ABSTRACT

Background

: People with dementia are often excluded from research due to ethical concerns and a reliance upon conventional research methods which focus on recall and verbal expression.

Methods

Creative, sensory and embodied research methods typically involve techniques that conceptually bring individuals “into” the research, thus affording an expressive capacity that traditional methods do not. This paper details a “method story”, presenting three interlinked cycles of study used to explore the significance of clothing to people with dementia living in a care home. The studies drew upon arts-based and design led practices. This paper details the methods used and the opportunities that they presented when exploring the lived experience of dementia.

Results and Conclusions:

Creative, sensory and embodied approaches enabled people with dementia to engage with research, supporting imaginative, spontaneous and flexible participation. This supports the use of novel methods when undertaking research with people who have dementia.

Background

This paper focuses on a novel methodological approach used to explore the significance of clothing to people with dementia living in a care home. The findings of the research are presented elsewhere; this paper responds to calls to share “method stories” when working with people with cognitive impairments (Hendriks et al., Citation2015; Lee, Citation2014). Method stories, advocated within codesign projects, emphasise the context and application of the methodologies used i.e. the intricacies involved in using the methods “on the ground”, identifying what designers do and how they feel when making their research methods work (Lee, Citation2012). Method stories can be of value when developing approaches to suit the needs of particular groups, contexts and projects (Hendriks et al., Citation2015; Lee, Citation2014). As research directly involving people with dementia remains limited (Gray et al., Citation2017), this paper positions the value of method stories in enhancing research practice when working with people with dementia through the sharing of insights regarding certain approaches.

This paper responds to calls for researchers to adopt flexible, creative approaches when working with people with dementia (Buse & Twigg, Citation2015; Campbell & Ward, Citation2017; Kontos & Martin, Citation2013) and contributes evidence to the utility of creative methods when carrying out research with people with dementia (Kara, Citation2015; Phillipson & Hammond, Citation2018; Tsekleves & Keady, Citation2021). This paper provides insights into what such approaches offer when working with people with dementia in research, whilst providing guidance to others on the use of creative methods that are malleable, relational and improvisatory.

Defining dementia

Dementia is an umbrella term for a number of diseases that affect the brain. To date, over 200 subtypes of dementia have been identified (Stephan & Brayne, Citation2010), including, but not limited to: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with lewy bodies, and vascular dementia. Broadly, dementia is characterized by a progressive decline in cognition and, although there are individual variations, common symptoms include memory loss, difficulty concentrating, problems carrying out daily tasks and issues with communication (NHS, Citation2020). The decline of cognitive function in people with dementia has led to a prevalent view that the condition leads to a loss of self (identity). This, combined with the medicalisation of dementia – which centres on the losses associated with the condition perceiving it as something to be diagnosed, treated and managed has led to “a paradigm of learned helplessness while waiting for “the cure”“ (Camp, Citation2019: 221). Historically, this has led to the perspectives of people with dementia largely being ignored in research, relying instead upon care-worker and family caregiver reports (Hubbard et al., Citation2003; Taylor et al., Citation2012).

In recent years, guides that promote inclusive approaches and the participation of people with dementia in research have been published. Strategies include ways to support the consent process and to ensure people with dementia have a positive experience when participating in studies (Murphy et al., Citation2015). Despite recommended adaptions, people with dementia are still often excluded from research due to ethical issues, e.g. differing interpretations regarding consent (Fletcher et al., Citation2019), and a reliance upon traditional research methods. Conventional methods such as interviews, focus groups and standardised measures emphasise recall and verbal expression, all of which can make taking part in research problematic for people living with dementia. As the number of people living with dementia increases annually and there is currently no cure for the condition, it is imperative that research includes people with dementia (Bartlett et al., Citation2018) in order to support those with the condition to live as well as possible. Researchers advocate adapting and developing new approaches to support people with dementia to participate in research (Phillipson & Hammond, Citation2018).

Embodied research methods

Ellingson (Citation2017:73) claims that “messy ill bodies” have traditionally been stigmatized and avoided, this is no less true for people with dementia, whose embodied practices, actions and gestures are typically perceived as a symptom of the condition and thus something to be contained and managed. For example, a care-worker wrote an online post to The Dementia Centre at Stirling University (Citation2011), asking the Centre to recommend retailers where “un-rippable” clothing could be purchased for a care home resident who repeatedly tore and pulled at their clothing. The notion of wanting to prevent these actions demonstrates the medicalisation of dementia as the person’s movements were perceived to be symptomatic. People with dementia interact in nuanced verbal and non-verbal ways (Tsekleves & Keady, Citation2021), therefore attending to such actions as potentially meaningful (Morrissey et al., Citation2016) is important.

In recent years, the repositioning of the body, as a source of knowledge and understanding, as opposed to a vessel for the mind, has been pivotal in rethinking conceptualisations and understandings of dementia, i.e. embodied selfhood (see e.g. Kontos, Citation2015; Kontos & Martin, Citation2013; Martin, Kontos & Ward, Citation2013). Embodied selfhood involves recognising the role of the body in the construction and manifestation of the self, meaning that a person is their body and that their wishes and desires are experienced and communicated through their body. This is a significant shift away from the medicalised and deficit-oriented model of dementia, as it involves reconsidering a person’s actions and gestures as expressive and communicative, as opposed to symptomatic.

An embodied approach to carrying out research involves repositioning the body within research, moving away from the traditional mind-body divide to consider that our whole bodies “make sense of the world and produce knowledge” (Ellingson, Citation2017:16). When carrying out research, this involves attending to the ways in which people know through their bodies, as Yanow (Citation2012) writes “the researcher’s body is the main instrument of ethnographic knowing”. For example, Thanem and Knights (Citation2019) posit that interviews are embodied encounters as they are shaped by bodily practices, actions and gestures, facial expressions, and are affected by physical dimensions such as proximity and distance. Hence, bodies interact with and are influenced by other bodies, meaning that “all bodies involved in the research inquiry are active participants whose meaning-making exists in the moment of encounter” (La Jevic & Springgay, Citation2008:7).

The use of embodied research approaches has been advocated when working with people with dementia. For example, researchers (see e.g. Buse & Twigg, Citation2015; Campbell & Ward, Citation2017; Kontos & Martin, Citation2013; Phillipson & Hammond, Citation2018; Tsekleves & Keady, Citation2021) have supported the use of methods, such as photo elicitation and visual and sensory adaptations to interviews. These approaches typically involve the use of “things” within a research encounter. For instance, a sensory adaptation to an interview may involve handling objects to draw out and explore experiences. Such approaches support recognising, attending to and exploring different forms of communication, interaction and expression.

Creative research methods

Embracing the role of the body in research involves the use of established and novel interdisciplinary approaches (Pitts-Taylor, Citation2015). The current project drew upon arts-based and design-led practices broadly referred to as “creative research methods”. Although often considered distinct schools of methods, Woodward (Citation2020) notes that both arts and design involve actively bringing participants “into” research encounters through engagement with material things and processes.

The use of “things” within creative research methods can support and enable researchers to explore and understand “non-verbal, sensory, kinaesthetic, material, and imaginary ways of knowing” (Woodward, Citation2020:68). Hence, researchers claim that creative research methods can elicit knowledge that traditional research methods do not (e.g. Mannay, Citation2015; Pink, Citation2015). For instance, Mannay (Citation2015) discusses the ways in which creative approaches can lead to greater understandings than solely verbal approaches to data collection, for example, they used collage, photography and map making to explore participants experiences of home, and these approaches led to new understandings of “place and space” that lay beyond preconceived ideas. Similarly, Blodgett et al. (Citation2013) note that creative approaches afford people non-verbal capacity and that enables them to express inherently difficult to articulate thoughts and feelings.

Phillipson and Hammond (Citation2018) argue that methods that move beyond recall and verbal expression, which can be difficult for those with dementia, are essential to support people with the conditionto participate fully in research. Creative approaches, which are increasingly adopted within dementia care and commmunity settings (e.g. Ward et al., Citation2020), can similarly be used to support participation in research. Participation in the arts can enable multiple forms of expression and communication, for example taking part in creative activities can enable embodied reactions, e.g. gestures, movements and actions, support non-verbal expression, and facilitate shared interactions for people with dementia (see e.g. Dowlen (Citation2018); Dowlen et al. (Citation2021) Zeilig et al. (Citation2019). Killick and Craig (Citation2012:20) suggest that:

Each artform has its own language, and many of these do not require words for their expressive functioning, and we have found that people with dementia fall upon these languages with a new sense of purpose. They can be valuable for people to communicate with each other and with those without the condition.

In support of arts-based approaches when working with people with dementia, Kara (Citation2015) cites that creative research methods are valuable when working with people who have cognitive impairments. Nevertheless, as Kara (Citation2015) notes, how such approaches are positioned and the aims or questions that guide them are important to consider. Rather than emphasising recall or reminiscence, which can be problematic for people with dementia, this current project focussed on “in the moment” experiences. Keady et al. (Citation2020:7) recently defined this concept:

Being in the moment is a relational, embodied and multi-sensory human experience. It is both situational and autobiographical and can exist in a fleeting moment or for longer periods of time. All moments are considered to have personal significance, meaning and worth.

This work highlights how people with dementia create moments for themselves and how these moments can be relational and interactive. For example, the authors referred to a person with dementia who immersed themselves in a music-making session; this allowed them to forget the difficulties of their everyday life and create music that was personally significant to them. Tsekleves and Keady (Citation2021) advocate “in the moment” approaches when developing research for (and with) people with dementia. The current project attended to and engaged with “in the moment” work through the range of creative, sensory and embodied methods used as these foregrounded alternative interactions and multiple routes to expression.

Research approach and methodology

The creative, sensory and embodied approach of the research was shaped by the research team’s interdisciplinary skillset, and was underpinned by Pink’s (Citation2011, Citation2015) Sensory Ethnography. Sensory Ethnography (SE) draws upon traditional ethnographic techniques: it involves viewing the body as a source of knowledge and is informed by an understanding of the interconnected senses (Howes, Citation2005), meaning that, for instance, visual observations are relevant due to the connection with the other senses. SE therefore incorporates innovative methods that go beyond listening and watching, to employ the use of multiple media (Pink, Citation2015). Within SE, knowledge (or data) is situated and context- specific. Generalisability is not sought, and the active roles of the researcher(s) and participants in co-creating knowledge are embraced.

Researcher reflexivity is an important aspect of SE. Consequently, for the purpose of this project, the lead author engaged with text-based reflections and visual journaling, e.g. drawing, painting, collage-making, to explore experiences and develop their research practice. Extracts from the lead author's reflexive journal are included to illustrate their process and how reflexivity shaped the methods used. The reflexive texts and creative pieces are not considered findings, they were created as a means to think through specific aspects of the research, and as such sit alongside and complement the research carried out with participants.

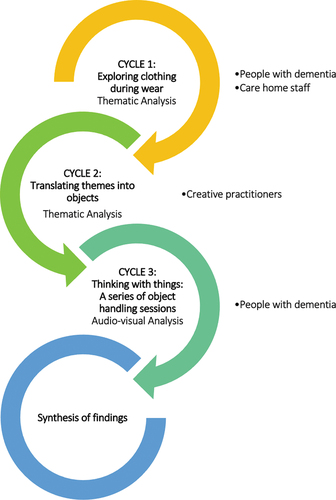

Research was carried out using three intertwined cycles of study (see ) in a multi-method approach: this concurs with Tsekleves and Keady's (Citation2021:147) recommendation that researchers should develop “a repertoire of strategies” when working with people with dementia. The research aims were to explore the embodied and sensory experience of clothing during wear, in order to identify how clothing may be used to enhance the holistic care of people with dementia. The cycles of study were iterative, with each cycle being informed by the findings from the previous cycle of study. CYCLE 1 involved working with people with dementia and care home staff to explore clothing during wear. CYCLE 2 utilised thematic findings from CYCLE 1 to create a series of objects, images and materials, these items were then explored in CYCLE 3 with people with dementia to explore how clothing may contribute to the holistic care of people with dementia.

Our method story involves presenting each cycle of study, detailing the methods used, any intricacies involved, and the opportunities that the respective methods offered. Anonymised participant verbatim, researcher notes and extracts from the researcher’s reflexive journal are used to illustrate the methods used. The findings from the study are presented elsewhere as they are not the focus of this paper.

Prior to carrying out the research, the lead author volunteered at the care home site, building rapport with staff and residents.

Ethical approval for the project was granted by an NHS research ethics committee reference 18/LO/1707. Informed consent or, where appropriate, personal or nominated consultee assent was received for all participants in the research.

CYCLE 1: Exploring clothing during wear using multisensory research encounters

Multiple concurrent observations and interviews, i.e. multisensory “research encounters” took place. The use of the term “research encounters” (Pink, Citation2015) refers to events where knowledge is co-created by the researcher(s) and participant(s), shifting emphasis away from ocular-centric methods of observation and the emphasis on verbal communication in traditional interviews. Research encounters are therefore context-specific, relational and involve multiple forms of expression and communication. The sensorial element to the encounters involved participants (both care home staff and people with dementia) interacting with items in their immediate vicinity, e.g. their clothing and accessories. This approach was informed by the work of Iltanen and Topo (Citation2015), who displayed clothing on a rail and invited participants to explore the embodied, visual and tactile properties of the items. Additionally, the method was shaped by the lead author’s experience of volunteering with the study site:

I volunteered to help with an outing to a local garden/café and whilst sitting with residents, I became aware that one woman had started to unbutton her cardigan. She was quiet in her actions - she didn’t seem uncomfortable or upset as she unbuttoned her garment, once it was all unbuttoned, she then began to rebutton it. I walked over to sit near her and as I approached, I realised that the cardigan was missing a button – her repetitive actions suggested that this felt ‘wrong’ and she seemed to be (repeatedly) trying to correct it. [researcher reflexive note]

This experience, during volunteering, influenced the researcher’s approach to carrying out the project, in terms of practical considerations, for example the time and space needed to understand a person’s actions and how engaging with “things” during the research may generate specific understandings around for instance, how wearing such items feels for individuals. For example, in the case of the cardigan missing a button, the person was not able to express verbally that this felt “wrong,” but their repetitive actions indicated that it did. Interestingly, this corresponds with calls for researchers to participate in training prior to working with people with dementia (Scottish Dementia Working Group Research Sub-Group, Citation2014). Dementia affects people differently and as people with dementia interact and communicate in nuanced ways, researchers must develop their skills in order to support people with dementia to participate in research. Volunteering in this project informally provided training and shaped the researcher’s ability to attend to such moments.

In order to explore clothing during wear and to examine the embodied and sensory engagement with clothing, participants took part in up to six research encounters. This was designed to elicit in-depth understanding about everyday clothing practices, to enable the researcher and participants to become attuned to one another, and support the process of working together. The multisensory research encounters involved naturally tailoring and differentiating each encounter according to each participant (Hendriks et al., Citation2015). The following examples illustrate the varied interactions, engagement and facilitation processes involved in the encounters. The first reveals the shared material interactions involved in handling a participant’s scarf:

When talking with one participant about the scarf that she was wearing, the participant proceeded to take her scarf off, handing it to me; allowing me to handle the item. On handing the scarf back, the participant examined the scarf, handling it – slowly moving the fabric across her hands. She then twisted and distorted the fabric, before folding and refolding it. When putting it back on, she wanted to show me how to tie it in her preferred style, however she became unsure about how to knot the scarf. This was difficult to navigate - I did not want to exacerbate feelings of uncertainty and so I suggested moving on to discuss another aspect of her dress. The scarf remained untied, draped around her neck. She later noticed her untied scarf and without saying a word, innately twisted and knotted her scarf around her neck. I watched as her hands seemingly knew the well-trodden path of tying her scarf. [researcher notes]

The following example details a spontaneous participant-led interaction:

The participant commented on the large resin ring that I was wearing, asking if it was heavy. Without hesitating I took my ring off, handing it to the participant to hold. With the ring in the centre of her palm, she gently moved her hand up and down as though weighing it. She then proceeded to try the ring on, she moved from thumb, to index, to middle, to ring, to little finger, each time splaying her hand seemingly assessing the look and feel of the item. As she moved from finger to finger, she recited a rhyme that she later explained was from her childhood. [researcher notes]

The following reflexive note details how the researcher adapted the environment to support a participant:

There was a dressing table and mirror in the room and on seeing herself in the mirror she exclaimed. She was immediately uncomfortable, and I offered to cover the mirror with a towel, which she agreed to. We spoke for a while and began the research encounter once she was happy to. When talking about her outfit she was comfortable in her clothing and pleased with her outfit, despite being distressed at her appearance in the mirror. [researcher reflexive note]

As the examples illustrate, the pace, flow and direction of the encounters were co-created by researcher and participants. Each encounter was unique and often involved pauses, quiet, unexpected and, at times, difficult moments - thus the researcher’s ability to be open, responsive and sensitive was important. The role of the researcher in this cycle of study drew parallels with that of an arts practitioner (Leavy, Citation2015), knowing when to “step-in” and offer support, distraction or to scaffold ideas, or when to “step-back” and allow for pauses or moments of quiet. These processes were inherently creative, through the ways in which the encounters were relational and shaped “in the moment”. The emplaced, context-specific nature of these processes were honed “on the ground”, through the researcher and participants building rapport over the multiple encounters.

The multisensory encounters facilitated knowledge that would otherwise be unknowable (Ellingson, Citation2017; Pink, Citation2015). The attention to embodiment afforded by the research encounters facilitated access to implicit memories, for example, the person’s retained ability to tie their scarf in their preferred style demonstrated their embodied knowledge and the ways in which aesthetic preferences are performed through the body. Focussing on embodiment captured this expression through their actions rather than verbally. The participatory moments that occurred during the encounters and the embodied expressions that engaging with items prompted, e.g. tying a scarf or weighing a ring demonstrates the ways in which the encounters involved what Tarr et al. (Citation2018) discuss as “live” or unrepeatable data i.e. data which is context-specific and co-created. Subjectivity was embraced within this project, and as generalisability was not sought, moments of “live” data or access to previously “unknowable” knowledge afforded opportunities to build understanding. , taken from the researcher’s reflexive journal, was created to explore the shared material interactions that occurred during the encounters.

CYCLE 2: Translating themes into objects, images and materials

Findings from CYCLE 1 were analysed following a reflexive thematic analysis process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019; Braun et al., Citation2018); the thematic findings generated were used in the second cycle of study. The purpose of CYCLE 2 was to work creatively to interpret thematic findings into a series of objects, images and materials. This process was informed by the work of Chamberlain and Craig (Citation2013, Citation2017), who created artefacts in response to focus group and interview data and then used the artefacts with older people to explore healthcare services. Thus, their methodology, “Thinking with Things”, utilised artefacts to generate knowledge.

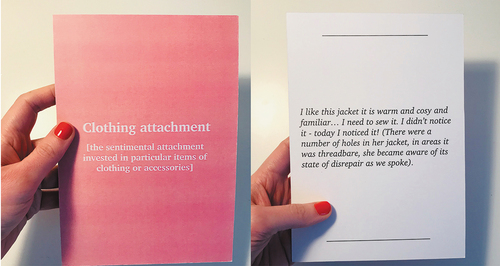

For the purpose of this project, creative practitioners who had expertise of working with people with dementia were recruited. Creative practitioners were invited to engage with findings from CYCLE 1. Presenting thematic findings in a concise and engaging format was paramount, as each practitioner took part in one hour-long research encounter. Each theme was therefore presented as a thematic card, each card included a short synopsis of a finding, supported with at least one participant extract to represent the theme and to foreground the experiences of those with dementia (see . Example of a thematic card). The design of the thematic cards was informed by the idea of cultural probes within design-led research (Woodward, Citation2020). Designing probes involves attending to materiality and aesthetics, e.g. what they look and feel like, carefully considering how participants may engage with and use the probes.

During the research encounters participants engaged with the thematic cards whilst drawing upon their own practice and work with people with dementia, to explore how each finding could be translated into an object, image or material. Sometimes participants drew on their experiences, linking themes to similar instances or moments that they had encountered, whilst in other cases participants were more specific in suggesting, for example, the particular use of a fabric or object in future cycles of study. The thematic cards provided access to the findings from CYCLE 1 and facilitated engagement with the study. However, the encounters were challenging for the researcher to facilitate, as the following extract details:

The thematic cards elicited rich responses, however guiding and facilitating these encounters was difficult in order to explore specific responses to then design CYCLE 3’s sessions. My limited experience of working in this way may have affected the process. I also think that multiple interviews would have been helpful, or perhaps the use of different methods, whereby, after the first interview, I then brought in a series of materials, objects and images and revisited participants to explore their thoughts relating to the items. There are many other opportunities and avenues that could be explored in order to develop this method, yet these were not possible due to time constraints. [researcher reflexive note]

CYCLE 3: Thinking with things: a series of object handling sessions

This cycle of study – a series of object handling sessions – built upon the findings from cycles 1 and 2. The aim of this cycle was to explore the ways in which clothing could be considered in the holistic care of people with dementia. The method involved repurposing the use of object handling sessions, typically a psychosocial intervention for people with dementia (see e.g. Camic et al., Citation2019; Thomson & Chatterjee, Citation2016), as a research method. Although there is not a formal definition for object handling sessions (F. D’Andrea, personal communication, 12 March 2019), they typically involve engaging with and exploring multisensory items through, for instance, handling, selecting, discussing, critiquing and reflecting upon the objects. The creative, exploratory and flexible nature of object handling sessions, combined with the notion that objects can be evocative tools with which to explore participants’ experiences (e.g. Chamberlain & Craig, Citation2013, Citation2017; Woodward, Citation2020), led to the development of object handling sessions as a multisensory research method.

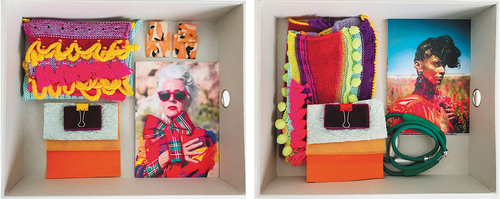

The object handling sessions were themed according to findings from CYCLE 2, resulting in three themed sessions – “dramatic”, “playful” and “narrative”. Each session involved the use of different objects, images and materials that were selected, designed and created in response to the work carried out with creative practitioners in CYCLE 2. Participants with dementia were invited to take part in small groups (i.e. two-three participants) in each of the three sessions. For example, the “playful” sessions consisted of a personalised box of materials for each participant (see ), whilst the “narrative” sessions involved the curation of items on a table to facilitate group discussion.

The sessions were facilitated by the lead author, inspired by previous arts-based work with people with dementia, e.g. Broome et al. (Citation2019). The following examples detail the different interactions and forms of engagement that each session enabled, and the ways in which the researcher’s role differed according to the theme of the session. Participants were often creative in their responses, provoking unanticipated interactions, for example, during one of the “playful” sessions, a participant asked the researcher to try on a necklace – but wear it around her waist:

P20 (PWD): I wanted it around your waist …

I (researcher) stood up, breathing in and standing on tiptoes so that it was easier for P20 (PWD) to try and place the necklace around my waist. This was not something that I had anticipated.

P20 (PWD) wrapped the necklace around my waist, fastening it in place. As she fastened the necklace, she held my loose-fitting top tightly around my back, seemingly wanting to create a more fitted shape.

There … P20 (PWD) said, as she stood back, assessing the look of the necklace on my waist. She went on to say: I think it is nicer there than around your neck – it doesn’t matter where you wear it, it is the effect. [participant verbatim and researcher notes]

During one of the “narrative” sessions, a participant “became” the facilitator and invited the group to respond to her questions:

P21 (PWD) picked up the “Alan Measles” tactile postcard

P21 (PWD): Ok, I am going to interview the pair of you now … She held the card up for P22 (PWD) and me (researcher) to look at.

P21 (PWD): What does this remind you of?

P22 (PWD) smiled: Cuddly teddy bears that we’ve had.

P21 (PWD) passed the card to P22 (PWD) – P22 (PWD) held the card out in front of her and then wrapped her arms around her body, as though cuddling a teddy bear.

P22 (PWD): Reminds me of my fluffy doll, it wasn’t a teddy bear it was a fluffy pillowcase you zipped up … erm … but this isn’t at all a doll, but it reminds me of her …

P22 (PWD) passed the card to me (researcher) and said, How about you?

Researcher: I didn’t have a teddy bear either; I had a cuddly toy elephant. [participant verbatim and researcher notes]

The following reflexive note details the researcher’s response to facilitating one of the “dramatic” sessions:

This session involved the use of multiple fabrics which I supported participants in draping and creating forms around a mannequin (dressmakers stand). It was a very powerful session and captured participants’ imagination. It was also challenging as it was particularly ‘hands on’. Participants were enthusiastic and had many ideas. The member of staff supporting the session got very involved and helped with holding fabrics in place whilst I responded to the design ideas of participants, however if this hadn’t had been the case, I would have struggled to create the designs. Creating participants’ ideas on the mannequin was a wonderful experience but quite a significant shift from the previous sessions (‘playful’ and ‘narrative’), in which my role was a little more passive, e.g., passing items between participants, sharing in handling an item, rather than creating forms on the stand. [researcher reflexive note]

As the examples demonstrate, the researcher and participants worked together in the sessions, thus promoting co-creation. The sessions were aimed at being flexible and creative, requiring the researcher to be adaptable and reactive, responding to participants’ varied forms of engagement. Although different to CYCLE 1’s encounters, the sessions similarly allowed room for participants to construct the sessions according to their interests and preferences. The conceptual position of the researcher and participants were often in flux, for instance, at times the researcher led the sessions in a more traditional facilitator role, whilst at other times (within the same session) she was a “participant” – and at times participants took on facilitator roles.

Videorecording facilitated the researcher’s ability to be “hands on” during the sessions. Videorecording is increasingly used in qualitative research in order to make sense of experience and acknowledge differing modalities e.g. verbal, visual, and touch (Reavey & Prosser, Citation2012). In this project, videorecording facilitated capturing non-verbal embodied moments and enabled “re-visiting” the sessions. This led to uncovering less overt moments within the sessions, for example:

On re-watching the footage, I became aware of multiple moments when one participant quietly and slowly interacted with a textile sample. She handled a knitted textile sample, moving it from her lap to her chin, she rubbed the soft pompoms slowly back and forth across her chin in a comforting manner. [researcher notes]

Interestingly, this moment had gone unnoticed within the “live” session. Thus, videorecording enabled exploration of the varied forms of participation, expression and interaction supported by the sessions – it complemented the method and led to knowledge that would otherwise be “unknowable” (Ellingson, Citation2017). This also highlighted opportunities to differentiate the object handling sessions according to individual preferences and requirements (Hendriks et al., Citation2015), e.g. to work on a one-to-one basis to support various “moments” (Keady et al., Citation2020) and interactions.

Discussion

This method story demonstrates the opportunities that creative, sensory and embodied methods afford when working with people with dementia in a care home setting and identifies how such methods might lead to knowledge that would otherwise be unknowable (Ellingson, Citation2017). For example, interacting with clothing and textiles enabled individuals with dementia to demonstrate their aesthetic preferences through embodied practices: for instance, draping fabric or tying a scarf. The use of “things” specific to the research conceptually brought participants “into” the encounters and supported participation at different levels. Attending to the sensorial and embodied aspects of clothing during wear enabled nuanced understanding, as the approach foregrounded the “in the moment” experiences of people with dementia and facilitated unanticipated, spontaneous interactions and responses. The methods were shaped by the experiences of the participants and researcher, thus connecting with Hendriks et al. (Citation2015), who recommended tailoring practices to meet individual’s needs.

This method story was context-specific; hence, it is not possible to claim that the methods would directly translate to other research projects, yet it is possible that similar approaches could be adopted. For example, the process of working closely with the study site prior to the study was invaluable in building rapport and developing project-specific research methods. Fletcher et al. (Citation2019) claim that such “hanging out” periods are important in supporting inclusive ethical practice in dementia research. Volunteering informally acted as a training process, whilst multiple research encounters enabled the researcher to become attuned to the nuanced ways in which people with dementia may interact and communicate (Tsekleves & Keady, Citation2021). Moreover, interdisciplinary approaches are recommended, for example, researchers working closely with creative practitioners. Additionally, in line with other practice-based studies (e.g. Robertson, Nevay, Jones et al. (Citation2020) and Shercliff & Twigger Holroyd, (Citation2020)), CYCLE 3’s object handling sessions demonstrate that such approaches can be of value across disciplines.

The inclusion of extracts from the lead author’s reflexive journal foregrounds the reflexive aspects of this project and their role in developing the methods used. Such insights are not only useful in enhancing an individual’s practice, but are of use when developing innovative methods.

Conclusion

This paper identifies the potential of method stories in enhancing research practice when working with people with dementia. The process of creating a method story is reflexive and involves considering methodological challenges and opportunities – arguably this process is essential when adapting existing methods or developing new approaches to work with people with dementia and enhance research practice (Phillipson & Hammond, Citation2018; Tsekleves & Keady, Citation2021).

This method story highlights the potential that creative, sensory and embodied methods have when carrying out research with people with dementia in a care home setting. Such methods are powerful conduits with which to explore the lives of people with dementia and develop understandings that may otherwise remain unknown. Future research should consider including such approaches to promote and support embodied, non-verbal, flexible participation, particularly in populations where traditional verbal recall methods may be challenging.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those who participated in and supported this project. The research was supported by University of West London [Vice Chancellor’s Doctoral Scholarship 2017-2020].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bartlett, R., Gjernes, T., Lotherington, A. T., & Obstefelder, A. (2018). Gender, citizenship and dementia care: A scoping review of studies to inform policy and future research. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12340

- Blodgett, A., Coholic, D., Schinke, R., McGannon, K., Peltier, D., & Pheasant, C. (2013). Moving beyond words: Exploring the use of an arts-based method in Aboriginal community sport research. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 5(3), 312–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.796490

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Terry, G., & Hayfield, N. (2018). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in health and social sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Broome, E., Dening, T., & Schneider, J. (2019). Facilitating imagine arts in residential care homes: The artists’ perspectives. Arts & Health, 11(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2017.1413399

- Buse, C., & Twigg, J. (2015). Materialising memories: Exploring the stories of people with dementia through dress. Ageing and Society, 36(6), 1115–1135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15000185

- Camic, P., Hulbert, S., & Kimmel, J. (2019). Museum object handling: A health-promoting community-based activity for dementia care. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(6), 787–798. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316685899

- Camp, C. (2019). Denial of Human Rights: We Must Change the Paradigm of Dementia Care, Clinical Gerontologist, 42(3), 221–223, https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2019.1591056

- Campbell, S., & Ward, R. (2017). Videography in care-based hairdressing in dementia care: Practices and processes. In J. Keady, L. C. Hydén, A. Johnson, & C. Swarbrick (Eds.), Social research methods in dementia studies: inclusion and innovation (pp. 96–119). Routledge.

- Chamberlain, P., & Craig, C. (2013). Engagingdesign – Methods for collective creativity. In M. Kuruso (Ed.), Human-computer interaction, part I, HCII 2013, LNCS 8004 (pp. 22–31). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- Chamberlain, P., & Craig, C. (2017). HOSPITAbLe: Critical design and the domestication of healthcare. Research Through Design 2017 Proceedings. Edinburgh : Figshare. https://figshare.com/articles/HOSPITAbLe_critical_design_and_the_domestication_of_healthcare/4746952

- Dowlen, R. (2018). The ‘in the moment’ musical experiences of people with dementia: A multiple-case study approach (Doctoral thesis, University of Manchester). https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/en/theses/the-in-the-moment-musical-experiences-of-people-with-dementia-a-multiplecase-study-approach(48599400-3e3d-4871-a0e3-94d6b3692a5d).html

- Dowlen, R., Keady, J., Milligan, C., Swarbrick, C., Ponsillo, N., Geddes, L., & Riley, B. (2021). In the moment with music: An exploration of the embodied and sensory experiences of people living with dementia during improvised music-making. Ageing and Society, 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0144686X21000210

- Ellingson, L. (2017). Embodiment in Qualitative Research. Routledge.

- Fletcher, J., . R., Lee, K., & Snowden, S. (2019). Uncertainties when applying the mental capacity act in dementia research: A call for researcher experiences. Ethics and Social Welfare, 13(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2019.1580302

- Gray, K., Evans, S. C., Griffiths, A., & Schneider, J. (2017). Critical reflections on methodological challenge in arts and dementia evaluation and research. Dementia, 17(6), 775–784. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217734478

- Hendriks, N., Slegers, K., & Duysburgh, P. (2015). Codesign with people living with cognitive or sensory impairments: A case for method stories and uniqueness. CoDesign, 11(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1020316

- Howes, D. (2005). Empire of the Senses: The sensual cultural reader. Berg.

- Hubbard, G., Downs, M., & Tester, S. (2003). Including older people with dementia in research: Challenges and strategies. Ageing & Mental Health, 7(5), 351–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786031000150685

- Iltanen, S., & Topo, P. (2015). Object elicitation in interviews about clothing, design, ageing and dementia. Journal of Design Research, 13(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1504/JDR.2015.069759

- Kara, H. (2015). Creative research methods in the social sciences: A practical guide. Policy Press.

- Keady, J., Campbell, S., Clark, A., Dowlen, R., Elvish, R., Jones, L., Kindell, J., Swarbrick, C., & Williams, S. (2020). Re-thinking and re-positioning ‘being in the moment’ within a continuum of moments: Introducing a new conceptual framework for dementia studies. Ageing and Society, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001014

- Killick, J., & Craig, C. (2012). Creativity and communication in persons with dementia. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Kontos, P. (2015). Dementia and Embodiment. In J. Twigg. & W. Martin. (Eds.), Routledge handbook of cultural gerontology (pp. 173–181). Routledge.

- Kontos, P., & Martin, W. (2013). Embodiment and dementia: Exploring critical narratives of selfhood, surveillance, and dementia care. Dementia, 12(3), 288–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213479787

- La Jevic, L., & Springgay, S. (2008). A/ r/ tography as an ethics of embodiment: Visual journal in preservice education. Qualitative Inquiry, 14(1), 67–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800407304509

- Leavy, P. (2015). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice. The Guildford Press.

- Lee, J. (2012). Against method: The Portability of method in human-centered design. Aalto University. https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/11461

- Lee, J. (2014). The true benefits of designing design methods. Artifact, 3(2), 5. https://doi.org/10.14434/artifact.v3i2.3951

- Mannay, D. (2015). Visual, narrative and creative research methods: Application, reflection and ethics (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315775760

- Martin, W., Kontos, P., & Ward, R. (2013). Embodiment and dementia. Dementia, 12(3), 283–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213485234

- Morrissey, K., Wood, G., Green, D., Pantidi, N., & McCarthy, J. (2016). “I’m a rambler, I’m a gambler, I’m a long way from home.” The place of props, music and design in dementia care. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, (pp. 1008–1010). New York: Association for Computing Machinery

- Murphy, K., Jordan, F., Hunter, A., Cooney, A., & Casey, D. (2015). Articulating the strategies for maximising the inclusion of people with dementia in qualitative research studies. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 14(6), 800–824. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213512489

- NHS. (2020). Dementia guide: Symptoms of dementia. Retrieved August 3, 2020, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dementia/about/

- Phillipson, L., & Hammond, A. (2018). More than talking: A scoping review of innovative approaches to qualitative research involving people with dementia. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918782784

- Pink, S. (2011). Multimodality, multisensoriality and ethnographic knowing: Social semiotics and the phenomenology of perception. Qualitative Research, 11(1), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111399835

- Pink, S. (2015). Doing Sensory Ethnography (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Pitts-Taylor, V. (2015). A feminist carnal sociology? Embodiment in sociology, feminism and naturalized philosophy. Qualitative Sociology, 38(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-014-9298-4

- Reavey, P., & Prosser, J. (2012). Visual research in psychology. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 185–207). American Psychological Association.

- Robertson, L., Nevay, S., Jones, H., Moncurl, W., & Lim, C. (2020). Birds of a feather sew together: A mixed methods approach to measuring the impact of textile and e-textile crafting upon wellbeing using Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale. In K. Christer, C. Craig, P. Chamberlain (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Design4Health (pp. 561–570). Amsterdam: Lab4Living Sheffield Hallam University

- Scottish Dementia Working Group Research Sub-Group. (2014). Core principles for involving people with dementia in research: Innovative practice. Dementia, 13(5), 680–685. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214533255

- Shercliff, E., & Holroyd Twigger, A. (2020). Stitching Together: Participatory textile making as an emerging methodological approach to research, Journal of Arts & Communities, 10(1–2), 5–18

- Stephan, B., & Brayne, C. (2010). Prevalence and projections of dementia. In M. Downs & B. Bowers (Eds.), Excellence in dementia care: Research into practice (pp. 9–35). Open University Press.

- Tarr, J., Gonzalez-Polledo, E., & Cornish, F. (2018). On liveness: Using arts workshops as a research method. Qualitative Research, 18(1), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117694219

- Taylor, J. S., DeMers, S. M., Vig, E. K., & Borson, S. (2012). The disappearing subject: Exclusion of people with cognitive impairment and dementia from geriatrics research. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 60(3), 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03847.x

- Thanem, T., & Knights, D. (2019). Embodied research methods. Sage.

- The Dementia Centre. (2011, September 1). Tearing Clothing. https://dementia.stir.ac.uk/tearing-clothes.

- Thomson, L. J. M., & Chatterjee, H. J. (2016). Well-being with objects: Evaluating a museum object-handling intervention for older adults in health care settings. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35(3), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464814558267

- Tsekleves, E., & Keady, J. (2021). Design for people living with dementia. Routledge.

- Ward, C. M., Milligan, C., Rose, E., Elliott, M., & Wainwright, R. B. (2020). The benefits of community-based participatory arts activities for people living with dementia: A thematic scoping review. Arts & Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2020.1781217

- Woodward, S. (2020). Material methods: Researching and thinking with things. Sage.

- Yanow, D. (2012). Organizational ethnography between toolbox and world-making. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 1(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/202466741211220633

- Zeilig, H., Tischler, V., van der Byl Williams, M., West, J., & Strohmaier, S. (2019). Co-creativity and agency: A case study analysis of a co-creative arts group for people with dementia. Journal of Aging Studies, 49, 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2019.03.002