ABSTRACT

The world is, again, witnessing a humanitarian ‘crisis’, as over seven million Ukrainian refugees have fled the border at the time of writing. Culturally sensitive practices are keys in leveraging sport for migrants. Yet, this research has not explored what cultural sensitivity is, regarding Central- and Eastern European (CEE) migrants. This paper assessed culturally contingent components when considering CEE migrants inclusion into European sport. The Delphi method was deployed, and three rounds of data collection were conducted. 19 CEE experts in sport (researchers, NGOs, governmental employees) were recruited to jointly produce a set of consensual directives. The results were analysed with Bronfenbrenner’s Process-Person-Context-Time model. The key agreements consisted of four significant themes. Facilitators included shared experiences of (organised) sport, and CEE migrants’ familiarity with other cultures. Barriers included the nature of labour migration on time- and economy to engage in leisure, and stereotypical and misleading perceptions of ‘post-soviet residents’. In conclusion, the results show that a range of similarities may exist between CEE and European (sport) contexts that could be conducive to CEE migrants’ inclusion into European sport, but that practitioners will need to be aware of sensitive Soviet history.

Introduction

The world continues to witness devastating numbers of displaced people, as the conflict in Ukraine has forced over seven million people to flee across the border (UNHCR Citation2022). Sport continues to be a salient asset for governments – a vehicle to improve the lives of migrants and provide a space for health, leisure and belonging. However, critique has been raised against governing sport bodies’ failure to acknowledge the super-diversity between (and within) migrant groups (Agergaard Citation2018). Other research show promising results of culturally tailored physical-activity programmes for migrants (Montayre et al. Citation2020), and, echoes Coalter’s (Citation2013) idea that sport can only be of use if we consider factors such as who benefits from sport under what circumstances. This calls for a more nuanced analysis than simply conceiving migrants as a homogenous group.

Although research has illuminated the importance of culturally sensitive sport delivery (e.g., Ahmad et al. Citation2020), this has rarely included migrant populations from Central- and Eastern Europe (CEE) (for an overview of populations in sport-and-migration, see e.g., Spaaij et al., Citation2019). That is, while research have, for instance, highlighted how programmes must accommodate for appropriate clothing and times for praying amongst Muslim migrant populations (Montayre et al., Citation2020), little is known about such (cultural) components for a CEE population. Drawing from the broader migration literature, CEE migrants may face different obstacles, such as magnified discrimination based on cultural, rather than racial, differences (Fox et al. Citation2015). However, such obstacles (or advantages) remain unexplored in the sport context. Given the unique sporting history of CEE countries alongside other unique political and social dimensions (Edelman and Wilson, Citation2017), such factors tentatively exist. Recent research into European sport clubs’ reception of Ukrainian refugees, for instance, suggest that some representatives must negotiate ideas about youth sports and early specialisation, in particular in gymnastics club (Blomqvist Mickelsson, Citationsubmitted). Such preliminary findings suggest that there is more to be uncovered regarding CEE migrants in sports.

In summary, the study aim was to examine CEE migrants’ utilisation of sport for integration. A Delphi approach was employed, consisting of 19 sport experts with substantial experience from CEE countries. As the study was data-driven and exploratory, integration as a concept was not pre-defined but instead defined by the experts. The following research questions guided this study: What are the contextual factors necessary- or detrimental to facilitate integration through sport? What factors are specific to CEE migrants? The results were analysed with Bronfenbrenner’s Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) approach. The paper proceeds as follows: I briefly sketch out the historical backdrop to post-socialist migration, and the forced migration currently happening from Ukraine. I then review the sport for-integration-literature through the lenses of the PPCT approach to illuminate the utility of the current theoretical framework. Subsequently, I provide a definition of culture, based on Vélez-Agosto et al.’s (Citation2017) modification of Bronfenbrenner’s model. Subsequently, I account for the methodological aspects of the Delphi method. Finally, results are presented, discussed and some recommendations are offered to practitioners that might be working with this population within a near future.

Migration from the post-socialist regions: a primer

The post-socialist regions have a significant history of migration, although this has been overshadowed by migratory movements from the Middle East the last decade. This brief section cannot cover this in its entirety; however, a few significant events are worth illuminating. These include the Soviet Union collapse, the inclusion of several post-socialist countries into EU, and contemporarily, the forced migration from Ukraine.

The Soviet Union constituted an impressive ethnic mosaic. Upon the Soviet Union’s dissolution, the individual states embarked on their own journeys, and many states expected that people would migrate to their historically ‘real’ state (e.g., Kazakhs to Kazakhstan). However, what became the actual reason for migration, and choice of destination, was the economic depression that struck the post-socialist regions (Tishkov et al. Citation2005). Between 1992 to 2002, approximately 2.6 million people emigrated, and the main destinations were widespread: Germany, the US and Israel (Tishkov et al. Citation2005). However, there were still greater migration numbers within, rather than outside, the CEE regions. These patterns were later altered, as many CEE countries gradually moved towards a European identity.

In 2004, eight CEE countries (A8) gained EU-membership, and migration patterns drastically changed. Compared to the rather low migration occurring between 1992 and 2002 (around 2.6 million people), the UK alone received around 500.000 migrants between 2004 and 2006 from post-socialist countries (Blanchflower et al. Citation2007). In 2008, Polish authorities estimated that 2.3 million Poles were working in Western Europe (Friberg Citation2012b). Blanchflower et al. (Citation2007) argue that changes in migration policies along with UK’s favourable economic position was incentivising for post-socialist migrants. In reviewing the key themes of CEE migration to UK, Burrell (Citation2010) concurs that this migration must be understood from an economic perspective, but that the migrants are heterogeneous as shown in their ambitions, intentions to stay and patterns of return-migration. Although migration from A8 countries has been thoroughly researched within the UK context, it must be mentioned that CEE migrants have taken up work and livelihoods elsewhere too. For instance, Norway’s largest ethnic minority group is Poles, many of which emigrated to Norway after the accession to EU (Friberg Citation2012b). Based on his analyses, Friberg (Citation2012b) contended that, although CEE migrants often are analysed as transnational migrants, a fair share of them also bring their families and settle down.

In late February 2022, the nature of CEE migration changed, as Russian forces entered Ukraine. Women, elderly, and children quickly fled across the border, while males between 18 and 60 were legally required to stay. The UNHCR estimated that, on the 6th of July 2022, over 5.6 million displaced Ukrainian refugees resided somewhere in Europe (UNHCR Citation2022). Accordingly, the contemporary humanitarian crisis can be said to bear a few characterising features: the people fleeing are forced refugees, and are predominantly female, youths and elderly. Moreover, the destinations are almost exclusively European countries. While little research has been conducted given the novelty of these events, we know that civil society has been playing a crucial role in the reception of Ukrainian refugees (Byrska Citation2022) and that sport clubs have been quick to respond to the needs of this group (Blomqvist Mickelsson, Citationsubmitted)]. Given the demographics of Ukrainian forced migration, there is, perhaps, a greater emphasis on youth sport for sport clubs this time around. However, this needs to be explored, and what we currently know is that CEE (adult) migrants’ rates of physical activity are usually low, with females being at particular risk for exhibiting low levels of physical activity (Mickelsson, Citation2021). Moreover, although CEE migration has received little attention, a few works show that social, political, and cultural factors are at play that impinge on CEE migrants’ inclusion into sport (Long and Hylton Citation2002, Evans and Piggott Citation2016). These factors need to be further explored, to fully understand how sport can accommodate for, and meet the needs of CEE migrants and refugees.

Sport-for-integration research through the lenses of the PPCT model

Bronfenbrenner’s PPCT approach is a development of his socio-ecological framework. The socio-ecological framework posits that human development can be understood as a nested arrangement of structures (Bronfenbrenner Citation1977), ranging from the micro-, meso-, exo-, to macro-systems. Bronfenbrenner later added significant changes to the framework, notably the individual’s characteristics and the link between the developing person and the context: the proximal process. The proximal process constitutes a significant share of the developmental engine and refer to the ‘ progressively more complex reciprocal interaction between an active, evolving biopsychological human organism and the persons, objects, and symbols in its immediate external environment ’, over time (Bronfenbrenner and Morris Citation1998, p. 996).). Moreover, Bronfenbrenner (2005) laid out three individual characteristics that are important in the interaction with the individual’s surroundings: demand-factors, such as age, sex, and other demographics; resource-factors are the resources the individual has at her disposal and are induced by demand-factors. Finally, force-factors represents the individual’s agency, i.e., the ability to choose to use her resources. Despite these significant changes, the majority of sport studies use the old versions (Dickson and Darcy Citation2021) and has been ‘ misunderstood and misapplied’ (DiSanti and Erickson Citation2020, p. 2).

Interpreted from the lenses of Bronfenbrenner, refugees carry with them experiences, strengths and vulnerabilities that are of importance when they navigate and interact with host society environments. For instance, refugees escaping war usually embark on a potentially long and dangerous journey, and they may bear the marks of physical- and psychological trauma due to the events in the home country. Such experiences become part of an individual’s ‘resource factors’ – an internal state, that can be heavy to bear (e.g., anxiety, depression), but also be related to, for instance, resilience (Olliff Citation2008). Such experiences may shape the individual, and they may also affect the perceptions and reactions of the surroundings. Sport can be a mediator to address such resource factors, by combating negative feelings and partially alleviate some of the stress experienced by refugees (Ley et al., Citation2017). Ley et al. (Citation2022) also found that sport can enhance refugees’ sense of mastery and induce greater agency. In this regard, if the sporting environment accommodates for a pleasant experience, proximal processes are likely to arise where agency (i.e., force factors) and a sense of competence (i.e., demand factors) are nurtured. Other research shows that sport can enable social relationships, and offer a social support system (Koopmans and Doidge Citation2022) which is of magnified importance in the refugee context due to already eroded social networks. Again, it is essential that the environment is conducive to such (social) experiences.

However, sport is also negatively conditioned by the emphasis on certain personal competencies. For example, Dukic et al. (Citation2017, p. 101) found that ‘ the often-ignored importance of a sporting habitus and physical capital ’ played a critical role for refugees’ inclusion into Australian soccer. Accordingly, the sport-specific resources of these refugees were critical, in particular since their environment centred on sport’s competitive logic (Skille Citation2010), and valued skilled players. On the contrary, when sport clubs take an active approach to refugees’ inclusion and construct their environment to be relaxed and foregrounded by fun, the importance of refugees’ sport-specific (resource) skills are drastically diminished. Doidge et al. (Citation2020) explored a sport club with an explicit social inclusion-agenda and found that the most critical component was to construct a milieu with a coherent philosophy, that allowed for socialising opportunities. In turn, this emphasis downplayed the value of competition and allowed for pleasant social encounters. In a similar vein, Mohammadi (Citation2019) followed a community sport project with refugee women. The activities consisted of riding bikes, which was a new experience for the women. In other settings, the lack of sporting habitus would have likely excluded the women; however, the sport project was constructed to ensure a safe and enjoyable learning experience, which made it conducive to their participation. In this regard, environments interact with the person’s characteristics, for better or worse.

Unfortunately, sport may also facilitate social exclusion (Spaaij Citation2012) and fuel conflict between groups (Cubizolles Citation2015). Krouwel et al. (Citation2006, p. 165) argued that ‘ inter-ethnic tensions from other social spheres are imported and even magnified in these sports activities’. Telling examples of this can be found in Dowling’s (Citation2020) case study, where Norwegian sport club personnel ostracised and ‘othered’ refugees to the extent where they left the club, despite having been funded to support their inclusion into Norwegian sport. Here, other person-characteristics come into play, namely refugees’ demand factor in terms of sheer background, in combination with a widespread fear and stigmatisation of refugees in general (Dowling Citation2020). Accordingly, it is essential that members, leaders (Jeanes et al., Citation2019), and the club philosophy (Stura Citation2019, Doidge et al. Citation2020) are in tune with the scope of including people with diverse backgrounds. Both in the Danish (Agergaard Citation2018) and the Australian context (Spaaij et al. Citation2020), sport organisations proclaim to be ‘color-blind’ and offer equal opportunities to everyone. According to Agergaard (Citation2018) this seems peculiar, considering that migrants already are disadvantaged to start with. Spaaij et al. (Citation2020) discovered how discursive practices in organisations slowed down inclusionary practices, such as downplaying the complexity of social inclusion or pointing out individual deficits as the root of the cause, and Nowy et al. (Citation2020) found that only 14% of over 5000 German sport clubs initiated some sort of change to their organisation to welcome refugees. Tentatively, when the context is restrictive and less inclusive, refugees and migrants may need to prove themselves resourceful, notably through skills (e.g., Dukic et al. Citation2017). This is not to say that refugees always will do so; for instance, refusing to partake in organised sports can be indicative of refugees and migrants’ agency, i.e., their choice not to partake (i.e., the force factor).

Accordingly, most of the proximal processes take place in the micro-setting of Bronfenbrenner’s PPCT-model, however, other important meso- and exo-level settings shape how these processes look like. These are, for example, how sport federations enable the inclusionary work of sport clubs. For instance, in Blomqvist Mickelsson (Citation2022), sport federation officials constituted a significant mediator between sport clubs and collaborators and ensured that they could sustain enough funding to continue include underrepresented groups. Accordingly, if sport clubs’ surroundings, such as collaborators and federations, offer little support, sport clubs may revert to being exclusively competitive, and may exclude underrepresented groups (Stenling Citation2015). In this regard, sport federations are an important meso- to exo-level element since they are the backbone of the (European) sport movement, and in charge of the sport movement’s development (Blomqvist Mickelsson Citation2022 De Bock et al., Citation2021).

A brief definition of culture

Much of the literature that has illuminated refugees and migrants’ inclusion into sport has utilised concepts such as ‘cultural safe-spaces’ and ‘cultural sensitivity’. According to Spaaij and Schulenkorf (Citation2014), carefully constructed safe spaces allow diverse individuals to co-exist, and interact within the same proximity, and thus fulfill many ideas about inclusion and integration. Minorities may experience a range of receptions in sport clubs, where, however, a certain cultural dominant standard usually prevails (Mickelsson, Citation2022). This cultural standard often implies that migrants and refugees must assimilate, or that cultural diversity is tolerated, as long as migrants and refugees adapt to certain traditions and norms (Schaillée et al. Citation2019). Unsurprisingly, cultural safe spaces are imperative since stereotypical perceptions of certain cultures invoke stigmatisations and an ‘othering’ gaze on migrants (Mickelsson, Citation2022). It therefore becomes essential for culturally diverse individuals to be able to express themselves without the fear of becoming excluded or belittled (Symons Citation2021). For example, without options for modest clothing (Ahmad et al., Citation2020) or an understanding of how mixed-gender classes impact on Muslim women’s sport participation (Walseth Citation2015), inclusion in and through sport is difficult to achieve.

Nevertheless, a clear and explicit understanding of culture is warranted. Bronfenbrenner (2005) referred to culture as a sort of a blueprint, governing traditions, behavioural patterns, and norms of a particular (sub)group, as part of the macrosystem. However, Bronfenbrenner has been criticised based on how culture remains a vaguely defined concept with unclear analytical utility (Vélez-Agosto et al., Citation2017). Vélez-Agosto et al. (Citation2017, p. 906) argue that:

individuals participate in cultural practices shaped by context specificity and interact with communities and social institutions that are both proximal and distal Culture is embedded in all institutions that have the power to homogenize the daily routines within that context through political policies, laws, and regulations. Individuals interact in different contexts and internalize certain cultural values and practices

Through these suggestions, Vélez-Agosto et al. (Citation2017) move culture from the macrosystem, to the microsystem, arguing for culture’s embeddedness at the ‘lower’ levels. As the authors further add, individuals are embedded within different ecologies, at different times and may internalise different values – these values may nevertheless be negotiated, and the individual affect her milieu as well. In the current study’s case, we might suspect that CEE migrants, as a broader group, might be unified by some broad cultural pattern that is internalised and expressed in day-to-day activities (to various degrees). For example, ‘shooting for Lithuania’, along with own rules of basketball and own ethnic leagues (Evans and Piggott Citation2016) could be an example of how culture is expressed at the microlevel, and even embodied through the way these basketball players play.

Method

Design

The current study sought to create guidelines based on consensual expert assessment. A Delphi study is typically conducted in three rounds, where the first round is an open-ended survey. This first round has been called ‘brainstorming’, where participants freely elaborate on the issue. Subsequently, participant’s answers are coded, and themes that emerge are quantified. In the second round, participants are asked to rate the quantified items. In the final round, the items are refined and re-sent to the experts to build further consensus (Dalkey et al. Citation1970). This refinement of items is based on quantitative ratings but also relies on expert’s qualitative contextualising comments to their ratings. This procedure allows for continuous extraction of information, progress towards consensus, and refinement of final items (Hsu and Sandford Citation2007). The method is based on the anonymity of the participants, but participants’ answers are coded and subsequently presented. In light of the results from the panel, the process allows participants to revise their opinions, allowing for a ‘quiet’ dialogue (Dalkey and Helmer Citation1963). The current study considered a threshold of 75%, counting as consensus. Items that were dropped from the analysis received below 50% of support. In the introduction to the study, participants were informed that the current study was concerned with migration to the European context. Accordingly, although for example Poland is a member of the European Union, Poland has been a satellite-state to the Soviet Union, and thus has close historical ties to the old post-socialist reign, combined with extensive migration to western Europe.

Recruitment and participants

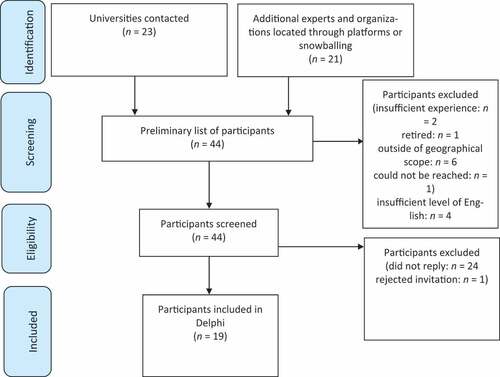

A Delphi study is based on expert assessments; thus, it was imperative to gather expertise on sport as a vehicle for social inclusion combined with CEE expertise. Additionally, an adequate level of English was mandatory to ensure smooth communication. Participants’ fit was based on their involvement in sport-for-change programmes/studies, experience of social inclusion practices in sport (e.g., publications, work, or others clarified by the expert). The study followed Powell’s (Citation2003) recommendation to strive for profession-wise heterogeneity in the Delphi-sample, to extract a range of perspectives. The sample ranged from CEE researchers, politicians to NGO representatives. The study followed local ethical guidelines, including confidentiality, informed consent, the right to quit whenever wished for and anonymity. No sensitive data was collected in the procedure. Initially, a list of CEE universities and already known sport scholars was created. Then, all relevant departments were contacted through email, stating the study purpose and details. The purpose of this email was to locate additional CEE scholars, connected to the wider field of sport for development (SfD); a field heavily concerned with sports as a means for social change and inclusion. Additionally, this procedure sought to extract information about locally based SfD NGOs and practitioners. The procedure is visualised in .

In the initial phases of recruitment, response rates were low, possibly due to language barriers. Such barriers could have eliminated potential participants who could have provided valuable information. Unfortunately, any CEE language was outside of the author’s knowledge. The number of experts included was adequate according to Delphi guidelines (Okoli and Pawlowski Citation2004). See for participant description.

Table 1. Description of participants.

Measurement

An online survey was constructed, consisting of 14 open-ended questions. The survey was discussed and revised through discussions between scholars at the institution and various SfD scholars. Finally, a version was sent to the Swedish Sports Confederation. The confederation scrutinised the questions to ensure they were appropriately constructed, keeping the sport practitioners in mind specifically. In this regard, the confederation has been involved in extensive research projects during the last decade, targeting Swedish sport practitioners. Upon final revisions, the questionnaire was translated to the participants’ native languages by an authorised professional translation agency. All participants were offered to choose the questionnaire in their native language or English and respond in whatever language they were comfortable with.

Procedure

The questionnaires were delivered through an online platform. The first round’s purpose was to identify benefits- and detriments due to sport participation for migrants. Secondly, the first round addressed how the experts worked with integration in sport, recruitment practices, and barriers and facilitators when integrating CEE migrants. Additionally, I asked how they defined integration through sport and whether there may be any salient differences in sport contexts/programme deliveries across the countries.

Data analysis

In the first round, the open-ended answers were thematically analysed, where items formed categories with varying broadness. The analysis was conducted with a (critical) realist-inspired approach to thematic analysis (for a full account of this procedure, see Wiltshire and Ronkainen Citation2021). The transcripts were analysed one by one. Nascent themes were elicited from the first transcript, and subsequent transcripts were deductively analysed. Novel themes were added as they were detected in subsequent transcripts. In operationalising the themes for the second round, they were subject to abstraction to create a conceptual framing at the backdrop of previous literature.

In the second round, these themes were formed into statements and rated from a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The analysis considered agree (6) and strongly agree (7) to count towards consensus. The final values are presented as aggregated percentages. Based on data from round two, statements were subject to redescription to consider their utility and coherence further. In the final round, the remaining items were again presented. Notably, this process was slightly different compared to traditional interviewing. Due to the Delphi method’s nature, the experts themselves were asked to contemplate the issues at hand. Thus, the process described is a collaborative activity to a higher degree, rather than exclusively relying on the researcher’s ability to interpret the respondent’s narratives.

Round 1 result

16 out of 19 experts finished the first round. The experts identified plenty of themes related to how sport can contribute towards integration, what factors hinder- or facilitate this, and potential specifics for CEE migrants. As the material was comprehensive, offers sample quotes of exemplifying themes.

Table 2. Sample quotes reflecting the content of round one.

Round 2

The same 16 experts completed round two. Out of 74 initial items, 30 reached the threshold for consensus. These are displayed in .

Table 3. Items reaching consensus.

The findings indicated sport’s psychosocial and socially cohesive effect and its implications for long-term outcomes. Experts concluded that the environment must be tolerant, culturally sensitive, inclusive, and characterised by trust. Moreover, organisational capacity was vital, along with collaborations with larger institutions. Barriers included extreme cultural differences, national policies that excluded migrants from sport spheres, financial- and physical proximity issues, and sport’s competitive nature. Importantly, experts concluded that CEE migrants often are used to organised sport and are well-travelled, thus making them more familiar with other cultures. However, it was also noted that CEE migrants are time-restricted because of labour. Finally, it was perceived as offensive to be unaware of CEE migrant’s specific origin because of sensitive Soviet history.

Round 3

15 out of 16 experts fulfilled the third round. Seven items made it above the threshold; see .

Table 4. Final items that reached consensus.

In this final round, experts consented to two mediated pathways to success through school/work. Furthermore, implications for ethnic minority sport clubs were highlighted, along with the need for active measurements taken within sport clubs. Finally, two barriers were highlighted, consisting of lacking language skills and social class.

Discussion

Following the assumption that sociohistorical and cultural factors mediate sport-for-integration, this paper presents preliminary results for CEE migrants. The findings relevant to both research questions will be discussed in relation to Bronfenbrenner’s two broad distinctions, the person, and the context. However, first, in defining what ‘integration’ entailed in sport, the experts highlighted the need for migrants to mix with the host population. Secondly, the experts believed that sport contributed to psychosocial health, social networks, job- and school success, cultural awareness, and social cohesion. The analysis starts from this understanding of integration. It should be acknowledged that this definition is reflective of the conceptual quagmire that is ‘integration’ – however, we can understand this from two perspectives, that were more salient than others; mere sport participation and the physical, mental, and social health that sport can bring about.

Person

Generally, migrants’ cultural backgrounds were given great weight in the data and perceived as a significant personal factor. Importantly, cultural background was also framed as a potential issue; if cultural distance was too great, this could alienate migrants from the majority population. This finding is perhaps most related to the literature on Muslim (women) and how the Muslim background is ascribed as the decisive factor when explaining low sport participation rates (Rozaitul et al. Citation2017). Like Ahmad et al. (Citation2020) explores, this is entangled into misconceptions about barriers to sport and stereotypical perceptions of Muslims. Personal resources that exacerbated this alienation was poor linguistic skills, which corroborate previous works (Anderson et al., Citation2019). However, open-mindedness was identified as a crucial mediator to the relationship between minorities and majority population. Morela et al. (Citation2021) have, for example, shown that the ability to understand the other in a sport-and-migration context is crucial for migrants’ inclusion and wellbeing.

The above taps into one finding identified as specific to CEE migrants. The notion of cultural awareness (and background) proliferated in the agreement regarding avoiding lumping CEE migrants together under the label ‘former Soviet residents’, i.e., a demand-factor. Just like stereotypical perceptions of Muslims are grounded in larger events, notably 9/11 (Rozaitul et al. Citation2017), other significant events ‘ are still feeding the perceptions of Western Europeans about CEE today’ (van Riemsdijk Citation2013, p. 378). These stereotypes are associated with the Soviet Union legacy, and (some) post-socialist migrants’ desire to distance themselves from it. For example, in Evans and Piggott’s (Citation2016) study, Lithuanian migrants took great pride in winning in basketball against Russia which was connected to Lithuania’s independence from the Soviet Union. This is consistent with research highlighting how CEE ethnic belonging is complex (Sasunkevich Citation2020) and how post-socialist states are in the process of constructing their post-Soviet identity (Bassin and Kelly Citation2012). This impact seems to trickle down to the individual level. Moreover, larger political events not only shape western perceptions of CEE migrants, but also shape CEE migrants trust against authorities, including sports organs (see quotes).

However, although previous research has largely centred on cultural diversity- and sensitivity, some results pointed to a shared European identity. Specifically, some beneficial personal resources were identified. CEE migrants were assumed to have at least shallow knowledge or previous experience of organised sport, which was framed as a beneficial resource considering the emphasis on organised sport in Europe. Since research on CEE migrants and sport is so scant, this can perhaps be best understood considering other groups’ issues when attempting to integrate into an organised European sport context. For example, in Sweden, Hertting and Karlefors (Citation2021) found that a salient issue was indeed the sport club structure, and that the bureaucracy was deemed too heavy to enable refugees’ inclusion adequately. On the contrary, the CEE regions have historically displayed strong sport performances, and have a solid tradition of organised sport. In fact, recent research, illuminating Ukrainian refugees’ inclusion into European sport clubs shows that sport club representatives generally express that Ukrainians seem to have an easier time integrating into the existing sport club compared to the population who arrived in 2015 and onwards, because of their acquaintance with organised sport (Blomqvist Mickelsson, Citationsubmitted)

In this regard, we may understand the experience and habitus of exercising organised sport as a culturally shaped, reproduced, and mediated practice. In accordance with Vélez-Agosto’s et al.’s (Citation2017) interpretation of culture, culture is embodied and expressed at the microlevel, and not something that ‘lingers’ in the macrosystem. The similarity between countries’ sporting structure, and thus individuals’ sporting experiences, potentially alleviates some of the organisational demand of sport clubs that engage with refugee initiatives (see e.g., Tuchel et al., Citation2021). Moreover, it is plausible that this similarity may play a cognitive factor; the adjustment process may not be as radical if one recognises the mode of sport delivery. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Carmi (Citation2017) analysed (post) Soviet migrant athletes’ integration into the sports community in Israel. Carmi (Citation2017) contends that, due to vastly different sporting cultures, these migrants formed their own communities. This discrepancy could mainly be traced to the value of sport in Soviet Union compared to Israel; sport was simply not valued very high in Israel at the time. Adding to this, was the assumed travelling experience of CEE migrants, which would indicate a high(er) degree of cultural awareness on behalf of the CEE migrants. All in all, these results are less conducive to the lenses of cultural sensitivity and safe-spaces, as they suggest that CEE migrants may more easily adjust to a European sport context because of their familiarity with this context- and sport structure.

Person to context – proximal processes

A plethora of contextual factors were identified, although most of them were generic and only two specific to CEE migration. These ranged between the organisational capacity necessary to recruit migrants to clubs, cultural education, open access, recruitment strategies to social inclusion policies, thus covering the full micro- to macro-spectrum. Two important proximal processes were identified.

The first entailed recruitment strategies, with components between the micro- to the exosystem. In conceptualising this proximal process, four agreements were considered. These were the agreements based on the importance of organisations engaging in trust-building with the migrant community, recruiting through established migrants, promoting the organisation (through professional migrant athletes) and collaboration with national bodies.

The actual proximal process occurs between the migrant and the club; in the case of CEE migrants, this can involve a certain sensitivity to the Soviet history, but also an understanding of how sporting structures in CEE regions are rather similar to the western European context. Yet, this is conditioned by the availability of collaborations and organisational strategies. Two interrelated factors that impinge upon recruitment strategies were identified as CEE-specific. First is the nature of migration for many CEE migrants, namely labour migration. Labour migration is characterised by its fluidity, where migrants stay for a limited or unclear duration of time (Favell Citation2008, Snel et al. Citation2015). CEE migrants are often associated to labour migration, and this has been given great attention in Europe (Czapka Citation2012, Friberg Citation2012a). The nature of labour migration poses a significant barrier towards recruitment, seeing as it may be difficult both logistically and emotionally to commit to a sport club. In turn, this impacts on trust-building which Jeanes et al. (Citation2019) show is essential to sport-programmes. The second interrelated factor highlighted how this impacts labour migrants’ leisure time. As explored by Stodolska and Jackson (Citation1998) in the US, Poles’ post-settlement leisure is affected by energy-draining labour, which has been corroborated in Norway where Polish construction workers are too tired or financially strained to engage in sport (Czapka Citation2012).

The second proximal process pertained to meaningful sport participation and concerned the relationship between the migrant and coach. The coach had to be culturally aware, which corroborates findings about coaches’ intentions to either accommodate for cultural diversity or assimilate migrants into existing sport structures (Mickelsson, Citation2022). The coach also had to display strong inter-personal- and organisational skills. The organisational skills included making sure that socialising opportunities were present, and to introduce the migrant to other societal spheres. Thus, the data reflects Luguetti et al.’s (Citation2022) conceptualisation of the coach as a ‘barrier breaker’; an empowering key person with in-depth understanding of one’s background, who continuously work in a multi-sectorial fashion (Jeanes et al. Citation2019).

Seeing as this relationship is essential, it is also worth noting that several experts highlighted that many clubs may not have the organisational capacity necessary to satisfy some of the suggestions (e.g., open access, staff capacity). Raw et al. (Citation2021) explored an SfD-programme and found that relational continuity and safety was essential to the programme. Incidents, such as staff leaving the programme, were major disruptions to this essential component. Such disruptions were acknowledged by the experts and highlights a central flaw in most European sport systems, where refugee projects are funded short-term and unsustainable (Lindström and Blomqvist Mickelsson, Citation2022).

Encapsulated in the relationship between migrant and coach is the final finding connected to ethnic minority sport clubs. Both pros and cons were considered here. While it was agreed that a blend of migrant- and majority population was optimal, experts did not immediately oppose ethnic minority sport clubs. Instead, they suggested that it could be a potential starting point. Research shows that ethnic minority sport clubs are influential and culturally safe arenas (Theeboom et al. Citation2012, Janssens and Verweel Citation2014) with implications for mental health (Walseth Citation2016). However, ethnic clubs face political opposition and are perceived as segregating, although these claims seem poorly substantiated (Janssens and Verweel Citation2014).

Some limitations should be addressed. Firstly, CEE migrants are not a homogenous group. There is cultural diversity within CEE migrants, affecting how sport is delivered for individuals within this categorisation. This categorisation was adopted from the UN’s definition of Eastern Europe. Similarly, the study did not make distinctions based on types of migration (e.g., forced, labour). This is a clearly important distinction in migration research, however, the study focused on teasing out unifying cultural patterns from the CEE regions. Organised sports are prevalent features in CEE regions, regardless of type of migration the individual experiences. Secondly, the Delphi study used questionnaires in the first round. Considering the complexity of the questions, some information may have been left out. While the experts did not receive any word limitation, the answers varied in their length. As the Delphi method is designed to quantify and elicit consensual information, it may struggle to respect all qualitative nuances. Finally, the study sample consisted of CEE sport experts, but never host country migration experts that could have provided more diverse, and (alternative) in-depth perspectives on the integration patterns of CEE migrants related to sport. Since integration generally is a two-way process, including both migrants and host society actors, there is a clear need to uncover how relevant host society actors perceive, act upon, and receive CEE migrants in the sports context. Accordingly, for a fuller understanding of synergies and divides between CEE migrants and western European sports contexts, knowledge from stakeholders, sports club representatives and other authorities engaged in migration questions should be elicited. This point is also important to consider since sports are not homogenously constructed throughout western Europe. Specifically, understanding how sports can be leveraged as a vehicle for migrants’ integration is contingent on a thorough understanding of specific sports movements’ structure, bureaucracy and its associated limitations and possibilities (see e.g., Hertting and Karlefors Citation2021).

Conclusions

CEE migrants face similar and unique obstacles compared to other groups. Lacking resources, language skills and capital in various forms are generic factors which prevents anyone to partake in sport. Yet, some factors seem to appeal more (and others less) to CEE migrants. Sport practitioners who are currently working with CEE migration, notably with Ukrainian refugees, must understand that these refugees come from other (sport) contexts compared to the previous refugee populations in Europe. In short, CEE migrants’ experiences in home countries, their proximity to Europe and perhaps travel experience suggest that CEE migrants will be, broadly, familiar with exerting organised sport in the European format. Sport practitioners may also need to pay attention to current and past events in CEE history. This is important, so that for example Ukrainian refugees’ feelings towards Russia, and how current events have shattered entire families, are being treated with dignity. The Ukraine – Russia conflict paints a painstakingly clear example of such, however, other (less known) conflicts have also erupted in adjacent regions to CEE, such as the events in the Nagorno-Karabakh. However, what the entirety of the findings suggest is that, instead of focusing on cultural sensitivity, sport practitioners might be better off primarily focusing their efforts on, e.g., socioeconomic aspects of CEE migration, while, clearly, being in-tune with current political events and debates.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all participants involved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agergaard, S., 2018. Rethinking sports and integration: developing a transnational perspective on migrants and descendants in sports. Rethinking Sports and Integration: Developing a Transnational Perspective on Migrants and Descendants in Sports, 2 (1), 1–116. doi:10.4324/9781315266084

- Ahmad, N., et al. 2020. Building cultural diversity in sport: a critical dialogue with Muslim women and sports facilitators. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics. Taylor & Francis, 12 (4), 637–653. doi:10.1080/19406940.2020.1827006

- Anderson, A., et al., 2019. Managerial perceptions of factors affecting the design and delivery of sport for health programs for refugee populations. Sport Management Review. Sport Management Association of Australia and New Zealand, 22 (1), 80–95. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.015

- Bassin, M. and Kelly, C., 2012. Soviet and post-Soviet identities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blanchflower, D.G., Saleheen, J., and Shadforth, C. 2007. The impact of the recent migration from Eastern Europe on the UK economy. IZA Discussion Paper, No. 2615.

- Blomqvist T Mickelsson., 2022. The role of the Swedish Sports Confederation in delivering sport in socioeconomically deprived areas. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 14 (4), 589–606. doi:10.1080/19406940.2022.2112260

- Blomqvist Mickelsson, Tony. Submitted. Ukrainian refugees in the Swedish sports movement - challenges and opportunities.

- Bronfenbrenner, U.,1977. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American psychologist. American Psychological Association, 32 (7), 513.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Handbook of child psychology (5th ed., pp. 993–1023). New York: Wiley.

- Burrell, K., 2010. Staying, returning, working and living: key themes in current academic research undertaken in the UK on migration movements from Eastern Europe. Social Identities. Taylor & Francis, 16 (3), 297–308. doi:10.1080/13504630.2010.482401

- Byrska, O., 2022. Civil crisis management in Poland: the first weeks of the relief in Russian war on Ukraine. Journal of Genocide Research, 1–8.

- Carmi, U., 2017. Absorbing coaches and athletes from the former soviet union in Israel. International Journal of the History of Sport, 34 (16), 1719–1738. doi:10.1080/09523367.2018.1491553

- Coalter, F. 2013. Sport for Development: What Game Are We Playing? London: Routledge.

- Cubizolles, S., 2015. Sport and social cohesion in a provincial town in South Africa: the case of a tourism project for aid and social development through football. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50 (1), 22–44. doi:10.1177/1012690212469190

- Czapka, E., 2012. ‘The health of new labour migrants: polish migrants in Norway’, in Health inequalities and risk factors among migrants and ethnic minorities. Antwerp: Garant, 150–162.

- Dalkey, N., Brown, B., and Cochran, S., 1970. Use of self-ratings to improve group estimates: experimental evaluation of Delphi procedures. Technological Forecasting. Elsevier, 1 (3), 283–291. doi:10.1016/0099-3964(70)90029-3

- Dalkey, N. and Helmer, O., 1963. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management science. INFORMS, 9 (3), 458–467.

- De Bock, T., 2021. Sport-for-All policies in sport federations: an institutional theory perspective. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1–23.

- Dickson, T.J. and Darcy, S., 2021. A question of time: a brief systematic review and temporal extension of the socioecological framework as applied in sport and physical activity. Translational Sports Medicine. Wiley Online Library, 4 (2), 163–173. doi:10.1002/tsm2.203

- DiSanti, J.S. and Erickson, K., 2020.Challenging our understanding of youth sport specialization: an examination and critique of the literature through the lens of Bronfenbrenner’s Person-Process-Context-Time Model. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–23.

- Doidge, M., Keech, M., and Sandri, E., 2020. “Active integration”: sport clubs taking an active role in the integration of refugees. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12 (2), 305–319. doi:10.1080/19406940.2020.1717580

- Dowling, F., 2020. A critical discourse analysis of a local enactment of sport for integration policy: helping young refugees or self-help for voluntary sports clubs? International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 55 (8), 1152–1166. doi:10.1177/1012690219874437

- Dukic, D., McDonald, B., and Spaaij, R., 2017. Being able to play: experiences of social inclusion and exclusion within a football team of people seeking asylum. Social Inclusion, 5 (2PracticeandResearch), 101–110. doi:10.17645/si.v5i2.892

- Edelman, R., & Wilson, W., 2017. The Oxford Handbook of Sports History. Oxford University Press.

- Evans, A.B. and Piggott, D., 2016. Shooting for Lithuania: migration, national identity and men’s basketball in the East of England. Sociology of Sport Journal, 33 (1), 26–38. doi:10.1123/ssj.2015-0028

- Favell, A., 2008. The new face of East–West migration in Europe. Journal of ethnic and migration studies. Taylor & Francis, 34 (5), 701–716. doi:10.1080/13691830802105947

- Fox, J.E., Moroşanu, L., and Szilassy, E., 2015. Denying discrimination: status,“race”, and the whitening of Britain’s new Europeans. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Taylor & Francis, 41 (5), 729–748. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.962491

- Friberg, J.H., 2012a. Culture at work: polish migrants in the ethnic division of labour on Norwegian construction sites. Ethnic and Racial Studies. Taylor & Francis, 35 (11), 1914–1933. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.605456

- Friberg, J.H., 2012b. The stages of migration. From going abroad to settling down: post-accession Polish migrant workers in Norway. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Taylor & Francis, 38 (10), 1589–1605. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2012.711055

- Hertting, K. and Karlefors, I., 2021. “we Can’t Get Stuck in Old Ways”: Swedish Sports Club’s Integration Efforts with Children and Youth in Migration. Physical Culture and Sport, Studies and Research, 92 (1), 32–42. doi:10.2478/pcssr-2021-0023

- Hsu, -C.-C. and Sandford, B.A., 2007. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 12 (1), 10.

- Janssens, J. and Verweel, P., 2014. The significance of sports clubs within multicultural society. On the accumulation of social capital by migrants in culturally “mixed” and “separate” sports clubs. European Journal for Sport and Society, 11 (1), 35–58. doi:10.1080/16138171.2014.11687932

- Jeanes, R., et al., 2019. Coaches as boundary spanners? Conceptualising the role of the coach in sport and social policy programmes. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 11 (3), 433–446. doi:10.1080/19406940.2018.1555181

- Koopmans, B. and Doidge, M., 2022. “They play together, they laugh together’: sport, play and fun in refugee sport projects. Sport in Society. Taylor & Francis, 25 (3), 537–550.

- Krouwel, A., et al., 2006. A good sport?: research into the capacity of recreational sport to integrate Dutch minorities. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 41 (2), 165–180. doi:10.1177/1012690206075419

- Ley, C., et al., 2017. Exploring flow in sport and exercise therapy with war and torture survivors. Mental Health and Physical Activity. Elsevier, 12, 83–93. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2017.03.002

- Ley, C., et al. 2022. Health, integration and agency: sport participation experiences of asylum seekers. Journal of Refugee Studies. Oxford Academic, 34 (4), 4140–4160. doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa081

- Lindström, J., Blomqvist Mickelsson, T., 2022 .En match utÖver det vanliga: Om ett kunskapsbaserat arbetssätt i idrottssvaga omräden [a game beyond the usual: about an evidence-based way of working in areas with weak sport infrastructure]. Stockholm: Riksidrottsförbundet.

- Long, J. and Hylton, K., 2002. Shades of white: an examination of whiteness in sport. Leisure studies. Taylor & Francis, 21 (2), 87–103.

- Luguetti C, Singehebhuye L and Spaaij R., 2022. Towards a culturally relevant sport pedagogy: lessons learned from African Australian refugee-background coaches in grassroots football. Sport, Education and Society, 27(4), 449–461. doi:10.1080/13573322.2020.1865905

- Mickelsson T Blomqvist., 2021. Towards Understanding Post-Socialist Migrants’ Access to Physical Activity in the Nordic Region: A Critical Realist Integrative Review. Social Sciences, 10(12), 452. doi:10.3390/socsci10120452

- Mickelsson T Blomqvist., 2022. Facilitating migrant youths’ inclusion into Swedish sport clubs in underserved areas. Nordic Social Work Research, 1–15. doi:10.1080/2156857X.2022.2155218

- Mickelsson T Blomqvist., 2022. A morphogenetic approach to sport and social inclusion: a case study of good will’s reproductive power. Sport in Society, 1–17. doi:10.1080/17430437.2022.2069013

- Mohammadi, S., 2019. Social inclusion of newly arrived female asylum seekers and refugees through a community sport initiative: the case of Bike Bridge. Sport in Society. Taylor & Francis, 22 (6), 1082–1099.

- Montayre, J., et al., 2020. What makes community-based physical activity programs for culturally and linguistically diverse older adults effective? A systematic review. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 39 (4), 331–340. doi:10.1111/ajag.12815

- Morela, E., et al. 2021. Youth sport motivational climate and attitudes toward migrants’ acculturation: the role of empathy and altruism. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. Wiley Online Library, 51 (1), 32–41. doi:10.1111/jasp.12713

- Nowy, T., Feiler, S., and Breuer, C., 2020. Investigating Grassroots Sports’ Engagement for Refugees: evidence From Voluntary Sports Clubs in Germany. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 44 (1), 22–46. doi:10.1177/0193723519875889

- Okoli, C. and Pawlowski, S.D., 2004. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Information and Management, 42 (1), 15–29. doi:10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002

- Olliff, L., 2008. Playing for the future: the role of sport and recreation in supporting refugee young people to’settle well’in Australia. Youth Studies Australia, 27 (1), 52–60.

- Powell, C., 2003. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. Journal of advanced nursing. Wiley Online Library, 41 (4), 376–382. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x

- Raw, K., et al., 2021. Safety and relational continuity in sport for development with marginalized young people. Journal of Sport Management. Human Kinetics, 1 (aop), 1–14.

- Rozaitul, M., Dashper, K., and Fletcher, T., 2017. Gender justice?: muslim women’s experiences of sport and physical activity in the UK. In: J. Long, T. Fletcher, B. Watson, eds. Sport, leisure and social justice. London: Routledge, 70–83.

- Sasunkevich, O., 2020. (Un) doing Polishness: Negotiation of Ethnic Belonging in Personal Narratives about Karta Polaka. East European Politics and Societies, 35 (3), 661–681.

- Schaillée, H., Haudenhuyse, R., and Bradt, L., 2019. Community sport and social inclusion: international perspectives. Sport in Society. Taylor & Francis, 22 (6), 885–896.

- Skille, E.Å., 2010. Competitiveness and health: the work of sport clubs as seen by sport clubs representatives - a Norwegian case study. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 45 (1), 73–85. doi:10.1177/1012690209352395

- Snel, E., Faber, M., and Engbersen, G., 2015. To stay or return? Explaining return intentions of Central and Eastern European labour migrants. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 4 (2), 5–24.

- Spaaij, R., 2012. Beyond the playing field: experiences of sport, social capital, and integration among Somalis in Australia. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35 (9), 1519–1538. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.592205

- Spaaij, R., Knoppers, A., and Jeanes, R., 2020. “We want more diversity but ”: resisting diversity in recreational sports clubs’. Sport Management Review. Elsevier, 23 (3), 363–373. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2019.05.007

- Spaaij R and Schulenkorf N., 2014. Cultivating Safe Space: Lessons for Sport-for-Development Projects and Events. Journal of Sport Management, 28 (6), 633–645. doi:10.1123/jsm.2013-0304

- Stenling, C., 2015. Umeå: Umeå University.

- Stodolska M and Jackson E L., 1998. Discrimination in Leisure and Work Experienced by a White Ethnic Minority Group. Journal of Leisure Research, 30 (1), 23–46. doi:10.1080/00222216.1998.11949817

- Stura, C., 2019. “What makes us strong”–the role of sports clubs in facilitating integration of refugees. European Journal for Sport and Society, 16 (2), 128–145. doi:10.1080/16138171.2019.1625584

- Symons, J., 2021. Shared experiences from the margins: culturally diverse women in coaching in aotearoa New Zealand, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In: L. Norman, ed. Improving Gender Equity in Sports Coaching. New York: Routledge, 159–176.

- Theeboom, M., Schaillée, H., and Nols, Z., 2012. Social capital development among ethnic minorities in mixed and separate sport clubs. International Journal of Sport Policy, 4 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/19406940.2011.627359

- Tishkov, V., Zayinchkovskaya, Z., and Vitkovskaya, G., 2005. Migration in the countries of the former Soviet Union. Global Commission on International Migration, 1–42 .

- Tuchel, J., et al., 2021. Practices of German voluntary sports clubs to include refugees. Sport in Society. Taylor & Francis, 24 (4), 670–692.

- UNHCR., 2022. Situation Ukraine Refugee Situation. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine [Accessed 1 June 2022].

- van Riemsdijk, M., 2013. Everyday geopolitics, the valuation of labour and the socio-political hierarchies of skill: polish nurses in Norway. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Taylor & Francis, 39 (3), 373–390. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.733859

- Vélez-Agosto, N.M., 2017. Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory revision: Moving culture from the macro into the micro. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12 (5), 900–910.

- Walseth, K., 2015. Muslim girls’ experiences in physical education in Norway: what role does religiosity play? Sport, Education and Society, 20 (3), 304–322. doi:10.1080/13573322.2013.769946

- Walseth, K., 2016. Sport within Muslim organizations in Norway: ethnic segregated activities as arena for integration. Leisure Studies, 35 (1), 78–99. doi:10.1080/02614367.2015.1055293

- Wiltshire, G. and Ronkainen, N., 2021. A realist approach to thematic analysis: making sense of qualitative data through experiential, inferential and dispositional themes. Journal of Critical Realism. Taylor & Francis, 20 (2), 159–180. doi:10.1080/14767430.2021.1894909