ABSTRACT

Framed in teacher research, this article examines on how a group of 220 preservice language teachers’ understandings of teacher agency evolved in a course on second language teaching curriculum. The participants were enrolled on a master’s program on teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL), and data were gathered through course activities which included two surveys, reflective blogs, and an essay. Based on inferential statistics and qualitative content analysis, findings show that, with different degrees of confidence, the student-teachers believe that their projective (future) agency was harnessed through the course developing (1) willingness to use teacher agency as a tool for professional development and (2) willingness to use teacher agency as a drive to engage in critical teaching practices for multilingual settings. Drawing on a trans-perspective of language teacher agency, the study advances a model of projective teacher agency.

Introduction

If initial teacher education is redirecting its efforts to prepare pre-service teachers (PSTs) to become critically conscious teachers for multilingual classrooms (Banegas & Gerlach, Citation2021), agency needs to play a pivotal role in PSTs’ ownership of their practices. As Melo-Pfeifer (Citation2023) suggests, it is crucial that teacher education provides PSTs with agentive tools to enhance multilingual teaching and learning.

Within the architecture of language teacher education for multilingual settings, agency has attracted attention in (language) education and teacher education (e.g., Kayi-Aydar, Gao, Miller, Varghese, & Vitanova, Citation2019; Tao & Gao, Citation2017; Xu & Fan, Citation2022). These studies demonstrate that research on teacher agency is crucial for understanding (and promoting) how teachers can exercise ownership of their teaching and professional development. Despite this steady interest in novice or experienced teachers’ agency, research is needed to understand how PSTs’ sense of agency in multilingual teacher education could evolve, particularly for contexts in which PSTs assume there is no place for teacher agency. Examining PST agency as projective/future teacher agency for multilingual teacher education can contribute to understanding how multilingual diversity in the classroom could be harnessed, celebrated, and maximized in the context of formal education as well as at the societal level. For the purposes of this study, projective agency is conceptualized as PSTs’ anticipated or imagined capacity to direct and own their teaching practice when they obtain their first teaching post.

In this paper, we explore how a group of 220 PSTs’ understandings of teacher agency evolved in a course on second language teaching curriculum, and how they could claim ownership of their future teaching practices during that evolution. The study was conducted with 220 PSTs enrolled on a master’s program on teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL).

Conceptual background

Teacher agency

We understand teacher agency as a highly dynamic and relational construct that operates within systems of social practice (Kayi-Aydar et al., Citation2019a). As noted by Kayi-Aydar (Citation2019a, Citation2019b), within the body of research dedicated to teacher agency, there is a variety of conceptualizations developed from differing theoretical perspectives, such as social-cognitive, sociocultural, and ecological. Despite the differences among these perspectives, there is a growing consensus that teacher agency is negotiated between the individual and their context (Miller, Kayi-Aydar, Varghese, & Vitanova, Citation2018).

Bandura’s (Citation2001) social-cognitive perspective views agency as a result of internal cognitive processes that influence a person’s ability to act intentionally. This psychological mechanism mediates individuals’ intentional acts to participate in their development, adaptation, and self-renewal to cope and respond to evolving contexts and circumstances. In contrast, scholars such as Lasky (Citation2005) and Kayi-Aydar (Citation2019a) have perceived agency as a socioculturally mediated capacity to act. Stated another way, in addition to contextual conditions, individual agency is shaped through stakeholder interactions during agency development which produces a shared form of agency. Goller and Harteis (Citation2017) conceptualize agency from multifaceted agentic perspectives. Specifically, agency is modeled through agency competence (i.e., an agent’s ability to act), agency beliefs (i.e., an agent’s perception of their ability to act), and agency personality (i.e., an agent’s inclination to choose to act). Teacher agency has also been conceptualized from an ecological perspective (Biesta & Tedder, Citation2007; Priestley, Biesta, & Robinson, Citation2015). From this viewpoint, agency is a phenomenon transactionally negotiated between individual capacities and contextual/materials conditions. Actors act in an environment through the micro-, meso-, and macro-layers rather than one-dimensionally. From this standpoint, agency refers to what teachers decide to do or not do, and these agentic moves are informed by past (iterational) experiences, future-oriented actions and selves (projective). In language teaching research, this ecological perspective has particularly informed studies examining language teacher agency for social justice, multilingual advocacy, and inclusion to interrupt inequity detrimental to minoritized races, languages, and gender identities (e.g., Davis & Howlett, Citation2022; Leal & Crookes, Citation2018; Peña-Pincheira & de Costa, Citation2021; Vitanova, Citation2018).

Rather than seeing these conceptualizations as competing and adopting an “exclusion” mind-set, Tao and Gao (Citation2021) have encouraged the adoption of a transdisciplinary framework. From a trans-perspective in future research on language teacher agency, Tao and Gao put forward a perspective of teacher agency () that is holistic in theory. It expands upon the temporal dimension of agency within teachers’ professional growth to understand the dynamic interplay between agency and context across the course of teachers’ career.

In further recognition of the multifaceted and dynamic nature of teacher agency, the trans-perspective highlights the importance of collective agency and includes institutions (macro), groups (meso), the individual (micro), and the social interactions among them within a multi-layered model. This model reflects the need for an integral approach to multilingualism and multilingual education as put forward by the Douglas Fir Group (Citation2016). We believe that this trans-perspective model may be particularly helpful to investigate PSTs’ understanding of agency in connection to curriculum development as it comprises the links between different layers of interaction and power over time that influence curriculum design, implementation, and change. This perspective is particularly important in contexts where national standardized testing and heavy top-down policies may diminish teachers’ degrees and self-perceived sense of agency (Poulton, Citation2020).

Language teacher agency and understanding curriculum development

Language teacher agency may enable teachers to be part of curriculum development. However, as Macalister and Nation (Citation2020) note, teachers’ understanding of curriculum development is crucial for them to become agentically engaged in curriculum change. Hence, the authors suggest that understanding of curriculum development may involve teachers’ knowledge about key elements in curriculum design such as needs analysis, learning outcomes, teaching materials, pedagogical approaches, evaluation, or environmental constraints.

A few studies have examined the relationship between language teacher agency and understanding curriculum development. From a case study in Chinese higher education, Yang (Citation2012) found that the agency of two young teachers was constrained by their limited understanding of curriculum development, indefinite belief systems, and insufficient support. In contrast, a teacher with extensive experience and knowledge of curriculum reform were able to take agentive actions to resolve contradictions in her teaching. Driven by these findings, Yang suggests that young language teachers need theoretical and practical knowledge about curriculum development to enhance their present and/or future agency. Also in China, Wang (Citation2022) surveyed 353 secondary school teachers and collected data from three case study participants. Most of the surveyed teachers demonstrated favorable attitudes and beliefs toward implementing the reform and a willingness to change. However, they also exhibited limited agency in practice given their limited professional knowledge on curriculum development. In similar contexts, other studies have indicated that teacher agency can be boosted when teachers develop professional knowledge around curriculum elements such as resources (Yang & Clarke, Citation2018), the pernicious washback effect of national exams on practices (Liyanage, Bartlett, Walker, & Guo, Citation2015; Molina, Citation2016), or textbooks analysis (Liyanage, Bartlett, Walker, & Guo, Citation2015). Therefore, these studies lend support to Macalister and Nation’s (2020) call for supporting teachers’ knowledge of curriculum development as a form of enhancing their understanding of language teacher agency.

In line with the aforementioned argument, Tao and Gao (Citation2017) propose an agency-oriented approach to pre-service teacher education in which teacher educators guide PSTs to become more aware of their personal resources and learn to capitalize on them to seize available contextual opportunities. They suggest that educational reform should be built into teachers’ professional development to sustain their dedication to new enterprises. Aligned with this call, Yangın Ekşi et al. (Citation2019) investigated the impact of practicum teaching on PSTs’ professional agency development. Drawing on data obtained from reflective reports, the authors noted that discussing agency in teacher preparation allowed the PSTs to (1) assume agentic responsibility for their professional development, (2) exhibit perseverance and willingness to be active agents of curriculum change, and (3) develop a sense of belonging to the language teaching profession. Our study could also be viewed as a response to this call as pre-service language teachers attended a course on language curriculum development designed and delivered with a teacher agency orientation. Against this backdrop, the following question guided this study: In what ways does a course on language curriculum development contribute to PSTs’ understanding of teacher agency?

Methods

This study adopted teacher research (Consoli, Citation2022), as we carried out this investigation in a course we designed and taught in September – November 2022. This means that our reflexivity (Consoli & Ganassin, Citation2023) was informed by our insider knowledge of the context, which reconciled teaching, learning, and researching.

Context and participants

The study reported in this article was conducted at a master’s program in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) at a UK university. In particular, we examined a core Term 1 course called Second Language Teaching Curriculum, which was driven by the following aims:

Analyze and evaluate the components of second language curricula and articulate the dynamic relationship between them.

Understand, analyze, and evaluate a curriculum in terms of sustainability and global citizenship.

Demonstrate a critical understanding of the concept of colonization and decolonization in the context of second language teaching curricula.

Provide a detailed and critical evaluation of the role of the teacher as agent of change in a particular curricular context.

The core contents of the syllabus were: conceptualization and problematization of the language curriculum, the politics of and behind curricula, curriculum design and elements based on Macalister and Nation (Citation2020), curriculum change and sustainability, global citizenship education, and agentive teachers as curriculum makers. Teacher agency became a topic that interweaved the aims, contents, and activities (See data collection instruments). In this regard, the students were expected not only to develop knowledge and understanding of curriculum development, but also reflect on how their understandings of teacher agency evolved during the course. The aims and contents were aligned with developments in the literature, such as the need to allow PSTs to analyze curricula (Yang & Clarke, Citation2018) or discuss a variety of issues from a social justice philosophy of education (e.g., Peña-Pincheira & de Costa, Citation2021). In terms of delivery, the course extended over ten teaching weeks including eight prerecorded lectures, eight in-person seminars, and a school visit.

In 2022, the course was attended by 243 students, of which 90% were from China. Other students were from Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey. Out of those students, 220 participated in this study. The participating students were considered PSTs given that 115 (52.27%) had between one and two years of teaching experience, mostly as teaching assistants. The rest had none (n = 11, 5%) or between two and five (n = 94; 42.73%) but usually in temporary posts.

Data collection

Data were collected through an ecological approach (Arcidiacono, Procentese, & Di Napoli, Citation2009; Stelma & Fay, Citation2014), i.e., data collection coincided within the regular delivery of the course described above. It included the teaching materials, the students and their coursework, the program, and the university, but also the interconnected teaching and learning processes underpinning the delivery of the course. The 220 students who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study signed a written consent form which explained their rights, ensured anonymity and confidentiality, and would be subjected to no academic consequences for withdrawing from the study. They are referred to through pseudonyms in this paper.

The four instruments detailed below fulfilled a dual purpose: learning activities and data collection instruments.

Survey: As an activity in Week 1 of the course, an initial survey was conducted with the aim of landscaping the students’ previous engagement with agentic activities in English teaching and their beliefs about teacher agency. Teaching experiences were measured across nine items on a four-point Likert scale from the least amount of experience (score 1; “Not At All”) to the most (score 4; “A Great Deal”) – see for the items and the full scale. Beliefs about teacher agency were measured across eight items in which participants rated their agreement to a particular statement on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (“Completely Disagree”) to 4 (“Completely Agree”). Among the eight items, half focused on students’ general beliefs about teacher agency in their context (Item 1, 3, 7, & 8) and the other half on their specific beliefs about their own agency in teaching (Item 2, 4, 5, & 6). The eight items contained a mixture of positive statements (Item 1, 2, 5, 7, & 8) and negative ones (Item 3, 4, & 6). Therefore, the scores of the negative items were coded reversely for analyses (e.g., score 4 for “Completely Disagree,” and 1 for “Completely Agree”). In this way, we converted the agreement scale into a unified scale across all items, with smaller scores indicating more negative beliefs (e.g., score 1; “Completely Negative”) and bigger scores more positive beliefs (e.g., score 4; “Completely Positive”) – see for the items and the converted scale. The survey can be accessed at https://edinburgh.eu.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_29TypjhgKUhU4Cy.

Reflective blog 1: In Week 4 of the course, each student was expected to submit a 400-word reflective blog following the following instructions.

First paragraph: What’s the aim and topic of your blog? Why have you chosen to talk about this topic? Are you focusing on one perspective/author in particular?

Main body paragraphs: What did you know about this topic before the lectures? What have you learnt now? How has this new knowledge influenced your thinking about curriculum development and/or language education? What benefits and challenges do you find around this topic in relation to your own local/regional/national context?

Last paragraph: How can knowledge about this topic help you improve your agentive practice as an educator?

Reflective blog 2: In the final week, the students were invited to share their main takeaway from the course on a Padlet.

Final essay: Each student submitted a 2,500-word essay in which they were required to analyze an element (e.g., assessment) of a curriculum or coursebook of their choice from one perspective discussed in the course (e.g., sustainability), make a proposal for change, and conclude by reflecting on how the analysis and proposal might contribute to their own teacher agency as curriculum makers.

We must acknowledge that Reflective blog 1 and the final essay were part of the course’s summative assessment; therefore, the students may have displayed different attitudes and knowledge as they were aware that these would be graded.

Analytical approach

We adopted mixed methods (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018) to analyze the data, quantitatively for the survey data and qualitatively for the reflective blogs and final essays.

The survey data were analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistics. All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.1.2; R Core Team, Citation2021). To present the distribution of participants’ ratings, we used descriptive statistics and plots that were generated using the “Likert” package (Bryer & Speerschneider, Citation2016). Inferential statistics was used to investigate whether participants’ beliefs about teacher agency was dependent of the perspective that they took (i.e., general perspective of agency in their context vs. specific perspective of their own agency). Specifically, we used generalized additive modeling (GAM) using the “mgcv” package (v1.8–34; Wood, Citation2017), as hierarchical models of this kind have been suggested to be appropriate for Likert-scale data (Tutz, Citation2021). We fitted hierarchical models with the same fixed effect “Perspective” (General vs. Specific) and different structures for the random effects (i.e., individual differences among participants, and among survey items). Model comparison using Chi-squared test suggested the best fitted model was the one with by-participant random intercepts, by-participant random slopes, and by-item random intercepts (∆deviance ≈174.76, p < .001). This model was also compared with a null model including only the intercept and no predictor, the results of which suggested that including “Perspective” as a fixed effect significantly improved model fit (∆deviance ≈175.08, p < .001). Thus, we report the results based on this model.

The reflective blogs and final essays were imported into ATLAS.ti version 8 for qualitative content analysis (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, Citation2018; Selvi, Citation2020). Qualitative content analysis was an iterative process of reading and rereading the data to identify initial codes, which were then grouped into themes (see Findings). To ensure confirmability, trustworthiness, and transparency (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985), a colleague unfamiliar with the study independently rated 50% of each data set. Discrepancies were discussed until an agreement was reached.

Findings

Drawing on the analyses of the data sets, we have decided to present the findings in chronological order as they depict the PSTs’ evolving understanding of teacher agency as they navigated the course.

Students’ previous and projective engagement with agency

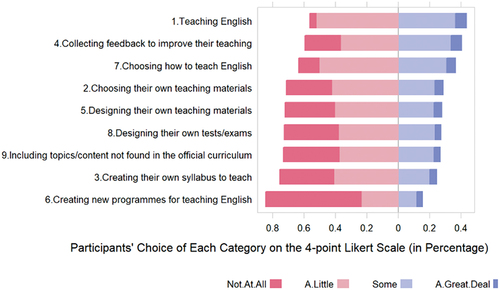

Students’ ratings on their experiences of engaging with agency in different aspects of teaching are presented in . It shows that the participants started the course with limited opportunities to exercise their agency. This may partly be due to their limited teaching experience and temporary nature of their posts as noted above, which may have become conducive for raising awareness about teacher agency. Their lack of opportunities for agentic practices reaffirmed the course focus on agency in the context of language teacher education as encouraged in the literature (e.g., Tao & Gao, Citation2017; Yangın Ekşi et al., Citation2019).

It is worth noting that those items pertaining to collecting for feedback to enhance teaching (Item 4) and making pedagogical decisions (Item 7) were ranked higher than other activities. These findings may indicate that the students, despite a perception of having limited agency, could still direct changes in specific areas of curriculum development such as teaching approaches. Therefore, at the framed-in-the-past micro-system of language teacher agency (Tao & Gao, Citation2021), the PSTs exhibited a certain level of agency competence as Goller and Harteis (Citation2017) term it.Footnote1

Students’ general and specific beliefs about agency

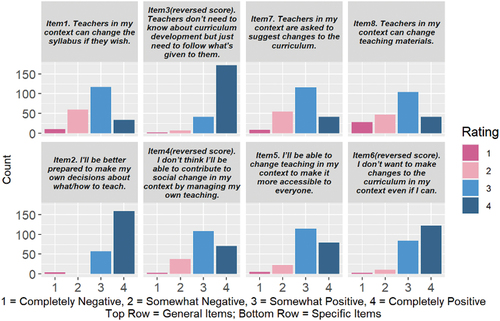

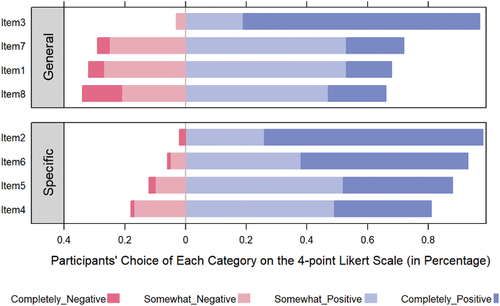

Through ratings on a series of first-person or third-person statements, the students indicated general beliefs about teacher agency in their context (Items 1, 3, 7, and 8; the top row in ) and specific beliefs about their own use of teacher agency (Items 2, 4, 5, and 6; the bottom row in ). summarizes the percentages of participants’ choices of each category on the 4-point Likert Scale.

Table 1. Participants’ beliefs about Agency.

Overall, PSTs showed positive beliefs about teacher agency. Indeed, as shown in , 76% of the participants rated positive (somewhat or completely) for their general beliefs about teacher agency in their context, and 90% for their specific beliefs about their own agency. It is worth noting that although a minority of participants showed negative beliefs about teacher agency (24% and 10% for the general items and the specific items respectively), we do not treat this as a discrepancy because there was only 5% “completely disagree(/negative)” ratings and their overall tendency was dominantly positive. They displayed a particularly positive belief around teachers’ ability to engage in curriculum development as agents of change (Item 3). In this regard, the participants recognized the framed-in-the-present ability to direct their actions at the micro layer of teacher agency (Tao & Gao, Citation2021) thus acknowledging teachers’ agency competence and personality (Goller & Harteis, Citation2017).Footnote2

Interestingly, as shown in , the distribution of ratings for the general and specific items seem to suggest that students were more positive about their specific beliefs about their own use of agency than their general beliefs about agency in their context. Indeed, the proportion of the choice “Completely Positive” appears notably higher for the specific items (49%; dark blue segments in the bottom panel in ) than the general items (33%; the top panel). Moreover, the proportion of negative choices for the specific items (10%; the dark and light pink segments in the bottom panel) seems much lower than the general items (24%; the top panel). However, the results of our inferential statistics using generalized additive modeling suggest that these differences did not reach statistical significance. summarizes the results. It shows that the probability of giving a more positive rating is not significantly affected by the perspective taken. Specifically, when taking a specific perspective of their own use of teacher agency, participants gave similar ratings as they did when taking a general perspective concerning teacher agency in general in their context (β = 1.02, SE = .99, 95%CI = [−.93, 2.97], p = .31). In other words, there were no statistical differences, and students’ beliefs about their own teacher agency were aligned with their general beliefs about their context. We interpret these results as suggesting that, at the beginning of the course, PSTs’ awareness of their ability of using their own agency was limited, not beyond their general understanding of teacher agency in their context.

Table 2. Results of GAM analysis of the effect of “perspective” (general vs specific) on beliefs of Agency.4

Agency for professional development and critical teaching practice

Qualitative content analysis of the reflective blogs showed that the PSTs’ insights around teacher agency during the course orbited around two main themes in relation to teaching English in a multilingual context: (1) willingness to use teacher agency as a tool for professional development and (2) willingness to use teacher agency as a drive to engage in critical teaching practices. Therefore, these themes suggest that, as stressed in Yang (Citation2012) and Wang (Citation2022), the participants’ agency beliefs and personality evolved as they developed professional knowledge about the language curriculum (Goller & Harteis, Citation2017).Footnote3

In terms of teacher agency as a source for professional development, the students’ reflections highlighted three interconnected aspects, as shown below. Fifty-seven PSTs acknowledged that teacher agency could be used to address their self-perceived professional lacks. For example, Chiara wrote:

Teachers can learn from each other. By observing fellow teachers as a third party, I can locate my own deficiency. Learning how to interact with multilingual students in class is also an activity to enhance my teacher agency. At the same time, by observing and reflecting on what I can do, I can also explore how the learning environment can impact on my teaching. (Chiara, Extract 1)

Extract 1 shows that teacher agency may lead Chiara to plan a course of action that includes observing colleagues so that she can develop strategies around teacher-learner interaction in a given context. While some PSTs, such as Chiara, started from a deficit perspective to consider their further professional development, others (n = 108) remarked connections between agency and different aspects of their practice. For instance, Catalina reconciled teacher agency and professional development geared toward enriching exam-oriented teaching and testing:

[…] attending professional teacher training provides different perceptions on how to develop teacher agency, for example, to cope with the exam-oriented teaching style in China, the idea of assessment for learning is introduced to teachers, documenting the tests taken by students as portfolios is an innovative method that can help students to review their learning. “Agency happens through context, not just context.” (Priestley, Edwards et al., 2012). The ongoing process of problem-solving and action-taking is a symbol of achieving agency. (Catalina, Extract 2)Footnote4

Extract 2 reveals that students recognized that the exam-oriented policy cannot be changed easily (“to copy with”). Catalina agentically chose to negotiate it and transform exams into a method for learning by suggesting the use of exam portfolios. Although the extract confirms the power of exams (Molina, Citation2016; Poulton, Citation2020) in China, it is inspiring to note that such a top-down policy may not diminish PSTs’ projective agency. This finding may suggest that PSTs’ future agency and views of assessment evolved as they negotiated professional knowledge about curriculum development with practices in the context of policies.

In a similar vein, 71 PSTs noted that teacher agency could be used to engage in self-led and self-initiated continuing professional development, as shown in Extracts 3 and 4:

I can use my agency to organize and benefit from my own reflection and attend courses that can help me improve my teaching for multilingual education. (Barbara, Extract 3)

Teacher agency can be constructed and developed by participating in professional learning sessions, keeping on reflection and engaging in teacher-student interactive and collaborative activities. (Dandan, Extract 4)

Extracts 3 and 4 confirm Yangın Ekşi et al. (Citation2019) study, as the participants assumed agentic responsibility in directing their professional development. As in Extract 1, these two extracts also highlight that, as theorized in Tao and Tao and Gao’s (Citation2021) model, the participants’ journey from past to projective identity embraces collective identity as they recognize that they can improve their agentic pedagogical decisions and professional development by interacting with other teachers. In this regard, the participants seem to recognize that the improvement of their individual professional agency necessitates their engagement with other teachers, which leads to the construction of a space for collective agency.

Last, 205 PSTs problematized the views displayed in , Item 3, by stating that, for example:

The topics covered in the course have permitted me to understand that teachers are not policy followers but curriculum designers, and we have the right and freedom to have a say in the classroom within our schools. Teachers have the responsibility and ability to plan the curriculum for their own teaching. (Xie, Extract 5)

The finding illustrated by Extract 5 shows that the course on language curriculum development, as an example of professional knowledge, allowed the participants to challenge the view of teachers as acritical and passive curriculum implementers. Furthermore, the course incentivized them to understand teacher agency not only as a right but also as a responsibility, which may prompt us to suggest that their newly developed sense of projective agency did not position them in a reactive policy-driven state but in a proactive institution-framed space. In this regard, knowledge about curriculum development not only led the PSTs to navigate the temporal dimension of language teacher agency (Tao & Gao, Citation2021) but also supported their understanding and projection of agency through its micro-, meso, and macro-dimensions.

In line with the topics addressed in the course, 182 students went further and connected their projective teacher agency with the ability to enact change to add a critical perspective to the language curriculum. This critical perspective was harnessed through different aspects, such as gender diversity and equality. These aspects suggest that, as previously reported (e.g., Leal & Crookes, Citation2018; Vitanova, Citation2018), attention to agency can lead to addressing social justice. For example, Siri wrote:

I believe I can enhance my own teacher agency. In the teaching process, I will emphasize integrating the awareness of gender equality. Attention is also paid to the use of more inclusive terms, such as avoiding to use the sexist words with “man” as their suffix, using chairperson to replace chairman, salesperson to replace salesman, firefighter to replace fireman, etc. Another example is to avoid the generalization of masculine word of “he.” I will change the singular to a plural and use “they” and “their.” (Siri, Extract 6)

In Siri’s case, she planned to use her projective teacher agency to create gender-inclusive learning experiences, even if these appeared to be initially bound to terms and pronouns. In this regard, Siri viewed her agency beliefs and personality (Goller & Harteis, Citation2017) as an opportunity to dismantle patriarchal discourses embedded in education. In a similar vein, other students remarked that they could use their projective teacher agency to unsettle hegemonic ideologies and discourses normalized in coursebooks. A student wrote that even though teachers may not be involved in the design of the official curriculum,

They could nevertheless guide students to be critical of how some people, cultures, or social practices are portrayed or erased in the coursebook. Through simple questions that promote awareness I can minimize the drawbacks in the coursebook by exercising my agency. (Fumi, Extract 7)

Extract 7 illustrates that although PSTs may recognize contextual and policy constraints, they could engage in agentic and advocacy actions to critically use teaching materials. In this case, PSTs would not be mobilizing their agency in response to policy but in reaction to ideological discourses entrenched in coursebooks. With a similar focus on problematizing dominant discourses, another student integrated teacher agency and decolonization:

I’ve realized that decolonization and the power behind language are important for me and my teaching. I need to be aware of this and use my agency to try to decolonize the enacted curriculum by introducing different teaching material and different cultures. (Sin, Extract 8)

Extract 7 and 8 may also show that PSTs’ projective teacher agency may not only pertain to personal, collective, and institutional dimensions but also to broader systems such as the coursebook industry and societal discourses that permeate different spheres of education and the curriculum.

Whether the PSTs understood teacher agency as a tool for professional development or as a potent cannon to launch themselves into more critical territories, they shared a volitional approach to teacher agency, one which drives them to act, and in doing so they made teacher agency highly performative. As noted in this section, the students’ understanding of teacher agency evolved in tandem with their agency competence, beliefs, and personality as they developed professional knowledge about the language curriculum.

Teacher agency for diversity

By the end of the course, the PSTs had been provided with opportunities to develop their knowledge and use of key elements and perspectives relating to curriculum development and teacher agency. In their final essay, the PSTs utilized the conclusion to reflect on their intended use of teacher agency. We noted that in their writing, 154 PSTs used “teacher should”-statements (Extract 10), while 80 utilized “I”-statements (Extract 9), which may also indicate their different professional learning journeys and confidence with writing through a more personal voice (see extracts in this section).

As in the reflective blogs, the PSTs established links between teacher agency, their continuing professional development, and decolonizing the curriculum. In addition, other areas of interest were identified: gender diversity, intercultural awareness, and translanguaging. These depict the PSTs’ growing investment in considering the creation of diverse, inclusive, and multilingual learning spaces. For example, concerning gender diversity, Mia wrote in her essay:

In this essay I have proposed to use my teacher agency to address the unequal presentation of genders and stereotypes, which is not conducive to students’ construction of gender diversity (LGBTQ+) and the realization of inclusion and social justice. In my future teaching practice, I will give full play to my agency to make some changes by designing classroom activities and making adaptations and supplement to TESOL materials so as to guide my students to establish and enact the concepts of social justice and gender diversity. (Mia, Extract 9)

In the PSTs’ eyes, creating inclusive spaces extended to ensuring the recognition and celebration of multilingualism in the classrooms through topics, activities, and materials. Along these lines, a few of them reflected on intercultural awareness, as shown below:

Learning from the analysis above, teachers should use their teacher agency to promote different cultures and raise awareness of interculturality not only with other countries but also within China, to recognize the diversity around us. Teachers should have a critical and dynamic understanding of cultures to actively promote the training of this competence. Teachers should adapt or create tasks and materials to decolonize the curriculum by featuring local and international cultural identities and to make students know that language and culture are inseparable and that cultural differences are to be included in teaching and learning. (Hui, Extract 10)

Similarly, the course prompted the PSTs to find in their agency the opportunity to calibrate the curriculum to make it inclusive in terms of multilingualism. In particular, the notion of translanguaging as practice (Wei, Citation2018) and pedagogy (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2020) was envisaged as a potent way of harnessing multilingualism among and beyond learners. For example, a PST wrote:

In my future teaching, I will see myself as an agent of change who can adapt the top-down curriculum to allow my students to critically reflect on the formative value of all languages and the importance of using translanguaging to acknowledge different languages and dialects. I will also create opportunities for my students to use Mandarin or other dialects or languages in class to scaffold their own learning. Teaching English from a multilingual perspective is an agentive act of social justice, and I will work towards that aim. (Cindy, Extract 11)

Therefore, Extracts 9–11 suggest that as the participants reached the end of the course, they perceived themselves as agentically ready to promote advocacy for gender diversity, interculturality, and multilingualism. Compared to Davis and Howlett’s (Citation2022) study, advocacy included multilingualism but extended to other dimensions of inclusion, such as gender and culture. These findings may prompt us to speculate that having asked the PSTs to analyze curricula and textbooks from their contexts under the light of the contents covered in the course may have enabled them to become aware of the diversity of identities populating classrooms. Similar to the participants in Yangın Ekşi et al. (Citation2019) investigation, our PSTs developed a willingness to become projective agents of change in their context.

Discussion

This study sought to investigate how PSTs’ understandings of and construction of their own teacher agency as part of their future practices evolved in a course on second language teaching curriculum. Using Tao and Tao and Gao’s (Citation2021) trans-perspective understanding of teacher agency, the topics and activities included in the course highlighted the temporal dimension of teacher agency development.

At the start of the course, the participants exhibited a framed-in-the-past teacher agency which was characterized by limited opportunities to direct concerted changes given the extent and nature of their teaching posts and experience, which was minimal. Despite this contextual concern at the interactional seams between the institutional (macro) and the language teacher (micro) systems of teacher agency, the participants were able to acknowledge agency competence, i.e., teachers’ ability to make changes, whatever their size, in a context of top-down curriculum and national exams.

As the PSTs progressed through the contents of the course, they began to articulate a more nuanced understanding of general and personal beliefs about teacher agency in their context. As the data show, their sense of projective agency not only maintained features of agency competence but also incorporated agency beliefs and personality. The participants started imagining themselves as agentive educational actors while still recognizing policy-related constraints. Therefore, their framed-in-the-present understanding was orientated toward their future teaching posts. Differently put, their present conceptualization of teacher agency was built on their projective agency beliefs, competence, and personality in future teaching posts. Therefore, Goller and Harteis (Citation2017) multifaceted view of teacher agency could be enhanced by adding a temporal layer.

At the end of the course, the PSTs displayed new areas in which the course had influenced their projective teacher agency. They exhibited a willingness to engage in three interconnected agentic moves:

Self-initiated and collective professional development.

Reactive and proactive critical practices which incorporated a more sophisticated awareness of policies, coursebooks, and ideological forces within and beyond institutions.

Pedagogical decisions in favor of gender diversity, translanguaging, interculturality, and multilingualism.

Anchored in social justice, this last move not only embraced the micro- and macro-systems of language teacher agency, but it also acknowledged the power of language teachers engaging with others to construct collective agency for equity (Leal & Crookes, Citation2018; Peña-Pincheira & de Costa, Citation2021). Such recognition may suggest that as the course provided the space to develop professional knowledge about those topics (e.g., social justice, ideologies, translanguaging), the PSTs not only constructed a stronger sense of agency competence, beliefs, and personality about themselves; they also projected the same type of teacher agency onto their future colleagues.

Based on the temporal facet of teacher agency construction (Tao & Gao, Citation2021), represents the PSTs’ journey of projective teacher agency as they navigated the course on language curriculum development.

As discussed above, the PSTs’ experiences with agency in the past exhibited features of agency competence constrained by institutions, thus only establishing individual connections (teacher – the institution). However, as the PSTs developed professional knowledge of the language curriculum, their present understanding of teacher agency was influenced by their imagined sense of ability to self-direct language curriculum change (hence the arrow between present and future). Namely, their present agency was their projective agency. The professional knowledge developed in the course enabled the PSTs to articulate notions that showed a stronger sense of competence, beliefs, and personality, particularly around topics that favored social justice as a driving force in curriculum development and change. However, the influence was not unidirectional, as their understanding of curriculum change was also shaped by how they understood and projected their teacher agency in their future posts. In other words, teacher agency provided the PSTs with the opportunity to situate, localize, and reimagine their professional knowledge and practice around language curriculum development.

Conclusion

The present study shows that the interactions between professional knowledge and language teacher agency lend support to the view of the latter as highly relational and contextual (Kayi-Aydar, Gao, Miller, Varghese, & Vitanova, Citation2019). It also confirms that language teacher preparation may exercise a positive influence on language teachers’ understanding of teacher agency as encouraged in the literature (e.g., Tao & Gao, Citation2017; Wang, Citation2022; Yangın Ekşi et al., Citation2019). Despite these welcoming findings and contribution to the understanding of projective teacher agency, the study is not free from limitations. At a methodological level, the study could have included a more granular understanding of agency development by combining quantitative and qualitative research methods throughout the study.

In terms of implications, the study shows that the inclusion of a mandatory course on language curriculum, which provides an understanding of the organizing and macro-principles governing language teaching and learning may support teacher agency construction on the basis of professional knowledge and activities that incentivize PSTs to examine curricula from/for their contexts. However, we acknowledge that merely introducing new courses or augmenting existing ones with activities to promote teacher agency may be insufficient. Differently put, awareness of teacher agency does not necessarily enable it. Instead, a comprehensive transformation of language teacher education programs may be necessary, one that prioritizes the development of language teachers as individuals with distinct attributes and competencies, enabling them to autonomously shape their practice and professional growth. This entails fostering a sense of ownership and empowerment among teachers, enabling them to make informed decisions and author their pedagogical practices.

Additionally, approaching teaching about the language curriculum from a social justice and agentive perspective appears to allow PSTs to consider multilingualism as capital in the classroom. Hence, language teacher education programs at undergraduate and postgraduate levels may wish to pay attention to the systematic inclusion of these aspects in their curriculum and practices. At a research level, further research could follow the career of PSTs to investigate how they negotiate their projective teacher agency and their present agency when they obtain a full-time teaching post.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The x-axis shows the percentage of participants’ choices of each category (color-coded) on the Likert scale. The y-axis lists all items ranked by ranked by their scores. Specifically, the item at the top of the list (i.e., “.1 Teaching English”) was the one that students had the most experiences in and gave the highest scores, whereas the item at the bottom of the list (i.e., “6. Creating new programs for teaching English”) had the lowest scores indicating that students had the least amount of experience in the aspect.

2 The x-axis shows the percentage of participants’ choices of each category (color-coded) on the Likert scale. The y-axis shows the number of participants who chose a particular category on a particular item. The top row shows the items about students’ general beliefs about teacher agency (Item 1, 3, 7, & 8) and the bottom row shows the items about their specific beliefs (Item 2, 4, 5, & 6).

3 The x-axis shows the percentage of participants’ choices of each category (color-coded) on the Likert scale. The y-axis lists all items ranked by their scores within each perspective (General vs. Specific). Specifically, the items at the top of the list (i.e., Item 3 in the “General” category and Item 2 in the “Specific” category) were the ones that students were most positive about, whereas the items at the bottom of the list (i.e., Item 8 in the “General” category and Item 4 in the “Specific” category) had the lowest scores indicating that students had the most negative beliefs them compared to other items.

4 The model summary for the baseline GAM fitted to the ordered categorical belief ratings. The term s(ID) denotes the by-participant random intercepts, S(item) denotes the by-item random intercepts, and S(perspective, ID) denotes the by-participants random slops.

References

- Arcidiacono, C., Procentese, F., & Di Napoli, I. (2009). Qualitative and quantitative research: An ecological approach. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 3(2), 163–176. doi:10.5172/mra.3.2.163

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Banegas, D. L., & Gerlach, D. (2021). Critical language teacher education: A duoethnography of teacher educators’ identities and agency. System, 98, 102474. doi:10.1016/j.system.2021.102474

- Biesta, G., & Tedder, M. (2007). Agency and learning in the life course: Towards an ecological perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 39(2), 132–149. doi:10.1080/02660830.2007.11661545

- Bryer, J., & Speerschneider, K. (2016). Package ‘likert’. Likert: Analysis and visualization Likert items (1.3. 5)[computer Software]. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=likert.

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Pedagogical translanguaging: An introduction. System, 92, 102269. doi:10.1016/j.system.2020.102269

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). London: Routledge.

- Consoli, S. (2022). Practitioner research in a UK pre-sessional: The synergy between exploratory practice and student motivation. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 57, 101108. doi:10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101108.

- Consoli, S., & Ganassin, S. (2023). Navigating the waters of reflexivity in applied linguistics. In S. Consoli & S. Ganassin (Eds.), Reflexivity in applied linguistics: Opportunities, challenges, and suggestions (pp. 1–16). London: Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). New York: Sage.

- Davis, W. S., & Howlett, K. M. (2022). “It wasn’t going to happen until I made it happen”: World language teacher agency for multilingual advocacy. System, 109, 102893. doi:10.1016/j.system.2022.102893

- The Douglas Fir Group. (2016). A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal, 100(S1), 19–47. doi:10.1111/modl.12301

- Goller, M., & Harteis, C. (2017). Human agency at work: Towards a clarification and operationalisation of the concept. In M. Goller & S. Paloniemi (Eds.), Agency at work: An agentic perspective on professional learning and development (pp. 85–103). Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60943-0_5

- Kayi-Aydar, H. (2019a). Language teacher agency: Major theoretical considerations, conceptualizations and methodological choices. In H. X. G. Kayi-Aydar, E. R. Miller, M. Varghese, & G. Vitanova (Eds.), Theorizing and analyzing language teacher agency (pp. 10–21). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Kayi-Aydar, H. (2019b). A language teacher’s agency in the development of her professional identities: A narrative case study. Journal of Latinos and Education, 18(1), 4–18. doi:10.1080/15348431.2017.1406360

- Kayi-Aydar, H., Gao, X., Miller, E. R., Varghese, M., & Vitanova, G. (2019). Theorizing and analyzing language teacher agency. Eds. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Lasky, S. (2005). A sociocultural approach to understanding teacher identity, agency and professional vulnerability in a context of secondary school reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(8), 899–916. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.003

- Leal, P., & Crookes, G. V. (2018). “Most of my students kept saying, ‘I never met a gay person’”: A queer English language teacher’s agency for social justice. System, 79, 38–48. doi:10.1016/j.system.2018.06.005

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. New York: Sage.

- Liyanage, I., Bartlett, B., Walker, T., & Guo, X. (2015). Assessment policies, curricular directives, and teacher agency: Quandaries of EFL teachers in inner mongolia. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 9(3), 251–264. doi:10.1080/17501229.2014.915846

- Macalister, J., & Nation, I. S. P. (2020). Language curriculum design (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Melo-Pfeifer, S. (Ed.). (2023). Linguistic landscapes in language and teacher education: Multilingual teaching and learning inside and beyond the classroom. Cham: Springer.

- Miller, E. R., Kayi-Aydar, H., Varghese, M., & Vitanova, G. (2018). Editors’ introduction to interdisciplinarity in language teacher agency: Theoretical and analytical explorations. System, 79, 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.system.2018.07.008

- Molina, S. C. (2016). English language teaching in China: Teacher agency in response to curricular innovations. In P. C. L. Ng & E. F. Boucher-Yip (Eds.), Teacher agency and policy response in English language teaching (1st ed., pp. 7–25). London: Routledge.

- Peña-Pincheira, R. S., & de Costa, P. I. (2021). Language teacher agency for educational justice–oriented work: An ecological model. TESOL Journal, 12(2), e561. doi:10.1002/tesj.561

- Poulton, P. (2020). Teacher agency in curriculum reform: The role of assessment in enabling and constraining primary teachers’ agency. Curriculum Perspectives, 40(1), 35–48. doi:10.1007/s41297-020-00100-w

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. Bloomsbury Academic. doi:10.5040/9781474219426

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

- Selvi, A. F. (2020). Qualitative content analysis. In J. McKinley & H. Rose (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of research methods in applied linguistics (pp. 440–442). London: Routledge.

- Stelma, J., & Fay, R. (2014). Intentionality and developing researcher competence on a UK master’s course: An ecological perspective on research education. Studies in Higher Education, 39(4), 517–533. doi:10.1080/03075079.2012.709489

- Tao, J., & Gao, X. (2017). Teacher agency and identity commitment in curricular reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 346–355. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.01.010

- Tao, J., & Gao, X. (2021). Language teacher agency. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108916943

- Tutz, G. (2021). Hierarchical models for the analysis of likert scales in regression and item response analysis. International Statistical Review, 89(1), 18–35. doi:10.1111/insr.12396

- Vitanova, G. (2018). “Just treat me as a teacher!” Mapping language teacher agency through gender, race, and professional discourses. System, 79, 28–37. doi:10.1016/j.system.2018.05.013

- Wang, L. (2022). English language teacher agency in response to curriculum reform in China: An ecological approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 935038. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.935038

- Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9–30. doi:10.1093/applin/amx039

- Wood, S. (2017). Generalized additive models: An introduction with R (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Xu, J., & Fan, Y. (2022). Finding success with the implementation of task-based language teaching: The role of teacher agency. Language, Culture & Curriculum, 35(1), 18–35. doi:10.1080/07908318.2021.1906268

- Yang, H. (2012). Chinese teacher agency in implementing English as foreign language (EFL) curriculum reform: An activity theory perspective. University of New South Wales. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.4/52377

- Yang, H., & Clarke, M. (2018). Spaces of agency within contextual constraints: A case study of teacher’s response to EFL reform in a Chinese university. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 38(2), 187–201. doi:10.1080/02188791.2018.1460252

- Yangın Ekşi, G. Y., Yılmaz Yakışık, B. Y., Aşık, A., Fişne, F. N., Werbińska, D., & Cavalheiro, L. (2019). Language teacher trainees’ sense of professional agency in practicum: Cases from Turkey, Portugal and Poland. Teachers and Teaching, 25(3), 279–300. doi:10.1080/13540602.2019.1587404