ABSTRACT

The article discusses design against segregation in an urban context characterized by diversity. It sets out to understand how individual experiences of urban space can lead to segregation of places between diverse inhabitants. We argue that the introduction of experience-based spatial design that takes note of perceptions and social interactions and their entanglement with the material aspects of space, is needed to tackle the processes where urban amenities and places become segregated. In our search for social and material fabrics that promote meaningful encounters in an urban environment, we combine an experience-based dataset collected among older people and young migrant adults with design-based observations. In our analysis, we utilize the concept of conviviality as a tool to translate experience-based knowledge into tangible information inputs for spatial design. The analysis culminates in the creation of visions that exemplify how experience-based knowledge can be operationalised for designing against segregation.

1. Introduction

City-making is about making spaces of collectivity and segregation, of inequality and illegality, of mobility and materiality. These designs are scored into the city in built and unbuilt patterns. (Tonkiss Citation2013, 70–71)

This article sets out to examine the dynamics of collectivity and segregation and their built and unbuilt patterns in an urban context characterised by increasing diversity. It draws on urban sociologist Fran Tonkiss’s (Citation2013, 37) work, where the city is not only viewed in terms of spatial boundaries and entitlements, infrastructures, and urban environments but conceptualised as “densities and distributions of people” as well as “spatial relations between social groups.”

The manifestations and effects of diversity within societies have spurred wide-ranging scholarly interest in the entanglements of design and public social life in urban contexts (e.g. Gehl Citation2010; Warf and Arias Citation2009; Talen Citation2006; Sandercock Citation2003). While the organisation of both objects and people in space forms the core of design in urban settings (Madanipour Citation2014), increasing diversity challenges the capacity of urban design to consider the heterogeneity of experiences among variously positioned inhabitants. This calls for centralising social and material urban fabrics when identifying the experienced limitations and possibilities in the urban space (Madanipour Citation2014, 29). In this article, we explore how empirical data, consisting of lived experiences in combination with design-based observations from local settings, can be translated into information that is relevant and applicable in design to prevent the segregation of public and community places in the context of increasing diversity.

The adopted take is based on a particular understanding of segregation. Urban segregation, denoting unequal distribution of various social groups in the urban space, is a collective manifestation of individual behaviour and choice (Musterd Citation2020a, 2). Recently, conceptualisations of urban segregation beyond socioeconomic or groupist and area-based understandings have gained increasing interest (Musterd Citation2020b). Research has called attention to public space as possible solutions to combat segregation, but also as an arena where segregation takes place (Low, Taplin, and Scheld Citation2005; Madanipour Citation2020; Cucca Citation2020). Segregation of places ensues and impacts both social and material aspects in space. Setha Low, Taplin, and Scheld (Citation2005, 15) argue that sometimes the exclusion of certain groups from public space results from deliberate action, but it can also be a by-product of “privatization, commercialization, historic preservation, and specific strategies of design and planning.” We claim that an understanding of how and why urban space becomes segregated and how segregation can be countered requires knowledge about individual experiences of space (Van Aalst and Brands Citation2020; Musterd Citation2020a, 4–5; Bailey Citation2020, 367; Kwan Citation2013, 1079).

While experience-based knowledge has been deemed elemental for design (Gehl Citation2010), there remains a gap in collecting, translating, and utilising the temporally and situationally changing experiential aspects of space in design practices (Maununaho Citation2016; Talen Citation2006, 240–41). This gap regards tensions between diverse and often conflicting experiences that a single place can raise, and between combining first-hand experiences with professional knowledge. While the tension between experience-based knowledge and professional knowledge has been studied in the context of urban planning (Faehnle et al. Citation2014; Sandercock Citation2003), this is less so in the field of spatial design. This article contributes to the discussions of the value, role, and use of experience-based knowledge in urban design by focusing on the social and material aspects of urban places to prevent segregation in the context of increasing diversity.

The promotion and protection of an urban mix necessitates design against segregation, suggests Tonkiss (Citation2013, 214), whereby diverse users’ access to open space and other urban amenities across city neighbourhoods is secured. Following Tonkiss’s idea, we perceive non-exclusionary public and community places as core elements of design against segregation. Strategies that support the ways in which cities “do diversity” involve both legal and policy designs and physical design in the form of mixed-used developments and shared public places (Tonkiss Citation2013, 214). Our focus will be on design issues related to the lived experience of urban space. While design for diversity policies focus on regional or neighbourhood-level social mixing, or targets for mixed uses, structural diversity, and the density of urban amenities in urban planning (Talen Citation2006; Jacobs Citation1961; Gehl Citation2010), design against segregation considers the experiential processes that affect segregation on the microscale of everyday urban spatiality – in urban places.

We claim that diversity gives rise to new forms of sociability, which require holistic ways of understanding public social life, producing knowledge about it, and incorporating that knowledge into design practices. Besides changes in planning, designing non-exclusionary urban places requires focusing on the smaller scale: the spatial, functional, temporal, and social factors in the urban environment. For us, design against segregation necessitates studying the everyday in cities by combining experiences of social interactions with their situatedness within local material surroundings (Tonkiss Citation2013, 49; also Wise and Noble Citation2016, 426). A focus on individuals’ exposure to others during their daily time–space experiences can facilitate an exploration of how individual experiences affect socio-spatial inequalities (Musterd Citation2020a, 11; Kwan Citation2013). To study the segregation of places, we are interested in how some places communicate a welcoming and inclusive atmosphere, bring people together, and secure equitable access to public and semi-public space to uphold diversity (see also Talen Citation2006), while in other places encounters are prevented.

In the task of translating lived experiences to experience-based knowledge, we analyse how social, functional, temporal, and spatial factors intertwine experientially and either promote or hinder meaningful contacts. In this task, we operationalise the notion of conviviality (convivencia) that, instead of starting from fixed ideas of culture, identity, and difference, enables a focus on sociability that occurs between people and their spatial settings in public places (Back and Sinha Citation2016; Radice Citation2016). Conviviality allows an examination of how public social life is created in relation to spatial surroundings and other inhabitants (cf. Andrews, Johnson, and Warner Citation2020). The concept acknowledges the ambivalence of living together as it centralises friction and negotiation in community life (Wise and Noble Citation2016, 424–25), and hence is a well-suited analytical tool to explore the potential for (undifferentiated) encounters in urban space.

We use conviviality as a translational concept that enables the formulation of experience-based knowledge out of the fluid, contextual, and often conflictual experiences from everyday environments, and further implement it in tackling the segregation of urban places. First, we create our conceptual-methodological framework for exploring the opportunities of experience-based spatial design through recent studies on segregation, discussions around conviviality, and their implications for urban design. Second, we introduce our research context, data, and methods. Third, the experience-based and design-based datasets are analysed to identify both obstacles and potentials for conviviality in various urban places. Finally, we conclude the translation task and bring the three analytical categories together in the form of design-oriented visions and pathways. In this section, we create implementable experience-based design knowledge to understand social relations and spatial experiences among diverse inhabitants and to design against segregation.

2. Conviviality: tackling segregation through spatial design

The idea of segregation of places relates to prominent debates in urban research and design about the ways of controlling or enabling human contacts through physical forms (Whyte Citation1980; Lynch Citation1995/1984; Sennett Citation1990; Talen Citation2006; Madanipour Citation2020). Urban policies aiming to combat segregation by increasing contacts in urban space – by radical or reformist design strategies – have been criticised for their naïve visions of social unity and incapacity to conform to increasing diversity (Madanipour Citation2020, 179; Fincher and Iveson Citation2008, 87–8). Knowledge gaps concerning the qualities of the everyday environment and its capacity to facilitate meaningful contacts have been pointed out (Talen Citation2006; Cucca Citation2020). As a part of the processes of segregation of places, differentiation in and neglect of the qualities of urban environments can result in a downward spiral where social relations between diverse inhabitants in urban space are prevented (Skifter Andersen Citation2002), thus resulting in closed enclaves and increased self-segregation (Cucca Citation2020; Madanipour Citation2020).

In cities everyday life is founded on difference, which makes it crucial to understand how meaningful, substantive inhabitance is enacted and in which kind of places it becomes possible for diverse people (Tonkiss Citation2013, 437–40). Tonkiss’s call for non-exclusionary spaces (Citation2013) coincides with Madanipour’s (Citation2020, 182) notion of accessible spaces that offer possibilities of “non-commodified social encounters, inclusive expressive presence and active participation,” which work against segregation by “helping the different parts of society being in continuous interaction with each other.” While local communities and mundane encounters are often regarded to overcome differences, enabling people to live with difference or through difference (Fincher and Iveson Citation2008, 87; Amin Citation2002), encounters also entail social hierarchies and normative understandings of acceptable behaviour and presence in a given space (Valentine Citation2008). Hence, encounters can also provoke disagreement and conflict (Tonkiss Citation2003; Wise and Noble Citation2016), which emphasises the need to understand the quality and context of spatial experiences.

In urban space, contacts often remain passive and fleeting (Mehta Citation2014, 98; Gehl Citation2010) yet they shape people’s conceptions of others and the surrounding society. The forms of contact most directly influenced by the physical environment are what Jan Gehl (Citation2010, 22–23) calls see and hear activities: watching, listening, and observing others. Also, as Juhani Pallasmaa (Citation2005, 17–19) highlights, multisensory perspectives are required if designers wish to avoid pushing people “into detachment, isolation and exteriority.” Moreover, experiences of material environment intertwine with social relations in a way that makes it impossible to distinguish clearly between the two. Lived experiences include accounts of a city that is not anymore or that is not yet. Thus, experience-based knowledge calls attention to anticipations, presences, and absences that are also communicated through design (see also Nijs and Daems Citation2012, 188–89; Pallasmaa Citation2005, 67–68). Social densities and intensities of the city are hard to map and influence through design if there is not sufficient understanding of the experiential and normative elements that shape behaviour and choices (see also Tonkiss Citation2013, 129–30; Gehl Citation2010, 28, 63). For us, an interdisciplinary exploration into design against segregation of places finds an appropriate translational apparatus in the concept of conviviality.

Fincher and Iveson (Citation2008, 145–46) suggest a change of focus in urban planning from the creation of community spirit to the recognition of differential needs and values. For them, fostering conviviality sustains encounters between people in urban space (see also Peattie Citation1998, 247). Martha Radice (Citation2016), studying multicultural commercial streets, claims that the prerequisites for the socio-spatial configuration of conviviality are heterogeneity, accessibility, and flexibility. According to Radice, codes of sociability that regulate places, relations between groups, and individuals’ experiences of places constitute important topics to be explored (see also Van Aalst and Brands Citation2020; Andrews, Johnson, and Warner Citation2020). The potentials and obstacles of conviviality can be mapped through a focus on “third places” (Peattie Citation1998, 249) – such as cafés, stores, and community centres – that are neither completely private nor totally public (Laurier and Philo Citation2006; Oldenburg Citation1989). Such places, where everyone is being “welcomed” and that are “open” to anyone, form “microspaces of conviviality” (Wessendorff Citation2016, 457–59) where people interact and engage in mundane conversations and activities (see also Amin Citation2002, 969; Sandercock Citation2003, 94). Through shared activities, convivial encounters enable people to craft new identifications for themselves and for the world around them (Fincher and Iveson Citation2008, 154–56; Peattie Citation1998, 247). Conviviality involves negotiations, frictions, and tensions (Wise and Noble Citation2016, 425), which allows differences to coexist in urban crowds. Building on these discussions, we use conviviality as a translational concept to understand both potentials and obstacles to meaningful encounters in the city and make experience-based spatial design knowledge to prevent segregation of places.

3. Data and methods

Our empirical focus is on older people’s and young migrant adults’ lived experiences as well as design-based observations in urban places in Tampere, the third-largest city in Finland, with approximately 241,000 residents. Tampere offers an apt context to study design against segregation of places. The city has a long tradition of implementing anti-segregation policies, especially social mixing policies. Residential segregation in terms of income and ethnicity is relatively low when compared internationally, although since the early 2000s there has been slight increase in residential segregation by income (Saikkonen et al. Citation2018). Yet a recent report by the Tampere City Region (2020) suggests that the trend for socioeconomic segregation has been continuous.

The selected groups for this study, older people, and migrants, represent two prominent dimensions (ethnic and demographic) in the study of segregation (Musterd Citation2020a, 7). Although they are not the only relevant groups to study in this context, they shed light on the variety of individual choices and social processes that are connected to spatial segregation. The increase in the number of both migrants and older people has constituted the key demographic trend in Tampere throughout the 2000s. According to the official statistics of Tampere, older people (65 years of age or older) constituted 19% of the population in 2018. The share of people speaking other than Finnish or Swedish as their native language was 8%, and young people 20–29 years of age constituted a significant share (21.8%) of them.

The experiences of older people and young migrant adults were collected in 2017 and 2018 through interviews that have followed the principle of informed consent. With older people, seven group interviews ranging from 1,5 to 2 hours were organised in two community centres in the suburb of Hervanta, an outer suburb of Tampere. Hervanta was chosen because of the Age-Friendly Hervanta project (2015–2017), which was implemented to test the national policies of the World Health organization (WHO)’s Age-Friendly Cities approach that seeks to promote age-friendliness in terms of social participation, outdoor spaces, housing, transportation, services, civic participation and employment, and communication (WHO Citation2007). Three group interviews entailed general discussions regarding participants’ daily lives in Hervanta, while four had specific themes: services, nature, leisure, and housing. The aim was to evoke discussion between participants and to provide them freedom to share meaningful aspects of their lives, while the facilitator was more in the background. Group interviews were advertised in local forums: two community centres, a library, pharmacy, health centre, and a newspaper. We reached 28 participants (19 female, 9 male) who were a heterogeneous group of Finnish pensioners living in the suburb. The interviews shed light on the manifold ways in which urban places enable or restrict the daily activities and encounters of older people.

In addition, we collected data on young adult migrants’ social life in the city. The participants were so-called first-generation migrants aged 19–29 years. Most of them had come to Finland as asylum seekers or quota refugees and, as such, they face particular challenges in participating in the society (see also Leino and Puumala Citation2021). Within this group, six thematic interviews (N = 12, 6 female, 6 male) were conducted. The participants could choose whether to participate in a group interview or be interviewed individually. The interviews lasted between 37 minutes and two hours with the group interviews being longer and involving also exchange between the participants regarding their divergent or similar experiences. The aim was to explore the quality and meanings of mundane encounters in the city and their role in shaping the participants’ perceptions of their surroundings. They were asked to identify places that they found appealing or inviting, as well as share experiences of both pleasant and unpleasant encounters in urban public space.

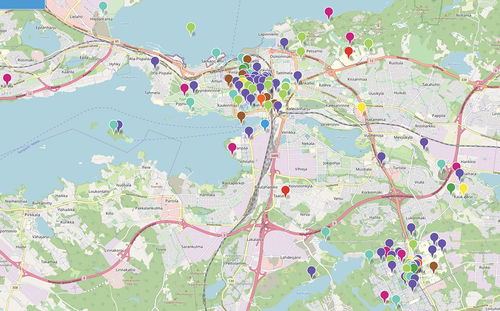

The interviews were transcribed, and the experiences were categorised based on the type of activity and located on a mapFootnote1 (see ). The resulting map, “Experienced Tampere,” illustrates the diversity of experiences in the city and highlights how practices of inclusion and exclusion unfold relationally and how they affect the spatial experiences. Madanipour (Citation2020, 171) underscores the differences of official city maps focusing on functional structures, land uses, roads, and landmarks, and city dwellers’ mental maps, which add new layers of meaning and portray differences in experiences. The experience-based map enabled us to identify the microspaces of conviviality that entailed a high density of participants’ experiences of social interaction. These selected urban areas represent densifications of structure and services both in official city maps and the “Experienced Tampere” map; the Hervanta suburban centre (seven places) includes experiences from both datasets, whereas the Tampere city centre (nine places) consists mainly of young adults’ experiences. Despite most of the migrant youth living outside the centre, their experiences mostly focused on the city centre, while older people’s experiences emphasized the importance of their residential area. Spatially, the two areas provide a comparison between the old, mixed city structure and the newer suburban environment. For comparability, we divided the identified places into two categorisations: commercial gathering places and public activity facilities.

In these sites, design-based observations of the places and ongoing activities were conducted in 2019 and 2020 by the first author, who is an architect. The observations utilised Pallasmaa’s (Citation2005) multisensory perspective, focusing on lighting, acoustics, scents, touch, bodily images of action, and the interaction of perceptions, memory, and imagination. The observation dataset includes photographs and fieldnotes taken during pilot visits, round-the-clock observation periods, and shorter complementary visits. The observations were based on prior knowledge from the interviews, the researcher’s subjective bodily experiences in the places, professional experience in architectural design, and a designerly intention towards spatial improvements. Methodologically, the observations worked as the first translating act between experiential and professional knowledge. Whereas the interview data permit us to focus on the experience that is formed through encounters, design-based observations provide more detailed information on the material and sensory characteristics of the environment, routes, and activities, as well as the design potentials in the places.

To analyse the data, we adopted an interpretative approach that operationalises the concept of conviviality and creates a shared framework that enabled us to combine, contrast, and analyse the datasets. To identify the potentials for and obstacles to conviviality, we determined three analytical lenses with social factors cutting across the data: socio-spatial, socio-functional, and socio-temporal (). This is in line with the presented understanding of social relations being crucial for an experience of space and acknowledges that people’s ways of being in, claiming, and using space vary. We utilised the lenses to thematically categorise both interview data (lived experiences) and design-based observations concerning the identified places ().

We identified experiences and observations that relate to the spatial, functional, and temporal aspects of sociability in the given place in both datasets. Social factors consist of pleasant or unpleasant encounters: meeting friends, having conversations with people, or just being by oneself among urban strangers, but also hostile confrontations with others. Social factors reveal how spatially, functionally, and temporally similar settings can appear different depending on a person’s experienced social situation and positionality (Hiss Citation1990; Malpas Citation2018). Spatial factors regard two aspects. First, they are about spatial configurations such as locations, connections, physical objects, and boundaries in space. Second, they regard the sensory characteristics, such as lighting, materiality, sounds, smells, and elements of nature. Significantly, multisensory experiences create vivid connections in people’s memories between different times and places (Pallasmaa Citation2005). Functional factors emphasise both necessary everyday activities, such as running errands or taking care of one’s basic needs, and optional recreational activities (Baeza, Cerrone, and Männigo Citation2017). For optional activities that enable sociability, both facilitating and impeding factors in the urban environment are particularly relevant (Gehl Citation2010). Finally, temporal factors are related to perceived changes in seasons and times of day, to personal history, the present, and the anticipated future (Nijs and Daems Citation2012). Memories can create meanings that are attached to current situations and environments. While the spatial and functional factors remain the same, a person’s experience of space can change due to temporal cycles or changes in life situation.

4. Obstacles to and potentials for convivial encounters in the city

Our scrutiny into the potentiality of experience-based spatial design in microspaces of conviviality begins by overlaying older people’s and young migrant adults’ lived experiences with design-based observations in urban semi-public commercial gathering places, such as cafés and shopping centres. After this, we explore public activity facilities, which are regarded to be open for all, without consumption or membership. Hence, the vast category, based on the notion of equal rights to the place, gathers a rich array of places such as public parks, public libraries, community centres, and activity facilities. We are aware that both categories, commercial gathering places and public activity facilities, include and represent vastly diverse environments. The two categories have been formed on the grounds of experience-based data, which makes it meaningful to explore what kind of potentials and obstacles for conviviality can be identified therein.

4.1. Commercial gathering places: Cafés and shopping centres

Cafés are a classic example of places for gatherings among friends in the presence of strangers (Laurier and Philo Citation2006; Oldenburg Citation1989). They provide essential social functions and attractiveness to urban streets (Gehl Citation1987; Mehta Citation2014). Currently, also shopping centres are shifting focus from mere consumer product sales towards social functions, tempting customers for daily errands and recreational consumption and offering protected indoor gathering spaces. Nevertheless, our analysis of the conviviality potentials and obstacles revealed exclusionary practices and characteristics in both shopping centres and cafés.Footnote2

From a socio-spatial perspective (), design-based observations show that shopping centres are designed to pull people in; the entrances are made visible, open, and accessible, and the interiors create continuations of public space outside. The trend of turning shopping centres into open living rooms is visible in the seating furniture and USB charging possibilities in the common areas outside the shops (see ). Experience-based data, in turn, indicates that older people perceive the local mall as a meaningful social place, enabling encounters with acquaintances and strangers (see also Van Melik and Pijpers Citation2017).

Figure 4. Observation photographs from commercial gathering places. Seating arrangements offer socio-functional possibilities for resting, meeting acquaintances, watching other people, playing, and working. Socio-spatial factors such as type and arrangement of seating, as well ass socio-temporal factors such as daily rhythms affect these potentials.Footnote3

In contrast to these potentials, young migrant adults describe experiences of confrontations with and unfriendly behaviour from other customers or the personnel in the same shopping centre. The experience of the place is radically different calling others to come again while pushing others away. While socio-spatial obstacles faced by migrants in malls and cafés are mainly caused by discriminatory attitudes, older people note physical mobility barriers, such as long walking distances. There are also social struggles over who gets to use, for instance, the benches, which in our data had eventually shaped the spatial setting by some benches being removed to deter people whose presence was regarded as negative. Thus, spatial amenities such as benches can facilitate meaningful encounters, but also initiate struggles over public space (Loukaitou-Sideris, Brozen, and Levy-Storms Citation2014; Ottoni et al. Citation2016). Despite having several negative experiences with cafés and shopping centres, the migrant adults emphasise certain cafés and flea markets as welcoming places with a cosy atmosphere.

When looking through the socio-functional lens (see ), lived experiences from cafés portrays them as places where one encounters friends and occasionally also engages with strangers (see Laurier and Philo Citation2006). According to design-based observations, some cafés also permit work and leisure activities. Besides functionalities, differences in materials, lighting, views, and soundscapes create diverse atmospheres. As both the lived experiences and observations point out, the social conduct of others, particularly if under the influence of alcohol, can rupture the welcoming atmosphere. Some young migrant adults also spoke of difficulties in getting into bar-cafés, as they did not have official identification documents due to their precarious migration status. In the shopping centres, the experiences of the older people point towards the importance of good public transport connections in accessing the place (see also Alidoust, Bosman, and Holden Citation2019). They also appreciate the possibilities to run multiple errands in proximity and in a sociable atmosphere. The young migrant adults, on the other hand, lament that shopping centres offered quite a limited range of activities besides shopping, eating, and lingering. The potential for conviviality is also hindered by the fact that spending time without spending money was occasionally restricted by the personnel (see Mitchell Citation2017). In our design-based observations, this aspect is emphasised by the commercially flavoured sensory environment filled with sounds, smells, and views designed to increase sales.

Finally, the socio-temporal lens (see ) refers to seasonal and daily rhythms that create changing conditions for conviviality in commercial gathering places. Based on the observation data, the social setup of space is heavily affected by school and working-life schedules. During the daytime, these places are mostly occupied by those outside working life, such as the unemployed, pensioners, and young families (Wallin Citation2019; Van Aalst and Brands Citation2020). Also, Finnish seasons affect the experiences: some young adults consider shopping centres as the only open gathering places during the wintertime, whereas some older residents emphasise that winter conditions create mobility difficulties, making the dial-a-ride bus important for reaching the mall. As the service operates only during weekdays from 9 to 15.30, there are temporal boundaries of access.

4.2. Public activity facilities for leisure time and communities

Activity facilities in our research vary from large public facilities to small local community centres and open urban parks. The importance of such activity facilities is highlighted in both older people’s and young migrant adults’ experiences (see ). Older people shared memories from the time they moved to their neighbourhood regarding how they connected with others and the environment by participating in different activities. Nowadays, these places offer them a sense of community and purposeful activity for days no longer filled by work (see , socio-functional potentials). As can be gathered from this, a sense of place evolves temporally and is never static (ibid., socio-temporal obstacles). For young migrant adults, places where they can receive concrete help, spend time with friends, and feel welcome are highlighted (ibid., socio-spatial potentials).

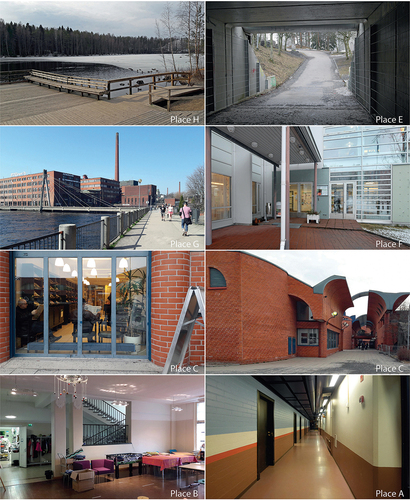

illustrates that when looking at the conditions for conviviality in indoor activity facilities through a socio-spatial lens, several factors intertwine: location, spatial structure, presence and affordances, material characteristics, social settings, and atmosphere. For instance, in Hervanta, larger public facilities are centrally located by a pedestrian axis in connection to commercial services. The composition of distinguishable architecture and a variety of functions could provide potentials for lively urban places. Yet, design-based observations illustrate that the formal setup of open space and sculptural building volumes with separated entrances, winding corridors, and closed spaces works against the potential for vivid encounters (see , Places A and C). The location of the two smaller semi-public community places in Hervanta has unutilised potential to provide a visible presence for local communities, accompanied by several socio-spatial obstacles: the entrances to these ground-floor premises are hidden behind corners and car parks, steep terrain creates accessibility constraints, and outdoor areas are poorly maintained and do not offer enough places for a pause (ibid., Place E). For older people, long walking distances and limitations in transport services create difficulties in accessing the community places.

Figure 6. Observation photographs from public activity facilities. Socio-spatial potentials are supported, inter alia, by sensory characteristics of nature, dignified old buildings, openings connecting facilities to open public space, and open internal spatial structure. Socio-spatial obstacles in turn are caused by deficiencies in accessibility, non-inviting appearances, and rigid boundaries between activity facilities and public space.

Wessendorf (Citation2016, 459) notes that open microspaces of conviviality facilitate experiences of proximity among people with various categorical differences. When viewed through the socio-functional lens (), older people’s and young adult migrants’ lived experiences illustrate that in activity facilities encounters are facilitated by and built upon a common interest, faith, practical need, life situation, or group identity. Hence, these places create more homogeneous social settings compared to shopping centres. However, it is noteworthy that the Hervanta library is being widely used by both groups. Variety in lived experiences suggests that limited access can either obstruct conviviality or enable it by offering a safe space for meaningful encounters (). Despite some criticism, older people in general perceived community centres as important places and spoke of various activities, voluntary work, and meals they enjoy there. Some had a long history of attending the smaller communal place (Place E), which has enabled them to form long-standing relationships. The young migrant adults, again, mentioned that Tampere lacks places that offer activities and encounters between inhabitants from different backgrounds. According to one migrant adult, the multiactivity house in the city centre is the closest thing to a cultural centre in Tampere that gathers diverse people together. Spatially, the internal structure of the multiactivity house consists of a central staircase and open spaces that combine the activity rooms and create communication between the activities (, Place B). Yet, socially, the place has a specific target group, excluding people over 30 years of age.

The socio-functional lens highlights the role of public green areas in offering places for activities and social gatherings for different ages and lifestyles (). Both lived experiences and design observations point to the importance of having a connection to nature, with its biotic and abiotic components (plants, birds, sunlight, water). Nature provides moments of sensory relief that are longed for in the city (, Place H). For older people, good walking routes and the presence of wildlife in Hervanta were important, in part because nature enables meaningful social activities (see ). Lived experiences illustrate the potentials of the genuinely public urban green space in creating conviviality with acquaintances and strangers, and enabling spatial occupation for more private occasions, such as the picnics and football games that were mentioned by the young migrant adults (see also Van Aalst and Brands Citation2020). Nevertheless, negative experiences such as intimidation or harassment can create no-go areas in public spaces that inhibit these potentials (Mitchell Citation2003; Madanipour Citation2011).

From a socio-temporal perspective (), seasonal changes restrict recreational uses and create needs for diverse communal places, as suggested by the experiences situated in commercial places. Both older people with mobility impairments and young migrant adults experience significant changes in their use of outdoor spaces during the winter, which causes variation in the temporal experience of social isolation (Kwan Citation2013, 1080). Two young adults expressed this emphatically, stating that their time flies during the summer, but during the winter they have no place to go, and people in general turn quiet (see ). In contrast, some older people lament that during the summertime, all prearranged activities are on a break.

5 Promoting conviviality through experience-based spatial design

In our analysis, experience-based knowledge was formed by categorising lived experiences of the places systematically along social, temporal, spatial, and functional factors of conviviality (see ). Experience-based design knowledge was then coined by combining design-based observations and lived experiences together under the shared categorizing lenses. In translating the knowledge into actionable inputs for design against segregation (Talen 1006, 234), the identified categorisations need to be re-integrated into relational information that concerns both desirable spatial conditions and related social processes.

In this combination, the analysis of lived experiences reveals local social contexts and their individual and communal distinctions that would otherwise remain invisible for design. In turn, design-based observations point to functional and sensory characteristics in the environment that affect the perceived attractiveness of a place, which can also work in exclusionary or non-exclusionary ways. The characteristics that people appreciate in a place should be endorsed, but not in ways that create boundaries between certain user groups and larger urban publics. Social norms and attitudes attached to a place, as well as material amenities (e.g. benches), can create both potentials and obstacles for meaningful encounters, and for design against segregation. Microspaces of conviviality in the physical environment cannot be designed without understanding the richness and fluidity of lived experiences (see Jull, Giles, and Graham Citation2017). This implies that design against segregation needs to be based on a processual understanding of urban space that recognises constant negotiations and re-negotiations between diverse people who experience, use, and claim spaces in different ways.

To push our analysis further, we suggest two examples of design against segregation, in which the developed experience-based design knowledge discussed in the previous section is utilized in a form of visions that motivate design actions and interchanging pathways that highlight the entanglement of potentials and obstacles in those actions. These visions and pathways are not fixed outcomes to be implemented as such. When applied, the underlying knowledge-base needs to be adjusted to local social circumstances that may aid or inhibit conviviality, as well as the affective and sensory dimensions of space that organise social conduct (Wise and Noble Citation2016, 427). Hence, they present a framework of steps taken to motivate changes that promote convivial encounters in diversifying urban environments and tackle the segregation of places.

5.1. Active living rooms – design for non-exclusionary multifunctionality

Attractive functions, such as sports and other leisure activities, gather people to a place. The vision of active living rooms (see ) underlines the role of shared activities in forming a basis for meaningful contacts. Action towards this vision is instigated by a combination of social, spatial, functional, and temporal factors that advance the accessibility, multifunctionality, and flexible use of urban space.

Peattie (Citation1998, 250) highlights open conviviality between strangers in public space but yet places the domain of conviviality more to the private sphere. Overcoming the public–private distinction calls for a notion of accessibility that is both physical and social. In active living rooms, meaningful activities are visibly located close to public transport connections and daily routes where people casually spend time, which increases the potential for encounters between different people (Gehl Citation2010, 22; Tonkiss Citation2013, 76). Though experiential data reveal that these encounters may give rise to positive, neutral, or even negative experiences, physical and social access to activities enables taking active roles and identifications that can help to negotiate and overcome differences (Fincher and Iveson Citation2008, 154–59). In addition, accessibility requires functional motivations and spatial amenities that are affected also by social, cultural, and personal differences.

Multifunctionality is an instrumental pathway towards the vision. A mixture of necessary, optional, and social activities (Gehl Citation1987; Baeza, Cerrano, and Männigo Citation2017) increases the vitality of the place and contributes to an image that is not fixed to specific user group. For example, seemingly permanent spatial occupation by one group can easily exclude others (Mitchell Citation2003; Van Aalst and Brands Citation2020) and result into segregation by choice. Nevertheless, our study indicates that the focus should not be on the activity targets of a place (Talen Citation2006) but on the needs and experiences of the people using it, who collectively create space through their actions.

To spatially prevent or minimise the conflict-inducing potential of encounters, active living rooms need to offer possibilities for separated activities as well as “interim” spaces where resulting segregation can be “controlled”). This calls for spatial flexibility that allows user control over the see-and-hear connections. Soft boundaries implemented with, for example, temporal spatial occupation and related practices, from booking a space to setting it up for the intended purpose, are part of creating purposeful conditions for convivial encounters. Socially, active living rooms need to have clear policies for reporting and processing instances of harassment, discrimination, or conflict and offer diverse users a possibility to negotiate differing views.

Incorporating social and experiential aspects into urban design is important, as encounters in public places often do not happen under equal premises but involve struggles for power and conflicting claims over the right to the space. A path towards active living rooms may need the prevention of exclusionary spatial identities, for example, by bridging events targeted to other than the dominant user groups.

5.2. Urban oases – Design for the multiplicity of senses

Our analysis suggests that microspaces of conviviality emerge in relaxed, comfortable, and respectful environments. Urban life is heavily loaded with affective sensory irritations: noise, pollution, and rushing through crowds. Experiences of gazes, comments, or touches all add to the stressfulness of urban space. Spatial segregation operates in reciprocal relation to these characteristics (Cucca Citation2020). In the vision of urban oases (see ), places, in which body and mind can have a moment of rest (cf. Gehl Citation2010; Pallasmaa Citation2005), are evenly distributed and developed to increase inclusion in the city (Cucca Citation2020, 187).

The pathway towards urban oases begins from the recognition that diversity in the city should not be met by overly engineered precision, social control, and the (assumed) neutrality of average solutions (Tonkiss Citation2013, 141–43). Rather, emphasis needs to be placed on the multiplicity of senses and experiences (Pallasmaa Citation2005). Our experience-based data highlights the importance of multisensory natural elements, such as green views or the sounds of moving water in the urban environment. Urban nature can be enjoyed alone, or the experience can be shared with friends or strangers in the same place. Functional and temporal variety in urban nature and microclimatic conditions, such as temperature, sunlight, and shade, create versatile conditions for activities and diverse encounters (see Mehta Citation2014, 127). Also, interior amenities, such as a cosy corner with appropriate furniture, pleasant acoustics and lighting, or an interesting view can create an inviting, relaxed, and inclusive image to a place. Limited or unevenly distributed spatial amenities can nevertheless cause social struggles over who gets to use them.

A multisensory perspective on the urban oasis considers the experiential differences of diverse users, which affect the possibilities for creating private or shared moments in urban space. Embodied experiential aspects of materiality (Shafaieh Citation2019), such as shared bodily experiences in a public sauna, can offer pleasing visual and haptic settings for encounters. On the other hand, one unpleasant factor, be it sensory (such as unintended sounds and smells) or social (like the experienced negative conduct of others), can prevent activities and repel people. Aspects of practicality and neutrality in the environment may lead to excluding institution-like atmospheres that prohibit contacts between people and their surroundings (ibid.). The smell of freshly baked buns or a soundscape of friendly conversations may create a feeling of comfort for in-group members, but for others they can indicate privacy not to be disrupted. Our experience-based data illustrate that the conditions of conviviality are diverse; places intended to foster non-exclusionary encounters can be (in)accessible both physically and socially. We concur that non-exclusionary operating practices within urban oases form a necessary basis for non-exclusionary convivial encounters.

6. Conclusions

As cities struggle to respond in a socially sustainable and inclusive manner to increasing diversity, an empirically grounded view of how the spatial fabric in the city could be moulded to prevent segregation of places and promote conviviality among diverse inhabitants is urgently needed. A wide range of expertise is required to address tensions between the experiential and material aspects in the urban environment and the social, political, and design-related dimensions of urban conditions. Also interchange between different knowledge bases is needed.

Spatial design practices encompass capacities to deal with issues that affect the lived experiences and interactions of people in urban space, but which fall outside the legally defined processes of planning. Experience-based information in design can bring out places and networks of places that people find relevant in their everyday lives and highlight the variety of lived experiences in a place. Yet there remains a need to translate situated experiential information regarding the diversity of the urban everyday into information applicable in design tasks (Talen Citation2006). This article has shown that by placing subjective experiences on a map, it is possible to follow diverse inhabitants’ experiences in urban space, and to add other layers, such as design-based observations, onto them. An understanding of social factors cutting across spatial, functional, and temporal factors creates interdisciplinary openings for analysing the possibilities and obstacles for conviviality. Furthermore, reflecting the knowledge through design-oriented visions and interchanging pathways that originate from both the social and spatial aspects of the urban context can yield insights into creating microspaces of conviviality and thus designing against segregation.

Social visions in the context of urban design have been criticised as romanticised notions from past urban life (Madanipour Citation2020). Nevertheless, utopian visionary thinking has affected urban developments as a motivator in the search for better urban environments. In our case, visions work as the final act to translate lived experiences of urban places to design information. We acknowledge that the derived visions do not work as actual aims, yet they create starting points, from which the social and material processes towards designing against segregation can begin. It is here that the value of experience-based knowledge for spatial design lies. Experience-based spatial design can be useful in promoting equitable access to and inclusivity of urban space. It brings the interrelationship between the public and private spheres in urban space to the fore. Non-exclusionary urban places allow room for necessary daily activities and optional recreation, as well as for enjoying the space in a more passive manner for communal and personal purposes. Experience-based spatial design builds on the idea that places are not static, but their qualities vary in time and for different users based on their previous experiences, differing life situations and negotiations over the use of space.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to the participants of this research. We would also like to thank both research assistant Imran Adan in data collection and Henna Kuitunen for her work with the “Experienced Tampere” map. In addition, we want to thank members of research groups Tampere Centre for Societal Sustainability and ASUTUT - Sustainable Housing Design at Tampere University, the researchers in Dwellers in Agile City project, and the editor and anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback on earlier drafts of the article. Any shortcomings remain our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katja Maununaho

Katja Maununaho is an architect and a doctoral researcher at ASUTUT Sustainable Housing Design research group at the School of Architecture at Tampere University. Her research focuses on the relations of spatial, functional, cultural, and social factors in urban housing environment and on the questions of inclusive design in the context of increasing diversity in urban dwellers everyday life.

Eeva Puumala

Eeva Puumala is a senior researcher at the Tampere Peace Research Institute at Tampere University. Her research focuses on community, coexistence, the body, and political agency. She is particularly interested in the practices through which communities are produced, enacted and their boundaries contested in the context of everyday encounters.

Henna Luoma-Halkola

Henna Luoma-Halkola is a doctoral researcher in the field of social policy at Tampere University, Finland. Her research focuses on independent living and mobilities of older people in the context of Ageing in Place- policy.

Notes

1. https://citynomadi.com/route/801d322b2f105f31bc345db0fee07767&uiLang=fi. The initial data processing for the map utilised activity categories presented by Baeza, Cerrone, and Männigo (Citation2017)

2. In quotations, the names of places have been replaced with generic expressions, such as “a café.”

3. The interviewed people were not present during the observations.

References

- Alidoust, S., C. Bosman, and G. Holden. 2019. “Planning for Healthy Ageing: How the Use of Third Places Contributes to the Social Health of Older Populations.” Ageing & Society 39 (7): 1459–1484. doi:10.1017/S0144686X18000065.

- Amin, A. 2002. “Ethnicity and the Multicultural City: Living with Diversity.” Environment and Planning A 34: 959–980. doi:10.1068/a3537.

- Andrews, F. J., L. Johnson, and E. Warner. 2020. “Lived Experiences of Community in an Outer Suburb of Melbourne, Australia.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 11 (3): 257–276. doi:10.1080/17549175.2017.1363077.

- Back, L., and S. Sinha. 2016. “Multicultural Conviviality in the Midst of Racism’s Ruins.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (5): 517–532. doi:10.1080/07256868.2016.1211625.

- Baeza, J. L., D. Cerrone, and K. Männigo. 2017. “Comparing Two Methods for Urban Complexity Calculation Using the Shannon-Wiener Index.” In WIT Transactions on Ecology and Environment, edited by C. A. Brebbia, E. Marco, J. Longhurst, and C. Booth, Vol. 226, 369–378. Ashurst (Southampton): Ashurst: WIT Press.

- Bailey, N. 2020. “Understanding the Processes of Changing Segregation.” In Handbook of Urban Segregation, edited by S. Musterd, 367–377. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Cucca, R. 2020. “Spatial Segregation and the Quality of the Local Environment in Contemporary Cities.” In Handbook of Urban Segregation, edited by S. Musterd, 185–199. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Faehnle, M., P. Bäcklund, L. Tyrväinen, J. Niemelä, and V. Yli-Pelkonen. 2014. “How Can Residents’ Experiences Inform Planning of Urban Green Infrastructure? Case Finland.” Landscale and Urban Planning 130: 171–183. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.07.012.

- Fincher, R., and K. Iveson. 2008. Planning and Diversity in the City. Redistribution, Recognition and Encounter. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gehl, J. 1987. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. Copenhagen: Danish Architectural Press.

- Gehl, J. 2010. Cities for People. Washington: Island Press.

- Hiss, T. 1990. The New Experience of Place: A New Way of Looking at and Dealing with Our Radically Changing Cities and Countryside. London: Vintage.

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books.

- Jull, J., A. Giles, and I. D. Graham. 2017. “Community-Based Participatory Research and Integrated Knowledge Translation: Advancing the Co-creation of Knowledge.” Implementation Science 12 (1): 150. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0696-3.

- Kwan, M.-P. 2013. “Beyond Space (As We Knew It): Toward Temporally Integrated Geographies of Segregation, Health, and Accessibility.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103 (5): 1078–1086. doi:10.1080/00045608.2013.792177.

- Laurier, E., and C. Philo. 2006. “Cold Shoulders and Napkins Handed: Gesture of Responsibility.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 31 (2): 193–207. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2006.00205.x.

- Leino, H. , and Puumala, E. 2021 What can cocreation do for the citizens? Applying co-creation for the promotion of participation in the city. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 39 (4) 781–799 .

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., M. Brozen, and L. Levy-Storms. 2014. “Placemaking for an Aging Population: Guidelines for Senior-Friendly Parks.” UCLA: The Ralph and Goldy Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/450871hz

- Low, S., D. Taplin, and S. Scheld. 2005. Rethinking Urban Parks: Public Space and Cultural Diversity. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Lynch, K. 1995/1984. “The Immature Arts of City Design.” In City Sense and City Design, edited by T. Banerjee and M. Southworth, 498–510. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Madanipour, A. 2014. Urban Design, Space and Society. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Madanipour, A. 2011. “Social Exclusion and Space.” In City Reader, edited by R. T. Legates and F. J. Stout, 186–191. Hoboken, NY: Routledge.

- Madanipour, A. 2020. “Can the Public Space Be a Counterweight to Social Segregation?” In Handbook of Urban Segregation, edited by S. Musterd, 170–184. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Malpas, J. E. 2018. Place and Experience: A Philosophical Topography. London and New York: Routledge.

- Maununaho, K. 2016 Political, Practical and Architectural Notions of the Concept of the Right to the City in Neighbourhood Regeneration. Nordic Journal of Migration Research 6 (1) doi:10.1515/njmr-2016-0008 .

- Mehta, V. 2014. The Street. A Quintessential Social Public Space. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mitchell, D. 2003. The Right to the City. Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. London: Guilford Press.

- Mitchell, D. 2017. “People’s Park Again: On the End and Ends of Public Space.” Environment and Planning A 49 (3): 503–518. doi:10.1177/0308518X15611557.

- Musterd, S. 2020a. “Urban Segregation: Contexts, Domains, Dimensions and Approaches.” In Handbook of Urban Segregation, edited by S. Musterd, 2–18. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Musterd, S. 2020b. “Towards Further Understanding of Urban Segregation.” In Handbook of Urban Segregation, edited by S. Musterd, 411–424. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Nijs, G., and A. Daems. 2012. “And What if the Tangible Were Not, and Vice Versa? on Boundary Works in Everyday Mobility Experience of People Moving into Old Age: For Daisy (1909–2011).” Space and Culture 15 (3): 186–197. doi:10.1177/1206331212445962.

- Oldenburg, R. 1989. The Great Good Place. Cafés, Coffee Shops, Booksrores, Bars, Hair Salons and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. Cambridge: Da Capo Press.

- Ottoni, C. A., J. Sims-Gould, M. Winters, M. Heijnen, and H. A. McKay. 2016. “‘Benches Become like Porches’: Built and Social Environment Influences Older Adults’ Experiences of Mobility and Wellbeing.” Social Science & Medicine 169: 33–41. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.044.

- Pallasmaa, J. 2005. The Eyes of the Skin. Architecture and the Senses. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- Peattie, L. 1998. “Convivial Cities.” In Cities for Citizens, edited by M. Douglass and J. Friedmann, 247–253. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Radice, M. 2016. “Unpacking Intercultural Conviviality in Multiethnic Commercial Streets.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (5): 432–448. doi:10.1080/07256868.2016.1211624.

- Saikkonen, P., K. Hannikainen, T. Kauppinen, J. Rasinkangas, and M. Vaalavuo. 2018. “Sosiaalinen Kestävyys: Asuminen, Segregaatio Ja Tuloerot Kolmella Kaupunkiseudulla.” Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos, raportteja 2/2018.

- Sandercock, L. 2003. Cosmopolis II: Mongrel Cities in the Twenty-First Century. London: Continuum.

- Sennett, R. 1990. Conscience of the Eye. New York: Norton.

- Shafaieh, C. 2019. “On Materiality Kinfolk, and Norm Architects.” The Touch. Spaces Designed for the Senses. Kinfolk & Norm Architects. Berlin: Gestalten 128–129

- Skifter Andersen, H. 2002. “Excluded Places: The Interaction between Segregation, Urban Decay and Deprived Neighbourhoods.” Housing, Theory and Society 19 (4): 153–169. doi:10.1080/140360902321122860.

- Talen, E. 2006. “Design that Enables Diversity: The Complications of a Planning Ideal.” Journal of Planning Literature 20 (3): 233–249. doi:10.1177/0885412205283104.

- Tonkiss, F. 2003. “The Ethics of Indifference. Community and Solitude in the City.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 6 (3): 297–311. doi:10.1177/13678779030063004.

- Tonkiss, F. 2013. Cities by Design. The Social Life of Urban Form. Cambridge: Polity Press. iBooks version.

- Valentine, G. 2008. “Living with Difference: Reflections on Geographies of Encounter.” Progress in Human Geography 32 (3): 323–337. doi:10.1177/0309133308089372.

- Van Aalst, I., and J. Brands. 2020. “Young People: Being Apart, Together in an Urban Park.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability. doi:10.1080/17549175.2020.1737181.

- Van Melik, R., and R. Pijpers. 2017. “Older People’s Self‐Selected Spaces of Encounter in Urban Aging Environments in the Netherlands.” City & Community 16 (3): 284–303. doi:10.1111/cic0.12246.

- Wallin, A. 2019. “Kaupunkitilan ja Eläkeläisten Sosiaalisen Toiminnan Tarkastelua.” PhD diss., Tampere University.

- Warf, B., and S. Arias. 2009. “Introduction: The Reinsertion of Space into the Social Sciences and Humanities.” In The Spatial Turn. Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by B. Warf and S. Arias, 1–10. London: Routledge.

- Wessendorf, S. 2016. “Settling in a Super-Diverse Context: Recent Migrants’ Experiences of Conviviality.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (5): 449–463. doi:10.1080/07256868.2016.1211623.

- WHO. 2007. “Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide” World Health Organization. Accessed 14 April 2020. https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf

- Whyte, W. H. 1980. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Washington, DC: Conservation Foundation.

- Wise, A., and G. Noble. 2016. “Convivialities: An Orientation.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 37 (5): 423–431. doi:10.1080/07256868.2016.1213786.