Abstract

Portugal took its first step in the systematization of sport with the advent liberalism after the French invasion began in 1808. The contact of the Portuguese military with the French and British was crucial to starting the development of national sport. After the confused period of the fall of the monarchy and the first republic, was the dictatorship of the Estado Novo that truly takes early control by the state in sport . The revolution that took place on 25 April 1974 was a radical change in approach over the sport and its development, particularly in the post- revolution where ideas were centrally controlled by the communist party- dictated laws. After the eighties of the twentieth century came to a trial period of adjustment with the European policies, yet being always subject to more situations than electioneering samples and properly directed at the development policies necessary.

Keywords:

Introduction

During the early part of the nineteenth century, Portugal moved from being a conservative monarchy to being a considerably more liberal society. The change was prompted in part by the slow emergence of an urban middle class, but much more significant was the invasion by French troops in 1808 who brought with them the liberal ideas that had informed the French Revolution (Birmingham Citation2003). The triumph of liberalism after the French invasion and the subsequent establishment of a constitutional monarchy opened horizons in Portuguese society not only in relation to politics but also in relation to ideas about education, which included ideas about the place of physical education in the school. The discussion of physical education was not only influenced by ideas from revolutionary France imported by French troops but also influenced by prolonged contact with the British military during the early years of the century.

During the nineteenth century, such discussion as there was of physical education was influenced by the interests of three distinct sectors of Portuguese society, namely, the military, the medical profession and educationists. However, the discussion was also affected by the oscillation, between liberal and conservative interests, in the control of government until 1926 when, due to a combination of persistent economic crisis and loss of public support for the republican government, a military coup took place, which began a period of military rule that lasted until 1974.

During this early phase in the development of physical education in Portugal, the discussions were non-scientific and tended to be more dogmatic insofar as the objectives were to align Portugal with the current scientific and educational practice and theory of European countries, particularly France and England, considered most advanced on the issue in question.

The army was the first institution that recognized the need to develop and implement a programme of physical education in its ranks due to the vicissitudes of the war between the liberals and the absolutists. In 1834, the Portuguese government called upon Francisco Amorós to go to Portugal to organize the physical education curriculum in the military academies. Amorós was a Spanish army officer who, after failing to implement his plans regarding physical education in Spain, went to France, where he was responsible for physical instruction in the army and was credited with the rebirth of the martial spirit in that country. He was responsible for the establishment of the Normal School of Civil and Military Gymnastics of France. Although these plans were not realized, for financial reasons, their influence was very significant within the Portuguese army, which incorporated many of the practices followed by the Normal School of France, particularly those developed by Amorós.

By 1851 the physical education programmes of the Army School included lessons in sword-fencing and in 1863 exercises in gymnastics were introduced. In 1868, similar activities were introduced into the Naval School, and in the 1870s these martial exercises and training were also introduced in the Military College which provided education for young secondary students, the majority of which followed a military career. In 1890, the School of Infantry and Cavalry Practice established in Mafra was earmarked for the education of staff recruited to the army, and the teaching of gymnastics, fencing and swimming formed part of the curriculum.

The first handbook for the teaching of gymnastics in military schools was published in 1896. Its author, an infantry lieutenant, D. Miguel de Alarcão, defined gymnastics as:

The science of rational movement and the study of its relationship with moral faculties. Therefore, it is the exercise of all organs of the body, systematic exercise and in harmony with certain rules and principles, a balancing of all the forces of the body. The school's gymnastics programme is divided into three phases: first, free gymnastics; second, gymnastics using mobile devices; and third gymnastics using physical apparatus. (Estrela Citation1972)

Gymnastics, reflecting the influence of Amorós, had a strong military character. The extent to which its objectives were defined by military priorities is clearly indicated in the Manual of School Gymnastic Practice, which notes that ‘The rationale adopted for gymnastics, the fundamental purpose for all exercises is that of the soldier without weapons.’

A second important influence on the development of Portugal's sporting culture was the medical sector whose influence had its origins in a primary concern with the maintenance of good health. Medical thinking at the time was heavily influenced by the prevailing European ideas about the relationship between exercise and health. The dominant influence at the end of the nineteenth century was the ‘Swedish method’ of gymnastics. The first course in Swedish gymnastics was taught in 1891 at the Real Gym Club. The availability of free courses and publications on this method led to its rapid spread in the physical education community. The Swedish method was developed by Per Henrik Ling, who was a gymnastics teacher and weapons expert. Although he was also interested in the preparation of soldiers, he developed a more balanced approach to physical training that sought to design a curriculum that combined gymnastics, health improvement and prophylactic elements.

A third influence on the development of sport was through the educational system. The introduction of sport into schools was prompted by health concerns, but took the form of gymnastics with a military orientation. At Real Casa Pia, one of the major schools in Lisbon, a programme of compulsory daily physical activities was introduced in 1838. However, it should be noted that pupils at these primary and secondary educational institutions were being prepared for recruitment to the army school of sergeants. The strong military theme to physical activity is clearly evident in this extract from the rules for the teaching of gymnastics at the Real Casa Pia, which lists as elements of the curriculum:

The teaching of gymnastic exercises with equipment, speed and endurance marching, jumping, fencing with a bayonet, fencing with a saber, foil and stick, horse riding, cycling, rowing and swimming exercises, exercises in fire-fighting including simulated attacks and the rescue of people, recitation, choral singing, instrumental music, war games, military exercises according to the ordinance adopted in the army (infantry, sappers and ambulance officers). (Estrela Citation1972)

As can be seen, there is a strong relationship between the gymnastics/physical education curriculum and military training. The impetus given to the spread of sport in schools through the rapid adoption of physical education programmes by education officials and influential individuals was not due solely to concerns with military preparedness and public health. Further momentum was provided by a concern to combat the ‘degeneration of the race’, which reflected the prominence of ideas about eugenics in the mid- to late-nineteenth century. After a number of false starts, approval was given by the House of Peers of the Kingdom in 1876 to make physical education compulsory in primary schools. However, it was only in 1880 that this law was implemented and even then its application was very limited due to lack of teachers, facilities and equipment.

Historical development of sport policy

1910–1940

After the installation of the Republic in 1910, education was one of the sectors that the new government prioritized, with physical fitness being one element that experienced sustained development. The Ling method was, at the time, widely accepted as a general basis for physical education, with the only differences in its application being modifications designed to support the specific objective to be achieved. With regard to doctors, mainly those located in Lisbon, the methods devised by Ling were implemented according to the current medical educational theory, which saw them as valuable in achieving a range of therapeutic goals.

The Ling principles remained dominant for many years and gained strong support from the Catholic Church, especially after the establishment of ‘Estado Novo’ (New State) in 1926 (Domingos Citation2010). The year 1932 was particularly important as a most significant law was passed that incorporated the landmark Rules of Physical Education in Secondary Schools. The training of gymnastics teachers had, since 1920, been based on the methods of Ling, which were consequently applied in the schools and supported by the Journal of the Regulations for Physical Education in the same year. These regulations and the resultant practices experienced only minor changes arising from teaching practice and from modifications in the Belgian colleges where the majority of trainee teachers were sent.

The popularity of the Ling technique and the expansion of physical education in schools led to the establishment of several schools for the training of teachers: the first being the School of Physical Education and the Society of Geography of Lisbon in 1930, followed in 1936 by the formation of the Organization of Portuguese Youth and later in 1940 with the creation of the National Institute of Physical Education (Crespo Citation1979).

As the Ling method was becoming more firmly established in schools, the military, which had been an early adopter, was moving to a form of military training and gymnastics that gave greater emphasis to military skills and that had been developed by the French army. The Estado Novo had the social control of youth as one of its objectives for sport, which it sought to achieve through the establishment of various organizations, such as Portuguese Youth, Portuguese Young Women's National Federation and Joy at Work, which sought to control the activities of youth and workers through their involvement in sport. The Estado Novo considered that the most appropriate form of sporting activity was the obligatory practice of gymnastics and the repression, or at least the discouragement, of the practice of sports, particularly team sports. The Rules of Physical Education in Schools of 1932 stated in the preamble that:

gymnastics training, since it is a powerful element of the education of the man, cannot fail to have intimate connection with the philosophy of education … Games in general, as a means of teaching and of achieving the universal character development that is desired, must be used with due caution, since their value is relative, and it should not be exaggerated. Games are an element of distraction and introduce many of the activities that boys tend naturally to take part in … [Yet] swimming, rowing and riding, following proper training have value and utility and generate benefits for hygiene which cannot be denied. However, the Anglo-Saxon sports and athletic games as well as the competitions and matches in general, especially in football, cannot be accepted because they are invalid even in their educational role and the harm is obvious. Physical education is not intended to train athletes and all physical education designed for this purpose is inappropriate education. The development of athletes marked the decline of great peoples. The Greece and Rome of the athletes represent precisely the decadence of Greece and Rome. Too many young men have been victims. It is important to remember this in preparing a new Portugal.

1940–1974

The regime of the Estado Novo, which lasted until 25 April 1974, continued, at least until the 1940s to attempt, through the creation of organizations, to control the activities of young people with the aim of preventing the association of people, which might form the basis for some form of political opposition to the regime. However, this strategy to prevent the development of popular team sports was unsuccessful, and football in particular was thriving throughout the country. The response of the regime was to seek to monitor and control the football clubs through the placement of police officers in the general assemblies of the clubs. But this strategy proved to be unsuccessful as football in particular achieved international success despite the lack of governmental support.

This pattern of international club and national team success in football continued into the 1970s and was largely unaffected by the rise to power of Marcelo Caetano who became Prime Minister in 1968. The period from 1968 to 1974 (when Caetano was overthrown) was referred to as the Marcelo spring as his appointment generated expectations within sport and among physical education teachers that policy of the state towards sport and physical education would move closer to the European approach to the development of sport. However, the strength of institutionalized conservative power meant that the anticipated opportunity for policy change with regard to sport failed to materialize. Although there were attempts to create new bodies to replace the powerful Portuguese youth organizations, the latter were never fully dismantled despite having lost their original purpose of the militaristic organization of Portuguese youth. Despite the creation of new laws and new state organizations, virtually nothing changed (Crespo Citation1978a,Citationb).

1974–1975

The 25 April 1974 marked the change of political regime in Portugal and the end of almost half a century of the undemocratic regime, the Estado Novo. The abrupt ideological change, especially after 11 March 1975, was in the direction of a political system in line with that of the Soviet Union, with the Portuguese Communist Party dominating the apparatus of the state. The Communist Party sought to extend its influence across all the social and economic sectors of civil society, including sport, in an attempt to create a state whose central characteristics followed the same communist guidelines. A clear definition of the model for developing the sport was expressed by the Director of Sports, Melo de Carvalho, who introduced radical changes in the existing sports model. Sport was now seen as a political resource in making progress to a socialist society.

The ENDO (the National Meeting of Sport Organizations), where Melo de Carvalho dominated the policymaking process, was the forum for professionals in the area of sport and was at the centre of the design of the new model of sport development. According to Melo de Carvalho

The most serious way to politicize the sport is to say that it has nothing to do with politics … The fight for sports development cannot take place in isolation but, like all sectors of social activity, must be based on specific evidence on what are, in essence, the cornerstones of truth: the means of production and the relations of production. This fight must be, of course, a struggle of a political character, that is, you have to focus decidedly on the fight which is antitrust [anti-monopolies] and anti-landowners. (ENDO Citation1975)

It was on this basis that a model for the development of a sports orientation of a popular character was developed. Sport programmes were to be consistent with the objectives of the government, which were expressed as follows:

The fundamental purpose of the revolution in sports is, therefore, the political struggle which reflects the priority of the emancipation of the proletariat from capitalist domination. But this process should highlight the fight in relation to two equally important tasks: – [first] to destroy the legacy of the fascist regime, so that sport also works as a key process in the education of the working masses, so that they overcome old habits that still permeate the lives of us all, – [and second] to build a new form of sport, capable of responding directly to the cultural, biological and psychological needs of the entire population. (ENDO Citation1975)

During this short historical period, physical activity reached all corners of the country. However, the objective of developing new cultural practices and habits was certainly not achieved – the results were largely ephemeral. Part of the explanation for the minimal impact of this initiative was the poor quality of the resources available and the absence of criteria to determine their distribution.

1975–1985

This brief period of radical leftist government was followed by a period during which economic and political stability was re-established in Portugal. Such was the seriousness of the problems facing the governments of the late 1970s and early 1980s that it is not surprising that little attention was paid to sport in debates on public policy. Indeed the period of communist government was followed by a phase characterized by substantial disinvestment in terms of government support for organizations and the practice of sport mainly motivated by political reasons, as the clubs were perceived as sources of counter-balancing power and agents of opposition to the state. Consequently, government enthusiasm and support was inconsistent, implemented in a haphazard manner and motivated by a purely partisan logic. The lack of a serious commitment to sport was reflected in the programmes of government where sport was mentioned only in one article of the constitution, article IX.

The election of the first majority government since the restoration of democracy in 1974 ushered in a period of stability in policymaking, and by the end of the 1980s there was a break with the inertia in sport policy through the publication, by the director of sport, of a policy document, Sport in the 1990s. The policy document included a Model of Sport Development, which defined for the first time a policy of development according to the latest trends developed in Western Europe.

Only now did the model of sport introduced after 25 April 1974 begin to be dismantled. The new model of sport development not only placed the encouragement of sports participation at the heart of policy but also stressed the importance of promoting the autonomous operation of the sports associations:

The essence of sports development is in ACTIVITIES, the crucial element of the process to which all others must contribute. The strategy aims to establish a system that ensures the promotion of social sport by the association itself. It is therefore necessary to ensure that the social system, stimulated by the state structure, is primed to ensure the growth and development of sport, but with a view to operating autonomously, and the gradual emancipation from the financial and social environment of state guardianship! In short, it is the obligation of the state to support the sports association, but not to replace them so that the activities to be undertaken must be promoted and stimulated by a widespread network of associations and supported and encouraged by the state without the state influencing their activities. (Former Sport Institute of Portugal (DGD, s/d))

This document Sport in the 1990s identifies three key objectives: (1) to generalize the availability and access to sport; (2) to facilitate a subsidiary model for the support of top-level sport; and (3) to contribute to the increase in the number of sports associations. In 1990, the government published the Law on the Sports System, Act 1/90, which, for the first time, defined the main features and objectives of the national sports system. The implementation of this law, despite its enormous importance, has never been effectively monitored and was delayed for more than a decade. The period since the passage of the law has consequently not seen the implementation of a comprehensive sports model, but rather a series of sporadic and uncoordinated government interventions.

An assessment of the contemporary situation of sport policy

The sporting potential of Portugal is far from being realized for two reasons: first, the inferior level of national sport literacy and second, the imbalance in the structure of provision. The latter is due to the lack of support from the government for local sport clubs and the expansion in the number of commercial facilities that, along with the promotion of sport events and the media, are consumed by higher income sectors of the population. As the economic crises deepened during the first decade of the new century, it is feared that an increasing proportion of the population will not be able to access sport and that the quality factors associated with local club sport will disappear. There is also the concern that local sports clubs will lose their experienced volunteers leaving only basic sport activities without the benefit of technical or social support.

In relation to high-performance sport, Portugal has produced a number of European and world-class athletes, but generally at the Olympic level the production of medals has been inferior to that of comparable countries in Europe. Portugal falls below the European level in terms of Olympic-level sports development expertise and success. illustrates the position of Portugal relative to a selection of other countries. The position of a country in the figure is arrived at by dividing total national wealth (as moderated by purchasing power parity (PPP) of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)) by the number of medals won at the 2000 and 2004 Olympic Games. As shows, small countries with population levels and wealth similar to Portugal have won medals more economically, for example, at a cost of less than US$ 40,000 million (PPP related to GDP) per medal. Portugal won one medal with a population of approximately five million at a PPP cost of US$ 100,000 million, indicating that the country is inefficient in its use of its demographic and economic resources and is not fulfilling its potential. To achieve the European average figures, Portugal should have won five medals in recent Olympic Games. However, the country only won two medals in Beijing in 2008.

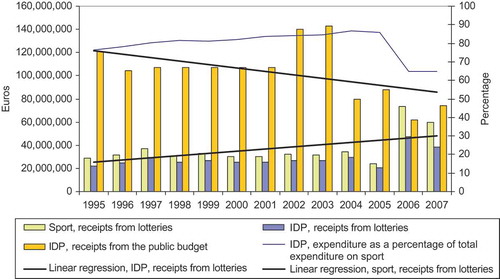

Turning to an analysis of community sport and its funding, it is clear that some European countries give sport significant sums from the national budget, independent of other sources such as local public expenditure or national lotteries. By contrast, the financing of Portuguese sport from the national budget and from the football pools (a form of lottery) is inferior to that of its European comparators. Even when the most recent lottery to benefit sport, the Euromillions, is taken into account, the overall conclusion remains unchanged (see ). provides information about the main sources of funding for sport and also the main trends since 1995. The main state agency for sport is the Instituto do Desporto de Portugal (IDP),Footnote 1 which receives significant finance from the state-owned pools which are managed by the Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Lisboa. The Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Lisboa also finances a range of other sports and sport-related activities including the administrative regions of Madeira and Açores Islands, the sport of football, the policing of sport events.

IDP promotes the high-level competitions of the national federations and approves the investment of local authorities in sport infrastructure. Sport development and recreation is promoted by local authorities, but generally only weakly, as their main concern is to generate and exploit the benefits arising from hosting sport events and high-level competition. In general, sport federations and public institutions lack the critical mass to produce the quality and quantity of grassroots opportunities that would bring Portugal closer to the European statistical averages for sport participation. The National Olympic Committee is also unable to lead the sport federations in building a better sport infrastructure from the grassroots to the top level. The exception is football, which is the subsector that has benefited from decades of high levels of public finance. The consistently higher levels of public funding for football have also tended to result in a concentration of talented players and trainers.

As regards funding for sport, identifies the following trends:

| • | The top line shows the money that goes to the IDP as a proportion of total expenditure on sport and shows a steady rise from 1995 to 2004, followed by a sharp decline to 2007. | ||||

| • | The two straight lines show the trends in the distribution of expenditure, with the top line indicating the steady decline in direct state finance and the bottom line the corresponding upward trend in reliance on funding from the lotteries (football pools and Euromillions). | ||||

| • | Of the three columns in each year, the left-hand column indicates the receipts by sport from the lotteries and the middle column indicates the lottery funding going to the IDP. Both sources of funding show significant increases in 2006 and 2007. | ||||

| • | The right-hand column indicates the sum received from the state. The steady decline is broken by 2 years, 2002 and 2003, which were exceptional insofar as they reflect the extra investment by the state in preparation for the Euro2004 football competition. | ||||

However, one problem with the growing reliance of sport on lottery receipts is that sport is only one of a number of services that compete for lottery funding. Other services include tourism, social security, education, health, youth work and other public sectors with sport having no objective advantage in this situation.

In conclusion it is clear that Portugal needs a new broad vision of sport to ensure sustainable growth. Sport is an attractive sector for investment, but it is important that potential investors are supported so that they can take advantage of the available opportunities. However, the present economic crisis has made the conditions for both public and private investment in sport even more difficult. The problem of stimulating investment is exacerbated by the gap between rich and poor which has widened over the last decade, one consequence of which is that the Portuguese sport system only meets the needs of the wealthy and healthy. It is impossible to build up a sport nation for only a part of the population. European history shows how great sporting nations built up healthy populations and globally competitive countries through a competitive sport industry, which comprises recreation for all, high-level competition and world-class professional sport.

Notes

1. Instituto Desporto Portugal (Portuguese Sport Institute).

References

- Birmingham , D. 2003 . A concise history of Portugal , 2nd , Cambridge : Cambridge University Press .

- Crespo , J. 1978a . Para uma Sociologia da Cultura. O Associativismo Desportivo em Portugal . Ludens , 2 ( 4 ) : 3 – 13 .

- Crespo , J. 1978b . “ Para uma teoria do desenvolvimento desportivo – A importância dos factores de natureza qualitativa no progresso do desporto de alta competição ” . In Antologia de textos desportivos de cultura portuguesa II , Edited by: Ludicus , H. and Lisboa . Compendium .

- Crespo , J. 1979 . As Instituições de Educação Física e Desportos e a ideologia em Portugal, no período de 1926 a 1942 . Ludens , 2 ( 3 ) : 51 – 53 .

- Domingos , N. 2010 . Building a motor habitus: physical education in the Portuguese Estado Novo . International review for the sociology of sport , 45 ( 1 ) : 23 – 37 .

- ENDO . 1975 . Encontro nacional do desporto. Conclusões , Edited by: Lisboa . Centro de Documentação e Informação da DGD .

- Estrela, A., 1972. Elementos e reflexão sobre a educação física em Portugal, no período compreendido entre 1834 e 1910. Boletim Do INEF, v.1, n (1–2), jan./jun. Separata. 2a série.