Abstract

Sport policy is a primary organ that nations utilise in their attempt to meet national development goals; it provides guidelines and operational principles that governments and sport organisations can use in sports governance. The purpose of this paper was to examine the extent to which the general and political trends were reflected in sports policy in Kenya, with specific focus on (1) sport and public policy; (2) sport professionalisation; and (3) the quest for new sport policy. The sport and public policy section focuses on the evolution of sports from pre-colonial period to early 1990s, while sport professionalisation discusses the emergence of commercialisation of athletics. The internalisation of sports evokes a new paradigm in sports governance that required Kenya government to formulate new sport policy, which culminated in the enactment of the Sport Act of 2013. Implications for this study rest on the articulation of colonial and post-colonial conditions, which have informed contemporary sport landscape, the development of sport policy that govern sports federations from local to national levels, and on the systematic ways sport entities will function in Kenya.

Introduction

The East African nation of Kenya straddles the equator and is located about 5° N and 4° S in latitude and about 38° E and 41° W in longitude (Kareri Citation2013). The size of the country is comparable to the US state of Texas, with a total land area of 582,000 sq. km, including 13,600 sq. km of inland lakes (Arodho Citation2013, Kareri Citation2013). Kenya is bordered to the north by Sudan and Ethiopia, northeast by Somalia, east by the Indian Ocean, south by Tanzania and west by Uganda. The country is geographically diverse, with lowland coastal region, snow-capped mountains, endless savanna region, semi-arid eastern region, and has a large fresh waterbody, Lake Victoria. This particular diversity comes in form desert and alpine snowy areas, mountainous regions, vast acacia woodlands, open plains, many freshwater lakes and several beaches that are found along the Indian Ocean (Amin and Eames Citation1990). The highest point is Mount Kenya, which at 5199 m is the second highest peak in Africa (UNESCO Citation2014).

A spectacular geographic feature in Kenya is the Great Rift Valley. It starts from the Dead Sea in Jordan, Middle East, and goes through the Red Sea, and enters the Afar Triangle in Ethiopia, entering Kenya through Turkana, the northern part of the country, to divide the country into almost two equal parts (Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia Citation2014). The Great Rift Valley is a repository of human evolution, dating back 8 million years making Kenya home to the human race, and in addition, the Rift has plenty of diversity in plant and animal life (Johns and Hemingway Citation1991). The varying geography of Kenya provides for an extremely wide variety of wildlife, with the Big Five – lion, elephant, buffalo, leopard and rhino – attracting millions of visitors each year.

Kenya is a diverse multiracial, multiethnic and multilingual East African nation. The country’s inhabitants are of many origins – African, Arab, Asian and European – and the African population comprises 42 ethnic groups belonging to three major linguistic groups, namely Bantu, Cushitic and Nilotic speaking people. Kenya’s population is 45 million, with the majority being of Bantu origin. The Nilotic and Cushitic speakers number about 11% and 3 % of the Kenya’s people, respectively (Sayer Citation1998). While the primary language of business and education in the country is English, Kiswahili is considered a lingua franca in most areas of commerce and social spheres, particularly in urban areas. For purposes of administration, Kenya is divided into eight provinces, namely Central, Coast, Eastern, Nairobi, North Eastern, Nyanza, Rift Valley and Western. Each province is further divided into districts.

In context of history, the early visitors to come to Kenya were the Arabs, who arrived around the eighth century, and they controlled most of the coastal region of the country (Coleman Citation2013). In 1498 Portuguese explorers became the first European visitors to set foot in Kenya, with the British taking over in 1895. The country became a British East African Protectorate, and it became a colony of Britain in 1920 (Jackson Citation2011, Coleman Citation2013). Kenya received her independence from Britain in 1963, emerging as a new nation, with Jomo Kenyatta serving as its first President. Kenya became a republic in 1964 and Kenyatta’s rule ended when he died in 1978. Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi took over as second President of Kenya, with his rule ending in 2002 when President Mwai Kibaki took over as the third president of the Republic of Kenya. Kenyatta’s son, Uhuru Kenyatta, took over as the fourth president of Kenya in March of 2013.

The social political landscape of the country from the pre-colonial era to post-independence period shaped sports development and administration in schools and society. Before the coming of Europeans, people of African descent in Kenya practised informal education that imparted cultural knowledge and customs to the young and old. There were African forms of education, which were adept at fulfilling the needs of the population that included ways to teach the young to be productive members of society (Sifuna Citation1990). The purpose of this paper is to examine the extent to which the general social and political trends in colonial and post-colonial Kenya were reflected in sport policy, with the specific areas of investigation centring on the following: (1) sport and public policy in colonial and post-independence periods, (2) sport liberalisation and professionalisation, and (3) the quest for sport policy in enactment of Sport Act. The paper concludes with a discussion of implications for the future development of sport.

Sport and public policy in colonial Kenya

In the pre-colonial period, Kenyan Africans had their own indigenous sport activities that were part and parcel of people’s livelihoods and served as part of the fabric of society. Sports and play were critical components of the African way of life because through them children learned to imitate the actions of elders and assimilate ideas that informed their identity formation (Sifuna Citation1990, Amusa & Toriola Citation2012). In addition, these physical activities promoted the development of cultural identity, enhanced children and youth’s acquisition of cognitive, social and physical skills critical to adult existence (Chepyator-Thomson Citation1990). The stratification of sports based on age, gender and functions represented the transfer of strategic skills as an embodiment of a cultural reservoir and adequate preparation for adult life (Zaslavsky Citation1973, Chepyator-Thomson Citation1990). Indeed, games and sport activities ‘served as an instrument of socialisation, cultural preservation, and as recorders of changes occurring in societies’ (Chepyator-Thomson Citation2012, p. 380). Most sports were practised at individual level, and in other cases, team sports were emphasised to enhance group dynamics. For example, wrestling among boys was an expression of stamina and physical coordination. In some communities, the game of shooting at predefined targets developed the skills necessary for hunting and community defence (Chepyator-Thomson and Byron Citation2012). Most often the youth’s involvement in games allowed them to acquire physical and mental skills essential to formal functioning in society. Thus, the youth, through games and sports participation, gained practical knowledge and tools for team playing and cooperation that shaped their overall purposefulness in their communities (Sifuna Citation1990). Children were prompted to engage, innovate and invent new forms of play and games, which emphasised principles of social responsibility, social discourse and inculcation of spiritual and moral values (Sifuna Citation1990, Amusa & Toriola Citation2012). Methods of instruction varied but included learning activities through play forms (Sifuna Citation1990) and also through sports participation and dance activities. However, everything changed with the advent of colonialism. Wherever the Britons went they took with them their sports activities. This was the case in Kenya where imported sport activities were a carbon copy of what was occurring in Britain (Guttman Citation1994). British sports in Kenya were purposely taught to maintain discipline and order in the community, which disengaged indigenous clan systems from maintaining order in society (Mählmann Citation1992).

Sport, education and culture

Mission schools were the avenues through which British sports were introduced to Kenyan society, and many people of African descent learned these sports in boarding schools (Chepyator-Thomson and M’mbaha Citation2013). Sport became an instrument for moral training and was seen as inculcating the spirit of fair play in competitive sports (Ndee Citation2010, Chepyator-Thomson and M’mbaha Citation2013). The British colonists introduced upper social class sports from their mother country, which ‘served as integrative factor for the colonialists’ (Mählmann Citation1992, p. 125). Britons became entrenched in their colony, Kenya, with sports becoming an anchor of their lives. Communities, large and small, had their own centres of sport and facilities which enabled the colonists to take part in a variety of sport activities that included golf, swimming, rugby, field hockey, tennis and squash (Guttman Citation1994). The primary objective of the sporting culture was to dominate the social discourse of the society, where the Africans were made to feel inferior in all aspects of life and they were not equal participants in sport competition (Mählmann Citation1992).

Why did sports occupy central position in the lives of the British people in the colonies? During the colonial period, Britain promoted exclusive and prestigious sports such as Lawn Tennis, Polo and Cricket, usually upper class sports, in the colonies. These sports were less costly to organise in the colonies than in their home country (Ndee Citation2010). Football and athletics were thought to be the sports fit for ‘natives’ and were encouraged for their authoritarian value. Sport in the formal education system was used chiefly as a means to achieve order and to discipline the youth, particularly African male (Mangan Citation1987). African players’ engagement in British sports helped them to internalise norms of superiority and inculcated values that impacted their identity formation (Mählmann Citation1988). To spur sport participation among the Kenyan people, sport associations were formed to govern the popular sports of the time such as the Cricket Association, the Kenya Amateur Athletics Association, the Kenya Olympic Association and the Kenya Football Federation. Some of these associations followed racial segregation during the colonial era while others promoted multiracial participation in sports participation and in the administrative aspects of the sports. School sports were promoted following the models of national sports association although entirely organised via the Ministry of Education. The history of these associations governing sports in Kenya today is provided in . The relationship between the colonial sports and school sport in shows the level of development that took place in colonial times and also during contemporary time of schools sports. Cricket was the first sport to be introduced to the colony although it was exclusively Europeans who took in this sport.

Table 1. The chronology of the development of selected sports organisations in Kenya.

Sports association became increasingly visible in the 1950s which was during the period of political agitation for independence. British sport policy served as a tool for social control and as a way to exercise cultural power, allowing for domination and appeasement of the indigenous populations (Stoddart Citation1988). Accordingly, sports organisations served a political purpose, and they became necessary during this time as elements of the colonial government and cultural missionaries. This was because sport was used as a form of social control, stopping Africans from engaging in potentially disruptive actions such as involvement in political agitation against the colonial government (Chepyator-Thomson Citation2012).

The internationalisation of Kenyan athletics began with the establishment of the Kenya Amateur Athletics Association in 1951. Athletes took part in the first Indian Ocean Games in 1952 in Madagascar and subsequent Commonwealth Games in 1954, in Vancouver, Canada. At the time Kenya was still a colony of Britain. The athletes’ involvement in sports was meant to divert attention from agitation for African independence (Tanser Citation2008). The formation of the Kenya Olympic Association in 1954 was another way that the colonial government used sports as a form of international legitimacy of colonialism at a time of resistance against foreign rule and as a way to defuse the internal tensions during the state of emergency. The policy of African exclusion in some sports – golf, cricket and rugby – indicated the depth of racial discrimination or segregation in Kenya. It also revealed the use of sport as class system, where the schooling of the youth and the organisation of schools followed their parents’ social status. British sports were promoted in educational institutions and were stratified by race and social class (Gikandi Citation1996). Higher social status sports such as tennis, swimming, cricket, squash and golf were taught in expensive upper-class schools, which were mainly for Europeans although some of these sports were offered in Asian schools (Chepyator-Thomson Citation1993). The African schools received limited funding and meagre resources which excluded elite sports programmes from their curriculum. With the country’s independence in 1963, the new African government changed British social policies to meet the new realities of the emerging nation. In the next section, the paper looks at the role of sports in the development of national unity and promotion of African socialism.

Sport and policy in post-independence Kenya

The first President of the Republic of Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta, took measures to promote economic development and social progress following independence (Sessional Paper, No.10 Citation1965). Kenyatta’s government vowed to develop the new nation using ideas and philosophy that subscribed to African socialism. This principle, in effect, resulted in government control of the decision-making process intended to ensure a balanced and rapid growth in social and economic development of the country. In the area of sport, responsibility rested within the Ministries of Education and Culture and Social Services, with the Ministry of Education being held responsible for school sports programmes while the Culture and Social Services counterpart took control of out-of-school sports participation. Essentially, the government became the catalyst for sports administration and sport for development in Kenya. The out-of-school sports activities were run on a voluntary basis, and the government coordinated sports development and administration through the Kenya National Sports Council (KNSC) (Godia Citation1989).

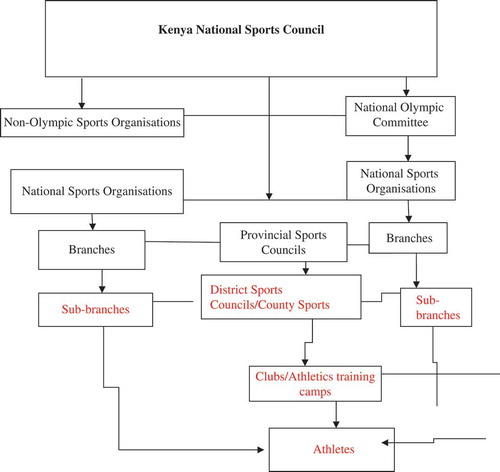

KNSC is the governing body of sports and was formed in 1966 under the Society’s Act (cap 108) of the Laws of Kenya. The Council served as an umbrella body whose function was to coordinate and harmonise sports organisations’ activities in the country and to serve as the organ of coordination between sports organisation and the government (Ministry of Gender, Sport, Culture and Social Services Handbook Citation2005). In specific terms, the KNSC serves as the technical arm of the government and is responsible to the ministry of Youth Affairs and for Sports channelling funds to the sports federations (Godia Citation1989). Sport programmes in Kenya are managed by two line ministries. Youth sports are organised as co-curricular under the Ministry of Education with different sport activities organised from the school level to national competitions during different school terms. On the other hand, out-of-school sports are organised by national sports organisations under the directive of the Ministry of Sport Culture and Arts. Since independence, the ministry responsible for sports has changed names from Culture and Social Services through to the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sport. When it comes to funding, the sports federations submit their budget ‘estimates and calendar of events for every financial year to enable the council to prepare budget in advance so as to avoid a last minute rush and financial complications’ (Godia Citation1989, p. 271). The organisation structure () shows how the government sports programmes are implemented and managed from the national sports federations to the grassroots levels. Sports organisations are separated into Olympic sports and non-Olympic sports, with respective structures located at the provincial and county levels. The government provide funding for Olympic sports through the National Olympic Committee (NOC) of Kenya. The NOC organise preparation and selection of Olympic athletes in liaison with the respective sport federations. These federations solely depend on government financial allocation to run their affairs. Some federations, for example Athletics Kenya (AK) and Kenya Football Federation (KFF), receive funding from NIKE and FIFA Goal Project, respectively. AK benefits from NIKE sponsorship amounting to US$1.6 million annually while KFF received US$400,000 for the establishment of sport facility at Kasarani, Nairobi, from FIFA. The relationship between government and KFF has resulted in a conflict of interest with FIFA rules which indicate that governments should not interfere with the affairs between the football federations. These tense relations of government and KFF have over the years been subject to arbitration at the Court of Arbitration of Sports over the accusation of government interference.

Figure 1. KNSC organisational structure.

Since 1989, KNSC has refined its objectives with respect to the political and institutional changes, but with the same original intentions of the government at the time of its formation. Broadly, KNSC has additional objectives of ‘facilitating local and international participation in all sports by affiliates, solicit for financial, technical and material support for the affiliates both locally and internationally’ (Ministry of Gender, Sport, Culture and Social Services Handbook Citation2005, p. 29). The relationship between the KNSC and the sport organisations starts from the national level to the grassroots or the local levels. The Council oversees the development of sports organisation through the national sport organisations and the provincial sports councils. At the national level, the KNSC supervises the sports organisations through the broad division of Olympic and non-Olympic sports. Although this difference is evident in the KNSC organisation structure, this divide is not clear with respect to sports participation at the grassroots. The development sport within the schools’ system hardly mentions this difference of Olympic and non-Olympic sports, neither is this difference evident in out-of-school sports.

The provincial sports council coordinates sports activities in conjunction with the KNSC head office. At the provincial level, there is a department of sports under the provincial director of sport in each of Kenya’s eight provinces. Each provincial director of sport is responsible for the administration of several districts under its jurisdiction. The other approach, the KNSC coordinates sporting activities, is through the sports organisations, otherwise known as federations or associations. The words, ‘organisations, federations, and associations’ mean the same thing and are used interchangeably in the context of sports in Kenya (Sport Act 2013). The Ministry of Education organises sports activities in educational institutions ranging from primary schools and secondary schools to college sports programmes. The identification and development of elite athletes for global competitions such as the Olympic and Commonwealth Games in Kenya begins in educational institutions. Many of Kenya’s successful athletes are identified in school competitions. Today, schools are the most important institutions that promote sports development in Kenya. The success of school sports programmes indicates systematic integration of education and sports starting at the outset of independence. Schools also play an important function in teaching social values and promoting student learning and discipline (Bale and Sang Citation1996). Each sport federation is responsible for athletics development and their exposure to competition at the national and international levels, with coordination provided by the NOC and financial support allocated from the government.

The Kenya sportspersons’ performances at the Vancouver Empire Games in 1954 began a new era of sport development both in quality and diversity in athletics. The beginning of the 1960s saw significant sport performances at the 1962 and 1966 editions of the Commonwealth Games. These athletic achievements gave the nation international stature and prestige. But it was the spectacular athletic performances produced at the 1968 Mexico Olympic Games that put Kenya at the global pinnacle in distance running (Wilber and Pitsiladis Citation2012). As Bale and Sang (Citation1996) explain, Kenyans became an international force, giving Kenya a much higher level of visibility in the global sports arena than ever before. Athletics became the national symbol of international diplomacy and public relations within the African region and global arena. Following the dramatic sports performances at Mexico Olympic Games, organisations started to institutionalise their sports programmes and organise them around different areas of specialisation (Mählmann Citation1992). The new nation of Kenya used sports not only as a way to decolonise the country but also as a platform for dialogue with its colonial past. The country also used the colonial sports institutions retained at independence to undo the colonial mentality and social conditions that the British imposed during colonialism, with the aim to empower the newly independent nation (Gikandi Citation1996). Thus, international sport became an instrument of international politics and diplomacy (Sage Citation1998). For most independent African countries, the Olympic Games provided an international solidarity platform reflecting the liberation of African nations. In 1976, Kenya and other African countries boycotted the 1976 Montreal Olympics in protest against New Zealand’s continued sporting contact with South Africa which maintained the policy of apartheid. The National Party government of New Zealand endorsed sporting ties with apartheid South Africa, which was strongly opposed by many African countries (Ndee Citation2010). The politics of boycotting the Olympic Games emerged once again in 1980 following Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. Kenya found herself involved once again as part of the US-led Moscow Olympics boycott. The two Olympic boycotts were a huge blow to the development of athletics and the sport of boxing in Kenya which were the country’s two most significant Olympic sports.

Sports development and professionalisation

International non-governmental sports organisations, such as the International Association of Athletic Federations and the IOC, control sport participation at the global–local level, working in tandem with sports organisations are located within each country. Most of these major international sports organisations are run on the lines of global corporations and are rarely located outside Europe and North America. Yet countries like Brazil, Kenya and many others in South America and Africa have produced stellar football players and track and field athletes that contribute significantly to the spectacles of human contest at the global level. Kenya cricketers surprised the world when they emerged as semi-finalists at the World Cup Finals in 2003, beating Test playing nations of Asia (Sri Lanka and Bangladesh) and Africa (Zimbabwe) (Redfern Citation2003). With this stellar performance, the International Cricket Council gave 1 million US dollars to the Kenya Cricket Council to develop the game in the country, focusing specifically on improving performance, the financial foundation, governance and administration of the game (Redfern Citation2003).

In Kenya, prominent international sport organisations, for example, FIFA, IAAF and IOC, are considered symbols of modernisation at the cultural, political and economic spheres, in which Kenya, among other nations, vies for global corporate sport finance. The Kenya Government’s encounter with international organisations in the arena of sport came in form of foreign aid in 1970s and 1980s. This foreign assistance came from the former colonial power and from other development partners. While Britain continued her relationship with her former colony through the promotion of athletics by sending coaches to Kenya who conducted coaching clinics and produced coaching manuals (Bale and Sang Citation1996), the Federal Republic of Germany, through ‘Sport and Development Aid’ (Mählmann Citation1989, p. 119; see also Bale and Sang Citation1996, p. 113), extended huge financial support for the development of athletics in Kenya. This aid was fundamental to the transformation of coaching programmes, which came under both the ministerial section of the government and the Kenya Amateur Athletic Association (KAAA), the precursor of AK. The GTZ, a German development agency, was responsible for providing coaches and advisers to Kenya to assist in the long-term development of sport programmes and policies. Walter Abmayr became the director and was an athletic tactician, who established the Kenya Athletic Coaches Association, and expanded the Kenyanisation of the coaching pool in training 260 athletic coaches and athletic managers between 1981 and 1985 (Mählmann Citation1989). These coaches were instrumental as agents of sport for development and for promoting the sport of track and field across the country.

The other development partner has been the Chinese government, which funded the creation of a new sport infrastructure in the country in mid-1980s. The Chinese bilateral assistance played an important role in the development of Kenya’s sports infrastructure that led to the construction of Moi International Sports Center, in Kasarani, Nairobi, from 1983 to 1987 in preparation for the fourth All African Games held in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1987. This multisport complex became the signature sport landmark for Kenya’s second President, Daniel Arap Moi (1978–2002), which stands as a legacy in the modernisation of sports facilities and international formation of sports partnerships. The sport policy objective of the Kenya government in the 1980s was to embark on aggressive athletic development to restore her image in international competition after the two consecutive Olympic boycotts and dismal performances in the Commonwealth Games. The foreign aid channelled to elite sport development (Mählmann Citation1992, Bale and Sang Citation1996) in 1980s saw the successful implementation of sport programmes that enabled the country to regain international status in 1988 Seoul Olympics, where it won nine medals of which five were gold compared to the three gold medals won in 1968.

The social policy at the time advocated that sports served as a means to solve unemployment, which resulted in many government parastatals recruiting sportsmen and sportswomen to enhance their corporate image. The growth in parastatals involvement was the eventual professionalisation of most sports in Kenya. The increasing need for capital generation through sport led to globalisation and professionalisation of the sport industry, with sports agents in track and road racing in particular coming to Kenya in search of skilled athletes. The athlete became the athletic product packaged for the consumer by the corporate world for the sole purpose of consumerism and profiteering in the capitalist market place. Bale and Sang (Citation1996) aptly explains that the ‘athletes' agents or managers are themselves international agencies who are able to create global festivals of a scale previously unknown outside the Olympics, these are exemplified by Grand prix events’ (p. 107). Commercialisation of athletic pursuits has opened up Kenyan sport space to internationalisation and globalisation. The grand prix in particular has become a common feature of sport consumption and participation. The rapid internationalisation and corporatisation of sport has challenged the ability of many governments, including Kenya, to retain control over the development of elite sport at the domestic level.

The quest for new sport policy

Sport policy is an area that has experienced considerable agenda development in recent years, especially among the Commonwealth member states, where sports are integral to government intervention (Parrish Citation2003). The process of policymaking is dynamic (Houlihan Citation2005), interpretative and undergoes rigorous debates where arguments and counterarguments are parleyed by protagonists and antagonists with equal passion in the policy-making process (Sam Citation2003). In Kenya, Sessional Paper No. 3 of 2005 on Sports Development presented a framework on sustainable growth and development of sports in the country. It also provided policy guidelines on growth and development of sports through a holistic approach, where the process is expected to generate mutually beneficial operational principles for governing sports. The government plan focused on mainstreaming sports in all areas of development (Ministry of Gender, Sport, Culture and Social Services Handbook Citation2005), making sports organisations, or the recipients of government and corporate funding, play an important role in the implementation of public policy. However, the constant shifting of government priorities from health to youth unemployment programmes has resulted in the constant realignment of sport policy communities to be in line with government policy priorities and funding. However, the formulation of stable sport policy became an elusive political exercise, with perpetual postponement since 1990. In 2010, the Kenya cabinet discussed the first draft of the sport policy Bill which was eventually brought to Parliament in October 2012. The Minister for Youth Affairs and Sports brought the Bill to Parliament, the Sport Bill, No. 43 of 2012, for debate. The Minister argued with the stakeholders of sport indicating that they should be very ‘clear about the enactment of a Bill – it gives a broad legal framework to manage, regulate and provide guidance on how to conduct and administer sporting affairs in this country…’ (Kenya National Assembly Report, Hansard, 10, 10 Citation2012, p. 53), and added that in the context of history, and for future reference, the Bill provides a critical avenue to manage and operate sport with a legal framework (Kenya National Assembly Report, Hansard, 10, 10 Citation2012).

The Minister also explained the purpose of the Bill in reference to sport governance and also revealed the institutional oversight bodies that are relevant to the division of labour in the Ministry of Sports. The Minister elaborated that the aim of the Bill was to establish institutions that would manage the country’s sports affairs within a legal framework, serving equally the needs of men and women, take account of the various views of the stakeholders and provide diverse ways that sports could be managed in the country. The institutions in question include the Kenya Sports Development Authority (KSDA) whose main function is to promote, co-ordinate and implement grassroots, national and international sports programmes for Kenyans, in liaison with the relevant sports organisations and facilitate the active participation of Kenyans in regional, continental and international sports, including in sports administration. The National Sports Fund is a body corporate with the explicit role of managing all the proceeds of any sports lottery, and investments from sport facilities. The government budget allocated to the Ministry of Sport Culture and Arts during financial year 2014–2015 amounts to Kshs. 3.87 billion with sports getting Kshs. 1.3 billion (Government of Kenya Citation2014). Most of these monies go to the development of infrastructural facilities and facilitating athletes to participate in international competitions. National sports associations are required to prepare their annual budgets, and the KNSC assists the ministry in determination of the allocation based on the contribution of the sport to national performances in international competition and community engagement. The other organ is the Kenya National Sports Institute (KNSI). The Institute’s objective was to establish and manage sports training academies in the country to enhance greater sports talent development in all most sports in the country. The other institution is Registrar of Sports Organizations (RSO) whose responsibility is the registration and regulation of sports organisations and licensing and the Sports Disputes Tribunal (SDP) whose performance concerns the function of arbitration of sports disputes among sports organisations. The Sport Bill No. 43 of 2012 was passed on 9 January 2013 as law, Sport Act No. 25 of 2013, the first legal framework to guide the development of sport policy in Kenya, which happened after a protracted and contentious debate in Parliament.

Conclusions

The role of sport in society is fundamental to the realisation of a healthy and prosperous nation. Sport, as an element of consumption and production, has the potential to engender economic benefits for participants and wider society, which at times is beyond the podium and the recognition of championship medals. However, the majority of excellent sports women and men remain underutilised or misidentified due to the inadequacies of the current talent identification and development processes. In Kenya, sports have political undertones, with politicians shaping the sports fields either through the regulatory framework of institutions such as Parliament or through sports organisations under the patronage of civil servants.

Parliament approves the budgetary allocations to sports activities with little input from the sports stakeholders. Most of these monetary allocations are inadequate, mismanaged or mismatched with the priorities (Kenya National Assembly Report, Hansard, 10(10) Citation2012). An audit of the functional relationship between the per capita sports allocation and the expected output from the sports sector indicates a misconception of the purpose of sport financing (Report of Auditor-General, Kenya Citation2011/2012). While the government has enormous interest in sport for development, the actualisation of the intentions of government sport policy as an avenue to promote access to gainful benefits and to improve the lifestyle and conditions of most of the talented Kenyan youthful population remains limited (Ministry of Gender, Sport, Culture and Social Services Handbook Citation2005).

As an engine of a healthy nation, sports at the competitive and recreational levels provide the impetus to achieve a vibrant workforce, versatile sportspeople, a creative society and a competitive nation (Nowak Citation2012). In addition, sports promote international diplomacy and prestige with excellent athletic performance at international competitions, which further contributes to branding of the nation as a tourist destination. Through sports marketing, Kenya’s international visibility will be enhanced, thus attracting foreign investors and consumers of Kenyan products, especially sports tourism (Ministry of East African Affairs, Commerce and Tourism Citation2013).

Athletics has become the pride of Kenya in international championships especially at the Olympic Games and major city marathons. Kenyan athletes have shaped the dynamics of contemporary elite running in the world (Tanser Citation2008). The mechanics of distance running, the politics of training and competitions are referenced in Kenyan performances and training habitus, and talk about Kenyan running phenomenon has become the norm in global athletics circles.

In summary, Kenya’s rise to prominence above the current sports levels of participation depends on how the sport policy is articulated in sporting environments. It is too early to assess the effectiveness of the 2013 Sport Act in the management of sports in Kenya. Its implementation will gradually be seen as it is factored into national and county sports organisations. The achievement now lies, thus far, in its legislative success that took, at least, half a century to be realised. Meanwhile, the government, sports organisations, and sport policy consumers have the time to deconstruct the functionality of the sport policy implementation process. On the whole, sports management in Kenya is positioning itself for a more rigorous and vibrant environment if and only if the sport policy implementation framework is successfully realised with the necessary political goodwill.

Disclosure statement

There was no conflict of interest and no financial rewards to the authors.

References

- Amin, M. and Eames, J., 1990. Insight guides: Kenya. Singapore: APA Publications.

- Amusa, L.O. and Toriola, A.L., 2012. Professionalization of physical education and sport science in Africa. African journal for physical, health education, recreation and dance, 18 (3), 628–642.

- Arodho, A.P., 2013. Country pasture/forage resource profiles [online]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/ag/AGP/AGPC/doc/counprof/kenya.htm#10 [Accessed 5 October 2013].

- Bale, J. and Sang, J., 1996. Kenyan running: movement culture, geography and global sport. Portland, OR: Frank Cass.

- Chepyator-Thomson, J.R., 1990. Traditional games of Keiyo children: a comparison of pre- and post-independent periods in Kenya. Interchange, 21 (2), 15–25. doi:10.1007/BF01807621

- Chepyator-Thomson, J.R., 1993. Kenya: culture, history, and formal education as determinants in the personal and social development of Kalenjin women in modern sports, Social development issues, 15 (3), 30–44.

- Chepyator-Thomson, J.R., 2012. Sports: 1900 to present: Africa. In: A. Stanton, E. Ramsamy, P. Seybolt, et al., eds. Cultural sociology of the Middle East, Asia, & Africa: an encyclopedia. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, II380–II382. doi:10.4135/9781452218458.n416

- Chepyator-Thomson, J.R. and Byron, K.C., 2012. Continental complexities: a multidisciplinary introduction to Africa. In: I. Simon and A. Ojo, eds. Indigenous, colonial, and postcolonial perspectives on African sports and games. San Diego, CA: Cognella, 229–242.

- Chepyator-Thomson, J.R. and M’mbaha, J., 2013. Education, physical education, and after-school sports programs in Kenya. In: J.R. Chepyator and S. Hsu, eds. Global perspectives on physical education and after-school sport programs. New York: University Press of America, 37–56.

- Coleman, D.Y., 2013. Kenya. Kenya country review [online], 1–2. Available from: http://www.countrywatch.com [Accessed March 2014].

- Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 2014. Kenya [online]. Available from: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/315078/Kenya [Accessed 2 November 2014].

- Gikandi, S., 1996. Maps of Englishness. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Godia, G., 1989. Sports in Kenya. In: E.A. Wagner, ed. Sport in Asia and Africa: a comparative handbook. New York: Greenwood Press, 267–281.

- Government of Kenya, 1965. African socialism and its application to planning in Kenya. Sessional Paper No. 10 of 1965. Nairobi: Government Printer.

- Government of Kenya, 2014. Programme based budget 2014-2015 [online]. Available from: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=4&ved=0CC8QFjAD&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.cofek.co.ke%2FPBB%25202014-2015%2520Complete.pdf&ei=2Z86VKWxEo_JgwTnqIKgAQ&usg=AFQjCNHhvaGyKC6eEl3guEa9JAA4oPZmNQ&sig2=OlrLkBWxj1GVAa6PaQpwYQ&bvm=bv.77161500,d.eXY [Accessed 25 August 2014].

- Guttman, A., 1994. Games and empires. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Houlihan, B., 2005. Public sector sport policy: developing a framework for analysis. International review for the sociology of sport, 40 (2), 163–185. doi:10.1177/1012690205057193

- Jackson, W., 2011. The white man’s country: Kenya Colony and the making of a myth. Journal of Eastern African studies, 5 (2), 344–368. doi:10.1080/17531055.2011.571393

- Johns, C. and Hemingway, P., 1991. Valley of life. Africa’s great rift. Charlottesville, VA: Thomson-Grant.

- Kareri, R.W., 2013. Some aspects of the geography of Kenya [online]. Available from: http://international.iupui.edu/kenya/resources/Geography-of-Kenya.pdf [Accessed 5 October 2013].

- Kenya Football Federation, 2014. Football in Kenya FIFA goal programme [online]. Available from: http://www.fifa.com/associations/association=ken/goalprogramme/newsid=521488.html [Accessed 10 December 2014].

- Kenya National Assembly Report, Hansard, 10, 10, 2012. Available from: http://www.parliament.go.ke/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=243&Itemid=206 [Accessed 15 October 2012].

- King, N., 2009. Sport policy and governance: local perspectives. Burlington, MA: Elsevier.

- Mählmann, P., 1988. Sport as a weapon of colonialism in Kenya: a review of the literature. Trans African journal of history, 17, 172–185.

- Mählmann, P., 1989. Perception of sport in Kenya. Journal of eastern African research & development, 19, 119–145.

- Mählmann, P., 1992. The role of sport in the process of modernization: the case of Kenya. Journal of Eastern African research and development, 22, 120–131.

- Mangan, J.A., 1987. Ethics and ethnocentricity: imperial education in British tropical Africa. In: W.J. Baker & J.A. Mangan, eds. Sport in Africa: essays in social history. New York: Africana Publishing Company, 138–171.

- Ministry of East African Affairs, Commerce and Tourism, 2013. Strategic plan 2013-2017. Nairobi: Government Printer.

- Ministry of Gender, Sport, Culture and Social Services Handbook, 2005. Sessional paper no. 3 of 2005 on sports development. Nairobi: NBO: Government of Kenya, i–35.

- Ndee, H., 2010. Modern sport in independent Tanzania: agents and agencies of cultural diffusion and the use of adapted sport in the process of modernization. The international journal of the history of sport, 27 (5), 937–959. doi:10.1080/09523361003625915

- Nowak, P.F., 2012. Mass sports and recreation events as effective instruments of health-oriented education. Journal of physical education & health, 2 (3), 31–37.

- Parrish, R., 2003. Sport law and policy in the European Union. Manchester University Press.

- Redfern, P., 2003. Kenya’s cricketing future. Africa business, 287, 46–48.

- Report of Auditor-General Kenya, 2011/2012. Appropriations accounts of the republic of Kenya for the year 2011/2012 [online]. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=Report+of+Auditor_general+2011%2F2012+Kenya&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8 [Accessed 15 March 2014].

- Sage, G. H., 1998. Power and ideology in American sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Sam, P.M., 2003. What’s the big idea? Reading the rhetoric of a national sport policy process. Sociology of sport journal, 20, 189·213.

- Sayer, G., 1998. Kenya. Promised land? Oxford: Oxfam Publishing.

- Sifuna, D.N., 1990. Development of education in Africa: the Kenyan experience. Nairobi: Initiatives.

- Stoddart, B., 1988. Sport, cultural imperialism, and colonial response in the British Empire. Comparative studies in society and history, 30 (4), 649–673. doi:10.1017/S0010417500015474

- Tanser, T., 2008. More fire: how to run the Kenyan way. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, LLC.

- UNESCO, 2014. Mount Kenya National Park/Natural Forest. Available from: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/800 [Accessed 5 March 2014].

- Wilber, R.L. and Pitsiladis, Y.P., 2012. Kenyan and Ethiopian distance runners: what makes them so good? International journal of sports physiology and performance, 7, 92–102.

- Zaslavsky, C., 1973. Africa counts: number and pattern in African culture. Boston, MA: Prindle, Weber & Schmidt, 02116.