ABSTRACT

This article explores the relationships between sport, space and state in the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. While the extant literature has predominantly attributed the Russian government’s motives behind hosting the Olympics to showcasing Putin’s Russia, this article provides a more nuanced account of the Sochi project in light of its entanglements with regional development and its implications for Russia’s spatial governance. It argues that Sochi has been an important experimental space for the federal state in its reconstitution and re-territorialisation of the institutions of economic development. The Sochi project signposts a dual process: the return of regional policy to the state’s priorities and a (selective) return of the federal state to urban development. Whilst not without controversies and inconsistencies, this practice signifies a re-establishment of strategies seeking a more polycentric economic development, including through supporting places on Russia’s less developed peripheries. The article also presents insights into the practical operations of the Sochi project and its legacies, including most recent data on the disbursement of its budget.

Introduction

The 2014 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games, whilst belonging to the world’s most premium sporting competitions, have become particularly prominent as travelled to Russia due to the scale of politics and money invested in their preparations, as well as their far-reaching consequences for the relationships between sport and territorial development. After the Sochi Winter Olympics, sport in Russia has become more closely associated with economic geography and a political economy of place. Sport, of course, always has a spatial, geographical dimension. Sports achievements, as embodied in performing athletes, have territorial citizenship; these achievements are also remembered from particular events happening in particular locations. The necessary eventness of sport gives prominence to the location – by hosting popular events, national and local elites ‘advertise’ their territories both internally and externally. This logic and its implications, positive and negative, are well acknowledged in literature (e.g. Eisinger Citation2000, Gold and Gold Citation2010). What is rather specific about the Sochi case, however, is the extent of the Russian state’s emphasis on the location.

Sochi is a relatively small, third-tier city in Russia, which is not even a regional capital, but with the scale of investment associated with the preparation for the Winter Olympics in the range of $50 billion, which translates into well over $150,000 per head of the city’s (pre-Olympic) population, Sochi clearly stands out. This fact has already produced many headlines, questioning the rationale and prudence for spending so much money on a single event, even if with the Olympic status. What remains concealed behind those headlines is that the four-fifth of that budget was spent not on sport but on regional transformation. Indeed, the 2014 Winter Olympics has provided the Russian state with a leverage for quite a thorough infrastructural overhaul of Sochi and the wider region hosting the city (Krasnodar Kray). This already puts Sochi on par with major infrastructural development programmes. If understood as a mega-infrastructural project, even the $50 billion budget becomes less conspicuous in international comparison – for example, the high-speed railway link between London and Manchester (HS2), currently the major infrastructural project in the United Kingdom, was estimated to cost only the public budget £56.6 billion ($87 billion) in 2014 prices (House of Lords Citation2015).

Mega-events-as-mega-projects, involving huge public budgets for infrastructure and regional development, may seem to be an echo from the Keynesian era of interventionist mega-projects (Altshuler and Luberoff Citation2003), but leveraging mega-events as an opportunity to promote ‘strategic’ locations fits well into the present-day neoliberal modalities (Brenner and Theodore Citation2002, Hall Citation2006). The neoliberal state is not a disappeared state; on the contrary, it is actively involved in managing spatialities, if only driven by a different ideology from that of the Keynesian state. Neil Brenner, talking from the experiences in Western Europe, suggests that unlike the Keynesian state, the neoliberal state is no longer interested in balancing development within national territories but rather pursues strategies of ‘reconcentrating the capacities for economic development within strategic subnational sites such as cities, city-regions and industrial districts, which are in turn to be positioned strategically within global and European economic flows’ (Brenner Citation2003, p. 198, original emphasis). This politics involves a shift from the all-nation redistributive modalities of the Keynesian regime to targeted pro-growth interventions, which take uneven development not as a barrier but rather a very source of competitiveness and growth (Brenner Citation2004). The boosterism promise of the sports mega-event spectacle certainly dovetails with that logic of competitive selectiveness and extravertedness (McCann Citation2013).

The focus of the Russian state on Sochi similarly signifies the selective extraverted modalities of spatial governance. However, this needs to be specified not simply against a post-Keynesian or post-welfare state, but also against the Russian post-socialist state, which has experienced much more radical shifts in its regulatory landscape under transition in the 1990s – from a state-controlled planned economy to a rapid retrenchment of the state and a substantial withdrawal of the federal state from spatial development policies (Golubchikov Citation2004). However, as I will demonstrate, recent years have seen a number of policies through which the federal state is regaining the territorialisation of its economic development institutions. I will argue that the Sochi Olympics spearheaded that major turn – as a space of experimentation – gradually leading to a return of geography among national development priorities, and a selective return of the federal state in urban development. In other words, Sochi has been instrumental for the re-engagement of the Russian federal state with spatial governance following its retreat after the collapse of the Soviet Union. This is not a return of the Soviet redistributive welfare state; rather, to the extent that the thesis of the variegation of neoliberalism holds (Brenner et al. Citation2010), Russia has produced its own variant, engaging with the neoliberal ideology, but in the context of a strong central state and with a growing recognition of the importance to support peripheral regions. The Sochi case thus represents juxtaposition of general and contextual tendencies. Indeed, as Horton and Saunders (Citation2012, p. 891) note regarding the complex exclusiveness of each Olympic Games:

Even though the fundamental principles of Olympism, found in the Olympic Charter are most specific, each individual Olympic Games is conducted and also characterised, as it should be, by reference to the hosting city, the hosting nation and the hosting culture. Each should therefore be considered unique.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. I start with problematising the state rationale behind the Sochi Winter Olympics vis-à-vis what the hegemonic discourse on the politics behind the Sochi Winter Olympics and its ignorance about Russia’s politics of space. I then turn to discussing the Sochi project in light of the broader evolution of spatial governance in Russia. Following on from that, I will also discuss the practicalities of the Sochi project – its economics and its legacies, demonstrating the scale of change achieved by the state’s involvement in the regional development, as well as its costs and implications.

The state’s rationales behind hosting the Sochi winter Olympics?

The surge of expensive mega-events in Russia, which coincided with the intensified geopolitical tensions between Russia and the West, has attracted some interest in international literature. Several special journal issues recently discussed Sochi and other post-Soviet mega-events, for example: Sport in Society (Petersson et al. Citation2015), European Urban and Regional Studies (Müller and Pickles Citation2015); East European Politics (Müller Citation2014b); Problems of Post-Communism (Arnold and Foxall Citation2014). These and others predominantly attribute the Russian leadership’s logic for spending massive resources on these events as a desire to demonstrate Russia as a re-emerging great power externally and to legitimise Vladimir Putin’s personal power domestically. Following the Western media’s dominant representation (for a review see Wolfe Citation2015), a prevailing ethos is, however, that the Sochi Winter Olympics and the other sports mega events in Russia end up in rent-seeking and destructive practices – socially, economically and environmentally – which are remote from their declared intentions and which contribute only marginally, if at all, to material progress in the country or the host regions. While such discourses are set against the underlying negativities directed at Putin’s Russia by the Western epistemic communities in the context of the geopolitical struggles, Grix and Kramareva (Citation2015) observe that such discourses also dovetail with the more engrained Western assumptions of self-righteousness and of the inferiority of emerging and developing economies in handling mega-projects. This certainly echoes colonial mind sets which differentiate between the superior and inferior, deserving and underserving worlds – as always morally justified: in the past by the convenience of racism and recently by the expedience of democracism. For instance, as stated in the introduction to one of those special issues quoted above: ‘one logical and morally justifiable argument would be not to award such events to irreputable states with dubious democratic credentials in the first place’ (Petersson et al. Citation2015, p. 3).

Such discourses set aside, the preoccupation with the thesis that mega events in Russia have been designed to sustain the political status quo internally and showcase the regime externally (and reverberations of this thesis) also centres the direction of the debate on a one-dimensional understanding and not only obscures more down-to-earth reasoning, such as the needs for sport development, but also fails to capture the major transformative processes happening alongside those events. Müller (Citation2011, p. 2091) argues that the Russian federal state’s involvement in the Sochi project ‘is underpinned by a nationalist narrative which frames the Olympic Games not primarily as a stimulus for economic development and global competitiveness but as a contribution to Russian greatness’. Without doubt, hosting the Sochi Olympics was a moment of national pride, à la ‘make Russia great again’, which was well celebrated in the Russian media circulations. After all, the Olympics have long been recognised among those vehicles that assist in the constitution of the nation by bringing in national pride and unity (Anderson Citation2006). The sense of national pride and as its geopolitical extension, the host nations’ desire to boost their soft power is present in any sports event with a global status (Grix and Brannagan Citation2016). But I would question Müller’s ‘not primarily’ emphasis as far as the Russian government’s rationale is concerned. If anything, the manifestation of ‘economic development’ and ‘great power’ is not so much mutually exclusive; but, more importantly, the implications of the Olympics for the urban, regional and national economic development have been continuously underplayed in literature despite these rationales were exactly what Russian government primarily insisted on.

There are, of course, exceptions. Trubina (Citation2014) focusing on the interplay of mega-events and their spatialities sees Sochi as an event through which Russian urban transformations become internationally connected and which as such will already have a lasting legacy. However, in line with the tendencies of post-socialist studies to see urban change as a projection of social change rather than a dimension of social change (Golubchikov Citation2016b), Trubina only treats Sochi as ‘the most visible expression of the spatial dynamics of Russia’ (p. 623), not as a vehicle of transformative changes. As Flyvbjerg (Citation2014, p. 6) argues, however, mega-projects ‘are designed to ambitiously change the structure of society, as opposed to smaller and more conventional projects that … fit into pre-existing structures and do not attempt to modify these’. This is much relevant to the Sochi case. I would argue that the Sochi Games sought not only, and probably not so much, to put Russia on the world map (Bridge Citation2014) or even to boost Putin’s power base (Persson and Petersson Citation2014), but also to remake Russia’s geography altogether (Golubchikov and Slepukhina Citation2014). This top-down project of the restructuring of the geography certainly creates its own problems – indeed, it in many respects exacerbates uneven geographical development rather than resolves it – but its logics and consequences need to receive due attention to counterbalance the customisation of the ‘Putin’s flexing his muscles’ as an all-explanatory narrative for the new Russia.

For a start, let us have a look at the official justification for hosting the Winter Olympic Games in the Federal Target Programme (FTP) for the Development of Sochi as a Mountain-Climate Resort (RF Government Citation2006). The FTP, which was developed to frame the Olympic bid, contained two scenarios, inclusive and exclusive of winning the bid, both of which shared objectives that could be clustered into the three broader categories:

Making Sochi as Russia’s first world-class alpine resort, as well as all-year-round resort:

The development of Sochi’s physical infrastructure;

modernisation of its urban environment;

promoting Sochi as a tourist destination, making it competitive against leading international alpine resorts;

increasing the standards of living in Sochi and acceleration of the gross regional product of the Krasnodar Kray, including by achieving a multiplication economic effect from the programme’s implementation.

Providing all winter sports venues within Russia:

The provision of Russia’s elite athletes with training venues in all winter sports (most of which had to be hired outside Russia);

giving Russia the ability to host international and Russian championships in winter sports;

raising popularity of sports within Russia.

Raising Russia’s international prestige.

The modernisation of Sochi as a place, in conjunction with winter sport development, was prioritised – and, I would argue, largely achieved. The logic of using the Winter Olympics as a leverage for regeneration and giving a new identify to Sochi has been frequently repeated by the officialdom. As, for example, stated by the then President of the Russian Olympic Committee Alexander Zhukov:

The effect of hosing the Olympic Games in Sochi can last for decades, because the quality of the resort city as such is changing. And the sport effect after the creation of the infrastructure will stay forever … Everyone knows that Sochi has been the main summer resort of the Soviet Union and Russia. In winter, its capacities were vacant. The idea has been to make Sochi an all-year-round resort, and the Olympic Games were a good pretext for that … I am sure it would have required many decades to make, without the Olympic Games in Sochi, such a colossal project (ROC Citation2013; translation from Russian).

Of course, one can claim that the official prose does not reflect the real objectives, and that the real purpose needs to be reconstructed through deciphering the meanings of actions in the domain of interpretive politics. Such meaning-making is important, but it is not without the in-built epistemological fallacy of confirming the preconceptions of the meaning-makers. One can, of course, further argue that the ‘truth’ is never singular, and, moreover, what is ‘true’ is often irrelevant – for example, if Western epistemic networks ferment particular representations of Sochi, repeated times and times again, they per se have quite material consequences in domains such as international relations, irrespective of whether such representations were substantiated in the first place or not. This may even be nonexclusive of other representations or ‘framinings’, which may equally have their own impacts. Here, one can imagine the Sochi project a polyphony of interpretations of the same ‘story’ (to borrow from Bakhtin Citation1984), where alternative interpretations are assembled and reassembled depending on contingent ‘relations of exteriority’ (to borrow from DeLanda Citation2006, see also Büdenbender and Golubchikov Citation2017). Even so, two considerations are important. First, academic knowledge has at least an in-built inclination to unearth social relationships systematically, while, second, if only some framings are privileged, while significant others not, knowledge becomes distorted, leading to the endless reproduction of privileged ‘decoding’, thus emasculating knowledge as such and missing out other significant transformations. This is exactly why Sochi needs to be unpacked as a polyphony rather than a homophony, recognising the multiple significant aspects of it. Ignoring, more specifically, the regional development rationale embodied in the Sochi Winter Olympics is to lose sight of the major policy-shaping processes, which have structural significance for the Russian state, particularly in terms of how national space is shaped and governed.

I will now turn to argue below that hosting the Olympics was not an isolated piece of policy, but part of a broader reorientation of spatial governance.

Regional policy and spaces of modernisation

The Russian system of spatial governance has experienced much change since the demise of state socialism and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 as the all-nation economic planning system was abandoned (e.g. Golubchikov Citation2004, Golubchikov and Phelps Citation2011). Since then, the Russian Federation’s policies emanating from the federal centre focused on particular economic sectors (e.g. industry, agriculture, housing, defence and so on) rather than on territorial development. The latter was rather ‘devolved’ to regional and local authorities. Even ‘regional policy’ became fragmented, appearing either as a sum of subnational regions’ own policies or, alternatively, as the administrative and fiscal (inter-budget) relationships between the federal centre and regional governments, rather than as a more traditional regional policy focused on territorial development (Satarov Citation2004, Kuznetsova Citation2015). The only federal enactment in the field of regional policy, the 1996 Degree of the Russian President ‘On the Basic Principles for the Regional Policy in the Russian Federation’, remained largely declarative. National-level statutory spatial planning was abandoned with the Soviet system of economic and spatial planning but not compensated by national-level urban or spatial policy. At the same time, on the ground, cities and regional have a limited fiscal autonomy to realistically pursue independent strategies, even more so after the fiscal centralisation under the ‘power vertical’ [vertikal’ vlasti] under Putin’s rule, but also due to the processes of economic polarisation, with the concentration of national wealth in places like Moscow and some regional capitals (Golubchikov et al. Citation2015).

There has been a crying demand for national spatial policy. Indeed, the latter seems to have been forming in the past decade or so, even if as a bumpy process. Previous studies (Kinossian Citation2013, Golubchikov et al. Citation2014) have demonstrated how by around 2005–2006, some fractions in the Russian government became preoccupied with the idea of ‘polarised’ development, where a central role would be given to so-called growth poles or growth engines, understood as territories already proven to be economically successful. It quickly became apparent that the idea was too controversial in the context of the already strongly polarised Russian geography. Voices of discontents were subsequently pacified by a renewed rhetoric on regional equalisation. This did not purge the idea of growth poles as such; the latter was rather merged into the discourse on regional equalisation. For example, the 2008 Concept for Long-term Socio-economic Development of the Russian Federation until the year 2020, while declaring the need to mitigate inter- and intra-regional disparities, maintains the importance of making ‘growth poles’, but now in every region, as a vehicle towards achieving greater levels of inter-regional equalisation (Kinossian Citation2013). Nevertheless, the ambivalence over the formulation of new regional policy is evidenced by the unusually high number of the drafts of federal concepts and laws on this topic proposed in 2005–2011 but never enacted,Footnote1 as well as the continuous reorganisation of federal departments responsible for regional policy.

In practice, the logic of the ‘territories of accelerated growth’ was operationalised by ad hoc support to certain territories (Golubchikov Citation2010). Government’s investment of large sums of public money in specific localised ‘hotspots’ projects has become a favoured format. Not only in Russia, but also in other ex-Soviet states, a de-facto national urban policy has been much shaped around event-based regeneration, such as in the context of hosting major sporting and cultural events and political summits (Golubchikov and Badyina Citation2016). Apart from Sochi and FIFA World Cup 2018, notable examples of event-based regeneration in Russia included the APEC summit in Vladivostok in 2012 and the 2013 Summer Universiade in Kazan ().

Table 1. Examples of event-driven urban regeneration projects in Russia.

In 2009, Dmitry Medvedev, then the Russian President, famously announced his modernisation agenda, which shaped much of his presidential term (Medvedev Citation2009). In an opening speech at the World Economic Forum in Swiss Davos, he put sports mega projects in his list of 10 priorities for Russia’s modernisation, which otherwise included topics such as privatisation, financial sector, innovations, energy efficiency and internet (Medvedev Citation2011):

[W]e have begun carrying out big infrastructure projects, especially as we have been chosen to host major international sports events. This is not just our sports fans’ desire, but is a real opportunity to modernise our infrastructure, and it was precisely our goal to make our infrastructure more convenient for our people, for business, and for trade. These projects will all be carried out on a public-private partnership basis. They will help us to develop individual regions....

This focus on sports mega events as one of the drivers of modernisation was frequently repeated by the officialdom. The President of the Sochi 2014 Organizing Committee Dmitry Chernyshenko said in 2012 that it was a deliberate strategy of the Russian leaders: ‘[r]edevelopment of our country by holding big sporting events is key to our economic development’ (Fox Sports Citation2012).

While Sochi has been privileged in these discourses, the preparation for Sochi was surrounded by other forms of experimenting with the territorialisation of federal economic policies. These included, for example, discourses on ‘urban agglomerations’ as a favoured spatial organisation for accelerated development (Golubchikov et al. Citation2014) and the idea of innovation clusters – such as regional innovation clusters, special economic zones, technological and industrial parks, zones of territorial development – as new spatial units with special (and often especial) legal provisions and public co-funding. The combination of these policies with urban entrepreneurism activities emanating from Russia’s regional administrations too, seeking to promote their regional capital cities, has elevated the importance of urban regeneration and urbanism in Russia more generally (Allan and Khokhlov Citation2011). Preparing for the Sochi Winter Olympics certainly played a key part in this elevation (Trubina Citation2014), along with other government-led initiatives, such as the expansion of the administrative territory of Moscow in 2012 (Argenbright Citation2011), as well as the external impulses coming with the grand urbanism projects in Russia and other post-Soviet capital cities (Salukvadze and Golubchikov Citation2016).

The territorialisation of federal development priorities was further accelerated, only if with a more explicit equalisation focus, with Vladimir Putin’s returning into the seat of the Russian President in 2012. A number of area-based federal ministries were created for some of the most problematic peripheries of Russia. These were headed by Deputy Prime Ministers, thereby upscaling the priority of these vectors of development, including the Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East (established in 2012), the Ministry of North Caucasus Affairs (2014), as well as the short-lived Ministry of the Crimea Affairs (2014–2015). A ministry for the Arctic has been another proposition (Kinossian Citation2016). Regional policy as such was upscaled by vesting it into the responsibility of the powerful Deputy Prime Minister – Dmitry Kozak – who also supervised the preparation of the Sochi Olympics. A number of laws were enacted to support emerging policies, such as the 2014 Federal Law on Strategic Planning, which introduces the concept of a spatial development strategy of the Russian Federation as a whole, and the 2014 Federal Law ‘On the Territories of Accelerated Socio-Economic Development in the Russian Federation’. According to the latter, the creation of such territories should target Russia’s Far East, as well as overspecialised towns [monogoroda] falling into the class of those with the ‘gravest socio-economic conditions’. This indicates that even if the ‘growth pole’ thinking prevails, it has been extended to favour some of the least advantaged areas.

To recapitulate, Russia’s federal regional policy has seen a resurgence in the past decade and currently represents an ensemble of several mechanisms (see also RF Government Citation2016):

Strategies for the development of the Russian ‘frontier’ (peripheral administrative regions and mega regions): the Arctic, the Far East, and North Caucasus mega regions, Kaliningrad Oblast and Crimea;

policies and initiatives addressing certain urban forms and functions: promoting urban agglomerations/metropolitan governance, reforming single-industry towns;

special-purpose policies for making territorial clusters of accelerated growth: special economic zones, industrial parks, technoparks, industrial and agro-industrial agglomerations, innovation clusters.

ad hoc federal regimes for regenerating and promoting particular cities, leveraged by means of hosting significant events.

The ‘soft spaces’ of spatial governance

The Sochi Winter Olympic project belongs to the latter, ad hoc, set of spatial policies – but in many respects, Sochi was a vehicle for the formulation of the other policies altogether. Particularly so, as the preparation for Sochi was a steep learning curve for the federal government – who learnt not only about the importance of comprehensive regional regeneration, but also about its own possibilities and limits in shaping places directly, bypassing or overcoming administrative hierarchy (i.e. federal–regional–municipal levels), or to borrow from Brenner’s (Citation2004) scalar lexicon, how to ‘jump scales’ in dealing with the local territories of assigned national significance. This was not necessary a straightforward policy process, even in the context of the quasi-authoritarian state, given the colossal amount of work involved in preparing for any Olympics and especially in Sochi, in the context of the absence of suitable pre-existing sports infrastructure, but also given that this process had to rub up against all sorts of pre-established hierarchies and practices in Russia, vested interests and conflicts and had to engage with various interpersonal and interorganisational networks, involving international, national and local actors, public and private, business and civic, while also providing necessary regulatory and procedural frameworks and leveraging huge budgetary, extra-budgetary and non-budgetary/corporate funds, including through demonstrating the formal and informal leadership of the federal centre and performing the power of order, persuasion or pressure in order to get things done as designed, planned and needed. In other words, Sochi has been a site of experimentation for the Russian government, emerging outside of the more traditional spatiality of hierarchy and regulation.

Some argue that the existence of such selective ‘development-by-decree’ spaces is something special about the modus operandi of quasi-authoritative regimes (Kinossian and Morgan Citation2014). However, such selective spaces of planning and management rather represent a variant of what has been described elsewhere as ‘soft spaces of governance’. While the concept of soft spaces may be criticised as one of those fuzzy ones, it does articulate some important practices of institutional experimentation with regard to spatial governance. According to Haughton et al. (Citation2013, p. 218), ‘[s]oft spaces of spatial governance exist both beyond and in parallel to the statutory scales of government, often involving the creation of new territorial entity which sits alongside and potentially challenges existing territorial arrangements or the dominance of particular scales of governance’. According to this conceptualisation, soft spaces are spaces of special, often high-profile selective initiatives, which are counterposed against more formal and normal units of administrative structure and regulations (or ‘hard spaces’). Such special spatialities of planning and regulations are set to expedite planning systems and overcome potential disconsensus: ‘[s]oft planning spaces have played an important role in mediating and translating neoliberalism, providing flexible and ephemeral experimental spaces and alternatives to costly and disruptive reorganisation of hard, statutory spaces’ (Haughton et al. Citation2013, p. 227). These authors’ conceptualisation of soft space dovetails with Brenner’s (Citation2004) conceptualisation of new state spaces discussed above, although possibly as a less systemic, more ephemeral mechanism – although soft spaces are also seen as able to ‘harden’ into new dominant spatial regulations. As Allmendinger et al. (Citation2015, p. 4) explain:

Soft space forms of governance typically involve diverse mixes of actors, including government, civil society and the private sector, creating new networks that may vary according to the project or thematic policy area under construction. Typically they are intended to allow new thinking to emerge and to provide testing grounds for new policy interventions.

The Russian government’s ways of governing spaces by new forms of regulation – such as loosely defined agglomeration and selective spaces of regeneration via mega-events, involving multiple actors and networks – fit well into such definitions and discussions. These policies similarly represent ad hoc constructions of space that do not correspond to the more traditional political hierarchy of territorial governance and ‘normal’ constitutional orders but emerge in parallel or even in contradiction to them (Kinossian and Morgan Citation2014).

These practices are not the ones that could systematically mitigate structural spatial polarisation; but at least they have been conducive to the emergence of a ‘spatial literacy’ within national government over the importance of spatial and urban policies in shaping the national economy. Rather than continuing to ignore Russia’s complex urban and regional problems, the high-level articulation of this problematic did activate the return of geographical consciousness in the federal centre’s policy-making and more explicit territorialisation of national development strategies.

But why all this effort to ‘experiment’ with Sochi in particular? Possibly part of the explanation lies with that the city’s being favoured by Vladimir Putin as one of his residences, where he regularly conducts official and international meetings (Khimshiashvili and Biryukova Citation2014). However, the choice of Sochi as an Olympic host seems to be more than such vagaries. Sochi is an important geostrategic location, even if peripheral, at the Black Sea and the Caucasus, at the border with Georgia (or, more precisely, its breakaway republic of Abkhazia, recognised as an independent state by Russia). Sochi has also since the end of the 19th century been associated with one of Russia’s best sea resorts. The development of this area is therefore important if Russia wants to achieve greater poly-centricity in its regional development. Indeed, the idea of making Sochi as a host for the Winter Olympic Games does not even belong to the Putin Government; Sochi has a history of bidding for the Olympics along with only two other Russian cities having done so, Moscow and St Petersburg. The idea was, for example, entertained back in Soviet 1989, when local government was preparing a bid for the 1998 Winter Olympics, but then, on the brink of the collapse of the state-socialist regimes, the Soviet government failed to provide the IOC with necessary guarantees (Zakharova Citation2011). In 1993–1994, Sochi was an official candidate city for the 2002 Winter Olympics, albeit unsuccessful. In 1999, Sochi was again preparing a bid, this time for the 2008 Summer Olympics, but the application was never formally launched (Bandakov Citation2007). This saga culminated in July 2007 when Sochi was selected to host the 2014 Winter Olympics. Putin then personally put much effort in making this happens, while the Russian government offered strong financial guarantees and a development vision.

In order to further explore the actual manifestations of the policies discussed and their leveraging, including their advancements and limits, I will turn in the next sections to a consideration of the economics and legacies of Sochi more directly.

The cost of Sochi: the most expensive Olympics ever?

Sochi has become the first Olympic city for which the entire main sports infrastructure was constructed from scratch and the general infrastructure and hospitality sector were thoroughly remade. Overall, more than 800 construction items were reportedly built in Sochi. Some of these were, of course, sporting facilities, but most of the cost was associated with a generic upgrade of the urban and regional infrastructure, including power stations and supply, new water and sewerage systems, telecommunications, a massive transport network, and so forth. The dual purpose of the Olympics preparation programme was reflected in its official name: the FTP for the Development of the City of Sochi as a Mountain-Climate Resort. The following developments were reported with regard to infrastructure more specifically (IOC Citation2015a):

New airport facilities;

a new seaport for passenger liners, ferries and personal boats;

367 km of roads and bridges;

200 km of railways, with 54 bridges and 22 tunnels;

967,400 square metres of road surface and pavements;

480 km of low-pressure gas pipelines;

two thermal power plants and one gas power plant with a combined capacity of 1200 MW;

550 km of high voltage power lines;

a new water and wastewater treatment facility;

three new sewage treatment plants;

60 new educational, cultural and health facilities;

25,000 additional hotel rooms, with 56 hotels rated four-star and above;

a new theme park – Sochi Park;

a new graduate-level Russian International Olympic University.

The associated expenses are commonly reported as US$50 billion. This corresponds to the official figures of Olimpstroy, the state corporation that oversaw the Sochi development. In its 2013 (final) budget statement published in June 2014, it reported the total allocated funds of RUB 1524.4 billion (US$49.5 billion), with the funds actually spent by the end of 2013 of RUB 1415.2 billion (US$46.0 billion) (Olimpstroy Citation2014).Footnote2 The figure of RUB 1524 billion has also been officially reported as the final costs of the programme.

These calculations cover all the costs that fall under the remit of regenerating Sochi into an all-year-round alpine and sea resort, including urban and infrastructure development and redevelopment. But how much of that cost is related to the Olympics as such versus a more general infrastructural upgrade? This question is important, as the issue of cost itself has become part of the mythology of Sochi as ‘the most expensive Olympics ever’. Yet, this question is not straightforward in answering, as it depends on what to include in or exclude from Olympics-related costs. Flyvbjerg et al. (Citation2016, p. 7) divide the costs for hosting the Games into three categories: (1) operational costs incurred by the Organising Committee for the purpose of running the Games, including technology, transportation, workforce, administration, security, catering, ceremonies and medical services; (2) direct capital costs incurred to build the competition venues, Olympic villages, international broadcast centre and media and press centre, which are required to host the Games; (3) indirect capital costs such as for road, rail or airport infrastructure, for hotels and other business investment incurred in preparation for the Games but not directly related to staging the Games. Only the first two items are considered sports related.

According to the Accounts (Audit) Chamber of the Russian Federation (ACRF Citation2015), Russia’s principal financial watchdog, the direct cost of hosting the Games and sporting facilities was RUB 324.9 billion ($10.6 billion), including RUB 103.3 billion ($3.4 billion) directly funded by the federal budget. This suggests that 21% of the total Sochi spending can be attributed to the Olympics-related side. It is possible to reassess these estimates and provide a more nuanced cost breakdown on the basis of the final report of Olimpstroy (published only in June 2014 it has been overlooked). While Olimpstroy only differentiates the costs of the Olympic venues from other costs but not clearly between direct Olympics-related and indirect costs, I provide a breakdown of different cost categories in , following a nuanced attribution analysis of the allocated funds of RUB 1524.4 billion (US$49.5 billion), triangulated with other sources and government documents. From this, the direct Olympics-related costs include (a) the construction of the competition venues – $7.2 billion; (b) site preparation and supporting infrastructure necessary for the functioning of the Olympic venues – $2.8 billion, and (c) operational costs for staging the Olympics – $0.8 billion. These direct costs – $10.8 billion in total – are generally in line with the estimates of the Accounts Chamber above, if only at a higher level, but, again, it is difficult to attribute Olympics-related costs precisely, especially as many costs were reported in aggregated way.

Table 2. The breakdown of Olimpstroy’s final budget (funds allocated).

Müller (Citation2014a) has previously provided a somewhat higher estimate for sport-related capital cost – $11.9 billion – but that was based on Olimpstroy’s penultimate reports. However, he also suggests that the total sport-related costs need to also include the operational costs of the Sochi 2014 Organising Committee (SOCOG) and that of security provision, which were probably not fully reflected in the Olimpstroy’s budget. He placed these costs at, respectively, $2.3 billion and $1.9 billion, based on insights from the Vedomosti broadsheet (Tovkaylo Citation2011, Rozhkov Citation2014a). It is indeed hard to find out those operational costs and it is unclear to what extent they were already part of Olimpstroy’s budget or on top of it. Following the Olympics, SOCOG reported revenues of RUB 85.4 billion (ACRF Citation2015) and an operational surplus (i.e. that its revenues from sponsorship, ticketing, licencing etc. exceeded its expenditures, Rozhkov Citation2014b), but the running costs per se and their breakdown were not reported. It is yet known that SOCOG received federal subsidies of RUB 15.6 billion (RF Government Citation2013a), of which RUB 1.6 billion was unused and returned back to the budget system (ACRF Citation2015). Further, the IOC contributed $833 million (IOC Citation2015b). From this, it is possible to estimate that at least $1286 million was unrecoverable (public) operational costs. As for security, Tovkaylo (Citation2011) quoted an anonymous government source who gave an estimate for the security budget at RUB 57.8 billion (£1,877 million). Even if part of this might be included in Olimpstroy’s capital costs for ‘hardware’ installations, it is also likely that the final security cost grew further. In short, additional unrecoverable operational costs could have added at least $3163 million to the Olympics budget, resulting in a total of $13.9 billion as a conservative but relatively documentable estimate for Olympics sport-related costs.

Whatever is the case, the consideration of the breakdown of the capital costs in demystifies Sochi’s ‘$50 billion’. Taken overall (both direct and indirect costs), the budget is dominated by physical infrastructure and associated works – 59%, followed by the hospitality and real estate sectors – 26% and sports venues (Olympic and non-Olympic, including Formula One) – 12%. This confirms that the predominant focus of the investment was on urban regeneration and infrastructural development.

But who paid for these expenses? Hosting large-scale projects, whether mega-events or infrastructural projects, in Russia does particularly rely on government administrative leverages. The main sponsors of the Olympics have been large corporations, most of which are state-controlled (such as Gazprom and Rosneft), while key private investors took state-underwritten credits from state-owned banks (VEB and Sberbank). The oppositional Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK Citation2014), on the basis of its analysis of corporate reports and federal budgets, has estimated the following breakdown of the (roughly) RUB 1.5 trillion of the Sochi costs: direct public budget costs – RUB 855 billion; expenses of state-controlled corporations – RUB 343 billion; VEB’s loans to companies – RUB 249 billion; equity of private companies – RUB 53 billion. Further, it is likely that a large portion of VEB’s loans will be written off or restructured. Indeed, Müller (Citation2011) discusses in details the state–corporate relationships in preparing the Sochi project through the lens of state dirigisme; he identifies a rather peculiar pattern of relationships, where the involvement of big business in the project was more about demonstrating a loyalty to the state than achieving profits as such. This can explain the rather unrestrained scope of various expensive projects achieved in that short period of time before the Olympics.

The high bill for the Winter Olympics and particularly its inflation since 2007 have attracted much criticism, both within and outside Russia, especially as state finances were greatly exposed. Indeed, Russia’s original bid already envisaged comprehensive infrastructural investments but estimated the cost at RUB 313.9 billion (or US$11.3 billion at the exchange rate prevailing then).Footnote3 If rouble inflation is factored in, RUB 313.9 billion in December 2005 translates into RUB 618.5 billion in December 2013, meaning that the real overspend was less than in direct comparisons (especially given that the scope of the ‘Olympic’ projects had also increased).

Apart from the increased scope of the Sochi programme, the overspends are attributed to a number of factors – notably a lack of sufficient preparatory investigations at the bidding stage, and underestimations of the extremely challenging engineering conditions in the swampy Imereti Valley and other areas where the projects were built. Other factors included a poor quality of the initial design specifications, additional emerging requirements of the IOC and inflation (RBC Citation2013, Yaffa Citation2014). Embezzlements and kickbacks were endemic and certainly played a role too (Golubchikov, Citation2016a). But even private investors experienced considerable overspends; for example, Interros, the main investor and owner of the Rosa Khutor Alpine resort, was reported by Forbes (Citation2014) to have seen a sixfold increase in its costs, from the planned US$350 million to US$2.07 billion.Footnote4

The legacies of the Sochi winter Olympics

The growing cost made public support for the Games to be constantly diminishing within Russia in the proximity to the Olympics, because of not only the growing awareness of opportunity costs, but also scandals over corruption allegations and delayed constructions. But it was the Western media that were particularly harsh, expressing explicitly the expectations of a gross mismanagement of the forthcoming Games. Even so, the main points of Western criticism focused on factors largely external to the Olympic preparations, such as gay rights (e.g. Gibson and Luhn Citation2013) or security in the North Caucasus. These were and remain, of course, legitimate concerns, but in its unbalanced coverage, the media machine was pushed to its limits; according to Wolfe (Citation2015, p. 6), who specially reviewed this aspect, in some cases ‘even to the point of hysteria and hyperbole … these negative storylines dominated international attention even with outright fabrications’. Thus, even legitimate concerns were distorted beyond any reasonable proportion to create a specific affective ambience. For example, the Economist (Citation2013) threatened its readership to the following extent: ‘Imagine holding the games in Kabul’.

As the Games began, much of that propaganda diluted over the appreciation of the successfully staged and enjoyable championship (e.g. Chadband Citation2014, Wolfe Citation2015). But the Olympics were soon overshadowed altogether by the intensifications of geopolitical tensions, this time over the coup in Ukraine, culminated with Russia’s annexation of Crimea as the Olympics were concluding, followed by a civil war in Eastern Ukraine. All this has provoked a wave of discussions whether the image of Russia has actually become any better as the result of the Games. Some suggested that Russia had ‘wasted’ $50 billion on improving its image through the Sochi Games (Miller Citation2014). Joseph Nye, who promoted the idea of ‘soft power’ to the global discourse (Nye Citation2005), echoed that claiming that Putin ‘failed to capitalise on the soft-power boost afforded to Russia by hosting the 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi’ (Nye Citation2014). Some, on the contrary, argued that if the purpose was indeed to demonstrate a more powerful Russia geopolitically, then the whole chain of events in early 2014, including the Olympics and the annexation of Crimea, was not mutually contradictory (Makarychev and Yatsyk Citation2014). However, returning to the point that I insisted on above – that the external image was secondary to the spatial development imperatives in the Russian state’s priorities – the expectations that the Putin government’s external politics would somehow become hostage of Sochi were based on wrong calculations.

As for the physical legacy of sport venues and other Olympic facilities, outlines the post-Olympic use of the key of them. Although a cluster approach, used for concentrating and separating the indoor and outdoor activities, produced a concentration of all activities in the two Olympic areas, thus preventing traffic congestion, providing easier access and facilitating security measures, it also raised the issue of remoteness. On this basis, many commentators were quick to prophesy that the key stadiums were doomed to collect dust and fall into white elephants. Although a direct payback on the investment in these facilities is indeed questionable (Müller Citation2014a), the future is by no means predetermined here. What is often overlooked is that the centralisation of power in Russia also means the immediacies of administrative levers – the future of using the stadia will depend on how much priorities the Russian state will make for this.

Table 3. The post-Olympic use of the key sporting facilities built for Sochi 2014.

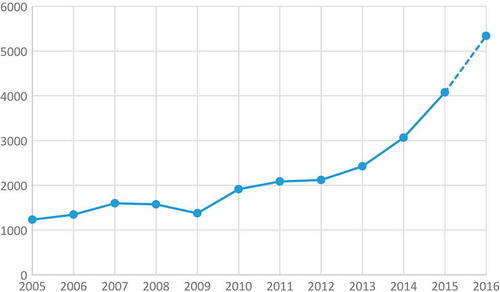

Yet, beyond sports legacy, the city has been thoroughly retrofitted, while the continuous media and government attention, government-sponsored conferences and meetings and other events in Sochi have made the city an easily recognisable ‘brand’ for tourism. Without doubt, the holding of the Winter Olympics has changed not only the hitherto deteriorating resort city but also the mental geography of Russia in the eyes of the Russian population itself. This is reflected in the rise of tourism to Sochi. After the years when Sochi was dubbed ‘Russia’s largest construction site’, since 2014, it began enjoying an increase in visitor numbers. The trend has been maintained after the Olympic Games, through the rest of 2014 and well into 2015 and 2016. The city administration estimated 6 million tourists coming to Sochi in 2015 (RSN Citation2016), a rise from the 5.2 million arrivals in the Olympic 2014 (Vorobyev Citation2015), and up on the estimated 3.7 million in 2006, before the Olympic project. The new numbers are already exceeding the 5 million tourists in the heyday of the Soviet Sochi. The passenger turnover in the Sochi airport grew from 1.2 million in 2005 to over 4 million in 2015 and is likely to exceed 5 million in 2016 ().

Figure 1. Passenger turnover in the Sochi airport, 2005–2016.

Data for 2016 is estimated based on a 29% increase in January-November 2016 over the same period in 2015: http://basel.aero/press-center/news/aeroporty-bazel-aero-obsluzhili-bolee-9-4-mln-passazhirov-za-11-mesyatsev-2016-goda/. Data for the other years are cross-checked from Rosaviatsia (Russia’s Federal Agency for Air Transport, www.favt.ru), Basel Aero (http://basel.aero/), Aviation Explorer (www.aex.ru) and other sources.

Tourism helps in returning capital invested in the hospitality business and bringing in jobs and tax revenues (Sochi was expected to accumulate up to 55,000 hotel rooms, exceeding the 41,300 in Moscow according to Tovkaylo Citation2013). Tourists are attracted to Sochi for various reasons: the new or modernised skiing resorts, the Olympic parks, the sea resort facilities and the post-Olympic sporting events (such as the Grand Prix in 2014, some matches of the 2018 World Cup and others, IOC Citation2015a), as well as business events and conferences that the government encourages to go to the city. Furthermore, tourism cannot escape the wider geopolitical context, and Russia’s economic troubles due to the fall in oil prices in 2014–2015 (Demirjian Citation2015). On the one hand, as the real incomes of the Russian population have dropped, many Russians can no longer spend money on tourism – disadvantaging Sochi. On the other hand, as the Russian rouble has lost its international value, many have switched their holiday plans to internal tourism, thus benefiting the city. As further complications, the annexation of Crimea in 2014 – another traditionally prime holiday destination for Russians – represents a competitive challenge for Sochi, but the temporary suspension of organised tourist links with Egypt (over a terrorist bombing of a Russian passenger jet) and Turkey (over its downing a Russian military jet in Syria) in 2015, both of which are also traditional destinations for Russians, have provided a further boost to internal seaside destinations, both to Sochi and Crimea. What is evident, without the Sochi Winter Olympics and regional regeneration and place-making associated with preparing for the event, the internal tourist flows to Sochi would have never materialised to the same extent. The government’s decision to allow from 2017 a gambling zone in Krasnaya Polyana (in the mountain cluster), one of a few such zones in Russia where otherwise gambling facilities are forbidden (while the other gambling zones in Russia are remote and generally unsuccessful) will likely to create an addition boost in tourism and taxes, albeit, of course, of the specific type.

On balance, it appears that Sochi is indeed becoming a magnet for tourism, further sporting events, conferences and other commercial and non-commercial activities – and, indeed, a certain growth pole of national significance – at least as far as the city’s emerging specialisms in those particular services are concerned. Of course, the top-down nature of the Sochi project, imposed on the city from outside, has not been without serious controversies, some mentioned above, but also with regard to what extent the local residents have actually benefited from it as opposed to real estate and big businesses, government or tourist outsiders. The local residents are the ones who endured the years of construction disruption, often combined with a loss of tourism-related income during that period. In addition, hundreds of people were displaced from their former sites where these were subject to compulsory purchase and were compensated only for legally registered properties, not for informal extensions, including those used as guest rooms as a low-cost alternative to hotels. Many Sochi residents therefore remain divided whether the Winter Olympics on balance had actually benefited them (Koshik Citation2015). This is, of course, a generic problem inherent to all mega-events, but from the government perspective, it is yet a matter of political choices – ultimately, a key factor for politicians is the general electorate’s support. After all, a year after the Winter Olympics, according to the Russian Public Opinion Research Centre’s survey, 75% of Russians still supported carrying out further sporting mega-events in the country (RPORC Citation2015).

Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that the Sochi Winter Olympic Games should be seen not simply as an internationally oriented event showcasing ‘great Russia’, but also a precursor experimental space, helping with the formation of the new federal government’s attempts to modernise and restructure Russia’s geography, basing on the premise of promoting selected locations, including on the periphery, as ‘strategic’ (economically and geopolitically) and making them as the nodes of Russia’s spatial modernisation. Sochi has been ‘appointed’ as one such location, with the Olympics working as the catalyst for the city’s elevation within Russian geography.

In this regard, Sochi needs to be seen in the light of the wider political project of Russian modernisation, including the re-emergence of spatial policy in Russia, which seeks to rebalance territorial development away from the mono-centricity of Moscow and to recalibrate the traditional sectoral approach of the federal government’s economic development policy to territorial development and urban policy. Following the degradation of the national regional policy and spatial planning in Russia after the collapse of the planned economy of state socialism, various mega-events and mega-projects have recently become a ‘hook’ for the government to re-territorialise its development institutions and regain control, even if partially and unsystematically, over spatial and urban policy. Sochi has become one of the prominent sites for institutional experimentation with the new spatial governance. As one of the key drivers of the new spatial regime in Russia, the Sochi mega-project is rendered not simply geo-economic functions but essentially geo-institutional functions, articulating the new modalities of state and space.

There are many legitimate concerns about this, including with regard to the issues of territorial justice due to the opportunity costs embedded in centralising state resources in particular locations and, indeed, variegated impacts on different social groups. The scale of mega-projects also makes them less sensitive to public oversight, exposing the democratic deficit and corruption risks. But against the context of the state’s retreat from any comprehensive spatial policy in the 1990s (de-territorialisation), the re-territorialisation of state development institutions has been a significant step in making Russia’s challenging geography more visible among government’s key priorities and actions. It does not necessarily mitigate uneven development between different regions in the country but at least reshapes it to a more polycentric mode.

What is also significant is how far Sochi further blurs the boundaries between sports mega events and development mega-projects, thus deepening the dilemmas as articulated by Holger Preuss in the context of Oslo’s withdrawal from the 2022 Winter Olympics bid; he argues that bidding for the Olympics becomes increasingly a matter of costly infrastructural projects that has no direct financial payback: ‘If you need new sports facilities, if you need new roads and railways, then it’s O.K. But if you don’t need general infrastructure, you shouldn’t bid’ (quoted in Abend Citation2014). Indeed, the Olympics have become increasingly associated with large-scale regional redevelopment and infrastructure projects, where sport plays only a legitimising role. In the era of retrenched welfare state, there are no many other alternative levers that governments can similarly use to legitimise large-scale interventions.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jonathan Grix and the anonymous referees for their helpful suggestions. A previous version of this paper was presented and discussed at the Leverhulme International Network on Leveraging Legacies from Sports Mega-Events’ held in Sao Paulo (September 2015) and Birmingham (June 2016); thanks to the participants for their comments. I would like to thank the Leverhulme Foundation for their support [grant number IN-2014-036]. Usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. These included, for example, Draft Concept Strategy for Socio-Economic Development of Russia’s Regions (2005), The Drat Concept for Improving Regional Policy in the Russian Federation (2008), The Draft Concept for Improving Regional Policy in the Russian Federation until 2020 (2011), Draft Federal Law ‘On Federal Target Programmes for Regional Development’ (2011).

2. The costs in US$ are sensitive to exchange rates for RUB/US$ conversion, which have much fluctuated (and RUB considerably devalued after the Games). Furthermore, it is not correct to convert the total RUB costs into US$ at the date of reporting, as investments are cumulative. Unless stated otherwise, I use a weighted average annual nominal exchange rates of RUB 30.79 per US$ for the five year period of 2009–2013, when the overwhelming majority of spending for Sochi was made. The annual exchange rates are from World Bank (Citation2016). The weights used are 2009 – 10%, 2010 – 20%, 2011 – 20%, 2012 – 25%, 2013 – 25%. This roughly corresponds to the cash flows as reported by Olimpstroy during the preparation period. The weighted exchange rate happens, however, to be only marginally different from the average (unweighted) annual rate of RUB 30.83 for the same period.

3. At the average nominal exchange rate of 27.68 in the first half of 2006 (according to the Central Bank of Russia). The FTP was also allocated RUB 122.9 billion (US$4.4 billion) in case Russia’s bid for the Winter Olympics was declined in 2007. Although that was much less than in the Olympic scenario, it still signifies the strategy of making Sochi a development hotspot irrespective of the Olympics.

4. These figures were likely reported at the exchange rates prevailing in January 2014; the cost of Rosa Khutor as reported by Olimpstroy in 2014 was $2.22 billion (at RUB 30.79 per US$).

References

- Abend, L., 3 Oct 2014. Why nobody wants to host the 2022 winter Olympics. Time, Available from: http://time.com/3462070/olympics-winter-2022/.

- ACRF., 2015. Analiz mer po ustraneniyu narusheniy pri podgotovke i provedenii XXII Olimpiyskikh zimnikh igr i XI Paralimpiyskikh zimnikh igr 2014 goda v Sochi [The analysis of measures on the elimination of irregularities in the preparation and hosting of XXII winter Olympic games and XI Winter Paralympic games of 2014 in Sochi]. Moscow: The Accounts Chamber of the Russian Federation (ACRF). Available from: http://audit.gov.ru/press_center/news/21280 [Accessed June 2016].

- Allan, S. and Khokhlov, O. 14 Sep 2011. Urban regeneration as new driver of public-private partnerships in Russia. The Moscow Times. Available from: www.themoscowtimes.com/article/urban-regeneration-as-new-driver-of-public-private-partnerships-in-russia/443696.html

- Allmendinger, P., et al., 2015. Soft spaces, planning and emergin practices of territorial governance. In: G.H. Phil Allmendinger, J. Knieling, and F. Othengrafen, ed. Soft spaces in Europe: re-negotiating governance, boundaries and borders. London: Routledge.

- Altshuler, A. and Luberoff, D., 2003. Mega-projects: the changing politics of urban public investment. Washington, DC: Brooklin Institution.

- Anderson, B., 2006. Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

- Argenbright, R., 2011. New Moscow: an exploratory assessment. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 52 (6), 857–875. doi:10.2747/1539-7216.52.6.857

- Arnold, R. and Foxall, A., 2014. Lord of the (Five) rings. Problems of Post-Communism, 61 (1), 3–12. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216610100

- Bakhtin, M., 1984. Problems of Dostoyevsky’s Poetics. (C. Emerson, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Bandakov, P., 2007. Istoriya olimpiyskikh zayavok rossiyskikh gorodov [The history of Olympic bids of Russian cities]. BBCRussian.com, Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/russian/russia/newsid_6242000/6242410.stm

- Brenner, N., 2004. New state spaces: urban governance and the rescaling of Statehood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brenner, N., Peck, J., and Theodore, N.I.K., 2010. Variegated neoliberalization: geographies, modalities, pathways. Global Networks, 10 (2), 182–222. doi:10.1111/glob.2010.10.issue-2

- Brenner, N., 2003. “Glocalization’ as a state spatial strategy: urban entrepreneurialism and the new politics of uneven development in western Europe’. In: J. Peck and H. Yeung, eds. Remaking the global economy: economic-geographical perspectives. London and Thousand Oaks: Sage, 197–215.

- Brenner, N. and Theodore, N., 2002. Spaces of neoliberalism: urban restructuring in North America and Western Europe. Blackwell: Oxford.

- Bridge, A., 31 Jan 2014. ‘Winter Olympics 2014: will Sochi put Russia on the map?’, The Telegraph. Available from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/russia/articles/Winter-Olympics-2014-will-Sochi-put-Russia-on-the-map/.

- Büdenbender, M., and Golubchikov, O., 2017. The geopolitics of real estate: assembling soft power via property markets. International journal of housing policy, 17 (1), 75-96. doi: 10.1080/14616718.2016.1248646

- Chadband, I., 23 Feb 2014. Sochi 2014: New Russia revels in the success of the perfect made-for-TV Winter Olympics. The Telegraph. Available from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/othersports/winter-olympics/10657193/Sochi-2014-New-Russia-revels-in-the-success-of-the-perfect-made-for-TV-Winter-Olympics.html

- DeLanda, M., 2006. A new philosophy of society: assemblage theory and social complexity. London: Continuum.

- Demirjian, K., 18 Jan 2015. Russian economic crisis helps save Putin’s post-Olympic dream at Sochi. The Washington Post. Available from: www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/russian-economic-crisis-helps-save-putins-post-olympic-dream-at-sochi/2015/01/17/d8c7bbd8-92b1-11e4-a66f-0ca5037a597d_story.html?Post+generic=%3Ftid%3Dsm_twitter_washingtonpost

- Economist., 11 Jun 2013. Castles in the sand: the most expensive Olympic games in history offer rich pickings to a select few. The Economist. Available from: www.economist.com/news/europe/21581764-most-expensive-olympic-games-history-offer-rich-pickings-select-few-castles

- Eisinger, P., 2000. The politics of bread and circuses: building the city for the visitor class. Urban Affairs Review, 35 (3), 316–333. doi:10.1177/10780870022184426

- FBK, 2014. Sochi 2014: encyclopedia of spending. Moscow: FBK (Anti-Corruption Foundation). Available from: http://sochi.fbk.info/en/ [Accessed June 2016].

- Flyvbjerg, B., 2014. What you should know about megaprojects and why: an overview. Project Management Journal, 45 (2), 6–19. doi:10.1002/pmj.2014.45.issue-2

- Flyvbjerg, B., Stewart, A., and Budzier, A., 2016. The Oxford Olympics study 2016: cost and cost overrun at the games: working paper July 2016. Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Forbes. 30 Jan 2014. Milliarder na Olimpe: kak Potanin stal glavnym chastnym investorom Sochi-2014 [The billionair on the Olympus: how Potanin has become the main private investor of Sochi 2014]. Forbes. Available from: www.forbes.ru/milliardery/250267-milliarder-na-olimpe-kak-vladimir-potanin-stal-glavnym-chastnym-investorom-sochi

- Fox Sports, 9 Nov 2012. A baby boom starts in the Russian city of Sochi thanks to the impending 2014 Winter Olympics. Fox Sports . Available from: http://www.foxsports.com.au/other-sports/a-baby-boom-starts-in-the-russian-city-of-sochi-thanks-to-the-impending-2014-winter-olympics/story-e6frf61c-1226513895191.

- Gibson, O. and Luhn, A., 7 Aug 2013. Stephen fry calls for ban on winter Olympics in Russia over anti-gay laws. The Guardian. Available from: www.theguardian.com/world/2013/aug/07/stephen-fry-russia-winter-olympics-ban

- Gold, J.R. and Gold, M., eds., 2010. Olympic cities: urban planning, city agendas and the world’s games, 1896 to the present. London: Routledge.

- Golubchikov, O., 2004. Urban planning in Russia: towards the market. European Planning Studies, 12 (2), 229–247. doi:10.1080/0965431042000183950

- Golubchikov, O., 2010. World-city entrepreneurialism: globalist imaginaries, neoliberal geographies, and the production of new St Petersburg. Environment and Planning A, 42 (3), 626–643. doi:10.1068/a39367

- Golubchikov, O., 2016a. The 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics: who stands to gain? In: Transparency International, ed. Global corruption report: sport. Abingdon: Routledge, 183–191.

- Golubchikov, O., 2016b. The urbanization of transition: ideology and the urban experience. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 1–17. doi:10.1080/15387216.2016.1248461

- Golubchikov, O. and Badyina, A., 2016. Makroregionalnye tendentsii razvitiya gorodov byvshego SSSR [The macro-regional trends in the development of cities in the ex-USSR states]. Regionalnye Issledovaniya, 52 (2), 31–43.

- Golubchikov, O., Badyina, A., and Makhrova, A., 2014. The hybrid spatialities of transition: capitalism, legacy and uneven urban economic restructuring. Urban Studies, 51 (4), 617–633. doi:10.1177/0042098013493022

- Golubchikov, O., et al., 2015. Uneven urban resilience: the economic adjustment and polarization of Russia’s cities. In: T. Lang, S. Henn, W. Sgibnev, et al., eds. Understanding geographies of polarization and peripheralization: perspectives from central and Eastern Europe and beyond. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Golubchikov, O. and Phelps, N.A., 2011. The political economy of place at the post-socialist urban periphery: governing growth on the edge of Moscow. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36, 425–440. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00427.x

- Golubchikov, O. and Slepukhina, I., 2014. Russia: showcasing a “re-emerging” state? In: J. Grix, ed. Leveraging legacies from sports mega-events. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 166–177.

- Grix, J. and Brannagan, P.M., 2016. Of mechanisms and myths: conceptualising states’ “soft power” strategies through sports mega-events. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 27 (2), 251–272. doi:10.1080/09592296.2016.1169791

- Grix, J. and Kramareva, N., 2015. The Sochi winter olympics and Russia’s unique soft power strategy. Sport in Society, 1–15. doi:10.1080/17430437.2015.1100890

- Hall, C.M., 2006. Urban entrepreneurship, corporate interests and sports mega-events: the thin policies of competitiveness within the hard outcomes of neoliberalism. The Sociological Review, 54, 59–70. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00653.x

- Haughton, G., Allmendinger, P., and Oosterlynck, S., 2013. Spaces of neoliberal experimentation: soft spaces, Postpolitics, and neoliberal governmentality. Environment and Planning A, 45 (1), 217–234. doi:10.1068/a45121

- Horton, P. and Saunders, J., 2012. The ‘East Asian’ Olympic Games: what of sustainable legacies? The International Journal of the History of Sport, 29 (6), 887–911. doi:10.1080/09523367.2011.617587

- House of Lords, 2015. The economics of high-speed 2. London: HL Economic Affairs Committee. Available from: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201415/ldselect/ldeconaf/134/134.pdf [Accessed June 2016].

- IOC, 2015a. Factsheet: Sochi 2014 facts and figures, update - February 2015. Lausanne: International Olympic Committee (IOC). Available from: https://stillmed.olympic.org/Documents/Games_Sochi_2014/Sochi_2014_Facts_and_Figures.pdf [Accessed June 2016].

- IOC. 26 Feb 2015b. IOC Executive Board meeting kicks off with report on Sochi 2014 operational profit. Available from: https://www.olympic.org/news/ioc-executive-board-meeting-kicks-off-with-report-on-sochi-2014-operational-profit

- Khimshiashvili, P. and Biryukova, L., 7 Feb 2014. Tretya stolitsa Putina [Putin’s third capital city]. Vedomosti. Available from: www.vedomosti.ru/newspaper/articles/2014/02/07/tretya-stolica-putina.

- Kinossian, N., 2013. Stuck in transition: russian regional planning policy between spatial polarization and equalization. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 54 (5–6), 611–629.

- Kinossian, N., 2016. Re-colonising the Arctic: the preparation of spatial planning policy in Murmansk Oblast’, Russia. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. doi:10.1177/0263774X16648331

- Kinossian, N. and Morgan, K., 2014. Development by Decree: the limits of ‘authoritarian modernization’ in the Russian federation. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38 (5), 1678–1696. doi:10.1111/ijur.2014.38.issue-5

- Koshik, A., 5 Feb 2015. “Vse eto delalos’ ne dlya sochintsev” [“This all was done not for people”. Gazeta.ru. Available from: www.gazeta.ru/social/2015/02/04/6399989.shtml

- Kuznetsova, O.V., 2015. Regionalnaya Politika Rossii: 20 Let Reform i Novye Vozmozhnosti [Russia’s regional policy: 20 years of reforms and new opportunities]. Moscow: URSS.

- Makarychev, A. and Yatsyk, A., 2014. The four pillars of Russia’s power narrative. The International Spectator: Italian Journal of International Affairs, 49 (4), 62–75. doi:10.1080/03932729.2014.954185

- McCann, E., 2013. Policy boosterism, policy mobilities, and the extrospective city. Urban Geography, 34 (1), 5–29. doi:10.1080/02723638.2013.778627

- Medvedev, D., 10 Sep 2009. Rossiya, Vpered! [Go Russia!]. gazeta.ru. Available from: http://www.gazeta.ru/comments/2009/09/10_a_3258568.shtml

- Medvedev, D., 2011. Excerpts from opening address by Dmitry Medvedev to the World Economic Forum in Davos’, President of Russia. Available from: http://en.kremlin.ru/misc/10663

- Miller, N., 2 Mar 2014. Crimea move makes Sochi look like $50 billion in wasted PR for Russia. The Sydney Morning Herrald. Available from: http://www.smh.com.au/world/crimea-move-makes-sochi-look-like-50-billion-in-wasted-pr-for-russia-20140302-hvfrt.html

- Müller, M., 2011. State Dirigisme in Megaprojects: governing the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. Environment and Planning A, 43 (9), 2091–2108. doi:10.1068/a43284

- Müller, M., 2014a. After sochi 2014: costs and impacts of russia’s olympic games. Eurasian geography and economics, 55 (6), 628–655. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2015.1040432

- Müller, M., 2014b. Introduction: winter olympics sochi 2014: what is at stake?. East european politics, 30 (2): 153-157. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2014.880694

- Müller, M. and Pickles, J., 2015. Global games, local rules: mega-events in the post-socialist world. European Urban and Regional Studies, 22 (2), 121–127. doi:10.1177/0969776414560866

- Nye, J.S., 2005. Soft power: the means to success in world politics. New York: PublicAffairs.

- Nye, J.S., 12 Dec 2014. Putin’s rules of attraction. Project Syndicate. Available from: www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/putin-soft-power-declining-by-joseph-s–nye-2014-12. [Accessed June 2016].

- Olimpstroy, 2014. Forma 14: otchet ob osuschestvlenii stroitelstva olimpiyskikh obyektov i vypolnenii inykh meropriyatiy, svyazannykh so stroitelstvom olimpiyskikh obyektov za 2013 god [Form 14: report on the implementation of Olympic construction and other related activities for the year 2013]. Sochi: Olympstroy.

- Persson, E. and Petersson, B., 2014. Political mythmaking and the 2014 winter Olympics in Sochi: olympism and the Russian great power myth. East European Politics, 30 (2), 192–209. doi:10.1080/21599165.2013.877712

- Petersson, B., Vamling, K., and Yatsyk, A., 2015. ‘When the party is over: developments in Sochi and Russia after the Olympics 2014ʹ. Sport in Society, 1–6. doi:10.1080/17430437.2015.1100888.

- RBC, 4 Feb 2013. Stoimost’ Olimpiady v Sochi perevalila za 1.5 trln rub. [The cost of the Olympics in Sochi has gone over 1.5 trillion roubles]. RBC. Available from: http://top.rbc.ru/economics/04/02/2013/843458.shtml

- RF Government, 2006. Decree from 08.06.2006 N357 on the federal target programme “The development of the City of Sochi as a mountain climate resort (in 2006–2014)”. Moscow: Government of the Russian Federation.

- RF Government, 2013a. Appendix N2, the decree of the government of the Russian Federation from 29.12.2007 N 991 (as revised by the Government Decree from 21.12.2013 N 1208). Moscow: Government of the Russian Federation.

- RF Government., 2013b. Decree of the Government of Russian Federation N1090-р from 05.08. 2009,amended 17.12.2013. Moscow: Government of the Russian Federation.

- RF Government. 2016. Regionalnoye razvitiye [Regional development]’, Government of the Russian Federation. Available from: http://government.ru/govworks/section/1521/ [Accessed June 2016]

- ROC. 2013. Informatsionnyi sportivnyi Bulleten OKR za 30 sentyabrya 2013 golda [Information sport bulletin of ROC from 30.09.2013]: russian Olympic Committee (ROC). Available from: www.olympic.ru/news/digest/informaczionniy-sportivniy-byulleten-30-09-13/ [Accessed June 2016].

- Rozhkov, A., 23 Oct 2014a. Dmitriy Chernyshenko: olimpiada v Sochi ne byla samoy dorogoy [Dmitry Chernyshenko: the Sochi Olympics wasn’t the most expensive]. Vedomosti. Available from: http://www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2014/10/23/dmitrij-chernyshenko-olimpiada-v-sochi-ne-byla-samoj-dorogoj

- Rozhkov, A., 7 Apr 2014b. Orgkomitet ‘Sochi-2014ʹ zarabotal 5 mlrd rubley [The Organising Committee Sochi 2014 made the profit of 5 billion roubles]. Vedomosti. Available from: http://www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2014/04/07/chernyshenko

- RPORC., 2015. Olimpiada v Sochi: god spustya [Olympics in Sochi: one year after]. Russian Public Opinion Research Center (RPORC). Available from: http://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=115138

- RSN. 7 Feb 2016. Mer Pokhomor: sochi v 2015 godu posetili 6 millionov turistov [Mayor Pakhomov: sochi was visited by 6 million tourists in 2015]. Available from: http://rusnovosti.ru/posts/407955

- Salukvadze, J. and Golubchikov, O., 2016. City as a geopolitics: tbilisi, Georgia — A globalizing metropolis in a turbulent region. Cities, 52, 39–54. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.013

- Satarov, G.A., ed., 2004. Regionalnaya Politika Rossii: adaptatsiya k Raznoobraziyu [Russia’s regional policy: adaptation to diversity]. Moscow: Fond INDEM.

- Tovkaylo, M., 31 Jan 2011. Skolko stoit bezopasnost Olimpiady [How much is Olympic security]. Vedomosti. Available from: http://www.vedomosti.ru/lifestyle/articles/2011/01/31/cena_spokojstviya

- Tovkaylo, M., 27 Dec 2013. Sostyazanie za 1.5 trln [Competition for R1.5 trillion]. Vedomosti. Available from: http://www.vedomosti.ru/newspaper/articles/2013/12/27/sostyazanie-za-15-trln

- Trubina, E., 2014. Mega-events in the context of capitalist modernity: the case of 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 55 (6), 610–627. doi:10.1080/15387216.2015.1037780

- Vorobyev, A., 29 Apr 2015. Sochi stal vtorym po populyarnosti gornolyzhnym kurortom v Rossii [Sochi has become the second most popular mountain ski resort in Russia]. Vedomosti. Available from: www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2015/04/29/sochi-stal-vtorim-po-populyarnosti-gornolizhnim-kurortom-v-rossii

- Wolfe, S.D., 2015. ‘A silver medal project: the partial success of Russia’s soft power in Sochi 2014ʹ. Annals of Leisure Research, 1–16. doi:10.1080/11745398.2015.1122534.

- World Bank, 2016. Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average). Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.FCRF [Accessed October 2016].

- Yaffa, J., 2 Jan 2014. The waste and corruption of Vladimir Putin’s 2014 winter Olympics. Bloomberg Businessweek. Available from: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-01-02/the-2014-winter-olympics-in-sochi-cost-51-billion

- Zakharova, N., 22 May 2011. Igor Yaroshevskiy: krasnaya Polyana. Arkhitektura Sochi. Available from: [http://arch-sochi.ru/2011/05/igor-yaroshevskiy-krasnaya-polyana/] [Accessed June 2016]