ABSTRACT

The Takarazuka Revue is commonly differentiated from other Japanese theatres based on their gendered stage performances and distinct relations between the performers and their patrons. So far, little research has been conducted on Takarazuka’s fan culture beyond the prism of a theatre performance and performer/fan relationships, especially when it comes to issues such as locality, fan tourism, or fans’ consumer practices that are not limited to the activities of fan clubs. Looking at Takarazuka from the perspective of the imagined core of Takarazuka fan culture offers us a glimpse into the reasons for the unprecedented popularity of this establishment: the fantasy beyond the stage. Drawing on ethnographic data from fieldwork conducted in Takarazuka City and interview data with Takarazuka fans, this article examines Takarazuka fans’ perceptions of Takarazuka Revue’s birthplace, the core of Takarazuka City, and the landscape surrounding its home-theatre, the Takarazuka Grand Theatre. I explore how past memories, lived experiences, and personal encounters of individual fans transform an urban neighbourhood into a shared fantasy surpassing the theatre stage; an embodied space characterised by movement, liminality, and affect, which is hidden behind the idea of the “Takarazuka space”. I argue that Takarazuka fans’ awareness of the ubiquitous Takarazuka space on both communal and personal levels signifies a multi-layered fantasy which exceeds the expectations of theatregoing practices, and provides us insight into the way local theatres within urban landscapes have the potential to shape individual fan identities and promote the creation of fan networks.

Introduction

On an early Monday morning of 29 May 2017, about 3,000 people gathered in front of a theatre in a suburban city on the outskirts of Osaka Metropolis. The arrival of a leading actress was welcomed with loud and enthusiastic cheers from fans gathered at the scene. In the climax of the gathering, the actress donned a red happi coat on top of her white suit and was ushered to sit in a mikoshi-like carriage, only to then be hoisted on the backs of fellow actresses and transported to the stage door in accompaniment of the crowd’s chants and applause. There, the remaining cast members greeted her with a small performance of their own and, after a final send-off chant from her fans, the actress entered the theatre. Within minutes, the crowd dispersed.

This account is a description of an unofficial fan event held to celebrate the last time Sagiri Seina entered the Takarazuka Grand Theatre as a “top star” of the Takarazuka Revue: a popular all-female Japanese theatre company. Organised on the last day of the local performance, this jovial happening remained on the tongues of many for days afterwards. Participants included members of Sagiri’s fan club as well as regular fans and local residents, all patiently waiting for the actress’s arrival; laughing and chanting together once the performance started. Illustrating the closeness Takarazuka performers have with the local fans and residents, this happening is especially interesting when we consider that it has been held informally (i.e. organised by fans and performers, and not regulated by the Takarazuka Revue company) and the event itself was taken outside of the theatre hall and into the public, open city space.

In this article, I focus on Takarazuka fans’ perceptions of the landscape surrounding Takarazuka Revue’s home-theatre, the Takarazuka Grand Theatre, located in Takarazuka City, Hyogo Prefecture. Regarded by fans as a “sacred site” (seichi),Footnote1 Takarazuka City is not only the birthplace but also the imagined core of Takarazuka fan culture. Like with most religious or secular pilgrimages to sacred sites, and despite many Takarazuka fans never making it to Takarazuka City, perceiving this location as “sacred” indicates its emotional value and importance to the increasingly transnational fandom.Footnote2 Although several scholars discuss the characteristics of Takarazuka fan culture and its unique patronage system (Miyamoto Citation2011; Nakamura and Matsuo Citation2003; Robertson Citation1998; Stickland Citation2008), very little attention has been paid to the role of urban space in local fan practices and behaviour. Attempting to examine Takarazuka fan culture from within its imagined nucleic centre, I explore how the urban space surrounding the Takarazuka Grand Theatre is perceived, created and made significant by the local fan community. Finally, by focusing on the case of Takarazuka Revue’s main location-bound home-theatre, I intend to show how geographical spaces can be instrumental in forming and maintaining fan networks, signifying the importance of physical convergence spaces in an ever-digitalising modern society.

This paper draws on ethnographic data from fieldwork conducted in Takarazuka City and interview data with eight Takarazuka fans, as well as additional visual data in the form of sketch maps drawn by six of the interview participants. The combination of participant observation, in-depth fan narratives, and visual materials provides a rare opportunity to trace theatre fan practices and lived experiences beyond the theatre stage and auditorium and examine the way these practices are dependent on the urban landscape of the space surrounding the theatre building, thus transcending the more “conventional” ethnographic approaches to a place-bound local community and its behaviours.

In the following sections, I will contextualize this research within the scope of existing scholarship, and describe the methods used to obtain data for the study. Then, I will briefly introduce the case of Takarazuka City centre before presenting the outcomes of my study. By analysing the meaning behind a ubiquitous “Takarazuka space”, I identify and characterise a fantasy space embodied within a set location as shaped by the lens of the lived experience of Takarazuka fans.

Contextualizing Takarazuka’s fan culture

Gaining academic recognition after Henry Jenkins introduced the concept of participatory culture (Jenkins Citation1992b), recent fan studies scholarship has often focused on the formation of fan networks in cyberspace. The emergence of digital fandoms eclipsed much of the established “off-line” fan practices by impacting the ways through which fans gain access to information and communicate with each other (Bennett Citation2014). In cyberspace, originally minor practices have become more widespread and developed into multiplatform communities allowing fans to interact daily and from the comfort of their own homes. Duffett (Citation2013, 243) proposes that although sociologists tend to commonly characterize modern society as leaning toward alienation, online fan clubs and alliances of fan internet users become replacement communities, facilitating and fostering a sense of an imagined companionship that moves them away from social isolation. This social and cultural function of fan interaction becomes crucial in understanding the societal importance of fan practices in everyday lives, as many scholars argue that feelings of affect and affinity spaces are an important characteristic of fandom formation both online and off-line (e.g. Black Citation2008; Grossberg Citation1992; McCormick Citation2018).

In his discussion on the place of fandom, Cornel Sandvoss (Citation2005, 53–55) argues that while non-territorial, virtual spaces of fan consumption are becoming increasingly common, fandom is an in situ activity: practised in physically located places, such as theatres or sports stadia, but also private living rooms. In some cases, fans attach a considerable amount of emotional value to spaces simultaneously imagined and physical. Described by Matt Hills as “cult geographies” (Citation2002, 144), a growing body of research discusses the phenomenon of fans travelling to “real” locations seen as significant to different texts and reimagined around fan interests. Scholars have examined fan tourism (sometimes framed as pilgrimage) to public sites, such as film and television productions of The X-Files (Hills Citation2002) or The Lord of the Rings (Tzanelli Citation2004), as well as private spaces associated with icons, such as Elvis Presley’s estate Graceland (Rodman Citation2013) or Jim Morrison’s grave (Margry Citation2008). Some of these sites are located in urban areas with generic streets, unrecognizable to all but fans, but others become iconic representations of the text they are associated with. In the case of Japan, one well-studied example of the latter is the “sacred site” of Japanese otaku culture, the Akihabara neighbourhood in Tokyo (Galbraith Citation2010, Citation2019; Morikawa Citation2012). Filled with manga, anime and game speciality shops, Akihabara is recognized as the commercial epicentre of otaku culture not only domestically but also internationally (Morikawa Citation2012). However, it’s not unusual for foreign fans of Japanese popular culture to express disappointment when visiting Akihabara due to the dissonance between the imagined “Otaku Mecca” and the actual place (Clyde Citation2020; Galbraith Citation2019, 173–178; Sabre Citation2017). This gap indicates that despite universal recognition of a “sacred site” in a given fan culture, there can be considerable differences between perceptions of local and non-local fans.

Historically, the theatre has been tied to physical landscapes, making theatregoing a social practice occurring in “real” places. Notwithstanding the similarities with fan cultures that develop around popular cultural texts, fan studies rarely engage with the community of theatre fans (Hills Citation2018). When modern theatregoing practices are considered, there is a tendency to focus on the relationship between performer/performance and audience in the context of onstage theatrical events, and not on fan practices happening outside of the theatre hall (Barrett Citation2016). In a similar fashion, although many studies explain the emergence of Takarazuka fan culture as dependent on its predominantly female audience, the focus has been placed on the unusual cross-gendered performances of the otokoyaku (male-role performers) and their relations with (female) fansFootnote3 (Nakamura and Matsuo Citation2003; Robertson Citation1998; Stickland Citation2008). While extending the discussion to include offstage relationships between Takarazuka actresses and their fans, these debates are nevertheless centred around the persona of the performers; an extension of the onstage performances and Takarazuka’s image branding.

A growing body of literature has attempted to characterise the fantasy world of Takarazuka by exploring the audience rather than the performers. Asserting Kawasaki’s (Citation1999) definition of Takarazuka fans as active consumers of shōjo bunka (girls’ culture), Yamanashi (Citation2012) argues that fans take on a dynamic role in producing the Takarazuka fantasy by purchasing Takarazuka-themed products in theatre souvenir shops or partaking in other various consumer practices, therefore creating a complex commercial relationship between the Revue and its fans. This active involvement of Takarazuka fans is further examined by Miyamoto (Citation2011) who demonstrates that fan support observed in the unofficial fan clubs of Takarazuka actresses is essential to aid and elevate each actress’s status within the company. Drawing on this association of strong personal involvement combined with consumer practices dictating much of fans’ individual lifestyles has prompted Wada (Citation2015) to profile Takarazuka fans as “ultra-high involvement consumers.”

These studies indicate that there is a strong relationship between the performer/performance and the audience’s engagement in the Takarazuka context. However, although this relationship becomes one of the pillars supporting the Takarazuka fantasy, research to date has not yet addressed the regional differences between Takarazuka fan practices or the prevalence of activities happening outside of the theatre building. Takarazuka Revue has two exclusive base theatres: the Takarazuka Grand Theatre in Takarazuka City and the Tokyo Takarazuka Theatre in Tokyo in the Hibiya neighbourhood. The former is located in a dormitory suburb, the latter in a bustling shopping district of Japan’s capital, yet both gather a similar annual audience of over one million (Morishita Citation2015, 28). Tokyo is where Takarazuka actresses perform periodically, but Takarazuka City is the headquarters of Takarazuka Revue: a place where actresses train, debut and make a career and where the shows are produced, rehearsed and premiered before being performed on stage. Above all, Takarazuka City is seen as a “sacred site” to Takarazuka fans; the Revue’s birthplace, a materialized “dream world” (yume no sekai), and an imagined centre of Takarazuka fan culture. Takarazuka City and its urban development are frequently discussed in relation to the Revue’s formative years (Kawasaki Citation1999; Tsuganesawa Citation1991; Watanabe Citation1999), yet the practices of the local fan community and their relationship with Takarazuka’s Grand Theatre’s spatial location remain unclear.

This article aims to fill the aforementioned gaps in the literature by focusing on Takarazuka fan practices localized within Takarazuka City but expanding beyond the theatre stage, and it attempts to characterise Takarazuka fan culture from within its imagined “sacred site” core in Takarazuka City. I will argue that the material, geographic space surrounding Takarazuka’s base theatre plays a crucial role in creating the imagined “dream world of Takarazuka” fantasy, and that the way fans’ perceive and move through the vicinity of the Takarazuka Grand Theatre is vital to understand Takarazuka’s phenomenon in local Kansai culture. Furthermore, by discussing the local Takarazuka fan community’s micro-level relations with the urban city landscape and exploring this landscape’s importance in individual fans’ everyday life narratives, this paper ventures into the yet unresearched area of theatre and fan studies, and offers new insight into the spatial understanding of modern fan cultures.

Methods and data

This paper draws on ethnographic data from fieldwork conducted between 2017 and 2018 in Takarazuka City, including a period of three months of immersive participant observation, as well as mapping methods using sketch maps. During the immersive part of the research, I lived within walking distance of the Takarazuka Grand Theatre and the surrounding area in Takarazuka City centre. This gave me the opportunity to visit the field site frequently on weekdays and weekends, performance days and off days, which allowed me to actively observe and interact with not only zealous Takarazuka fans and local shop owners but also casual theatre-goers and local residents. Aside from on-site data collection and participant observation, this paper draws on data derived from in-depth interviews with eight long-term fans of the Takarazuka Revue whose fan practices are focused in (but not limited to) the Kansai region. The participants were recruited using a combination of random and snowball sampling. All the interviews were semi-structured and conducted in two separate sessions with a total time span varying between 3.5 to 7 hours.Footnote4 All the interviews were carried out in cafes or restaurants within walking distance of the Takarazuka Grand Theatre that were chosen by the participants. The conversations were recorded and later transcribed, except in one case when the participant acted intimidated by the presence of the recorder. In this instance, I took detailed notes throughout our conversations and transcribed the interview from memory, later contacting the participant to confirm or clarify the details. The data obtained from the participant observations and interviews were analysed based on the narrative ethnography approach (Gubrium and Holstein Citation2008).

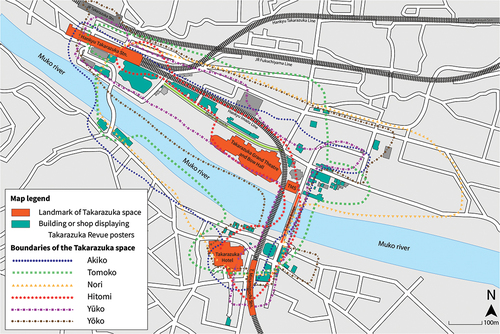

While analysing the first round of interviews with the Takarazuka fans conducted during my fieldwork in 2017, I discovered that the majority of participants alluded to a ubiquitous “Takarazuka space” (Takarazuka-no kūkan) when describing their individual fan practices outside of the theatre building. Intrigued, I decided to further investigate whether their definitions of this space were comparable, and whether the space they referred to was indeed in the same place. Furthermore, inspired by Setha Low’s (Citation2017) concept of embodied space,Footnote5 I was also interested in the ways individual fans move through this space and the patterns their movement may present. In order to document fans’ perceptions of the Takarazuka space, this study applied a mapping method referred to as “sketch maps.” In contrast to cognitive mapping methods using mental maps drawn from memory (Lynch Citation1960), Boschmann and Cubbon (Citation2014) argue that sketch maps (i.e. sketches drawn manually over the top of spatially referenced maps) can be used together with qualitative geographic information systems (QGIS) as a method helping visualise socio-spatial processes or individual perceptions of space. During the follow-up interviews, the participants were asked to draw their perceived boundaries of the area referred to as the “Takarazuka space” on a generally referenced map of the Takarazuka Grand Theatre and surrounding area provided by the author,Footnote6 and explain their reasoning for drawing the lines in specific places while reflecting on their individual experiences. The participants were informed that there were no “wrong” answers and encouraged to draw according to their personal perceptions. Six of the fans drew sketch maps, which were then collected and later scanned to make a combined digitized map of the Takarazuka space boundaries.

Takarazuka city centre and perceptions of the Takarazuka space

As of 1 August 2020, Takarazuka City, Hyogo Prefecture, had a population of 224,438. Although the number appears to be in decline since 2012, the population itself has increased more than five times since the city’s formation in 1954. Established in a municipal merger which followed a wave of similar amalgamations after the enactment of the Municipality Merger Promotion Law in 1953 (Yokomichi Citation2007), the area which became the core of Takarazuka City and central to this paper’s analysis was previously part of Kohama Village in Kawabe District. Located in the suburbs of Osaka Metropolis, the area is exemplary of what is now referred to as “Hanshinkan modernism”: a modernist style of architecture characterised by its close connection with culture that emerged during the process of suburbanisation of the Osaka Bay area (Toda Citation2009). At the beginning of the 20th century the area was still an undeveloped agricultural region on the outskirts of Kobe and Osaka metropolises and was known only for its local hot spring culture, and it thus presented great potential as a commuter city which would connect both urban and cultural developments.

In 1910, Hankyu Takarazuka Station became the terminus for the newly built Minō Arima Electric Railway’s Takarazuka Line (now known as the Hankyu Takarazuka Line), connecting the region with Osaka’s central Umeda Station. In order to increase the number of train passengers, the founder of the railway, Kobayashi Ichizō, established the Takarazuka Revue (then Takarazuka Shōkatai, the Takarazuka Choir) in 1913. The Revue was originally part of a larger hot spring complex, the Takarazuka Shin-onsen (Takarazuka New Hot Springs), which later became the amusement park known as Takarazuka Familyland and included a zoo as well as a botanical garden. Along with the rising popularity of Takarazuka, Kobayashi decided to train all of the actresses in a private school affiliated with the Revue and in 1919 established the Takarazuka Music School (Takarazuka Ongaku Gakkō). In 1921, Hankyu Takarazuka Station became the terminus for another railway line, the Hankyu Imazu Line (then, Saihōsen), which linked Takarazuka with the nearby city of Nishinomiya, and later also Kobe. Next, in 1924, Kobayashi ordered the construction of the biggest theatre in Japan at the time: the Takarazuka Grand Theatre (Takarazuka Daigekijō). The Grand Theatre became the “base theatre” (honkyochi) of the Revue and a permanent attraction to all Familyland visitors.

Although the Takarazuka Familyland complex closed down in 2003, the Takarazuka Revue’s home-theatre, the Takarazuka Grand Theatre, remains in the same place it was first established. The rural village has indeed changed into a vibrant commuter town, with the city’s centre now sporting a number of apartment towers and shopping malls, and only a handful of hot spring facilities. Despite thousands of theatre-goers visiting the Grand Theatre every day and hundreds of Takarazuka fans gathering to observe the actresses around the theatre’s backstage door, on Wednesdays the area becomes a ghost town. With Wednesday being the only regular performance-free day of the week, even Takarazuka Station, the city’s main train hub, becomes eerily quiet outside of commuting hours. The majority of the shops in the station’s nearby shopping mall Cerca are closed and the sole people crossing the nearby elevated pathway known as hana-no-michi (lit. flower road) appear to be local residents on a stroll.

But how do Takarazuka fans see this space? And how does this space factor into their experiences of and meanings of Takarazuka fandom? In the following pages I examine the way fans perceive and interact with the centre of Takarazuka City.

The shared fantasy of the Takarazuka space

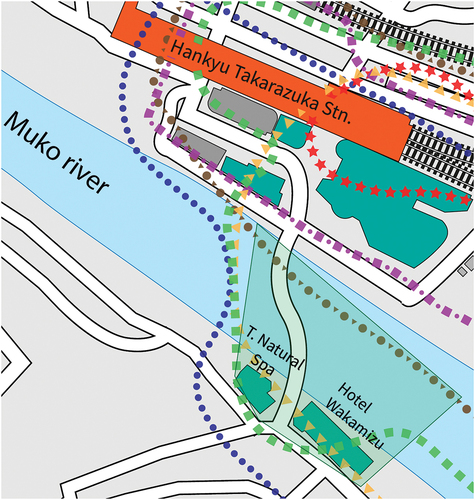

Analysis of the sketch maps drawn by the Takarazuka fans revealed an area stretching from Hankyu Takarazuka Station to the Takarazuka Minamiguchi Station building, with the Takarazuka Grand Theatre at its core (). Furthermore, while individual perceptions of the “Takarazuka space” as a physical place located within Takarazuka City shared several characteristics, the boundaries varied greatly and were closely connected to the specific lived experience of each fan. Let us now consider the shared elements and address the differences of perceptions regarding the space and its boundaries in the following section.

The maps delineated by Takarazuka fans show that the Takarazuka space has seven commonly shared landmarks (marked in red in ): (1) Hankyu Takarazuka Station, (2) hana-no-michi pathway, (3) Takarazuka Grand Theatre and Bow Hall building, (4) Takarazuka Music School, (5) Takarazuka Ohashi Bridge, (6) Takarazuka Hotel,Footnote7 and (7) Hankyu Takarazuka Minamiguchi Station. The presence of common visual markers was not surprising, as “landmarks” are among familiar point-references used by individuals to navigate urban spacesFootnote8(Lynch Citation1960). However, the presence of all seven of the landmarks in a shared perception of the Takarazuka space signifies the visual importance of the largely unchanged city landscape. With the exception of the Takarazuka Music School building, all of the landmarks constituting the core of the space have remained in the same geographic location throughout the Revue’s century-old history. Due to Hankyu Takarazuka Station being the terminus of two major railway lines connecting the suburban city with the metropolises of Osaka, Kobe, and Nishinomiya, the core of Takarazuka City centre developed alongside the Takarazuka Revue company, thus creating a distinct relation between local and corporate structures.Footnote9 Nestled between two stations along the Hankyu Imazu and Takarazuka Lines, the Takarazuka space emerged in parallel to the developing city landscape and became central to the various activities partaken by theatre fans.

Another significant aspect of the shared landmarks was the order in which they were identified. Regardless of the form of transportation the participants use to enter the space, all started their drawings by pinpointing the location of the Takarazuka Grand Theatre first, and Hankyu Takarazuka Station second. Only then would they begin to draw the lines of the Takarazuka space’s boundaries, which in all cases started next to the Takarazuka Station building. This appearance of an order in which fans identify the area suggests two things: first, the space has a common entrance point, and second, fans visualise how they move within the space. The idea of urban landscapes having a “front” and “back” has been discussed in Yi-Fu Tuan’s Space and Place (Tuan [Citation1977] 2018). Drawing on the example of traditional Chinese city structures, where the back (north) and the front (south) were distinctly expressed in urban design and intentionally divided areas considered as sacred versus profane, Tuan considers highways as potential and unplanned “fronts” of modern cities (Tuan [Citation1977] 2018, 41–42). While no longer related to processional routes or demarking social class boundaries, the sense of spatial asymmetry of modern cities may still evoke a symbolic gateway image to its visitors. If, based on the perception of Takarazuka fans, we regard train stations as the potential entrance “gates” and “fronts” to Takarazuka City, Hankyu Railway and its stations may also be seen as a spatial gateway to the materialised Takarazuka fantasy world. Similarly, as fans visualised the entrance to the space, it became apparent that rather than a stationary place, their perceptions were dependent on memories of spatial movement. This suggests that bodies set in motion, particularly the movement through liminal space, become a significant dimension in fans’ perception of Takarazuka space. For Tuan, movement was also the element which differentiated space from place. He argued that while the openness of space allows for movement to happen, a place is a pause in the movement (Tuan [Citation1977] 2018, 6). This distinction is illustrated by Takarazuka fans’ mobility patterns while within the space, deepening and going beyond the experiences of typical theatre-goers who limit their experiences to the stage and theatre building. Indeed, fans’ narratives indicate that mobility and spatial movement are essential elements in understanding the significance of Takarazuka space in individual fan practices. Let us now turn to the differences in perceptions of the Takarazuka space and the implications they carry.

Fantasy strolling through the Takarazuka space

The current building of the Takarazuka Grand Theatre was constructed in 1993 and is located in the exact same place as its predecessors have been since 1913. The fans refer to the venue and its immediate surroundings as the “village” (mura)Footnote10 and regard it as a “sacred place” (seichi) of Takarazuka fan culture. Considering the Grand Theatre as a sacred site not only highlights the importance of the area, but also hints at fans’ personal feelings toward this place. Of course, the use of the term “sacred place” to refer to the Grande Theatre does not imply that fans are religious. Comparisons between fan practices and religious cults are common in the mass media, and many studies (Hills Citation2002; Jindra Citation1994; Till Citation2010) discuss the similarities between fan culture and religion. However, Hills (Citation2002) argues that the phenomenon of fandom is closer to religiosity rather than religion. That is, although belief as well as devotion are frequently remarked on as prevalent elements of many fandoms, Hills asserts that the religious discourse is a result of fans narrating their practices using terminology they are most familiar with, rather than an indication of actual fandom-based “neo-religions” (Hills Citation2002, 119). This also appears to be applicable to some Takarazuka fans who have been described as fanatical in English scholarship (Robertson Citation1998), where the focus was placed on aspects of devotion and specific fan behaviour rather than religiousness. In these ways, studies of Takarazuka and other fandoms have shown us how fandom is marked by a high degree of passion and devotion to specific material and behavioural practices. Likewise, from a spatial perspective, when a certain site is recognized as a “sacred place” among fan communities, this calls for close investigation of the particular practices fans engage in within the place and the meanings that such places carry for fans.

The journey and the destination: Takarazuka fan pilgrimages

In the previous section, I have discussed how it is possible to consider common landmarks of the Takarazuka space as its “entrance” and “exit” gates. In both of these cases, the landmarks in question were train stations along the Hankyu Railway lines: the railway company which not only established but still owns and manages the Takarazuka Revue and its employees. Interestingly, though perhaps not surprisingly,Footnote11 Hankyu Railway’s maroon-coloured trains make a frequent appearance in most Takarazuka fans’ narratives of their youth. Some reminisce about seeing high school girls crowded over albums filled with photographs of Takarazuka actresses every time they boarded the train. Others remember glancing at posters of Takarazuka productions hung inside the trains or pasted on the walls of every station along the Hankyu lines. It also appears that depending on the location of one’s residence in the Kansai region, the numbers of daily encounters with the Revue could decrease or increase substantially.

Megumi,Footnote12 a self-employed woman in her 30s, was introduced to Takarazuka in her early youth by her mother. She was one of the schoolgirls who chatted passionately about her favourite actress while riding the train, and would commute to school using the Hankyu lines. Megumi moved out of her family home in Osaka after graduating from high school but noticed that even though she still lived within the city (now in one of its southern districts) she suddenly found it remarkably more difficult to find traces of the Takarazuka world in her immediate vicinity. While previously she was surrounded by fans both among her friends from school and their mothers (many of them retired Takarazuka actresses), she now found herself in an area where many people felt indifferent or oblivious to the existence of the Revue. The difference appears to be related directly to the new geographic location of her residence: an area not operated by any of the Hankyu Railway lines and one which does not have a direct transfer connection to Takarazuka. More than a form of transportation, then, the Hankyu lines can be seen as an immediate link between fans and Takarazuka in their everyday lives; for those who grow up within its service area, it provides an almost subliminal, ubiquitous immersion in the Takarazuka fantasy world, which only becomes noticeable once one leaves the area.

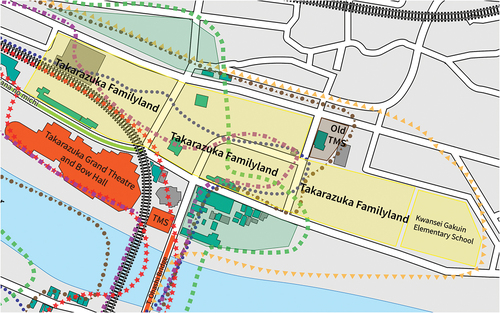

This sentiment is also illustrated by the experiences of Nori, a male salaryman in his 50s.Footnote13 In our conversations, Nori reflects that while his gender has had little impact on his individual experience as a Takarazuka fan, it has clearly shaped his early encounters with the Revue. Despite not becoming a fan until his late 20s, Nori recalls his mother and sister watching Takarazuka stage productions playing on TV every SaturdayFootnote14 when he was a child and seeing posters of upcoming performances on the trains. Most importantly, though, he knew about Takarazuka Revue through its connection to the Takarazuka Familyland amusement park. Taking a closer look at the boundaries of the Takarazuka space that Nori has drawn on his sketch map (), it is evident that he covers a significantly wider area to the east of the Takarazuka Grand Theatre than the other participants: specifically, the area where Familyland was located until the park’s closure in 2003. Like many residents in the Kansai region, Nori frequently spent his childhood weekends visiting the entertainment complex with his family. When in Familyland, he recalls spending hours playing at the park with his father, while his mother and sister would go off to see Takarazuka performances in the nearby Grand Theatre. This experience has left a lasting impact on his perception of the Takarazuka space because even though at the time he had never set foot in the Grand Theatre, he still acknowledged it as an integral part of the amusement park. Despite Familyland’s closure, Nori considers the place where it was located as part of the Takarazuka space, although his current association is first and foremost with the Revue.

Figure 2. Close-up of the area enclosed in Nori’s (yellow triangle), Tomoko’s (green square), and Yōko’s (grey dot) perceptions of the Takarazuka space.

For Nori, the boundaries of his perceived Takarazuka space remain the same, although its personal definition has changed over time. He currently defines this space as “a space where Takarasiennes [Takarazuka actresses] exist”, which includes both the theatre stage and the theatre building’s neighbouring area, despite associating it only with playful time spent at the amusement park in his earlier years. However, Nori believes that his feelings toward the space haven’t changed. Although he now lives further away from Takarazuka, he still rides on one of the Hankyu train lines whenever he’s visiting the city. And here Hankyu Railway’s function as a direct connection between fans and the Revue reappears as the train becomes vital to Nori’s theatregoing experience and perceptions of the space. One of the most important aspects of Nori’s Takarazuka space is the feeling of excitement (wakuwaku) he reportedly feels as soon as he boards the train leading to Takarazuka. In his descriptions, this affective state remains unchanged from the period when he was a boy on his way to the amusement park to an adult man on his way to watch a theatre performance. For Nori, Hankyu trains are a significant link connecting his everyday life with the Takarazuka space: a “dream world” detached from his daily reality.

Both Megumi’s and Nori’s perceptions of the Hankyu trains suggest that the journey to Takarazuka City itself is an important part of experiencing the Takarazuka space. As discussed above, for some fans the connection to the space is felt from a great distance beyond the space’s geographic boundaries and the sensation is extended to trains with destinations of Takarazuka City and the Hankyu Takarazuka Station. Based on these perceptions and the common tendency of Takarazuka fans to view the Grand Theatre as a sacred place, it is possible to view the train journey Takarazuka fans make to see the performances staged at the Grand Theatre as some version of a modern pilgrimage. Williams (Citation2018) argues that the concept of pilgrimage can be useful in understanding relations between fan tourism and community as it illustrates the state where fans utilize a liminal space unconstrained by everyday life.

As a liminal space, Takarazuka can be considered as more than a geographic location, that is, more than a place that is frequented by non-resident theatre-goers only as a transitional passage to the theatre stage. For non-resident fans like Nori, each visit to Takarazuka City is marked by Takarazuka Revue’s performance at the Grand Theatre, and yet the “pilgrimage” to this place does not begin nor end with spectatorship of the plays performed. Although a typical production lasts approximately three hours, Nori has a habit of spending most of his theatregoing day in the area he perceives as part of the Takarazuka space. Starting with the feeling of elation as soon as he boards the train for his journey, Nori looks forward to not only watching the newest Takarazuka performance but also to his other regular activities: having a meal in restaurants frequented by Takarazuka actresses, shopping for stationery at one of Grand Theatre’s many shops, or simply chatting and gossiping with fellow fans. Similar practices are common among other Takarazuka fans, as evidenced by many of the shops and cafés located in the theatre’s vicinity becoming crowded outside of the theatre’s performance times. More than a straightforward theatre enthusiast’s experience, then, it is the dissociation from one’s routine life that makes the space especially appealing to some fans. For fans like Nori, the space offers a liminal experience, a sense of escapist fantasy that he says he wants to “soak” himself in (shimikomitai) before returning to his everyday routine. In other words, the Takarazuka fantasy world is not just what one sees on stage, but it is a broader spatiotemporal experience that envelops fans within the Takarazuka space.

Williams (Citation2018) discusses how social relations between participants of pilgrimages can be seen as equal because they are engaging in a socially-shared experience unattainable in their everyday lives through a concept referred to as communitas. Communitas, as originally proposed by Turner (Citation1969), describes the feeling of comradeship when individuals experience liminality as a group – a sense of bliss formed by sharing a temporary bond among participants of a social event. Communitas is certainly present in one of the most popular Takarazuka fan practices – waiting at stage doors and observing actresses either before (irimachi) or after a performance finishes (demachi).

For Hitomi, a female office worker in her 40s, participating in demachi is one of her favourite elements of being a Takarazuka fan. Currently not a member of any of Takarazuka’s personal fan clubs, Hitomi enjoys overseeing Takarazuka performers exiting the theatre, but what she appreciates in the custom the most is chatting with fellow fans and making new friends. Although a typical demachi waiting time takes approximately two hours, most actresses rarely stop to chat for more than a minute, and never with fans who do not belong to their personal fan clubs. Yet despite offering only the briefest glimpses of actresses, hundreds of fans gather outside the theatre each day. For Hitomi, demachi is more about extending her theatregoing experience by observing the fantasy beyond the stage in a communal setting. Although each theatre stage performance is seen by members of an audience as a group, it is a rather personal experience providing little opportunity to interact with others. Outside the stage door and crowded on the elevated hana-no-michi pathway, however, fans are allowed to freely gossip and cheer, comment on individual actresses as they exit and applaud them, or even take commemorative photographs of them.Footnote15

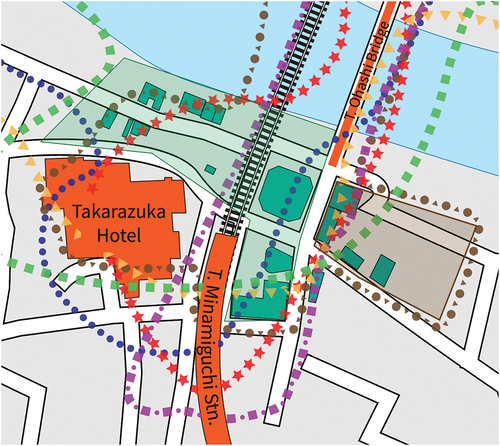

Although participation in a demachi for non-club-affiliated fans occurs on an individual basis, most fans nevertheless tend to wait until the exit of the leading actress before departing. Likewise, after finishing a demachi, Hitomi typically goes to one of the restaurants owned or frequented by Takarazuka performers to continue chatting with other fans, and rarely moves away from the hana-no-michi. This is one of the reasons the sketch map drawn by her depicts one of the smallest areas among the interviewees (, red line). Focused on the hana-no-michi, the boundaries of Hitomi’s Takarazuka space are limited to places associated directly with her personal experiences as a Takarazuka fan: i.e., the places she uses to interact with other fans. This also shows that although communitas is an important part of Takarazuka fan culture, it does not detract from the significance of individual fan experiences. Takarazuka fandom can thus be simultaneously collective and individual, marked by both shared sacred spaces and personally meaningful places. This brings us to another important aspect of Takarazuka space: its function as an affective space.

Affect, belonging, and care for the space

Unofficial personal fan clubs are an integral part of Takarazuka fan culture. Continuous support offered by individual fans is imperative to Takarazuka actresses’ position within the company (Miyamoto Citation2011), and they also allow for deep interpersonal bonds to evolve among its club members. Fans with a long club membership history admit that the friendships they have formed with fellow members continue well past the supported actress’s retirement and subsequent disbanding of the club, and many speak openly of relying on their advice in major life decisions. For some fans, their involvement in Takarazuka fan culture has led to creating a complex sense of belonging and care for the Takarazuka space.

Tomoko, a female office worker in her 40s, is a fan whose close relationship with the Takarazuka space has had a significant impact on her life choices. Raised in Ehime Prefecture, Tomoko’s first encounter with Takarazuka Revue was a TV-broadcasted performance she watched as a middle school student. Although instantly captivated, Tomoko struggled to gain access to any information about the company while her geographic location made theatre-going difficult. After a relentless search, Tomoko discovered Kageki, one of Takarazuka’s monthly magazines, which she could order at her local bookstore. It was through the pages of Kageki that Tomoko became introduced to Takarazuka’s fan club culture and began to develop the image of Takarazuka City as a sacred site. She was finally able to set foot in the Takarazuka Grand Theatre as part of her middle school graduation trip, a visit she animatedly reminisced with unbidden enthusiasm when she spoke with me more than three decades later. It is there, she explains, that her “Takarazuka fever” (Takarazuka netsu) began.

Despite having to return to Ehime to finish her schooling, Tomoko entered a fan club of an otokoyaku performer and continued to write fan letters. After graduation, Tomoko decided to move to Takarazuka City but, upon meeting opposition from her parents, settled for a vocational college in Osaka. Thereafter, Tomoko would use all her available free time and holidays to commute to the Grand Theatre, where she eagerly immersed herself in the local fan culture. While still a college student, she was asked by her club leaderFootnote16 to become the club’s “Pot-san” (potto-san). As a Pot-san, Tomoko was in charge of preparing and delivering the performer’s water bottle to the theatre’s stage door area several times a week even when she had no actual theatregoing plans. The position brought Tomoko one step closer to the performer and allowed for frequent one-on-one interactions; it was also a presentation of trust in Tomoko as a loyal and reliable fan. By the time she graduated from college, Tomoko was already a stable member of the fan community and has herself become a leader of an actress’s fan club. Securing a job in Takarazuka City, Tomoko became one step closer to realising her dream of belonging to Takarazuka “dream world”. A decade later, Tomoko was in her mid-30s and an owner of an apartment within walking distance from the Grand Theatre. She dedicated her apartment’s only room with a view of the theatre to store her collection of Takarazuka-related merchandise.

Tomoko’s life story paints an interesting picture of how physical distance changes the way we perceive landscapes. In our conversations, whenever Tomoko talked about the time before she became a resident of Takarazuka City, she would refer to it as a sacred site. This was also the first word that would come to her mind when prompted to explain what the Takarazuka space was. However, while the sense of reverence is still present, it has since become linked with feelings of nostalgia toward the past. Tomoko spoke fondly of her early days as a Takarazuka fan and laughed at many of her blunders which stemmed from not knowing Takarazuka’s unwritten rules. Although the change was gradual, it is clear that the space lost most of its sense of sacredness and wonder after it became a daily fixture of her life. Paradoxically, despite this shift of perception, closer physical proximity to the theatre allowed Tomoko to get more involved in the fan club culture and thus actively participate in creating the shared fantasy world, while simultaneously deepening her personal feelings of belonging and affect toward Takarazuka. This suggests that the perceived sacredness of symbolic fan spaces may be conditional to the feeling that a “sacred site” is detached from one’s everyday reality and the feelings of affect may differ depending on the fan’s positionality. In other words, losing the sense of reverence may be indicative of more, not less personal feelings towards the fandom by shifting from the imagined and perhaps temporary feeling of having a “home away from home” to the more permanent, secure and stable sense of being “at home.”

Relph (Citation1976) argues that our lived experiences of places can lead to the creation of a close attachment, an affective bond with the familiar landscape (Citation1976, 37–38). It is clear that Tomoko, like many other fans, felt a sense of belonging toward the Takarazuka space long before becoming a part of it. It is also visible in the boundaries of the space drawn by Tomoko (). Encapsulating a remarkably large area, it is a direct reflection of her fan experience by showcasing both her time as a novice and a veteran fan and focusing on fan practices which revolved around the organised fan club culture. It incorporates places she considers landmarks of Takarazuka’s sacred site (such as the Takarazuka Ohashi bridge and the Wakamizu Hotel’s café from where she would take commemorative pictures of the Grand Theatre, ), as well as areas filled with small shops where she used to run errands for the performer she was supporting at that time (such as cafés, accessory shops, printing services, wig makers, and hair salons) (). According to Tomoko, as the boundaries of her Takarazuka space grew steadily wider, the closer she felt to Takarazuka’s fan community and the deeper her connections spread. Representing a geographic location Tomoko yearned to belong to and embodying the practices she partook in, the space is permanently and directly connected to her identity as a Takarazuka fan.

Figure 3. Close-up of the area enclosed in Tomoko’s (green square) and Yōko’s (grey dot) Takarazuka space.

Figure 4. Close-up of the area enclosed in Nori’s (yellow triangle), Tomoko’s (green square), and Akiko’s (blue circle) Takarazuka space.

A similar affective sentiment was expressed by Yōko, a female office worker in her 40s from Osaka. Yōko joined a leading otokoyaku star’s fan club while still in high school, and upon graduation she chose to find a job in Takarazuka City and make the city her home. Although the actress she supported retired within a few years of her move to Takarazuka City, Yōko continued to see Takarazuka performances regularly and soon became interested in another young performer. Within a few months, Yōko established the performer’s personal fan club and became its leader, effectively dedicating most aspects of her daily life to her second Takarazuka performer “crush” for the next 12 years. While holding down a full-time office job, Yōko’s duties as a club leader dictated that, before starting and after finishing her own work, she would oversee her actress’s irimachi and demachi during any performance period and rehearsals. Yōko would take part in such club practices daily, which required her to use up all of her available paid leave to attend to the actress when she performed in Tokyo. Such a demanding schedule would be organized well in advance based on the needs of the performer she was supporting and would last throughout their acting career in Takarazuka.

Like Tomoko, Yōko’s adolescent admiration has made a lasting impact on her choice of a place to live and work. By living in Takarazuka City, Yōko could interact with and support Takarazuka actresses on a daily basis and was able to balance her responsibilities as a club leader and a full-time employee. This was only possible because of her proximity to the Takarazuka Grand Theatre. Her personal understanding of the Takarazuka space is marked by places she frequently visits and associates with fan practices (). She pointed to many of the shops, restaurants, and other establishments (many of whom display postcards sent by actresses [reijō] or signed posters of upcoming Takarazuka plays) as well as the actresses’ living space. Notably, even though Takarazuka Music School moved to a different location in 1998, Yōko still included the previous building (now known as the city-owned cultural centre, Takarazuka Bunkasōzōkan) within the boundaries of her space (). She described the place as an essential part of her “fan era” as it was still in use during her early fan years, and explained that she feels more attached to it than the new Music School building. This appears to be a characteristic shared among many of the fans’ sketch maps; the boundaries of the Takarazuka space are often drawn around landmarks of personal importance or places toward which fans feel they have a direct connection to. In this sense, individuals’ personal fan-culture geography – in this case, the “Takarazuka space” – is best apprehended as a four-dimensional space extending through space and time, which includes not only physical spaces in the present but also historical spaces of the past that are intertwined with their personal biographies.

Jenkins (Citation1992a, 223) argued that a sense of community of a given fan culture is reinforced by the creation of shared experiences and common feelings. While this holds true for many Takarazuka fan practices, the deep sense of belonging toward a space with a set geographic location expressed by some fans can be much more individualised. It has long been suggested that interpersonal connections with other community members are important, however, accounts of fans like Tomoko and Yōko show that the same holds true for fans’ individual lived experiences and emotional engagements formed independently of the fan network. By closing the distance and physical proximity to a space considered special in Takarazuka fan culture, some fans are able to not only become active agents in a shared community space, but also cultivate their personal feelings of attachment and care for said space. But how does such a sense of affect influence fans’ behaviour once they are physically within this theatre-centric urban landscape? Let us now consider fans’ theatregoing practices that are not directly connected with appreciation of Takarazuka Revue’s productions or its performers.

Fantasy strolling, embodied space, and fan-culture geography

Thus far, I have argued that the differences in individual perceptions of the Takarazuka space suggest that for some fans, the journey to the Takarazuka Grand Theatre is as important as the destination in their theatregoing experience, and that some fans can develop a deep sense of care and emotional engagement toward the space which can not only affect their perceptions but also make a lasting impact on their life choices. As discussed in the previous section, in regards to a shared fantasy of the Takarazuka space, motion and movement also appear to play a significant part in the way Takarazuka fans see the vicinity of the Grand Theatre. I have explained how, when prompted to draw boundaries of the space, fans would first identify a select few landmarks and then draw the lines while visualising the way they move through this space. While all of their sketch maps had seven commonly-shared landmarks, one may be seen as especially important in transforming the fan excursion to the Grand Theatre from a one-point itinerary to a more complex landscape-dependant experience: the hana-no-michi.

The hana-no-michi is an elevated 400-meter-long pedestrian pathway lined with cherry trees and spreading between Hankyu Takarazuka Station and the Takarazuka Grand Theatre. A naturally raised embankment of the nearby Muko River, the hana-no-michi was built in 1924 along with the construction of the Grand Theatre. Kobayashi Ichizō wanted to evoke the image of a traditional Japanese theatre’s hanamichi (i.e. a raised passage extending from the right section of the stage and running through the auditorium) to make Takarazuka Revue’s spectators’ experience even more enjoyable. However, due to being constructed outside of a theatre building, hana-no-michi’s appeal is significantly different from the form it was intended to conjure. Due to its appearance, the pathway is often likened to a sandō (a road leading to a Shinto shrine or a Buddhist temple, often elevated), showing further parallels to the idea of Takarazuka fans’ pilgrimages to a sacred place. Furthermore, unlike the original concept of hanamichi, Takarazuka’s pathway is walked on not by the performers but by the audience members themselves.Footnote17 Nevertheless, hana-no-michi is often seen as a direct passage to Takarazuka and an extension of the theatre experience.

In our conversations, many fans speak fondly of strolling along the hana-no-michi. Non-residents of Takarazuka City speak of walking along the pathway after a finished performance, enjoying seasonal flowers and chatting with their friends as they head toward the train station. Meanwhile, residents talk about taking an extended stroll to visit the site while walking their dogs, sometimes stopping briefly to observe the actresses passing nearby. Many consider it a continuation of Takarazuka’s sacred space and the “dream world” they revisit each time they see a performance at the Grand Theatre. Furthermore, walks along the hana-no-michi are usually combined with shopping or eating out at the nearby shopping mall Cerca or the department store Sorio. However, for many fans it is the simple act of passing along the pathway that appears to make their experience more memorable.

In the Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin (Citation1999) described the flâneur as a symbol of 19th century Paris urban culture and consumer capitalism. Benjamin’s flâneur was a “stroller”, a man of leisure who idly window-shopped the Parisian streets and observed the city around him. Although two centuries apart, there are certain similarities between the characteristics of the flâneur and the leisurely behaviour of some Takarazuka fans while within the Takarazuka space. We have seen how many fans choose places they have visited and have memories of as part of their Takarazuka space: the cafés and restaurants they frequent with fellow fans, the specialty shops they run errands to for the actresses, and the amusement parks they visited with their families. Although many of these establishments no longer exist, fans still hold on to the memories of them, reminiscing where they went, what or who they saw, what they ate, or what they bought while within the places they associate with the Takarazuka space. In this way, Takarazuka’s fan culture is closely linked with the city’s urban landscape and consumer behaviours of the fans, tied to their past, present, and future.

In Benjamin’s writing, the flâneur would walk aimlessly through Parisian shopping passages, but he was seen as both a type of person, an urban observer, and a lifestyle. Regardless of the fans’ spontaneity (or lack of it) in visiting the Takarazuka Grand Theatre, it is evident that while within the boundaries of the space Takarazuka fans perceive as part of the “dream world”, the act of walking, observing, and shopping are all essential elements of the fans’ experience and, as such, they are not unlike the flâneur in their awareness and appreciations of an ever-changing urban setting closely associated with local entertainment culture. The embodied act of strolling through the urban landscape surrounding the Takarazuka Grand Theatre – a symbolic and sacred space of Takarazuka fan culture – allows fans to relive their lived experiences and past memories with each step, therefore extending the assumed and imagined function of the urban development. For many local Takarazuka fans, theatregoing and other fan practices became a consumer lifestyle revolving around continuous patterns of bodily movement between their places of work and leisure.

Through its connection to the Hankyu Railway, Hankyu Takarazuka Station, the “entrance” to Takarazuka’s fantasy world and a landmark shared by all study participants, becomes a gateway to the modernised world, a hub connecting suburban communities with modernity. Analogously, hana-no-michi can be seen as the manifestation of a passage where the modern flâneur can enjoy his/her leisurely strolls while window shopping in the nearby Cerca shopping mall or SORIO department store. Takarazuka City centre is venerated as a Takarazuka “sacred site” by even those fans who have yet to visit it, yet it is also part of the wider urban space enjoyed by local residents and visitors. Both Takarazuka Station and hana-no-michi offer visitors a journey – one embarked on by boarding a train carriage, and another on the visitor’s own feet. If the flâneur personifies the urban lifestyle as he walks through the Parisian streets, Takarazuka fans can embody Japanese suburban community culture, cultivated through a century of Hankyu Railway’s developments and nurtured through decades-long theatregoing rituals – passing through space both imagined and real and bringing modernity to their everyday lives. It is then the experience through bodily movement of the space deemed sacred that offers us a glimpse into how Takarazuka fan culture evolved around fantasies surrounding a geographic location of Takarazuka City centre.

Conclusion

Even though Takarazuka fans are first and foremost theatre spectators and their levels of involvement in the Takarazuka fan network vary, many recognize the space surrounding the Takarazuka Grand Theatre as significant to the Takarazuka fan culture: the imagined core of Takarazuka fandom, the Vatican City of Takarazuka fan pilgrimages. This perception becomes especially important to local fans whose frequent interactions with this space become essential to their fan experience. To a non-fan of the Revue, the centre of Takarazuka City is simply a geographic location and part of everyday city scenery. However, shaped by personal memories, experiences, and encounters of individual fans, the same scenery transforms into a shared fantasy: a space characterised by movement, liminality, and affect. Local Takarazuka fans’ awareness of the Takarazuka space on both communal and personal levels, as well as the way in which embodied mobility becomes important to our understanding of this city landscape signifies a multi-layered fantasy, which surpasses our expectations of both “typical” theatre fans and ideas associated with geographical boundaries of an urban neighbourhood.

According to Yi-Fu Tuan, human perception of geographical localities is expressed through the use of language and signified by our individual experiences. “Place is security, space is freedom: we are attached to the one and long for the other” (Tuan [Citation1977] 2018, 3). By analysing Takarazuka fan narratives about practices expanding beyond the theatre hall, I have shown how their perceptions of the Takarazuka space illustrate an example of a spatial fantasy that is simultaneously shared among a larger fan community as commonly recognized landmarks located within Takarazuka City centre, and differentiated among these same fans whose experiences influence the way they observe and engage with said space. Although the Takarazuka space is seen as more than a physical “place” in the city landscape, it is simultaneously a location with clearly defined geographical boundaries and a “space” characterised by lived experiences and imagined fantasies of those who conjure it. These findings implicate that while Takarazuka fan culture has so far been regarded through the prism of performer/performance and performer/fan relationships, the relations and interactions of local fans with the urban space surrounding a theatre building provide insight into the way physical landscapes can influence and shape not only individual fan identities but also whole fan networks.

This recognition of the Takarazuka space as a space made significant based on individual fans’ perception offers an interesting example of how the cultural development of a city’s landscape can impact the formation of communities within the local population. The Takarazuka Revue is commonly differentiated from other Japanese theatre companies based on their gendered stage performances as well as the distinct relations between the performers and their patrons. However, examining Takarazuka Revue as more than just a theatrical performance and more than just a “place” offers a glimpse into the reasons for the unprecedented popularity of this establishment: the fantasy beyond the stage. Current debates on the formation of fan culture and fan networks tend to focus on cyberspace and often research the way fans form transnational communities in order to connect in the virtual space. However, fandom also continues to take physical and spatial forms. Thus, a study exploring the formation of fan communities which developed within simultaneously public and private urban spaces, such as Takarazuka City centre, offers new insight for the understanding of modern fan culture and the place-making processes of modern fan communities. Furthermore, while it has long been suggested that certain geographic locations may be sanctified or given symbolic significance by various fandoms, this paper offers a specific case in which the act of immersing oneself in and moving through space perceived as sacred can be seen as a significant dimension of experiencing physical space in ways that construct and intensify individual and community-based fan practices. These findings indicate that further consideration should be given to the bodily movement and mobility patterns of fans as a potential way of experiencing and producing fan culture. In other words, fan culture is not produced not only through specific acts and discourse, but also by embodied movements through space, both in the present and in one’s memories. Expanding the discussion to include embodied movement as one of the spatial dimensions of fandom contributes to our understanding of the processes behind fan community development within urban spaces and can be of broad use to studies of fan cultures and urban culture space research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Zuzanna Baraniak-Hirata

Zuzanna Baraniak-Hirata received her PhD in Anthropology and Gender Studies from Ochanomizu University, where she currently holds a post-doctoral position as a Research Fellow. She teaches courses on gender, media and Japanese society at Saitama University and the University of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo, Japan. Her research interests include Japanese popular culture, especially in relation to the intersections between gender, fan practices and consumer marketing strategies.

Notes

1 Referring to Takarazuka City centre as the sacred site of Takarazuka Revue fandom is common in the Takarazuka fan community discourse. The term was also used by seven out of eight participants of this study, confirming the prevalence of this perception even among local fans.

2 Thanks to the digitalization of media and occasional international tours, Takarazuka Revue has a considerable number of international fans, especially in East Asia. Reports of pilgrimage-like visits to the Grand Theatre are commonly found on social media related to international fans of Takarazuka, but it is unclear how widespread the image of the “sacred site” is outside of the domestic fan network.

3 Although scholars rarely discuss the differences between Takarazuka fans and there is no shared consensus in each scholar’s understanding of what constitutes the status of a “Takarazuka fan”, there is a general tendency to refer to Takarazuka fans as a group of patrons affiliated with Takarazuka actresses’ personal fan clubs. However, as I have observed more similarities than differences between fan club-affiliated and non-affiliated “regular” fans in their individual practices and everyday fan behaviours, in this article I consider all audience members who self-identify as fans to be “Takarazuka fans”.

4 At the time of the original and subsequent interviews, all interviewees were residents of Takarazuka City or the neighbouring cities of Kobe, Osaka, or Nishinomiya, with their age range varying from late 30s to early 50s. All of the eight participants (seven female and one male) chosen for the in-depth interviews have different backgrounds, personal biographies, length of experience as a Takarazuka fan (ranging from 7 to approximately 40 years), and theatregoing frequency (ranging from 1 to up to 6 viewings of each Takarazuka stage production, with approximately 30 plays performed annually).

5 Low (Citation2017) proposes the idea of embodied space as a different approach to the ethnography of place and space which analyses both the biological and experiential aspects of body in space – the individual place-making practices, as well as the personal perceptions of the material location.

6 In The Image of the City, Lynch (Citation1960) also identifies paths, edges, districts, and nodes as common elements used in navigating physical environments.

7 The map provided by the author was made based on the assumption that the term “Takarazuka space” describes a geographic area within Takarazuka City centre. Interviewees were also inquired about the possibility of “Takarazuka space” existing in other areas including the company’s second home-base theatre in Tokyo. However, the narratives were not conclusive and possibly biased. While some fans acknowledged the existence of Takarazuka space within the physical boundaries of the Tokyo Takarazuka Theatre building, others completely rejected the notion. For example, in the narrative of Mariko, a female fan in her 50s, “[Tokyo Takarazuka Theatre] is not a sacred site. … It’s not a dreamland (yume-no-kuni), it’s just an ordinary theatre.” Although beyond the scope of this study, a further inquiry into the Tokyo-based Takarazuka fan community may be necessary to gain a better understanding of the regional differences of Takarazuka fan culture in Japan.

8 The location of the Takarazuka Hotel analysed in this paper is based on its original construction placement in 1924 and actual location at the time of data collection in 2017–2018. In April 2020, the hotel was relocated to a new building next to the hana-no-michi pathway.

9 The subject of Takarazuka Revue’s formation in its first two decades has been extensively discussed by existing scholarship (see Kawasaki Citation1999; Robertson Citation1998; Watanabe Citation1999).

10 Mura as a term is often explained based on the image of Takarazuka City as part of the countryside (inaka) but is presumably more directly linked to the area’s history – being part of Kohama Village until the municipal merger of 1951. Invoking a sense of nostalgia among many of the long-term fans (ōrudo fan, lit. “old fans”), mura is often used to differentiate between Takarazuka’s two main theatres: Grand Theatre and Tokyo Takarazuka Theatre.

11 Established as a branch of Hankyu Railways, Takarazuka Revue has always had a symbiotic relationship with the company. Makiko Yamanashi (Citation2012, 51–55) describes how the Hankyu corporation (now a subsidiary of the giant Hankyu Hanshin Holdings) uses the theatre as a form of PR branding strategy. The Revue is prominently advertised on Hankyu trains and stations, department stores and leisure facilities, while Takarazuka actresses are employed to endorse the Revue’s sponsor corporations such as the Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation. Meanwhile, Hankyu utilizes the theatre’s positive image to boost sales of train tickets and link its corporate image with cultural patronage. Due to these marketing strategies, the connection between Takarazuka and Hankyu is well-known in the Kansai region.

12 All interviewee names listed in this paper are pseudonyms chosen by the participants.

13 Although recent years have seen a noticeable increase in the number of male fans of the Revue, Nori recalls that in the late 1990s, men were still a very rare sight among the overwhelmingly female audience.

14 Takarazuka Revue’s plays have been broadcast weekly as part of the Revue-dedicated programs on the Kansai Television channel from 1971 to 1995. Many fans mention having their first memories of the Revue through the weekly televised program performances.

15 Taking photos of the actresses in the stage area is one of the biggest differences between members of personal fan clubs and non-affiliated fans. As per commonly shared club rules, fan club members are not allowed to take photos or participate in irimachi or demachi for other actresses. Although greeting other actresses while waiting for their protégé is a standard practice, club members typically disperse as soon as the beneficiary actress exits the stage door area.

16 Referred to as the daihyō, the fan club leaders take the role similar to the position of a personal manager of an individual actress. The leaders manage club memberships and finances, organise fan events, and help the actress on a daily basis.

17 One of the unwritten rules among Takarazuka actresses is that they do not walk on the elevated part of the hana-no-michi but rather use the pedestrian roads on either side of it. It appears to be linked to the strict hierarchy among the actresses which begins in the Takarazuka Music School; out of respect for their superiors, it is “safer” for an actress to walk the lower road.

References

- Barrett, Maria. 2016. “Our Place: Class, the Theatre Audience and the Royal Court Liverpool.” Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Warwick.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1999. The Arcades Project. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

- Bennett, Lucy. 2014. “Tracing Textual Poachers: Reflections on the Development of Fan Studies and Digital Fandom.” Journal of Fandom Studies 2 (1): 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1386/jfs.2.1.5_1.

- Black, Rebecca W. 2008. Adolescents and Online Fan Fiction. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Boschmann, Eric E., and Emily. Cubbon. 2014. “Sketch Maps and Qualitative GIS: Using Cartographies of Individual Spatial Narratives in Geographic Research.” The Professional Geographer 66 (2): 236–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2013.781490.

- Clyde, Deirdre. 2020. “Pilgrimage and Prestige: American Anime Fans and Their Travels to Japan.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 18 (1): 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2020.1707464.

- Duffett, Mark. 2013. Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Culture. London: Bloomsbury.

- Galbraith, Patrick W. 2010. “Akihabara: Conditioning a public“otaku” Image.” Mechademia 5 (1): 210–230.

- Galbraith, Patrick W. 2019. Otaku and the Struggle for Imagination in Japan. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Grossberg, Lawrence. 1992. “Is There a Fan in the House?: The Affective Sensibility of Fandom.” In The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media, edited by Lisa Lewis, 50–65. London and New York: Routledge.

- Gubrium, Jaber F., and James A. Holstein. 2008. “Narrative Ethnography.” In Handbook of Emergent Methods, edited by S. N. Hesse-Biber and P. Leavy, 241–264. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hills, Matthew. 2002. Fan Cultures. New York and London: Routledge.

- Hills, Matthew. 2018. “Implicit Fandom in the Fields of Theatre, Art, and Literature: Studying “Fans” Beyond Fan Discourses.” In A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies, edited by Paul Booth, 495–509. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell.

- Jenkins, Henry. 1992a. “Strangers No More, We Sing’: Filking and the Social Constriction of the Science Fiction.” In The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media, edited by Lisa Lewis, 208–236. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jenkins, Henry. 1992b. Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jindra, Michael. 1994. “Star Trek Fandom as a Religious Phenomenon.” Sociology of Religion 55 (1): 27–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/3712174.

- Kawasaki, Kenko. 1999. Takarazuka: Shōhishakai-No Supekutakuru. [Takarazuka: The spectacle of consumer society]. Tokyo: Kōdansha.

- Low, Setha. 2017. Spatializing Culture. The Ethnography of Space and Place. London and New York: Routledge.

- Lynch, Kevin. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

- Margry, Peter Jan. 2008. “The Pilgrimage to Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery: The Social Construction of Sacred Space.” In Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Modern World. New Itineraries into the Sacred, edited by Peter Jan Margry, 143–172. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- McCormick, Casey J. 2018. “Active Fandom: Labor and Love in the Whedonverse.” In A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies, edited by Paul Booth, 369–384. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell.

- Miyamoto, Naomi. 2011. Takarazuka fan-no shakaigaku: Sutaa-wa gekijō-no soto de tsukurareru [Takarazuka Fan Sociology: Creating the Stars Outside of the Theatre Hall]. Tokyo: Seikyūsha.

- Morikawa, Kaichiro. 2012. “Otaku and the City: The Rebirth of Akihabara.” In Fandom Unbound, 133–157. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Morishita, Nobuo. 2015. Takarazuka no keiei senryaku [Takarazuka’s marketing strategies]. Tokyo: Kadokawa.

- Nakamura, Karen, and Hisako. Matsuo. 2003. “Female Masculinity and Fantasy Spaces: Transcending Genders in the Takarazuka Theatre and Japanese Popular Culture.” In Men and Masculinities in Contemporary Japan: Dislocating the Salaryman Doxa, edited by J. E. Roberson and N. Suzuki, 59–76. London and New York: Routledge Curzon.

- Relph, Edward. 1976. Place and Placelessness. London: Pion.

- Robertson, Jennifer. 1998. Takarazuka: Sexual Politics and Popular Culture in Modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Rodman, Gilbert B. 2013. Elvis After Elvis: The Posthumous Career of a Living Legend. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sabre, Clothilde. 2017. “French Anime and Manga Fans in Japan: Pop Culture Tourism, Media Pilgrimage, Imaginary.” International Journal of Contents Tourism (1): 1–19.

- Sandvoss, Cornel. 2005. Fans: The Mirror of Consumption. Cambridge: Polity.

- Stickland, Leonie. 2008. Gender Gymnastics: Performing and Consuming Japan’s Takarazuka Revue. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press.

- Till, Rupert. 2010. Pop Cult: Religion and Popular Music. London and New York: Continuum.

- Toda, Kiyoko. 2009. “Hanshinkan modanizumu-no keisei to chiiki bunka-no sōzō [The Making of Hanshinkan Modernism and the Creation of Regional Culture].” Nara Prefectural University Kenkyukiho 19 (4): 49–77.

- Tsuganesawa, Toshihiro. 1991. Takarazuka senryaku [Takarazuka strategies]. Tokyo: Kōdansha gendai shokan.

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. 1977. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Turner, Victor. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Tzanelli, Rodanthi. 2004. “Constructing the ‘Cinematic tourist’: The ‘Sign industry’ of the Lord of the Rings.” Tourist Studies 4 (1): 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797604053077.

- Wada, Matsuo, Ed. 2015. Takarazuka fan kara yomitoku chōkōkan’yoshōhisha-e-no maaketingu [Marketing for Ultra-High Involvement Consumers Based on Analysis of Takarazuka Fans]. Tokyo: Yūhikaku.

- Watanabe, Hiroshi. 1999. Takarazuka kageki-no henyō to nihon kindai [The Transformation of Takarazuka in the Midst of Modernization Process of Japan]. Tokyo: Shinshokan.

- Williams, Rebecca. 2018. “Fan Pilgrimage & Tourism.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom, edited byMelissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott, 98–106. London and New York: Routledge.

- Yamanashi, Makiko. 2012. A History of the Takarazuka Revue Since 1914: Modernity, Girls’ Culture, Japan Pop. Kent: Global Oriental.

- Yokomichi, Kiyotaka. 2007. The Development of Municipal Mergers in Japan. Tokyo: Council of Local Authorities for International Relations.