Abstract

Purpose

Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) data for the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) indicates a concerning increase in the proportion of children who are at risk or developmentally vulnerable in the domains of communication and general knowledge, and language and cognitive skills. This study investigated the effectiveness of speech-language pathologist and educator collaboration to build educator capacity to promote oral language and emergent literacy skills in preschool children.

Method

A quasi-experimental, pre-test post-test design was used to evaluate the effectiveness of interprofessional delivery of Read It Again – KindergartenQ! on (a) children’s oral language and emergent literacy outcomes, (b) educators’ oral language and emergent literacy instructional practices, and (c) quality of the classroom environment.

Result

Children demonstrated improved print knowledge and narrative skills. One of the two educators demonstrated a significant increase in their use of oral language and emergent literacy promoting strategies in their day-to-day interactions with children. No significant changes were observed in the classroom environment.

Conclusion

Interprofessional collaboration with a coaching component is an effective method of improving children’s emergent literacy skills and educator instructional practices.

Introduction

The Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) is a nationwide data collection instrument administered every 3 years to children in their first year of formal schooling. It captures data related to five areas of early childhood development (physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills [school based], and communication skills and general knowledge), referred to as domains of functioning. Consistent with national trends, the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), one of Australia’s six states and two territories, is experiencing concerning and consistent increase in the proportion of children considered at risk or developmentally vulnerable in one or more domains of functioning upon entry to school. The 2021 AAEDC results for the ACT indicated that 16.9% of children during their first year of school were identified by their teachers as not being developmentally on track for language and cognitive skills (ACT Government Community Services, Citation2022). This is an increase from 15.8% in 2018 and 13.4% in 2012 (AEDC, Citation2021) showing a negative trend for children in Canberra. The AEDC (Citation2021) also reported that 28.4% of ACT children were at risk or developmentally vulnerable in the domains of communication skills and general knowledge; this is higher than the national average of 23%. In particular, the districts of Belconnen and Tuggeranong tend to be the lowest performing in the ACT, demonstrating a consistent increase in the proportion of children with developmental vulnerabilities in four out of the five AEDC wellbeing domains since 2009. These statistics match well with parent report data, with approximately 25% of parents from a nationally representative sample of 4–5-year-old children having concerns about their child’s communication skills (Harrison et al., Citation2009).

Children who enter school with lower oral language and emerging literacy skills than their peers typically stay behind (Cabell et al., Citation2013; Dickinson & Porche, Citation2011; Spira et al., Citation2005). Further research demonstrates that children with diagnosed oral language impairments are at significant risk of reading disabilities in later school years (Catts et al., Citation2002). Although the growth trajectory and pattern of progression is similar between children with speech and language concerns and typically developing peers, Australian research suggests that children who enter school with lower speech and/or language proficiency do not catch up to the levels of literacy and numeracy achieved by their typically developing peers (McLeod et al., Citation2019).

The consequences of early difficulty with oral language and emergent literacy skills are not only associated with lower academic achievement, but also lower functional literacy skills, poorer vocational prospects, and mental ill-health (Law et al., Citation2009). Early literacy concepts, knowledge, and skills serve as strong indicators of future reading success in children. The National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy (Rowe, Citation2005) describes five main skills required for later reading success as being phonemic awareness, reading comprehension, vocabulary, phonics, and fluency. The acquisition of these skills is founded on strong oral language and emergent literacy skills in early childhood.

Oral language skills primarily refer to vocabulary, grammar (syntax and morpheme knowledge), and higher order skills such as inferential comprehension at the discourse level (Lervåg et al., Citation2018; Pullen & Justice, Citation2003). Oral language abilities are acquired at a young age, prior to print-based concepts such as sound–symbol correspondence and decoding (Lervåg et al., Citation2018). Additionally, oral retell and composition (narrative skills) have been extensively studied for their contributions to literacy abilities and as crucial oral language skills (Kim et al., Citation2015).

Emergent literacy skills refer to skills, knowledge, and attitudes that develop prior to conventional forms of reading and writing (Whitehurst & Lonigan, Citation1998). These include language and narrative skills but also knowledge of print format, letter name knowledge, knowledge of letter–sound correspondence, phonological awareness, phonological memory, rapid naming skill, and interest in print and shared reading (Whitehurst & Lonigan, Citation1998). Young children’s acquisition of phonological awareness and print awareness influences their subsequent reading achievement. Phonological awareness refers to a child’s implicit and explicit sensitivity to the phonological components that make up the sublexical structure of spoken language (Pullen & Justice, Citation2003). Phonological awareness skills include sensitivity to individual sounds within words, the ability to blend and segment these sounds, recognising words that rhyme, and identifying the syllables in a word. Particularly critical for later reading success is phonemic awareness, the sensitivity to individual sounds within words and the ability to manipulate these (Ehri et al., Citation2001). Studies have demonstrated that children with strong phonemic awareness skills become more proficient readers than children without these skills (McNamara et al., Citation2011). Another important component of emergent literacy is print knowledge. Print knowledge reflects a child’s ability to understand that print carries meaning (Mason, Citation1980), is comprised of symbols and signs (letters, words, punctuation marks etc.; Bayraktar, Citation2018), and follows certain conventions (for example, moves left to right; Adams, Citation1990). This is seen to be a crucial initial step in comprehending the idea of print-to-speech mapping, which is essential for reading acquisition (Justice & Ezell Citation2001; Pullen & Justice, Citation2003). Most children learn these skills during their preschool years, which helps lay the groundwork for later reading success (Pullen & Justice, Citation2003; Wagner & Torgesen, Citation1987).

Even though the brain is biologically wired to develop language innately, the type, quality, and quantity of oral language to which a child is exposed is of vital importance, and children who are not exposed to a rich oral language environment may demonstrate delayed language development (Hammer et al., Citation2014; McKean et al., Citation2016; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Citation2017). Similarly, the quality of the early literacy environment and the extent to which children are exposed to story reading, storytelling, and other emergent literacy concepts and skills are also important predictive factors for children’s later literacy success (e.g. Burgess et al., Citation2002; Sénéchal & LeFevre, Citation2014).

Attendance at quality, formal early childhood education and care centres (ECEC) is also considered to be a facilitative factor for children’s school readiness. Up to 80% of Australian children attend ECEC prior to starting school (Goldfeld et al., Citation2016), therefore, early childhood educators (henceforth, educators) have the potential to play a critical role in promoting oral language and emergent literacy skills. Yet the quality of ECECs varies considerably (Sammons et al., Citation2002; Tayler et al., Citation2016). Longitudinal research from two Australian states (Victoria and Queensland) found that ECEC quality varies as a result of: socioeconomic status, with higher quality centres being found in areas of higher socioeconomic status; type of service, with preschools having higher overall quality than long-daycare centres; and the quality domain considered, with emotional support and classroom organisation rated more highly than instructional support (Tayler et al., Citation2013). There is a need to raise the quality of instruction in early childhood classrooms across all socioeconomic areas and all types of early childhood services.

High-quality training for educators facilitates their ability to identify children with communication support needs (Dockrell et al., Citation2014), however, most educators report having little or no training in this area (Brebner et al., Citation2016; Mroz Citation2006; Mroz & Letts, Citation2008). There are a variety of training pathways to become a qualified educator in Australia and significant variation in the depth and breadth of preservice training around oral language and emergent literacy (Mroz, Citation2006; Weadman et al., Citation2021). An Australian nationwide review of the oral language and emergent literacy content of tertiary education courses for educators found large variations amongst training institutions. Education on language structure and code-related emergent literacy skills such as phonological awareness and print awareness featured in less than 15% of early childhood education courses (Weadman et al., Citation2021), and content around adult-child interactions was also limited (Weadman et al., Citation2021). The analysis of course outlines did not find any explicit mention of other code-focused abilities like print knowledge (Weadman et al., Citation2021). Yet, international evidence has consistently demonstrated that children’s phonological awareness and print awareness abilities are strong indicators of later code-based literacy development (Alonzo et al., Citation2020; Rowe, Citation2005).

There has not yet been similar exploration of the language and literacy related content in vocational training programs, such as diploma and certificate qualifications, yet most staff in an ECEC hold these vocational qualifications rather than tertiary level qualifications (Fenech et al., Citation2009). In Australia, it is a national requirement under the National Quality Framework for 50% of ECEC staff to hold or actively be working towards a diploma level qualification, with all other educators to hold a Certificate III (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority, Citation2022). The requirement for early childhood teachers (ECT) who hold tertiary level qualifications is one per centre under these Australian guidelines.

There is a need for educators to have more training, time, and support to build their capacity to support children’s oral language and emergent literacy development. Many educators believe that their training has not given them the knowledge and abilities needed to recognise and assist children with speech and language issues (Mroz, Citation2006; Weadman et al., Citation2022). In general, the biggest obstacles to educators’ capacity to promote oral language and emerging literacy skills were lack of training, lack of resources, and time pressures (Weadman et al., Citation2020; Weadman et al., Citation2022). This highlights the demanding nature of the job, especially in terms of time, which may prevent educators from taking advantage of professional development opportunities that require them to take time away from their daily duties in the centre (Marshall et al., Citation2002).

The degree of qualification may also have an impact on educators’ eligibility for professional development. Research suggests that those with a bachelor’s or master’s degree have greater access to professional development than educators with lower levels of qualification (Smith & McKechnie, Citationn.d.; Weadman et al., Citation2020). This seems counterintuitive given that diploma and certificate trained educators have received the least amount of subject training in connection to children’s language and emergent literacy development (Weadman et al., Citation2020). Working collaboratively with speech-language pathologists (SLPs) in ECECs may be one way to overcome some of these barriers. SLPs possess specialist knowledge of children’s communication development and can work with educators via professional learning events and collaborative coaching to ensure that all children are provided with language- and literacy-rich early learning environments.

Research suggests that educators feel more confident supporting and working with children with speech/language impairment when they have the opportunity to collaborate with SLPs (Davis, Citation2019; Pfeiffer et al., Citation2019). Similarly, SLPs agree that the most effective model of practice is when they work together with educators (Pfeiffer et al., Citation2019).

One practice that is already common to both professions is book reading. Early storybook reading has been shown to have positive outcomes for young children, including strengthening language skills, social skills, and parent or educator and child bonding/relationships (Brown et al., Citation2018). Sharing stories with young children offers many opportunities to provide rich speech, language, social, and early literacy learning opportunities and experiences for children of all ages. Even the youngest children can engage with storybooks using non-verbal interaction such as eye contact, joint attention, turning the page, or lifting a flap, as well as through verbal responses (Fletcher & Reese, Citation2005).

Storybooks can introduce children to new vocabulary, different types of sentence structures, rhymes, sound patterns, and emotions (Wasik et al., Citation2016). The vocabulary in children’s books is similar to the conversational word choices of college-educated adults (Hayes & Ahrens, Citation1988). Engagement with storybooks can, thus, expose children to tier two words—words that are characteristic of written texts, high utility, but more sophisticated than daily language (Beck et al., Citation2008). Whilst reading to children has several benefits, reading with children and involving them as active participants in the storytelling process has been demonstrated to have an even greater influence on their language and social communication skills (Baker & Nelson, Citation1984; Cleave et al., Citation2015; Girolametto & Weitzman, Citation2002).

Read It Again – PreK! (Justice & McGinty, Citation2013) is an evidence-based curricular supplement designed for educators to enable embedded explicit instruction of two oral language (vocabulary, phonological and phonemic awareness) and two emergent literacy (narrative/story structure, print knowledge) skills known to facilitate improvements in children’s school readiness, delivered in the context of shared storybook reading. It was collaboratively developed by educators, state policy makers, and SLPs in the USA and has been adapted for use in the Australian context by SLPs working for the Department of Education in Queensland. There are two Australian adaptations. Read It Again – FoundationQ! (Liddy et al., Citation2013) is intended for children in their first year/foundation year of formal schooling. Read It Again – KindergartenQ! (Peach & Nicholls, Citation2016) is intended for children in the year prior to commencing formal schooling (often known as preschool). All versions of Read It Again focus on skills related to vocabulary, phonological and phonemic awareness, print knowledge, and narrative/story structure. Each version of Read It Again follows a specific scope and sequence for each of the four areas of oral language and emergent literacy targeted, and offers facilitators a set of scaffolding strategies to differentiate instruction to individual children’s skill levels, plus a progress monitoring guide (Mashburn et al., Citation2016).

Published evaluations of Read It Again – PreK! have predominantly been conducted in the USA, in regions where there are high proportions of low-income families and children considered to be both economically and educationally at risk. These studies have had mixed results, both on children’s language and literacy outcomes, as well as on changes to educators’ instructional practices and classroom quality. For children, some studies have demonstrated a significant intervention effect on both language and emergent literacy measures (Justice et al., Citation2010; McLeod et al., Citation2019; Piasta et al., Citation2015). Other studies have reported a significant effect on emergent literacy skills only (Albritton et al., Citation2018; Mashburn et al., Citation2016). Bleses et al. (Citation2017) also reported improvements to emergent literacy skills only in their study, which adapted Read It Again for the Danish context and implemented lessons in small groups rather than at the level of the whole classroom. Others reported significant effects only for language and print measures but not for phonological sensitivity measures (Hilbert & Eis, Citation2014). For educators, including those who delivered Read It Again in a dual language environment (i.e. in Spanish as well as English; Durán et al., Citation2016), studies report highly variable fidelity of adherence to the lesson plans (Albritton et al., Citation2018), particularly concerning time spent on the lessons (Durán et al., Citation2016; Piasta et al., Citation2015), completing both activities in the lesson (Durán et al., Citation2016), and using the scaffolding strategies to support children’s learning (Durán et al., Citation2016; Piasta et al., Citation2015). Quality of instruction can vary between learning objectives, as reported by Piasta et al. (Citation2015), with educators providing higher quality instruction on print knowledge and narrative than for phonological awareness and vocabulary. The same authors found significant increases in educators’ provision of instruction on all learning objectives (Piasta et al., Citation2020), however, the children in this study included those with disabilities and those in special education classrooms, as well as typically developing children. These pre-intervention differences between groups of children acted as a confound on the findings. Overall, the children demonstrated no changes to their language and emergent literacy skills (Piasta et al., Citation2020). Despite these mixed results, Read It Again (all versions) holds high appeal for its low cost, scripted lessons, ease of use, and general utility as a curriculum supplement within the day-to-day routines of an ECEC. Furthermore, it requires no specific training to access or to implement.

Aims

This study aimed to explore whether interprofessional delivery of the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! curriculum supplement, with the inclusion of a coaching component for early childhood educators, can facilitate:

Improvements in children’s phonological awareness, vocabulary, narrative comprehension or generation, and print awareness skills;

Changes to educators’ book reading and oral instructional practices; and/or

Environmental changes in the ECEC.

This study adopts a novel approach to the program’s implementation by introducing interprofessional delivery of lessons by both SLPs (in this case, student SLPs) and educators, with an added SLP-led coaching and feedback component for educators. The feedback and coaching component have been a notable absence from most previous evaluations of Read It Again – PreK!, yet coaching is considered a critical component to adult learning (Markussen-Brown et al., Citation2017). The exception to this is the work of Albritton et al. (Citation2018), whose research included providing feedback on implementation fidelity to participating educators but only measured children’s outcomes for phonological awareness. This is also the first evaluation of any version of Read It Again that explores changes to educators’ book reading practices, environmental level changes, as well as changes to children’s oral language and emergent literacy skills.

Method

Design

This study utilised a quasi-experimental, pre-test-post-test design to investigate the effects of interprofessional delivery of the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! (Peach & Nicholls, Citation2016) curriculum supplement on classroom environment; educators’ interaction and communication styles, and emergent literacy instructional practices; and preschool children’s oral language and emergent literacy skills. The Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Canberra (10436) approved this study.

Participants

Two ECECs from the Belconnen region of Canberra consented to participate in the study between November 2021 and August 2022. Both were long-daycare services: one not-for-profit and one family owned. Each centre was given an alphanumeric code (RIA000 and RIA100), which was matched to the codes generated for each participating educator and child. One educator participated from RIA000 (ECE0), and two educators participated from RIA100 (ECE1, ECE2). Centre directors and participating educators provided written informed consent.

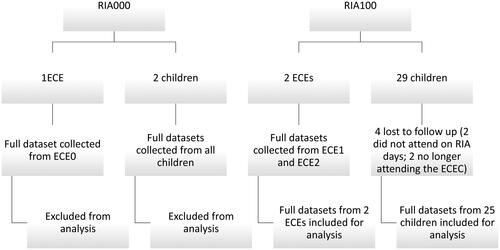

Parents of two children from RIA000 consented for their child to participate in evaluation of the intervention. Prior to analysis, we received advice from a biostatistician that the small sample size of two children from RIA000 would decrease the statistical power of our analyses, with limited added value to the overall results. Therefore, the data from RIA000 were excluded from analysis. Twenty-nine parents from RIA100 provided written informed consent for their child to participate in evaluation of intervention outcomes. Two of the 29 consenting children at RIA100 were not assessed as they would not be attending the centre on the days of the week when Read It Again – KindergartenQ! would be delivered. A further two children from RIA100 were lost to follow up, as they were no longer attending the centre at the conclusion of the program. Pre- and post-intervention data were obtained from 25 children between the ages of 3 and 5 years at RIA100 (See ).

A total of seven Master of Speech Pathology students (sSLP) attended ECECs once per week to deliver the program as part of their clinical placement experiences. Four additional Master of Speech Pathology students participated in collecting pre- and post-intervention data from the children as part of their research coursework. All students had completed coursework relating to general principles of assessment and intervention for paediatric speech, language, and literacy. Prior to commencing any data collection or intervention activities, all students participated in an orientation day during which they received education from their supervising SLP on the learning objectives and scaffolding strategies involved in Read It Again – KindergartenQ! (Peach & Nicholls, Citation2016), principles of adult learning (Dunst & Trivette, Citation2009), and the data collection required. They were provided with opportunities to practice each of the assessment/data collection tasks, as well as the intervention program with one another, and receive feedback from the SLP as needed. The sSLPs were fully supervised in their delivery of Read It Again lessons, with on-the-spot coaching and feedback provided by the supervising SLP when needed.

Intervention

Read It Again – KindergartenQ! (Peach & Nicholls, Citation2016) consists of 32 scripted lessons and activities typically delivered across 16 weeks (two lessons per week). Each week, storybooks are used to target four specific learning objectives known to be predictors of successful literacy acquisition—print awareness, vocabulary, phonological awareness, and narrative macrostructure. Within each broad learning objective, specific subskills are targeted in order of increasing complexity (see Supplementary Materials 1). Two learning objectives are targeted each lesson, with lessons delivered twice weekly using the same storybook, to target all four learning objectives.

Prior to commencing with the intervention program, educators attended a 2-hour professional learning workshop created by the first author, a certified practising SLP with 15 years’ clinical experience working with preschool and school-aged children in the areas of speech, language, and literacy, and 3 years’ experience coaching and supporting sSLPs in the delivery of Read It Again. The workshop was designed using Dunst & Trivette’s (Citation2009) principles of adult learning. First, educators were introduced to the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! program, its structure and learning objectives, the evidence base behind the learning objectives, and the various scaffolding strategies that can be used to support children who find achieving the learning objectives difficult and to extend children who find the learning objectives too easy. Next, several examples, illustrations, and demonstrations of each learning objective were provided by the SLP, followed by a brief demonstration and role play of one of the program’s lessons, also led by the SLP. Finally, educators were provided with a storybook and printed lesson materials and given the opportunity to practice delivering a lesson in a brief role play.

In this study, the program’s implementation was modified to: (a) facilitate interprofessional delivery of the program’s lessons by sSLPs, as well as educators; (b) include explicit demonstration of each learning objective by sSLPs (observe a modelled lesson); and (c) include a coaching component. For the coaching component, educators were observed by a qualified SLP while delivering their weekly Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson (deliver a lesson) and provided with the opportunity to ask questions, reflect on the strengths and opportunities of their lesson, receive feedback on their implementation fidelity, and receive coaching in their use of the various scaffolding strategies that can be used to differentiate the instruction for individual children’s learning needs.

The Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons were reorganised (see Supplementary Materials 2) so that the educator’s lesson would focus on the same two learning objectives that they had seen the sSLPs model earlier in the week. For example, sSLPs delivered Lesson 1 (print knowledge and vocabulary) and demonstrated two learning objectives related to a storybook, while participating educators observed the program’s interactive techniques and scaffolding strategies. sSLPs then handed over the next storybook in the sequence as well as a copy of Lesson 3 (the next lesson to also cover print knowledge and vocabulary) to the educators for their observed lesson later the same week. The following week, sSLPs delivered Lesson 2 (phonological awareness and narrative) and provided the educators with Lesson 4 (phonological awareness and narrative) to be delivered later the same week. Educator-led lessons were observed by a qualified SLP, and educators were provided with the opportunity to engage in feedback and coaching on their lesson delivery and use of scaffolding strategies to support or extend children in learning the language and literacy skills targeted each lesson. This process continued until all lessons of Read It Again – KindergartenQ! had been delivered following the see one, do one model of interprofessional delivery. This reorganisation had the added advantage of ensuring that all children were exposed to all four learning objectives (print knowledge, vocabulary, phonological awareness, and narrative) over the course of the program, regardless of their pattern of attendance at childcare (i.e. full time or part time).

Outcome measurement

Implementation fidelity

Implementation fidelity was measured using a modified version of the fidelity checklist used in Albritton et al (Citation2018; see Supplementary Materials 3 and Table 1). Both sSLPs’ and educators’ intervention fidelity was measured in real time by the supervising SLP. Numeric scores were derived for the number of features observed during the session compared with the total number of features/points available for the lesson and converted to a percentage. Percentages were averaged over the length of the program. Inter-rater reliability was not completed for fidelity checklists given the pragmatic nature of the intervention (in real time within ECECs) and lack of ethics approval for recording sessions.

Children’s oral language and emergent literacy skills

The participating children’s language and emergent literacy skills were assessed pre- and post-intervention across four language domains: phonological awareness, narrative structure, oral language, and print awareness. The children were assessed at their ECEC by the sSLPs.

The children’s phonological awareness was assessed using the Preschool and Primary Inventory of Phonological Awareness (PIPA; Dodd et al., Citation2000), a standardised test that consists of six subtests (three for children under 4 years), which assess the child’s ability to recognise, segment, manipulate, and isolate units of sounds within words. The PIPA uses Australian norms, except for the sixth subtest, Letter Knowledge, which was standardised with a cohort of children from the UK (Dodd et al., Citation2000). The PIPA was as selected due to its reported validity and reliability as an effective tool to assess phonological awareness in preschool- aged children.

Children’s narrative skills were measured using the CUBED Narrative Language Measure (NLM) standardised assessment (Petersen & Spencer, Citation2016). The Cubed NLM (Petersen & Spencer, Citation2016) was used to evaluate the children’s narrative retell (including narrative components and use of more complex vocabulary), story comprehension, and personal story generation, and to compare with normative data from preschool-aged children in the USA. For students in preschool through third grade, the CUBED can validly, reliably, and effectively assess key narrative constructs (Petersen & Spencer, Citation2016). Preschool Benchmark Story 1 was used pre-intervention and Preschool Benchmark Story 2 was used post-intervention. Standardised tests (PIPA and CUBED) were scored by sSLPs according to manualised procedures, and converted to scaled and standard scores.

Childrens’ print-concept knowledge was assessed using the Preschool Word and Print Awareness (PWPA) assessment (Justice et al., Citation2006). The PWPA was adapted from the Concepts About Print task (Clay, Citation1979) to be suited to younger children who are not yet reading (Justice et al., Citation2006). It contains 14 items related to understanding how books work and differentiating print from pictures (e.g. front of the book, print vs. pictures, print directionality, first letter etc.; see for more information). Originally published in 2001, the PWPA was piloted on 128 3- to 5-year-old children in Ohio and Virginia, USA. The assessment was conducted using the book Nine Ducks Nine (Hayes, Citation1988) and the protocol/prompts described in Justice et al. (Citation2006). The child and examiner look at the book together and the child was asked to respond to the examiner’s prompts according to the script (Justice et al., Citation2006). For example, “show me where I start to read.” The PWPA generates both a raw score and a composite score to estimate children’s print-concept knowledge (Justice et al., Citation2006). Item response analysis performed by the authors demonstrated that the PWPA is a valid and reliable tool for measuring preschool children’s print-concept knowledge and can be used to monitor children’s performance over time (Justice et al., Citation2006).

Oral language skills were assessed through play-based language samples. The sSLPs were instructed to use naturalistic, child-led play contexts within the ECEC environment to engage in play and conversation with the children (e.g. Miller et al., Citation2016; see also Supplementary Materials 5). Language sampling was included to facilitate analysis of language use in naturalistic settings (Costanza-Smith, Citation2010), to provide a more functional method of measuring lexical diversity, and to measure whether any vocabulary learning from the intervention had generalised into naturalistic conversation. The play format and prompts provided by the assessor allowed the child to describe ongoing events, as well as past and future events. Examiners were responsible for expanding and stimulating dialogues by asking open-ended questions to encourage conversation (Miller et al., Citation2016). The targeted sample length was at least 100 utterances per child, to have sufficient input to compute broad measures of utterance length and lexical diversity (Pezold et al., Citation2020).

Language samples were audio recorded using voice memos on an Apple iPad (5th generation, running iOS 14.1), orthographically transcribed by the researchers, and coded for input into Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) software (Miller & Iglesias, Citation2015). Accuracy checking was completed by the last author for 10% of transcripts. SALT coding was checked for accuracy by the first author for 100% of transcripts prior to input into the analysis software. Reliability was not specifically calculated. This study reports on SALT output for: (a) mean length of utterance (MLU), (b) number of different words (NDW), (c) moving average NDW, and (d) percentage of utterances with errors (control behaviour).

MLU is the average number of morphemes per utterance; it generally indicates a child’s morphosyntactic ability (Pezold et al., Citation2020). NDW counts the number of different words per sample and broadly indicates vocabulary diversity (Miller, Citation1981). Since NDW is dependent on the length of the sample, the moving-average NDW was calculated by averaging the NDW per 100 words, which would provide a more indicative insight into a child’s vocabulary diversity. Percentage of utterances with errors was used as a control since grammatical accuracy was not targeted in the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! program.

Educators’ interaction and communication styles, and literacy practices

Educators’ use of oral language and emergent literacy promoting strategies was assessed pre- and post-intervention using the Interaction, Communication, and Literacy Skills Audit (ICL; El-Choueifati et al., Citation2011). The ICL was designed to be used as either a self-assessment tool for educators or a tool to be used via observation by SLPs working in the education sector. It consists of a series of skills related to six key strategies that can be used in ECECs to support children’s interaction, communication, and literacy development (see ). For each individual skill under the six key strategies, several behavioural exemplars are listed, against which educators are rated on a frequency of use scale from never to all the time. For this study, we focused only on strategies one to five as these were the strategies relevant to educator-child interactions and literacy instructional practices. Observations of the educators and completion of the ICL was conducted by the last author, a qualified SLP and member of the research team. Educators were aware that they were being observed and were asked to go about their day-to-day routine as usual while the SLP spent up to 4 hours conducting fly-on-the-wall observations of the daily routine of the classroom and the educator’s typical interaction, language, and literacy practices.

Table I. Outcome measurements used to evaluate intervention fidelity and child, educator, and environmental changes.

Educators also participated in a Levels of Use (LoU; Hall et al., Citation2006) structured interview pre- and post- participation in the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! program. The LoU was conducted by the last author. Each educator was interviewed individually to explore their knowledge and implementation of the program pre- and post-intervention. Interviews were audio recorded using voice memos on an Apple iPad (5th generation, running iOS 14.1) and transcribed by the last author. Educators’ responses were deductively coded by the first author, using qualitative content analysis (Elo & Kyngas, Citation2008), along a continuum of behaviours/categories according to the LoU framework (see for details of the LoU categories) in order to test the hypothesis that participation in the intervention would lead to changes in educator practice. All coding was completed during the data analysis phase of the research after the conclusion of the intervention.

Classroom language and literacy environment

To explore any environmental changes resulting from participation in the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! program, Sections III, IV, and V of the Early Language and Literacy Classroom Observation (ELLCO; Smith et al., Citation2008) were used. For each component of instructional or environmental quality, the observer provides a rating on a 5-point scale where one indicates minimal support for learning and five indicates exemplary support. The ELLCO was also completed by the last author in a fly-on-the-wall style observation of the classroom environment and day-to-day routine. Educators were aware that the SLP was observing the classroom environment and were asked to go about their daily routine as usual.

Statistical analysis

Implementation fidelity

Average intervention fidelity percentages were calculated for each educator across all the lessons they had delivered over the course of the intervention. Nonparametric statistics were used to account for small sample size and non-normal distribution of data. Average fidelity between educators was compared using the Mann–Whitney U test to determine whether there was any statistically significant difference in fidelity of implementation between educators.

Children’s oral language and emergent literacy skills

Given the part-time attendance of most children at RIA100 and the nested nature of the data (repeated measures of the same individual participants, with participants nested within a key educator), generalised linear mixed models (GLMM) assuming a Poisson distribution were performed in RStudio (RStudio Team, Citation2020) for all count variables (PIPA subtest scaled scores, PWPA raw and composite scores, narrative retell, story comprehension, narrative generation). These models accounted for random effects of within subject variability as well as fixed effects of time, educator assignment, and number of Read It Again lessons received per week. Linear mixed effects modelling (LME) was performed for continuous variables (MLU, NDW, moving average NDW, and percent utterances with errors), also accounting for the fixed effects of time, lessons received, and educator assignment.

Educators’ interaction and communication styles, and literacy practices

Average frequency of use of each behaviour and skill were used to perform Wilcoxon signed rank tests for each individual educator comparing pre-intervention use of strategies with post-intervention use of strategies. Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare skills between educators at pre- and post-intervention timepoints. Nonparametric tests were used to account for the small sample size and ordinal data captured by frequency rankings on a 5-point scale.

Educators’ level of use of the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! was analysed descriptively for each educator using simple comparison of their assigned categorical level of use pre- and post- intervention based on coding of the interview data.

Classroom language and literacy environment

Changes to the classroom language and literacy environment were only able to be analysed descriptively with the current sample size of one ECEC.

Result

Implementation fidelity

Implementation fidelity was measured for 45% of all sSLP and educator led lessons with an average fidelity score of 87.2%. Average intervention fidelity for sSLPs was 95.55%. Average fidelity for ECE1 was 85.24% (range 53.12% to 96.87%) and for ECE2 was 83.76% (range 68.75% to 96.77%). There was no statistically significant difference in intervention fidelity between ECE1 and ECE2 (U = 33; p = 0.35).

Children’s oral language and emergent literacy

presents mean, standard deviation, and range information for all variables of interest used in the statistical modelling of children’s outcomes.

Model 1 controlled for fixed effects of educator and time. Model 2 accounted for fixed effects of educator, time, and number of lessons received per week (see ). Overall, Model 2 provided the better fit, however, fixed effects of time, educator, and number of Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons received accounted for between 7 and 21% of the variability in the dependant variables only. Conditional R-squared values suggest that when random effects of the between subject variability on all variables of interest are considered, the model provides only a weak indicator of response to intervention.

Table II. Participant and outcome overview (children).

Table III. Variance explained by fixed effects of time, educator, and lessons received.

Children’s phonological awareness

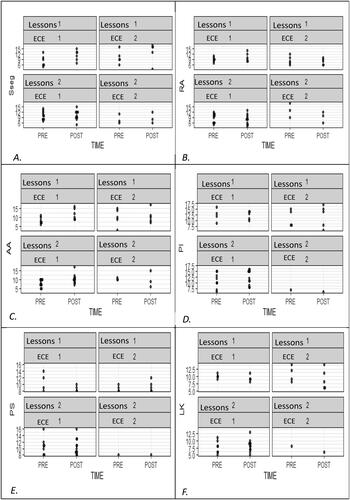

There were no significant effects of time, educator, or number of lessons received, nor any significant interactions between fixed effects found for phoneme identification, phoneme segmentation, and letter knowledge. shows the spread of individual children’s results for each of the six subtests, separated by educator assignment and lessons received.

Figure 2. A to F: ggplot visualisations for phonological awareness skills (ECE1 on the left and ECE2 on the right; one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week on top and two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week on the bottom).

Note. Sseg = syllable segmentation; RA = rhyme awareness; AA = alliteration awareness; PI = phoneme identification; PS = phoneme segmentation; LK = letter knowledge.

Syllable segmentation

There were no significant effects of time, educator, or number of lessons received, nor any significant interactions between fixed effects. Post hoc comparison of means revealed a significant educator effect in favour of ECE1 (p < 0.05). The group of children under ECE1 demonstrated greater improvement between pre- and post-intervention time points, though this did not reach significance (p > 0.05).

Rhyme awareness

There were no significant effects of time, educator, or number of lessons received, nor any significant interactions between fixed effects. Post hoc comparison of means revealed a pre-intervention effect of lessons, with those children attending more days per week (and therefore receiving two lessons of Read It Again – KindergartenQ! per week) demonstrating stronger rhyme awareness pre-intervention than children who attended care fewer days per week. However, these children did not demonstrate greater gains in rhyme awareness than other children post-intervention.

Alliteration awareness

There was a significant effect of time on improvements in alliteration awareness (p = 0.045). There were no other individually significant fixed effects, nor any interaction effects. Children under ECE1 receiving one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week demonstrated a significant increase in alliteration awareness from pre- to post-intervention (p = 0.045). There were no other significant post hoc comparisons.

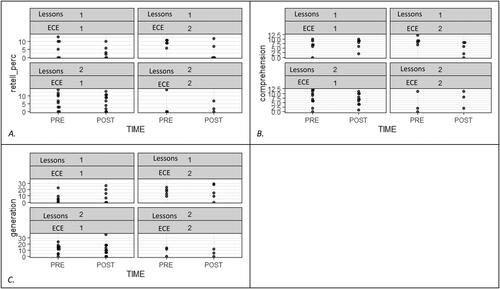

Children’s narrative skills

Story retell

There was a significant main effect of time (p = 0.03). There were no other significant fixed effects. Post hoc comparisons revealed a significant improvement from pre- to post-intervention for children under ECE1, both those receiving one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week (p = 0.027) and those receiving two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week (p = 0.034). Children under ECE2 did not demonstrate any significant pre- to post-intervention change in their story retell skills.

Story comprehension

The effect of time × lessons received was significant (p = 0.02), as was the effect of time × educator × lessons received (p < 0.01). There were no significant effects for any individual fixed effect. Post hoc comparisons revealed a significant pre- to post-intervention improvement in story comprehension skills for those children under ECE1 who received two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week (p = 0.012).

Story generation

There were significant effects of time (p = 0.02) and number of lessons received (p = 0.03), as well as significant interaction effects between time × educator (p = 0.04) and educator × lessons received (p = 0.02). Post hoc comparisons revealed a significant pre-intervention difference in performance between children under ECE1 receiving one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week and children under ECE1 receiving two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week (p = 0.031). The group of children who received two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week began the intervention with significantly higher story generation skills than all other children, regardless of pattern of attendance or educator. These children made no significant gains from pre- to post-intervention. The children under ECE1 receiving one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week made significant gains in their storytelling skills post-intervention (p = 0.02).

illustrates the range of individual children’s results, separated by educator assignment and lessons received.

Figure 3. A to C: ggplot visualisations for narrative skills (ECE1 on the left and ECE2 on the right; one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week on top and two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week on the bottom).

Note. retell_perc = story retell percentage; comprehension = story comprehension score; generation = story generation score.

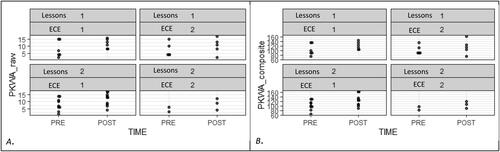

Children’s print knowledge

illustrates the spread of individual children’s results, separated by educator assignment and lessons received. There was a significant main effect of time for both raw scores (p = 0.03) and composite scores (p < 0.01), irrespective of educator assignment or number of lessons received.

Figure 4. A to B: ggplot visualisations for print knowledge (ECE1 on the left and ECE2 on the right; one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week on top and two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week on the bottom).

Note. PKWA_raw = print knowledge and word awareness raw scores; PKWA_composite = print knowledge and word awareness composite scores.

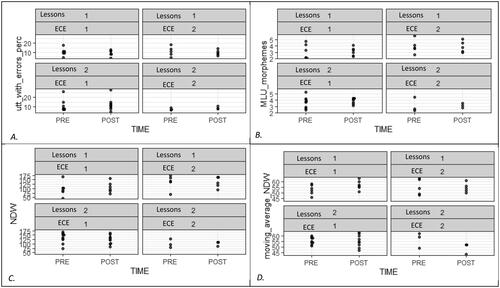

Children’s expressive language

Across the four selected measurements, limited impacts of intervention were found (see ). For mean length of utterance, there were no significant effects of time, educator, or number of lessons received, nor any significant interactions between fixed effects. For NDW, there was a significant interaction effect of educator and lessons received. Post hoc comparisons demonstrated a slight gain in lexical diversity for children under ECE1 who received one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week, though this did not reach significance. For moving average NDW, there were no significant effects of time, educator, or number of lessons received, nor any significant interactions between fixed effects. Post hoc analysis indicated that children under ECE2 receiving two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week demonstrated a significant decrease in moving average NDW between pre- and post-intervention measurement. For percentage of utterances with errors, there were no significant effects of time, educator, or number of lessons received, nor any significant interactions between fixed effects.

Figure 5. A–D: ggplot visualisations for expressive language skills (ECE1 on the left and ECE2 on the right; one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week on top and two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week on the bottom).

Note. utt_with_errors_perc = percent utterances with errors; MLU_morphemes = mean length of utterance in morphemes; NDW = number of different words; moving_average_NDW = moving average number of different words.

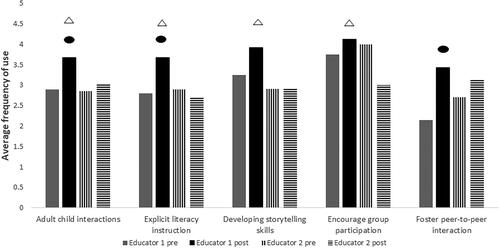

Educators’ interaction and communication styles, literacy practices, and ongoing use of the intervention

compares each educator’s frequency of use of the five composite language and literacy promoting strategies measured on the ICL. There were no statistically significant differences between the two educators in their frequency of use of any of the interaction, communication, and literacy promoting strategies pre- intervention. ECE1 demonstrated an increase in the use of all five strategies on the ICL from pre- to post-intervention. This improvement was statistically significant for three of the five strategies: adult-child interactions (z = −3.07, W = 6, p < 0.01), explicit literacy instruction (z = −2.20, W = 0, p < 0.05), and fostering peer-to-peer interactions (z = −2.37, W = 0, p < 0.05). ECE2 demonstrated no significant change in the frequency of use of any of the five strategies of interest. There was a statistically significant post-intervention difference between ECE1 and ECE2 in frequency of use of four of the five strategies. ECE1 was observed to be engaging in positive adult-child interactions (U = 171, z = −3.34, p < 0.01), explicit literacy instruction (U = 14, z = −2.68, p < 0.01), developing storytelling skills (U = 20, z = −2.97, p < 0.01), and encouraging group participation (U = 9.5, z = −2.31, p < 0.05) significantly more frequently than ECE2.

Figure 6. ECEs frequency of use of language and literacy promoting strategies pre- and post-intervention.

Note. ○ denotes statistically significant improvement for ECE1 from pre- to post-intervention; Δ denotes ECE1 was demonstrating significantly greater use of the strategy than ECE2 post-intervention.

Both educators commenced participating in the program as non-users of Read It Again – KindergartenQ!. By the end of the intervention, ECE1 had progressed to Level IVB (refinement) and was actively adapting the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! strategies and learning objectives throughout the day, in order to continue to benefit the children in her group. ECE2 had progressed to Level III (mechanical use) and reported that she was using some of the program’s strategies and learning objectives some of the time, when it was relevant to the age group of children with whom she was now working.

Classroom language and literacy environment

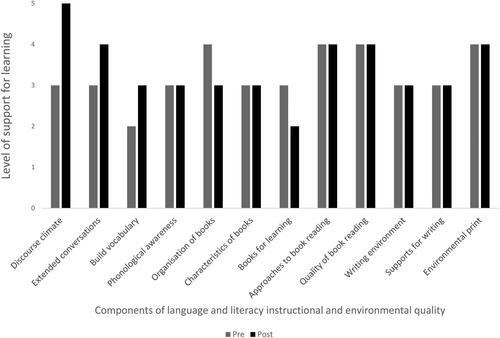

Positive changes to the oral language environment were observed. Improvements in instructional quality were demonstrated on three of the 12 components of language and literacy instructional or environmental quality: discourse climate (basic support pre-intervention to exemplary support post-intervention), extended conversations (basic support to strong support), and building vocabulary (inadequate support to basic support; see ). There were no observed changes to the print and early writing environment, nor were there any significant changes to books and book reading practices.

Discussion

The importance of a rich oral language and emergent literacy environment for preschool-aged children has been well established. However, the capacity for preschools and early childhood education and care centres to provide such quality language and learning environments varies as a result of several factors (e.g. socioeconomic status of the geographic area, type of centre, instructional quality; Tayler et al., Citation2013). Educators report valuing opportunities for professional development and collaboration with other professions and yet, they continue to face barriers such as time constraints, lack of training, and lack of resources, including financial resources to access professional learning and/or teaching materials (Mroz, Citation2006; Smith & McKechnie, Citationn.d.; Weadman et al., Citation2020, Citation2022).

While socioeconomic status and type of early learning centre cannot readily be altered, the quality of the instructional support that is provided to children within a centre is one factor that can be changed through access to professional development opportunities for educators. However, these opportunities regularly require educators to take time off the floor and away from their daily duties (Marshall et al., Citation2002) and commonly incur costs, for either the individual educator or the service (e.g. paying to attend a conference or workshop, paying for casual staff to cover the educator’s absence from regular duties).

This study aimed to evaluate child, educator, and environment level outcomes following participation in a novel approach to the delivery of the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! curriculum supplement (Peach & Nicholls, Citation2016). The SLPs and sSLPs were employed by the local university and their services were funded by a government research grant. They attended the childcare services twice weekly to provide embedded, on the floor services and educator coaching, thus removing any potential barriers related to funding and educator time away from regular duties.

Overall, children demonstrated significant gains in alliteration awareness, print knowledge, story retell, and story generation post-intervention. The impact on oral language measures was limited. This is consistent with previous Read It Again research outcomes, which demonstrated more prominent positive impacts on children’s phonological awareness (Albritton et al., Citation2018; Bleses et al., Citation2017; Justice et al., Citation2010; McLeod et al., Citation2019) and print knowledge (Bleses et al., Citation2017; Mashburn et al., Citation2016; Piasta et al., Citation2020) than on language skills such as vocabulary and language expression (Mashburn et al., Citation2016; Piasta et al., Citation2020; Pentimonti et al., Citation2017). This was the first investigation to use the more functional context of language sampling to measure changes in children’s oral language following participation in Read It Again – KindergartenQ! Previous research using standardised assessments to provide distal measures of children’s language outcomes, for example, the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals Preschool—Second Edition (CELF P2; Wiig et al., Citation2004; used by Justice et al., Citation2010) and the Test of Early Preschool Literacy (TOPEL; Lonigan et al., Citation2007; used by Albritton et al., Citation2018; Mashburn et al., Citation2016; Piasta et al., Citation2015) reported mixed results. However, our study demonstrated no significant effect of the intervention on proximal measures of children’s language, including MLU, NDW, moving average NDW, and percentage of utterances with errors. Possible explanations for this include the fact that there were baseline differences between the two groups on NDW, and the direction of change was inconsistent between participants. That is, there was a high degree of variability between participants: some participants improved post-intervention, while others appeared to have declined. There is currently insufficient evidence to determine whether Read It Again – KindergartenQ! may impact on preschool children’s conversational language skills. Also in contrast to previous research, we did not find any significant improvement to children’s rhyming skills, however, this could be attributed to sample size limitations. Earlier research demonstrating positive effects on children’s rhyme awareness have involved considerably larger sample sizes than this study (e.g. Bleses et al., Citation2017; Justice et al., Citation2010).

This is the first study to demonstrate significant improvements to children’s oral narrative skills. Neither Mashburn and colleagues (Citation2016) nor Piasta and colleagues (Citation2020) found any appreciably positive outcomes for children’s narrative skills, and most other studies have not specifically measured children’s narrative (e.g. Bleses et al., Citation2017; Hilbert & Eis, Citation2014; Justice & Ezell, Citation2002; Justice et al., Citation2010). One hypothesis for our findings may be the novel inclusion of the interprofessional lesson delivery and/or the regular coaching provided to educators across all learning objectives of the Read It Again – KindergartenQ! program (in contrast to Albritton et al., Citation2018, where coaching focused on phonological awareness only). However, a direct comparison between different modes of delivery of Read It Again, with and without coaching components, would need to be experimentally evaluated to confirm or exclude coaching as a contributing factor. Further replication of these effects is necessary, however, given the positive predictive value that strong oral narrative skills have on children’s later literacy success (e.g. Kim et al., Citation2015), these findings support the inclusion of explicit narrative instruction in preschool curricula, the provision of additional content knowledge and training in narrative instruction for educators, and collaborative practice between educators and SLPs.

Whilst we did not find any appreciable differences in implementation fidelity between the two participating educators, several of the oral language and emergent literacy outcomes for children demonstrated an educator effect. That is, children under ECE1 demonstrated greater improvements than children under ECE2 on several of our measures of interest. Our findings also demonstrated clear differences in the extent to which each educator’s communication and literacy instructional practices changed over time. While ECE1 demonstrated significantly increased frequency of use on four out of the five domains of language and literacy instructional practice, ECE2 demonstrated a non-significant increase in frequency of use on only two of the five domains. In addition, ECE1 significantly outperformed ECE2 on three of the five measured domains of instructional practice post-intervention. These findings are consistent with previous research (Mashburn et al., Citation2016), which demonstrated that higher quality language modelling from educators resulted in greater gains for children’s language and early literacy skills. In contrast, children under both educators, irrespective of the number of lessons they received, made gains in absolute performance on word and print awareness tasks. Further exploration of the reasons for the observed differential effect is warranted. One hypothesis is that the level of qualification held by individual educators and, by association, their prior knowledge of children’s oral language and emergent literacy development, influenced the degree of benefit they were able to derive from participating in the program. In our study, ECE1 held tertiary qualifications and ECE2 held vocational qualifications. While it is known that curricula content for oral language and emergent literacy development varies widely for tertiary training courses (Weadman et al., Citation2021), little is known about the content of vocational training courses. Scope therefore exists for SLPs working in academia to collaborate with early childhood education qualification providers to increase the quality and quantity of preservice training in oral language and emergent literacy development. Further clinical implications of these findings suggest that although Read It Again – KindergartenQ! (and all other formats) are fully scripted and designed to be used by early childhood educators, consistent coaching and support from SLPs may be indicated. This is particularly so for more complex/less concrete learning objectives such as phonological and phonemic awareness, vocabulary, and narrative skills.

No significant impact on classroom language and literacy environment was observed in our study, although there were measurable improvements to the oral language environment (which includes extending conversations, building vocabulary, and phonological awareness) that did not reach statistical significance. This is perhaps unsurprising given that Read It Again – KindergartenQ! has no specific focus on two of the three domains of classroom quality that were explored using the ELLCO (Smith et al., Citation2008) tool in this study. Our results were consistent with previous Read It Again research exploring environmental effects (Mashburn et al., Citation2016; Piasta et al., Citation2020).

Limitations

The see one, do one interprofessional model of service delivery, plus a coaching component, was a novel contribution of this paper. In the absence of a control group implementing Read It Again – KindergartenQ! in a more traditional format, we are unable to infer any direct effects of either the interprofessional delivery or the coaching component of our model on our findings. Further research is required in the form of a randomised controlled trial with preregistration.

The use of multiple measurements from the one assessment tool (PIPA; Dodd et al., Citation2000) prevented an overall measure of phonological awareness. This increased the likelihood that individual measures were correlated, further reducing overall statistical power.

Use of multiple sSLPs as the agent of change across the intervention period meant that each student could have brought slightly different teaching methods to the intervention (though intervention fidelity was measured to mitigate this and found to be high overall). Similarly, the use of multiple students during data collection introduced risk of inconsistency in sampling strategies, which may potentially affect children’s performance during language sampling.

The nature of this pragmatic trial, which was conducted on site in the ECEC, may have led to less-than-ideal sampling conditions, for example, ambient noise from other children playing leading to difficulties accurately transcribing language samples. The surrounding distractions may have also impacted the children’s performance on tasks. In addition, some participating children were also attending both ECEC and government preschool; therefore, they were potentially exposed to a preschool program that may have overlapped with the learning objectives of interest of Read It Again – KindergartenQ! Additional factors such as children’s baseline language skills, the home language and literacy environment, and the influence of other educational environments were not controlled for.

The nested nature of the data led to several potential limitations. First, there was an imbalance both within and between educators for the number of children receiving one vs. two lessons per week; 17 children received only one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson while eight children received two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week. For the 17 who only had one lesson per week, seven of them received only an educator-led session, while 10 of them received only an sSLP-led session. Second, for ECE1, six children received one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week and five children received two Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lessons per week. In contrast, for ECE2, 10 children received one Read It Again – KindergartenQ! lesson per week with three children receiving two lessons per week. Once the fixed effects of educator and lessons were applied to the data, statistical power to detect meaningful change was reduced by the smaller sample sizes within each group.

Finally, the availability and training of research personnel meant that we were unable to use blinded post–intervention assessors for the educator and environmental observations. This introduced a potential risk of bias.

Future directions

Future research in this space should consider a larger sample size to counter the statistical impact from the large variability between children and multiple measures being compared from within the same assessment task or tool. Accuracy and consistency of the data collection strategy should be controlled for. Future research should also be aware of the potential for a differential effect depending on children’s baseline language skills, as demonstrated in Justice et al. (Citation2010) where children with higher language skills at the beginning of the program derived greater benefit to their phonological awareness and print knowledge skills than children with lower initial language skills. Further exploration of interprofessional collaborations and interventions should consider more regular and structured measurement of children’s responses to intervention. This would allow facilitators to ensure that concepts and learning objectives have been consolidated before moving on to the next lesson, or to individualise instruction within smaller groups.

Conclusions and clinical implications

Interprofessional collaboration with a coaching component is an effective approach to increasing the frequency of educators’ language and literacy promoting instructional behaviours and can promote the use of novel interventions or curricula. Interprofessional delivery of Read It Again – KindergartenQ!, in particular, achieved growth in children’s print knowledge, first sound awareness, and narrative skills.

Coaching and capacity building with educators should be core business for SLPs, particularly considering current allied health workforce limitations and long waiting times for clients to receive specialist services. If those children at risk for only mild deficits in oral language skills are exposed to rich oral language and early literacy environments, it is feasible to suggest that these children may not end up requiring direct SLP support, thus alleviating some of the strain on wait lists and funding bodies.

However, the practicalities of extending SLPs’ core business into coaching and capacity building, with educators and early childhood education services as the client or service end user, needs to consider the current limitations on the early childhood education sector to fund such professional development opportunities. Alternatively, SLPs would need to seek community grant funding, which is also time consuming and not a sustainable source of funding.

SLPs and their professional associations should continue lobbying state and federal governments to include in their decadal strategies for early childhood education and care reform the provision of funding, to embed SLPs into early education and care environments. These findings suggest that this kind of embedded and ongoing support and capacity building for educators and children can be an effective way to mitigate the risk of developmental vulnerability in preschool aged children.

McKechnie et al_Supplementary materials_R1 clean.docx

Download MS Word (33.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the childcare centre, families, children who participated, childcare educators, sSLPs, and certified SLPs from University of Canberra.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACT Government Community Services. (2022). Australian Early Development Census - Community Services. Retrieved from https://www.communityservices.act.gov.au/ocyfs/children/australian-early-development-census

- Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. MIT Press.

- Albritton, K., Patton Terry, N., & Truscott, S. D. (2018). Examining the effects of performance feedback on preschool teachers’ fidelity of implementation of a small-group phonological awareness intervention. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 34(5), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2018.1456990

- Alonzo, C. N., McIlraith, A. L., Catts, H. W., & Hogan, T. P. (2020). Predicting dyslexia in children with developmental language disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 63(1), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_JSLHR-L-18-0265

- Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority. (2022). Qualifications for centre-based services with children preschool age or under. National Quality Framework. Qualifications for centre-based services with children preschool age or under | ACECQA.

- Australian Government Department of Education. (2021). Australian Early Development Census. Retrieved from https://www.aedc.gov.au/

- Baker, N. D., & Nelson, K. E. (1984). Recasting and related conversational techniques for triggering syntactic advances by young children. First Language, 5(13), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/014272378400501301

- Bayraktar, V. (2018). Investigating print awareness skills of preschool children in terms of child and parent variances. TED EĞİTİM ve BİLİM, 43(196), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.15390/EB.2018.7679

- Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2008). Creating Robust Vocabulary: Frequently asked questions & extended examples. The Guildford Press.

- Bleses, D., Højen, A., Justice, L. M., Dale, P. S., Dybdal, L., Piasta, S. B., Markussen-Brown, J., Clausen, M., & Haghish, E. F. (2017). The effectiveness of a large-scale language and preliteracy intervention: The SPELL randomized controlled trial in Denmark. Child Development, 89(4), e342–e363. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12859

- Brebner, C., Jovanovic, J., Lawless, A., & Young, J. (2016). Early childhood educators’ understanding of early communication: application to their work with young children. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 32(2), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659016630034

- Brown, M. I., Westerveld, M. F., Trembath, D., & Gillon, G. T. (2018). Promoting language and social communication development in babies through an early storybook reading intervention. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(3), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2017.1406988

- Burgess, S. R., Hecht, S. A., & Lonigan, C. J. (2002). Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading‐related abilities: A one‐year longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly, 37(4), 408–426. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.37.4.4

- Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., Logan, J. A., & Konold, T. R. (2013). Emergent literacy profiles among prekindergarten children from low-SES backgrounds: Longitudinal considerations. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(3), 608–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.03.007

- Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Tomblin, J. B., & Zhang, X. (2002). A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in children with language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 45(6), 1142–1157. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2002/093)

- Clay, M. (1979). The early detection of reading difficulties: A diagnostic survey with recovery procedures. Heinemann.

- Cleave, P. L., Becker, S. D., Curran, M. K., Van Horne, A. J. O., & Fey, M. E. (2015). The efficacy of recasts in language intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(2), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0105

- Costanza-Smith, A. (2010). The clinical utility of language samples. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education, 17(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1044/lle17.1.9

- Davis, J. L. (2019). The role of the Early Childhood Special Educator (ECSE) and Speech Language Pathologist (SLP) in supporting children with Speech or Language Impairment (SLI) in Early Childhood Education (Doctoral dissertation. University of Leeds.

- Dickinson, D. K., & Porche, M. V. (2011). Relation between language experiences in preschool classrooms and children’s kindergarten and fourth‐grade language and reading abilities. Child Development, 82(3), 870–886. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01576.x

- Dockrell, J., Lindsay, G., Roulstone, S., & Law, J. (2014). Supporting children with speech, language and communication needs: an overview of the results of the Better Communication Research Programme. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 49(5), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12089

- Dodd, B., Crosbie, S., McIntosh, B., Teitzel, T., & Ozanne, A. (2000). The preschool and primary inventory of phonological awareness (PIPA). Psychological Corporation,

- Dunst, C. J., & Trivette, C. M. (2009). Using research evidence to inform and evaluate early childhood intervention practices. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 29(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121408329227

- Durán, L. K., Gorman, B. K., Kohlmeier, T., & Callard, C. (2016). The feasibility and usability of the read it again dual language and literacy curriculum. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44, 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0729-y

- Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub‐Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T. (2001). Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta‐analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), 250–287. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.36.3.2

- El-Choueifati, McCabe, Munro, Galea, Purcell. (2011). The Interaction, Communication & Literacy Skills Audit. Bankstown Community Resource Group & The University of Sydney.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Fenech, Waniganayake, M., & Fleet, A. (2009). More than a shortage of early childhood teachers: looking beyond the recruitment of university qualified teachers to promote quality early childhood education and care. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 37(2), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660902804022

- Fletcher, K. L., & Reese, E. (2005). Picture book reading with young children: A conceptual framework. Developmental Review, 25(1), 64–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2004.08.009

- Girolametto, L., & Weitzman, E. (2002). Responsiveness of childcare providers in interactions with toddlers and preschoolers. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 33(4), 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2002/022)

- Goldfeld, S., O'Connor, E., O'Connor, M., Sayers, M., Moore, T., Kvalsvig, A., & Brinkman, S. (2016). The role of preschool in promoting children’s healthy development: Evidence from an Australian population cohort. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 35, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.11.001

- Hall, G. E., Dirksen, D. J., & George, A. A. (2006). Measuring implementation in schools: Levels of use. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

- Hammer, C. S., Hoff, E., Uchikoshi, Y., Gillanders, C., Castro, D. C., & Sandilos, L. E. (2014). The language and literacy development of young dual language learners: A critical review. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 715–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.05.008

- Harrison, L. J., McLeod, S., Berthelsen, D., & Walker, S. (2009). Literacy, numeracy, and learning in school-aged children identified as having speech and language impairment in early childhood. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(5), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549500903093749

- Hayes, D. P., & Ahrens, M. (1988). Speaking and writing: Distinct patterns of word choice. Journal of Memory and Language, 27, 572–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(88)90027-7

- Hayes, S. (2008). Nine ducks nine. Candlewick Press.

- Hilbert, D. D., & Eis, S. D. (2014). Early intervention for emergent literacy development in a collaborative community pre-kindergarten. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(2), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-013-0588-3

- Justice, L. M., McGinty, A. S., Cabell, S. Q., Kilday, C. R., Knighton, K., & Huffman, G. (2010). Language and literacy curriculum supplement for preschoolers who are academically at risk: A feasibility study. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2009/08-0058)

- Justice, L. M., & Ezell, H. K. (2001). Word and print awareness in 4-year-old children. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 17(3), 207–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/026565900101700303

- Justice, L. M., & Ezell, H. K. (2002). Use of storybook reading to increase print awareness in at-risk children. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2002/003)

- Justice, L. M., & McGinty, A. S. (2013). Read it again—PreK. A preschool curriculum supplement to promote language and literacy foundations. OH. The Children’s Learning Research Collaborative.

- Justice, L. M., Bowles, R. P., & Skibbe, L. E. (2006). Measuring preschool attainment of print-concept knowledge: A study of typical and at-risk 3-to 5-year-old children using item response theory. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37(3), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2006/024)

- Kim, Y.S. G., Park, C., & Park, Y. (2015). Dimensions of discourse level oral language skills and their relation to reading comprehension and written composition: an exploratory study. Reading and Writing, 28(5), 633–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9542-7

- Law, J., Rush, R., Schoon, I., & Parsons, S. (2009). Modeling developmental language difficulties from school entry into adulthood: Literacy, mental health, and employment outcomes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52(6), 1401–1416. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0142)

- Lervåg, A., Hulme, C., & Melby‐Lervåg, M. (2018). Unpicking the developmental relationship between oral language skills and reading comprehension: It’s simple, but complex. Child Development, 89(5), 1821–1838. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12861

- Liddy, M., Nicholls, K., Peach, J., & Smith, L. (2013). Read it Again – FoundationQ!. ©State of Queensland (represented by the Department of Education, Training and Employment)

- Lonigan, C. J., Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., & Rashotte, C. (2007). Test of preschool early literacy (TOPEL). PRO-ED.

- Marshall, J., Ralph, S., & Palmer, S. (2002). I wasn’t trained to work with them’: mainstream teachers’ attitudes to children with speech and language difficulties. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 6(3), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110110067208