ABSTRACT

This paper examines patterns of posting behaviour on extremist online forums in order to empirically identify and define classes of highly active ‘super-posters'. Using a unique dataset of 8 far-right, 7 Salafi-jihadist, and 2 Incel forums, totalling 12,569,639 unique posts, the study operates a three-dimensional analysis of super-posters (Gini coefficient, Fisher-Jenks algorithm, network analysis) that sheds light on the type of influence at play in these online spaces. Our study shows that extremist forums consistently display four statistically distinguishable classes of posters from the least active ‘hypo-posters' to the most active ‘hyper-posters', as well as demonstrating that, while hyper-posters’ activity is remarkable, they are not necessarily the most central or connected members of extremist forums. These findings, which suggest that extremist forums are places where both minority and majority influences occur, not only advance our understanding of a key locus of online radicalisation; they also pave the way for sounder interventions to monitor and disrupt the phenomenon.

1. Introduction

Are discussions on online extremist forums driven by a small proportion of individuals, or are they akin to more egalitarian deliberative spaces? In other words, what type of influence is at play in these forums: that of a minority converting the masses or that of a majority whose views are so identical that they create compliance to shared norms? Is there even one single participation structure and dominant form of influence common to all extremist forums? As extremist online ecosystems – including those pertaining to Salafi-Jihadist, the far-right, and misogynistic ideologies – continue to grow apace and regularly underpin episodes of lethal violence, answering the question of the participation structure(s) of radical forums, and its (their) correlated type(s) of influence, has become critical for security and intelligence practitioners and scholars of terrorism alike. Even though a diverse set of digital platforms now host extremist content (read for example Baele, Brace, & Coan, Citation2020), forums remain a key locus for the construction of extremist communities, the dissemination of radical content, the organisation of harassment campaigns, and the radicalisation of violent extremists. The 2019 Christchurch mosques attack, to name but one prominent example of a global phenomenon, was announced and livestreamed on a forum in which the shooter was immersed, and which served as a launching platform for his manifesto.

Recent research has therefore sought to better understand extremist forums, particularly those belonging to the vast and expanding far-right online ecosystem. Over the last 20 years, this work (e.g. Burris, Smith, & Strahm, Citation2000) has analyzed dynamics such as general posting behaviour (e.g. Scrivens, Davies, & Frank, Citation2018), the evolution of positive and negative sentiments across time (e.g. Park, Beck, Fletcher, Lam, & Tsang, Citation2016), ideological shifts and developments (e.g. Holt, Freilich, & Chermak, Citation2020; Scrivens, Wojciechowski, & Frank, Citation2020), the relationships between different forums pertaining to the same ideological family (e.g. Baele, Brace, & Coan, Citation2021a), and the interplay between online and offline socialisation (Wojcieszak, Citation2010). As these studies multiplied, consistent but scattered evidence has emerged indicating a ‘super-posters' phenomenon, whereby a minority of extremely active contributors are responsible for a disproportionate number of the interactions, which suggests a preponderance of minority influence dynamics. More focused work has therefore been done over the past couple of years to highlight, characterise, and measure this super-poster phenomenon in various ways (e.g. Kleinberg, van der Vegt, and Gill Citation2021; Scrivens, Citation2020; Scrivens, Osuna, Chermak, Whitney, & Frank, Citation2021). These studies, reviewed below in more detail, largely confirmed the existence of this phenomenon but still suffered from a few non-negligible shortcomings. Chiefly, their empirical universe is limited to one, sometimes two forums, usually the same right-wing extremist ones. A large empirical investigation is therefore warranted at this point to test whether this evidence holds across the board, that is, for forums that are diverse in terms of their ideology, size, or language. Using extensive data extracted from 17 extremist forums from across the ideological, linguistic, and size spectrum (but also with different technical features), with 4 non-extremist forums with disparate focuses used as control cases, the present paper, therefore, aims to expand and consolidate existing research by taking up this specific task in a way that also sheds light on the type of influence – and hence radicalisation – at play in these spaces. To do so, we design a three-steps assessment interrogating the very nature, and hence definition, of super-posting: is super-posting a truly distinct behaviour in terms of posting quantity and centrality in forum discussions? Incidentally, do unequal posting activity distributions have anything to do with extremism, or are they a common feature of online communities?

Our study provides clear results that largely confirm existing evidence, with every single one of our diverse sets of extremist forums characterised by a small clique of extremely active posters who occupy central roles in discussions. Yet we also demonstrate, however, that mathematically speaking the users of all these forums should be categorised into four groups when it comes to posting quantity, not simply two groups of respectively low- versus high-posting activity, and that some less active posters also occupy central influential positions in discussions. These observations hold in a remarkably stable way across all forums in our dataset – even in our non-extremist control forums – suggesting not only that they are valid across ideologies, sizes, and languages, but also that they are not unique to extremist forums. These results not only convey important practical information for counter-extremism initiatives (for example allowing more efficient monitoring of certain users), but also shed light on the type of influence and hence radicalisation that takes place in these online spaces. Our findings, which constitute new empirical data for the longstanding research agenda on polarisation and radicalisation through political discussions, suggest that extremist forums are hierarchical echo-chambers wherein majority and minority influences combine.

We proceed in three main sections followed by a conclusion. First, we explain why investigating structures of posting behaviours matters when it comes to extremism, and we examine existing evidence under this light. Using Moscovici’s seminal distinction between minority and majority influence, and exploring the broader Social Psychology literature on compliance, conversion, and polarisation through political discussion, we construct two ideal-typical models of forum structure when it comes to posting, each with an associated form of dominant influence and radicalisation: the horizontal echo-chamber (majority influence) and the vertical indoctrination space (minority influence). On that basis, we review the existing evidence for the super-poster phenomenon, pointing to its achievements and limitations and explaining what these imply when it comes to considering extremist forums as corresponding to one or the other ideal-type. Second, we present our data (consisting of a large database of content and meta-data of 8 far-right, 7 Salafi-jihadist, and 2 Incel forums, totalling no less than 12,569,639 unique posts), and explain our three-dimensional quantitative methodology: the calculation of Gini coefficients to measure overall inequality of posting volume in each forum, the use of the Fisher-Jenks algorithm for identifying and delineating statistically distinct classes of posters, and the construction of a network of select forums’ posting interactions to further incorporate relational, social aspects of the phenomenon in a way that sheds light on influence dynamics. Third, we present our results and unpack their implications when it comes to dynamics of influence and polarisation.

2. Influence and radicalisation in extremist online forums

2.1. Two ideal-types of online influence and radicalisation

The polarising potential of group discussions between people sharing similar political views is well-known. Since Myer’s experimental evidence for deliberation-induced political polarisation (e.g. Myers & Kaplan, Citation1976; Myers & Lamm, Citation1975), studies have repeatedly replicated what Sunstein (Citation1999) has called the ‘law of group polarisation' through discussion between like-minded individuals (see Wojcieszak, Citation2011 for a review). These settings are fertile breeding grounds for extremism, provided certain beliefs (for example the idea that illegal actions are sometimes legitimate) are primed in discussion (Thomas, McGarty, & Louis, Citation2014), for example by individuals with a vested interest in radicalising the group. This particular mechanism of polarisation has been integrated within several models of radicalisation, for instance as the ‘group radicalisation in like-minded groups' in McCauley and Moskalenko’s (Citation2008) framework. Crucially, experimental evidence has now shown that such enclave settings can increase participants’ acceptance for violence as a solution to the problem being discussed (Andersen Citation2022).

Although some have warned against blaming the internet for extremism (O’Hara & Stevens, Citation2015), there is ample evidence that this logic holds online, as few experimental endeavours have demonstrated (e.g. Levey & Bouchard, Citation2019). Various online spaces without any existing offline grounding have triggered and pushed group polarisation to extreme levels, like the so-called ‘incelosphere' (Baele, Brace, & Coan, Citation2021b). Political forums and discussion groups without moderating practices actively ensuring a diversity of voices have been shown to polarise and radicalise people (e.g. Wojcieszak, Citation2010).

Yet what exactly is the driver of this radicalisation process? Using Moscovici’s seminal distinction (e.g. Moscovici and Faucheux Citation1972), we can imagine two main types of influence at play here: majority or minority influence, each involving different mechanisms. Traditionally, research on influence has been designed in ways that reveal influence by the majority on the minority, the paradigmatic example being perhaps Asch’s experiments on conformity (e.g. Asch Citation1951): research has exposed how individuals facing widely shared norms, consensual opinions, and standardised behaviours around them, tend to mimic and adopt these norms, opinions, and behaviours. Peer pressure and a need to belong push people to socialise in ways that follow this ‘normative influence'; compliance, that is, the ‘act of changing one’s behaviour to match the responses of others' (Cialdini & Goldstein, Citation2004, p. 606), is, therefore, the key mechanism at play in majority influence. Majority influence has been shown to play an important role in the circulation of prejudice, discrimination and radical views, with obvious evidence provided by tragic cases like Nazi Germany or the Rwandan genocide. For example, Cialdini and Goldstein (Citation2004, p.607) find an ‘almost perfect correlation between individuals’ likelihood of expressing or tolerating prejudice, and their perceptions of the extent to which most others approve of these behaviours' (our emphasis). Most of the numerous studies of group radicalisation through deliberation, like the ones evoked above, rest on horizontal patterns of discussion and thereby imply majority influence (e.g. Sunstein, Citation1999; Schkade, Sunstein, & Hastie, Citation2010; also Strandberg, Himmelroos, and Gronlund Citation2019); the very concepts of ‘echo chamber' and ‘enclaves', which are usually employed to characterise these settings, evoke spaces where one’s opinions simply reflect those of other participants.

Applied to extremist internet forums, this logic would suggest that members adopt radical views and norms if – and because – these are shared by most other posters and contribute to create a sense of common group identity. Edwards (Citation2013), for instance, suggests that forums’ ingroup homogeneity and shared identity is achieved without much steering work thanks to participants’ self-selection and their gradual attuning to the dominant ideas and norms. From this perspective, what triggers expressions of extremist ideas and behaviours is the perception that radical views are widely shared across peers. Theoretically, the ideal-typeFootnote1 of the ultimate form of such setting would thus be one where all members of a given extremist forum post equally, creating a perfect sense of what the majority thinks.

Yet at the other end of the theoretical spectrum another situation is also possible: one solely characterised by minority influence. Following Moscovici (e.g. Moscovici and Faucheux Citation1972; Moscovici, Citation1980; Moscovici & Mugny, Citation1983), research in social psychology has considered the effect of individuals’ exposure to consistent minority positions, where the effect is not normative and identity compliance but conversion, which has been shown to trigger deeper and longer-lasting shifts in beliefs and behaviours. This perspective suggests that another mechanism than the one involved in discussions between like-minded people is potentially at play on the internet just like offline: the ability of influential opinion leaders to pull and keep audiences into communities and spaces where their worldviews are consistently promoted. This top-down mechanism of influence is well documented, especially on social media. Cha and colleagues (Citation2010), among others, identified it on Twitter and showed how strongly influencing minorities invest in enhancing their reputation and traction within their specific domains, where they compete to be recognised as leading authorities. Soares, Recuero, and Zago (Citation2018) similarly characterise Twitter as a space where people are ‘looking for opinion leaders with similar views', with these leaders striving to gain and retain social capital through both Tweeting quality and quantity.

Translated to online forums, this approach would suggest that these could be places dominated by a very limited number of contributors who secure their status, and thereby influence over other users, by posting either a disproportionate number of posts or a significant number of high-quality ones. Ideal-typically, a forum characterised purely by minority influence would have a silent majority and a small vocal minority – perhaps even a single person – to which the majority listens and occasionally seeks advice.

Theoretically, two abstract ideal-types of internet forums can therefore be opposed (in terms of the type influence they host). On the one side is the horizontal echo-chamber, whose members post similar – or, in the most extreme scenario, equal – amounts and align their beliefs and identity to those of their peers through socialisation, without any one of these peers weighing more influence than another. On the other side is the vertical indoctrination space where the majority of members draw their beliefs and identity from a highly regarded vocal few – in its most exaggerated form, all but one member follow a single individual. We acknowledge that real, documented echo chambers are rarely fully horizontal nor are indoctrination spaces always purely vertical, but the twin concepts of horizontal echo-chamber and vertical indoctrination space are used here as abstract heuristic constructs allowing us in the following subsection to examine what the existing literature tells us about which one of the two hypothetical models extremist forums are closer to. Real forums, obviously, always fall somewhere in between these two abstractions; the empirical question is to locate exactly where.

2.2. Existing evidence

Considered together, existing studies of extremist forums across ideologies point to the existence of a pronounced super-poster phenomenon, and therefore suggest that these spaces are overwhelmingly characterised by minority influence with a structure coming close to the vertical indoctrination space.

In Citation2007, Awan noted that a very small minority of users were driving the discussion in the Salafist discussion board Mujahedon.net, with over 90% members rarely posting on the forum. A few years later, Ducol’s study of the French ‘Jihadosphere' observed that the pool of participants in the Ansar al-Haqq forum was ‘neither consistent nor homogeneous' but instead ‘clearly divided between a huge majority of passive users and a small minority of active members who are nevertheless extremely effective in maintaining the continuous flow of discussions and the dissemination of jihadi content' (Ducol, Citation2012, pp. 58–59). The same phenomenon was highlighted in Baele et al.’s (Citation2021b) research on the misogynistic forum Incels.me, where posting activity shows a somewhat exponential distribution culminating in a handful of hyperactive posters. In a similar vein, Shrestha, Kaati, and Cohen’s (Citation2017) analysis of jargon use in the Swedish far-right forum Flashback indicated the presence of ‘high-status members in the group who are very active in the community and influential in creating the jargon', whose linguistic practices are then copied by more peripheral members.

These depictions, which point to minority influence and quite closely correspond to the vertical indoctrination space ideal-type, interestingly echo studies of non-extremist thematic forums and online spaces more generally, which have not only noted the divide between a minority of ‘posters' and a majority of ‘lurkers' (Lai & Chen, Citation2014), but also revealed the presence of castes of influential super-posters. Graham and Wright’s (Citation2014) study of a money-saving forum showed, for example, that a minority of 0.4% ‘super-participants' contributed to almost 50% of the posts, Kies (Citation2010) measured that the 10 most frequent posters of the forum of the liberal Italian political party Radicali were responsible for over a quarter of its contributions, and Si and Liu (Citation2010) more precisely showed that the posting distribution of China’s biggest bulletin board (Tianya) followed a power law. Beyond forums, Jiang and colleagues’ (Citation2013) study of the ‘Celebrity Hall' board of the Sina microblogging platform revealed heavy-tailed power-law types of distributions of posting activity, and Sano and colleagues (Citation2013) showed that even the increase and subsequent decrease of activity in blogs when extraordinary events occur follow a power law distribution. High posting inequality therefore seems to be a normal pattern of activity in online community settings, not a feature of political extremism.

A second wave of more recent in-depth studies of the posting behaviour in some of the biggest far-right forums have further evidenced this pattern. Scrivens (Citation2020) analysis of 15 years of interactions in one sub-forum of Stormfront identified three sub-types of super-posters: high-intensity, high-frequency, and high-duration posters. Also scrutinising part of Stormfront, Kleinberg, van der Vegt, and Gill (Citation2021) used the Gini coefficient to calculate the inequality between posters in terms of contribution volume (0 representing perfect equality and 1 perfect inequality), finding an extremely unequal coefficient of 0.85 for the overall number of posts; their observations showed that ‘a mere 10% of users were responsible for more than 80% of the posts, and 20% of the users accounted for almost 90% of the posts' (Kleinberg et al., Citation2021, p. 16). Interestingly, they also calculated an even higher coefficient (0.90) for the number of ‘extremist posts' and observed that super-posters’ contributions were typically longer, negative, and more extremist than less active members, as well as noted that they tended to be longstanding contributors to the forum. Work on Iron March and Fascist Forge (Scrivens, Osuna, et al., Citation2021) additionally demonstrated that the ‘highly embedded users' minority, which is ‘driving the high posting activity in each forum', is mostly constituted by the forums’ ‘founding fathers'. These posters tend to post more extremist content (Scrivens, Wojciechowski, Freilich, Chermak, & Frank, Citation2021).

Together, these studies accredit the hypothesis of a super-poster effect in extremist forums, whereby conversation is driven by a small minority of more extremist, established contributors; they point to a critical role of minority influence and are thus more compatible to the abstract, ideal-typical conceptualisation of extremist forums as vertical indoctrination spaces, rather than as horizontal echo-chambers.

2.3. Aim of the study

Yet even though this accumulated evidence clearly converges, it still does not provide a solid test of the super-poster phenomenon and its implications for influence processes in extremist forums. This is for two main reasons.

On the one hand, the second wave of scholarship directly focusing on posting behaviour have a quite narrow empirical universe, that of Stormfront threads, Ironmarch and Fascist Forge. This creates three shortcomings. First, despite the sometimes large amount of posts making up these (sub)forums, an ideologically broader set of extremist forums needs to be investigated. Authors of these studies themselves warn that their findings only hold for the one or two forums they investigate; Kleinberg, van der Vegt and Gill (Citation2021, p. 17) for instance write that their ‘findings cannot be generalised to other forums or even other right-wing forums'. It is indeed plausible that different ideologies have different norms of interaction (one can for instance expect Salafi-Jihadist forums to be more hierarchical when they rely on theological authority), and the same holds for different languages corresponding to different cultures. Second, different forums have their own unique technical affordances, for example systems of titles and accolades that they bestow upon users. As an example, Stormfront users have their username, but some also have a ‘user title' such as ‘Enlightened Despot' as well as a ‘role' such as ‘forum member' and ‘Lifetime ‘Friend of Stormfront’ Sustaining Member' depending on their financial contribution to the website; likewise, Vanguard News Network has usernames, user types such as ‘administrator' and ‘senior member', as well as a ‘sign’ which consists of a quote (for example ‘Form follows function – Louis Sullivan’). As such, it would be reasonable to ask whether these accolades and titles, among other technical differences, have any impact on the overall posting behaviour of any given forum (for example creating a larger class of very active posters through reward with higher titles). Third, forums from a wide range of sizes ought to be included. Indeed varying feelings of community may be associated with smaller or bigger online spaces, with research crucially showing that group size has an impact on influence, especially conformity to majority norms and ideas (see Bond Citation2005 for a review). In sum, a study resting on a broader and more diverse empirical universe is required at this consolidation stage of the research agenda.

On the other hand, existing efforts have used a range of different methodological approaches and metrics to study posting behaviour, answering a series of research questions with pertinent tools. Even though such a diversity has shed light on the phenomenon from various directions, it remains incomplete. On the one hand, a clearer perspective would emerge from using a single multi-step methodology to study the broader empirical universe evoked above. This may involve systematically applying several particularly useful, complementary metrics tested with success. On the other hand, some highly pertinent methods for the study of posters’ categories and their influence have not been used yet, and could potentially alter the consensual view that extremist forums are characterised by a super-posters phenomenon.

The present paper seeks to correct these two shortcomings – which are normal at this stage of the collective research agenda – by consistently deploying a composite methodology across a wide empirical universe of extremist forums. By doing so, we put the converging yet scattered evidence to the test in a way that possibly redefines the nature and hence definition of super-posters. Indeed we aim to offer a more robust delineation of the super-posters category by comparing it to other potentially existing classes of posters, and seek to find out whether very active posters are necessarily characterised by increased influence, approximated by enhanced patterns of interaction in the forum, both together and with less active contributors. Incidentally, we also seek to find out whether the super-poster phenomenon is more salient in extremist forums compared to non-extremist ones.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Data

We obtained the Original Posts (OPs) and replies of 8 far-right forums, 2 Incel forums, and 7 Salafi-jihadist forums, for periods of time as extensive as technically possible. While this corpus does not represent the full population of online extremist forums, to our knowledge it nonetheless represents one of the largest and most representative samples ever assembled as a corpus containing meta-data for each post; the most notorious Incel, Islamist, and far-right forumss are included alongside lesser-known ones. The far-right and Incel forums were scraped by the authors,Footnote2 while the Islamist ones were selected from the repository assembled by the University of Arizona Artificial Intelligence Lab, to which full credit is due.Footnote3 Overall, this large corpus represents no less than 12,569,639 unique posts, with diversity in terms of forum sizes and intensity (from a forum averaging almost 500 posts per day to one barely reaching 6) as well as language (English, German, Arabic, French, Russian). Because its sheer size makes Stormfront impossible to fully scrape through standard means,Footnote4 only one subforum as representative as possible to the ideology (dedicated to ‘Politics and the Ongoing Crisis') was collected, with 18 years of posts gathered. below displays these and other descriptive metrics. This unique dataset is made openly available to the scholarly community upon demand to the authors.Footnote5

Table 1. Dataset (descriptive statistics).

3.2. Methods

We explore the super-poster phenomenon using a three-step process whereby each additional step builds on the previous one to provide finer-grained evidence.

3.2.1. Gini coefficient

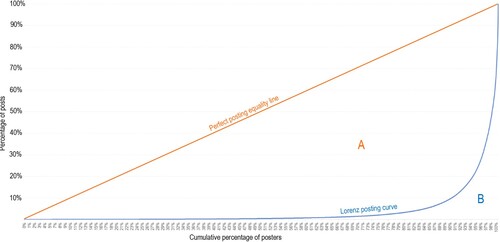

First, we applied a measurement of posting inequality in each forum to examine our main hypothesis. Following Kleinberg, van der Vegt and Gill (Citation2021), we used the Gini coefficient as a good exploratory summary measure of posting inequality. The Gini coefficient or index is a single measure of inequality for discrete and continuous distributions of values, usually income or wealth (see Dorfman, Citation1979; Gini, Citation1921). Applied to posting inequality, and with the example of the Rapture forum from our dataset provided in below, the Gini coefficient is equal to A/A + B, that is, the area between the line of perfect posting equality (orange) and the Lorenz posting curve (blue), expressed as a proportion of the total area below the perfect posting equality line (that is, between perfect posting equality and maximal inequality). Therefore, and as mentioned above, a forum obtaining a Gini score of 0 would be one where all posters contribute the exact same number of posts, while a Gini coefficient of 1 would indicate that a single poster has written all the posts of the forum; in the graph below, Rapture demonstrates a very high degree of posting inequality, with a Gini coefficient of 0.925. The first scenario would mean that the forum is a horizontal echo-chamber, and the second would indicate that it is a vertical indoctrination space where everyone is reading a single influential poster’s musings.

3.2.2. Fisher-Jenks algorithm

While this index allows for a rapid diagnosis and overview, it has a well-known shortcoming: similar and even identical scores can mask very different underlying distributions. For that reason, it is unfit for precisely identifying coherent classes of posters, which is a major problem when trying to offer a statistically robust delineation of the phenomenon. Our second step therefore plotted the full distribution of posts for all forums to observe potentially (dis)similar configurations of posting distributions. We used the Fisher-Jenks Natural Breaks Optimisation algorithm on each of these distributions to identify statistically coherent classes of posters. This algorithm classifies n observations into k distinct groups such that intra-group variance is minimised while inter-group variance is maximised (Hartigan, Citation1975; Jenks, Citation1977; Rey, Stephens, & Laura, Citation2017). Specifically, it is an iterative process that first involves the arbitrary grouping of data points into k groups; the sum of squared deviations from the mean is then calculated for each group, before moving one or more data points into different groups, and then re-calculating the sum of squared deviations within each of the groups, a process repeated until the within-group sum squared deviations reaches minimal value. The Fisher-Jenks algorithm is therefore an objective, mathematical way to determine how many categories of posters can be said to exist in extremist forums. Additional practical information about the application of the Fisher-Jenks algorithm to the forums’ data is available in Appendix 1.

3.2.3. Network analysis

Because this classification of posters did not convey information about their influence in the forums apart from an assumption that posting a lot means being very vocal, we conducted a network analysis of posting interactions in three different forums selected for their different characteristics: the one with the lowest inequality and a low posting intensity (a German Salafi-jihadist forum), the one with the highest inequality and an average intensity (a far-right forum in English), and the most intense forum with an average inequality (a French far-right forum). In our networks, the nodes represent posters (coloured depending on their Fisher-Jenks posting classes, and sized according to their degree score, that is the number of links with other nodes) and the edges (links) between two nodes represent instances where they have posted in the same thread – the thickness of the edge reflects the amount of times this co-posting has taken place.Footnote6 In other words, the networks document direct interactions between posters, disclosing not only how much individuals post but also with whom they engage, which offers a granular analysis of influence. Hypothetically indeed, a very active poster could well only contribute to a single thread with a very limited number of participants, or on the contrary directly discuss with all other participants across all threads of the forum.

Two measures are provided that together characterise posters’ position in their forums: we provide a ranking of both the most central posters (betweenness centrality) and the most connected ones (degree). These two measures are traditionally understood in social network analysis to be proxy measures of influence; for example, betweenness centrality is a standard measure used to ‘capture a person’s role in allowing information to pass from one part of the network to the other' (Golbeck, Citation2015, p. 224). While degree and centrality scores are good proxies for influence, there are more qualitative dimensions of influence that arguably escape these measurements. For example, a poster with lower centrality and degree might nonetheless be highly influent if he/she occupies a strategic place that bridges separate communities in a fragmented network (on the ‘strength of weak ties’, see Granovetter, Citation1973; for an updated discussion see Aral Citation2016). We consider these possibilities in our discussion of the network graphs.

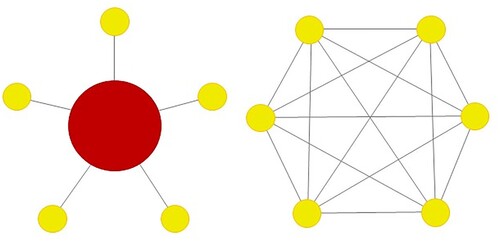

below represents in a network way the most extreme versions of our vertical indoctrination space and horizontal echo-chamber ideal-types, using the hypothetical scenario of a forum populated by six members. For the vertical indoctrination space (left), a single poster is connected to all other posters, each only connected to him/her. As a result, he/she occupies the centre of a ‘star' network in which he/she enjoys maximal (minority) influence (maximal degree score, perfect centrality). In the opposite case of the horizontal echo-chamber (right), a ‘mesh’ network signals equally distributed influence: each poster is equally connected to all the other members (equal degree scores), leading to a situation where no-one occupies a position of centrality. Such a granular approach stressing the properly social dimension of super-posting extends and complements the two previous steps which – like the existing literature – concentrate on individual forum members’ posting quantity, thereby offering a more direct evaluation of whether or not the most vocal posters necessarily possess the most influence. Additional practical information about the construction of the networks is available in Appendix 2, with key metrics.

Figure 2. Network representation of the two opposing ideal-types of extremist forums, in their most extreme forms: vertical indoctrination space with pure minority influence (left) and horizontal echo-chamber with pure majority influence (right).

Before moving to the empirical section, a caveat is in order. Even though this three-step method offers a robust depiction and analysis of posting behaviours in extremist forums, disclosing clear results pointing to specific types of influence, its zoomed-out nature and lack of attention to linguistic content means that its measurement of influence is not fully comprehensive (e.g. how posters acquiesce to claims, mimic lingo, forward memes).Footnote7 Given the conclusions of the literature reviewed above, however, we are confident that our method adequately evaluates influence in enclave settings like extremist forums; to further evidence this, we provide a few excerpts from forums to illustrate the types of dialogues represented by the links of the network analysis.

4. Is there a super-posters phenomenon – and what is it?

4.1. Gini scores: overall posting inequality

As shows, extremist forums are indeed characterised by extremely high posting inequality. Without exception, all the forums in our corpus obtain a Gini coefficient above 0.8, which indicates that they are all spaces dominated by a tiny yet very vocal minority. Four forums even score higher than 0.9, and the average coefficient is no less than 0.874. There is very little variation: with a standard deviation of only 0.037, not only are all forums highly unequal but also very similar in terms of the intensity of this inequality. However, this inequality cannot be understood as a feature of extremism: all our non-extremist control forums exhibit the same behaviour, with an almost identical average Gini score (0.843). These measurements are not compatible with a conceptualisation of extremist forums as horizontal echo-chambers where participants discuss together as peers; it is hard to imagine a process of socialisation where the everyone’s views and practices are equally influential. Rather, these numbers accredit the understanding of these forums as places dominated by a minority of posters as in the vertical indoctrination space ideal-type.

Table 2. Gini coefficients for extremist and control forums.

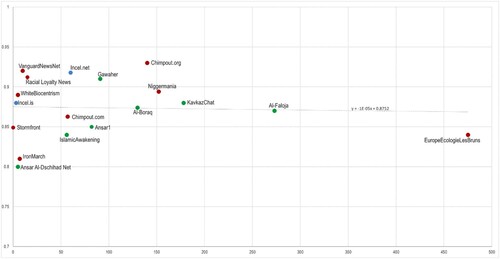

plots these coefficients with forums’ median number of posts,Footnote8 with forums displayed as dots of various colours representing their ideological families. The graph shows several things. First, the almost flat trendline indicates that forum popularity (approximated by medians) has no impact on inequality. Forums with a lot of posting activity obtain comparable scores with forums with very little activity, suggesting that the same structure of influence is at play regardless of size. Second, neither ideology nor language, nor varying technical affordances, appear to fluctuate Gini coefficients: there is no indication that a particular ideology or a specific way of rewarding active membership, for example, are associated with more equalitarian patterns of exchange.

4.2. Fisher-Jenks algorithm: super-posters and other classes of posters

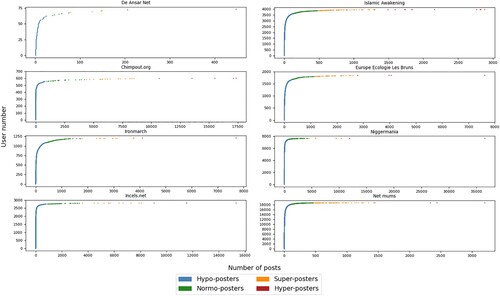

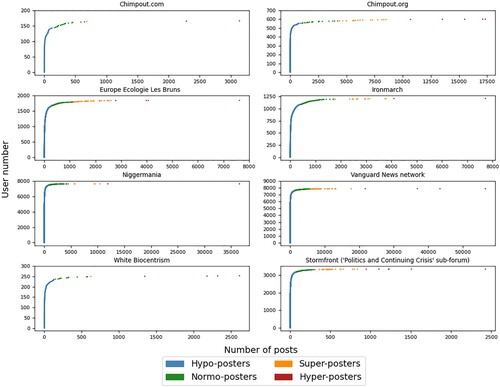

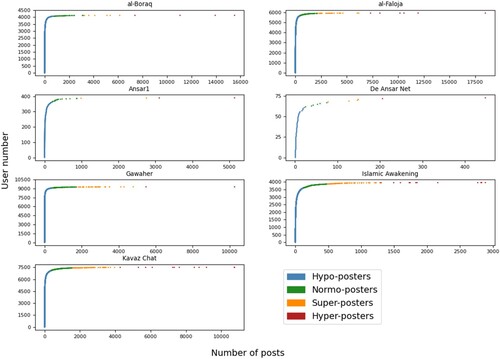

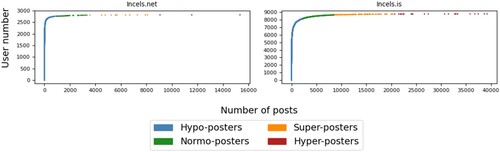

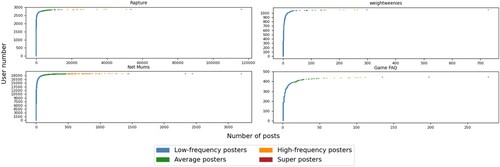

The following displays the distribution of posting inequality for a selection of our forums (the graphs for all forums are available in Appendix 3); in these graphs, individual datapoints represent forum users, who are categorised into one of the statistically distinct groups (represented by different colours) based upon the number of posts they made to their respective forum. The exact number of these groups, and the assignment of each user to one of them, was indicated by the Fisher-Jenks Natural Breaks Optmization algorithm, which as explained in the methods section is an iterative process that seeks to place data points in groups in a manner that minimises intra-group variation while maximising inter-group variation. Plotting all forums’ posting distributions and running the algorithm on them disclosed very clearly two major interconnected findings that together force us to re-define the ‘super-poster' phenomenon in a way that somewhat alters the consensus that extremist forums are populated by only two classes of participants. Based on these findings, we propose a more statistically robust and coherent typology of posters that better corresponds to the reality of the structure of posting within these forums, and within which super-posting is best situated.

First, posting in all the forums follows a power-type curve where the most active members occupy the extreme end of a continuum. We knew from the Gini coefficients that the distribution would not be a flat line reflecting perfect equality; but our plots show that the distribution follows neither a linear curve, where increase in posting evenly augments, nor a step function where the behaviour of the minority of top posters is a sharp step-up from all other contributors. Between these two possibilities, our graphs demonstrate that it is simplistic to sharply distinguish, in a binary way, a minority of super-posters from a silent majority. In all forums, there are active – at times very productive – posters who clearly do not belong to the few contributors flooding the chat with their prolific prose. That a power law type of distribution is found in every single one of the forums of our dataset is a major finding for two reasons. On the one hand, it means that size, ideology, language, or diverse technical affordances do not affect the distribution of posting activity in extremist forums. On the other hand, the fact that it is also found in the non-extremist control forums means that this distribution is not unique to extremist (or even political) forums and cannot therefore be attributed to extremism (for example due to a correlation between extremism and preference for hierarchical structures); our findings therefore echo and expand the abovementioned literature documenting the commonality of power-law distributions of activity in online communities (Jiang, Zhang, Wang, & Li, Citation2013; Sano, Yamada, Watanabe, Takayasu, & Takayasu, Citation2013; Si & Liu, Citation2010).

Second and related to that, the Fisher-Jenks algorithm consistently identifies four relevant classes of posters, not two – remarkably, this result is obtained in every single forum of the dataset, clearly evidencing that they share a common posting structure. In line with this statistical evidence, we suggest abandoning the dual distinction between super-posters and the rest, and instead adopting a typology of four classes of posters. The typology adopts the standard use of prefixes when it comes to increasing quantities: hypo-, normo-, super-, hyper-. Members of the least active class of hypo-posters (blue on our graphs) are characterised by very few (often just 1 or 2) posts but make the majority of the total population of users on a forum. Normo-posters are much more active than the first group yet are not as engaged in the forum in a sustained way; the number of posts that individuals in that class (green) produce varies between forums depending on their userbase size and post corpus. The top two categories contain very active members. Super-posters (yellow) are significantly fewer yet also much more active than the preceding group; depending on the forum size and corpus, they are sometimes responsible for several hundreds or thousands of posts, playing a key part in a forum’s content. Finally, at the very top, are a handful of Hyper-posters (red) whose extremely active posting behaviour distinguishes them from the rest.

Crucially, all the strikingly similar curves yield identical results when the Fisher-Jenks algorithm is applied, indicating that this typology is found regardless of forums’ size and ideology, and evidencing a single pattern of posting behaviour distribution. It also demonstrates that the forums’ technical affordances such as user accolades and titles do not have an impact on overall posting behaviours. This common pattern is even found in all four control forums, indicating that these power-law distributions and categories of posters have nothing to do with extremism.

Even if it shifts the usual definition of super-posters towards a second-highest category, our new typology has two major advantages against the previous endeavours. First, four classes are a better empirical fit than two. Second and more crucially, even though it is important to acknowledge the existence of an elite caste of posters, it is equally crucial to consider a – sometimes large – class of very active posters because it nuances the impression (that dominates the literature and that exploratory measures like the Gini can give) that extremist forums correspond very closely to the vertical indoctrination space ideal-type. While data confirms the idea that there is a silent majority and a very vocal minority, it also blurs the line between the majority and minority, meaning that at least some dose of majority influence is at play in the large extremist spaces where normo- and super-posters count in the hundreds or thousands and do contribute sometimes sizably to discussions. Such a reality demonstrates a more diffuse form of influence, away from a purely top-down model of radicalisation where less active members – among them newcomers – are simply the recipients of one or a select group of elite posters’ extremist prose.

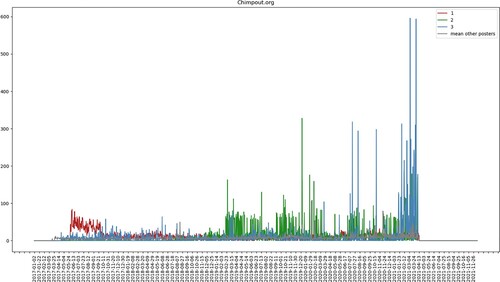

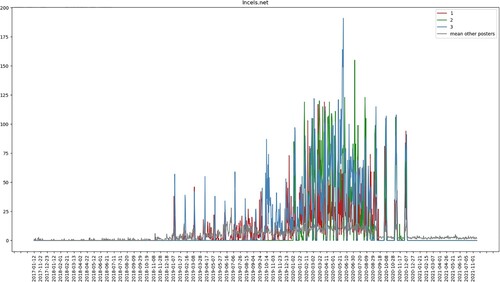

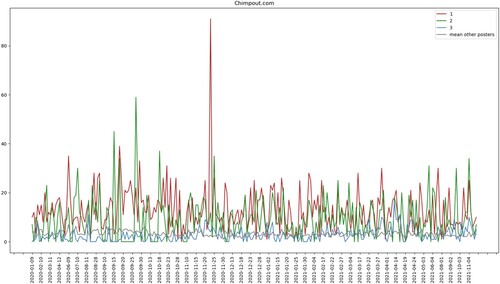

Before this claim is unpacked with more depth in the last empirical subsection, we need to pause to raise the question – already explored by Scrivens et al. (Citation2018) and Scrivens, Osuna, et al. (Citation2021) – of the frequency of active posters’ contributions: what if our aggregate, synchronous distribution of posts was artificially lumping together posters who posted in different periods of time through the history of the forums? Do very active posters have an intense interaction with a forum over a short period of time, or is their high post count the result of high, average, or even low-levels of intervention occurring over a prolonged period? To check this possibility, we plotted the daily posting activity of the most active posters against that of the general population in our forums, and this comparison revealed no clear pattern fragilizing our typology (see Appendix 3 for the full technical explanation and a selection of graphs). While a few forums do have some hyper-posters who are only (extremely) active within a certain time period (for example chimpout.org), in many forums hyper-posters have steady contributions across time (with occasional spikes) that follow the average posting activity.

4.3. Networks: hyper-posters’ influence

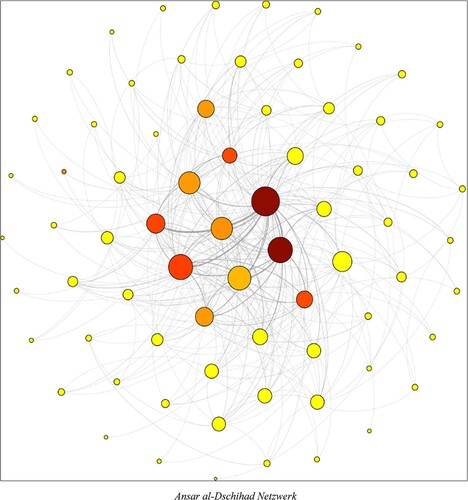

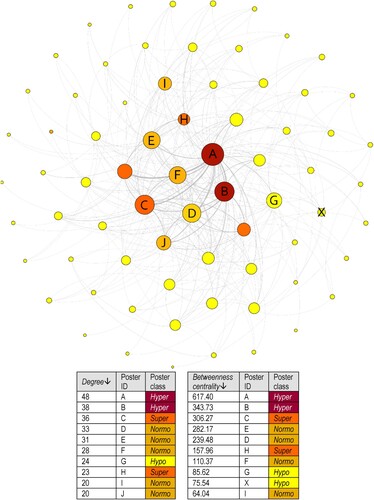

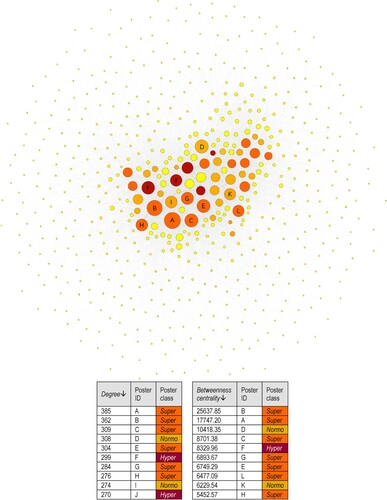

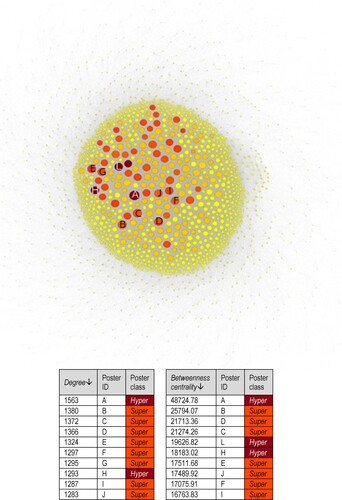

The last step of our analysis moves beyond simple posting counts to determine more fully the nature of super- and hyper-posting understood as properly social behaviours and hence approximate in a more direct way dynamics of influence at play in the extremist forums. (available in high-definition full-page size in Appendix 2) visualise our network analysis of posting interactions in three extremist forums from our dataset, and offer two main observations that extend our previous findings. These graphs ought to be compared with above representing the two abstract ideal-types of extremist forums.

Figure 5. Network and top-10 degree and betweenness centrality rankings for the forum with the lowest inequality and low activity: Ansar al-Dschihad Netzwerk.

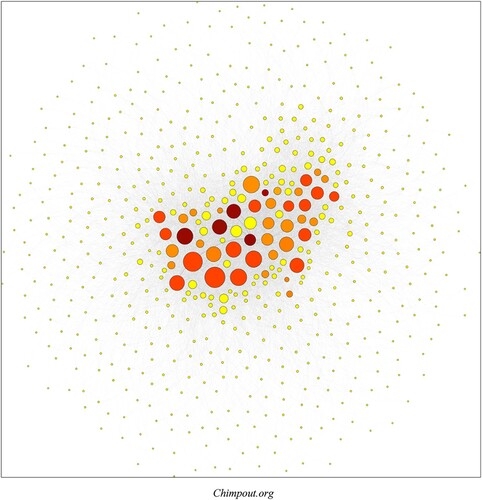

Figure 6. Network and top-10 degree and betweenness centrality rankings for the forum with the highest inequality and average activity: Chimpout.org.

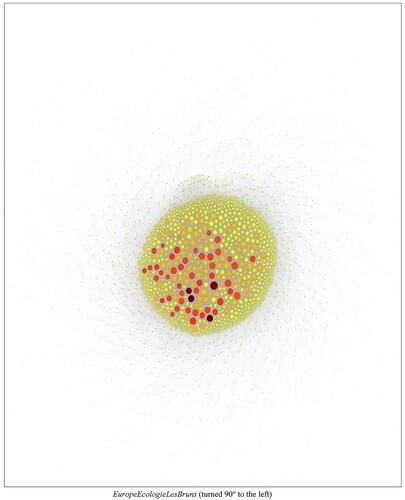

Figure 7. Network and top-10 degree and betweenness centrality rankings for the most active forum with average inequality: EuropeEcologieLesBruns

First, and in line with the minority influence ideal-type, hyper-posters occupy positions of authority in the networks, as evidenced by two important features: they are all centrally positioned, and have all high degree scores (as evidenced by the number and thickness of their links, and as reflected in their sizes). In other words, hyper-posters are unavoidable forum members, they engage with – or are engaged by – a majority of other posters in the forums. A qualitative exploration of the actual interactions represented by the network edges documents why they do indicate minority influence taking place in various ways such as lower posting members directly echoing, repeating or validating a hyper-poster’s claim, hyper-posters acquiescing to a suggestion made by a lower-posting member and encouraging them to express more extremist ideas, or hyper-posters welcoming new posters. Consider the four examples of interactions from Chimpout.org provided in Appendix 4; these quotes have been separated from the main text because of their highly offensive character.Footnote9 In examples 1 and 2, a super-poster (E in the corresponding network above) consistently recognises the validity of a hyper-poster’s (F) ‘analyses', and example 3 documents that same hyper-poster (F) welcoming a new poster and encouraging him to express extremist views. These are just three of thousands of similar interactions on the forum, illustrating our suggestion that edges in the network do not simply represent joint posting in a thread but also radicalising interactions where validation is given/sought and status is achieved.

Importantly, hyper-posters are also highly connected, denoting a clique effect where they validate each other’s positions, thus consolidating the community’s ideology. As such, rather than competing for influence on the community structured around them, they tend to interact in ways that consolidate each other’s status and together establish the groups’ norms, practices, and ideas (consider for instance example 4 in Appendix 4, between hyper-posters J and F).

The numbers indicating this influence position of hyper-posters are remarkable. For example, (hyper-) poster A of EuropeEcologieLesBruns is connected to no less than ∼85% of all forum participants (1563 nodes out of 1827), and (hyper-) poster A of Ansar al-Dschihad Netzwerk appears in threads with ∼68% of posters (48 out of 71). While these are particularly salient examples, no hyper-poster in our networks fails to score very high in both degree and centrality rankings. In other words, the hyper-posting behaviour is not solely about posting a lot, it is also defined by posting to/with everyone and becoming ubiquitous in the discussion dynamics – a more direct approximation of influence. Contrastingly, and in line what one would expect from the existing literature and the previous sections, hypo-posters tend to be scattered at the periphery of the network, engaging in one or a handful of threads only. Note that none of these networks are scattered into several communities; they are not fragmented and do not contain several centres, which denotes the uniformity of the online community these forums host and – because of the mutual backing highlighted above – further accentuates the influence of the hyper-posters clique that occupies the core of the community. This means that the type of influence associated with strategic positions other than centrality, like weak link connection, is not very present in these forums. Put differently, the networks at hand resemble the graph of the vertical indoctrination space ideal-type (albeit with a clique of several posters at the centre) much more than the one representing the horizontal echo-chamber (see ): highly unequal degree scores and centrality denote big differences in terms of posters’ influence.

Second, however, hyper-posters are not the only ones who enjoy very high centrality and connectivity; echoing the posting distribution and Fisher-Jenks findings, these metrics encourage us again to more accurately and productively recognise a continuum rather than a clear gap between hyper-posters and the rest on these metrics. In other words, the network analysis further supports both our distribution analysis and our new typology, demonstrating in another way the need to move from a ‘super/hyper-posters' vs ‘rest' approach. While all hyper-posters are indeed very central and connected, some super-posters – and in some cases even some normo-posters – appear to be very central too and can have very high degree scores that even surpass hyper-posters’, meaning they potentially achieve significant influence despite posting less. A qualitative analysis of this type of posters’ contributions would need to be conducted to determine if this is indeed the case, and if yes how this is achieved – through fewer but longer ‘quality' posts, for example.

The importance of members other than hyper-posters is especially true for larger forums like the ones represented in and , where some of the most central and connected nodes do not correspond to hyper-posters. As our figures show, for both these and similar forums the top-10 of nodes with the highest degree and centrality scores contains several super-posters (and even sometimes normo-posters) at higher ranks than hyper-posters. This finding further emphasises the need to understand hyper-posting as the top-end of a continuum, with less visibly ‘loud' yet as central and well-connected classes of posters below them.Footnote10 In this sense, while this analysis showed that the networks of extremist forums resemble that of the vertical indoctrination space, it also indicated that they do not correspond to the pure ideal-type but also contain features of the horizontal echo-chamber, at least for forums above a certain size where differences in degree and centrality scores between classes of posters become less pronounced. In sum, extremist forums are best conceptualised as a mix of both: hierarchical echo-chambers where complementary and intertwining minority and majority influences characterise interactions. As such, they are places whose extremist ideas, norms, and practices are established and reinforced not only by the interactions between high-posting and low-posting members but also by those uniting the high-posting clique.

5. Conclusions

Scattered evidence has repeatedly been pointing at a ‘super-posters' phenomenon in extremist forums – which remain prominent places of radicalisation at the age of social media – suggesting that these settings are vertical indoctrination spaces where minority influence is at play. This paper sought to provide a broad and systematic evaluation of this evidence, checking whether existing observations of this phenomenon effect hold across a wide range of different cases. Using three different types of measurement – Gini coefficients, the Fisher-Jenks algorithm applied to posting distributions, and network analysis, our work revealed striking similarities in terms of posting inequality distribution and interaction structures across all forums from our dataset, regardless of ideology or language. While all are topped by a small clique of extremely productive contributors (a feature not specific to extremist forums), it is more accurate to consider these forums to be populated by four – not two – classes of posters, whose increasing levels of participation follow a power or exponential type of curve, and whose authority in actual online interactions is often at odds with the sheer quantity of their contributions. These findings somewhat temper the conceptualisation of forums as purely vertical indoctrination spaces, demonstrating that dynamics of majority influence are also at play, especially as forums become more popular. Our inclusion of non-extremist forums as controls also clearly showed that this structure of posting is not a specific feature of extremist forums (and is therefore not due to their extremist nature), but is rather common in online discussion spaces.

These results do not only hold theoretical or more broadly scientific significance; they also provide actionable intelligence for non-academic stakeholders involved in monitoring/intervening in radical online spaces. Indeed a more fine-grained categorical structure of user behaviour on these forums, together with an identification of the centrality and connections of particularly active users, will allow for more focused intervention measures such as targeted undercover posting strategies (selectively aiming at discrediting influential posters, or creating an alternative influential node promoting less extreme views) or better allocation of scarce resources for intelligence investigations of specific users. More generally, clear maps of interactions and influence in extremist forums are necessary tools for evidence-based understanding of their dynamics and sound engagement with them.

Further work is needed, however, to expand the scope of the present study and alleviate its shortcomings. Two main lines of work stand out in particular. Although they still are crucial nodes in radical online ecosystems, forums are now accompanied by a variety of other types of online platforms whose own structures and logics of interaction and influence ought to be better understood. An emerging literature has started to mine and analyze extremists’ use of ‘alt-tech' platforms such as Telegram or Gab (e.g. Urman & Katz, Citation2022 on Telegram; Jasser, McSwiney, Pertwee, & Zannettou, Citation2021 on Gab), providing useful insights on several communities or accounts that would gain in being compared and contrasted in a systematic way. Second, another way to approximate influence in forums is by evaluating whether individual participants’ ideas, claims and concepts are approved or even picked up by other posters. Such a language-based analysis, which has been initiated by a couple of the abovementioned studies suggesting that more active members post more extreme prose (e.g. Scrivens, Osuna, et al., Citation2021), would benefit from being systematically carried out with a broad range of forums and pertinent indicators (e.g. are hyper-posters’ linguistic innovations adopted by other members, are their posts explicitly referred to as of high quality).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As Watkins sums up (Citation1952, 24), ideal-types are ‘heuristic aids which […] throw into relief real-world deviations from themselves’. Ideal-types thus constitute heuristic abstractions epitomizing a specific universe of cases, offering a theoretical point of departure for empirical work and further theoretical development (Doty & Glick, Citation1994).

2 This was done using custom-built web scrapers developed by the researchers in the Python generic programming language. These web scrapers used the Selenium package (https://selenium-python.readthedocs.io/) in order to interact with the website and simulate a web browser, and the Beautifulsoup package (https://pypi.org/project/beautifulsoup4/) to extract the relevant text from the HTML code. The data cleaning, pre-processing, and most of the analysis was then also carried out in Python, using packages such as Pandas (https://pandas.pydata.org/), NLTK (https://www.nltk.org/), and matplotlib (https://matplotlib.org/). All the code used to collect, clean, and analyse this data can be found at [GitHub Repository redacted for peer-review].

3 We are grateful to Andrew Park for his assistance. While the Arizona repository contains more Islamist forums, we only selected the ones which hosted, in a clear and unambiguous way, extremist discussions (as characterised by three criteria in a consistent way: (1) Manichean, exclusive categorization of the ingroup and the outgroups, (2) derogatory labels attributed to the outgroup and laudatory ones to the ingroup, and (3) endorsements of violence) as opposed to merely fundamentalist religious views. Random posts from each of the relevant forums hosted on the Arizona repository were read and screened according to these three criteria, resulting in 7 forums being selected.

4 Stormfront is incommensurable with other forums in terms of size, containing content that traces back to the mid-1990s.

5 While a recent decision by a US appeals court established that scraping public information is legal (see Richard, Citation2022), scraping extremist websites does raise a range of significant security and ethical issues; we direct the reader to the existing field-specific guidelines that informed the present study (e.g., Martin & Christin, Citation2016; Baele, Lewis, Hoeffler, Sterck, & Slingeneyer, Citation2018; Conway, Citation2021; Brewer, Westlake, Hart, & Arauza, Citation2021).

6 There are other ways to construct networks representing forum interactions, each with its advantages and problems. An alternative method counts the number of times someone posts right after another other, but while this method better integrates the idea of a discussion thread it fails to account for the fact that people who post after somebody else may not react to him/her but rather to the OP. Another method distinguishes between OPs and replies and counts all replies as such (as posts that only reply to the OP, and not to the posts that precede them), but even though this method reflects the important practice of Original Posting it is inadequate for boards with long threads wherein the OP only launched a discussion.

7 For detailed qualitative studies of this type of interactions, including their visual dimension, see for example Åkerlund (Citation2021), Askanius (Citation2021), or McSwiney and colleagues (Citation2021).

8 We opted for the median score as the least imperfect measure of forums’ activity. The mean and mode scores displayed in evidence the fact that extremist forums are rarely stable online spaces, but rather experience spikes and lows in terms of posting activity.

9 This decision is based on ongoing discussions on scientific ‘amplification’ of extremist content [for an initial discussion, see Askanius (Citation2021, p. 151)].

10 We suggest that this finding echoes emerging claims that offline violence is not necessarily carried out by the most enthusiastic participants to forums (Scrivens, Wojciechowski, Freilich, Chermak, and Frank, Citation2021).

References

- Åkerlund, M. (2021). Dog whistling far-right code words: The case of ‘culture enricher’ on the Swedish web. Information, Communication & Society. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2021.1889639

- Andersen, S. (2022). Accepting violence? A laboratory experiment of the violent consequences of deliberation in politically aggrieved enclaves. Terrorism and Political Violence. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/09546553.2022.2076600.

- Aral, S. (2016). The future of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 121(6), 1931–1939.

- Asch, S. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups, leadership and men (pp. 177–190). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Press.

- Askanius T. (2021) On frogs, monkeys, and execution memes: Exploring the humor-hate nexus at the intersection of neo-nazi and alt-right movements in Sweden. Television & New Media 22(2): 147-165.

- Awan, A. (2007). Radicalization on the internet? The virtual propagation of Jihadist media and its effects. RUSI Journal, 152(3), 76–81.

- Baele, S., Brace, L., & Coan, T. (2020). Uncovering the far-right online ecosystem. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2020.1862895.

- Baele, S., Brace, L., & Coan, T. (2021a). Variations on a theme? Comparing 4chan, 8kun, and other chans’ far-right “/pol” boards. Perspectives on Terrorism, 15(1), 65–80.

- Baele, S., Brace, L., & Coan, T. (2021b). From “incel” to “saint”: analyzing the violent worldview behind the 2018 toronto attack. Terrorism & Political Violence, 33(8), 1667–1691.

- Baele, S., Lewis, D., Hoeffler, A., Sterck, O., & Slingeneyer, T. (2018). The ethics of security research: An ethics framework for contemporary security studies. International Studies Perspectives, 19(2), 105–127.

- Bond, R. (2005). Group size and conformity. Group processes and intergroup relations, 8, 331–354.

- Brewer, R., Westlake, B., Hart, T., & Arauza, O. (2021). The ethics of web crawling and web scraping in cybercrime research: Navigating issues of consent, privacy, and other potential harms associated with automated data collection. In A. Lavorgna & T. Holt (Eds.), Researching cybercrimes. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burris, V., Smith, E., & Strahm, A. (2000). White supremacist networks on the internet. Sociological Focus, 33(2), 215–235.

- Cha, M., Haddadi, H., Benevenuto, F., & Gummadi, K. (2010). Measuring User Influence on Twitter: The Million Follower Fallacy. Proceedings of the Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

- Cialdini, R., & Goldstein, N. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591–621.

- Conway, M. (2021). Online extremism and terrorism research ethics: Researcher safety, informed consent, and the need for tailored guidelines. Terrorism and Political Violence, 33(2), 367–380.

- Dorfman, R. (1979). A formula for the gini coefficient. Review of Economics and Statistics, 61(1), 146–149.

- Doty, D., & Glick, W. (1994). Typologies as a unique form of theory building: Toward improved understanding and modeling. Academy of Management Review, 19(2), 230–251.

- Ducol, B. (2012). Uncovering the French-speaking Jihadisphere: An exploratory analysis. Media, War & Conflict, 5(1), 51–70.

- Edwards, A. (2013). (How) do participants in online discussion forums create ‘echo chambers’? Journal of Argumentation in Context, 2(1), 127–150.

- Gini, C. (1921). Measurement of inequality of incomes. The Economic Journal, 31(121), 124–126.

- Golbeck, J. (2015). Introduction to social media investigation. A hands-on approach. New York: Elsevier-Syngress.

- Graham, T., & Wright, S. (2014). Discursive equality and everyday talk online: The impact of “superparticipants”. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19, 625–642.

- Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360–1380.

- Hartigan, J. (1975). Clustering algorithms. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Holt, T., Freilich, J., & Chermak, S. (2020). Examining the online expression of ideology among far-right extremist forum users. Terrorism & Political Violence, Online Before Print.

- Jasser, G., McSwiney, J., Pertwee, E., & Zannettou, S. (2021). Welcome to the #GabFam’: Far-right virtual community on gab. New Media & Society, Online Before Print.

- Jenks, G. (1977). Optimal data classification for choroplethic maps. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas. Department of Geography (Occasional Paper No. 2).

- Jiang, Z., Zhang, Y., Wang, H., & Li, P. (2013). Understanding human dynamics in microblog posting activities. Journal of Statistical Mechanics, 10(2), 1–12.

- Kies, R. (2010). Promises and limits of web-deliberation. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

- Kleinberg, B., van der Vegt, I., & Gill, P. (2021). The temporal evolution of a far-right forum. Journal of Computational Social Science, 4, 1–23.

- Lai, H.-M., & Chen, T. T. (2014). Knowledge sharing in interest online communities: A comparison of posters and lurkers. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 295–306.

- Levey, P., & Bouchard, M. (2019). The emergence of violent narratives in the life-course trajectories of online forum participants. JQCJC, 6, 3.

- Martin, J., & Christin, N. (2016). Ethics in cryptomarket research. International Journal of Drug Policy, 35, 84–91.

- McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2008). Mechanisms of political radicalization: Pathways toward terrorism. Terrorism & Political Violence, 20(3), 415–433.

- McSwiney, J., Vaughan, M., Heft, A., & Hoffmann, M. (2021). Sharing the hate? Memes and transnationality in the far right’s digital visual culture. Information, Communication & Society, 24(16), 2502–2521.

- Moscovici. (1980). Toward a theory of conversion behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 13(1), 209–239.

- Moscovici, S., & Faucheux, C. (1972). Social influence, conformity bias, and the study of active minorities. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 6, 149–202.

- Moscovici, S., & Mugny, G. (1983). Minority influence. In P. Paulus (Ed.), Basic group processes. Springer series in social psychology (pp. 41–64). New York: Springer.

- Myers, D., & Kaplan, M. (1976). Group-Induced polarization in simulated juries. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 2(1), 63–66.

- Myers, D., & Lamm, H. (1975). The polarizing effect of group discussion. American Scientist, 63(3), 297–303.

- O’Hara, K., & Stevens, D. (2015). Echo chambers and online radicalism: Assessing the internet’s complicity in violent extremism. Policy & Internet, 7(4), 401–422.

- Park, A., Beck, B., Fletcher, D., Lam, P., & Tsang, H. (2016). Temporal Analysis of Radical Dark Web Forum Users. Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining.

- Rey, S., Stephens, P., & Laura, J. (2017). An evaluation of sampling and full enumeration strategies for Fisher Jenks classification in big data settings. Transactions in GIS, 21(4), 796–810.

- Richard, I. (2022). Web Scraping is Legal, US Appeals Court Reaffirms. Tech Times, available at https://www.techtimes.com/articles/276430/20220607/web-scraping-is-legal-us-appeals-court-reaffirms.htm [accessed 06/07/2022]

- Sano, Y., Yamada, K., Watanabe, H., Takayasu, H., & Takayasu, M. (2013). Empirical analysis of collective human behavior for extraordinary events in the blogosphere. Physical Review E, 87(012805), 1–8.

- Schkade, D., Sunstein, C., & Hastie, R. (2010). When deliberation produces extremism. Critical Review, 22(2-3), 227–252.

- Scrivens, R. (2020). Exploring radical right-wing posting behaviors online. Deviant Behavior,, 42(11), 1470–1484.

- Scrivens, R., Davies, G., & Frank, R. (2018). Measuring the evolution of radical right-wing posting behaviors online. Deviant Behavior, 41(2), 216–232.

- Scrivens, R., Osuna, A., Chermak, S., Whitney, M., & Frank, R. (2021). Examining online indicators of extremism in violent right-wing extremist forums. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2021.1913818.

- Scrivens, R., Wojciechowski, T., & Frank, R. (2020). Examining the developmental pathways of online posting behavior in violent right-wing extremist forums. Terrorism & Political Violence. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/09546553.2020.1833862.

- Scrivens, R., Wojciechowski, T., Freilich, J., Chermak, S., & Frank, R. (2021). Comparing the online posting behaviors of violent and Non-violent right-wing extremists. Terrorism & Political Violence. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/09546553.2021.1891893.

- Shrestha, A., Kaati, L., & Cohen, K. (2017). A Machine Learning Approach Towards Detecting Extreme Adopters in Digital Communities. 28th International Workshop on Database and Expert Systems Applications (DEXA).

- Si, X.-M., & Liu, Y. (2010). Power-law Distribution of Human Behaviors in Internet Forums. 2010 International Symposium on Intelligence Information Processing and Trusted Computing: 286-289.

- Soares, F., Recuero, R., & Zago, G. (2018). Influencers in Polarized Political Networks on Twitter. Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Media & Society.

- Strandberg, K., Himmelroos, S., & Grönlund, K. (2019). Do discussions in like-minded groups necessarily lead to more extreme opinions? Deliberative Democracy and Group Polarization. International Political Science Review, 40(1), 41–57.

- Sunstein, C. (1999). The Law of Group Polarization. John M. Olin Law & Economics Working Papers 91.

- Thomas, E., McGarty, C., & Louis, W. (2014). Social interaction and psychological pathways to political engagement and extremism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44, 15–22.

- Urman, A., & Katz, S. (2022). What they Do in the shadows: Examining the far-right networks on telegram. Information, Communication & Society, 25(7), 904–923. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2020.1803946

- Watkins, J. (1952). Ideal types and historical explanation. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 3(9), 22–43.

- Wojcieszak, M. (2010). Don’t talk to me’: Effects of ideologically homogeneous online groups and politically dissimilar offline ties on extremism. New Media & Society, 12(4), 637–655.

- Wojcieszak, M. (2011). Deliberation and attitude polarization. Journal of Communication, 61(4), 596–617.

Appendices

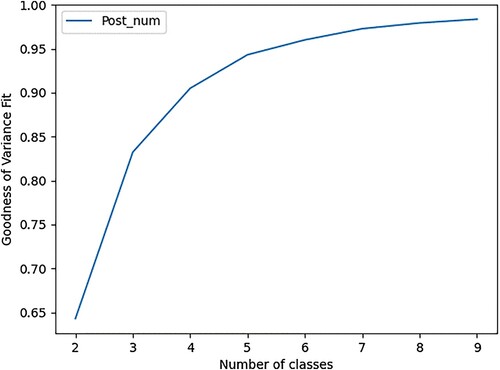

‘Super-Posters’ Appendix 1: Fisher-Jenks algorithm for categorising posters

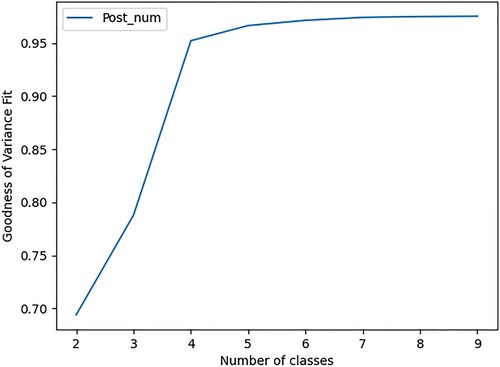

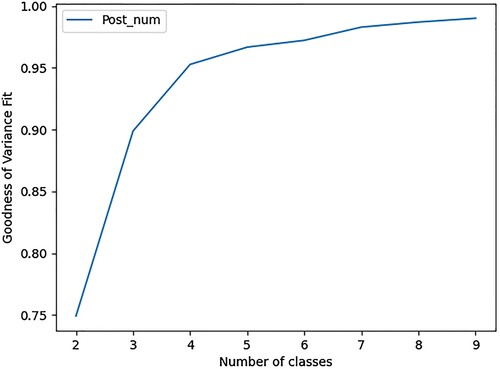

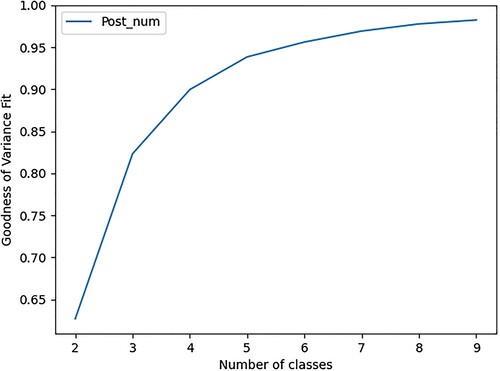

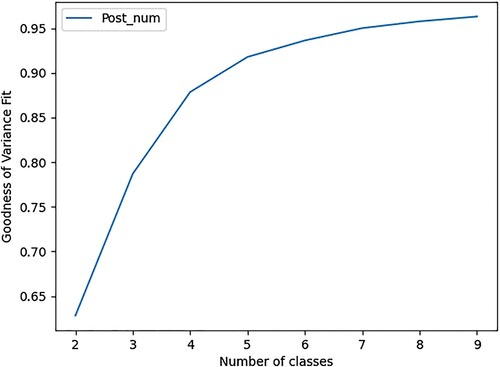

The Fisher-Jenks Natural Breaks Optimisation algorithm (Jenks Citation1977; Hartigan Citation1975; Rey et al. Citation2017) is similar to k-means clustering, but with a focus on 1D data. As with k-means clustering, the number of distinct groups, and that ‘breaks’ in the data, needs to be specified at the start. To determine the optimal number of groups for forum posters, the goodness of fit in variance (GVF) was used in conjunction with the elbow method. This involves calculating the amount of variance that is explained by the number of clusters and plotting this for different numbers of groups/breaks. The optimal number of breaks then form an ‘elbow’ in the resulting graph, and any number of clusters after the optimal number then result in diminishing returns and runs the risk of overfitting the data. This GVF calculation was carried out for all the forums featured in this paper, and for every single one the optimal number of groups was four. The graphs below show the GVF graphs for a few forums appearing in the paper.

Figure A1: The goodness of fit in variance graph for Chimpout.com. It can be seen from the "elbow" in the data that 4 groups was the optimal number for this forum.

Figure A2: The goodness of fit in variance graph for Chimpout.org. It can be seen from the “elbow” in the data that 4 groups was the optimal number for this forum.

Figure A3: The goodness of fit in variance graph for Islamic Awakening. It can be seen from the "elbow" in the data that 4 groups was the optimal number for this forum.

Figure A4: The goodness of fit in variance graph for Gawaher. It can be seen from the "elbow" in the data that 4 groups was the optimal number for this forum.

Figure A5: The goodness of fit in variance graph for Incels.is. It can be seen from the "elbow" in the data that 4 groups was the optimal number for this forum.

References:

Hartigan J. (1975) Clustering Algorithms. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Jenks G. (1977) Optimal Data Classification for Choroplethic Maps. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas, Department of Geography (Occasional Paper No. 2).

Rey S., Stephens P., Laura J. (2017) An Evaluation of Sampling and Full Enumeration Strategies for Fisher Jenks Classification in Big Data Settings. Transactions in GIS 21(4): 796-810.

‘Super-Posters’: Appendix 2: Construction of forum user networks

The creation of the user networks was a two-stage process, requiring the creation of the network data and then creating the visualisation.

The network data creation step involved first creating a list of all unique posters in a forum’s data. A method was then required to calculate the strength of the edges between forums users. Given how threads on these forums consist of a first post, referred to as an ‘Original Post’ (‘OP’), and then reply posts where users reply to the thread as a whole and not necessary just the most recent post made, the decision was made to calculate the weight of a network edge between two nodes in accordance with the number of threads both nodes have appeared in together. Thus, the second step in creating the network dataset involved cycling through each of the distinct users, and then counting how many times other individuals appeared in the same threads as the user in question. Any self-loop, counts of a user appearing in a thread with themselves, were then removed. This was then translated into a network matrix, with the values representing the number of times each user appeared in a thread with each other user. These values were used as edge weights in the final network visualisation. A hypothetical example of such a network matrix is illustrated in below.

Table A1. User network matrix for hypothetical forum.

The sizes of the three selected forums varied significantly: EuropeEcologieLesBruns has 1,827 nodes and 270,010 edges (network diameter = 4), Chimpout.org has 598 nodes and 10,846 edges (network diameter = 4), and Netzwerk has 71 nodes and 352 edges (network diameter = 4).

The visualization of this data was carried out in GEPHI 0.9.2, using the Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm, and with node sizes scaled depending on their degree score. For the two larger networks, the Noverlap layout was activated to enhance the visibility of each node. The GEPHI files are available upon request to the authors. Below we reproduce the networks in full-page sizes.

‘Super-Posters’ Appendix 3: Temporal distribution of hyper-posters’ activity

To offer an insight into the how the daily posting behaviours of Hyper and Super-posters vary in comparison to over users, the following posts per day graphs were created. These built upon the use of the Fisher-Jenks algorithm discussed in appendix 2. Specifically, once all of a forum’s users had been placed into one of the four categories of Hypo-posters, Normo-posters, Super-posters, or Hyper-posters, the top 3 posters, measured by their total number of posts were then selected. Depending on where the Fisher-Jenks algorithm created breaks in the data, this sometimes only included the top 3 Hyper-posters, but on some forums also included the top Super-poster.

The number of posts per day for these three users was then taken and plotted over the timeframe of the forum’s data. For each day during this time frame, the average number of posts for all other users, minus the top 3, was then also plotted to provide a baseline for comparison.

Figure A1. The number of posts made to Chimpout.com by the three top posters in the forum per day (red, green, and blue lines) and the average number of posts made per day by all other users (grey line).

‘Super-Posters’ Appendix 4: qualitative examples of influence

In the following examples, the letters (E, F, J) correspond to posters identified in the network analysis of chimpout.org.

Examples 1 and 2: Super-poster E recognises the validity of a hyper-poster’s F ‘analyses’:

Example1:

F: Except monkeys are a HIGHER life form [than black people] and have better hygiene!!

E: Actually you’re right. I insulted the monkey species by comparing them to niggers.

Example 2:

F: ‘Retarded’ is implied when saying ‘nigger’.

E: You're right, a nigger by definition has low IQ, maybe 60.

Example 3: Hyper-poster F welcomes a new poster and encourages him to express extremist views:

F: Welcome brother!! BASH niggers to your heart’s content here!!

Thank you!! I just needed that, since I can’t complain in ‘real life’, probably I would go to jail for using the word nigger. Btw., I really can't understand how you could live for such a long time together with these things (assuming you’re from the US), at least not if they behave like our fresh out of africa type things.

F: I Wish you all the best, hopefully Trump somehow manages to win.

Example 4: Hyper-posters J and F validate each other’s ideas:

J: It just goes to show: no niggers, no crime, know niggers, know crime.

F: Absolute truth!!