Abstract

Venezuela, a vibrant and dynamic country located in the northern part of South America, is the fourth largest producer of oil in the world. It has a population of 26 million and has relatively low levels of illiteracy. It was a colonized country until it was freed by Simón Bolívar (the national hero), who led the war of independence not only in Venezuela, but also in a number of other South American countries. Since that time, Venezuela has experienced political instability like many of our Latin American neighbours (Galeano Citation1995). Currently, Venezuela is the longest lasting democracy (since 1958) in Latin America. Although it has a strong tradition of government funding in all sectors of society, including sports, and a remarkable interest in baseball (its number one sport), Venezuela is not considered a sportive nation.

Keywords:

A brief history of government involvement in sport

The development of sport practices in Venezuela reflects its colonial history. It is indeed true that some forms of physical activity and/or sport practice were present within the pre-colonial indigenous society; nevertheless, the economic transformation that occurred in the country in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, particularly after the discovery of oil, contributed to the development of some specific sports (e.g. baseball and softball), mostly because of the influence of American culture, that came along with oil exploitation, and also as a result of the European immigration that brought other sports such as soccer and fencing. Curiously even though soccer was the first to be practised in this country (Flamerich Citation2005) it was baseball that became our national sport.

Different sport disciplines started to be practised long before the government was directly involved in their development (see ). Initial government involvement occurred in 1921 when the Ministry of Public Instruction (later retitled Ministry of Education) established physical education (PE) as a compulsory element of the school curriculum for boys and girls (García and Rodríguez Citation2002) which had the effect of making sport more accessible to a broader population. Before this decision sport practice had been a privilege for those who could afford it. Indeed prior to 1921 participation in organized sport in Venezuela depended on the sponsorship of private organizations. It was not until problems relating to participation in international sport competitions started to occur that the need to create a national organization was acknowledged. Consequently, in 1935, more than 60 years after the practice of sport (competitive sport) had started in Venezuela, the Venezuelan Olympic Association, which was later renamed the Venezuelan Olympic Committee (COV), was founded. COV was recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1938 a year that can be considered the starting point for the creation and development of official sport organizations such as associations, confederations and leagues. It was also in this same year that the first Venezuelan sports delegation participated in an international event, the IV Central American and Caribbean Sports Games. However, despite some signs of government interest in sport sports development was supported by private finance initiative throughout the 1940s.

Table 1. Chronology of the development of sport and the establishment of sport organizations in Venezuela

It was 14 years after the creation of COV that the national government (a military government) founded the National Institute of Sports (IND) under decree number 164 on 22 June 1949. Its purpose was to manage, plan, stimulate, protect, promote and supervise all sport activities in the country. This autonomous institution, the highest authority in sports, was established as a branch of the Ministry of Education. It later became part of the Ministry of Youth Affairs, renamed, a few years later, Ministry of the Family; then, it was attached to the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (later labelled Ministry of Education and Sports). Today, the IND is attached to the Ministry of the Popular Power for Sports (MPPD) (Ministerio del Poder Popular para el Deporte).

Until 22 June 1949 sports participation was not considered to be a government responsibility with the consequence that private institutions took charge of planning and organizing all sport activities under the supervision of COV. Many authors consider this year, in which IND was established, to be the beginning of contemporary sport practice in Venezuela (see, e.g. Segovia Citation1985). Since then the IND has been the bridge between government and the sport federations and other sport organizations and there has been a gradual increase in the dependence of private sport organizations on national government resources.

The creation of the IND led to changes in the operation and organization of pre-existing organizations as a more coherent national structure began to emerge. Some of these private organizations, previously called national or athletic associations, in regions or states, changed their names while others disappeared. Accordingly, the title of ‘Federation’ was used to identify former organizations and associations at the national level. These Federations in turn started to organize ‘Associations’ in every state (López de D'Amico and Ramírez Citation2008). With the resources provided by the government through the IND to the emerging sports sector, an era of public investment in sports management began which accelerated the organization of different sport disciplines. By 1949, nine federations had already been constituted under the structure shown in

Sport policies – key legislation

In terms of key Venezuelan legislation, it is notable that the oldest document highlighting the importance of PE had been presented to the Angostura Congress by Simón Bolívar in 1819.Footnote 1 In article one of this document, called ‘Moral Power’, it is established that the Education Chamber be in charge of the PE of children from birth up to the age of 12 (Ramírez Citation2009). Although this document was included as an appendix to the Venezuela's second National Constitution, these notions do not appear in subsequent constitutions until that of 1999. There were some regulations and laws established to support the practice of PE in school but not in the National Constitution.

In 1897, ‘gymnastics’ was first included in the Code of Public Instruction as a compulsory course, indicating this was the same form of PE that Simón Bolívar had already referred to. In article 24 of the 1915 Law of Public Instruction, general gymnastics and sporting games were established as compulsory subjects (Castillo Citation2004). Later, in 1921, the Ministry of Public Instruction approved a resolution by which PE became a compulsory activity for boys and girls at school. However, at this time there were not enough PE teachers in the country and a degree in PE was not available at university level. In 1922, the first Regulation in PE was approved. It was modified twice: in 1932 and in 1940. In the 1940 version, a minimum of 18 years of age and credentials in the area of expertise were required to be able to work as a PE teacher. In 1948, the first PE Department was created at Instituto Pedagógico de Caracas (Teachers Training Institute of Caracas).

The IND was created by the military government in 1949 after a decision of the executive (rather than the legislature), so there were no laws to support sport practice. It was a decision that was necessary because Venezuela was about to host the third Bolivarian Sport Games in 1951. However, it was not until 1971, 22 years after the creation of the IND, that the Institute acquired official status, once its creation was approved by the National Congress (Castillo Citation2004). It is important to add that sports commissioners, who had first been appointed in each state since 1950s, became regional sports directors in the 1960s, so each state began to establish a Regional Institute of Sports (known as Regional IND) accountable to the IND.

Between 1949 and 1971 several legal instruments were approved in order to plan and regulate sport development in the country. Among the most relevant was the creation of the National Sport Games in 1959 which was to become the most important national sports event in which all the states would participate. It was indeed the first major intervention designed directly to influence sport development in the country. The contest was held every 2 years (UPEL Citation1990). Even though this national event is still held every 2 years under the same name, its rules have been modified, but it remains the most important national sport event.

The first Sports Law was approved in 1979 and the most important subsequent regulation was approved in 1981. With these approvals, clearer guidelines for sport development and a more coherent organizational structure for sport were provided as summarized in

During the 1970s a major disagreement between COV and the IND arose, because the former claimed that the government was interfering in COV decisions. However, the criticism failed to acknowledge the role of the government in supporting the participation of national teams in international events. COV expected the IND to act as just a financial resource. However coaches and athletes were less critical of the intervention of IND as many were more concerned with what they considered to be the abuse of power by the federations which often interfered in team selection, decisions about which staff would accompany athletes to competitions and even highly technical matters of training all of which coaches considered to be their areas of expertise. This confrontation reached the IOC when the president of COV threatened to terminate Venezuela's affiliation to the IOC due to an alleged lack of freedom from interference by the state. Eventually, after discussions between government representatives and IOC President Brundage, the Minister of Education agreed with the president of COV to recognize the National Olympic Committee's autonomy (Castillo Citation2004). As a result the threat of disaffiliation from the IOC was lifted.

The 1979 Sports Law highlighted several significant issues. Among them, sports practice was included as a requirement at all educational levels; it also regulated the time between elections for officers of sport organizations, the autonomy of the private sports sector and the conditions for obtaining financial support from the state. The right of the military and workers to participate in sport activities was also recognized. The rights of athletes to participate in sport competitions or special training sessions as well as their right to be on leave from their place of employment when necessary were acknowledged. The following year, in 1980, the Education Law emphasized the compulsory nature of PE and sports at all levels of the educational system. However, despite these laws, even nowadays athletes often have to argue with teachers and/or professors to be granted their rights.

One of the saddest chapters in sport education is that the National Coaches' School that had opened in the 1960s was closed in the late 1970s. The closure of the school created a chaotic situation the consequences of which are still felt today in coaching education. The closure also caused changes in the PE syllabus not just at the university level, but at junior school and high school levels as well, which, in turn, had negative consequences for the sports sector (López de D'Amico 2008).

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, decentralization of power was a national policy which also affected the sports sector. The IND transferred its sport facilities to their corresponding territorial authority at state and municipality levels. All members of the coaching staff were dismissed and the administrative personnel was relocated in regional offices. The states and/or municipalities took up the responsibility for hiring their own staff. This situation caused a great deal of instability; however, some states started to establish their own state foundations to take charge of local sports activities. Later some of the state foundations became State Institutes of Sport that were and still are fully dependent on regional state budgets.

These changes laid the foundation for a new Sports Law and a new set of regulations in 1995 and 1996, respectively. However, contrary to expectations, the new law proved it was no more effective than the previous one due to several contradictions. First, the private sector acquired more rights than the governmental organizations; the law granted the former greater independence in the use of the financial resources coming from both the national and the local governments. A second contradiction was that coaches were to be hired by the private sector (associations and/or federations) which, in turn, would receive the money from the government, that is, financial transfers from IND to the federations and, at the state level, from Institutes of Sports to associations. This left coaches legally and socially unprotected, because they had neither social security nor job stability. In addition, the government could hardly supervise performance or set performance targets as it was not their direct employer. This, among other contradictions, was not identified at the time perhaps due to all the changes that were taking place during the same period. Nevertheless, it was obvious that the government (whether national or regional) although financing sport was unable to hold the private organizations to account (López de D'Amico Citation2009b).

Unfortunately, even though three different, and widely supported, proposals for a new Sports Law have been presented to the National Assembly their discussion has not yet generated a new legal instrument. Consequently, the 1995 Sports Law is the one still in force despite the fact that the current law contradicts the national constitution, in force since 1999, which was approved by a majority of Venezuelans in a national referendum (Constitución de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela Citation1999) and that it does not embrace the spirit of the major socioeconomic and sporting changes that have been taking place in the last 10 years. Among the reasons for the failure to replace or amend the 1995 Sports Law is that the private sector has not shown much interest in a new law.

The 1999 Constitution recognizes participation in PE, sports and recreation as a social right (article 111). It is important to note that this article emphasizes that the government should provide support for the ‘Sports for All’ programme as well as for elite sport. This article provides one of the most explicit acknowledgements of the sports sector in a public policy document. Fortunately, other laws recently approved do recognize the need for the practice of sports and physical activity. In articles 63 and 64 of the Organic Law for the Protection of Children and Teenagers (Ley Orgánica para la protección del niño y del adolescente Citation1998, LOPNA) the rights to recreation and the practice of sports and games are recognized and the responsibility of the state to provide appropriate facilities for these purposes is established. In several articles, The Organic Law of Education (Ley Orgánica de Educación Citation1980, Citation2009) states that the practice of PE and sports at all levels is obligatory. In some of its articles, the Organic Labour Law (Ley Orgánica del Trabajo Citation1997) also acknowledges the right all workers have to participate in sport activities and establishes that the state must make sure that sport organizations, both public and private, fulfil their responsibilities concerning the promotion of physical activity and/or the practice of sports among their employees. The Law for People with Disabilities (Ley para las Personas con Discapacidad Citation2007) stresses the right of disabled people to do physical activity and/or sports. The growing importance of sports in Venezuela during the last few years is reflected in its current ministerial status. The creation of the Ministry of Sports has raised the issue of sports practice (both community sports participation and elite sport development) to unprecedented levels indicating clearly that sports practice is regarded by the present administration as a priority and is discussed in more detail below.

While there has been substantial progress in creating opportunities for community participation (Sport for All) there has also been progress in more specialist areas such as the professionalization of management in relation to PE and sport. For example, various programmes that have been created to promote the education of professionals for the improvement and development of the sports sector, through international cooperation (e.g. Agreement with Cuba) and scholarships for Venezuelans to be able to join both undergraduate and graduate programmes (masters and doctorates) in PE and Sports offered abroad. Besides these substantial accomplishments, the creation of the Ibero-American Sports University in 2006 (today's Sports University of the South) (López de D'Amico Citation2006) may be considered the most outstanding achievement. It welcomes both national and international students to whom it offers three different undergraduate programmes. In summary, the impact of governmental support on sports' management, planning and organization during the last 10 years has been remarkable. However, as mentioned above, the approval of a new Sports Law that encompasses all the major issues concerning sports and physical activity policies, as well as those rights and duties that have been briefly outlined in other laws are an absolute necessity.

Current administrative structure and funding

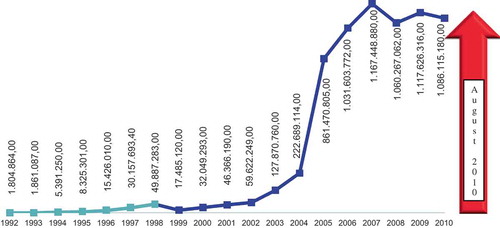

The current administrative structure (see and ) is headed, at the national level, by the MPPD which contains two vice ministries, one of which is responsible for the development of mass participation in sport and physical activity and the other, responsible for high performance sport. Administrative responsibilities are shared between the MPPD and the IND. However, since the creation of the Ministry of Sports in 2008 determining the distribution of functions has been a complex task. In the past, funding for recognized national sports federations came from the IND. Nowadays, it is provided by the MPPD ( and ) and financial support goes straight to national teams representing Venezuela in international events (championships and games) as well as in domestic contests, at all levels, organized by the federations or national games. At the state level (24 states in total) the Regional Institutes of Sport and/or Sports Foundations support financially the development of state teams from initial stages (e.g. youth development squads) through to high performance levels as well as sports mass participation programmes.

Figure 6. Financial support from the government [National Institute of Sports (IND)/Ministry of the Popular Power for Sports (MPPD)] to the Venezuelan Federations Ministerio del Poder Popular para el Deporte (Terán 2010).

![Figure 6. Financial support from the government [National Institute of Sports (IND)/Ministry of the Popular Power for Sports (MPPD)] to the Venezuelan Federations Ministerio del Poder Popular para el Deporte (Terán 2010).](/cms/asset/7daaa487-4df2-4a6c-bb18-db5e79f563d9/risp_a_627364_o_f0006g.jpg)

At the local level, the Municipal Institutes of Sports, the Sport Directorates or Sports Programmes are the organizations responsible for the development of physical activity, ‘Sports for all’ programmes and sports at the initial stages (i.e. for young people). Again, at this organizational level, funding is provided by the state through each municipal government.

As mentioned above, both the private and the public sectors () work in parallel for the development of Venezuelan sports according to the current Sports Law (Ley del Deporte Citation1995). Private organizations such as clubs, associations, federations and the COV are autonomous in their administrative, as well as in their technical, decisions. The government is not involved in decisions concerning the selection of teams to represent the country in international contests or the production of the annual sports calendar. However, it fully supports the organization of all international events held in the country and the participation of national teams. Recent examples include the organization of the Women's Pan-American Softball Championship in 2009, the Female Baseball World Championship in 2010 and the American Soccer Cup in 2007.

The private sector's autonomy has also left the government without much influence whenever coaches, athletes or even referees disagree with their boards' decisions. There are even cases in which an Association, recognized by a Regional Institute of Sport, is not recognized by a Federation. For the election of the Federation Board which takes place every 4 years, only one representative per Association has the right to vote. These boards are basically constituted by volunteers and re-election is common. It is interesting to note that in a study of Venezuelan managers' profiles, most of them acknowledged that their fees for trips and other expenses depended significantly on the funding the federations receive from the government (López de D'Amico Citation2009a).

The private sector is heavily sponsored by the government. Annually, all federations are given money to organize national championships, to finance the participation of athletes in international competitions and to pay coaches' salaries among other responsibilities (). The budget varies depending on the sport calendar and/or the year of the Olympic cycle. The government is also responsible for furnishing the teams with the necessary equipment and for maintaining sports facilities in which case, the amount of money allotted varies depending on whether it is a national, state or municipal facility.

The funding for sport comes from the national budget which mostly depends on oil production. Currently, there are no policies concerning financing sports with funds coming from general taxes or taxation on lottery. There was an experience in Cojedes State in which a percentage of the money collected through the highway toll was used to support the organization of the National Sports Games in 2003. The federations and associations do a very poor job in terms of fund raising. They depend heavily on governmental support. Just a few of them, the soccer, karting, surf and the Coleo (a traditional sport) federations, have worked in order to raise their funds.

In recent years, some government-owned companies have supported sports such as soccer and athletics. In addition, some private companies have championed the development of sport; however, this patronage is still very limited. In some of the laws currently in force, private companies are encouraged to contribute some kind of social service to the nation. This contribution would vary according to their annual income (Ley Orgánica de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación 2006). Through this policy, the state aims to provide a foundation for increasing the volume of sport funding coming from the private sector. Furthermore, as for sports-related research, article 42 of the Law for Science, Technology and Innovations (Ley Orgánica de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Citation2006) establishes that, depending on their annual income, companies must devote 0.5–2% of their budget to support officially certified projects, laboratories, equipment and academic programmes concerned with physical activity and sports.

Providing integral support to athletes is a major objective of the national sports programme. Accordingly, those who belong to a national team are now granted regular financial support in the form of academic scholarships, medical care programmes, room and board (if needed) and so on. Many states also provide the same benefits to their athletes. In 2010 the MPPD provided 1231 scholarships and 101 grants for economic support (Terán 2010). At the regional level, in Aragua State, for example, 620 scholarships were given to athletes in 2010 (López de D'Amico Citation2010).

Emerging issues in public sports policy

It is important to acknowledge that some of the existing policies on sports have a strong potential to bring about meaningful and positive changes to the sports sector in the near future. These changes not only involve elite athlete performance, but also professional training at university level, facilities, budget allocation increases and more social programmes to guarantee athletes' holistic development. Indeed, all these changes are contained in written policies and many of them are actually taking place. Nevertheless, the huge social debt accumulated over many years cannot be paid off in a short term. In addition, the poor control exerted by the state on sport development has prevented the country from obtaining better results in all areas. It is not enough to provide the federations with resources; close supervision of where the funding goes and how it is administered, as well as a permanent campaign to encourage sport officials and institutions to seek resources from sectors other than the government are important requirements.

The fact that the Sports Law has not yet been amended is a major problem that has affected the development of sport.Footnote 2 The participation of stakeholders in decision making is minimal, which contradicts the spirit of the changes that are occurring in the country. Athletes, coaches and referees' opinions are hardly heard and, when heard are, in most cases, completely ignored.

The government should no longer be just a major financial provider and observer while federations and associations continue to play their traditional role as mere official fund recipients. Instead, the private sports sector should work in order to gain the independence they desire (and which they claim is constrained by government) by raising more of their budget from non-government sources.

Finally, maintaining a clear national policy that guarantees continuity of sports programmes is essential. Furthermore, since the articulation of the public sector, at all levels of sport management, is very poor, it is necessary to urge the public entities to strengthen their links and also work together towards designing and implementing common policies to boost sports development. Common sense and good intentions are not enough as the many current uncoordinated policies have not helped to achieve better results in terms of increased participation or increased elite success. Official financial support is more than evident, but it is necessary for the state-owned entities to exert more effective control and supervision of the funds provided and to provide unified strategic leadership through the MPPD.

Notes

1. Simón Bolívar, born in Venezuela, is considered Venezuela's national hero and the father of independence of six Latin American nations.

2. In September 2011 the new National Sport Law was approved. But the regulations and special laws derived from it are still under discussion.

References

- Castillo , F. 2004 . Instituciones deportivas , Caracas : Italgráfica .

- Constitución de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela . 1999 . Gaceta Oficial de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela, 5.453 (Extraordinario), 24 Marzo 2000

- Flamerich , G. 2005 . Diversiones en 4 siglos en Venezuela 1500–1900 , Caracas : Miguel Ángel García .

- Galeano , E. 1995 . Las venas abiertas de América Latina , 64th , Bogotá : Tercer Mundo Editores .

- García , P. and Rodríguez , A. 2002 . Aspectos Socio-antropológico del deporte. Historia y tendencias actuales , Caracas : Ediciones del Instituto Nacional de Deportes .

- Ley del Deporte . 1995 . Gaceta Oficial de la República de Venezuela 4.937, 14 July

- Ley Orgánica de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación . 2006 . Gaceta Oficial de la República de Venezuela 38.081, 7 December (originally versión approved in 2004)

- Ley Orgánica de Educación . 1980 . Gaceta Oficial de la República de Venezuela 2.635 (Extraordinario), 28 July

- Ley Orgánica de Educación . 2009 . Gaceta Oficial de la República de Venezuela 2.635 (Extraordinario), 19 August

- Ley Orgánica del Trabajo . 1997 . Gaceta Oficial de la República de Venezuela 5152 (Extraordinario), 19 June

- Ley Orgánica para la protección del niño y del adolescente . 1998 . Gaceta Oficial de la República de Venezuela 5.266, 2 October

- Ley para las Personas con Discapacidad . 2007 . Gaceta Oficial de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela 38.598, 5 January

- López de D'Amico , R. 2006 . “ Organization of sport in Venezuela ” . In Contemporary sport management , Edited by: Parks , J. , Quaterman , J. and Thibault , L. 330 – 331 . Champaign , IL : Human Kinetics .

- López de D'Amico, R., 2008. Career development in physical education and sport in Venezuela. Bulletin of the International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education (ICSSPE) [online], 52. http://www.icsspe.org/members/bulletin/druckenbulletin.php?ver=texte&nr=No.52 (http://www.icsspe.org/members/bulletin/druckenbulletin.php?ver=texte&nr=No.52) (Accessed: 1 December 2010 ).

- López de D'Amico , R. 2009a . Gerencia deportiva como área académica y su aplicabilidad: actas científicas , Maracay : Serie EDUFISADRED .

- López de D'Amico , R. 2009b . “ Reflexiones varias acerca del deporte en Venezuela ” . In Comp. Deporte, política y sociedad , Edited by: ópez , R. L . 53 – 58 . Maracay : Ediciones IRDA .

- López de D'Amico , R. 2010 . Informe de gestión 2010 , Maracay : IRDA .

- López de D'Amico , R. and Ramírez , E. 2008 . “ El movimiento olímpico en Venezuela ” . In Los juegos olímpicos explicados. Una guía de estudio a la evolución de los juegos olímpicos modernos , Edited by: Girginov , V. , Parry , J. and ópez de D'Amico , R. L . 87 – 104 . Caracas : Comité Olímpico Venezolano .

- Ramírez , J. 2009 . Fundamentos teóricos de la recreación, la educación física y el deporte , Caracas : Episteme .

- Segovia , P. 1985 . Historia del deporte en Venezuela , Caracas : Su Organización. s/e .

- Terán , J. 2010 . Sistema Bolivariano de actividad física, deporte y recreación: hacia la consolidación de las políticas de democratización, universalización y masificación , Maracay , , Venezuela : Paper presented at the II congreso of the Latin American Association for Sociocultural Studies in sport, 16 September 2010 .

- UPEL . 1990 . Educación física, deporte y recreación – volumen II , Caracas : Universidad Pedagógica Experimental Libertador .