ABSTRACT

Students with language and/or attentional difficulties are present in all classrooms, but evidence indicates they are poorly identified and supported. Reasonable adjustments are a legislative requirement, but these are often generic and fail to address instructional barriers. Students are uniquely placed to report on the pedagogical implications of language and/or attentional difficulties, however, little research has connected standardised assessment data to the classroom impacts of impairment as experienced by students. In this paper, we report on 59 students with language and/or attentional difficulties participating in a study aimed at improving students’ classroom experiences, engagement and academic achievement through accessible assessment and inclusive practice. We draw on standardised assessment and interview data to investigate similarities/differences in students’ language and/or attention profiles, and/or in what students’ wish their teachers knew about them and how they learn. Finally, we present a rationale for whole-class, accessible teaching practices as the foundation for classroom instruction.

1. Introduction

In accordance with Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD; United Nations, Citation2006), students with disability have a legal human right to quality inclusive education, which is defined as “… a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers” (United Nations, Citation2016, para 11). In Australia, barriers to access and participation in education must be addressed through the provision of reasonable adjustments as per the Disability Standards for Education 2005 (Cth), however, this approach has several limitations. Prior research has found that teachers’ ability to accurately identify relevant barriers for adjustment is poor and this can lead to misalignment (Glasby, Graham, White, & Tancredi, Citation2022; Harrison, Bunford, Evans, & Owens, Citation2013; Kern, Hetrick, Custer, & Commisso, Citation2019; Lovett & Nelson, Citation2021). Adjustments also tend to be generic and retrospective with additional time in exams (Lovett & Nelson, Citation2021), breaks during timed tasks (Ketterlin-Geller & Jamgochian, Citation2011), provision of a reader (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Capizzi, Citation2005), and preferential seating (Hart, Massetti, Fabiano, Pariseau, & Pelham, Citation2011) among the most frequently provided. Lastly, the process requires eligible students and the barriers they experience to be identified. This risks adjustments not being provided to students with common, but less visible disabilities, such as those with Developmental Language Disorder or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, who together account for around 14% of students (Graham & Tancredi, Citation2019). Students in both groups are poorly served in education and are overrepresented in academic underachievement, exclusionary discipline, early school leaving, and involvement with the justice system (Morken, Jones, & Helland, Citation2021; Stanford, Citation2020).

Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects language production and/or processing, which cannot be attributed to language exposure or other sensory or biomedical conditions (Bishop, Snowling, Thompson, Greenhalgh, & Catalise‐2 Consortium, Citation2017). Once referred to as “the most common childhood condition you’ve never heard of” (Norbury, Citation2017, np), DLD affects receptive and/or expressive language and each student’s profile is unique. Despite this heterogeneity, DLD typically results in difficulty with phonology (the sound system of language), syntax (morphology and spoken and written grammar), word finding and semantics (vocabulary, word meanings and word associations), pragmatics (the use of language to convey meaning in social contexts), discourse (the comprehension and construction of narrative, exposition, and conversation-level language), and/or verbal learning and memory. Students with DLD also often experience persistent literacy difficulties (McLeod, Harrison, & Wang, Citation2019) and academic underachievement (Durkin, Conti-Ramsden, & Simkin, Citation2012).

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is defined as a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that is atypical for the child’s developmental stage and which impacts functioning in at least two settings (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). It is the most frequently diagnosed childhood neurodevelopmental disorder and has consequently been described as a “household term” (Redmond, Citation2016b, p. 62). Underlying the externally expressed symptoms of ADHD are compromised cognitive mechanisms that can impact learning: working memory, self-regulation, inhibition and attentional control, planning, and information processing (Martinussen, Hayden, Hogg-Johnson, & Tannock, Citation2005). These impairments can make certain aspects of learning very challenging. For example, distractibility can make it hard to concentrate, and combined with working memory impairments, listening and reading comprehension may be compromised. Together these impairments make it very difficult to comply with classroom expectations, with many students with ADHD getting in trouble for “not listening” or “not following instructions” (Graham & Tancredi, Citation2019).

Although DLD and ADHD are distinct disorders, they are each associated with a constellation of impairments (Redmond, Citation2016a). Working memory deficits are common to both students with DLD and ADHD, and are known to contribute to functional impairments, including scholastic achievement and literacy difficulties (Martinussen & Tannock, Citation2006). Other skills impacted for both students with DLD and ADHD include vocabulary, spoken and written language comprehension, pragmatic language, and attentional control (Korrel, Mueller, Silk, Anderson, & Sciberras, Citation2017). Recent research comparing the structural language (vocabulary and grammar) and pragmatic language skills of primary school aged children with prior diagnoses of ADHD (n = 29) and DLD (n = 25) found that while vocabulary and grammar were more severely affected in students with DLD, students in both groups demonstrated significantly poorer skills compared to children without these diagnoses (n = 54; Vassiliu et al., Citation2023). There are also high rates of co-occurrence with Australian research finding up to 40% of students with ADHD also have a comorbid language disorder (Sciberras et al., Citation2014). Despite their prevalence, these students are often overlooked and the barriers they experience are poorly understood by educators (Glasby, Graham, White, & Tancredi, Citation2022; Gwernan-Jones et al., Citation2016).

To date, research on school students with DLD and/or ADHD has largely focused on educators’ experiences teaching students with language and/or attention disorders (e.g. Gaastra, Groen, Tucha, & Tucha, Citation2020; Keenan, Conroy, O’Sullivan, & Downes, Citation2019) or interventions to address impairments associated with vocabulary, comprehension, narrative, self-regulation, and memory (e.g. DuPaul et al., Citation2021; Sanchez & O’Connor, Citation2022). However, interventions tend to focus on remediation of students’ individual skill deficits. Within a multi-tiered approach, this may consist of withdrawal interventions for targeted (Tier 2) and intensive (Tier 3) support (Ebbels et al., Citation2019), as opposed to regular Tier 1 classroom instruction, and require students to be accurately identified through expert assessment which imposes time and cost burdens on families and schools. Identification of language skill deficits and diagnosis of DLD are typically conducted by speech pathologists using standardised direct measures that are decontextualised and conducted in clinical settings (Denman, Cordier, Kim, Munro, & Speyer, Citation2021). However, access to speech pathologists is inconsistent, with recent research demonstrating significant inequities and no or very limited government-mandated support for adolescents in some Australian states (Shelton, Munro, Keep, Starling, & Tieu, Citation2021). Assessment for and diagnosis of ADHD is conducted by paediatricians, psychiatrists, and/or psychologists (Australian ADHD Professionals Association, Citation2023), however government-funded services do not match service need, meaning services are typically conducted in the private sector (Australian ADHD Professionals Association, Citation2023). Should children require multidisciplinary assessment for both DLD and ADHD, wait times and expense are compounded. However, even if identification rates were to increase to capture those with DLD and/or ADHD, the number of students requiring intervention would outweigh the appropriately qualified school staff available to provide support (Law, Citation2019).

One benefit of standardised assessments is that they may alert educators that a student has language and/or attention difficulties, although educators do not typically have sufficient background knowledge to understand the implications of assessment data and nor does assessment data tell educators how best to adapt their pedagogy. Teacher knowledge about how to maximise the comprehensibility of instruction is critical, because barriers can be inadvertently imposed through teacher language choices, complex explanations, fast instructional pace, and insufficient lesson structure and sequence (Graham & Tancredi, Citation2023; Starling, Munro, Togher, & Arciuli, Citation2012). Pedagogical barriers such as these are heightened for students with impairments impacting comprehension, attention, and working memory, but are also likely impact students who do not have these impairments. Pedagogical refinements focused on comprehensibility can and should occur at Tier 1 to ensure all students can access age-equivalent core curriculum and advancement of academic, social, and emotional skills. Strengthening Tier 1 instruction is consistent with genuine inclusive education, where barriers are removed through “changes and modifications in … teaching methods” (United Nations, Citation2016, para 11). However, we know very little about the impact of instructional barriers from the perspective of students with language and/or attentional difficulties. To date, only a handful of studies have focused on students’ perceptions of teachers’ instruction and support for information processing and memory in the classroom (Connor & Cavendish, Citation2020; Graham, Tancredi, & Gillett-Swan, Citation2022).

In line with the principles of evidence-based practice, the perspectives, values, and expectations of end-users (in this case, students) must be considered alongside evidence and practitioner expertise (Roulstone, Citation2011). These principles apply equally in research with school students with impairments impacting language, attention, and information processing, who are trustworthy informants and can give accounts of what does and does not work to support their learning (McLeod, Citation2011). Positioning students in this way rejects assumptions “that they have no views to express; [or] … that their interests and experiences will always be best articulated by adult caretakers” (Byrne & Kelly, Citation2015, p. 197). Students are uniquely placed to report on the pedagogical implications arising from language and/or attentional impairments, but there has been little research to connect the information yielded from standardised assessment data to the impact of these impairments, as experienced by students in the classroom. Previous authors have pointed to these gaps, identifying that more research is needed to gain a qualitative understanding of the classroom impacts for students with DLD and ADHD (Vassiliu et al., Citation2023). In this paper, we combine data from standardised language and attention assessments with student interview responses to investigate similarities and differences in students’ language and/or attention profiles, and/or in what students’ wish their teachers knew about them and how they learn. We conclude with a range of evidence-based practices that align with students’ insights and which can be implemented in every classroom whether students have been identified with language and/or attention difficulties, or not.

2. The present study

The Improving Outcomes through Accessible Assessment and Inclusive Practices ARC Linkage study adopted a mixed-methods waitlist design in three Queensland state secondary schools to investigate whether accessible summative assessment task design – together with a two-stage pedagogical intervention targeting inclusive practice and Assessment for Learning pedagogies – improves outcomes for Year 10 students with and without language and/or attention difficulties. The doctoral study on which this paper is based is researching the classroom experiences and engagement of the subgroup of 59 Year 10 students with language and/or attention difficulties before and after their teachers participated in the inclusive practice intervention (Graham & Tancredi, Citation2023). Year 10 English was chosen as the focus for the study because it is a critical gateway to senior subject choice and participation in further education, employment, society, and culture. Also, as students in Year 10 have experienced multiple teachers across their 11 years of schooling and have likely been exposed to a broad range of practices, as well as barriers to learning in regular classrooms, they can provide insight to help improve the comprehensibility of Tier 1 classroom practice. This paper analyses data from the pre-intervention phase of the study in response to three research questions:

What is the distribution of impairments in language only, attention only, or both language and attention across the subgroup?

Which language and/or attention skills are most impacted?

What do these students wish their teachers knew about them and how they learn?

3. Method

All procedures in this research were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the associated institutional and national research committees. The study was approved by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Human Research Ethics Committee and approval to conduct research was obtained from the Queensland Department of Education.

3.1. Participants

All three participating secondary schools were in south-east Queensland and had the same Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEAFootnote1) range (1000–1100). Student participants were recruited via emails to parents by the participating schools resulting in 234 responses. Screening measures were used to identify a subgroup of students with language and/or attentional difficulties.

Parents/carers who consented to their child’s participation completed a questionnaire about their child, which included: (i) demographic information, (ii) number of years speaking English: (a) 0–2 years, (b) 3–8 years, or (c) 9 or more years, (iii) any history of language and/or attentional difficulties, and (iv) any pre-existing diagnoses of intellectual disability or vision impairment. Parents/carers were also asked to complete two screening measures: (i) the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy Skills Student Language Scale (TILLS-SLS; Nelson, Howes, & Anderson, Citation2016), and (ii) the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham questionnaire Short Form fourth edition (SNAP-IV; Swanson, Nolan, & Pelham, Citation1982).

The screening measures were completed in full for 234 students. Possible language and/or attentional difficulties were identified where the student:

did not have an intellectual disability or vision impairment, and

had spoken English for nine or more years, and

met the clinical cut off on the TILLS-SLS, requiring at least two items on the eight-item Language subscale having a score of below four (on a seven-point scale), and/or

scored in the moderate or severe range on the SNAP-IV, indicated by scores of 18 or more on the Inattention subscale, and/or

had a pre-existing ADHD or DLD (or similar) diagnosis.

Seventy students with likely language and/or attentional difficulties were identified from the screening data. Of these, 11 students changed schools or later withdrew consent.

The final sample included 59 students (Mage = 14.46 years; SD = 0.54), of whom 29 were female, 29 were male, and one identified as other. Just over two thirds (67.80%) had not previously had any investigation of their language and/or attentional skills. Only 10.17% had engaged in previous assessment for attention, 8.47% had engaged in previous language assessments, and 13.56% had engaged in both language and attentional assessments. Two students had a prior diagnosis of ADHD according to parent-report (3.39%) and one student self-disclosed an autism diagnosis. Five students (8.47%) were reported to speak both English (>9 years) and Japanese.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Test of Integrated Language and Literacy Skills (TILLS)

The TILLS (Nelson, Plante, Helm-Estabrooks, & Hotz, Citation2016) is a standardised assessment of curriculum-relevant oral and written language skills. All 15 TILLS subtests were administered with each student, then scored and analysed as per the assessment manual, where raw scores were converted to standard scores. TILLS subtests are scaled with a mean of 10 and standard deviation of 3 (average range 8–12). A composite TILLS Total score was scaled with a mean of 100 and standard deviation 15 (average range 86–114). For the subtests and total score, lower scores indicate greater impairment, however, no numerical cut offs or descriptive terms are available for severity ratings (Brooks Publishing, Citation2022). TILLS standardisation is based on a sample of 1,262 children (age six to 18) in the US between 2010 and 2015. Sensitivity and specificity of the tool is high for 14- to 18-year-olds (both sensitivity and specificity are 87%; Brooks Publishing, Citation2022). The subtests most relevant to the comprehensibility of classroom instruction are Vocabulary Awareness, Digit Span Forwards, Digit Span Backwards, Following Directions, Story Retelling, Delayed Story Retelling, and Listening Comprehension ().

Table 1. Description of TILLS subtests and Brown EF/A clusters most relevant to comprehensibility of classroom instruction.

3.2.2. Brown Executive Function/Attention (EF/A) Scales Student Form

The Brown EF/A Scales Student Form (Brown, Citation2019) is a self-report questionnaire, designed to evaluate daily behaviours that involve executive functions related to ADHD where students indicate whether various statements present “no problem” or a “small”, “medium” or “big problem” to them. As per the assessment manual, students’ self-ratings were converted to raw scores, T-scores, and percentile ranks for each of the six clusters (Activation, Action, Effort, Emotion, Focus, and Memory) and a Total Composite. T-scores have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 (Brown, Citation2019), and higher scores indicate greater difficulty. The Brown EF/A Scales were standardised on a sample of 1,950 parent, teacher, and self-report forms collected from the general population and with a clinical sample of 359 people with ADHD in the US. The psychometric properties revealed acceptable reliability and validity with internal consistency coefficients from 0.74 to 0.98 for the standardisation sample and 0.70 to 0.97 for the clinical sample (Brown, Citation2019). The most relevant clusters for students’ attendance to and processing of classroom instruction are Memory, Effort, Focus, Activation, and Action ().

3.2.3. Student interviews

All students participated in a 25-minute semi-structured interview on students’ experiences of school and the barriers that they face in the classroom. All interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. A staged approach to inductive content analysis was employed to identify categories of responses arising from the data (Berg, Citation2001). This paper focuses on the question, “Is there anything that you wish all your teachers knew about you and how you learn?” As students raised multiple points in the one response, each response was divided into discrete statements. When grouped by theme, three broad categories arose from the data: (1) teachers understanding the impacts of impairment, (2) students linking the impacts to barriers, and (3) practices students wish their teachers would use. Coding of interview data was conducted by the first author and categories were reviewed, cross-checked and refined in consultation with the second author.

3.3. Procedure

All 59 students participated in individual language and attention assessments using the TILLS and the Brown EF/A Scales Student Form. On a separate day, students participated in individual interviews. Student assessments and interviews were conducted by the first author or a trained research assistant (both certified, practising speech pathologists) in a small, quiet room at participating schools. The purpose of the research was explained to students and their consent was (re)confirmed at each data collection point. Students were assured that all data would be anonymised and reported using pseudonyms. On completion, students and their families were emailed a comprehensive assessment summary along with a range of strategies and adjustments to help teachers support those students in the classroom.

4. Results

4.1. RQ1. What is the distribution of impairments across the sample?

The TILLS Total score and Brown EF/A Total T-score were used to determine the distribution of language and/or attention difficulties across the sample. As shown in , the distribution of individual scores on the TILLS indicated considerable variability in the sample with most students (61.00%) scoring at least one standard deviation below the normative mean, where lower scores indicate greater difficulties.

Figure 1. Histogram indicating group distribution on the TILLS.

A range of scores was also observed on the Brown EF/A (see ), with approximately one-third of the sample (32.2%) scoring at least one standard deviation above the normative mean on the Brown EF/A, where higher scores indicate greater difficulties.

Figure 2. Histogram indicating group distribution on the Brown EFA.

While these analyses provide some indication of the severity of impairments across the sample, this may be complicated for individual students by the combination of both language and attention impairments. As our initial analyses could not show which students experience language difficulties alone, which experience attention difficulties alone, and which experience both, we created three categories based on TILLS standard deviations to plot the severity of difficulties experienced by students in the sample. These three categories were:

average language: TILLS Total score 86 or above

moderate language difficulties: TILLS Total score 71–85

significant language difficulties: TILLS Total score 70 or below

The Brown EF/A manual provides classifications for Total T-score ranges, and we used these to form four categories, where:

typical attention: T-score 54 or below

somewhat atypical (55–59)

moderately atypical (60–69)

markedly atypical (70 and above)

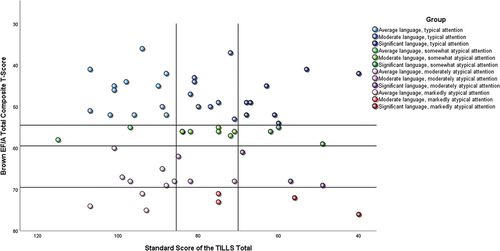

Scores on these two measures were visualised using a scatterplot (see ), in which each data point represents an individual student’s TILLS Total score (horizontal axis) and their Brown EF/A Total T-score (vertical axis). Both axes are reversed in direction, such that data points represent greater language difficulties moving from left to right, while from top to bottom, data points represent greater attentional difficulties.

As shown in , intersecting lines depict the 12 possible combinations of language and attention categories, and data points are colour-coded according to the combination of difficulties the student experienced, with severity increasing from left to right. Sixteen students demonstrated impairments in language (27.12%), 11 demonstrated impairments in the area of attention (18.64%), and 20 demonstrated impairments in both language and attention (33.90%). As depicted in the scatterplot, the severity of impairment in language and/or attention ranged across the sample. For example, in the top left-hand corner are 12 studentsFootnote2 who demonstrated average language and typical attention skills (20.34%), while the two students in the bottom right corner had a TILLS Total score of 70 or below and a Brown EF/A T-score of 70 or above placing them in the significant language difficulties/markedly atypical attention category. These standardised assessment composite scores provide useful information about the overall profiles of language and/or attentional difficulties of students in our sample, however subtests can better indicate which skills are impacted and the types of barriers these students may experience in the classroom.

4.2. RQ2. Which language and/or attention skills are most impacted?

TILLS subtest and Brown EF/A cluster scores were used to investigate the specific areas of language and/or attentional impairment within our sample. Of particular interest in this study were the subtests and clusters relevant to students managing the demands of classroom instruction, such as vocabulary, story retelling, language comprehension, working memory, focus, and effort. We therefore analysed student results on relevant TILLS subtests and Brown EF/A clusters for the students whose composite scores indicated impairment in language and/or attention (n = 47). One sample t-tests were used to compare the student sample to the normative mean on relevant TILLS subtests and Brown EF/A clusters. Due to mild non-normality in the distribution of scores on several subtests, all t-tests were bootstrapped with 2000 samples. Analyses were conducted in Stata, which reports bootstrapped t-test results as z scores. Effect sizes are interpreted according to Cohen’s convention (small: d = 0.2; medium: d = 0.5, and large: d = 0.8; Cohen, Citation1988).

4.2.1. Language

A range of scores was observed on each subtest (see ), with the greatest variability shown for Following Directions, Listening Comprehension, and Vocabulary, and a narrower range of scores shown for Digit Span Backwards, Story Retell, and Delayed Story Retell. All subtest sample means were significantly below the normative mean of 10, as indicated by one sample t-test results (see ). The greatest impacts were observed for Vocabulary Awareness, Story Retell, and Digit Span Forwards, each of which had large effect sizes exceeding 1, closely followed by Digit Span Backwards and Delayed Story Retell (above 0.8). The remaining two subtests of Following Directions and Listening Comprehension had effect sizes in the medium range.

Figure 4. Frequency of TILLS subtest standard scores.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and one sample t-tests on TILLS subtests.

4.2.2. Attention

There was a wide range of scores on Brown EF/A clusters (see ), with highest average scores (indicating greater difficulties) observed on the Memory and Effort clusters (see ). One-sample t-tests were significant for all clusters, indicating a greater degree of difficulties for the study sample in relation to the normative mean. The largest effects were observed for Memory and Effort (above 0.8), with the remainder showing medium effects (>0.5).

Figure 5. Frequency of Brown EF/A cluster T-Scores.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and one sample t-tests on Brown EF/A clusters.

Unpacking the TILLS and Brown EF/A data at a subtest and cluster level provides insight into the impacts of impairment and barriers that students likely experience. However, lived experiences of the interaction between the impact of language and/or attentional impairment/s, classroom instructional practices, and barriers to access are best shared by students themselves.

4.3. RQ3. What do these students wish their teachers knew about them and how they learn?

Fifteen of the 47 students with language and/or attention difficulties said that there was nothing they wished their teachers knew about them and how they learned. Two were more ambivalent in response, suggesting that their teachers already knew that they were “lazy” (Haruto) or liked “gardening and sports” (Jamie). Thirty students (63.83%) said there was something they wished all their teachers knew about them and how they learn. As some students raised multiple points, we divided their responses into 36 distinct statements. These statements were grouped and three categories arose from the data. The first category is that students would like teachers to understand the impact of impairment, the second is that impact severity is linked to the presence of barriers, and the third is about practices students wished their teachers would use.

4.3.1. The impacts of impairment

Twelve statements (33.33%) referred to students’ desire for teachers to understand the impacts of impairment. There were subtle differences between comments in this category. Some students intimated that they would like their teacher to understand the impacts of attention difficulties, with several students reporting that they “get very distracted” (Pippy). Other students gave more comprehensive examples that demonstrated the impact of distractions in the classroom. For example, Angie shared that classroom stimuli were distracting, but because teachers didn’t know about this specific impact, she used self-management strategies:

Um, I wish they knew about my wobbly leg and annoying noise situation, but I usually keep that on the down low. Usually … I just cover my face. So, like if there’s like a certain area, so say, I’m in the corner and then there’s desks all around here, I usually cover my eyes, like this.

Another student, Emily, spoke about the impacts of attention difficulties, which had implications for organisation and focus, saying “pushing everything to the last second. Always. ‘Cause I’m not mentally there most times. I’m, like, last minute”.

Other students spoke about the impact of processing difficulties, indicating they: “take longer to process” (Manalia) or “fall behind easily” (Iris). Flynn shared a similar sentiment, reporting: “I am a bit slower than everyone else”. Some students expanded on the impact of processing difficulties to include memory and comprehension, saying: “I’m like a slow learner. ‘Cause like I said, I forget things really easily” (Zoe) and “I don’t understand things” (Gabby).

Seth indicated that he did not feel the impact of impairment was well understood by his teachers, saying he wished he: “could get a, a proper diagnosis so that I could show the, my teachers of what, what’s wrong with my head and stuff. And so that they can understand what goes through my head”. While Seth believed a diagnosis might help his teachers to better understand him and how he processes information, Jaxon said that he wished his teacher knew what he found difficult, which speaks to the interaction between impairments and barriers, saying “I wish they knew that… Like, my learning barrier. Like what I find difficult. What I struggle with specifically”. The second category emerged from statements in which students made this link to barriers more directly.

4.3.2. The link to instructional barriers

Students most frequently responded to the question “is there anything you wish your teachers knew about you and how you learn” by linking impacts of impairment to barriers, totalling 16 of the 36 student statements (44.44%). In doing so, students most frequently spoke about barriers created by inaccessible explanations or instructions. While Ananya simply said “I kinda wish that people knew I didn’t, I don’t like listening too long”, Violet more explicitly linked the impact of impairment to an instructional barrier, saying: “I have a pretty short attention span, so you kind of can’t ramble on for too long, ‘cause then you just lose me. And I can’t really come back”. Other students implicated the linguistic complexity of classroom instruction but internalised this by saying: “I might need like, like, explaining it like, easier” (Emmett) and “Probably just need it dumbed down a bit” (Melissa). Meanwhile, Becky said: “it just takes time to understand”, which suggests that instructional pace and pausing may not provide students with the time they need process complex information.

In describing what they wished their teachers knew about them and how they learn, some students pointed to the need for repetition of information. While Verity said she wished her teachers would be “ready for me to when I have like really random questions or questions that they probably already answered, but I haven’t heard it”, Zoe said “I can’t just be told once”. Shevlin said he needed “repetition of more information and dates”, however, Julia qualified the need for repetition saying “sometimes they may need to like, repeat, and in a way I can understand”. This is an important point because, as Gabby explained, “sometimes the help is more confusing”. Repetition can help students who experience difficulties with attention, but repetition of linguistically complex or confusing information is no help at all. Lastly, in saying “I work better with visual representation mostly”, Aya made a connection between the impact of impairment and practices that support language and information processing. The latter is the third category described by students.

4.3.3. Practices students wish their teachers would use

The third category arising from the data encompasses eight statements (22.22%) from students who took the opportunity to suggest practices teachers could use to support their learning. Three students offered very general observations to help them maintain focus. For example, Parvati said teachers could be “probably just [be] more engaging” and Abel suggested teachers could “not to be, like, not enthusiastic about the topic. Just … don’t get boring about it”. Similarly, Aya suggested teachers could maintain students’ attention by “not, like, dragging it on”. Some students gave specific suggestions for how teachers could catch students’ attention and/or check their comprehension. While Keiko said “be more attentive. Check in with everybody”, Arjun was more expansive, explaining “I always need a double check on what they said, because I really wanted to be clear. And sometimes I just don’t hear it properly, so I think, just double checking with the students”.

Other strategies students said teachers could use related to support for information processing, such as providing “more time maybe” (Becky). Shevlin said that he wished his teachers would “provide examples and resources, I guess. Also, checklists, and also just sometimes like websites you could read or go watch for better understanding and stuff”. Lastly, Ruby said: “I want more structure. I want to know what is happening when, so I can plan up my time”. Her statement implicates the need for explicit lesson and unit planning with time keeping strategies that are shared with and modelled to students.

4.3.3.1. Did students with average language and typical attention say anything different?

As described in our earlier analyses of standardised assessment data, our participant sample also included 12 students with TILLS Total scores and Brown EF/A Total T-scores in the average range. We were interested to know whether these students responded to the interview question in ways that were similar or different to those with clinically significant difficulties. Five of the 12 students said there was something they wished their teachers knew about them and how they learn. These responses were divided into six statements (see ), which spoke to the same points raised by the 47 students discussed above. A similar distribution of responses is also evident, where the largest proportion of responses are statements that link the impact of impairment to instructional barriers arising from how information is presented in the classroom.

Table 4. Responses from students with average language and typical attention.

5. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the language and attention profiles of Grade 10 students, the impacts of these on learning, and barriers they experience in the classroom. Our analyses of composite scores on language and attention assessments revealed a range of language and attention skills. Although all 59 students were identified through screening measures, one in five (20.34%) did not demonstrate clinically significant language and/or attention impairments at the composite score level. Of the remaining students (n = 47), one in three demonstrated clinically significant impairments in both language and attention (33.90%), one in four demonstrated difficulties only in language (27.12%), and one in five demonstrated difficulties only in attention (18.64%). These findings align with previous research highlighting the common co-occurrence of and shared impairments between language and attentional disorders (Redmond, Citation2016a; Sciberras et al., Citation2014). With a combined prevalence rate approximating 14%, which equates to around four students in every class of 30, students with language and/or attention difficulties represent a large proportion of the school population. These students are typically educated in mainstream classrooms yet are not well served with high rates of academic underachievement, early school leaving, and involvement with the justice system (Morken, Jones, & Helland, Citation2021; Stanford, Citation2020). It is critical that their learning needs are better understood and barriers to their access and participation in the taught curriculum are addressed. Standardised assessment can provide some important information with respect to learning need, while students themselves can help in making the connection to the barriers that need to be addressed.

Our analyses of language subtests indicated significant impairment on key skills, including vocabulary awareness, working memory (digit span forward and backwards), following directions, story retell (immediate and delayed), and listening comprehension. Significant impacts were also observed across a range of attentional skills, encompassing memory, effort, focus, activation, and action. Across both language and attentional measures, the most impacted skills were vocabulary, working memory, story retell (reflecting comprehension of and verbal relay of information with coherency), and effort (involving the regulation of alertness, sustained effort, and regulation of processing speed; Brown, Citation2019). Notably, working memory was assessed both directly using the TILLS and through student self-report using the Brown EF/A, and both measures showed that students experienced a significantly greater degree of difficulties compared to normative means.

Students are best placed to report on the implications of these difficulties and during interviews, our participants advanced an understanding of the impact of language and attention impairments and barriers experienced in the classroom. A unique contribution of this research is that we asked both students with and without clinically significant language and/or attentional difficulties if there was anything they wish their teachers knew about them and how they learn. The distribution of statements across the three categories (teachers understanding the impacts of impairment, students linking the impacts to barriers, and practices students wished their teachers would use) held across both students with and without difficulties, with the link between impacts and barriers reported most frequently for both groups. Therefore, a novel contribution made by this research is that irrespective of profile, there were similarities in the impacts of impairment and barriers described by students, particularly relating to teacher instructional practices. These data suggest that accessible, whole-class instructional practices are important for both students with and without clinically significant language and/or attentional difficulties.

During interviews, students identified the barriers created through teachers’ use of long and/or complex explanations, referred to by one student as “over-explaining”. Some students also reported that teachers “ramble on”, which may result in barriers to students’ ability to sustain attention and effort. Similar sentiments reflected students’ experience of “boring” lessons that “drag on”, where teachers lacked enthusiasm, suggesting students are then required to work even harder to stay alert and sustain effort. These student reports align with previous research indicating classroom expectations (for example, sitting still, concentrating for extended periods, and lecture-style lessons) can create barriers for students with ADHD (Gwernan-Jones et al., Citation2016). Students in our study also identified that barriers arose from the linguistic complexity of teachers’ instructional language choices, which often took students time to process. Secondary school classroom instruction often presses hard on students’ grammar and vocabulary skills, where educators concurrently use new, low-frequency, subject-specific words, coupled with high-frequency, academic vocabulary (such as “analyse” and “calculate”), in the context of complex sentences, which are assumed to be comprehensible by students (Starling, Munro, Togher, & Arciuli, Citation2011). Such assumptions may result in linguistically dense instruction, including words that students simply do not understand.

The practice suggestions made by students in our study offer a way forward. Students were highly critical of lessons that “drag”, and this may occur because of poor planning and/or time-keeping and over-reliance on teacher talk. To prevent student confusion and fatigue, lessons should (1) progress at a moderate, but not fast, instructional pace, (2) be tightly structured to follow a logical and structured sequence with time built in for active student participation, and (3) support students to maintain focus through the use of strategies to capture, direct and maintain their attention (Graham & Tancredi, Citation2023). Students also spoke positively about teachers who were engaging and attentive, suggesting that multimodal teaching and using a visual scan of the class can help teachers to identify students who have not initiated class work or who need support with focusing or maintaining their attention. Students also shared their desire for teachers to use high-quality visual aids such as checklists, which can both help provide lesson structure and support working memory and long-term retention (Forsberg et al., Citation2021). Repetition of instruction was another practice that students said they wished teachers would use, likely because of the positive effects that repetition can have for refreshing information in students’ working memory and for transferring information to long term memory (Cowan, Citation2014).

Students in our study said that they wished teachers would “[explain] it like, easier”, which points to the importance of instructional language (both grammar and vocabulary) being comprehensible to students. Important new vocabulary must be explicitly taught to ensure students understand curricular content and/or instructional language. Further, when information is repeated, it must be done using words that are easily understood by students. This can be achieved when educators use words that students are familiar with (Graham & Tancredi, Citation2023). Students also spoke about the positive impact of “double checks” from their teachers, which helped them confirm they had understood their teacher’s intended message. Previous research has demonstrated the positive impact of teachers checking students’ understanding of content and concepts through questioning and feedback, as well as resolving problems if they arise (Harrison, Bunford, Evans, & Owens, Citation2013; Starling, Munro, Togher, & Arciuli, Citation2012). For comprehension checking to be effective, it needs to be used consistently and with all members of the class. Importantly, inclusive, whole class teaching strategies like repetition and comprehension checking are low-cost and do not require students to be identified or diagnosed and nor do they require standardised assessment. These cost-effective pedagogical refinements, when implemented consistently and effectively, have the potential to support the information processing requirements of all students in inclusive classrooms, not just those with language and/or attention difficulties.

5.1. Strengths and limitations of this study

A key strength of this study is the use of both standardised assessment and interview data from students with language and/or attentional difficulties, a largely under-researched group. By adopting a mixed-methods approach, quantitative and qualitative data were able to be integrated to investigate the constellation of language and/or attentional impairments for students in our sample and these students’ perspectives on the real-world impacts of impairment, as well as the barriers they face. A limitation of this study is the sample size, which limited the types of statistical analyses that could be conducted. Further research with larger samples is needed. Although this study aimed to recruit students from a range of backgrounds, only students from the partner schools were invited to participate and all students resided in South-East Queensland and the three schools had an ICSEA above the mean of 1000. While this does not indicate social-economic advantage, this research could be expanded into disadvantaged schools where there would likely be more students with language and/or attentional difficulties.

6. Conclusion

Students are well positioned to report on the impacts of language and/or attentional impairments and to identify the barriers they face in the classroom. Our study with 59 students united standardised language and attention assessment and interview data to map the distribution of language and/or attention difficulties across the sample and to examine similarities/differences in what students wish their teachers knew about them and how they learn. Students demonstrated diverse profiles, ranging from average language and typical attention to severe language difficulties and markedly atypical attention. A novel finding in this study is that irrespective of profile, students described similar impacts of impairment and barriers, particularly relating to classroom instruction. While some students have the resources to overcome these barriers, unaddressed barriers may have negative long-term consequences for students with language and/or attentional difficulties. The teaching practices suggested by students included greater support for vocabulary, information processing, attention, and working memory, all of which are proactive. Implementation of these practices can remove barriers before they occur and do not reflect costly nor substantive changes to current teacher practice. Critically, students do not need to be identified or diagnosed to benefit from these practices. Instead, proactive, consistent, accessible whole class teaching practices act as a safeguard, better enabling all students to manage the linguistic and cognitive load of learning.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Linkage Projects funding scheme (LP180100830). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Australian Government or Australian Research Council. Haley Tancredi is a doctoral candidate from QUT’s Centre for Inclusive Education and recipient of a QUT Postgraduate Research Award scholarship. We would like to thank the students who participated in this study for giving generously their time, insights, and perspectives. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. All schools in Australia are given an ICSEA score (mean = 1000, standard deviation = 100) ICSEA is a calculation of the relative affluence of the school community (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, Citation2020). Because single ICSEA scores could reveal the identity of the schools, ICSEA ranges from 2022 are provided, accessed from www.myschool.edu.au.

2. Despite composite scores not reaching a level of clinical significance, each of these 12 students demonstrated a degree of difficulty in two or more TILLS subtests and/or Brown EF/A clusters.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Australian ADHD Professionals Association. (2023). Submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs: Barriers to Consistent, Timely and Best Practice Assessment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Support Services for People with ADHD. https://aadpa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ADDPA-ADHD-Senate-Inquiry-Submission.pdf

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2020). Guide to understanding ICSEA. https://www.myschool.edu.au/media/1820/guide-to-understanding-icsea-values.pdf

- Berg, B. L. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Bishop, D. V., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., Greenhalgh, T., & Catalise‐2 Consortium. (2017). Phase 2 of CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(10), 1068–1080.

- Brooks Publishing. (2022). FAQs. https://tillstest.com/faqs/

- Brown, T. E. (2019). Brown executive function/attention scales. Bloomington, MN: Pearson.

- Byrne, B., & Kelly, B. (2015). Special issue: Valuing disabled children: Participation and inclusion. Child Care in Practice, 21(3), 197–200. doi:10.1080/13575279.2015.1051732

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Connor, D. J., & Cavendish, W. (2020). ‘Sit in my seat’: Perspectives of students with learning disabilities about teacher effectiveness in high school inclusive classrooms. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(3), 288–309. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1459888

- Cowan, N. (2014). Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educational Psychology Review, 26(2), 197–223. doi:10.1007/s10648-013-9246-y

- Denman, D., Cordier, R., Kim, J. H., Munro, N., & Speyer, R. 2021. What influences speech-language pathologists’ use of different types of language assessments for elementary school-age children? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 523, 776–793. 10.1044/2021_LSHSS-20-00053

- DuPaul, G. J., Evans, S. W., Owens, J. S., Cleminshaw, C. L., Kipperman, K., Fu, Q., & Benson, K. (2021). School-based intervention for adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Effects on academic functioning. Journal of School Psychology, 87, 48–63. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2021.07.001

- Durkin, K., Conti-Ramsden, G., & Simkin, Z. (2012). Functional outcomes of adolescents with a history of specific language impairment (SLI) with and without autistic symptomatology. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(1), 123–138. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1224-y

- Ebbels, S. H., McCartney, E., Slonims, V., Dockrell, J. E., & Norbury, C. F. (2019). Evidence‐based pathways to intervention for children with language disorders. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(1), 3–19. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12387

- Forsberg, A., Guitard, D., & Cowan, N. (2021). Working memory limits severely constrain long-term retention. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28(2), 537–547. doi:10.3758/s13423-020-01847-z

- Fuchs, L., Fuchs, D., & Capizzi, A. (2005). Identifying appropriate test accommodations for students with learning disabilities. Focus on Exceptional Children, 37(6), 1–8. doi:10.17161/fec.v37i6.6812

- Gaastra, G. F., Groen, Y., Tucha, L., & Tucha, O. (2020). Unknown, unloved? teachers’ reported use and effectiveness of classroom management strategies for students with symptoms of ADHD. Child & Youth Care Forum, 49(1), 1–22. doi:10.1007/s10566-019-09515-7

- Glasby, J., Graham, L. J., White, S. L., & Tancredi, H. (2022). Do teachers know enough about the characteristics and educational impacts of Developmental language disorder (DLD) to successfully include students with DLD? Teaching and Teacher Education, 119, 103868. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2022.103868

- Graham, L. J., & Tancredi, H. (2019). In search of a middle ground: The dangers and affordances of diagnosis in relation to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and Developmental language disorder. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 24(3), 287–300. doi:10.1080/13632752.2019.1609248

- Graham, L. J., & Tancredi, H. 2023. Accessible pedagogies. In L. J. Graham. Ed., Inclusive education for the 21st century: Theory, policy and practice. (2nd ed., pp. 198–221). New York, NY: Routledge

- Graham, L. J., Tancredi, H., & Gillett-Swan, J. (2022, June). What makes an excellent teacher? Insights from junior high school students with a history of disruptive behavior. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1–12. doi:10.3389/feduc.2022.883443

- Gwernan-Jones, R., Moore, D. A., Cooper, P., Russell, A. E., Richardson, M. … Garside, R. (2016). A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research: The influence of school context on symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 21(1), 83–100. doi:10.1080/13632752.2015.1120055

- Harrison, J. R., Bunford, N., Evans, S. W., & Owens, J. S. (2013). Educational accommodations for students with behavioral challenges: A systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 551–597. doi:10.3102/0034654313497517

- Hart, K. C., Massetti, G. M., Fabiano, G. A., Pariseau, M. E., & Pelham, W. E., Jr. (2011). Impact of group size on classroom on-task behavior and work productivity in children with ADHD. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 19(1), 55–64. doi:10.1177/1063426609353762

- Keenan, L., & Conroy, S.’ O’Sullivan, A., & Downes, M. (2019). Executive functioning in the classroom: Primary school teachers’ experiences of neuropsychological issues and reports. Teaching & Teacher Education, 86, 102912. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.102912

- Kern, L., Hetrick, A. A., Custer, B. A., & Commisso, C. E. (2019). An evaluation of IEP accommodations for secondary students with emotional and behavioral problems. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 27(3), 178–192. doi:10.1177/1063426618763108

- Ketterlin-Geller, L. R., & Jamgochian, E. M. (2011). Instructional adaptations: Accommodations and modifications that support accessible instruction. In Handbook of accessible achievement tests for all students (pp. 131–146). NEW York, NY: Springer.

- Korrel, H., Mueller, K. L., Silk, T., Anderson, V., & Sciberras, E. (2017). Research review: Language problems in children with attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder–a systematic meta‐analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(6), 640–654. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12688

- Law, J. (2019). Population woods and clinical trees. A commentary on ‘evidence‐based pathways to intervention for children with language disorders’. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(1), 26–27. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12424

- Lovett, B. J., & Nelson, J. M. (2021). Systematic review: Educational accommodations for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(4), 448–457. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2020.07.891

- Martinussen, R., Hayden, J., Hogg-Johnson, S., & Tannock, R. (2005). A meta-analysis of working memory impairments in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(4), 377–384. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000153228.72591.73

- Martinussen, R., & Tannock, R. (2006). Working memory impairments in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with and without comorbid language learning disorders. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 28(7), 1073–1094. doi:10.1080/13803390500205700

- McLeod, S. (2011). Listening to children and young people with speech, language and communication needs: Who, why and how? In S. Roulstone & S. McLeod (Eds.), Listening to children and young people with speech, language and communication needs (pp. 23–40). Guildford, Surrey: J & R Press.

- McLeod, S., Harrison, L. J., & Wang, C. (2019). A longitudinal population study of literacy and numeracy outcomes for children identified with speech, language, and communication needs in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 507–517. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.07.004

- Morken, F., Jones, L. Ø., & Helland, W. A. (2021). Disorders of language and literacy in the prison population: A scoping review. Education Sciences, 11(2), 77–102. doi:10.3390/educsci11020077

- Nelson, N. W., Howes, B., & Anderson, M. A. (2016). The integrated test of language and literacy skills student language scale. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

- Nelson, N. W., Plante, E., Helm-Estabrooks, N., & Hotz, G. (2016). The integrated test of language and literacy skills. Brookes Publishing.

- Norbury, C. F. (2017, September 22). Developmental language disorder: The most common childhood condition you’ve never heard of. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/head-quarters/2017/sep/22/developmental-language-disorder-the-most-common-childhood-condition-youve-never-heard-of

- Redmond, S. M. (2016a). Language impairment in the attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder context. Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research, 59(1), 133–142. doi:10.1044/2015_JSLHR-L-15-0038

- Redmond, S. M. (2016b). Markers, models, and measurement error: Exploring the links between attention deficits and language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research, 59(1), 62–71. doi:10.1044/2015_JSLHR-L-15-0088

- Roulstone, S. (2011). Evidence, expertise, and patient preference in speech-language pathology. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(1), 43–48. doi:10.3109/17549507.2010.491130

- Sanchez, V. M., & O’Connor, R. E. (2022). Improving academic vocabulary for adolescent students with disabilities: A replication study. Remedial and Special Education, 43(2), 87–97. doi:10.1177/07419325211016048

- Sciberras, E., Mueller, K. L., Efron, D., Bisset, M., Anderson, V. … Nicholson, J. M. (2014). Language problems in children with ADHD: A community-based study. Pediatrics, 133(5), 793–800. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3355

- Shelton, N., Munro, N., Keep, M., Starling, J., & Tieu, L. (2021). Clinical practices of speech-language pathologists working with 12-to 16-year olds in Australia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(4), 394–404. doi:10.1080/17549507.2020.1820576

- Stanford, S. (2020). The school-based speech-language pathologist’s role in diverting the school-to-confinement pipeline for youth with communication disorders. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 5(4), 1057–1066. doi:10.1044/2020_PERSP-20-0002

- Starling, J., Munro, N., Togher, L., & Arciuli, J. (2011). Recognising language impairment in secondary school student populations. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 16(2), 145–158. doi:10.1080/19404158.2011.586712

- Starling, J., Munro, N., Togher, L., & Arciuli, J. (2012). Training secondary school teachers in instructional language modification techniques to support adolescents with language impairment: A randomized control trial. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 43(4), 474–495. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2012/11-0066)

- Swanson, J. M., Nolan, W., & Pelham, W. E. (1982). The SNAP-IV rating scale. Irvine, CA: Resources in Education.

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Geneva: United Nations. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities

- United Nations. (2016). General Comment No. 4, Article 24: Right to Inclusive Education (CRPD/C/GC/4). https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1313836?ln=en

- Vassiliu, C., Mouzaki, A., Antoniou, F., Ralli, A. M., Diamanti, V., Papaioannou, S., & Katsos, N. (2023). Development of structural and pragmatic language skills in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 44(4), 207–218. doi:10.1177/15257401221114062