?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

When assessing meat, consumers use a large number of perceived and objective quality cues. This study analyses consumers’ preferences for perceived and objective quality cues in traditional meat products, focusing on several cues largely unstudied to date. It relies on a labelled discrete choice experiment administered to consumers of Iberian ham, an archetypal traditional Spanish meat product. The results indicate that the feeding-and-management system (acorn-fed or fodder-fed) generally determines the consumers’ preferences, with objective quality cues (breed purity and slicing type) influencing preferences regardless of the management system and perceived quality cues linked to the high-natural-value production agrosystem of the Dehesa only doing so for the acorn-fed system. There is a high degree of heterogeneity among consumers’ preferences, especially for the agrosystem of origin, suggesting that campaigns to raise awareness about the associated environmental and sociocultural values and a package design referencing the agrosystem are useful business strategies to integrate this added value into the product.

Objective quality and agrosystem of origin largely determine consumers’ WTP

Written and graphic information on the agrosystem of origin (Dehesa) influences WTP

Environmental awareness campaigns and suitable package design are highly recommendable

Highlights

1. Introduction

Going far beyond classical economic considerations, consumers are guided by their perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, motivations and values—the so-called non-rational factors (Marreiros and Ness Citation2009)—when choosing food. In this regard, perceived quality involves consumer perceptions and beliefs about a product’s superiority to alternatives (Aaker Citation1991). This core concept is frequently defined in opposition to objective quality, such as that derived from product- and manufacturing-related factors involving measurable and verifiable standards (Zeithaml Citation1988).

When assessing meat, consumers use a large number of quality cues. The literature points to the relevance of both objective quality characteristics—such as those intrinsically linked to animal feeding or production process, which yield certain organoleptic features—and perceived quality cues—such as extrinsic attributes representing, for example, the origin of the product (see Becker Citation2000). Traditional meat products are a clear example of a foodstuff that yields both objective and perceived quality cues.

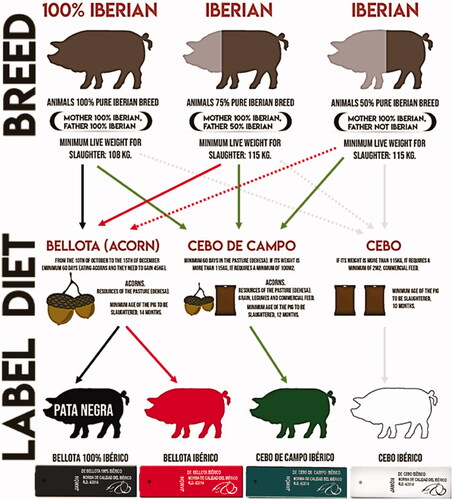

Spanish dry-cured ham is considered a prominent example of a traditional food (Resano et al. Citation2010). In particular, Iberian ham (IH), i.e. dry-cured ham produced from Iberian pigs, a breed native to the Iberian Peninsula, is one of the most widely-recognised Spanish meat products worldwide (Díaz-Caro et al. Citation2019). As established by the Quality Standard Regulation (BOE Citation2014), the main categories of IH basically relate to the combination of three different animal feeding and management systems (namely, acorn-fed, mixed-fed, and fodder-fed) and three different levels of breed purity (100%, 75%, and 50% Iberian) (see Appendix A for a description). Of those, the acorn-fed Iberian ham (aIH) is of the highest objective quality, having better organoleptic features (Ramírez and Cava Citation2007), and it is inextricably linked to the production agrosystem of origin called the Dehesa or Montado.

Given the variety of categories, there is some confusion when it comes to identifying the characteristics linked to each objective quality (Espejel et al. Citation2007; Resano et al. Citation2007; Mesías et al. Citation2009). As a result, consumers may perceive the different categories of IH as partial substitutes, often leading to product differentiation failures (Salazar-Ordóñez et al. Citation2018). While the previous literature provides evidence of this by focusing on consumers’ choices within the general denomination of dry-cured ham (e.g. Espejel et al. Citation2007; Resano et al. Citation2009) or IH specifically (e.g. Resano et al. Citation2007; Citation2009), there is a paucity of studies centred on the different objective quality product categories within IH. Mesías et al. (Citation2009), Sahelices et al. (Citation2017), and Díaz-Caro et al. (Citation2019) analyse the type of ham, based on the animal feeding and management regime (aIH and fodder-fed Iberian ham (fIH)), breed purity, purchase format, and price, together with cues such as origin, primarily conveyed through the protected designation of origin (PDO). The abovementioned studies show that the key variable is the perception of one objective quality feature: the type of ham, with aIH being preferred over the other types, and the origin (PDO) having some influence on consumers’ preferences. These factors are also commonly found to be drivers for purchasing fresh pork (Issanchou Citation1996; Grunert et al. Citation2004; Krystallis et al. Citation2007; Garavaglia and Mariani Citation2017), with the exception of the breed, which is only relevant for Iberian pork (García-Gudiño et al. Citation2021).

To focus on the origin in the study of dry-cured ham choices, the abovementioned researchers often use the PDO as a quality cue. This quality label, which is regulated by the European Union (OJ Citation2012), indicates a geographical place name linked to qualities and features of the natural environment and production method. However, as previously pointed out, the features of aIH are inherently tied to a production agrosystem of origin, the Dehesa, rather than a specific geographical location. This agrosystem is sparsely distributed across different geographical regions in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). It is characterised by a savannah-type open woodland landscape and is fundamentally linked to livestock production (Silva Pérez Citation2010). As a result, this ecosystem has a high environmental and cultural value (CAPDR Citation2017), providing ecosystem services such as biodiversity support, soil protection, regulation of the water cycle, and carbon sequestration (Garrido et al. Citation2017). Indeed, some areas of the Dehesa have been designated a Biosphere Reserve (CAPDR Citation2017). Moreover, the interaction between livestock farming and nature has shaped the history and culture of many towns in the surrounding areas, generating an extraordinary cultural heritage (Silva Pérez Citation2010). However, to the authors’ knowledge, the extent to which this production agrosystem of origin—the Dehesa—may have an impact on consumer choices has not been studied yet.

Therefore, the main objective of the present study is to analyse consumers’ preferences for and valuations of objective and perceived quality features in IHs and to examine the perceived potential link between the production agrosystem of origin cue and quality. The analysis is based on a labelled discrete choice experiment (DCE) with packages of aIH and fIH conducted through a large survey of IH consumers in southern Spain. In particular, understanding the impact of the production agrosystem of origin attribute on consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP) for IH can help the IH industry to design optimal sales strategies, especially in a purchasing context characterised by issues with product differentiation. Additionally, from a methodological point of view, it is the first such analysis of this sector using a labelled DCE design (instead of the more common unlabelled version).

2. Material and method

2.1. Data collection

The research relies on a face-to-face survey carried out in establishments where packages of aIH are sold, including supermarkets, food stores and gourmet shops. Participation in the survey was voluntary and not rewarded. Respondents were first informed about the objective of the study and assured that all data would be used exclusively for the purpose of the study, with no personal data being gathered. The survey was administered between November and December 2019.

A total of 1,158 surveys were conducted with consumers (aged 18 or above) living in Andalusia (population of 8.5 million people in 2020) who had bought IH (either acorn-fed or fodder-fed) at least once in the last year. Quota sampling was carried out in proportion to the population in provinces that produce (Cordoba, Huelva, and Seville) and do not produce aIH (the other Andalusian provinces), as well as rural and urban municipalities. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Appendix B. The questionnaire consisted of four blocks with information related to: i) respondents’ IH consumption habits; ii) the DCE exercise; iii) awareness of and knowledge about the Dehesa production agrosystem, including opinions about the environmental and cultural assets it generates; and iv) respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics.

2.2. Choice experiment: Empirical application

A hypothetical market was created to assess the impact of various product attributes on consumers’ choices and WTP, using the stated preference valuation technique of DCE. DCE is based on Lancaster’s Consumer Theory (Lancaster Citation1966) and Random Utility Theory (McFadden Citation1974), and has been widely used in the analysis of consumer preferences regarding meat products such as pork (Kallas et al. Citation2019) and IH (Díaz-Caro et al. Citation2019). A detailed description of the valuation technique is beyond the scope of this paper; interested readers should consult Hensher et al. (Citation2015).

The hypothetical market scenarios created included both the monetary attribute (Price)—essential in any utilitarian model—and non-monetary attributes selected on the basis of previous literature and direct observation of retailer meat shelves. Thus, the non-monetary attributes were the purity of the Iberian breed (Sahelices et al. Citation2017); purchase format (Mesías et al. Citation2009; Díaz-Caro et al. Citation2019) in terms of the slicing type; and the origin (Mesías et al. Citation2009; Sahelices et al. Citation2017; Díaz-Caro et al. Citation2019). The first two are objective quality features while the latter is a perceived quality cue, albeit linked to the objective characteristics in our case. Table presents the attributes and levels used in this DCE.

Table 1. Attributes and levels of the choice experiment.

The Price attribute was established based on the market prices of aIH and fIH types. The Iberian mixed-fed ham was not included in the analysis due to its significantly lower market share: 16% of IH marketed (MAPA Citation2019). The prices of the abovementioned products in a 100 g-package format were directly observed in different retailers (a total of 51 references), with the highest and lowest price for each type being discarded. Given that the two products have different price ranges, this attribute was specified as alternative-specific for both aIH and fIH types. Thus, the four price levels range between €13 and €22/100 g for acorn-fed ham and between €4 and €13/100 g for fIH, with equal differences of €3 between consecutive levels in both types. As shown in Figure (example of choice card), the prices were displayed in euros at the bottom of the choice card, which resembled a supermarket shelf.

Regarding the non-monetary attributes, the Iberian Breed purity included three levels (BOE Citation2014): the minimum legal level of 50% Iberian breed; the intermediate level of 75%; and the maximum of 100%. The second consists of the purchase format related to Slicing type, which is also relevant when choosing other meat products (Krystallis et al. Citation2007). This attribute had two levels: inclusion of the ‘Hand-sliced’ claim in the packaging design, and no mention of it on the packaging (which indicates the ham is ‘machine-sliced’).

To test the origin cue, the production agrosystem of origin Dehesa was included by means of two attributes appearing on the packaging. The first (Dehesa origin claim) consisted of including written information on the packaging to state the claim ‘Produced in the Dehesa’. The second (Pictorial representation of Dehesa) involves depicting the Dehesa through the use of images, as they are a more vivid, striking, and memorable stimulus (Underwood and Klein Citation2002). Pictorial representation of Dehesa attribute, included at the bottom of the package, consisted of four images (levels): 1) No background (no picture); 2) Background-Agricultural system (picture of a rural scene); 3) Background-Dehesa system (picture of the Dehesa); and 4) Background-Dehesa system with pigs (picture of the Dehesa with Iberian pigs foraging). Although the Quality Standard Regulation (BOE Citation2014) bars any evocation of the Dehesa for any IH other than aIH, the reference was also applied to fIH to check whether this claim per se influences the choices.

As shown in Figure , the choice cards recreated the frontFootnote1 of two 100 g packages (alternatives) for aIH and fIH. This product format was used as this type of packaging is highly standardised, which also facilitated the graphic design of the alternatives (reflecting the most typical layout found on the market). The two alternative packages of IH were conceived as part of a labelled DCE design, with pig feeding and management system during the production process being used as a differential element of the product type (‘the label’). This design was used under the assumption that the IH type (‘the label’) already evokes relevant additional information for the consumer beyond that included in the attributes and levels (Hensher et al. Citation2015): as animal feeding and management systems are objective quality features for ham, we analyse whether a link with the perceived quality is inferred. Additionally, this type of design allows the use of specific price vectors for each labelled alternative (acorn-fed and fodder-fed) (see Table ), meaning that the profiles established are realistic, as opposed to unlabelled DCE designs. Thus, in a labelled DCE specific effects of the attributes can be estimated for each alternative instead of generic parameters. In addition, a no-purchase option was added. Again, the aim was to make the choices more realistic. Furthermore, respondents were presented with a purchase scenario of a family event or group of 4-5 friends, given that buying IH (especially acorn-fed) products tends to be a planned purchase (they are typically consumed on special occasions).

2.3. Experimental design

Secondary information from other studies was used to anticipate the order of magnitude of the attributes in the consumer utility function. Based on this information, the priors for the non-monetary attributes were set close to zero with a positive sign (conservative approach), while the prior for the monetary attribute was assumed to have a negative sign with an order of magnitude two and three times higher for fodder-fed and acorn-fed alternatives, respectively, compared to the other attributes. An efficient design was employed, minimising the D-error by means of Bayesian techniques (Rose et al. Citation2011), using Ngene 1.2.1. It consisted of 24 choice sets distributed in 4 blocks of 6, presenting a D-error of 0.436. A pre-test of 40 interviews was carried out to verify the adequacy of the questionnaire and the experimental design.

2.4. Econometric specification

A random parameter logit model (RPLM) was employed. It is an improvement on conventional logistic models in that it offers flexible substitution patterns, and can accommodate panel data by allowing correlation within each individual’s choices (Lancsar and Louviere Citation2008). Likewise, it allows the researcher to model the heterogeneity of preferences across individuals, by enabling the parameters to vary randomly across them (Train Citation2003; Hensher et al. Citation2015). The RPLM approach has been widely used in the choice modelling literature, both in the analysis of consumer behaviour (Gracia Citation2014; Kallas et al. Citation2019) and in other valuation contexts (e.g. Granado-Díaz et al. Citation2020). We start from the conventional specification of the utility function, with n individuals, t choice sets and j alternatives:

[1]

[1]

where χ is the vector of the attributes and levels in the choice sets, βn is the vector of coefficients, Cjn is the component specific to the alternative and ε is the random error term (which is assumed to follow a Gumbel distribution). βn can be decomposed as βn=β + βzZn, with β referring to the vector of individual preferences regarding attributes and levels (randomly distributed in the population following a density function f (β│θ), where θ represents the parameters of the distribution), and βzZn representing the heterogeneity in the mean of the preferences associated with the attributes and levels (where βz is the vector of coefficients to estimate and Zn the vector of individual characteristics). Cjn is also composed as Cj+γzZn, with Cj being the alternative specific constant and γzZn representing the heterogeneity in the preferences associated with the alternatives (γz being the vector of coefficients to estimate).

The choices are modelled using a panel structure, so that the probability integral is a product of logistic formulas. Thus, the joint probability of individual n choosing alternative j in each of the choices T is:

[2]

[2]

where

is the sequence of choices of individual n. This integral does not have a closed-form solution, thus requiring an iterative process (Train Citation2003). As such, the model was estimated using 1000 Halton draws, assuming normal distribution in all parameters.

To gain a more in-depth understanding of the potential heterogeneity of consumers’ preferences for IH related to their knowledge and perceptions of different features of the Dehesa (involving environmental, landscape, and cultural dimensions, as mentioned above), interactions of related variables with the attributes and the alternative-specific constants (ASCs) were included. Furthermore, taste was also explored as it is a key feature of food; this element is considered a biological predisposition although preferences for taste may be adapted and modified by cultural factors (Shepherd Citation2011). Finally, consumers’ geographical location was also incorporated as it shapes their cultural context (Shepherd Citation2011). For example, different degrees of proximity to the Dehesa could mean different relationships with this production agrosystem: consumers who live nearby are more likely to be connected to the IH sector and its culture (as shown by Salazar-Ordóñez et al. (Citation2018), for other typical food products in the region). With regards to the modelling procedure, the interacting variables were first incorporated into a single-interaction RPLM to check the significance. Then, the most significant variables were included in the multiple-interaction RPLM to ultimately be able to select the best model in terms of goodness of fit and policy interpretation. Table presents the variables included in this final model.

Table 2. Variables related to the production agrosystem of origin Dehesa.

Consumers’ WTP values were estimated as the marginal rate of substitution between ham attributes and price (Hensher et al. Citation2015). The parametric bootstrapping approach proposed by Krinsky and Robb (Citation1986) was applied to empirically determine the WTP distributions. Total WTP estimates were calculated for different IH products. Additionally, two main profiles were established according to the consumers’ awareness of values attached to the Dehesa agrosystem: Aware of Dehesa values and Unaware of Dehesa values. The first profile represents users of the Dehesa agrosystem, described by ENVIV = 1 and VISIV = 1, respectively referring to people using the environmental services (e.g. hunting or mushroom/berry picking) provided by this system and having visited Dehesa countryside during the previous year, and CULTV = 7, i.e. those in complete agreement about the cultural values attached to this production agrosystem. The second profile represents non-users (ENVIV = 0 and VISIV = 0) who do not acknowledge the cultural values (CULTV ≤ 3).

3. Results

3.1. Modelling results

Table shows the results of the RPLM. As can be observed, it is highly significant and shows a notable goodness-of-fit (pseudo-R2 = 0.328). All the attribute parameters are significant—the mean and/or the interaction parameter—with most of them showing significant standard deviation parameters (meaning a high heterogeneity of preferences, as will be discussed further below). The ASCs (ASCa and ASCf, for aIH and fIH alternatives, respectively) are significant and positive, indicating consumers’ systematic preference for these product types (compared to the no-purchase alternative) due to reasons not directly related to the attributes considered. Both ASCs also show significant standard deviations, suggesting the existence of unobserved heterogeneity associated with each alternative.

Table 3. Random parameter logit model (RPLM).

The results of the model show a high degree of heterogeneity across the general preferences towards the IH alternatives, as observed with the two significant interactions with the ASCs. In particular, one of them suggests that consumers who had visited the Dehesa (VISIV) report a greater purchase intention (positive interaction with ASCa) for the case of the higher objective quality ham (aIH), and a lesser intention for fIH (negative interaction with ASCf). The other indicates that consumers who think that products produced in the Dehesa taste better (TASTEYES) have a greater probability of choosing both aIH and fIH compared to the no-purchase option, with the effect being much stronger in the case of the former.

With regards to the objective quality features, in the case of the Breed purity, as expected the results show significant consumer preferences for IHs with 75% and 100% purity, compared to 50%-Iberian, for both acorn-fed and fodder-fed options. The results also reveal a ranking of preferences, such that the higher the breed purity, the greater the utility—particularly for the fodder-fed alternative. With regards to the Slicing type, this attribute presents an asymmetric result, being statistically significant for fIH, but not for the acorn-fed product. However, the latter includes a significant positive interaction with knowledge of the Dehesa agrosystem (KNOW), showing a marked impact on the utility function compared to the main effect.

Regarding the attributes directly related to the agrosystem of origin, the claim ‘Produced in the Dehesa’ (Dehesa origin claim) is significant for aIH but not for fIH, with both showing non-significant standard deviations. Along with the fact that no highly-significant interaction is found for this attribute, this indicates a lack of preference heterogeneity. Conversely, the results found for the Pictorial representation of Dehesa hint at a higher level of heterogeneity related to this attribute. In this sense, the results show that the ‘Background-Agricultural system’ significantly and positively influences consumers’ utility function related to both aIH and fIH, with significant standard deviations also shown for both; the ‘Background-Dehesa system’ does not significantly influence consumers’ preferences for IH, regardless of the type, though the significant standard deviations for the two types of IH indicate heterogeneous preferences; and the ‘Background-Dehesa system with pigs’ significantly influences the consumers’ preferences for aIH but not for fIH, with non-significant standard deviations in both cases.

The preference heterogeneity related to the Pictorial representation of Dehesa is also reflected in the significant interactions found. The interaction between CULTV and ‘Background-Agricultural system’ is negative, suggesting that the stronger the belief about the close association of the Dehesa with traditions, folklore, and customs, the lower the utility from this agricultural image. This seems to indicate that consumers with strong beliefs on this subject reject representations that are unrelated to the production agrosystem of origin of the IH (though it is only the acorn-fed type for which the Dehesa clearly serves as a producer system). The interaction between ENVIV and ‘Background-Dehesa system’ shows that, irrespective of the type of IH, the utility associated with this picture increases when the consumer reports use values of the environmental services from the Dehesa. Likewise, consumers living in municipalities belonging to producing regions (RURPRO = 1) show a high level of disutility when the fIH packaging displays any picture of the Dehesa, which is not the case for aIH. The same effect is shown for those who live in producing provinces (PROPROV = 1) but only for ‘Background-Dehesa with pigs (fodder-fed)’. The interactions with RURPRO and PROPROV indicate that the presence of pictorial representations of the Dehesa on packages of fIH has an effect on consumers living near to this agrosystem, reducing their utility function. This finding could reflect the fact that such consumers have greater knowledge of these products, as the production of fIH is not necessarily related with this agrosystem.

3.2. Estimates of willingness to pay

Table presents the marginal WTP estimates derived from the RPLM. Observing the results, the higher order of magnitude for the ASCs compared to the attributes suggests that the type of IH largely accounts for the value the consumers assign to these products, thus confirming the suitability of using the labelled DCE design. In particular, the results for the ASCs show a marginal WTP for 100 g packages of basic aIH and fIH (i.e. without considering any attribute other than the type) of €19.5 and €12.7, respectively, while none of the attributes show WTP values even half as large as these estimates. For fIH, only ‘Breed purity-100% Iberian’ and ‘Hand-sliced’ claim present marginal WTP significantly different from zero, with estimates of around €6/100 g-package for both. In contrast, there are more features with significant marginal WTP values for aIH, including breed purity (€1.2 and €1.3/100 g-package for 75% and 100% purity, respectively), ‘Hand-sliced’ claim (€2.6/100 g-package), and the attributes related to the origin, with per 100 g-package values of €1.2 for the ‘Produced in the Dehesa’ claim, €2.0 for the ‘Background-Agricultural system’, and €0.8 for the ‘Background-Dehesa system’.

Table 4. Marginal willingness to pay (WTP) by attribute (in €/100 g-package of Iberian ham).

Comparing with estimates from previous studies, Díaz-Caro et al. (Citation2019) provide the only direct comparison of ham type for the 100 g-package format, indicating that consumers are willing to pay €10.9/100 g more for aIH compared to fIH. That figure is above the one obtained here (i.e. €6.8/100 g), but within the range of those reported by other studies focusing on whole-piece formats (considering a 40% ham yield for the whole piece—with the remaining part being bones and thick fats—estimations provided by Mesías et al. (Citation2009) and Sahelices et al. (Citation2017) would be €5/100 g and €8.3/100 g, respectively). Our interpretation of the discrepancy is that it may well be due to the different valuation approach used (e.g. labelled in our case and unlabelled in theirs, among other differences). As for breed purity, Díaz-Caro et al. (Citation2019) estimate that WTP values increase by €3/100 g for a breed purity-100% Iberian, though they do not distinguish between fIH and aIH. In this respect, Sahelices et al. (Citation2017) estimate a premium of €8.8 and €8.2/kg compared to 50% and 75% breed purity, respectively. Our results build on these previous results by showing the different magnitude of increases in consumers’ utility derived from breed purity-100% depending on IH type. With regards to the origin, Díaz-Caro et al. (Citation2019) highlight the effect of the producing region (using the claim ‘Spanish regions traditionally producing Iberian dry-cured ham’), estimating a difference in the WTP of €4.5/100 g. The difference between the values in their study and ours (where origin is either reflected by the ‘Produced in the Dehesa’ claim or the ‘Background-Dehesa system’) could be due to the different conceptualisation of the origin agrosystem.

Table presents the total WTP for the most common IH products, made up of combinations of the significant attributes. The table shows the products with the lowest and highest objective quality in terms of breed purity and feeding system, i.e. fodder-fed 50% IH and acorn-fed 100% IH, respectively. In addition, the fodder-fed 100% IH product was included for comparative purposes (even though it is almost non-existent in the market). Also shown are the estimates for different consumers profiles established according to their awareness of Dehesa values. The first finding worth mentioning is that, as expected, consumers’ WTP is higher for aIH compared to fIH, with ranges of €20.8-26.6/100g and €12.7-19.8/100g, respectively. In particular, the WTP of the highest objective quality product (acorn-fed with 100% breed purity and ‘Hand-sliced’) including the production agrosystem of origin cues (‘Produced in the Dehesa’ claim and ‘Background-Dehesa system’) is double that of the lowest quality product (fodder-fed with 50% breed purity, no ‘Hand-sliced’ claim and no picture). Additionally, the breed purity and slicing type claim are found to have different impacts on total WTP for the two types, with ‘Hand-sliced’ and 100%-Iberian showing a much greater influence on total WTP for fIH than for aIH. However, all these results change notably when taking into account the consumers’ awareness of Dehesa values.

Table 5. Total willingness to pay (WTP) for different Iberian ham products (in €/100 g-package of Iberian ham).

As shown in Table , consumers who are Aware of Dehesa values generally report a higher WTP for the acorn-fed ham, with the highest gap found for Product V, showing a 27% increase in WTP compared to those Unaware of Dehesa values. However, for fIH the effect is the opposite, with those Aware of Dehesa values presenting lower WTP than consumers with the opposite profile. For example, looking at Product VIII, the WTP reported by consumers Aware of Dehesa values is less than half that of consumers unaware of such values. In addition, unlike the aware consumers, the unaware ones assign a lower value to the ‘Background-Dehesa system’ and a higher value to the ‘Background-Agricultural system’ for both product types.

4. Discussion

The results point to different patterns of preferences for aIH and fIH in general, with the animal feeding and management system explaining much of the consumers’ preferences (especially for the acorn-fed type). Furthermore, the consumers value the ham with the lowest objective quality, the fodder-fed type, with other quality features such as breed purity (100%-Iberian) and slicing type (hand-sliced), while when choosing the acorn-fed type consumers were sensitive not only to breed purity (either at a 75% or 100% level) and slicing type, but also to perceived quality cues related to the production agrosystem of origin (i.e. ‘Produced in the Dehesa’ and ‘Background-Dehesa system’).

The results also suggest that objective quality directly related to the production process is greatly valued by consumers. Evidence of this is the large proportion of WTP values estimated for this product that are solely explained by the type of ham (acorn-fed or fodder-fed), together with significant marginal WTP values for breed purity. This finding adds to previous studies focusing on pork, such as Issanchou (Citation1996), who finds that consumers trust extensive management systems; Bredahl and Poulsen (Citation2002), who observe a link between perceived pork quality and production methods (including extensive outdoor production, feeding or breed); or Grunert et al. (Citation2004), who highlight the relevance for consumers of production process characteristics (including organic production and free-range systems). In addition, specifically for dry-cured ham, Mesías et al. (Citation2009) identify the ham type as a key driver of consumers’ preferences, with Sahelices et al. (Citation2017), and Díaz-Caro et al. (Citation2019) providing specific evidence of higher WTP values for aIH and breed purity-100%.

However, the results reveal issues with objective quality differentiation. For example, it could be argued that the strong preferences observed for 100%-Iberian fIH may reflect a quality differentiation failure. While this is not typically an option provided in the market (see Figure in Appendix A) due to its lower profitability, our results show marginal WTP values three times higher for the attribute 100%-Iberian breed purity for fIH compared to aIH. In particular, we cannot identify whether fIH is benefitting from a value transfer from the exalted objective quality of the 100%-Iberian acorn-fed hams, with the claim of ‘100% Iberian ham’ inaccurately conveying attributes such as extensive livestock management system and natural breeding. Hence, this behaviour could reflect a way of using purity as a trade-off for breeding and management so that the purity may compensate for the objective quality that ultimately is the consequence of the management and feeding system. This would represent a quality differentiation failure by consumers, especially considering that fIH typically comes from an intensive pig-meat production system, which is generally viewed as a negative cue (as shown by Bredahl and Poulsen Citation2002; Grunert et al. Citation2004). Particularly, the comparison of preferences of consumers who are aware and unaware of Dehesa values indicates that some of the consumers (i.e. those unaware of Dehesa values) could be experiencing such a failure.

Similarly, the hand-sliced claim also seems to act as a strong objective quality feature for both types of ham. For aIH, although the corresponding WTP is lower than the values for fIH, it stands out as the attribute with the highest WTP. For fIH, the hand-sliced claim is almost as important as breed purity, with both features representing 50% of the consumers’ WTP. This finding contradicts previous results (e.g. Mesías et al. Citation2009; Díaz-Caro et al. Citation2019) that show the purchase format has little relevance. However, the fact that these studies focus on different product formats—sliced and packed, over the counter, and whole ham for the case of Mesías et al. (Citation2009), and vacuum and modified atmosphere packaged for the case of Díaz-Caro et al. (Citation2019)—is most probably behind this discrepancy.

The production agrosystem of origin plays a different role depending on the type of ham. The references to the Dehesa on the packaging significantly improve the consumers’ utility from aIH but, as expected, this is not the case for fIH. To some extent, this finding mirrors those reported by Mesías et al. (Citation2009) and Sahelices et al. (Citation2017) for PDO certifications in IH; Fandos and Flavián (Citation2006) for PDO in Spanish dry-cured ham; Garavaglia and Mariani (Citation2017) for PDO of Italian dry-cured ham (‘Prosciutto di Parma’); or even for fresh pork (e.g. Glitsch Citation2000). However, our results build on these by specifically identifying the production agrosystem of origin (rather than a well-known label or a certain region) as a perceived quality cue helping to add value to a traditional food product, communicated by including either a text or a picture referring to the production agrosystem on the packaging.

The results also show that there is a high degree of heterogeneity in consumers’ preferences related to the production agrosystem of origin. For example, the inclusion of the ‘Background-Dehesa system’ increases the WTP for consumers who are aware of Dehesa values, while consumers living in producing areas reject the ‘Background-Dehesa system’ when it is displayed on a fIH package. Both effects are arguably related to consumers’ greater knowledge of the product (e.g. knowing that the fodder-fed type is not closely related to this agrosystem). In addition, the inclusion of ‘Background-Agricultural system’ decreases (increases) WTP values of those who are aware (unaware) of the Dehesa values, particularly when buying fIH. Whereas this may be related to a misconception of the Dehesa landscape held by unaware consumers (and the opposite for aware ones), it is also plausible that there is an aesthetic preference for the visual aspect of this picture (a kind of photo effect), especially for those who are not aware of the production agrosystem of origin. In this sense, an agricultural landscape might be more attractive and unusual, attracting unaware consumers’ initial attention (Clement et al. Citation2013) more than the photos regularly used to promote aIH, which always feature similar images (i.e. like the ones presented in both the ‘Background-Dehesa system’ and ‘Background-Dehesa system with pigs’). The results add to previous findings by Grunert et al. (Citation2014), who show that sustainability cues do not play a relevant role when they are represented by labels that consumers do not understand, and by Fandos and Flavián (Citation2006), who state that the PDO information conveyed using images (e.g. from the region of origin) improves consumer loyalty towards these products.

5. Conclusions

The results indicate that ham type largely determines consumers’ preferences towards Iberian ham, with differential preference patterns related to the attributes depending on the type. Objective quality features such as breed purity and slicing type influence consumers’ decisions on both types of ham (to a much greater extent for fodder-fed ham). Conversely, the perceived quality cues linked to the production agrosystem of origin, with either written or pictorial information referencing the Dehesa, are only relevant for consumers’ preferences in the case of the acorn-fed ham, which is the type more clearly related to this agrosystem. It is also worth noting that we identify a certain quality differentiation failure, as some consumers seem to be making a trade-off between two objective quality features (namely, breed purity and ham type).

Notably, the results show that there is a high degree of heterogeneity among consumers’ preferences towards Iberian ham, particularly related to the production agrosystem of origin. Preferences are found to be significantly influenced by consumers’ knowledge about this agrosystem, use value of environmental and landscape services stemming from it, opinions on its cultural values and on the taste of its traditional products, and place of residence. Indeed, the results obtained for different consumer profiles established according to their awareness of the values attached to the Dehesa agrosystem show that those aware of such values report higher WTP for the acorn-fed Iberian ham and lower WTP for the fodder-fed type, while no such differences are found for the case of unaware consumers.

Overall, our findings point to some relevant implications for business management. To prevent product differentiation failures, producers should clearly inform consumers that the type of Iberian ham, defined according to the breed and management system, largely determines the objective quality. The intense preferences found for the objective quality cues in fodder-fed Iberian ham suggest potential gains for producers from increasing objective quality (especially by increasing breed purity and using hand-sliced ham). In addition, ham marketed with a production agrosystem of origin cue may shape consumers’ food consumption choices: they can opt to purchase a product that is not only linked to a specifical geographical origin but also to a semi-natural environment (with the environmental and sociocultural values it entails), thus increasing the value of the acorn-fed Iberian ham. This hints at the potential for using promotional campaigns and an appropriate package design incorporating written and pictorial information to build on the identity created for these food products by drawing consumers’ attention to values associated with the agrosystem of origin.

Finally, limitations of the research should be acknowledged, especially those that relate to the valuation exercise used. First, it is worth noting that the selection of pictures might have influenced consumers’ choices for aesthetics reasons. In this respect, further research should include a wider range of pictures, and questions related to the aesthetic valuation of the different packages and their links to the agricultural ecosystem. Additionally, if possible, future analyses could include real purchase settings, using package mock-ups (instead of images of package fronts) to obtain more precise estimates.

Ethical approval

Our institution does not normally require formal ethical review for certain activities provided the following criteria are met: The data is completely anonymous with no personal information being collected (record of consent). The data is not considered to be sensitive or confidential in nature The issues being researched are not likely to upset or disturb participants Vulnerable or dependant groups are not included There is no risk of possible disclosures or reporting obligations.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, R. Granado-Díaz, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Respondents were told that the back of the packages included the standard mandatory information (i.e. manufacturer, nutritional information, etc.).

References

- Aaker DA. 1991. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. Vol. 28. New York: The Free Press. p. 1.

- Becker T. 2000. Consumer perception of fresh meat quality: a framework for analysis. Br Food J. 102(3):158–176.

- BOE (Boletín Oficial del Estado). 2014. Real Decreto 4/2014, de 10 de enero, por el que se aprueba la norma de calidad para la carne, el jamón, la paleta y la caña de lomo ibérico. Madrid: Boletín Oficial del Estado.

- Bredahl L, Poulsen CS. 2002. Perceptions of pork and modern pig breeding among Danish consumers. Aarhus: MAAP Center.

- CAPDR (Consejería de Agricultura Pesca y Desarrollo Rural) 2017. Plan Director de las Dehesas de Andalucía. Sevilla: Consejería de Agricultura, Pesca y Desarrollo Rural.

- Clement J, Kristensen T, Grønhaug K. 2013. Understanding consumers' in-store visual perception: The influence of package design features on visual attention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 20(2):234–239.

- Díaz-Caro C, García-Torres S, Elghannam A, Tejerina D, Mesias FJ, Ortiz A. 2019. Is production system a relevant attribute in consumers' food preferences? The case of Iberian dry-cured ham in Spain. Meat Sci. 158:107908.

- Espejel J, Fandos C, Flavián C. 2007. Spanish air-cured ham with Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). J Inter Food Agribus Market. 19(4):5–30.

- Fandos C, Flavián C. 2006. Intrinsic and extrinsic quality attributes, loyalty and buying intention: an analysis for a PDO product. Br Food J. 108(8):646–662.

- Garavaglia C, Mariani P. 2017. How much do consumers value Protected Designation of Origin certifications? Estimates of willingness to pay for PDO dry-cured ham in Italy. Agribusiness. 33(3):403–423.

- García-Gudiño J, Blanco-Penedo I, Gispert M, Brun A, Perea J, Font-I-Furnols M. 2021. Understanding consumers' perceptions towards Iberian pig production and animal welfare. Meat Sci. 172:108317.

- Garrido P, Elbakidze M, Angelstam P, Plieninger T, Pulido F, Moreno G. 2017. Stakeholder perspectives of wood-pasture ecosystem services: a case study from Iberian dehesas. Land Use Policy. 60:324–333.

- Glitsch K. 2000. Consumer perceptions of fresh meat quality: cross‐national comparison. Br Food J. 102(3):177–194.

- Gracia A. 2014. Consumers’ preferences for a local food product: a real choice experiment. Empir Econ. 47(1):111–128.

- Granado-Díaz R, Gómez-Limón JA, Rodríguez-Entrena M, Villanueva AJ. 2020. Spatial analysis of demand for sparsely located ecosystem services using alternative index approaches. Euro Rev Agric Econ. 47(2):752–784.

- Grunert KG, Bredahl L, Brunsø K. 2004. Consumer perception of meat quality and implications for product development in the meat sector-a review. Meat Sci. 66(2):259–272.

- Grunert KG, Hieke S, Wills J. 2014. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy. 44:177–189.

- Hensher D, Hanley A, Rose JM, Greene WH. 2015. Applied choice analysis (2nd ed.). Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Issanchou S. 1996. Consumer expectations and perceptions of meat and meat product quality. Meat Sci. 43:5–19.

- Kallas Z, Varela E, Čandek-Potokar M, Pugliese C, Cerjak M, Tomažin U, Karolyi D, Aquilani C, Vitale M, Gil JM. 2019. Can innovations in traditional pork products help thriving EU untapped pig breeds? A non-hypothetical discrete choice experiment with hedonic evaluation. Meat Sci. 154:75–85.

- Krinsky I, Robb AL. 1986. On approximating the statistical properties of elasticities. Rev Econ Stat. 68(4):715–719.

- Krystallis A, Chryssochoidis G, Scholderer J. 2007. Consumer-perceived quality in 'traditional' food chains: the case of the Greek meat supply chain. Appetite. 48(1):54–68.

- Lancaster KJ. 1966. A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ. 74(2):132–157.

- Lancsar E, Louviere J. 2008. Conducting discrete choice experiments to Inform healthcare decision making: a user's guide. Pharmacoeconomics. 26(8):661–677.

- MAPA (Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación). 2019. Registro informativo de organismos independientes de control del ibérico (RIBER). [accessed 2020]. https://www.mapa.gob.es/app/riber/Publico/BuscadorProductosCertificados.aspx.

- Marreiros C, Ness M. 2009. A conceptual framework of consumer food choice behaviour. CEFAGE-UE Working Papers 2009_06. Evora: University of Evora, CEFAGE-UE.

- McFadden DL. 1974. Chapter 4, Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behaviour. In: Zarembka P, editor. Frontiers in econometrics. New York: Academic Press; p. 105–142.

- Mesías FJ, Gaspar P, Pulido ÁF, Escribano M, Pulido F. 2009. Consumers' preferences for Iberian dry-cured ham and the influence of mast feeding: An application of conjoint analysis in Spain . Meat Sci. 83(4):684–690.

- OJ (Official Journal of the European Union). 2012. Regulation (EU) N° 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs.

- Ramírez MR, Cava R. 2007. Effect of Iberian × Duroc genotype on dry-cured loin quality. Meat Sci. 76(2):333–341.

- Resano H, Sanjuán AI, Albisu LM. 2007. Consumers’ acceptability of cured ham in Spain and the influence of information. Food Qual Preference. 18(8):1064–1076.

- Resano H, Sanjuán AI, Albisu LM. 2009. Consumers’ acceptability and actual choice. An exploratory research on cured ham in Spain. Food Qual Preference. 20(5):391–398.

- Resano H, Sanjuán AI, Albisu LM. 2010. Combining stated and revealed preferences on typical food products: the case of dry-cured ham in Spain. J Agric Econ. 61(3):480–498.

- Rose J, Bain S, Bliemer MC. 2011. Experimental design strategies for stated preference studies dealing with non-market goods. In: Bennet J, editor. The international handbook on non-market environmental valuation. Cheltenham (UK): Edward Elgar Publishing; p. 273–299.

- Sahelices A, Mesías FJ, Escribano M, Gaspar P, Elghannam A. 2017. Are quality regulations displacing PDOs? A choice experiment study on Iberian meat products in Spain. Ital J Anim Sci. 16(1):9–13.

- Salazar-Ordóñez M, Rodríguez-Entrena M, Cabrera ER, Henseler J. 2018. Understanding product differentiation failures: The role of product knowledge and brand credence in olive oil markets. Food Qual Preference. 68:146–155.

- Salazar-Ordóñez M, Schuberth F, Cabrera ER, Arriaza M, Rodríguez-Entrena M. 2018. The effects of person-related and environmental factors on consumers' decision-making in agri-food markets: The case of olive oils. Food Res Int. 112:412–424.

- Shepherd R. 2011. Determinants of food choice and dietary change: Implications for nutrition education. In: Contento IR, editor. Linking research, theory and practice. Sudbury (MA): Jones and Bartlett; p. 30–58.

- Silva Pérez MR. 2010. La dehesa vista como paisaje cultural. Fisonomías, funcionalidades y dinámicas históricas. Ería: Revista Cuatrimestral de Geografía. 82:143–157.

- Train K. 2003. Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Underwood RL, Klein NM. 2002. Packaging as brand communication: Effects of product pictures on consumer responses to the package and brand. J Market Theory Prac. 10(4):58–68.

- Zeithaml VA. 1988. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J Market. 52(3):2–22.

Appendix A

The quality standards according to the feeding and management systems are: i) acorn-fed (‘de bellota’) ham, involving animals slaughtered after foraging for acorns, grass, herbs, aromatic plants, wild legumes and other natural resources from the Dehesa agrosystem, without external feed input; ii) mixed-fed (‘de cebo de campo’) ham, involving animals that, although fed with natural resources from the Dehesa or other pastures, are also fed with cereal- and legume-based feeds; and iii) fodder-fed (‘de cebo’) ham, involving animals entirely fed with commercial feed. The feeding pattern before slaughtering also determines the type of animal management, especially regarding the degree of livestock intensification of the pig farms. Acorn-fed pigs are managed on extensive farms, at least in the last stage (minimum 60 days), with limited stocking density depending on the wooded area of the Dehesa. The mixed-fed pigs are bred in extensive farms or in intensive outdoor farms with a minimum surface area per animal (100 m2). The fodder-fed pigs are managed only on intensive farms (a minimum of 2 m2 per animal). With regards to pig breed purity, the Regulation (BOE 2014) distinguishes between a genetic percentage of 100%, 75% or 50% Iberian breed, stipulating that the mother must be 100% Iberian as registered in the herd book. It is worth noting that there is usually a trade-off between weight and quality, with 100%-Iberian (50%-Iberian) showing the highest (lowest) quality but the lowest (highest) weight. Ultimately, the combination of the two factors gives rise to the final categories, ranging from the highest quality (acorn-fed 100% Iberian) to the lowest quality (fodder-fed 50% Iberian).

Figure A1. Categories of Iberian ham according to the Quality Standard regulation (BOE Citation2014). 1Source: Adapted from Spain Food Sherpas (2018) and ASICI (2020). The grey dotted lines show product alternatives that may be technically possible but are not market-oriented since there is no incentive for investing in breed purity when the end product would have lower meat yield (the Iberian breed is smaller) and the lowest quality (and, accordingly, the lowest price). In addition, it is worth noting that from a market perspective there is no clear incentive for having high-breed-purity Iberian pigs (100% or 75%) if they are not going to be used to produce the highest quality (black or red label).

Appendix B

Table B1. Descriptive statistics of the socio-demographic variables of the sample.