ABSTRACT

Understanding emotions and moral intentions of other people is integral to being human. Humanities scholars have long recognized the complex and ambiguous nature of emotions and morality. People are rarely ‘just’ happy, or sad. Neither are they ‘just’ good or bad people. Despite this, most knowledge about the psychological and neural basis of emotions and moral understanding comes from experiments investigating unidimensional and non-ambiguous emotions and morality. The goal of this paper is twofold. First I want to point out why mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality are a promising research topic for cognitive neuroscientists. Observing or experiencing mixed or ambiguous emotions and morality tends to have a strong impact on humans. This impact is clearly visible in narratives and fiction, and I will argue that narratives make an excellent stimulus to study the effects of emotional and moral ambiguity. Second, I will sketch a model to help guide research in this promising corner of human cognition.

Introduction

In a beautifully written, and moving piece in The Atlantic, prominent neuroscientist David Linden describes what being terminally ill with cancer has taught him about the human mind.

Linden writes:

I may be dying, but I’m still a science nerd, and so I think about what preparing for death has taught me about the human mind. The first thing, which is obvious to most people but had to be brought home forcefully for me, is that it is possible, even easy, to occupy two seemingly contradictory mental states at the same time. I’m simultaneously furious at my terminal cancer and deeply grateful for all that life has given me. This runs counter to an old idea in neuroscience that we occupy one mental state at a time: We are either curious or fearful – we either “fight or flee” or “rest and digest” based on some overall modulation of the nervous system. But our human brains are more nuanced than that, and so we can easily inhabit multiple complex, even contradictory, cognitive and emotional states. (Linden, Citation2021)

That the human mind can occupy several, sometimes contradictory, mental states at the same time, lies at the heart of this paper. Linden describes being furious and grateful at the same time. This is known as a mixed emotion. Mixed emotions are known to all of us – although perhaps not in a way as dramatic as Linden describes. Sometimes our emotions are not mixed, but ambiguous, for instance, when we feel emotional, but find it difficult to put the content of our emotions into words. Some have argued this feeling constitutes the separate category of being moved (Menninghaus et al., Citation2015; Zickfeld et al., Citation2018).

There is a diverse literature that suggests that mixed or ambiguous emotions have a powerful impact on the human mind, perhaps even more powerful than ‘straightforward,’ unidimensional emotions. This literature is conceptual (e.g., in philosophy or literary studies), as well as empirical (e.g., work in media psychology). With considerable exceptions, cognitive neuroscience has not yet fully taken advantage of mixed or ambiguous emotions to enrich our understanding of human cognition. Here I think Linden is right when he writes that neuroscience has been influenced by the idea that mental states come and go one at a time. This is implicit in the study of human emotions: as scientists we understand quite a lot about the brain basis of understanding or experiencing unidimensional emotions like being happy or sad. Exactly how prominent mixed emotions are, is still a matter of debate in the psychological literature (Russell, Citation2017), but that they exist is clear (Berrios et al., Citation2015).

When considering mixed or ambiguous emotions, it is pertinent to also discuss mixed or ambiguous morality. Just like people are not ‘just’ happy or sad, they are rarely ‘just’ completely morally good or bad people. Rather they are mixed or ambiguous in moral terms, exhibiting behavior with a mixture of moral values. For instance, a person may be a caring housefather, caring for his family with good intentions, while at the same time swindling elderly people in online scams. Such a person would simultaneously exhibit morally good (caring) and morally repulsive (swindling the elderly) virtues. Morality and emotions go hand in hand in such cases, and that is one of the reasons for discussing them together in this paper. Another reason is that both emotions and morality are key drivers of behavior and mental activity which both require some form of deliberate or preconscious reflection. This does not mean that the link between the two is theoretically very strong or motivated by a large body of work. A final reason to discuss both emotion and morality is that they have traditionally been studied in separate research fields, although combining them seems a promising direction of research.

In philosophy and in literary sciences the power of mixed morality has been long recognized (Nussbaum, Citation2003; Goldie, Citation2012; Hogan, Citation2011; Keen, Citation2007; Mar & Oatley, Citation2008; Salgaro et al., Citation2021). Literary scholars have argued that morally ambiguous characters are particularly persuasive, serving as a kick starter of moral reflection in the reader (Cave, Citation2016; Hakemulder, Citation2000). By being confronted with characters that act in a morally ambiguous manner, readers have the opportunity to reflect on the character’s moral values, and subsequently, be confronted with their own moral beliefs. There are plenty examples of such morally ambiguous characters in modern as well as classic literature. One archetypical example is Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (readers who are not familiar with Wuthering Heights may nonetheless recognize the name Heathcliff from the Kate Bush song named after this classical work of fiction). Heathcliff is both villain and hero, a prototypical complex and tormented character. This mixture and ambiguity makes him the subject of fascination ever since the appearance of the novel in 1847. More contemporary examples include true crime series about individuals who act in a seemingly morally good way, but turn out to betray others to their own benefit.

In this paper I want to make the case for mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality as a promising yet understudied phenomenon in cognitive neuroscience. Studying the neurocognitive workings of ambiguity in emotions and morality will bring our science closer to understanding how emotions and morality occur in the real world. The second goal of the paper is to introduce a working model–the mixed and amiguous emotions and morality (MA-EM) model–of how the neurocognitive study of ambiguous and mixed emotions and morality can be materialized.

1.1 Mixed emotions

Mixed emotions are not unidimensionally interpretable (Berrios et al., Citation2015; Das et al., Citation2017; Hunter et al., Citation2010; Larsen & McGraw, Citation2014, Citation2014; Maksimainen et al., Citation2019). The most prominently studied example is when people experience being happy and sad at the same time. Larsen and colleagues, for instance, asked college students who had just moved into their dormitory to describe their emotional state. The finding is that students were both more happy and more sad as compared to how they felt on another day before moving (Larsen et al., Citation2001). Although feeling happy and sad at the same time is the most studied mixed emotion (Berrios et al., Citation2015), many more combinations have been reported, such as a combination of happiness and fear (Andrade & Cohen, Citation2007), or of happiness and guilt (Mukhopadhyay & Johar, Citation2007). In a compelling meta-analysis, Berrios et al. (Citation2015) sampled more than 60 published studies and concluded that elicitation of mixed emotions is possible across experimental settings and with varying measurement techniques.

Mixed emotions have an effect upon observers. For instance, Das and colleagues found that ‘moving’ films (containing mixed affective content) were more persuasive than movies with more unidimensional content (Das et al., Citation2017). Indeed, other lines of work have also shown that media with mixed affective content, impact viewers/readers/listeners more than cultural artifacts without mixed affect (Appel et al., Citation2019; Oliver et al., Citation2014; Slater et al., Citation2019). An example is the work by Ott et al. (Citation2021) who show that eudaimonic (‘meaningful’) Hollywood movies lead to a wider range of experienced emotions as compared to non-eudaimonic films (see also, Das & Te Hennepe, Citation2022; Oliver & Bartsch, Citation2011; Oliver & Raney, Citation2011). Another example comes from Hunter and colleagues who showed that short musical excerpts with mixed indicators of musical feelings (e.g., fast tempo combined with minor key) led to stronger (and mixed) emotional response (Hunter et al., Citation2010). In this paper I cannot do justice to this research field, and I will not attempt to fully review the empirical findings concerning mixed emotions. What is of importance is that mixed emotions exist, and that they seem to have a considerable impact on observers. This should make them of importance for cognitive neuroscientists interested in understanding emotions.

A fierce (and dividing) debate within the psychology of emotions is the issue whether there is a restricted set of basic emotions (e.g., Panksepp, Citation2004), versus constructivists arguing that emotions are points on an affective continuum (Barrett et al., Citation2007; Lindquist et al., Citation2012). I choose to leave this debate aside in this paper. First, I cannot do justice to the complexity of the debate, and second I find the theoretical debate to be too polarized to be a productive basis for empirical research. Third, taking a stance in this debate is not crucial for developing the MA-EM model. Whatever theoretical position one takes, it seems from empirical literature that people can experience mixed emotions and it is not imperative to stick to one particular theory in order to study this topic.

1.2. Moral ambiguity

Another potent driver of human emotion and reflection is moral ambiguity. Moral ambiguity is the phenomenon that a person’s intentions and moral behavior seem contradictory or ambiguous. This is, for instance, the case when a morally nice character acts in a morally condemnable way. Humanities scholars have argued that moral ambiguity evokes more ‘moral rumination’ (Dewey, Citation1891) than a simple ‘good guy, bad guy’ narrative (Berkum, Citation2019; Nussbaum, Citation2003; Koopman & Hakemulder, Citation2015). Indeed, there are empirical indications that morally ambiguous characters are considered more interesting (Eden et al., Citation2017; ’t Hart et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). Fiction can trigger moral deliberation, especially when the content of fiction is not easily resolvable, or conflicting (Eden et al., Citation2017; Lewis et al., Citation2014; Ommen et al., Citation2015).

The influence of moral ambiguity is shown in a study in which participants watch an episode from the series The Sopranos (Eden et al., Citation2017). In one episode there is a moral conflict when a therapist ruminates whether she should ask Tony Soprano (a mafia leader) to molest the man who had sexually assaulted her (but was not punished legally), or whether she should keep her professional and private life separated. Viewers appreciated the episode better, and find the character more interesting when this moral conflict is present versus when it is absent (Eden et al., Citation2017). Moreover, viewers engage in more moral and emotional rumination themselves after watching the ambiguous episode. Put differently, moral ambiguity is something that is liked by viewers, and it makes them think more about the content of the episode. A related phenomenon occurs when readers are asked to reflect upon unlikable characters to whom something bad happens (‘Schadenfreude’; ‘t Hart et al., Citation2018, Citation2019). A conflict occurs in the reader: It is not morally acceptable to feel happy about something bad happening to another person, yet the reader notices feeling happy. This is another example of how conflicting moral content heightens interest in readers or viewers. Interestingly, moral ambiguity may stimulate critical thinking (Hakemulder et al., Citation2016; Koek et al., Citation2017), ‘the ability to perform reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do’ (Ennis, Citation2011; Ennis, Citation2015).

Morality is closely linked to intentions. To understand whether a person or character is morally ambiguous or not, we need to establish the intent behind the person’s behavior. This link between morality and intentions is important to understand the neurocognitive MA-EM model described below, in particular the mentalizing route in the model.

2. A new taxonomy

The research on mixed emotions and morality is scattered, with a variable and confusing terminology. Mixed emotions are studied in research fields separate from ambiguous morality, and within each research topic there is ample terminological confusion. A new conceptual framework is useful to overcome existing terminological barriers. Here I present the start of such a unifying framework. In doing so, I will not introduce new terminology, but will aim to clarify existing terms.

There is consensus about the fact that the term ‘mixed emotions’ is unable to capture the full spectrum of emotions, and that hence a more elaborate taxonomy is needed (Larsen & McGraw, Citation2014; Maksimainen et al., Citation2019). Conflicting emotions are emotions which are direct (‘polar’) opposites. Indeed, most empirical work on the topic is concerned with conflicting emotions, the most well-known being feeling sad and happy at the same time (Larsen & McGraw, Citation2014). Mixed emotions on the contrary consist of a mixture of emotions that are not necessarily opposites. Examples are happiness and fear (Andrade & Cohen, Citation2007), or happiness and guilt (Mukhopadhyay & Johar, Citation2007).

Conflicting and mixed emotions share the feature that it is clear what the emotions are. This is importantly different for ambiguous emotions. In the case of ambiguous emotions, it is clear that the character has an emotional experience, but it is unclear what the emotion is. Ambiguous emotions have been of special interest in the study of literature, given the importance of ambiguity in literary narratives (Cave, Citation2016; Hakemulder, Citation2021; Koopman & Hakemulder, Citation2015; Menninghaus et al., Citation2017; Muth & Carbon, Citation2016; Muth et al., Citation2018), and probably for fiction at large since they are also prominent in research using films as stimuli (Das et al., Citation2017; Oliver et al., Citation2014; Ott et al., Citation2021). In the framework I distinguish between cases in which the emotions are clear but conflicting or mixed on the one hand, and emotions which are ambiguous on the other hand. The first are referred to as ‘mixed emotions’ and the second as ‘ambiguous emotions’ (Box 1).

Similarly, for morality I distinguish between conflicting morality or mixed morality, and ambiguous morality. Conflicting or mixed morality is the classical case when two opposites reside within the same person. For instance, a morally good person acting in a morally repulsive fashion. Cases in which the more than one clearly identifiable moral intention plays a role will be referred to as ‘mixed morality.’ In ambiguous morality on the other hand, the intention or moral status of the character is unclear. This is the case when we cannot discern the moral content of the behavior, but we do observe the other person to behave in a morally unexpected way. An example is the case of observing someone taking on a threatening pose toward someone else. You will infer that there is an intention or morality behind this behavior, but it is unclear what the intention is. Is the threatening person trying to be funny, acting out a scene from a movie, or is he or she threatening to actually attack or harm the other? These will be called ‘ambiguous morality’ (Box 1).

The distinctions between mixed and ambiguous morality are less clear in the case of morality as compared to emotions. The example also makes clear the tight link between what I call morality here and intentions, as mentioned previously. The example should also make it evident that the categories have somewhat fuzzy boundaries. Simple, clear emotions will be referred to as ‘unidimensional’ emotions. For cases in which the morality is clear, the term ‘non-ambiguous morality’ will be used.

Box 1. A taxonomy for mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality. Note that the boundaries between these categories are more fuzzy than the description in Box 1 suggests. Still the taxonomy can be helpful to use as a starting point and to use a common nomenclature across scientific disciplines.

3. MA-EM: A neurocognitive model

The MA-EM model is a descriptive boxological model which intends to form the basis for hypotheses about the neurocognitive basis of understanding mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality. It is a model of the observer of emotions or morality, not of the one experiencing those emotions, although the one observing may naturally also experience the emotions observed, especially from a simulationist point of view. Note that the model is not necessarily about knowing ‘true’ intentions of others: the model is about perception, not about ‘correct’ inference of emotions and morality. The model is meant to guide the field in devising interesting research questions and accompanying hypotheses.

At the base of the model are two distinct neurocognitive routes which are important for perceiving emotions and intentions. The first one is simulation. During simulation, the observer mimics or resonates with the emotion of someone else (Gallese et al., Citation2004; Keysers & Gazzola, Citation2006; Wilson-Mendenhall, Citation2017). Simulation invokes activation in brain regions also involved in actual perception. For instance, simulation of emotions evokes activity in regions implicated in experiencing emotions (Barsalou et al., Citation2008; Keysers & Gazzola, Citation2006; Willems & Casasanto, Citation2011; Willems et al., Citation2011; Wilson-Mendenhall, Citation2017; Zwaan, Citation2004).

The second route involves reflective processing of another person’s intentions or feelings. This mentalizing route is traditionally considered reflective (Frith & Frith, Citation2006; Goldman, Citation2006; Jacobs & Willems, Citation2018), but empirical work has shown that mentalizing can also be implicit or automatic (Bardi et al., Citation2017; Schneider et al., Citation2015; Van Overwalle & Vandekerckhove, Citation2013). Mentalizing evokes activation in the neural mentalizing network (Amodio & Frith, Citation2006; Bardi et al., Citation2017; Siegal & Varley, Citation2002; Van Overwalle & Baetens, Citation2009; Van Overwalle & Vandekerckhove, Citation2013; Willems & Varley, Citation2010). The fact that mentalizing is related to understanding other people’s intentions is the reason to couple morality to the mentalizing network in the MA-EM model.

Note that simulation and mentalizing are known under a plethora of other terms in the literature. An important conceptualization is the one by Goldman (Goldman, Citation2006) who distinguishes between low-level and high-level simulation. Understanding the intentions and feelings of others can be considered a form of mental simulation, in which we use our own intention system to understand the intentions and feelings of others (the central thesis of simulation theory in philosophy). This is the reason why Goldman refers to mental state understanding (mentalizing) as ‘high-level simulation.’ What Goldman calls high-level simulation is called mentalizing in this paper. In this paper I keep with the psychological literature which distinguishes mental simulation (be it, for instance, emotional or sensori-motor simulation) from mentalizing. An echo of the simulation – mentalizing distinction is found in Bruner’s famous distinction between the ‘landscape of action’ (simulation), and the ‘landscape of consciousness’ (mentalizing; Bruner, Citation1986).

Above I introduced emotion recognition as a simulative process, and mentalizing as a mainly reflective process. This is an oversimplication. Recent years have seen a shift in focus in the intention/mentalizing literature from the traditional focus on explicit understanding of others’ beliefs (e.g., false belief task), to an interest in how intention understanding can be implicit. For the MA-EM model it is relevant to note that both emotion understanding and intention understanding can be implicit, and that one can reflect on both emotions and intentions of others ().

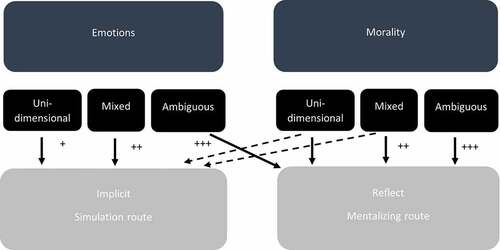

Figure 1. A simplified scheme of the relation between implicit simulation of emotional or moral content, and explicit, reflective comprehension of emotions and morality. Emotions pair most with simulation, whereas morality understanding relies mostly on mentalizing. However, emotions can be reflected upon, activating the mentalizing route, and morality can be perceived implicitly, activating the simulation route.

Hypotheses

A general prediction from the model is that both emotions and morality can drive both neurocognitive systems, but that emotions most readily activate the simulation route, whereas morality (and understanding the underlying intentions) typically activates the mentalizing route. When emotion understanding or morality understanding is implicit, it leads to simulation, when emotions and morality are reflected upon, they lead to mentalizing ().

Regarding emotions, the prediction of the model is that mixed emotions lead to stronger activation of the simulation route as compared to unidimensional emotions. In the case of mixed emotions, the different emotions are recognizable. This is not the case for ambiguous emotions. Since ambiguity in emotions cannot be readily mapped onto emotions, these will rely on the mentalizing route instead ().

Figure 2. The MA-EM model for the observation of emotions and morality. The model predicts that emotions and moral intentions (‘morality’) are processed neurally by mapping onto a simulation route (left) and onto a mentalizing route (right). Separate predictions are made for unidimensional, mixed, and ambiguous emotions and morality. For the taxonomy see Box 1, for specific hypotheses see the text. The ‘+’ signs signal the predicted strength of an effect: the more ‘+,’ the stronger the hypothesized effect is.

For morality it is predicted that mixed morality leads to stronger mentalizing route activation as compared to unidimensional morality (). Ambiguous morality is an even stronger driver of reflection (see above), and is therefore expected to activate the mentalizing route the most.

In the above predictions I have hypothesized that ambiguous emotions and morality have strong effects. There is some evidence for this in the literature (see above), but the conjecture needs a more firm empirical basis. Another open issue is whether mixed or ambiguous emotions and morality drive the neurocognitive routes most. It could be that the neurocognitive routes are taxed more strongly by the ambiguous as compared to the mixed narratives. This would be predicted from a semantic instability perspective, in which ambiguity invites the reader to actively construct meaning (Hakemulder, Citation2021; Muth & Carbon, Citation2016). On the other hand, stronger activation to the mixed as compared to ambiguous emotions and morality would be expected from an ‘ease of processing’ perspective (Alter, Citation2013; Graf & Landwehr, Citation2015; Rawson & Dunlosky, Citation2002). After all, because the constitutive parts are clear, mixed emotions and morality are easier to understand as compared to ambiguous emotions and morality.

It is next hypothesized that individuals will differ in the effort they put into understanding ambiguous stimuli. Some readers will simply not engage in such construction (Hartung et al., Citation2017), and those participants will not show differential responses (both neural and behavioral) to ambiguous versus non-ambiguous emotions and morality. Note that context may also play a decisive role here: in some contexts individuals may not engage in meaning construction in trying to understand ambiguous emotions or morality. Although this is possible, previous literature which finds effects of ambiguous emotions and morality show that these effects are pervasive and can be simply induced by watching a short film (Appel et al., Citation2019; Berrios et al., Citation2015; Das et al., Citation2017; Das & Te Hennepe, Citation2022; Ott et al., Citation2021; Slater et al., Citation2019). This suggests that the effects of ambiguous emotions and morality come about with little effort.

Link to brain regions

Although cognitive neuroscience is giving up its obsession with localization of cognitive function (Anderson, Citation2014), a neurocognitive model cannot do without some suggestion of where in the brain effects of mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality are expected to occur. The simulation route taxes parts of the brain which are involved in experiencing actual emotions. That is, we internally simulate the emotions that we perceive in someone else, drawing upon brain regions that are involved in experiencing the emotions ourselves (Goldman, Citation2006; Jacobs, Citation2015a; Jacobs & Willems, Citation2018). Candidate brain structures/regions are the limbic system, the orbitofrontal cortex, the insula, the anterior temporal lobe and the posterior cingulate cortex (Lindquist et al., Citation2012; Phan et al., Citation2002).

The neural mentalizing network is the natural place to be associated with the mentalizing route in the model. Neural structures that are part of this network are the medial prefrontal cortex, the precuneus, the anterior temporal poles and the temporo-parietal junctions (Amodio & Frith, Citation2006; Kovács et al., Citation2014; Nijhof et al., Citation2018; Van Overwalle & Vandekerckhove, Citation2013).

4. Narratives as the ultimate vehicle for mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality

Finally I want to point to narratives as a particularly promising stimulus to investigate the effects of mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality. Humans like narratives, they can hardly help being drawn into them. Indeed, the power of narratives for human cognition has long been recognized (Boyd, Citation2009; Bruner, Citation1984, Citation1986; Burke, Citation2010; Cave, Citation2016; Dewey, Citation1891; Gerrig, Citation1999; Keen, Citation2007; Labov & Waletzky, Citation1997; M. M. Nussbaum, Citation1997; Sanford & Emmott, Citation2012; Tan, Citation2013; Vygotsky, Citation1978), leading Bruner to famously postulate ‘the narrative mode’ as the optimal format to share information (Bruner, Citation1986). Many scholars consider narratives as a flight simulator for learning about other people’s emotions and moral intentions (Fesmire, Citation2003; Gerrig, Citation1999; Gottschall, Citation2013; Jacobs & Willems, Citation2018;van Krieken, Citation2018; Mar & Oatley, Citation2008; Oatley, Citation2016). This makes narratives an ideal testbed for studying emotions and morality in their natural habitat (Burke, Citation2010; Goldie, Citation2012; Hakemulder, Citation2000; Hakemulder et al., Citation2016; Hogan, Citation2011; Jacobs, Citation2015b; Jacobs et al., Citation2015; Jacobs & Willems, Citation2018; Salgaro et al., Citation2021). Moreover, within narrative, mixed or ambiguous emotions can be elicited easily and quickly (Berrios et al., Citation2015). For instance, 200 words long textoids were successfully used to study mixed morality (’t Hart et al., Citation2019). Another example are 700 words long excerpts from James Joyce to study emotions and morality (Cupchik et al., Citation1998). In our own work we have studied responses to narratives (using cognitive neuroscience methods) in much longer narratives, of several thousands of words long (Eekhof et al., Citation2018, Citation2021; Hartung et al., Citation2017, Citation2021; Mak & Willems, Citation2019). There is no doubt such narratives can readily evoke mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality.

Cognitive neuroscience has recently embraced stimuli high in narrativity such as movies, audio stories, or literary texts (see, Willems et al., Citation2020 for an overview). Next to being interesting stimuli since they evoke emotions and intentions in readers and observers, narratives lead to very efficient datasets. The efficiency lies in the fact that the natural richness of narratives means that data that are acquired while people process narratives, can be used to answer a multitude of questions which go beyond the original purpose for which the data were acquired. Examples of large datasets in which participants listened to or read narratives, which are openly available are the NARRATIVES dataset (Nastase, Liu et al., Citation2020), and the Eyelit dataset (Mak & Willems, Citation2021). Finally, narratives fit the current interest in contextualized and more naturalistic stimuli (Nastase, Goldstein et al., Citation2020; Willems & Peelen, Citation2021).

This call to attention for narratives does not imply that mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality are only or merely part of a fictional world. In our daily lives we encounter such mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality often. Narrative creators capitalize on our interest in such signals and that is why they are so often part of fiction worlds, but the approach extends to social interaction ‘as we know it,’ such as in dialogue.

Conclusion

‘It sometimes happens, that both the passions exist successively, and by short intervals; sometimes they destroy each other […]; and sometimes that both of them remain united in the mind.’ (Hume, Citation1739, p. 488) (my emphasis)

In his computational theory of cognition, David Hume postulated in 1739 that two ‘passions’ could exist united in the mind. Indeed, other fields of science have found that people not only are capable of perceiving mixed emotions, but that such emotions impact us considerably. Here I tried to bring the existence and force of mixed and ambiguous emotions to the attention of the cognitive neuroscience community. Cognitive neuroscientists miss out on an important part of human cognition if they do not consider the ambiguous and mixed nature of the emotions that we experience and perceive in others. A natural extension is to include the observation of mixed or ambiguous intentions, and accompanying morality of others into this scheme. Understanding other people’s moral intentions is similarly a process in which ambiguous and mixed signals play an important role. In the MA-EM model I coupled mixed and ambiguous emotions and morality to the simulation and mentalizing routes in the brain as a tentative model which can guide experimentation. If the model proves to be wrong in all aspects, but does lead to increased attention for this topic, I will consider this publication a success.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO-Vidi- 276-89-007), the NWO Gravitation Language in Interaction grant (NWO-024.001.006), and the ELIT ITN grant (ERC-ITN 860516). I thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alter, A. L. (2013). The benefits of cognitive disfluency. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413498894

- Amodio, D. M., & Frith, C. D. (2006). Meeting of minds: The medial frontal cortex and social cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci, 7(4), 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1884

- Anderson, M. L. (2014). After Phrenology: Neural Reuse and the Interactive Brain. A Bradford Book.

- Andrade, E. B., & Cohen, J. B. (2007). On the consumption of negative feelings. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1086/519498

- Appel, M., Slater, M. D., & Oliver, M. B. (2019). Repelled by virtue? The dark triad and eudaimonic narratives. Media Psychology, 22(5), 769–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2018.1523014

- Bardi, L., Desmet, C., Nijhof, A., Wiersema, J. R., & Brass, M. (2017). Brain activation for spontaneous and explicit false belief tasks overlaps: New fMRI evidence on belief processing and violation of expectation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(3), 391–400.

- Barrett, L. F., Lindquist, K. A., & Gendron, M. (2007). Language as context for the perception of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(8), 327–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.003

- Barsalou, L. W., Santos, A., Simmons, W. K., & Wilson, C. D. (2008). Language and simulation in conceptual processing. In M. De Vega, A. M. Glenberg, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Symbols (pp. 123–145). Embodiment, and Meaning. Oxford University Press.

- Berkum, J. J. A. (2019). Language Comprehension and Emotion. The Oxford Handbook of Neurolinguistics (pp. 86–102). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190672027.013.29

- Berrios, R., Totterdell, P., & Kellett, S. (2015). Eliciting mixed emotions: A meta-analysis comparing models, types, and measures. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00428

- Boyd, B. (2009). On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction. Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. S. (1984). Language, Mind, and Reading. Heinemann.

- Bruner, J. S. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard University Press.

- Burke, M. (2010). Literary Reading, Cognition and Emotion: An Exploration of the Oceanic Mind. Taylor & Francis.

- Cave, T. (2016). Thinking with Literature: Towards a Cognitive Criticism. Oxford University Press.

- Cupchik, G. C., Oatley, K., & Vorderer, P. (1998). Emotional effects of reading excerpts from short stories by James Joyce. Poetics, 25(6), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-422X(98)

- Das, E., Nobbe, T., & Oliver, M. B. (2017). Health communication| moved to act: examining the role of mixed affect and cognitive elaboration in “accidental” narrative persuasion. International Journal of Communication, 11(1), 17.

- Das, E., & Te Hennepe, L. (2022). Touched by Tragedy. Journal of Media Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000329

- Dewey, J. (1891). Moral Theory and Practice. International Journal of Ethics, 1(2), 186–203.

- Eden, A., Daalmans, S., Ommen, M. V., & Weljers, A. (2017). Melfi’s choice: morally conflicted content leads to moral rumination in viewers. Journal of Media Ethics, 32(3), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/23736992.2017.1329019

- Eekhof, L. S., Eerland, A., & Willems, R. M. (2018). Readers’ insensitivity to tense revealed: no differences in mental simulation during reading of present and past tense stories. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.121

- Eekhof, L. S., Kuijpers, M. M., Faber, M., Gao, X., Mak, M., Hoven, E., & Willems, R. M. (2021). Lost in a Story, Detached from the Words. Discourse Processes, 58(7), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1857619

- Ennis, R. (2011). Critical Thinking. Inquiry: Critical Thinking across the Disciplines, 26(2), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.5840/inquiryctnews201126215

- Ennis, R. H. (2015). Critical Thinking: A Streamlined Conception. In M. Davies & R. Barnett (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education (pp. 31–47). Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Fesmire, S. (2003). John Dewey and Moral Imagination: Pragmatism in Ethics. Indiana University Press.

- Frith, C. D., & Frith, U. (2006). The neural basis of mentalizing. Neuron, 50(4), 531–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.001

- Gallese, V., Keysers, C., & Rizzolatti, G. (2004). A unifying view of the basis of social cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(9), 396–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.07.002

- Gerrig, R. J. (1999). Experiencing Narrative Worlds: On the Psychological Activities of Reading. Westview Press.

- Goldie, P. (2012). The Mess Inside: Narrative, Emotion, and the Mind. Oxford University Press.

- Goldman, A. (2006). Simulating minds. Oxford University Press.

- Gottschall, J. E. (2013). The Storytelling Animal. Mariner Books. https://www.bol.com/nl/f/the-storytelling-animal/9200000000620071/

- Graf, L. K. M., & Landwehr, J. R. (2015). A dual-process perspective on fluency-based aesthetics: The pleasure-interest model of aesthetic liking. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 19(4), 395–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315574978

- Hakemulder, F. (2000). The moral laboratory: Experiments examining the effects of reading literature on social perception and moral self-knowledge. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Hakemulder, F., Fialho, O., & Bal, M. (2016). Learning from literature: Empirical research on readers in schools and at the workplace. In M. Burke, O. Fialho, & S. Zyngier, (Eds.). Scientific Approaches to Literature in Learning Environments. 19–38. John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://benjamins.com/catalog/lal.24.02hak

- Hakemulder, F. (2021). Finding meaning through literature: foregrounding as an emergent effect. Anglistik: International Journal of English Studies, 31(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.33675/ANGL/2020/1/8

- Hartung, F., Hagoort, P., & Willems, R. M. (2017). Readers select a comprehension mode independent of pronoun: Evidence from fMRI during narrative comprehension. Brain and Language, 170(3), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2017.03.007

- Hartung, F., Wang, Y., Mak, M., Willems, R. M., & Chatterjee, A. (2021). Aesthetic appraisals of literary style and emotional intensity in narrative engagement are neurally dissociable. Communications Biology, 4(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02926-0

- Hogan, P. C. (2011). What Literature Teaches Us about Emotion. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511976773

- Hume, D. (1739). A treatise of human nature. Clarendon Press.

- Hunter, P. G., Schellenberg, E. G., & Schimmack, U. (2010). Feelings and perceptions of happiness and sadness induced by music: Similarities, differences, and mixed emotions. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 4(1), 47–56.

- Jacobs, A. M. (2015a). Neurocognitive Poetics: Methods and models for investigating the neuronal and cognitive- affective bases of literature reception. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 186. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00186

- Jacobs, A. M. (2015b). Towards a Neurocognitive Poetics Model of Literary Reading. Cognitive Neuroscience of Natural Language Use (pp. 55–76). Cambridge University Press.

- Jacobs, A. M., Võ, M. L.-H., Briesemeister, B. B., Conrad, M., Hofmann, M. J., Kuchinke, L., Lüdtke, J., & Braun, M. (2015). 10 years of BAWLing into affective and aesthetic processes in reading: What are the echoes? Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00714

- Jacobs, A. M., & Willems, R. M. (2018). The fictive brain: neurocognitive correlates of engagement in literature. Review of General Psychology, 22(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000106

- Keen, S. (2007). Empathy and the Novel. Oxford University Press.

- Keysers, C., & Gazzola, V. (2006). Towards a unifying neural theory of social cognition. Prog Brain Res, 156(2), 379–401.

- Koek, M., Janssen, T., Hakemulder, F., & Rijlaarsdam, G. (2017). Literary reading and critical thinking. Scientific Study of Literature, 6(2), 243–277.

- Koopman, E. M. E., & Hakemulder, F. (2015). Effects of literature on empathy and self-reflection: a theoretical-empirical framework. Journal of Literary Theory, 9(1), 79–111. https://doi.org/10.1515/jlt-2015-0005

- Kovács, Á. M., Kühn, S., Gergely, G., Csibra, G., & Brass, M. (2014). Are all beliefs equal? Implicit belief attributions recruiting core brain regions of theory of mind. PLOS ONE, 9(9), e106558. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106558

- Krieken, K. W. M. (2018). How reading narratives can improve our fitness to survive. A mental simulation model. Narrative Inquiry, 28(1), 140–161. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.17049.kri

- Labov, W., & Waletzky, J. (1997). Narrative analysis: Oral versions of personal experience. Journal of Narrative & Life History, 7(1–4), 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1075/jnlh.7.02nar

- Larsen, J. T., & McGraw, A. P. (2014). The case for mixed emotions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(6), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12108

- Larsen, J. T., McGraw, A. P., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2001). Can people feel happy and sad at the same time? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(4), 684–696. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.684

- Lewis, R. J., Tamborini, R., & Weber, R. (2014). Testing a dual‐process model of media enjoyment and appreciation. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 397–416.

- Linden, D. J. (2021). A neuroscientist prepares for death. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/12/terminal-cancer-neuroscientist-prepares-death/621114/

- Lindquist, K. A., Wager, T. D., Kober, H., Bliss-Moreau, E., & Barrett, L. F. (2012). The brain basis of emotion: A meta-analytic review. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35(3), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X11000446

- Mak, H. M. L., & Willems, R. M. (2021). Eyelit: Eye-movement and reader response data during literary reading [Txt]. Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS). https://doi.org/10.17026/DANS-ZQK-ZMQS

- Mak, M., & Willems, R. M. (2019). Mental simulation during literary reading: Individual differences revealed with eye-tracking. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 34(4), 511–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2018.1552007

- Maksimainen, J. P., Eerola, T., & Saarikallio, S. H. (2019). Ambivalent emotional experiences of everyday visual and musical objects. SAGE Open, 9(3), 2158244019876319. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019876319

- Mar, R. A., & Oatley, K. (2008). The function of fiction is the abstraction and simulation of social experience. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(3), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00073.x

- Menninghaus, W., Wagner, V., Hanich, J., Wassiliwizky, E., Kuehnast, M., & Jacobsen, T. (2015). Towards a Psychological Construct of Being Moved. PLOS ONE, 10(6), e0128451.

- Menninghaus, W., Wagner, V., Wassiliwizky, E., Jacobsen, T., & Knoop, C. A. (2017). The emotional and aesthetic powers of parallelistic diction. Poetics, 63, 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2016.12.001

- Mukhopadhyay, A., & Johar, G. (2007). Tempted or not? - the effect of recent purchase history on responses to affective advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(4), 445–453. https://doi.org/10.1086/510218

- Muth, C., & Carbon, -C.-C. (2016). SeIns: Semantic instability in art. Art and Perception, 4(1–2), 145–184. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134913-00002049

- Muth, C., Hesslinger, V. M., & Carbon, -C.-C. (2018). Variants of semantic instability (SeIns) in the arts: A classification study based on experiential reports. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 12(1), 11–23.

- Nastase, S. A., Goldstein, A., & Hasson, U. (2020). Keep it real: Rethinking the primacy of experimental control in cognitive neuroscience. NeuroImage, 222, 117254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117254

- Nastase, S. A., Liu, Y.-F., Hillman, H., Zadbood, A., Hasenfratz, L., Keshavarzian, N., Chen, J., Honey, C. J., Yeshurun, Y., Regev, M., Nguyen, M., Chang, C. H. C., Baldassano, C., Lositsky, O., Simony, E., Chow, M. A., Leong, Y. C., Brooks, P. P., Micciche, E., & Hasson, U. (2020). Narratives [Data set]. Openneuro. https://doi.org/10.18112/OPENNEURO.DS002345.V1.1.4

- Nijhof, A. D., Bardi, L., Brass, M., & Wiersema, J. R. (2018). Brain activity for spontaneous and explicit mentalizing in adults with autism spectrum disorder: An fMRI study. NeuroImage: Clinical, 18, 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2018.02.016

- Nussbaum, M. (1997). Poetic Justice: The Literary Imagination and Public Life. Beacon Press.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2003). Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge University Press.

- Oatley, K. (2016). Fiction: Simulation of Social Worlds. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(8), 618–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.06.002

- Oliver, M. B., & Bartsch, A. (2011). Appreciation of Entertainment. Journal of Media Psychology, 23(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000029

- Oliver, M. B., Bartsch, A., & Hartmann, T. (2014). Negative emotions and the meaningful sides of media entertainment. In The positive side of negative emotions (pp. 224–246). The Guilford Press.

- Oliver, M. B., & Raney, A. A. (2011). Entertainment as pleasurable and meaningful: identifying hedonic and eudaimonic motivations for entertainment consumption. Journal of Communication, 61(5), 984–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01585.x

- Ommen, M. E., Van, Daalmans, S., & Weijers, G. W. M. (2015). Who is the doctor in this House? Analyzing the moral evaluations of medical students and physicians of House, M.D. AJOB Empirical Bioethics, 61–74.

- Ott, J. M., Tan, N. Q. P., & Slater, M. D. (2021). Eudaimonic media in lived experience: retrospective responses to eudaimonic vs. non-eudaimonic films. Mass Communication and Society, 24(5), 725–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2021.1912774

- Panksepp, J. (2004). Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press.

- Phan, K. L., Wager, T., Taylor, S. F., & Liberzon, I. (2002). Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: A meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. Neuroimage, 16(2), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2002.1087

- Rawson, K. A., & Dunlosky, J. (2002). Are performance predictions for text based on ease of processing? Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 28(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.28.1.69

- Russell, J. A. (2017). Mixed Emotions Viewed from the Psychological Constructionist Perspective. Emotion Review, 9(2), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916639658

- Salgaro, M., Wagner, V., & Menninghaus, W. (2021). A good, a bad, and an evil character: Who renders a novel most enjoyable?✰. Poetics, 87, 101550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101550

- Sanford, A. J., & Emmott, C. (2012). Mind, brain and narrative. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139084321

- Schneider, D., Slaughter, V. P., & Dux, P. E. (2015). What do we know about implicit false-belief tracking? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0644-z

- Siegal, M., & Varley, R. (2002). Neural systems involved in “theory of mind.” Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 3(6), 463–471.

- Slater, M. D., Oliver, M. B., & Appel, M. (2019). Poignancy and mediated wisdom of experience: narrative impacts on willingness to accept delayed rewards. Communication Research, 46(3), 333–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215623838

- Hart, B., Struiksma, M. E., van Boxtel, A., & van Berkum, J. J. A. (2018). Emotion in stories: facial EMG evidence for both mental simulation and moral evaluation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 613. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00613

- Hart, B., Struiksma, M. E., van Boxtel, A., & van Berkum, J. J. A. (2019). Tracking affective language comprehension: simulating and evaluating character affect in morally loaded narratives. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 318. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00318

- Tan, E. (2013). The empathic animal meets the inquisitive animal in the cinema: Notes on a psychocinematics of mind reading. In Psychocinematics: Exploring cognition at the movies (pp. 337–367). Oxford University Press.

- Van Overwalle, F., & Baetens, K. (2009). Understanding others’ actions and goals by mirror and mentalizing systems: A meta-analysis. NeuroImage, 48(3), 564–584.

- Van Overwalle, F., & Vandekerckhove, M. (2013). Implicit and explicit social mentalizing: Dual processes driven by a shared neural network. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00560

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard U Press.

- Willems, R. M., & Casasanto, D. (2011). Flexibility in embodied language understanding. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00116

- Willems, R. M., Clevis, K., & Hagoort, P. (2011). Add a picture for suspense: Neural correlates of the interaction between language and visual information in the perception of fear. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 6(4), 404–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsq050

- Willems, R. M., Nastase, S. A., & Milivojevic, B. (2020). Narratives for Neuroscience. Trends in Neurosciences, 43(5), 271–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2020.03.003

- Willems, R. M., & Peelen, M. V. (2021). How context changes the neural basis of perception and language. IScience, 24(5), 102392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102392

- Willems, R. M., & Varley, R. (2010). Neural Insights into the Relation between Language and Communication. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 203.

- Wilson-Mendenhall, C. D. (2017). Constructing emotion through simulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.015

- Zickfeld, J. H., Schubert, T., Seibt, B., & Fiske, A. P. (2018). Moving through the literature: what is the emotion often denoted being moved? Emotion Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073918820126

- Zwaan, R. A. (2004). The immersed experiencer: Toward an embodied theory of language comprehension. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation (Vol. 44, pp. 43–67). Academic Press.