Abstract

Purpose

Within Australia, some families face challenges in accessing paediatric speech-language pathology services. This research sought to investigate the factors that impact access to paediatric speech-language pathology services within Western Australia.

Method

Researchers used constructivist grounded theory to investigate the construct of access, as experienced and perceived by service decision-makers, namely caregivers of children with communication needs and speech-language pathologists who provide communication services. Eleven speech-language pathologists and 16 caregivers took part in 32 semi-structured in-depth interviews. Researchers used layers of coding of interviews transcripts and the constant comparative method to investigate data.

Result

Findings outline the factors that impact access to speech-language pathology services, as organised into the seven categories of the Model of Access to Speech-Language Pathology Services (MASPS). The categories and properties of this model are grounded within experiences and perspectives that participants contributed to the dataset.

Conclusion

MASPS provides a theoretical structure that has been constructed using inductive and abductive reasoning. This model can be used by service designers and decision-makers to reflect upon and improve experiences of service for a range of consumers. MASPS can also be used as a basis for further investigation into aspects of service access.

Introduction

Currently, speech-language pathologists face a challenge around the supply and demand of their services. Speech Pathology Australia (Citation2023) reports that there is an inequitable scarcity of services nationally. While the shift to a more individualised funding model within Australia has reduced the financial impact of accessing allied health services, and raised awareness within the community of these services (Moskos & Isherwood, Citation2019), this shift has also placed greater demand on speech-language pathology as a profession to meet this growing demand while maintaining service quality. The Speech Pathology 2030 (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2016) vision underscores the need for speech-language pathologists to be considerate of the impact of their service delivery methods in order to best work with, and provide support to, consumers who live with communication disabilities (Olswang & Prelock, Citation2015; Shelton et al., Citation2021; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2016).

Access to speech-language pathology services

In Western Australia (WA), there are a range of speech-language pathology service structures that consumers can access across metropolitan, as well as regional and remote, areas. These include private clinic services and publicly funded community services. In WA, private services are typically paid for by consumers, with a variety of subsidies available through either private health insurance or Australia’s Medicare system. Publicly-funded services in WA are those that are fully funded by the government, managed by the budgets of various departments of the state government. Individual organisations may choose to provide clinic-based, in-community, telehealth, or other service delivery models. In WA, there is no large-scale provider for in-school services for children, however, services are provided within schools as community locations depending on each organisation’s service delivery model. The focus of this paper is not to outline the service delivery models or funding avenues that exist in WA, but to explore the factors that impact how consumers access these services.

For children with a speech, language, and communication need (SLCN), parental concern was the strongest predictor of service use (Skeat et al., Citation2014). However, not all families of children who have communication difficulties seek to access speech-language pathology services. For example, a third of families who had concerns about their child’s possible speech sound disorder (SSD) had not sought support from a speech-language pathologist within the study by McAllister et al. (Citation2011). This is particularly concerning as heightened parental anxiety is an indicator for referral to a speech-language pathologist for families concerns about SSD (Morgan et al., Citation2017). The most common reason given by parents for not accessing speech-language pathology was not perceiving services as being needed, despite their level of concern and/or the level of concern expressed by their child’s teacher (McAllister et al., Citation2011; McCormack et al., Citation2012). Only about half of the families of children who had been identified as having a SLCN at 4 years of age had both sought and received professional support by age five (Skeat et al., Citation2014). McAllister et al. (Citation2011) identified that approximately 17% of families of children with SSDs who sought speech-language pathology services were unable to access them, thus highlighting issues around access to speech-language pathology services.

For families who are able to access speech-language pathology services, they may experience barriers related to the maintaining of services over time. For example, both direct and indirect properties of travel were identified as factors that impact service access (McAllister et al., Citation2011; Raatz et al., Citation2021; Verdon et al., Citation2011). Raatz et al. (Citation2021) identified three subthemes of travel in their exploration of metropolitan and non-metropolitan families’ access of pathology outpatient paediatric feeding services. The burden of travel included aspects of organising travel for children who had feeding difficulties, sometimes as part of a complex disability, as well as transport specific issues such as negotiating traffic and parking (Raatz et al., Citation2021). The identified costs of travel included direct as well as indirect costs, such as the time-cost on the caregivers’ occupation, as well as potential loss of income (Raatz et al., Citation2021).

Based on the varying density of services in non-metropolitan areas of New South Wales and Victoria, the distance that families are required to travel to speech-language pathology services is highly variable (Verdon et al., Citation2011). The need for non-metropolitan families to travel greater distances amplified their need to both organise travel, as well as organise associated factors such as care for other children (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2014). Burden from geographical disadvantage for non-metropolitan families was identified by both McAllister et al. (Citation2011) and Raatz et al. (Citation2021).

Barriers to accessing speech-language pathology services

Other researchers have previously explored a range of individual factors that impact accessibility of healthcare services. Glogowska and Campbell (Citation2004) found that caregivers’ awareness of communication needs within their communities played a role in how they responded to identifying communication needs within their own children. Parents who were unaware of the relatively high prevalence of SLCN experienced feelings of anxiety and isolation when they were referred to a speech-language pathology service (Glogowska & Campbell, Citation2004). Conversely, parents who were aware of other children in their community that had been supported by speech-language pathology services felt that therapy would be beneficial, which led to feeling responsible as a parent to act early regarding the identified SLCN. While awareness of the potential benefit of speech-language pathology services is important, both Glogowska and Campbell (Citation2004) and Klatte et al. (Citation2020) discuss the importance of clinicians working with caregivers to build towards therapeutic outcomes. Caregiver engagement over time in speech-language pathology services is supported when caregivers are able to discuss their concerns with clinicians and develop a relationship based on mutual understanding (Glogowska & Campbell, Citation2004; Klatte et al., Citation2020). This occurs both when caregivers are able to share their experiences of monitoring development with clinicians (Glogowska & Campbell, Citation2004), and when caregivers create the conditions for collaborative practice within a therapeutic relationship (Klatte et al., Citation2020).

Within Australia, consumers are impacted by a scarcity of local speech-language pathology (McCormack et al., Citation2012; Shelton et al., Citation2021; Verdon et al., Citation2011), however the way in which consumer are impacted presents differently in different geographic areas. In metropolitan areas, this was typically experienced as long waitlists for services (McAllister et al., Citation2011; McGill et al., Citation2020), or service policies that restricted the hours clinicians could spend with each client, which subsequently lowered the dosage of intervention available to each client (Ruggero et al., Citation2012). In non-metropolitan areas this presented as a restricted number of service options, or a lack of any local speech-language pathology service providers (McCormack et al., Citation2012; McLeod, Citation2006; Raatz et al., Citation2021; Verdon et al., Citation2011). This pattern of the differing impact of a low supply of speech-language pathology services across rural and metropolitan areas was also observed nationally by the senate inquiry into communication disorders (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2014). While the initial solution to a lack of services is for speech-language pathology as a profession to seek to increase supply of its services to the community, this is in itself complicated. Firstly, health services are managed at a state/territory level in Australia, so challenges identified at the Commonwealth level may not be applicable in all health systems. There are current acknowledged differences in service delivery and funding models between Australian states/territories (Shelton et al., Citation2021). Secondly, some areas of speech-language pathology practice are more specialised, and are therefore more scarce or require the support of additional infrastructure, which are often located at hospitals or health centres (Raatz et al., Citation2021). Finally, health professionals are less likely to live within non-metropolitan areas, which may reduce the relative availability of services to non-metropolitan populations (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2014; Li, Citation2017).

Australia is one of the least densely populated nations (Central Intelligence Agency, Citation2022). Given the state-focus of this research, it is worth noting that WA’s residents predominantly live in Greater Perth (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017), which represents a disparity of population between metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. In other Australian research, McAllister et al. (Citation2011) indicates that rurality may not present unique challenges to families accessing services, but rather may magnify the impact of the factors to which families are exposed. Related to this, Graham and Underwood (Citation2012) identified that rural service-users preferred health programs that were designed for their individual communities, rather than a rural version of an existing urban program, raising more complexity in geographically large health districts, such as WA. Given this, it is not clear if population density is a factor of speech-language pathology service access in Australia.

Stakeholders investigated within the literature

Speech Pathology Australia (Citation2016) states that as a profession we aim to provide services within our communities that are flexible and considerate of our consumers’ needs. Given the range of identified barriers to accessing speech-language pathology services, it is important that as health professionals we are able to use the tools at our disposal to reflect upon and plan for the needs of our consumers such that access to services is timely and equitable. However, to date, research that has been used to explore services access within Australia has been focused on a particular geographic region (Dew et al., Citation2013), or a diagnostic/client factor (McAllister et al., Citation2011; McCormack et al., Citation2012; McLeod, Citation2006). Of those that considered communication needs, each focused on clients with SSD (Harrison et al., Citation2017; Jessup et al., Citation2008; McAllister et al., Citation2011; McCormack et al., Citation2012; McLeod, Citation2006).

Within the body of research into factors influencing access to healthcare services, some studies have directly considered the work of clinical and managerial staff (Mesidor et al., Citation2011); others have considered caregivers and clients (Dew et al., Citation2013); however, most have investigated families (Chiri & Erickson Warfield, Citation2012; Kovandžić et al., Citation2012; McAllister et al., Citation2011; Ruggero et al., Citation2012; Scheer et al., Citation2003). While investigation of each of these stakeholders’ perspectives is important, few studies have investigated caregiver and clinician perspectives in an integrated manner (McCormack et al., Citation2012). Conducting research into stakeholders’ perspectives in a segregated manner limits the evidence available for design of efficacious service delivery (Liamputtong, Citation2013; McCormack et al., Citation2012; Vallino-Napoli & Reilly, Citation2004). By only considering the views of stakeholders individually, the ability of researchers to understand the community’s collective need/s is limited (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). More recent research has illustrated that consideration of multiple viewpoints in designing service-delivery models is both valuable and possible (Gallagher et al., Citation2019). As such, to gain a deeper understanding of the factors that impact service access, it is important for researchers to consider the perspectives and experiences of multiple key stakeholders of speech-language pathology services.

Key stakeholders who have participated in extant research are caregivers of children with communication needs, and speech-language pathologists who provide service to these children and their families. In this way, the social construct of “service access” can be understood to be held within the relationship between consumers and service providers. Given the need for speech-language pathologists to be able to design and review service access in a way that is considerate of our varied communities of consumers (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2016), this research sought to investigate the factors that impact access to paediatric speech-language pathology services which seek to address paediatric communication needs within WA.

Service access as a construct

Access is not clearly defined within healthcare literature. Some authors consider access to include service availability (i.e. the freedom to make use of a service), and in doing so differentiate between service access and seeking and/or receiving services (McAllister et al., Citation2011; Wylie et al., Citation2013). Some authors consider access to include service availability and the seeking of services, but not the receiving of services (Mesidor et al., Citation2011; Ruggero et al., Citation2012). Access can also be considered to include the availability of services, as well as the processes of seeking and receiving services (McLeod, Citation2006). As this research sought to broadly identify the factors impacting access to speech-language pathology services, access was used to refer to the broader concept, which includes the freedom to make use of a service, and the processes of seeking, receiving, and maintaining those services (Kovandžić et al., Citation2011; McLeod, Citation2006).

Services is used to refer to the collective assessment, intervention, and clinical management offered by clinicians and their colleagues through organisations as service providers. In this way, services does not refer to broad public health campaigns aimed at the general public. Given the definition of access above, the services that are being discussed are ones that are sought or provided regarding the specific needs of a client, rather than generic services that a client would receive regardless of their specific needs.

Researcher positionality

Prior to commencing this study, the first author faced challenges in clinical practice to supporting their paediatric clients to access services. In seeking to better understand how clients and their families could be supported to access services, discussions with colleagues typically focused on families being “motivated” or “unmotived.” Having been a healthcare consumer as well as a clinician, the first author felt that this binary discussion was insufficient and did not reflect the experience of healthcare access. This research was initially motivated by the desire to better equip speech-language pathologists with an understanding of the factors that impact how families access services. The personal context in connection with this research is explored in more depth in the doctoral thesis of this work (Wells, Citation2022).

Aim

This doctoral research aimed to investigate the factors that impact access to paediatric speech-language pathology services which seek to address paediatric communication needs within WA. The focus of this research is on services that address the needs of children with SLCNs, and so excludes services for an adult population or services focused on areas other than communication.

Method

As the aim of this research was to investigate the components of a broader social construct, constructivist grounded theory (CGT; Charmaz, Citation2012) was selected as an appropriate methodological approach. GCT is a methodological approach in qualitative research that allows in-depth exploration of a social construct in a way that values experiences and viewpoints within and across multiple stakeholder groups (Wells, Citation2022). This research had approval from Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC; HRE2018-0116).

Participants

Participants belonged to two broad stakeholder categories: caregivers of children who have a SLCN and speech-language pathologists who provide services to this population. These participant groups were selected as they are the key decision-makers within paediatric speech-language pathology services. In this work, caregivers was used as a broad label to include biological parents, step-parent, grand-carers, and a range of other family relationships. The researchers did not place a finite restriction on this term, but allowed participants to self-select as caregivers of children who have a SLCN. Following a CGT methodology, the authors were able to recruit additional participant groups if identified through analysis (Charmaz, Citation2012; Skeat & Perry, Citation2008); however, this did not arise within this project. Thirty-two semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted by the first author with 27 participants (n = 16 caregivers; n = 11 speech-language pathologists). All participants took part in an initial interview, with five participants each taking part in a follow-up interview. All participants were accessing or providing services within WA during the period of data collection.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited via purposive and snowball sampling. Information about the research was distributed via posters, flyers, and social media posts. Recruitment materials were distributed within researchers’ professional networks to private and non-government organisations within WA who provide speech-language pathology services. All recruitment materials were approved by The University’s HREC prior to use.

Data collection

The first author conducted all interviews as part of a PhD enrolment, with interview training provided by the other authors. Interviews were conducted at a mutually convenient time and location. Semi-structured interviews were 45–90 minutes in length and followed an interview guide (see Appendix), which was revised throughout the iterative process of data collection and analysis consistent with CGT methods (Carroll et al., Citation2022; Charmaz, Citation2012; Skeat & Perry, Citation2008). Questions were initially broad and sought to explore the factors that impacted how speech-language pathology services were accessed. Throughout the course of data collection, the interview guide was updated to align with exploration of the categories as they were constructed, as described below. Prior to data collection, participants were given a summary of the research via the participant information sheet, and through conversation with the first author at the time of their interview. All participants were made aware that the first author was working actively as a speech-language pathologist during the course of the research. Where appropriate and relevant to the interview, the first author provided context for their understanding of the healthcare system based on their professional work. Some, but not all, of the speech-language pathologists who took part in this research were known to the first author and/or co-authors. Strategies to appreciate the impact of bias were implemented throughout data collection and analysis, which are outlined in the doctoral thesis of this work (Wells, Citation2022).

Analysis

Data analysis followed a CGT approach as outlined by Tweed and Charmaz (Citation2012). Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and sent to participants for checking before being coded. Open coding was used within this research, consistent with a constructivist philosophical paradigm (Wells, Citation2022). The first author applied descriptive line-by-line and incident-with-incident codes. Occasional word-by-word codes were used as it was deemed necessary by the first author in collaboration with other authors, however this was not typical practice. Constant comparative analysis was employed as a method for the researchers to be able to generate new conceptual understandings of codes through routine consideration of the relatedness of pieces of data (Carroll et al., Citation2022). This process led informed categorisation of data, the ongoing shaping of the interview guide, as well as model building. Categorisation and labelling of initial codes using focused coding by the first author helped to generate proto-categories and properties in the initial drafts of the grounded theory. Ongoing data analysis informed the ways in which the semi-structured interview guide was updated: as areas of interest arose, lines of questioning were opened or expanded through an aspect of grounded theory known as theoretical sampling; as categories were more clearly and fully understood, lines of question were reduced, refined, or closed through an aspect of grounded theory known as theoretical saturation (Charmaz, Citation2012).

Theoretical codes were written to explain the relationships between proto-categories and categories within the model as it was being built. The first author engaged in an iterative process of model building, which included drafting versions of the model based on their understanding of the data. This understanding develops over time in a grounded theory, due to the iterative process of data collection and analysis. All authors discussed and refined the model as it was being built. Focused and theoretical coding of transcripts during the model-building phase facilitated concepts and properties of categories, and category relationships, to be more clearly defined and/or challenged. As the process of model building continued, the understanding of the categories as well as their properties and relationships to one another each became theoretically saturated.

Memos were used by the researchers to document and reflect on the dataset as it developed and was analysed. Audio or written memos were created following each interview and at research milestones, as well as ad hoc throughout the course of the research project. Memos were stored as part of a reflexive journal.

Result

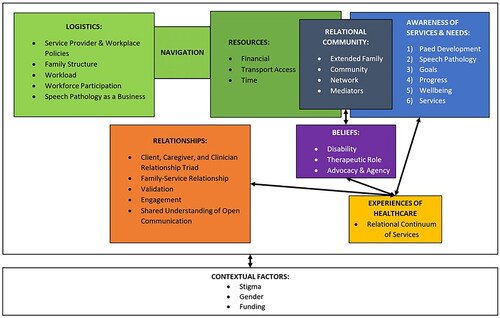

The Model of Access to Speech-Language Pathology Services (MASPS; see ) outlines the factors that impact service access as identified within this research, and visualises the relationship between them. This model consists of seven categories and a list of three contextualising factors that reflect the context in which the project’s data was grounded. The seven categories are: Resources, Logistics, Awareness, Relational Community, Experiences of Healthcare, Relationships, and Beliefs. Definitions of the seven core categories have been provided in . Vignettes and descriptions have been included as examples within this paper; however, it is important that speech-language pathologists reflect on how their service provision is experienced by their community of consumers and not focus only on the presented examples. In this paper, focus has been placed on defining each of the core categories. For further information about each property, readers should refer to the doctoral thesis associated with this research (Wells, Citation2022).

Table 1. Definitions of the core categories of the Model of Access to Speech-Language Pathology Services (MASPS).

Resources

Participants identified that accessing services required families to draw upon a range of resources. In some respect, Resources as a category refers to anything that families can use to support their access of services, however three main properties of resources (financial, transport, and time) were identified through data analysis. Within this category, having additional resources was linked to greater ease of access to services, though it should be noted that all caregivers described restrictions with at least one property of Resources, even those who had self-reported as having access to greater than average resources. Resources were primarily discussed in relation to direct use for access, such as paying for a therapy session. However, participants also discussed indirect access, such as using resources to arrange care for a client’s siblings in association with therapy sessions.

Logistics

Participants shared a variety of factors that impacted the way in which they planned for services or used their resources. Properties within Logistics (service provider and workplace policies, family structure, workload, workforce participation, speech pathology as a business) relate to the flexibility of the service provider and the family to adapt to one another in a suitable way. Properties within Logistics are not influenced by quantity or presence/absence, but more so by suitability with the service that was being accessed. For example, a family may have only have a few options for childcare for the siblings of the child for whom they are accessing services. As such, the caregiver may prefer to access services on a day when they are not in paid employment, and siblings are at school or in arranged care. However, in order for this to happen, the organisation and speech-language pathologist that they are attempting to access would also need to be available. If there is a mismatch with the family and organisation logistics, the caregiver may need to reduce their workforce participation, and/or find a new childcare or service provider. When there is a mismatch, different caregivers have reported responding differently depending on the resources available to them. The categories of Resources and Logistics are connected by the subcategory of Navigation.

Navigation

Navigation reflects the way that families use the resources that are available to them in a way that is considerate of the logistics that play a role in their service access. For example, families who have access to greater financial resources but limited access to time may choose to pay for home-based services. Conversely, families with access to fewer financial resources may travel to clinic-based services and so experience a great time-cost of service access. Most participants indicated that decisions about the way they navigated service access were influenced by an understanding of their own context, as well as collaborative discussions between caregivers and clinicians. Navigation also reflects the notion that, in general, caregivers perceived clinicians as holding knowledge about the broader health system. In this way, Navigation also represents the way in which clinicians can work with caregivers to identify the most suitable match between the resources available to them, and the logistics that they must consider.

Awareness

Within the dataset, several types of awareness related to service access were identified. Caregivers’ awareness related to speech-language pathology service access was built through their interaction with other people in their Relational Community (below), and through their own Experiences of Healthcare (below). Definitions of properties within the Awareness category of MASPS have mostly been written drawing on experiences of families as described by caregiver participants. Readers should note that this has been done for the sake of brevity, and that speech-language pathologists play a role in raising awareness at all levels with clients, their families, and within communities. Different types of awareness were identified that built upon one another throughout a family’s interaction with speech-language pathology as a profession. These different types of Awareness were identified as being ordinal: (1) awareness of development and milestones, (2) awareness of the speech-language pathology profession and scope of practice, (3) awareness of communication goals, (4) awareness of progress within therapy, (5) awareness of impact of therapy on wellbeing and vice versa, and (6) awareness of speech-language pathology services.

Many caregiver participants shared that their understanding of the existence and breadth of the scope of speech-language pathology developed through their interactions with the profession. In line with this, participants routinely raised the idea that there is low awareness of speech-language pathology as a profession within WA, and that our profession has a role to play in building awareness within the community.

Relational Community

The subcategory of Relational Community connects the categories of Awareness and Resources to illustrate that a family can use members of their community in two ways: as an indirect resource to support service access and to inform their awareness of service access.

Relational community members (extended family, community, and professional networks of a family) may be called upon by a family to support their access by increasing availability of resources, such as the provision of time or transport for the siblings of the child for whom services are being sought. Participants also identified that their Relational Community helped to develop their awareness within the six properties of Awareness outlined above. In most cases participants described how they found this communal knowledge of SLCN and speech-language pathology to be helpful. However, this research identified that Awareness can also function in a way that perpetuates myths about speech pathology services.

Experiences of Healthcare

Beyond the category of Awareness, each caregiver’s and client’s own previous experiences of healthcare informed their perceptions of speech-language pathology as a profession, and contributed to their understanding of how they would interact with a speech-language pathologist. If families had positive experience with the profession first, followed by less positive or negative experiences, these negative perceptions were framed within their overall view of the profession. Conversely, for families who had negative experiences of speech-language pathology first, this informed a negative view of the profession, which required a greater amount of positive influence/experiences to shift.

Experience of Healthcare includes the way in which caregivers and clients understand the schema of speech-language pathology services, and the way that speech-language pathologists support understanding of this schema. Some children, who had only attended nursing and general practitioner appointments, were reported to generally behave differently to those children who had previously attended other allied health services. The property relational continuum of healthcare reflects the concept that each health profession exists on a continuum between the discreet points of relational and transactional, and that the way in which any consumer perceives individual professions is informed by their own healthcare needs and previous experiences with healthcare.

Relationships

The properties of the Relationships category (relationship triad, family-service relationship, validation, engagement, and shared understanding of open communication) outline the aspects of the relationship between caregivers, clients, and speech-language pathologists throughout the period of service access. These relationships are influenced by healthcare experiences and perceptions, but also develop over time. The relationship triad outlines that within a therapeutic relationship for paediatric services, there are three stakeholders: the speech-language pathologist, the client, and their caregiver/s. These stakeholders each have a relationship with one another, and observe the therapeutic relationship of which they are not a direct part. This is to say, for example, that the caregiver’s relationship with the clinician was impacted by their observation of the relationship between the clinician and the client. Broadly, relationships were stronger where there was a greater amount of validation of caregivers’ concerns, clinicians and caregivers openly discussed their communication approach, and, where the caregiver and clinician perceived one another to engage well with the client.

It is important to note that participants report a general shift in the roles within the Relationship triad over time, however participants talked about this shift with clients as they became more “mature” as opposed to becoming “older.”

Beliefs

The beliefs that caregivers and clinicians hold in relation to disability, therapeutic roles, as well as advocacy and agency impact on service access. Where a clinician’s beliefs were well aligned with a caregiver’s beliefs, these factors fostered an ongoing relationship that was supportive of service access. However, where there was a misalignment, this contributed to challenges in accessing services in an ongoing way. Experiences of alignment or misalignment contribute to a caregiver’s experiences of healthcare and perception of speech-language pathology as a profession.

Contextual factors

Stigma, gender, and funding were identified as contextual factors. These are factors that were routinely identified in relationship with properties and categories throughout MASPS. Given their connectedness, these factors could not be explored extensively here, and the reader should note that there is detailed nuance to each of these factors (Wells, Citation2022). While less common in the dataset, caregivers experienced stigma as rooted in feeling as if they were not able to provide “enough” for their child. Participants did not identify speech-language pathology service access as gendered, but that service access is related to caregiving and that the role of primary caregiver within families in WA was typically held by women. As such, speech-language pathology service access exists within a gendered context in WA. Funding was discussed routinely, and is directly evident within the property of financial resources. For caregivers, their child being the recipient of funding for services was a demonstration of validating the need for services from the funding body. Beyond this, the lack of focus from funding schemes on the secondary and indirect financial costs, as well as the lack of recognition of long-term loss of income associated with supporting a child who has an SLCN, was challenging for participants.

Discussion

This research sought to investigate the factors that impact access to paediatric speech-language pathology services which seek to address paediatric communication needs within WA. As part of the CGT methodology, a model was constructed that represents the interconnection of these factors, seen as properties within broader categories (see ). In conducting this work an extant model has been established, which demonstrates an initial understanding of the factors that impact service access and their relationship to one another. Further work is needed to explore, refine, and corroborate the initial understanding that is represented by the presentation of MASPS.

Speech-language pathologists can use MASPS to reflect on the way in which their service provision is structured in consideration of the identified factors. This reflection may be done at a service level or in consideration of individual families who have been identified as struggling with accessing services. In this way, MASPS can be seen to sit within an implementation science framework (Olswang & Prelock, Citation2015; Roddam & Skeat, Citation2021) by supporting speech-language pathologists to consider the interaction of clinical evidence-based practice recommendations and their interaction with real clients who are impacted by factors of service access. Other understandings of healthcare, which are less tailored to speech-language pathology, are currently being used in this way for broad consideration of access to early intervention allied health services (Sapiets et al., Citation2021) and access to transactional healthcare services (Tanahashi, Citation1978), such as vaccination and radiological infrastructure. While some speech-language pathologists and service providers may already be considering some or most of the factors identified above, MASPS as a model presents a structure for speech-language pathologists to consider these factors systematically. Rather than delivering services that are designed to be accessed by consumers regardless of their individual contexts, considerate healthcare encourages service providers to design services in light of the needs of their specific community of consumers (McDermott, Citation2019). The presentation of MASPS creates a basis for the implementation of a system of considerate healthcare with the intent that families are able to access speech-language pathology services in a timely and informed manner. In this way, this work can be considered to contribute to addressing the needs of Speech Pathology Australia’s (Citation2016) long-term planning for the profession.

The work that led to the creation of MASPS identified that speech-language pathologists have a role to play in building the awareness of the community around the capacity of their profession. Currently, consumers of speech-language pathology services rely on schema knowledge from their experiences of other healthcare professionals to anticipate how they will interact with speech-language pathologists. As identified within the Experiences of Healthcare category, caregivers’ and clients’ schema understanding also informed the type of services that were perceived to be provided by speech-language pathologists. Previous research has considered that different healthcare services can be categorised into relational or transactional categories (Porter et al., Citation2013; Salisbury, Citation2020). Relational healthcare is based on an ongoing therapeutic relationship with the healthcare professional, while transactional healthcare follows a medical model and is focused on the delivery of the care (i.e. the transaction). Analysis of coding of this dataset identified that caregivers experienced allied health, medical, and non-medical healthcare services as having elements that were transactional and elements that were relational. Rather than viewing speech-language pathology as a relational service, as clinician participants did within this research, caregiver participant’s experience of speech-language pathology was as a highly relational health service with transactional components. By further interrogating this point, a deeper understanding of the aspects that are valued by consumers may be gained. As Australia shifts more towards individualised funding models, such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (National Disability Insurance Agency, Citation2020), there is a growing need for speech-language pathologists to clearly understand and be able to interrogate the suitability of their services within their community. Work by Wylie et al. (Citation2013) has previously identified the need for services to be suitable to a community, rather than duplicated across communities without consideration. With these concepts in mind, MASPS provides a framework of identified factors through which service providers and designers can consider appropriate design or adaptation of an existing service.

Recommendations for practice

As speech-language pathologists move towards the Speech Pathology 2030 vision (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2016), it is important that they are able to consider the factors that impact how consumers access their services (Olswang & Prelock, Citation2015; Roddam & Skeat, Citation2021). MASPS provides an extant model grounded in qualitative data that speech-language pathologists can use to systematically consider their service provision to their community of consumers, using the identified factors to structure this reflection. Additionally, using MASPS to consider client factors within the design of evidence-based clinical services provides researchers and service designers with a framework towards implementation science (Olswang & Prelock, Citation2015; Roddam & Skeat, Citation2021). Different service providers will identify different adaptations that may be needed to meet the needs of services within their own communities. However, within the dataset there were some consistent recommendations for speech-language pathology practice, which are outlined below.

Financial costs directly associated with sessions (fee-for-service) were discussed as the primary cause for service access difficulties; however, this research identifies that families’ access of speech-language pathology services is multifactorial and that even the financial aspect of services is more nuanced. Service providers should be conscious that the financial cost to families of accessing services goes beyond the service fee, and includes all associated direct, indirect, and secondary costs (McAllister et al., Citation2011; Raatz et al., Citation2021). Speech-language pathologists should note the impact of secondary and indirect costs to families, even when their direct service provision is perceived as “free” or “low cost.”

Accessing services also had a cost impact on paid and unpaid occupations of caregivers, which in turn indirectly impacted service access. Moving forward it is important for speech-language pathologists to be directly considerate of the impact of accessing services on caregivers’ ability to participate in the workforce, and to value caregivers’ unpaid labour related to their therapeutic and advocacy roles (Glogowska & Campbell, Citation2004; Raatz et al., Citation2021). The gendered element of this impact also raises the idea that speech-pathologists should further investigate and reconsider the role that we play in upholding gendered expectations around unpaid care.

Speech-language pathologists should be aware that caregivers typically expect clinicians to be able to support the setting of goals that are clinically relevant based on the concerns they hold in relation to their child/ren’s participation. Klatte et al. (Citation2020) and Glogowska and Campbell (Citation2004) both underscore the importance of clinicians working with caregivers to establish therapeutic outcomes. Caregivers also indicated that they relied on clinicians to support their awareness of speech-language pathology and related funding, more than clinician participants were aware.

Speech-language pathologists should be aware that interactions and relationships with families inform perceptions of their services specifically. But when a family has had few interactions with speech-language pathology as a profession, these perceptions were generalised across our profession. This underscores the need for speech-language pathologists to ensure they are acting in a professional and ethical manner in all interactions with clients and their families. At a whole profession level, participants in both groups suggested that awareness campaigns be designed to raise community awareness of the speech-language pathology profession and of communication needs.

Limitations

Two key limitations were identified within this research. Firstly, all caregiver participants had at some point been successful in accessing services for their child/ren. The intent of this research was to explore the experiences and perspectives of accessing speech-language pathology services, but there may be unique contributions that could be made by families who have not yet been able to access services. Secondly, more recent research has identified the merit in including the client voice (Lyons et al., Citation2022). This was considered while the research was being conducted but was not identified as an aspect of theoretical sampling (Charmaz, Citation2012; Wells, Citation2022). Had the project commenced later, client voices may have been included.

Further directions

It is the responsibility of speech-language pathologists to apply frameworks of evidence-based practice to investigate service access to our profession, just as we do for clinical services (John et al., Citation2023). It will be important for future research to seek further understanding of individual and/or clusters of properties of MASPS through work that focuses on testing and applying MASPS as a model. Alternatively, the properties of MASPS can be refined through testing the model for fit against other populations. Given that few of the factors identified within MASPS are specific to speech-language pathology practice, MASPS is currently being used as a framework to investigate the factors that impact service access for families accessing occupational therapy services.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of an Australian Government Research Training Program stipend scholarship in supporting this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017). ABS Maps. http://stat.abs.gov.au/itt/r.jsp?ABSMaps

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Carroll, C., Harding, D., & Wells, R. P. (2022). Constant Comparative Analysis. In R. Lyons, L. McAllister, C. Carroll, D. Hersh, & J. Skeat (Eds.), Diving deep into qualitative data analysis in communication disorders research. (pp. 79–100). J&R Press.

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2022). World. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/world/

- Charmaz, K. (2012). Constructing grounded theory. (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Chiri, G., & Erickson Warfield, M. (2012). Unmet need and problems accessing core health care services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(5), 1081–1091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0833-6

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2014). Senate Community Affairs References Committee: Prevalence of different types of speech, language and communication disorders and speech pathology services in Australia. Commonwealth of Australia Canberra.

- Dew, A., Bulkeley, K., Veitch, C., Bundy, A., Gallego, G., Lincoln, M., Brentnall, J., & Griffiths, S. (2013). Addressing the barriers to accessing therapy services in rural and remote areas. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(18), 1564–1570. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.720346

- Gallagher, A. L., Murphy, C., Conway, P. F., & Perry, A. (2019). Engaging multiple stakeholders to improve speech and language therapy services in schools: an appreciative inquiry-based study. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 226. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4051-z

- Glogowska, M., & Campbell, R. (2004). Parental views of surveillance for early speech and language difficulties. Children & Society, 18(4), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/chi.806

- Graham, K., & Underwood, K. (2012). The reality of rurality: Rural parents’ experiences of early years services. Health & Place, 18(6), 1231–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.09.006

- Harrison, L. J., McLeod, S., McAllister, L., & McCormack, J. (2017). Speech sound disorders in preschool children: correspondence between clinical diagnosis and teacher and parent report. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 22(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2017.1289964

- Jessup, B., Ward, E., Cahill, L., & Keating, D. (2008). Prevalence of speech and/or language impairment in preparatory students in northern Tasmania. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 10(5), 364–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549500701871171

- John, A., Potapova, I., Escobedo, A., Combiths, P., Barlow, J., & Pruitt-Lord, S. (2023). Using evidence-based practice in the transition to telepractice: Case study of a complexity-based speech sound intervention. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 8(4), 799–811. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_PERSP-22-00197

- Klatte, I. S., Lyons, R., Davies, K., Harding, S., Marshall, J., McKean, C., & Roulstone, S. (2020). Collaboration between parents and SLTs produces optimal outcomes for children attending speech and language therapy: Gathering the evidence. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(4), 618–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12538

- Kovandžić, M., Chew-Graham, C., Reeve, J., Edwards, S., Peters, S., Edge, D., Aseem, S., Gask, L., & Dowrick, C. (2011). Access to primary mental health care for hard-to-reach groups: From ‘silent suffering’ to ‘making it work. Social Science & Medicine, 72(5), 763–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.027

- Kovandžić, M., Funnell, E., Hammond, J., Ahmed, A., Edwards, S., Clarke, P., Hibbert, D., Bristow, K., & Dowrick, C. (2012). The space of access to primary mental health care: A qualitative case study. Health & Place, 18(3), 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.01.011

- Li, J. L. (2017). Cultural barriers lead to inequitable healthcare access for aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders. Chinese Nursing Research, 4(4), 207–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnre.2017.10.009

- Liamputtong, P. (2013). Qualitative research methods. (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Lyons, R., Carroll, C., Gallagher, A., Merrick, R., & Tancredi, H. (2022). Understanding the perspectives of children and young people with speech, language and communication needs: How qualitative research can inform practice. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(5), 547–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2038669

- McAllister, L., McCormack, J., McLeod, S., & Harrison, L. J. (2011). Expectations and experiences of accessing and participating in services for childhood speech impairment. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(3), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.535565

- McCormack, J., McAllister, L., McLeod, S., & Harrison, L. J. (2012). Knowing, having, doing: The battles of childhood speech impairment. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 28(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659011417313

- McDermott, D. (2019). Big Sister” Wisdom: How might non-Indigenous speech-language pathologists genuinely, and effectively, engage with Indigenous Australia? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(3), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2019.1617896

- McGill, N., Crowe, K., & McLeod, S. (2020). Many wasted months”: Stakeholders’ perspectives about waiting for speech-language pathology services. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22(3), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2020.1747541

- McLeod, S. (2006). An holistic view of a child with unintelligible speech: Insights from the ICF and ICF-CY. Advances in Speech Language Pathology, 8(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14417040600824944

- Mesidor, M., Gidugu, V., Rogers, E. S., Kash-MacDonald, V. M., & Boardman, J. B. (2011). A qualitative study: Barriers and facilitators to health care access for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 34(4), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.2975/34.4.2011.285.294

- Morgan, A., Ttofari Eecen, K., Pezic, A., Brommeyer, K., Mei, C., Eadie, P., Reilly, S., & Dodd, B. (2017). Who to refer for speech therapy at 4 years of age versus who to “Watch and Wait”? The Journal of Pediatrics, 185, 200–204.e201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.02.059

- Moskos, M., & Isherwood, L. (2019). Individualised funding and its implications for the skills and competencies required by disability support workers in Australia. Labour and Industry, 29(1), 34–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2018.1534523

- National Disability Insurance Agency. (2020). What is the NDIS? Retrieved 11/3/2020 from https://www.ndis.gov.au/understanding/what-ndis

- Olswang, L. B., & Prelock, P. A. (2015). Bridging the gap between research and practice: implementation science. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 58(6), S1818–S1826. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_JSLHR-L-14-0305

- Porter, A., Mays, N., Shaw, S. E., Rosen, R., & Smith, J. (2013). Commissioning healthcare for people with long term conditions: The persistence of relational contracting in England’s NHS quasi-market. BMC Health Services Research, 13(S1), S2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-S1-S2

- Raatz, M., Ward, E. C., Marshall, J., Afoakwah, C., & Byrnes, J. (2021). It Takes a Whole Day, Even Though It’s a One-Hour Appointment!” Factors impacting access to pediatric feeding services. Dysphagia, 36(3), 419–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-020-10152-9

- Roddam, H., & Skeat, J. (2021). How could implementation science shape the future of SLPs’ professional practice? Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 23(2), 54–58. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=cul&AN=152735083&site=ehost-live&custid=s8423239 https://doi.org/10.1080/22087168.2021.12370315

- Ruggero, L., McCabe, P., Ballard, K. J., & Munro, N. (2012). Paediatric speech-language pathology service delivery: An exploratory survey of Australian parents. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(4), 338–350. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.650213

- Salisbury, H. (2020). Helen Salisbury: Is transactional care enough? BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 368, m226. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m226

- Sapiets, S. J., Totsika, V., & Hastings, R. P. (2021). Factors influencing access to early intervention for families of children with developmental disabilities: A narrative review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 34(3), 695–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12852

- Scheer, J., Kroll, T., Neri, M. T., & Beatty, P. (2003). Access barriers for persons with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 13(4), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/104420730301300404

- Shelton, N., Munro, N., Keep, M., Starling, J., & Tieu, L. (2021). Clinical practices of speech-language pathologists working with 12- to 16-year olds in Australia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(4), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2020.1820576

- Skeat, J., & Perry, A. (2008). Grounded theory as a method for research in speech and language therapy. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 43(2), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820701437245

- Skeat, J., Wake, M., Ukoumunne, O. C., Eadie, P., Bretherton, L., & Reilly, S. (2014). Who gets help for pre-school communication problems? Data from a prospective community study. Child: care, Health and Development, 40(2), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12032

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2016). Speech pathology 2030: Making futures happen. Speech Pathology Australia.

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2023). Speech pathology workforce analysis: Preparing for our future. Speech Pathology Australia.

- Tanahashi, T. (1978). Health service coverage and its evaluation. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 56(2), 295–303. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/96953 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2395571/

- Tweed, A., & Charmaz, K. (2012). Grounded theory methods for mental health practitioners. In D. Harper & A. R. Thompson (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: a guide for students and practitioners. John Wiley & Sons. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781119973249.ch10 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119973249.ch10

- Vallino-Napoli, L. D., & Reilly, S. (2004). Evidence-based health care: a survey of speech pathology practice. Advances in Speech Language Pathology, 6(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/14417040410001708530

- Verdon, S., Wilson, L., Smith-Tamaray, M., & McAllister, L. (2011). An investigation of equity of rural speech-language pathology services for children: A geographic perspective. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.573865

- Wells, R. P. (2022). Factors influencing access to paediatric speech pathology services in Western Australia [Doctoral thesis]. Curtin University]. Curtin University espace. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11937/89249

- Wylie, K., McAllister, L., Davidson, B., & Marshall, J. (2013). Changing practice: Implications of the World Report on Disability for responding to communication disability in under-served populations. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2012.745164