ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to review the development of national sport policy in Vanuatu. The paper provides a brief synopsis of the development of national sport policy in Vanuatu and outlines the government’s administrative system for implementing sport policy. It provides an analysis of government policies and objectives for sport and the nature and extent of government supported sport programmes that are focused on (1) sport for development (social development through sport); (2) junior sport development (development of sport to encourage young people to participate in regular physical activities); and (3) elite sports development. This paper highlights the dependence on foreign aid within these wide-ranging government sport policies, and questions the effectiveness of specific elements of Vanuatu sport policy, whether the processes that policymakers adopt are adequate, whether the right community of stakeholders are consulted about sport policy, and whether the development programmes from First World actually construct local ownership. While the last decade has seen considerable changes in the ways in which Vanuatu sport has been governed, developed, and funded, there remain considerable challenges for the ongoing effectiveness of sport policy interventions in this country.

The purpose of this paper is to review the development of national sport policy in Vanuatu, a small island developing nation that has not yet been subject to a substantial amount of independent research or analysis of its sport policies. While there has been a growing number of studies published in recent times of sport policy development and implementation in small nation states such as Chile (Bravo and Silva Citation2014), Cameroon (Clarke and Ojo Citation2016), Lebanon (Nassif and Amara Citation2015), and Hong Kong (Zheng Citation2016), small Pacific nations that are largely reliant on foreign aid for sport programme support have not been examined in any detail and provide a new context for the examination of the processes, challenges, and impacts associated with national sport policy.

The structure of the paper follows the guidelines provided by this journal for the development of country profiles. The paper provides a brief synopsis of the development of national sport policy in Vanuatu and outlines the government’s administrative system for implementing sport policy. It provides an analysis of government policies and objectives for sport and the nature and extent of government supported sport programmes. This paper describes the nature of the intersection of sport policy with the non-government sectors and external funding of sport in Vanuatu, discusses the dependence on foreign aid of sport within wide-ranging government policies, and identifies a number of continuing and emerging sport policy issues associated with the sport system in Vanuatu.

Sport policy in Vanuatu

The Republic of Vanuatu, formerly known as the New Hebrides, is a South Pacific island nation that is approximately 2500 km to the north-east of Sydney, Australia, 2000 km north of Auckland, New Zealand and 800 km west of Fiji. It consists of more than 80 populated islands and about 235,000 people (Vanuatu National Statistics Office Citation2009) of which the vast majority are Melanesians; Chinese, and Europeans are the other major ethnic groups. It is estimated that there are over 100 local languages spoken throughout the islands and people maintain a robust attachment with their respective island of origin. These ethnic differences are often still a barrier to national unity and can generate conflicts that lead to administrative inefficiency (see for example Early Citation1999). Vanuatu has been ranked as a UN ‘Least Developed Country’ since 1995. Vanuatu’s economy is small and based mainly on the agricultural sector, tourism, and foreign aid, with the majority of the country’s work force classified primarily as subsistence agriculturalists; per capita gross domestic production estimated to be US$2620 in 2012 (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat Citation2012). Economic development in Vanuatu is hindered by a small domestic market, geographical fragmentation, and the difficulty of attracting international investment because of a lack of transport infrastructure. Shortages of skilled labour, political instability, and frequent natural disasters such as cyclones and earthquakes also have an impact on Vanuatu’s economic development. While most of the population remains rural, there is a large migration of people from rural to the two urban areas of Port Vila (2009 population 44,040), on the island of Efate, and Luganville (2009 population 13,167) on the island of Espiritu Santo (Vanuatu National Statistics Office Citation2009).

Physical activities such as walking and gardening are part of daily life for Ni-Vanuatu (people of Melanesian background originating from Vanuatu) because most of the population remains rural, engaged in subsistence agriculture. Sport is a major leisure activity for children and adolescents in Vanuatu, but while there is a general enthusiasm for many sports in Vanuatu there are relatively few opportunities for participation in organised sport competitions. People mostly play self-organised games around the streets and empty lots of their neighbourhood rather than being part of clubs with scheduled training sessions. The limited budgets, expertise, and resources that are available for sport are skewed towards men’s sport and are concentrated primarily within Port Vila. Soccer is the most popular and well-organised sport in Vanuatu; the Vanuatu Football Federation has six provincial leagues and the two municipal leagues (Port Vila Football League and Santo Luganville Football League). Other prominent sports include volleyball, basketball, and netball.

Most of the administration work within the Vanuatu sport leagues is carried out by volunteers and most of the leagues struggle to secure adequate funds and volunteer labour to cover essential services, including scheduling training sessions, competitions, and coaching. The situation is exacerbated on the outer islands, where there are fewer sports played and there is less knowledge of rules, regulations, and administration requirements. In rural areas, where there are even less funds, adequate coaching, administration expertise, and affordable transport, organised sport participation is extremely scarce, delivered on an ad hoc basis and generally only available in provincial centres.

The Vanuatu National Games, which started in 1982 as the ‘Inter District Games’, is a nationwide sport event, but has limited participation from the rural population. The Games are held in order to encourage sports at the grassroots level, identify sporting talent for further development, and to unite the people and culture of Vanuatu. The first Inter District Games was held in Port Vila, the second in Santo Island in 1984, the third in 1986 in Tanna Island and the fourth was held in Ambae Island in 1988. After the last Inter District Games was held in 1988, the Games faced greater difficulty in securing political and economic support due to a general downturn in the nation’s economic performance. In 1997, they were revived under the name of the ‘Provincial Games’. In the first Provincial Games, which were held in Luganville in the SANMA province, over 800 athletes participated in 8 events (athletics, basketball, boxing, football, handball, netball, petanque, and volleyball). The 6th Games were held in Port Vila in 2009 and officially named the ‘Vanuatu National Games’ or simply ‘Vanuatu Games’.

After political independence, Vanuatu has participated in a number of international sports events, including the Commonwealth Games since the 1982 iteration in Brisbane, Australia. The number of athletes who have represented Vanuatu at the Commonwealth Games from 1982 to 2014 is 48 and they have participated in 6 events (athletics, weightlifting, boxing, cycling road race, table tennis, and judo), while 24 athletes have participated in 4 events (athletics, boxing, table tennis, and judo) at the Olympic Games from 1988 to 2016. While participation in the Commonwealth and Olympic Games has been relatively limited, there has been significant participation in the Pacific Games and Pacific Mini Games. The Pacific Games (formerly known as the South Pacific Games) is a multisport event, for which participants are drawn exclusively from countries that form the Pacific islands. The Pacific Games were first held in 1963 as the ‘South Pacific Games’ in Fiji and then approximately every 3 years until 1971 when they shifted to a 4-year cycle to eliminate overlap with summer Olympic Games. The 2011 Games in New Caledonia were renamed as the ‘Pacific Games’, in order to better reflect the inclusion of participants from the Northern Pacific. A central aim of the Pacific Games is to promote a unique and friendly high-quality competition, to develop sport for the benefit of the people, the nations, and the territories of the Pacific Community (Pacific Games Council Citation2006:3). The Pacific Mini Games, previously the South Pacific Mini Games, is also a multisport event which has been staged since 1981; it is a scaled-down version of the main Pacific Games, which enables smaller nations to compete against one another.

Government involvement in sport

At the national level, the Youth and Sports Secretary was created in 1984, which was located within the Prime Minister’s office. Its responsibility was widened to the department of Youth and Sports, Ministry of Internal affairs in 1991, and moved to the Ministry of Education under the Assistant Ministry of Youth and Sports in late 1997. When the Comprehensive Reform Programme (CRP) was initiated by the government in 1997, to address ailing government systems and introduce improved development planning and economic management, a wide range of structural reforms were undertaken, including reducing the number of ministries from 28 to 9, reducing the size of the public service and other associated initiatives. Through the CRP, sport lost its departmental profile – a division of Youth and Sports was created, which was located within the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports. Since 2000 a newly named department of Youth and Sports has been located within the Ministry of Youth Development and Training, which is responsible for youth development and sport in schools, as well as broader sport development. The mandates of the Ministry of Youth Development and Training are to improve options for young people, to facilitate and coordinate an expansion of rural training, and to foster cooperation with Non-Government Organisations (Government of the Republic of Vanuatu. Citation2004: 2). The activities of the Youth and Sports department reflect these broader youth development priorities. The allocation of departments and ministries responsible for sport since 1984 is illustrated in that shows that at various times throughout Vanuatu history the sport portfolio has been linked to education and youth development, including vocational training. The Ministry of Education, Youth Development, Sport and Training Corporate Plan 2013–2015 has the three major policy objectives: (1) youth development is prioritised and integrated into mainstream government policies and programmes; (2) the capacities of internal and external key youth development, sport and training institutions are strengthened, services integrated and better coordinated; and (3) strengthen the capacities of young people to participate in nation-building (Government of the Republic of Vanuatu Citation2012b: 5).

Table 1. Departments and Ministries responsible for Vanuatu sport policy 1984–2011.

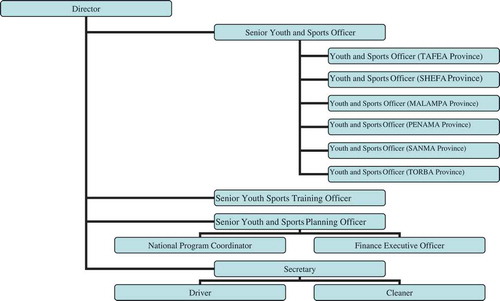

shows the structure of the Youth and Sports Division within the Ministry. The staff employed within the Division cover a variety of areas, including supporting all sport such as encouragement of sports through improvement of facilities and equipment at community, provincial, and national level, coordination of sport programmes induced by IF and external donor agencies, supporting National competitions and National Teams to international competitions, providing assistance in order to encourage sports in schools, driving policy, and managing facilities. The division has difficulty finding qualified people to contribute to the delivering services, especially in rural areas.

Figure 1. Structure of the Youth and Sports Division.

Source: Based on interviews with divisional staff members and internal documents made available within the Department of Youth and Sports.

There are also financial management problems such as a lack of transparency and some capacity issues in the provinces. As an Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) report has pointed out, accounting officers in the government are in a weak position to resist pressures from politicians and senior staff to spend money on purposes not included in the approved budget (Australian Government and AusAID Citation2009:13). indicates notable government funding for sports from 2005 to 2014.

Table 2. Vanuatu Government Budget and Ministries responsible for sport policy Budget (Vatu).

While sport is a relatively low priority within the Vanuatu government compared to other areas of public policy, there is increasing interest in ‘sport for development’ which contributes to specific development objectives, in particular the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The Australian Sports Outreach Programme (ASOP) has been operating since 2006 and is a sport for development programme aimed at using sport for building the capacity of partners to plan and conduct quality sport-based activities that address locally identified development priorities (AustralianAID Citation2013: 3). The Australian Government, through AusAID, had committed $5 million over 5 years (until July 2011) to the roll out of the ASOP across the Pacific region (Australia Government and AusAID Citation2008: 21). Between 2011 and 2014 the Vanuatu government received AUD$932,000 through the ASOP.

The Vanuatu National Sports Council was officially legislated by the national government in 1989 as the statutory body responsible for managing national sports facilities; it was originally established by the government to manage the national sport facilities built for the 1993 South Pacific Mini Games, which were held in Port Vila. According to the Vanuatu National Sports Council Act (Vanuatu National Sports Council Citation1989), the Council was endowed with a centralised power, in order to: (1) foster and promote the development of amateur sport and recreation in Vanuatu; (2) foster, support, and undertake the provision of facilities for sport and recreation; (3) promote the utilisation of sporting and recreation facilities in Vanuatu; (4) investigate developments in sport and recreation and disseminate knowledge and information about such developments; and (5) advise the Minister on any matters relating to sport and recreation. It should be noted, however, that the Council has a very small-scale operating budget and management of national sports facilities is complex and difficult. The considerable shortage of government funding for sport infrastructure development and the inability of sports organisations to maintain sports facilities often results in International Sport Federations providing funds for facility maintenance and operation. The Vanuatu government corporates with the Vanuatu Association of Sports and National Olympic Committee (VASANOC) to liaise with international donor agencies. From the middle of 2014, the Council became the ‘National Sports Commission’, charged with instituting a clear and manageable framework to guide and enhance the delivery of sports programmes in Vanuatu through a coordinated and partnership approach at all levels of participation (Republic of Vanuatu Citation2014: 4).

Non-government sectors of sport

The VASANOC, formerly known as the Vanuatu Amateur Sports and National Olympic Committee, is the official umbrella organisation for all national sports federations in the county. VASANOC is the result of a merger of two bodies – the Vanuatu National Olympic Committee (formed and joined the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1987) and the Vanuatu Amateur Sport Federation (formed in 1981 under the Ministry of Social Affairs). VASANOC aims to support sport development at all levels and throughout the country, and is composed of nine executives (board members) and four paid staff (Vanuatu Sports Association and National Olympic Committee Citation20131). However, due to its limited capacity to deliver services, current initiatives are mainly focused within Port Vila and at the elite level. shows the contribution of various sources to total VASANOC revenue in 2010, which in turn highlights that VASANOC is inordinately dependent on external funds.

Table 3. Source of VASANOC revenue (Vanuatu Sports Association and National Olympic Committee Citation2010).

VASANOC recognises 22 National Sport Organisations (NSOs): archery, athletics, basketball, badminton, boxing, cricket, football, golf, hockey, handball, judo, netball, rowing, rugby, sailing, squash, table tennis, taekwondo, Tennis, vandisport (the National Paralympics Committee of Vanuatu), volleyball (including beach volleyball), and weightlifting. Many of these NSOs have a very limited administrative structure, professional staff, significant volunteer systems or what would be considered sufficient organisational capacity to deliver a robust sport development pathway in comparison to their counterparts in western club-based community sport systems such as Australia, New Zealand, or the UK. Of these NSOs, eight do not have any clubs affiliated to their organisation, three have between 20 and 30 clubs affiliated and only 1 NSO (football) have more than 300 clubs affiliated (Vanuatu Sports Association and National Olympic Committee Citation2010 4). The nature of NSO operations also varies enormously; for example, 18 of the 22 NSOs are affiliated to their respective international federation; 18 organise regular in-country competitions; only 10 organise a national training squad for seniors and juniors. Most NSOs have low annual revenues and as a result have struggled to establish an effective governance, management, or development structure for their sports. A 2010 NSO survey by VASANOC (Citation2010) found that sports such as football, basketball, and tennis were more developed and had the capacity to conduct activities and projects using their own human and financial resources and were not as excessively dependent on external assistance or financial aid.

Key government policies and objectives for sport

The first attempt to articulate elements of a sport development policy was specifically referenced in the Ministry of Youth Development and Training’s Corporate Plan for 2004–2006. In the plan, sport and recreation were recognised as vital tools for teaching valuable skills such as teamwork, discipline, leadership, fair-play, and communication, in addition to the provision of positive activities and keeping young people fit, healthy, and positive (Government of the Republic of Vanuatu. Citation2004: 12). The Corporate Plan had four objectives in sport and recreation: (1) promote participation in sport activities among young people; (2) promote participation in recreational activities among young people; (3) increase participation to sport and recreation activities for under-represented groups of young people including the disabled, women and those living in remote areas; and (4) improve the management and operations of sporting organisations, facilities, and resources (Government of the Republic of Vanuatu. Citation2004: 12–15).

In 2006, the Ministry completed the implementation of its 2004–2006 Corporate Plan, and took the opportunity to create a first national sport policy; it was hoped through this national sport policy that more Ni-Vanuatu would be able to participate in the benefits of sport and recreation. In the process of developing the policy, an inaugural national sports forum titled ‘Re-thinking sport as a tool for the development of Vanuatu’ was conducted by the Ministry. The Vanuatu government contracted McLaughlin Sports Consultancy from Australia to assist in the planning and facilitation of the Forum and assembled relevant stakeholders in sport to identify the current situation and the future role that sport might play in the development of Vanuatu. The objectives of the Forum were to: (1) strengthen the network between key stakeholders; (2) review the National Games Charter and Games Council structure; (3) explore the opportunities to recognise Physical Education as a core subject in schools; and (4) explore the opportunities to develop a Vanuatu National Sports Policy and make recommendations regarding its purpose and content (McLaughlin Citation2006: 4). Based on information provided by all stakeholders and the input of McLaughlin Sports Consultancy, some key findings of sport development were identified as follows (McLaughlin Citation2006: 5–6):

No proper guidelines to research /monitor youth and sports activities.

No budget and accounts records (Officer) and no registration of assets at various levels.

Lack of reporting to the Minister from statutory bodies.

Lack of consultation between government and statutory bodies in policy formulation.

Lack of sports development in rural areas and a lack of youth and sports officers in the provinces.

Poor sporting facilities and lack of community commitment in managing sports facilities.

Lack of human resources/technical people as a result of insufficient funding to federations.

In 2007, the Ministry of Youth Development and Training released its first general policy directive titled ‘National Physical Activity Development General Policy Directives 2007–2011: Key Policy Areas and 5 Years National Physical Activity Development Targets’, in which it noted that ‘this policy promotes physical activity development for all as an essential tool for economic and social developments in Vanuatu through facilitation of programmes that promote social cohesion, team work, good health and employability’ (Ministry of Youth Development Sports and Training Citation2007: 6). The policy document established four key policy areas and objectives: (1) carry out an assessment and mapping of sports development resources in the country; (2) undergo re-structuring, resourcing, and capacity development of the Ministry; (3) continue to build and develop partnership and collaboration with other national and international sports partners; and (4) review, develop, and facilitate implementation of specific policies relating to promoting and protecting ‘right’ of equal access and participation in physical activities, healthy and safe environment (Ministry of Youth Development Sports and Training Citation2007: 15–18). Driven by the need for these issues to be addressed, the government has prioritised sport as a significant activity that contribute to national development, in particular as a way of promoting good health, bringing young people together and diverting them from antisocial and high-risk behaviours.

Key sport programmes currently in place in Vanuatu

One of the key sport programmes, Pikinini Plei Plei (junior sports development programme), was established in 1996. The programme provides opportunities for children to participate in a wide range of sports and activities focused on fundamental movement skills. It also provides a fun and interactive way for children to develop their social and sporting skills. The aim of the programme is to develop and implement a National Junior Sport Programme that provides accessible, quality sport physical activity opportunities for children aged 6–12 in urban and remote areas of Vanuatu. Pikinini Plei Plei was run and administered through the Ministry during 1996–1998 but failed to achieve much success due to limited funding, poor management, and lack of human resources.

In late 2003 and early 2004 the Australian Sports Commission (ASC) conducted a Pacific Sporting Needs Assessment report, by, which was the first-ever comprehensive assessment of the sporting landscape across the Pacific area and provided a sound game plan for all those interested in promoting sport in the region. This report suggested that there was a need to establish a more extensive school sport system in Vanuatu, including reviving the Pikinini Plei Plei Junior Sport Program and its reintegration into the national education curriculum, along with establishing physical education as a core subject (Australian Government et al Citation2004: 91). As a result, VASANOC took the initiative to revive the Pikinini Plei Plei program in 2005. The relaunching of the programme was also one way in which VASANOC chose to celebrate the United Nation’s International Year of Sport and Physical Education. One of the key components of junior sports development was the decision by the Vanuatu government to make it compulsory for all students to take Physical Education lessons in primary and secondary schools. The Physical Education syllabus as a core subject at primary school is currently developing in order to encourage children to participate in regular and varied physical activities and to develop effective social skills to manage their own lives confidently. (Ministry of Education Curriculum Development Unit Citation2013: 259).

VASANOC operates several additional development programmes, the operations of which are fully funded by grants from the IOC, the Oceania National Olympic Committees (ONOC) and other donor agencies. These notable sports development programmes include: (1) The National Olympic Development Squads Project, which is VASANOC’s Elite Sports Programme, required in order to qualify Vanuatu athletes for the Olympic Games; (2) The Vanuatu Talent Identification Program, which is to assist the VASANOC to discover young athletes who show a particular sporting talent; and (3) The Oceania Sport Education Programme, which is committed to producing competent and world-class athletes, coaches, and officials in the Pacific through continuous improvement of its sport education resources (Oceania Sports Education Program, Citation2009: 6).

After the government produced its first sport policy, in early 2008 the ‘Nabanga Sports’ programme was officially launched in Port Vila by the Ministry, VASANOC, and Internal Affairs, the three-party partnership that forms the programme’s steering committee. Nabanga Sports was a ‘sport for development’ programme established via a partnership of a broad group of stakeholders and the first time that a sport programme had deliberately been implemented in rural communities in Vanuatu’s provinces (PENAMA province and TAFEA province). ‘Nabanga’ is the word for the iconic Banyan tree in Bislama (the lingua franca of Vanuatu), which represents a traditional meeting place for community discussion. The central objective of the sport programme that shares its name is building the capacity of a community’s youth to plan and run quality sport activities for children and youth. The programme design document claimed that ‘in rural provinces, sport is usually just an irregular recreational activity, usually reserved for teenage boys and young men or for occasional community festivals’ (Australian Government et al. Citation2007:4). The programme activities were expected to contribute towards five outputs: (1) community education/awareness programme delivered; (2) sport leader apprenticeship programme established; (3) youth trained and supported as community sport leaders; (4) support provided to community, ward, and provincial councils to enable them to effectively monitor and manage the programme; and (5) support provided to individuals and organisations to enable them to monitor and manage the programme effectively (Australian Government et al. Citation2007:5). The success of the programme was to result in organised physical activity becoming a prioritised, regular, and sustained part of community life that contributed to social development. The programme defined social development as healthy lifestyles and fitness, leadership, youth education/skill development. The programme was therefore designed to achieve these benefits. The Nabanga programme is part of the Australian government’s ASOP, which is managed via collaboration between the ASC and the AusAID. Total Australian aid to this 4-year Nabanga sports programme was estimated at AUD$1,233,488 (Australian Government et al. Citation2007: 44).

In summary, there are three major strands of Vanuatu sport policy: (1) sport for development (social development through sport); (2) junior sport development (development of sport to encourage young people to participate in regular physical activities); and (3) elite sports development. Sport policy is largely implemented through the Ministry and VASANOC, while external donor agencies provide significant financial and human resources to assist in improving of Vanuatu sport development. In particular, the Vanuatu government has acknowledged Australia as a key resource and ally for sports development and its assistance in the provision of equitable sports opportunities for the previously disadvantaged youth and in providing a broad base that may feed into elite participation. National government policies in sport are typically delivered through dedicated departments of sport and youth development and are focused on ‘sport for development’, supporting the delivery of community-based sport. Provincial governments across Vanuatu rely heavily on the aid from the central government or external donor agencies, while local organisations struggle to develop the capacity in order to support sport-related community activities.

Matching up programmes with the policy objectives

As discussed above, external agencies such as the Australian government and IOC have been funding sport development programmes in Vanuatu for more than a decade and are currently working with the Ministry and VASANOC. This aid has contributed to sport development at both the elite and grassroots level in Vanuatu. These programmes which are well prepared and organised help to augment the fragmented sport development system in Vanuatu. However, the governance, management, and implementation systems are often deficient, which means that the allocation of aid in inconsistent with broader sport policy objectives. In other words, when too much aid is put too rapidly into a country with fragile administrative underpinnings and limited capacity, the outcomes may not be optimal. There are frequent restructuring of government ministries and agencies in Vanuatu making it difficult to deliver sustainable growth for sport.

Customary and informal institutions at local levels are viewed as legitimate and relevant to people’s lives. As many aid agencies have recognised, the chiefs and churches continue to play an important role in governance, law and order at the local level in Vanuatu (for example, see Cox et al, Citation2007, Howell and Hall Citation2010). By contrast, the provincial government is commonly seen as artificial and ineffective (Cox et al. Citation2007). The provincial governments are under resourced, which makes it thoroughly difficult to implement coherent development policy and challenging to deliver services outside the provincial headquarters.

In this social milieu, there are serious concerns with the Nabanga Sports Programme. According to the Nabanga programme midterm review, there appeared to be very low ownership of the programme by the Ministry, and very limited involvement by the Provincial Governments in PENAMA and TAFEA (Vira and Kenway Citation2009: 3). While the programme was very supportive of enhancing community-based sports that targeted rural areas, the capacity of the programme’s administration to provide services for rural communities was severely limited. The Review team identified several issues that required immediate attention before the programme could be expanded. First, there had been minimal engagement and oversight of the programme by the Ministry. Although housed under the broad umbrella of the Ministry, all of the main implementing staff, such as the National Coordinator, Assistant Provincial Coordinators, and Provincial Trainers, were not the Ministry staff. In fact, the Ministry and Nabanga Sport staff were generally not aware of or involved in each other’s activities. It appears that many of the strategic and operational decisions were made by the ASC, leading to a micromanagement approach. There also appeared to be reliance by the Ministry management and programme staff on the ASC to play this role. There was a clear need for the Ministry to play a stronger driving force and take ownership for the programme (Vira and Kenway Citation2009:10–11). Second, it was clear that provincial councils were not heavily involved in deciding how Nabanga Sports was to be implemented as most of the decisions and programming was perceived to be done largely at the national level. At a provincial level, Secretary Generals of both PENAMA and TAFEA provinces commented that they were aware of Nabanga Sports but had very little knowledge of what the programme was doing. The Senior Provincial Government staff in PENAMA also had little knowledge of what the programme was doing. As such, there appeared to be minimal ownership of the programme by the Provincial Governments (Vira and Kenway Citation2009:11–12). Third, the programme had not yet established strong community support and involvement. In some areas Chiefs had not been made aware of the programme, and their support and involvement had not been achieved. In the absence of those community supports, the programmes’ work had been more difficult, particularly for young women (Vira and Kenway Citation2009:12).

The same can be said of the junior sport programme (Pikinini Plei Plei) that addresses government interventions to strengthen sport operations across the country. While the junior sport development programme has not experienced the same degree of conflict, concerns have been raised about the stability of the programme. Government or external programmes have been put in place to facilitate the objectives, but in many cases most of participants in the programmes still have a dependence on the programme to supply equipment. Although statistics provided to the public did not provide them with sufficient data to analyse the impact positively on the increasing of sport involvement, it appeared that Pikinini Plei Plei has occurred more regularly when it has been linked with schools, and involved school teachers in its delivery (Vira and Kenway Citation2009:13).

A related issue emerged operating various types of programmes on elite sports development. The data on participating in a number of international sports events suggest that there is no question that some remarkable work on elite sports development programmes is being done by external donor agencies. However, policy initiatives at national and provincial level tend to be inconsistent and short-lived, which are sometimes regarded as being driven more by the needs of the donor than by the needs of the local people. For example, in 1998 and later, the Vanuatu government and VASANOC must prepare and send the national squad to participate an international convention (such as the Olympic Games, the Commonwealth Games, the Pacific Games, and the Pacific Mini Games) on a yearly basis. As Minikin, a manager of regional sports developments within the ONOC of the day, mentioned, the pressure to participate in these competitions on an annual basis may divert vital resources away from developing the infrastructure necessary to sustain such activities successfully (Minikin Citation2009:20). He also noted that this might lead sport organisations to adapt objectives or programme strategies that meet the criteria set by external agents rather than be guided by what is more appropriately required by the organisation itself (Minikin Citation2009:6).

More recently, the ASOP country programme has shifted focus specifically to improve health-related behaviours to reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases and to improve the quality life of people with disability. It is important note that these changes – from giving various activities to shaper focus towards promoting healthy behaviours among targeted populations and enhancing the lives of people with disability – are amplified in the Australian Government’s new aid policy titled An Effective Aid Program for Australia: Making a real difference was released in 2011. In the framework, the purpose of the aid programme is to promote Australia’s national interests by contributing to sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction, therefore those aid programmes will implement a ‘value-for-money’ framework, and measure their effectiveness, learn from experience and adjust or cancel programmes that are not achieving results (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2012). As a result, Vanuatu is currently addressing NCDs by using Nabanga to promote healthy behaviours, and also focus as narrowly as possible on objective evidence to review programme outcomes.

For example, Nabanga has provided significant opportunities of physical activity on Aniwa island, consequently improving health-related behaviours. According to the results conducted on the ASOP in Vanuatu, a high level of physical activity on Aniwa has been recorded and identified high levels of leisure time physical activity (82.6% of men and 89.9% of women); these levels were significantly higher than those recorded on the nearby island of Aneythium (77.3% of men and 70.7% of women), where the Nabanga is not active (AustralianAID Citation2013: 7). While evidence collected from the research activities to date indicate that sport is being used successfully as a tool to address these development priorities, it is important to situate this within the context of sport policy direction in Vanuatu and its relations with the largest grant donor’s aid policy.

Sports organisations in Vanuatu, particularly the VASANOC and its member federations, are heavily influenced by external agencies and are at risk of tackling development programmes that they do not have the capacity to implement but seek to do so because of the financial incentives. As a result, and not surprisingly in this context, sport development programmes often cease to operate after the period of external facilitation and funding.

The future for sport policy in Vanuatu

There are arguably four major emerging or continuing policy issues that will dominate Vanuatu sport policy in the short to medium term: (1) the continued push to increase participation in sport and recreation activities, particularly among under-represented groups of young people including the disabled, women and those living in remote areas; (2) the ongoing improvement of the management and operations of sporting organisations, facilities, and resources; (3) the ongoing relationship between sport governing bodies at national level and sport governing bodies at provincial level for the achievement of policy goals and the concomitant need to enhance the governance and management capacity of key stakeholders; and (4) the increasing desire of the government to look to sport for contributing to national development, especially as a way of promoting good health, bringing young people together and diverting them from antisocial and high-risk behaviours.

The government and VASANOC will continue to work on developing policy aimed at increasing sport involvement. Vanuatu’s Paralympic Committee was formed in 2003 in order to encourage people with disability at all levels of sports and the Vanuatu Women and Sports Commission was also re-established in 2009 in order to promote women and sports in Vanuatu. Female participation in sports is only evident in urban and suburban areas. In rural areas girls may be seen playing, but most women are engaged in household activities (Ministry of Youth Development Sports and Training Citation2007: 14). The continued delivery of sport for under-represented groups will require NSOs that engage in educational activities on the increasing participation to sport as well as raising awareness of these issues, and thus will led to equal opportunities for participation in all aspects.

The sport sector in Vanuatu continues to face a lack of coordination of services in the distribution and mobilisation of qualified sports officials at the national and provincial level, who are engaged to manage and coordinate physical activity developments. This has often resulted in internally skewed distribution of limited resources, which in turn leads to poor management of public sporting facilities and deactivation of programmes in rural areas. The current channels of financial and other in kind distribution between federations, VASANOC and the Ministry are unclear. Vanuatu sport policy will remain focused on monitoring evaluation mechanisms. Specifically there is a key need for the VASANOC and the Ministry to have closer links with NSOs and provincial sporting associations, therefore NSOs will continue to improve the management that has been lack of information sharing and cooperation leading to lack of potential support in the development of sports.

Much of the aid programmes that attempt to develop sport in Vanuatu are donor-defined. As Hayhurst (Citation2009) noted, it has been argued that development discourses, rhetoric of ‘partnerships’, and power relations underpinning the MDGs negatively impact aid distribution and misinform the basis for policy practices in Two-Thirds World countries (Amin Citation2006). There is a danger that international agencies will hide behind the rhetoric of ‘development for sport’ or ‘development through sport’, where sport has been used to further causes to transfer a ‘top-down’ power structure that might magnify asymmetrical North–South relations as argued by Hayhurst (Citation2009). This also could broaden the discussion to include major political concern about neocolonialism. According to Coalter (Citation2008), some academics such as Eichberg (Citation2008) have expressed concerns about the possible ‘neocolonialist’ nature of sport in many developing countries – concerns that certain traditional sports have been displaced and/or destroyed by the importation, or imposition, of ‘western’ sport and, more especially, its values. There appears to be broad agreement among international agencies that western sport-led attempts to develop sport in Two-Thirds World will have positive impact on local communities, therefore much of aid agency tends to ignore relationship of sport to forms of colonialism and neocolonialism. In order to understand the proposition that Vanuatu sport was once largely self-sufficient, but is now dependent on international aid from Australia, as well as international agencies and organisations, requires a more in-depth examination from diverse theoretical perspectives and standpoints.

In conclusion, there is an obvious need for research into the efficacy and impact of these development programmes within Two-Thirds World. There remain many unanswered questions about the effectiveness of specific elements of Vanuatu sport policy, whether the processes that policymakers adopt are adequate, whether the right community of stakeholders are consulted about sport policy, and whether the development programmes from First World actually construct local ownership. While the last decade has seen considerable changes in the ways in which Vanuatu sport has been governed, developed, and funded, there remain considerable challenges for the ongoing effectiveness of sport policy interventions in this country.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Amin, S., 2006. The millennium development goals: a critique from the South. Monthly review, 57(10), 1–10. doi:10.14452/MR-057-10-2006-03

- Australia Government and AusAID,2008. Focus: The magazine of Australia’s overseas aid program. 23(1), 20-22 June – September.

- Australian Government and AusAID, 2009. Working paper 3: Vanuatu Country Report Evaluation of Australian Aid to The Health Service Delivery in Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Australian Government et al, 2004. Pacific sporting needs assessment. Canberra: Australia Sport Commission.

- Australian Government et al., 2007. Vanuatu Sport for Development program 2007-2011 Design Document. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- AustralianAID, 2013. Australian Sport Outreach Program April 2013 submitted by Australian Sports, Canberra.

- Bravo, G. and Silva, J., 2014. Sport policy in Chile. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 6(1), 129–142. doi:10.1080/19406940.2013.806341

- Clarke, J. and Ojo, J.S., 2016. Sport policy in Cameroon. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 1–12. doi:10.1080/19406940.2015.1102757

- Coalter, F., 2008. A wider social role for sport: Who’s keeping the score?. London: Routledge.

- Commonwealth of Australia., 2012. An Effective Aid Program for Australia: Making a real difference – Delivering real results. Available from: http://aid.dfat.gov.au/Publications/Documents/AidReview-Response/effective-aid-program-for-australia.pdf (accessed 20 August 2014)

- Cox, M., et al., 2007. The unfinished state: Drivers of change in Vanuatu. Canberra: AusAID.

- Early, R., 1999. Double trouble, and three is a crowd: languages in education and official languages in Vanuatu. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 20(1), 13–33. doi:10.1080/01434639908666367

- Eichberg, H., 2008. From sport export to politics of recognition: experiences from the cooperation between Denmark and Tanzania. European Journal for Sport and Society, 5(1), 7–32. doi:10.1080/16138171.2008.11687806

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2005. Budget 2005 (Parliamentary Appropriation 2005). Port Vila: Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2006. Budget 2006 (Parliamentary Appropriation 2006).Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2007. Budget 2007 (Parliamentary Appropriation 2007).Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2008. Budget 2008 (Parliamentary Appropriation 2008).Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2009. Budget 2009 (Parliamentary Appropriation 2009).Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2010. Budget 2010 (Parliamentary Appropriation 2010).Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2011. Budget 2011(Parliamentary Appropriation 2011).Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2012a. Budget 2012(Parliamentary Appropriation 2012).Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2012b. Ministry of Education, Youth Development, Sports and Training cooperate Plan 2013-2015. Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2013. Budget 2013(Parliamentary Appropriation 2013).Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu, 2014. Budget 2014(Parliamentary Appropriation 2014).Port Vila:Government of the Republic of Vanuatu.

- Government of the Republic of Vanuatu., 2004. Ministry of youth development and training corporate plan 2004-2006. Port Vila: Department of Youth Development Sports and Training.

- Hayhurst, L., 2009. The power to shape policy: charting sport for development and peace policy discourses. International Journal of Sport Policy, 1(2), 203–227. doi:10.1080/19406940902950739

- Howell, J. and Hall, J., 2010. Evaluation of AusAID’s engagement with civil society in Vanuatu. Australia: AusAID.

- McLaughlin, M., 2006. National Sports Forum “Re-thinking sport as a tool for the development of Vanuatu”: Post forum findings and recommendations report. Canberra.

- Minikin, B., 2009. A question of readiness. MEMOS (Master Executif en Management des Organisations Sportives) XII – September 2008 – September 2009, Faculté des sciences du sport. France: Université de Poitiers.

- Ministry of Education Curriculum Development Unit, 2013. National Syllabus primary years 4-6. Port Vila: Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Youth Development Sports and Training, 2007. National Physical Activity Development General Policy Directives 2007-2011. Port Vila: Ministry of Youth Development Sports and Training.

- Nassif, N. and Amara, M., 2015. Sport, policy and politics in Lebanon. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7(3), 443–455. doi:10.1080/19406940.2014.914553

- Oceania Sport Education Program, 2009. OSEP Strategic Plan 2009-2012. Suva.

- Pacific Games Council, 2006. New Caledonia: Pacific Games Council Charter.

- Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2012. Pacific Regional MDGs Tracking Report. Suva.

- Republic of Vanuatu, 2014. Vanuatu National Sports Commission Act No.14 of 2014. Port Vila: Government of Vanuatu.

- Vanuatu National Sports Council, 1989. Vanuatu National Sports Council Act. Vanuatu: Government of Vanuatu.

- Vanuatu National Statistics Office, 2009. National Census of Population and Housing. Vanuatu: Vanuatu National Statistics Office. Port Vila: Ministry of Finance and Economic Management.

- Vanuatu Sports Association and National Olympic Committee, 2010. 2010 NF’s survey general report. Port Vila: VASANOC.

- Vanuatu Sports Association and National Olympic Committee, 2011. NOC Annual Review 2011. Port Vila: VASANOC.

- Vanuatu Sports Association and National Olympic Committee, 2013. Financial report for the year ended 31 December 2012.. Port Vila: VASANOC.

- Vira, H. and Kenway, J., 2009. Nabanga Sports Program Mid Term Review. Port Vila: Government of Vanuatu.

- Zheng, J., 2016. Hong Kong. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 8(2), 321–338. doi:10.1080/19406940.2015.1031813