in the music department (Iglesias, Citation1992: 73). He primarily edited musical scores for the Comissariat. His first and main project was the edition of a multi-volume Cançoner Revolucionari Internacional (International Revolutionary Songbook).

From the beginning of the war, those in charge of anti-fascist propaganda in Spain had sustained interest in the use of battle songs as instruments of propaganda. However, mainly due to the insignificance of communism in Spain before the second half of the 1930s, Spanish composers had composed relatively few explicitly political battle-songs of the type described above prior to the civil war. This pressing need for new propaganda songs caused the Republican press to call for composers to produce battle-songs. (Anon. [Mayer-Serra], Citation1936 and Anon. [Mayer-Serra], Citation1937a). The Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts organized a composition contest in mid-1937 to award a prize for the best new ‘war songs’, which would be ‘intensively disseminated’ through radio broadcast and live performances (Anon., Citation1937a, Citation1937b, Citation1937c). According to the communist composer Carlos Palacio, 117 songs were submitted (Citation1939: 68; Citation1984: 159). Six were given awards and subsequently published (Anon., Citation1937c, Citation1937d). No sources related to the 111 remaining songs have been found. Whether Palacio’s figure is accurate is uncertain.

Around January 1937 Mayer-Serra wrote to the Union of Soviet Composers in Moscow asking them to send him battle songs as well as essays on music for use as propaganda in Spain (Anon. [Mayer-Serra], Citation1937a). The Union was a division of the Soviet Ministry of Culture that controlled the activities of music professionals and mediated between its members and the Communist Party leadership (Tomoff, Citation2006; Nelson, Citation2020). The Moscow-based musicologist Gregory Schneerson and Hungarian composer Ferenc Szabó answered his letter on behalf of the association, thanking him for establishing contact. Apparently, Mayer-Serra was one of the main contacts between the Union and Spain. According to Mayer-Serra, the Soviet composers sent him ‘more than forty songs dedicated to our struggle for freedom’ (Citation1937d: 32), most of them with lyrics in Russian, a few with French and German lyrics (Anon. [Mayer-Serra], Citation1937a). Shortly thereafter, the Spanish music journal Música (one of the most prominent in wartime Spain) wrote that the Soviet composers and poets had created ‘approximately one hundred songs’ for the Spanish war and mentioned 16 titles and authors, including Viktor Tomilin’s ‘Canción de Dolores Ibárruri’ (Dolores Ibárruri Song), Samuil Feinberg’s ‘¡Al ataque, 5° Regimiento!’ (Attack, 5th Regiment!), Matbey Elanter’s ‘Saludo a los heroes’ (Hail to the Heroes) and Vadim Kochetov’s ‘Canción al general Lukacz’ (Song to General [Máté Zalka] Lukacz) (Anon., Citation1938a, Citation1938b). With the exception of Vadim Kochetov’s ‘¡No pasarán!’ (They Shall not Pass!), the manuscripts of these songs have not been found. The USC’s journal Sovetskaya muzika as well as the Schneerson’s papers kept at the Glinka State Central Museum of Musical Culture might shed light to the still less explored contribution of Soviet composers to Republican musical propaganda.

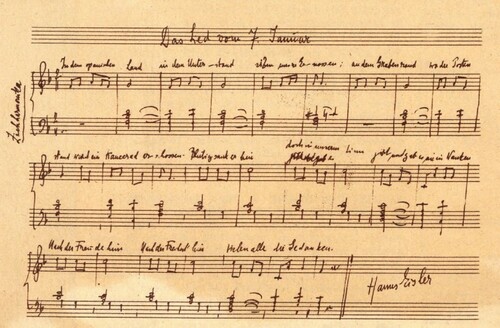

Their recognized need for new battle songs in Republican Spain appears to be the main reason for Eisler’s second visit to Spain in January 1937. In Madrid, Eisler apparently asked the communist poet José Herrera Petere to write new lyrics for the ‘Olympic march’ that he had composed for the ‘People’s Olympiad’ planned in Barcelona the previous spring as a protest against the official Olympic Games in Nazi-controlled Berlin. The new version was entitled ‘Marcha del Quinto Regimiento’ (March of the Fifth Regiment). Eisler also composed two new songs in Spain: ‘No pasarán’ after lyrics by Petere, and ‘Das Lied vom 7. Januar’ (The Song of January 7) after lyrics by Renn. Rather than a battle song of the type described above, the latter (scored for voice and squeezebox) is a lament for the death of virtually the entire Thaelmann Battalion on the Madrid front that day. This battalion consisted almost entirely of German-speaking international brigadiers. A few months later, Ernst Busch included this song in his songbook for the International Brigades ().

International and revolutionary

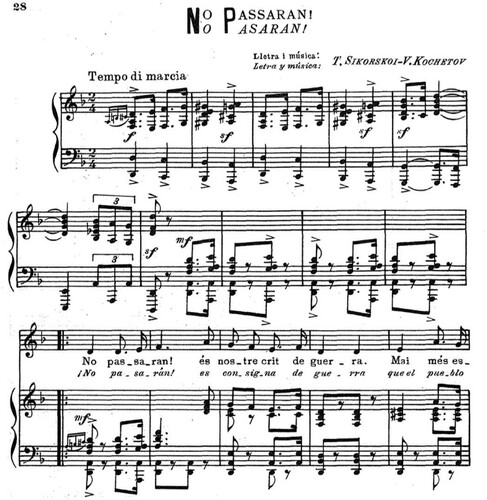

Kochetov’s ‘No pasarán’ was published in the summer of 1937 along with nine other unison songs for voice(s) and piano in the first volume of Mayer-Serra’s International Revolutionary Songbook. Mayer-Serra provided brief commentary for some songs. The volume’s contents are listed below with Mayer-Serra’s comments in bold, and the remainder paraphrasing the results of my own research. As in the other volumes, Catalan is the main language and Spanish is the secondary one.

‘Els segadors’ (The Reapers): significantly, the songbook opens not with the Spanish but rather the ‘Catalan national anthem’ (unofficial before 1993), whose lyrics (by Emili Guanyavents, 1899) ‘refer to the struggle for independence of the Catalan peasants against the invasion of the Castilian army of King Philip IV’. The vocal line is by the Catalan composer Francesc Allió (1892) after a seventeenth century Catalan folk song. (See Massot i Muntaner et al. Citation1993).

‘La Internacional’ (The Internationale): An extremely popular anthem for the socialist workers movement and left internationalism as well as the national anthem of the Soviet Union at the time. Original French lyrics by Eugène Pottier (1871), melody by Pierre Degeiter (1888). The song was provided with new Catalan and Spanish lyrics concerning war (authors unknown)

‘Les barricades’ [sic] (The Barricades): Spanish version of the Polish workers song Warszawianka (lyrics by Wacław S´więcicki, music by Józef Pławiński, both c. 1880s). The Spanish lyrics were written in the early 1930s by the anarcho-syndicalist writter Valeriano Orobón Fernández, most likely taking the German version as source. The song became the hymn of the Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist labour unions Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT). It was particularly popular as an ‘anarchist hymn’ during the Civil War. Author of the Catalan lyrics unknown. (See Baxmeyer, Citation2016).

‘Marxa de l’exèrcit popular’ (March of the Popular Army). Stylistically, this song is close to the German Kampflieder of the early 1930s. The composer is unknown. The Catalan (and Spanish?) lyrics were written in late 1936 or early 1937 by the poet Joan Oliver i Sallarès (see Pujol, Citation2006a: 66). Regular mentions in the Catalan press suggest that the song was relatively popular in wartime Catalonia.

‘Terra lliure’ (Free Land). Spanish and Catalan version of Erich Weinert’s and Ferenc Szabó’s ‘Wolga-Lied’ (a.k.a. ‘Rotes deutsches Wolgaland’). It was composed between 1927 and the mid-1930s. Catalan lyrics: Salvador Perarnau. Spanish lyrics: Domènec Perramon. ‘Harmonization by C. Bernat’ (German composer Konrad Bernhard, then living in exile in Barcelona).

‘La jove guàrdia’ (The Young Guard): French socialist song ‘La Jeune Garde’. Lyrics by Montéhus (Gaston Mardochée Brunswick); music by a one Saint-Gilles (1912) (Brécy, Citation1978: 204). Les Jeunes Gardes Socialistes were created in 1886 by the Section française de l’Internationale ouvrière. This song was the anthem of the young organization of the Spanish Communist Party. Spanish and Catalan lyricist(s) unknown. ‘Harmonization by [Spanish composer] Tomás Mancisdor’.

‘Marxa funebre’ (Funeral March): nineteenth century Russian song, popular in the Soviet Union. Authorship uncertain. A popular German version exists with lyrics by German conductor Hermann Scherchen entitled ‘Unsterbliche Opfer’ (see John, Citation2018: 45–53). Mayer–Serra possibly took that version as his source.Footnote10

‘Davant la vida’ (In Pursuit of Life). Title-song of Sergei Yutkevich and Fridrikh Ermler’s Soviet film Counterplan (1932). The film celebrated the 15th anniversary of the Russian Revolution (Riley, Citation2004). Russian lyrics: Boris Kornilov, music by Dmitri Shostakovich, 1932. Catalan: Salvador Perarnau. Spanish: Domènec Perramón.

‘Himno nacional mexicano’ ([Official] Mexican national anthem): Lyrics by Francisco Gonzalez Bocanegra (1853), music by Jaime Nunó (1854). Mexico was, along with the Soviet Union, the only country that supported the Spanish Republic during the civil war.

‘No passaran!’ (They shall not pass!): Original (Russian?) lyrics by Tatyana Sikorskaya (a.k.a. Sikorskoi). Music by Vadim Kochetov. Late 1936 or Early 1937. Author(s) of the Catalan and Spanish lyrics unknown.

In September 1937, the composer Enrique Casal Chapí (1909–1977) reviewed the volume for the renowned journal Hora de España. This was the only review of substance published in this time. The songbook raised fundamental questions, the answer to which, Chapi wrote, were pressing for wartime Spain: how can composers of ‘serious music’ collaborate with the ‘world revolutionary [communist] movement’? Should they write battle songs and ‘mass music’ in the complex style they use for ‘serious’ (e.g. symphonic) music or in a more popular and simpler style? Should they forget every national trait when writing battle songs for the international anti-fascist movement? The answer, he pointed out, had been provided by the Soviet songs included in Mayer-Serra’s songbook. From the ‘unnatural’ ‘Terra Lliure’ to the ‘truly mediocre’ ‘Joven Guardia’, ‘Marcha del Ejército Popular’ and ‘Himno Nacional Mexicano’ — all ‘full of the worst remnants of the worst nineteenth century music’ — Casal Chapí contrasted the superbly composed Soviet songs, in particular Kochetov’s ‘straightforward and powerful’ ‘No pasarán’ (). This song was ‘full of rhythmic force and harmonized with a truly remarkable precision and interest’. Casals Chapí hoped that Spanish composers would be soon able to create similar simple and popular songs that were modern and far removed from the vulgarity of light music.Footnote11

The second volume of Mayer-Serra’s International Revolutionary Songbook was published in early December 1937. Most songs included were recently created by composers from Spain and abroad who were supportive of communism. Five songs were composed specifically for use as propaganda in Spain. The journal Música described the volume as a ‘historical record’ in the field of ‘revolutionary music’ (Anon., Citation1938b). The book included:

‘Himno de Riego’ ([Rafael del] Riego’s Hymn): Spanish national anthem during the Liberal Triennium (1820–1823), the First Republic (1873–1874) and the Second Republic (1931–1939). Lyrics possibly by Evaristo Fernández de San Miguel (c. 1820). The composer remains undetermined (Tellez Cenzano, Citation2016).

‘Mexico en España’ (Mexico in Spain): Lyrics by Pascual José Plá y Beltrán. Music by Silvestre Revueltas (Madrid, 17/09/1937). Palacio stated that this song was dedicated to ‘the Mexican fighters in Spain and the Colonel Juan B. Gómez’ (Citation1939: 32). According to Velasco-Pufleau (Citation2013), this was the anthem for the Mexican delegation of the League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists in Spain.

‘Marcha del 5° Regimiento’ (March of the Fifth Regiment): Music by Hanns Eisler (ca. May 1936 as ‘March of the People’s Olympiad’). Lyrics by José Herrera Petere (January 1937). The Fifth Regiment was a military unit founded by the Spanish Communist Party and the Marxist-Leninist youth organization Juventudes Socialistas Unificadas.

‘Las compañías de Acero’ (The Steel Companies): Lyrics by Luis de Tapia (1936). Music by Carlos Palacio (Late 1936). This song was popular during the war in Republican Spain. Ernst Busch recorded it in Barcelona. The song was published and became relatively popular in the Soviet Union. The ‘steel companies’ were military units within the Fifth Regiment. (Palacio, Citation1984: 134–6 and Anon., Citation1938b).

‘Alerta’ (Alert): Hymn of the youth organization ‘Escuelas Alerta’, which provided premilitary training to children through sport activities. Spanish lyrics by Felix V. Ramos, music by Rodolfo Halffter (1937). Catalan lyrics: Lluís Ensenyat.

‘Cant a la Joventut’ (Hymn to Youth): Popular song in the Soviet Union as ‘Широка страна моя родная’ (‘Wide is my motherland’). Lyrics by Vasily Lebedev-Kumach. Music by Isaak Dunayevsky. Written for Grigori A Aleksándrov’s 1936 Soviet musical film Цирк (Circus). Spanish lyrics by Felix V. Ramos; Catalan by Lluís Ensenyat. This song, along with ‘La Joven Guardia’ and ‘Alerta’, was apparently sung by children at some festivals, in the colonies and at parades during the war (Lapeyre, Citation2010: 5).

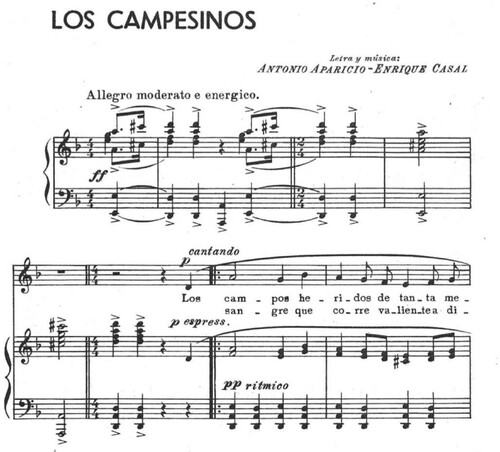

‘Los campesinos’ (The Peasants): Lyrics by Antonio Aparicio. Music by Enrique Casal Chapí (Citation1937). See Palacio Citation1939: 56.

‘Hijos del Pueblo’ (People’s Children): Popular anarchist Spanish song from the 1880s. Lyrics possibly by the Spanish typographer Rafael Carratalá. Composer uncertain. (Baxmeyer, Citation2016).

‘La Comintern’. Anthem written in 1929 by Franz Jahnke, Maxim Vallentin (lyrics) and Hanns Eisler (music) for a celebration of the 10th anniversary of the International Communist (Schebera, Citation1998, 58–9; Gall, Citation2018: xxix, xxxii). Spanish lyrics by Salvador Chardí Rusies (early 1930s). Author of the Catalan lyrics unknown.

‘Canço del Front Popular’ (Song of the Popular Front): Catalan and Spanish versions (by Lluís Ensenyat and Felix V. Ramos respectively) of Brecht & Eisler’s ‘Einheitsfrontlied’ (1934). (On ‘Einheitsfrontlied’ see Grabs, Citation1975; Fasshauer, Citation2005 and Heister, Citation2006). The source for Mayer-Serra’s edition of ‘Kominterlied’ and of ‘Einheitsfrontlied’ were the Soviet editions of 1931 and 1936 respectively.Footnote12

Casal Chapí’s ‘Los campesinos’ was one of the Spanish battle songs that Mayer-Serra and Meyer (who obtained a copy of the songbook from Mayer-Serra) appreciated especially. (Mayer-Serra, Citation1938c). Antonio Aparicio’s lyrics, written in the first months of the war, call for the peasantry to ‘abandon the plow’ and ‘march with manly vigor into the trenches’ (peasants then formed a sizable portion of Spain’s largely agrarian society). Casal Chapí set the lyrics to music in 1937 in Madrid (Palacio, Citation1939: 56). He emulated a number of novel features in Eisler’s ‘Solidaritätslied’, including three-bar phrasing and shifts in time signature. The song was first recording by German singer Ernst Buch in Berlin shortly after the Second World War, then repurposed to serve other political ends (Leenders & Meyer-Rähnitz, Citation2005: 23–5) ().

Mayer-Serra worked on a third volume which in the end went unpublished, possibly due to the Comissariat’s (or, more generally, the Republic’s) financial problems by the spring of 1938. The back cover of the second volume preserves a list of the song titles intended for inclusion in the third volume (Mayer-Serra, Citation1937e: 33):

‘La Santa Espina’ (The Holy Thorn): Popular sardana from the eponymous zarzuela. It was considered a Catalanist anthem at the time, due primarily to the affirmative, combative lyrics: (‘We are and will be Catalan people, whether it is wanted or not […]’). Catalan lyrics by Àngel Guimerà. Music by Enric Morera (1907).

‘Guernikako Arbola’ (The Tree in Guernika): Zortziko song (in 5/8 time signature). Unofficial anthem of the Basques. Music and lyrics by Jose María Iparragirre (1853).

‘La Marsellesa’: French revolutionary song and the French national anthem since 1795. Music and lyrics by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, 1792.

‘Cançó de la revolució xinesa’ (Song of the Chinese Revolution): Unknown

‘Bandiera Rossa’ [sic] (‘Red Flag’): A popular song among the Italian labour movement. The melody is derived from two Lombard folksongs. Lyrics by Carlo Tuzzi (early twentieth century).

‘Marxa dels Aviadors’ (March of the Aviators): Unknown. Either a newly composed song or, more likely, a Spanish / Catalan version of ‘Rote Flieger’ (Red Airmen), a popular song in Weimar Germany, with lyrics by Helmut Schinkel and music by Julius Chait. (Lammel, Citation1980: 170).

‘Als camps de concentració’ (In the Concentration Camps): Unknown. Possibly ‘Die Moorsoldaten’, a song composed in 1933 by prisoners held in a Nazi concentration camp and set in a version by Eisler for Busch in 1935. (Probst-Effah, Citation2009).

‘Canço del S. R. I.’ (S. R. I. Song): Acronym for the Comintern-organization Socorro Rojo Internacional (International Red Aid). Most likely a newly composed song, now lost.

‘U. H. P’: Acronym for the Unión de Hermanos Proletarios (Proletarian Brothers’ Union), a broad alliance of labour parties and organizations created during the 1934 revolution in Asturias. The acronym was a popular battle cry during the civil war. Three songs exist with this title.

One of the songs awarded a prize in the aforementioned battle-song contest (lyrics: Alberto Alcantarilla Carbó; music: Francisco Merenciano Bosch);

The Spanish version of ‘Brüder, zur Sonne, zur Freiheit’, a Soviet song particularly popular in Weimar Germany with lyrics by Hermann Scherchen and included in Ernst Busch’s songbook (Busch, Citation1937; see John, Citation2018);

A song by Vicente Pérez Galeote (lyrics) and Manuel Ramos (music), published in Moscow in 1938 in the songbook ‘Pasaremos!’ (on which I delve below).

‘Canción de la Solidaridad’ (Solidarity Song): Lyrics by Bertolt Brecht, music by Eisler (1931). Written for the film Kuhle Wampe oder Wem gehört die Welt? Particularly popular in left-wing circles at the time. Published by Universal Edition in 1932.

The songs included in the three volumes of Mayer-Serra’s International Revolutionary Songbook can be classified in three broad types: (1) ‘traditional’ (mostly mid-to-late nineteenth century) left-wing workers’ songs, including two anarchist songs; (2) newly composed songs (dating from between 1928 and 1937), mainly by Spanish, Soviet, or German authors who supported communism; (3) national anthems — or songs functioning as such — representing Catalonia, Spain, the Basque country, France, the Soviet Union and Mexico. These national anthems were equally understood at the time as leftist songs. Some songs belonging to type 1 and 2 were also indirectly linked to the anti-fascist movements of particular nations (e.g. ‘Bandiera rossa’ for Italy, or Eisler’s ‘Solidaritätslied’ for Germany). The function of Mayer-Serra’s songbooks was thus to highlight four related ideas: (1) the internationalism of the workers’ movement and of antifascist struggle, including in Spain; (2) the need to unite all left-wing forces (including anarchism) to defend the Spanish Republic (and the Western world) from fascism; (3) the centrality of communism (and the Communist International) in that struggle; (4) the territorial and political pluralism of Spain, in particular the national and cultural distinctiveness of Catalonia. The inscriptions ‘Made in Catalonia’ (vol. 1) and ‘Made in Spain’ (vol. 2) suggest that the songbooks were distributed, or intended to be distributed, abroad. To which countries, and how they were received there, remains unknown.

Wartime musical Catalanisme

In 1938 the Soviet musicologist Grigori Schneerson published in Moscow a songbook entitled Canciones de guerra. Испанские революционные песни. Pasaremos! (War-songs. Spanish Revolutionary Songs. We Shall Pass!). This songbook was similar in content and format to Mayer-Serra’s. It included Spanish and Russian versions of ‘Himno de Riego’, ‘Hijos del Pueblo’, ‘Juventudes Proletarias’, ‘Los Campesinos’, ‘Los cuatro generales’, ‘Bandera roja’, ‘Unión de Hermanos Proletarios’, ‘¡Alerta!’ and ‘Las compañías de acero’. Schneerson used Mayer-Serra’s songbooks as the source for the editions of the songs underlined above (Schneerson, Citation1938a). It is uncertain whether Mayer-Serra was directly involved in Schneerson’s publication. Schneerson’s songbook was part of the domestic Soviet propaganda campaign in support of the country’s intervention in the Spanish civil war. The songbook makes no allusions to Catalonia or any other Spanish region. ‘Hijos del pueblo’ is included in the book, but Schneerson, unlike Mayer-Serra (Citation1937e: 25) and Busch (Citation1937: 14–5), does not mention the song’s affiliation with anarchism and changed the original lyrics as follows: ‘In the battle, the fascist hyena / by our effort will succumb / And the whole People with the anarchists communists / will make freedom triumph!’ (‘En la batalla la hiena fascista / Por nuestro esfuerzo sucumbirá / Y el pueblo entero con los anarquistas comunistas / Hará que triunfe la libertad!’).

Schneerson’s songbook also included ‘Los cuatro generales’ (The Four Generals), a contrafactum of the Andalusian folksong ‘Los cuatro muleros’ (The Four Muleteers). This is one of several triple-meter folksongs from Southern Spain, which became notably popular in wartime Spain after being provided with new lyrics about war at the beginning of the conflict. Other examples are ‘El tren blindado’ (contrafactum of ‘Anda, jaleo’) or ‘El Quinto Regimiento’ (contrafactum of ‘El Vito’ and ‘Anda, jaleo’). Unlike Busch (Citation1937), Schneerson (Citation1938b), and Palacio (Citation1939), Mayer-Serra did not include any of these contrafacta in his songbooks. I hypothesize that he, and more generally, the Comissariat, considered the exoticist view of Spain conveyed by these Andalusian songs through established topoi (including rhythmic structures drawing on triple-meter dances, Phrygian motives, Andalusian cadences, hemiola patterns and floreos or ‘Spanish’ mordents) inconsistent with the notion of proletarian internationalism on the one hand and the image of Catalonia as a region, or nation, significantly different from the rest of Spain ().

FIGURE 5 Beginning of ‘Los cuatro generales’ as published in Schneerson’s songbook (Arragend by Kochetov).

In fact, the Comissariat made numerous efforts to promote the recognition of Catalonia as a distinct linguistic, cultural and national entity at home as well as abroad. In the field of music, these included the publication of a songbook including 10 Catalan folksongs (Comissariat, Citation1938a) and a Dutch version of ‘Els Segadors’ for distribution in their Flemish-speaking region (Mayer-Serra, Citation1938b; Comissariat, Citation1938b). Mayer-Serra also wanted to publish a collection of Catalan children’s songs with lyrics by the renowned Catalan poet Josep Carner and music by Josep Valls. The project did not come to fruition. (Mayer-Serra, Citation1937b, Citation1937c). Another unrealized project was a planned publication of collected piano sardanas, which was meant to include a ‘brilliant’ fantasia on Enric Morera’s ‘La santa espina’ by the Barcelona composer Juan Bautista Lambert, a ‘modernist’ sardana by the Majorcan composer Baltasar Samper and an ‘emancipated’, ‘contemporary’ sardana by Josep Valls (Mayer-Serra, Citation1938a). ‘The idea’ — Mayer-Serra wrote to Valls — ‘is to do for [the sardana] what Falla had done for the Andalusian song, Bartók for Hungarian music and previously, within the style of their time, Albéniz and Granados’ (Mayer-Serra, Citation1937b). A copy of Lambert’s fantasia on ‘La santa espina’ has been kept (Lambert, Citationn.d.). The piece is written in a Lisztian virtuoso style which Mayer-Serra disliked (Alonso, Citation2019). It is uncertain whether Samper, Valls and Rodolfo Halffter (whom Mayer also asked to collaborate in this project) actually composed sardanas for piano. Some reasons for the failure of these projects might include the Comissariat’s mounting financial difficulties in 1938, a growing sense of hopelessness regarding the outcome of the war, and perhaps the composers’ lack of personal interest. ().

Music as weapon

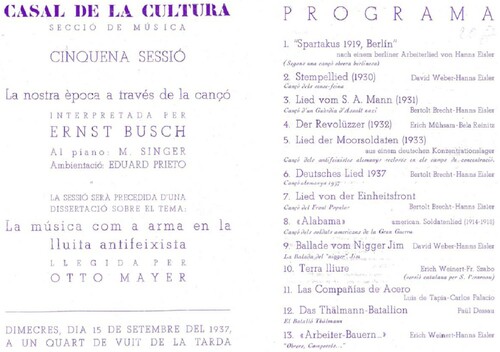

In April 1937, Mayer-Serra was appointed ‘secretary of propaganda’ for the music department of the Barcelona cultural institution Casal de la Cultura. He also belonged to the department’s executive committee. The Casal had been created in January 1937 modelled on the Parisian Maison de la Culture. The Casal’s efforts included exhibitions, film screenings, educational courses, book launches, concerts, lectures, and other events (Campillo, Citation1994: 155–81; Boquera Diago, Citation2015; Pujol, Citation2006a and Citation2006b). Mayer-Serra wrote and read aloud a manifesto at the inauguration of the music section, wherein he emphasized that their main objective was the elimination of the barriers between (art-)music and the people (Anon., Citation1937a).Footnote13 With the exception of the composer Baltasar Samper, the music writer Joaquim Pena and Mayer-Serra, the musicians involved with the music department were lesser-known figures. Apparently, the main (or only) activities organized by the music department specifically were lectures on music and concerts, mostly of chamber works belonging to the Western (primarily German and French) canon. The concerts occasionally included premieres of Catalan non-political contemporary music, such as Josep Carner and Josep Valls’ set of 14 songs for voice and piano ‘La inútil ofrena’ (The Useless Offering) on 9 October 1937 (Anon., Citation1937g).

There was at least one exception to Casal’s habit of programming art-music concerts without engaging explicitly political music, namely the concert on 15 September 1937 by German singer Ernst Busch, accompanied at the piano by composer Max Signer. The concert was announced in the press as ‘an insight into a truly revolutionary conception of music’, which was ‘almost unknown in Catalonia’ (Anon., Citation1937f). Mayer-Serra opened the concert with a lecture entitled ‘Music as weapon in anti-fascist struggle’ (Anon., Citation1937e). The slogan, music as weapon (or, more generally, culture as weapon), was common among leftist intellectuals at the time (Anon., Citation1931, Meyer, Citation1979: 109; John, Citation1994: 313). The manuscript of Mayer-Serra’s lecture is lost. It remains unknown whether his lecturing on anti-fascist music remained a one-off or became a regular activity during the war. Whether Busch further collaborated with Mayer-Serra or with the Casal de la Cultura is also uncertain.Footnote14

Busch wrote that he sang more than forty concerts and performed almost weekly on the radio during his 16-month stay in Republican Spain, from March 1937 through July 1938. Moreover, he recorded three records including six battle songs by different composers, including Eisler, Palacio, Paul Dessau and himself. ‘Los cuatro generales’ was included in these recordings (Leenders Meyer-Rähnitz, Citation2005: 210).Footnote15 No detailed study of these activities has been completed as of this time. Besides the event at the Casal, I have found evidence of two further concerts: one on 21 August 1937 at the Valencia Conservatory in homage to the International Brigades, which opened with a short lecture by Carlos Palacio (Anon., Citation1937e), and another on 6 February 1938 at the Club Internacional Antifascista in Barcelona, in which Erich Weinert read ‘antifascist poems’ and a number of people gave political speeches. (Anon., Citation1938c). The program of the Casal concert reproduced above is seemingly the only one kept of Busch’s concerts in Spain. He sang 13 songs, almost all written by communists, more than half by Eisler. I infer that the programs of most Busch concerts and radio performances in Spain were similar to this one. If this is true, then these events would have been the most important channel through which Eisler’s music was received in wartime Spain. ().

Conclusion

The beginning of the civil war was a major turning point in Mayer-Serra’s career in Spain. From being a rather isolated, marginal and independent figure within Spanish musicological circles he went on to occupy key position within several Republican propaganda institutions, to write regularly on music from an openly Marxist and class-conscious perspective for important journals, to intensively promote the use of Kampflieder as one of the most effective forms of antifascist musical propaganda, and to play a central role within the transnational, often Comintern-controlled network of musicians who were actively involved in antifascist propaganda in support of the Republic. The significance of this network and their members’ creative efforts has been often neglected in former studies of musical propaganda in the civil war. We lack a systematic catalogue of the battle songs created by mostly German, Spanish and Soviet authors for propagandistic use in the Civil War as well as detailed studies of the uses of these songs in Spain and abroad (in particular in the Soviet Union). This is remarkable considering that the Spanish war was one of the first armed conflicts in which music broadcast on the radio and in public spaces over huge sound systems (which apparently often included battle songs) played a central role in terms of propaganda and psychological warfare. The study of the creative efforts and diverse political creeds of the antifascist composers, editors and performers active within this network (including their different, often conflictive positions with regard to Stalin’s repressive policies of the time) is key to understanding the transnational dimension of musical propaganda during the Spanish civil war.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Peter Deeg, Tobias Fassauer, Johannes C. Gall and the anonymous peer-reviewers of the article for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this study. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Diego Alonso

Diego Alonso studied Musicology at the Complutense University of Madrid. He received his PhD in 2015 from La Rioja University with a thesis on Arnold Schoenberg’s influence on the music and thought of Roberto Gerhard. He has been a visiting scholar at Humboldt University in Berlin, at the University of Cambridge, at Goldsmiths, University of London and the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung (Berlin). Currently, he works at Humboldt University as the principal investigator in the project ‘Hanns Eisler in Republican Spain’. He is founder and leader (Sprecher) of the study group ‘Deutsch-Ibero-Amerikanische Musikbeziehungen’ of the German Musicological Society. He has published in leading musicology journals including Acta musicologica, Twentieth-Century Music, Music Analysis, and Musicologica Austriaca (Best Paper Award 2019).

Notes

1 For a summary of recent approaches to and theoretical developments in the study of music, war and propaganda in the 20th century see Morag Citation2020; Garratt Citation2019 (in particular chapters 2–4) and Fauser Citation2013.

2 On Mayer-Serra’s life, work, and thought before 1939 see Alonso Citation2019. On the KdA see Lammel Citation1974. For an insider’s perspective on the KdA, see Eisler Citation1934 and Meyer Citation1964.

3 All translations the author’s.

4 By ‘Traktor’ Mayer may refer here to the ‘Traktoristenlied’ (Tractorists’ Song) by the lyricist H. W. Willers and composer Anton Lebedynez or to ‘Traktorlied’ (this was a contrafactum of ‘In einer Meierei’, particularly popular within the revolutionary children's movement in Germany).

5 The colors of the ‘Third Reich’ heraldry but also of the ‘Kampffront Schwarz-Weiß-Rot’, an electoral alliance formed on 11 February 1933 by different conservative parties.

6 References to German businessman Franz Thyssen (1873–1951) and Prince August Wilhelm of Prussia (1887–1949), nicknamed ‘Auwi’. Both supported National Socialism in 1933.

7 On the compositional features of Eilser’s Kampflieder see Brinkmann Citation1971; Csipak Citation1975; Heister Citation2006; Glanz Citation2008; and Fassauer Citation2019. Meyer’s Kampflieder have not been analyzed in detail so far.

8 The history of the PSUC is discussed in Puigsech Farràs Citation1999.

9 The Comissariat’s history is discussed in Boquera Diago Citation2015 and Pascuet Citation2006.

10 On Scherchen and Mayer-Serra’s close relationship in Berlin see Alonso Citation2019.

11 The Mexican composer Silvestre Revueltas, in Spain from mid-July to mid-October 1937, most likely knew of Kochetov’s song through Mayer-Serra’s songbook. Revueltas arranged it for 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba and military drum, either during his stay in wartime Spain or shortly thereafter (Teibler-Vondrak Citation2011, p. 313).

12 КОМИНТЕРН, Moskau: Muzgiz 1931; Einheitsfrontlied. Moscow: Staatlicher Musikverlag, 1936.

13 On the Casal’s music department see Prieto Citation1937, Calmell Citation2007–2008.

14 See the File of the executive committee of the International Communist, S. 41 (RGASPI 495_205_2727). I thank Cristoph Kugler for providing me with a copy of his document

15 On Busch’s activities in Spain see Busch Citation1938, Siebig Citation1980, Hoffman & Siebig Citation1987, Leenders and Meyer-Rähnitz Citation2005 and Voigt Citation2010.

References

- Alcaraz i González, R. 1987. La Unió Socialista de Catalunya (1923–1936). Barcelona: Edicions de la Magrana Institut Municipal d’Història (Ajuntament de Barcelona).

- Alonso, D. 2019. From the People to the People: The Reception of Hanns Eisler’s Critical Theory of Music in Spain through the Writings of Otto Mayer-Serra, Musicologica Austriaca [online]. Available from: http://www.musau.org/parts/neue-article-page/view/76 [Accessed 16 March 2021].

- Anon. 1931. Ein Wort an die Arbeitermusiker. Kampfmusik, year 1, n. 3, p. 2.

- Anon. 1935a. Cursillo musical. La Vanguardia, 24 February, p. 12.

- Anon. 1935b. Ateneu Polytechnicum. El Jazz en la música moderna i l’Opera de Quat’Sous. La Publicitat, 4 April, p. 7.

- Anon. 1937a. La constitució de la Secció ‘Música’ del Casal de la Cultura, Mirador, 418, 29 April, p. 8.

- Anon. 1937b. Órdenes. Gaceta de la República, n. 204, 23 July, pp. 321–2.

- Anon. 1937c. [No title]. Gaceta de la República, n. 264, 21 September, p. 1163.

- Anon. 1937d. Seis canciones de guerra. Barcelona: Ministerio de Instrucción Pública (December).

- Anon. 1937e. Casal de la cultura’s concert programme, 15 September (The author’s personal archive).

- Anon. 1937f. Canciones de guerra. La Vanguardia [Barcelona], 15 September, p. 2.

- Anon. 1937g. La inútil ofrena. La Vanguardia [Barcelona]. 12 October, p. 2.

- Anon. 1938a. Bibliografia. Música, 1, January, p. 57.

- Anon. 1938b. Los músicos extranjeros a favor de España. Música, 1, January, p. 55.

- Anon. 1938c. Club Internacioal Antifaxista, Treball, 4 February, p. 4.

- Anon., [Mayer-Serra, O.]. 1936. Eduard Toldrá, el gran compositor catalán se ha alistado a las rengles de las milicias. Treball, 1 September, p. 6.

- Anon. [Mayer-Serra, O.]. 1937a. Els músics soviètics donen l’exemple. Mirador, 411, 19 February, p. 9.

- Baxmeyer, M. 2016. A las barricadas, Hijos del pueblo. Dos himnos libertarios como concretización de la utopía revolucionaria cultural del anarquismo ibérico. In: C. Collado Seidel, ed. Himnos y canciones. Imaginarios colectivos, símbolos e identidades fragmentadas en la España del siglo XX. Granada: Comares, pp. 65–80.

- Boquera Diago, E. 2015. La batalla de la persuasió durant la Guerra Civil. El cas del Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat Catalunya (1936–1939). Thesis (PhD). Universitat Ramon Llull.

- Brécy, R. 1978. Florilege de la chanson révolutionnaire de 1789 au front populaire. Paris: Hier et Demain.

- Brinkmann, R. 1971. Kompositorische Maßnahmen Eislers. In: R. Stephan, ed. Über Musik und Politik. Mainz: Schott’s, pp. 9–22.

- Busch, E. 1937. Kampflieder der Internationalen Brigaden. Madrid: Diana (UGT).

- Busch, E. 1938. Letter to Schneerson, 19 May. Archiv der Akademie der Künste, Ernst Busch Archiv, Cat. Number 2218.

- Calmell, C. 2007–2008. Barcelona, 1938: una ciutat ocupada musicalment. Ponència llegida al Congrés Barcelona, 1938. Recerca Musicològica, XVII–XVIII, pp. 323–44.

- Campillo, M. 1994. Escriptors catalans i compromis antifeixista (1936–1939). Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

- Casal Chapí, E. 1937. Cancionero Revolucionario Internacional. Hora de España, 9:72–6.

- Comissariat de Propaganda. 1938a. Cançoner Popular Internacional. Barcelona: Comissariat de Propaganda.

- Comissariat de Propaganda. 1938b. Cobla Catalunya. Barcelona: Comissariat de Propaganda.

- Companys, Ll., 1937. [No title]. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya [Barcelona], n. 260, 17 September, p. 1162.

- Csipak, K. 1975. Probleme der Volkstümlichkeit bei Hanns Eisler. München-Salzburg: Emil Katzbichler.

- Eisler, H. 2007 [1932]. Neue Methode der Kampfmusik. In: Tobias Fasshauer & Günter Mayer, eds. Hanns Eisler: Gesammelte Schriften, 1921–1935. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, pp. 155–6.

- Eisler, H. 2007 [1933]. Les experiences du mouvement musical ouvrier in Allemagne. In: T. Fasshauer & G. Mayer, eds. Hanns Eisler: Gesammelte Schriften, 1921–1935. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, pp. 181–5.

- Eisler, H. 2007 [1934]. Geschichte der deutschen Arbeitermusikbewegung seit 1848. In: T. Fasshauer & G. Mayer, eds. Hanns Eisler: Gesammelte Schriften, 1921–1935. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, pp. 191–203.

- Fasshauer, T. 2005. Zur Krise der Volkstümlichkeit bei Hanns Eisler. In: Matthias Tischer, ed. Musik in der DDR. Beiträge zu den Musikverhältnissen eines verschwundenen Staates. Berlin: Ernst Kuhn, pp. 26–49.

- Fasshauer, T. 2019. Fesche Märsche. Hanns Eisler und die Militärmusik. Eisler-Mitteilungen, 67:4–18.

- Fauser, A. 2013. Sounds of War. Music in the United States during World War II. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fuhr, W. 1977. Proletarische Musik in Deutschland (1928–1933). Göppingen: Alfred Kümmerle.

- Gall, J.C. 2018. Hanns Eisler. A-cappella-Chöre 1925–1932. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel.

- Garratt, J. 2019. Music and Politics. A critical introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Glanz, C. 2008. Hanns Eisler. Werk und Leben. Vienna: Steinbauer.

- Grabs, M. 1975. Über Berührungspunkte zwischen der Vokal- und der Instrumentalmusik Hanns Eislers. In: Manfred Grabs ed. Hanns Eisler heute. Berichte – Probleme – Beobachtungen. Berlin: Akademie der Künste der DDR, pp. 122–4.

- Heister, H.-W. 2006. Brecht / Eisler. Das Einheitsfrontlied. In: T. Phleps & W. Reich, eds. Vom allgemeingiiltigen Neuen Analysen engagierter Musik: Dessau, Eisler, Ginastera, Hartmann. Saarbrücken: Pfau, pp. 91–102.

- Hitler, A. 1935. Mi lucha. Barcelona: Casa Editorial Araluce.

- Hoffman, L. & Siebig, K. 1987. Ernst Busch. Eine Biographie in Texten, Bildern und Dokumenten. Berlin: Das Europäische Buch.

- Iglesias, A. 1992. Rodolfo Halffter (tema, nueve décadas y final). Madrid: Fundación Banco Exterior.

- John, E. 1994. Musikbolschewismus. Die Politisierung der Musik in Deutschland 1918–1938. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.

- John, E. 2018. Brüder, zur Sonne, zur Freiheit. Die unerhörte Geschichte eines Revolutionsliedes. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag.

- Kaden, W. 1988. Signale des Aufbruchs. Musik im Spiegel der „Roten Fahne“. Berlin: Neue Musik.

- Lambert, J.B. n.d. La Santa espina. Handwritten score. Fons Joan Baptista Lambert i Caminal. Centre de documentació de l’Orfeó Català. Sig. C5.03.05.12.

- Lammel, I. 1974. Hanns Eislers Wirken für die Einheitsfront in der internationalen revolutionären Musikbewegung. In: Manfred Grabs ed. Hanns Eisler heute. Berlin: Akademie der Künste der DDR, pp. 61–5.

- Lammel, I. 1980. Das Arbeiterlied. Leipzig: Phillip Reclam.

- Lapeyre, K. 2010. Los niños de la guerra. La vida en la zona republicana (1936–1939), Cahiers de civilisation espagnole contemporaine. De 1808 au temps présent [online]. Available from: http://journals.openedition.org/ccec/3271 [Accessed 16 March 2021].

- Leenders, B. & Meyer-Rähnitz, B. 2005. Der Phonographische Ernst Busch. Eine Discographie seiner Sprach- und Gesangsaufnahmen. Dresden: Ústí nad Labern.

- Massot i Muntaner, J., Salvador, P. & Martorell, O. 1993. Els Segadors. Himne nacional de Catalunya. Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat Generalitat de Catalunya.

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1933a. Diplomatic Passport Nr. F694, issued in Figueres on 4 February 1933 (Family archive).

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1933b. Letter from Otto Mayer to Ernst Hermann Meyer, 27 July. Ernst-Hermann-Meyer-Archive at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, no catalogue number.

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1933c. Letter from Otto Mayer to Ernst Hermann Meyer, 22 August. Ernst-Hermann-Meyer-Archive at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, no catalogue number.

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1937b. Letter from Mayer-Serra to Josep Valls, 29 November. Biblioteca de Catalunya, Fons Josep Valls, folder JvA 1250.

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1937c. Letter from Mayer-Serra to Josep Valls, 18 December. Biblioteca de Catalunya, Fons Josep Valls, folder JvA 1250.

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1937d. Cançoner Revolucionari Internacional. Vol. 1. Barcelona: Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya.

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1937e. Cançoner Revolucionari Internacional. Vol. 2. Barcelona: Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya.

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1938a. Letter from Mayer-Serra to Josep Valls, 5 January. Biblioteca de Catalunya, Fons Josep Valls, folder JvA 1250.

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1938b. Letter from Mayer-Serra to Josep Valls, 29 April. Biblioteca de Catalunya, Fons Josep Valls, folder JvA 1250.

- Mayer-Serra, O. 1938c. Letter from Otto Mayer to Ernst Hermann Meyer, 1 August. Ernst-Hermann-Meyer-Archive at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, no catalogue number.

- Meyer, E.H. 1964. Aus der „Kampfgemeinschaft der Arbeitersänger“. In: Akademie der Künste, ed. Sinn und Form. Beiträge zur Literatur. Sonderheft Hanns Eisler. Berlin: Rütten und Loening, pp. 152–60.

- Meyer, E.H. 1979. Kontraste–Konflikte. Erinnerungen, Gespräche, Kommentäre. Berlin: Neue Musik.

- Miravitlles, J. 1937. La propaganda en la guerra. In: Set mesos de guerra. [Barcelona]: Comissariat de Propaganda.

- Morag, J.G. 2020. On Music and War. Transposition [online], hors-série 2. Available from: http://journals.openedition.org/transposition/4469 [Accessed 16 March 2021].

- Nelson, A. 2020. Music for the Revolution. Musicians and Power in Early Soviet Russia . Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Palacio, C. 1939. Colección de canciones de lucha. Valencia: Tipografía moderna.

- Palacio, C. 1984. Acordes en el alma. Memorias. Alicante: Instituto Juan Gil -Albert.

- Pascuet, R. & Pujol, E, eds. 2006. La revolució del bon gust. Jaume Miravitlles i el Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya (1936–1939). Figueras: Viena Edicions.

- Prieto, E. 1937. La Secció de Música del Casal de la Cultura. Mirador, 415, 8 April, p. 8.

- Probst-Effah, G. 2009. Streifzüge durch die „Biographie“ eines KZ-Liedes. In: W. Leimgruber, A. Messerli & K. Oehme, eds. Ewigi Liäbi. Singen bleibt populär. Tagung Populäre Lieder. Kulturwissenschaftliche Perspektiven. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 121–36.

- Puigsech Farràs, J. 1999. Nosaltres, els comunistes catalans. El PSUC i la Internacional Comunista durant la Guerra Civil. Vic: Eumo.

- Pujol, E. 2006a. El més petit de tots. In: R. Pascuet & E. Pujol, eds. La revolució del bon gust. Jaume Miravitlles i el Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya (1936–1939). Figueras: Viena Edicions, pp. 66–8.

- Pujol, E. 2006b. París, 1937. In: R. Pascuet & E. Pujol, eds. La revolució del bon gust. Jaume Miravitlles i el Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya (1936–1939). Figueras: Viena Edicions, pp. 68–108.

- Riley, J. 2004. From the factory to the fat: thirty years of the Song of the Counterplan. In: N. Edmunds, ed. Soviet Music and Society Under Lenin and Stalin: The Baton and Sickle. London: Routledge, pp. 67–81.

- Schebera, J. 1998. Hanns Eisler. Eine Biographie in Texten, Bildern und Dokumenten. Schott: Mainz.

- Schneerson, G.M. 1938a. Editorial materials of Canciones de guerra. Испанские революционные песни. Pasaremos! Archivo de la Memoria Histórica — Cat. Incorporados 1918.

- Schneerson, G.M. 1938b. Canciones de guerra. Испанские революционные песни. Pasaremos!. Moscow: ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОЕ ИЗДАТЕЛЬСТВО ‘ИСКУССТВО’.

- Siebig, K. 1980. ‘Ich geh’ mit dem Jahrhundert mit’ Ernst Busch. Eine Dokumentation. Reibeck bei Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschen.

- Stanley, J. 2015. How Propaganda Works. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Teibler-Vondrak, A. 2011. Silvestre Revueltas: Musik für Bühne und Film. Vienna: Böhlau.

- Tellez Cenzano, E. 2016. La música como elemento de representación institucional: el himno de la Segunda República española. Thesis (PhD). Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

- Tomoff, K. 2006. Creative Union: The Professional Organization of Soviet Composers, 1939–1953. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Velasco-Pufleau, L. 2013. The Spanish Civil War in the work of Silvestre Revueltas. In: G. Pérez Zalduondo & G. Gan Quesada, eds. Music and Francoism. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 321–47.

- Venteo, D. 2006. Primera notícia general del Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya (1936–1939). In: E. Pascuet ed. La revolució del bon gust. Jaume Miravitlles i el Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya (1936–1939). Figueras: Viena Edicions, pp. 31–42.

- Voigt, J. 2010. Er rührte an den Schlaf der Welt. Ernst Busch. Die Biographie. Berlin: Aufbau.

- Weiß, M. 1976. Lieder und Gesänge für Solostimme und Klavier. In: M. Hansen ed. Ernst Hermann Meyer. Das kompositorische und theoretische Werk. Leipzig: Deutscher Verlag für Musik, pp. 96–142.