ABSTRACT

Globally, governments are implementing public sector reform to address declining budgets and public trust to improve programme efficiency and effectiveness. Sport has become ever more relevant with regards local, national and international social policy as part of an enhanced role for the third sector in tackling a plethora of societal issues. This article attempts to explore, the success (or otherwise) of sport for development (SfD) programmes transitioning positive outcomes from a micro and meso level to the macro level in Northern Ireland. Three management models (Outcomes-based accountability, Organisational capacity and Resource dependency theory) are used to establish the level of efficiency and effectiveness of SfD programmes in Northern Ireland, based on semi-structured interviews with a range of policy and delivery stakeholders. This article identifies potential areas of conflict at the intersection between policy and practice which limit the translation of successful project outcomes. The ambiguity of purpose combined with the absence of a population level evaluation model and financial reliance perpetuates task-based projects at the expense of sectoral outcomes. In turn, individuals are faced with a ridged multi-agency offering without a multi-agency approach. This article recommends a government-wide indicator for sport and physical activity linked to an overarching sport-related strategy, which clearly defines language, purpose and responsibilities across the public sector. One which builds on existing structures to support transition (individual and organisational) across the three identified interlinking phases of sport.

Introduction

The modernisation of the public sector at a time of austerity has caused governments to consider how public services are delivered introducing comprehensive public sector reforms (Elcock et al. Citation2010) and cost-cutting measures (Durose et al. Citation2015). In the UK, this resulted in the reconfiguration – or in other cases the closure – of some public bodies. Austerity provides the stimulus for the implementation of new public management (NPM) within government (Heald and Steel Citation2018).

The overarching public sector framework prioritises accountability through annual departmental monitoring and value for money criteria (Adams and Harris Citation2014). The search for innovation to improve accountability and governance (Lapsley and Miller Citation2019) within the UK public sector led to the creation of numerous public–private partnerships (Lobao et al. Citation2018), the prioritisation of evidenced based policy (Lindsey and Bacon Citation2016) and a more visible role for the third sector in public sector delivery (Bush and Houston Citation2011).

This study will use the unique setting of Northern Ireland (NI), a post conflict – and still divided society – which remains part of the United Kingdom governed through a mandatory coalition (Rhodes et al. Citation2003) and influenced (to varying degrees) by five layers of governance across the UK, Ireland and Europe. The signing of the Belfast Agreement (1998) brought relative peace to NI and signalled the creation of a range of new policies and political structures (Birrell and Gormley-Heenan Citation2015). Although welcomed by many, Bairner (Citation2013) among others was critical of the ambiguities in the Agreement design referring to this as a consociational settlement. These perceived contradictions which made the Agreement possible in the first place (Ruane and Todd Citation2003) also made it difficult to implement. Nevertheless, division continues to leave a mark on life today prolonging a legacy of mistrust; shaped by ethnicity, religion, social and geographical separation (Hassan and Ferguson Citation2019).

Segregated schooling and community planning are evident in the location of housing, transport links and entertainment venues. A polarisation which has left significant challenges for policymakers (Byrne et al. Citation2015:3), who attempt to balance equitable community access against duplicated services and inefficiency, while implementing ideological shifts in focus directed by the two main parties (Sinn Fein and the DUP) between economic development and social inclusion. As a result, safeguards were built into government through three functions: Executive, Legislative and Scrutiny. The functions are designed to mitigate against discrimination using ethnic vetoes and ministry committees to facilitate collective representation (mandatory coalition) and inclusion (Knox Citation2015).

As a means of tackling perceived inefficiencies in the public sector, an outcomes-based approach has been adopted in NI – replicating the approach introduced by a number of western countries – to promote collaborative practice by prioritising broad outcomes over departmental outputs. This approach has corresponded with a substantial increase in public sector funding for sport for development (SfD) projects (Houlihan and Lindsey Citation2013) emerging from a range of sources, tasked with contributing to governmental outcomes.

This study will focus specifically on organisations involved in promoting sport for development and peace (SfD&P) and those targeting the inclusion of underrepresented groups (disability, social need, women and girls and ethnic minorities).

Sporting organisations in NI have played an active role in local communities (Hassan and Telford Citation2014). The last 20 years has witnessed extensive community sport outreach designed principally to attract participants from across the religious divide who otherwise would not have taken part in these sporting activities (Mitchell et al. Citation2016). Therefore, the increasing use of public funding to deliver SfD programmes requires programme leaders to expand activities across multi-disciplinary boundaries while demonstrating reach and value, leading some to justify programmes post hoc in the name of social change (Adams and Harris Citation2014).

More broadly, criticism that the public sector system is based on a partnership ethos which values consensus – rather than tackling conceptual difference – may lead to silos and dysfunctionality in joined up government (Davies Citation2009). These difficulties in design and implementation of policies negatively impact cohesion (Christensen and Lægreid Citation2007); perpetuated by methodological struggles (Lindsey and Bacon Citation2016) evident across the SfD sector in evaluation impact.

Across the UK, strategic planning in the public sector has been recognised as problematic (Joyce Citation2015) due to the complexity of competing and contrasting agendas. The situation heightened during times of austerity whereby, constraints require difficult decisions to be made surrounding essential services. In these circumstances, sport must compete with other services to demonstrate value and impact across a range of agendas. As such, ‘neoliberalism, as an ideology; new public management (NPM) as a mode of governance; and modernisation as a policy package, provide the architecture that enables and controls the contexts and frameworks within which SfD operates’ (Adams and Harris Citation2014, p. 141).

Specifically, this study explores the implications of introducing Outcomes-Based Accountability (OBA) to public sector SfD&P and is relevant to both policymakers and those delivering projects to enhance cohesion, offering insight into how best to obtain improved sectoral accountability and effectiveness.

The debate contained therein explores the reliance of sporting organisations on public sector funding and the growing dependence of government on third parties to deliver its agenda through SfD&P. Consideration is given to scholars who caution against the lack of research to support sports use, claiming such a tactic is in direct contradiction to the public sector evidence-based approach that has become common practice over recent years (Kidd Citation2008, Adams and Harris Citation2014). This study further explores the level of understanding and cohesion across the sector to establish the connections within and across organisations involved in strategic leadership and operational delivery which is deemed vital to successful development (Friedman Citation2015, Corvino et al. Citation2022), the conclusions of which will offer guidance in building a sustainable SfD sector.

In 2022, the departmental Sport strategy in NI was updated, expanding the remit to include physical activity. Recently, Scotland moved beyond a departmental sport strategy to introduce a government-wide ‘Active Scotland’ strategy whereby all departments have contributing responsibilities. Sport is seen as one element of the strategy; this sport-specific element is led by Sport Scotland, established around aligned outcomes rather than outputs. Therefore, a clear collaborative approach using common language can be mapped towards the overarching government outcomes agenda. Scottish government indicators provide a framework to measure success (or otherwise) providing tangible evidence of contributions towards agreed population outcomes in sport and activity. On a broader level, agreed indicators can offer clarity as evidenced within the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals, providing a mechanism to promote cohesion across global development efforts by establishing goals accompanied by concrete indicators for guidance and measurement. The subsequent introduction of the UN Sustainable Coordination Framework attempts to further build coherence and empower stakeholders by offering guidance throughout the entire programme cycle. In essence, promoting synergies between different policies has the potential to broaden understanding (Knoll Citation2014), enabling the illustration of the intersections between sport and the broader political agenda (Lindsey and Darby Citation2019).

This article will examine the conditions which either promote or restrict the effective transfer of programme success to the macro level by exploring intersections between policy, community and the individual relevant to SfD&P. In particular, the following three questions are posed guided by sub-indictors:

What supports the transition of process and individual outcomes across the micro, meso and macro levels?

The alignment between top-down policy and bottom-up practice.

What was achieved, how was it achieved and what impacts were generated?

The level of cohesiveness across the structures which oversee and deliver SfD&P activity in NI;

What is the impact of modernisation in the public sector on SfD&P in NI?

The capacity and dependency evident at policy and delivery level.

Methods

In framing this study, the sporting and social context in NI (a post-conflict country in Western Europe) were used to inform the methodological structure. In particular, the assumption that sport is neither good nor bad but rather a social construct; its role dependent on its purpose and how it is received (Sugden Citation2005). The phenomenologist approach acknowledges that experiences are formed in unique ways subject to social contexts and personal beliefs (Höglund and Sundberg Citation2008). In NI, the influence of relationships, society and policy from deep-rooted social and political identities (Hassan and Ferguson Citation2019) can be seen to generate what Muldoon (2007:90) described as ‘negative interdependence’ whereby, any change results in the perception of increased status to one group and as a loss to the other. Consequently, consideration is given to what is said and how it is said alongside, the context within which any stakeholder operates.

The main components of this study have been reviewed via the relevant Research Ethics Committee to ensure that all elements of the research study were conducted appropriately adhering to the highest ethical standards. The methodology aligns theoretical direction obtained through the inclusion of management models. In particular, outcomes-based accountability (OBA) (Friedman Citation2015), organisational capacity (OC) (Hall et al. Citation2003) and resource dependency theory (RDT) (Pfeffer and Salancik Citation1978) are applied to explore the effectiveness of sectoral transition across micro, meso and macro environments. Previous work by Ferguson et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated the need for research which explores the effectiveness of cross-sectoral cooperation and performance to better understand issues involved in creating, delivering, and evaluating multi-agenda sport projects.

OBA is the model recently adopted for public sector measurement in many western countries including NI and is therefore, relevant to any study related to public sector outcomes in NI. Nevertheless, issues of academic validity have been raised regarding Friedman’s model (Gray and Birrell Citation2018). As a result, RDT is adopted to investigate power, dependence, autonomy and constraint to ultimately determine the independences and imbalances created between organisations. RDT, however, ignores the potential for two-way dependence; therefore, OC is included within the approach. Combining these three existing models in this way enables exploration of both organisational performance and sectoral impact. Adopting alternative approaches emerging from related disciplines offers benefits to SfD research (Schulenkorf et al. Citation2016)in this case, based on the assumption that greater understanding of an organisation's capacity to achieve government objectives (Fowler Citation2013) will in the future support sector-wide progression. Previously, scholars have explored the impact of interconnections across different development agendas (Lyndsay and Darby Citation2018) while recognising both evidence-based approaches and structural constraints (Darnell et al. Citation2018a) to determine the relevance of government targets and indicators (Hák et al. Citation2016).

Purposeful sampling was used to select participants for this study to ensure representation from key stakeholders involved in the sector, creating a holistic understanding of the situation under review and capturing the uniqueness of the contextual situation from the view of those involved (Neuman Citation2013). The importance of purposeful sampling as a suitable method to research SfD projects within divided societies was further endorsed by Sugden (Citation2006).

Semi-structured interviews (n = 39: aged range 26–60; 35 males, 4 females) were designed to facilitate a conversation inclusive of generic themes within the SfD&P environment; progressing to more specific topics which provided opportunity to refine responses. The approach allowing the exploration of both programme performance and the broader sectoral situation from the viewpoint of delivery agents and policymakers. This process attempted to connect ‘top-down’ and bottom-up’ opinion to interpret the level of effectiveness and efficiency at the sectoral level in NI.

The close link between sport and politics in NI (Sugden Citation1991) places pressures on stakeholders with regards publication of their opinions particularly, related to the more contentious topics explored within this article. This pressure is further perpetuated by the sectoral reliance on public sector funding and the potential for non-evidence-based ideological decisions by ministers in NI (Birrell and Gormley-Heenan 2015, Birrell Citation2014, Wilford and Wilson Citation2006). All of which creates a dilemma for delivery agents as they attempt to be all things to all people (Coalter Citation2007). To safeguard respondents and to promote open dialogue, interview respondents’ personal details were anonymised with each respondent given a numeric identifier. A cross section of stakeholders was engaged, representing those organisations who over a sustained period (minimum 10 years) have held leadership roles primarily focused on organised sport with SfD&P targets (DA1), focused on development and use sport as a vehicle to engage (DA2) and those deemed specialist in SfD&P (DA3) alongside those involved in funding and governance of sport (policymakers) across the public sector. The societal division manifested across NI is reflected in the experiences of all stakeholders who have to varying degrees used sport to engage with underrepresented groups; build inclusion; tackle discrimination and change behaviours. Respondents were based primarily in single identity (10) or cross community locations (29). The importance of engaging both grassroots groups and policymakers is vital to garner a deeper understanding of the if’s, how’s, and why’s of approaches to integrate governmental policy (McSweeney et al. Citation2021). Interviews lasted between 48 and 97 minutes, with notes transcribed and a summary of key points provided to each individual to review and check accuracy and authenticity (Norris Citation1997).

Data analysis

This article takes a broader view of the SfD sector developed through deductive research led thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) which was directed to explore existing concepts and address issues of communications, organisational capacity, collaborations and leadership.

Having generated the data, Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step procedure for thematic analysis was used to ensure a rigorous, deliberate and reflexive process of data analysis. The analysis was set against the influencing factors within a complex environment which may have motivated individual responses. Thereby, blending phenomenology as a means of contextualising lived experience in the wider social perspective based on the researcher’s contextual knowledge.

Findings and discussion

Three themes were drawn from stakeholder interviews informed by research in the field. Two themes were linked to strategic direction: Purpose and Sustainability and the other linked to operational delivery: Collaboration and Capacity. These themes identified in are explored further, to determine the state of the SfD&P environment and the conditions necessary for future transitional success.

Table 1. Thematic analysis state of the sector.

Purpose

The first theme was categorised by a lack of clarity with regards common sectoral purpose for those involved in SfD&P activity. Two delivery agents summarising the issue as,

there appear to be artificial boundaries between strategy and operations which might be good governance but are negatively impacting understanding (Interview with DA3 18 April 2018).

‘a fear of defining things’ raising conflict in terms of overlap and coexistence (Interview with DA2 15 Feb 2018).

The comments suggest the administrative project focus, combined with a lack of clarity of vision, limits understanding of the sectoral potential (population level), resulting in missed strategic opportunities. The issues remained similar when viewed across projects targeting single identity or cross-community objectives. The importance of clarity of purpose to understand ‘WHY’ an organisation or sector do what they do has been previously articulated (Sinek Citation2011) as a means to, build trust and promote stakeholder buy-in, a key element of successful SfD&P projects (Sugden Citation2018).

The application of OBA (Friedman Citation2015) identifies the importance of carrying out an initial needs analysis to promote understanding of the issues and establish defined roles and responsibilities for all stakeholders at a micro, meso and macro level. The development of local collaborations was discussed by one delivery agent who suggested,

When working collaboratively it is important to understand each other, define roles and build trust, then work to maximise the collaboration, we (community groups) have a good understanding of local needs (interview with DA3 30 Jan 2018).

The comment suggests a level of understanding at the micro and meso level, which is not evident at the macro level. One stakeholder highlighted how funding restricts organisations from engaging in this practice at a macro level,

Funders need to clearly think of the difference they want to make. Some funders don’t appear to know what difference they want to make or what difference they can make. (interview with DA3 30 January 2018).

This statement draws into question the potential for effective outcomes through sport and in doing so supports the caution raised by scholars, who suggest that a lack of understanding (perpetuated due to modernisation) places pressure on delivery agents to straddle institutional boundaries while providing evidence of both programme development and outcomes with no clear strategic direction or agreed operating model (Adams and Harris Citation2014). The impact of which was underlined by a delivery agent,

Funders work in silos, there is no joined up thinking. We have funding from a number of sources, sometimes even different programmes from the same funder and they have different monitoring. There needs to be a sophistication to the monitoring (interview with DA 1 24 May 2018).

The absence of a specific SfD framework has negatively impacted efficiency across the sector, by increasing the administrative burden on sporting organisations to report across multiple monitoring systems while at the same time generating their own evidence to demonstrate value. This point was made by a stakeholder who suggested,

the grant system for sport is broke, its complex, requires experts … … those who know the right people have an advantage to influence, access to those people is not equal (interview with DA1 25 April 2018).

This comment further reflects the struggle with existing evaluation methodologies which are sensitive to the tensions between efficiency and effectiveness (Bush and Houston Citation2011) but actively promote the importance of cost recovery and efficiency (Darnell et al. Citation2018a) with political considerations embedded within monitoring models. This is of particular concern in a post-conflict country due to the potential for non-evidence-based ideological decisions by ministers (Birrell and Gormley-Heenan 2015, Birrell Citation2014). There remains little evidence of cross-funder collaboration as a means of generating mutual benefit towards agreed outcomes at a macro level.

Across NI, numerous funds support SfD&P activity with varying objectives. This led one delivery agent to note that there is,

A spectrum within sport beginner to elite, participation to personal development there is so many things sport is covering (Interview with DA1 24th May 2018).

The differing agendas contribute to competing targets further diluting cohesiveness. Consequently, the issues raised by Bogdanor (Citation2005) – who suggested where you stand depends on where you sit – implies different departments view the same issue from different perspectives thus, endorsing the need for clarity of purpose and needs analysis noted previously. Indeed, whereas the perceptions of sport and how it is consumed have changed in recent years, public policy on sport remained static (Matters Citation2009-21). Further evidence of what has been described as a lack of theoretical and practical acumen concerning how change is realised, which leads to outcome indicators that lack validity and reliability (Adams and Harris Citation2014).

Uncertainty

The first subordinate theme of purpose is hampered by the uncertainty regarding the sectoral objective. Propagated by the cross-cutting nature of sport, which spreads its use across a variety of government outcome agendas, the quote below highlights the potential for misalignment at an operational and strategic level.

The word sport has so many connotations that maybe the word sport is the issue or more education is needed (interview with DA3 30th January 2018).

This comment is reflective of the ambiguity surrounding many SfD initiatives (Coalter Citation2007), which results in the setting of differing definitions, methodologies and targets to address the same issue (Adams and Harris Citation2014). At an organisation level, scholars caution against the dangers for organisations of attempting to be ‘all things to all people’ by expanding activities across multi-disciplinary boundaries and justifying programmes post hoc in the name of social change’ (Adams and Harris Citation2014).

At a delivery level, one stakeholder explained,

Sports role and where it sits is unclear … . Fluidity in sport is ok … . however, it’s about the purpose (18 April 2018).

The clarification in the statement above reinforces that sports participation, sports performance and SfD&P are explicitly different. The context is different, the objectives are different, the staff skills are different, and the risks are different (Coalter Citation2007). As such, there needs to be clarity of purpose and direction at both strategic and operational level. A point endorsed by a further stakeholder who commented,

There is an issue around language government and sports governing bodies talk in a different language. (Interview with DA1 7 June 2018).

In these circumstances, projects may be duplicated and potentially restricted, which negatively impacts effectiveness and efficiency. Indeed, without an agreed purpose and common language, sport may continue to be influenced by differing strategic objectives across a range of government departments, with project-based activity attempting to deliver against a range of diverse outcomes. As noted clearly by one delivery agent,

Sporting groups have to change their language to ensure government groups understand how they are achieving against various outcomes (Interview with DA3 18 April 2018).

The comment pointing to the need for evidence to recognise the value of sport and thus enable bottom-up influence.

Conflict

The lack of clarity previously noted can cause conflict as suggested by a delivery agent,

It’s confusing using terms such as sports development and sport for development. The word sport has a tradition attached to it that generates many thoughts (interview with DA3 18th April 2018).

It was in a similar context – with limited direction and no definitive parameters from which to operate that Spaaij et al. (Citation2014) highlighted the potential discrepancies between policy objectives and how these were operationalised by sporting groups, potentially increasing the likelihood of both duplication and political manipulation. In essence, the picture presented mirrors Kidd and MacDonnell (Citation2007) findings who concluded that the SfD field was unregulated, poorly planned and uncoordinated. In these circumstances setting and agreeing indicators leave room for individual subjective perception which will ultimately quantify impact (Lombardo et al. Citation2019) leading to misunderstanding and misapplication of the measurement indicators (Chen Citation2018). Agreeing common indicators for measuring contribution to specific targets can be used as a mechanism to mobilise stakeholders and build relevant partnerships rather than see policy neglected (Morgan et al. Citation2021) thus addressing the concern raised earlier in this article.

Capacity and collaboration

For those involved in delivering SfD&P activities there appear to be three structures,

Organisations make a conscious decision regarding their purpose either at an organisation or project level … . Some organisations are clear sport for social change. Others sports development through organised sport. Others straddle both, … . but they also make a conscious decision to run sport for target social change (interview with DA3 18th April 2018).

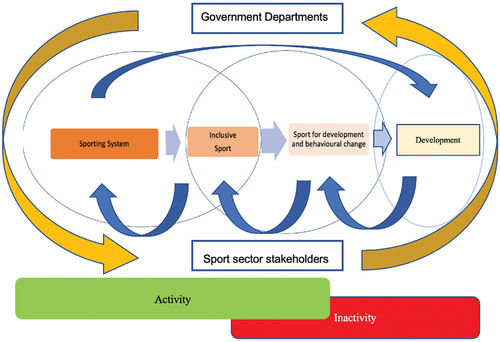

The discussion points to an evolving sporting landscape () reflective of the expanding public sector funding for SfD&P activity, coinciding with substantially reduced funding for transitional SD activity (Sport Citation2017). Constructed with three overlapping elements, definition of these elements may promote understanding at the transition points and reduce the uncertainty discussed previously related to language and purpose. 1. The Sports System recognised as participation in organised sport extending to elite performance; 2. Inclusive Sport which use targeted generic interventions to promote pathway opportunities in sport by breaking down barriers to access for underrepresented groups to transition into the sporting system. 3. Sport for Development and Behavioural Change (SfD&BC) which use a collaborative partnership approach to make an individual behavioural difference using a bespoke approach, as noted by one delivery agent,

Participation in sport to improve quality of life (interview with DA1 25 April 2018).

It is here that sport acts as a hook for engagement with hard-to-reach groups. Nevertheless, there is no formal structure or guidance at a strategic level to support the transition through this process.

We are recognised for our work and have helped other clubs who approached us but there isn’t a formal way to do this (Interview with DA3 18 April 2018).

Rather, organisations are tasked with delivering projects to meet the predefined targets with limited consideration for broader transition and learning along the pathway. A task-based process prioritises numbers over impact (Bloyce and Smith Citation2010, Coalter Citation2009, Adams and Harris Citation2014).

attempts to articulate how each element could overlap, with input from all relevant stakeholders to contribute or lead where appropriate to their statutory responsibility.

For participants, there are multiple entry and exit transition points within , yet with limited strategic direction the multiple funder development agendas restrict policy cohesion across the overlapping elements, the importance emphasised by one delivery agent who suggested,

there is no room for parameters, you need to be able to help even if it goes beyond your job description or remit, it’s about facilitating support if you can’t provide it directly. We need to get the person through the gate and support them. Sport is the hook, but we then need to work with others to provide the wrap around care. Unfortunately, public bodies are too rigid, it needs to be person centred rather than process driven (Interview with DA3 14 October 2019).

This comment supports the inclusion of the third sector, since the involvement of mainstream organisations can perpetuate the exclusion of some vulnerable groups and thus, sporting organisations with specialism in SfD&BC can act as a conduit for engagement (Haudenhuyse et al. Citation2012). The activities carried out at these touch points go beyond the remit of any individual funding organisation, recognising the need for alignment across the circles of Sugden’s Ripple Effect Model (2010) inclusive of individual, community and policy leaders. With little evidence of agreed purpose, the situation detailed supports the findings by Kidd and Donnelly (Citation2007) who suggested that SfD remains largely isolated from the mainstream development efforts leaving sporting groups to support individuals at a local level, who are faced with a ridged multi-agency offering without a multi-agency approach.

Influence

Sustained involvement in SfD&P activity has provided delivery organisations with much learning, which has shaped decisions at an organisational level.

it can’t be trying to create a project to fit a funding stream and we can’t attempt to run after a number of funds … . we have been able to open conversations with funders by showing what else could be done … . initially that was year-end monies … … but now they .come early and ask if there are projects we could deliver and we can really plan (interview with DA1 24 May 2018).

This statement suggests that access to networks and the subsequent relationships (Hall et al. Citation2003) enable sporting organisations to influence the funder. The rationale for the change in approach was clearly articulated by a further delivery agent who noted,

When the large grant wasn’t renewed the organisation was almost decimated because delivering the project took all their resources (interview with DA3 18 April 2018).

This comment demonstrates the dangers for delivery organisations in a task-based process noted previously by altering their strategic objectives to secure funding (Sanders Citation2016) rather than constructing a clearly defined sustainable sports sector. Reliance on funding and the uncertainty surrounding sustainability perpetuate a continual shifting of objectives to follow funders' priorities rather than the specific needs of those they wish to support (Kidd Citation2008).

presents changing push-pull continuum between the government funder and delivery agent, whereby both sides influence each other towards their own development or sporting objectives. The more frequent the interactions the greater the opportunity for influence, the power shift dictated by greatest need. The increasing role for the third sector in achieving government agendas has substantially altered this continuum over time. In so doing, these sporting organisations are gaining additional capacity as a result of learning through doing.

The depiction of the push-pull continuum () denotes sporting stakeholders are using access and skills to push government to understand the benefits of sport, gaining improved organisational network and structural capacity (Hall et al. 2013) which has, improved project level effectiveness and efficiency. Nevertheless, financial dependency limits the macro-level impact, enabling departments to pull delivery agent further towards achieving project level targets. This top-down influence of funding was noted by a further stakeholder,

There is a push to use physical activity and mental health. Traditional sports funding has been reduced. The expectation is that the majority of sports funding will require additional work on non-sport issues (Interview with DA1 24th May 2018).

The suggestion intimates that the sporting sector is being influenced by funders to move away from traditional SD with monies ringfenced to achieve against a wide diversity of funder agendas with a void of any coordinating role in leading a cohesive sporting sector.

Dependency

Increasingly, government promotes the desire for public, private and third sector to work collaboratively to achieve efficient and effective public services (Friedman Citation2015). In considering examples of such collaborations, one delivery agent highlighted the collaborative nature of the promotion of disability sport,

The ‘active living no limits’ programme which ‘brought together all the key stakeholders in the area of disability sport, in doing so each group had a role within the programme. It became a hub-based approach to meet local need’ (interview with DA3 17 May 2019).

In this instance, both delivery and policy stakeholders came together to share information and better understand each other at a micro, meso and macro level, creating a plan which addressed the issues identified by those involved. The process supported the view of a further delivery agent who noted,

there is a need to better understand each other and determine how you can help each other (Interview with DA3 30 January 2018).

Consequently, addressing the concerns raised previously in this article related to defining the problem and agreeing the outcomes (Coalter Citation2007, Sinek Citation2011, Friedman Citation2015, Darko and Mackintosh Citation2015). Reflection on the discussion of access noted previously is revealing, as once access is obtained it can be used to influence programmes and build organisational capacity. As described by one delivery agent,

We have become more strategic, the engagement with funders helped, we can help shape programmes and funders come back in when planning and ask for our input (interview with DA1 24 May 2018).

This improvement in relationship and network capacity (Hall et al. 2003) promotes the support structures within an organisation that help it to function and thus creates a competitive advantage through a process of ‘learning by doing’ (Robinson and Minikin Citation2012, Grant Citation2016).

The subsequent ability to maximise these connections was described by one policymaker,

we are able to work with those on the ground and build projects that achieve beneficial outcomes (interview with Policy maker 30 January 2018).

This point was substantiated when the three largest sporting bodies in NI (Gaelic Athletic Association, Irish Football Association and Irish Rugby Football Union) were asked to contribute to a separate government strategy (Together Building a United Community: TBUC) noting ‘the partnership (between the three sports) has enabled each organisation to gain considerable experience in the field of good relations’ (Citation2016, p. 3). These findings validate the need to further explore inter-organisational learning in SfD programmes to demonstrate the reach of public sector investments (Corvino et al. Citation2022), recognise value and leverage learning.

Value

The depiction of a greater role for the so-called ‘less dominant partners’ (sporting groups) provides evidence of what Morrow and Robinson (Citation2013) described as both unilateral or bilateral power restructuring of operations. By accessing resources from althernative sources ‘less dominant partners’ are able to reduce financial reliance on single funders. Their knoledge of local need and capacity to deliver becomes a valuable resource sought after by the dominat orgnisation. In essence, there is evidence that the less dominant organisations are not only able to leverage and develop these existing resources but attract more funding by showcasing their benefits across various government departments thus, reducing the level of dependency on singular funders, potentially establishing greater levels of autonomy (Robson Citation2008). The organisational contribution phase of OBA, therefore, demonstrates improvements in delivery at a project level; nevertheless, the lack of a common purpose for SfD&P activity means any influence is restricted to a project level or organisation priority rather than a sustained population level impact.

The subsequent lack of sectoral identity and strategic leadership isolates organisations who are left to look out for themselves, as one delivery agent noted,

Funding can pit organisations against each other … … they have to spilt funding between them rather than obtain more funding between them … .there is always a thought around protectionism (Interview with DA2 15 Feb 2018).

Further supporting the view that organisations ‘engage in co-optation and constraint activities as a way to strengthen the dependency relationships and protect their position’ (Morrow and Robinson Citation2013, p. 413). The funding structure can thus be seen to perpetuate the cycle, with reliance on funding instilling a narrow project-based approach which contributes to fragmentation, duplication, competition and limits both impact and sustainability (Lindsey Citation2016). A point supported by a further stakeholder who suggested,

Pulling public funding in sport would create a big problem, it shouldn’t be a question of reducing the money it should be a question of is the money going to the right places? (interview with DA3 18 April 2018).

This discussion substantiating the point raised previously that funding and monitoring mechanisms prioritise project level outputs at the expense of a wider strategic approach; consequently, delivery agents are faced with a dilemma of attempting to be all things to all people (Coalter Citation2007) while constantly adopting organisational aims to follow funding sources (Sanders Citation2016).

A further delivery agent expressed concern regarding the value of sport,

groups don’t realise their value and don’t have the expertise to attract more money (Interview with DA1 25 April 2018).

The lack of clarity in sectoral purpose and the absence of understanding of the value of sport restricts the bottom-up influence that can be applied through increased network and structural capacity, thus prolonging the dependency on public sector funding and further demonstrating the negative impact of the task-based approach and the lack of clarity around targeted population level impact.

Sustainability

At a delivery level, there is evidence of organisations collaborating such as the example of Disability Sport NI which adopted a more sustainable investment model to leverage what Hall et al. (2003) described as more money and better money (Wicker and Breuer Citation2014,) while at the same time improving understanding across stakeholders. The reality for those delivering programmes was noted by one stakeholder,

Organisations need to look for a self-sustainable mix of funding sources to lower dependency … … (and) reduce the control over them (interview with DA3 18 April 2018).

To achieve this level of autonomy, organisations must prove their value; nevertheless, researchers have identified the restrictive quantitative nature of SfD monitoring which prioritises numbers over impact (Adams and Harris Citation2014). A point raised by one delivery agent who suggested that,

Compliance rates and participation rates are the wrong tools to measure success and forces projects to look at numbers rather than the difference they can make (Interview DA3 14 October 2019).

In marked contrast to the sporting system and inclusive sports (), which can draw on numerous evaluation instruments to demonstrate population change and value for money, facilitating long term sectoral sustainability (Keane et al. Citation2019), SfD&P struggles to prove its value within this public sector monitoring process.

Evidence

Tackling wicked issues (Bianchi Citation2015) involved in SfD&BC is inherently inefficient, time-consuming and expensive; moreover, the impact is inherently difficult to measure. Highlighting incompatibility with the value for money focus within the public sector (Parsons Citation2002).

By establishing participation figures as a criterion for monitoring, projects may consider recruiting participants who are more likely to complete programmes (Spaaij et al. Citation2013) rather than those at greatest need. Evaluation must, therefore, appreciate the complexity, ambiguity, variability and time-dependency in context (Bush and Houston Citation2011). One stakeholder noted,

There are methods of measuring and evidencing difference using theory of change models however … … the capacity is not there to … … evidence the difference (interview with DA3 18 April 2018).

The discussion supports the concerns raised regarding the appropriateness of the planning, design, monitoring and post-activity evaluation within SfD (Kidd Citation2008, Darnell et al. Citation2018b) and indeed the public sector (Pollitt Citation2003, Adams and Harris Citation2014), whereby monitoring processes can reinforce the problems they were attempting to address (Bush and Houston Citation2011).

Recommendations

The ability to agree common purpose and align community need with policy direction requires enduring action, at all levels, as part of a process which supports interaction in a joint top-down and bottom-up manner (Höglund and Sundberg Citation2008).

More broadly, if sporting organisations are to move beyond the project focus and maximise their potential, there needs to be a sectoral approach where organisations come together under one framework nationally and internationally. This should include a clearly defined purpose articulated within an overarching strategy which incorporates redistributionist discourse (Spaaij et al. Citation2013) to address the root cause conditions that led to inequalities originally. This approach would enable an agreed evaluation model to be used to demonstrate the combined value of sport and physical activity initiatives at a regional level (culturally relevant issues) and an international level (sectoral issues) to inform future planning.

Transition

It is the intersection between inclusive sport and SfD&BC where greatest uncertainty exists due to ambiguity, limited central leadership and common purpose. A strong outcome-focused and flexible model is required to promote effective transitions, as suggested by one stakeholder,

A collaborative cross departmental and sector approach is needed. But no organisation is above another … . there is a desire in public sector to label things into a box and to make it rigid so it is measurable and manageable, but with sport for social change this will not work (interview with DA3 18 April 2018).

Clear mechanisms are needed to represent this intersection (top-down and bottom-up) to facilitate consultation and engagement between (and within) the sport system (performance, talent identification and participation) and the development system.

Traditionally, SfD has been seen in isolation from other development agendas (Kidd and Donnelly Citation2007). This article presents a picture of increased public-sector funding together with a corresponding increase in government influence to engage underrepresented groups through Coulter’s (Citation2007) sport plus model. At the other side of the intersection individual government departments are increasingly using SfD&P to achieve a plethora of development objectives targeting behavioural change as part of plus sport model (Coulter Citation2007) to transition into supporting (non-active) development programmes. The concern at present is the lack of transition support across and beyond the (inclusive sport and SfD&BC) intersection. This point was previously made by a stakeholder who noted the need to get the participant ‘through the gate’ and to work with others to provide wrap around care.

Improved policy cohesion has the opportunity to facilitate transition (individual and process) support through top-down coordination of the sector by expanding existing remits to align relevant government strategies.

Support is required to give a voice to the sector, inclusive of existing representatives from the sport, physical activity, play and recreation sectors. A point endorsed by one policymaker who noted that,

DPfG relies on the volunteer sector, there needs to be a group to allow all stakeholders to put their views on the table, everyone should have a voice but we need someone to take the bull by the horns. This should be led by existing structures otherwise there is additional cost which is taken out of the sector (interview policy maker 2 August 2019)

Future strategies will require governance and regional coordination through some form of high-level strategy group, which recognises the three overlapping areas, providing a mechanism for local community delivery. Support for delivery agents should include sectoral signposting to funding, disseminating need and informing the articulation of purpose. Inclusive of existing structures, which was previously supported by Research Scotland (Citation2017, p. 4) which found that ‘networking opportunities should link with existing related networks of sport, physical activity and outcomes-focused organisations, to ensure that they complement (rather than duplicate) other activity’. In NI, this requires the inclusion of grassroots voluntary and community groups to create change (Bush and Houston Citation2011).

At a delivery level there is a need for a collation of sport with no one agency leading, no one agency has all the answers or perspectives and a group like this would certainly aid decision making and clarity. It needs to be grassroots up context (Interview with DA3 18 April 2018).

Improving collaborations and partnerships provides a mechanism to leverage greater benefits from sectoral investment. As one stakeholder suggested,

those who receive funding should give back (Interview with DA1 24 May 2018).

In these circumstances, the competitive advantage gained from managing funded programmes should be valued and learning disseminated as part of all large funding programmes. Consequently, larger sporting organisations (successful in attracting public funding) could act as mentors to the smaller (unfunded groups) as part of an in-kind contribution to the sector. This would in turn improve the sector as a whole and leverage greater benefit from the original funding. Indeed, the larger partner may also generate intangible benefits (Morrow and Robinson Citation2013).

Sustainability of investment in the sector was raised by one stakeholder who noted,

it’s not about a funding model, it’s about investing in partners and each model should be different depending on the environment. Ultimately, it’s about making a difference beyond the investment (Interview with DA3 17 May 2019).

The comment points to the need for connections between and across organisations involved in strategic and operational delivery of SfD&P activity as part of a coordinated approach with centralised leadership towards agreed long term strategic outcomes, supporting previous SfD research (Corvino et al. Citation2022). To succeed a sport related government indicator in required whereby each stakeholder has a responsibility, varying between leading, coordinating (networks), contributing (expertise) or investing (financial), dependent on their relevance and local need thereby, improving both efficiency and effectiveness.

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated how alternative approaches from related disciplines offer benefits to SfD research (Schulenkorf et al. Citation2016). By contextually combining management tools, this study has generated findings which provide evidence to support policymakers with the process of creating and monitoring strategy and, in particular, considerations in adopting outcomes-based approach to SfD&P during modernisation. This study offers insights into how best to balance project accountability alongside side increased effectiveness at a sectoral level. While those delivering SfD&P will understand the need to evidence value and maximise resources through a formalised process to build a sustainable sector.

This article set out to answer three interlinking questions, the first explored, the alignment between top-down and bottom-up practice in the transition of outcomes across the micro, meso and macro levels. In doing so, this study has identified a three-point pathway within the sporting sector where traditional SD (the sporting system) has expanded to tackle inequalities (inclusive sports) as part of a broader policy agenda to engage with the hardest to reach; with a third element using sport as a medium to tackle societal development needs (sport for development and behavioural change). The absence of clear structures to support transition (individual and organisational) through this process creates a task-oriented sector restricting its overall outcomes potential. This ambiguity further complicated by sports broad definition in policy (European Commission Citation2007) which defines sport as one all-encompassing discipline rather than multiple interlinking elements. Amplified by different departments viewing the same issue from different perspectives (Bogdanor Citation2005) perpetuated by confusion around language and definitions. The task-based system identified in this study stems from the focus of public sector on the technical verification (Adams and Harris Citation2014) of policy rather than tackling value conflict and reaching common agreement on policy goals (Stoker Citation2004). Thus, restricting recognition of value and inter-organisational learning to the micro and meso level and thus limiting the ability to illustrate the reach of public sector investments (Corvino et al. Citation2022).

The second question investigated to what extent there was evidence of cohesiveness across the structures which oversee and deliver SfD&P activity. The thematic analysis demonstrated how purpose, collaboration and capacity, and sustainability are key sectoral considerations. The increasing government investment in sport appears primarily focused on inclusive sports, breaking down barriers and engaging with target groups through generic projects. This is at the expense of the more resource intensive individual approaches required within SfD&BC projects, which attempt to tackle root cause problems (Spaaij et al. Citation2013).

There is, therefore, a need to agree common language otherwise, disparities at the intersection between policy and practice (Spaaij et al. Citation2014) increase the likelihood of both duplication and manipulation (Birrell and Gormley-Heenan 2015) leading to misunderstanding and misapplication of the measurement indicators (Chen Citation2018). Therefore, the promotion of understanding of need across the sector and clarification of roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders requires the formal implementation of the needs analysis phase of OBA at a sectoral thematic level (Friedman Citation2015).

Question three established the level of capacity and dependency at a policy and delivery level.

By examining the application of the three management models to public sector SfD&P activity, concerns related to clarity of purpose and sectoral collaboration have been identified and solutions presented. The study has illustrated a change in the power structure as delivery organisations influence project level activity achieved through improved organisational capacity (organisational network and structural capacity) a benefit of learning by doing (Hall et al. Citation2003, Robinson and Minikin Citation2012). Similarly, the disability sport example demonstrates how policymakers can address concerns regarding validity and reliability of outcome measures (Adams and Harris Citation2014) by defining the problem and proposed outcomes (Coalter Citation2007, Friedman Citation2015, Darko and MacKintosh Citation2015). Nevertheless, autonomy is ultimately constrained due to an imbalance in financial resources (Pfeffer and Salancik Citation1978) perpetuating the focus on organisational performance as part of the task-based approach demonstrated across this study. This sectoral financial dependency limits the macro impact with the absence of a population-wide evidence base restricting sufficient bottom-up pressure to change the status quo from funding to investment model. The situation further highlights the need for collaborative practice and policy cohesion in planning, delivery, and research to promote sectoral sustainability.

For those involved in SfD&P to take control of their own destiny, agreement must be reached on an appropriate evidence model to establish a baseline from which to measure value, one which recognises the value of existing data while identifying gaps where immediate research is required.

As the public sector continues to recognise the role of sport in achieving government outcomes, the development of outcomes-based strategies offers a substantial opportunity for renewed policy cohesion with SfD&P well placed if activated as part of the cross-governmental approach.

The findings outlined within this article provide further support to the conclusion drawn by Adams and Harris (Citation2014, p. 141) who suggest ‘neoliberalism, as an ideology; new public management (NPM) as a mode of governance; and modernisation as a policy package, provide the architecture that enables and controls the contexts and frameworks within which SfD&P operates’.

The implementation of outcomes measurement is at the development stage for many organisations (Seivwright et al. Citation2016). As an emerging field SfD&P continues to find its place within a public sector, where the absence of a common language has caused ambiguity. This article contributes to future research direction by advancing knowledge for future academic work to further explore the interconnectedness across each step in the sequence from origin to outcome in SfD&P, balancing contextual uniqueness and global commonality.

This study is limited by the geographical focus and contextual extent of the examples used.

Nonetheless, this study demonstrated how combining existing models can be used to explore the SfD landscape (Jeanes and Lindsey Citation2014). By offering support to the view that accountability is requred to sustain innovation (Lindsey and Bacon Citation2016, McSweeney et al. Citation2021), allowing agreed indicators to be measured in a consistent manner to inform new policy development (Gault Citation2018).

The articulation of purpose should be embedded within an agreed and relevant (Hák et al. Citation2016) sport-related government indicator, one which endorses and mainstreams SfD&P across all portfolios within the public sector. Such a framework offers the potential to empower stakeholders and builds trust – which this article previously noted as lacking – by developing understanding (Lindsey and Darby Citation2019) through the promotion of synergies between different policies (Knoll Citation2014).

By fully applying the needs analysis phase of OBA to inform an action plan at the outset of any new sport-related strategy, accountability would be shared across all relevant stakeholders with responsibility for cross-departmental outcomes coordinated through existing structures. The measurement focus moving from ‘what we did’ to ‘what difference we made’ generating improved effectiveness and efficiency across the three interlinking elements of sport by promoting cohesion and reducing duplication. The alternative for SfD&P is a continued existence on the periphery, reliant on the prioritises of broader agendas rather than the control that comes with speaking as one collective voice, offering expertise and insight as a central pillar for success, with stakeholders accountable under a common government indicator.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adams, A. and Harris, K., 2014. Making sense of the lack of evidence discourse, power and knowledge in the field of sport for development. International journal of public sector management, 27 (2), 140–151. doi:10.1108/IJPSM-06-2013-0082.

- Bainer, A. 2013. Sport, the Northern Ireland peace process and the politics of identity. Journal of Agression. Conflict and Peace Research, 5 (4), 220–229.

- Bianchi, C., 2015. Enhancing joined‐up government and outcome‐based performance management through system dynamics modelling to deal with wicked problems: the case of societal ageing. Systems research and behavioral science, 32 (4), 502–505. doi:10.1002/sres.2341.

- Birrell, D. 2014. Qualitative research and policy making in Northern Ireland: barriers arising from the lack of conensus, capacity and conceptualiation. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 27 (1), 20–30.

- Birrell, D. and Gormley - Heenan, C. 2015. Multi-level Governance and Northern Ireland. Basingstoke. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Bloyce, D. and Smith, A., 2010. Sport policy and development. New York: Routledge.

- Bogdanor, V., ed., 2005. Joined-up government (Vol. 5). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bush, K. and Houston, K. 2011. The story of peace: learning from EU PEACE funding in Northern Ireland and the border region. International Conflict Research Institute Research Paper.

- Byrne, J.G.H., et al., 2015. Public attitudes to peace walls. 2015 survey results. Ulster University.

- Chen, S., 2018. Sport policy evaluation: what do we know and how might we move forward? International journal of sport policy and politics, 10 (4), 741–759. doi:10.1080/19406940.2018.1488759.

- Christensen, T. and Lægreid, P., 2007. The whole‐of‐government approach to public sector reform. Public administration review, 67 (6), 1059–1066. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00797.x.

- Coalter, F., 2007. A wider social role for sport: who’s keeping the score?. London: Routledge.

- Coalter, F., 2009. Sport-in-development: Accountability or Development? In Sport and International Development. eds., R. Levermore, A.P.M. Beacom, and H. 55–75.

- Corvino, C., Gazzaroli, D., and D’angelo, C., 2022. Dialogic evaluation and inter-organizational learning: insights from two multi-stakeholder initiatives in sport for development and peace, 29 (2), 157–171.

- Coulter, F., 2007. A wider social role for sport. Who’s keeping score?. London: Routledge.

- Darko, N. and Mackintosh, C., 2015. Challenges and constraints in developing and implementing sports policy and provision in Antigua and Barbuda: which way now for a small island state? International journal of sport policy and politics, 7 (3), 365–390. doi:10.1080/19406940.2014.925955.

- Darnell, S.C., et al., 2018a. The state of play: critical sociological insights into recent ‘sport for development and peace’ research. International review for the sociology of sport, 53 (2), 133–151. doi:10.1177/1012690216646762.

- Darnell, S.C., et al., 2018b. Re-assembling sport for development and peace through actor network theory: insights from Kingston, Jamaica. Sociology of sport journal, 35 (2), 89–97. doi:10.1123/ssj.2016-0159.

- Davies, J.S., 2009. The limits of joined‐up government: towards a political analysis. Public administration, 87 (1), 80–96. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.01740.x.

- Durose, C., Justice, J., and Skelcher, C., 2015. Governing at arm’s length: eroding or enhancing democracy? Policy and politics, 43 (1), 137–153. doi:10.1332/030557314X14029325020059.

- Elcock, H., Fenwick, J., and McMillan, J., 2010. The reorganization addiction in local government: unitary councils for England. Public money & management, 30 (6), 331–338. doi:10.1080/09540962.2010.525000.

- European Commission. 2007. White paper on Sport. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52007DC0391&from=en [Accessed 13 11 2015].

- Ferguson, K., Hassan, D., and Kitchin, P., 2018. Sport and underachievement among protestant youth in Northern Ireland: a boxing club case study. International journal of sport policy and politics, 10 (3), 579–596. doi:10.1080/19406940.2018.1450774.

- Fowler, A., ed., 2013. Striking a balance: a guide to enhancing the effectiveness of non-governmental organisations in international development. London: Routledge.

- Friedman, M., 2015. Trying hard is not good enough: how to produce measurable improvements for customers and communities. Santa Fe: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. edition 10.

- GAA, IFA, IRFU. 2016. Joint inquiry response – together: building a united community. Available at: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/ofmdfm/inquiries/building-a-united-community/written-submissions/gaa-ifa-and-irfu-ulster-branch.pdf [Accessed 2 May 2017].

- Gault, F., 2018. Defining and measuring innovation in all sectors of the economy. Research policy, 47 (3), 617–622. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2018.01.007.

- Grant, R.M., 2016. Contemporary strategy analysis: text and cases edition. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Gray, A. and Birrell, D., 2018. Outcomes-based approaches and the devolved administrations. In: Needham Catherine, Heins Elke, and Rees James, eds. Social policy review 30: analysis and debate in social policy. Bristol: Policy Press, 67–86.

- Hák, T., Janoušková, S., and Moldan, B., 2016. Sustainable development goals: a need for relevant indicators. Ecological indicators, 60, 565–573. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.08.003

- Hall, M., et al., 2003. The capacity to serve. In: H. Michael, A. Andrukow, C. Barr, and K. Brock, eds. A qualitative study of the challenges facing canada’s nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy, 1–50.

- Hassan, D. and Ferguson, K., 2019. Still as divided as ever? Northern Ireland, football and identity 20 years after the good Friday agreement. Soccer & Society, 20 (7–8), 1071–1083. doi:10.1080/14660970.2019.1680504.

- Hassan, D. and Telford, R. 2014. Sport and Community Integration in Northern Ireland. Sport and Society, 17 (1), 89–101.

- Haudenhuyse, R.P., Theeboom, M., and Coalter, F., 2012. The potential of sports-based social interventions for vulnerable youth: implications for sport coaches and youth workers. Journal of youth studies, 15 (4), 437–454. doi:10.1080/13676261.2012.663895.

- Heald, D. and Steel, D., 2018. The governance of public bodies in times of austerity. The British accounting review, 50 (2), 149–160. doi:10.1016/j.bar.2017.11.001.

- Höglund, K. and Sundberg, R., 2008. Reconciliation through sports? The case of South Africa. Third world quarterly, 29 (4), 805–818. doi:10.1080/01436590802052920.

- Houlihan, B. and Lindsey, I., 2013. Sport policy in Britain. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jeanes, R. and Lindsey, I., 2014. Where’s the evidence? Reflecting on monitoring and evaluation within sport for development. In sport, social development and peace. Emerald Group Publishing limited, Vol. 8, 197–217.

- Joyce, P., 2015. Strategic management in the public sector. London: Routledge.

- Keane, L., et al., 2019. Methods for quantifying the social and economic value of sport and active recreation: a critical review. Sport in Society, 22 (12), 2203–2223. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1567497.

- Kidd, B., 2008. A new social movement: sport for development and peace. Sport in society, 11, 370–380. doi:10.1080/17430430802019268

- Kidd, B. and Donnelly, P., 2007. Literature reviews on sport for development and peace. Toronto: commissioned by SFD IWG secretariat, 30, 158–194.

- Knoll, A. 2014. Bringing policy coherence for development into the post-2015 agenda–challenges and prospects. Maastricht: ECDPM (Discussion Paper No. 163).

- Knox, C. 2015. Sharing power and fragmenting public services: Complex government in Northern Ireland. Public Money & Management, 35 (1), 23–30.

- Lapsley, I. and Miller, P., 2019 Transforming the public sector: 1998-2018. In: Accounting, auditing & accountability journal, 32 (8), 2211–2252.

- Lindsey, I., 2016. Governance in sport-for-development: problems and possibilities of (not) learning from international development. International review for the sociology of sport, 52 (7), 801–818. doi:10.1177/1012690215623460.

- Lindsey, I. and Bacon, D., 2016. In pursuit of evidence-based policy and practice: a realist synthesis-inspired examination of youth sport and physical activity initiatives in England (2002–2010). International journal of sport policy and politics, 8 (1), 67–90. doi:10.1080/19406940.2015.1063528.

- Lindsey, I. and Darby, P. 2018. Sport and sustainable development goals: Where is the policy coherence?. International Review for sociology of sport, 54 (7), 793–812.

- Lindsey, I. and Darby, P., 2019. Sport and the sustainable development goals: where is the policy coherence? International review for the sociology of sport, 54 (7), 793–812. doi:10.1177/1012690217752651.

- Lobao, L., et al., 2018. The shrinking state? Understanding the assault on the public sector. Cambridge journal of regions, economy and society, 11 (3), 389–408. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy026.

- Lombardo, G., et al., 2019. Assessment of the economic and social impact using SROI: an application to sport companies. Sustainability, 11 (13). doi:10.3390/su11133612.

- Matters, S., 2009. The Northern Ireland strategy for sport and physical recreation 2009 to 2019. Northern Ireland: Department for the Communities.

- McSweeney, M., et al., 2021. Becoming an occupation? A research agenda into the professionalization of the sport for development and peace sector. Journal of sport management, 1 (aop), 1–13.

- Mitchell, P.S., Hargie, I., and , O. 2016. Sport for Peace in Northern Ireland? Civil Society, change and contraint after he 1998 Good Friday Agreement. The British Journal of Politics and Intrnational relations, 23 (1), 34–49.

- Morgan, H., Bush, A., and McGee, D., 2021. The contribution of sport to the sustainable development goals: insights from commonwealth games associations. Journal of sport for development, 9 (2), 14.

- Morrow, S. and Robinson, L., 2013. The FTSE-British Olympic association initiative: a resource dependence perspective. Sport management review, 16 (4), 413–423. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2013.01.002.

- Neuman, W.L., 2013. Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 7th ed. Essex: Pearson Education.

- Norris, N., 1997. Error, bias and validity in qualitative research. Educational action research, 5 (1), 172–176. doi:10.1080/09650799700200020.

- Parsons, W., 2002. From muddling through to muddling up-evidence based policy making and the modernisation of British Government. Public policy and administration, 17 (3), 43–60. doi:10.1177/095207670201700304.

- Pfeffer, J. and Salancik, G., 1978. The external control of organizations. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Pollitt, C., 2003. Joined-up government: a survey. Political studies review, 1 (1), 34–49. doi:10.1111/1478-9299.00004.

- Research Scotland. 2017. Sport for change research. Available: https://sportscotland.org.uk/media/2275/sport-for-change_final-report.pdf [Accessed March 2018].

- Rhodes, R.A.W., et al., 2003. Decentralizing the civil service. Buckingham: McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Robinson, L. and Minikin, B., 2012. Understanding the competitive advantage of national Olympic committees. Managing leisure, 17 (2–3), 139–154. doi:10.1080/13606719.2012.674391.

- Robson, S., 2008. Partnerships in sport. In: K. Hylton and P. Bramham, eds. Sports development: policy, process and practice (2nd edition). London: Routledge, 99–125.

- Ruane, J. and Todd, J., 2003. A changed Irish nationalism? The significance of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. In: Joseph Ruane, Jennifer Todd, and Anne Mandeville, eds. Europe’s old states in the new world order. Dublin: UCD Press, 121–145.

- Sanders, B., 2016. An own goal in sport for development: time to change the playing field. Journal of sport for development, 4 (6), 1–5.

- Schulenkorf, N., Sherry, E., and Rowe, K. 2016. Sport for development: an integrated literature review. Journal of sport management, 30 (1), 22–39.

- Seivwright, A., et al., 2016. The future of outcomes measurement in the community sector. Bankwest foundation social impact series, 6, 3.

- Sinek, S., 2011. Start with why. London: Penguin Group.

- Spaaij, R., Magee, J., and Jeanes, R., 2013. Urban youth, worklessness and sport: a comparison of sports-based employability programmes in Rotterdam and stoke on trent. Urban Studies, 50 (8), 1608–1624. doi:10.1177/0042098012465132.

- Spaaij, R., Magee, J., and Jeanes, R., 2014. Sport and social exclusion in global society. London: Routledge.

- Sport, N.I. 2017. Exchequer annual report and accounts. Available at: http://www.sportni.net/exchequer-accounts/?pg=2 [Accessed April 2021].

- Stoker, G., 2004. New localism, progressive politics and democracy. The political quarterly, 75, 117–129. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2004.627_1.x

- Sugden, J. 1991. Belfast United: Encouraging cross community relations through sport in Northern Ireland. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 15 (1), 59–80.

- Sugden, J., 2005. Sport and community relations in Northern Ireland and Israel. In: Alan Bairner, ed. Sport and the Irish: Histories, dentities, Issues. Dublin: Dublin Press, 238–251.

- Sugden, J., 2006. Teaching and playing sport for conflict resolution and co-existence in Israel. International review for the sociology of sport, 41 (2), 221–240. doi:10.1177/1012690206075422.

- Sugden, J. 2018. Sport and peace-building. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2018/06/5.pdf [Accessed May 2021].

- Wicker, P. and Breuer, C., 2014. Exploring the organizational capacity and organizational problems of disability sport clubs in Germany using matched pairs analysis. Sport management review, 17 (1), 23–34. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2013.03.005.

- Wilfor, R. and Wilson, R., 2006. The Belfast Agreement and Democratic Governance. New Island, Dublin.