ABSTRACT

Teachers’ language ideologies shape their classroom language policy-making, which in turn shapes students’ opportunities to learn. Attention to language ideologies is therefore critical for teacher educators who seek to support pre- and in-service teachers in becoming pro-multilingual policymakers. This mixed methods, survey-based study explores the language ideologies and hypothetical policy-making of 134 pre- and in-service teachers at a large public university in Arizona. It employs decision tree models to examine connections between participants’ demographics, their language ideologies, and their hypothetical policymaking around Spanish-English dual-language bilingual education (DLBE). Findings show intersections between current and future educators’: (a) contextualized experiences, (b) ability to discuss DLBE accurately (without misunderstandings), and (c) ability to engage concretely with details of hypothetical policy making around DLBE. The study offers a unique vantage point from which to consider how pre- and in-service teacher education can inform teachers’ accurate understandings of DLBE/multilingualism, language ideological stances, and stances toward linguistic diversity.

Introduction

All language users hold beliefs about how language works and should be used (Irvine, Citation1989; Silverstein, Citation1979). Whether conscious or not, these language ideologies (Kroskrity, Citation2010) guide individuals’ own language use and their perceptions of others’ language practices. Teachers are no exception and, like other rule-makers (e.g., legislators, CEOs, parents), are in positions to impose their language ideologies on others through the creation of classroom language policies (Johnson, Citation2010). Teachers may be asked to implement macro-level, official language policies from school/district leadership or local or national governments (e.g., structured English immersion in Arizona), and teachers also create policies through their day-to-day classroom decision-making (Hornberger & Johnson, Citation2007). Teachers’ own experience and beliefs, including language ideologies, can guide these language policy decisions.

Teachers’ language policy decisions are important because they influence students’ language use, opportunities to learn, and learning outcomes (Godley, Reaser, & Moore, Citation2015; Vasquez-Montilla, Just, & Triscari, Citation2014). When teachers understand and value linguistic diversity, multilingual students are better supported, for instance, through being able to express themselves in multiple languages (Deroo & Ponzio, Citation2019). When teachers do not understand or value students’ home languages, differences can be mistaken for deficits, and students whose linguistic repertoires differ from their teachers’ can suffer negative consequences (e.g., Martinez & Martínez, Citation2017). Importantly, however, educational experiences such as training in cultural diversity or teaching linguistically diverse students have the potential to reshape teacher ideologies (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Palmer, & Henderson, Citation2017; Vasquez-Montilla et al., Citation2014). Thus, to prepare teachers to work in classrooms where cultural and linguistic diversity are the norm, it is imperative to understand their language ideologies and to find ways to shape those ideologies so that multilingual students, families, and communities are understood and supported (García & Guerra, Citation2004).

In this study, we examine the language ideologies of 134 pre- and in-service teachers enrolled in teacher education or continuing education programs at a large public university in Arizona. Participants completed a survey that included demographic and teaching/coursework experience questions along with two previously validated scales meant to evaluate attitudes and beliefsFootnote1 about linguistic diversity and language learning (see Methods). To understand participants’ hypothetical policymaking, the survey also included one question prompting a Likert-scale agreement about whether a (hypothetical) school should convert to a Spanish-English dual-language bilingual educationFootnote2 (DLBE) model. That question was followed with an open-ended item prompting participants to explain their policy decision, allowing us to examine the ways that ideologies mediated that policy choice. Through a complementary, transformative mixed methods approach (Creswell & Plano-Clark, Citation2010; Greene, Caracelli, & Graham, Citation1989), we explore connections between participants’ demographics, their language ideologies, and their hypothetical policymaking around language through both (a) concurrent, separate quantitative and qualitative analyses and (b) mixing methods during analysis (see research questions below and methods section for further details).

Theoretical framework

We draw here on the theoretical lenses of (a) language ideologies and (b) language policy and planning (LPP). Our understanding of language ideologies originates in Silverstein’s (Citation1979) work, in which he defined “linguistic ideologies” as “any sets of beliefs about language articulated by the users as a rationalization or justification of perceived language structure and use” (p. 193). His ideas were expanded by Gal (Citation1989) and Irvine (Citation1989) who showed that language ideologies are intertwined with political and moral interests and that they are not individual and ad hoc, but rather culturally learned and shared. A more recent, elaborated theorization of language ideologies comes from Kroskrity (Citation2010), who defined language ideologies as

beliefs, feelings, and conceptions about language structure and use which often index the political economic interests of individual speakers, ethnic and other interest groups, and nation states. These conceptions, whether explicitly articulated or embodied in communicative practice, represent incomplete, or ‘partially successful’, attempts to rationalize language usage; such rationalizations are typically multiple, context-bound, and necessarily constructed from the sociocultural experience of the speaker. (p. 192)

It is this definition that we draw on in our work.

Additionally, we draw on a language policy and planning (LPP) framework. This perspective holds that language policy is always made at multiple scales – e.g., from state legislatures to peer interactions – and that implementation always involves interpretation, thus creating opportunities for actors like principals, teachers, and parents to function as policy makers (Hornberger & Johnson, Citation2007). While policy is often understood by the public as explicit, codified rules created by a legislative body, an LPP perspective posits that policies can also be implicit, unstated, and comprised of day-to-day language practices (e.g., reminders by teachers to say “isn’t” rather than “ain’t”; the (un)welcoming of students’ home languages in the classroom; Hornberger & Johnson, Citation2007). Even in cases where state-wide or school-wide language policies are in place, enacting those policies at the classroom level involves “creative processes of interpretation and recontextualization,” opening up spaces for enforcement, subversion, or even outright resistance (Ball, Maguire, & Braun, Citation2012, p. 3; McCarty, Citation2011). These enactments are mediated by context and culture as well as teachers’ own perspectives (Johnson, Citation2010). In this way, language ideologies are an inherent part of policy-making. When a person or group imposes their views about language onto others, language policy is born (Shohamy, Citation2006).

Literature review

Teachers as classroom policy makers: how do ideologies shape practice?

As the adults who most directly influence classroom practices, teachers are critical language policy-makers, and their language ideologies can shape those policies in significant ways. Henderson (Citation2017) put it bluntly: “Language ideologies mediate language policy” (p. 31). In Stritikus and Garcia’s (Citation2003) examination of how California teachers implemented state-level English-only language policies (Prop 227), for instance, they found that teachers with additive beliefs about bilingualism openly resisted the mandates of Prop 227, creating multilingual classroom policy through classroom practices such as drawing on Spanish and connecting to students’ cultural knowledge. Conversely, subtractive views of bilingualism (views of Spanish as a hindrance and English as a path to student success) led to strict enactment of Prop 227 and a curtailment of all Spanish classroom practices. Similarly, Razfar and Rumenapp (Citation2012) found that California English language arts teachers who ascribed to monolingual, English-oriented ideologies created classrooms that upheld those views through classroom policy-making, for instance using the name “English class” to justify limiting the use of students’ full linguistic repertoires (see also Godley et al., Citation2015; Lew & Siffrinn, Citation2019). Pluralist and pro-multilingual ideologies can lead teachers to do the opposite, resisting deficit views and overcoming contextual constraints. For example, Newcomer and Puzio (Citation2016) show how teachers and their principal at one Arizona school were able to create a school environment that welcomed multilingual families, even in the face of state-level English-only policies.

Teacher ideologies are just as powerful for informing classroom language policy in DLBE programs. Zúñiga, Henderson, and Palmer (Citation2018) showed how two Spanish-English DLBE teachers in the same district held contrasting perspectives about what kinds of language experiences would best support their Spanish-dominant students. These views resulted in vastly different classroom language policies, with one teacher upholding DLBE principles and the other effectively dismantling the program. Henderson (Citation2017) illustrated how two teachers’ plurilingual ideologies led them to enact classroom language policies in their Spanish-English DLBE classrooms that countered district policies of strict language separation and transition toward English in third grade. Yet, she also found that, in some ways, the teachers’ ability to create policy was constrained by school- and district-level initiatives such as monolingual standardized testing and English-mostly instruction in upper elementary grades. Indeed, other scholars have shown that ideologies may not always translate into practice due to contextual features, such as content area, practicality, and local policy (Chang-Bacon, Citation2020). Even when teachers express pro-multilingual ideologies, they may still feel constrained by dominant school language narratives or by practical concerns, like a lack of multilingual materials (Bernstein et al., Citation2021a; Metz, Citation2019). Further, transforming asset-oriented ideological commitments into action can be stymied by the prevalence of deficit views at both school and community levels (García & Guerra, Citation2004). It is therefore critical to understand the contexts in which teacher ideologies form and how those ideologies interact with the larger policyscape (Mettler, Citation2016).

What shapes teacher language ideologies?

Studies of in-service teachers point to particular experiences that can shape language ideologies. For instance, teachers who are multilingual (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Citation2014) or who have their own language learning experience (Chang-Bacon, Citation2020) have been found to react more positively toward their students’ multilingualism. Other studies have highlighted teachers’ geography and surrounding community as a factor. In Byrnes, Kiger, and Manning (Citation1997) work, teachers who lived in more linguistically-diverse areas had more positive views of multilingualism. Similarly, Deroo and Ponzio (Citation2019) found families, and communities, and general political climate to all influence teacher language ideologies. For in-service teachers, scholars have found increased age to be associated with more positive views of linguistic diversity (e.g., Anderson, Ambroso, Cruz, Zuiker, & Martinez-Rodriguez, Citation2022). Yet, several studies have also found a correlation between increased years of teaching and decreased positive stances toward multilingualism, either through comments (Bernstein et al., Citation2021a) or agreement/disagreement with Likert-scale items about multilingualism (Metz, Citation2019).

Many studies also suggest, however, that education can temper negative stances and positively shape teacher ideologies regarding multilingualism and multilingual learners (e.g., Byrnes et al., Citation1997; Fitzsimmons-Doolan et al., Citation2017; Pettit, Citation2011; Vasquez-Montilla et al., Citation2014). Bernstein et al. (Citation2021a) found that preschool teachers who held a bachelor’s degree or higher showed more pro-multilingual ideologies. Park-Johnson (Citation2020) found that coursework in supporting language learners or experience with multilingual students significantly predicted participants’ positive views toward translanguaging. Conversely, a lack of coursework or experience with linguistic diversity can lead to misunderstandings about linguistically diverse students’ language learning and needs (Reeves, Citation2006). Importantly, scholars have shown that language ideologies can be resistant to change (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Citation2018) and that pedagogical knowledge about how language works is not enough to change teacher language ideologies (e.g., Chang-Bacon, Citation2020). However, others point to practices that may hold promise for such change, including: naming language ideologies and describing how they inform narratives about learners (Henderson, Citation2017); situating understandings of language and its use sociopolitically (Dávila, Citation2016); and reflection on one’s own language use and experience (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Citation2018).

Methods

As Henderson (Citation2017) argued, it is critical to understand how teachers’ own language ideologies interact with societal or institutional ideologies to mediate classroom language policy, as this enactment has consequences for students’ experiences and trajectories. We seek here to understand pre- and in-service teachers’ language ideologies and to add evidence to the body of work on how teachers’ demographics and prior experiences might shape those ideologies. Additionally, using an innovative hypothetical policymaking prompt that allows us to examine teachers’ policy-making process, we aim to understand how teachers’ ideologies mediate language policies, particularly regarding DLBE. We asked the following research questions:

How do participants’ demographic characteristics relate to:

their language ideologies? (Quantitative)

a hypothetical policy decision (i.e., how strongly they support a proposed new DLBE program)? (Quantitative)

What are participants’ reasons for their hypothetical policy decision and how do these demonstrate language ideologies mediating DLBE policy making? (Qualitative)

How do participants’ reasons for/against the new DLBE program relate to:

their hypothetical policy decision (i.e., how strongly they support a proposed new DLBE program) (Mixed)

their language ideologies? (Mixed)

Arizona policy context

To understand our participants and their hypothetical policymaking, it is necessary to keep our context in mind. Arizona has always been a multilingual state (including English, Spanish, and more than 12 indigenous languages, such as Diné Bazaad (Navajo), Piipaash, Yaqui, and O’odham). Yet, in its official language policies, Arizona leans pro-monolingual (Heineke, Citation2017). Voters approved English as Arizona’s official language in 1988 and again in 2006. In 2000, Arizona also instituted some of the most restrictive anti-bilingual education laws in the United States (Proposition 203, Citation2000), excluding students not yet proficient in English from bilingual programsFootnote3 and remanding English-learning (emergent bilingual) students to English-only, Structured English Immersion (SEI) classrooms for four hours a day (Arizona House Bill 2064, Citation2006). Among the effects of the SEI policy were low graduation rates for English learners (17% in 2017 compared to 86% for other students; Jung, Citation2017), segregation, lack of access to content classes, missed opportunities to develop Spanish, and often, a loss of Spanish proficiency (Lillie & Markos, Citation2014). The policy also had the unintended but no less destructive consequence of undermining K-12 indigenous language revitalization programs (Combs & Nicholas, Citation2012).

The law was softened in 2019, requiring just two hours per day of SEI and allowing those two hours to take place in 50–50 dual language bilingual programs, thus re-opening DLBE programs to emergent bilingual students (Kaveh, Bernstein, Cervantes-Soon, Rodriguez-Martinez, & Mohamed, Citation2021). DLBE programs have also been expanding in Arizona (duallanguageschools.org, Citationn.d.; TL3C., Citation2014]), particularly as districts are pressed to offer specialty programs to attract families in the context of school choice (Bernstein, Alvarez, Chaparro, & Henderson, Citation2021b). Yet, the legacy of restrictive policy remains. Perceptions among teachers endure that Arizona is an “English-only state” (Fredricks & Warriner, Citation2016) and that bilingual education could be a detriment to their Spanish-speaking students (Bernstein et al., Citation2021a). Twenty years of restrictive policy have also resulted in a “lost generation” of Arizona students who started school as Spanish-dominant and missed the opportunity to become biliterate and bilingual (Lillie, Citation2016), contributing to the current shortage of teachers who have the language skills to become certified to teach bilingually in the growing number of DLBE schools in the state.

Participants

It is within that Arizona context that most of our participants (77.6%) grew up, live, study, and work. Participants in our study were either (a) pre-service teachers currently enrolled in face-to-face teacher preparation programs (n = 96, 71.8%) here in Arizona or (b) students enrolled in online Master’s courses in ESL or TESOL (n = 38, 28.2%), including second career and practicing teachers, living across the US and abroad (see Appendix B for full demographics). In line with many teacher education programs, the majority of participants identified as female (n = 118, 88.1%). and white (n = 87, 64%). A significant minority identified as LatineFootnote4/Hispanic (n = 31, 23.1%), and just under half of the participants (n = 54, 40.3%) indicated that they had teaching experience in formal P-16 settings. Lastly, 43 (32.1%) of our participants identified as multilingual, with 26 (19.4%) having grown up multilingual, seven (5.2%) becoming multilingual through study, and 10 (7.5%) not indicating a path to multilingualism in the survey.

Data collection and survey instrument

Students were invited to participate by e-mail and were offered a $10 gift card to complete the online survey. The survey – the Measure Of Teacher Language Ideologies + Hypothetical Policy Making Question (or the “MOTLI+”) – consisted of three sections: (a) demographics and experiences, (b) language ideologies, and (c) hypothetical language policymaking.

Demographics questions

Demographic items reflected characteristics that scholars have found relevant to language ideology formation: languages and contexts of use/acquisition, academic program, teaching experience, residence, age, and international experience. We also elicited gender identification (male, female, non-binary/other) and racial identification (with option to select multiple).

Language ideologies questions

To measure language ideologies, the survey included 44 Likert-scale items from two previously validated instruments: the Language Attitudes of Teachers Scale (LATS; Byrnes & Kiger, Citation1994) and the Language Beliefs Survey (LBS; Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Citation2014) (see Appendix A for both sets of items). We chose these instruments as they are commonly used in studies of educators’ language ideologies (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2022; Bernstein et al., Citation2021a; Vasquez-Montilla et al., Citation2014), and both were developed, at least in part, in Arizona.

Language Attitudes of Teachers Scale (LATS)

The LATS (Byrnes & Kiger, Citation1994) includes 13 items that prompt relative agreement/disagreement with statements about three constructs: language politics, tolerance of linguistic diversity, and classroom language support. The LATS was developed with pre-service teachers from Arizona, Utah, and Virginia. In this study, we scored LATS items so that higher numbers indicate more positive attitudes toward linguistic diversity/support for language learning (4 = strongly disagree, 3 = disagree, 2 = uncertain, 1 = agree, 0 = strongly agree). For scoring, we summed each participant’s responses to all 13 items to indicate a total score for each participant, with higher scores indicating relatively more positive attitudes toward linguistic diversity/language support than lower scores (Byrnes & Kiger, Citation1994). Scores were approximately normally distributed (x = 37.27, SD = 6.91, Min = 18, Max = 51), and we calculated an alpha coefficient of .78 indicating acceptable fit.

The Language Beliefs Survey (LBS)

The LBS is a 31-item survey developed by Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Citation2014) through a review of research on language ideologies in the US. It presents statements with which participants can agree to varying degrees. Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Citation2014) first administered it to 1294 Arizona voters, including teachers, identifying five underlying factors (). We used this factor structure in our analysis, because of our relatively small sample size and because our sample closely matches Fitzsimmons-Doolan’s teacher participants. We calculated a coefficient alpha for each factor, finding all but one acceptable. For scoring, we used average summed factor scores for the highly loading items, resulting in results that to correspond to the 6-point Likert-scale questions (5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = somewhat agree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 1 = disagree, 0 = strongly disagree). Thus, each participant, for each factor on the LBS, received a score between 0 and 5.

Table 1. LBS Factors identified by Fitzsimmons-Doolan (Citation2014).

Relationship between LATS and LBS

As a first check of criterion-related validity, we examined the relationship between the LATS and the LBS, expecting participants’ LATS total score to correlate significantly with each of their LBS factors scores. We found that all but one of the five LBS factors correlated with the LATS total score, and that those four relationships were in the expected direction (e.g., LATS correlated positively with “Pro-Multilingualism” and negatively with “Multiple Languages as a Problem” and “Pro-Monolingualism”) (see , bold values). We also assessed correlations with individual LATS constructs (, values not in bold), but considering the relatively equivalent directions and magnitude of the correlations, we used the LATS total for subsequent analyses to reduce unnecessary complexity.

Table 2. Correlation between LATS and LBS.

Hypothetical language policymaking question

Our survey concluded with a prompt asking participants to engage in hypothetical policymaking. It read:

We are working with a school district on their language programming for elementary students. They are considering converting one of their elementary schools into a dual language bilingual elementary school. This would mean that all kindergartners would begin with 90% of their class time in Spanish and 10% in English. Over the course of elementary school, this would taper to 50% of class time in Spanish and 50% in English. The school is looking for feedback from the community, including educators and future educators, about this decision. Please indicate below whether you think the school should make the switch to a dual language bilingual school. Please share the reasons for your recommendation about the school switching or not. Are there any other things you think the district, school, or leaders should consider?

Participants indicated their hypothetical policy decision on a scale of 0 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). They then wrote a free response explaining their decision – i.e., providing insight into how language ideologies mediate policymaking.

Quantitative analysis

To answer RQs 1 and 3, we used a decision tree approach (Breiman, Friedman, Olshen, & Stone, Citation1984)— a type of machine learning that shows how multiple, interrelated independent variables, like demographics, relate to one dependent variable, like LATS scores. Decision trees are created through an algorithm that takes the set of independent variables and makes each branch in the tree by finding the one independent variable that best splits the data into the two, most tightly homogenous groups (Therneau & Atkinson, Citation1997). It does this by finding the sum of squared errors (SSE) between the predicted values and actual values, then choosing the split that produces the smallest SSE. After the first split, this process is applied separately to each sub-group, splitting the data set repeatedly until non significant improvement can be made or the sets reach a minimum size (Therneau & Atkinson, Citation1997). Decision trees are a highly interpretable type of machine learning (Gomes & Almeida, Citation2017) and offer greater interpretability than regression models, which can have multicollinearity issues among independent variables, obscuring the magnitude and direction of relationships.Footnote5

Employing rpart software (Breiman et al., Citation1984), we used decision trees to examine the relationships between participants’: (a) language ideologies and demographic characteristics, (b) language ideologies and DLBE support, (c) reasons provided on the open ended items and their level of DLBE support, and (d) reasons and their language ideologies. We ran a total of eight models, using LATS total score, LBS Pro-Multilingualism score, LBS Pro-Monolingualism score, and support for DLBE as dependent variables. We used demographic variables (e.g., age, teaching experience) as independent variables in one set of trees; in the second set, we used reasons for/against DLBE support (e.g., “DLBE is a good way to learn language”) as independent variables. The models illustrate two important pieces of information: (a) which independent variables are relatively more discriminatory (i.e., best split the data into the two most tightly homogenous groups); and (b) what the average dependent variables are for each subgroup.

Qualitative analysis

To analyze the open-ended survey item and the way language ideologies mediate participants’ policy decisions, we engaged in multiple rounds of emergent, collaborative coding (Saldaña, Citation2021). We read through participants’ open-ended responses, sensitizing ourselves to:

who the assumed population was (e.g., English speakers, Latine students, all students)

the value associated with DLBE (good, bad, conditional)

the reason, or justification, for that value

We took a grounded approach,Footnote6 using participants’ own words for initial coding. We grouped these into codes and subcodes, accounting for all open-ended responses (see Appendix C for code book and examples). Three authors independently coded each response, then met to come to consensus. The initial level of complete agreement (all codes between all coders matching) was 56.7%. But in 100% of cases, at least two of three coders agreed and we used those codes.

Mixed methods approach

In this study we mix methods for the purpose of achieving complementarity (Greene et al., Citation1989) through a data transformation model, which entails mixing multiple forms of data during analysis (Creswell & Plano-Clark, Citation2010. As Riazi and Candlin (Citation2014) note, “Complementarity is best achieved by carrying out each method interactively/ interdependently and concurrently, to cast as much light as possible on the complexity of the research at issue” (p. 144). Language ideologies, and how they might be surmised through responses to our forms of data, are notably complex (Anderson et al., Citation2022; Chang-Bacon, Citation2020; Razfar & Rumenapp, Citation2012), and as such benefit from the illumination of multiple angles offered by the complementary use of mixed methods. Our use of qualitative interpretive coding of open-ended responses and machine learning decision tree modeling, both separately and in combination, helps us to achieve those ends.

Findings

RQ1a: How do participants’ demographic characteristics relate to their language ideologies?

We address this question through quantitative analysis, specifically decision tree models relating LATS/LBS responses [DV] with demographics [IV]). We operationalized language ideologies in three ways:

total LATS scores (which captures stancesFootnote7 toward and support of linguistic diversity, language learners, and language learning)

LBS Pro-Multilingualism factor score (which captures relative agreement with the view that multilingualism is useful, important, and positive)

LBS Pro-Monolingualism factor score (which captures relative agreement with the view that English is useful and important, particularly in its correct form)

Of the LBS factors, we use Pro-Multilingualism and Pro-Monolingualism as they: (a) are most relevant to our research questions, (b) have the highest correlation with the LATS, and (c) have the most items in each factor (eight), meaning wider variation in scores. Each dependent variable is given its own decision tree. We offer a discussion across trees at the end of RQ1.

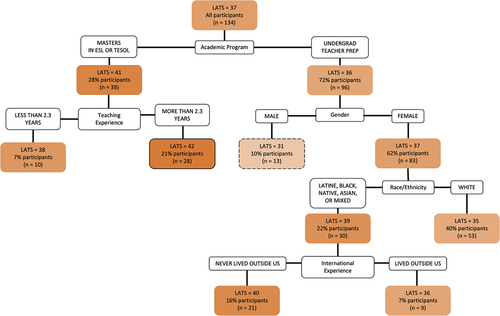

Demographics and LATS scores

The decision tree in shows how participants’ demographic characteristics relate to their total LATS score. Each branch in the tree highlights the demographic variable that creates the biggest split between participants, based on LATS scores. Recall that a higher LATS score indicates a more positive stance toward linguistic diversity and language learners/learning.

Figure 1. Decision tree model of how demographic characteristics related to LATS scores. Note: Darker shading = higher score; solid border = highest score; dashed outline = lowest score). Scores shown are the average total LATS score for each subgroup, with higher scores indicating relatively more positive attitudes toward linguistic diversity/language support than lower scores (Byrnes & Kiger, Citation1994).

In this tree, the initial explanatory variable is Academic Program (i.e., being in an undergraduate teacher preparation program vs a Master’s degree program). Master’s students averaged higher LATS scores, and those with 2.3+ years of teaching experience scored highest (42 [of a possible 52]; see box with solid border). In stark contrast, undergraduates in teacher preparation programs who identified as maleFootnote8 scored 31, on average (box with dashed border).

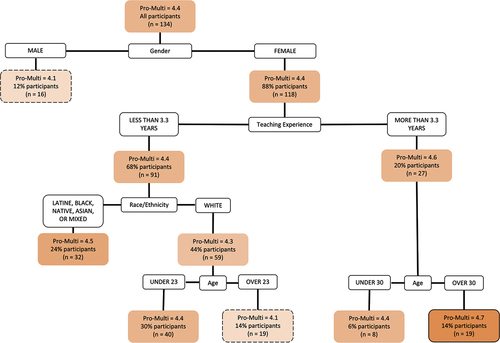

Demographics and LBS Pro-multilingualism scores

The second decision tree () illustrates how participants’ demographics related to their LBS Pro-Multilingualism factor scores (second indicator of language ideologies). Again, an important explanatory variable for this model was gender, with female participants averaging Pro-Multilingualism scores of 4.4 (between “strongly agree” and “agree”) and male participants averaging 4.1 (more or less, “agree”). Among the 118 female participants, those with the highest Pro-Multilingualism scores (4.7) had more than 3.3 years’ teaching experience and were over age 30. Females with the lowest Pro-Multilingualism scores (4.1) had less than 3.3 years’ teaching experience, identified as white, and were over age 23. We were pleased to note, however, that scores only ranged from 4.1 to 4.7, indicating that participants generally agreed with the Pro-Multilingualism statements in the LBS.

Figure 2. Decision tree model of how demographics related to LBS Pro-Multilingualism scores (Note: Darker shading = higher score; solid border = highest score; dashed outline = lowest score). Participants responded to the 6-point Likert-scale questions (5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = somewhat agree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 1 = disagree, 0 = strongly disagree). A score of 4.7 shows that the subgroup averages a score between agree strongly agree.

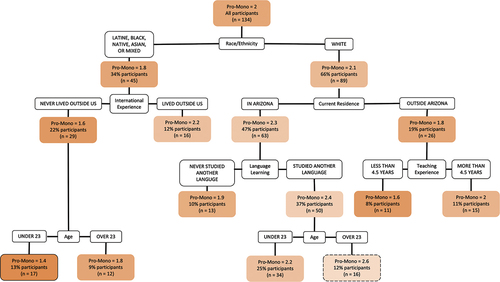

Demographics and LBS Pro-monolingualism scores

Our third decision tree model () shows how participants’ demographics relate to their LBS Pro-Monolingualism scores (the third indicator of language ideologies). Recall that higher Pro-Monolingualism factor scores indicate stronger agreement with statements about the importance of English. The most important explanatory factor here was racial identification, with white participants disagreeing less with Pro-Monolingual statements (average of 2.1 – “somewhat disagree”) than participants of color (1.8 – between disagree and “somewhat disagree”). White participants outside Arizona more similar to participants of color (1.8), while living in Arizona increased Pro-Monolingualism scores among white participants (2.3). It is worth, however, that even the participants with the highest Pro-Monolingualism scores – white participants living in Arizona who had studied another language and were over age 23 – averaged 2.6 (between “somewhat disagree” and “somewhat agree”). These scores were only 1.2 points away from participants’ with the lowest Pro-Monolingualism scores – participants of color who had never lived outside the US and were over age 23 – who averaged 1.4 (between “disagree” and “somewhat disagree”). Thus, all participants fell in the “disagree” range on these items.

Figure 3. Decision tree model of how demographic characteristics relate to LBS Pro-Monolingualism scores (note that shading and borders are reversed here, so that darker still indicates a more positive stance toward linguistic diversity). Participants responded to the 6-point Likert-scale questions (5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = somewhat agree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 1 = disagree, and 0 = strongly disagree). A score of 2.2 shows that the subgroup averages a score between somewhat disagree and somewhat agree.

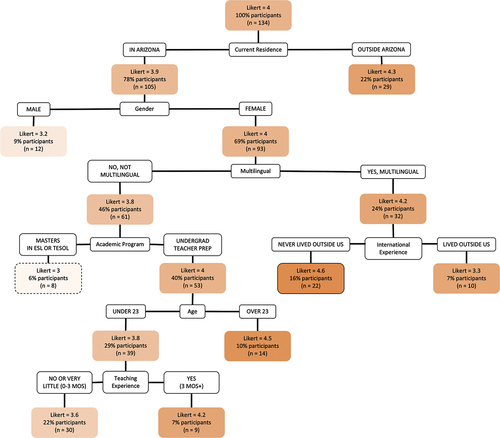

RQ1b: How do participants’ demographic characteristics relate to a hypothetical policy decision (i.e., how strongly they support a proposed new DLBE program)?

We address this question through quantitative analysis, specifically a decision tree relating DLBE support Likert-response [DV] with demographics [IV]. shows how demographics related to Likert scores on the question of support for a new DLBE program.

Figure 4. Decision tree model of how demographic characteristics relate to DLBE support. Note: Darker shading = higher score; solid border = highest score; dashed outline = lowest score. Participants responded to the 6-point Likert-scale questions (5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = somewhat agree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 1 = disagree, and 0 = strongly disagree). A score of 3.6 shows that the subgroup averages a score between somewhat agree and agree.

We found here that living in Arizona was the first salient demographic characteristic: participants outside Arizona more strongly supported the new DLBE program (4.3, between “agree” and “strongly agree”) than those in Arizona (3.9, “agree” leaning slightly toward “somewhat agree”). Among participants in Arizona, females supported DLBE more strongly (4, “agree”) than males (3.2, “somewhat agree” leaning toward “agree”). Among Arizona females, identifying as multilingual (4.2) versus monolingual (3.6) was an important distinguishing characteristic. In fact, multilingual females living in Arizona that had not lived abroad indicated the highest support for DLBE among all participants (4.6 between “strongly agree” and “agree”).

RQ1: Summary and discussion

The first three decision trees addressing RQ1 () highlight connections between participants’ demographic characteristics and their language ideologies. The fourth tree shows connections between participants’ demographic characteristics and their policy decision of whether to implement a (hypothetical) new DLBE program. Looking across these four models points to an important confluence of teaching experience, program/age, race, and geography explaining both language ideologies (LATS, Pro-Monolingual, Pro-Multilingual) and DLBE support (hypothetical policy decision item). summarizes how these demographic variables related to each dependent variable.

Table 3. Demographic variables that lead to increased scores on language ideologies measures (RQ 1a) and support for DLBE (RQ 1b).

Together, the trees summarized in echo prior studies’ findings that some teaching experience is associated with more positive stances toward linguistic diversity (Park-Johnson, Citation2020). Participants with more than 2.3 years of teaching experience scored highest on the LATS than those with less experience, and those with 3.3 years’ experience scored higher on the LBS Pro-Monolingualism factor than those with less. However, Decision Tree 3 also echoes past findings that more teaching experience leads to more emphasis on the importance of English (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2022; Metz, Citation2019). In our sample, white participants living outside AZ having more than 4.5 years of teaching experience agreed more strongly with Pro-Monolingualism statements than those with fewer than 4.5 years of experience.

The finding that participants of color showed more Pro-Multilingual stances also aligns with past research suggesting that experience with diversity is an important shaper of stance toward linguistic diversity (Lew & Siffrinn, Citation2019). Additionally, in our sample the majority of participants of color identified as Latine or mixed-Latine (36% of total participants; 78% of participants of color). While not all Latine people in Arizona are multilingual – indeed just 50% in our sample identified as multilingual – the majority of Latine speakers that we teach do come from families that are multilingual – from cousins in Mexico to Spanish-dominant grandparents in the house to parents who are bilingual to older siblings that translanguage. While past research has shown that multilingual people are more likely to embrace multilingual beliefs (Fitzsimmons-Doolan, Citation2014), we think it might be worth investigating whether being part of multilingual communities or families shapes language ideologies as well.

Geography was also important for explaining beliefs, as well as hypothetical policy-making. For white participants, living in Arizona – a state with a history of restrictive language education policies (Heineke, Citation2017) – was associated with less strong disagreement on Pro-Monolingual statements (). In other words, although white Arizonans fell in the “somewhat disagree” to “somewhat agree” range (2.3), they disagreed less than Arizonans of color or white participants outside Arizona (1.8). Interestingly, white participants in Arizona who had studied another language had higher Pro-Monolingual scores (2.4) than those who had not (1.9). This contradicts findings from other scholars that language study increases positive stances toward multilingualism (e.g., Chang-Bacon, Citation2020). However, these participants did not necessarily identify as multilingual, just that they had studied another language. Perhaps experiences with L2 learning that feel frustrating or unsuccessful could lead participants to think that bilingualism is difficult or unimportant. Yet, a more compelling explanation may be that language learning intersects in important ways with racial identification and geography. For instance, we might ask: What is it about learning Spanish in Arizona as a white person that can lead to negative feelings about multilingualism? Is this different from learning Japanese in Arizona? Or Spanish in New Mexico? The use of decision trees, rather than statistical tests that examine each variable in isolation, suggests that experiences may intersect in more complex ways that prior studies have been able to show. We encourage further work exploring the kinds of experiences with language that various participants have had in various contexts, rather than just whether or not they had language-learning experience.

Similar patterns – geography intersecting with language experience – emerged in how demographics related to hypothetical policy decisions, operationalized as level of support for a new DLBE program (RQ1b). Living in Arizona proved to be the first important predictor, with those outside of Arizona indicating stronger support for DLBE. Yet, within Arizona, multilingual participants showed almost as strong support (see ). In our experience, multilingual students from Arizona often arrive in our classes already possessing a critical awareness about linguistic hierarchies in Arizona and the US more broadly. Many also have intense pride in their heritage but concerns about their own home language proficiency, concerns which may not exist had they been afforded the opportunity to develop their heritage language through DLBE. Conversely, we suspect that growing up as an English speaker in Arizona, particularly during the early Prop 203/SEI years, could result in suspicion toward bilingual programs, if only for their lack of familiarity. This would follow a similar pattern to findings about pre-service teachers who grew up under California’s English-only laws (Garrity, Aquino-Sterling, Van Liew, & Day, Citation2018), and it reflects the utility of examining how demographics and experiences intersect to shape language ideologies.

These findings also point to one of the key advantages of decision trees: “It can happen that no predictor on its own is significant, whereas all predictors jointly are successful in explaining a significant part of the variance in the response” (Tomaschek, Lanfer, Melzer, Debitz, & Buruck, Citation2018, p. 249). In Tree 4, the biggest possible split along a single demographic variable only accounts for a difference of .4 on the Likert-scale (in Trees 2 and 3, this initial split is even less). It takes comparing further points along multiple branches to identify greater points of diversity. The widest difference in Tree 4, for instance, is between multilingual female participants in Arizona who have not lived abroad (3.3, closest to “somewhat agree”) versus those who have lived abroad (4.6, closest to “strongly agree”). In other words, growing up as a multilingual person in the US led to our participants seeing a need for DLBE in Arizona. Such differences suggest that individuals’ contextual understandings of the purpose of DLBE are shaped by their experiences of both education and language learning, including where those experiences took place.

RQ2: What are participants’ reasons for their hypothetical policy decision and how do these demonstrate language ideologies mediating DLBE policy making?

In our qualitative analysis of participants’ open-ended responses, we found three main reason types: reasons supporting the switch to DLBE (n = 156), reasons opposing the switch (n = 42), and practical concerns (n = 29; recall that participants could provide multiple reasons in their response.) We separated “for” and “against” reasons into subtypes, resulting in six subtypes justifying the switch, and three against it. (See Appendix C for full codebook with examples).

I. Reasons in support of switch to DLBE (n = 156)

The vast majority of reasons supporting a switch to DLBE cited benefits for individual students (109/156 [69.9% of supporting reasons] in 107/134 total responses [79.9%]). These could further be divided by who they benefited: (a) emergent bilingual students, Spanish-speaking students, and Latinx students (henceforth “heritage studentsFootnote9”) or (b) students in general.

(1) Individual benefits specific to heritage students (n = 59) focused on DLBE as better for English learning compared to other program models; DLBE as sustaining/ strengthening language, culture and identity; and DLBE providing immediate and equal access to content in students’ L1. (2) Individual benefits not ascribed to any specific group (n = 50) had a markedly different set of foci. Here, participants focused on future opportunities stemming from being bilingual, cognitive benefits of bilingualism, and chances to learn about others.

A sizable minority of supportive reasons focused on (3) collective benefits (n = 33) including future benefits to society at large, such as international unity, and present benefits to the school/surrounding community, like inclusion of Spanish-speaking parents in schools. Additional pro-DLBE reasons included: (4) learning a second language is easier when younger (n = 8), (5) multilingualism is important in a globalizing/diversifying world (n = 8), and (6) general, positive responses (n = 8) that were not specific enough to categorize (e.g. “could be beneficial”).

Among participants who provided pro-DLBE reasons (88/134), Likert-scale responses skewed heavily toward agreement with the switch. Fifty of 88 “strongly agreed” (Likert score of 5); nine “agreed” (score of 4), and 19 “somewhat agreed” (score of 3). Only two participants who provided pro-DLBE reasons indicated disagreement (score of 0). However, because the open-ended responses by these two participants were overwhelmingly positive, our hunch is that they may have reversed the orientation of scale and intended to strongly agree.

II. Reasons against switching to DLBE (n = 42)

Reasons against switching to DLBE fell into three broad categories. (7) Misunderstandings about DLBE’s goals and methods (n = 20) reflecting critical gaps in knowledge about DLBE and language acquisition (e.g., concerns that emergent bilinguals would not learn English, that DLBE was too new and experimental, that students would not learn content,Footnote10 or even that DLBE would increase segregation of emergent bilingual students).Footnote11 Other responses reflected (8) broader ideologies about language and society (n = 16), like the relative importance of learning English in the US or the responsibility of families, rather than schools, to teach non-English languages. A handful of participants (9) took issue with the ratio of 90% Spanish and 10% English (n = 6), worrying that it would be “too harsh” or “very confusing” for English speakers.

Recall, however, that participants could provide more than one reason in their responses. Most of the 29 participants who provided the 42 reasons against switching to DLBE also provided some pro-DLBE reasons or practical concerns. Reflecting this, Likert-scale responses for participants who provided reasons against the switch averaged 2.379 and were mostly spread out evenly between “disagree” (n = 6), “somewhat disagree” (n = 7), “somewhat agree” (n = 5), and “agree” (n = 8). As we discuss below, we see this as a positive sign: few participants dismissed DLBE outright, instead grappling with its implications for different participants.

III. Practical concerns (n = 29)

The last group of responses reflects this grappling most clearly. These responses were not against the switch to DLBE, but instead offered 10. practical issues to consider in DLBE implementation: e.g. asking which students would enroll, raising questions about students who spoke a third language, or mentioning the need to further train teachers and increase material support for schools. Interestingly, participants who listed practical concerns were mainly in-favor of implementing DLBE. Of the 22 participants who provided practical concerns, only one selected a Likert score lower than 3. The rest selected 3 (n =8), 4 (n =7), and 5 (n =6) for an average of 3.773.

RQ2: Summary and discussion

Our qualitative analysis of participants’ open-ended responses – their rationale for their hypothetical policy decision – gives us insight into how teachers’ language ideologies mediate their hypothetical policy-making. First, and perhaps most striking, is that the majority of participants’ reasons in support of the DLBE program directly aligned with research on DLBE. Researchers have shown how DLBE programs can support cultural and linguistic maintenance and pride for Latine students (Sánchez & García, Citation2021). Studies have also found that DLBE programs are better for academic and linguistic attainment, in part by supporting curricular access in emergent bilingual students’ first language as they learn the second (Collier & Thomas, Citation2017). Well executed DLBE programs have also been shown to create community, support families, and bridge cultural divides (García-Mateus, Citation2020; Newcomer & Puzio, Citation2016). Additionally, bilingualism has been found to have cognitive benefits (Thomas-Sunesson, Hakuta, & Bialystok, Citation2018) and to be an economic asset, both for individuals and society at large (Callahan & Gándara, Citation2014).

Second, and in contradiction to prior studies, nearly half of our participants’ reasons against the switch to DLBE (20/42) were based on misunderstandings about DLBE programs – e.g., that DLBE increases segregation or does not teach students English. Together, these two trends leave us feeling optimistic about the power of education in informing teachers’ reasoning about DLBE programs: those participants who had accurate information about DLBE and language learning discussed DLBE favorably; those who had misinformation did not (see for similar findings: Fitzsimmons-Doolan et al., Citation2017; Vasquez-Montilla et al., Citation2014). In other words, language ideologies, as systems of beliefs about language and its use, inform understandings about DLBE and this mediate policymaking related to.

Participants’ practical concerns also contribute to our optimism. These concerns hinged on either legitimate debates in bilingual education research or on less-established information: How do you decide which subjects to teach in each language? How do you support third language speakers (students learning both English and Spanish)? As we discuss in RQ 3, our mixed methods approach illuminated that practical concerns also pointed to pro-DLBE policy-making and Pro-Multilingual stances.

RQ3a: How do the reasons participants provide for/against the new DLBE program relate to their hypothetical policy decision?

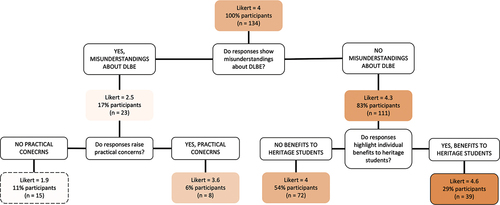

In RQ3, we use a mixed methods analysis: decision tree models relating DLBE support or language ideologies (DV; quantitative) with reason types for that support (IV; qualitative). The decision tree in shows how participants’ reasons (which we analyzed in RQ2) relate to their policy decision (how strongly the support the proposed new DLBE program).

Figure 5. Decision tree model of how reasons relate to DLBE support. Note: Darker shading = higher score; solid border = highest score; dashed outline = lowest score. Participants responded to the 6-point Likert-scale questions with higher number indicating more DBLE support (5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = somewhat agree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 1 = disagree, and 0 = strongly disagree).

shows that Misunderstandings about DLBE was the type of reason most immediately influential on participants’ level of support for DLBE. Participants who demonstrated misunderstandings offered far less support for DLBE (2.5; between “somewhat disagree” and “somewhat agree”) than those who did not demonstrate misunderstandings (4.3; between “agree” and “strongly agree”). However, participants who expressed misunderstandings but who also offered practical suggestions indicated considerably stronger support (3.6; between “somewhat agree” and “agree”) than those who only expressed misunderstandings and offered no practical suggestions (1.9; “somewhat disagree” leaning toward “disagree”). Those who expressed the highest level of support demonstrated no misunderstandings and cited benefits of DLBE for heritage students (4.6; closest to “strongly agree”). These findings highlight the importance of accurate knowledge in informing ideologies mediating policy decisions regarding DLBE programs. They also suggest that a willingness to engage with practical concerns related to developing and running a DLBE program also corresponds to a greater openness to DLBE. These findings are reflected in the following decision trees as well.

RQ3b: How do the reasons participants provide for supporting/not supporting the (hypothetical) new DLBE program relate to their language ideologies?

To answer this research question, we again used mixed methods: decision tree models relating LATS/LBS responses as indicators of language ideologies (DV; quantitative) with reason types for DLBE support (IV; qualitative). As with RQ1a, we operationalized language ideologies three ways: participants’ total LATS scores, LBS Pro-Multilingualism factor score, and LBS Pro-Monolingualism factor score.

Reasons and LATS scores

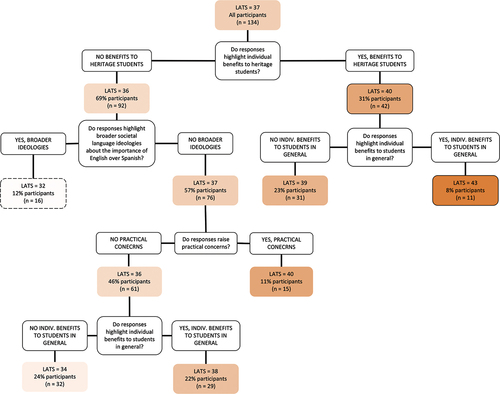

shows how participants’ reasons (coded from open-ended responses) relate to their LATS score (stance toward linguistic diversity and support for language learners/learning).

Figure 6. Decision tree model of how reasons relate to LATS scores. Note: Darker shading = higher score; solid border = highest score; dashed outline = lowest score. Scores shown are the average total score on the LATS for each subgroup with higher scores indicating relatively more positive attitudes toward linguistic diversity than lower scores (Byrnes & Kiger, Citation1994).

The most important explanatory reason for participants’ LATS scores was whether they cited individual benefits of DLBE for heritage students. Those who offered this reason scored significantly higher on the LATS (40 of a possible 52) than those who did not (32). Participants who cited individual benefits of DLBE both for heritage students and for students in general demonstrated the highest LATS scores of all (43). The lowest average LATS scores (32) were from participants who did not cite individual benefits for heritage students and who also expressed broader societal language ideologies about the relative importance of English. As with the decision tree in , this model highlights the centrality of broader language ideologies about who DLBE is good for in mediating policy decisions regarding DLBE. Importantly, raising practical concerns again contributes to more positive stances toward linguistic diversity and language learning support, with participants who did not mention heritage students but raised practical concerns scoring equally high (40) as those who mentioned heritage students.

Reasons and LBS Pro-multilingualism factor scores

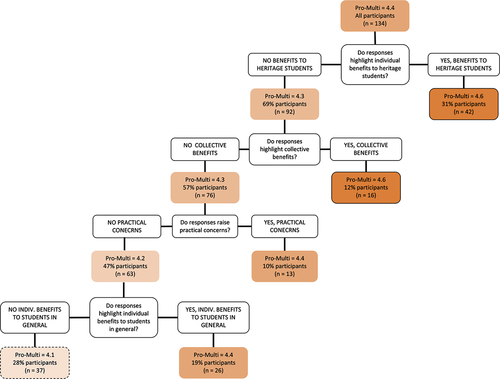

The next decision tree () illustrates how participants’ reasons for their DLBE policy decision relate to their scores on the LBS Pro-Multilingualism factor (which captures the view that multilingualism is useful, important, and positive).

Figure 7. Decision tree model of how reasons relate to LBS Pro-Multilingualism scores. Note: Darker shading = higher score; solid border = highest score; dashed outline = lowest score. Participants responded to the 6-point Likert-scale questions (5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = somewhat agree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 1 = disagree, and 0 = strongly disagree). Each subgroup in this model averages a score between agree and strongly agree.

The most important explanatory predictor in this tree is again whether participants cited benefits to heritage students. Those who did scored higher (4.6, closer to “strongly agree”) than those who did not (4.3, closer to “agree”). However, participants who did not cite benefits to heritage students but who cited collective benefits for communities and schools had equally high Pro-Multilingualism scores (4.6, closest to “strongly agree”). Participants with the lowest Pro-Multilingualism score – who still, however, were in the “agree” range (4.1) – were those who did not offer any of the following reasons: individual benefits to heritage students, collective benefits, practical concerns, or individual benefits to students in general. These findings suggest that agreement with LBS Pro-Multilingual statements (i.e., holding a positive stance toward multilingualism as useful/important) coincide with reasons citing that DLBE is good primarily for heritage students or that it has collective social benefits for students and communities. Similarly, not offering reasons for student or community benefits, as well as a lack of practical considerations, tended to coincide with the lowest Pro-Multilingual scores. Taken together, the strongest implications from are perhaps methodological: that participants’ agreement with statements in both the LBS Pro-Multilingualism factor and the LATS is a useful indication of their concrete (if hypothetical) policy decisions.

Reasons and LBS Pro-monolingualism factor scores

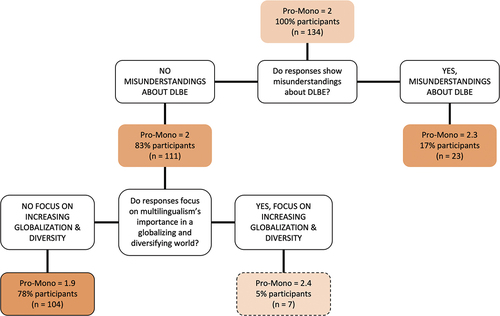

The last decision tree (see ) shows how participants’ reasons explaining their hypothetical policy decision related to their scores on the LBS Pro-Monolingualism factor (which captures the view that English is useful and important in certain contexts).

Figure 8. Decision tree model of how reasons relate to LBS Pro-Monolingualism scores.

Similar to Tree 5, misunderstandings about DLBE played an explanatory role here, though slightly less dramatically. Participants demonstrating misunderstandings about DLBE tended to agree more with items in the Pro-Monolingual factor (2.3, between “somewhat disagree” and “somewhat agree”) than those who did not (2; “somewhat disagree”), indicating more focus on the importance of English across contexts. Interestingly, participants who did not articulate misunderstandings but expressed the importance of multilingualism in a globalizing world scored similarly (2.4; also between “somewhat disagree” and “somewhat agree”). Those without misunderstandings and reasons regarding globalization showed least agreement with Pro-Monolingualism statements (1.9; “disagree” moving toward “strongly disagree”).

These findings suggest adherence to a broadly neoliberal ideology about the utility of multilingualism in a global economy, alongside misconceptions about DLBE, may lead participants to lean toward seeing both multilingualism and English as important. Below, we discuss implications of these findings for understanding the possible role of both competing and reinforcing sets of beliefs about language use and learning.

RQ3: Summary and discussion

In Decision Trees 4–8, we delved deeper into participants’ hypothetical policy making by examining how their reasons explained their relative support for DLBE () and how language ideologies mediate such policy decisions (). Looking across these four trees (see ) points to the kinds of knowledge and understandings about DLBE that shaped participants’ policy-making and related to their language ideological stancetaking.

Table 4. Reason shaping support for DLBE implementation and language ideologies.

Looking across measures shows key patterns. Stronger support for DLBE, higher LATS scores, and greater agreement with Pro-Multilingual statements were all associated with discussing benefits of DLBE for heritage students (e.g., strengthening language, culture and identity or providing equal access to content through instruction in Spanish). Citing benefits for students in general was associated with higher LATS and Pro-Multilingual scores, but did not meaningfully shape DLBE support. Together, these findings suggest that understanding heritage students as the target population for DLBE is connected in important ways to supporting such programs. Additionally, working through practical concerns was associated with higher scores on the same three measures. We see participants who raised practical concerns as truly engaging with the (hypothetical) details of implementation. We wonder, based on work such as Bernstein et al. (Citation2021b), whether there is a positive feedback loop: if engaging in the actual work of navigating the details of DLBE strengthens commitment to the idea of DLBE as well. In this study, on measures of DLBE support, engaging with practical concerns strongly mitigated the negative effects of holding misunderstandings about DLBE (see and 6).

For participants who leaned slightly more toward Pro-Monolingual views (i.e., still disagreed with Pro-Monolingual statements, just less strongly), the reasons associated with pro-DLBE policy-making and Pro-Multilingual ideologies were notably absent. While those participants espoused the importance of multilingualism, they discussed it broadly in terms of “increasing diversity” and “globalization” rather than for specific students or communities, which might not translate readily to DLBE support. Many of these participants also characterized language learning as a beneficial, but optional, activity. Such comments presume an English-speaking target audience, already proficient in the dominant societal language. They also reflect a decontextualized and an ahistorical view of bilingual education, envisioning students who “shop” for languages based on interest or prestige, rather than familial connection or utility in a local community. Finally, participants with moderate Pro-Monolingualism scores often demonstrated misunderstandings about DLBE, which was associated with less support for DLBE and lower LATS scores.

We conclude with implications from this mixed-methods study for how we, as teacher educators and education researchers, might work to understand teacher language ideologies and what might influence them so that multilingual students, families, and communities can be better understood and supported.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we incorporated decision trees into a complementary, transformative mixed methods design, which allowed us to explore the complex intersections between kinds of experiences participants had across contexts, how these intersect with their language ideologies, and how those mediate hypothetical policymaking. Our first set of findings (RQ1) provides compelling evidence for the need to examine demographic and experiential factors in tandem, rather than in isolation. They also provide some insight into which teacher candidates/educators may need more support in understanding multilingualism and multilingual families.

However, it is our mixed methods approach in RQ3 (building on our qualitative analysis addressing RQ2) that provides insight into the kinds of support we as teacher educators might provide by examining how language ideologies (interpreted from different forms of stancetaking) mediates policymaking. These findings suggest that Pro-Multilingual ideologies and DLBE support were associated with: 1) having accurate understandings of DLBE, 2) viewing bilingual/Spanish-speaking/Latine students as key beneficiaries of DLBE, and 3) suggesting practical concerns to consider when implementing DLBE. Conversely, Pro-Monolingual ideologies and lack of DLBE support coincided with: 1) having misunderstandings about DLBE, 2) viewing the learning of languages other than English as optional (suggesting a decontextualized and ahistorical view), and 3) valuing multilingualism more broadly for “increasing diversity” and “globalization.”

Our work also suggests the importance of engaging with hypotheticals, and in particular, engaging in hypothetical policy-making. For participants who articulated misunderstandings about DLBE or pro-English ideologies, simply engaging in hypothetical policy making – raising practical questions about the details of implementation – coincided with greater openness to implementing DLBE. Allowing teachers to raise questions about concrete particulars may also create space for teacher educators to respond with linguistically-informed answers. This possibility seems especially useful in contexts with a history of restrictive language policies. However, given the power of teachers in all contexts and programs – even DLBE programs – to shape policies for multilingual students, hypothetical policy-making has potential utility across contexts.

In sum, the mixed-methods approach in our study points to the importance of considering intersections of educators’ (a) contextualized experiences with language learning, teacher training, and teaching, (b) abilities to discuss DLBE accurately (without misunderstandings), and most importantly, (c) ability to engage concretely with details of hypothetical policy making around DLBE. Attention to these intersections is critical for teacher educators who seek to support pre- and in-service teachers in becoming on-the-ground policy makers of pro-multilingual language policies – in their homes, classrooms, schools, and districts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 One set of questions that we employ in our survey uses “attitudes” and the other uses both “beliefs” and “ideologies.” Scholars often use these terms interchangeably (e.g., Pettit, Citation2011), and prior literature describes a reflexive relationship between attitudes and ideologies – i.e., attitudes about students’ language use convey ideologies (Lawton & de Kleine, Citation2020); ideologies shape attitudes about how language can and should be used (McBee Orzulak, Citation2015). Similarly, “beliefs” features in key definitions of language ideologies: “beliefs about language … as justification of perceived … structure and use” (Silverstein, Citation1979). We use the term “ideologies” throughout this manuscript to encompass these related constructs, except when referring to a specific measure, and we treat participants’ responses across measures as complementary forms of evidence for language ideologies.

2 We use “Dual language bilingual education” (DLBE) to refer to programs in which content is taught through two languages with the goals of bilingualism and biliteracy. We intentionally choose a term that includes the word, “bilingual,” to point to the history of US bilingual education that precedes “dual language education.”

3 Unless parents applied and were approved for a waiver. Approval could be granted for older students (10+) or students with disabilities who had been placed in English-only settings for a year and failed to learn there.

4 We use Latine (rather than Latinx, which is unpronounceable in Spanish) as a gender-neutral alternative to Latino.

5 For example, in our study, some demographic variables (e.g., program type, living in Arizona) were obviously correlated. The regression model between demographics and Pro-Multilingualism scores, with “program type” included, indicated non significant relationships. However, without “program type,” the model showed a significant relationship between gender and Pro-Multilingualism (β = −5.295, p = .041). Instead, in , the relationship between gender and Pro-Multilingualism is shown clearly without leaving out program type, because multicollinearity is not at issue. The decision tree more effectively parses out contingencies between variables.

6 That said, our reading was certainly informed by our knowledge of conversations in the field, e.g., about the gentrification of DLBE (Valdez, Freire, & Delavan, Citation2016), shifts in who DLBE serves (from emergent bilingual students to English speakers), and to what ends (equity versus enrichment) (Bernstein et al., Citation2021b; Flores & García, Citation2017).

7 We use the term “stance” to refer to articulated positions on language use/learning (Jaffe, Citation2009) in commentary (spoken or written) and through responses to Likert-scale items common on measures of language attitudes and ideologies. Stancetaking thus offers multiple inroads to examine language ideologies (e.g., Showstack, Citation2017).

8 This construction – “participants who identified as X” – reflects that these categories are not fixed but rathe how participants chose to identify themselves when taking this survey. The first time we reference a demographic category, we use this construction. Then, to increase readability, we use the simpler constructions, “female participants,” “Black participants,” etc.

9 Although these three groups do not always overlap in Arizona schools, because of their shared focus on students’ cultural and/or linguistic inheritance (often marginalized in schools, but often explicitly supported in DLBE programs), we refer to these three groups as “heritage students” to reduce wordiness throughout.

10 These concerns are contradicted by decades of strong evidence that DLBE programs that last for all of elementary school are the best programs for students learning English (e.g., Collier & Thomas, Citation2017).

11 This is a common straw man argument against DLBE (especially in Arizona) when emergent bilingual students have been segregated into state-mandated Structured English Immersion classes (see Arizona Context section). One district that Author 1 worked in even had SEI students eating lunch separately from English speaking students. With the 2019 policy change, emergent bilingual students can now participate in DLBE and many AZ districts are expanding DLBE programs into true two-way programs as quickly as possible.

12 Our survey instrument included an “other” (write-in) selection for gender, but no participants selected it.

13 Other than English. All participants spoke English, either as an only language or in addition to the languages listed.

References

- Anderson, K. T., Ambroso, E., Cruz, J., Zuiker, S., & Martinez-Rodriguez, S. (2022). Complicating methods for understanding educators’ language ideologies: Transformative approaches for mixing methods. Language and Education, 36(1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/09500782.2021.1931296

- Arizona House Bill 2064. (2006). 47th Legislature, 2nd Regular Session (Arizona 2006). https://www.azleg.gov/legtext/47leg/2r/summary/s.2064approp_asenacted.doc.htm

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How Schools Do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary Schools. Routledge.

- Bernstein, K. A., Alvarez, A., Chaparro, S., & Henderson, K. I. (2021b). “We live in the age of choice”: School administrators, school choice policies, and the shaping of dual language bilingual education. Language Policy, 20(3), 383–412. doi:10.1007/s10993-021-09578-0

- Bernstein, K. A., Kilinc, S., Deeg, M., Marley, S., Farrand, K., & Kelley, M. (2021a). Language ideologies of Arizona preschool teachers implementing dual language teaching for the first time. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(4), 457–480. doi:10.1080/13670050.2018.1476456

- Breiman, L., Friedman, J. H., Olshen, R. A., & Stone, C. J. (1984). Classification and Regression Trees. Wadsworth.

- Byrnes, D., & Kiger, G. (1994). Language attitudes of teachers scale (LATS). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 54(1), 227–231. doi:10.1177/0013164494054001029

- Byrnes, D., Kiger, G., & Manning, L. (1997). Teachers’ attitudes about language diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 13(6), 637–644. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(97)80006-6

- Callahan, R. M., & Gándara, P. C. (2014). The bilingual advantage: Language, literacy and the US labor market. Multilingual Matters.

- Chang-Bacon, C. (2020). “It’s not really my job”: A mixed methods framework for language ideologies, monolingualism, and teaching emergent bilingual learners. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(2), 172–187. doi:10.1177/0022487118783188

- Collier, V., & Thomas, W. (2017). Validating the power of bilingual schooling: Thirty-two years of large-scale, longitudinal research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 203–217. doi:10.1017/S0267190517000034

- Combs, M. C., & Nicholas, S. E. (2012). The effect of Arizona language policies on Arizona Indigenous students. Language Policy, 11(1), 101–118. doi:10.1007/s10993-011-9230-7

- Creswell, J., & Plano-Clark, V. (2010). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Dávila, B. (2016). The inevitability of “standard” English: Discursive constructions of standard language ideologies. Written Communication, 33(2), 127–148. doi:10.1177/0741088316632186

- Deroo, M., & Ponzio, C. (2019). Confronting ideologies: A discourse analysis of in-service teachers’ translanguaging stance through an ecological lens. Bilingual Research Journal, 42(2), 214–231. doi:10.1080/15235882.2019.1589604

- duallanguageschools.org. (n.d.). Dual Language Schools in Arizona. Retrieved January 28, 2022, https://duallanguageschools.org/schools/az/

- Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S. (2014). Language ideologies of Arizona voters, language managers, and teachers. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 13(1), 34–52. doi:10.1080/15348458.2014.864211

- Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S. (2018). Language ideology change over time: Lessons for language policy in the U.S. state of Arizona and beyond. TESOL Quarterly, 52(1), 34–61. doi:10.1002/tesq.371

- Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S., Palmer, D., & Henderson, K. (2017). Educator language ideologies and a top-down dual language program. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(6), 704–721. doi:10.1080/13670050.2015.1071776

- Flores, N., & García, O. (2017). A critical review of bilingual education in the United States: From basements and pride to boutiques and profit. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 14–29. doi:10.1017/S0267190517000162

- Fredricks, D. E., & Warriner, D. S. (2016). “We speak English in here and English only!”: Teacher and ELL youth perspectives on restrictive language education. Bilingual Research Journal, 39(3–4), 309–323. doi:10.1080/15235882.2016.1230565

- Gal, S. (1989). Language and political economy. Annual Review of Anthropology, 18(1), 345–367. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.18.100189.002021

- García, S., & Guerra, P. (2004). Deconstructing deficit thinking: Working with educators to create more equitable learning environments. Education and Urban Society, 36(2), 150–168. doi:10.1177/0013124503261322

- García-Mateus, S. (2020). Bilingual student perspectives about language expertise in a gentrifying two-way immersion program. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism.

- Garrity, S., Aquino-Sterling, C. R., Van Liew, C., & Day, A. (2018). Beliefs about bilingualism, bilingual education, and dual language development of early childhood preservice teachers raised in a Prop 227 environment. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(2), 179–196. doi:10.1080/13670050.2016.1148113

- Godley, A. J., Reaser, J., & Moore, K. G. (2015). Pre-service English Language Arts teachers’ development of Critical Language Awareness for teaching. Linguistics and Education, 32, 41–54. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2015.03.015

- Gomes, C., & Almeida, L. S. (2017). Advocating the broad use of the decision tree method in education. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 22(1), 1–10.

- Greene, J., Caracelli, V., & Graham, W. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274. doi:10.3102/01623737011003255

- Heineke, A. J. (2017). Restrictive language policy in practice: English learners in Arizona. Multilingual Matters.

- Henderson, K. (2017). Teacher language ideologies mediating classroom-level language policy in the implementation of dual language bilingual education. Linguistics and Education, 42, 21–33. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2017.08.003

- Hornberger, N. H., & Johnson, D. C. (2007). Slicing The Onion ethnographically: Layers and spaces in multilingual language education policy and practice. TESOL Quarterly, 41(3), 509–532. doi:10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00083.x

- Irvine, J. (1989). When talk isn’t cheap: Language and political economy. American Ethnologist, 16(2), 248–267. doi:10.1525/ae.1989.16.2.02a00040

- Jaffe, A. (2009). Stance: Sociolinguistic perspectives. Oxford.

- Johnson, D. C. (2010). Implementational and ideological spaces in bilingual education language policy. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 13(1), 61–79. doi:10.1080/13670050902780706

- Jung, C. (2017, February 27). Arizona ELL student graduation rate lags far behind national average. KJZZ. https://kjzz.org/content/440381/arizona-ell-student-graduation-rate-lags-far-behind-national-average

- Kaveh, Y. M., Bernstein, K. A., Cervantes-Soon, C., Rodriguez-Martinez, S., & Mohamed, S. (2021). Moving away from the 4-hour block: Arizona’s distinctive path to reversing its restrictive language policies. International Multilingual Research Journal, 1–23.

- Kroskrity, P. (2010). Language ideologies. In J. Östman & J. Verschueren (Eds.), Handbook of Pragmatics (Vol. 14, pp. 1–24). John Benjamins.

- Lawton, R., & de Kleine, C. (2020). The need to dismantle “standard” language ideology at the community college: An analysis of writing and literacy instructor attitudes. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 50(4), 197–219. doi:10.1080/10790195.2020.1836938

- Lew, S., & Siffrinn, N. (2019). Exploring language ideologies and preparing preservice teachers for multilingual and multicultural classrooms. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 68(1), 375–395.

- Lillie, K. E. (2016). The lost generation: Students of Arizona’s structured English immersion. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 19(4), 408–425. doi:10.1080/13670050.2015.1006162

- Lillie, K. E., & Markos, A. (2014). The four-hour block: SEI in classrooms. S. C. K. Moore Ed. Language Policy Processes and Consequences: Arizona Case Studies (pp. 133–155). Multilingual Matters.

- Martinez, D., & Martínez, R. (2017). Researching the language of race and racism in education. In K. King et al. (Eds.), Research methods in language and education. Encyclopedia of language and education (3rd ed., pp. 503–516). Springer.

- McBee Orzulak, M. (2015). Disinviting deficit ideologies: Beyond “That’s standard,” “That’s racist,” and “That’s your mother tongue.” Research in the Teaching of English, 50(2), 176–198.

- McCarty, T. (Ed.). (2011). Ethnography and language policy. Routledge.

- Mettler, S. (2016). The policyscape and the challenges of contemporary politics to policy maintenance. Perspectives on Politics, 14(2), 369–390. doi:10.1017/S1537592716000074

- Metz, M. (2019). Accommodating linguistic prejudice? Examining English teachers’ language ideologies. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 18(1), 18–35.