ABSTRACT

This study investigates existing support services/systems that support junior dual career athletes in seven different countries. Specifically, the study aimed to identify: (1) What support services/systems are available for junior dual career athletes in the seven countries? and (2) Are there any similarities or differences between the seven countries? Between March 2020 and June 2020, desk-based data collection was conducted to identify any relevant evidence to answer the two research questions. Research teams from seven countries collected data from websites of sports organisations, sports clubs and schools to identify any structured support services/systems used to help junior athletes manage their dual careers. A deductive approach was applied to analyse the data. The seven countries identified between 10 and 36 organisational support services/systems which support junior athletes manage their dual career. Many of the sports organisations across the countries provided financial support via a small grant to cover equipment costs, travel expenses, and sport science and medicine support (e.g. physio and sport psychology support). Results indicated holistic support for junior athletes is lacking at the secondary school level. This study has both academic and practical implications. The findings extend the knowledge of organisational support for junior athletes aged between 15 and 19 years old and addresses a clear gap in both literature and practice. This study contributes to raising awareness of the need for customised support systems for junior dual career athletes and informs relevant authorised bodies of the need to develop evidence-based support schemes.

Introduction

Dual careers – when athletes combine sport and education or sport and work – can be beneficial for athletes, helping them to balance sport and non-sport commitments in preparation for ‘life after sport’ (Aquilina Citation2013, Lally Citation2007, Caprless and Douglas Citation2013, Henry Citation2013). The benefits of engaging in dual careers can include the development of employability skills, financial security, well-rounded identities, less life stress, a good social network and appropriate plans for retirement (Petitpas et al. Citation2009, Price et al. Citation2010, Tekavc et al. Citation2015, Torregrosa et al. Citation2015). However, researchers have identified that dual careers can also be challenging – athletes can experience challenges and barriers, such as time constraints, when balancing sport and education (Cosh and Tully Citation2015; Ryan et al. Citation2017).

While the challenges of being dual career athletes, and the importance of support to help them manage their dual careers, were highlighted in the literature, it was reported that research focusing on junior athletes is limited. In a very recent study, López-Flores et al. Citation2020a conducted a systematic review on dual careers of junior athletes to identify the challenges, available resources, and roles of social support providers. Based on their review of 26 peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2014 and 2020, they demonstrated that junior athletes also face challenges and barriers to balance two major commitments – sport and education – and support systems/services are needed to overcome such difficulties. However, it was also reported that studies focusing on junior athletes are still limited and there is a clear need to investigate support systems/services available to assist this group in coping with their dual careers (López-Flores et al. Citation2020a). Junior athletes in their study were defined as student-athletes aged between 15 and 19, who are in adolescence and/or young adulthood (Wylleman et al. Citation2013) and the current study used the same definition.

There are several reasons why this population is considered significant in terms of dual careers. These athletes are likely to be at risk of dropping out from sport; a failure to balance athletic and non-athletic careers may be one of the reasons for athletes ‘dropping out’ (Baron-Thiene and Alfermann Citation2015). In addition, during the 15–19-year-old timeframe, the target group of athletes may face the move from junior to senior sport, which is considered the most challenging transition athletes will face in their sporting careers (e.g. Pummell et al. Citation2008, Stambulova et al. Citation2012, Stambulova and Wylleman Citation2014.).

Additionally, the growing research interest in dual careers has been accelerated by the publication of EU guidelines on the topic (European Commission Citation2012). From 2013 to the present, ‘Dual careers of athletes’ was one of the key topics of the Erasmus + programme facilitated by the European Commission in consideration of its importance within sport setting (European Commission Citation2007, Citation2012). The Erasmus+ Sport has provided funding to 59 projects on the topic of dual careers of athletes (López-Flores et al. Citation2020a). As such, dual career of athletes now features on the agenda of European Union sports programmes, based on the EU Guidelines and numerous programmes implemented at the government and sport federation levels within the Member States. Nevertheless, only a small number of initiatives targeting junior athletes are being undertaken within 59 Erasmus+ projects.

Concerning support services/systems for dual career athletes, there has been support provision developed for dual careers athletes via research projects supported by European Commission such as Be a winner in elite sport and employment before and after athletic retirement (B-Wiser Consortium Citation2019) and Gold in Education and Elite Sport (GEES Consortium Citation2016, López-Flores Citation2020). Morris et al. (Citation2020), in their study, identified and classified the different types of dual career development environments, demonstrated some existing supporting bodies, programmes, and systems in seven different countries – Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. In the case of a senior level of athletes, there are more programmes and resources available. Hong and Coffee (Citation2018) investigated sports career transition organisational intervention programmes for high-performance athletes in 19 different countries across five different continents (Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania and South America) and provide an overview of available resources to manage their career and develop life skills. They identified that most of the countries in the study have established support programmes/services to assist athletes in balancing their sport and non-sport careers by providing educational, vocational, personal development, career development and life skills support services. It should be noted that such programmes are mainly provided to athletes who compete at international levels such as Olympics and World Championships. Therefore, eligible athletes that are primarily in their mid-20s+ and depending on their sport. However, research into structured support services and systems to assist junior athletes at secondary schools and high education institutions remains scarce.

Literature review

Dual career of athletes

The combining of sport and education or vocation, known as a dual career, is an effective way for athletes to deal with many stressors. Specifically, for example, dual careers can help athletes when coping with adversity (e.g. injury, loss of form, being dropped; Morris et al. Citation2016; Wylleman and Lavallee Citation2004, Morris et al. Citation2015, Torregrosa et al. Citation2015) and can help athletes in maintaining perspective on their current situation in their sport and life, particularly during stressful periods (Aquilina, Citation2013, Pink et al. Citation2015, Sorkkila et al. Citation2017, Morris et al. Citation2020). Undertaking a dual career can also be valuable in preparing athletes for retirement; athletes can undertake a dual career as a mechanism to plan ones’ future when preparing for retirement from sport (e.g. by engaging in academic study). Dual careers may help them to overcome some of the difficulties and maladaptive coping mechanisms they may use if they do not have a plan in place and suffer from identity foreclosure (e.g. such as poor mental health, difficult adjustment to life outside of their sport, and potential maladaptive behaviours, e.g. drug and alcohol abuse; Danish et al. Citation1993, Sorkkila et al. Citation2017).

Despite the potential benefits of undertaking a dual career, there are significant challenges that should not be underestimated by athletes and support staff when embarking on or supporting athletes undertaking dual careers. For instance, research (e.g. Wylleman and Lavallee Citation2004, Wylleman and Reints Citation2010, Stambulova and Ryba Citation2013) has indicated that balancing several life domains (e.g. sport, academic or vocational, private life) can be challenging as it means providing appropriate time and focus on relevant moments at relevant times. In this regard, dual careers can be characterised by large workloads across the various domains, set schedules that cannot be flexed, mandatory class attendance in academia, and a reluctance to allow for any alternative focus by coaches and athletes themselves (López de Subijana et al. Citation2015, Ryan Citation2015, Tshube and Feltz Citation2015). To balance these competing demands, dual career athletes need to have appropriate coping mechanisms and support in place.

Theoretical frameworks

To conceptualise the potential crossover of demands further, Wylleman and Lavallee (Citation2004) introduced the developmental model based on the findings from research on the development of athletes’ interpersonal relationships (Wylleman Citation2000, Wylleman et al. Citation2007), dual careers of elite student-athletes (Wylleman et al. Citation2004), and retired athletes (Wylleman et al. Citation1993). The lifespan model represents a holistic perspective of four different levels of athletes’ development: athletes’ athletic, psychological, psychosocial, and academic and vocational development. After about a decade, the Holistic Athlete Career (HAC) Model was introduced, which includes five different levels of athletes’ development: athletic, psychological, psychosocial, academic/vocational, and financial (Wylleman et al. Citation2013; see ). In the HAC, junior athletes aged between 15 and 19 year old are in the development stage in the athletic level. For dual career athletes, this development stage is depicted by increasing demands in both training and study. The significance of this age group is that athletes may also face the junior-to-senior transition, which is considered the most challenging within-career transition in an athletic career (Stambulova and Wylleman, Citation2019). Morris (Citation2013) remarked that young athletes undergoing the junior-to-senior transition can face challenges related not only to sporting domains but non-sporting ones (e.g. psychosocial development). Some athletes may also experience academic transitions from secondary school to higher education at the same time as the junior-to-senior transition (Pummell et al. Citation2008). Another challenge of junior-to-senior transition is that it may last for many years across athletes’ secondary school and higher education (Stambulova Citation2009). Therefore, the junior-to-senior transition is considered as one of the most challenging transitions throughout an athletic career (Drew et al. Citation2019) and many athletes are unsuccessful in managing the demands of sport and study as required (Vanden Auweele et al. Citation2004).

Figure 1. The Holistic Athlete Career (HAC) Model (Wylleman et al. Citation2013).

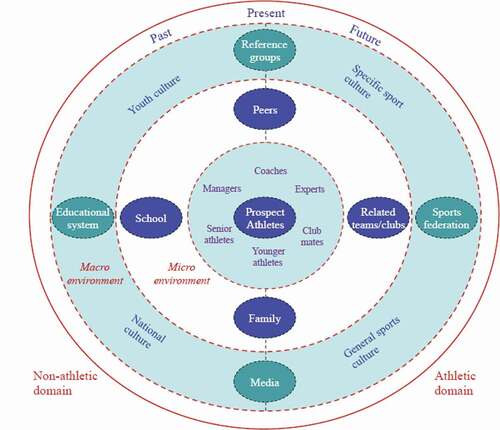

In addition to the HAC model, the dual career development environment (DCDE) working model (Henriksen et al. Citation2017; see ) was adopted to help understanding of support in different environments (e.g. at the macro, meso and micro levels). The purpose of the DCDE working model is to ‘describe a particular DCDE and clarify the roles and functions of the different components and relations within the environment’ (Henriksen et al. Citation2020). In the model, dual career athletes (student-athletes) are located in the centre; micro and macro environments include three key domains to be considered – Study, Sports and Private life (see ). The micro-level illustrates the environment where dual career athletes are directly involved and lead their daily life (e.g. study programmes, residence, teams/clubs/centres), and the macro-level indicates social settings around them, which influence their dual careers (e.g. educational system, sports system, local authority). The model also includes significant people who can influence dual career athletes such as peers, teachers, family and coaches/experts, which is similar to the HAC model (Wylleman et al. Citation2013).

Figure 2. The dual career development environment (DCDE) working model (Linnér et al. Citation2017).

Erasmus+ projects on dual career

In recent years, the Erasmus+ programme has prioritised dual career development, considering it of great importance to the improvement of the learning and education of athletes, with the aim of developing dual career athletes’ capacity outside of the sports environment (European Commission Citation2007, Citation2012). Therefore, the Education, Culture and Audiovisual Executive Agency has facilitated funding for 59 projects focused on dual career development since the beginning of the programme (López-Flores et al. Citation2020b). These projects have contributed to the development of guidelines for dual career implementation, raised awareness of the benefits and barriers of undertaking a dual career, and contributed to scientific research on the topic of dual careers. However, López-Flores et al. Citation2020a indicated that there have been a limited number of projects that focused on junior athletes. To advance the knowledge in the dual career area and expand upon previous ERASMUS+ projects, a project which focuses on junior dual career athletes, an under-research population, will help (López-Flores et al. Citation2020a, López-Flores Citation2020).

The primary purpose of the present study is, therefore, to identify existing support systems offered to junior athletes to better understand current practice within sport organisations, sports clubs and national governing bodies in different European countries. To understand the types of structured organisational support services on offer, the research questions were: (1) What support services/systems are available for junior dual career athletes in the seven countries? and (2) Are there any similarities or differences between the seven countries?

Methodology

The present study is part of a larger project, the ERASMUS + Sport project ‘Dual Career for Junior Athletes’ (DCJA), which aims to develop an online support system for both junior athletes (aged between 15 and 19) and their support providers, including coaches, teachers, parents, career assistance programme practitioners and sports psychologists. The consortium is comprised of partners from seven different countries – Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and the United Kingdom. Therefore, the study utilised a multiple-comparative case study that includes more than a single case and follows replication logic (Yin Citation2003). Multiple cases contribute to ‘maximize variation in the sample and ensure better opportunities for the comparison of findings’ (Sammut-Bonnici and McGee Citation2015, p. 1). The current study follows Yin’s (Citation2003) multiple-case study protocol with four different phases: (1) selecting multiple cases (Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and the United Kingdom); (2) collecting data; (3) analysing data and (4) doing a cross-case analysis.

Data collection

Desk-based data collection was conducted between March 2020 and June 2020 to identify support services/systems available for junior dual career athletes, and similarities or differences between the seven countries. To identify any structured support services and systems used to help junior athletes in managing their dual careers, data were collected from websites of sports organisations, youth sports clubs, and schools in seven countries – Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and the United Kingdom. To enable this to happen, the first author provided a blank template for completion (taken from Morris et al. Citation2020) and an example template of the case of the United Kingdom to the researchers from the consortium. Researchers then had two meetings to discuss the details of the template and address their concerns or any expected barriers. After these meetings, all researchers clearly understood the template and identified relevant websites to fill out the template based upon. The template asked the researchers to identify (1) the sport system (Centralised or Decentralised), (2) presence of sports school, (3) level/type of organisations (e.g. National governing bodies, Federations, Clubs, Charities, Foundations, Educational institutions [e.g. high schools, secondary schools, universities, colleagues, etc.]), (4) name of organisations, (5) name of support services/programmes, (6) type of support services/programmes (e.g. Athletic, Psychological, Psychosocial, Academic/Vocational and Financial level; some services/programmes might cover every level, one/two/three/four or none) and (7) eligibility (e.g. target age group). The data collection was conducted by the researchers in each country who are native to each language (English, Greek, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Slovenian and Spanish). Back-translation was applied to meet semantic equivalence and ensure the integrity of the data during the translation process (Chen and Boore Citation2010). No major differences were identified.

In total, there were 122 pages of data collected including additional information and notes from the researchers such as an explanation of organisations/programmes, links of websites and date of access to relevant websites. The authors provided all data in English for data analysis.

Data analysis

A deductive approach was used to analyse the data. Based on the deductive approach, initial codes are identified by the purpose of the study and research questions; therefore, the two study research questions and the theoretical framework of the dual career development environment (DCDE) working model (Linnér et al. Citation2017) served as a framework for analysis in this study (Azungah Citation2018). Data collected in different languages were translated into English by the researchers who collected the data and back-translation was conducted as mentioned above. All authors reviewed the English version of copies of all data and had a series of meetings to discuss the details of each country and decide what to present in a table based on the template provided to the researchers from the consortium. The data gathered by all authors were presented in a table using the template mentioned above; all authors respectively reviewed the details in the table and checked if there were missing any data. Finally, all authors then had a follow-up meeting to finalise the details in the table. The four authors in this paper all had a background in qualitative research, which contributed to increasing the credibility of the data analysis (Smith and Caddick Citation2012). The analysed data were arranged in compliance with the research questions (Hong and Coffee Citation2018) and the dual career development environment (DCDE) working model (Linnér et al. Citation2017) in the following section.

Results

Support services and systems for junior athletes

There are four major findings identified in this study: (1) financial support is the most prevalent type of support provided to junior dual career athletes across the countries, (2) existing support is not limited to junior athletes, which indicates that there are no tailored support packages for this age group, (3) some higher education institutions provide a holistic support package, but others only provided educational or financial support, and (4) there are very limited structured support systems/services identified exclusively for junior dual career athletes at the secondary school level (i.e. aged 15–17). The following sections will provide more details on the findings.

Collectively, the seven member countries (Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and the United Kingdom) identified between 10 and 36 organisational support services/systems for junior dual career athletes in their respective countries. The identified support services/systems are provided by different types of sports organisations, including charities, governmental institutions, local authorities, sport governing bodies, sports clubs, higher education institutions, sport schools, sports academies and leisure operators.

Below, the support systems/programmes identified from the data will be presented at two different levels – Micro (higher education institutions, sports clubs, sport schools and sports academies) and Macro (charities, governmental institutions, local authorities, sport governing bodies and leisure operators) levels.

Micro-level

Support from higher education institutions, sports clubs, sport schools and sports academies were identified across the countries as a key source of support for junior dual career athletes. For example, junior athletes who attend higher education institutions in the United Kingdom can receive a holistic support service including tutoring, academic flexibility, financial support and support from sport psychologists, nutritionists, strength and conditioning coaches, physios, and dual career management (e.g. timetabling, communication with lecturers and coaches, applying for an extension for assignments/exams in advance, etc.) to help them manage their dual careers. Not all universities, however, provided holistic support proposed in the HAC Model (e.g. athletic, psychological, psychosocial, academic/vocational and financial levels). While the universities in Spain and the United Kingdom indicated they provided support at different levels, other universities in other countries implied that they provided mainly financial support and admission/academic flexibility.

A small number of support schemes/services from sport clubs, sport schools and sports academies were also identified, which mainly included financial support (e.g. a small grant to cover travel expenses) and tutoring/academic flexibility. One of the issues identified related to financial support is that such support is not periodic but one-off/temporary and in some cases, such support schemes may have long periods of discontinuity. There was also good practice related to support from sports clubs. For instance, a sport club and a sport academy in Portugal help their junior athletes at high school combine sport and schoolwork by providing additional pedagogical support and professional training support. While most of the support from sport clubs, schools and academies is related to financial and educational support, there was one club identified in Italy that provides vocational training programmes to talented basketball players from age of 18 to 23 years old. In terms of support from secondary schools, there were several secondary schools and different departments within such secondary schools identified in Slovenia that provide some direct support to junior athletes; the support provided is mainly tutorial support and academic flexibility. Overall, compared to support from the higher education institutions, support from secondary schools is limited and less structured.

Macro-level

Some support from charities, governmental institutions, local authorities, sport governing bodies, and leisure operators was also identified across the countries. Although other levels of support mentioned in the HAC Model were identified such as athletic level (e.g. equipment, training venue, and coaching session support) and psychological level (e.g. sports psychologist support), it is notable that financial support, such as small grants to cover travel expenses and scholarships for attending higher education institutions, were mentioned as the most common support across the sports organisations and countries. Some national sport governing bodies provide their support programmes in cooperation with universities (e.g. Winning Students programme and Performance Lifestyle in the United Kingdom). In addition, some countries, such as Italy and Portugal, provided vocational support to athletes to help them integrate into the work environment. For instance, in Italy, athletes are appointed as army, air force and carabinieri personnel during their sports career, which allows them to develop their career outside of sport and secure their jobs in one of the defence sectors once they retire.

However, most of the support identified is not limited to junior athletes but also includes older athletes, which indicates a lack of support systems tailored for junior athletes. The support provided by a small number of secondary schools, contrastingly, including sports schools, solely targets the junior athletes aged between 15 and 19 years old. In addition, most of the national support programmes developed by the sports organisations/governing bodies in this study provide limited support services in relation to different levels of career development indicated in the HAC model.

Similarities or differences between the seven countries

All countries in this study have centralised sport systems (see ). In this respect, government bodies (e.g., Ministry of Culture and Sports [Greece], Ministry of Sport [Italy and Poland], Ministry of Education [Portugal], Ministry of Education, Science and Sports [Slovenia], Ministry of Culture and Sports [Spain], UK Sport [UK]) are the ones that are often responsible for establishing and implementing support schemes for dual careers of junior athletes. However, there are no specific schemes/systems developed by said bodies for junior dual career athletes. Although UK Sport has developed the Performance Lifestyle programme to assist athletes in balancing different commitments during their sporting career, the services are not tailored for the target population in this study.

Table 1. Support programme/services for dual career junior athletes

Five countries have no sports school system, while Poland (e.g. Sports Mastery Schools) and the United Kingdom (e.g. Glasgow School of Sport) have. However, among those countries that do not have sport school systems, some of them do have an equivalent form of initiatives. For example, in the case of Spain, the policies have been centralised by the High Council of Sports and they provide a programme for dual career support (PROAD) for elite athletes. In this respect, in the last decade some public bodies like Junta de Castilla y León, Junta de Extremadura and Gobierno de las Islas Baleares have been introduced, increasing the dual career support facilitation at regional level. In the compulsory school sector of Italy, the Sport Lyceum was recently established, within the humanities and scientific subjects. In the last 6 years, the number of participants has increased at the national level. In Greece, sports schools, both primary and secondary levels, operated for 20 years until the national financial crisis. In Slovenia, there are verified programmes at the secondary level of education (secondary schools), called Sports high school programmes or Sports departments, specially adapted for young dual career athletes. Moreover, there are some special schools called Unidade de Apoio ao Alto Rendimento na Escola (UAARE; Unity of Sport for High-level Athletes in School) that function for normal students with a special system embedded for high-level athletes in Portugal; athletes from all sports can attend this special system.

The findings in the current study show that most countries have not yet established a structured system to support junior dual career athletes at the level of secondary school. There was only one country, Slovenia, that identified some support services provided to junior athletes at secondary schools (n = 14), which is limited to educational support such as tutorial support and academic flexibility. This indicates that structured support systems/services with a holistic approach within secondary schools, designed to assist junior athletes in balance two different commitments, are lacking.

As emphasised in the previous section, many of the sports organisations across the countries provide financial support in the form of a small grant to cover equipment, travel expenses, and sport science and medical support such as physio, sport psychology support, and strength and conditioning support (e.g. TASSFootnote1 in England and Winning studentsFootnote2 in Scotland). The higher education institutions in the United Kingdom, such as the University of Stirling and the University of Bath, have holistic support for student-athletes as mentioned earlier, but not at the secondary school level. Although other countries such as Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain and Slovenia identified some support from their higher education institutions, such support is limited to educational or financial support such as tutorial support, academic flexibility, scholarships, fee waiver and grants.

As aforementioned, some sports organisations provide vocational support (e.g. Italy, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom). However, the majority of support appears to focus on education over vocation (see ). This finding is also in line with the results at the micro-level in the previous section that educational support (e.g. tutoring and academic flexibility) was mainly provided.

Discussion

The findings in this study provide an overview of existing support services/systems in seven European countries and identify gaps in practice in terms of supporting junior athletes. The findings indicated that more support resources and structured systems for junior athletes which contribute to different levels of their career development proposed in the Holistic Athlete Career (HAC) Model (Wylleman et al. Citation2013) are needed. In addition, the data were also analysed and presented based on the dual career development environment (DCDE) working model (Linnér et al. Citation2017), which helped present the key findings in this study at different levels of the dual career environment.

Financial support was prominent at both micro and macro levels across dual career support. In the HAC model, family (parents) and sport governing bodies are the main sources of financial support that junior athletes receive. Although research on financial support provided by sport governing bodies is limited, parents’ role in providing financial support has been highlighted in many studies. Specifically, it has been highlighted that parents provide financial support to their children (Bloom Citation1985) that allows them to access coaches/sports facilities and limit their children’s need to be involved in paid jobs; this can help them pursue success in both sport and study (Wolfenden and Holt Citation2005). However, the findings in this study show that such financial support is not only provided by parents (family) and sport governing bodies as indicated in the HAC model. Such support is also from sports clubs, educational institutions, charities and other local authorities. Cutrona and Russell (Citation1990) identified that tangible support, such as financial support, can assist individuals in coping with stressful events that can be caused by a conflict between sport and study in a dual career context (Baron-Thiene and Alfermann Citation2015, Pummell et al. Citation2008; Stambulova et al. Citation2012; Stambulova and Wylleman Citation2014). Cosh and Tully (Citation2015) identified financial pressure as one of the main causes of stressors that dual career athletes can face. In Franck and Stambulova’s (Citation2019) study, it was also found that junior athletes who went through the junior-to-senior transition faced some difficulties due to the decreased financial support from the clubs that support athletes at national/international levels, and the increased financial pressure they faced such as covering travel expenses for international competitions, purchasing equipment, hiring training venues and personal coaches as they made a progress on their sporting career. Morris et al. (Citation2016) also suggested that junior athletes need further tangible support, such as financial assistance, to keep pursuing their sporting careers. This indicates that financial burden/struggles and financial support schemes should be provided for junior athletes. In this regard, it is worth noting that the findings in this study indicate that some financial support is temporary and, in some cases, such support had long periods of discontinuity, which should be considered and improved to ensure sustainable provision for athletes.

It was also observed that some higher education institutions provide holistic support, but others only provided educational (e.g. tutorial support and academic flexibility) or financial support (e.g. scholarships). Although existing support should be still appreciated, athletes’ barriers and challenges concerning their dual careers are not limited to educational and financial aspects. For instance, one of the prime personal barriers to successful dual careers that has been identified from different studies (e.g. Franck et al. Citation2016; Stephan and Brewer Citation2007) is ‘athletic identity’, which makes athletes prioritise sport over other commitments, including, in particular, education. In this regard, Wylleman and Rosier (Citation2016) argued that young athletes experiencing junior-to-senior transitions may prioritise sport over education due to the development of their strong athletic identity. To balance athletic and non-athletic identities requires increased independence, responsibility, and discipline (Rosier et al. Citation2015), as well as coping skills/strategies to manage unexpected events (e.g. injuries), expectation, and pressure (Wylleman et al. Citation2013). Therefore, it has been considered important for athletes to develop a well-rounded identity, which a holistic support provision can help do (Pummell et al. Citation2008). Therefore, it should be noted that such holistic support is still lacking in practice, which should be addressed by both micro and macro levels of dual career environments (Linnér et al. Citation2017).

It was evident that most existing support services/systems, in particular at the macro level, were not limited to junior athletes but included older athletes, which indicates support systems customised for junior athletes are lacking. The reason why a specific focus should be given to this population is that these adolescent athletes are more at risk of dropping out from sport or education due to a failure to manage these two (often competing) commitments (Pavlidis and Gargalianos Citation2014, Baron-Thiene and Alfermann Citation2015). This indicates there is a need to develop coping resources and support that fits junior athletes’ needs. In this regard, athletes can experience a successful transition to senior sport when their coping skills and resources correspond with transition demands (Morris et al. Citation2016). Although it is beyond the scope of the current study to identify junior athletes’ experiences of limited support services and systems, it can be thought based on the findings in the current study and literature that junior athletes are still exposed to hard experiences and risk of dropout without customised support for them.

As mentioned earlier, the Erasmus+ programme has prioritised dual career development with the aim of helping dual career athletes to balance sport and study (European Commission Citation2007, Citation2012). In this regard, there have been dual career support programmes developed within Europe with the support of the European Commission, including Be a winner in elite sport and employment before and after athletic retirement (B-Wiser Consortium Citation2019) and Gold in Education and Elite Sport (GEES Consortium Citation2016). Nonetheless, it was found by López-Flores et al. Citation2020a that holistic support provision is still limited, which was confirmed by the evidence in this study. One of the major findings in this study is that there is very limited structured support system/service for junior dual career athletes identified at the secondary school level compared to higher education institutions, which indicates that a proper environment for junior athletes partaking in dual careers has not yet been established. Morris et al. (Citation2020) identified and classified the different types of dual career development environments (DCDEs), which provides an overview of the existing environments for dual career athletes across Europe. The DCDE types identified include sport-friendly schools (e.g. Talented Athlete Scholarship Scheme Accredited Schools and Colleges), elite sports schools/colleges (e.g. Scottish Football Association Performance Schools), professional and/or private clubs (e.g. football clubs), sport-friendly universities (e.g. Team Bath at University of Bath, Loughborough University, and Winning Students at Universities in Scotland), combined dual career systems (e.g. the Talented Athlete Scholarship Scheme), national sports programmes (e.g. Sport Scotland Institute of Sport, English Institute of Sport and Sport Wales), defence forces programmes (e.g. the Talented Athlete Scholarship Scheme Army Elite Sports Program), and players union programmes (e.g. the Professional Footballers Association and the Rugby Players Association). Since it was beyond the scope of their study, the target age groups for such programmes were not identified. However, as evidenced in this study, the programmes/schemes identified in both Morris et al.’s (Citation2020) study and the present study are not limited to junior athletes, but also include other age groups, in particular older athletes. Although Morris et al. (Citation2020) did identify some support provision at secondary schools, the support is limited to academic flexibility, access to sports facilities and sport science provision. The findings in the current study also indicated that support from secondary schools is limited to educational support such as academic flexibility. This, therefore, highlights a gap in support provision at secondary schools for junior athletes, and the need to establish support services/systems with a holistic approach for this age group.

Conclusion

This study aimed to understand the support provided to junior dual career athletes within sport organisations, sports clubs, schools, higher education institutions and national governing bodies in seven different European countries. The findings from this study extend the knowledge of organisational support for junior athletes undertaking dual careers and identify a clear gap in both literature and practice – a lack of holistic support systems for junior athletes aged between 15 and 19 years old. This gap should be addressed by policymakers and different stakeholders such as sports organisations/governing bodies and educational institutions to improve the environment for junior dual careers athletes. Considering that EU guidelines on dual careers were published by the European Commission almost a decade ago, such identified gap in practice could be addressed based on evidence from the well-founded research findings in this area, including the evidence in the present study.

In addition, the study highlights the importance of taking a holistic approach to support provision. It is hoped that the evidence in this study raises awareness of the need for a customised support system for junior athletes and contributes to the development of evidence-based holistic support schemes. As mentioned earlier, the findings in this study contribute to expanding the literature by providing evidence of existing support and resources for junior athletes based on the dual career development environment (DCDE) working model. While the HAC model has been applied to several studies focusing on dual career athletes, athletes’ career development and transitions (Drew et al. Citation2019), the present study shows that the DCDE working model can be a useful framework to examine support provision from different stakeholders at both micro and macro levels, which can help develop understanding of the existing environments available for junior dual careers athletes.

Since sport governing bodies, sports organisations, sports clubs and educational institutions have limited resources to develop a support scheme, it may be not realistic to provide support that addresses all the different levels of support indicated in the HAC model. Therefore, organisations may need to focus on covering the most needed areas. In this regard, future research could investigate junior athletes’ primary needs; this can inform relevant bodies of the priority areas to target their resources at. Although the findings in this study provided evidence that financial support was in place across the countries studied, it is still unknown how many junior athletes take advantage of financial support from sport governing bodies and how such support impacts their dual careers. Future studies could investigate in-depth narratives of junior athletes and their experience associated with financial support.

Acknowledgements

“Dual Career for Junior Athletes (DCJA)” is an Erasmus+ Sport project funded by the Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA) on the EAC/A02/2019 call, Project reference 613272-EPP-1-2019-1-PL-SPO-SCP. The provision of financial support does not in any way infer or imply endorsement of the research findings by the EACEA. The authors would like to express their gratitude to all members of the Erasmus+ sport project entitled ‘Dual Career for Junior Athletes’ (DCJA) for their cooperation during this study and the entirety of the project. Please note that Dr Grzegorz Botwina was a coordinator of the DCJA project at the Institute of Sport – National Research Institute, Poland during the data collection for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The Talented Athlete Scholarship Scheme (TASS) is a Sport England funded partnership between talented athletes, education institutions and national governing bodies of sport. https://www.tass.gov.uk/

2. Winning Students was established in May 2009 as Scotland’s national sports scholarship programme supporting student athletes. https://www.winningstudents-scotland.ac.uk/

References

- Aquilina, D., 2013. A study of the relationship between elite athletes’ educational development and sport performance. The international journal of the history of sport, 30 (4), 374e392. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2013.765723

- Azungah, T., 2018. Qualitative research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative research journal, 18 (4), 383–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00035

- Baron-Thiene, A. and Alfermann, D., 2015. Personal characteristics as predictors for dual career dropout versus continuation—A prospective study of adolescent athletes from German elite sport schools. Psychology of sport and exercise, 21, 42–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.006

- Bloom, B.S., 1985. Developing talent in young people. New York: Ballantine.

- Carless, D. and Douglas, K., 2013. “In the boat” but “selling myself short”: stories, narratives, and identity development in elite sport. The sport psychologist, 27 (1), 27–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.27.1.27

- Chen, H.Y., and Boore, J.R., 2010. Translation and backtranslation in qualitative nursing research: Methodological review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19 (1–2), 234–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02896.x

- Consortium, B.-W. 2019. Be a winner in elite sport and employment before and after athletic retirement. Retrieved from http://www.bwiser.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/B-Wiser_3-luik_A5_2018.pdf

- Cosh, S. and Tully, P. J., 2015. Stressors, Coping, and Support Mechanisms for Student Athletes Combining Elite Sport and Tertiary Education: Implications for Practice. Sport Psychologist, 29 (2), 120–133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2014-0102

- Cutrona, C.E. and Russell, D.W., 1990. Type of social support and specific stress: toward a theory of optimal matching. In: B.R. Sarason, I.G. Sarason, and G.R. Pierce, eds. Social support: an interactional view. New York: Wiley, 319–366.

- Danish, S.J., Petitpas, A.J., and Hale, B.D., 1993. Life development intervention for athletes. The counseling psychologist, 21 (3), 352–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000093213002

- Drew, K., et al., 2019. A meta-study of qualitative research on the junior-to-senior transition in sport. Psychology of sport and exercise, 45 (Article), 101556. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101556

- European Commission. 2007. White paper on sport. Brussels: Directorate General for Education and Culture.

- European Commission. 2012. EU guidelines on dual careers of athletes: recommended policy actions in support of dual careers in high-performance sport (pp. 1–40). Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/sport/library/documents/dual-career-guidelines-final_en.pdf

- Franck, A. and Stambulova, N., 2018. The junior-to-senior transition: a narrative analysis of the pathways of two Swedish athletes. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1479979

- Franck, A., Stambulova, N.B., and Ivarsson, A., 2016a. Swedish athletes’ adjustment patterns in the junior-to-senior transition. International journal of sport and exercise psychology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1256339

- GEES Consortium. 2016. Gold in education and elite sport. Retrieved from http://gees.online/?page_id=304&lang=en

- Henriksen, K., et al., 2020. A holistic ecological approach to sport and study: the case of an athlete friendly university in Denmark. Psychology of sport and exercise, 47, 101637. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101637

- Henry, I., 2013. Athlete development, athlete rights and athlete welfare: a European Union perspective. The international journal of the history of sport, 30 (4), 356–373. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2013.765721

- Hong, H.J. and Coffee, P., 2018. A psycho-educational curriculum for sport career transition practitioners: development and evaluation. European sport management quarterly, 18 (3), 287–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1387925

- Lally, P., 2007. Identity and athletic retirement: a prospective study. Psychology of sport and exercise, 8 (1), 85–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport

- Linnér, L., Stambulova, N., and Henriksen, K., 2017. Holistic approach to understanding a dual career environment at a Swedish university. In: G. Si, J. Cruz, and J.C. Jaenes, eds. Sport psychology – linking theory to practice: proceedings of the XIV ISSP world congress of sport psychology. Sevilla, Spain, 243–244.

- López de Subijana, C., Barriopedro, M., and Conde, E., 2015. Supporting dual career in Spain: elite athletes’ barriers to study. Psychology of sport and exercise, 21, 57–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.012

- López-Flores, M., 2020. May the Mentor be with You! An innovative approach to the Dual Career mentoring capacitation. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte 16(47) 107–116.

- López-Flores, M., Hong, H.J., and Bowtina, G., 2020a. Dual career of junior athletes: Identifying challenges, available resources, and roles of social support providers. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 16(47), 117-129.

- López-Flores, M., Penado, M., Avelar-Rosa, B., Packevičiūtė, A. & Ābeļkalns, I. 2020b. May the Mentor be with You! An innovative approach to the Dual Career mentoring capacitation. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 16(47), 107-116.

- Morris, R. (2013). Investigating the youth to senior transition in sport: from theory to practice. Doctoral dissertation, Aberystwyth, United Kingdom: Aberystwyth University

- Morris, R., et al., 2020. A taxonomy of dual career development environments in European countries. European sport management quarterly. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1725778

- Morris, R., Tod, D., and Eubank, M., 2016a. From youth team to first team: an investigation into the transition experiences of young professional athletes in soccer. International journal of sport and exercise psychology, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1152992

- Morris, R., Tod, D., and Oliver, E., 2015. An analysis of organizational structure and transition outcomes in the youth-to-senior professional soccer transition. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 27 (2), 216–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2014.980015

- Morris, R., Tod, D., and Oliver, E., 2016b. An investigation into stakeholders’ perceptions of the youth-to-senior transition in professional soccer in the United Kingdom. Journal of applied sport psychology, 28 (4), 375–391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2016.1162222

- Pavlidis, G. and Gargalianos, D., 2014. High performance athletes’ education: value, challenges and opportunities. Journal of physical education and sport, 14 (2), 293–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2014.02044

- Petitpas, A., Brewer, B.W., and Van Raalte, J.L, 2009. Transitions of the student- athlete: theoretical, empirical, and practical perspectives. In: E.F Etzel, ed. Counseling and psychological services for college student-athletes. Morgantown: Fitness Information Technology, 283–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2011.581945

- Pink, M., Saunders, J., and Stynes, J., 2015. Reconciling the maintenance of on-field success with off field player development: a case study of a club culture within the Australian football league. Psychology of sport and exercise, 21, 98–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.11.009

- Price, N., Morrison, N., and Arnold, S., 2010. Life out of the limelight: understanding the non-sporting pursuits of elite athletes. The International Journal of Sport and Society, 1 (3), 69–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.18848/2152-7857/CGP/v01i03/54034

- Pummell, B., Harwood, C., and Lavallee, D., 2008. Jumping to the next level: a qualitative examination of within career transition in adolescent event riders. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9 (4), 427–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.07.004

- Rosier, N., 2015. The Transition from Junior to Senior Elite Athlete. In Proceedings 14th European Congress of Sport Psychology edited by O. Schmid and R. Seiler, 162. Bern, Switzerland.

- Ryan, C., 2015. Factors impacting carded athlete’s readiness for dual careers. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 91–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.008

- Ryan, C., Thorpe, H., and Pope, C., 2017. The policy and practice of implementing a student-athlete support network: a case study. International journal of sport policy and politics, 9 (3), 415–430. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1320301

- Sammut-Bonnici, T. and McGee, J., 2015. Case study. In: C.L. Cooper, J. McGee, and T. Sammut-Bonnici, eds. Wiley encyclopaedia of management. Chichester: Wiley, 1–2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118785317.weom120012

- Smith, B. and Caddick, N., 2012. Qualitative methods in sport: a concise overview for guiding social scientific sport research. Asia pacific journal of sport and social science, 1 (1), 60–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21640599.2012.701373

- Sorkkila, M., Aunola, K., and Ryba, T.V., 2017. A person-oriented approach to sport and school burnout in adolescent student-athletes: the role of individual and parental expectations. Psychology of sport and exercise, 28, 58–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.10.004

- Stambulova, N.B. and Ryba, T.V., 2013. Athletes’ careers across cultures. NY: Routledge.

- Stambulova, N., Stambulov, A., and Johnson, U., 2012. ‘Believe in yourself, channel energy, and play your trumps’: Olympic preparation in complex coordination sports. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13, 679–686.

- Stambulova, N., and Wylleman, P., 2019. Psychology of athletes’ dual careers: A state-of the art critical review of the European discourse. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 74–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.11.013

- Stambulova, N., and Wylleman, P., 2014. Athletes’ career development and transitions. Routledge companion to sport and exercise psychology. In: A. Papaioannou, and D. Hackfort, eds. Routledge companion to sport and exercise psychology. London: Routledge, 605–621.

- Stambulova, N., 2009. Talent development in sport: a career transitions perspective. In: E. Tsung-Min Hung, R. Lidor, and D. Hackfort, eds. Psychology of sport excellence. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology, 63–74.

- Stephan, Y. and Brewer, B.W., 2007. perceived determinants of identification with the athlete role among elite competitors. journal of applied sport psychology, 19 (1), 67–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200600944090

- Tekavc, J., Wylleman, P., and Cecić Erpič, S., 2015. Perceptions of dual career development among elite level swimmers and basketball players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 27–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.03.002

- Torregrosa, M., et al., 2015. Olympic athletes back to retirement: a qualitative longitudinal study. Psychology of sport and exercise, 21 (1), 50–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.03.003

- Tshube, T. and Feltz, D.L., 2015. The relationship between dual-career and post-sport career transition among elite athletes in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 109–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.05.005

- Vanden Auweele, Y., et al., 2004. Parents and coaches: a help or harm? Affective outcomes for children in sport. In: Y. Vanden Auweele, eds. Ethics in youth sport. Leuven, Belgium, 179-193: Lannoocampus.

- Wolfenden, L.E. and Holt, N.L., 2005. Talent development in elite junior tennis: perception of players, parents, and coaches. Journal of applied sport psychology, 17 (2), 108–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200590932416

- Wylleman, P., 2000. Interpersonal relationships in sport: uncharted territory in sport psychology research. International journal of sport psychology, 31, 1–18.

- Wylleman, P., Alfermann, D., and Lavallee, D., 2004. Career transitions in sport: European perspectives. Psychology of sport and exercise, 5 (1), 7–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(02)00049-3

- Wylleman, P. and Lavallee, D., 2004. A developmental perspective on transitions faced by athletes. In: M Weis, ed. Developmental sport and exercise psychology: a lifespan perspective. Morgantown, WV: Fitness International Technology, 507–527.

- Wylleman, P. and Reints, A., 2010. A lifespan perspective on the career of talented and elite athletes: perspectives on high-intensity sports. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 20 (2), 88–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01194.x

- Wylleman, P., Reints, A., and De Knop, P., 2013. Athletes’ careers in Belgium. A holistic perspective to understand and alleviate challenges occurring throughout the athletic and post- athletic career. In: N. Stambulova and T. Ryba, eds. Athletes’ careers across cultures. New York NY: Routledge—ISSP, 31–42.

- Wylleman, P. and Rosier, N., 2016. Holistic perspective on the development of elite athletes. In: M. Raab, et al., eds. Sport and exercise psychology research: from theory to practice. London: Elsevier, 269–288.

- Wylleman, P., et al., 2007. Parenting and career transitions of elite athletes. In: S. Jowett and D.E. Lavallee, eds. Social psychology of sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 233–248.

- Wylleman, P., et al., 1993. Career termination and social integration among elite athletes. In: S. Serpa, et al., eds. Proceedings of the VIII world congress of sport psychology. Lisbon, Portugal: International Society of Sport Psychology, 902–906.

- Yin, R.K., 2003. Case Study Research: design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.